Submitted:

23 January 2023

Posted:

23 January 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

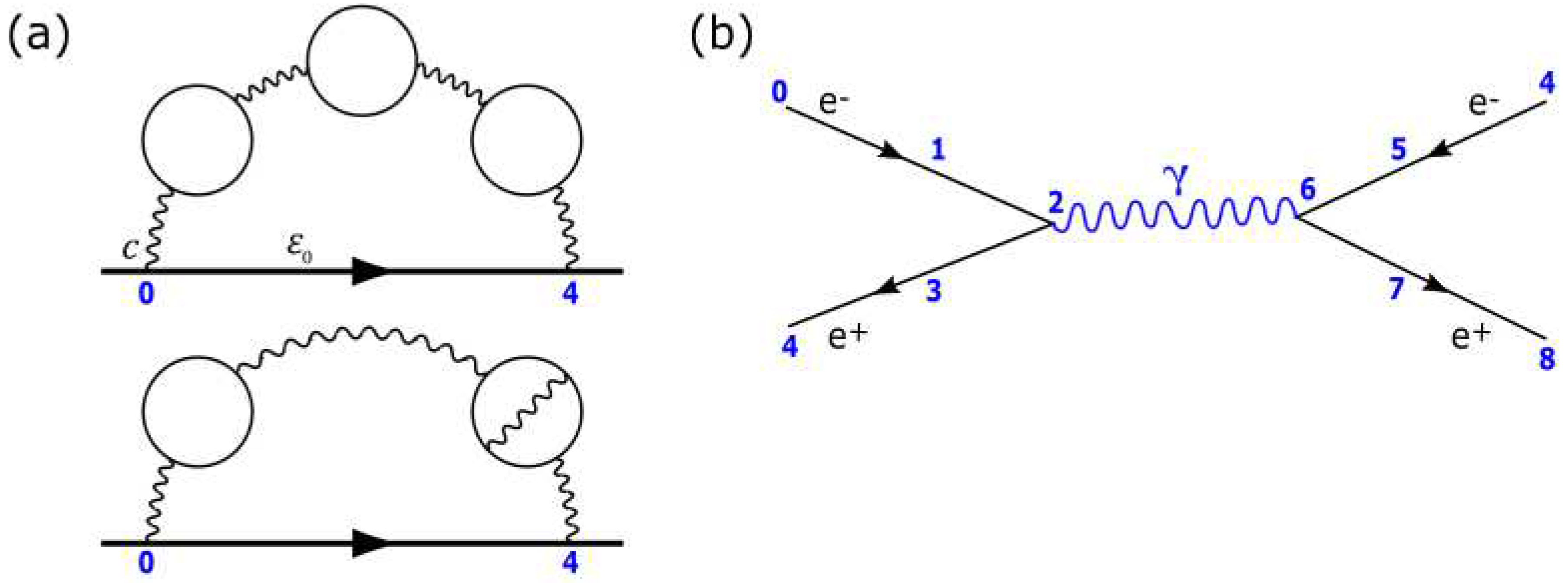

2. Limitations of quantum field theory

3. The conceptualization process

3.1. Euclidean and Minkowski space-times

- 1)

