Historical Evolution of Imaging in Crohn’s Disease

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Rioux described the “puzzling” imaging world of Crohn’s disease, highlighting the need to combine conventional barium examinations with cross-sectional methods such as ultrasound and CT to achieve a complete evaluation [

4]. Oral contrast fluoroscopy was particularly useful for detecting small-bowel disease, identifying strictures and fistulas. Barium follow-through examinations provided good visualization of mucosal irregularities, strictures, and fistulas in the small bowel, but lacked extraluminal assessment. Meanwhile, ultrasound became an important tool for targeted assessment of the terminal ileum, especially when combined with color Doppler to evaluate mural vascularity and inflammation. CT, on the other hand, quickly emerged as the reference technique for complicated disease, particularly for detecting perforations, abscesses, and complex fistulas. Nuclear medicine studies complemented this approach by helping confirm abscesses or regions of significant inflammation. A major turning point occurred in the early 2000s with the increasing availability and refinement of

MRE. The 2013 ECCO-ESGAR guidelines marked the first official recognition of MRE as a central imaging tool recommended for the assessment of most Crohn’s disease manifestations. Regarding MRE, these recommendations have been substantially confirmed in the more recent ECO-ESGAR guidelines dated 2019 and 2025 [

2,

3].

- 2.

The rise of MR Enterography (2000–2015): A multiparametric, comprehensive, radiation-free tool

The first introduction and subsequent refinement of MRE in the early 2000s have profoundly transformed the assessment of Crohn’s disease [

5,

6]. By 2013, the ECCO–ESGAR consensus formally recommended MRE for the evaluation of nearly all disease domains, including extent, inflammatory activity, complications, and treatment response [

6,

7,

8]. MRE has since become one of the most powerful modalities for evaluating Crohn’s disease in the small and large bowel [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Its ability to provide comprehensive abdominal imaging without ionizing radiation has made MRE particularly attractive for younger patients requiring repeated examinations. Furthermore, high-resolution (HR) MRI represents the gold standard for the diagnosis and staging of perianal fistulas. The final paragraph of this review is therefore dedicated to a focused discussion of HRMRI, highlighting its role in accurate anatomical delineation of anal and perianal fistulas, disease classification and staging, and clinical decision-making.

Unlike CT, MRE avoids ionizing radiation and is therefore particularly suitable for young patients who require lifelong follow-up. Unlike IUS, MRE simultaneously provides a panoramic and accurate view of the entire small bowel, large portions of the colon, and the anorectal region. One of the principal strengths of MRE lies in its inherently multiparametric nature. By integrating complementary morphological and functional sequences, MRE enables comprehensive characterization of Crohn’s disease activity and behaviour. Its central role is largely attributable to its multiparametric nature and its ability to provide a panoramic, high-contrast evaluation of the entire abdominopelvic cavity without exposing patients to ionizing radiation. These advantages are particularly relevant given the chronic relapsing nature of Crohn’s disease and the young age at diagnosis for many patients, which makes repeated imaging a lifelong requirement [

6].

Multiparametric MRE protocols therefore combine a series of complementary sequences, each providing distinct and synergistic diagnostic information. T2-weighted sequences (

Figure 1a-c) are fundamental for a comprehensive morphological assessment of Crohn’s disease on both axial and coronal planes. They allow accurate definition of disease location, longitudinal extent, and severity, including evaluation of bowel wall thickening, luminal narrowing, and the presence of penetrating complications such as fistulas and abscesses at any level of the small and large bowel. These sequences are also essential for assessing extraintestinal manifestations of disease, including inflammatory changes of the surrounding mesenteric fat. Beyond structural assessment, T2-weighted imaging plays a pivotal role in the detection of inflammatory activity through the identification of mural and mesenteric oedema. Fat-suppressed T2-weighted sequences, in particular, enhance the conspicuity of high-signal oedematous tissue and currently represent the only imaging technique capable of directly demonstrating oedema at the level of the intestinal wall, mesenteric lymph nodes, and mesentery. Oedema is a hallmark of active inflammation and reflects increased vascular permeability and interstitial fluid accumulation [

