Submitted:

06 February 2023

Posted:

07 February 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Umifenovir

3. Neuraminidase Inhibitors

4. M2 Inhibitors (Adamantanes)

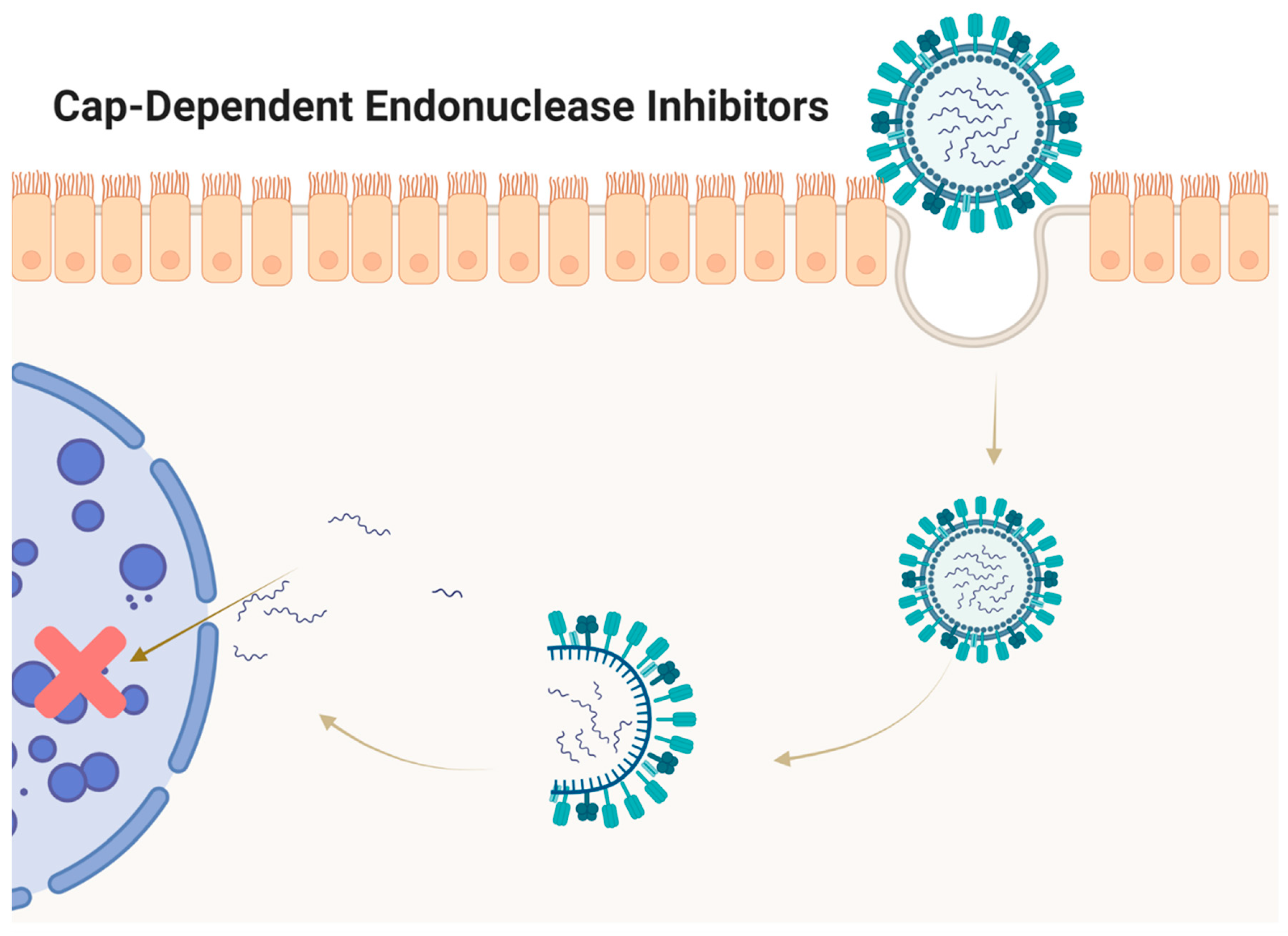

5. Cap-Dependent Endonuclease Inhibitors

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Gaitonde DY, Moore FC, Morgan MK. Influenza: Diagnosis and Treatment. American family physician. 2019;100(12):751-758.

- Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. Influenza: The Once and Future Pandemic. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(3_suppl):15-26. [CrossRef]

- Monto AS, Fukuda K. Lessons From Influenza Pandemics of the Last 100 Years. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020;70(5):951-957.

- Barberis I, Myles P, Ault SK, Bragazzi NL, Martini M. History and evolution of influenza control through vaccination: from the first monovalent vaccine to universal vaccines. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene. 2016;57(3):E115-e120.

- Yang T. Baloxavir Marboxil: The First Cap-Dependent Endonuclease Inhibitor for the Treatment of Influenza. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2019;53(7):754-759. [CrossRef]

- Koel BF, Mögling R, Chutinimitkul S, et al. Identification of Amino Acid Substitutions Supporting Antigenic Change of Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Viruses. J Virol. 2015;89(7):3763-3775. [CrossRef]

- Moscona A. Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;353(13):1363-1373.

- Kashiwagi S, Watanabe A, Ikematsu H, et al. Laninamivir octanoate for post-exposure prophylaxis of influenza in household contacts: a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. Journal of infection and chemotherapy : official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2013;19(4):740-749. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Furuta Y, Fukuda Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of T-705 and oseltamivir against influenza virus. Antiviral Chemistry and Chemotherapy. 2003;14(5):235-241.

- Boriskin YS, Leneva IA, Pécheur EI, Polyak SJ. Arbidol: a broad-spectrum antiviral compound that blocks viral fusion. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(10):997-1005. [CrossRef]

- Haviernik J, Štefánik M, Fojtíková M, et al. Arbidol (Umifenovir): A Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Drug That Inhibits Medically Important Arthropod-Borne Flaviviruses. Viruses. 2018;10(4). [CrossRef]

- Deryabin PG, Garaev TM, Finogenova MP, Odnovorov AI. [Assessment of the antiviral activity of 2HCl*H-His-Rim compound compared to the anti-influenza drug Arbidol for influenza caused by A/duck/Novosibirsk/56/05 (H5N1) (Influenza A virus, Alphainfluenzavirus, Orthomyxoviridae).]. Voprosy virusologii. 2019;64(6):268-273.

- Blaising J, Polyak SJ, Pécheur E-I. Arbidol as a broad-spectrum antiviral: An update. Antiviral research. 2014;107:84-94. [CrossRef]

- Brooks MJ, Burtseva EI, Ellery PJ, et al. Antiviral activity of arbidol, a broad-spectrum drug for use against respiratory viruses, varies according to test conditions. J Med Virol. 2012;84(1):170-181.

- Fediakina I, Leneva I, Iamnikova S, Livov D, Glushkov R, Shuster A. Sensitivity of influenza A/H5 viruses isolated from wild birds on the territory of Russia to arbidol in the cultured MDCK cells. Voprosy virusologii. 2005;50(6):32-35.

- Fediakina I, MIu S, Deriabin P, et al. Susceptibility of pandemic influenza virus A 2009 H1N1 and highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A H5N1 to antiinfluenza agents in cell culture. Antibiotiki i Khimioterapiia= Antibiotics and Chemoterapy [sic]. 2011;56(3-4):3-9. [CrossRef]

- Leneva I, Shuster A. Antiviral etiotropic chemicals: efficacy against influenza A viruses A subtype H5N1. Voprosy virusologii. 2006;51(5):4-7.

- Shi L, Xiong H, He J, et al. Antiviral activity of arbidol against influenza A virus, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, coxsackie virus and adenovirus in vitro and in vivo. Archives of virology. 2007;152(8):1447-1455.

- Ahmed AA, Abouzid M. Arbidol targeting influenza virus A Hemagglutinin; A comparative study. Biophysical chemistry. 2021;277:106663. [CrossRef]

- Kadam RU, Wilson IA. Structural basis of influenza virus fusion inhibition by the antiviral drug Arbidol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114(2):206-214. [CrossRef]

- Leneva IA, Russell RJ, Boriskin YS, Hay AJ. Characteristics of arbidol-resistant mutants of influenza virus: implications for the mechanism of anti-influenza action of arbidol. Antiviral research. 2009;81(2):132-140.

- Proskurnina EV, Izmailov DY, Sozarukova MM, Zhuravleva TA, Leneva IA, Poromov AA. Antioxidant Potential of Antiviral Drug Umifenovir. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;25(7).

