Introduction

One of the greatest sustainability challenges is feeding a further two billion people without incurring an overwhelming environmental impact. Seafood will continue to play a key role in solving this challenge as it is generally more environmentally efficient than other sources of animal-based proteins (Hilborn et al. 2018; Poore and Nemecek 2018; Halpern et al. 2022). Globally, fish consumption has increased, at a rate of 3.1% each year from 1961 to 2017 (FAO 2020). Increased demand for fish has caused fisheries catch and wild-caught fish populations to stagnate or decline across the globe (Pauly et al. 2002), which has serious consequences for marine biodiversity, ecosystem function, and human nutrition and welfare (Worm et al. 2006; Myers et al. 2007; Marschke and Vandergeest 2016). Improving the sustainability of seafood benefits the ocean, and associated ecosystems, as well as the people it supports.

There are multiple ways of defining sustainable seafood, but environmental sustainability is typically the focus of wild caught and aquaculture produced seafood (Bogard et al. 2019). For example, fisheries are considered to be sustainable when the stocks of target species are well managed, destructive fishing practices and bycatch levels are minimised, and the system is deemed as viable into the future (Hilborn et al. 2015). Similarly, aquaculture systems are considered to be sustainable when there is efficient production with minimal pollution and waste generated, a high production to feed ratio, and minimal impacts on the surrounding environment (Valenti et al. 2018; Ahmed et al. 2019; Cánovas-Molina and García-Frapolli 2021).

The demand from consumers to have access to sustainable seafood products is growing as sustainability awareness and education grows, and consumers are sometimes willing to pay more for these sustainable products (Witkin et al. 2015; McClenachan et al. 2016; Lawley et al. 2019). This has spurred an increase in prevalence of ecolabels and seafood certification schemes such as the Marine Stewardship Council for wild capture fisheries, and the Aquaculture Stewardship Council for farmed seafood products (Council 2018; Council 2020). In addition, sustainable seafood guides have been developed to help consumers determine the sustainability of the seafood available within specific countries; for example, The Good Fish Guide assesses the sustainability of common seafood products found in Australia.

Sustainability guides and certification schemes, however, will only help people choose sustainable seafood products if they are readily available to consumers. Further, sustainability guides can be difficult to use as they require information that is not always available, such as the species and where/how it was caught or produced. In Australia, for example, seafood labelling laws do not mandate that this information is provided to consumers, especially in the case of cooked seafood. Here, we aim to determine how accessible sustainable seafood is to consumers in Australia, with a focus on South East Queensland. Given the environmental and socioeconomic importance of fishing and seafood in this area, sustainability must be a key component of the seafood seascape now and looking forward (Steven et al. 2020). By determining the accessibility of sustainable seafood in this region, we show where key gaps and opportunities exist to make real improvements in seafood consumption behaviours in developed markets such as coastal Australian cities.

Methods

Study region

Australians consume an average of 13.7kg of seafood per person in 2017-18 (Steven

et al. 2020). Although Australians still eat more beef, chicken, and pork than seafood, there is cultural significance around fishing and seafood especially near the coasts (Steven

et al. 2020). Australia has numerous policies managing fishery operations, such as the

Fisheries Management Act 1991, which support sustainability and conservation (Government 2020). The seafood Australia produces is not necessarily consumed in Australia given that, globally, seafood is one of the most traded commodities. Australia exports approximately 19% of the seafood it produces and imports around 70% of its seafood from overseas (Steven

et al. 2020). Thus, the seafood that is consumed in Australia may not be sustainable, despite Australia’s relatively rigorous marine conservation and sustainability policies (Hilborn

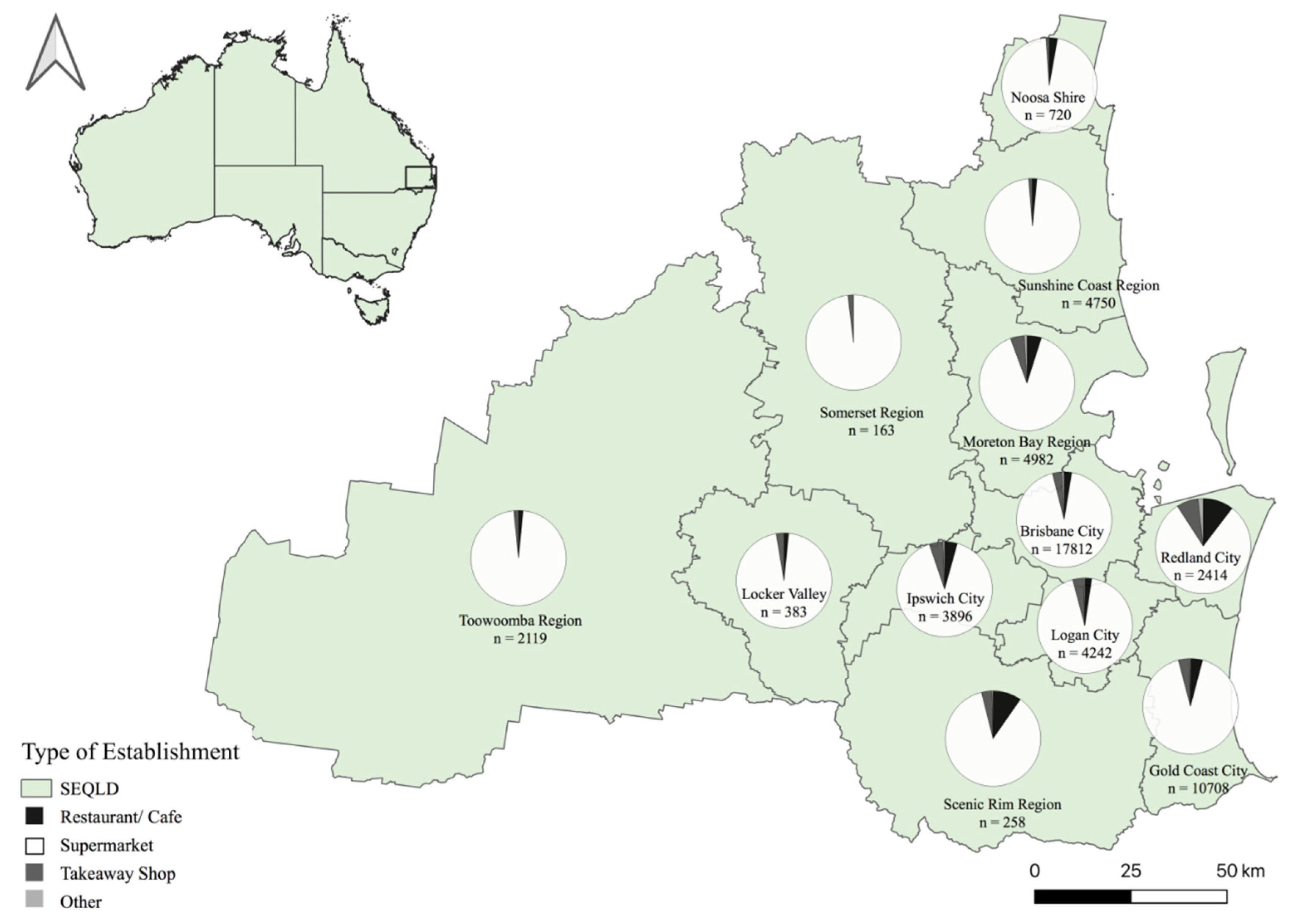

et al. 2020). We focus on environmental sustainability, in line with available information. We conducted this study in South East Queensland, Australia, a region with a population of 3,366,880 (ABS 2017) across 12 local government areas (“areas”) (

Figure 1). We chose this region as it was accessible to us during extensive COVID lockdowns that prohibited interstate travel and because of the socio-economic importance of fishing and seafood. South East Queensland has a large and active recreational fishing sector, which has grown since the COVID-19 pandemic (Major 2021) and even exceeds commercial catch volumes and value for some species and areas (Brown 2016).

