1. Introduction: What’s in a Name?

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet.” – the famous quote from William Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet (lines 43-44, Act-II, Scene-II) qualifies how the true worth of things outweighs the names per se by which the society may choose to call them. Inconsequential as it may appear on a cursory examination, the names which we use to refer to things, however, possess many covert, imperceptible, and hitherto unexplored implications. For instance, there is ample evidence to show that names can sometimes be given in accordance with the value and significance associated with things across all the cultures of the world. It is thus quite likely that the very premise of “name-giving” and the connotations behind names may possibly have an altogether substantial basis, beyond intangibility and insignificance.

To begin with the most obvious, getting a name can be verily regarded as the inception of a person’s biography, not just a symbol of the beginning of human existence but the onset of a life program. The naming of a child in this context is very much akin to legitimizing a new being by gifting him/her an identity, a means through which the world addresses him, and which in some measure, influences his life script to some degree. A name is a marker of a person’s individuality, and generally shapes one’s conceptions of oneself as well as the impressions others carry of them, during or before the first encounter. An individual, after he has become enough cognizant and conscious of the existence around him, repeats his own name several times to others, sometimes trying to explain its meaning for gaining better acceptability or simply by helping them pronounce it appropriately especially in a foreign land. It is also not uncommon for people to identify closely with people having similar names, and a unique camaraderie oftentimes stems from the shared glory of an identical name or names with similar meanings. In a group or a community setting, a sub-conscious comparison is inevitably drawn between people who share an identical name, signifying a tenuous credulity behind the association of name and assumed merit. More so, if the name of an individual resembles a past name of a stalwart, the society indiscreetly tends to gauge the person’s credentials at par with the personality of distinction, and the person may struggle to live up to the exalted expectations which his name has fortuitously brought upon him. In many of these scenarios, the individuals concerned grow with an increasing awareness of their names and the weight it carries. Hurlock (1985) discusses the consequences of a particular name on a child’s social development. She suggested that as the children expand their social circle and begin to venture outside their homes, it dawns upon them that their peers and adults treat their names as identity symbols, and thus their names can be a measure of their personal appeal or its lack thereof. She presented a comprehensive list of names that can produce negative psychological consequences. These names are typically so familiar and nondescript that their bearers are divested of any uniqueness, or so abstruse that a person becomes highly conspicuous, names that rob the gender identity, names so long that others are compelled to use shortened versions or diminutives which are unpleasant and demeaning. Similarly, prior research has shown that foreign-sounding names and symbolic names are also burdensome (James and Jongeward 1971).

Beyond psychological implications, the process of giving a name to a child can also be examined from other perspectives such as social, regional, cultural, and religious. A perfunctory examination may reveal that the parents tend to choose a child’s name in accordance with the passing fashion, their ephemeral infatuations or fascination with a character from cinema or theatre, or someone whom they bear admiration for. They may even choose names that are more trendy and fashionable and may not endorse names that are rooted in traditions. However, there are others who, although may consider most of the traditions as passe in their daily chores, still attach a lot of solemnity to the family traditions, especially when it comes to ceremonies such as marriage, the birth of a child or even naming of a child, particularly in the Hindu tradition. Thus, family traditions have a paramount role in the selection of a name for a child, and it is thus, not a mere coincidence that religions across the world give this event a sound consideration. According to James and Jongeward (1971), many children are given symbolic names from literature, family genealogy, or history and it is anticipated that the child may stand up to the desired qualities and character. This preliminary analysis here may suffice to show that names have a noteworthy psychological bearing upon the individuals as well as the society, and hence the science and the art behind the naming of children, with a focus on the family and the society of child’s birth, is a topic worthy of research and analysis. The current manuscript focuses on one such aspect of name-giving – of what we label as ‘mathematical names’, something that we discover to be a pervasive feature of the current Indian Hindu society.

2. Importance of Name-Giving with Reference to the Indian Tradition

While selecting the first name of a newly-born child, the parents want it to sound nice, unique, and authentic whereas the second name is usually the same as the family name. Jagieła and Gębuś (2015) report that interviews of students conducted by them revealed a clear interrelationship between the names and different facets of life script. A similar opinion had been expressed by Eric Berne (1972) when he asserts that given names, short names, and nicknames, or whatever that is bestowed on an innocent baby, is a clear marker of where his parents want him to go. Much before a name can evoke any meaningful fervor from a grown-up child when he begins to identify with his labeled identity, the names are, in good measure, a reflection of the parents’ aspirations, beliefs, intentions, and even social position (Doroszkiewicz 2005). Prior research establishes the fact that parents bestow a name to their children after careful consideration and expectations, for which they assume responsibility, but which can also impose certain restraints and anticipations upon them regarding their future course (Jagieła and Gębuś 2015). In any case, the complex and peculiar repercussions of a name on its carrier is abundantly clear from the prior research. According to Christenfield and Larsen (2008), ‘‘Names seem far more than arbitrary labels useful for telling one’s children apart, or alerting friends to falling safes and other imminent dangers. They seem instead to capture and shape the individuals’’. Be that as it may, the name-givers of a child are their gene-givers as well, and their value systems have an indispensable role not only in the naming of a child but also in his upbringing and the value systems he imbibes during such a phase. Thus, the impact of names on individuals can’t be singularly extricated and explored, since names are not randomly assigned labels, but are intricately related to the consciousness and belief systems of the parents. However, research does indicate that the names matter sufficiently to captivate a sufficient amount of care and attention from the parents (Christenfield and Larsen 2008).

Loferska (2011) asserts that this observance is not a unique moment in the life of a child alone but the entire family as well. It is a moment for the entire family to reflect on the unique identity they want to bestow on the child - a singularly important thing that the child has to invariably carry throughout life. This special moment engages the entire family since there often exists differing opinions on this vital issue of names – the superiors clinging to the names they have cherished in their fond memories, whereas the youngsters proposing funky, and even outrageous alternatives. Overall, the names chosen are those that epitomize anticipations and aspirations of the parents – what they want the child to become, to whom and what they are connected, and also what they want to preserve for posterity (Jagieła and Gębuś 2015). It is not surprising then, that the name-giving event for a newborn comes with a ceremonial commemoration since it represents a special moment in time at the onset of a child’s life.

The Hindu name-giving ceremony of a child, also referred to as ‘Naamkaran’ (Sanskrit Naam = ‘Name’; karan = ‘Create’) is considered to be one of the most important of the sixteen ceremonies in the passage of one’s life. Ideally, the ceremony is performed eleven days after the birth of the child, although sometimes variations are possible based on the advice of the family priest or an astrologer. The traditional function is held at home or a temple, with worship and a fire sacrifice wherein auspicious hymns are recited and prayers are offered for the well-being of the child and his good health, long and prosperous life in the future. In a typical Hindu rite, rice grains are strewn on a bronze dish and the father writes the chosen name using a gold stick while chanting God’s name. This is followed by whispering the selected name into the child’s right ear, repeating it four times along with a prayer. This is followed by incantations are recitations headed by the priest, as a marker of formal acceptance of the child’s name. Hindu belief holds that the name of the child has a profound bearing on the character and the destiny of the newborn, and thus the name has to be in accordance with the principles of Vedic astrology, for it to have an auspicious effect. According to the Hindu tradition, the initial letter of a child’s name is extremely important is chosen based on the nakshatra, or the star under which the child is born, the moon sign, the planetary positions at the moment of child’s birth, the child’s zodiac sign or the Deity who presides over the month of birth. Having selected an initial letter, few propitious names are suggested by the priest or astrologer, which is deliberated upon by the family members, and a suitable name is selected. Although minor variations in these traditions are not surprising in a highly heterogeneous Hindu society, two common principles can be delineated as it relates to their tradition of name-giving: first, the consciousness of the parents, family, and the larger society does have an instrumental role in this process. Second, the name-giving per se is hardly a random event ever, but a well-structured and organized one, where an individual or a group or individuals reflect inward, groping for deeper identities of the child or their own selves and at times even confer sound astrological principles, to arrive at the suitable name of a child.

In the already set-up context of the naming of Hindu children in India, however, there is an intriguing observation that can be made. Our research indicates that there is a significant number of names that are directly derived from mathematical concepts and terminologies. These names broadly termed here as ‘mathematical names’ stem from different branches of mathematics such as geometry, trigonometry, algebra, arithmetic, number system, probability, statistics, etc. Apart from the names corresponding to different mathematical concepts, people are also named as per the terminologies pertaining to the development of mathematics in the Vedic/Indian tradition, the names of the mathematicians, or after the names of their compendiums. However, to fully understand this phenomenon, it is important first to take a stock of such names that belong to different areas of mathematics, try to understand its genesis and mathematical roots, and examine the reasons behind such a phenomenon, particularly with reference to the prior literature on name-giving and its psychological and sociological perspectives. To fully understand the genealogy of such names and the possible underlying reasons behind it, it is worth taking a brief look at the mathematical traditions of India, so as to assess its impact on the overall consciousness of the populace.

3. A Glimpse into the Rich Mathematical Traditions of India

India has a glorious history of mathematical traditions from the early Vedic period itself and the developments in the areas of numbers, arithmetic, algebra, geometry, trigonometry, probability, prosody, astronomy, etc. can be easily gauged from the early mathematical texts available, archaeological evidence such as the bricks from Harappan findings and other exemplars of early Indian mathematics such as the Bakhshali manuscript. The pervasiveness of the mathematical principles in the commonplace of Indian social fabric, and its recognition can be ascertained from an appreciation of mathematics, as penned down by Mahavira (850 CE), one of the celebrated mathematicians of his time:

“In all transactions which relate to worldly, Vedic or other similar religious affairs, calculation is of use. In the science of love, in the science of wealth, in music and in drama, in the art of cooking, medicine, in architecture, in prosody, in poetics and poetry, in logic and grammar and such other things, and in relation to all that constitutes the peculiar value of the arts, the science of calculation (gaṇita) is held in high esteem.

In relation to the movements of the sun and other heavenly bodies, in connection with eclipses and conjunction of planets, and in connection with the tripraśna (direction, position, and time) and the course of the moon – indeed in all these it is utilized.

The number, the diameter, and the perimeter of islands, oceans, and mountains; the extensive dimension of the rows of habitations of the world, of the interspace between the worlds, of the world of light, of the world of gods and of the dwellers in hell, and other miscellaneous measurements of all sorts – all these are made out by the help of gaṇita.

The configuration of living beings therein, the length of their lives, their eight attributes, and other similar things; their progress and other such things, their staying together, etc. – all these are dependent upon gaṇita (for their due comprehension). What is the good of saying much? Whatever there is in all the three worlds, which are possessed of moving and non-moving beings, cannot exist as apart from gaṇita (measurement and calculation).” (Rangacharya 1912)

The dissemination of mathematics in the social psyche and recognition of its importance was carried out by the works and treatises of many stalwart mathematicians and astronomers who made notable contributions to the field of mathematics, astronomy, and many other related branches of knowledge.

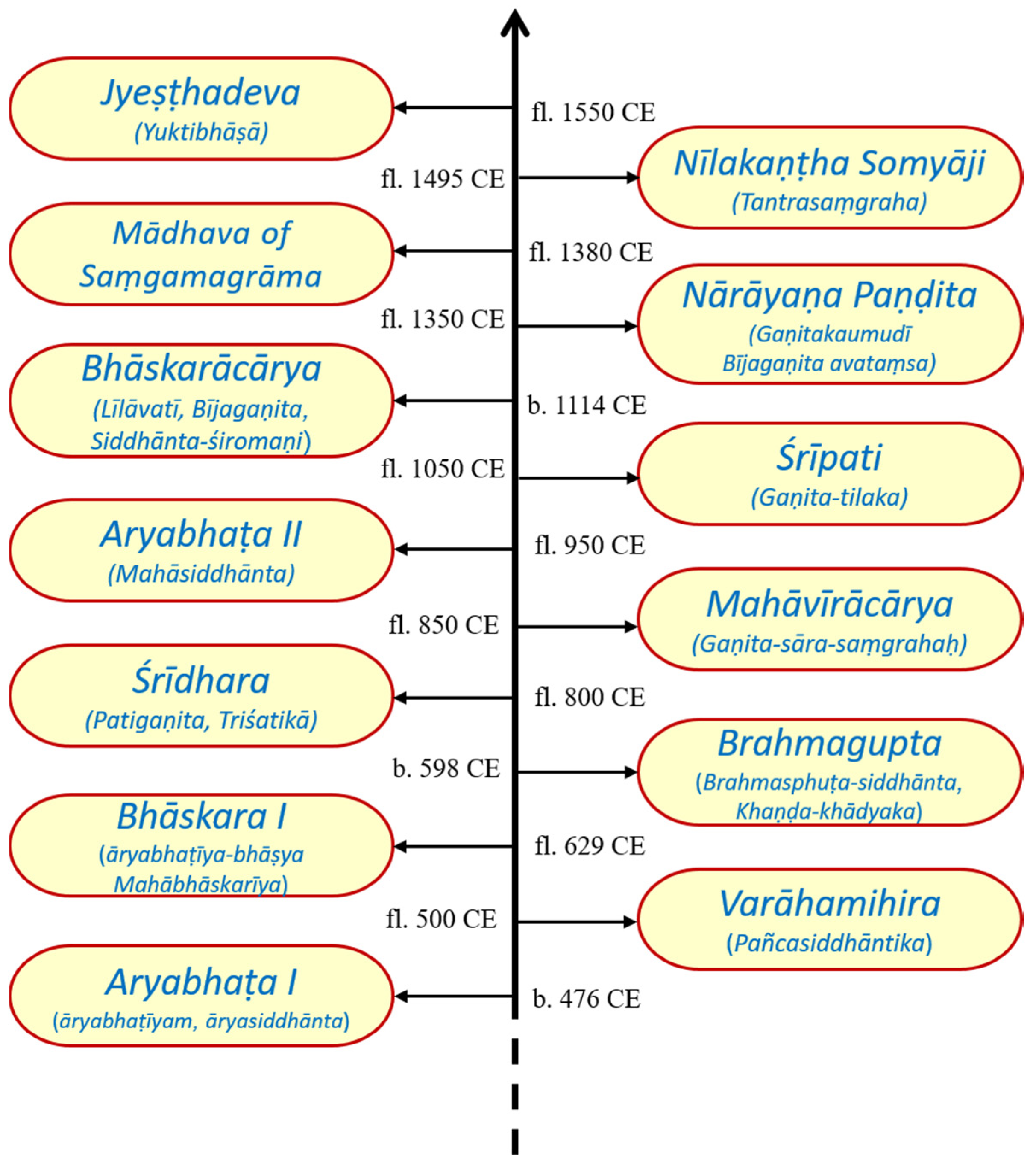

Figure 1 shows a chronological depiction of several mathematician-astronomers from India along with their treatises. Put simply, some of the notable contributions of these mathematicians include the expression of very large numbers by indices of ten, the use of fractions, the concept of nine numerals, and the decimal place-value with the introduction of zero, which was a significant contribution to the development of arithmetic. An efficient and direct methodology of fundamental mathematical operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, square, cube, square roots, cube roots, etc., and the rule of three (

trairaśika) method of calculation also owes its genesis to the Indian soil. A detailed exposition on the properties of zero and infinity, as well as accurate results for surds, have been given by Indian mathematicians. As regards algebra, particular details on symbols of operation, equations, linear and quadratic equations, indeterminate equations of the first and second degree, progressive series, permutation and combination, and the binomial theorem (Bag 1979).

