Submitted:

27 January 2026

Posted:

28 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

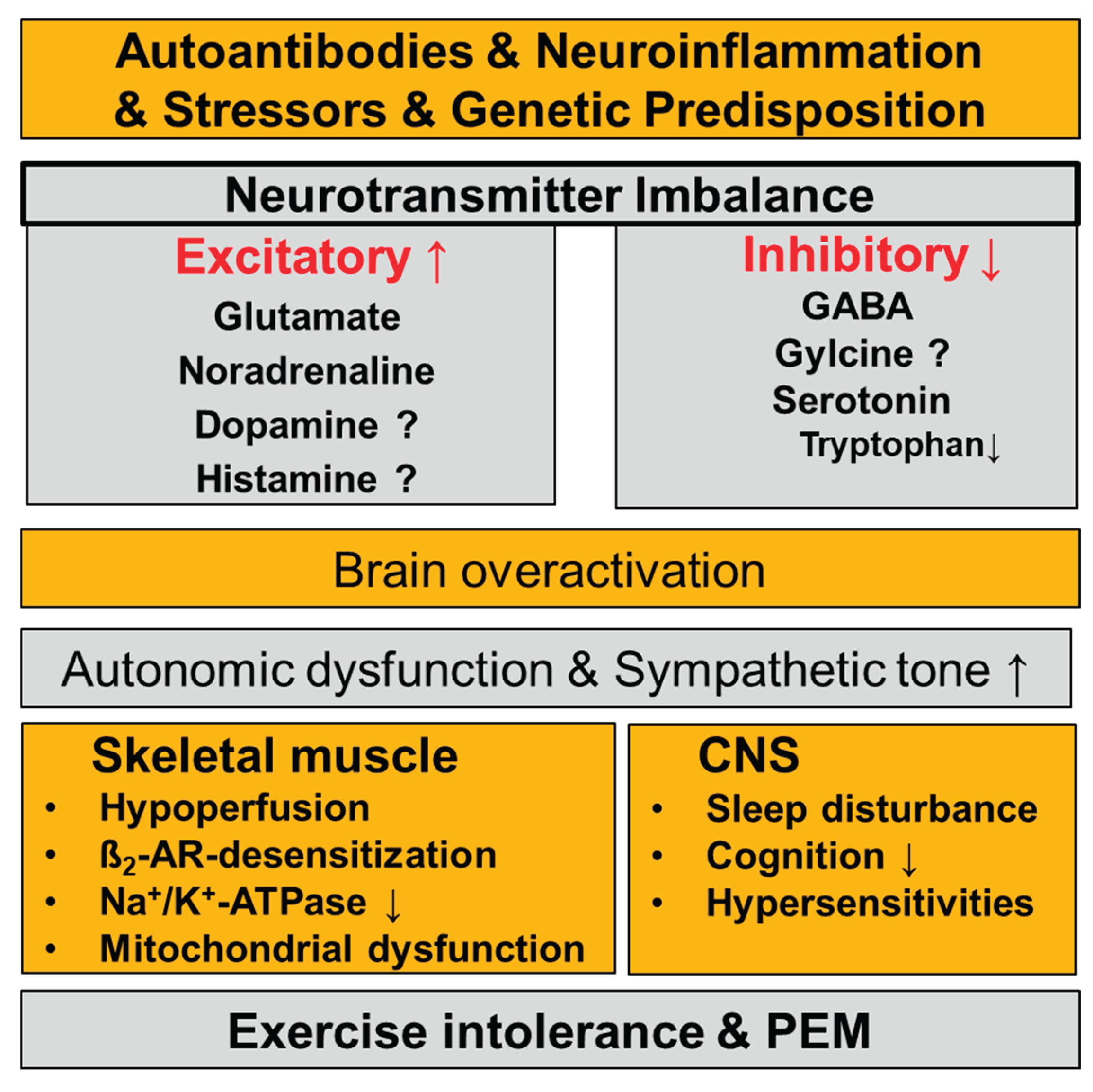

Disturbances of the Neurotransmitter Systems in ME/CFS

Noradrenergic System

Serotonin

GABA

Glutamate

Glycine

Dopamine

Histamine

Role of Neurotransmitter Imbalance in the Pathophysiology of ME/CFS and Their Potential Contribution to Typical Symptoms

