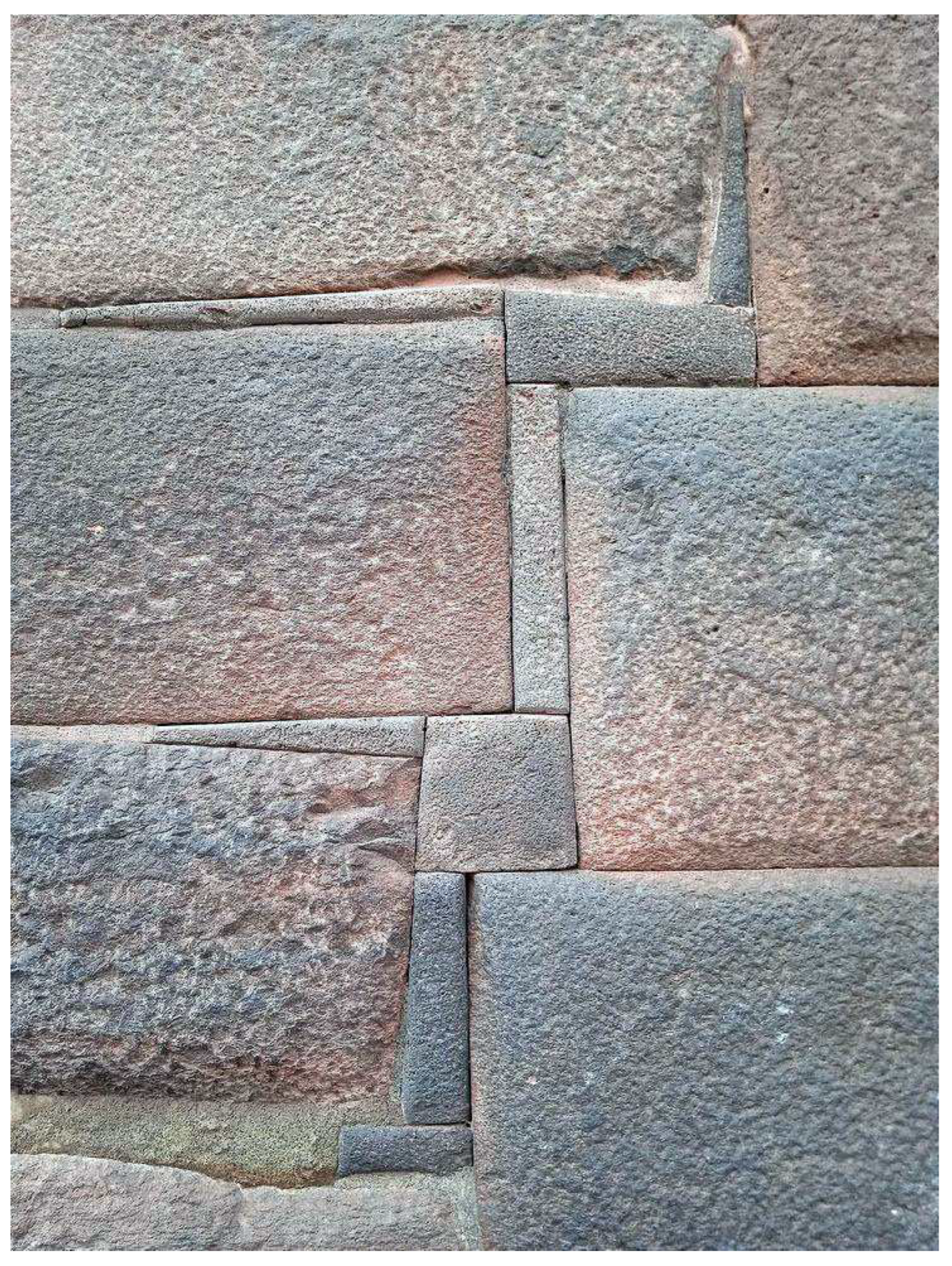

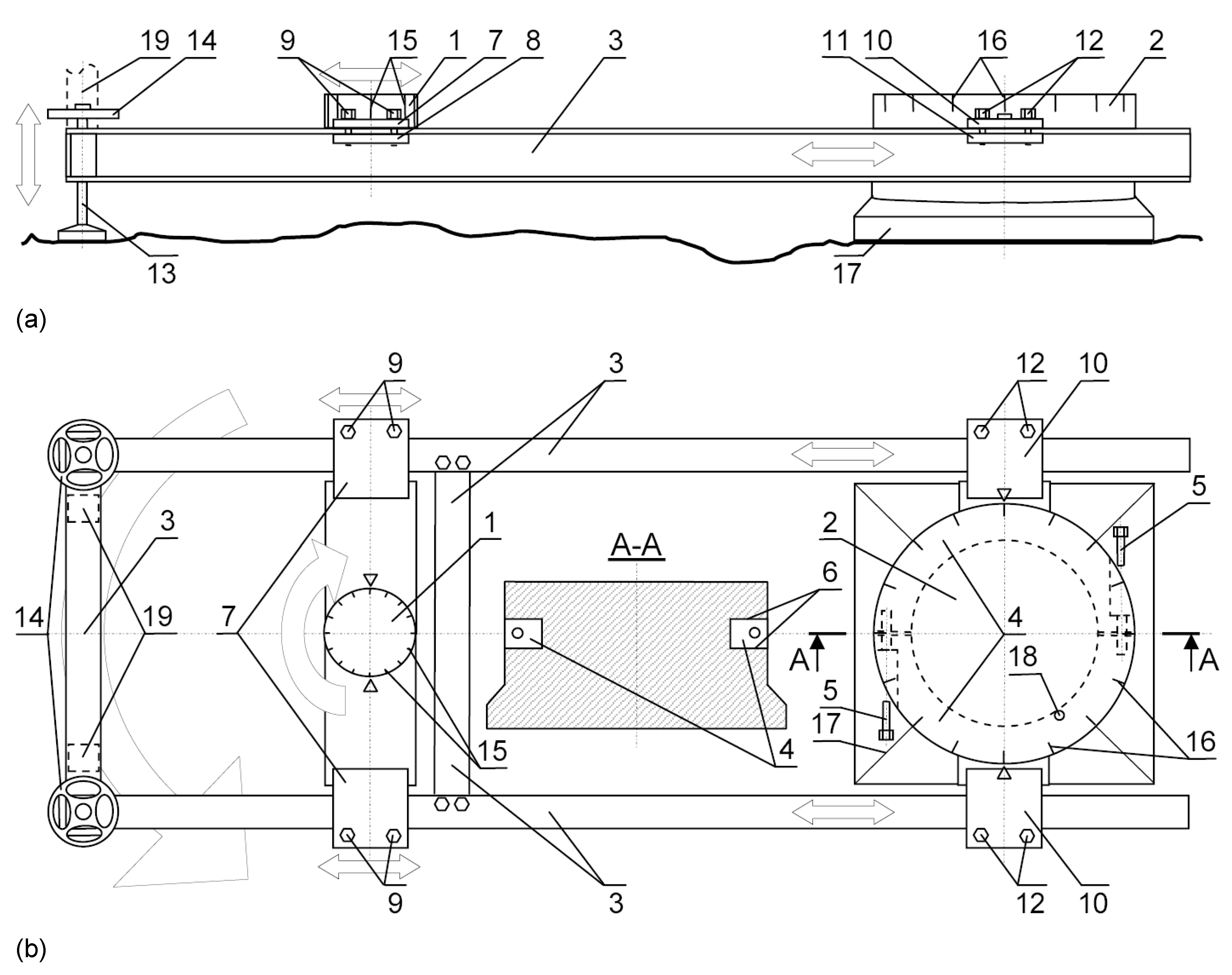

In general, the lateral surface of a stone block is a set of the mentioned conditionally flat surface sections. The conditionally flat sections can adjoin each other forming a sharp boundary, or they can pass into each other quite smoothly as in the reciprocal parts of the L-shaped recesses. The U-shaped recesses are reduced to a pair of counter-located L-shaped recesses. Further, let us describe in more detail the translator and the stone block processing sequence based on its application.

