1. Introduction

Modern mathematics has organically developed a federated structure. Geometers invoke Hilbert’s axioms or Tarski’s postulates; analysts rely on the ordered-field completeness of the reals; algebraists work with group and ring axioms. When cross-domain reasoning is required—analytic geometry, Galois theory, algebraic topology—mathematicians construct explicit, carefully defined bridges that are built once and reused.

This is not a theoretical proposal. It is a description of observed reality.

Nevertheless, the standard foundational narrative often presents ZFC set theory as the universal substrate: that all mathematical objects are, in principle, sets (formally: every mathematical object is encoded as a set), and that domain-specific axioms are merely shorthand for set-theoretic constructions. This creates a pragmatic gap:

Theory claims: Everything reduces to ZFC.

Practice shows: ZFC is almost never invoked outside of logic and set theory itself.

Theory claims: Incompleteness is a universal fog covering all mathematics.

Practice shows: Most working domains (geometry, finite algebra, elementary analysis) behave as if they are complete and decidable.

Why does this gap exist? We argue that the federated organization of mathematics is a sophisticated response to a deep logical reality. Mathematicians have intuitively partitioned their field to create "Safe Zones"—domains of local decidability—and they resist monolithic reduction because it destroys these local properties.

2. Axiom 1: The Requirement of External Vantage Point

Axiom 1

(Axiom 1 — Domain Separation). A foundational framework should allow stable external vantage points for metareasoning, so meta-level statements need not be modelled within the same object-level universe.

A monolithic ZFC-based framework does not satisfy Axiom 1. Because every object is declared to be a set, metareasoning about ZFC often requires ascending to stronger set theories (large cardinals), creating a hierarchy with no stable external vantage point. In a federated system, we can study Geometry from the vantage point of Algebra, or Arithmetic from the vantage point of Model Theory, without forcing one to be the other.

3. The Logic of Separation: The Decidability Threshold

Why do mathematicians instinctively separate Geometry from Arithmetic? It is not merely a matter of taste. It is a matter of logical safety. We can identify a structural "Litmus Test" that explains these boundaries.

3.1. The Trinity of Danger

Undecidability and incompleteness arise only when a system possesses three specific ingredients simultaneously. We define these formally as the Decidability Threshold:

- 1.

Classical Negation: The ability to assert falsity and rely on classical proof principles sufficient to express provability and negation in the usual sense used in diagonalization arguments.

- 2.

-

Representability (Encoding): The capacity to define a discrete infinite predicate and represent all primitive recursive functions on that predicate.

- 3.

Discrete Unboundedness: An infinite supply of distinct discrete states.

Technical Assumptions: The argument assumes that the theory is recursively axiomatizable (effectively enumerable axioms) and consistent. Under these conditions, a "Wild" theory (possessing all three ingredients) is essentially undecidable.

3.2. Federalism as Quarantine

Mathematical practice organizes itself by managing these ingredients:

Type I (Finite Domains): Boolean Algebra, Finite Groups. They possess Negation and Encoding, but drop Unboundedness. They are trivially decidable.

Type II (Tame Continuous/Linear Domains): Euclidean Geometry, Presburger Arithmetic, Real Closed Fields. They possess Negation and Unboundedness, but they drop Representability. While natural enrichments (e.g., adding arbitrary predicates or the exponential function under certain conditions) can cross into undecidability, the core domains remain decidable via quantifier elimination.

Type III (Wild Domains): Peano Arithmetic, ZFC Set Theory. They possess all three ingredients. They are essentially undecidable.

Mathematicians separate domains to preserve the Tame status of Type I and Type II fields. They intuitively know that mixing Geometry with full Arithmetic (without a controlled bridge) triggers the "Wild" state.

4. The Cost of Reduction: Why We Don’t Use ZFC

The standard doctrine claims that reducing Geometry (or any Tame domain) to ZFC is necessary for "rigor." We argue that it is structurally inefficient.

While it is formally possible to encode Tarski’s geometry into ZFC—and a decidable theory remains theoretically decidable even when embedded in an undecidable one—doing so imposes a substantial Epistemic Overhead. The cost is not that the math stops working, but that we lose the structural guarantees that define the domain.

- 1.

-

Loss of Structural Immunity: In native first-order Euclidean geometry (Tarski’s axiomatization), the syntax restricts us to questions about points, lines, and incidence. Within this scope, every well-formed question has a determinable answer; it is syntactically impossible within the object language to formulate undecidable propositions about Gödel numbering or halting.