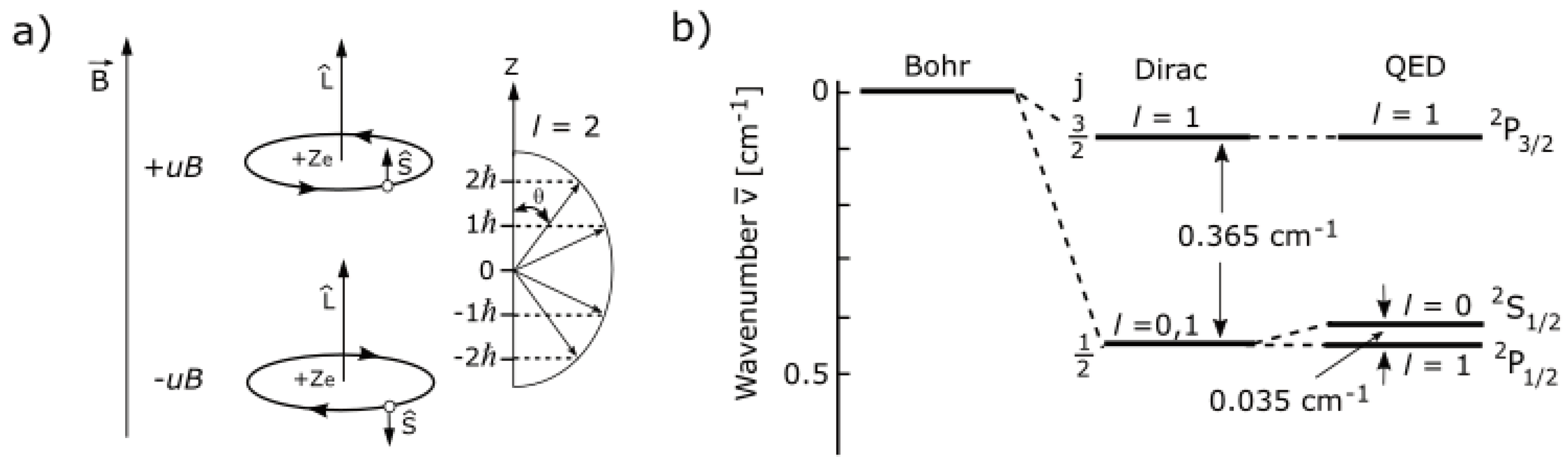

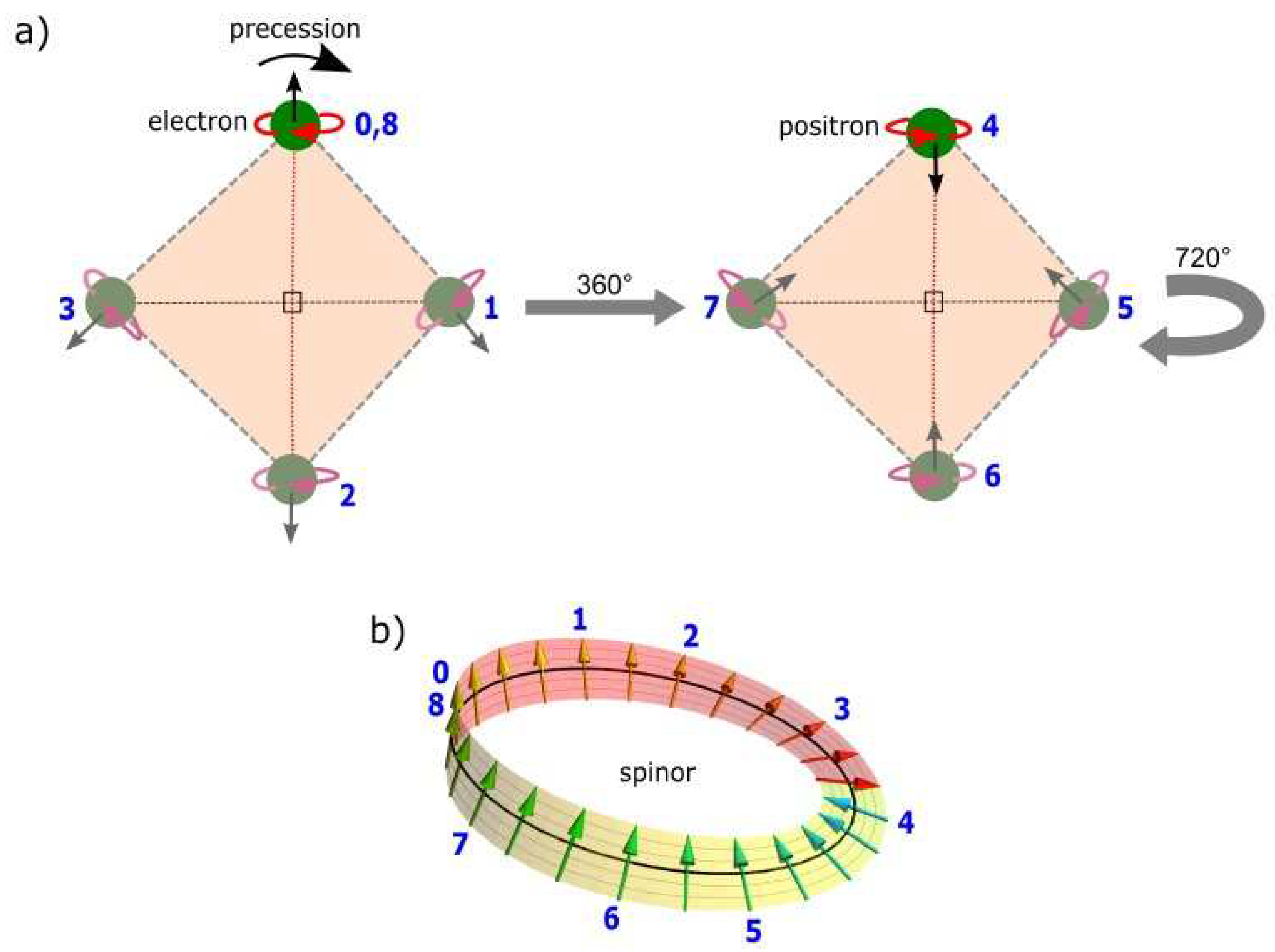

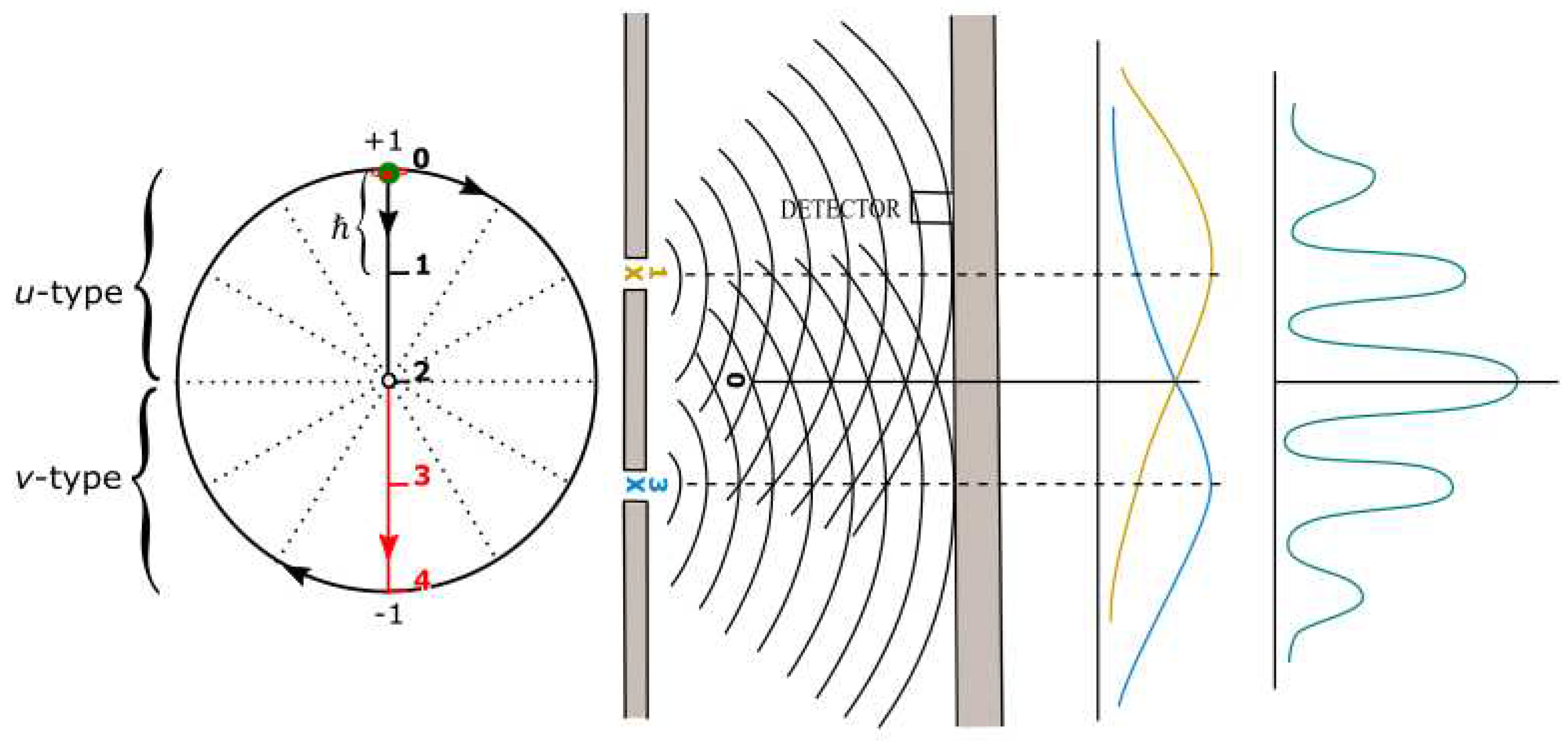

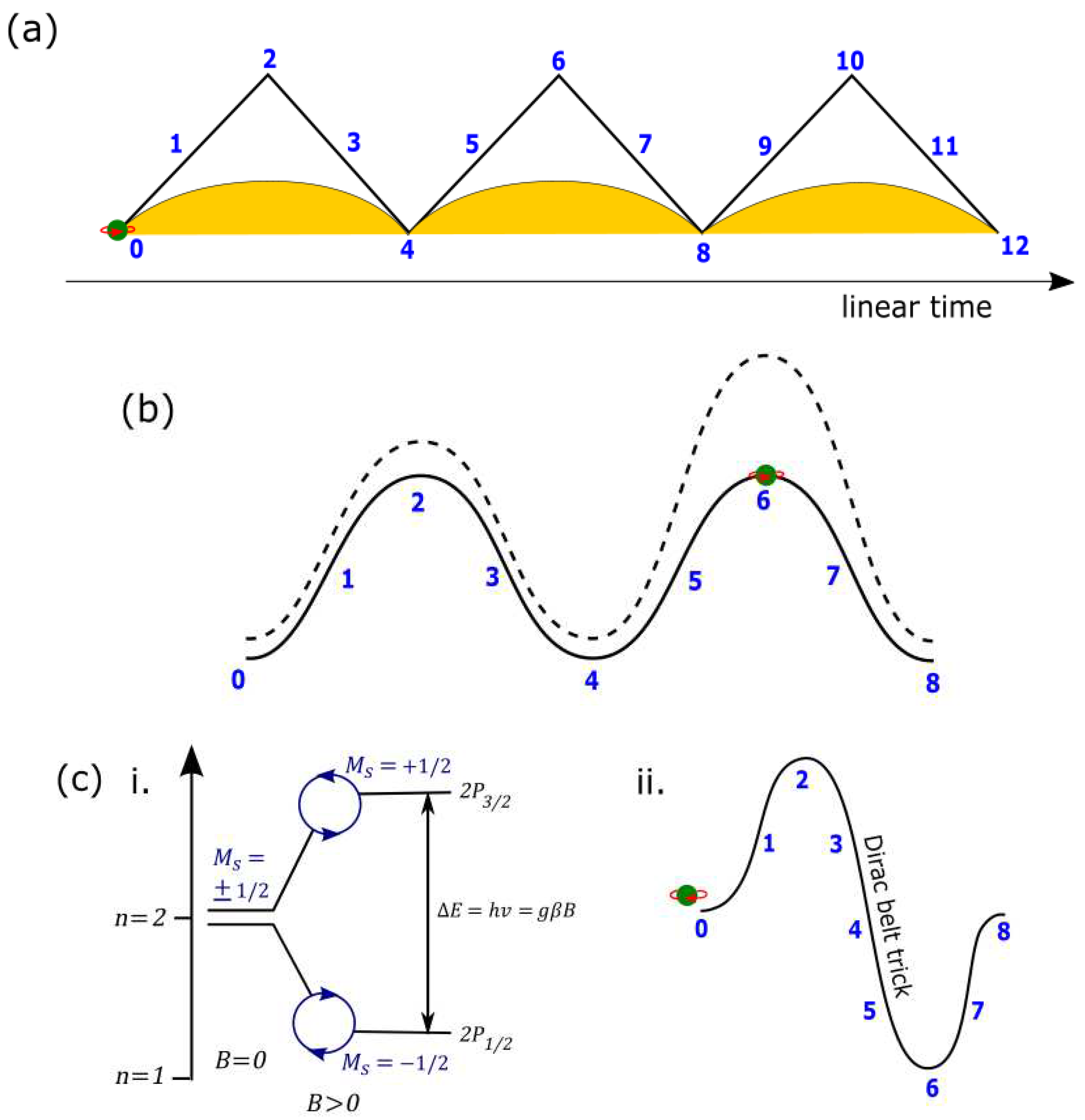

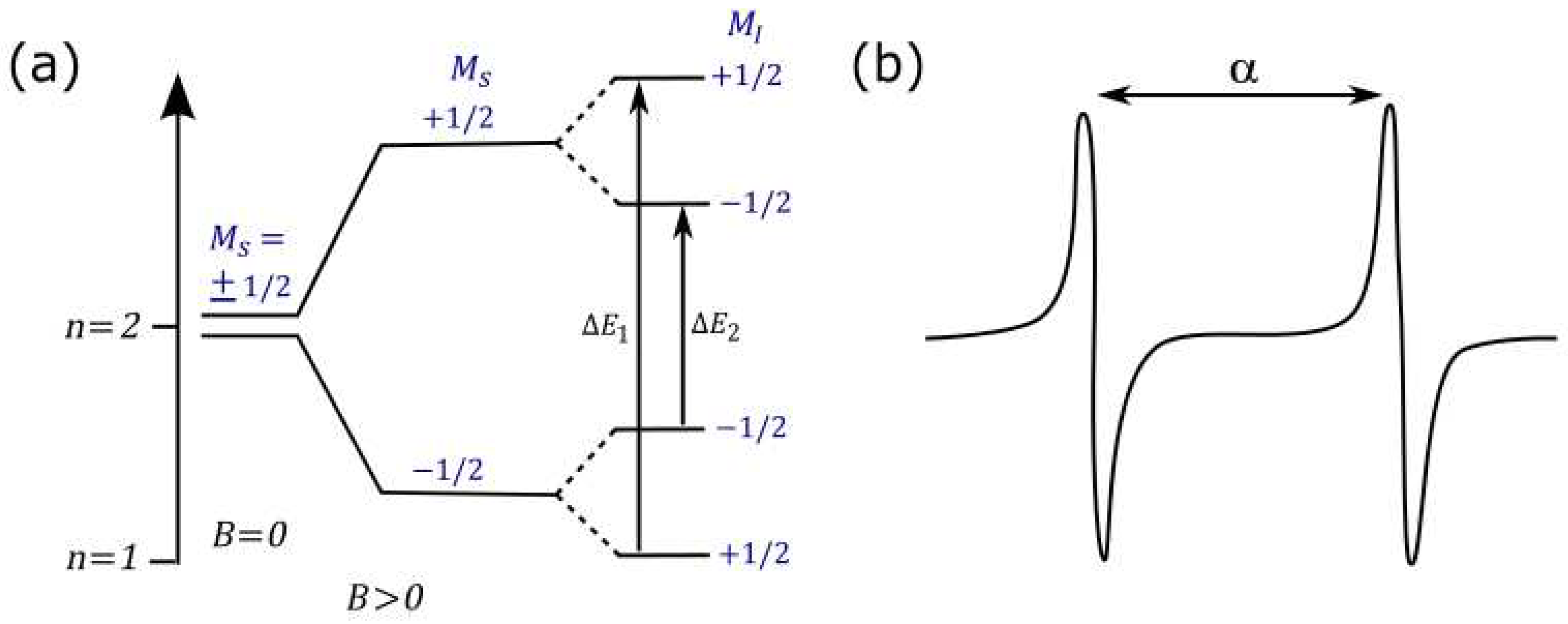

- The electron’s orbit of time reversal is defined by h of sinusoidal wavy form and is linked to Bohr orbits (BOs) into n-dimensions of energy levels. Its transformation to an elliptic form is embedded within a MP field of clockwise precession and this insinuates spherical inertia frame with unitarity, λ sustained. Excitation from external light interaction assumes, , whereas the probability of locating the electron is defined by De Broglie relationship, λ = h/p. From Euclidean space-time, the cyclic BO (e.g., positions 1 and 5) in Figure 1a is transformed to angular momentum in Minkowski space-time (Figure 1b). At 360° rotation from positions 0 to 3, maximum twists from the torque of the BOs provide a complex spinor field. Thus, the electron with spin up flips to spin down at position 4 to generate a positron. The unfolding process for another 360° rotation from positions 5 to 8 restores the electron to its original state. This allows the electron to undergo 720° rotation within a classical spherical rotation of 360° at lightspeed