2.11.2. Order of operation with the topography translator

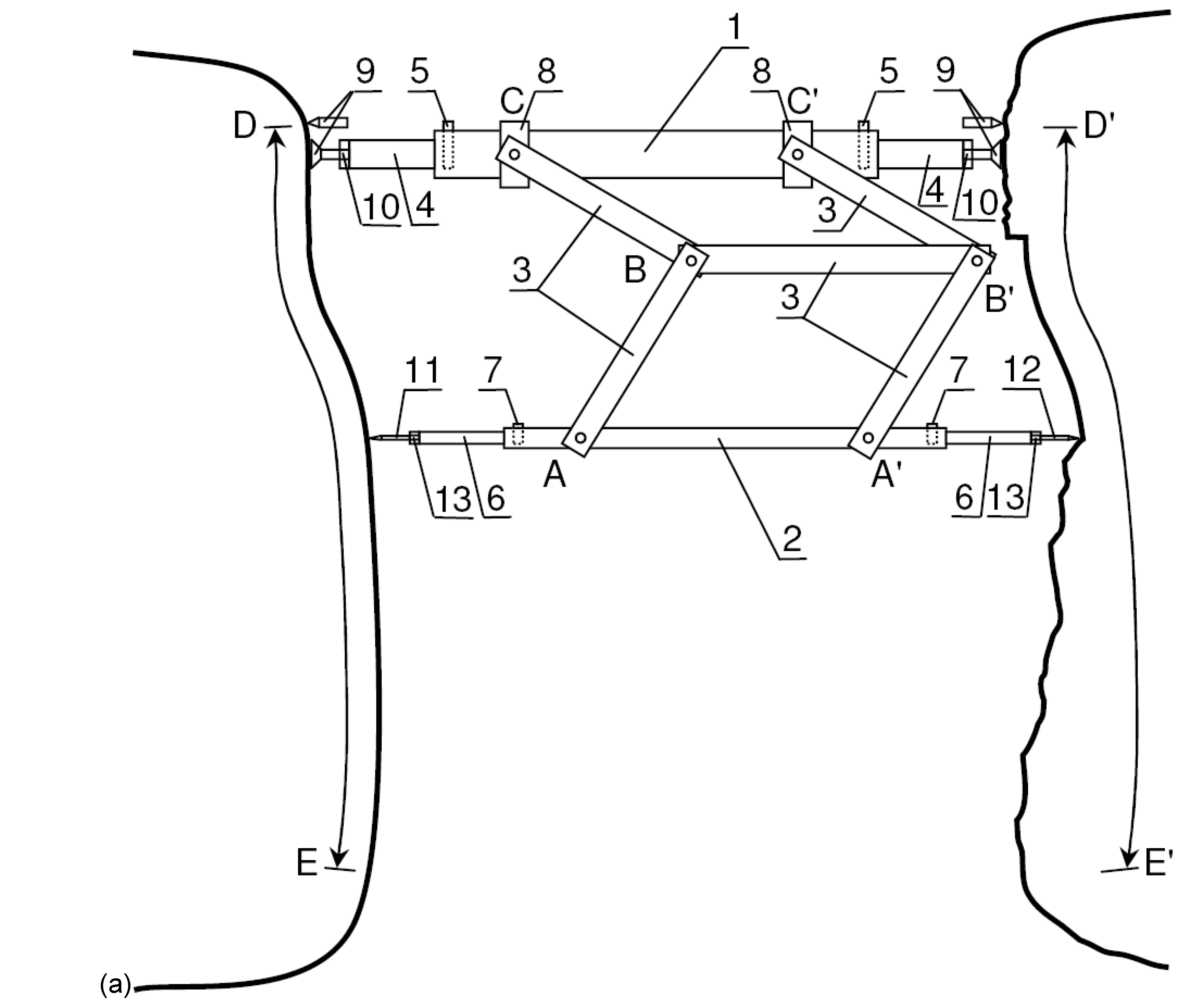

If the carrying rod of the translator is installed near the location of the longest distance between the blocks, then the longest distance is set in the measuring rod in-place, and the topography transfer starts from this location. Generally, the carrying rod can be installed at any location which is convenient for the stonemason. In practice, it is often convenient to install the carrying rod closer to a block edge, and to begin topography transfer (translation) from there.

After installing the carrying rod and setting the necessary length of the measuring rod, the probe tip of the measuring rod is brought into the contact with the pre-treated surface of the first stone block (shown in the figure on the left). As a result, the pointer tip of the measuring rod will show the point on the counter processing surface of the second block (shown in the figure on the right), where the stonemason should chip off material.

If one made the translator pointer sinkable into the retractable section of the measuring rod, spring-loaded, and equipped with a scale and an indicator (these elements are not shown in the figure) then the stonemason will know how much material should be chipped off at this point. The similar pointer device can also be used in the design of the 3D-pantograph. Thus, having information about the amount of material to be removed at each surface point, the stonemason performs the work in fewer chippings significantly improving his productivity.

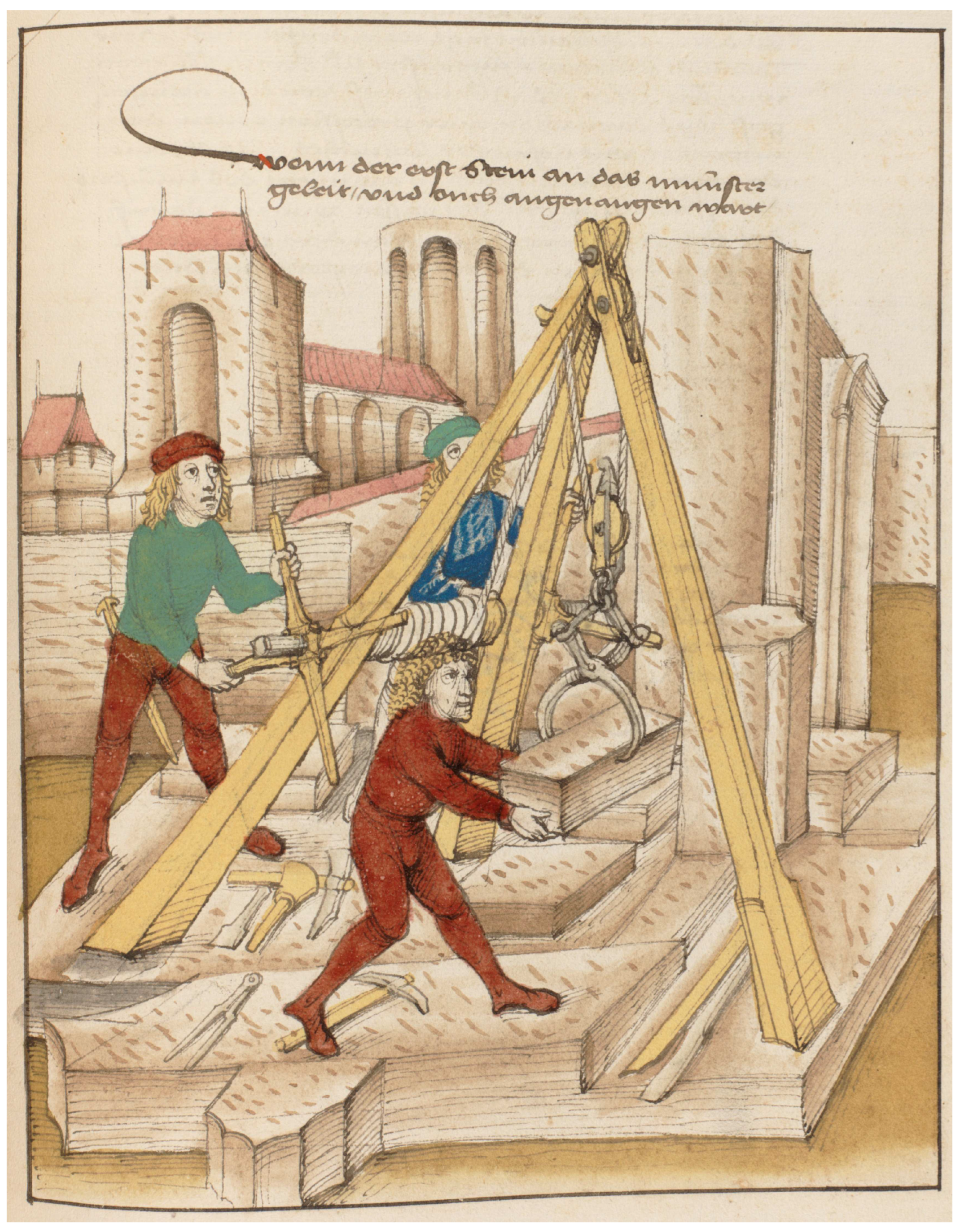

The highest productivity is achieved when two people operate with the translator. One person with the translator pointer shows the location (point) on the stone block under processing and says the thickness of material that should be removed at this point, and the other person using the hammer and chisel removes the specified amount of the material.

The main purpose of the double parallelogram mechanism is to ensure the strict parallelism of the movement of the measuring rod. From the above description, it can be seen that the translator under consideration provides the same result on a separate mating section as the 3D-pantograph adjusted to the scale 1:1.

Translator accuracy is determined by gaps in the hinges and by bending deformations of the structural elements of the mechanism. To ensure structure rigidity, the bars and hinges used in the parallelograms have the appropriate cross-section sizes and stiffeners (not shown in the figure). To increase structure rigidity, besides the mentioned parallelogram mechanisms, additional identical parallelogram mechanisms can be used by attaching them both in parallel and in series (along the rods).

