Submitted:

02 February 2026

Posted:

03 February 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

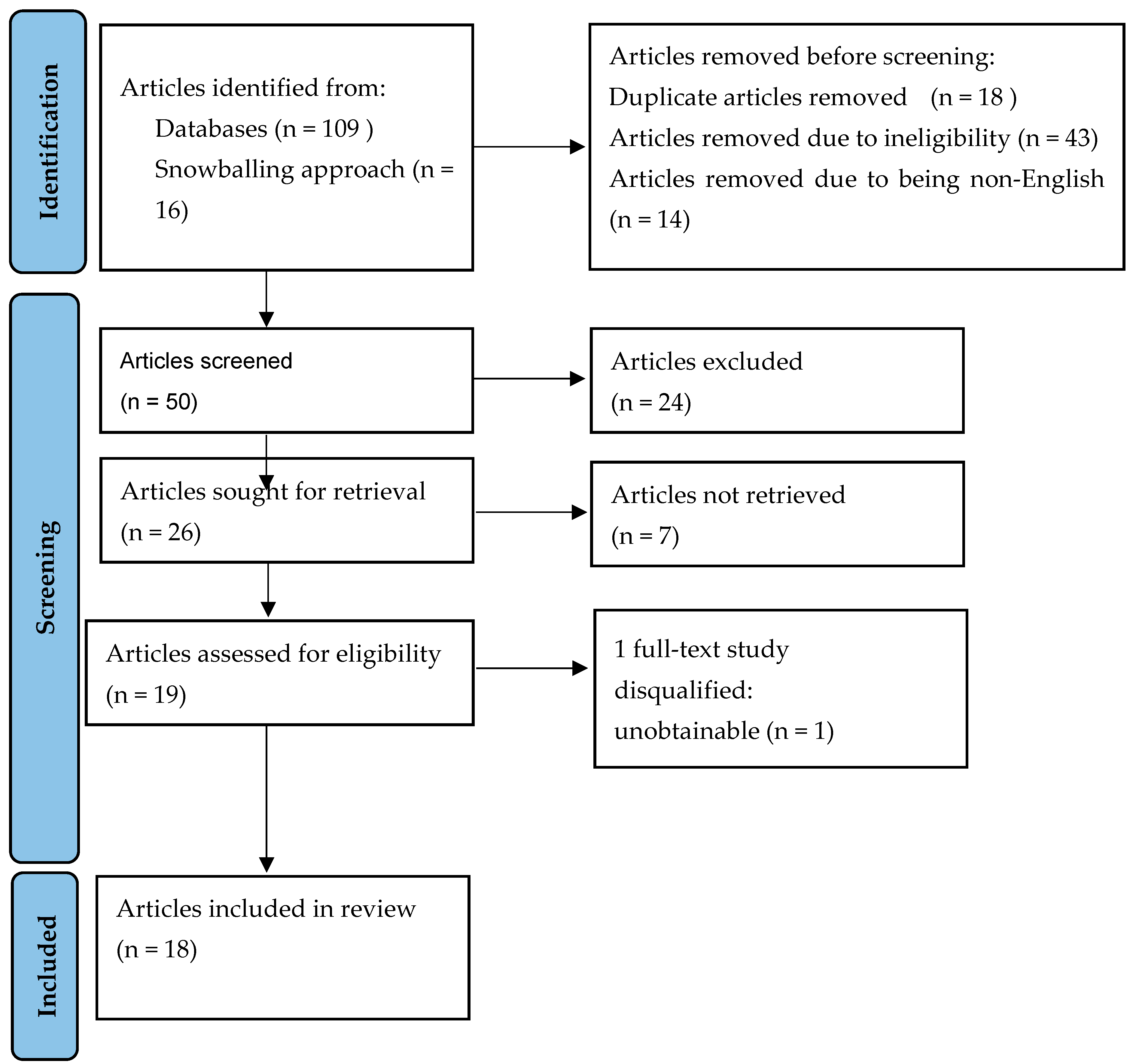

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

- i.

- Phase 1: Research question identification

- ii.

- Phase 2: Relevant articles identification

- iii.

- Phase 3: Study selection

- iv.

- Phase 4: Data charting

- v.

- Phase 5: Compiling, summarising and writing the research results.