Sleep Disturbances, Cognitive Impairment, and Sensory Hypersensitivities

Skeletal Muscle Pathophysiology

Why Current Treatments Show Limited Efficacy in ME/CFS

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abujrais, S.; Vallianatou, T.; Bergquist, J. Untargeted Metabolomics and Quantitative Analysis of Tryptophan Metabolites in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Patients and Healthy Volunteers: A Comparative Study Using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2024, 15, 3525–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraniuk, J.N. Exertional Exhaustion (Post-Exertional Malaise, PEM) Evaluated by the Effects of Exercise on Cerebrospinal Fluid Metabolomics–Lipidomics and Serine Pathway in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.R.; Londregan, A.K.; Alexander, T.D.; Entezari, A.A.; Covarrubias, M.; Waldman, S.A. Enteroendocrine cell regulation of the gut-brain axis. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2023, 17, 1272955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, V.C.; Greene, K.A.; Tabachnikova, A.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Sjögren, P.; Bertilson, B.; Reifert, J.; Zhang, M.; Kamath, K.; Shon, J. Cerebrospinal fluid immune phenotyping reveals distinct immunotypes of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. The Journal of Immunology 2025, vkaf087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont, A.; Burton, A.R.; Lemon, J.; Bennett, B.K.; Lloyd, A.; Vollmer-Conna, U. Reduced cardiac vagal modulation impacts on cognitive performance in chronic fatigue syndrome. PloS one 2012, 7, e49518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bested, A.; Saunders, P.; Logan, A. Chronic fatigue syndrome: neurological findings may be related to blood–brain barrier permeability. Medical hypotheses 2001, 57, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandina, P.; Munari, L.; Provensi, G.; Passani, M.B. Histamine neurons in the tuberomamillary nucleus: a whole center or distinct subpopulations? Frontiers in systems neuroscience 2012, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneva, R.S.; Decker, M.J.; Maloney, E.M.; Lin, J.-M.; Jones, J.F.; Helgason, H.G.; Heim, C.M.; Rye, D.B.; Reeves, W.C. Higher heart rate and reduced heart rate variability persist during sleep in chronic fatigue syndrome: a population-based study. Autonomic Neuroscience 2007, 137, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragée, B.; Michos, A.; Drum, B.; Fahlgren, M.; Szulkin, R.; Bertilson, B.C. Signs of Intracranial Hypertension, Hypermobility, and Craniocervical Obstructions in Patients With Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Frontiers in Neurology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C.; Lai, D.; Siegel, J.; Peever, J. An endogenous glutamatergic drive onto somatic motoneurons contributes to the stereotypical pattern of muscle tone across the sleep–wake cycle. Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28, 4649–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanas, H.; Muraki, K.; Balinas, C.; Eaton-Fitch, N.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Validation of impaired Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 3 ion channel activity in natural killer cells from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ Myalgic Encephalomyelitis patients. Molecular Medicine 2019, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanas, H.; Muraki, K.; Eaton, N.; Balinas, C.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Loss of Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 3 ion channel function in natural killer cells from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis patients. Molecular Medicine 2018, 24, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Campen, C.M.; Visser, F.C. Long-Haul COVID patients: prevalence of POTS are reduced but cerebral blood flow abnormalities remain abnormal with longer disease duration. Presented at the Healthcare, MDPI; 2022; p. 2105. [Google Scholar]