- Burtseva E, Shevchenko E, Leneva I, et al. Rimantadine and arbidol sensitivity of influenza viruses that caused epidemic morbidity rise in Russia in the 2004-2005 season. Voprosy virusologii. 2007;52(2):24-29.

- Romanovskaia A, Durymanov A, Sharshov K, et al. Investigation of susceptibility of influenza viruses A (H1N1), the cause of infection in humans in April-May 2009, to antivirals in MDCK cell culture. Antibiotiki i Khimioterapiia= Antibiotics and Chemoterapy [sic]. 2009;54(5-6):41-47.

- Leneva I, Fediakina I, MIu E, et al. Study of the antiviral activity of Russian anti-influenza agents in cell culture and animal models. Voprosy virusologii. 2010;55(3):19-27.

- Leneva IA, Falynskova IN, Leonova EI, et al. [Umifenovir (Arbidol) efficacy in experimental mixed viral and bacterial pneumonia of mice]. Antibiotiki i khimioterapiia = Antibiotics and chemoterapy [sic]. 2014;59 9-10:17-24.

- Leneva IA, Falynskova IN, Makhmudova NR, Poromov AA, Yatsyshina SB, Maleev VV. Umifenovir susceptibility monitoring and characterization of influenza viruses isolated during ARBITR clinical study. J Med Virol. 2019;91(4):588-597.

- Leneva IA, Burtseva E, Kirillova ES, Kolobukhina LV, Prilipov A, Zaplatnikov AL. Assessment of a risk for development of umifenovir resistance in epidemic strains of influenza A and B viruses in clinical settings. Infektsionnye Bolezni. 2019;17:58-66.

- Leneva I, Fediakina I, Gus' kova T, Glushkov R. Sensitivity of various influenza virus strains to arbidol. Influence of arbidol combination with different antiviral drugs on reproduction of influenza virus A. Terapevticheskii arkhiv. 2005;77(8):84-88.

- Pshenichnaya NY, Bulgakova VA, Lvov NI, et al. Clinical efficacy of umifenovir in influenza and ARVI (study ARBITR). Terapevticheskii arkhiv. 2019;91(3):56-63.

- Pshenichnaya N, Bulgakova V, Selkova E, et al. Umifenovir in treatment of influenza and acute respiratory viral infections in outpatient care. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019;79:103.

- Liu Q, Xiong HR, Lu L, et al. Antiviral and anti-inflammatory activity of arbidol hydrochloride in influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2013;34(8):1075-1083.

- Wang Y, Ding Y, Yang C, et al. Inhibition of the infectivity and inflammatory response of influenza virus by Arbidol hydrochloride in vitro and in vivo (mice and ferret). Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2017;91:393-401. [CrossRef]

- Wang MZ, Cai BQ, Li LY, et al. [Efficacy and safety of arbidol in treatment of naturally acquired influenza]. Zhongguo yi xue ke xue yuan xue bao Acta Academiae Medicinae Sinicae. 2004;26(3):289-293.

- Sriwilaijaroen N, Vavricka CJ, Kiyota H, Suzuki Y. Influenza A Virus Neuraminidase Inhibitors. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ). 2022;2556:321-353.

- Su HC, Feng IJ, Tang HJ, Shih MF, Hua YM. Comparative effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in patients with influenza: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of infection and chemotherapy : official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2022;28(2):158-169. [CrossRef]

- McClellan K, Perry CM. Oseltamivir. Drugs. 2001;61(2):263-283.

- Davies BE. Pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir: an oral antiviral for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza in diverse populations. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2010;65 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):ii5-ii10.

- Annex I. Summary of product characteristics. Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products The European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) Stocrin London: The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. 1999.

- Elliott M. Zanamivir: from drug design to the clinic. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356(1416):1885-1893. [CrossRef]

- Scott LJ. Peramivir: A Review in Uncomplicated Influenza. Drugs. 2018;78(13):1363-1370. [CrossRef]

- Saisho Y, Ishibashi T, Fukuyama H, Fukase H, Shimada J. Pharmacokinetics and safety of intravenous peramivir, neuraminidase inhibitor of influenza virus, in healthy Japanese subjects. Antiviral Therapy. 2017;22(4):313-323. [CrossRef]

- Jefferson T, Jones MA, Doshi P, et al. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in adults and children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;2014(4):Cd008965.