5,

12,

13,

14]. As such, it provides information that is complementary to mural hypervascularization observed on contrast-enhanced sequences, contributing to a more integrated and pathophysiologically meaningful assessment of disease activity. [

12,

13]. Pre- and post-gadolinium–enhanced T1-weighted acquisitions enable detailed assessment of mucosal and transmural enhancement patterns (

Figure 1d-g), which reflect bowel wall vascularity and the degree of inflammatory activity. These sequences are essential for evaluating not only the affected bowel segments, but also associated inflammatory changes in the mesentery and regional lymph nodes.

In addition, analysis of enhancement behaviour over time is clinically informative: early, intense enhancement is typically associated with active inflammation, whereas delayed and more progressive enhancement may provide indirect information on the presence of fibrotic components within the bowel wall. This temporal evaluation of contrast enhancement therefore contributes to distinguishing predominantly inflammatory disease from mixed or fibrostenotic phenotypes, supporting more tailored therapeutic decision-making. [

15,

16].

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) provides important functional information by probing the microscopic mobility of water molecules within tissues. In Crohn’s disease, restricted diffusion is a well-established imaging biomarker of active inflammation, reflecting increased cellularity, inflammatory cell infiltration, and reduced extracellular space. DWI abnormalities frequently coexist with fibrosis, making this sequence particularly valuable in identifying segments with ongoing inflammatory activity even in the presence of chronic structural changes. Several studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between DWI signal intensity, apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values, and endoscopic or histopathological markers of disease activity, supporting its role as a non–contrast-based surrogate of inflammation and its potential utility in treatment monitoring, especially in patients with contraindications to gadolinium-based contrast agents [

17,

18].

Cine-MRI sequences further enhance functional assessment by capturing real-time bowel motility. These sequences, typically acquired using dynamic T2-weighted imaging or balanced steady-state free-precession techniques such as TRUFI (True Fast Imaging with Steady-State Precession), allow continuous visualization of intestinal peristalsis. Cine imaging is invaluable for differentiating fixed fibrostenotic strictures, which demonstrate persistently reduced or absent motility, from transient luminal narrowing caused by spasm or peristaltic contraction [

19,

20,

21]. In addition, cine-MRI can reveal subtle motility abnormalities in upstream or downstream bowel segments that may not be apparent on static images, contributing to a more comprehensive evaluation of disease burden and functional impairment. When integrated with morphological and contrast-enhanced sequences, cine-MRI strengthens the multiparametric approach of MRE, improving phenotypic characterization and supporting tailored therapeutic strategies.

The capability of MRE to acquire images in multiple planes with high spatial and contrast resolution further allows refined assessment of both mural and extramural disease components, including mesenteric involvement and penetrating complications. Because images are routinely obtained both in axial and coronal planes, MRE permits an accurate localization of bowel lesions, detailed morphological characterization, and comprehensive mapping of disease extent across the entire gastrointestinal tract. Technologically, MRE is a rapidly evolving modality. Continuous advances in sequence design, acquisition speed, motion correction strategies, and functional imaging parameters have progressively improved image quality and diagnostic performance [

16]. This ongoing technical evolution ensures that MRE remains at the forefront of non-invasive imaging for the assessment of transmural inflammation in Crohn’s disease. As a result of these advantages, MRE has progressively established itself as the reference imaging modality for a comprehensive evaluation of Crohn’s disease, particularly when full staging or re-staging is required. Its central role is attributable not only to its multiparametric approach but also to its ability to provide a panoramic, high-contrast evaluation of the entire abdominopelvic cavity without exposing patients to ionizing radiation [

6,

7,

8,

21]. These features are especially relevant given the chronic relapsing nature of Crohn’s disease and the young age at diagnosis for many patients, which necessitate repeated imaging over a lifetime.