- Chilosi, M.; Doglioni, C.; Ravaglia, C.; Martignoni, G.; Salvagno, G.L.; Pizzolo, G.; Bronte, V.; Poletti, V. Unbalanced IDO1/IDO2 endothelial expression and skewed keynurenine pathway in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 pneumonia. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotecchia, S.; Stanasila, L.; Diviani, D. Protein-protein interactions at the adrenergic receptors. Current drug targets 2012, 13, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cron, R.Q. Immunologic prediction of long COVID. Nature Immunology 2023, 24, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cysique, L.A.; Jakabek, D.; Bracken, S.G.; Allen-Davidian, Y.; Heng, B.; Chow, S.; Dehhaghi, M.; Pires, A.S.; Darley, D.R.; Byrne, A. Post-acute COVID-19 cognitive impairment and decline uniquely associate with kynurenine pathway activation: a longitudinal observational study; Medrxiv, 2022-06. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.E.; Lehnen, M.; Stevens, S.R.; VanNess, J.M.; Stevens, J.; Snell, C.R. Chronotropic Intolerance: An Overlooked Determinant of Symptoms and Activity Limitation in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Frontiers in Pediatrics 2019, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ramírez, X.; Alvarado-Cervantes, N.S.; Jiménez-Barrios, N.; Raya-Tafolla, G.; Felix, R.; Martínez-Rojas, V.A.; Delgado-Lezama, R. GABAB Receptors Tonically Inhibit Motoneurons and Neurotransmitter Release from Descending and Primary Afferent Fibers. Life 2023, 13, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton-Fitch, N.; Du Preez, S.; Cabanas, H.; Muraki, K.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Impaired TRPM3-dependent calcium influx and restoration using Naltrexone in natural killer cells of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022, 20, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Komaroff, A.L. Does the chronic fatigue syndrome involve the autonomic nervous system? The American journal of medicine 1997, 102, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, H.; Szklarski, M.; Lorenz, S.; Sotzny, F.; Bauer, S.; Philippe, A.; Kedor, C.; Grabowski, P.; Lange, T.; Riemekasten, G.; Heidecke, H.; Scheibenbogen, C. Autoantibodies to Vasoregulative G-Protein-Coupled Receptors Correlate with Symptom Severity, Autonomic Dysfunction and Disability in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Abe, H.; Eiro, T.; Tsugawa, S.; Tanaka, M.; Hatano, M.; Nakajima, W.; Ichijo, S.; Arisawa, T.; Takada, Y. Systemic increase of AMPA receptors associated with cognitive impairment of long COVID. Brain Communications 2025, 7, fcaf337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaschuk, O.; Verkhratsky, A. GABAergic astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, M.; Pearse, D.D. The role of the serotonergic system in locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury. Frontiers in neural circuits 2015, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, A.; Heckman, C.; Perreault, M.-C. Spinally Projecting Serotonergic Neurons in Motor Network Modulation. Journal of Neurophysiology, 2025.