The intricate knowledge of ancient Indians pertaining to altar constructions has been described in the śulbasūtra by Baudhāyana and Apastamba. In this age of śulba geometry (~600 B.C.) a statement on the so-called Pythagoras theorem appears, determination of the value of √2 by the geometrical method has been described along with the classification of geometrical figures on the basis of angles and sides. Brahmagupta’s lemmas and his methods for the construction of a cyclic quadrilateral or diagonals of a cyclic quadrilateral are some remarkable achievements of geometry. Aryabhata, a mathematician, and an astronomer made several important contributions including the calculation of the area of a triangle, as early as 476 AD. Combinatorics formed an integral part of Indian mathematics and the tradition commenced with the formal theory of Sanskrit prosody as propounded by Piṅgala in 2nd century BC (Shah 1991). Halāyudha, a mathematician and commentator on chandaśāstra of Piṅgala presents a comprehensive interpretation of meru-prastāra scheme, which has also been proposed as Pascal’s triangle in the European world. The knowledge of trigonometry in India can be gauged from the trigonometrical formulae, sine tables, value of ℼ, and the fact that the trigonometrical series such as ℼ, sine, cosine, and tan was first outlined more than a century before Newton (1664 AD) and Leibniz (1676 AD). Similarly, advances in infinitesimal (integral) calculus were reported in Yuktibhāṣā in connection with the summation of infinite series, a century before Newton and Leibniz. Bhaskara II (1150 AD) from the Kerala school of mathematics, reported the concepts of both differential and integral calculus (Bag 1979).

Given this rich tradition, the question we ask is as follows: How did this rich mathematical tradition and lineage impact the society at large? How did the non-mathematical society at large view these mathematical developments and imbibe them? According to Datta and Singh (1935, p. 150), since the knowledge of higher mathematics could not be turned to material gain, there are very few who seriously undertook its study, although the religious practices of the Hindus necessitated a certain knowledge of mathematics and astronomy, It is clear that in the Indian context, mathematicians and their contributions were venerated and the society readily imbibed all that it could, from them – be it their concepts and terminologies, their names or the names of their compendiums. All these got absorbed into the social consciousness. The extant remains of such a deep veneration for a scientific and mathematical (not necessarily empirical) culture can be gauged to date, by a subtle examination of the concurrent names of the Hindu Indian society. Needless to say, many of these names can even be found in other neighboring countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Korea, Bangladesh, and Japan.

4. Research Methodology

To explore the existence of the mathematical names in present India, three directories of names were utilized. The first directory was created by compiling names of enrolled students from higher educational institutions (HEI database) in India for the last eight years (2013-2020), amounting to a total of more than 28,650 names. It is worth pointing out that the names database was deliberately created from recent years, so that the names collected could be a reflection of the ethos of the current populace of the Indian society. In addition to the HEI database, Facebook (FB) and LinkedIn (LI) databases were also utilized. Our research can be distinctly categorized into qualitative and quantitative categories.

4.1. The Qualitative Approach to Analysis

Towards the qualitative analysis, a detailed study of several Indian texts in all aspects of mathematics (categorized into geometry, trigonometry, numeration, arithmetic, algebra, and mathematics in the Vedic tradition (beginning with the śulbasūtras) is conducted including not only the ancient and medieval texts in mathematics but also the modern mathematics textbooks prescribed in the existing school curriculum. The concepts and terminologies discovered from the extensive mathematical research are then juxtaposed and searched for, in the directories of names and one typical example is chosen for illustration for both genders. Facebook users directory (FB database) which consists of approximately two billion users in its database, as of 2021, is referred to search and substantiate the existence of such mathematical names in India. Further, to avoid dubious names, only factual names with surnames are manually selected and with the help of the location as a marker, only the names corresponding to the Indian subcontinent are filtered out, since the current paper focuses on the extant mathematical names primarily in this geographical region. To ensure verifiability of the data presented in this manuscript, we present some representative textual pieces of evidence behind the mathematical names as well as sample names that any reader can easily verify by any available search engine on the web, or directly by Facebook directory search. For the sake of brevity, textual evidence is kept to a bare minimum in this manuscript.

4.2. A Description of the Quantitative Approach of Data Extraction and Processing

In order to quantify the occurrences of such mathematical names, a more formal database of professionals such as LinkedIn (LI database) is utilized. However, to reduce the time requirements as well as to minimize the manual errors, the process of quantification of the recurrence of names is automated. Selenium web scrapper is employed to extract the list of names from LinkedIn. A step-by-step process of the extraction algorithm is described as follows: A spreadsheet of the list of mathematical terms (names) is created and pandas library is used to read the data in Python. Chrome web driver is used to route to the specific LinkedIn page, where HTML tags for the input fields are located and the credentials are entered for sign-in. Upon successful login, the homepage of LinkedIn is navigated and HTML tags for the search input are located, the names are input, and the ‘People’ option is selected to narrow down the results. Finally, the text string containing the number of people is extracted corresponding to each term. Pandas is then utilized to store the numeric result corresponding to each term. Overall, the data extraction process with Selenium was found to be a very time-efficient one. Moreover, thorough testing of the efficacy and accuracy of this algorithm is carried out and the above-described computational process yielded repeatable results for all the terminologies tested. To ensure the correctness of the collected data, an alternative manual procedure was utilized on the FB database and the proximity of the obtained results from both the databases validates the data recorded.

Thereafter, a systematic investigation and analysis of the data from both the HEI dataset and LI dataset is taken up, using MATLAB software. A MATLAB script is applied to the HEI dataset to extract forty-eight (mathematical or non-mathematical) names occurring with the highest frequency. Again, extraction using Selenium provided for an estimate of the numbers corresponding to the most frequent names in India. An average of these forty-eight numbers provides for a number that can be used for normalization of the number of occurrences of mathematical names to yield a ‘Name recurrence factor’. Name recurrence factor is a normalized quantity that indicates the relative occurrence of the mathematical names vis-à-vis the “most ubiquitous” name in a particular dataset and thus helps us to evaluate the effective prevalence of these names. This factor in combination with the absolute number counts corresponding to each name provides for a sound basis for comparison amongst these mathematical names. Finally, a survey has been conducted of persons who possess these mathematical names and their detailed responses have been solicited. Apart from the general prevalence of such names, we also intend to explore how the bearers of mathematical names feel about their names (at least when they are made aware of it), what led to their mathematical naming, any possible interlinks between such mathematical names and the tradition and great regard of mathematics in their families, or even the impact that such a name had on their own aptitude towards mathematics in general.

4.3. The Average Frequency of the “Most Ubiquitous” Indian Name

Admittedly, the task of estimating the average frequency of the most ubiquitous Indian name is a convoluted one, compounded by the dearth of readily available census data as of 2020. While even identifying such a “most ubiquitous” name in a multicultural and multilingual Indian society would be an onerous task, much less be said of the difficulties that beset its quantification. In fact, India has had a multilingual culture since ancient times and marked variations in both spoken and written languages have existed (Joseph 2010). Things are further muddled by the interrelationships between these cultural, linguistic, and religious aspects – and by the fact that owing to such cross-interactions, identical words, cognates or similar-sounding syllables appear in different languages, sometimes with a common root from Sanskrit or Persian. However, these difficulties can somewhat be reconciled if some commonly available databases could be utilized to gain some insight.

In our study, we circumvent these difficulties by a two-step process before we arrive at any conclusive estimate. First, a considerably large HEI dataset is utilized to deduce a list of the forty-eight most common names of students enrolled in India’s higher educational institutions. In the next step, LinkedIn database of users is employed to get the occurrence frequency of the names in this list. This is followed by an averaging of the five largest entries in the list to yield the highest frequency name.While this may not appear most scientific to arrive at an “exact” count, it is not inappropriate to use it as a normalizing factor against the count corresponding to the names derived from the same LI dataset. In such a scenario, just denotes the relative occurrence of a mathematical name, vis-à-vis one of the “most ubiquitous” names in the LI dataset. It is not wrong, however, to talk of values greater than unity, unlike the efficiency measurements in engineering calculations. It is indeed possible that a “mathematical name” may have values greater than unity. Moreover, there is a caution that needs to be exercised before one interprets these values. The underlying assumption here is that our HEI dataset and LI dataset provide a true representation of the existing names in India. However, there is no concrete evidence to posit this assumption. On the contrary, it is expected that both our HEI and LI datasets are a more accurate reflection of the urban India and not the rural. It is more likely then, that rural India, which expectedly carries a stronger impression of the cultural and religious foothold, essentially transmitted a greater amount of these mathematical names in the social consciousness through the course of time. This difference is further underscored by the fact that English being a foreign language in India, carries with it the dialectical impressions of different regional languages of India when regional names deriving from the Sanskrit root are transliterated into it. For instance, the name “mandal” which connotes a circle, becomes ‘mondal’ or ‘mondol’ in Bengal and Bengali-speaking regions. Under the given circumstances, it is implicit that the values presented here merely denotes the lower bound of the actual recurrence of these names.

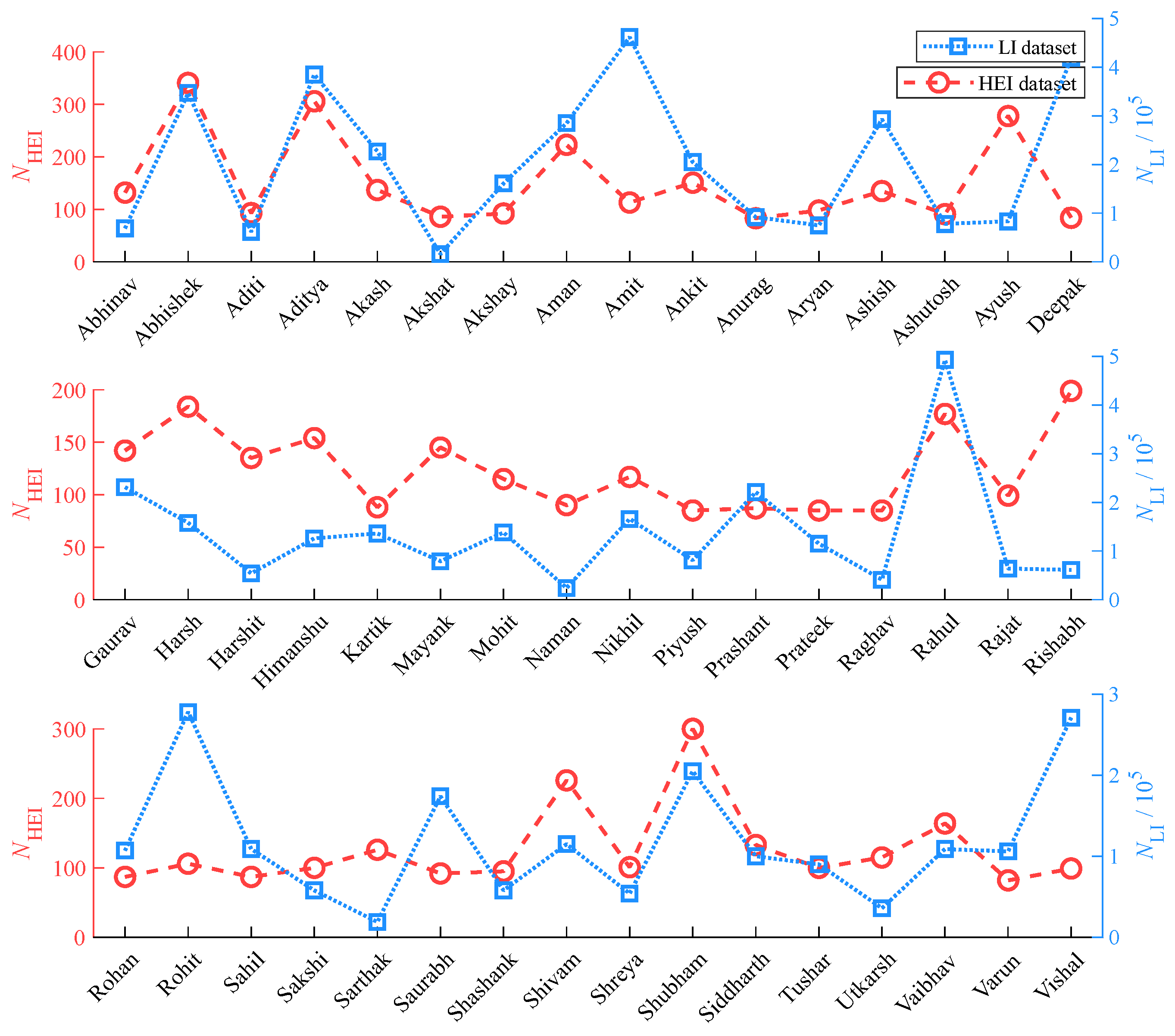

Figure 2 presents an exact count of the most ubiquitous names from the HEI dataset in alphabetical order. Out of the 28658 names in the HEI dataset, automated extraction of the forty-eight highest frequency names are done and it can be observed that the frequency varies between 82 and 341, or a recurrence fraction of 0.00286 to 0.0118. The name with the highest occurrence frequency is ‘Abhishek’ followed by ‘Aditya’, ‘Shubham’, ‘Ayush’ and ‘Shivam’, with a corresponding count of 306, 300, 278, and 226 respectively. These names are indeed one of the most common names around, as is also shown by the corresponding numbers of the LI dataset (

NLI). Interestingly, the LI dataset and HEI dataset show the exact same trend of number count for some of the high-frequency names, which include these five. The trends for other names between the two datasets are not coterminous. As shown in the figure,

NLI/10

5 values for these names are 4.93, 4.62, 4.19, 3.85, and 3.47 respectively yielding an average value of 4.212. Hence, for the sake of computation of

, the average frequency of the most ubiquitous name in the LI dataset is taken to be 421200.

5. The Genealogy and Prevalence of the Mathematical Names in India: A Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

In order to better understand the genealogy and the prevalence of ‘mathematical names’ in India, six distinct categories have been created, namely Geometry, Trigonometry, Number system, Arithmetic, Algebra, and Mathematics in the Vedic/Indian tradition and their name recurrence factors are designated by , and respectively. Of these, the last category is in fact a miscellany of not just the evolution of mathematics in the Vedic period, but also some unique terms that got introduced and absorbed in the Indian tradition of mathematics. In the sections that follow, we produce a running text on these distinct sub-categories as it pertains to mathematics in the Indian tradition, with the underpinning ‘mathematical terms’ being underlined, when every term appears for the first time in the text. Later, all these names are collated in a tabular format with an example of a name corresponding to both genders, and a quantitative analysis then follows.

