Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Disease-Opinion dynamics models

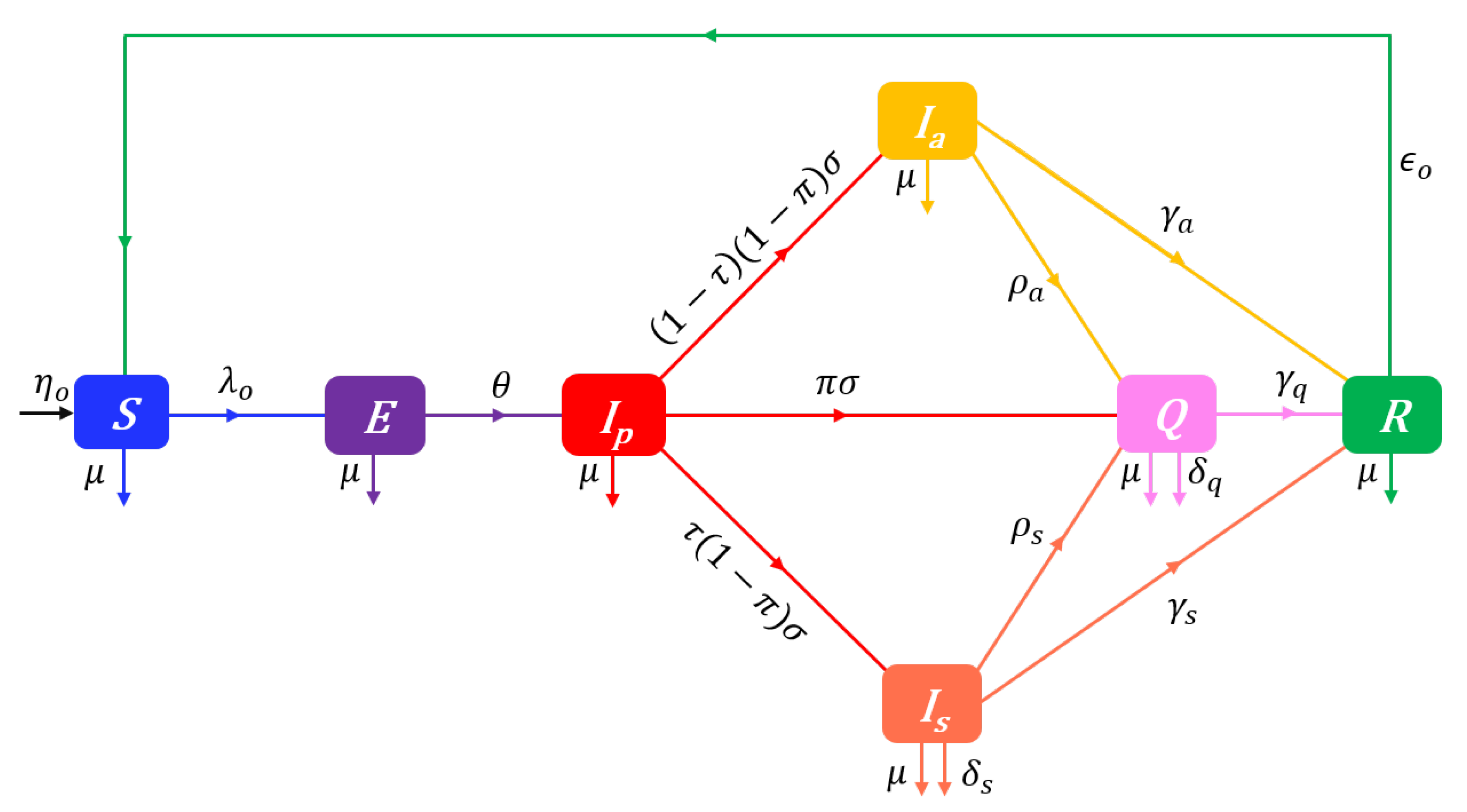

2.1. Disease dynamics

2.2. The Prophylactic attitude spectrum

2.3. The source and rate of opinion dynamics

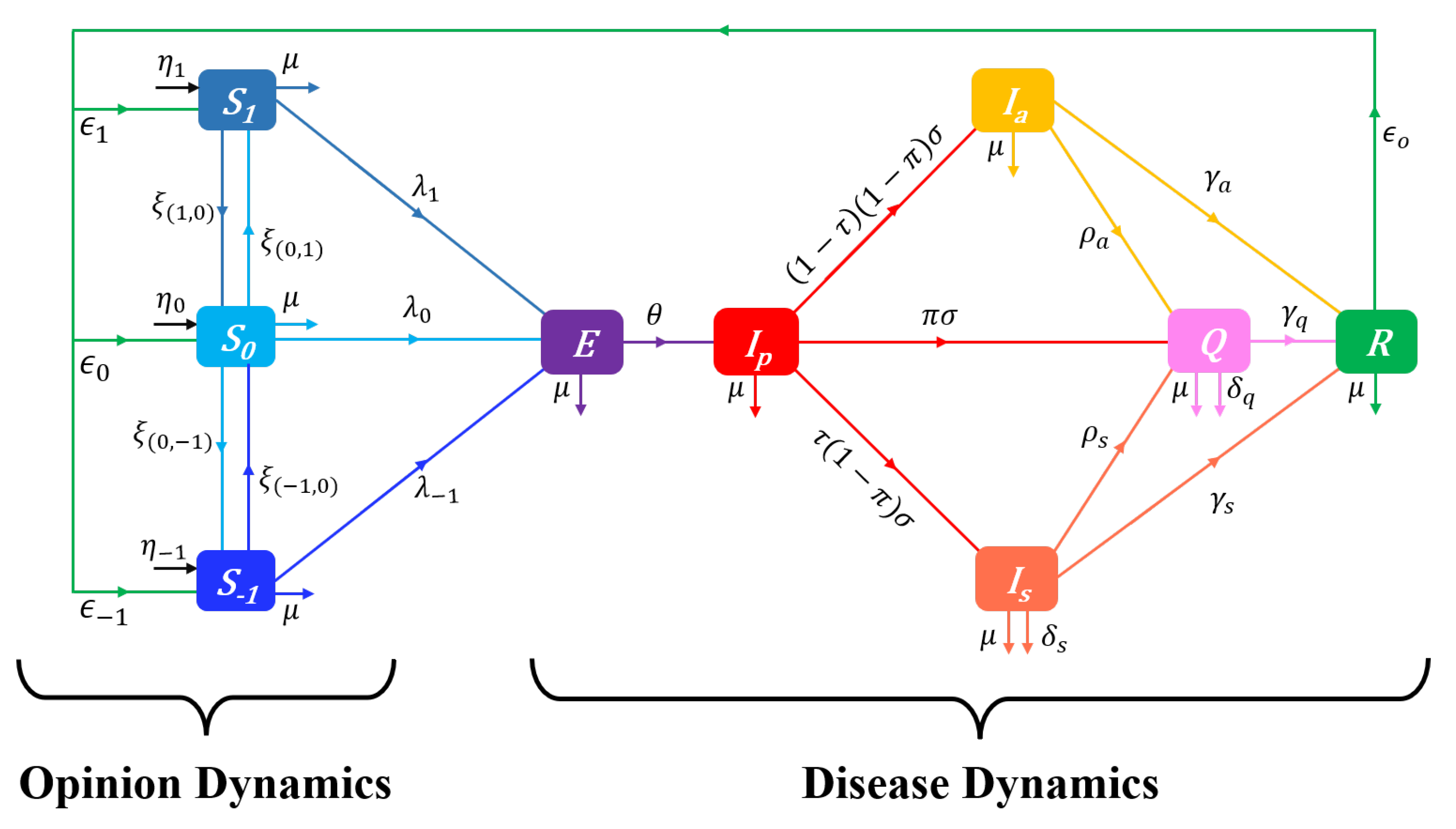

2.4. The SEIQR-Opinion dynamics model

2.5. The prophylactic attitude field

2.6. Changes in prophylactic attitudes in the presence of vaccination

2.7. Changes in attitudes towards vaccination

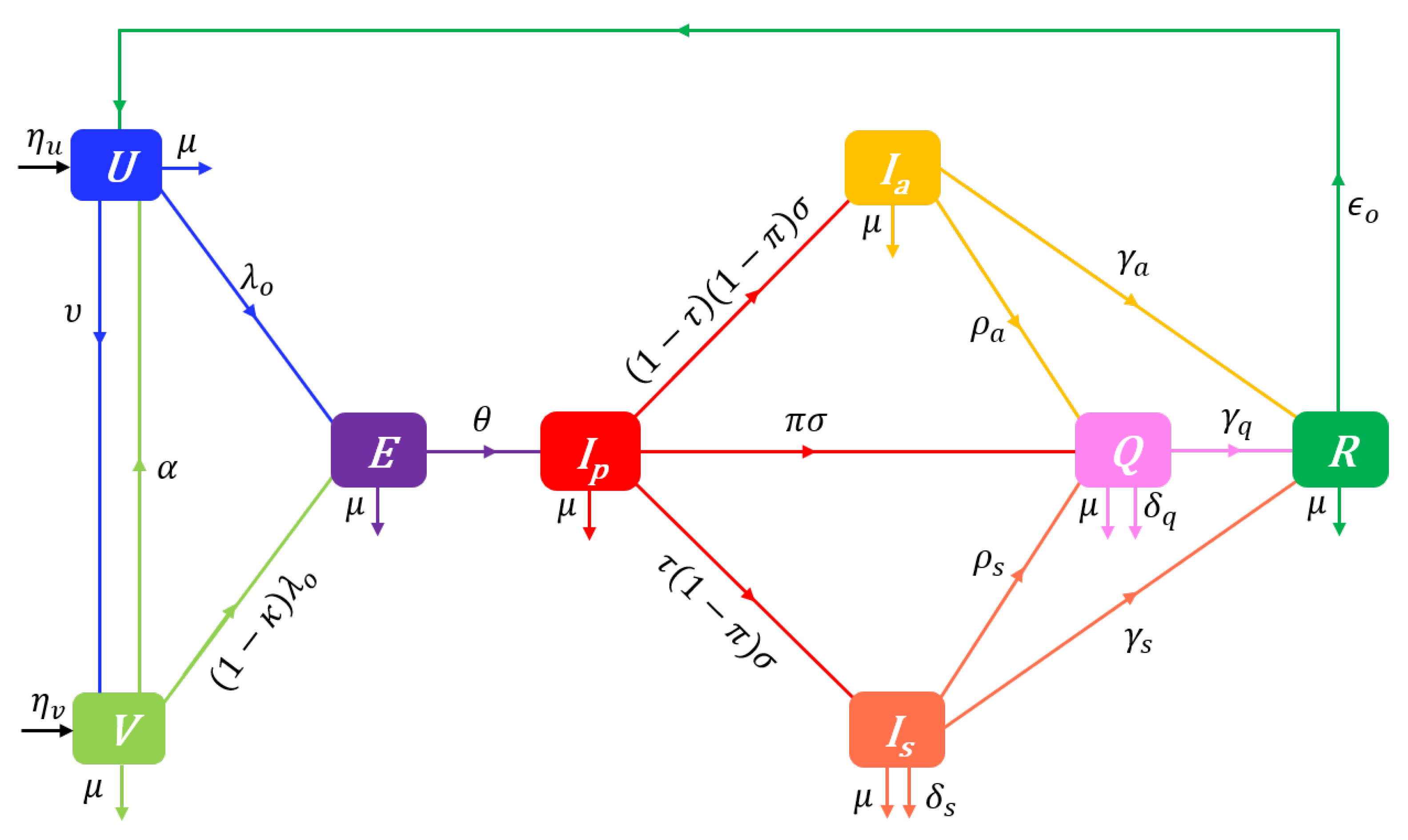

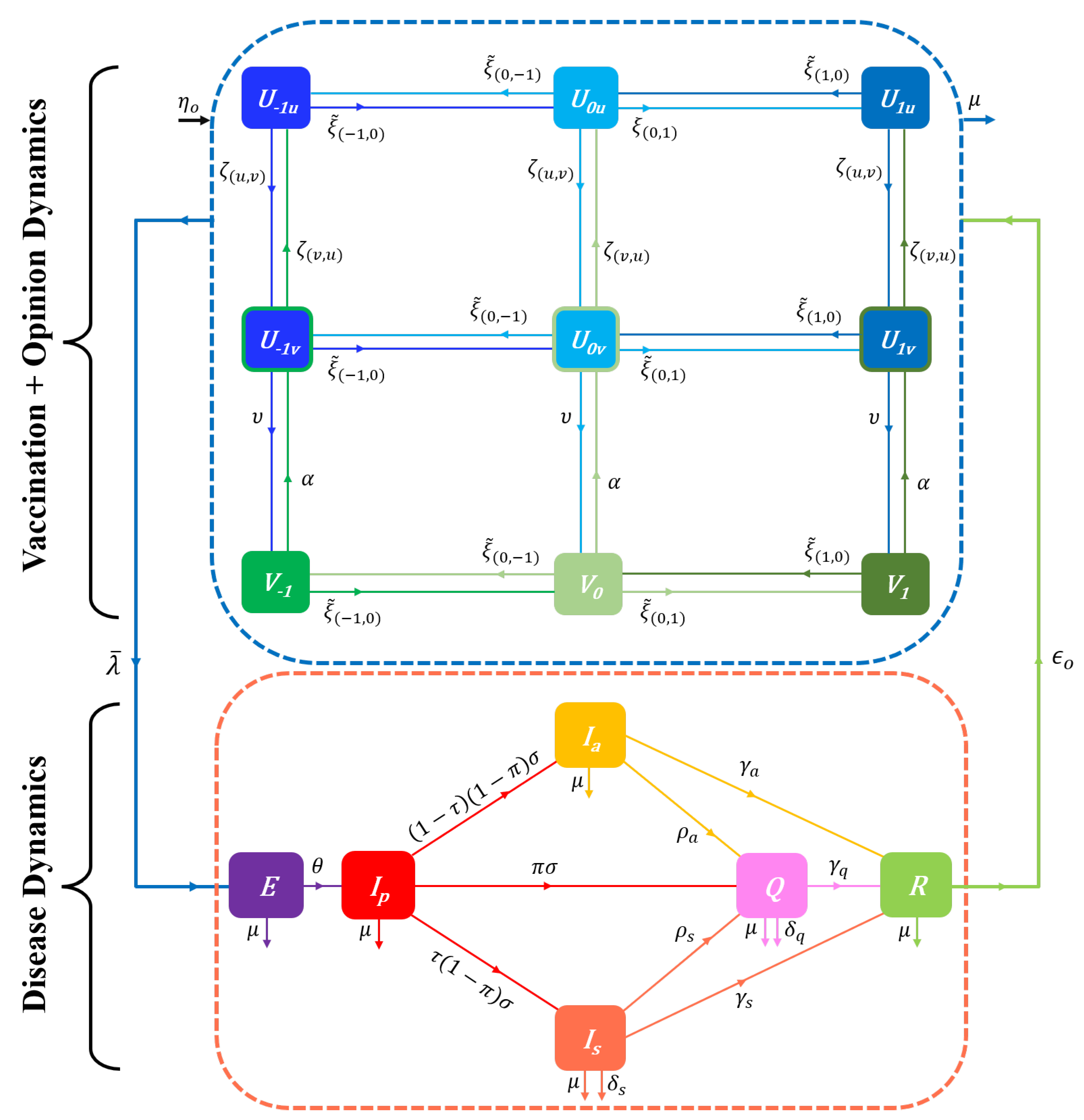