This combination of structural and functional information makes MRE particularly powerful in assessing inflammatory activity. Features such as increased mural thickness, hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging, layered or transmural enhancement after contrast administration, and restricted diffusion correlate closely with endoscopic markers of disease severity [

6,

11]

. Indeed, these imaging markers form the basis of validated scores such as the Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity (MaRIA), which is now widely accepted as a reliable surrogate for mucosal inflammation in both the ileum and colon [

10]

.

A major advantage of MRE, and one that strongly influences clinical decision-making, is its capacity to characterise strictures with exceptional detail. The ability to distinguish inflammatory from fibrotic narrowing relies on the multiparametric information inherent to the technique: active inflammatory strictures typically demonstrate high T2 signal, prominent or layered enhancement, and restricted diffusion, whereas fibrotic strictures often appear as low-signal, homogeneous, and relatively non-enhancing segments with preserved diffusion characteristics [

9]. This distinction is critical, as treatment of inflammatory strictures favours medical escalation—including biologics—whereas fibrotic strictures often require endoscopic or surgical intervention.

MRE is equally valuable in the detection of penetrating complications, an area where its sensitivity rivals or surpasses that of CT [

11]. The modality excels in identifying entero-enteric and entero-colonic fistulas, subtle sinus tracts, intramural or mesenteric abscesses, and inflammatory phlegmons. These complications carry significant prognostic weight, often predicting a more aggressive disease course and influencing therapeutic strategies. Because MRE can evaluate both mural and extramural structures comprehensively, it provides a more complete assessment of disease behaviour than endoscopy alone [

9] (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Several MRI-based activity indices have been developed to standardize the assessment of inflammatory burden in Crohn’s disease and to provide reproducible metrics for clinical practice and research [

15,

21,

22]. The Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity (MaRIA) is the most widely validated score and incorporates mural thickness, relative contrast enhancement, presence of oedema on T2-weighted imaging, and ulceration to quantify disease activity in individual bowel segments [

9,

10,

11]. MaRIA correlates strongly with endoscopic severity and is frequently used as an imaging surrogate for mucosal inflammation, particularly in treat-to-target strategies [

11]. The Crohn’s Disease Magnetic Resonance Index (CDMI) represents an alternative scoring system that emphasises mural thickness, T2 hyperintensity, and perimural inflammatory changes, offering a slightly simplified framework that may be more feasible in routine practice while maintaining good correlation with histologic and clinical markers of activity [

9]. The Clermont score, derived from diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), integrates the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) with mural thickness and relative contrast enhancement, thereby complementing conventional parameters with a functional biomarker of inflammatory cellularity [

17,

18]. Because DWI is sensitive to restricted diffusion associated with active inflammation, the Clermont score has shown high accuracy in differentiating active from quiescent disease and may be particularly valuable when gadolinium administration is contraindicated [

10]. Together, these scoring systems enhance the objectivity of MRI interpretation, facilitate longitudinal monitoring, and support the use of MRI as a reproducible endpoint in clinical trials and clinical decision-making.

Last, MRE represents the imaging modality with the greatest potential for integration with artificial intelligence (AI) in Crohn’s disease. The multiparametric nature of MRE, combining morphological sequences with functional information such as diffusion-weighted imaging and contrast enhancement provides a rich dataset for machine learning applications. AI-based approaches have shown promising results in automated bowel segmentation, detection of inflamed segments, and quantification of disease activity through radiomics and deep learning models, with performance comparable to expert readers in preliminary studies. In the near future, AI-enhanced MRE may enable objective, reproducible assessment of disease activity, prediction of treatment response, and longitudinal monitoring, thereby reducing interobserver variability and improving workflow efficiency. These advances position MRE as a key platform for precision imaging in Crohn’s disease.

Beyond its diagnostic accuracy and potential, MRE offers several practical advantages. The absence of ionising radiation makes it suitable for repeated follow-up, which is essential for chronic diseases such as Crohn’s. Its panoramic evaluation of the small bowel is unmatched, and its capacity to assess soft tissues, mesentery, and extra-intestinal complications in a single examination is unique among available modalities.

