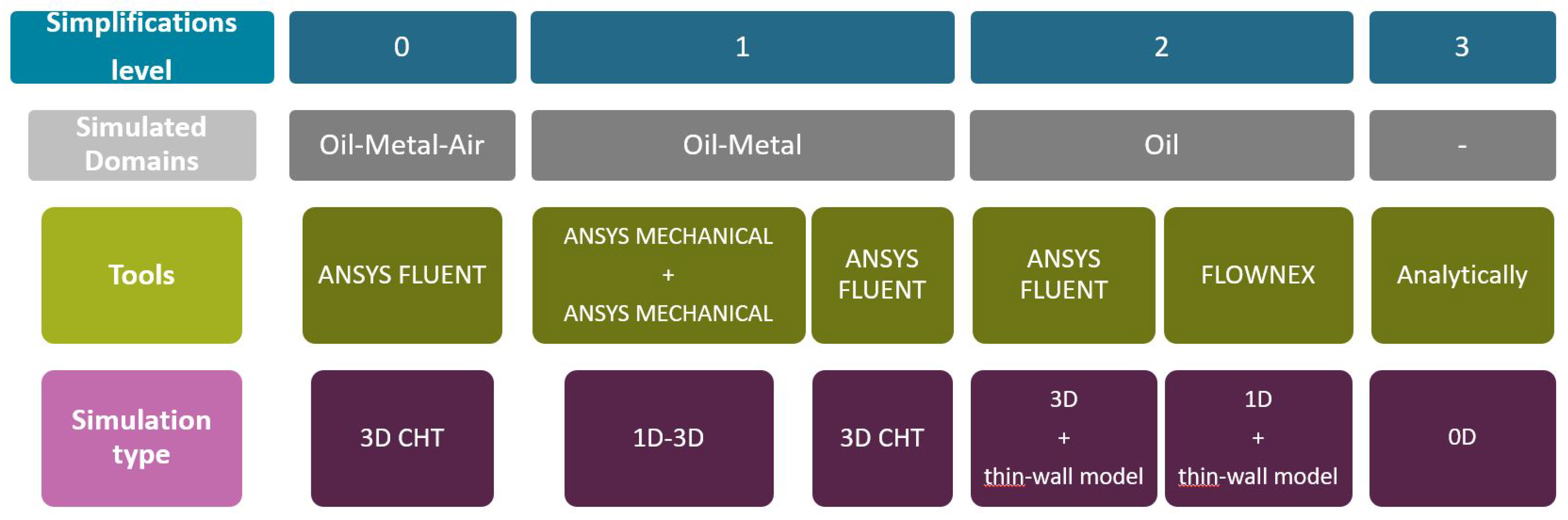

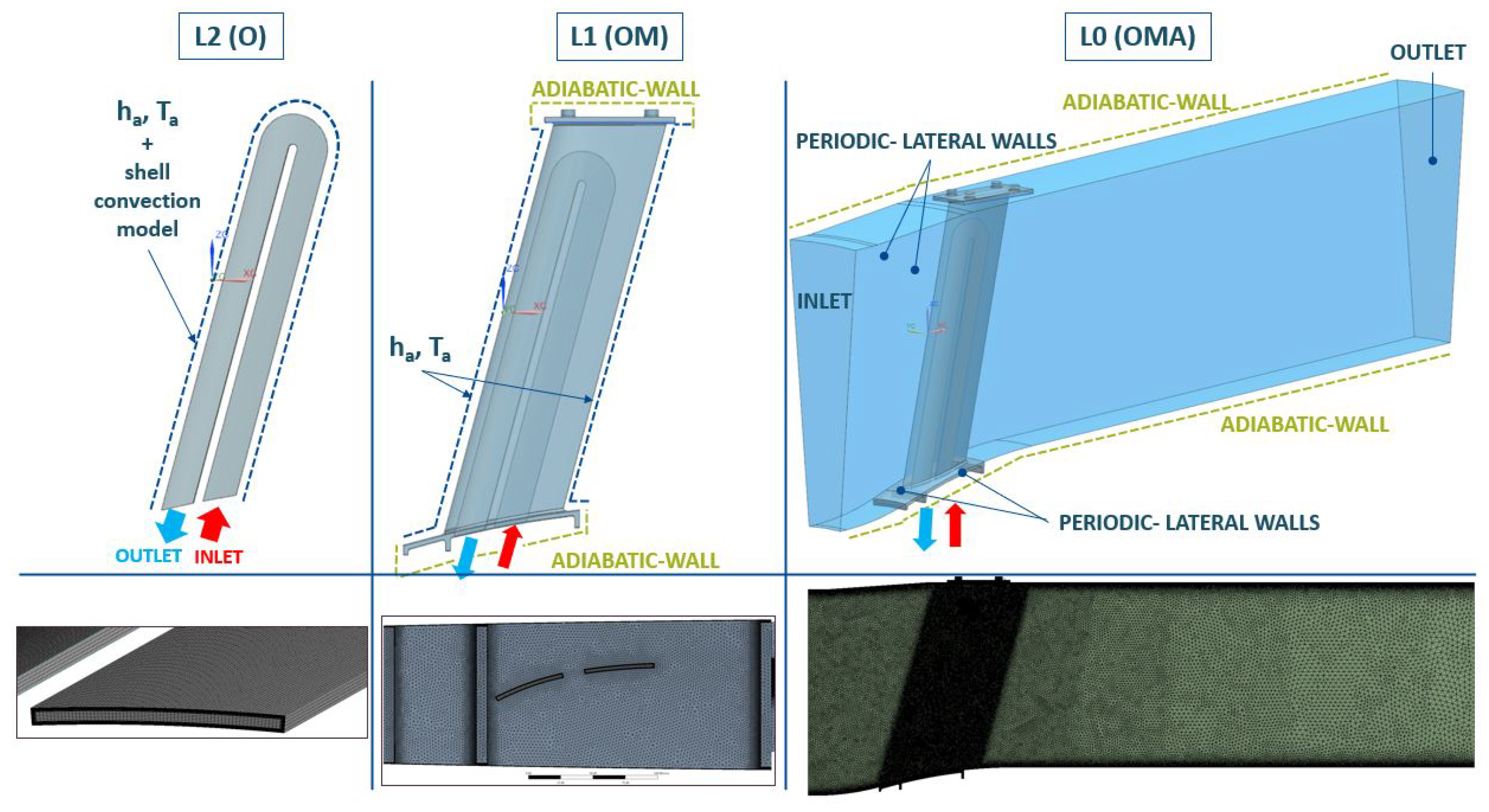

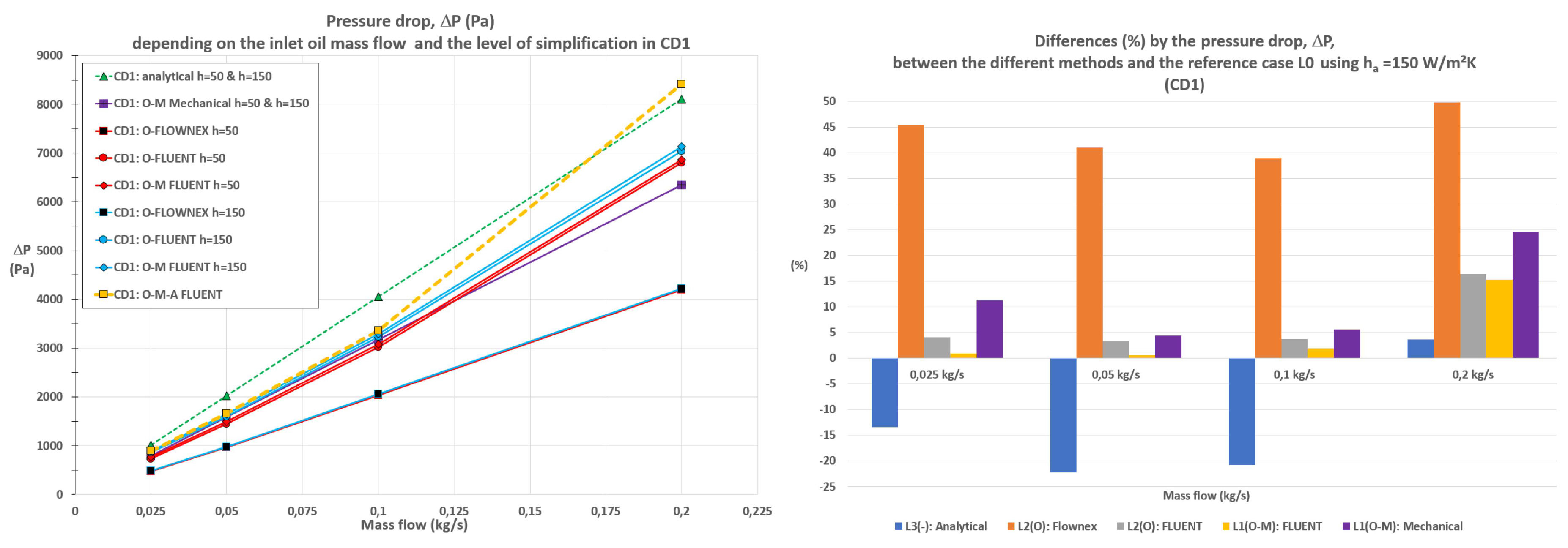

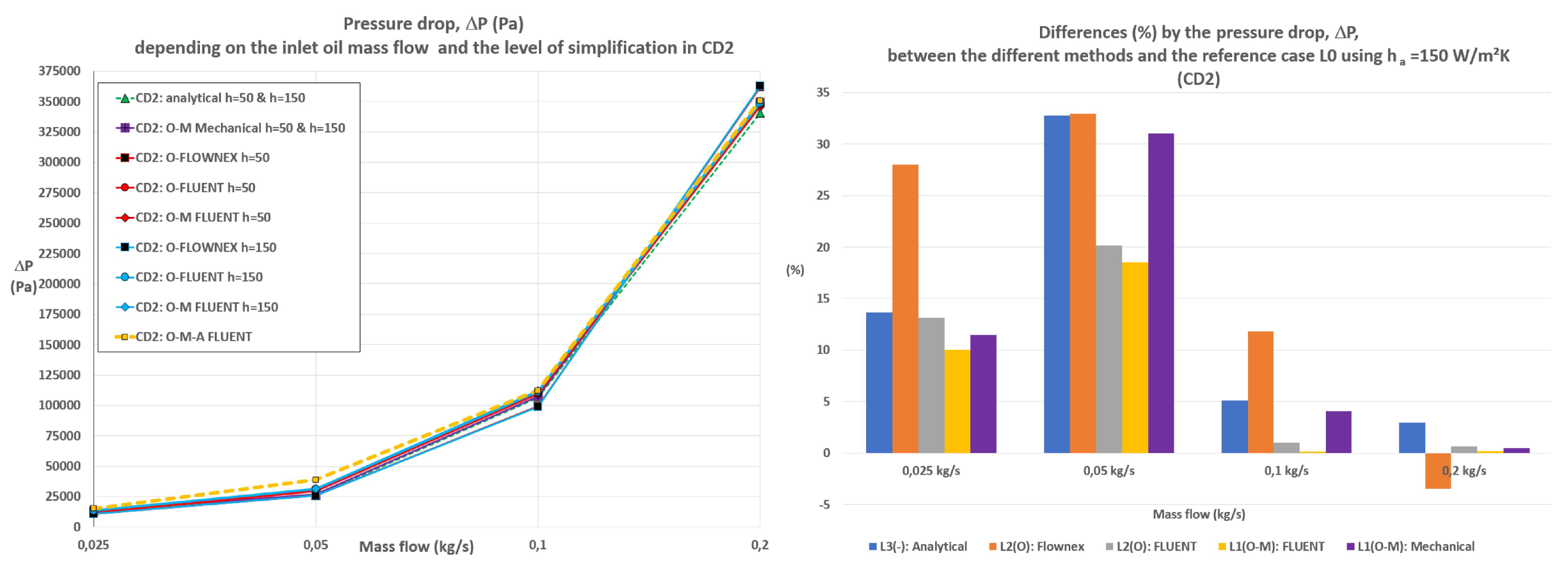

The analytical assessments belong to the simplification level 3 (L3), only analytical equations and correlations based mainly on empirical results, are used to determine the pressure drop of the oil system and the heat transmission between the hot oil and the air, assuming strong simplifications.

