Submitted:

26 January 2024

Posted:

29 January 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Limitations of quantum field theory

3. Unveiling Dirac belt trick

4. Dirac field theory and its associated features

- ⇒

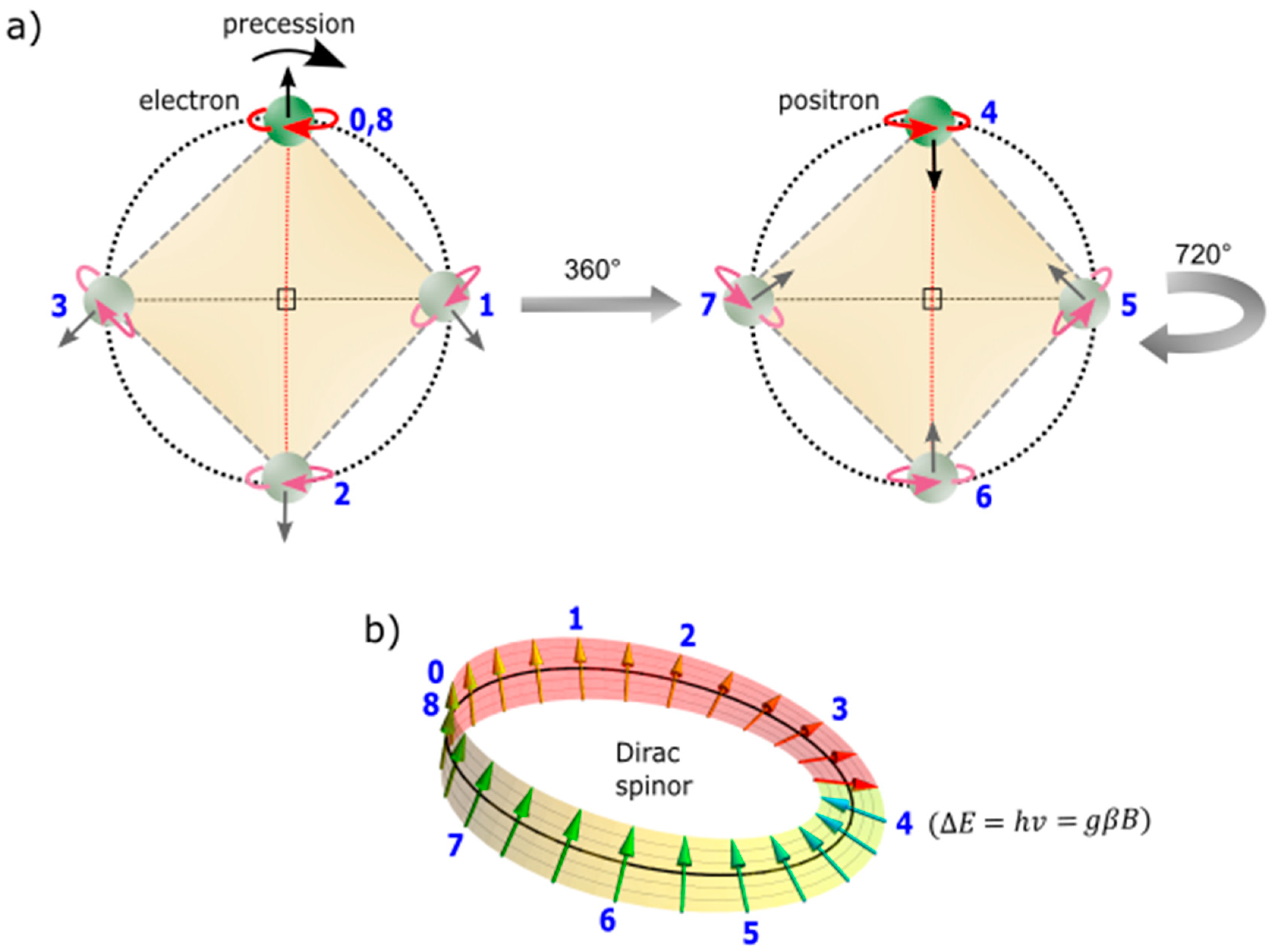

- Discrete symmetries. The electron of a body spinning about an axis (isospin) offers chiral symmetry to the model. Its transformation to Dirac fermion field, and its vector gauge invariance exhibit chiral symmetry by the relationships,