analogous to the Dirac belt trick. Such a scenario offers both local realism and entanglement of electron-positron pairing in violation of lightspeed. In multielectron atoms, multiple MP fields are assumed for the electrons distribution.Figure 1. The MP model [25]. (a) In flat space, a spinning electron’s (green dot) orbit is sinusoidal (green curve) of time reversal. It is embedded within an elliptic MP field (grey area) of a magnetic field, B. Its clockwise precession (black arrows) generates a circular electric field, E of inertia frame defined by λ, and this produces Euclidean 4D space-time. With precession, the electron shifts from positions 0 to 4 at 360° rotation to generate a positron at maximum twists of the BOs. The unfolding process flips the electron to shift in its positions from 5 to 8 for another 360° rotation to assume its original state. In this way, the electron undergoes 720° rotation to assume a dipole moment (±) within a classical spherical rotation of 360° at lightspeed analogous to Dirac belt trick. (b) The BOs defined by the pairings of the numbered positions such as 1,5 and 3,7 translate to angular momentum (purple dotted lines) of spin ±1/2 of a pair of light-cones (navy colored) in Minkowski space-time. This caters for the twisting and unfolding, while the BOs in degeneracy are projected towards singularity at the center.Figure 1. The MP model [25]. (a) In flat space, a spinning electron’s (green dot) orbit is sinusoidal (green curve) of time reversal. It is embedded within an elliptic MP field (grey area) of a magnetic field, B. Its clockwise precession (black arrows) generates a circular electric field, E of inertia frame defined by λ, and this produces Euclidean 4D space-time. With precession, the electron shifts from positions 0 to 4 at 360° rotation to generate a positron at maximum twists of the BOs. The unfolding process flips the electron to shift in its positions from 5 to 8 for another 360° rotation to assume its original state. In this way, the electron undergoes 720° rotation to assume a dipole moment (±) within a classical spherical rotation of 360° at lightspeed analogous to Dirac belt trick. (b) The BOs defined by the pairings of the numbered positions such as 1,5 and 3,7 translate to angular momentum (purple dotted lines) of spin ±1/2 of a pair of light-cones (navy colored) in Minkowski space-time. This caters for the twisting and unfolding, while the BOs in degeneracy are projected towards singularity at the center.