The translator mechanism has a limited movement space, which is a cylinder with 2AB radius (the axis of the cylinder is the carrying rod). Therefore, when operating with large blocks, it is impossible to process the entire mating surface in one installation of the translator. Moreover, due to the finite dimensions of the parallelogram bars, hinges, and rods themselves, the area in the immediate vicinity of the carrying rod installation location and at the spot itself also turns out to be unreachable for processing (see

Figure 5).

Thus, after processing the area of the mating surface reachable by the measuring rod, the position of the measuring rod is fixed at the edge of the processed area like a strut by slightly unscrewing the probe and/or the pointer from the rod (sinkable pointer is blocked by a special pin). If the measuring rod is light enough and the hinges of the double parallelogram are not tight then the measuring rod fixation can be performed by compressing the spring of the sinkable pointer on the still unprocessed nearby area of the stone block. After that, the carrying rod is released and transferred parallel to the fixed-in-space measuring rod at a new location, where it is fixed as a strut again. Finally, the measuring rod is released, and the work continues on a new area of the stone block adjacent to the previous one.

To avoid an upset of the specified length of the measuring rod and a blunting of its probe and pointer when installing the measuring rod as a strut, it is possible, after moving the measuring rod to the edge of the translator's travel range, to simply mark with a paint the point that the probe touches and the corresponding point that the pointer looks at. After that, the carrying rod can be unfixed, moved and installed by supports on the paint-marked points. Note that, having a number of such marks and using the translator as an inspection tool, it is always possible to accurately return the stone blocks to their original position to continue processing, if they were moved for some reasons before. Installation of small wedging stones between the backsides of the stone blocks and the ground provides the necessary position fixation of the blocks in space.

The topography transfer process described above shows that if one can provide the carrying rod with the same pointed tips as the measuring rod has, and make the measuring rod as thick as the carrying one, and also provide the measuring rod with the same cylindrical hinges as the carrying rod has, then we get a modification of the translator of a symmetrical design, where there is no difference between the carrying and measuring rods. Such a translator can be more convenient while moving over a large area stone surface being processed; however, it will have a heavier and less sharp probe-pointer.

The conjugation of two adjacent blocks over one section was described above. The next section will demonstrate how the polygonal masonry as a whole could be created using the proposed translator.