- ⇒

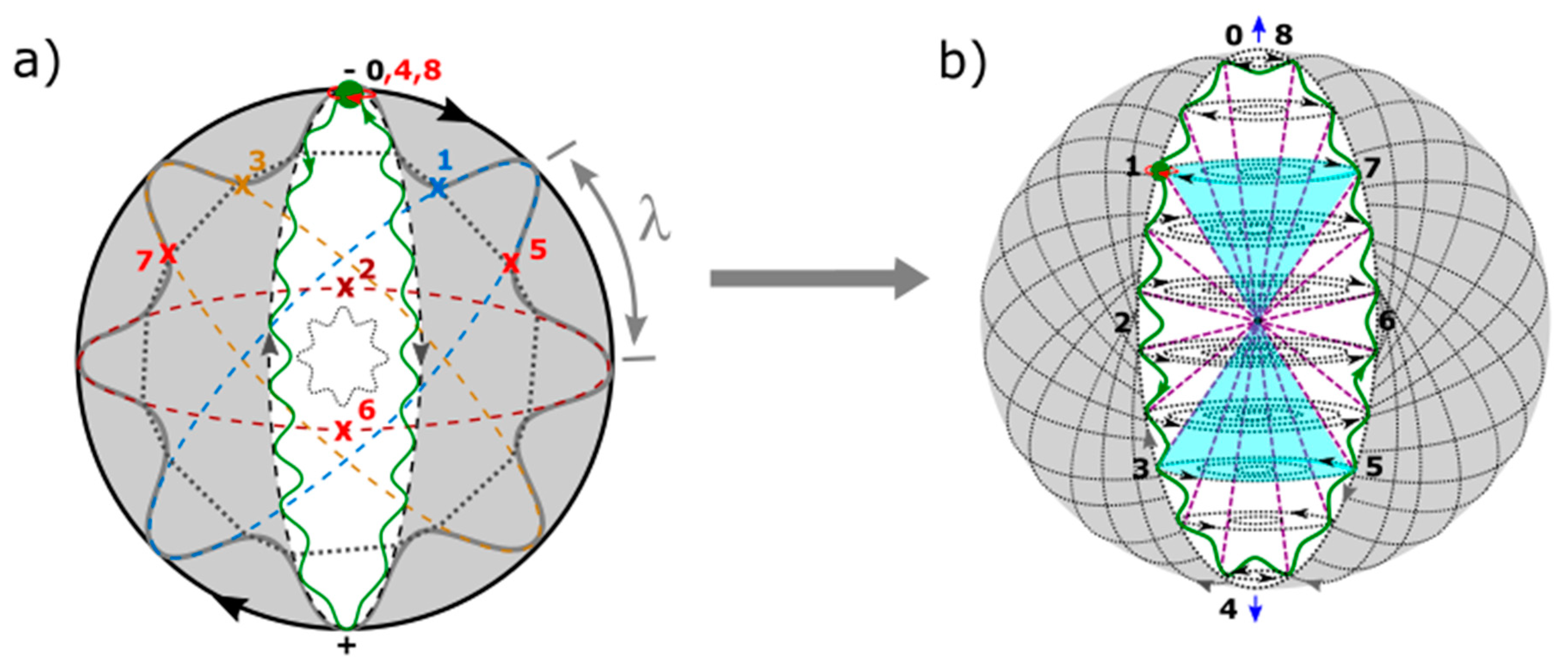

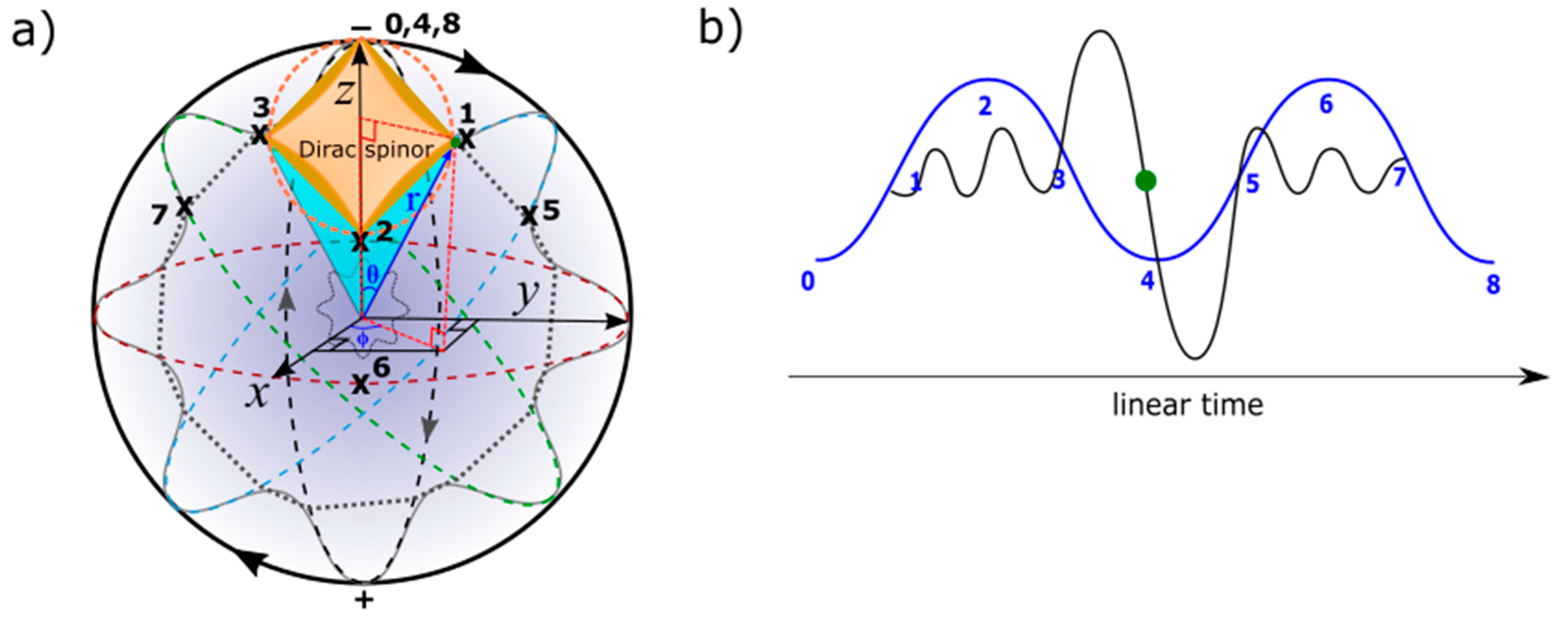

- Space-time dynamics. Dirac fermion or spinor is denoted ψ(x) in 3D Euclidean space and it is superimposed onto the MP model of Minkowski space-time, ψ(x,t) by clockwise precession of the MP field (Figure 3a). Space itself is devoid of any reference points and thus, the Dirac four-component spinor, is attributed to a 3D object (electron) in orbit, and it sustains the arrow of time as the principle axis of the MP field in asymmetry, at the point-boundary. Positions 0 to 3 are hermitian conjugates of positions 4 to 7 and the electron is restored at position 8. Their translation to linear time of Fourier transform is offered in Figure 3b.