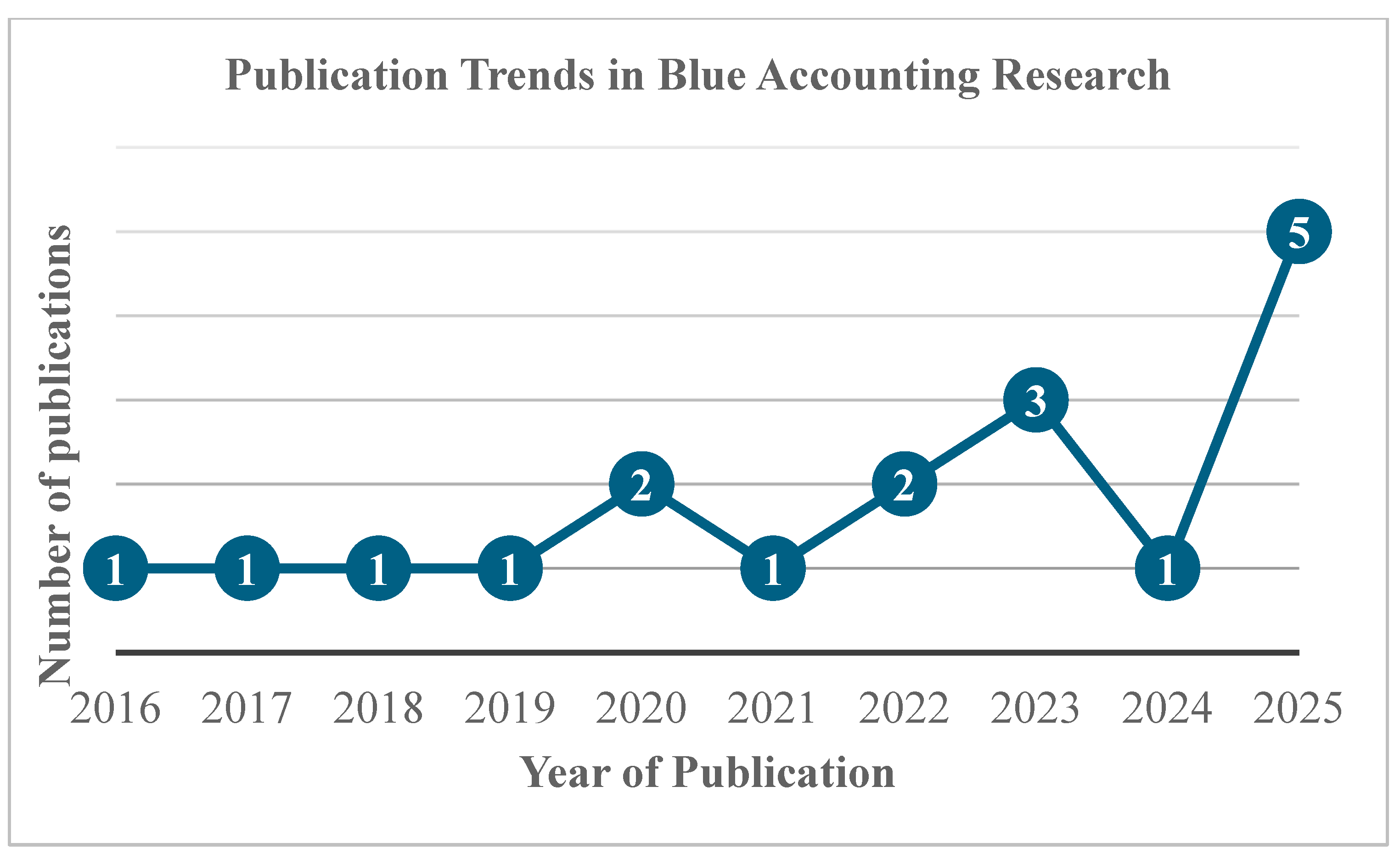

3. Results

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Review of Chosen Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abreu, R., David, F., Santos, L. L., Segura, L., & Formigoni, H. (2017). Blue accounting: First insights. 16th International Conference on Corporate Social Responsibility and 7th Organisational Governance Conference, Buxton, United Kingdom, August 30th-Sept. 1st, 2017,.