- Wiemken TL, Furmanek SP, Carrico RM, et al. Effectiveness of oseltamivir treatment on clinical failure in hospitalized patients with lower respiratory tract infection. BMC infectious diseases. 2021;21(1):1106.

- Ebell MH, Call M, Shinholser J. Effectiveness of oseltamivir in adults: a meta-analysis of published and unpublished clinical trials. Family practice. 2013;30(2):125-133.

- Heneghan CJ, Onakpoya I, Thompson M, Spencer EA, Jones M, Jefferson T. Zanamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2014;348:g2547.

- Hata A, Akashi-Ueda R, Takamatsu K, Matsumura T. Safety and efficacy of peramivir for influenza treatment. Drug design, development and therapy. 2014;8:2017-2038.

- McLaughlin MM, Skoglund EW, Ison MG. Peramivir: an intravenous neuraminidase inhibitor. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2015;16(12):1889-1900. [CrossRef]

- Liu JW, Lin SH, Wang LC, Chiu HY, Lee JA. Comparison of Antiviral Agents for Seasonal Influenza Outcomes in Healthy Adults and Children: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA network open. 2021;4(8):e2119151.

- Nguyen HT, Fry AM, Gubareva LV. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza viruses and laboratory testing methods. Antivir Ther. 2012;17(1 Pt B):159-173.

- Hurt AC, Chotpitayasunondh T, Cox NJ, et al. Antiviral resistance during the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic: public health, laboratory, and clinical perspectives. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2012;12(3):240-248. [CrossRef]

- Pinilla LT, Holder BP, Abed Y, Boivin G, Beauchemin CA. The H275Y neuraminidase mutation of the pandemic A/H1N1 influenza virus lengthens the eclipse phase and reduces viral output of infected cells, potentially compromising fitness in ferrets. J Virol. 2012;86(19):10651-10660.

- Lampejo T. Influenza and antiviral resistance: an overview. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2020;39(7):1201-1208.

- Lee N, Hurt AC. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza: a clinical perspective. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2018;31(6):520-526.

- Chong Y, Matsumoto S, Kang D, Ikematsu H. Consecutive influenza surveillance of neuraminidase mutations and neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in Japan. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2019;13(2):115-122.

- Thorlund K, Awad T, Boivin G, Thabane L. Systematic review of influenza resistance to the neuraminidase inhibitors. BMC infectious diseases. 2011;11:134.

- Jefferson T, Demicheli V, Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti D. Amantadine and rimantadine for influenza A in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006;2006(2):Cd001169.

- Thomaston JL, Samways ML, Konstantinidi A, et al. Rimantadine Binds to and Inhibits the Influenza A M2 Proton Channel without Enantiomeric Specificity. Biochemistry. 2021.

- Pielak RM, Chou JJ. Influenza M2 proton channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(2):522-529.

- Ison MG, Hayden FG. Antiviral Agents Against Respiratory Viruses. Infectious Diseases. 2017:1318 - 1326.e1312.

- Geevarghese B, Simoes EA. Antibodies for prevention and treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infections in children. Antiviral therapy. 2012;17(1 Pt B):201-211.

- Bresee JS, Fiore AE, Fry A, Gubareva LV, Shay DK, Uyeki TM. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). 2011.

- Hayden F, Aoki F. Amantadine, rimantadine, and related agents. Antimicrobial Chemotherapy Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins. 1999:1344-1365.

- Hayden F, Minocha A, Spyker D, Hoffman H. Comparative single-dose pharmacokinetics of amantadine hydrochloride and rimantadine hydrochloride in young and elderly adults. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1985;28(2):216-221.

- Wintermeyer SM, Nahata MC. Rimantadine: a clinical perspective. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 1995;29(3):299-310.

- Mondal D. Rimantadine☆. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences: Elsevier; 2016.

- Bright RA, Medina M-j, Xu X, et al. Incidence of adamantane resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses isolated worldwide from 1994 to 2005: a cause for concern. The Lancet. 2005;366(9492):1175-1181.

- Barr IG, Hurt AC, Iannello P, Tomasov C, Deed N, Komadina N. Increased adamantane resistance in influenza A (H3) viruses in Australia and neighbouring countries in 2005. Antiviral research. 2007;73(2):112-117.