2.8. The UVEIQR-Opinion dynamics model

3. Analytical results

3.1. Vaccination–free disease–free equilibrium and reproduction numbers

3.2. Disease–free equilibrium and reproduction numbers in a vaccination context

3.3. Stability of disease–free equilibriums and persistence of the disease

4. Numerical results

4.1. Impacts of the initial distribution of behaviours

4.1.1. Vaccination-free dynamics

4.1.2. Vaccination-dependent dynamics

4.2. Impacts of the nature of behavioural responses

4.3. Impacts of detection rates and distorted perceived disease prevalence

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. The impact of opinions on disease dynamics

5.2. The behavioural response to vaccination

5.3. The impact of distorted perceived disease prevalence

5.4. Limits and perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The disease dynamics models

Appendix A.1. The extended SEIQR model

Appendix A.2. The UVEIQR model

Appendix A.3. Mathematical properties

- Non-negativity and boundedness

- Disease-Free Equilibrium and Reproduction Number

Appendix B. Overview of fixed-order saturating influence functions

Appendix B.1. Vaccination–free influence functions

Appendix B.2. Influence functions accounting for vaccination

Appendix C. Perceived disease prevalence

Appendix C.1. Inferring Disease Prevalence from Medical Data

Appendix C.2. Common measures of perceived disease prevalence

Appendix D. Proofs of lemmas and propositions

Appendix D.1. Proofs of lemmas and propositions related to disease dynamics Only

Appendix D.2. Proofs of lemmas and propositions related to Disease-Opinion dynamics