- ⇒

- Non-relativistic wave function. The point-boundary at singularity identifies with Planck length. Observation by light-matter interaction allows for the emergence of the model from the point-boundary and this generates complex fermions, ±1/2, ±3/2, ±5/2 and so forth at the energy shells of BOs (Figure 4a). Their orbitals of 3D are defined by total angular momentum, and this incorporates both orbital angular momentum, l and spin, s. From a hemisphere, the model is transformed to a classical oscillator. By clockwise precession, a holographic oscillator from the other hemisphere of the MP field remains hidden. One oscillator levitates about the other (Figure 4b) and both are not simultaneously accessible to observation due to constraints placed by the electron as a physical entity and the influence of its orbit from clockwise precession. The n-levels or shells for the fermions can be pursued for Fermi-Dirac statistics with the point-boundary assigned to zero-point energy (ZPE). Likewise, splitting (Figure 4a) can apply to Landé interval rule due to the electron isospin and this can accommodate lamb shift and thus, hyperfine structure constant. Such scenario is comparable to how vibrational spectra of a harmonic oscillator for diatoms like hydrogen molecule incorporates rotational energy levels. The quantum nature of the classical oscillator is also relevant to the spherical coordinates for the interpretation of Schrödinger wave equation (Figure 4a).

- ⇒

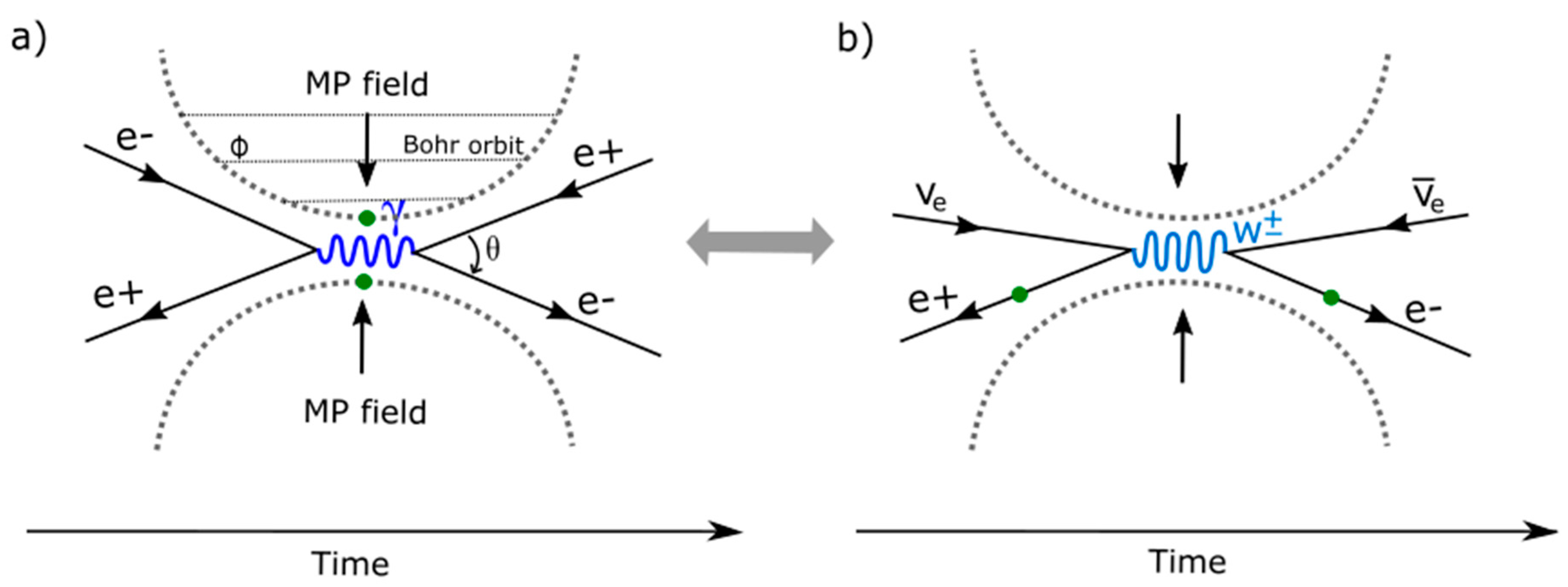

- Feynman diagram and CPT symmetry breaking. Feynman diagrams of path integrals incorporate both matter and antimatter coupling and annihilation processes. These can demonstrate the paths of m = 0 at unitarity to m > 0 for symmetry breaking. When two electrons from a pair of MP models (ionized hydrogen molecules or atoms) approach each other, both attraction and repulsion can occur due to electron-positron transition at the point-boundary. Secondary photons mimicking the electron-positron pair can acquire mass with unitarity sustained (Figure 5a). Ejection of an electron (or positron) by beta decay, would insinuate particle-hole of isospin mimicking up and down quarks (Figure 5b). These interpretations are consistent with the transformation of the electron of isospin to Dirac fermion (Figure 2a). Particle-hole coupling can lead to W± bosons and neutrinos and antineutrinos of helical property mimicking the electron-positron pair without requiring change of color charges by exchange of gluons from up and down quarks. In this case, the vertices of the MP models assume center of mass and ejection of the electron/positron may constitute violation of charge conjugation, parity and time reversal symmetry. The suggestion is also made for the bosons of neutral charge and whole integer spin would amass at ZPE of the point-boundary of a classical oscillator (Figure 4a). The difference in mass of the bosons by mass-energy equivalence such as for W± can be attributed to constriction and relaxation of the model into n-dimensions or energy shells. Any scatterings at the n-dimensions (Figure 4a) can accommodate the fine-structure constant, and it is applicable to high energy at .