- Update: influenza activity - United States, 2009-10 season. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2010;59(29):901-908.

- Dong G, Peng C, Luo J, et al. Adamantane-resistant influenza a viruses in the world (1902–2013): frequency and distribution of M2 gene mutations. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0119115.

- Shiraishi K, Mitamura K, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Goto H, Sugaya N, Kawaoka Y. High frequency of resistant viruses harboring different mutations in amantadine-treated children with influenza. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2003;188(1):57-61.

- Dawood F, Jain S, Finelli L, et al. Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(25):2605-2615.

- Deyde VM, Xu X, Bright RA, et al. Surveillance of resistance to adamantanes among influenza A (H3N2) and A (H1N1) viruses isolated worldwide. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007;196(2):249-257.

- Ilyushina NA, Govorkova EA, Russell CJ, Hoffmann E, Webster RG. Contribution of H7 haemagglutinin to amantadine resistance and infectivity of influenza virus. Journal of General Virology. 2007;88(4):1266-1274.

- Carnaccini S, Perez DR. H9 influenza viruses: an emerging challenge. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2020;10(6):a038588.

- Portsmouth S, Kawaguchi KS, Arai M, Tsuchiya K, Uehara T. Cap-dependent Endonuclease Inhibitor S-033188 for the Treatment of Influenza: Results from a Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo- and Active-Controlled Study in Otherwise Healthy Adolescents and Adults with Seasonal Influenza. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2017;4:S734 - S734.

- Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Hirotsu N, et al. Baloxavir Marboxil for Uncomplicated Influenza in Adults and Adolescents. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;379(10):913-923.

- Ison MG, Portsmouth S, Yoshida Y, et al. Early treatment with baloxavir marboxil in high-risk adolescent and adult outpatients with uncomplicated influenza (CAPSTONE-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2020;20(10):1204-1214.

- Hashimoto T, Baba K, Inoue K, et al. Comprehensive assessment of amino acid substitutions in the trimeric RNA polymerase complex of influenza A virus detected in clinical trials of baloxavir marboxil. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 2021;15(3):389-395.

- Checkmahomed L, Padey B, Pizzorno A, et al. In Vitro Combinations of Baloxavir Acid and Other Inhibitors against Seasonal Influenza A Viruses. Viruses. 2020;12(10).

- Dias A, Bouvier D, Crépin T, et al. The cap-snatching endonuclease of influenza virus polymerase resides in the PA subunit. Nature. 2009;458(7240):914-918.

- XofluzaTM [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Pharmaceu-ticals, Inc; 2014.

- Omoto S, Speranzini V, Hashimoto T, et al. Characterization of influenza virus variants induced by treatment with the endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1-15.

- Uehara T, Hayden FG, Kawaguchi K, et al. Treatment-emergent influenza variant viruses with reduced baloxavir susceptibility: impact on clinical and virologic outcomes in uncomplicated influenza. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2020;221(3):346-355.

- Govorkova EA, Takashita E, Daniels RS, et al. Global update on the susceptibilities of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors and the cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir, 2018-2020. Antiviral research. 2022;200:105281.

- Gubareva LV, Fry AM. Baloxavir and Treatment-Emergent Resistance: Public Health Insights and Next Steps. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019;221(3):337-339.

- Fukao K, Noshi T, Yamamoto A, et al. Combination treatment with the cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil and a neuraminidase inhibitor in a mouse model of influenza A virus infection. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2018;74(3):654-662.

- Kawaguchi N, Koshimichi H, Ishibashi T, Wajima T. Evaluation of Drug-Drug Interaction Potential between Baloxavir Marboxil and Oseltamivir in Healthy Subjects. Clinical drug investigation. 2018;38(11):1053-1060.

- Tobar Vega P, Caldeira E, Abad H, Saad P, Lachance E. Oseltamivir and baloxavir: Dual treatment for rapidly developing ARDS on a patient with renal disease. IDCases. 2020;21:e00819.

- Kumar D, Ison MG, Mira J-P, et al. Combining baloxavir marboxil with standard-of-care neuraminidase inhibitor in patients hospitalised with severe influenza (FLAGSTONE): a randomised, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled, superiority trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2022;22(5):718-730.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).