When we embed geometry into ZFC, we expose geometric objects to the full expressive power of set theory. We can now formulate questions about geometric points—involving arbitrary set membership, cardinality, or choice functions—that are undecidable. We have moved the object from a "Clean Room," where infection by paradox is impossible, to a "Wild" environment where it must be actively guarded.

- 2.

The Proof-Theoretic Overhead: In the native domain, truth is often algorithmic. For Type I and Type II domains, we determine truth via calculation or decision procedures (e.g., quantifier elimination). In the reduced domain (ZFC), truth is deductive. While ZFC can simulate the geometric algorithm, the default mode of set theory is general proof search. By reducing, we bury the efficient, domain-specific insight under layers of generic set-theoretic machinery. We treat a calculator like a theorem prover.

Mathematicians ignore ZFC in their daily work not because they are imprecise, but because they are efficient. They instinctively maintain the autonomy of their objects to preserve the structural immunities of the domain.

5. Implications for the Consumer: The Warning Label

A crucial distinction must be made between the Mathematician (the builder) and the Scientist (the user).

The Mathematician is an Architect. They build formal structures of varying strength and expressiveness, some designed for specific utility, others for exploring the limits of logic (ZFC). The Scientist is a Tenant looking for a stable place to model reality.

To assist the scientist in navigating this landscape, we provide the following decision procedure:

5.1. The Mirage of Non-Constructive Existence[PDE]

A pervasive source of confusion for the scientific consumer is the conflation of

Mathematical Existence with

Physical Computability. Standard analysis provides powerful theorems—such as the

De Giorgi-Nash Theorem [

1,

2]—which guarantee the existence and regularity (smoothness) of solutions to certain partial differential equations (PDEs).

Crucially, these existence proofs are often Non-Constructive. They prove that a solution exists in the Platonic realm of ZFC sets (typically via compactness arguments or fixed-point theorems that rely on the Axiom of Choice), but they do not provide a Turing machine algorithm to generate the solution from finite initial data.

For a physicist, a solution that "exists" but cannot be computed is operationally indistinguishable from a solution that does not exist. By relying on non-constructive mathematics, scientists may believe their models are physically sound when they are merely logically consistent with axioms that permit infinite information processing (Oracles). The warning label is clear: Existence ≠ Computability.

5.2. The Risk of Using the Wrong Domain

If a physicist accepts the doctrine that "ZFC is the foundation of everything," they are unknowingly importing Type III paradoxes into their physical model.

Example: The Banach-Tarski Paradox. The Banach-Tarski paradox offers a concrete illustration of the risk of using Wild mathematics carelessly. In the usual ZFC framework (which includes the Axiom of Choice), one can prove that a solid 3-dimensional ball can be partitioned into finitely many non-measurable pieces and reassembled to form two balls identical to the original.

1 Such a construction rests crucially on Choice and the existence of highly non-measurable sets, and it conflicts with physical principles like conservation of mass if taken literally.

For applied modeling, the salient issue is whether the idealizations used (pointwise set membership, arbitrary subsets of Euclidean space, and the freedom to choose non-measurable selectors) are physically justified. One can avoid the paradox either by rejecting Choice in favor of regularity axioms (e.g., asserting all relevant sets are Lebesgue measurable) or by restricting modeling to measurability-preserving categories; both choices are legitimate modeling commitments.

6. Bridges Are Explicit, Not Automatic

How do these separate domains communicate? Through Bridges.

Every major cross-domain advance has been an explicit, deliberate construction, not a reduction:

Analytic Geometry: A bridge from Euclidean Space to Field Arithmetic.

Galois Theory: A bridge from Fields to Groups.

Algebraic Topology: A bridge from Spaces to Algebraic Invariants.

6.1. Conservative vs. Non-Conservative Bridges

Not all formal embeddings are equally dangerous. A conservative extension or faithful interpretation that merely rephrases theorems of a tame domain in another language does not change the decidability status of sentences formulated in the original language. If every sentence about geometry provable in ZFC was already provable in the native geometric axioms, decidability for geometric sentences is preserved.

By contrast, a non-conservative encoding that enriches the language available to talk about originally tame objects—for example, by allowing quantification over arbitrary set-theoretic constructions built from geometric points or by naming a new discrete predicate inside a continuous theory—can enable synthetic encodings of computation and thereby create undecidable questions about the objects. The practical prescription is: prefer bridges that are explicitly conservative or whose expressive increase is tightly controlled and documented.