Data collection

We designed a survey to assess the sustainability of fresh, frozen, cooked and processed seafood products based on the Australian Marine Conservation Society (AMCS) guide, Good Fish (AMCS 2019a). The guide was chosen as it is freely available to the public via an online website and phone application and is specifically designed for use by consumers to assess the sustainability of seafood products they are likely to encounter in Australia. The guide categorises the sustainability of common seafood products into three categories based on its species, origin and catch method (AMCS 2019a): “Better Choice” (most sustainable categorisation), “Eat Less” (some sustainability concerns), and “Say No” (least sustainable categorisation). The survey (Appendix 1) included questions targeting the information required for consumers to determine the sustainability of a seafood product (fresh, cooked, frozen or canned) within the Good Fish guide, focusing on species, origin and catch method information.

Surveys were conducted across 12 areas at any establishment that sells seafood to the general population, including restaurants, supermarkets, and takeaway venues. We determined a sample size for each area (95% confidence, 5% margin of error) of 62-348 establishments, depending on population size and how many potential establishments in each area sell seafood products (Appendix 2). To determine the initial sample size, we used publicly available food licence data provided for four areas (Brisbane City, Gold Coast City, Ipswich City and Logan City) (Coucil 2021a; Coucil 2021b; Council 2021a; Council 2021b), with the potential number of seafood establishments excluding schools, hospitals, nursing homes and childcare centres, as well as establishments that definitely do not sell seafood products such as ice cream parlours and some fast food chains (Morland et al. 2002). We extrapolated the number of potential establishments for the eight areas that did not provide this data by calculating the number of establishments per 1000 people in a known area with a similar population size and multiplying by the population of the unknown area.

When surveying, we further refined the number by counting the number of establishments that sold seafood products versus did not (not counting establishments already removed), which we used to estimate the proportion of seafood establishments in each area that was surveyed in-person. This was completed for 191 establishments across South East Queensland areas. We multiplied these proportions by the potential number of seafood establishments for each area, to determine a more accurate sample size (Appendix 2). The data collected was then extrapolated for chain establishments based in multiple locations that confirmed they had the same products and supplier for each chain (e.g., McDonalds) (

Table 1). For major supermarkets that had limited variation across their stores (e.g., Coles and Woolworths), a typical store for each chain was created based on the surveyed stores and then extrapolated for the number of stores across the survey area (

Table 1). The most variation for the supermarkets was found in the fresh/raw seafood section of the stores, with all other packaged seafood products having a very similar range across all surveyed stores. Results were analysed with and without extrapolation to include restaurant and grocery store chains.

Based on numerous studies that have successfully incorporated citizen scientist data, we engaged volunteers to help conduct surveys (Sullivan

et al. 2014; McKinley

et al. 2017). To do this, we designed a simple survey that was easy to access by volunteers in Google Forms. We also created a website (

https://sustainableseafoodsurvey.wordpress.com/) that provided detailed instructions on how to fill in the survey to ensure consistency among entries. We focused on the recruitment of citizen scientists connected to local universities. Recruitment included presenting to over 80 students and staff at the University of Queensland, emailing local environmental or marine science university groups (e.g., University of Queensland’s Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science), posting on social media, and hanging posters around the University of Queensland. We conducted all surveys in-person, using a door-to-door method, to every open establishment at the time in an area. At each establishment, the surveyor first observed the available information (e.g., reading the menu or food product label), then asked an employee one or two follow-up questions if the information was not observable. If more enquiries were required, the answer was marked as “unknown,” since the information was not easily available. Enquiries were not made for pre-packaged products (e.g., canned and frozen products) as employees were unlikely to be able to provide any additional information.

Analysis

We assessed each survey entry using the AMCS Good Fish Guide, to determine the sustainability category of the seafood product: Better Choice, Eat Less and Say No (AMCS 2019a). The seafood products not listed in the guide were given the category “NA”. Some seafood products did not have enough information to categorise. However, in some cases, we were able to determine the missing information so that we could assess their sustainability. For example, farmed Australian products for a particular species have the same sustainability categorisation for all locations around Australia; thus if we knew that a barramundi product was farmed in Australia, we could assume it was a Better Choice, without specific origin information being provided. When species-level information (e.g., only the species group was provided) was not provided and there were multiple different species options to choose from in the Good Fish Guide, we deemed the product to not have specific enough information to determine its sustainability and categorised it as unknown. For example, 14 prawn listings are included in the guide covering all three sustainability categorisations, but products containing prawns are often sold without all the information to determine the exact listing product. Similarly, origin information was considered unknown if it was not given or if it was not specific enough to use the guide to determine the sustainability categorisation. For example, the Good Fish Guide categorises barramundi caught in Queensland fisheries as Say No, however, barramundi caught in the Northern Territory or Western Australian fisheries are categorised as Eat Less (AMCS 2019a).Therefore barramundi labelled only as Australian barramundi would not be able to be classified.

In addition, we assessed the entries for wild caught Australian species using the stock status sustainability categories of the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC). Only Australian wild caught entries were assessed in this analysis because the FRDC does not include any sustainability information on farmed or imported species. The FRDC works in partnership (including receiving funding) with the Australian government to ensure sustainability of fisheries and marine ecosystems (FRDC 2021). Although the FRDC is aimed at a broader audience (including industry, researchers and policy makers), not just consumers, we included this analysis to compare sustainability information for seafood species, as it is another source of data available to Australian consumers which may provide conflicting information for some species (FRDC 2021). Additionally, the FRDC focuses on Australian stocks, whereas other sustainability guides such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch, are specific to America and are missing a lot of local Australian information and therefore are not as useful to Australian consumers.

Results

We surveyed 1,049 different establishments covering 8,498 products across South East Queensland (

Table 1) (analyses of in-person survey results are in Appendix 4). The lead author conducted the vast majority (estimated 96%) of the surveys, with anonymous citizens contributing the remaining 4%. The extrapolated data used in our analyses, including chain restaurants and supermarkets, covered 2,110 different establishments and 52,447 products (

Table 1). We found that 18,709 (36%) products contained enough information to assess sustainability using the AMCS Good Fish Guide. A limited number of products were categorised as a Better Choice (4.9%, n= 2,587), with the majority of products being categorised as NA (seafood products not listed in the guide) (48%, n= 25,315), followed by Say No (27%, n= 13,991), not enough information (could not be categorised) (16%, n= 8,421) and Eat Less (4.1%, n= 2,129). There were 187 species (n= 25,317 products) which were not listed in the guide (or the guide did not have a listing for the information, such as a specific origin), and were therefore categorised as NA. Skipjack tuna (n=2,826) and Atlantic salmon (n=2,559) from imported origins were the most common species categorised as NA.