2.11.3. The stone block processing sequence in the polygonal masonry by the translator

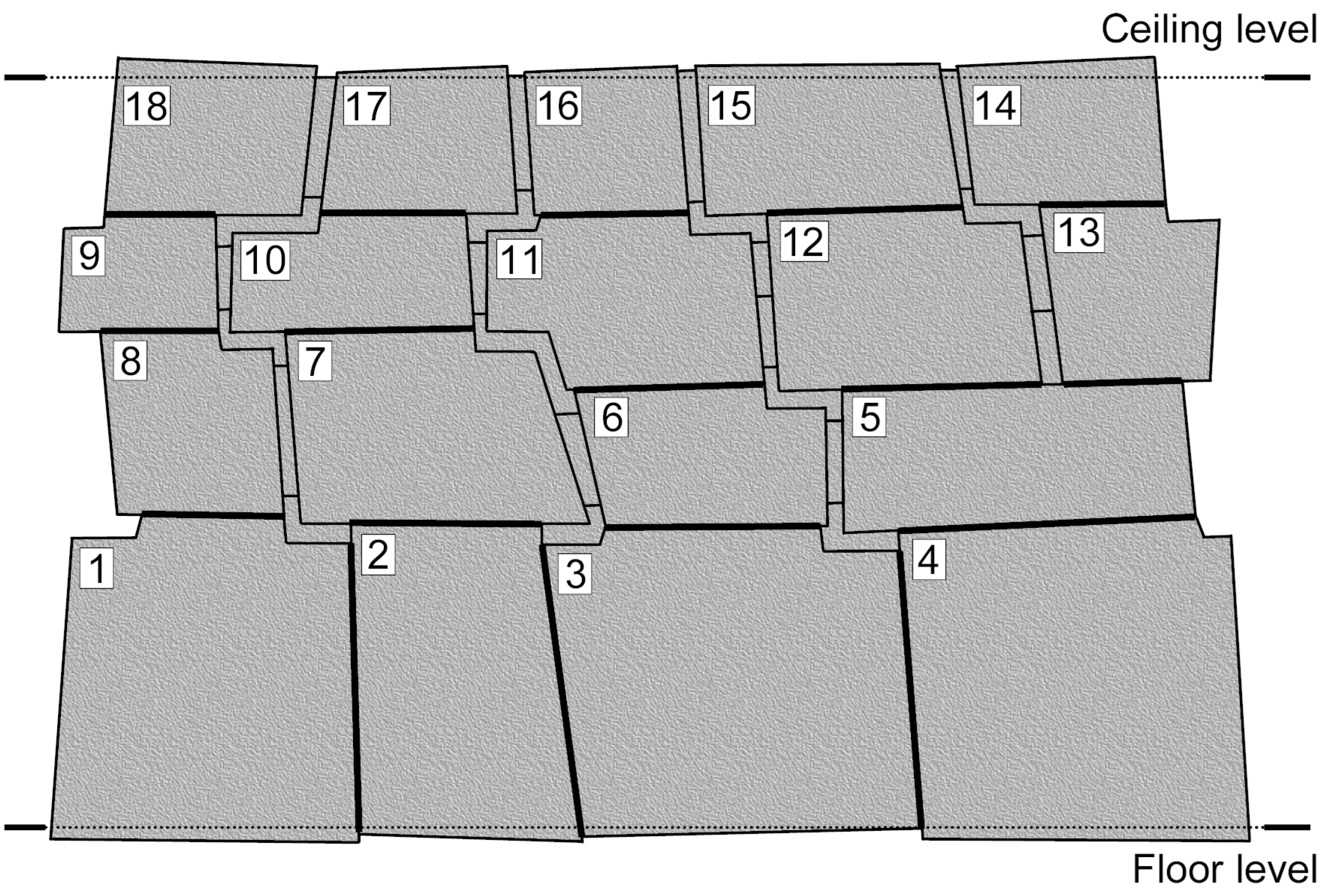

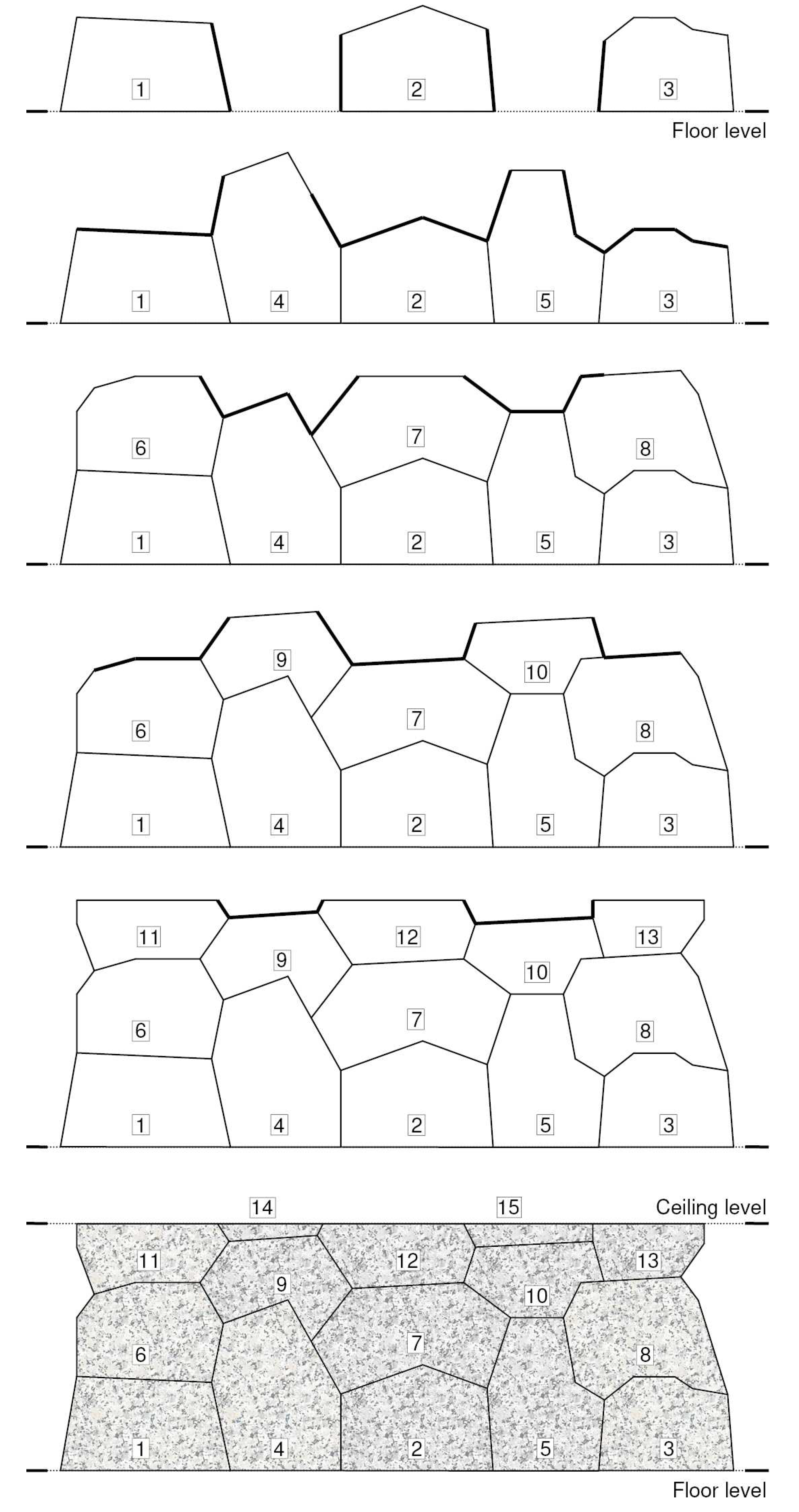

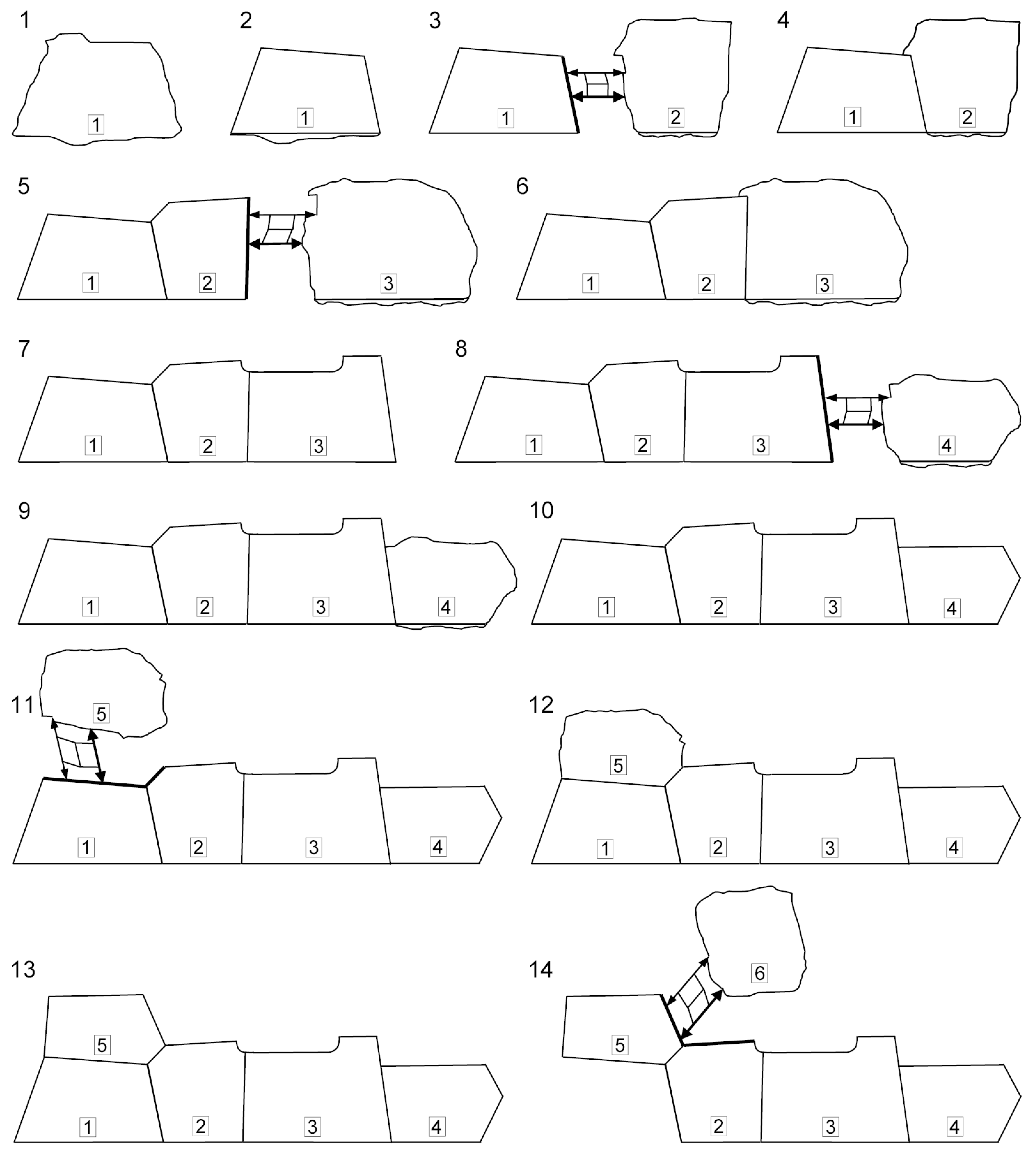

At first, the stone blocks forming the first course of the masonry are processed. For the first block of the first course, a preprocessed large-sized stone of arbitrary shape (see

Section 1.2) is taken and put on the ground with its backside down so that its untreated front face would be approximately horizontal (see

Figure 6, pos. 1). In what follows, the arbitrary processing of the stone block faces, the fitting of the adjacent blocks by means of the topography translator, a trial assembly of the wall of polygonal blocks on the ground in the horizontal position, and the horizontal alignment of the front faces of the blocks into a single wall plane will be carried out for this position of the blocks. Next, the top face and the side faces are formed in the first block (pos. 2). Processing of these faces is arbitrary – an initial irregular side surface of a natural stone is replaced with a set of the approximately flat faces. In what follows, the mentioned faces will no longer be processed.

Now, a straight line is drawn on the front surface of the first block, indicating the edge of the block base (in the figure, these lines are the horizontal lines in the outlines of the blocks of the first course starting from pos. 2). After that, a surface strip (draft [

22], it is not shown in the figure) is processed along the perimeter of the front side so that the surface in this area is strictly horizontal. Horizontality check is carried out using the plumb level. If the project provides for a beveled edge (not shown in the figure), then it is formed along the perimeter of the block front side with the exception of the base. A marking gauge [

59] is used to scribe the beveled edge boundaries. [

60] Two lines are scribed with the marking gauge – one on the side surface of the block, the other on the front one. The beveled edge is made according to the generally accepted way. [

61]

In width, the plane area under processing corresponds to the size of the foot of the plumb level legs57 (as well as to the size of the base of equal height pyramids, see the explanation below) plus some distance from the edge reserved for the beveled edge, if any. Now, using a square for checking, one forms a flat base of the block, which makes a right angle with the plane of the front face (pos. 3). On this, the processing of the first block is considered completed.

For the second block of the first course, another preprocessed large-sized stone of arbitrary shape is taken, which is put next to the first block (pos. 3) on the ground with its backside down so that its untreated front surface would be approximately horizontal, and the base line drawn on the block would be parallel to the base line of the first block. The second and subsequent blocks of the first course are laid along the construction cord defining the line of the bases of these blocks.

Figure 6.

Processing sequence of stone blocks using the topography translator. The polygonal masonry is represented by eight blocks laid in two courses of four blocks in each course. The sections, by which the stone blocks are mated, are shown by a bold line. Except position 22, the stone blocks lie on the ground on their backsides. The translator is shown in a simplified form. Movements of the carrying rod over the processing surface related to the exhaustion of the translator's action range are not shown. To transfer the U-shaped recesses, the bent tips are screwed in into the measuring rod instead of the straight ones. The straight-line sections of the interfaces between the blocks are only depicted as straight-line ones; actually, they are curved somewhat.

Figure 6.

Processing sequence of stone blocks using the topography translator. The polygonal masonry is represented by eight blocks laid in two courses of four blocks in each course. The sections, by which the stone blocks are mated, are shown by a bold line. Except position 22, the stone blocks lie on the ground on their backsides. The translator is shown in a simplified form. Movements of the carrying rod over the processing surface related to the exhaustion of the translator's action range are not shown. To transfer the U-shaped recesses, the bent tips are screwed in into the measuring rod instead of the straight ones. The straight-line sections of the interfaces between the blocks are only depicted as straight-line ones; actually, they are curved somewhat.

