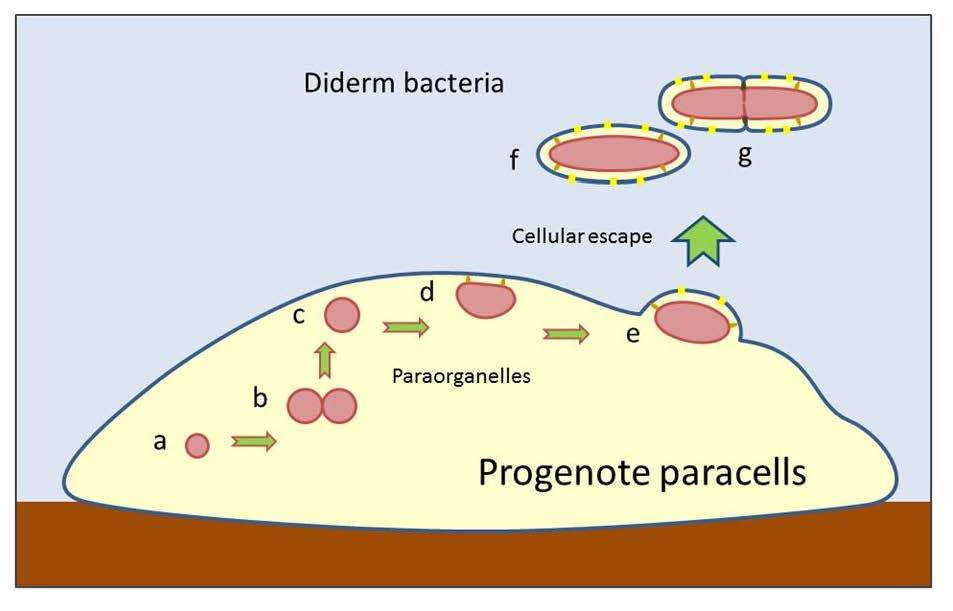

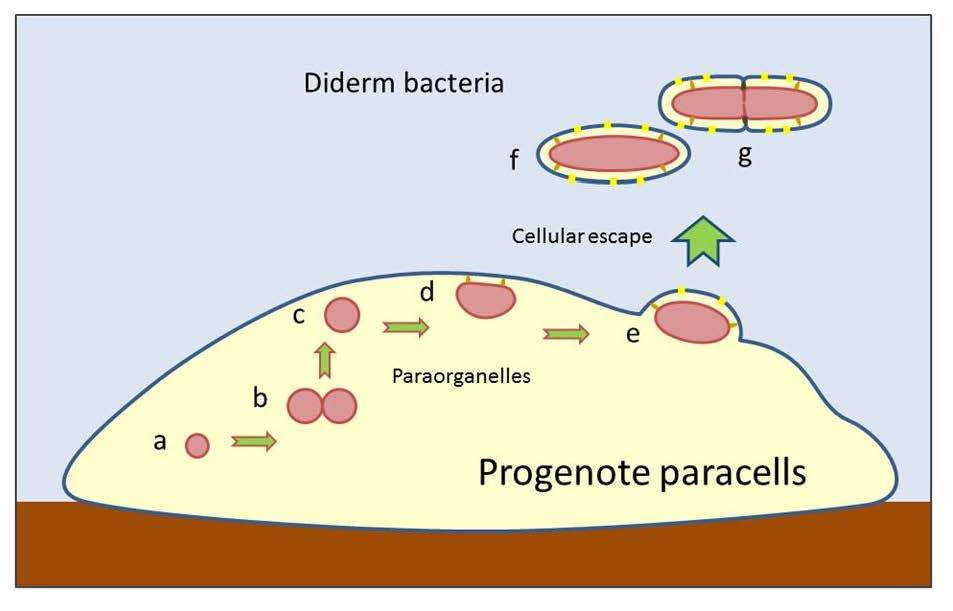

This article reevaluates the Woesean concept of crossing a ‘Darwinian threshold’ from pre-genomic communality, as prevailing in an ancestral ‘progenote’ state, to vertically stable lineages of autonomous and self-similar cells. This transition from collective trunk-line evolution to Darwinian speciation is dependent on the generation of modular organismal genomes. The same general principle should be valid at subcellular levels, allowing the emergence of semi-autonomous genomic agents, such as viruses and plasmid-carrying endogenous vesicles with organelle-like properties. As compartmentalized agents of endogenous nature could start with smaller genomes than those required for fully autonomous cells, it is conjectured that stable subcellular lineages emerged earlier than their cellular counterparts. Referring to the recent ‘pre-endosymbiont hypothesis’, it is proposed that free-living bacteria (the first ‘prokaryote’ cells) arose by ‘lineage escape’ from plasmid-bearing organelle-like compartments, evolving inside the internally complexifying ‘paracells’ of the progenote community. The double-membrane envelopes of diderm bacteria may have resulted from cell-biological processes facilitating cellular lineage escape. The later emergence of archaeal cells (resembling bacteria in ‘prokaryote’ appearance with unichromosomal genomes) and eukaryotic organisms (with compartmented cells and multichromosal genomes) can also be interpreted in terms of this modified progenote hypothesis. Conceivably, the multichromosomal genomes of eukaryotes were bundled in endogenous nuclear compartments to organize a ‘nuclear-cytoplasmic lineage’, which became vertically stable by perfecting mitosis/meiosis-like divisions and yet retained some intra-species population confluence by sexual division-fusion cycles.