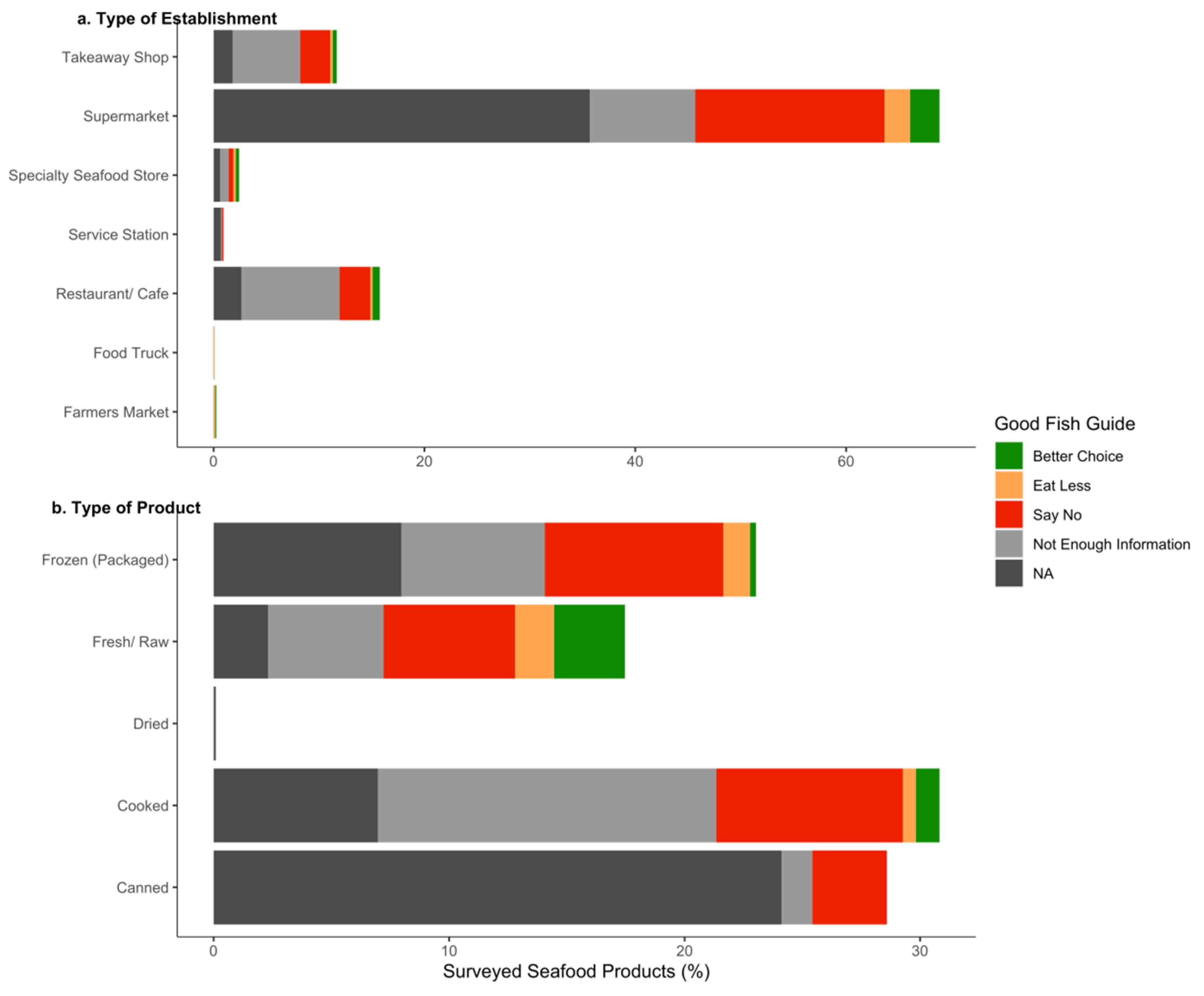

The greatest number of seafood product surveys were conducted in supermarkets (92%, n= 48,508), where 5% (n=2,447) of seafood products were categorised as a Better Choice option (

Figure 2a). Farmers markets had the highest proportion of Better Choice options (32%, n=7), followed by specialty seafood stores (13%, n=27), supermarkets (5%, n= 2,447) and restaurants (4%, n=72) (

Figure 2a). Frozen packaged seafood items were the most common product type for seafood products (33%, n= 17,541), however, only 0.9% (n=162) were categorised as a Better Choice (

Figure 2b). The most common sustainable, Better Choice seafood products were in their fresh/raw form (3.8%, n= 1,983) (

Figure 2b). The majority of products were imported (69%, n=36,425), with only 20% (n=10,444) of seafood products from Australia (0.4%, n=222 products were a mix of origins and 10%, n=5,356 were of unknown origin).

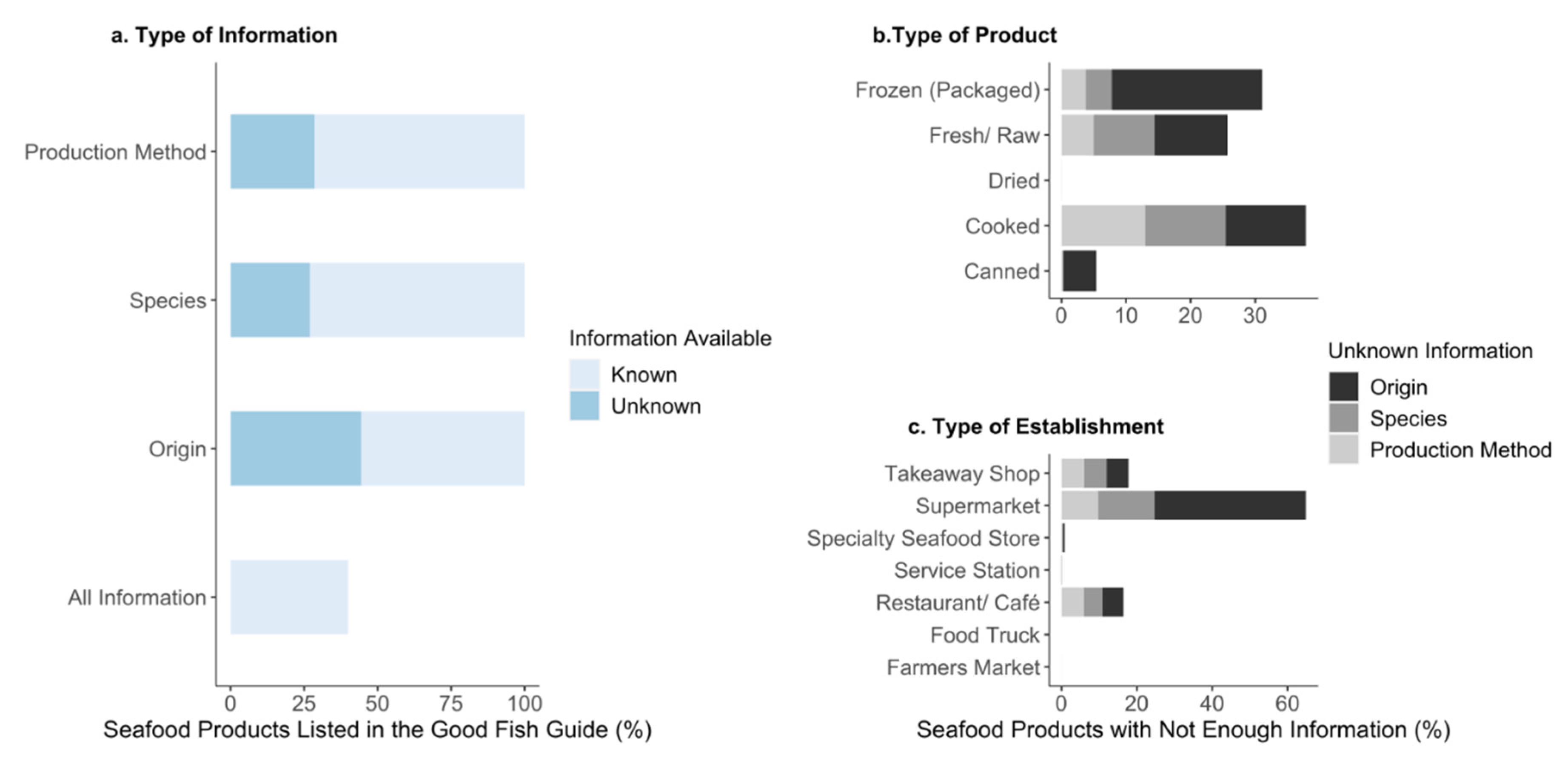

We found that across the surveyed products listed in the Good Fish Guide, only 40% (n= 10,843) had all three types of information required to determine their sustainability category. Adequate origin information was the most commonly lacking element (44%, n= 12,040) (