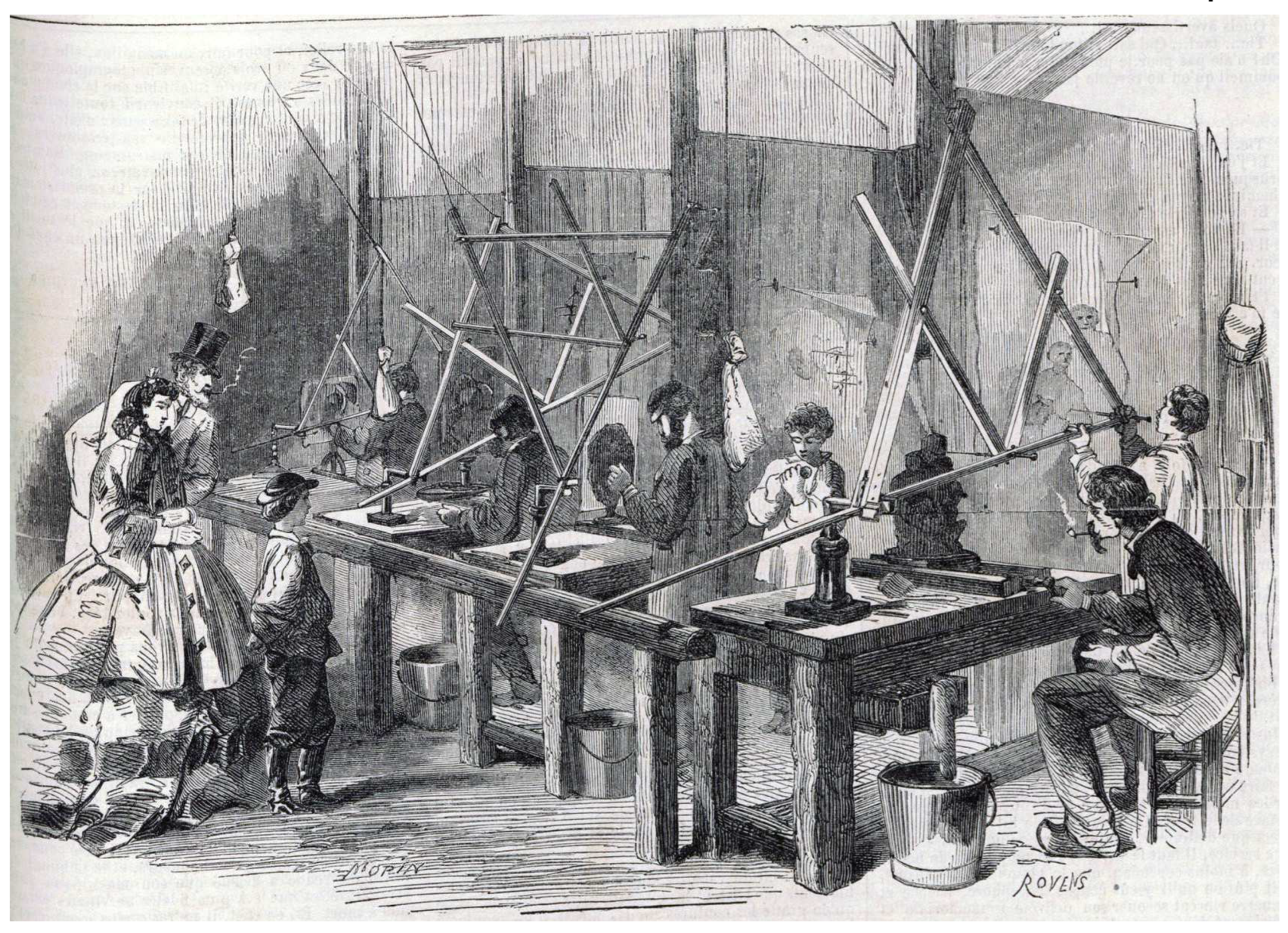

Since it is inconvenient to process the blocks lying on the ground, a trench should be dug in the ground around the block being processed, allowing a mason to work while sitting or standing. In order to significantly reduce the volume of soil being moved while providing the convenient working position of the mason, the stone blocks should be placed not on the ground, but on tables assembled from logs, sheathed with boards, and covered with a layer of chipping.

Next, the translator is installed between the first and second blocks parallel to the base lines of these blocks. After that, the topography is transferred from the side face of the first block to the side face of the second block (the end of the copied area is shown by a bold line). If the joining side faces of the blocks are perpendicular or almost perpendicular to the block bases then the translator is installed on the flat supports; otherwise, the translator is installed on the pointed supports. If the joining side faces of the blocks are tilted to the bases at too acute angles (less than 45°), then the bent tips are screwed in into the measuring rod; otherwise – the straight tips. The translator in

Figure 6 is represented in a simplified form. To avoid detail overloading of the figure, the carrying rod movements over the processed area related to the translator's range exhaustion are not shown hereinafter.

Now, the second block is joined to the first one in the horizontal position (pos 4). During joining the second and all the subsequent blocks, first of all, one monitors for accuracy of matching of the contact areas of the adjacent blocks, the minimality and constancy of the gaps. Next, on the remaining side surface of the block 2 except for the base, the rest (arbitrary) faces of this block are formed (pos. 5). As before, the processing of these faces except for the significantly curved areas in L- and U-shaped recesses (pos 7) represent rectifying of the complex initial shape of a stone billet with close to plane surfaces.

Now, along the perimeter of the front side of the second block within a certain strip, the strictly horizontal plane is fabricated exactly coinciding with the front plane of the first block. Horizontality check is carried out with the plumb level. To do this, first, one leg of the plumb level is installed on the horizontal edge of the front surface of the first block, and the other leg of the plumb level – on the processing horizontal edge of the front surface of the second block. As moving away from the edge of the first block, horizontal areas on the front surface of the second block that are ready to this moment start to be used to check horizontality.

Having completed fabrication of the horizontal area in the form of a strip going by perimeter of the front face of the second block, the beveled edge is formed (if the latter is provided for in the project). The beveled edge is fabricated along the entire perimeter with the exception of the mating section and base. The beveled edge on the mating section of the second block and on similar mating sections of all the subsequent blocks is fabricated after dismantling the horizontally lying wall before its final vertical assembly. As in the case of the first block, the beveled edge boundaries on the second and subsequent blocks are scribed on using the marking gauge. After that, a flat base of the second block is formed along the drawn line perpendicular to the plane of the front surface (pos. 5).

If the front surface of the stone blocks in the masonry should be flat according to the project, then excess stone material is removed from the front surfaces (excepting areas suitable for the pedestals/bosses formation) until an approximately flat surface is obtained. It is much easier to maintain the flatness of the wall being erected when the stone blocks have a comparatively flat front surface. The problem with the straightness and flatness of a polygonal masonry arises from the fact that such masonry does not have clearly defined courses (as in the masonry consisting of stone blocks having the same height, for example) and, consequently, its stones can not be laid along a stretched construction cord.

If, according to a project, the front surfaces of the stone blocks should have a noticeable bulge of the front surface, surface of a ragged stone, and/or a significant swell in the lower part of the block (see

Section 3.1), then pedestals (leads) are fabricated on the front surfaces to hold the straightness and flatness of the wall (especially along the wall) being erected. To define the wall plane, the pedestals are made of the same height relative to the plane of the front surface. The pedestals allow checking the straightness and flatness of the wall over extended sections of the masonry in the horizontal position using a construction cord. Also, using a construction cord and a plumb line, it is possible to check the flatness of the wall in the vertical position during its erection. Some time after finishing the vertical wall assembly, a part of the pedestals are chipped off, the remaining part are converted into bosses (see

Section 3.1).

The above steps are repeated for the third, fourth (pos. 5-10) and, if necessary, for the subsequent blocks of the first course. Having completed the first course construction, one proceeds to fabrication of the second course of the masonry (block 5, pos. 11).