3.1. Heat Transfer

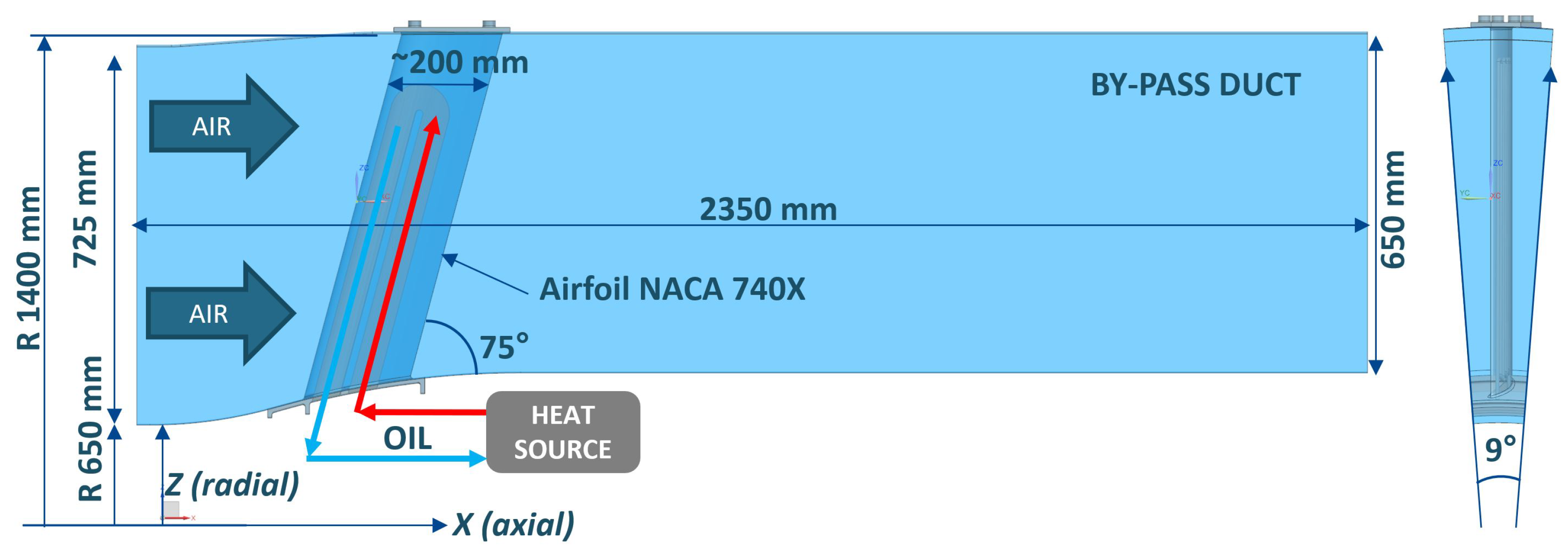

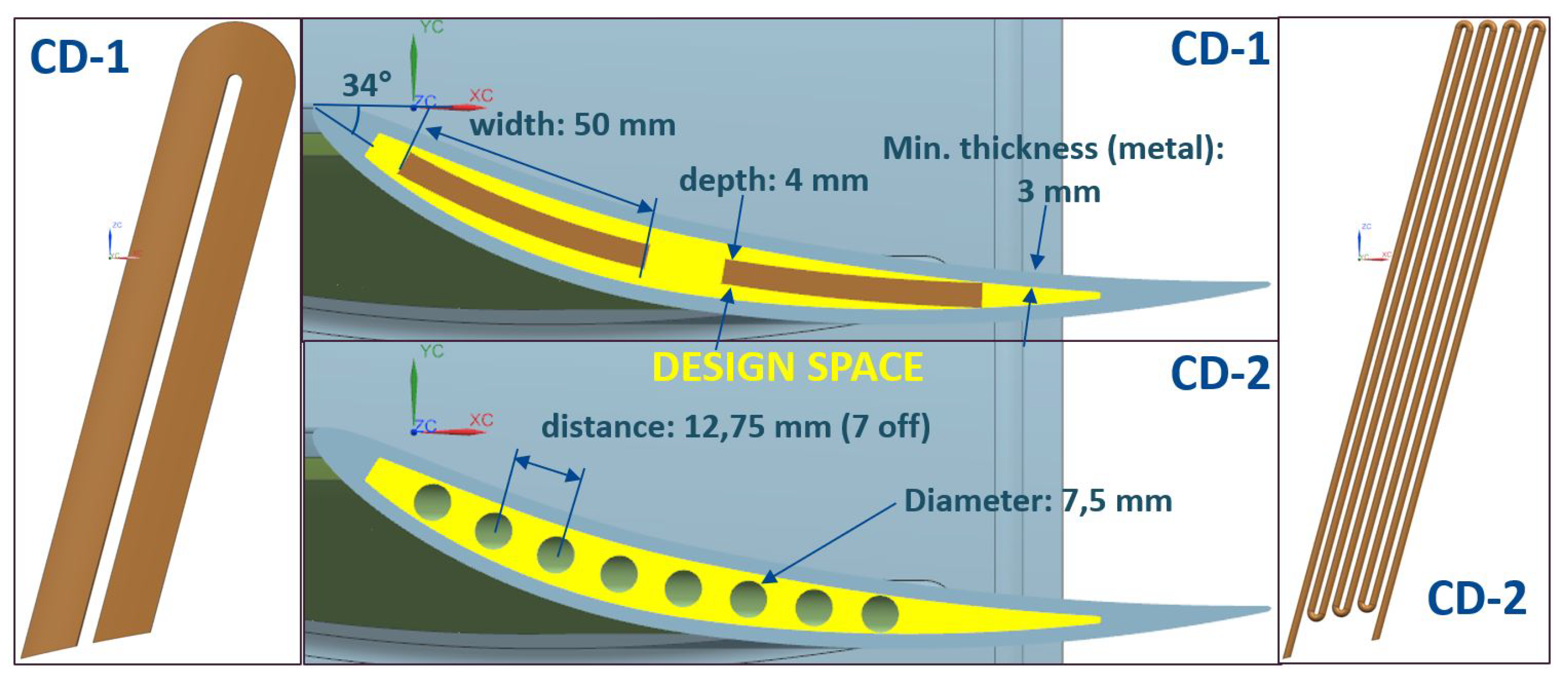

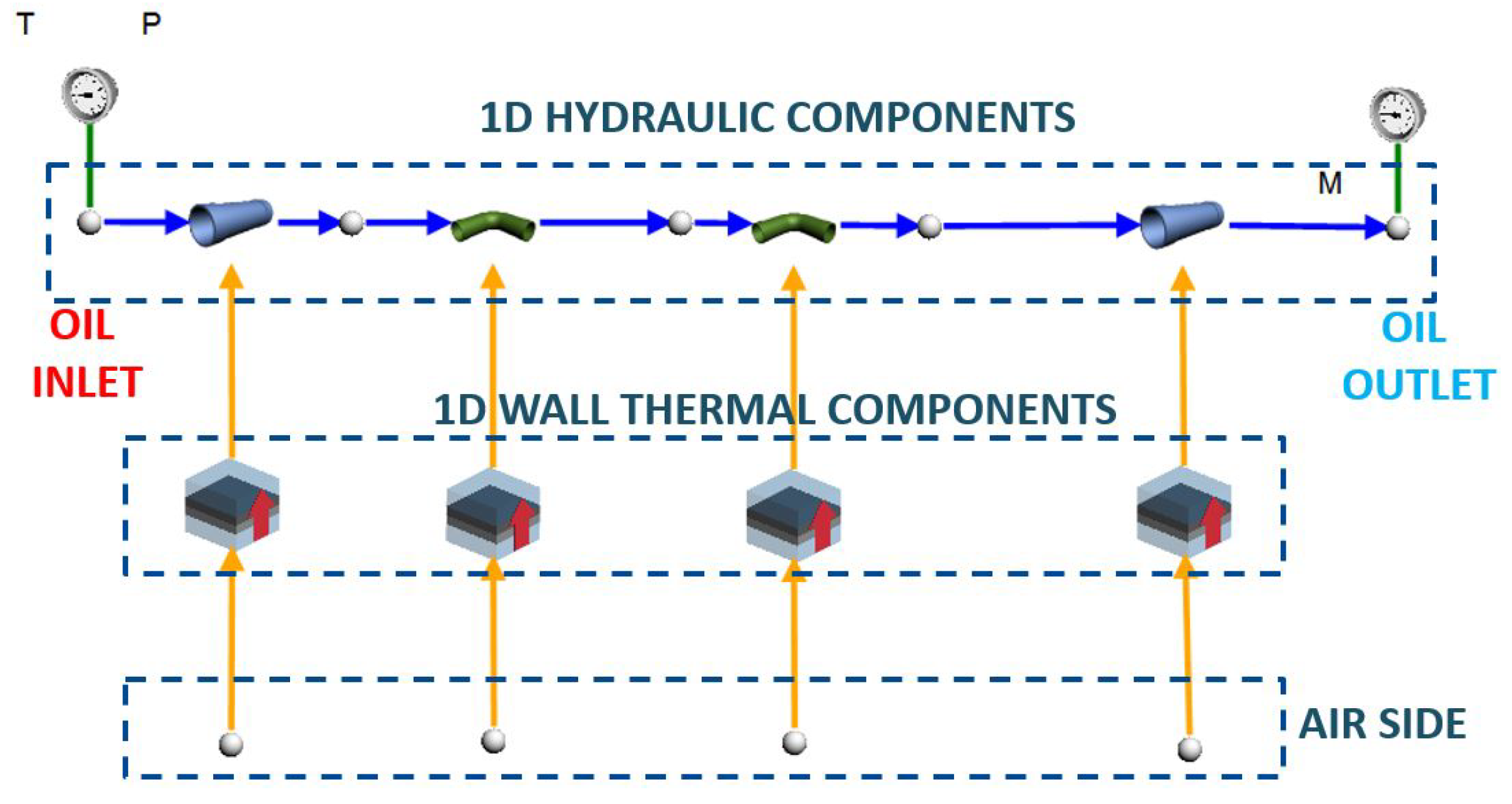

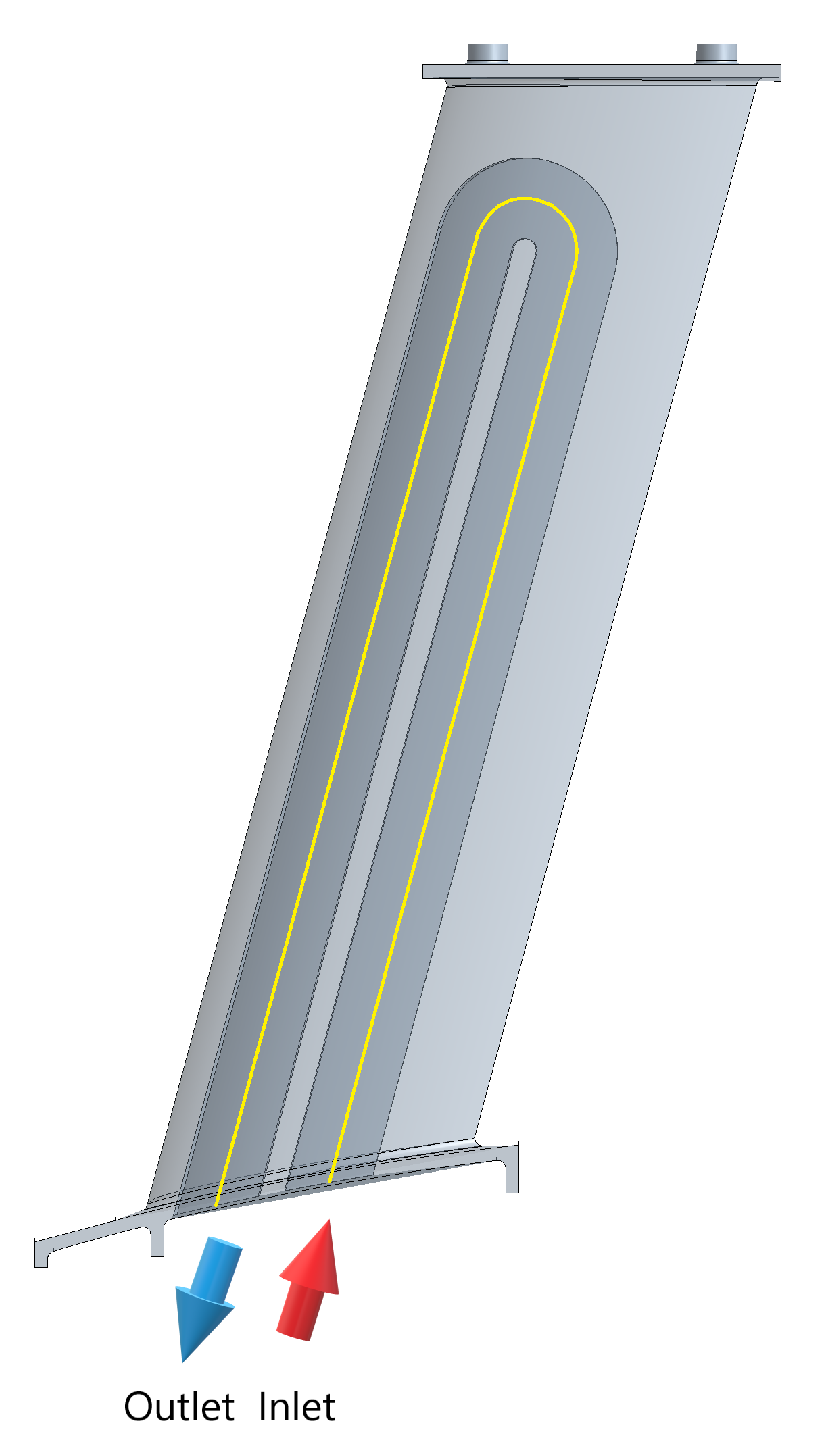

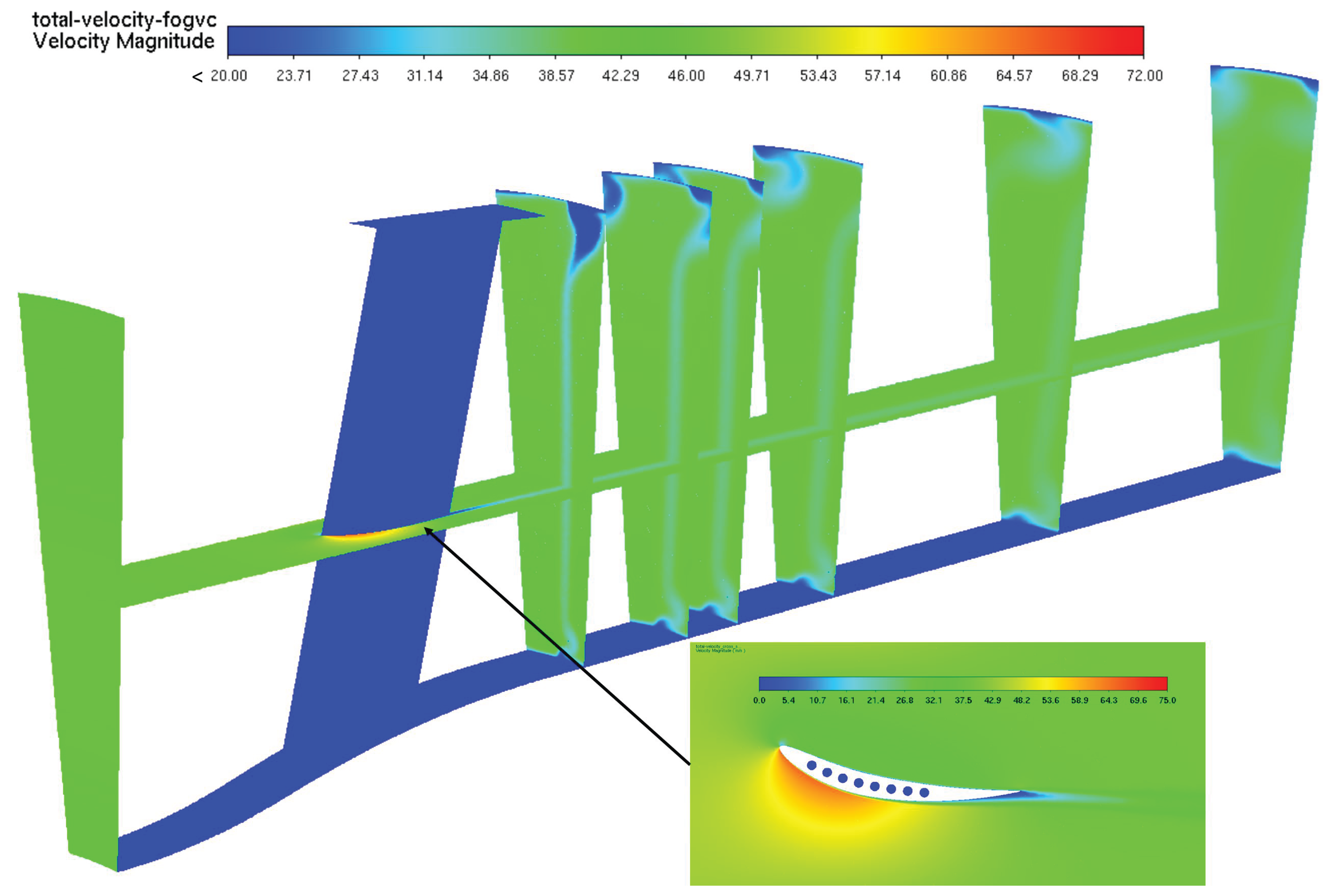

In the determination of the transmitted heat within the heat exchanger and the oil outlet temperature, some simplifications have been used. By the first one, the flow over the FOGVC is idealized as a parallel flow over a flat plate, due to the low total thickness and relative angle of the flow respect to the curvature of the airfoil. The following simplification considers how heat is transferred between the two fluid domains. In this approach, heat transmission is treated as one-dimensional, occurring only perpendicular to the flat plate, while also accounting for partial dissipation through the lateral sides of the oil cavities. This quantification is obtained more exact in L0, L1 and L2. Regarding the heat transfer mechanisms used in this work, and due to the low oil-to-air temperature differences, the radiation heat transmission is considered negligible. The last simplification refers to the fact that the oil connections are only located in the root of the FOGVC and within the airfoil. Assuming for the L3 that the main heat exchange takes place through the airfoil, it is acceptable to use as dissipation area either the oil-metal interface, the metal-air interface or an average of both. The decision, which dissipation area is employed in the analytical correlations, has a big impact, as it will be shown later, in the dissipated heat and the oil outlet temperature.

The combination of the above simplifications allow to reformulate the 3D study in the FOGVC as a 1D steady-state metal wall analysis with the following heat transfer mechanisms: internal forced flow heat convection between the oil and the metal domain, conduction through the metal part and external forced flow heat conduction with the air. As no internal generation of thermal energy exists within the metal wall, and applying the energy conservation law to the simplified 1D plane wall, the total heat transfer rate in the FOGVC,

, keeps constant through all interfaces

, where

and

is the convective heat rate at the oil-metal and metal-air interface, respectively, and

the conduction heat rate. Using the Newton’s law of cooling for the convective term,

and the Fourier’s law for the heat conduction,

where,

h is the convection heat transfer coefficient (

and

in the oil-metal and metal-air interface, respectively),

A is the dissipation area,

and

L is the thermal conductivity and thickness of the solid domain, respectively, and

the temperature difference between both interfaces, a general expression for the heat rate through the FOGVC is obtained as followed,

In the above equations, and represent the free stream temperature of the oil and air, respectively.

Applying an electrical analogy to the FOGVC thermal circuit, 3 thermal resistances can be identified on the equation

3:

,

and

but only the

can be calculated without further analysis because is composed of known variables. Moreover an overall heat transfer coefficient,

U, can be defined based on the total thermal resistance of the wall plate. The main drawback of the equation

3 to determine the total dissipated heat and the outlet oil temperature is that the

is unknown. An option to overcome that is the log mean temperature difference (LMTD) method [

25], but due to its iterative nature, an alternative method is preferred. The number of transfer units (NTU) method solves this issue by relying only on the effectiveness of the heat exchanger,

, the minimum heat capacity rate of the fluids,

, and the temperature difference of the fluid at the inlets,

In the above equation, and represent the free stream temperature of the oil and air at the inlets, respectively.

Key factor by the NTU method is the determination of the effectiveness

with values staying between 0 and 1. An alternative definition of

for any heat exchanger [

25] based on the heat capacity ratio,

and the number of transfer units (

) is,

being the definition of

as followed,

There are some expressions of the equation

5 available, depending mainly on the type of the heat exchanger (parallel- or counter-flow, shell-and-tube, cross-flow with simple pass) and on

. In

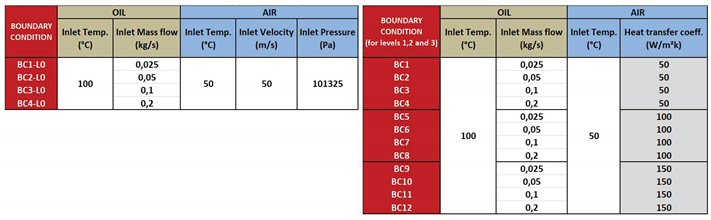

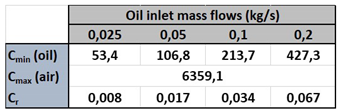

Table 2 the values of

,

and

are summarized being the same for CD1 and CD2.

The results show that the air capacity rate is much larger than that of the oil, meaning that the air temperature remains almost constant after the FOGVC. Since the values of

remain very close to zero,

is assigned a value of zero. This allows the following equation to be used to assess the effectiveness,

:

To confirm that the equation

7 is valid for our purpose, a comparison with

-expressions for a counter-flow and a cross-flow with unmixed fluids heat exchanger has been made with differences under 1% confirming the validity of the assumption.

The last step to assess the heat transfer using the NTU method is the determination of the number of units of the heat exchanger using the equation

6. For that, the overall heat transfer coefficient,

U, and the dissipation area should be assessed. Before the assessment of

U is explained, the decision about which dissipation area is used for the 2 interfaces in the calculations is needed. As dissipation area can be used the oil-metal interface area (smallest area),

, the average method proposed in [

26]:

, the arithmetic mean of the 2 interfaces:

, or the metal-air interface area with the highest value,

. In the

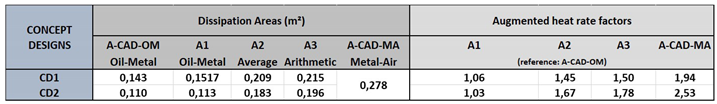

Table 3 the total values for the CD1 and CD2 can be seen and the augmentation heat rate factors resulting by comparing the above proposed dissipation areas with the CAD’s measurement of the oil-metal interface, the smallest one.

The results show that the augmentation of the heat rate taking as reference the smallest area, , vary between 1.06 and 1.94 times by CD1 and between 1.03 and 2.53 times by CD2. By using , the highest augmentation factor is introduced in the calculations obtaining too optimistic heat rates, which could provoke malfunction and overheating in the heat source. One alternative would be , but as later shown by the numerical results (L0, L1 and L2), the heat dissipation is not only concentrated in the vicinity of the oil cavities but in an wider area, which means that and are better alternatives to be used. Due to the above reasons, is a good compromise for the thermal resistances, as the differences with A2 are insignificant.

The metal thermal resistances for CD1, , and CD2, , can now be assessed.