Figure 3a). Of the 8,421 products that did not have enough information to be categorised for their Good Fish Guide sustainability category, 93% (n= 7,832) were completely missing origin information or did not have detailed enough information to allow the sustainability category of the product to be determined (

Figure 3b and c). We found that 26% (n= 7,309) of surveyed seafood products listed in the Good Fish Guide did not have clear species names (

Figure 3a). Cooked products were most commonly lacking information (n= 2,120), whereas canned (n= 761) products usually provided enough information to categorise them (

Figure 3b). Restaurants/cafes and takeaway shops were more likely to lack the required information to assess sustainability than supermarkets and had a much higher proportion of products unable to be categorised (53%, n= 1908) compared to supermarkets (13%, n= 6430) (

Figure 3c). Often staff when queried about missing information, they were unable to provide the information (54%, n= 3324, Appendix 5). With the inclusion of this information to consumers, an additional 2,338 surveyed seafood products may have been considered to be a Better Choice, sustainable option, increasing the potential availability of sustainable seafood products to 9.4%. However, without this additional information, consumers looking to use the Good Fish Guide to purchase sustainable seafood products are, often unnecessarily, further limited in their choices.

We found some discrepancies between the Good Fish Guide sustainability categories and the FRDC stock status reports (

Table 2). There were inconsistent categorisations for 31 of the species (n= 874 products). For example, 11 stocks were considered to be sustainable by the FRDC and unsustainable (Say No) by the Good Fish Guide (AMCS 2019a). If consumers use the FRDC statuses as their guide when purchasing sustainable seafood products, 4.4% (n= 2,288) of seafood products surveyed would be considered sustainable (compared to 4.9% with Good Fish Guide alone), or 7.9% (n= 4,115) of products were sustainable if considering the best listing from either guide.

We summarised the most common products in each sustainability category and found that the most common Better Choice options surveyed were farmed Australian seafood (

Table 3). The exception is farmed Australian Atlantic salmon, which was the most common farmed species and is categorised as Say No. Blue grenadier was one of the most common species available to consumers (n= 1,554), however, the sustainability categorisation is determined by the origin of the fish, with the less sustainable option from New Zealand being more prevalent than the more sustainable option from Australia (

Table 3). There were eight species listed in the Good Fish Guide which we did not encounter during the survey (e.g., Australian salmon and luderick), however, as there were numerous unknown species (categorised as not enough information), the species may still be present in the surveyed products.

Discussion

We found that it is difficult for consumers to access sustainable seafood products in South East Queensland. There are many detrimental impacts from producing unsustainable seafood products for both fisheries and aquaculture systems, including overfishing and bycatch, habitat destruction, and pollution. Overfishing of target and non-target (bycatch) species is a fundamental challenge for fisheries in Australia and globally, and combatting overfishing is a core tenet of sustainable seafood initiatives (Roberson et al. 2020). Habitat destruction from fisheries occurs primarily through damage to the benthic structure from certain fishing methods (e.g. trawling), but fishing can also create disturbances that negatively impact non-target organisms (e.g. resuspending sediments), or reduce overall benthic diversity (Collie et al. 2000; O'Neill and Ivanovic 2016). Unsustainable aquaculture systems can also cause habitat destruction of marine, coastal, and terrestrial ecosystems through habitat clearing, depending where the farm is based (Ahmed et al. 2019; Cánovas-Molina and García-Frapolli 2021). Pollution is a serious issue for aquaculture, especially eutrophication and sedimentation of the surrounding environment from effluent which can lead to anoxic conditions and harmful algal blooms (Tovar et al. 2000; Ahmed et al. 2019). The major source of fisheries-based pollution is discarded (“ghost”) fishing gear, which is a direct threat to marine biodiversity and results in measurable economic losses for fisheries (Hardesty et al. 2015; Eric Gilman 2016). If better options are accessible, consumers have the power to shift demand towards seafood products with fewer deleterious environmental impacts, which can drive industry to produce more sustainable products.

There are some limitations and potential biases to our results. For example, when asking a server at a particular establishment questions about the product, the answer may differ depending who answered the question. Thus, the results may differ if the survey was conducted at the same places at different times, which mimics the problem consumers’ face when purchasing seafood products. Some severs were more willing to search for the information, or were able to get a manger, owner or chef who was able to answer the questions. Others had no idea and were unwilling to investigate, or no one with the information was available at the time. There may have been some social desirability bias with some of the answers as some servers may have given a dishonest answer (mostly in regards to origin information) depending on what they thought the person surveying wanted to hear, in order to give them a higher likelihood of a sale. For example, claiming the seafood was of Australian origin as opposed to imported as it may sound higher quality. Another limitation was that not all areas were surveyed in-person and relied only on extrapolated data, meaning that some of the variation in establishments such as restaurants and cafes was not represented in this study for those areas. However, the majority of in-person surveys were completed in the most populated areas with the highest number of seafood vendors. Additionally, the accuracy of the labels was not tested, and numerous recent studies have shown through genetic testing that many products are mislabelled (Kroetz et al. 2020). Further, the availability of seafood may vary depending on the season, especially for fresh seafood products, which influences our results.

The main legislation in Australia governing labelling laws is the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (ANZFSC). Currently, the ANZFSC only requires country of origin labelling for packaged seafood products, such as canned and frozen seafood (Transport 2014; Government 2016). This explains why there are a high number of products with inadequate information for cooked products and restaurant/cafes and takeaway shops in comparison to supermarkets. Removing the labelling exemption for cooked food in places including restaurants and cafes would greatly improve the transparency of seafood labels and allow the sustainability of more seafood products to be determined. This would make Australia a world leader in this regard, as cooked seafood products in most countries, including the European Union, Canada and America, do not mandate country of origin labelling for cooked seafood products served in the hospitality industry (Service 2009; Parliament 2013; Canada 2019). An Australian senate inquiry into this issue was conducted in 2014, which determined that the exemption for cooked seafood in the food service industry should be removed (Transport 2014). This further supports changing the country of origin requirements for seafood products in hospitality establishments across Australia. However, when the federal labelling laws were updated in 2016, the origin exemption for the hospitality industry was not removed (Government 2016). The Northern Territory already requires hospitality establishments to label if seafood is imported and demonstrates that concerns about high additional costs to implement country of origin laws for seafood are unfounded (Transport 2014). Queensland has recently passed a Bill (Food (Labelling of Seafood) Amendment Act 2021), due to come into effect in July 2023, which requires the hospitality industry in Queensland to label seafood items as Australian or imported on their menus, in line with the Northern Territory.(Government 2021). This will help improve the transparency of where seafood products are from and thus, make it easier for consumers to determine the sustainability of seafood. Transparency in seafood productions chains could help improve the responsibility and accountability of producers to use more sustainable practices (Bailey et al. 2016; Lewis and Boyle 2017), and therefore reduce their overall environmental impact on the ocean.