- Glassford, J.A. The neuroinflammatory etiopathology of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Frontiers in physiology 2017, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodlich, B.I.; Del Vecchio, A.; Horan, S.A.; Kavanagh, J.J. Blockade of 5-HT2 receptors suppresses motor unit firing and estimates of persistent inward currents during voluntary muscle contraction in humans. The Journal of Physiology 2023, 601, 1121–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Appelman, B.; Mooij-Kalverda, K.; Houtkooper, R.H.; van Weeghel, M.; Vaz, F.M.; Dijkhuis, A.; Dekker, T.; Smids, B.S.; Duitman, J.W. Prolonged indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase-2 activity and associated cellular stress in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. EBioMedicine 2023, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyires, K.; Zádori, Z.S.; Török, T.; Mátyus, P. α2-Adrenoceptor subtypes-mediated physiological, pharmacological actions. Neurochemistry international 2009, 55, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.T.; Kossowsky, J.; Oberlander, T.F.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Saul, J.P.; Wyller, V.B.; Fagermoen, E.; Sulheim, D.; Gjerstad, J.; Winger, A. Genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase modifies effects of clonidine treatment in chronic fatigue syndrome. The pharmacogenomics journal 2016, 16, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan-Olive, M.M.; Hansson, H.-A.; Enger, R.; Nagelhus, E.A.; Eide, P.K. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2019, 78, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoheisel, F.; Fleischer, K.M.; Rubarth, K.; Sepúlveda, N.; Bauer, S.M.; Konietschke, F.; Kedor, C.; Stein, A.E.; Wittke, K.; Seifert, M. Exploratory Study on Autoantibodies to Arginine-rich Human Peptides Mimicking Epstein-Barr Virus in Women with Post-COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 16, 1650948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Sheng, W.S.; Ehrlich, L.C.; Peterson, P.K.; Chao, C.C. Cytokine effects on glutamate uptake by human astrocytes. Neuroimmunomodulation 2000, 7, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.T.; Khan, H.; Khalid, A.; Mahmood, S.F.; Nasir, N.; Khanum, I.; de Siqueira, I.; Van Voorhis, W. Chronic inflammation in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 modulates gut microbiome: a review of literature on COVID-19 sequelae and gut dysbiosis. Molecular Medicine 2025, 31, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, P.; Pari, R.; Miller, S.; Warren, A.; Stovall, M.C.; Squires, J.; Chang, C.-J.; Xiao, W.; Waxman, A.B.; Systrom, D.M. Neurovascular Dysregulation and Acute Exercise Intolerance in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Pyridostigmine. CHEST 2022, 162, 1116–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothi, S.; Insel, M.; Claessen, G.; Kubba, S.; Howden, E.J.; Ruiz-Carmona, S.; Levine, T.; Rischard, F.P. Long COVID and chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis share similar pathophysiologic mechanisms of exercise limitation. Physiological Reports 2025, 13, e70535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelberer, M.M.; Buchanan, K.L.; Klein, M.E.; Barth, B.B.; Montoya, M.M.; Shen, X.; Bohórquez, D.V. A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Science 2018, 361, eaat5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Sato, W.; Maikusa, N.; Ota, M.; Shigemoto, Y.; Chiba, E.; Arizono, E.; Maki, H.; Shin, I.; Amano, K.; Matsuda, H.; Yamamura, T.; Sato, N. Free-water-corrected diffusion and adrenergic/muscarinic antibodies in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Neuroimaging 2023, 33, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-S.; Sato, W.; Son, C.-G. Brain-regional characteristics and neuroinflammation in ME/CFS patients from neuroimaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmunity Reviews 2024, 23, 103484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbel, M.; Mooslechner, A.A.; Bauer, S.; Günther, S.; Letsch, A.; Hanitsch, L.G.; Grabowski, P.; Meisel, C.; Volk, H.-D.; Scheibenbogen, C. Polymorphism in COMT is associated with IgG3 subclass level and susceptibility to infection in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Translational Medicine 2015, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löhn, M.; Wirth, K.J. Potential pathophysiological role of the ion channel TRPM3 in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and the therapeutic effect of low-dose naltrexone. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, M.J.; Engelhardt, S.; Eschenhagen, T. What is the role of β-adrenergic signaling in heart failure? Circulation Research 2003, 93, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, R.; Khan, K.; Mitolo, M.; De Marco, M.; Grieveson, L.; Varley, R.; Wilkinson, I.D.; Venneri, A. Modulatory effects of cognitive exertion on regional functional connectivity of the salience network in women with ME/CFS: A pilot study. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2021, 422, 117326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathé, P.; Götz, V.; Stete, K.; Walzer, D.; Hilger, H.; Pfau, S.; Hofmann, M.; Rieg, S.; Kern, W.V. No reduced serum serotonin levels in patients with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Infection 2025, 53, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy-Szakal, D.; Barupal, D.K.; Lee, B.; Che, X.; Williams, B.L.; Kahn, E.J.R.; Ukaigwe, J.E.; Bateman, L.; Klimas, N.G.; Komaroff, A.L.; Levine, S.; Montoya, J.G.; Peterson, D.L.; Levin, B.; Hornig, M.; Fiehn, O.; Lipkin, W.I. Insights into myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome phenotypes through comprehensive metabolomics. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 10056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naschitz, J.E.; Mussafia-Priselac, R.; Kovalev, Y.; Zaigraykin, N.; Elias, N.; Rosner, I.; Slobodin, G. Patterns of Hypocapnia on Tilt in Patients with Fibromyalgia, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Nonspecific Dizziness, and Neurally Mediated Syncope. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 2006, 331, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.J.; Bahl, J.S.; Buckley, J.D.; Thomson, R.L.; Davison, K. Evidence of altered cardiac autonomic regulation in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e17600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novodvorsky, P.; Bernjak, A.; Robinson, E.J.; Iqbal, A.; Macdonald, I.A.; Jacques, R.M.; Marques, J.L.; Sheridan, P.J.; Heller, S.R. Salbutamol-induced electrophysiological changes show no correlation with electrophysiological changes during hyperinsulinaemic–hypoglycaemic clamp in young people with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 2018, 35, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.; An, S.; Park, K.; Lee, S.; Han, Y.M.; Koh, S.-J.; Lee, J.; Gim, H.; Kim, D.; Seo, H. Gut Microbial Signatures in Long COVID: Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets; Infectious Diseases and Therapy, 2025; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pirkmajer, S.; Chibalin, A.V. Na,K-ATPase regulation in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2016, 311, E1–E31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polli, A.; Hendrix, J.; Ickmans, K.; Bakusic, J.; Ghosh, M.; Monteyne, D.; Velkeniers, B.; Bekaert, B.; Nijs, J.; Godderis, L. Genetic and epigenetic regulation of Catechol-O-methyltransferase in relation to inflammation in chronic fatigue syndrome and Fibromyalgia. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022, 20, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raij, T.; Raij, K. Association between fatigue, peripheral serotonin, and L-carnitine in hypothyroidism and in chronic fatigue syndrome. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2024, 15, 1358404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rus, C.P. Disruptions in serotonin-and kynurenine pathway metabolism in post-COVID: biomarkers and treatment. Frontiers in Neurology 2025, 16, 1532383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rus, C.P.; de Vries, B.E.; de Vries, I.E.; Nutma, I.; Kooij, J.S. Treatment of 95 post-Covid patients with SSRIs. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 18599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabkova, V.A.; Churilov, L.P.; Shoenfeld, Y. Neuroimmunology: what role for autoimmunity, neuroinflammation, and small fiber neuropathy in fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and adverse events after human papillomavirus vaccination? International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, A.E.; Li, M.; Jason, L.A. Two Neurocognitive Domains Identified for Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. Frontiers in Neurology 2025, 16, 1612548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelpfennig, J.; Topczewski, J.; Zajkowski, W.; Jankowiak-Siuda, K. The role of the salience network in cognitive and affective deficits. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2023, 17, 1133367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlauch, K.A.; Khaiboullina, S.F.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Rawat, S.; Petereit, J.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Blatt, N.; Mijatovic, T.; Kulick, D.; Palotás, A. Genome-wide association analysis identifies genetic variations in subjects with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Translational psychiatry 2016, 6, e730–e730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, B.; Garbsch, R.; Schäfer, H.; Bär, C.; Chatterjee, S.; Riemekasten, G.; Schulze-Forster, K.; Heidecke, H.; Schultheiß, C.; Binder, M. Autonomic dysfunction and vasoregulation in long COVID-19 are linked to anti-GPCR autoantibodies. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2025.