However, MRE is not without limitations. It requires longer acquisition times compared with CT, and patient cooperation, including multiple breath-holding acquisition, and tolerance of luminal distension, both essential for optimal image quality. Motion artefacts from peristalsis may necessitate the use of antispasmodic agents. Furthermore, despite growing availability, MRE remains more resource-intensive than ultrasound, both in terms of cost and scanner time, and may not be immediately accessible in all clinical settings.

In summary, MRE is a safe and complex imaging procedure which provides an incomparable combination of anatomical detail and functional information, making it the most comprehensive non-invasive tool for the assessment of Crohn’s disease across its inflammatory, stricturing, and penetrating manifestations.

- 3.

The renewed interest in Intestinal Ultrasound (IUS): a clinical-radiological monitoring tool in Crohn’s disease management

Renewed interest in intestinal ultrasound (IUS) reflects a broader shift in Crohn’s disease management toward tight-control and treat-to-target strategies, in which rapid, repeated assessment of disease activity is essential. Once considered mainly a complementary or supportive technique, IUS has progressively become a key clinical–radiological tool, particularly in large gastroenterology centers with integrated imaging expertise. Its growing importance is attributable not only to technical refinement, but also to its intrinsic clinical strengths: it is non-invasive, radiation-free, cost-effective, easily repeatable, and capable of providing immediate, real-time information at the bedside [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Another relevant factor is the increasing dissemination of this technique not only among radiologists but also among gastroenterologists. These characteristics align exceptionally well with the needs of chronic inflammatory diseases, in which dynamic monitoring and frequent reassessment are essential.

The fundamental strengths of IUS derive from its ability to visualize bowel wall thickness, mural stratification, and peristaltic activity with high temporal resolution. Bowel wall thickening represents one of the most robust markers of inflammatory activity and, when combined with colour or power Doppler evaluation, ultrasound becomes a sensitive tool for assessing mural hypervascularization, considered a surrogate marker of active inflammation [

23,

24,

25,

26] (

Figure 3a-c). Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) allows dynamic evaluation of microvascular perfusion, enabling a more refined analysis of transmural enhancement patterns. CEUS is useful for early assessment of therapeutic response as well as for the identification and characterization of abscesses. Another promising development is ultrasound elastography, which may be useful in distinguishing inflammatory from fibrotic strictures, a diagnostic challenge traditionally dominated by MRE [

25] (

Figure 3d).

However, the limitations of IUS must be acknowledged. The major limitation of this technique lies in its strong operator dependence. Diagnostic performance is highly influenced by variations in training, experience, and equipment. Adequate expertise usually requires exposure to a high volume of cases with systematic correlation to more robust imaging modalities, a condition typically met only in centers of excellence. Another limitation is the poor reproducibility of the examination, its extreme focality, and the lack of panoramic assessment, which makes a complete and reliable evaluation of the small bowel impossible. Furthermore, image acquisition depends exclusively on the operator’s manual skill, which is therefore not reproducible or standardized, as in CT or MRI. Moreover, the diagnostic accuracy is strongly dependent on patient body habitus and on the presence of intestinal gas, with inability to evaluate gas-distended bowel loops, retroperitoneal regions. Body habitus may reduce acoustic penetration, limiting evaluation in obese patients; certain bowel segments, particularly deep pelvic loops or proximal small-bowel segments, may not be adequately visualized [

22,

23,

24].

One of the most interesting aspects of IUS in gastroenterological practice is its suitability for frequent monitoring, making it a natural imaging complement to treat-to-target strategies, particularly in younger and pediatric patients. Unlike MRE or CT, which require logistical coordination, IUS can be repeated as often as necessary, allowing proactive therapeutic adjustments based on early identification of subclinical disease activity. This is particularly useful in the management of patients receiving biologic therapies, in whom early changes in bowel wall thickness or vascularity often correlate with long-term treatment outcomes. A potential source of bias may arise from “internal” rather than independent or external assessment of treatment response, since ultrasound is often performed by the same gastroenterologist who prescribes the biologic therapy, or by a gastroenterologist within the same clinical team. Thus, what constitutes a strength may also represent a potential bias.