The number of canned and frozen products missing information, which are typically packaged and are predominately found in supermarkets, is still quite large considering the Australian labelling laws. This is likely due to a generic name such as “fish” being an acceptable species label (Transport 2014; Government 2016), with 4,249 products being labelled as “fish” and 490 of those products provided fish as the most detailed species information, after examining the label or asking a server. In addition, there were 41 products labelled as flake (shark), another common generic name, with 28 products not providing any extra details even after enquiry. Furthermore, lax species labelling laws are facilitated by the lack of an official compulsory naming standard for seafood species. The seafood industry (funded by the FRDC) created the only available guide, the Australian Fish Names Standard, but it is voluntary (Transport 2014; FRDC 2021). Therefore, adopting a mandatory labelling system will improve consistency and allow consumers to know exactly what species they are consuming. The framework for this to occur is already in place with the Australian Fish Names Standard, which covers over 4,000 species, including both imported and domestically produced seafood (FRDC 2021).

We found almost half of products were missing origin information, despite current labelling laws, which was likely due to two factors. Firstly, in many cases, more detailed origin information (e.g., at Australian state level instead of just “Australia”) was required to successfully categorise a species using the Good Fish Guide. Secondly, many products (mostly packaged) that listed a country of origin, only labelled the country of processing (satisfying the labelling requirements) but did not list where the seafood in the product was caught or farmed (Government 2016). It is common for seafood products to be transported to numerous destinations before reaching a consumer’s plate; for instance the animal may be caught or farmed in one country then sent to one or more additional countries for processing, before ultimately being sent to another country (or sometimes back to where it was caught) for final sale and consumption (FAO 2020). Therefore, adding more specific origin of seafood labelling for processed seafood products (e.g., the fishery or farm where the species was caught), will also allow the consumer to have a better understanding of where the product has come from as well as where it was processed, giving greater transparency of the supply chain for the seafood product. For farmed seafood, the country of the farm and the species is sufficient detail for consumers to understand its geographic origin. Additionally, including the specific farm name on products would also be beneficial for consumers as individual farms may have differing sustainability standards. However, wild caught seafood requires more detailed origin information as there are often multiple stocks of a species within a country. Furthermore, the Good Fish Guide recommends that labels also include which gear is used and the name of company to increase the accountability of the company and encourage them to ensure a high standard of environmental management, which will allow consumers to pick products with the best sustainability practices (AMCS 2019b). This will bring Australia in line with countries such as America and the European Union that already enforce specific country of origin laws for packaged seafood products, including detailing where the seafood was caught or farmed as well as listing the catch method (Service 2009; Parliament 2013). These regulations by America and the European Union have been put in place to reduce the amount of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) seafood products entering their markets (Bailey et al. 2016; Lewis and Boyle 2017).

The Good Fish Guide has a limited number of products classified as a Better Choice for consumers (AMCS 2019a). The guide currently lists 45 better choice options out of 130 options, potentially making the choice limited for consumers and harder to find amongst the large range of species that are consumed (AMCS 2019a). There were a large portion of seafood species that were not included in the guide, especially imported species. Furthermore, the missing Australian species were often common in major supermarkets, such as sweetlip and blacktip shark, which is concerning as supermarkets were the most common place for consumers to access seafood products. As Australia imports 70% of seafood products (Steven et al. 2020), the addition of commonly available species is necessary to improve the effectiveness of the guide to consumers. The inconsistency in information between the Good Fish Guide and the FRDC also has the potential to confuse consumers as different species have different sustainability categorisations when it comes to wild caught Australian seafood. When used individually, both sources of sustainability information had low (less than 5%) accessibility of sustainable products. Combining the availability of sustainable products increases the availability to 7.9%. However, this is still quite poor given the large number of seafood products available to consumers. Furthermore, it is unrealistic for people to refer to two different sources of sustainability information when purchasing seafood.

The conflicting results when comparing the FRDC to the Good Fish Guide can be explained by the differences in their assessment criteria. The Good Fish Guide for wild caught species uses a holistic view of the ecosystem, focusing not only on the stock status of the target species, but also on environmental impacts, bycatch, and management, when assessing the categorisation of a species fishery (AMCS 2019a). In contrast, the FRDC only considers a species on an individual level, and assesses how that specific stock is performing in terms of biomass and fishing pressure to determine sustainability. However, in the future they are planning to consider broader ecosystem, social and economic impacts in their reports (FRDC 2021). These differences in assessment and sustainability information highlight the inconsistencies in the definitions of sustainable fisheries and seafood (Hilborn et al. 2015), and could cause confusion for consumers.

These results highlight how challenging it is for consumers to access sustainable seafood in South East Queensland despite the existence of sustainable options, including products that cost the same or less than “Say No” or “Eat Less” options.. The effort involved in obtaining the necessary information may discourage them from buying seafood products altogether. When information is not presented to the consumer in enough detail and staff cannot provide the missing information, guides such as the Good Fish Guide and America’s Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch are unable to be successfully used (Kemmerly and Macfarlane 2009; Roheim 2009). However, when there is sufficient information, guides are an excellent resource for consumers to utilise and not only aid in increasing knowledge and awareness of sustainability issues in the seafood industry, but also help to change consumer purchasing habits (Kemmerly and Macfarlane 2009). Thus, our recommendations broadly apply to countries with seafood guides that are looking to improve the availability of sustainable of seafood to their consumers. As a general rule for Australian seafood consumers, we recommend choosing local Australian products as they are usually the most sustainable option due to regulated legislation, such as the Fisheries Management Act 1991, that ensure generally well-managed fisheries and aquaculture systems compared to many exporting countries. Farmed prawns, mussels, oysters and barramundi are the most common sustainable seafood products available.

Overall, there needs to be a higher standard of seafood production to increase the accessibility of sustainable seafood products to consumers and give them a greater variety of choices. Stricter laws for Australia’s seafood imports in terms of sustainability and traceability would further increase the relative availability of sustainable seafood options for consumers. Improving the sustainability of trade and food production in Australia would not only benefit people looking to make sustainable choices, but also help the Australian government meet the United Nations Sustainable Development goals, specifically goals 12 and 14 (Responsible Consumption and Production and Life Below Water). Ultimately, efforts to improve the production component of sustainable seafood will be wasted if complementary actions are not taken to close the supply loop and communicate that information to consumers.

Funding

This research was funded by an ARC Future Fellowship (200100314) grant awarded to Carissa Klein.

Acknowledgements

A University of Queensland ethics exemption was granted for this study, 17/02/2021 – 29/10/2021. Project number: 2021/HE000078. We would like to the citizen scientists who volunteered their time to collect surveys for the study, especially the field trip participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Sustainable Seafood Survey

A single enquiry may be required to the person serving you e.g. could you please tell me what species this is and where it was caught?

*Required

- 5.

-

Type of Product*

Mark only one.

Fresh/ Raw

Frozen

Cooked

Canned

- 6.

-

Product label*

Includes the label on the menu, packaging or signage

- 7.

-

Which species*

Please be as detailed as possible (this can include scientific name or common name(s)). If no specie information is available please specify the type of seafood e.g. fish, prawns etc.

- 8.