Appendix E. Details on the disease–free state of the UVEIQR-Opinion model

References

- Morens, D.M.; Fauci, A.S. Emerging pandemic diseases: how we got to COVID-19. Cell 2020, 182, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neiderud, C.J. How urbanization affects the epidemiology of emerging infectious diseases. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology 2015, 5, 27060. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.F.; Acevedo-Whitehouse, K.; Pedersen, A.B. The role of infectious diseases in biological conservation. Animal Conservation 2009, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, M.E.; Gowtage-Sequeria, S. Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2005, 11, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Zhang, T.; others. Mobile Apps Leveraged in the COVID-19 Pandemic in East and South-East Asia: Review and Content Analysis. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2021, 9, e32093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; others. Leveraging Transfer Learning to Analyze Opinions, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intentions Toward COVID-19 Vaccines: Social Media Content and Temporal Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23, e30251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.Y.S.; Budenz, A. Considering emotion in COVID-19 vaccine communication: addressing vaccine hesitancy and fostering vaccine confidence. Health Communication 2020, 35, 1718–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mheidly, N.; Fares, J. Leveraging media and health communication strategies to overcome the COVID-19 infodemic. Journal of Public Health Policy 2020, 41, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto Curiel, R.; González Ramírez, H. Vaccination strategies against COVID-19 and the diffusion of anti-vaccination views. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, M.A.; Oestereich, A.L.; Crokidakis, N. Sudden transitions in coupled opinion and epidemic dynamics with vaccination. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2018, 2018, 053407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, M.A.; Crokidakis, N. Dynamics of epidemic spreading with vaccination: impact of social pressure and engagement. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2017, 467, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaka, R.R.; Hammershaimb, E.A.; Neuzil, K.M. Are Some COVID-19 Vaccines Better Than Others? Interpreting and Comparing Estimates of Efficacy in Vaccine Trials. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 74, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmel, A.; others. COVID vaccines and safety: what the research says. Nature 2021, 590, 538–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H.; others. COVID vaccines and blood clots: five key questions. Nature 2021, 592, 495–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnevie, E.; Gallegos-Jeffrey, A.; Goldbarg, J.; Byrd, B.; Smyser, J. Quantifying the rise of vaccine opposition on Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Communication in Healthcare 2021, 14, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotfas, L.A.; Delcea, C.; Roxin, I.; Ioanăş, C.; Gherai, D.S.; Tajariol, F. The longest month: Analyzing covid-19 vaccination opinions dynamics from tweets in the month following the first vaccine announcement. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 33203–33223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muric, G.; Wu, Y.; Ferrara, E.; others. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy on Social Media: Building a Public Twitter Data Set of Antivaccine Content, Vaccine Misinformation, and Conspiracies. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 2021, 7, e30642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eibensteiner, F.; Ritschl, V.; Nawaz, F.A.; Fazel, S.S.; Tsagkaris, C.; Kulnik, S.T.; Crutzen, R.; Klager, E.; Völkl-Kernstock, S.; Schaden, E.; others. People’s willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 despite their safety concerns: Twitter poll analysis. Journal of medical Internet research 2021, 23, e28973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. The online anti-vaccine movement in the age of COVID-19. The Lancet Digital Health 2020, 2, e504–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, A.M.; Broniatowski, D.A.; Dredze, M.; Sangraula, A.; Smith, M.C.; Quinn, S.C. Not just conspiracy theories: Vaccine opponents and proponents add to the COVID-19 ‘infodemic’on Twitter. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Zuzek, L.G.; La Rocca, C.E.; Iglesias, J.R.; Braunstein, L.A. Epidemic spreading in multiplex networks influenced by opinion exchanges on vaccination. PloS One 2017, 12, e0186492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyson, R.C.; Hamilton, S.D.; Lo, A.S.; Baumgaertner, B.O.; Krone, S.M. The timing and nature of behavioural responses affect the course of an epidemic. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 2020, 82, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, R.C.; Marshall, N.D.; Baumgaertner, B.O. Transient prophylaxis and multiple epidemic waves. AIMS Mathematics 2022, 7, 5616–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, B.; Liu, J.; Sundaram, S.; Paré, P.E. On a Networked SIS Epidemic Model with Cooperative and Antagonistic Opinion Dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Control of Network Systems 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucekkine, R.; Carvajal, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Goenka, A. The economics of epidemics and contagious diseases: An introduction. Journal of Mathematical Economics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, D. The blossoming of economic epidemiology. Annual Review of Economics 2021, 13, 539–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, R.F.; Jones, J.H.; Bonds, M.H.; Ram, Y.; Feldman, M.W. Adaptive social contact rates induce complex dynamics during epidemics. PLoS computational biology 2021, 17, e1008639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardin, L.G.; Miller, C.R.; Ridenhour, B.J.; Krone, S.M.; Joyce, P.; Baumgaertner, B.O. Planning horizon affects prophylactic decision-making and epidemic dynamics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersovitz, M. Mathematical epidemiology and welfare economics. In Modeling the interplay between human behavior and the spread of infectious diseases; Springer, 2013; pp. 185–202.

- Valle, S.Y.D.; Mniszewski, S.M.; Hyman, J.M. Modeling the impact of behavior changes on the spread of pandemic influenza. In Modeling the interplay between human behavior and the spread of infectious diseases; Springer, 2013; pp. 59–77.