For these reasons, although IUS plays a valuable role in routine monitoring and rapid assessment, it is generally insufficient for complete disease mapping at diagnosis or in complex cases requiring a comprehensive overview. In such scenarios, MRE remains the reference imaging modality [

8,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Computed Tomography / CT Enterography (CTE): Rapid, Powerful Modality for Emergency Evaluation

Although the long-term management of Crohn’s disease increasingly favors radiation-free imaging approaches, computed tomography remains an essential tool, particularly in the acute setting where rapid diagnosis is critical. CT’s speed, broad availability, and excellent spatial resolution make it the cornerstone imaging modality in emergency departments worldwide, where patients often present with severe abdominal pain, fever, or signs suggestive of abscess formation, perforation, or high-grade obstruction.

The diagnostic strengths of CT in Crohn’s disease are primarily related to its superior detection of extramural and transmural complications. When perforation is suspected, whether free perforation or a contained microperforation, CT is unmatched in demonstrating extraluminal air, fluid collections, and the pattern and extent of inflammatory changes in the surrounding mesentery. Mesenteric abscesses, phlegmons, and complex fistulous tracts are readily identified, and CT’s rapid acquisition allows diagnosis even in clinically unstable patients who may not tolerate longer imaging protocols. In cases of suspected obstruction, CT excels in determining the site and severity of luminal narrowing, detecting pre-stenotic dilation, and identifying transition points, information crucial for guiding urgent surgical or endoscopic intervention [

28,

29,

30].