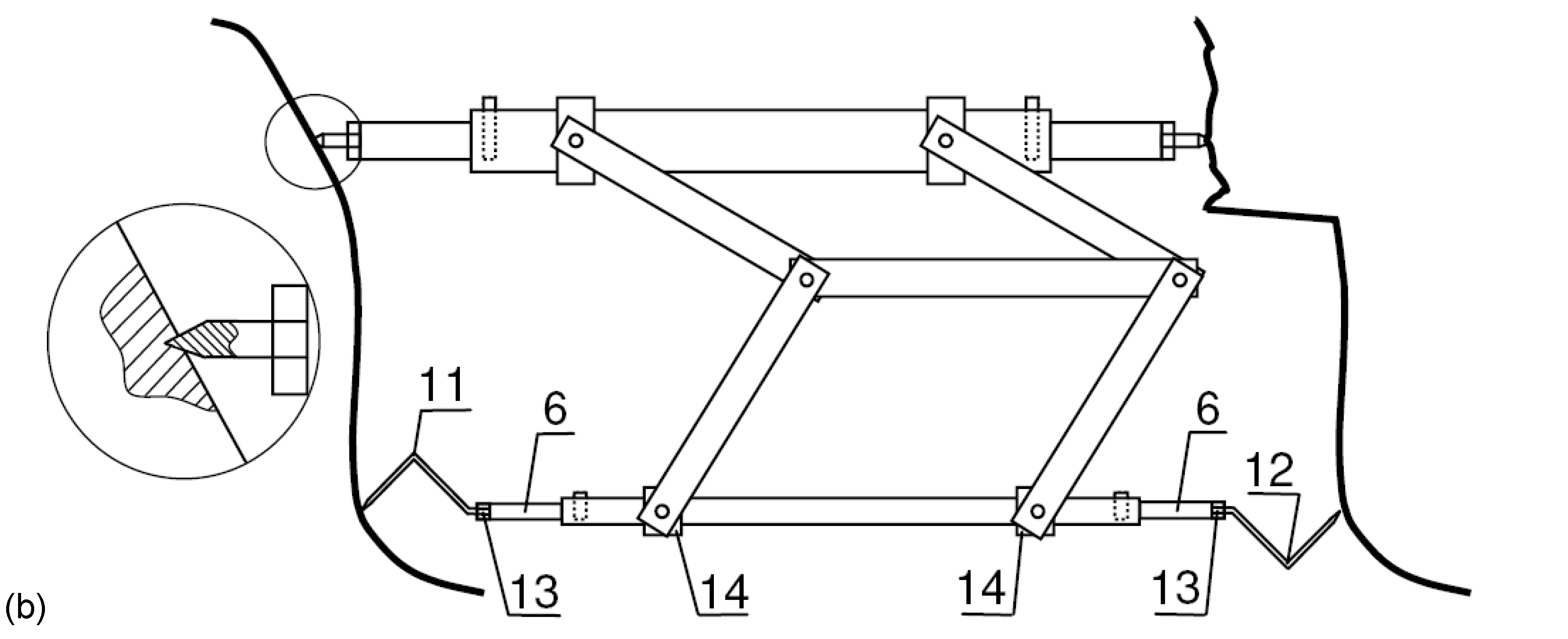

To make the second course, a preprocessed stone of arbitrary shape slightly smaller in size than the stones of the first course is taken and also put on the ground with its backside down. The untreated front surface of the stone should again be positioned approximately horizontally (pos. 11). The stone block 5 is put next to the first block of the first course to join them. The translator is installed between the blocks and topography is transferred from the top face of the first block and from a small area in the upper part of the side face of the second block to the bottom face and a small area in the lower part of the side face of the fifth block.

Unlike the blocks of the first course, where the joining of the adjacent stones took place over one side section usually, the blocks of the second and the subsequent courses are joined over more than one section. As a rule, the joining of these blocks is carried out over the base and the lateral side adjacent to the base (pos. 11). If the angle between the neighboring sections being copied is close to 180° then the translator is installed on the flat supports. Otherwise, the translator is installed on the pointed supports.

The block to be fitted should be located relative to the masonry so that the amount of stone material removed is minimal. The translator should be installed on the pointed supports so that it is tilted approximately equally to both sections being copied. If the angle between two copied sections is too sharp (less than 45°) then the bent tips are screwed in into the measuring rod, otherwise – the straight tips. If the bent tip is unable to penetrate into a sharp interior corner then such angle should be replaced in the masonry by a rounding of suitable radius.

Having completed the transfer of topography in the interface area, the fifth block is jointed to the first and second blocks (pos. 12). Then, the rest (arbitrary) faces are formed on the remaining side surface of block 5 (pos. 13). After that, a strictly horizontal plane exactly coinciding with the front planes of the first and second blocks is fabricated along the perimeter of the front side of block 5 within some strip.

The horizontality check is carried out by means of the plumb level. To do this, first, one leg of the plumb level is put on the horizontal edge of the front surface of the first block, and the other leg of the plumb level – on the horizontal edge of the front surface of the fifth block being processed. As moving away from the edge of the first block, the horizontal edge of the second block starts to be used to check horizontality. Finally, moving away from the edge of the second block, the horizontal sections ready by this moment on the front surface of the fifth block start to be used to check horizontality. Having finished the fabrication of the horizontal edge of the front face, the beveled edge is formed (if it is provided for) on the remaining sections of the fifth block excepting for the reciprocal part of the interface area.

If there are suitable height stone excesses on the front surface of a block in locations convenient for placing pedestals, then the pedestals of the set height are fabricated in these locations. Using the new pedestals of the current block and the pedestals made earlier on other blocks, one checks the straightness and flatness of the current block in the masonry applying the construction cords. In case of deviation from the straightness and flatness, one adjusts the current block position correspondingly, while trying to keep the smallest gaps and their constancy.

Note that the interface sections between the blocks in

Figure 6 are just shown as rectilinear. In practice, all these sections are curvilinear to greater or lesser extent. Having finished the block 5 processing and checking its face surface matching with the wall plane (pos. 13), block 1 can be removed from the temporary masonry (pos. 14) and passed for the final wall assembly (pos. 22). Block 1 and others like it can be removed from the temporary masonry and passed to the final wall assembly, if the block does not participate in the flatness check (does not have pedestals) or its removal will no longer significantly affect the detection of deviations from the wall flatness of the current and subsequent blocks. The processing of block 6 is similar to the processing of block 5 (pos. 14-16).

Processing of block 7 for the U-shaped recess consists of two steps. First, the lateral side of block 6 and an approximately half of the U-shaped recess in the blocks 2 and 3 are copied, which is the first (direct) L-shaped recess (pos. 16). Then, the copying of the U-shaped recess continues on the second (counter) L-shaped recess (pos. 17). Copying of the direct L-recess (pos. 16) can be performed by both the straight tips and the bent tips (in

Figure 6, both types of the tips are shown together for clarity). Copying of the counter L-recess (pos. 17) is performed using the bent tips. Note that during the transfer of the direct and counter L-shaped recesses, the translator orientation in space should remain unchanged.

If the straight tips were initially screwed in into the measuring rod while transferring the U-shaped recess then they should be replaced with the bent ones at the second step (the assigned distance between the ends of the probe and pointer should not be changed). If the bent tips were initially screwed in into the measuring rod while transferring the U-shaped recess then at the second step they should be turned by 180° by screwing in the probe and screwing out the pointer (or, vice versa, by screwing out the probe and screwing in the pointer).

In the case of a large number of acute angles and U-shaped recesses in the masonry, it is convenient to use the topography translator whose measuring rod has cylindrical hinges providing free rotation of the measuring rod around its own axis (see

Figure 5b). The adjustment of the position of the bent tips of the measuring rod for operation on the first and second L-shaped recesses is actually reduced to revolution of the measuring rod around its axis by an angle suitable for the given location.

Having installed block 7 at its place (see

Figure 6, pos. 18), the remaining side surface of this block is subjected to the arbitrary processing (pos. 19). Having completed block 7, block 2 can be removed from the temporary masonry (pos. 19) and moved to the polygonal wall construction site for its final installation (pos. 22). If a block of the previous course is unextractable or hardly extractable at the current stage of the block fitting then this block can be extracted later, when its retaining blocks will be completed. The main restriction on removing a finished block from an unfinished masonry is the presence of pedestals on it involved in flatness checking of the wall being created. Fitting of block 8 (pos. 19-21) is clear from the figure. If necessary, the third and subsequent courses of the polygonal masonry are fabricated similarly to the fabrication of the second course of the masonry.

Having completed the trial assembly of the wall of polygonal blocks in the horizontal position, the wall is disassembled. On the reciprocal sections of the interfaces of the extracted blocks, the beveled edges (if they are provided for by the project) are completed according to the accepted way. After that, the wall is finally assembled on a prepared site.

The final appearance of the wall consisting of eight blocks laid in two courses is shown in the figure, pos. 22. Although the obtained masonry contains a keystone (block 7), the assembly, for example, of the second course of such masonry does not necessarily have to be completed by installing this stone at its position. As one can see, the wall assembly can be carried out sequentially in the order of fitting of the stones. The base planes of the stone blocks of the first course can be fabricated at an angle slightly less than the right angle to give the wall a slight slope. Processing of the backsides of the stone blocks of a bearing wall is carried out after its assembling. The backside of a retaining wall is not processed in any way.

Some time after wall erection, the size and constancy of the gaps as well as verticality (a set slope) and flatness of the wall are checked. Verticality and flatness are checked using the plumb line and construction cord. If the specified wall characteristics are within the acceptable values, some of the pedestals are removed from the front surface according to appropriate aesthetic criteria and appearance of the remaining ones is modified to the required style turning them into bosses (see details in

Section 3.1).

Instead of the pedestals or together with the pedestals, pyramids of the same height can be used, which tops define the position of the horizontal plane parallel to the horizontal plane of the front face[

22,

62]. Most of the pyramids are put on the horizontal areas along the block edges. For some blocks approximately in the center of the front faces, it is possible to make recesses, whose bottoms coincide with the horizontal plane of the front face. During the trial assembly of the wall in the horizontal position, the pyramids are simply installed along the edges of the blocks on the horizontal areas and put in the recesses. By applying the construction cords to the tops of the pyramids and/or installing straight verifying bars on the pyramid tops, it is possible to determine the coincidence acceptability of the front planes of the stone blocks with the wall plane.