- Perra, N.; Balcan, D.; Gonçalves, B.; Vespignani, A. Towards a characterization of behavior-disease models. PloS One 2011, 6, e23084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenichel, E.P.; Castillo-Chavez, C.; Ceddia, M.G.; Chowell, G.; Parra, P.A.G.; Hickling, G.J.; Holloway, G.; Horan, R.; Morin, B.; Perrings, C.; others. Adaptive human behavior in epidemiological models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 6306–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.W.; Finley, P.D.; Linebarger, J.M.; Outkin, A.V.; Verzi, S.J.; Brodsky, N.S.; Cannon, D.C.; Zagonel, A.A.; Glass, R.J. Extending Opinion Dynamics to Model Public Health Problems and Analyze Public Policy Interventions. In Proceedings of the 29th Intl Conf of the System Dynamics Society; Citeseer-NECSI ICCS: Sandia National Laboratories, USA, 2011; Vol. 1, pp. 1–15.

- Funk, S.; Gilad, E.; Watkins, C.; Jansen, V.A. The spread of awareness and its impact on epidemic outbreaks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 6872–6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Chapman, G.B.; Galvani, A.P. Integrating epidemiology, psychology, and economics to achieve HPV vaccination targets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 19018–19023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J.M.; Parker, J.; Cummings, D.; Hammond, R.A. Coupled contagion dynamics of fear and disease: mathematical and computational explorations. PloS One 2008, 3, e3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, N. Capturing human behaviour. Nature 2007, 446, 733–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I. Why social epidemiology? Australasian Epidemiologist 2000, 7, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, W.; Ren, R.; Paré, P.E.; Ye, M.; Ruf, S.; Liu, J. On a network SIS model with opinion dynamics. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 2582–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, B.; Leung, H.C.; Sundaram, S.; Paré, P.E. Peak Infection Time for a Networked SIR Epidemic with Opinion Dynamics, 2021. doi:arXiv:2109.14135.

- Liang, D.; Yi, B.; Xu, Z. Opinion dynamics based on infectious disease transmission model in the non-connected context of Pythagorean fuzzy trust relationship. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2021, 72, 2783–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestereich, A.L.; Pires, M.A.; Crokidakis, N. Three-state opinion dynamics in modular networks. Physical Review E 2019, 100, 032312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, S.; Panja, S. Influence of opinion dynamics to inhibit epidemic spreading over multiplex network. IEEE Control Systems Letters 2020, 5, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, R.; Chmiel, A. Role of Time Scales in the Coupled Epidemic-Opinion Dynamics on Multiplex Networks. Entropy 2022, 24, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.; Khan, M.F.; Hasrat, M.N.; Richwagen, N.; others. Transmission frequency of COVID-19 through pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in AJK: a report of 201 cases. Virology Journal 2021, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, M.A.; Quandelacy, T.M.; Kada, S.; Prasad, P.V.; Steele, M.; Brooks, J.T.; Slayton, R.B.; Biggerstaff, M.; Butler, J.C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission from people without COVID-19 symptoms. JAMA Network Open 2021, 4, e2035057–e2035057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.U.; Pybus, O.G.; Fraser, C.; Cauchemez, S.; Rambaut, A.; Cowling, B.J. Monitoring key epidemiological parameters of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nature Medicine 2021, 27, 1854–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzberger, B.; Buder, F.; Lampl, B.; Ehrenstein, B.; Hitzenbichler, F.; Holzmann, T.; Schmidt, B.; Hanses, F. Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. Infection 2021, 49, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homma, Y.; Katsuta, T.; Oka, H.; Inoue, K.; Toyoshima, C.; Iwaki, H.; Yamashita, Y.; Shinomiya, H. The incubation period of the SARS-CoV-2 B1. 1.7 variant is shorter than that of other strains. Journal of Infection 2021, 83, e15–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ni, W.; Wang, Z.; Ma, G.; Pan, B.; Dong, L.; Gao, R.; Jiang, F. The distribution of SARS-CoV-2 contamination on the environmental surfaces during incubation period of COVID-19 patients. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 208, 111438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.E.; Jeong, H.S.; Yu, Y.; Shin, S.U.; Kim, S.; Oh, T.H.; Kim, U.J.; Kang, S.J.; Jang, H.C.; Jung, S.I.; others. Viral kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 in asymptomatic carriers and presymptomatic patients. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 95, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Rayner, S.; Luo, M.H. Does SARS-CoV-2 has a longer incubation period than SARS and MERS? Journal of medical virology 2020, 92, 476–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, O.; Campos-Mercade, P.; Meier, A.N.; Wengström, E. Anticipation of COVID-19 vaccines reduces willingness to socially distance. Journal of Health Economics 2021, 80, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Ozair, M.; Ali, F.; ur Rehman, S.; Assiri, T.A.; Mahmoud, E.E. Sensitivity analysis and optimal control of COVID-19 dynamics based on SEIQR model. Results in Physics 2021, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerberry, D.J.; Milner, F.A. An SEIQR model for childhood diseases. Journal of Mathematical Biology 2009, 59, 535–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpen, W.; Wiwatanapataphee, B.; Wu, Y.; Tang, I. A SEIQR model for pandemic influenza and its parameter identification. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 2009, 52, 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Tovissodé, C.F.; Doumatè, J.T.; Glèlè Kakaï, R. A Hybrid Modeling Technique of Epidemic Outbreaks with Application to COVID-19 Dynamics in West Africa. Biology 2021, 10, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iboi, E.A.; Sharomi, O.O.; Ngonghala, C.N.; Gumel, A.B. Mathematical modeling and analysis of COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria, 2020.