- Seljeset, S.; Liebowitz, S.; Bright, D.P.; Smart, T.G. Pre- and postsynaptic modulation of hippocampal inhibitory synaptic transmission by pregnenolone sulphate. Neuropharmacology 2023, 233, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.Y.; Barnden, L.R.; Kwiatek, R.A.; Bhuta, S.; Hermens, D.F.; Lagopoulos, J. Neuroimaging characteristics of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): a systematic review. Journal of Translational Medicine 2020, 18, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Z.Y.; Finegan, K.; Bhuta, S.; Ireland, T.; Staines, D.R.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.M.; Barnden, L.R. Brain function characteristics of chronic fatigue syndrome: A task fMRI study. NeuroImage: Clinical 2018, 19, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shank, R.; Aprison, M.; Baxter, C. Precursors of glycine in the nervous system: comparison of specific activities in glycine and other amino acids after administration of [U-14C] glucose,[3, 4-14C] glucose,[1-14C] glucose,[U-14C] serine or [1, 5-14C] citrate to the rat. Brain Research 1973, 52, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, P.A.; Giachetti, A. Reserpine: basic and clinical pharmacology. In Handbook of Psychopharmacology; Neuroleptics and Schizophrenia. Springer, 1978; Volume 10, pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Simadibrata, D.M.; Lesmana, E.; Gunawan, J.; Quigley, E.M.; Simadibrata, M. A systematic review of gut microbiota profile in COVID-19 patients and among those who have recovered from COVID-19. Journal of Digestive Diseases 2023, 24, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisto, S.A.; Tapp, W.; Drastal, S.; Bergen, M.; DeMasi, I.; Cordero, D.; Natelson, B. Vagal tone is reduced during paced breathing in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Autonomic Research 1995, 5, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słomko, J.; Estévez-López, F.; Kujawski, S.; Zawadka-Kunikowska, M.; Tafil-Klawe, M.; Klawe, J.J.; Morten, K.J.; Szrajda, J.; Murovska, M.; Newton, J.L. Autonomic phenotypes in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) are associated with illness severity: a cluster analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeldt, L.; Portilla, H.; Jacobsen, L.; Gjerstad, J.; Wyller, V.B. Polymorphisms of adrenergic cardiovascular control genes are associated with adolescent chronic fatigue syndrome. Acta Paediatr 2011, 100, 293–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotzny, F.; Filgueiras, I.S.; Kedor, C.; Freitag, H.; Wittke, K.; Bauer, S.; Sepúlveda, N.; Mathias da Fonseca, D.L.; Baiocchi, G.C.; Marques, A.H.C.; Kim, M.; Lange, T.; Plaça, D.R.; Luebber, F.; Paulus, F.M.; De Vito, R.; Jurisica, I.; Schulze-Forster, K.; Paul, F.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Rust, R.; Hoppmann, U.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Riemekasten, G.; Heidecke, H.; Cabral-Marques, O.; Scheibenbogen, C. Dysregulated autoantibodies targeting vaso- and immunoregulatory receptors in Post COVID Syndrome correlate with symptom severity. Frontiers in immunology 13, 2022.