5.1. Geometry

The description on the geometry may begin with emptiness (

rikt) and next a point (

bindu), which, in Euclidean geometry is an exclusively primitive concept upon which the foundation of geometry is built, and which has been treated only by axioms (Gerla 1995). When two such “invisible points” are concerned, as per the second postulate of Birkhoff’s metric geometry, there exists one and only one such unique line that connects them (Birkhoff 1932). In the Indian tradition of geometry, a line has been referred to as ‘

rekha’, which connects two fixed points and thus has a finite length (

vistara). However, if one of the points i.e., the vertex (

sheersh) is fixed, whereas the other can hypothetically lie at infinity, a ray (‘

kiran’) results, possibly bearing an allusion to the rays of the sun that extend infinitely into deep space. It is possible that the two rays can touch at a common endpoint and in such a case, an angle (‘

kon’) results. These angles could be of different magnitudes. It could be a straight angle (

riju), acute angle, right angle or an obtuse angle (

adhik kona). The word angle owes its genesis to its Latin equivalent

angulus meaning “corner” (equivalent to Sanskrit

“kon”) and its linguistic cognates such as

ankylos in Greek, meaning “curved” and the English word “ankle”. Both the Greek and English cognates are linked to the Proto-Indo-European root

“ank”, meaning a “bow” (Slocum 2007). Interestingly, the Sanskrit equivalent for a bow is “

dhanu” or “

chaap”, which is used to refer to an arc in Hindu geometry. The measure of the ratio of the length of a circular arc to its radius is the estimate of an angle, which is described to a considerable level of accuracy in Hindu geometry. For instance, Surya-siddhanta (Gangooly and Burgess 1997) gives the angle measurements in text 128 as –

Sixty vikalas make up a kalaaand sixty kalaas comprise a bhaag. Thirty of such bhaag constitute a rashi, and a spherical revolution, bhagana consists of twelve such rashis.

It is worth noting that the current system of measurement of angles is precisely similar to that mentioned in Surya-Siddhanta, where a minute consists of sixty seconds, a degree consists of sixty minutes, and 30 x 12 = 360 such degrees make up a revolution. A degree in Hindu geometry is sometime also referred to as ansh. Moreover, in his Siddhanta-Shiromani, while computing the instantaneous motion of a planet, Bhaskaracharya notes that the timespan between consecutive positions of the planet is no greater than a truti, or 1/33,750 of a second, and he gives the measures of the velocity in terms of this small unit of time (Joseph 2010).

After discussing basic shapes such as a line and a ray and the angles between them, construction (Rachna) of a curve (Vakra) is of cardinal interest in geometry. However, these may sometimes be a closed curve (Aakriti), and in such a scenario, the boundary (Seema) and its length, or the perimeter (Parimap) and area (Kshetra) are quantities of natural interest. Kshetra primarily refers to a closed figure, but can also denote the area of a figure (Amma 1999). Thus, different kinds of closed geometrical shapes, also called polygons may be looked into, beginning from a triangle (Tribhuj), quadrilateral (Chaturbhuj), square (Varg/ Kriti/ Karani), rectangle (Ayat), pentagon (Panchakarn), octagon (Ashtbhuj) to any n-sided polygons (Bahubhuj), etc. The sides of polygons have been mentioned as rashmi. Of the geometrical shapes possible, the triangles, quadrilaterals, and circles can be examined in some greater detail, owing to their simplicity and thus pervasiveness in all kinds of practical applications.

In his Aryabhata

Ganitapda 6

, Aryabhata discusses the calculation of area of a triangle in these words –

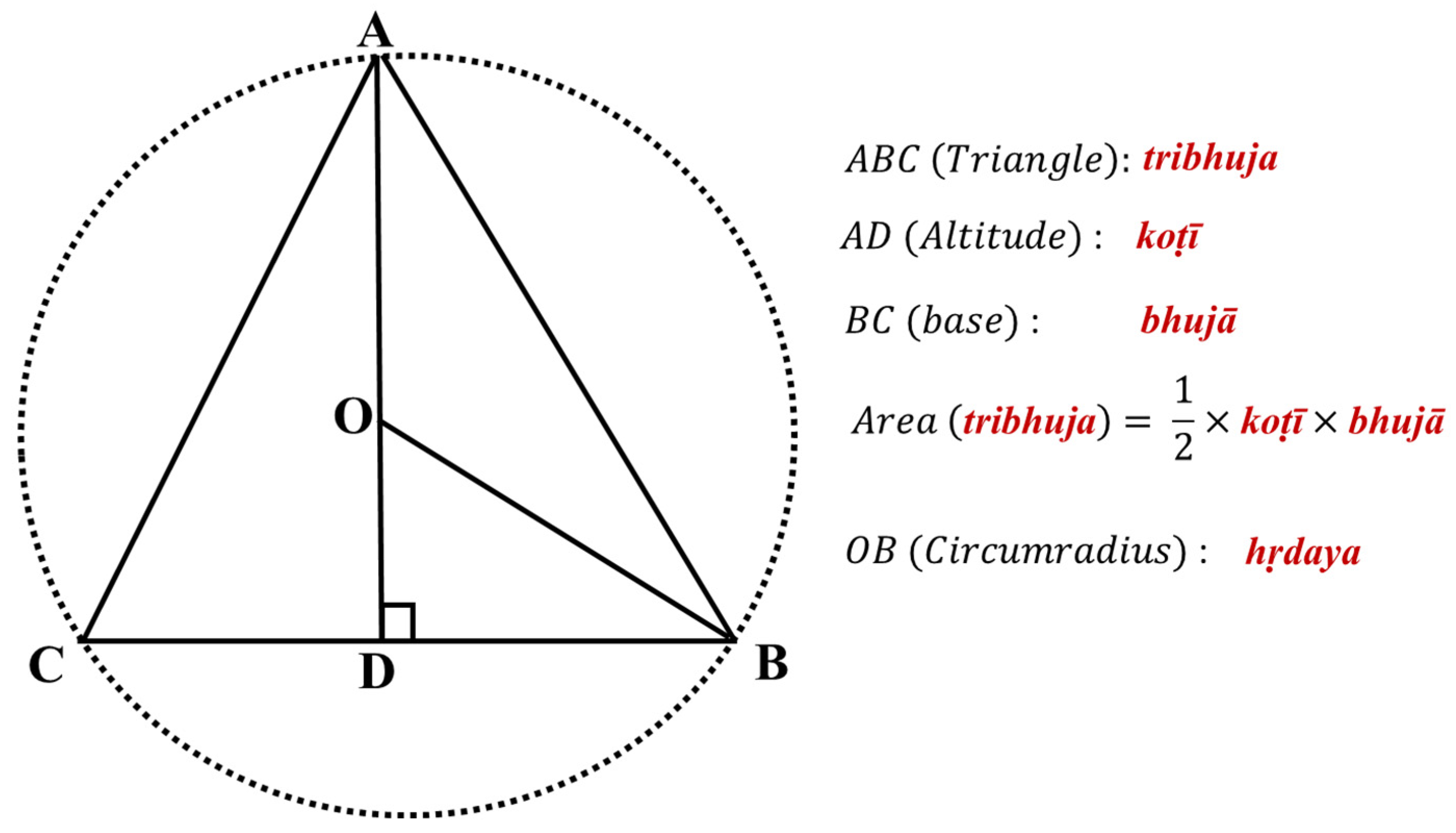

The result of the perpendicular (from opposite vertex) and its product with half the length of the side is its area. As illustrated in

Figure 3, here, Aryabhata refers to the base of the triangle as the

bhuja, whereas the perpendicular from the base (

dal) is referred to as

koti. This altitude of a triangle has also been referred to as

isuby Katyayana (Amma 1999), although conventionally

isu (meaning arrow) has been used to denote height of an arc, which is denoted by

chaapor

dhanu. Bhaskaracharya describes this in his Leelavati (Text 141)

In a right-angled triangle, one of the sides is called the base (bhujaor bahu), and the side perpendicular to it is called the altitude, koti (Patwardhan et al. 2006).

Next, a quadrilateral is referred to as

chaturbhuja (or

Chaturasra) and can be a parallelogram, rhombus, rectangle (

Ayat), or a square (

Vargaor

Kriti). The Shulbasutras provide a clear understanding between lengths and areas. Apastamba (Ap. Sl. III. 6-7) says –

“With two four, with three nine. As many units as there are in a cord, so many squares are produced by it” (Srinivasachar and Narasimhachar, 1931).

The square root from four sets of half the sum of the sides respectively diminished by the sides and multiplied together is the exact area. Or, half the sum of the base and the face multiplied by the altitude, but not in a

vishama quadrilateral. This is ample evidence that Mahavira knew that the expression

holds good for isosceles trapezium, although he does not state this to apply to scalene trapezium too. Brahmagupta in his

Brahma-sphuta-Siddhanta highlights some other properties of trapezium, although he does not comment upon its area.

In quadrilaterals other than the

vishama, the square root of the sum of the products of the opposite sides is the diagonal. The square of the diagonal less the square of half the sum of the base and the face is the altitude (Sharma et al. 1966). Rectangles are addressed differently, sometimes as

visama chaturasra or Ayat as well, as shown in the text below:

Mathematicians like Maskari, Purana, and Putana show the rationale of the areas of all figures in rectangular figures.

The diagonal of a square or a rectangle is denoted by

karna, karanam, vikarnaor

shruti, all referring to ear, although the semantic basis for this usage is not exactly clear (Amma 1999). The Sanskrit word

karani means “producer” or “that which makes”, and gradually it came to represent the sides of a rectilinear geometrical figure of any shape, and later, more specifically, the side of a square. Katyayana Shulbasutra (II. 15-18) describes –

“The one-third maker is expounded by this. The division of the measure (of the area) is into nine parts. One-third of the karanii.e., the side of the square makes one-ninth (of the area). Three ninth parts have one-third as its karani or maker”(Amma 1999). Further, Katyayana also discusses the construction and properties of pentalaterals or panchakarna(Datta 1932).

Mandalaor

Parimandaladenotes a circle, and

Parinahastands for circumference, although it is less commonly used. The other word for the circumference is

paridhi, as can also be seen in the

Lilavati text 201 by Bhaskaracharya –

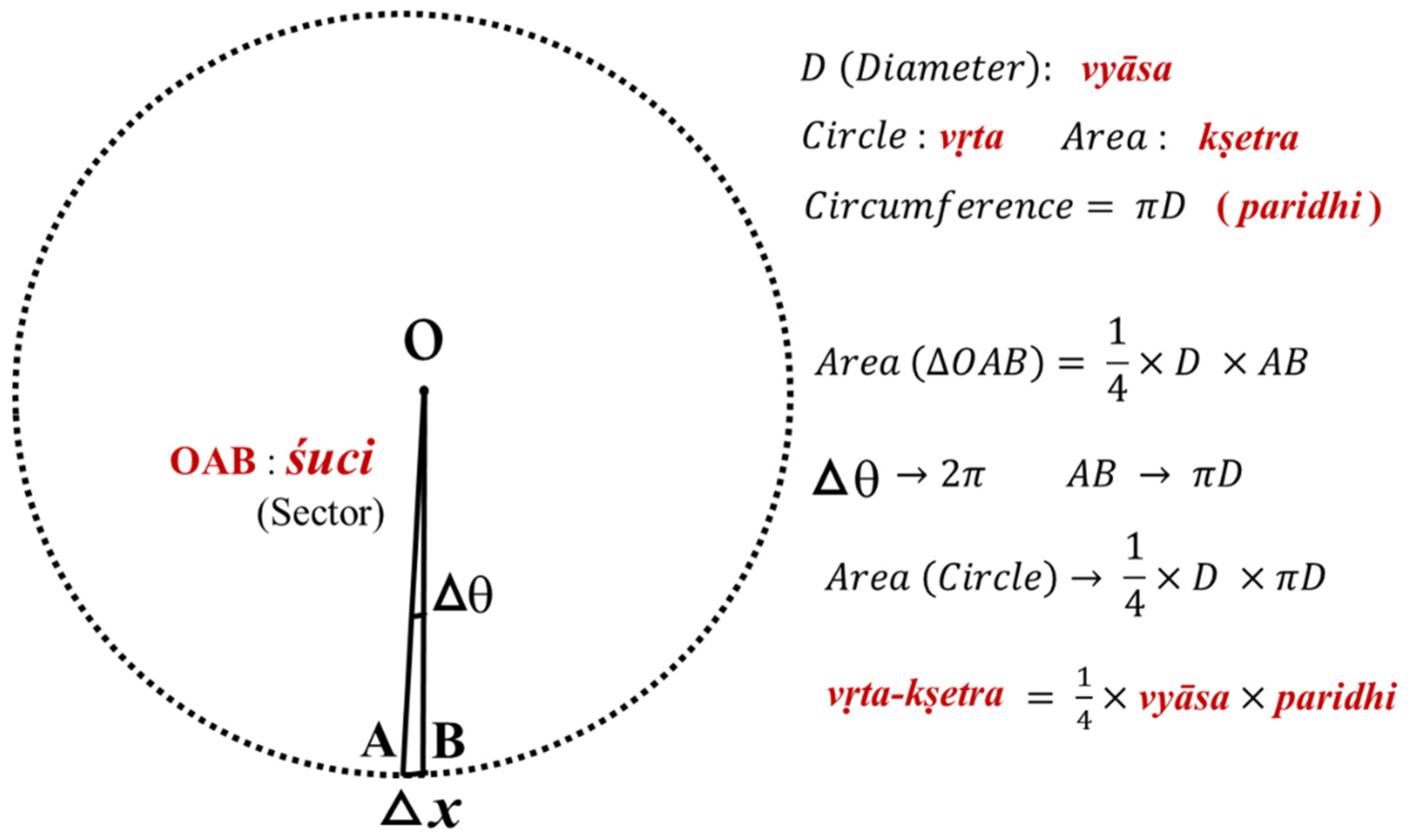

“In a circle, the circumference multiplied by one-fourth the diameter is the area, which multiplied by four, is its surface area going round it like a net round a ball. This (surface area) multiplied by the diameter and divided by six is the volume inside the sphere (Amma 1999).” Indeed, as illustrated in

Figure 4, the area of a circle (

) is identical to circumference (

So, does the surface area of a sphere (

correspond to the area of the great circle (

Finally, the surface area (

is equivalent to (

, the volume of a sphere. At this point, it may also be important to notice the usage of

parinaha for circumference by Aryabhata in Aryabhata Ganitpada in a text, which also gives an approximate value of

“Four more (of) hundred, times eight, likewise (more) of sixty-two thousand, nears the circumference of a circle of diameter 20000.” In other words, the approximate value of , as suggested by Aryabhata is , or 3.1416. The radius and diameter of a circle are represented by trijyaand vyas(or viskambha) respectively. Shuchi refers to the sector of a circle, and jeev to its chord. Hridaya refers to the circumradius and jya refers to the sine in trigonometry.

Moreover, Indian mathematicians have extensively elaborated on three-dimensional surfaces as well, and some relevant terminologies worth indicating are the allusion to a three-dimensional surface by

falak, the reference to a sphere by

gola, annulus by

nirgama, part of an annulus by

nemi,and a cone by a

shanku. The list of extant names of people from geometry in the Indian context is practically endless, although some more examples are presented in a later section on names specific to the practice of mathematics in the Vedic tradition. It is worth mentioning that the mathematical pretext provided above is not to provide an exhaustive account of the developments of geometry in India, which would be a cumbersome task. Rather, the goal is to merely point out a sample of terminologies pertaining to geometry which pervasively appear as names of individuals in India.