- Taboe, H.B.; Salako, K.V.; Tison, J.M.; Ngonghala, C.N.; Kakaï, R.G. Predicting COVID-19 spread in the face of control measures in West Africa. Mathematical Biosciences 2020, 328, 108431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hethcote, H.; Zhien, M.; Shengbing, L. Effects of quarantine in six endemic models for infectious diseases. Mathematical Biosciences 2002, 180, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iachini, T.; Frassinetti, F.; Ruotolo, F.; Sbordone, F.L.; Ferrara, A.; Arioli, M.; Pazzaglia, F.; Bosco, A.; Candini, M.; Lopez, A.; others. Social distance during the COVID-19 pandemic reflects perceived rather than actual risk. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, R.; Wessels, M.; Bernhard, C.; Thönes, S.; von Castell, C. Physical distancing and the perception of interpersonal distance in the COVID-19 crisis. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier-Cottin, E.P.; Ashbaugh, H.; Brooke, N.; Gavazzi, G.; Santillana, M.; Burlet, N.; Tin Tin Htar, M. Communicating benefits from vaccines beyond preventing infectious diseases. Infectious Diseases and Therapy 2020, 9, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, D.E.; Cadarette, D.; Ferranna, M. The societal value of vaccination in the age of COVID-19. American Journal of Public Health 2021, 111, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Driessche, P.; Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Mathematical Biosciences 2002, 180, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, S.H.; Mansatta, K.; Mallett, G.; Harris, V.; Emary, K.R.; Pollard, A.J. What defines an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine? A review of the challenges assessing the clinical efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. The lancet infectious diseases 2021, 21, e26–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, V.J.; Foulkes, S.; Saei, A.; Andrews, N.; Oguti, B.; Charlett, A.; Wellington, E.; Stowe, J.; Gillson, N.; Atti, A.; others. COVID-19 vaccine coverage in health-care workers in England and effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection (SIREN): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. The Lancet 2021, 397, 1725–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.G.; Klepac, P.; Liu, Y.; Prem, K.; Jit, M.; Eggo, R.M. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nature medicine 2020, 26, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omori, R.; Matsuyama, R.; Nakata, Y. The age distribution of mortality from novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) suggests no large difference of susceptibility by age. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, M.; Blenkinsop, A.; Xi, X.; Hebert, D.; Bershan, S.; Tietze, S.; Baguelin, M.; Bradley, V.C.; Chen, Y.; Coupland, H.; others. Age groups that sustain resurging COVID-19 epidemics in the United States. Science 2021, 371, eabe8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadarangani, M.; Raya, B.A.; Conway, J.M.; Iyaniwura, S.A.; Falcao, R.C.; Colijn, C.; Coombs, D.; Gantt, S. Importance of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy in older age groups. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2020–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid, D.; Visseaux, B.; Kassasseya, C.; Daoud, A.; Fémy, F.; Hermand, C.; Truchot, J.; Beaune, S.; Javaud, N.; Peyrony, O.; others. Comparison of patients infected with Delta versus Omicron COVID-19 variants presenting to Paris emergency departments: a retrospective cohort study. Annals of internal medicine 2022, 175, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.A.; Dargham, S.R.; Tang, P.; Chemaitelly, H.; Hasan, M.R.; Coyle, P.V.; Kaleeckal, A.H.; Latif, A.N.; Loka, S.; Shaik, R.M.; others. COVID-19 disease severity in persons infected with the Omicron variant compared with the Delta variant in Qatar. Journal of global health 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, E.B.; Talaat, K.R.; Sabharwal, C.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Paulsen, G.C.; Barnett, E.D.; Muñoz, F.M.; Maldonado, Y.; Pahud, B.A.; others. Evaluation of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in children 5 to 11 years of age. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 386, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.C.; Singer, B. Prioritizing COVID-19 vaccination by age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubar, K.M.; Reinholt, K.; Kissler, S.M.; Lipsitch, M.; Cobey, S.; Grad, Y.H.; Larremore, D.B. Model-informed COVID-19 vaccine prioritization strategies by age and serostatus. Science 2021, 371, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, S.; Rao, A.; Shahid, N.; Yaqoob, A.; Samiullah, T.; Shakoor, S.; Latif, A.; Tabassum, B.; Khan, M.; Shahid, A.; others. Role of oral vaccines as an edible tool to prevent infectious diseases. Acta Virol 2019, 63, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seib, K.L.; Dougan, G.; Rappuoli, R. The key role of genomics in modern vaccine and drug design for emerging Infectious Diseases. PLoS Genetics 2009, 5, e1000612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.B.; Schwartz, I.B. Enhanced vaccine control of epidemics in adaptive networks. Physical Review E 2010, 81, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanette, D.H.; Kuperman, M. Effects of immunization in small-world epidemics. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2002, 309, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhu, Y.; Qi, C.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; She, K.; Jia, Y.; Liu, T.; He, D.; others. Estimating the Prevalence of Asymptomatic COVID-19 Cases and Their Contribution in Transmission-Using Henan Province, China, as an Example. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, P.; Guha, A.; Bandyopadhyay, T. Application of pooled testing in estimating the prevalence of COVID-19. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology 2021, pp. 1–29.