- Abreu, R.; David, F.; Santos, L.L.; Segura, L.; Formigoni, H. (2019). Blue Accounting: Looking for a New Standard. Responsibility and Governance: The Twin Pillars of Sustainability, 27-43.

- Adam, I.H.D.; Jusoh, A.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Nor, K.M. Scoping research on sustainability performance from manufacturing industry sector. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2019, 17, 134–146. [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, A.O.; Yusheng, K.; Twum, A.K.; Ayamba, E.C.; Kongkuah, M.; Musah, M. Trend and relationship between environmental accounting disclosure and environmental performance for mining companies listed in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 12192–12216. [CrossRef]

- Alqudhayeb, N. J. A. (2025). Synthesising prior research on blue accounting, MFCA, ABC, and public health: toward an integrated water governance framework for fragile states. Proceeding of International Students Conference of Economics and Business Excellence,.

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, K.; Glendinning, C.; Clarke, S. Making informed choices in social care: the importance of accessible information. Heal. Soc. Care Community 2007, 16, 197–207. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S.J.; Biswas, P.K.; Wellalage, N.H.; Man, Y. Environmental disclosure and its relation to waste performance. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 31, 1545–1577. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Cadenas, M.D.; Loiseau, C.; Reimer, J.M.; Claudet, J. Tracking changes in social-ecological systems along environmental disturbances with the ocean health index. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 841, 156423. [CrossRef]

- Colgan, C.S. Measurement of the Ocean Economy From National Income Accounts to the Sustainable Blue Economy. J. Ocean Coast. Econ. 2016, 2, 12. [CrossRef]

- Datt, R.R.; Luo, L.; Tang, Q. Corporate voluntary carbon disclosure strategy and carbon performance in the USA. Account. Res. J. 2019, 32, 417–435. [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C., Hsiao, P.-C. K., & Maroun, W. (2020). Introduction to the Routledge Handbook of Integrated Reporting: An overview of integrated reporting and this book, which entails different perspectives on a maturing field and a framework for future research. The Routledge handbook of integrated reporting, 1-14.

- Dinh, T.; Husmann, A.; Melloni, G. Corporate Sustainability Reporting in Europe: A Scoping Review. Account. Eur. 2022, 20, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Elshabasy, Y.N. The impact of corporate characteristics on environmental information disclosure: an empirical study on the listed firms in Egypt. 2018, 12. [CrossRef]

- Failler, P.; Liu, J.; Lallemand, P.; March, A. Blue Accounting Approaches in the Emerging African Blue Economy Context. J. Sustain. Res. 2023, 5. [CrossRef]

- Failler, P., & Seisay, M. (2021). Information Note on Blue Accounting in the Context of African Union Blue Economy Strategy.

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman.

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Barroso-Méndez, M.J.; Pajuelo-Moreno, M.L.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Performance: A Meta-Analytic Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1115. [CrossRef]

- Herbert-Read, J.E.; Thornton, A.; Amon, D.J.; Birchenough, S.N.R.; Côté, I.M.; Dias, M.P.; Godley, B.J.; Keith, S.A.; McKinley, E.; Peck, L.S.; et al. A global horizon scan of issues impacting marine and coastal biodiversity conservation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 1262–1270. [CrossRef]

- Hora, M.; Subramanian, R. Relationship between Positive Environmental Disclosures and Environmental Performance: An Empirical Investigation of the Greenwashing Sin of the Hidden Trade-off. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 23, 855–868. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Zhang, Y.; Kumar, A.; Zavadskas, E.; Streimikiene, D. Measuring the impact of renewable energy, public health expenditure, logistics, and environmental performance on sustainable economic growth. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 833–843. [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, S.; Mann, B.; Sink, K.; Adams, R.; Livingstone, T.-C.; Mann-Lang, J.; Pfaff, M.; Samaai, T.; van der Bank, M.; Williams, L.; et al. Evaluating the evidence for ecological effectiveness of South Africa’s marine protected areas. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 43, 389–412. [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.-Y.; Salminen, J.; Jäppinen, J.-P.; Koljonen, S.; Mononen, L.; Nieminen, E.; Vihervaara, P.; Oinonen, S. Bridging the gap between ecosystem service indicators and ecosystem accounting in Finland. Ecol. Model. 2018, 377, 51–65. [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Stegeman, J.J.; Fleming, L.E.; Allemand, D.; Anderson, D.M.; Backer, L.C.; Brucker-Davis, F.; Chevalier, N.; Corra, L.; Czerucka, D.; et al. Human Health and Ocean Pollution. Ann. Glob. Heal. 2020, 86, 151. [CrossRef]