Table 1 enlists all the terminologies introduced above, with examples of the verifiable names of the individuals in the Indian subcontinent currently. As the table presents, names based on geometry exist in all the sub-categories of fundamental geometrical concepts, arc and angle measurements, curves and its characteristics, triangles, quadrilaterals, polygons, circles, and three-dimensional surfaces. Further, for all the suggested terms in geometry, names can be found to exist in both genders, barring a few exceptions, when only feminine names have been found. That such an observation could be made in the Indian society may not just seem counter-intuitive, but may even come as a surprise to those who have subscribed to the usual tirade of deprivation meted out to women in terms of basic education, much less, a subject such as geometry. However, if so were to be the case that women in India were not taught a subject such as geometry, it is highly unlikely that their names would be associated with it, when they had to be supposedly kept away from it. At any rate, such names would not be at par, or greater than the male names. Needless to say at this point that such naming among the females isn’t a recent phenomenon brought about by the westernization in education and society.

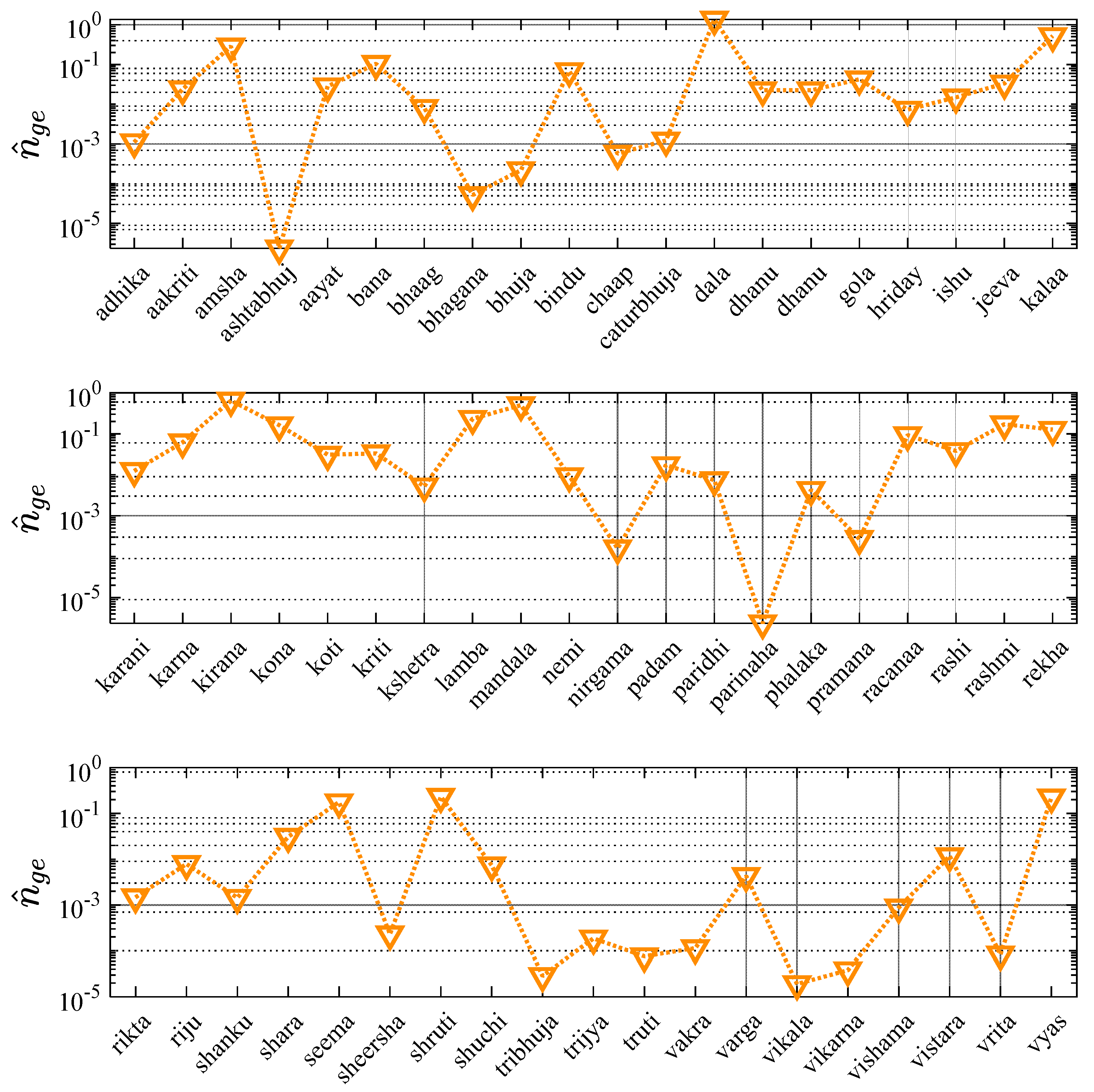

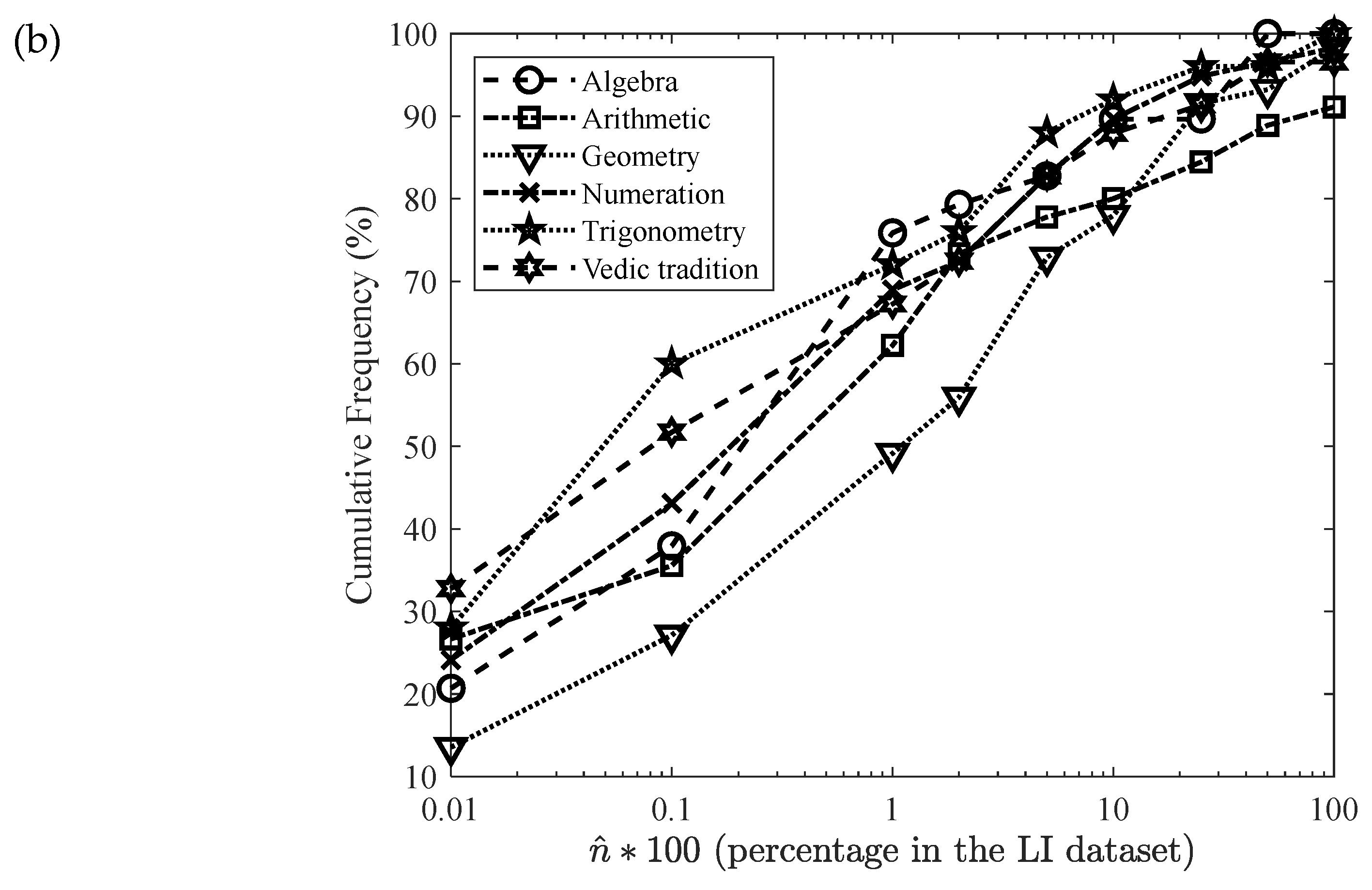

Figure 5 furnishes the quantitative evidence of the recurrence of the names based on geometry as presented in

Table 1, from the LI dataset. It presents the specific name recurrence fraction for sixty-three names based on geometry,

in an alphabetical fashion. As the figure shows, the left axis denotes name recurrence factor in the LI dataset, which multiplied by a hundred yields ‘recurrence percentage’. This figure demonstrates that

varies between 2.37x10

-6 to 1.36, or in other words, between 0.0002 % to 136%. It is not surprising to find a percentage value corresponding to the term ‘

dala’ attain a value greater than cent percent, since ‘

dala’ is a name in multiple cultures apart from Indian. Thus, the LI dataset yields a greater count for ‘

dala’ than the normalizing “most ubiquitous Indian name” say, ‘Rahul’ which is a name mostly in India and southern Asia. Further, some of the terms with highest

are ‘

dala’, ‘

kirana’, ‘

kala’, ‘

mandala’ and ‘

amsha’ with

corresponding to 1.36, 0.64. 0.52, 0.50 and 0.28 respectively. On the other hand, terms like

parinaha,

astabhuja,

vikala,

tribhuj and

vikarna fare very low on the

value. Other terms which occur in the high frequency range are

sruti, vyas, seema, rashmi, kona, rekha, bana, rachna, rashi etc. – names that can be very commonly heard in the Indian setting.

5.2. Trigonometry

The original Hindu name for the science of trigonometry is

jyotpatti, which is a compound term made of ‘

jya’ (implying ‘Sine’) and ‘

utpatti’ (meaning construction) and thus it connotes ‘The science of the construction of the Sines’ (Dutta and Singh 1983). This term can very easily be traced back to as early as Brahma-sphuta-siddhanta of Brahmagupta (628 CE), although the science per se can be dated to be much older. In fact, the reference to this science as trikonamiti is of much recent origin, after the literal translation of its Grecian counterpart. As per the earliest extant records available in the Surya-siddhanta, the Hindus typically utilized three trigonometrical functions (‘

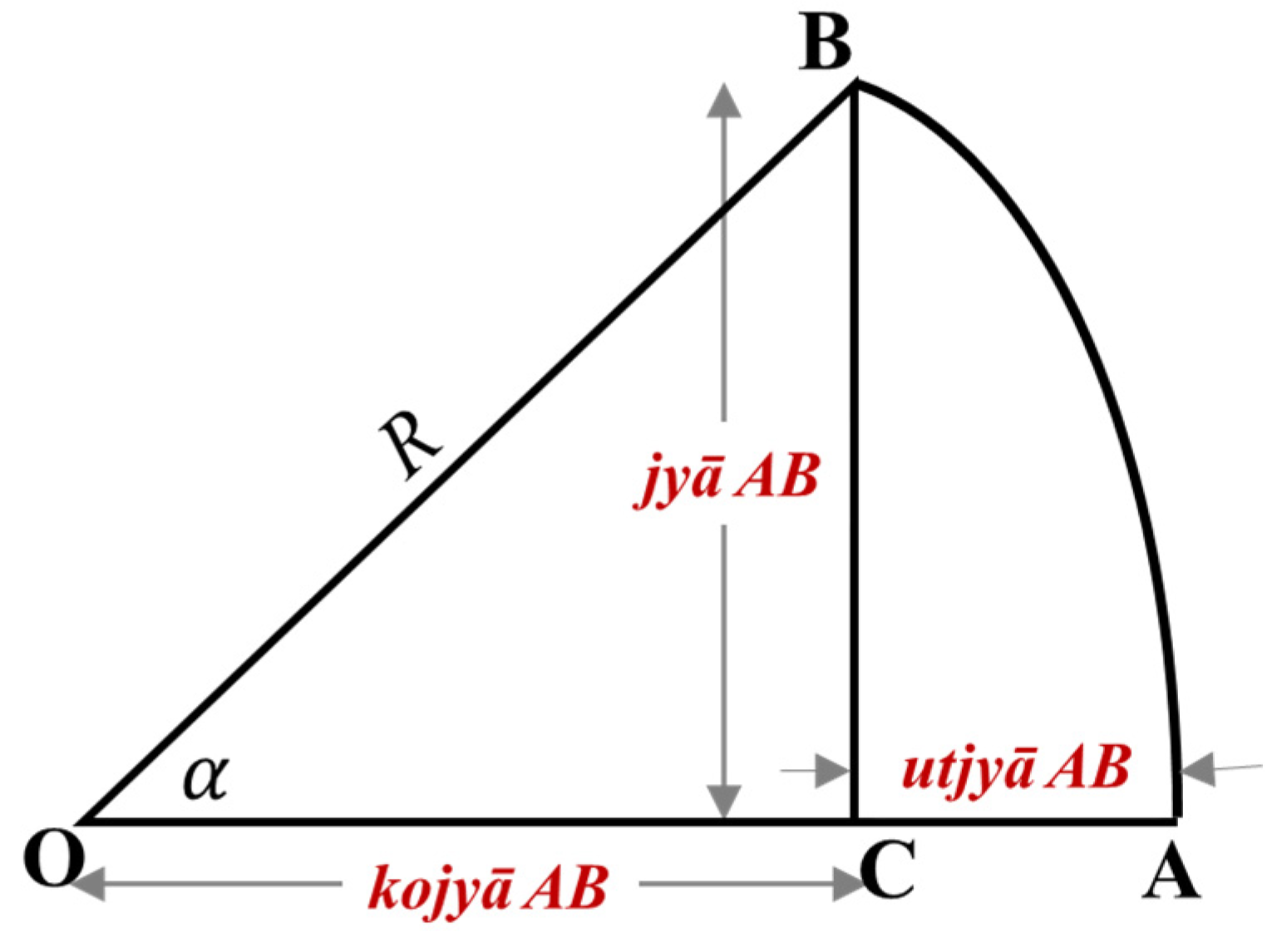

phalan’) of an arc of a circle: jyā, koti-jyā and utkrama-jyā as presented in

Figure 6. From

Figure 6, it is clearly evident that if AB be an arc of a circle centered at O, then BC, OC and AC are denoted by jyā AB, koti-jyā AB (abbreviated as

kojyā) and

utkrama-jyā AB (shortened as

utjyā), respectively. Further, when normalized by the radius of the arc (trijya) R, these yield sin α, cos α and versin α (= 1 - cos α), respectively where α is the angle subtended by the arc at the centre O.

An etymological account of the metamorphosis of the modern ‘sine’ is an interesting tale in itself. Incidentally, the modern sine derives from the Hindu term for chord jyā or jīvā, which was transliterated as jībā in Arabic, and abbreviated as “jb” since Arabic is not written with short vowels. Later in the 12th century, during the translation of these Arabic texts into Latin, “jb” was interpreted as “jaib” implying chest, so the Latin equivalent for ‘bosom’ was employed and the term “sinus” was suggested. Thus, the modern sine was introduced in the 1590s. Moreover, since jyā evolved into sine, naturally kojyāgot transformed into kosine, or the cosine. Similar degeneration and alteration of the term kramajyā occurred upon its translation into Arabic, where it appears as karaja or kardaja and later as kardaga, karkaya, gardaga etc. in Latin (Dutta and Singh 1983).