To calculate the heat transfer coefficient of the metal-air interface,

, needed to determine the thermal resistance

, the following expression is employed:

where

represents the non-dimensional Nusselt number,

the thermal conductivity of the air and

x a characteristic length where the

number is assessed. Nusselt convection correlations of an external flow over a flat plate, semi-empirical equations depending on the non-dimensional numbers

and

, are employed to determine the

number. To determine the appropriate correlation for our problem, it is essential to identify the location on the airfoil where the flow transitions from laminar to turbulent. Using the recommendation of Incropera et al. [

25] for external flows, this transition takes place where the

, being

,

and

the dynamic viscosity, the density and the free stream velocity of the air, respectively. For our airfoil, with a chord length of 0.2 m, the

m is located very closed to the trailing edge. Hence, 2 possible Nusselt correlations can be used, assuming the use of average values for

with

m instead of local one:

By the equation

9, the average Nusselt number,

, is assessed assuming a mixed flow. As the laminar flow is presented over circa

of the whole chord length, an alternative Nusselt correlation for laminar flows can be used:

The assessment of the non-dimensional numbers

and

, being

, the specific heat, is carried out as followed: the ideal gas law [

27] is used to determine the air density,

:

where

R the ideal gas constant and

and

are the pressure and temperature of the air, respectively. By the air dynamic viscosity,

, the Sutherland’s Law with 3 coefficients is used [

27]:

taking the reference viscosity,

, the value

kg/ms and the reference temperature,

. S is the effective temperature or Sutherland constant with a value of 110.56 K. The last two material properties of the air to be calculated are the specific heat,

and the thermal conductivity

. By the specific heat, a 3

rd-degree polynomial function of T is used [

27]:

where the coefficients

and

take empirical values. In the case of the thermal conductivity,

, a parabolic function of T with empirical coefficients is used:

Knowing the above material properties for the air, the

and

number take the values 0.71 and

, respectively and using the flat plate correlation for mixed flow, equation

9, a heat transfer coefficient of

is obtained, presenting a difference of circa

to the results obtained with the laminar correlation

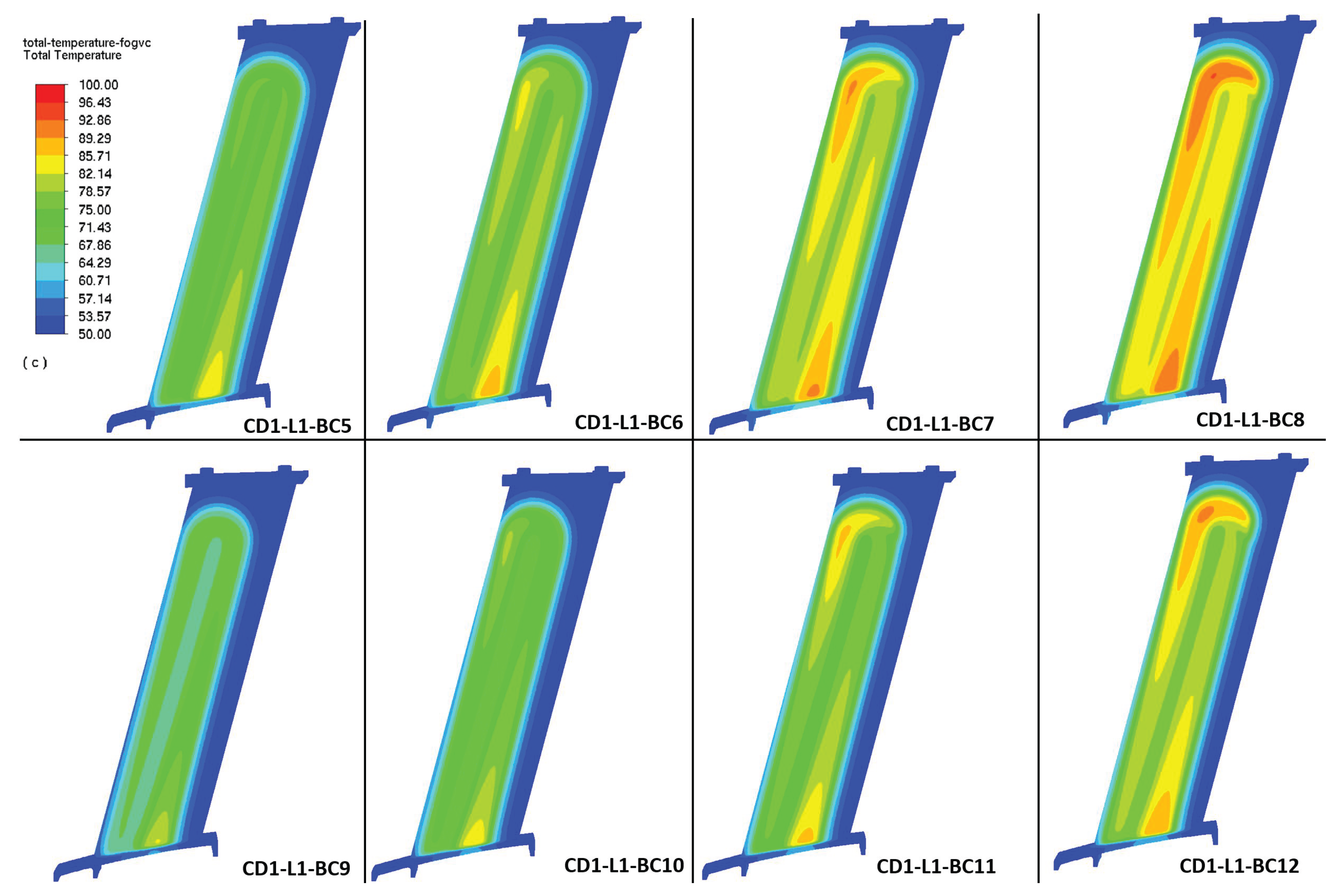

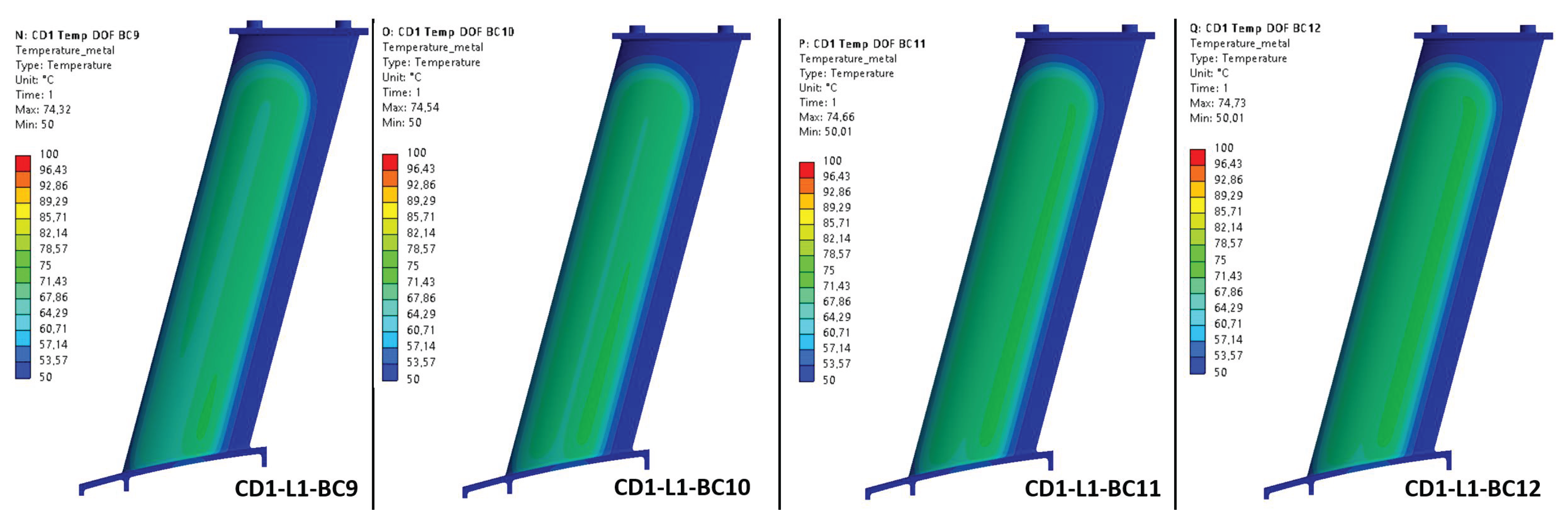

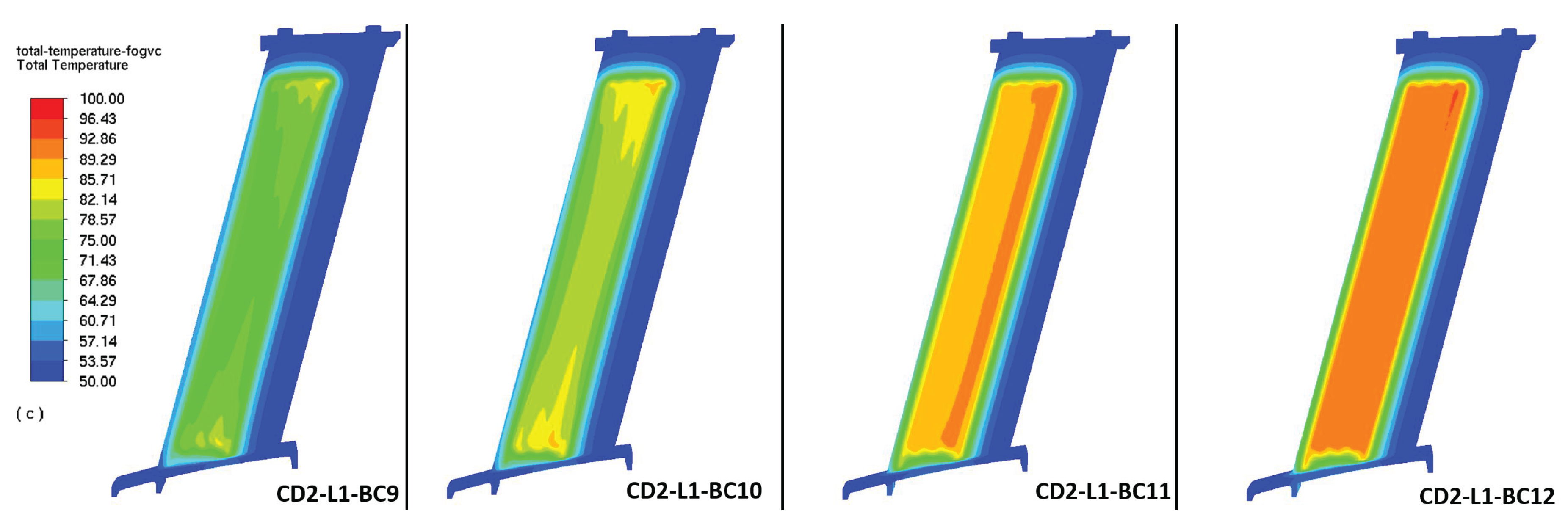

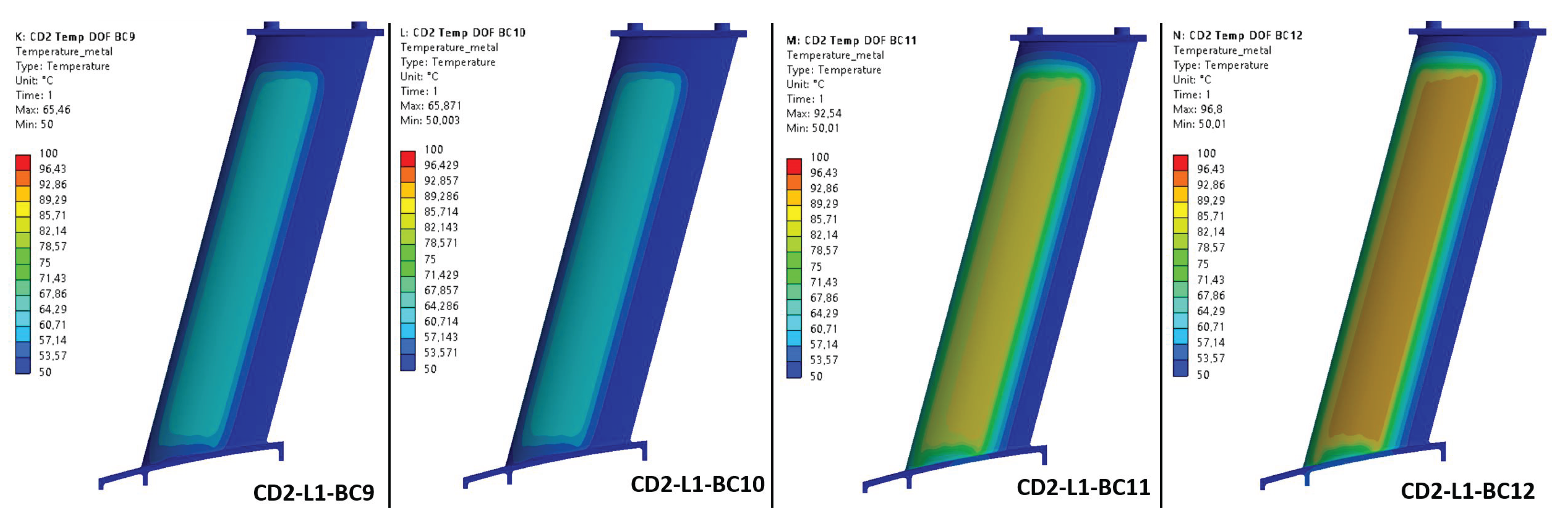

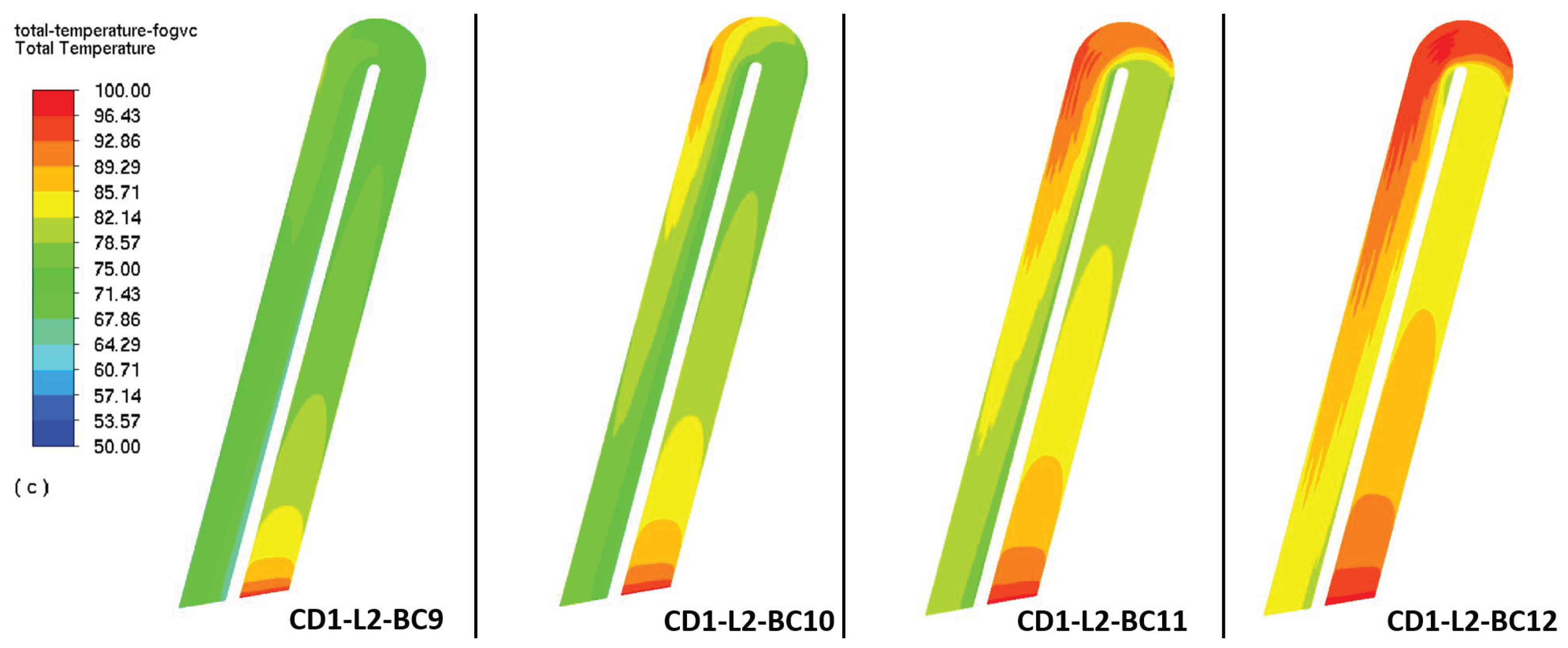

. In order to obtain a better understanding of the air side heat transmission, a range of

between 50 and 150

instead of the above analytical values has been employed as boundary condition in the numerical simulations at levels L1 and L2, see

Table 1. As the transition laminar-to-turbulent take places over the FOGVC surface, the heat transfer coefficient for mixed flow will be used to calculate the air thermal resistance, being

and

. Actually only one thermal resistance for the air side is needed, if the dissipation area is constant. In our case, the dissipation area is an average of the 2 fluid-solid interfaces making needed the assessment of a second thermal resistance for CD2.

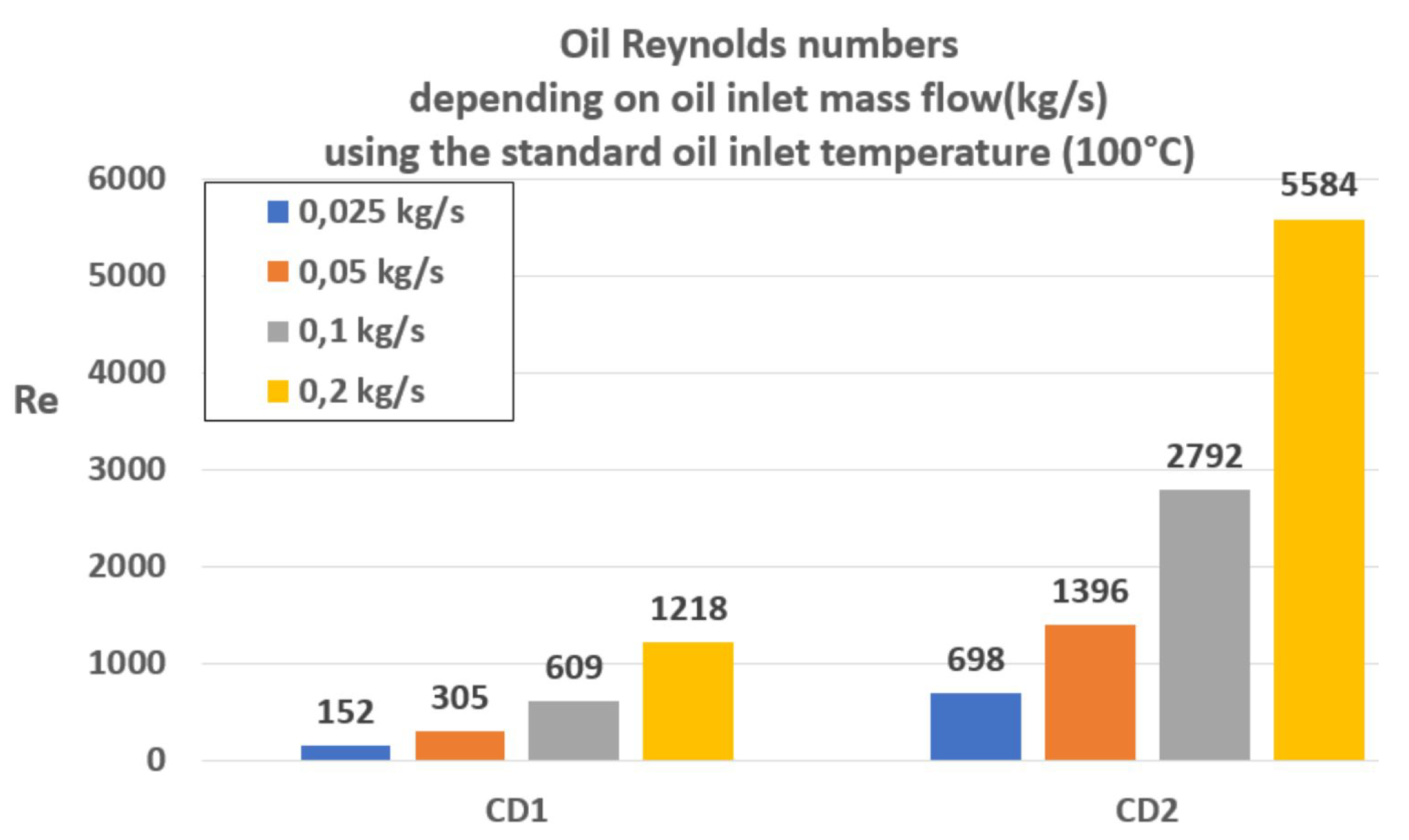

The last thermal resistance to be determined corresponds to the internal flow in the oil side,

. For that, a similar process, as by the external flow, is followed to assess