- 2)

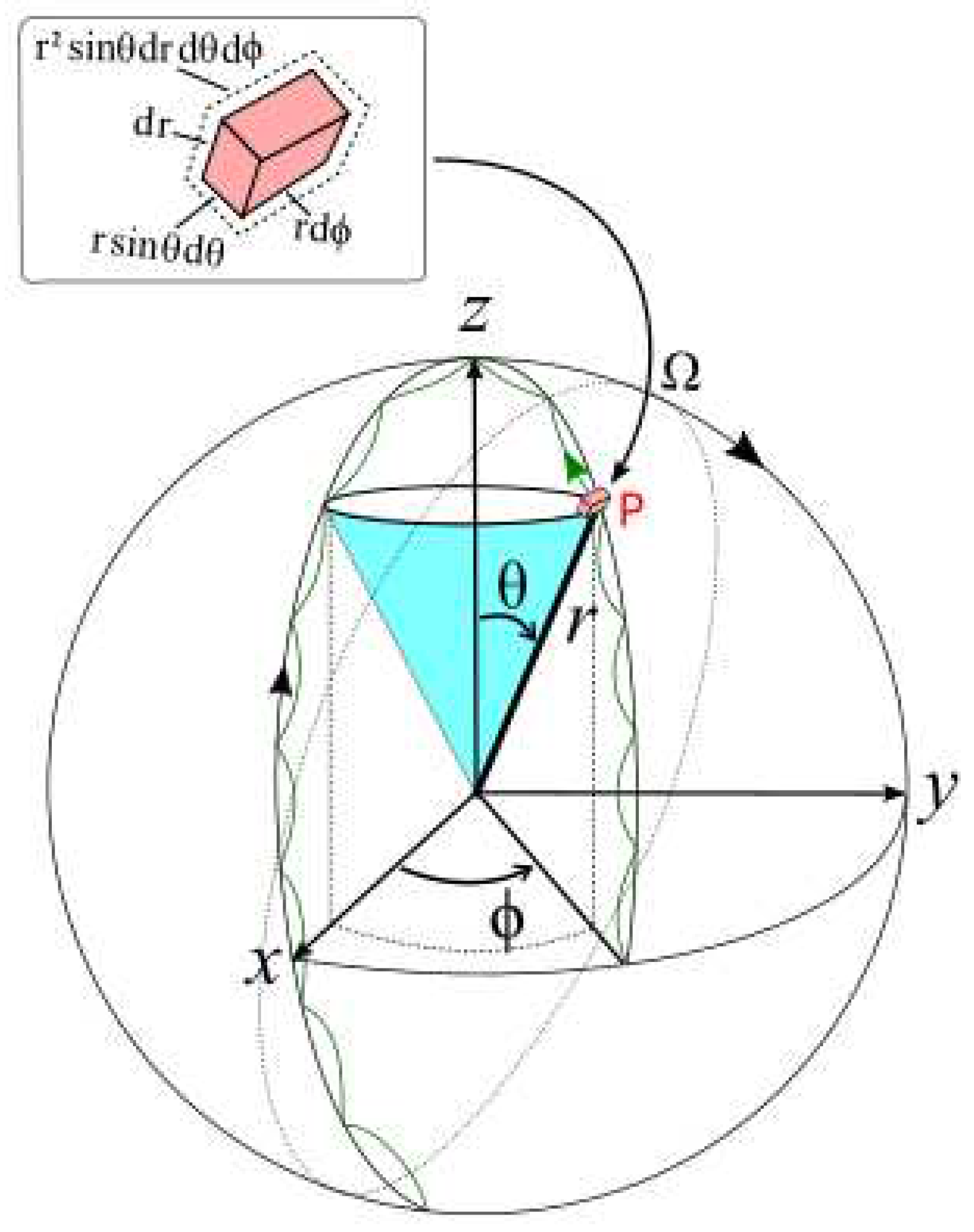

- The electron offers chiral symmetry, where its orthogonal projection, at positions, 0 to 3 is reduced to spin, for the pair of light-cones. Its Hermitian is P(0→8) = with equal to time. The MP model of unitarity gauge obeys the “natural units”, ℏ = c = 1 with the electron’s orbit is accorded to Euler’s formula, + 1 = 0 for continual precession (e.g., Figure 2). Inversion of symmetry at the center violates parity to generate polarization states, ±1 as the dipole moment of MP field. The electron’s position, within a sphere (e.g., Figure 3) incorporates the uncertainty principle, ΔE.Δt ≥ ħ/2 or Δx.Δp ≥ ħ/2 of time invariance. In this way, Schrödinger of an electron cloud model is transformed to a Dirac fermion of a complex four-component spinor field.

- 3)

- The Dirac four-component spinor, assumes its own antimatter at positions, 0, 1, 2 and 3 in Hilbert space when combined with positions 4 to 8 (Figure 1b). The enclosed area defined by the electron shift from positions 0 to 3 is of Euclidean space. Where positions 1 and 3 converge at either position 0 or 2 offers geodesic motion of non-Euclidean space on the surface of the sphere and this somewhat resembles the equivalence principle. By reduction measures such as wave function collapse, only two positions and generate the spin, ±1/2 property of a pair of light-cones. The outcome of the spin is determined by Born’s probabilistic interpretation, , for the wave function collapse scenario (e.g., Figure 3), where the past or future paths of the electron from positions 0 to infinity are not accounted for at observations.