-

Place of origin (where caught or farmed)*

This could be a country, region or ocean, please be as detailed as possible

- 9.

-

State – if Australian place of origin

Mark only one.

QLD

NSW

VIC

SA

NT

WA

TAS

Unknown

- 10.

-

Catch Method*

Mark only one.

Farmed

Wild Caught

Unknown

- 11.

Any other catch information (e.g. line caught, trap etc.)

- 12.

-

Sustainability Certification*

Tick all that apply.

Marine Stewardship Council (MSC)

Responsibly sourced (Woolworths)

Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC)

Responsibly sourced (Coles)

Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP)

No certification

Other:

- 13.

Cost $*

- 14.

-

Cost units*

Mark only one.

Per 100g

Per Kg

Per serve

Other:

- 15.

-

Did you ask for any of this information?*

Tick all that apply.

Species

Origin

Catch method

No

Other:

Appendix 2

Table A1.

Detailed sample size and surveys completed for establishments and seafood products in each of the 12 local government regions in southeast Queensland.

Table A1.

Detailed sample size and surveys completed for establishments and seafood products in each of the 12 local government regions in southeast Queensland.

| Region |

No. Potential Seafood Establishments |

Population (2016 Census) |

Proportion of Seafood Establishments (After In-Person Surveying) |

Sample Size, 5% Margin of Error, 95% Confidence |

No. Surveyed Establishments In-Person |

No. Surveys Collected In-Person |

No. Extrapolated Surveyed Establishments |

No. Extrapolated Surveys |

| Brisbane City |

6159 |

1,131,155 |

0.60 |

348 |

276 |

1831 |

654 |

17812 |

| Gold Coast City |

4446 |

555,721 |

0.67 |

341 |

249 |

2497 |

458 |

10708 |

| Ipswich City |

576 |

193,733 |

0.76 |

205 |

152 |

932 |

216 |

3896 |

| Lockyer Valley* |

115 |

38,609 |

0 |

89 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

383 |

| Logan City |

970 |

303,386 |

0.61 |

233 |

72 |

1165 |

165 |

4242 |

| Moreton Bay Region* |

1360 |

425,302 |

0.66 |

269 |

148 |

740 |

263 |

4982 |

| Noosa Shire* |

155 |

52,149 |

0.89 |

102 |

10 |

26 |

19 |

720 |

| Redland City* |

437 |

147,010 |

0.68 |

169 |

105 |

1098 |

140 |

2414 |

| Scenic Rim Region* |

119 |

40,072 |

0.46 |

49 |

18 |

45 |

24 |

258 |

| Somerset Region* |

73 |

24,597 |

0 |

62 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

163 |

| Sunshine Coast Region* |

941 |

294,367 |

0.48 |

208 |

20 |

163 |

106 |

4750 |

| Toowoomba City* |

478 |

160,779 |

0 |

214 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

2119 |

| Total |

15829 |

3,366,880 |

- |

2289 |

1050 |

8497 |

2110 |

52447 |

Appendix 3

Table A2.

Dataset headings, which were not all included in this analysis.

Table A2.

Dataset headings, which were not all included in this analysis.

| Establishment |

Product |

Sustainability Categorisation |

| Date |

Type of Product |

AMCS Guide Categorisation |

| Establishment |

Product Label |

AMCS Guide Categorisation (Worst Choice) |

| Suburb |

Type of Seafood (e.g. fish, prawn) |

Good Fish Guide Recognised Establishment |

| Postcode |

Which Species |

Great Australian Seafood Finder Establishment |

| Region (Local Government Area) |

Latin name if given |

EPBC Act List of Threatened Species |

| |

Australian/Imported |

FRDC Stock Status |

| |

Place of Origin |

IUCN Red List Status |

| |

State (if Australian Place of Origin) |

Presence of MSC Certification |

| |

Catch Method |

Canned Tuna Guide |

| |

Other Catch Method Information |

WWF At Risk Species to Avoid |

| |

Presence/ Absence of a Sustainability Certification |

Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch |

| |

Researched Sustainability Certifications |

Fish Choice |

| |

Price (AUD) |

Good Fish Guide UK |

| |

Price Units |

Ocean Wise Seafood Program |

| |

Did you Ask for any of this Information? |

|

| |

Additional Comments |

|

Appendix 4

Figure A1.

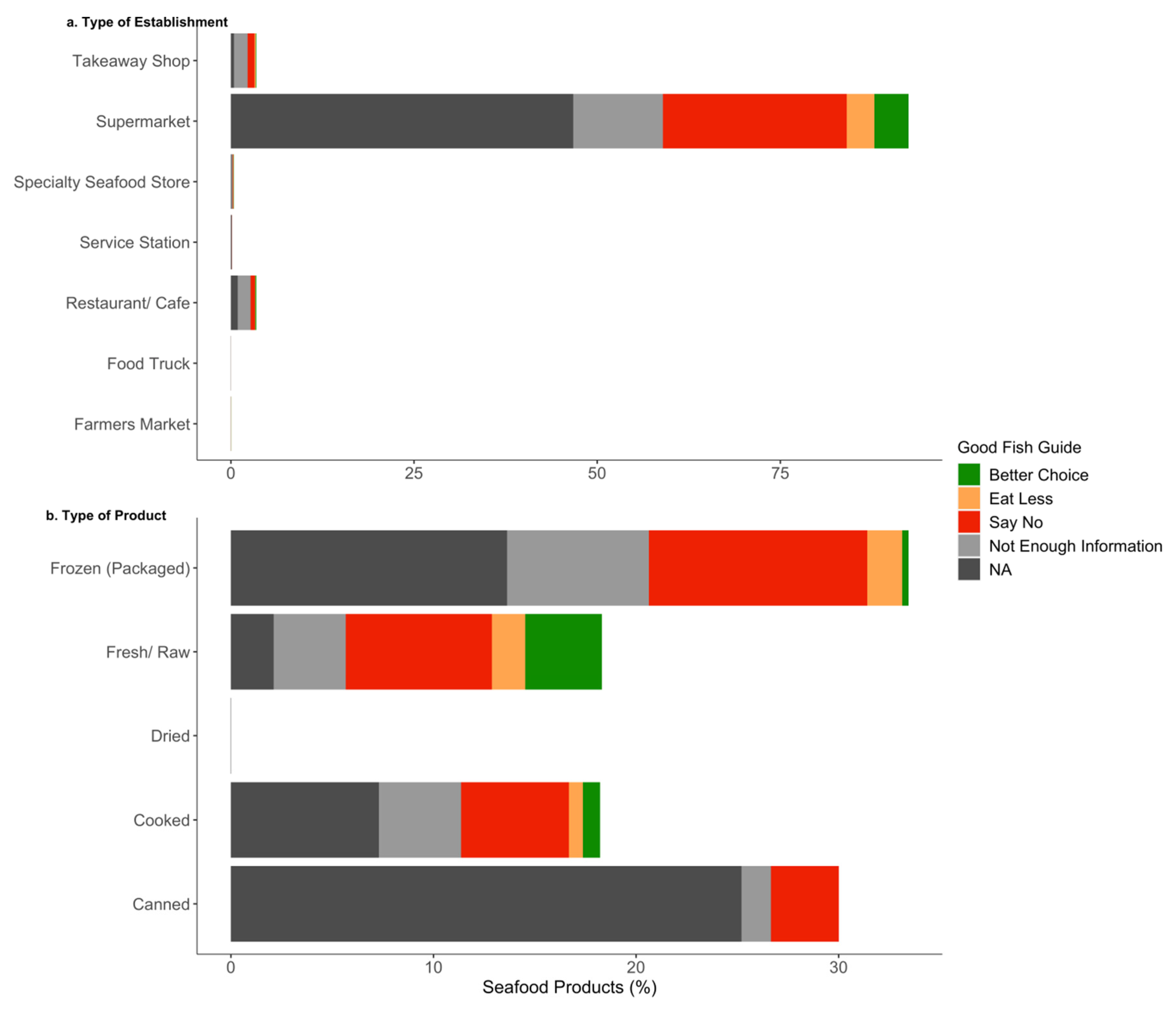

The sustainability of in-person surveyed seafood products (n= 8,497) were assessed using Australia’s Good Fish Guide (AMCS 2019a) across a range of establishments (a) and for a variety of products (b). The guide categorises seafood products into three categories: ‘Better Choice’, ‘Eat Less’ and ‘Say No’. Some of the seafood products surveyed could not be categorised due to a lack of information or were not in the guide (NA).