- Larasasti, S.; Amalia, P.N.; Santika, I.; Putri, A.; Crisanta, F.; Arnita, V. The Relationship Between Blue Accounting, Marine Policy and Climate Change To The Sustainability Of Marine Ecosystems. J. Environ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; dos Santos, K.B.; Pap, R. Practical Guidance for Knowledge Synthesis: Scoping Review Methods. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 287–294. [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, T.G.; Du Plessis, N.; Findlay, K. Into the blue – The blue economy model in Operation Phakisa ‘Unlocking the Ocean Economy’ Programme. South Afr. J. Sci. 2022, 118. [CrossRef]

- Lubchenco, J., & Haugan, P. M. (2023). National Accounting for the Ocean and Ocean Economy. In The Blue Compendium: From Knowledge to Action for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (pp. 279-307). Springer.

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Nicolò, G.; Zanellato, G. Ensuring More Sustainable Reporting in Europe Using Non-Financial Disclosure—De Facto and De Jure Evidence. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1162. [CrossRef]

- Maramba, I.; Chatterjee, A.; Newman, C. Methods of usability testing in the development of eHealth applications: A scoping review. Int. J. Med Informatics 2019, 126, 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Matenda, F.R.; Sibanda, M.; Chikodza, E.; Gumbo, V. Bankruptcy prediction for private firms in developing economies: a scoping review and guidance for future research. Manag. Rev. Q. 2021, 72, 927–966. [CrossRef]

- Matz, C.J.; Egyed, M.; Hocking, R.; Seenundun, S.; Charman, N.; Edmonds, N. Human health effects of traffic-related air pollution (TRAP): a scoping review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Moozanah, S.; Rusdiansyah, N.; Rosyidah, D.M.; Riany, M. Profit and Sustainability Perceptions Related to the Implementation of Blue Accounting in the Fishing Industry in Palabuhanratu. J. Account. Audit. Bus. 2024, 7, 36–43. [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC medical research methodology, 18, 1-7.

- Mvunabandi, J.D. Scholarly Discourse of Remote Forensic Auditing and Fraud Schemes in Remote Workforce: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Appl. Res. Bus. Manag. 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, K. K., Andeb, J. O., & Ogenyi, P. D. M. A. (2025). An Integrated Reporting Approach to Blue Accounting. Journal of Accounting and Financial Management, 11(6), 20.

- Pattinaja, E. M., Abrahamsz, J., & Loppies, L. R. (2023). Blue economy accounting model for tuna fisher groups in Maluku Province, Indonesia. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation, 16(4), 2060-2071.

- Perkiss, S.; McIlgorm, A.; Nichols, R.; Lewis, A.R.; Lal, K.K.; Voyer, M. Can critical accounting perspectives contribute to the development of ocean accounting and ocean governance?. Mar. Policy 2022, 136. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [CrossRef]

- Pita, C.; Pierce, G.J.; Theodossiou, I.; Macpherson, K. An overview of commercial fishers’ attitudes towards marine protected areas. Hydrobiologia 2011, 670, 289–306. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; Campbell, P.; Struthers, C.; Synnot, A.; Nunn, J.; Hill, S.; Goodare, H.; Morris, J.; Watts, C.; Morley, R. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Davies, E.L.; Peters, M.D.J.; Tricco, A.C.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; Munn, Z. Undertaking a scoping review: A practical guide for nursing and midwifery students, clinicians, researchers, and academics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2102–2113. [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rahmayanti, A.Y.; Sari, D.K. Blue Accounting to Enhance the Quality of Sustainability Report. International Conference on Vocational Education Applied Science and Technology. p. 69.