3.2. Gravity and multiverse

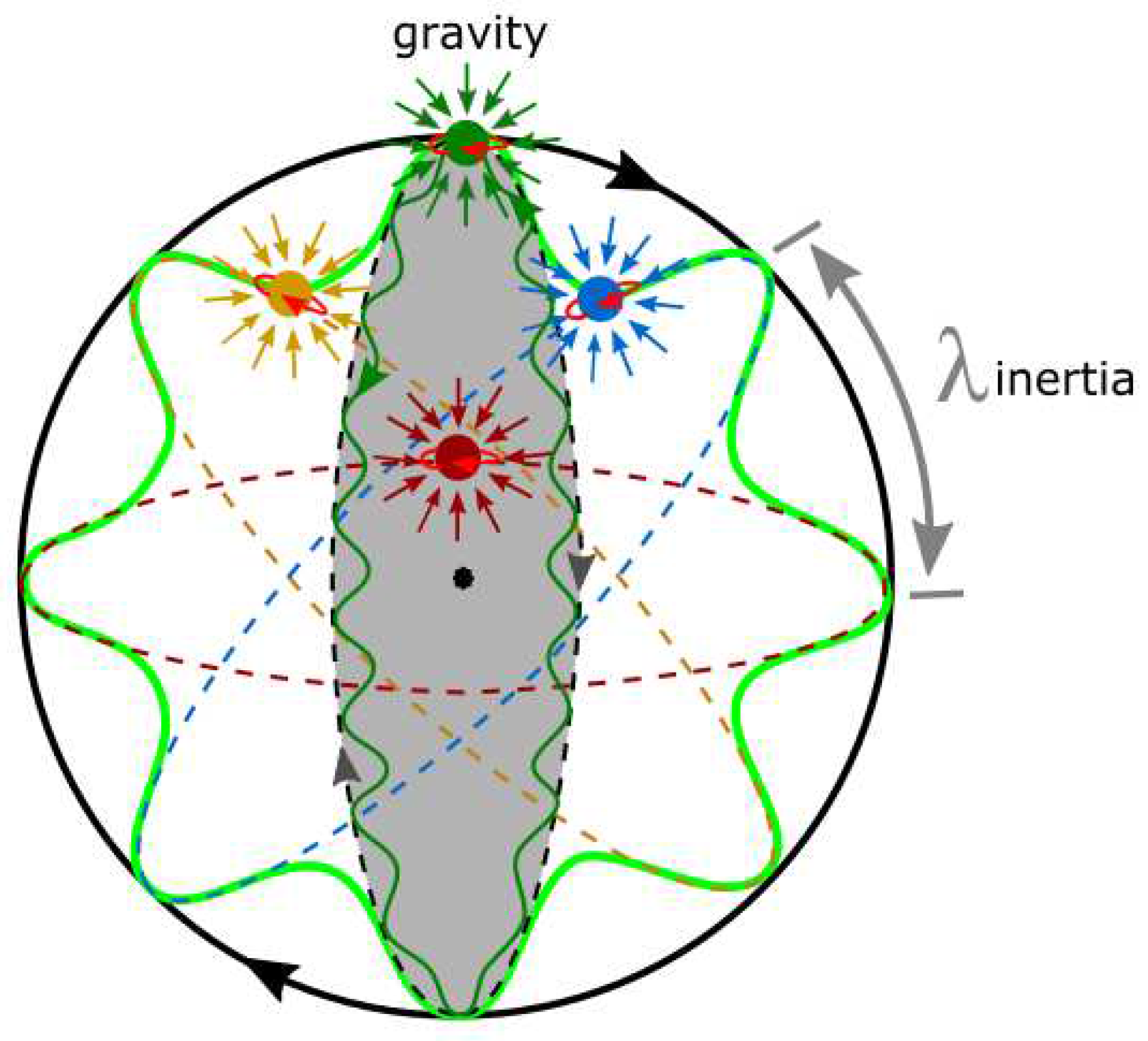

- 4)

- How gravity becomes applicable within the MP model is demonstrated in Figure 2. The electron path of sinusoidal wave is of time reversal. The overriding clockwise precession of the MP field induces spherical inertia frames at lightspeed. The generated outline forms the event horizon of elasticity comparable to a black hole. Any external observations are assumed at lightspeed to overcome the spinning inertia frame of reference. Einsteinian gravity then becomes applicable, where matter curves space-time and space-time tells matter how to move [26]. The metric tensor in Minkowksi space-time of angular momenta in Hilbert space is assumed towards singularity at the center (Figure 1b). Any external light interaction with the electron-positron pair at 720° rotation or 360° spherical rotation can somehow translate to gravitational wave types by conservation of angular momenta with the nucleus confined to a black hole scenario (Figure 2). Spherical polarization from a complementary pair of photons over large distance would generate entanglement. Each clockwise precession stage is defined by Ω of a von Neumann entropy state. The microcanonical ensemble for the entropy, S = k In Ω offers exponential rise with continuous precession and this is approximated to the k value, where the space-time metric tensor along the BOs are also included.

- 5)

- In a multiverse of the models at a hierarchy of energy scales, the procession ensues in the following manner, nucleus => atom => planet => star => galaxy. Though there is clear distinction to matter between the scales such as life on Earth and gluons at the nucleus, it is possible that the space-time structural frame offered by the MP model is about the same. So the relationship of the electron to an atom is comparable to satellite to planet, planet to star and possibly star to galaxy. In this way, electromagnetic field permeates space, whereas observation of the MP model’s structural frame appears to be an emergent property of matter from external light interactions.

- 6)

- At the solar scale, only a segment of the spherical curvature of the model is observed by redshift such as the rotation of Earth during lunar eclipse. For Mercury, its unusual perihelion precession deviates about 43 seconds of arc per century from Newtonian theory and this is well accounted by general relativity [27]. However, the explicit solution is more complex and restricted to a planet, while relativity does not explain how the effect of space-time curvature on the inertia frame by precession reconciles with singularity. If, however, the MP model is considered, each planet’s sinusoidal orbit of time reversal against overall clockwise precession is attained at a n-dimension of the sun at the solar scale [25]. Precession is applicable to all the planets, where distinction can be made wherever possible unlike the microscale. For distal objects, considerable redshifts are expected for light waves propagating in space. Such a possibility could explain rotation of galaxies, gravitational lensing, black hole and so forth when these are not ably catered for by general relativity. So with gravity confined to matter in space, the electromagnetic field permeates a multiverse of the models at a hierarchy of scales.