Implicit reduction is risky precisely because it often performs non-conservative encoding silently, escalating privilege without warning.

7. The Federated Organisation We Already Possess

We advocate codifying the structure mathematics has already adopted:

Level 1 — Primary Domain Axiomatizations

The working axioms of each field (Type I and II). These are the daily tools.

Level 2 — Explicit Bridges

Structure-preserving translations defined when required.

Level 3 — The Wild Reserve (ZFC)

A designated "Wild" domain (Type III) used for studying infinity, cardinality, and consistency strength. It is a valuable laboratory, not a universal basement.

Modern proof assistants (Lean/mathlib, Coq) have effectively implemented this. They use modular libraries where imports are explicit and distinct. For example, `mathlib` treats real analysis through ordered field axioms and topological structures, rather than forcing a universal encoding into set theory at every step [

5]. If monolithic reduction were optimal, these systems would funnel everything through ZFC sets. They do not; they choose federalism for scalability and logical hygiene.

8. Objections and Replies

Objection 1 — "ZFC is useful as a universal lingua franca; abandoning it risks fragmentation."

Reply: ZFC remains an invaluable laboratory for set-theoretic inquiry and for comparing relative consistency strengths. This paper does not propose abandoning ZFC as a research domain; it recommends treating ZFC as a designated Wild reserve rather than the default operational substrate for every applied domain. Explicit, well-documented bridges preserve interoperability while protecting local decidability.

Objection 2 — "Embedding a decidable theory into an undecidable one does not automatically make the original problems undecidable."

Reply: Correct—conservative embeddings preserve decidability for sentences in the original language [

5]. The risk arises when the host theory’s extra expressive resources are used to formulate new predicates or quantifications about the original objects (for instance, naming a discrete subset or quantifying over arbitrary set constructions). Such implicit enrichments are the common source of accidental privilege escalation.

Objection 3 — "Constructive or non-classical logics evade these limitations."

Reply: While constructive frameworks change some formal properties (e.g., the role of excluded middle), once sufficient arithmetic is interpretable the essential limitations reappear in adapted form. The Decidability Threshold emphasizes the structural features that enable encoding of computation; changing the proof calculus shifts technicalities but not the core need for caution.

Objection 4 — "Reverse mathematics already provides a fine-grained map of required axioms."

Reply: Exactly—reverse mathematics and proof-theoretic calibration are complementary to the federalist prescription. They help identify minimal bridges: import only the subsystem needed for the target theorems [

6]. Reverse mathematics provides recipes for which subsystems to import when a particular theorem is needed (e.g., many classical analysis results are equivalent to

or

), so use these calibrations to select minimal bridges. The paper’s recommendation is operational: prefer minimal, explicit, and conservative imports informed by such calibrations.

Objection 5 — "Category theory or univalent foundations already provide a non-set-theoretic federation."

Reply: Indeed—homotopy type theory and categorical approaches offer alternative federated architectures [

7,

8]. The argument here is largely agnostic about the specific metalanguage; the key is rejecting

implicit universal reduction in favor of explicit, controlled connections.

9. Conclusions: Codifying Implicit Wisdom

Mathematics has already chosen federalism. The evidence is in the autonomy of its fields, the explicit nature of its bridges, and the intuitive separation of Tame and Wild domains.

The contribution of this paper is to provide the structural explanation for this behavior:

- 1.

Domains separate to preserve the Decidability Threshold (avoiding the Trinity of Danger).

- 2.

Reduction to ZFC is avoided because it imposes an unnecessary Epistemic Overhead.

- 3.

This separation protects the Consumer (Science) from inheriting logical paradoxes irrelevant to physical reality.

We should stop teaching students that mathematics is a precarious tower resting on a single infinite foundation. Instead, we should teach them the architecture of the Federation: a robust network of safe, decidable domains connected by strong, explicit bridges.