To check the flatness of the polygonal masonry during the vertical wall assembly, the pyramids should be somehow secured to the edges of the blocks and in the specified recesses. If the recesses are deep enough, the pyramids can be fixed in the recesses with wedging eccentrics or with wooden wedges in the simplest case. Since the recesses for these pyramids spoil the appearance of the polygonal masonry, their use was most likely limited to the masonry whose final appearance of the front surface represented a plane or ragged stone. In the latter case, the recesses were simply chipped off some time after wall erection.

While interfacing, the corner blocks connecting walls, say, at 90° angle are laid on the ground generally in the same way as the conventional blocks. One should only ensure the horizontal position of the plane of the corresponding front face of the corner block and its coincidence with the plane of the wall being made. To do this, a recess of a suitable shape and depth is excavated for the corner block in the ground. Corner block fixation on the ground is carried out in the same way as the regular one – with the help of the wedging stones. After mating the blocks of the first wall, alignment marks are applied to the corner blocks with paint; after that the stone blocks, excepting for the corner blocks, are sent to the final assembly site.

Further, the fitting of the blocks of the second wall starts from the first lowest corner block, which is rotated by 90° so that the second front face of this block looks up now. After that, the first block of the second wall is mated to this corner block as described above. Next, as the blocks of the second and subsequent courses of the second wall are mated, the corner blocks are joined to each other according to the alignment marks.

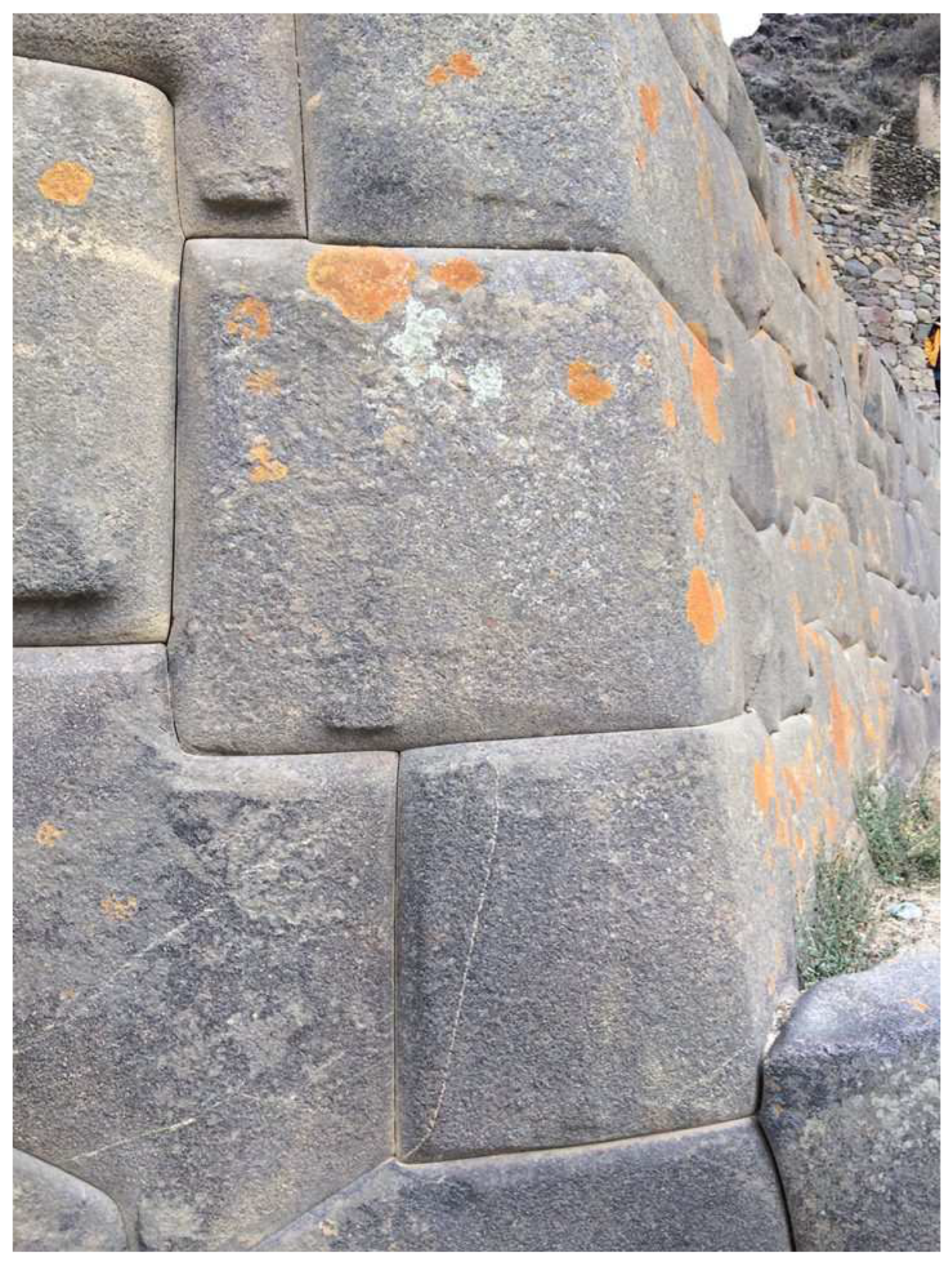

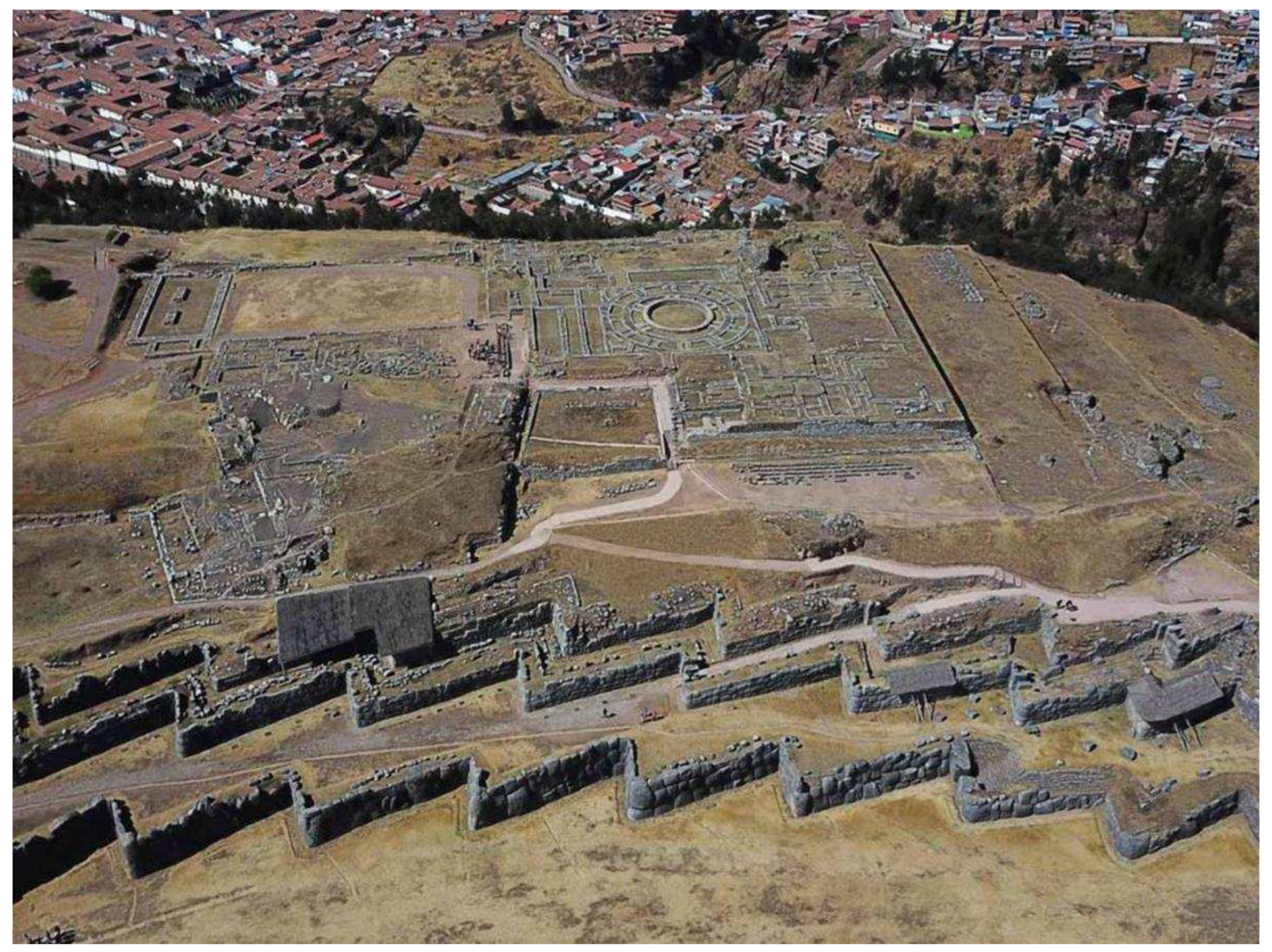

Thus, when using the topography translator, walls with corner blocks are erected sequentially by separate sections bounded on the left and right by the corner blocks. When using a 3D-pantograph, the mentioned restriction is absent, since the processing of ordinary blocks and corner blocks is carried out according to the models and does not require an intermediate placement of the stone blocks on the ground and their mating in the horizontal position during fabrication (Hatunrumiyoc Street in Cusco, Ollantaytambo). In the case of the 3D-pantograph usage, the final assembly of the walls with corner blocks is performed sequentially course after course taking into account the lock blocks in the course, if any.