4. Theoretical outcomes and interpretations

4.1. Chirality of the MP model

4.2. The basis of Schrödinger wave function

4.3. Wave function collapse scenario

5. Implications to the basics of Standard Model

5.1. Electromagnetism and electron spin-orbit splitting

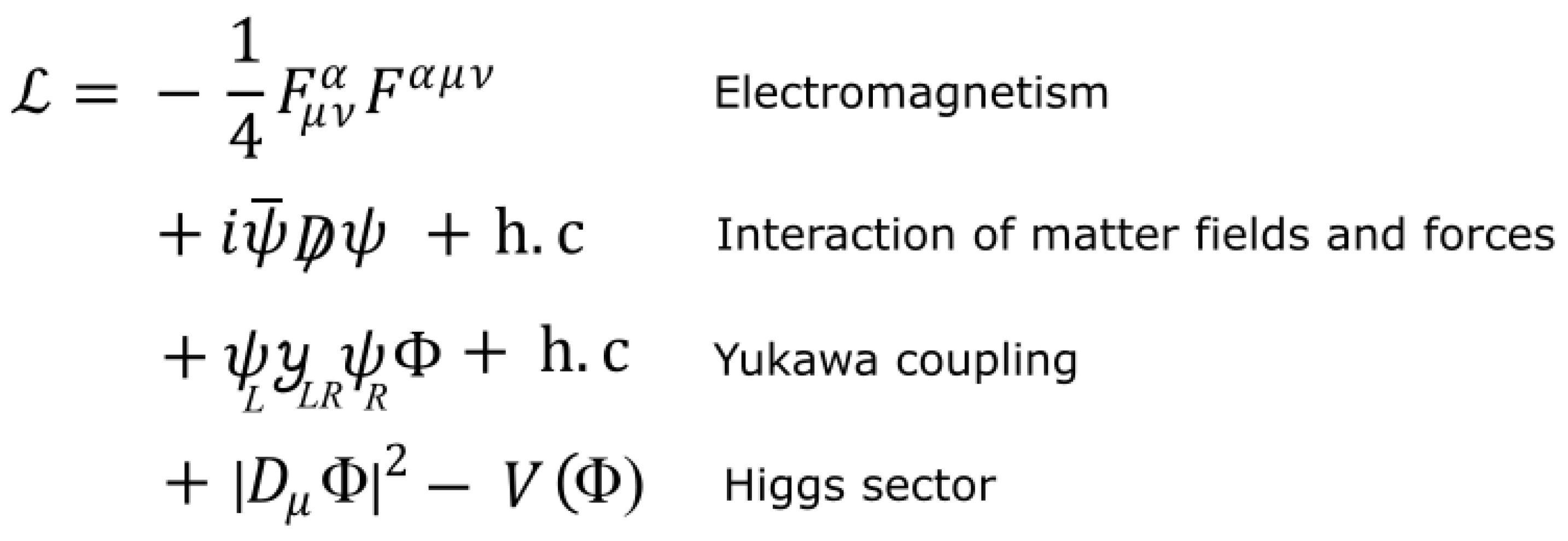

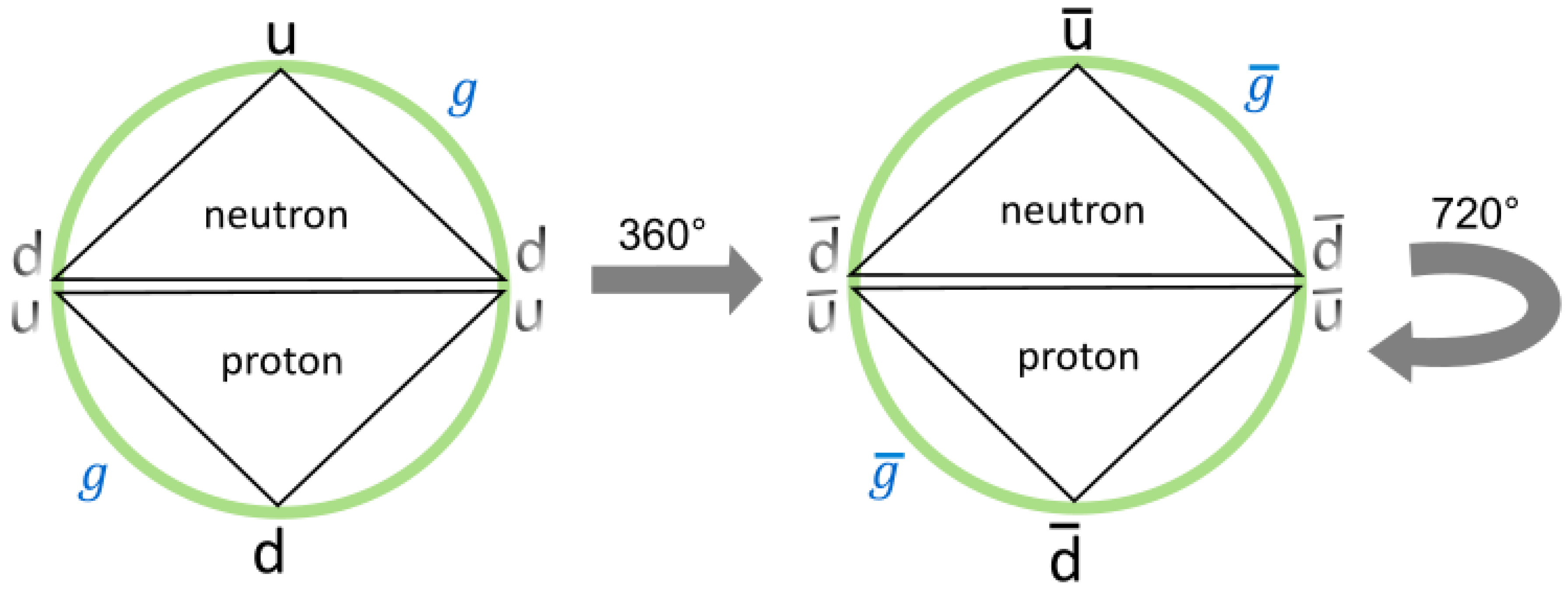

5.2. Nuclear spin and the Standard Model lagrangian

6. Conclusion

Competing financial interests

Appendix A: Electron spin-orbit coupling splitting

Appendix B: Application of Dirac field theory

References

- Peskin, M. E. & Schroeder, D. V. An introduction to quantum field theory. Addison-Wesley, Massachusetts, USA (1995).