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 31, 1497–1517. [CrossRef]

- Piao, R.S.; Scalco, A.R.; Vazquez-Brust, D.; Plaza-Ubeda, J.A.; Cortés, M.E.T. Guest editorial: The UN sustainable development goals and management theory and practice. RAUSP Manag. J. 2022, 57, 358–361. [CrossRef]

- Stafford, W., Russo, V., Oelofse, S., Godfrey, L., & Pretorius, A. (2022). Reducing Plastic Pollution: A comprehensive evidence-based strategy for South Africa.

- Stefannie, D., & Irwansyah, F. N. K. (2025). Blue Accounting Practices for Marine Economic Sustainability: A Descriptive Analysis of the Implementation of Blue Accounting in the Fisheries Sector in West Kutai Regency. American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR), 9(6), 218-225.

- Struwig, M.; Berg, A.V.D.; Hadi, N. Challenges in the ocean economy of South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 2023, 41, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Syah, S., Saraswati, E., & Sukoharsono, E. G. (2020). Blue Accounting and Sustainability. 23rd Asian Forum of Business Education (AFBE 2019),.

- Udo, E. J. (2019). ENVIRONMENTAL ACCOUNTING DISCLOSURE PRACTICES IN ANNUAL REPORTS OF LISTED OIL AND GAS COMPANIES IN NIGERIA. International Journal of Accounting & Finance (IJAF), 8(1).

- Warkula, Y.Z.; Mediaty; Damayanti, R.A. Application of Blue Accounting and Sustainability Accounting in Pearl Cultivation Company Commanditaire Vennootschap (CV) Mairang Jabulenga Village, Aru Islands. J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 2024, 5, e02099–e02099. [CrossRef]

- Winarsih; Fuad, K.; Setyawan, H. Blue Accounting of the Marine Knowledge and Sustainable Seas: A Conceptual Model. Conference on Complex, Intelligent, and Software Intensive Systems. Australia; pp. 954–958.

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2017, 39, 93–112. [CrossRef]

- Yasar, B.; Martin, T.; Kiessling, T. An empirical test of signalling theory. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 43, 1309–1335. [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155. [CrossRef]

| Author(s) and (year) of publication | Findings |

Journal/Book/Series/ Chapter |

Title of the paper/article | Location |

| Failler et al. (2023) | Blue accounting provides an assessment of actions against climate change. There is no uniform accounting framework for blue accounting. The data necessary for blue accounting are scattered. Blue accounting can enhance the sustainability of the operations (conservation and sustainable consumption). Blue accounting reflects value for measuring the cost of degradation and destruction. Producing accurate data for blue accounting is difficult, especially in integrating social, economic, and ecological aspects. The legal framework/laws and regulations governing the marine space affect the adoption /non-adoption of blue accounting. |

Journal of Sustainability Research | Blue accounting approaches in the emerging African blue economy context. | Africa |

| Rahmayanti & Sari (2023) | The availability/adequacy of data for blue accounting disclosures determines whether they are adopted. The urgent need for ocean sustainability (to meet the needs of current and future generations) could accelerate the adoption of blue accounting disclosures. The achievement of SDG Goal 14 (Life Below Water) could encourage the adoption of blue accounting disclosure. The lack of a clear framework for blue accounting may hinder the adoption of blue accounting disclosure. |

Conference Proceedings (The 5th International Conference on Vocational Education, Applied Science and Technology: 2022). | Blue accounting to enhance the quality of the sustainability report. | Indonesia |

| Syah et al. (2020) | Blue accounting adoption enhances the consideration of the sustainable use of marine resources in the present and future generations. Stakeholders interested in marine ecosystems put pressure on information relating to the organisation's marine practices and their sustainability. Blue accounting adoption improves the organisation’s environmental accounting. |

Conference Proceedings: 23rd Asian Forum of Business Education | Blue accounting and sustainability | Indonesia |

| Failler & Seisay (2021) | Blue accounting can serve as a tool to assess the effectiveness of climate change actions. Government incentives, such as grants or ocean-based financing (e.g., blue bonds), could encourage marine sustainability. There is no uniform international/national framework for blue accounting, resulting in the necessary disclosure information being unavailable or incomplete. |

African Union Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources (AU-IBAR) Information note | Information Note on Blue Accounting in the Context of African Union Blue Economy Strategy | Africa |

| Abreu et al. (2017) | Blue accounting may assist in meeting stakeholders' information needs regarding the marine ecosystem and the effects of the organisation’s operations. There is a lack of accounting and marine knowledge. A regulatory framework that enforces blue accounting might accelerate blue accounting disclosure adoption. |

Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Corporate Social Responsibility and 7th Organisational Governance Conference | Blue accounting: First insights | Broad, including Europe |

| Abreu et al. (2019) | Blue accounting disclosures could satisfy stakeholders' information needs regarding the marine ecosystem and the effects of the organisation’s operations. The adoption might provide more knowledge about the marine ecosystem and how it interfaces with the entity’s operations. A regulatory framework that enforces blue accounting might accelerate blue accounting disclosure adoption. |

Responsibility and Governance: The Twin Pillars of Sustainability | Blue accounting: Looking for a new standard. | Europe |

| Winarsih et al. (2020) | The stakeholders' information needs regarding the marine ecosystem and its impact on the organisation’s operations may influence the organisation’s adoption of blue accounting. The organisation might legitimise its operations through blue accounting disclosures. Blue accounting adoption may be valuable to stakeholders and organisations seeking a deeper understanding of the marine ecosystem. The lack of a specific international accounting standard for blue accounting weakens the reliability and comparability of its data. The complexity of marine and maritime resources, as well as the ability to properly decipher which data is relevant for blue accounting, may pose a limitation to the adoption of blue accounting. |

Complex, Intelligent, and Software Intensive Systems: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Complex, Intelligent, and Software Intensive Systems (CISIS-2019). | Blue accounting of the marine knowledge and sustainable seas: A conceptual model. | The research was not conducted in a specific marine region. |

| Pattinaja et al. (2023) | The organisation's desire to identify the positive and negative environmental effects of its operations in the marine space might influence its adoption of blue accounting disclosures. | Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation | Blue economy accounting model for tuna fisher groups in Maluku Province, Indonesia | Indonesia |

| Perkiss et al. (2022). | Perceiving ocean accounting as a means to measure the organisation’s progress towards attaining the SDGs might influence the adoption of blue accounting disclosure. Initiatives to develop an accounting system grounded in accounting principles and processes focused on measuring marine facets might influence the adoption of blue accounting disclosures. Pursuing effective ocean governance based on the results/information from ocean accounting might influence the adoption of blue accounting disclosure. |

Marine Policy | Can critical accounting perspectives contribute to the development of ocean accounting and ocean governance? | The research was not conducted in a specific marine region. |

| Lai et al. (2018) | There is a lack of an accounting framework that comprehensively accounts for the various factors of the marine ecosystem. There is a lack of availability of relevant, up-to-date data, thus limiting methodological consistency and accuracy when evaluating and accounting for marine ecosystem sustainability. |

Ecological Modelling | Bridging the gap between ecosystem service indicators and ecosystem accounting in Finland |

Finland |

| Loureiro et al. (2022) | The adoption would involve a multidisciplinary collaboration, as it requires integrating information from various sources to account for environmental, economic, and social factors, and utilising several established and tested accounting systems, which may lead to reluctance to adopt. Blue accounting information output provides the necessary information for sustainable development. The adoption would provide the information necessary to facilitate effective decision-making, ocean governance, and policy development. Adoption would enable ocean monitoring and assessment. Blue accounting adoption would fast-track the creation of a consistent, standardised, and holistic framework that integrates social, environmental, and economic data. The adoption would facilitate the tracking and reporting on the achievement of SDGs. |

Journal of Marine Science | Every account counts for sustainable development: lessons from the African CoP to implement ocean accounts in the Western Indian Ocean region |

Western Indian Ocean |

| Colgan (2016) | This would provide small islands, which are mainly composed of ocean, with valuable information for decision-making about their economies and livelihoods. The required capacity to undertake the necessary measurements for blue accounting may affect its adoption. |

Journal of Ocean and Coastal Economics | Measurement of the ocean economy from national income accounts to the sustainable blue economy | Not applicable |

| Warkula & Damayanti (2025) | This would provide organisations with a means to align their operations with societal norms and expectations. This would also enable sustainable maintenance of the marine ecosystem. This would enable the effective protection and preservation of this valuable economic asset, the sea. This would provide valuable marine-related information to organisations and the public, enabling them to identify, measure, evaluate, and report on blue economic growth. This would support and enable the assessment of progress toward SDG 14. |