Figure A1.

The sustainability of in-person surveyed seafood products (n= 8,497) were assessed using Australia’s Good Fish Guide (AMCS 2019a) across a range of establishments (a) and for a variety of products (b). The guide categorises seafood products into three categories: ‘Better Choice’, ‘Eat Less’ and ‘Say No’. Some of the seafood products surveyed could not be categorised due to a lack of information or were not in the guide (NA).

Table A3.

Summary of the sustainability of in-person surveyed seafood products for types of establishments and products, assessed against the Good Fish Guide (AMCS 2019a).

Table A3.

Summary of the sustainability of in-person surveyed seafood products for types of establishments and products, assessed against the Good Fish Guide (AMCS 2019a).

| Establishments |

| Type |

Sustainability Categorisation (No. Products) |

Total |

| Better Choice |

Eat Less |

Say No |

Not Enough Information |

NA |

| Farmers Market |

7 |

12 |

- |

1 |

2 |

22 |

| Food Truck |

2 |

2 |

2 |

- |

1 |

7 |

| Restaurant/ Café |

56 |

21 |

247 |

792 |

223 |

1339 |

| Service Station |

- |

- |

11 |

10 |

58 |

79 |

| Specialty Seafood Store |

27 |

21 |

36 |

70 |

52 |

206 |

| Supermarket |

237 |

206 |

1524 |

852 |

3032 |

5851 |

| Takeaway Shop |

32 |

23 |

239 |

546 |

153 |

993 |

| Products |

| Canned |

- |

- |

268 |

112 |

2049 |

2429 |

| Cooked |

85 |

47 |

673 |

1222 |

592 |

2619 |

| Dried |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

7 |

8 |

| Fresh/ Raw |

255 |

141 |

474 |

418 |

196 |

1484 |

| Frozen (Packaged) |

21 |

97 |

644 |

518 |

677 |

1957 |

Appendix 5

Table A4.

Information provided to consumers when specifically enquiring about a seafood product (across n= 4099, with some products having multiple enquiries made about them), showing whether servers were able to provide the knowledge to a consumer.

Table A4.

Information provided to consumers when specifically enquiring about a seafood product (across n= 4099, with some products having multiple enquiries made about them), showing whether servers were able to provide the knowledge to a consumer.

| a. Summary |

| |

Question |

Total |

| Species |

Origin |

Catch Method |

| Known |

Unknown |

Known |

Unknown |

Known |

Unknown |

Known |

Unknown |

| No. Products |

814 |

1285 |

1519 |

1775 |

502 |

264 |

2835 |

3324 |

| Percentage (%) |

38.78 |

61.22 |

46.11 |

53.89 |

65.54 |

34.46 |

46.03 |

53.97 |

| b. Type of Establishment |

| Type of Establishment |

Question |

Total |

| Species |

Origin |

Catch Method |

| Known |

Unknown |

Known |

Unknown |

Known |

Unknown |

Known |

Unknown |

| Farmers Market |

No. Products |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Percentage (%) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Food Truck |

No. Products |

2 |

- |

3 |

- |

6 |

- |

11 |

- |

| Percentage (%) |

100 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

| Restaurant/ Café |

No. Products |

42 |

69 |

609 |

486 |

147 |

137 |

798 |

692 |

| Percentage (%) |

37.84 |

62.16 |

55.62 |

44.38 |

51.76 |

48.24 |

53.56 |

46.44 |

| Service Station |

No. Products |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| Percentage (%) |

0 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

- |

- |

0 |

100 |

| Specialty Seafood Store |

No. Products |

3 |

3 |

6 |

- |

130 |

8 |

139 |

11 |

| Percentage (%) |

50.00 |

50.00 |

100 |

0 |

94.20 |

5.80 |

92.67 |

7.33 |

| Supermarket |

No. Products |

252 |

154 |

30 |

6 |

33 |

15 |

315 |

175 |

| Percentage (%) |

62.07 |

37.93 |

83.33 |

16.67 |

68.75 |

31.25 |

64.29 |

35.71 |

| Takeaway Shop |

No. Products |

200 |

768 |

763 |

792 |

182 |

102 |

1145 |

1662 |

| Percentage (%) |

20.66 |

79.34 |

49.07 |

50.93 |

64.08 |

35.92 |

40.79 |

59.21 |

References

- ABS (2017) 2016 census quickstats. (Ed. Editor) (Australian Bureau of Statistics: Australia).

- Ahmed N, Thompson S, and Glaser M (2019) Global aquaculture productivity, environmental sustainability, and climate change adaptability. Environmental Management 63(2), 159-172. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- AMCS (2019a) Australian marine conservation society. Goodfish australia’s sustainable seafood guide. (Ed. Editor) (Australian Marine Conservation Society).

- AMCS (2019b) Australian seafood labelling. (Ed. Editor) Vol. 2022, (Australian Marine Conservation Society).

- Bailey M, Bush SR, Miller A, and Kochen M (2016) The role of traceability in transforming seafood governance in the global south. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 18, 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Bogard JR, Farmery AK, Baird DL, Hendrie GA, and Zhou SJ (2019) Linking production and consumption: The role for fish and seafood in a healthy and sustainable australian diet. Nutrients 11(8), 22. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- Brown CJ (2016) Social, economic and environmental effects of closing commercial fisheries to enhance recreational fishing. Marine Policy 73, 204-209. [CrossRef]

- Canada Go (2019) Safe food for canadians regulations (sor/2018-108). (Ed. Editor): Canada).

- Cánovas-Molina A, and García-Frapolli E (2021) Socio-ecological impacts of industrial aquaculture and ways forward to sustainability. Marine and Freshwater Research 72(8), 1101-1109. [CrossRef]

- Collie JS, Hall SJ, Kaiser MJ, and Poiner IR (2000) A quantitative analysis of fishing impacts on shelf-sea benthos. Journal of Animal Ecology 69(5), 785-798.

- Coucil GCC (2021a) Eat safe gold coast. (Ed. Editor) (Gold Coast City Council: Gold Coast, Australia).

- Coucil IC (2021b) Eat safe ipswich city. (Ed. Editor) (Ipswich City Council).

- Council AS (2020) Monitoring and evaluation report.Report, London, UK.

- Council BC (2021a) Food safety permits. (Ed. Editor) (Brisbane City Council: Brisbane, Australia).

- Council LC (2021b) Eat safe logan. (Ed. Editor) (Logan City Council: Logan, Australia).

- Council MS (2018) Msc fisheries standard. (Ed. Editor) (Marine Stewardship Council: London, UK).