- ⇒

-

Dirac field. The fermion field is defined by the famous Dirac equation of the generic form,where are the gamma matrices related to the shifts in the electron’s position by clockwise precession acting on its orbit. The exponentials of the matrices, are assumed by the electron of 3D object. is assigned to the vertex of the MP field due to radiation from the electron-positron transition at position 0 and somewhat sustains arrow of time in asymmetry. The variables are of Dirac matrices and these are applicable to the electron of 3D object and shift in its position. The orthogonal projections of the space-time variables, within a hemisphere are assigned to a light cone (Figure 4a). These are all incorporated into the famous Dirac equation,where c acts on the coefficients A, B and C and transforms them to and . Alternatively, the exponentials of are denoted i, where is off-diagonal Pauli matrices assigned to a pair of light cones in Minkowski space-time (Figure 1b and Figure 4b). It is defined by,and zero exponential, as,

- ⇒

- Weyl spinor. The light cone from the point-boundary within a hemisphere accommodates both matter and antimatter by parity transformation to generate Dirac spinor (Figure 4b). It is described in the form,and it correspond to spin up fermion, a spin down fermion, a spin up antifermion and aspin down antifermion. The electron’s shift in positions from 0 to 3 and 4 to 7 are conjugates before its restoration at the point-boundary as the base of Hilbert space for the MP field. By assuming its own antimatter within a light cone of a hemisphere, the Dirac fermion somewhat resembles Majorana fermions. It is difficult to observe them due to shift in the electron position by clockwise precession. Non-relativistic Weyl spinor of a pair of light cones relevant to Schrödinger wave equation are of holographic type (Figure 4a,b). These are defined by the reduction of Equation (10) to bispinor of the type,where are Weyl spinors of chiral form attributed to the electron of a physical entity. Hence, its parity operation x → x’ = (t, ‒ x) generates qubit 1 and −1 at the vertices of the MP field (Figure 1a and Figure 3a). Depending on the reference point-boundary, the exchanges of left- and right-handed Weyl spinor are of the process,Conversion of Weyl spinors to Dirac bispinor, are assumed diagonally at positions 1 and 3 (Figure 4a). Comparably, the two-component spinor, = 1 are normalized at the point-boundaries of the MP model and ensues the orthogonal relationship, and .