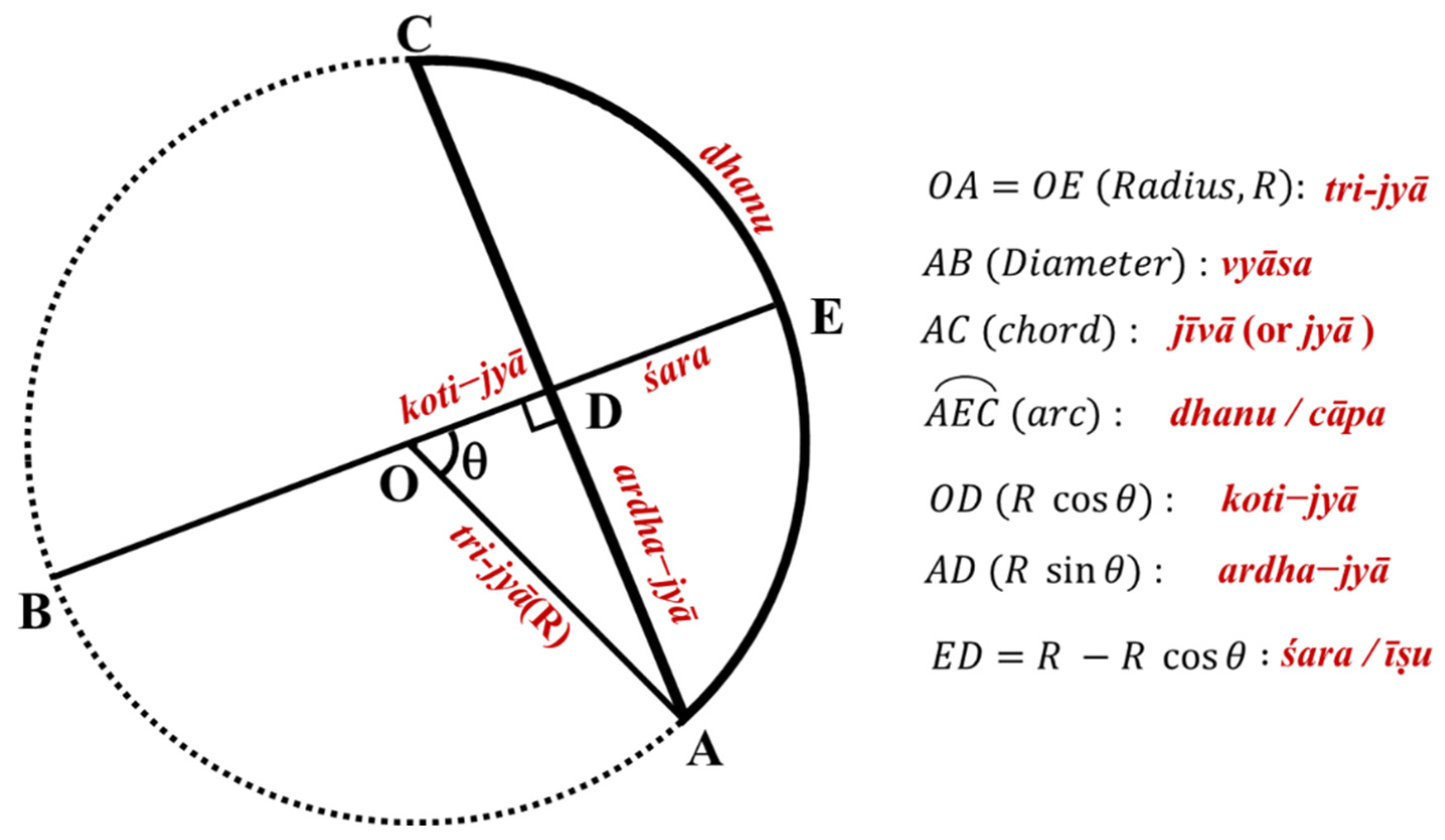

In an attempt to understand the various terminologies pertaining to trigonometry, an analogy of a bow first must be grasped.

Figure 7 further explicates these terminologies using modern trigonometric notations. The arc of a circle (AEC), because of its sheer resemblance to a bow is often called

chapa or dhanu.The sanskrit word

jyā meaning “the string of a bow” literally represents the chord of an arc (AC) formed by connecting the extremities of an arc (A and C). This “full-chord” is termed as

samasta-jyā,

maurvī, siñjinī or

jīvā. Half of this length is called a “half-chord” (AD) and half of the arc AEC (i.e., arc AE) is called the bow of the half chord AD. This half-chord or

ardha-jyā, for brevity, is simply referred to as

jyā by mathematicians. To distinguish it from the full chord, it is also sometimes stated as

krama-jyā, meaning ‘direct Sine’ or ‘direct half-chord’, i.e.,

R. Next,

koti denotes the complement of an arc to 90

o, and hence

koti-jyā (

kojyā) represents ‘the

jyā of the complementary arc’, or

agra, as stated in the

Vateshvara-Siddhanta (Shukla 1986). Put differently,

agra connotes the

jyā of the

poorak kona (complementary angle) and accordingly,

kojyā (OD) is identical to the modern

R. Finally,

utkrama-jyā (

utjyā or by Sanskrit liaison,

ujjyā) literally means “reversed sine” and is computed as

, or simply put, the difference between

tri-jyā (

R) and

kojyā (

R). It is also referred to as ‘

viloma-jyā ‘ or ‘

vyasta-jyā’ and owing to its similarity to an arrow placed over a bow, it is alternatively called as ‘

śara’, ‘

īṣu’ or ‘

bāṇa’. In Hindu trigonometry, although tangent and secant functions were utilized in astronomical calculations, no express recognition was given to these functions. Needless to say, these geometrical functions can easily be represented in terms of

jyā and ko

jyā.

In Hindu trigonometry, a circle is divided into four equal parts by two perpendicular lines intersecting at the centre, usually the east-to-west (

prācī) and the north-to-south (

udīchī). The resulting four quadrants (vrit-pada) are categorized into odd (

ayugma) and even (

yugma). According to Bhaskaracharya, proceeding from the east-point (prachi), the quadrants should be labeled as odd and even successively (Dutta and Singh 1983). It is worth noting that the Hindu system of quadrants is identically alike to the modern system. Further, one can get a fair idea of how much the developments in modern trigonometry owe their genesis to the Hindu mathematicians by even a cursory study of the treatises of Aryabhata, Lallacharya, Bhaskara I, Bhaskaracharya, Varahamihira, Madhava, Sripati, Manjula, Kamalakara, Brahmagupta, Paramesvara, Balabhadra, Munisvara among others.

Table 2 presents a comparison between the trigonometry identities as proposed by Hindu mathematicians when these are juxtaposed with their modern trigonometric counterparts. It should suffice to say that some of these salient examples should patently establish to any reader of their cardinal contributions to trigonometry, be it the basic relation between functions such as sine and cosine (#1), functions of a complement (#2), change of sign of a function in different quadrants (#3), functions of multiple and submultiple angles (#4-7), addition and subtraction rules for sines and cosines (#8-9), values of functions for particular angles, the law of Sines ordinarily used in the solution of triangles (#10), trigonometrical tables in astronomy, technique of interpolation for getting function of any arc, various approximation of functions (#11), infinite series of sine (#12), cosine (#13) and spherical trigonometry.

Some typical references may be produced here for the sake of illustration of the usage of these terminologies in the Indian texts. Although possible, for the sake of brevity, a text corresponding to every term is not being produced, rather a few are being cited. For instance, the approximation of the value of the arc in terms of the chord given by the Aryabhata school is attributed to Nilkantha Somyaji in Aryabhata Ganitapada -

Or, the square root of the sum of one and one-third the square of the arrow and the square of the (sine) chord is nearly equal to arc.

A commentary on

Tantrasamgraha explains:

“The mutual product of the sine chords divided by the radius is regarded as the altitude” (Amma 1999).

Bhaskaracharya in his Jyotpatti, which occurs in an appendix to the Siddhanta-Siromani-Goladhyay provides an exact value of Sine of 18 degrees, as follows:

“Subtract the radius from the square root of the product of the radius-square and five, and divide by four; that becomes the true Sine of the eighteen degrees”. In other words,

Or,

Table 3 enlists all the terminologies in trigonometry introduced above, with examples of the verifiable names of the individuals in the Indian subcontinent currently. As the table presents, names based on trigonometry span across arc, chord, sine, cosine, versin, quadrants, etc. Further, as before, for all the suggested terms in geometry, names can be found to exist in both genders, barring a few exceptions, when only feminine names have been found. That such an observation could be made in the Indian society may not just seem counter-intuitive, but may even come as a surprise to those who have subscribed to the usual tirade of deprivation meted out to women in terms of basic education, much less, a subject such as trigonometry. However, if so were to be the case that women in India were not taught a subject such as trigonometry, it is highly unlikely that their names would be associated with it, when they had to be supposedly kept away from it. At any rate, such names would not be at par, or greater than the male names. Needless to say at this point that such naming among the females isn’t a recent phenomenon brought about by the westernization in education and society.

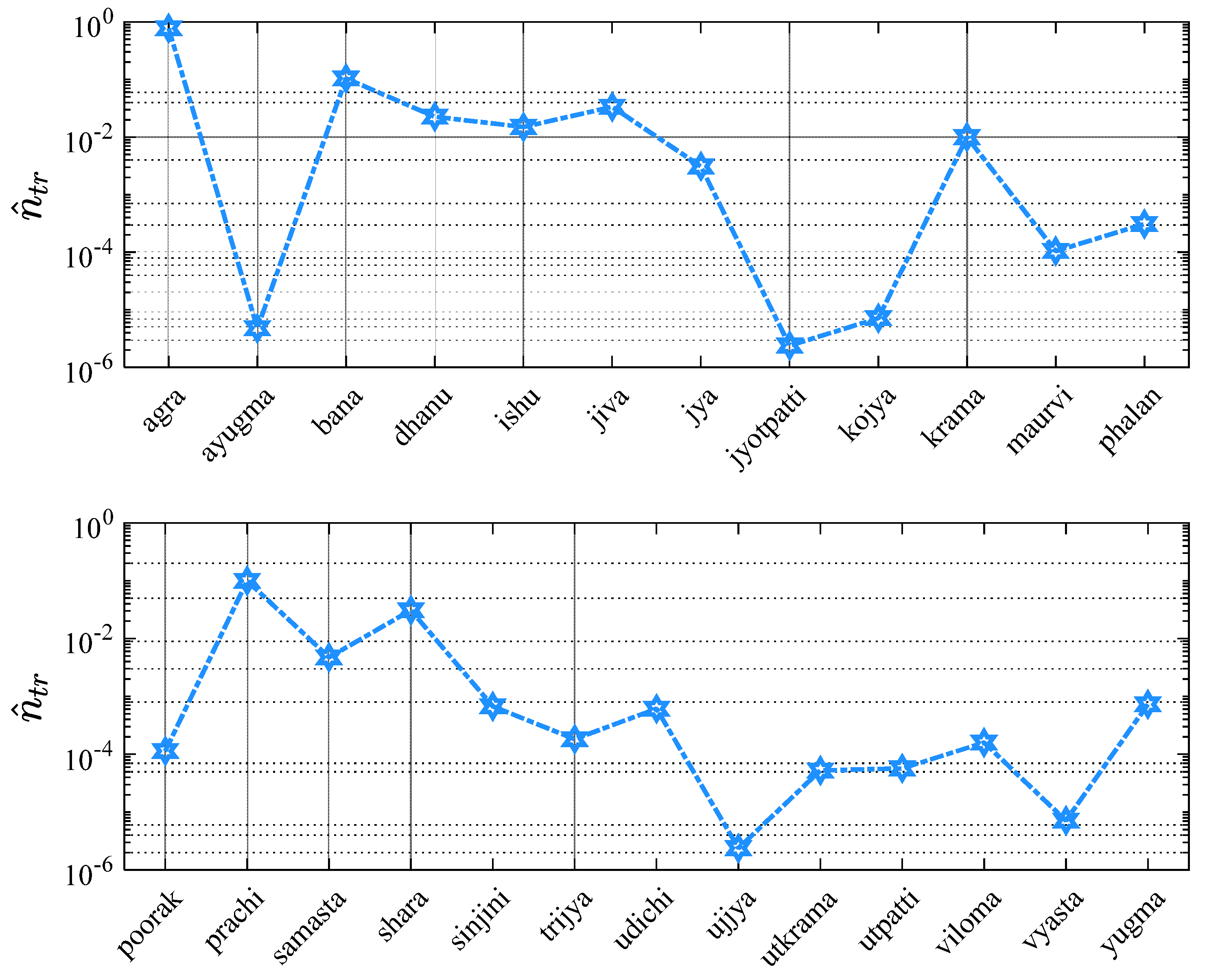

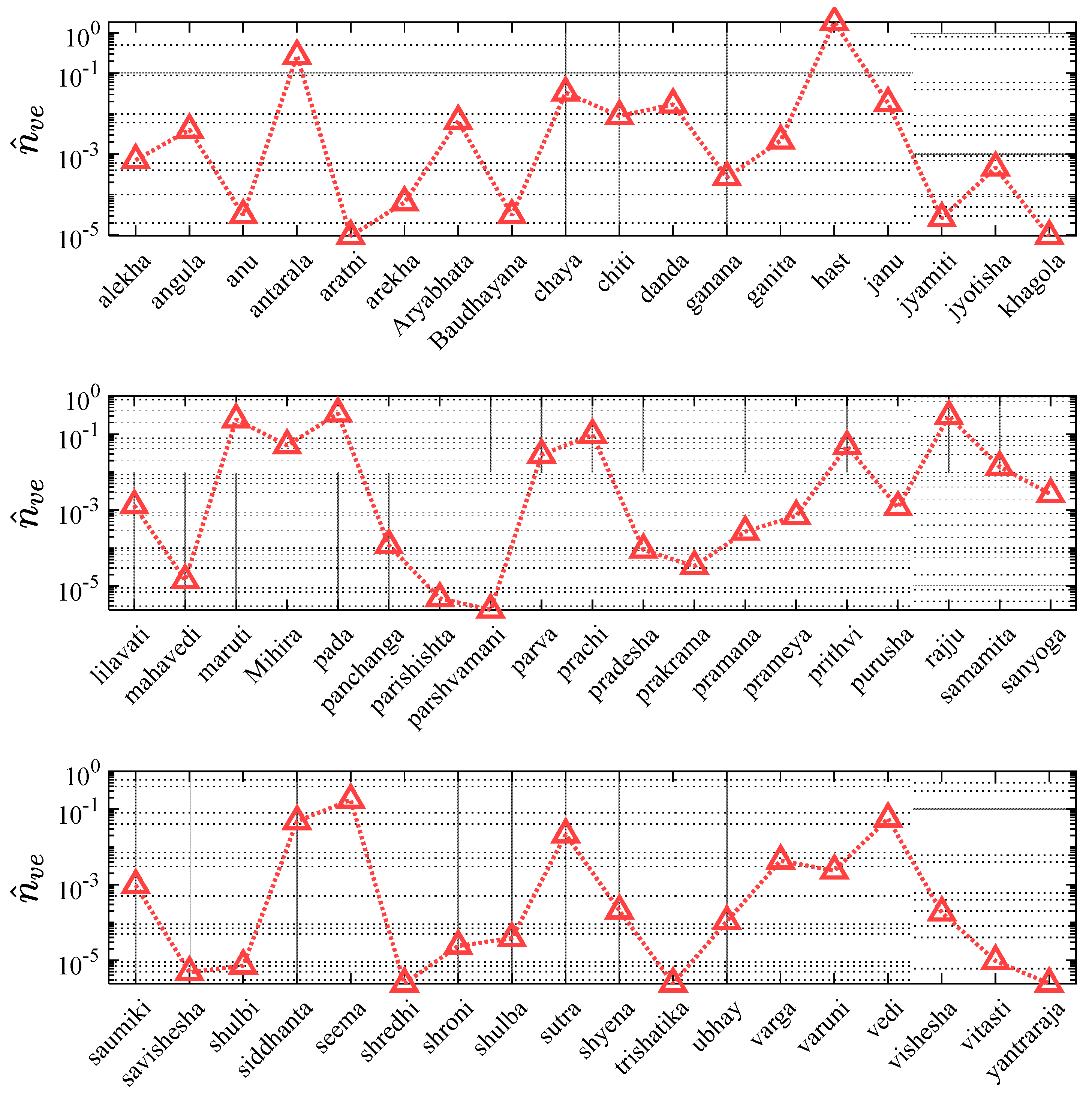

Figure 8 provides the quantitative evidence of the recurrence of the names based on trigonometry as presented in