- Eric Gilman FC, Petri Suuronen, Blaise Kuemlangan (2016) Abandoned, lost and discarded gillnets and trammel nets.Report, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- FAO (2020) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in action..Report, Rome.

- FRDC (2021) Status of australian fish stocks reports full list. (Ed. Editor) (Fisheries Research and Development Corporation: Australia).

- Government A (2016) Australian government. Country of origin food labelling information standard 2016. (Ed. Editor): Canberra). C: Editor).

- Government A (2020) Australian government. Fisheries management act 1991. (Ed. Editor): Canberra).

- Government Q (2021) Food (labelling of seafood) amendment act 2021. (Ed. Editor) (Queensland Government).

- Halpern BS, Frazier M, Verstaen J, Rayner P-E, Clawson G, Blanchard JL, Cottrell RS, Froehlich HE, Gephart JA, Jacobsen NS, Kuempel CD, McIntyre PB, Metian M, Moran D, Nash KL, Többen J, and Williams DR (2022) The environmental footprint of global food production. Nature Sustainability 5(12), 1027-1039.

- Hardesty BD, Good TP, and Wilcox C (2015) Novel methods, new results and science-based solutions to tackle marine debris impacts on wildlife. Ocean & Coastal Management 115, 4-9.

- Hilborn R, Amoroso RO, Anderson CM, Baum JK, Branch TA, Costello C, De Moor CL, Faraj A, Hively D, Jensen OP, Kurota H, Little LR, Mace P, McClanahan T, Melnychuk MC, Minto C, Osio GC, Parma AM, Pons M, Segurado S, Szuwalski CS, Wilson JR, and Ye Y (2020) Effective fisheries management instrumental in improving fish stock status. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(4), 2218-2224.

- Hilborn R, Banobi J, Hall SJ, Pucylowski T, and Walsworth TE (2018) The environmental cost of animal source foods. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16(6), 329-335. [In English].

- Hilborn R, Fulton EA, Green BS, Hartmann K, Tracey SR, and Watson RA (2015) When is a fishery sustainable? Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 72(9), 1433-1441.

- Kemmerly JD, and Macfarlane V (2009) The elements of a consumer-based initiative in contributing to positive environmental change: Monterey bay aquarium's seafood watch program. Zoo Biology 28(5), 398-411. [CrossRef]

- Kroetz K, Luque GM, Gephart JA, Jardine SL, Lee P, Chicojay Moore K, Cole C, Steinkruger A, and Donlan CJ (2020) Consequences of seafood mislabeling for marine populations and fisheries management. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(48), 30318-30323. [CrossRef]

- Lawley M, Craig JF, Dean D, and Birch D (2019) The role of seafood sustainability knowledge in seafood purchase decisions. British Food Journal 121(10), 2337-2350. [In English]

. [CrossRef]

- Lewis SG, and Boyle M (2017) The expanding role of traceability in seafood: Tools and key initiatives. Journal of Food Science 82, A13-A21. [CrossRef]

- Major T (2021) Recreational fishing is booming in queensland, so should fishers pay a licence fee? In 'Australian Broadcasting Corporation Rural'. (Ed. Editor) (Australian Broadcasting Coporation).

- Marschke M, and Vandergeest P (2016) Slavery scandals: Unpacking labour challenges and policy responses within the off-shore fisheries sector. Marine Policy 68, 39-46. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- McClenachan L, Dissanayake STM, and Chen XJ (2016) Fair trade fish: Consumer support for broader seafood sustainability. Fish and Fisheries 17(3), 825-838. [In English].

- McKinley DC, Miller-Rushing AJ, Ballard HL, Bonney R, Brown H, Cook-Patton SC, Evans DM, French RA, Parrish JK, Phillips TB, Ryan SF, Shanley LA, Shirk JL, Stepenuck KF, Weltzin JF, Wiggins A, Boyle OD, Briggs RD, Chapin SF, Hewitt DA, Preuss PW, and Soukup MA (2017) Citizen science can improve conservation science, natural resource management, and environmental protection. Biological Conservation 208, 15-28. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- Morland K, Wing S, Roux AD, and Poole C (2002) Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 22(1), 23-29. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- Myers RA, Baum JK, Shepherd TD, Powers SP, and Peterson CH (2007) Cascading effects of the loss of apex predatory sharks from a coastal ocean. Science 315(5820), 1846-1850. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- O'Neill FG, and Ivanovic A (2016) The physical impact of towed demersal fishing gears on soft sediments. ICES JOURNAL OF MARINE SCIENCE 73, 5-14. [CrossRef]

- Parliament E (2013) Regulation (eu) no 1379/2013 of the european parliament andof the council. On the common organisation ofthe markets in fishery and aquaculture products. (Ed. Editor)).

- Pauly D, Christensen V, Guenette S, Pitcher TJ, Sumaila UR, Walters CJ, Watson R, and Zeller D (2002) Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature 418(6898), 689-695. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- Poore J, and Nemecek T (2018) Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 360(6392), 987-+. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- Roberson LA, Watson RA, and Klein CJ (2020) Over 90 endangered fish and invertebrates are caught in industrial fisheries. Nature Communications 11(1), 8. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- Roheim CA (2009) An evaluation of sustainable seafood guides: Implications for environmental groups and the seafood industry. Marine Resource Economics 24(3), 301-310. [In English].

- Service AM (2009) Agricultural marketing service. Mandatory country of origin labeling of beef, pork, lamb, chicken, goat meat, wild and farm-raised fish and shellfish, perishable agricultural commodities, peanuts, pecans, ginseng, and macadamia nuts. (Ed. Editor) (U.S. Department of Agriculture).

- Steven AH, Mobsby D, and Curtotti R (2020) Australian fisheries and aquaculture statistics 2018.Report, Canberra.

- Sullivan BL, Aycrigg JL, Barry JH, Bonney RE, Bruns N, Cooper CB, Damoulas T, Dhondt AA, Dietterich T, Farnsworth A, Fink D, Fitzpatrick JW, Fredericks T, Gerbracht J, Gomes C, Hochachka WM, Iliff MJ, Lagoze C, La Sorte FA, Merrifield M, Morris W, Phillips TB, Reynolds M, Rodewald AD, Rosenberg KV, Trautmann NM, Wiggins A, Winkler DW, Wong WK, Wood CL, Yu J, and Kelling S (2014) The ebird enterprise: An integrated approach to development and application of citizen science. Biological Conservation 169, 31-40. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- Tovar A, Moreno C, Manuel-Vez MP, and Garcia-Vargas M (2000) Environmental impacts of intensive aquaculture in marine waters. WATER RESEARCH 34(1), 334-342. [CrossRef]

- Transport RaRAa (2014) Rural and regional affairs and transport references committee. Current requirements for labelling of seafood and seafood products. (Ed. Editor): Canberra).

- Valenti WC, Kimpara JM, Preto BD, and Moraes-Valenti P (2018) Indicators of sustainability to assess aquaculture systems. Ecological Indicators 88, 402-413. [In English]. [CrossRef]

- Witkin T, Dissanayake STM, and McClenachan L (2015) Opportunities and barriers for fisheries diversification: Consumer choice in new england. Fisheries Research 168, 56-62. [CrossRef]

- Worm B, Barbier EB, Beaumont N, Duffy JE, Folke C, Halpern BS, Jackson JBC, Lotze HK, Micheli F, Palumbi SR, Sala E, Selkoe KA, Stachowicz JJ, and Watson R (2006) Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science 314(5800), 787-790. [In English]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).