Applying the topography translator, it is also possible to erect walls of two (or more) blocks thick by interfacing the block backsides of the outer wall with the mating surface of the second (inner) wall. To do this, both the walls are made in the way described above. The outer wall is assembled finally and its backside is arbitrary processed, forming the conditionally flat sections. After that, a second (inner) wall is temporarily assembled at some distance from the first wall parallel to it. The distance between the walls is set so that a stonemason can fit in the space between them and work with the hammer and chisel without much constraint. Next, the topography translator is installed between the walls as a strut; after that, the topography is transferred from the backside of the first wall to the mating surface of the second wall. Having finished the mating, the second wall is reassembled right next to the first one.

Depending on terrain peculiarities and requirements related to the structure, the order of wall joining can be changed, i.e., first, the second (inner wall) is finally assembled, and then the first (outer) wall is joined to it in the above way. When the terrain peculiarities do not allow for the specified fitting of the walls, or the walls include shared blocks, or blocks of the walls are strongly bonded [

8] between each other in the transverse direction, the polygonal masonry is made by using the clay models and 3D-pantograph; and the assembly of the wall of two or more block thick is finally carried out at the planned location course upon course. It seems that this is how the Temple of Ten Niches in Ollantaytambo was fabricated (see Photos 11 and 12), which wall has two block thickness.

2.11.4. Specifics of the topography translator application

The operation of the proposed device is based on the well-known principle of conjugation of two surfaces. In one-dimensional version, this principle is implemented in a marking tool like the marking gauge [

59]. Article [

7] presents a one-dimensional version of the principle of fitting of stone blocks close to parallelepiped shape. In article 14, a two-dimensional version of the principle of conjugation of stone blocks is taken as a basis of the method of polygonal masonry fabrication. In contrast to the method described in article 14, the operation position of the topography translator in space in the method under consideration is exactly defined and due to the double parallelogram mechanism can be arbitrary.

In practice, the most convenient positions of the translator are close to the horizontal position as they allow the stonemason to process vertically located mating surfaces of stone blocks lying on the ground opposite to each other backside down. The front surface of a stone block is located horizontally and is fully accessible for processing also. Moreover, the blocks fitted according to the proposed method can be joined in this position with each other (adding chipping and inserting small wedging stones) that allows us to check the quality of the implemented interfaces before putting the blocks into a wall.

Unlike the 3D-pantograph, the topography translator allows to immediately correct accidental stone chips at the interface of stone blocks by copying the chipped area back on the original surface using the pointer as a probe and the probe as a pointer. When using a pantograph, to correct accidental chipping, one needs to make corrections in the mating faces of two adjacent clay model blocks.

In method 14, due to referencing the measuring rod to the vertical direction by means of a plumb line, in order to process the upper side of the block of the previous course the stonemason has to put the block of the current course, by which base the fitting is performed, above the block of the previous course that is unsafe and requires a lot of additional efforts. In particular, it is necessary to provide stops (recesses or protrusions) on the stone blocks, fabricate logs-stops, bury these logs-stops into the ground, put the stone blocks on the logs-stops at the beginning of the work, and take down the stone blocks from the logs-stops after finishing the work.

In addition, it should be possible to change position of the current block located on the support logs in order to align it in the vertical plane by the plumb line and in the horizontal plane by the construction cord. Meanwhile, platforms, scaffolds, ramps, etc. are required to access the conjugation surface being processed from the front side of the wall and to access the front side itself. Moreover, the use of the plumb line in method 14 significantly reduces stonemason productivity, as a lot of time is required to settle the plumb line during the surface treatment of the block. In addition, the use of the plumb line itself can be very difficult in the event of a strong wind.

Yet another disadvantage of method 14 is that the measuring rod, unlike the topography translator, is not fixed in the space completely. As a result, during the processing of the stone blocks, unintentional rotations of the rod around its vertical axis by small angles ±∆α will occur inevitably. The larger is the angle of rotation ∆α and the longer is the rod length l, the larger is the error ∆l related to such rotations.

Let us assume for simplicity that the measuring rod is initially located normally to two parallel flat areas of the processed stone blocks. Then the error caused by the random rotation of the rod can be estimated by the following simple formula: ∆l=l⋅(1/cos ∆α-1). Thus, for the measuring rod of even a moderate length, say, l=70 cm, we find that the error ∆l in method 14 will already exceed 5 mm for the rod deviation just by angle of ∆α=7° from the correct starting position.

Vincent Lee, the author of article 14, initially proceeded from the fact that the polygonal masonry in the Peruvian megalithic structures was created by the Indians. In accordance with this initial assumption, Vincent Lee had to use a plumb line as the simplest measuring tool that could be known to the Indians at that time. Moreover, in the method he suggested, Vincent Lee wanted to use the protrusions (bosses) and recesses on the front sides of the stone blocks of the Sacsayhuaman Fortress in some way for creating the polygonal masonry. Hence, an extremely costly in terms of the applied efforts and dangerous arrangement of the processed stone blocks one above the other arose.

In the method proposed here, the parallel movement of the measuring rod is not connected with the normal to the Earth's surface in any way and can occur at any orientation of the translator. Therefore, the fitting of the blocks and their pre-assembly are performed when the blocks lie on the ground with their backsides down. Hence, as in the case of the 3D-pantograph application, a sign of the usage of the block fitting method will be the same tilt of the chisel marks on the mating faces of the stone blocks to the direction which is perpendicular to the front surface. Only after completing the joining of the blocks of the current course on the ground in the horizontal position, the blocks of the previous course can finally be installed at their places in the wall under construction. Therefore, in the proposed method, there is no need to process the stones on the wall being erected in the cramped conditions and at the risk of life.

Topography transfer of the adjacent sections with a sharp boundary and with a smooth boundary (for example, in the form of L- or U-shaped recesses) is performed in a single operation. This means that the orientation in space of the carrying/measuring rod and the distance between the probe tip and the pointer tip of the measuring rod remain unchanged at both sections all the time. While passing to the section of the counter L-recess while transferring the U-shaped recesses, it is necessary to replace the straight tips of the measuring rod with the bent ones or to turn the bent tips by 180°, if they were used initially.

During the topography transfer, the translator is often located at angles to the joined surfaces which are different from the normal significantly (see

Figure 6). Such translator orientation in the case of the sufficiently sharp probe and pointer causes just an insignificant additional error of the topography transfer. The greater is the deviation from the normal and the larger is the radius of curvature of the probe and pointer tips, the larger is the value of this error. The bent probe and the bent pointer are intended for the cases when the straight probe is under a small angle to the surface to be copied.

The block fitting method described in the present paper could be used for construction of walls with comparatively simple polygonal masonry, where the mating surface areas have a small curvature, there are no figured cusps or sharp steps at the triple junctions (there is no “feeling of modeling”, see the next section). Since in the method under consideration, the sequential fitting of the blocks in-place is performed, the sign of this method usage will be the mounting of large blocks in the first course of masonry directly on a strengthened soil or on a pre-prepared bedrock, i. e., without the small “alignment” blocks in the first course of the masonry that ensure the correct mutual position of the large blocks of the second and subsequent courses (see more details in

Section 2.1). If we see that, according to all signs, the method of block fitting in-place was used, but the large masonry blocks lie on small blocks, then this means that the masonry was once reassembled and may have been moved here from another place. Moreover, the reassembly and/or move were performed much later than the time of the initial structure erection. The masonry quality loss after its reassembly is associated with the destruction/monolithing of contact areas (see

Section 3.3), the absence of part of the pedestals, and possibly with insufficient qualification of those who carried out this reassembly.

One more sign of the topography translator usage will be the small paired recesses located strictly opposite to each other (the larger the area of the mating surface, the greater the number of these recesses). The recesses are made at the locations where the carrying rod of the translator is installed on the pointed supports at angle to the mating surfaces. The presence of a set of low-contrast annular regions superimposed on each other on one of the mated surfaces can also serve as a sign of the use of the proposed above topography translator. One more sign of the translator usage is the presence of a “visor”, which often occurs during the block fitting (see

Figure 6, pos. 4, block 2; pos. 6, block 3; pos. 18, block 7; pos. 20, block 8). Sometimes, such visors are found on unfinished blocks, being, in turn, a sign of the block unfinisheness. [

63]

It should be noted in conclusion that the main advantage of the proposed method is that half of the mating surfaces of the stone blocks are processed arbitrarily.