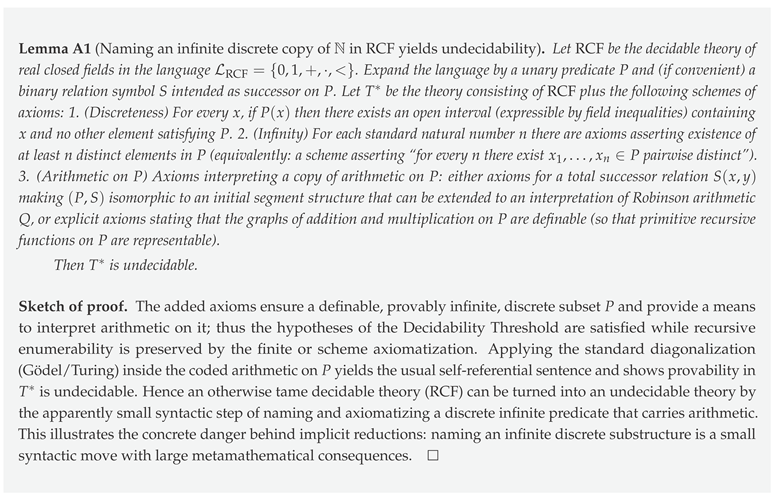

Appendix A. Appendix: Formalizing the Decidability Threshold

Proposition A1

(Formalized Decidability Threshold). Let T be a first-order theory in classical logic that is recursively axiomatizable (the axioms are recursively enumerable) and consistent. Suppose (i) T interprets Robinson arithmetic Q (or equivalently, contains a definable predicate on which all primitive recursive functions are representable); and (ii) for each standard natural number n (coded in the meta-language) T proves there exist in N with for (i.e., N is provably infinite). Then the set of sentences provable in T is undecidable: there is no algorithm that, given an arbitrary sentence φ in the language of T, decides whether .

Proof sketch Recursive axiomatizability together with representability yields an effective internal coding of syntax and a formula expressing the proof predicate; provably infinite discrete

N supplies the definable domain necessary for diagonalization; classical logic allows the usual inferences about negation and provability. Hence one can construct a self-referential sentence asserting its own non-provability, and the standard Gödel/Turing diagonal argument shows that decidability of provability in

T would yield a decision procedure for known undecidable sets (contradiction). See [

9,

10,

11] for full formal details and variants. □

Commentary: Mapping the Lemma to Modeling Mistakes

The lemma above is not a mere formal curiosity: it captures a recurring class of modeling errors. In practice, these errors take the following forms:

First, implicitly assuming the availability of arbitrary choice or selector functions (for example, “choose one representative from each equivalence class”) is equivalent to enriching the language of the model with new names or predicates that can encode discrete choices; this is the same move as adding a predicate P naming distinct points.

Second, introducing a mechanism to count, index, or enumerate otherwise continuous objects (for instance, by postulating a distinguished sequence of points or a labeled grid) is exactly the step that produces a definable copy of and allows arithmetic to be interpreted. Both moves are syntactic: they change the expressive power of the theory even if the unchanged, original formulas about the continuous domain look the same.

References

- De Giorgi, E. Sulla differenziabilità e l’analiticità delle estremali degli integrali multipli regolari. Memorie della Accademia delle Scienze di Torino. Classe di Scienze Fisiche, Matematiche e Naturali 1957, 3, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, J. Continuity of solutions of parabolic and elliptic equations. American Journal of Mathematics 1958, 80, 931–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, S.; Tarski, A. Sur la décomposition des ensembles de points en parties respectivement congruentes. Fundamenta Mathematicae 1924, 6, 244–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagon, S. The Banach–Tarski Paradox; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Montague, R. Deterministic Theories and Interpretations; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Feferman, S. What rests on what? The proof-theoretic analysis of mathematics. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th International Congress of Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Voevodsky, V. The Origins and Motivations of Univalent Foundations. The Institute Letter, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Lane, S. Categories for the Working Mathematician; Springer, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gödel, K. Über formal unentscheidbare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme I. Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik 1931, 38, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Series 2 1936, 42, 230–265. [Google Scholar]

- Tarski, A.; Mostowski, A.; Robinson, R.M. Undecidable Theories; North-Holland, 1953. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

The Banach–Tarski theorem depends crucially on the Axiom of Choice (or equivalent forms producing non-measurable sets); see [ 3] and [ 4]. In frameworks that forbid the requisite non-measurable sets (for example by adopting regularity/measure axioms or by working within tame real-closed-field based modeling plus explicit measurability hypotheses), the paradoxical decomposition cannot be carried out and the theorem has no force for physical modeling. Note this is a genuine foundational trade-off: rejecting Choice to block Banach–Tarski removes certain familiar set-theoretic conveniences and alters what can be proved, so the choice between Choice and regularity axioms is a deliberate modeling decision with consequences. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).