but with some differences. Within the oil internal cavity, the fluid is confined by the oil-metal interface appearing two regions: entrance region (hydrodynamic and thermal) and the full developed region. In this work only correlations for fully developed flows are employed to simplify the calculations following the recommendations of Incropera et al. [

25]. For laminar flows (

), like in CD1 with all mass flows and by CD2 with 0.025 and 0.05 kg/s, when

(in our case

at the inlet), or by turbulent flows outside of the entry length, defined as

, being

the hydraulic diameter, this is a reasonable assumption. Another difference with the air side methodology, in which the

is a constant, is that in the oil side an estimation of a mean temperature alongside the oil cavity,

, is needed to evaluate the material properties of the oil due to the variation of the oil temperature from the inlet to the outlet. In this work, and using a constant surface temperature condition, an arithmetic mean temperature approach has been used, obtaining a mean oil temperature of

C when supposed a oil outlet temperature of

C. Moreover the oil used for this assessment is a common jet engine oil MIL-L-23699 (5cSt). Now it is possible to evaluate

for the different mass flows, obtaining that only laminar flows are present by CD1,

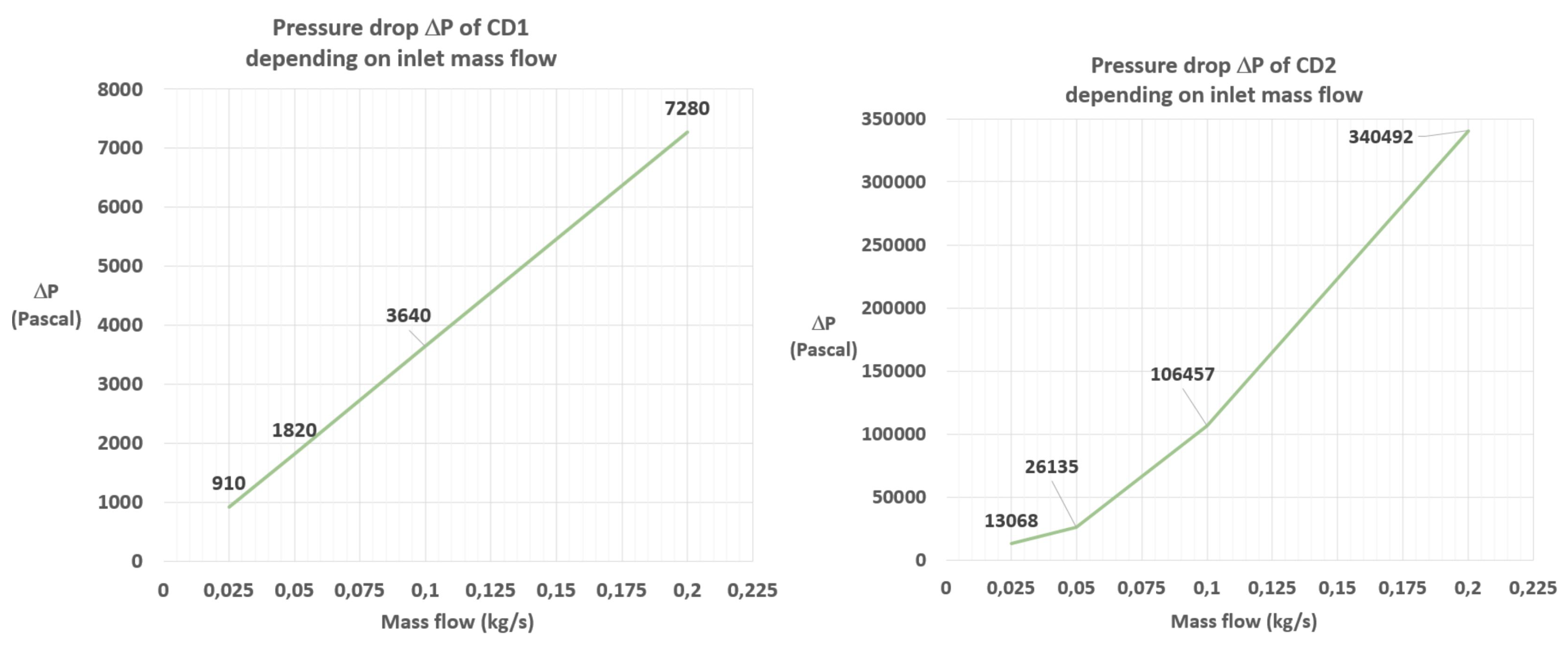

Figure 5. By CD2, turbulent flows appears clearly when the two highest mass flows are employed.

Table 4.

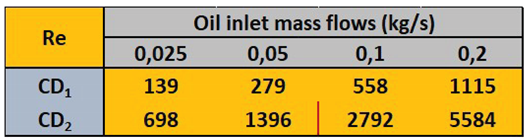

Oil Reynolds numbers corresponding to the analytical assessments using the arithmetic mean approach by CD1 and CD2.

Table 4.

Oil Reynolds numbers corresponding to the analytical assessments using the arithmetic mean approach by CD1 and CD2.