Table 3, from the LI dataset. It presents the specific name recurrence fraction for twenty-four names based on trigonometry,

in an alphabetical fashion. As the figure shows, the left axis denotes the name recurrence factor in the LI dataset, which multiplied by a hundred yields ‘recurrence percentage’. This figure demonstrates that

varies between 2.37x10

-6 to 0.77, or in other words, between 0.0002 % to 77.4%. Further, some of the terrms with highest

are ‘

agra’, ‘

bana’, ‘

prachi’, ‘

jiva’ and ‘

shara’ with

corresponding to 0.77, 0.10, 0.099, 0.033 and 0.03, respectively. On the other hand, terms like

ujjya, ayugma, vyasta, kojya and

utkrama fare very low on the

value. In general, names under this division are somewhat uncommon to be heard, particularly in the North Indian setting. For instance, names like

yugma, sinjini, udichi, phalan, trijya, maurvi and

utpatti fall under this category. However, there is a point worth taking into account – any conclusion regarding the mathematical traditions of India can’t be just gauged and summarized from a limited perspective of a particular region, be it Kerala, Bihar, Ujjain, Bengal or Gujarat. Rather, the influence of mathematics upon the entire Indian kaleidoscope has to be observed. Thus, terms such as

sinjini and

udichi may not appear a befitting name of an individual in north and west regions of India such as Punjab, Rajasthan, or Delhi – but appears as a name in West Bengal. This observation further underscores the need for a comprehensive study such as this.

5.3. Numeration

The description of the number system and its standing tradition in India may befittingly begin with the description of the invention of zero, also called shunya. The earliest description of zero can be found in Gayatri Chanda by Pingala Acharya in at least 300 BCE:

“In Gayatri-chanda, one pada has six letters. When that is made into half, it becomes three. Remove one from it and make it half to get one. Remove one from it and put a zero (Shunyam).” However, it was Brahmagupta, who in his Brahma-Sphuta-Siddhanta, written in 628 CE, introduced the seminal concept of zero as a number in its own right, a conceptual leap from what had been done before him. The Sanskrit equivalent for one is pratham or ekam, both of which figure out commonly as Indian names in various forms. The Sanskrit root for two is dvi, which can be heard most commonly in the surname dwivedi, which literally means ‘the knower of the two vedas’. Along the same lines, of the four vedas, Rgveda, Samveda, Yajurveda and Atharvaveda, one who knows only one may be termed vedi, or presumably in its colloquial form as bedi. Similarly, the knower of the three vedas are called trivedi and the knower of all the four Vedas are chaturvedi. Colloquially, the word for two is ‘dwitiya’. The sense of ‘two’ is also captured in the words advaita and dvaita, i.e., non-dual and dual, most certainly due to the existence of these schools of spiritual tradition as enunciated and taught by Adi Shankaracharya and Madhvacharya, respectively. Other names representing three such as trayee or tritiya also exist as feminine names. Chatur which is a root meaning four occur as names in its root form, or in other forms described earlier such as chaturth, chaturthi, chturbhuja and chaturvedi. In the same way, panch also occurs in its root form, as well as another colloquial form panchama or panchami. Names pertaining to six to ten appear frequently, in the names of shad, sapt, ashta, nava and dash, respectively or in a feminine sense shashthi, saptami, ashtami, navami and dashmi. The names eleven to fourteen such as Ekadashi, dvadashi, trayodashi, chaturdashi etc. correspond to the eleventh, twelvth, thirteenth, and fourteenth day from the new/full moon and appear in both genders, most probably due to the repeated reinforcement caused in the collective Indian social consciousness by the existing lunar calendar. A similar is the case with shodashi, which typically connotes a sixteen-syllable incantation (mantra). Next, the numeric names can only be found in multiples of ten, such as twenty (Vinshti), thirty (trinsh), sixty (shashtih), seventy (saptati), eighty (ashiti), ninty (navati), and hundred (shata). It may also be pointed out that hundred and thousand are frequently used to denote large quantities in mundane and ordinary transactions, and thus it is not surprising to find many other derivatives of these units such as Shatakshi (meaning one with hundred eyes) and Sahasrabudhe (One with a thousand-fold intelligence). Post hundred, the names can be found in the exponents of ten – and some variations can be found in how different powers of ten are described in Jaina tradition, by Hindu mathematicians such as Aryabhata and in ancient texts such as Valmiki Ramayana. However, the focus of the current paper is not to dwell on the correctness, exactitude, origin, or even pre-eminence of any system of numeration, but solely to focus on the terminologies which are extant as names in modern India, irrespective of the mathematical tradition from which it is derived.

In the decimal place-value system of numerals in India, which is a remarkable scientific gift to the civilized mankind, ten has been the base for counting since Vedic times. Ranging from hundred (10

3), and thousand (10

3), the higher exponents such as

ayuta (10

4),

niyuta (10

5) and

prayuta (10

6) referring to a million are also common. Another frequent alternative to

niyuta is

laksha. In fact, several non-decimal scales of numeration were current in India for practical enumeration up to very large numbers, and one of such schemes as presented in the Valmiki Ramayana describes the laksha-scale numeration system in these twelve lines (Gupta 2008):

“A hundred of hundred thousand is said to be koti by the learned, a hunderd of thousand koti is termed shanku, a hundred of thousand shanku is known as mahashanku, a hundred of thousand mahashanku is called vrinda, a hundred of thousand vrinda is known as mahavrinda, a hundred of thousand mahavrinda is called padma, a hundred of thousand padma is known as mahapadma, a hundred of thousand mahapadma is called kharva, a hundred of thousand kharva is known as mahakharva, thousand mahakharva is termed samudra, a hundred of thousand samudra is termed ogha, a hundred of thousand ogha is heard to be mahaugha.”

To sum it up, 10

7 is referred to as

koti, 10

8 as

dashkoti and 10

9 (a billion) as

shatakoti. Billion and trillion (10

12) are also referred to as

arbuda and

shanku, respectively.

Shankha and

Vrinda denote 10

17 and 10

22 respectively and

Padma denotes a quadrillion (10

32). Extremely large quantities such as 10

42, 10

50 and 10

55 have been represented by

kharva,

samudra and

ogha and finally

poorna connotes unlimitedly large numbers, whereas

ananta symbolizes infinity. In fact, zero, infinity, and finite but extremely large numbers owe their genesis to Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism because of their rich metaphysical traditions (Aczel 2015). The concept of infinity has fascinated many Hindu mathematicians and Bhaskaracharya refers to it as

khahara (Zero divisor) and while commenting upon its invariability, likens it to God Visnu. The invocation mantra of īśopaniṣad refers to this inifinite whole as

poorna and states that when poorna is subtracted from poorna, what remains is still poorna.

It is worth noting that there are varying nomenclatures for numeration in India (particularly of large numbers), and here we only focus on the terms existing in mathematics that are extant in societal parlance through the usage of mathematical names. It is interesting to note, however, that there was no concept of denoting such large numbers in the contemporary works of other nations: the Greeks managed a maximum up to 104 (myriad), whereas the Roman terminology ended with 103(mile).

Table 4 enlists all the terminologies in the numeration introduced above, with examples of the verifiable names of the individuals in the Indian subcontinent currently. As the table presents, names based on numeration spans the entire range of the number line from zero to infinity. Further, as before, for all the numbers, be it zero, a single-digit number, a double-digit number, or greater exponents of ten, names can be found to exist in both genders, barring a few exceptions, when only feminine names have been found. That such an observation could be made in the Indian society may not just seem counter-intuitive, but may even come as a surprise to those who have subscribed to the usual tirade of deprivation meted out to women in terms of basic education, much less, a subject such as the study of numbers. However, if so were to be the case that women in India were not taught a subject such as numeration or number theory, it is highly unlikely that their names would be associated with it, when they had to be supposedly kept away from it. At any rate, such names would not be at par, or greater than the male names. Again, we wish to reiterate that such naming among the females isn’t a recent phenomenon brought about by the westernization in education and society.

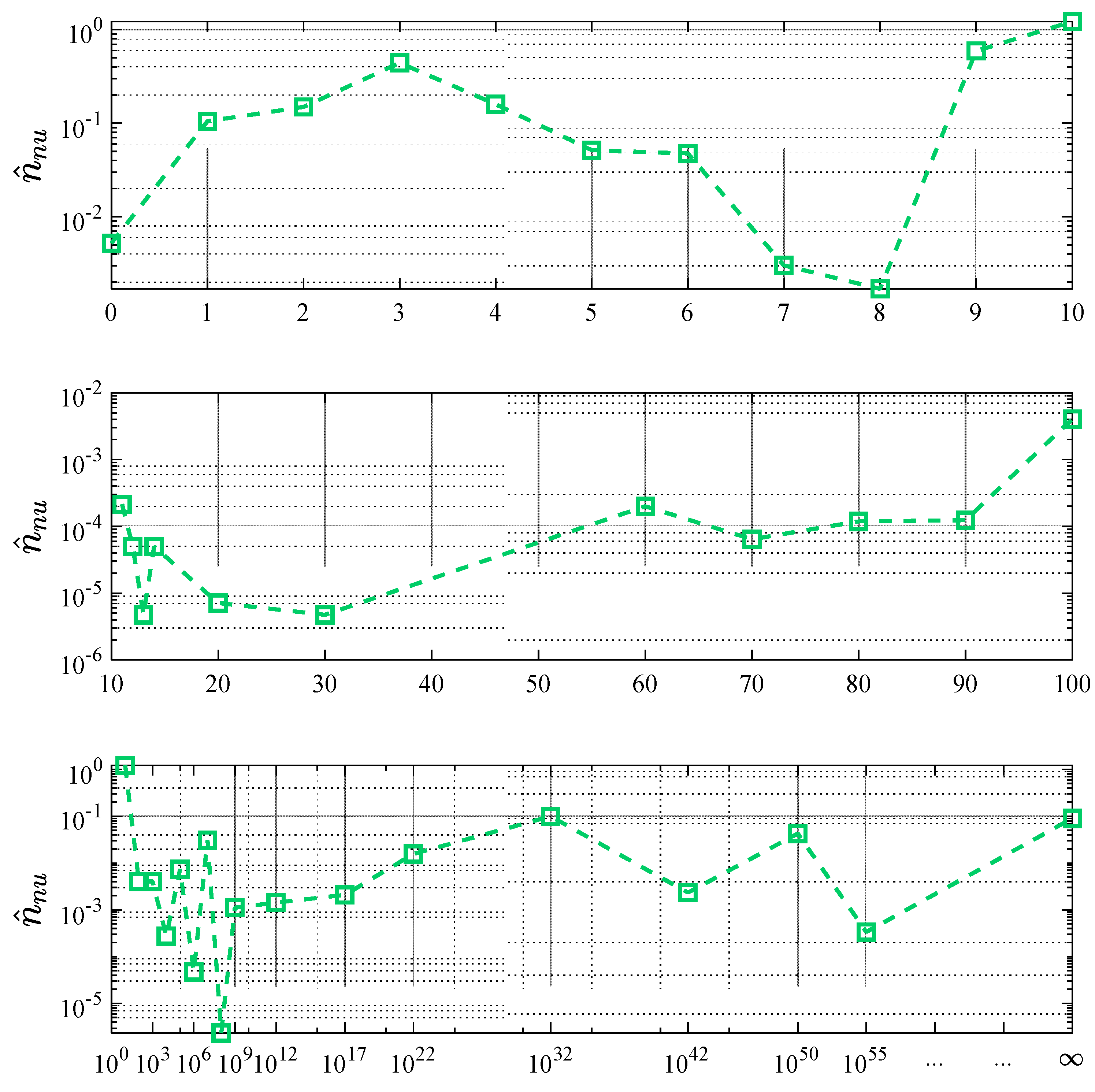

Figure 9 demonstrates the quantitative evidence of the recurrence of the names based on numeration as presented in

Table 4, from the LI dataset. It presents the specific name recurrence fraction for forty-six names based on numeration,

. As the figure shows, the left axis denotes the name recurrence factor in the LI dataset, which multiplied by a hundred yields ‘name recurrence percentage’. In presenting this figure, however, a different methodology has been followed as compared to before. All the terms corresponding to a particular number have been grouped together and their numeric values have been summed up. For instance, for the number 2, all the terms such as

dvi, dvitiya, dvaita, advaita etc. have been clubbed together. This figure demonstrates that

varies between 2.37x10

-6 to 1.2, or in other words, between 0.0002 % to 122%. It is not surprising to find a percentage value corresponding to the term ‘

dash’ attain a value greater than cent percent, since ‘

dash’ is a name in multiple cultures apart from Indian. Thus, the LI dataset yields a greater count for ‘

dash’ than the normalizing “most ubiquitous Indian name” say, ‘Rahul’ which is a name mostly in India and southern Asia. Further, some of the terrms with highest

are ‘

dash’, ‘

nava’, ‘

dvi’ (e.g.,

dvivedi), ‘

tri’ (e.g.,

trivedi) and ‘

padma’ with

corresponding to 1.22, 0.59. 0.14, 0.14 and 0.1 respectively. On the other hand, terms like

dashkoti, khahara, trinsha, trayodashi, vimshati etc. fare very low on the

value. Other terms which occur in the high frequency range are

eka, ananta, shad, prathama, samudra, pancha, purna, etc. – names that can be very commonly heard in the Indian setting.