- Ceylan, Z. Estimation of COVID-19 prevalence in Italy, Spain, and France. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 729, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Yao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X. Estimating the prevalence and mortality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the USA, the UK, Russia, and India. Infection and Drug Resistance 2020, 13, 3335–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.G.; Meneghini, M. Quantifying undetected COVID-19 cases and effects of containment measures in Italy: Predicting phase 2 dynamics, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Martcheva, M. An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology, 1st ed.; Vol. 61, Texts in Applied Mathematics, Springer New York, 2015.

- May, R.M. Stability and Complexity in Model Ecosystems. (MPB-6) (Monographs in Population Biology); Princeton University Press, 1973.

- Castillo-Chavez, C.; Feng, Z.; Huang, W. On the computation of R0 and its role on global stability. The IMA Volumes in Mathematics and Its Applications 2002, 125, 229–250. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng-Cheng, Zhu and Jiang, Zhu and Xiao-Lan Liu. Influence of spatial heterogeneous environment on long-term dynamics of a reaction-diffusion S VIR epidemic model with relapse. Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Technical Sciences 2019, 16, 5897–5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.L. Monotone dynamical systems: An introduction to the theory of competitive and cooperative systems; Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, AMS, 2008.

- Krasnoselskii, M.A. Positive Solutions of Operator Equations; Noordhoff. Groningen, 1964.

- Hethcote, H.W.; Thieme, H.R. Stability of the Endemic Equilibrium in Epidemic Models with Subpopulations. Mathematical Biosciences 1985, 75, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazenc, F. Strict Lyapunov functions for time-varying systems. Automatica 2003, 39, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, B.; Wegner, S.A. Variations on Barbălat’s lemma. The American Mathematical Monthly 2016, 123, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description | Values | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total recruitment rate (births and net immigration) | 35,615.35 | [57] | |

| Recruitment rate of non vaccinated individuals | Assumed | ||

| Recruitment rate of vaccinated individuals () | Assumed | ||

| * | Recruitment rate of susceptibles with opinion i | ||

| * | Recruitment rate of susceptibles with opinions i and l | ||

| Natural death rate | [57] | ||

| ** | Baseline contact rate with infectious () | ||

| ** | Contact rate with an infectious with opinion i | ||

| Prophylaxy-induced infection rate reduction factor | 0.5 | [22] | |

| Exit rate from incubation state (inverse of duration) | |||

| Exit rate from presymptomatic state | |||

| Probability of early detection (presymptomatic stage) | |||

| Proportion of symptomatic infectious | |||

| ** | Detection rate of infectious () | ||

| ** | Recovery rate of infectious () | ||

| ** | Disease-related death rate of infectious () | ||

| Lost rate of disease-induced immunity | 0.011 | ||

| * | Part of recovered individuals with opinion i | ||

| * | Part of recovered individuals with opinions i and l | ||

| Vaccination rate | 0.2 | Assumed | |

| Average efficacy of available vaccines | 0.65 | Assumed | |

| Lost rate of vaccine-induced immunity | 0.015 | Assumed | |

| Baseline influence rate (when disease is not perceived) | 0.1 | [22] | |

| Skewness parameter of influence functions | 2 | Assumed | |

| Half-influence saturation constant | 0.1 | [22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).