- Stewart, J.M. Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction in Adolescents with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Is Characterized by Attenuated Vagal Baroreflex and Potentiated Sympathetic Vasomotion. Pediatric Research 2000, 48, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Sadato, N.; Okada, T.; Mizuno, K.; Sasabe, T.; Tanabe, H.C.; Saito, D.N.; Onoe, H.; Kuratsune, H.; Watanabe, Y. Reduced responsiveness is an essential feature of chronic fatigue syndrome: A fMRI study. BMC Neurology 2006, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.; Walker, M.; Sweetman, E.; Helliwell, A.; Peppercorn, K.; Edgar, C.; Blair, A.; Chatterjee, A. Molecular mechanisms of neuroinflammation in ME/CFS and long COVID to sustain disease and promote relapses. Frontiers in neurology 2022a, 13, 877772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tate, W.; Walker, M.; Sweetman, E.; Helliwell, A.; Peppercorn, K.; Edgar, C.; Blair, A.; Chatterjee, A. Molecular mechanisms of neuroinflammation in ME/CFS and long COVID to sustain disease and promote relapses. Frontiers in neurology 2022b, 13, 877772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapaliya, K.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.; Eaton-Fitch, N.; Eftekhari, Z.; Inderyas, M.; Barnden, L. Imbalanced brain neurochemicals in long COVID and ME/CFS: a preliminary study using MRI. The American journal of medicine 2025, 138, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorstensen, J.R.; Henderson, T.T.; Kavanagh, J.J. Serotonergic and noradrenergic contributions to motor cortical and spinal motoneuronal excitability in humans. Neuropharmacology 2024, 242, 109761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Campen, C.; Rowe, P.C.; Visser, F.C. Cerebral Blood Flow Is Reduced in Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients During Mild Orthostatic Stress Testing: An Exploratory Study at 20 Degrees of Head-Up Tilt Testing. Healthcare (Basel) 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van van Campen, C.M.C.; Rowe, P.C.; Visser, F.C. Orthostatic symptoms and reductions in cerebral blood flow in Long-Haul COVID-19 patients: similarities with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Medicina 2021, 58, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenbergh, D.; Nijs, J.; Kos, D.; Van Weijnen, L.; Struyf, F.; Meeus, M. Malfunctioning of the autonomic nervous system in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic literature review. European journal of clinical investigation 2014, 44, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosterwijck, J.; Marusic, U.; De Wandele, I.; Meeus, M.; Paul, L.; Lambrecht, L.; Moorkens, G.; Danneels, L.; Nijs, J. Reduced parasympathetic reactivation during recovery from exercise in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of clinical medicine 2021, 10, 4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanElzakker, M.B.; Brumfield, S.A.; Lara Mejia, P.S. Neuroinflammation and Cytokines in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): A Critical Review of Research Methods. Front Neurol 2018, 9, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walitt, B.; Singh, K.; LaMunion, S.R.; Hallett, M.; Jacobson, S.; Chen, K.; Enose-Akahata, Y.; Apps, R.; Barb, J.J.; Bedard, P. Deep phenotyping of post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Nature communications 2024, 15, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, D.; Cao, K.; Zou, J. Increased response to β2-adrenoreceptor stimulation augments inhibition of IKr in heart failure ventricular myocytes, 2012.