- Alvarez-Gaumé, L. & Vazquez-Mozo, M. A. Introductory lectures on quantum field theory. arXiv preprint hep-th/0510040 (2005).

- Pawłowski, M. et al. Information causality as a physical principle. Nature 461(7267), 1101-1104 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Henson, J. Comparing causality principles. Stud. Hist. Philos M. P, 36(3), 519-543 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Y. Elementary analysis of interferometers for wave—particle duality test and the prospect of going beyond the complementarity principle. Chin. Phys. B 23(11), 110309 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, M. Examination of wave-particle duality via two-slit interference. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 9(13), 763-789 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E. Derivation of the Schrödinger equation from Newtonian mechanics. Phys. Rev. 150(4), 1079 (1966). [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Space is blue and birds fly through it. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. 376(2123), 20170312 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D. H. Proton decay experiments. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 34(1), 1-50 (1984). [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. Solutions of nonrelativistic Schrödinger equation from relativistic Klein–Gordon equation. Phys. Lett. A 374(2), 116-122 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Oshima, S., Kanemaki, S. & Fujita, T. Problems of Real Scalar Klein-Gordon Field. arXiv preprint hep-th/0512156 (2005).

- Bass, S. D., De Roeck, A. & Kado, M. The Higgs boson implications and prospects for future discoveries. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3(9), 608-624 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L. S. et al. Controlled creation of a singular spinor vortex by circumventing the Dirac belt trick. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 1-8 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Silagadze, Z. K. Mirror objects in the solar system?. arXiv preprint astro-ph/0110161 (2001).

- Almasi, A. et al. New limits on anomalous spin-spin interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125(20), 201802 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. N. & Mills, R. Conservation of isotopic spin and isotopic gauge invariance. Phys. Rev. 96, 191 (1954). [CrossRef]

- Gross, D. J. Nobel lecture: The discovery of asymptotic freedom and the emergence of QCD. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77(3), 837 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M. & Low, F. E. Quantum electrodynamics at small distances. Phys. Rev. 95(5), 1300 (1954). [CrossRef]

- Arkani-Hamed, N. et al. Solving the hierarchy problem with exponentially large dimensions. Phys. Rev. D 62(10), 105002 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P. Spontaneous symmetry breakdown without massless bosons. Phys. Rev. 145, 1156 (1966). [CrossRef]

- Craig, N. Naturalness hits a snag with Higgs. Physics 13, 174 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M. R. Report on the status of the yang-mills millennium prize problem. Preprint. http://www. claymath. org/millennium/Yang-Mills Theory/ym2.Pdf (2004).

- Howard, D. Who invented the “Copenhagen Interpretation”? A study in mythology. Philos. Sci. 71(5), 669-682 (2004).

- Wineland, D. J. Nobel lecture: Superposition, entanglement, and raising Schrödinger’s cat. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85(3), 1103 (2013).

- Yuguru, S. P. Unconventional reconciliation path for quantum mechanics and general relativity. IET Quant. Comm. 3(2), 99–111 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Misner, C. W., Thorne, K. S & Zurek, W. H. John Wheeler, relativity, and quantum information. Phys. Today 62(4), 40-46 (2009).

- Bootello, J. Angular Precession of Elliptic Orbits. Mercury. Int. J. Astron. Astrophys. 2(4), 249-255 (2012). [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spinor Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- Atkins, P. & de Paula, J. Physical Chemistry. 9th Edition. Oxford University Press, New York (2010).

- Yi, X. et al. Hybrid-order Poincaré sphere. Phys. Rev. A 91(2), 023801 (2015).

- Milione, G. et al. Higher-order Poincaré sphere, Stokes parameters, and the angular momentum of light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107(5), 053601 (2011).

- Rafayelyan, M. & Brasselet, E. Spin-to-orbital angular momentum mapping of polychromatic light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120(21), 213903 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Examples of 8-order Feynman diagrams for electron propagation, Wikimedia Commons https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:EighthOrderMagMoment.svg Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Kragh, H. Magic number: A partial history of the fine-structure constant. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 57(5), 395-431 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Sherbon, M. A. Fundamental nature of the fine-structure constant. Int. J. Phys. Res. 2(1), 1-9 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A. & Ostlund, N. S. Modern quantum chemistry: introduction to advanced electronic structure theory. Courier Corporation, Massachusetts, USA (1996).

- Aspect, A., Grangier, P. & Roger, G. Experimental realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: a new violation of Bell's inequalities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49(2), 91 (1982).

- Pan, J. W. et al. Experimental entanglement swapping: entangling photons that never interacted. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80(18), 3891 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Weil, J. A. & Bolton, J. R. Electron paramagnetic resonance: elementary theory and practical applications. John Wiley & Sons (2007). [CrossRef]

- Lindon, J. C., Tranter, G. E. & Koppenaal, D. Encyclopedia of spectroscopy and spectrometry. Academic Press (2016).

- Woithe, J., Wiener, G. J., & Van der Veken, F. F. Let’s have a coffee with the standard model of particle physics!. Phys. Educ. 52(3), 034001 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J. Outstanding questions: physics beyond the Standard Model. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 370 (1961), 818-830 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Freese, K., Frieman, J. A. & Olinto, A. V. Natural inflation with pseudo Nambu-Goldstone bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65(26), 3233 (1990). [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chirality_(physics) Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Moore, W. Schrӧdinger. Life and thought. Cambridge University Press, London, 1989. p. 513.

- Gabrielse, G. et al. New determination of the fine structure constant from the electron g value and QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97(3), 030802 (2006).

- Consa, O. Something is wrong in the state of QED. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.02078 (2021).

- Hanneke, D. et al. Cavity control of a single-electron quantum cyclotron: Measuring the electron magnetic moment. Phys. Rev. A 83(5), 052122 (2011). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).