- ⇒

- Lorentz transformation. The Hermitian pair, of Dirac fermion transiting at positions, 0, 1, 2 and 3 of BOs is not Lorentz invariant in 1D space (e.g., Figure 2b) due to radiation from electron-positron transition at the point-boundary. The same applies to Weyl spinor at spherical lightspeed due to the existence of the electron of chirality (Figure 4a). Thus, Lorentz transformation of Weyl spinor depicts the relationship,

- ⇒

- Further undertakings. The themes provided above with respect to Dirac field theory and its related features can be further pursued into depth with the model serving as an approximate intuitive guide. The list could extend to include others such as energy-momentum tensor of Dirac field, Fermi-Dirac statistics, Bose-Einstein statistics, causality, Feynman propagator, charge conjugate-parity-time symmetry and so forth.

5. Conclusion

Data availability statement

Competing financial interests

References

- Peskin, M. E. & Schroeder, D. V. An introduction to quantum field theory. Addison-Wesley, Massachusetts, USA (1995). pp 13–25, 40–62.

- Alvarez-Gaumé, L. & Vazquez-Mozo, M. A. Introductory lectures on quantum field theory. arXiv preprint hep-th/0510040 (2005).

- Pawłowski, M. et al. Information causality as a physical principle. Nature 461(7267), 1101-1104 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Henson, J. Comparing causality principles. Stud. Hist. Philos M. P, 36(3), 519-543 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Y. Elementary analysis of interferometers for wave—particle duality test and the prospect of going beyond the complementarity principle. Chin. Phys. B 23(11), 110309 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, M. Examination of wave-particle duality via two-slit interference. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 9(13), 763-789 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E. Derivation of the Schrödinger equation from Newtonian mechanics. Phys. Rev. 150(4), 1079 (1966). [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Space is blue and birds fly through it. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. 376(2123), 20170312 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D. H. Proton decay experiments. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 34(1), 1-50 (1984). [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. Solutions of nonrelativistic Schrödinger equation from relativistic Klein–Gordon equation. Phys. Lett. A 374(2), 116-122 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Oshima, S., Kanemaki, S. & Fujita, T. Problems of Real Scalar Klein-Gordon Field. arXiv preprint hep-th/0512156 (2005).

- Bass, S. D., De Roeck, A. & Kado, M. The Higgs boson implications and prospects for future discoveries. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3(9), 608-624 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L. S. et al. Controlled creation of a singular spinor vortex by circumventing the Dirac belt trick. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 1-8 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Silagadze, Z. K. Mirror objects in the solar system?. arXiv preprint astro-ph/0110161 (2001).

- Franzoni, G. The klein bottle: Variations on a theme. Notices of the Am. Math. Soc. 59(8), 1094-1099 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Rieflin, E. Some mechanisms related to Dirac’s strings. Am. J. Phys. 47(4), 379-380 (1979).

- Almasi, A. et al. New limits on anomalous spin-spin interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125(20), 201802 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. N. & Mills, R. Conservation of isotopic spin and isotopic gauge invariance. Phys. Rev. 96, 191 (1954). [CrossRef]

- Gross, D. J. Nobel lecture: The discovery of asymptotic freedom and the emergence of QCD. Rev. Mod. Phys.77(3), 837 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M. & Low, F. E. Quantum electrodynamics at small distances. Phys. Rev. 95(5), 1300 (1954). [CrossRef]

- Arkani-Hamed, N. et al. Solving the hierarchy problem with exponentially large dimensions. Phys. Rev. D 62(10), 105002 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Craig, N. Naturalness hits a snag with Higgs. Physics 13, 174 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yuguru, S. P. Unconventional reconciliation path for quantum mechanics and general relativity. IET Quant. Comm. 3(2), 99–111 (2022). [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spinor Retrieved 15 December 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).