The values of the Nusselt numbers in laminar flows for pipes with circular cross section do not depend on the Reynolds numbers, being a constant, 3.66. By rectangular cross sections, the Nusselt number varies depending on the ratio

. Ratios higher as 8 are considered as ’infinite’ ratio corresponding to a constant Nusselt number of 7.54 [

25]. By turbulent flows, however, the Nusselt number are assessed using more complex correlations in which the roughness of the wetted surface and friction effect play an important role. In this work the correlation for smooth pipes is used and valid for the investigated range of Reynolds numbers, provided by Gnielinski [

25]:

where

is the Darcy friction factor [

28], which depends on the flow regime,

. For turbulent flows in smooth surfaces for circular pipes, in the range

, three correlations can be employed: the correlation of Konakov [

28]:

the Petukhov’s correlation [

25]:

the correlation included in [

28]:

or for a global range of

, based on the values of the laminar and Konakov’s correlations [

28]:

being defined

for

as:

In equation (

20) an additional factor,

, can be introduced [

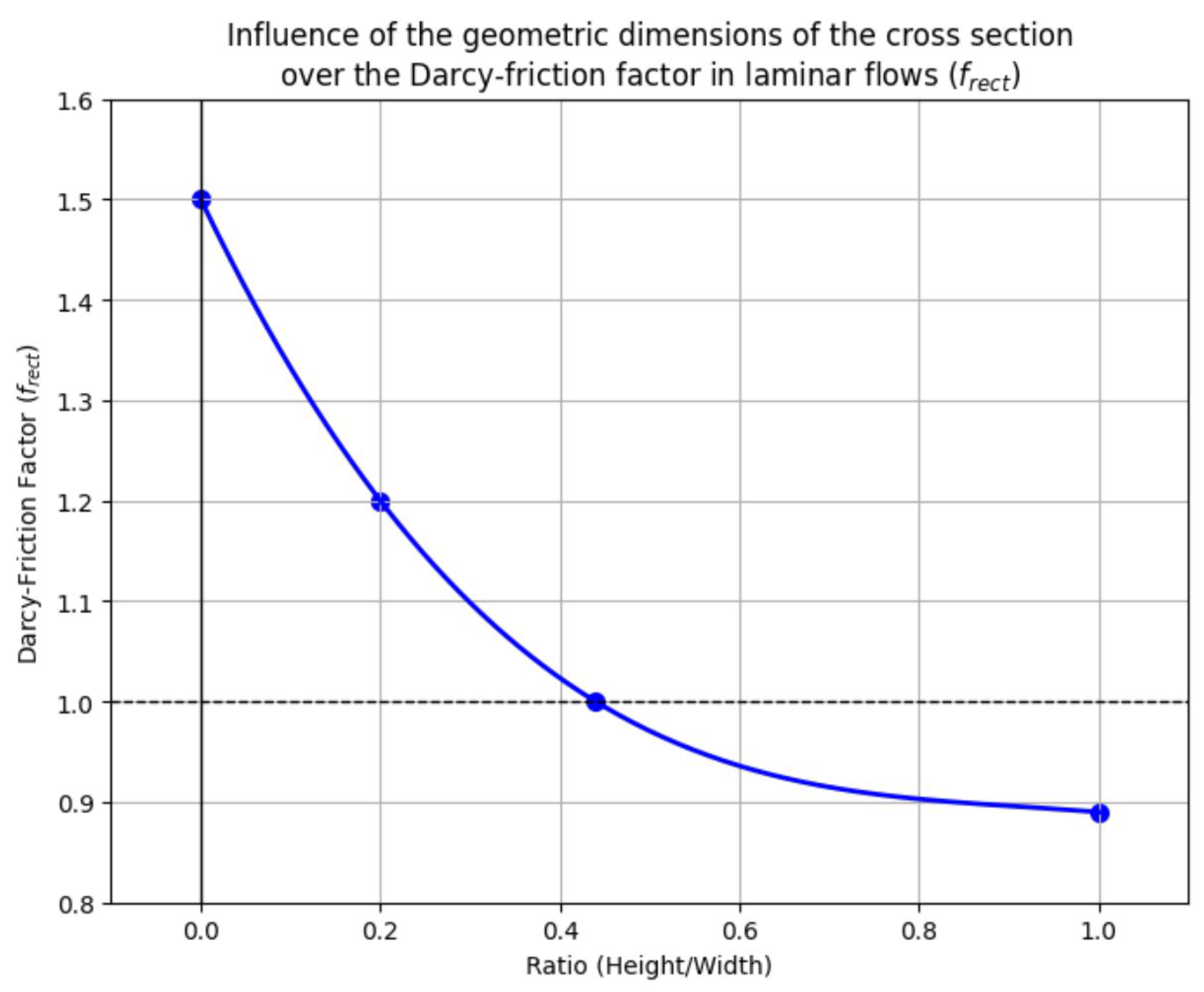

28] to take into account friction effects by rectangular cross sections like by CD1:

depends mainly on the ratio of the dimensions of the cross section (

) presenting a monotone decreasing behaviour, see

Figure 6. For square cross sections (ratio = 1), the

takes the lowest value, 0.89, provoking a reduction of the Darcy-factor of 11% in comparison with the circular cross section case. No impact of the geometric dimensions on the friction factor (

=1) takes place when the ratio is equal to 0.44.

By the CD1 geometry with a geometrical ratio of 0.0727, the factor

and the friction factor results 87.93. This value is lower as the proposed in [

25], 96, by using the expression for laminar and rectangular cross sections:

In the next chapter, a comparison of the friction factor values obtained in equations

21 and

22 is conducted by assessing the pressure drop to estimate any potential influence on the fluid variables. However, this does not consider the impact on heat transfer, as the friction factor is not accounted for in the equations governing laminar flow.

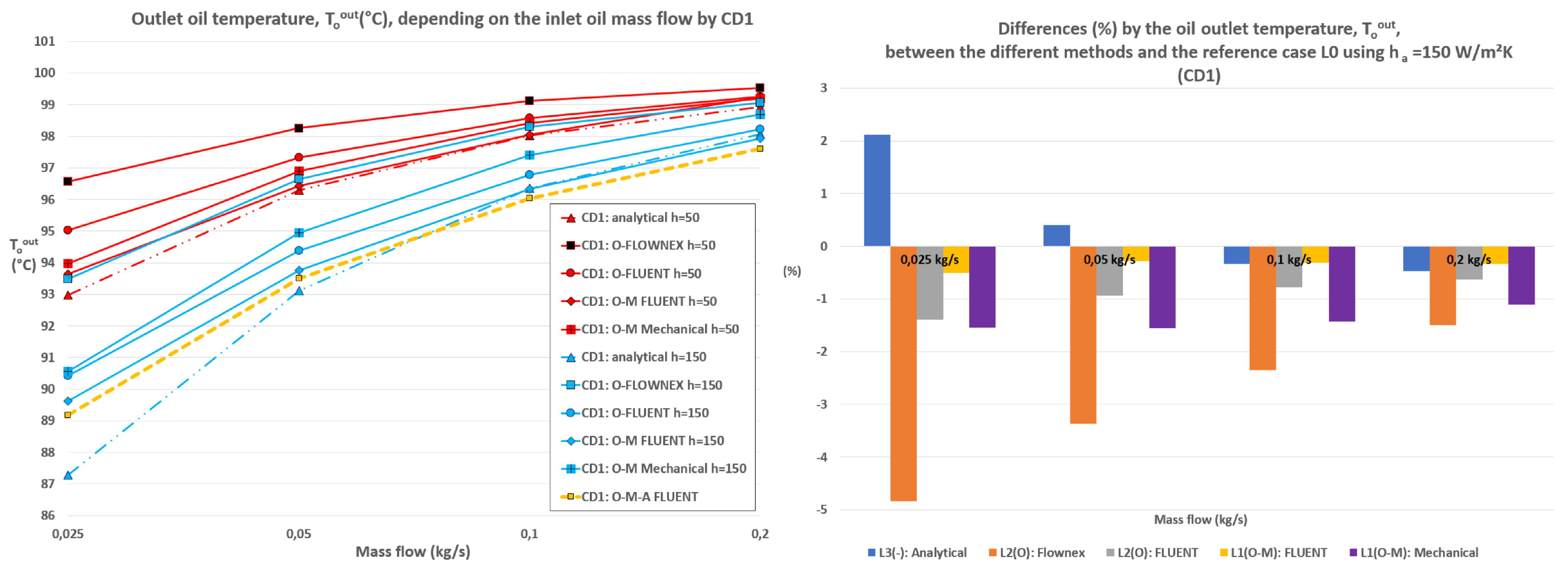

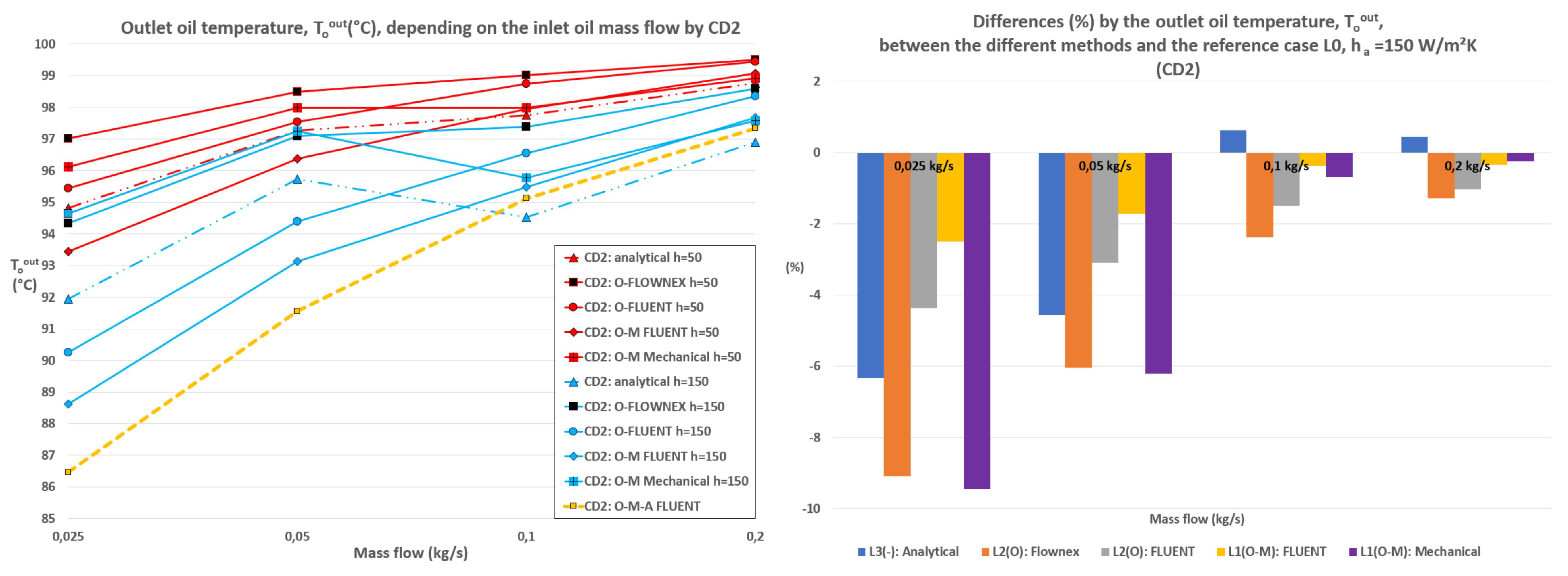

Finally, all needed ingredients are known to assess analytically the total dissipated heat in the FOGVC (equations

3 and

4) and the outlet temperature of the oil for the predetermined boundary conditions. The following figures summarize the most important results of the analytical calculations. In the

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 can be seen the results by fixing the air heat transfer coefficient

to the obtained value 73.2

. On the contrary, in the

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 the results show the influence of the air heat transfer coefficient in the range from 50 to 150

in the global thermal analysis.