Moreover, a system existed and was perfected in India of expressing numbers by words arranged as in place-value notation, called the bhūtasaṃkhyā system, or the “word-numeral” system as referred to by Datta and Singh (1935). In this scheme, the numerals are denoted by names of objects, beings, or concepts which naturally in accordance with the scriptural understanding, connote numbers. Some associations are universal (for instance, ‘eyes’ and ‘ears’ for two) while others are deeply rooted in aspects of Indian culture, traditions, cosmology, and cosmogony (Yano 2006). For instance, zero could be represented by words that mean void, sky, etc. ‘One’ could be denoted by something that is truly unique such as the moon or the earth, and its synonyms (Datta and Singh, 1935 p. 55). ‘Two’ could be denoted by eyes, arms, hands, ears, thighs, ashvini or yamala; ‘Three’ could be represente by guna, loka etc.’ ‘Four’ by the Vedas, shruti etc.; ‘Five’ by the senses (indriya), mahabhuta (five gross material elements) or Pandava; ‘Six’ by rasa, rtu (season); ‘Seven’ by parvata, shaila etc.; ‘Eight’ by vasu; ‘Nine’ by dvara, nidhi, Durga etc.; ‘Ten’ by dik, disha etc.; ‘Eleven’ by Rudra; ‘Twelve’ by Aditya, ‘Fourteen’ by Manu, vidya, ‘Fifteen’ by tithi, dina, paksha, etc. and so on. However, if these names were included, the actual list of ‘mathematical names’ would be truly sizable. It is indeed possible that many of these names (such as indu, triguna etc.) may have been reinforced in the societal cognizance on account of veneration for mathematics, it would be very difficult to extricate the fraction of such naming that occurred because of it owing to the simultaneous existence of what we could call as “involutory mathematical names”. The import of the “involutory mathematical names” can be understood by a two-fold process: first, when the pervasive natural names evolved and got absorbed into the mathematical semantics, and the later process of involution in which these names were again codified in the society, possibly with a tinge of mathematical symbolism. At any rate, this bhūtasaṃkhyā system led Yano (2006) to concede that the existence of such a system indicates that the ancient Indians were extremely number-conscious.

5.4. Arithmetic

In fact, arithmetic in Hindu mathematics is called ‘rashi-vidya’ (Datta and Singh, 1935, p.4), since rashi refers to a sum or a number for a mathematical operation. The fundamental quantity is a digit (anka) ranging from zero, one, two etc. to nine, any of which can combine to form a number (sankhya). Hindu mathematicians have dealt extensively with real numbers (Vaastavik sankhya), which can be categorized into rational (Parimeya) and irrational numbers. Irrational numbers such as and were known to the ancient Indians about three millennia ago and more exact approximations to them have been proposed by several mathematicians over the centuries, although it is a matter of conjecture as to whether the concept of irrationality was known to the ancient Indians (Kannan 2014). However, a lot has been reported on the concept and characteristics of rational numbers. Rational numbers can be classified as integers or fractions (bhinna sankhya). Integers can be negative (ṛṇa sankhya), zero (shunya) or positive (dhana sankhya), these terminologies of seeing negative numbers as ‘debt’ and positive numbers as ‘property’, enunciated by Brahmagupta. The set of positive integers ranging from one to infinity can be termed as natural numbers (prākṛta sankhya) and its assortment with zero are the whole numbers (poorna sankhya). Further, the whole numbers can be classified as either odd (viṣama) or even (sama) – depending upon whether it yields a whole number upon division by two. Similarly, natural numbers could also be classified as prime or composite (sanyukta) numbers. Composite numbers have more than two factors, whereas prime numbers do not. Apart from integers, fractions (bhinnaor kalā) could also form a part of rational number. Fraction typically refers to the number of parts in a whole – it is denoted by the number of parts selected or, numerator (ansh) and total number of parts in a whole, denominator (hara) separated by a line. Fractions could be of multiple types: such as a simple (saral), mixed (miśra), equivalent (tulya) or composite (sanyukta). One could even refer to a combination of fractions asprabhāga. Moreover, one can also talk about other kinds of numbers such as a perfect number (saṃpūrṇa saṃkhyā) which in number theory refers to a positive integer that equals the addition of its positive divisors, apart from the number itself. Any finite quantity may be referred to as parimit sankhya. In the Hindu mathematics, many times, the numbers are arranged in a row (pankti) for a mathematical operation, and the numbers may need to be placed in the increasing (ārohana) or decreasing order (avarohana).

Arithmetic usually involves four basic operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division although Hindu mathematicians such as Brahmagupta and Bhaskara II have discussed the squares/cubes and square and cube roots in the same vein (Patwardhan et al. 2006). The process of adding two numbers is denoted by yoga, which means the union, and which follows the additive identity (tat-samaka) as well as closure property (sanvrit). On the other hand, the process of subtracting two numbers is referred to as viyogaor kanitaand the difference is called antara. In a typical multiplication (sanvarga) operation of , a and b are called multiplicands (gunakara) whereas c is known as the product (gunaja). When both the multiplicands are identical, the resulting product is a square (varg), and in the case of three identical multiplicands, the product is a cube (ghana). To put the same thing conversely, a and b are factors (karak) of c ; and c is a multiple (bahuguna) of a and b. Similarly, a division operation (bhaag) of m/n yields a quotient, q (labdhior labdha) and a remainder, r (śeṣa) where m is called dividend (hārya or bhājya) and n is known as the divisor (bhājakaor hara). Abhyāsadenotes an addition or a multiplication operation and the square root of a number (maybe a surd) is called karani. Moreover, arithmetic usually forms the backbone of day-to-day ordinary transactions of profit (laabh) and loss.

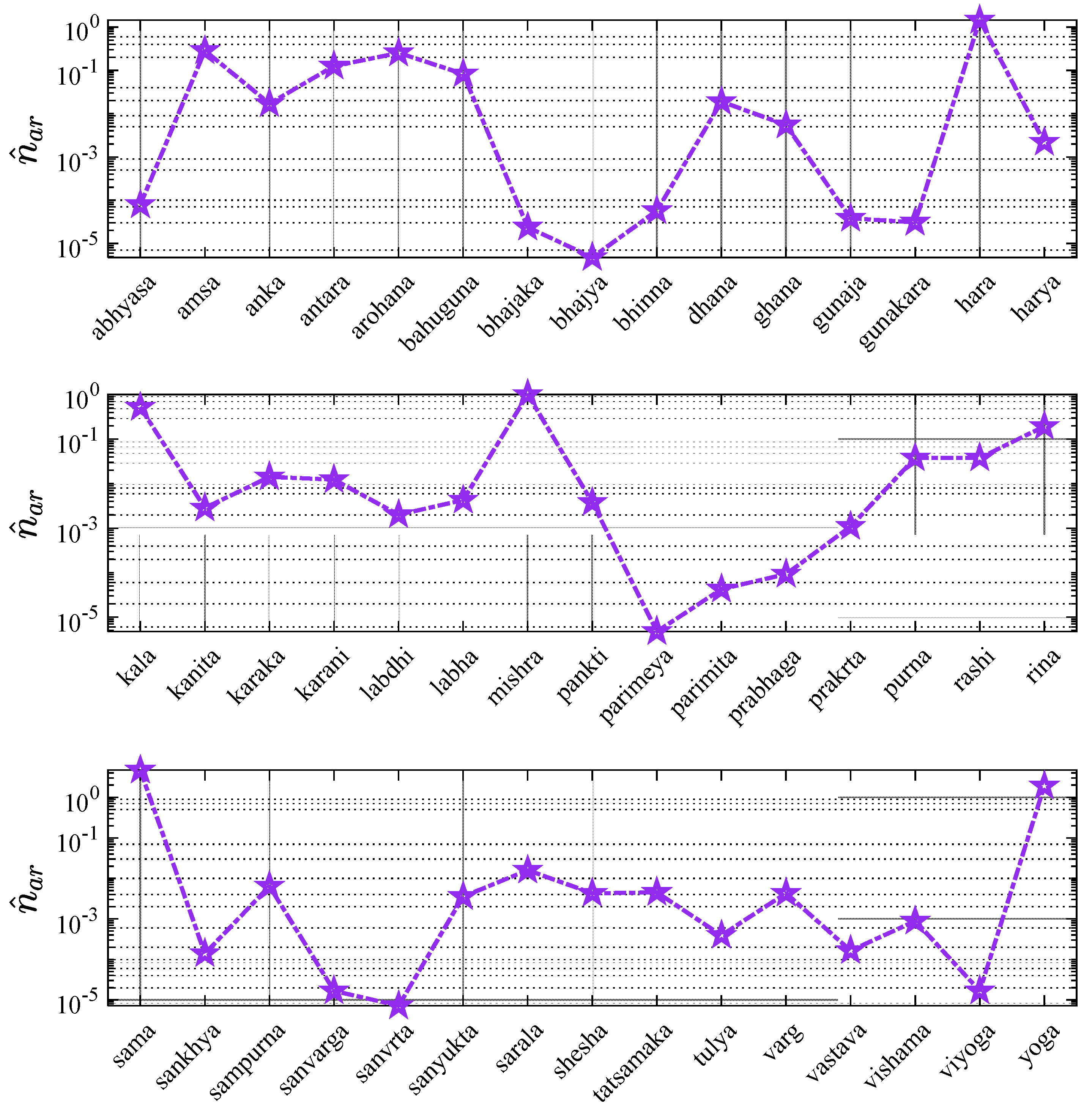

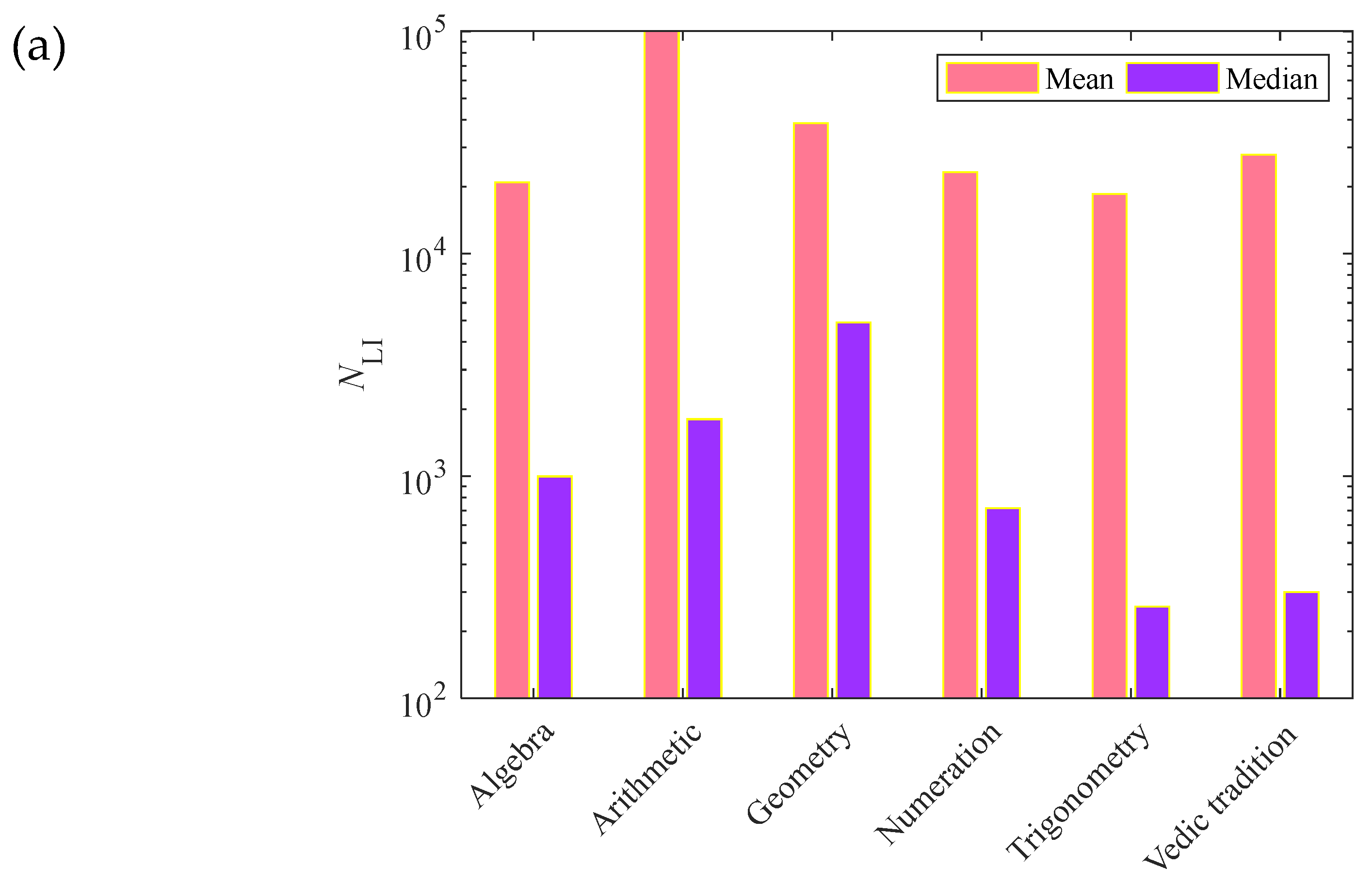

Figure 10 shows that the quantitative evidence of the recurrence of the names based on arithmetic as presented in

Table 5, from the LI dataset. It presents the specific name recurrence fraction for forty-six names based on arithmetic,

in an alphabetical fashion. As the figure shows, the left axis denotes the name recurrence factor in the LI dataset, which multiplied by a hundred yields ‘recurrence percentage’. This figure evidently demonstrates that

varies between 2.37x10

-6 to 4.7. It is not surprising to find a fractional value corresponding to the term ‘

dash’ larger than unity, since ‘

dash’ is a name in multiple cultures apart from Indian. Thus, the LI dataset yields a greater count for ‘

dash’ than the normalizing “most ubiquitous Indian name” say, ‘Rahul’ which is a name mostly in India and southern Asia. Further, some of the terms with highest

are ‘

sama’, ‘

yoga’, ‘

hara’, ‘

mishra’ and ‘

kalaa’ with

corresponding to 4.70, 1.89. 1.44, 1.01 and 0.52 respectively. On the other hand, terms like

parimeya, bhajya, samvrita, viyoga and

samvarga fare very low on the

value. Other terms which occur in the high frequency range are

amsha, arohana, rina, antara, bahuguna, purna, rashi etc. – names that can be very commonly heard in the Indian setting.

5.5. Algebra

Unlike Arithmetic which is the most basic branch of mathematics, that deals with the basic counting of numbers with operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, algebra, on the other hand, deals with similar operations but with variables and numbers. Algebra has been referred to as ‘

Bijaganita’ by Hindu mathematicians, literally alluding to “mathematics by the means of seeds (

bija)”.