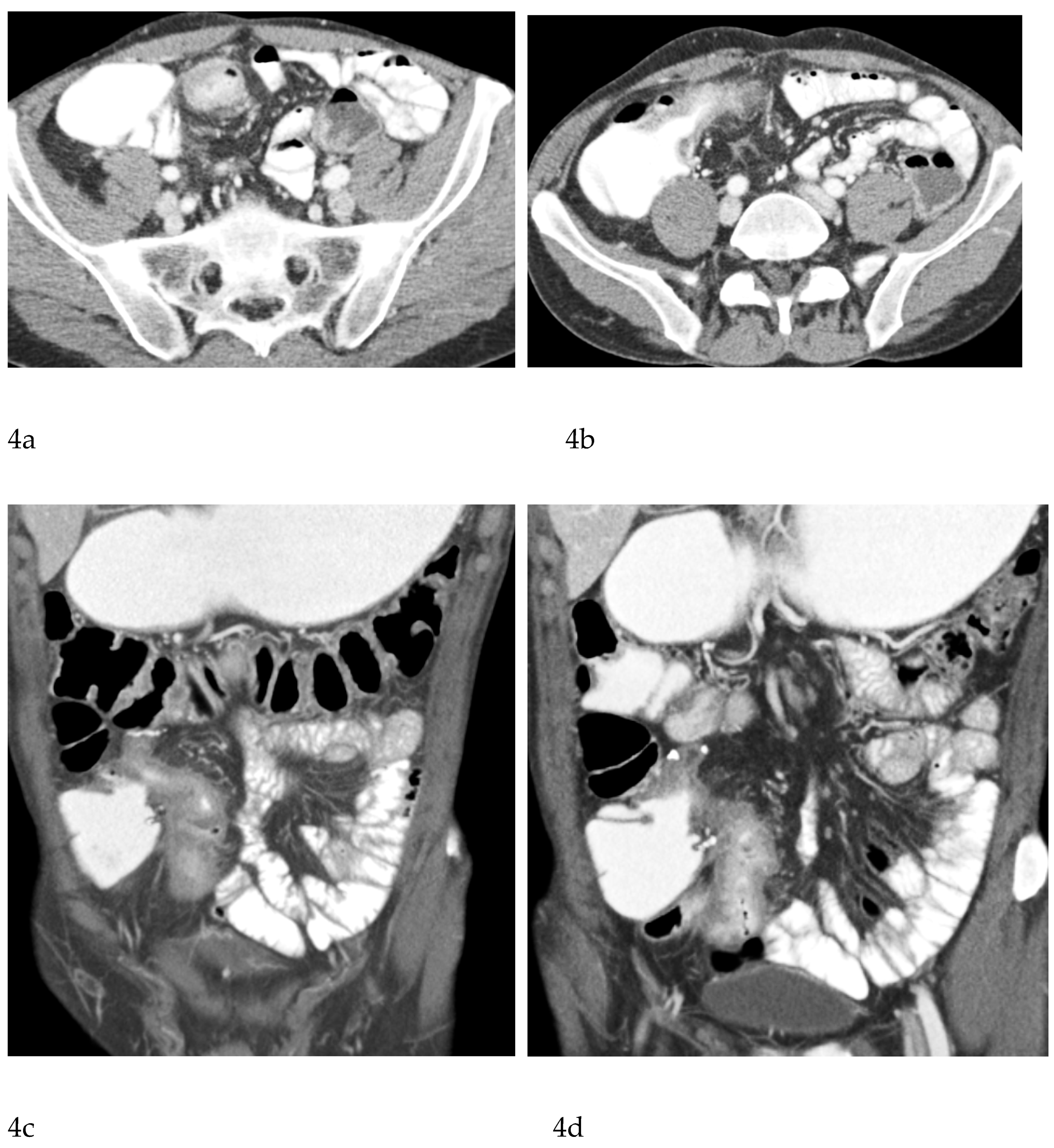

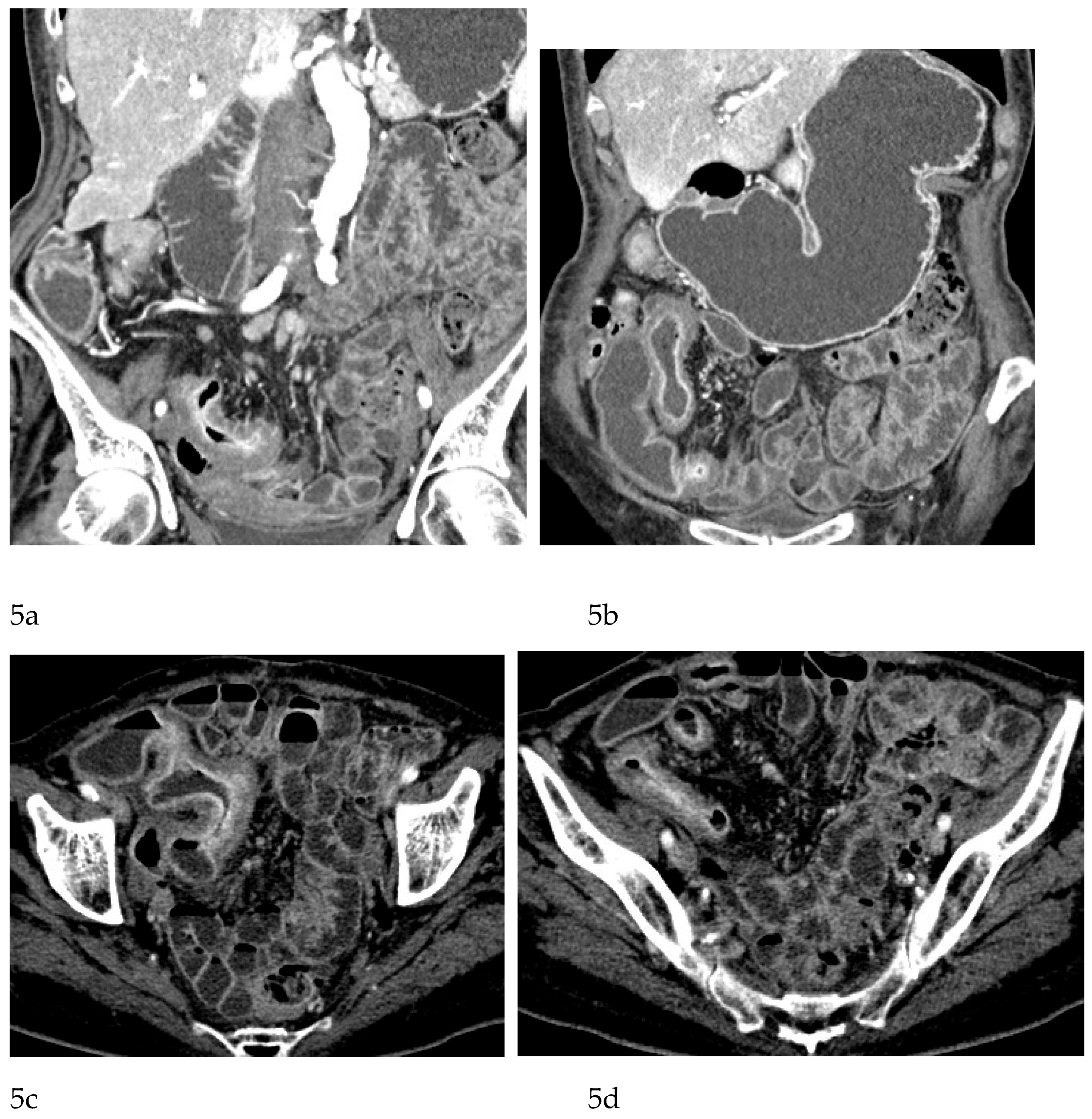

CT Enterography (CTE), a dedicated technique involving neutral (water macrogol solutions) or positive (iodinated) oral contrast for optimal luminal distention, enhances the modality’s utility in elective outpatient evaluation, shown on

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. CTE performed with positive oral contrast, improves the visualization of the entire small bowel lumen and relationships between the loops, being particularly useful in complex disease associated with adhesions and fistulas (

Figure 4a-d,

Figure 5a-d). On the other hand, CTE performed with negative oral contrast enables assessment of mucosal hyperenhancement, wall thickening, and inflammatory changes CTE with negative oral contrast [

Figure 5]. However, although CTE can approximate some of the mural and extramural information obtained with MRE, it lacks the functional imaging capabilities of MRI and cannot distinguish with confidence between inflammatory and fibrotic strictures. For this reason, CT use in chronic staging is generally reserved for situations in which MRE is unavailable or contraindicated, or when specific luminal abnormalities, such as unexplained focal thickening or suspected small-bowel polyps, require rapid clarification [

8,

28,

29,

30].

The limitations of CT/CTE in Crohn’s disease are inseparable from its greatest challenge: ionizing radiation. Young patients with IBD are particularly vulnerable to the cumulative effects of repeated CT scans, and the risk of radiation exposure has led to significant efforts to limit CT use outside of emergencies. Even with dose-reduction strategies, CT is not favored for routine follow-up or treat-to-target intervals. Furthermore, CT lacks the multiparametric functional detail provided by MRI and the dynamic assessment capabilities of IUS, rendering it less suited for nuanced characterization of disease behavior.

Despite these limitations, CT remains irreplaceable in modern Crohn’s disease care. Its unmatched speed and reliability in diagnosing life-threatening complications ensure that it remains the first-line modality in acute presentations. Used judiciously and in conjunction with MRE and IUS, CT forms an integral part of a balanced and effective imaging strategy [

28].

Table 1.

Strengths and Limitations of Key Imaging Modalities in Crohn’s Disease.

Table 1.