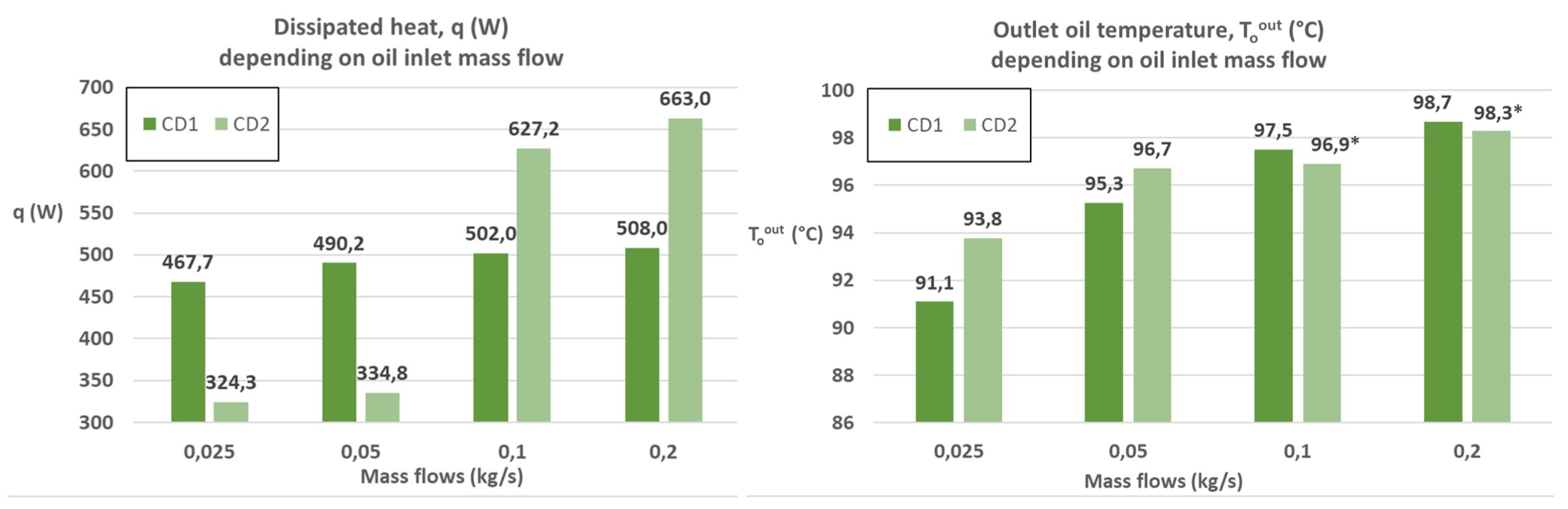

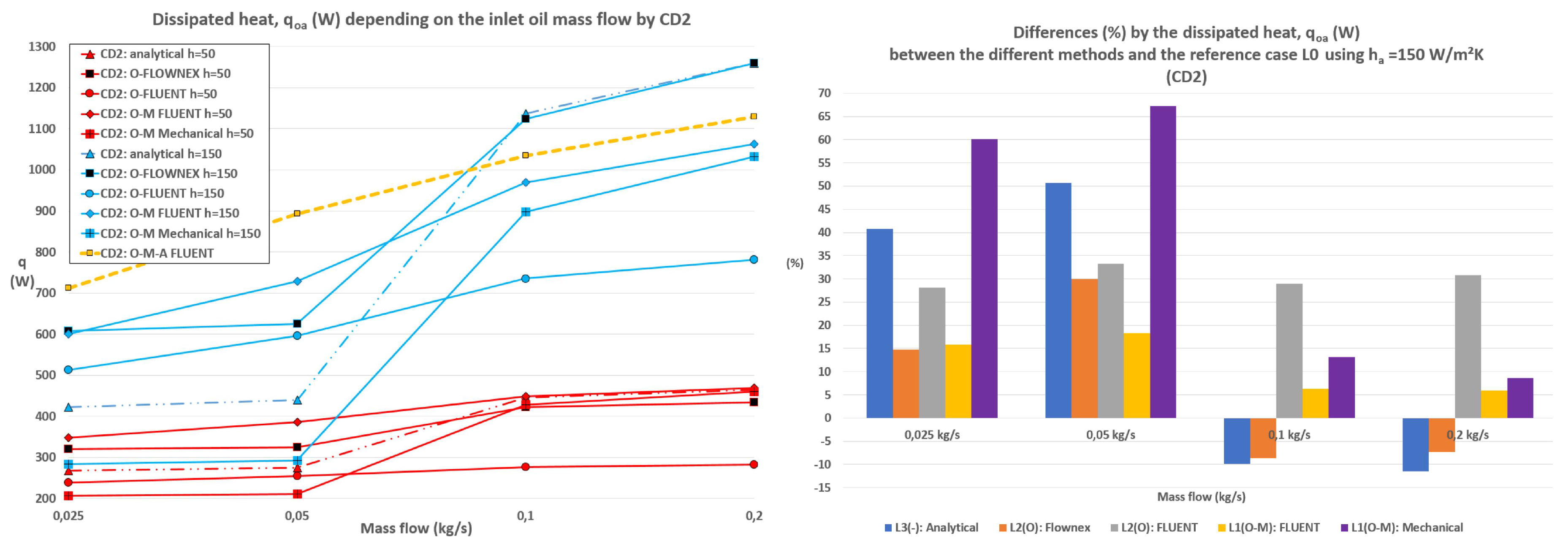

The

Figure 7, (left), shows the evolution and comparison of the dissipated heat depending on the oil inlet mass flow by CD1 and CD2. In CD1 the increment of the mass flow has a very low impact on the dissipation heat achieving a maximum improvement of only 40 W (from 467.7 to 508). By CD2, on the contrary, a clear improvement exists when the mass flow achieves the value 0.1 kg/s on which the laminar flow changes to transition one, obtaining maximum improvements of circa 105% (from 324.3 W to 663 W). The change of the behaviour between laminar and transition flows will be clearly shown in the following sections. The effect of mass flow increment on the outlet temperature can be seen in the right side of

Figure 7, provoking a lower reduction of temperature descend between inlet and outlet. Remarkable is that neither of the concept designs are able to reduce the inlet temperature beyond

C. In case that the lowest outlet temperature is the scope of the oil-to-air heat exchanger, CD1 fulfills this requirement, when the mass flows remain below 0.1 kg/s, hence, in laminar range.

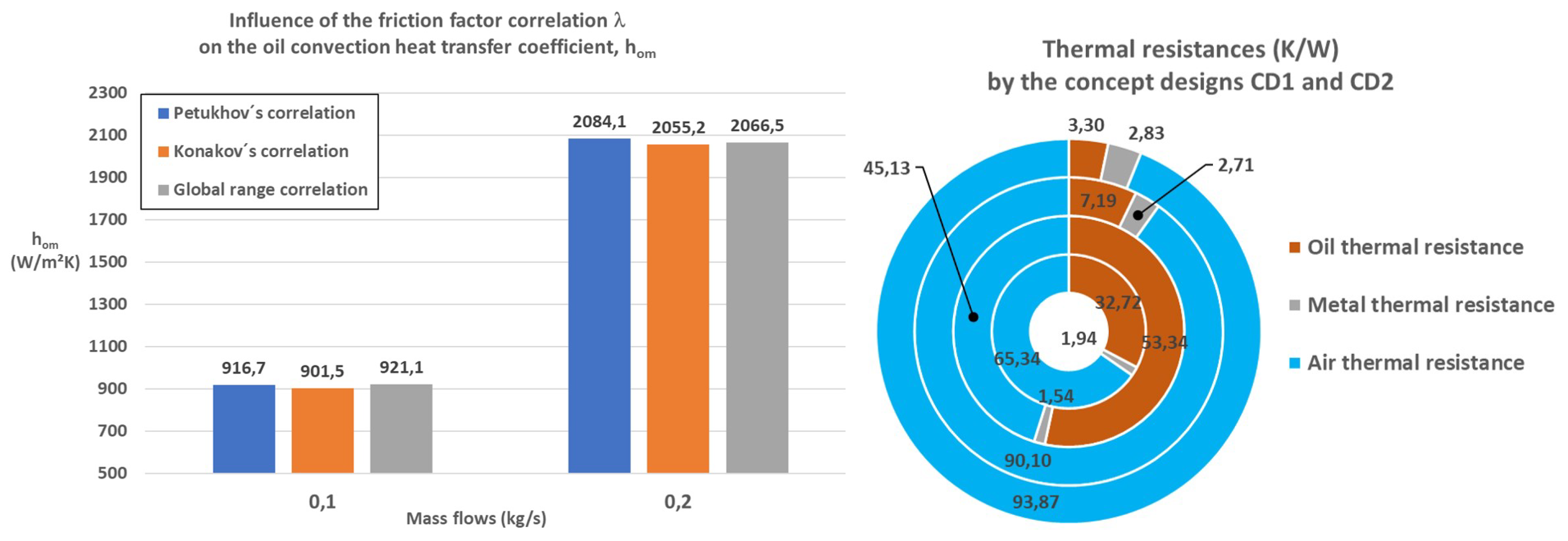

The influence of different friction factor correlations over the oil convection heat transfer coefficient and the Nusselt number by turbulent flows in CD2 can be seen in

Figure 8, (left). No significant differences (below 2% by

and

) have been obtained by comparing the three correlations (Petukhov, Konakov and global range correlation) using the highest mass flow. The Petukhov’s correlation is employed for the rest of the analytical calculations as the values provided by the other 2 correlations are more extreme.

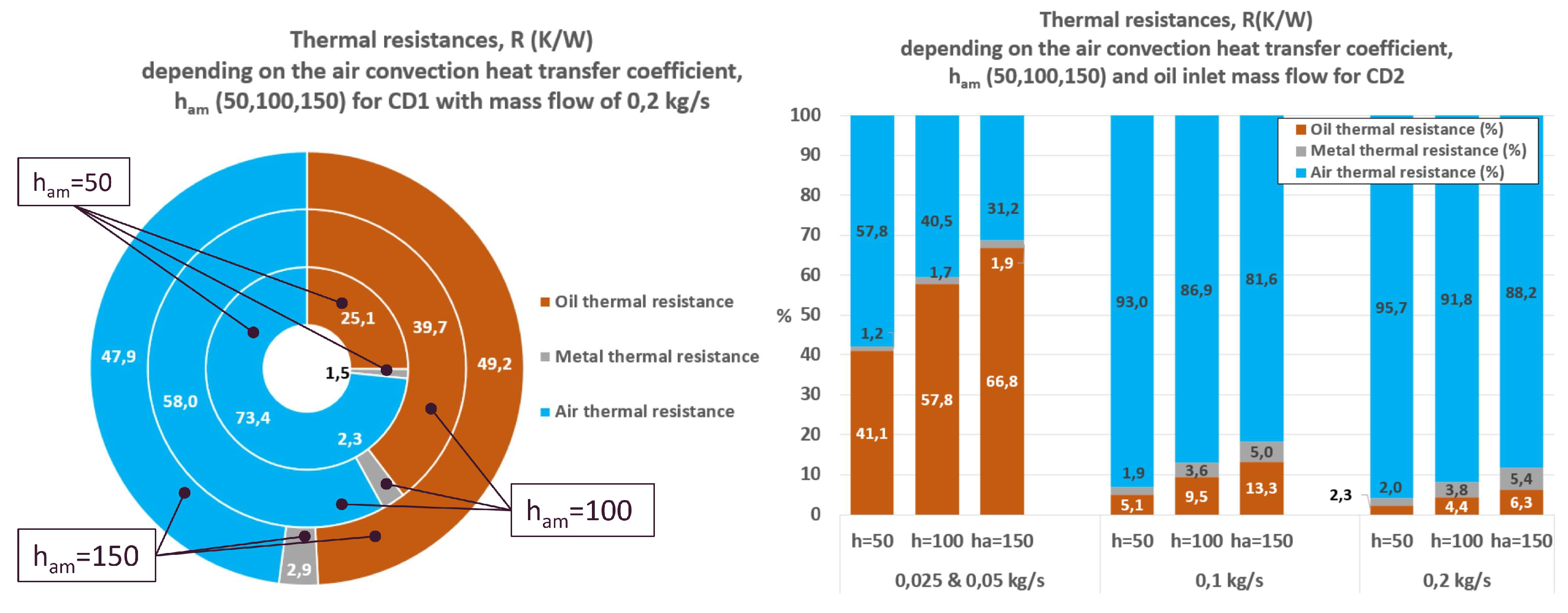

To optimize the thermal behaviour of the FOGVC, it is needed to know which side of the heat exchanger provokes a higher thermal resistance by the heat transmission. This information is presented by

Figure 8, (right).