Bijaganita is so called since it employs algebraic equations (

samee, saamyaor

samika) and analysis, which, similar to seeds (

bija) of plants have the potential to generate solutions to mathematical problems (Hayashi 2013). Since it deals with unknown quantities expressed in symbols (

varna / cara), it is also called

avyakta-ganita, or “mathematics of unknown quantities”. In such problems, a

sami-karana (equation) is laid out to find the solution (

hala), i.e., value (

maana) of a desired quantity (called

kamika or vancha). Usually, such algebraic relations are expressed with polynomials (

bahupad) on the two sides (

paksha) of the equality (

samtaa), or inequality (when such quantities are called

atulya) and the ratio of two variables is called

anupat. In

bijaganita, the unknown numers are represented by symbols which are the initial syllables of the word यावत् – तावत् (

yāvat-tāvat) or the color names such as

kālaka (black)

, nīlaka (blue) and

pīta (yellow) as per Aryabhata’s

gulikā. A combination of the initials of terms such as

varga (square),

ghana (cube), and

ghāta (product) is used to denote the powers of the unknown numbers and their coefficients are placed to the right of the symbol, with the both sides of the equation being placed one above the other. Negative coefficients are written with a dot above the numbers and the absolute terms in an equation are denoted by the initial of

rūpa, which means an integer (also called as

dṛśya). Joseph (2013) noted that Indian mathematicians were the first to use symbols to denote unknown quantities. For instance, in Prthudakaswami’s commentary on

Brahma Sphuta-siddhanta, an illustration of

yavat-tavat representation is given. As per his illustration, an equation such as

would be expressed as:

,

The product of two different unknowns is known as

bhāvita(produced) and denoted by its initial letter as in

yākābhā 5 for 5

xy (Hayashi 2013). Bhaskaracharya, however, did not use the

yavat-tavat system for solving equations, although it was well developed during his time. For instance, in his book, Leelavati, he gives many methods for solving equations, such as the method of transition (

Sankramana) in text 61 -

This text states the Sankramana method, by which one can obtain two unknown numbers whose sum and differences are known – by adding and subtracting the numbers and dividing them by two. Similarly, the rule of concurrence is known as sankrama.

Aryabhata used gulikāas a term for unknown numbers in his rule for solving linear equations of the type mx + c = px + q in his Aryabhatiya (499 CE). Brahmagupta, on the other hand, suggested many theorems for the indeterminate equations of the second degree, also called varga-prakriti(literally meaning ‘square nature’) by Hindu mathematicians, later called (incorrectly) as the Pell’s equation: Nx2 + z = y2 (where N, z are integers). The coefficient N is called gunaka (multiplier) and z is called ksepa(additive). Brahmagupta’s bhāvanā (lemma) combines two solutions (x1, y1, z1) and (x2, y2, z2) of the varg-prakriti Nx2 + z = y2 to produce a third solution (x3, y3, z3) which are given as x3 = x1 y2 + x2 y1, y3 = N x1 x2 + y1 y2 , z3 = z1 z2. In general, bhāvanā was used by ancient Indian algebraists to refer to a principle of “composition” introduced by Brahmagupta, by which two mathematical objects of a certain type can be combined to yield a third object of the same type (Dutta 2017). For instance, the Samasa-bhavana (additive composition) provides infinitely many integral solutions to the equation Nx2 + 1 = y2 from a given non-trivial integral solution. Brahmagupta’s novel concepts also led to the discovery of the cakravala(cyclic) algorithm, which is a perfect error-free method for obtaining minimum positive integral solutions to Nx2 + 1 = y2 for any N (Dutta 2002).

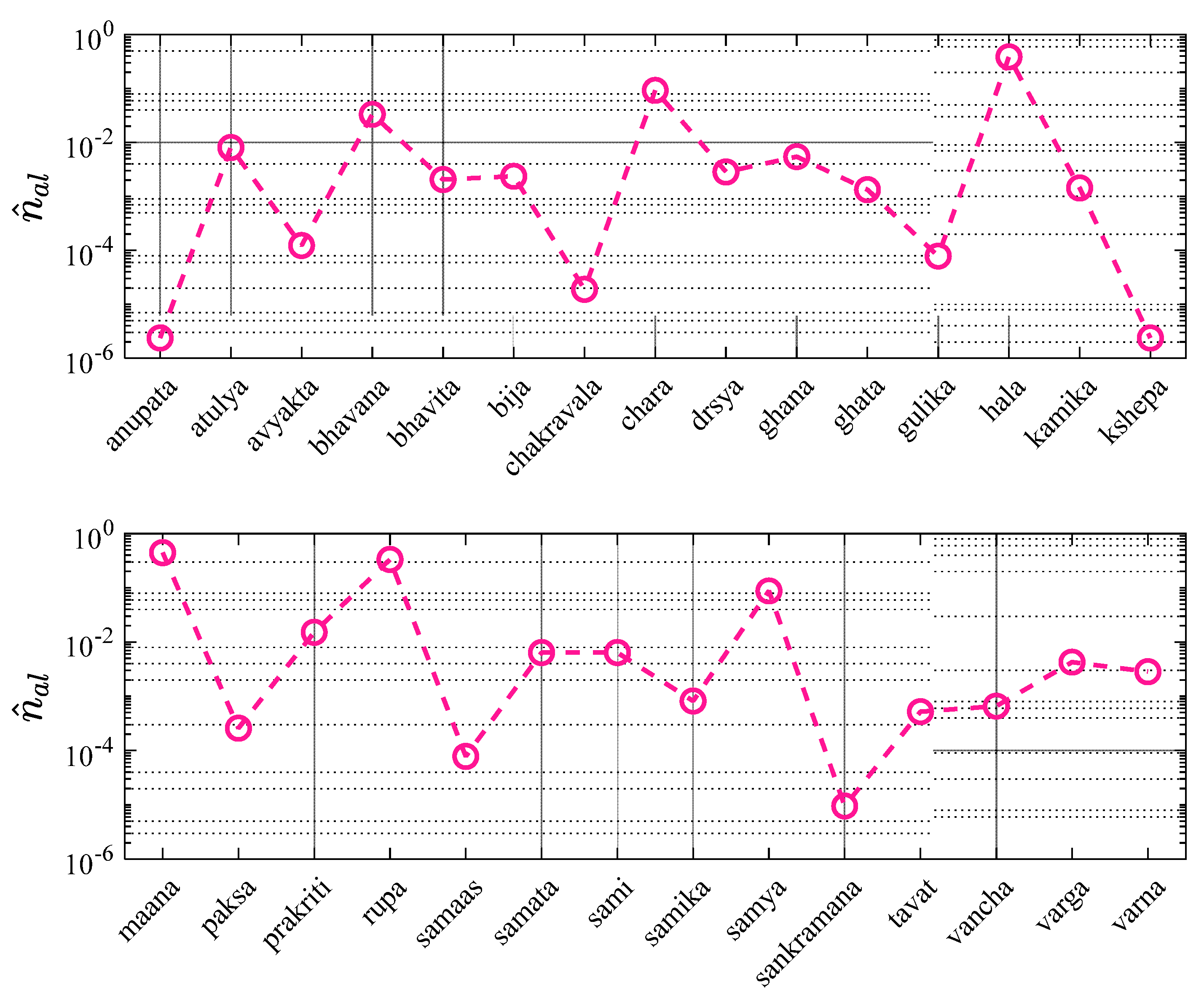

Figure 11 shows that the quantitative evidence of the recurrence of the names based on algebra as presented in

Table 6, from the LI dataset. It presents the specific name recurrence fraction for thirty names based on algebra,

in an alphabetical fashion. As the figure shows, the left axis denotes the name recurrence factor in the LI dataset, which multiplied by a hundred yields ‘recurrence percentage’. This figure evidently demonstrates that

varies between 2.37x10

-6 to 0.44. It is worth noting that the upper bound on

is by far the least, as observed for names based on algebra, although it must be incumbent on the classification of terms between algebra and arithmetic as well. Further, some of the terms with the highest

are ‘

mana’, ‘

hala’, ‘

rupa’, ‘

chara’ and ‘

samya’ with

corresponding to 0.44, 0.38. 0.33, 0.09 and 0.08 respectively. On the other hand, terms like

kshepa, anupata, sankramana, chakravala and

samaas fare very low on the

value. Other terms which occur in the high-frequency range are

bhavana, prakriti, atulya, samataa, sami, ghana, varga etc. – names that can be commonly heard in the Indian setting.

5.6. Mathematics and Mathematicians in the Vedic/Indian Tradition

The incipient stages of mathematics (ganita) and its development witnessed two imbricated schools – that of geometry as well as that of arithmetic and algebra. Incidentally, both of these schools of mathematics were greatly cultivated and nurtured in India. In fact, A Seidenberg, a pre-eminent historian of mathematics traced the origin of advanced mathematics to the Rig-vedic rituals (Seidenberg 1978; Seidenberg 1983). Truly, one of the most primeval texts in mathematics are the shulba-sutras, which are compendiums or handbooks that illustrate the methodology of altar construction for the sacrifices of the Vedic Hindus. At present, only seven shulba-sutras are known: Vadhula shulba, of Baudhayana, Apastamba, Varaha, Manava, Maitrayana from Krsna-Yajur Veda and Katyayana Shulba sutra from Shukla yajur Veda. In ancient India, the construction of fire altars of proper sizes and shapes had to be done with great accuracy for the purpose of sacrifices, and thus arose the problems of geometry, algebra, and arithmetic. This is akin to how the study of astronomy (khagola) in India originated from the need to conduct such Vedic sacrifices at the proper time (Dutta 1932). The pervasiveness of the science of astrology (jyotisha) in India and the preparation of astrological charts (panchanga) by such sound principles, may also be understood in the same context.

In the title ‘shulba-sutra’, ‘sutra’ just refers to an aphorism or a ‘pithy rule’ and is indicative only of the style of the composition, and not the actual content. In fact, Katyayana’s second part of the work titled shulba parishishta (‘Appendix to the Shulba’) and shulbi-kriya (‘The practice of the Shulba’) definitively establishes that the true name of this science of geometry is shulba. Geometry was also oftentimes referred to as ‘Rajju’, meaning a rope or a cord. Etymologically, shulba means ‘to measure’ or an act of measurement, and in the shulbas, the measuring tape is called rajju. One of the connotations of the word Shulba is a line (or a surface) which is the result obtained by measuring, and thus is a later work on Shilpa-shashtras, the surveyor is alluded to as as a sutra-dhara ("rope-holder") or as an expert in alignment (rekha-jna) or one who knows the line (Datta 1932). Not surprisingly, geometry is commonly also referred to as ‘Rekha-ganita’ or jyamiti.

The sulbasutras enunciated a scheme of linear measurement units, based on the magnitudes and proportions of the human body, which later evolved into traditional units that became popular across India. For instance,

14 anus (millet grain size) → 1 angula

3 angulas → 1 parva

12 angulas → 1 pradesha (/vitasti)

15 angulas → 1 pada

24 angulas → 1 aratni (/hasta)

30 angulas → 1 prakrama

96 angulas → 1 danda

120 angulas → 1 purusa

An angula in Sanskrit refers to a finger or a finger’s breadth which is typically identical to fourteen millet grains (anu) or eight barleycorns. Three angulas form a parva, four such parvas constitute a pradeshaor vitasti, i.e., a span and fifteen angulas make a pada. Twice the vitasti is also called an aratnior hastai.e., a cubit. Further, a prakramacomprises of thirty angulas, a danda of ninty-six angulas and one hundred twenty angulas make up a purusa, which is identical to the height of a man. The ancient Indian unit of length, ‘danda’ has been identified equivalent to the modern ‘metre’ (Dongre 1994).

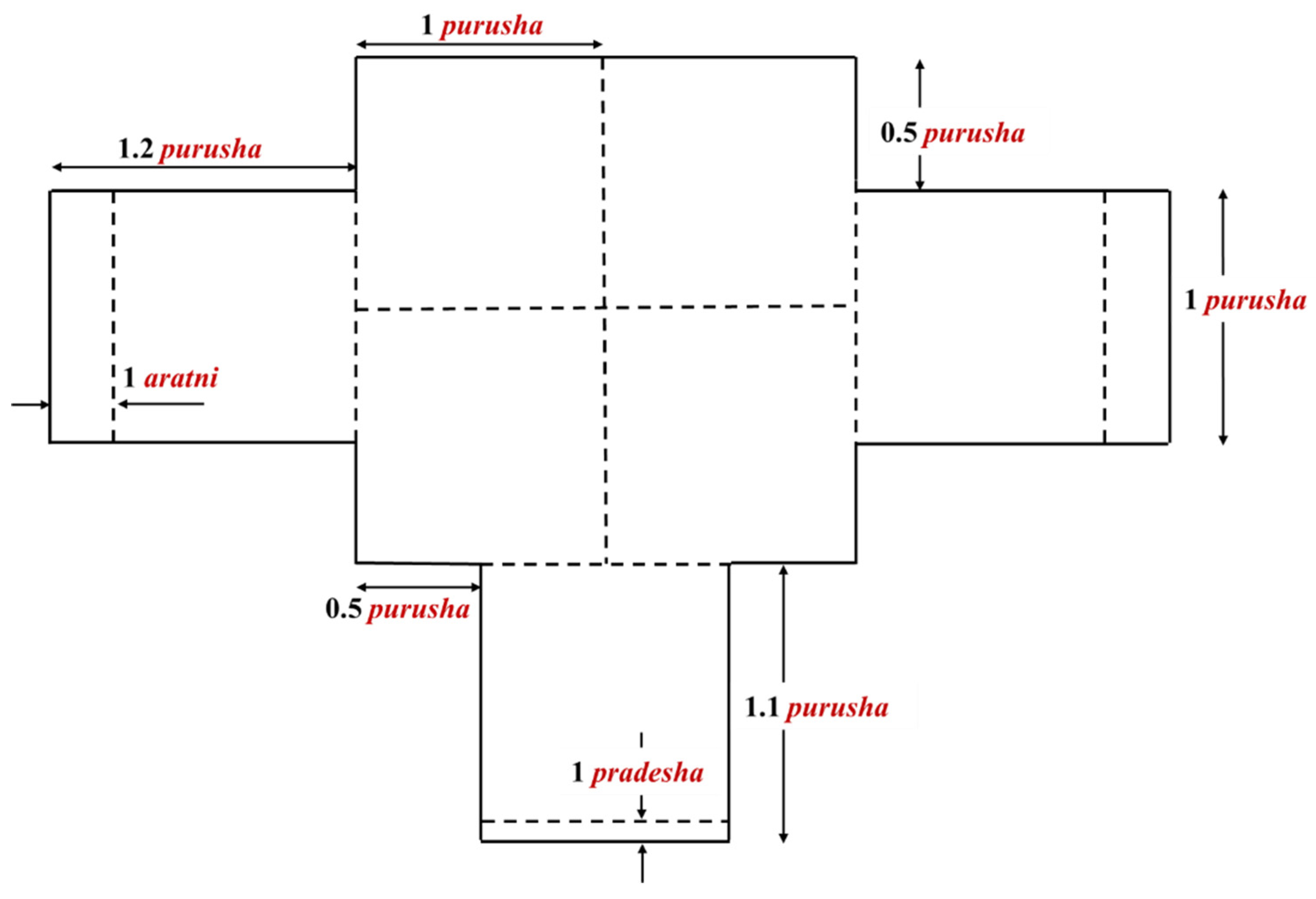

In Vedic India, the accurate construction of the fire altars (

vedior

chiti) for sacrifices required geometrical operations of very complex nature. Among fire altars, the most ancient and primitive one is the

shyena-cit (or the altar of the form of the falcon) having 16 corners (

shroni) which is shown in

Figure 12. The body of this altar consists of four squares of one square

purusaeach, whereas its wings are rectangles of one

purusa by one

purusa and one

aratni (i.e., 1.2

purusa). Its tail comprises of a rectangle of one

purusa by one

purusa and one

pradesha (i.e., 1.1