- Wang, Y.; Pereira, E.; Maus, A.; Ostlie, N.; Navaneetham, D.; Lei, S.; Albuquerque, E.; Conti-Fine, B. Human bronchial epithelial and endothelial cells express α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Molecular pharmacology 2001, 60, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber-Fahr, W.; Dommke, S.; Sack, M.; Alzein, N.; Becker, R.; Demirakca, T.; Ende, G.; Schilling, C. Reduced ATP-to-phosphocreatine ratios in neuropsychiatric post-COVID condition: Evidence from 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biological Psychiatry, 2026.

- Wirth, K.; Steinacker, J.M. The Potential Causes Of Myasthenia And Fasciculations In The Severely Ill Me/Cfs-Patient: Role Of Disturbed Electrophysiology, 2025.

- Wirth, K.J.; Löhn, M. Orthostatic Intolerance after COVID-19 Infection: Is Disturbed Microcirculation of the Vasa Vasorum of Capacitance Vessels the Primary Defect? Medicina 2022, 58, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, K.J.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Paul, F. An attempt to explain the neurological symptoms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal of Translational Medicine 2021, 19, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.C.; Devason, A.S.; Umana, I.C.; Cox, T.O.; Dohnalová, L.; Litichevskiy, L.; Perla, J.; Lundgren, P.; Izzo, L.T.; Kim, J. Serotonin reduction in post-acute sequelae of viral infection. Cell 2023, 186, 4851–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortinger, L.A.; Endestad, T.; Melinder, A.M.D.; Øie, M.G.; Sevenius, A.; Bruun Wyller, V. Aberrant resting-state functional connectivity in the salience network of adolescent chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0159351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyller, V.B.; Saul, J.; Amlie, J.P.; Thaulow, E. Sympathetic predominance of cardiovascular regulation during mild orthostatic stress in adolescents with chronic fatigue. Clinical physiology and functional imaging 2007, 27, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; LaManca, J.J.; Natelson, B.H. A measure of heart rate variability is sensitive to orthostatic challenge in women with chronic fatigue syndrome. Experimental biology and medicine 2003, 228, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, P.; Tang, J.; Yang, B.; Li, H.; Liang, M.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y. Gut microbiota dysbiosis correlates with long COVID-19 at one-year after discharge. Journal of Korean medical science 2023, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Neurotransmitter | Effect | Receptors | Main locations | Key functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate | Excitatory (main CNS excitatory transmitter) | Ionotropic: NMDA, AMPA, Kainate Metabotropic: mGluR (I–III) | Widely distributed in CNS (cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum) | Synaptic plasticity, learning & memory, motor control, sensory processing |

| Noradrenaline | Mainly excitatory | α₁, α₂, β₁, β₂, β3-adrenergic | Locus coeruleus, widespread CNS projections; peripheral sympathetic nerves | Arousal, attention, stress response, mood, blood pressure regulation |

| Acetylcholine (ACh) | Excitatory or inhibitory (receptor-dependent) | Nicotinic (ionotropic). Muscarinic (M1–M5) (metabotropic) |

Neuromuscular junction, autonomic nervous system, basal forebrain | Muscle contraction, memory & learning, autonomic control |

| Histamine | Excitatory/ modulatory |

H₁, H₂, H₃, H₄ | Hypothalamus (tuberomammillary nucleus), peripheral | Wakefulness, attention, appetite control, immune responses |

|

GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) |

Inhibitory | GABA-A (ionotropic, Cl⁻), GABA-B (metabotropic), GABA-C | Brain and spinal cord | Inhibitory control, anxiety regulation, sleep, muscle tone |

| Glycine | Inhibitory | Glycine receptor (ionotropic, Cl⁻), Co-agonist at NMDA receptors | Spinal cord, brainstem | Motor and sensory inhibition, reflex control, NMDA receptor modulation |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | Mostly inhibitory/ modulatory |

5-HT₁–₇ (mostly metabotropic; 5-HT₃ ionotropic) | Raphe nuclei, widespread CNS | Mood, sleep, appetite, pain modulation, emotional regulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).