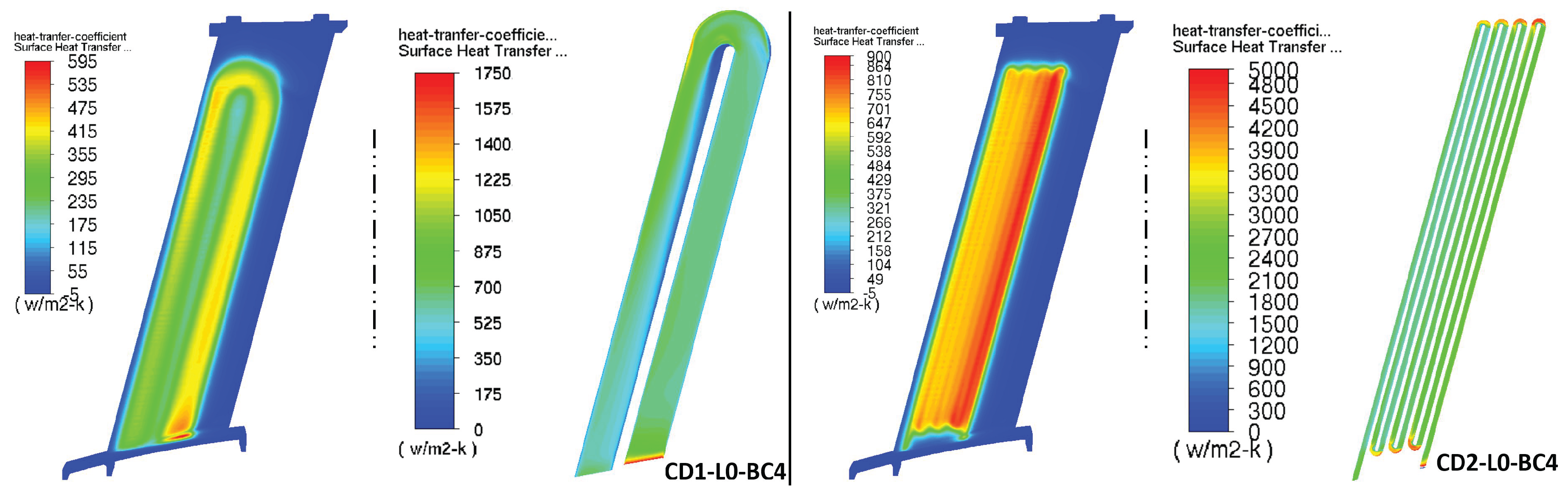

Using a constant heat transfer coefficient on the air side (

), the thermal resistances of CD1 are represented in the most inner ring of the graphic,

Figure 8 (left). Only 1 ring is needed by CD1 due to the laminar nature of the investigated flows. In this case with an air thermal resistance of 65.34%, the air side is restricting the heat dissipation coming from the oil side. Hence, the air side should be improve instead of the oil cavities, e.g by increasing the air velocity or the dissipation area, adding fins, etc.. In CD2 something similar is happening, but more extreme, by the most outer ring (0.2 kg/s) and the second more outer one (0.1 kg/s) with air thermal resistances over 90% (both transition flows in the oil side). The laminar cases of CD2 (0.025 and 0.05 kg/s), represented by the ring with values: oil= 53.34%, metal= 1.54%; air= 45.13%, is the only one in which the oil thermal resistance is higher than the air one but with values quite similar to the air side. A configuration with similar thermal resistances on both fluid sides is recommended to avoid bottlenecks by the heat dissipation. Regarding the conduction metal thermal resistances, all remain below 3% by both concept designs. The reduction of the metal resistance normally is related to structural issues, as to reduce this resistance it is needed to reduce the thickness of the oil-air wall and/or the increase of the thermal conductivity of the FOGVC material, which normally is not possible due to strength requirements.

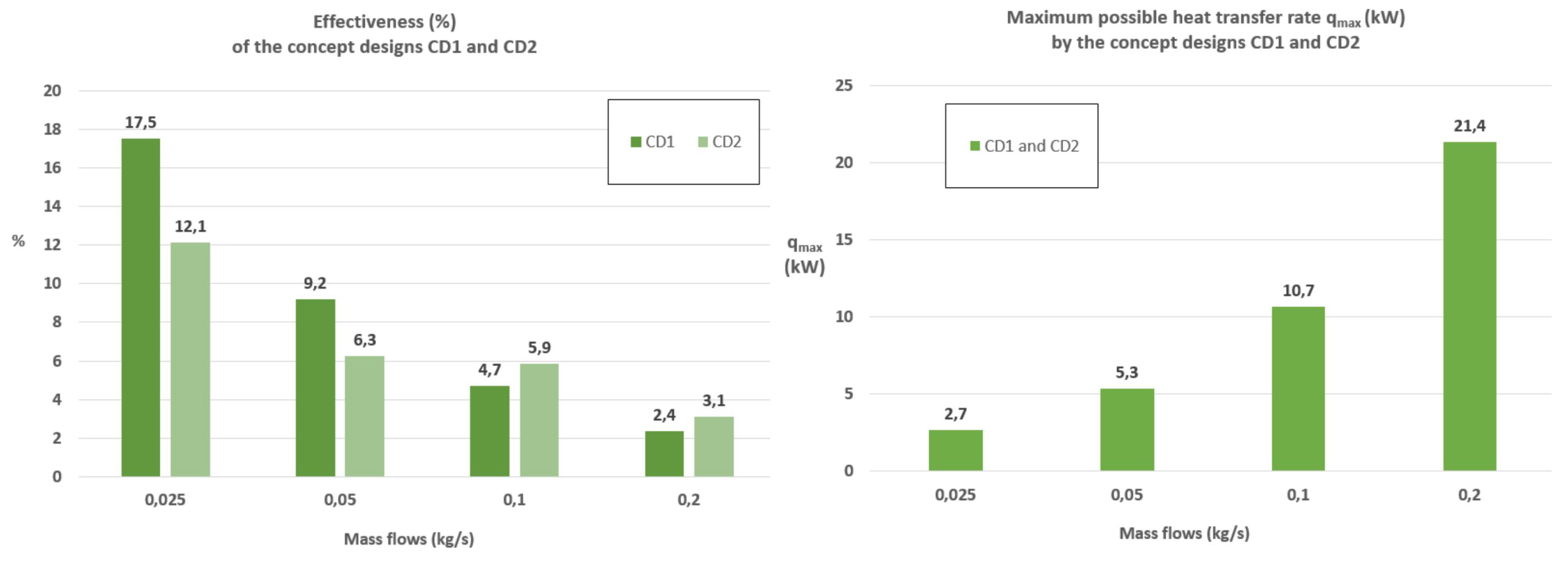

To know the dissipation potential of the FOGVC, the effectiveness,

, and the maximum possible heat transfer rate,

, defined in the NTU method can be used,

Figure 9.

Based only on the heat capacities and the inlet temperatures of both fluids in the FOGVC, the theoretically maximum possible heat transfer rate, independent of the employed concept design, increases linearly with the mass flow, obtaining a maximum value of 21.4 kW,

Figure 9 (right). If a heat exchanger is integrated in every FOGV, the theoretical total dissipation heat rate of the FOGVC assembly can achieve 856 kW (assuming 40 FOGVCs). Unfortunately the effectiveness of the FOGVC decreases with the increment of the mass flow and the type of design, as can be seen in the left graphic of the

Figure 9, obtaining the total heat transfer rate multiplying both variables, see left graphic of

Figure 7.

Until now a constant air heat transfer is employed. Now, the influence of the air heat transfer coefficient variation is investigated,

Figure 10.

Regarding the dissipated heat rate by CD1, a slight continuous increase takes place, when the oil mass flow is augmented. A higher impact has the increment of the air heat transfer coefficient (from 50 to 150 ), provoking maximum improvements of circa 95% at the boundary condition BC12. By CD2 the transition from laminar to transition flows has a huge impact on the heat dissipation causing increments between 62% () and 158% (), achieving maximum heat rates of 1.25 kW (BC12). A similar behaviour can be observed by both concept designs when the results of the oil outlet temperature are shown (increase of the outlet temperature when the inlet mass flows increases too). The only exception happens when the mass flow is 0.1 kg/s, dropping the temperature slightly and increasing again with 0.2 kg/s, probably due to transition effects. If achieving the lowest outlet temperature after the FOGVC is the goal, only the lowest mass flow rate can meet this requirement.

The last analytical investigation dealt with the weighting ratios between the thermal resistances when the air heat transfer coefficient is modified,

Figure 11. For CD1, the air thermal resistance predominates over the oil one by lower heat transfer coefficients, achieving a desired balance by

(air: 47.9%; oil: 49.2%), when an oil inlet mass flow rate of 0.2 kg/s is employed. In the last case, the presence of bottlenecks in the heat dissipation are minimized. This is not the case by CD2, in which a balance between the air and oil thermal resistance is not achieved neither in the laminar nor in transition flows, being the weighting ratios by the transition case, around 90-10% with oil mass flows of 0.1 and 0.2 kg/s, much more unbalance as by the laminar one, 40-60%, where oil mass flows vary between 0.025 and 0.05 kg/s.

Figure 11.

Influence of the air heat transfer coefficient on the dissipated heat rate with an oil inlet mass flow rate of 0.2 kg/s (inner ring: ) (left) and on the outlet oil temperature (right) for the concept designs CD1 and CD2.

Figure 11.

Influence of the air heat transfer coefficient on the dissipated heat rate with an oil inlet mass flow rate of 0.2 kg/s (inner ring: ) (left) and on the outlet oil temperature (right) for the concept designs CD1 and CD2.

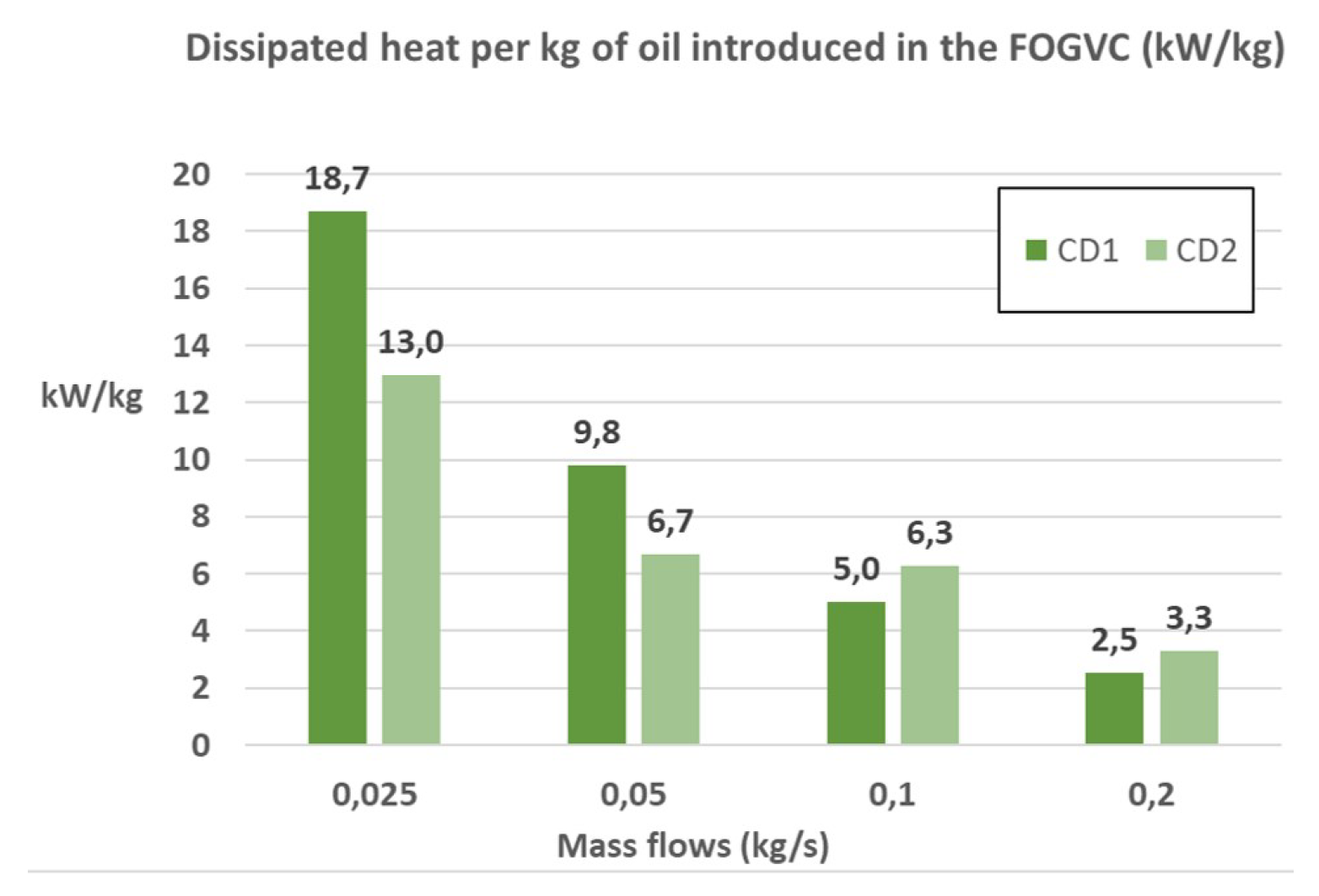

Figure 12.

Capacity of dissipation (kW/kg) depending on the inlet mass flow and the concept design.

Figure 12.

Capacity of dissipation (kW/kg) depending on the inlet mass flow and the concept design.