Journal of Lifestyle and SDGs Review | Application of Blue Accounting and Sustainability Accounting in Pearl Cultivation Company Commanditaire Vennootschap (CV) Mairang Jabulenga Village, Aru Islands | Aru Islands |

| Moozanah et al. (2024) | The adoption would facilitate the tracking and reporting on the achievement of SDG 14. The adoption would ensure sustainable fishing practices that prevent over-exploitation. The adoption would create a balance between economic profit and environmental sustainability. This would also enable an effective shift from financial-focused accounting to an accounting framework that encompasses social and environmental impacts when using marine resources. This would facilitate the availability of information, increasing public and organisational awareness of marine ecosystem management. The lack of knowledge or education on blue accounting hinders its effective implementation. |

Journal of Accounting Auditing and Business | Profit and Sustainability Perceptions Related to the Implementation of Blue Accounting in the Fishing Industry in Palabuhanratu | Palabuhanratu |

| Larasasti, et al. (2025) | This would enhance the measurement of the economic, social and environmental value of marine ecosystems. This would encourage environmentally sound business practices and increase transparency in marine resource management. Adoption would encourage organisations to gain societal acceptance, thereby legitimising their stance. This promotes a competitive advantage for organisations by improving their productivity and customer preference. This would provide evidence-based data to support enhanced decision-making. This would help reduce environmental problems and contribute to reporting on environmental sustainability. The adoption is hindered by weak law enforcement and poorly designed policies. The lack of a standardised reporting framework to guide calculations, presentations, and disclosures of blue accounting under financial standards limits its widespread and consistent adoption. |

Journal of Environmental Economics and Sustainability | The Relationship Between Blue Accounting, Marine Policy and Climate Change to the Sustainability of Marine Ecosystems | Not applicable |

| Alqudhayeb (2025) | This would enable evidence-based policy making and improve intersectoral coordination. Improves national environmental accountability and sustainable development goals. Adoption would encourage organisations to gain societal acceptance, thereby legitimising their stance. Blue accounting would enable consistent monitoring and compliance with marine-related regulations. The scattered data and inconsistent reporting hinder the effective implementation of blue accounting disclosures. |

Proceeding of International Students Conference of Economics and Business Excellence | Synthesizing prior research on blue accounting, MFCA, ABC, and public health: toward an integrated water governance framework for fragile states | Not Applicable |

| Nwachukwu et al. (2025) | The adoption would improve corporate governance and sustainable performance. This would serve as a catalyst for a worldwide blue economy. Adoption would encourage organisations to gain societal acceptance, thereby legitimising their stance. The lack of a clear, transparent accounting disclosure framework leads to bluewashing and undermines market confidence. Inadequate blue accounting corporate reporting fails to capture the complex relationships between business activities and ecosystem health. The jurisdictional and regulatory challenges faced by multinational companies require adherence to diverse national and regional regulations while also meeting international standards, which poses a significant challenge. The current financial and sustainability reporting standards, such as IFRS S1 and GRI 304, lack specific guidance on ocean-related topics. The cost and complexity of establishing comprehensive blue accounting disclosure may pose barriers for smaller companies. Blue accounting measurement challenges due to the relativity of ocean-related sustainability metrics, which vary significantly by region/ecosystem type, pose a challenge to organisations providing these disclosures. The complexity of marine ecosystem interactions makes it challenging to isolate corporate-specific impacts, leading to reluctance in blue accounting disclosures. |

Journal of Accounting and Financial Management | An Integrated Reporting Approach to Blue Accounting | Not Applicable |

| Stefannie, et al. (2025) | This would help reduce environmental problems and contribute to reporting on environmental sustainability. Limited monitoring frequency and data availability hinder comprehensive time series data collection, which would enable effective blue accounting. The lack of knowledge or education on blue accounting hinders its effective implementation. The lack of capacity or human resources hinders the effective implementation of blue accounting. The adoption would facilitate the tracking and reporting on the achievement of SDG 14. |

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) | Blue Accounting Practices for Marine Economic Sustainability: A Descriptive Analysis of the Implementation of Blue Accounting in the Fisheries Sector in West Kutai Regency |

West Kutai Regency (Indonesia) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.