Strengths and Limitations of Key Imaging Modalities in Crohn’s Disease.

| FEATURE |

IUS |

MRE |

CT |

Radiation |

None |

None |

Yes |

| Visualization of entire small bowel |

Moderate |

Excellent |

Good |

| Extramural disease |

Moderate |

Excellent |

Excellent |

| Assessment of activity |

Good |

Excellent |

Good |

| Fibrosis assessment |

Limited |

Best available non-invasive tool |

Limited |

| Fistulas / Abscesses |

Moderate |

Excellent |

Excellent |

| Use in emergency |

Limited |

Limited |

Best |

| Repeatability |

Excellent |

Excellent |

Poor |

Table 2.

Recommended Imaging Modality by Clinical Scenario.

Table 2.

Recommended Imaging Modality by Clinical Scenario.

| Clinical Scenario |

Preferred Modality |

Justification |

| Initial diagnosis |

MRE + IUS |

Radiation-free; high diagnostic yield; complementary luminal + extraluminal information |

| Monitoring treatment response |

IUS ± MRE |

IUS for frequent bedside assessment; MRE for full reassessment when needed |

| Suspected obstruction |

CT or MRE |

CT best in emergencies; MRE preferred for elective evaluation or characterization of stricture phenotype |

| Suspected abscess |

CT or MRE |

CT for acute settings; MRE for detailed elective evaluation |

| Perianal disease |

High-resolution MRI of the pelvis (HRMRI) |

Gold standard for fistulas, abscesses, and sphincter complex |

| Suspected penetrating disease |

MRE |

Superior assessment of sinus tracts, fistulas, and extramural spread |

| Routine follow-up |

IUS |

Accessible, radiation-free, low cost, repeatable |

| Staging / Restaging |

MRE |

Best technique for full mapping of small bowel and complications |

| Surveillance in long-term disease |

MRE / CTE |

MRE preferred; CTE only when MRE unavailable or for detailed evaluation of small-bowel polyps or abnormal wall thickening |

Perianal Crohn’s Disease: The Role of MRI and Complementary Techniques

Perianal involvement represents one of the most debilitating manifestations of Crohn’s disease, with a substantial impact on quality of life and long-term prognosis. Fistulas and abscesses in this region are frequently complex, may be recurrent, and often coexist with active luminal disease. Because physical examination is limited in its ability to define the full extent and configuration of fistulous tracts, cross-sectional imaging, particularly MRI, has become indispensable in both baseline assessment and longitudinal follow-up [

31,

32].

MRI is widely regarded as the gold standard imaging modality for perianal Crohn’s disease, owing to its exquisite soft-tissue contrast and multiplanar capabilities. A typical MRI protocol for perianal fistulas includes high-resolution T2-weighted sequences with and without fat suppression in axial, coronal, and often oblique planes aligned with the anal canal, together with T1-weighted images before and after gadolinium administration. Fat-suppressed post-contrast images are particularly helpful in delineating enhancing fistula tracts and active inflammatory components, while T2-weighted sequences excel at highlighting fluid-rich collections and oedematous tissues. Many centres increasingly add diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), which may further characterize inflammatory activity and help differentiate between active tracts and more quiescent fibrotic tissue [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

From a morphological perspective, MRI enables precise classification of fistulas according to established schemes (e.g. Parks’ classification), distinguishing intersphincteric, trans-sphincteric, supra-sphincteric, and extrasphincteric trajectories, as well as identifying secondary extensions and supralevator involvement. This detailed anatomical mapping is fundamental for surgical planning, including the placement of setons, the choice and timing of sphincter-sparing procedures, and the assessment of potential risks to continence. MRI is also highly sensitive for detecting associated abscesses, which may be small, deeply located, and clinically occult. Identifying these collections before initiating or intensifying immunosuppressive therapy is critical to avoid sepsis and treatment failure [

31,

32,

33,

34]. .

The van Assche MRI score, introduced in the early 2000s, was a landmark attempt to quantify perianal disease severity by integrating features such as the number and location of fistula tracts, degree of extension, presence of abscesses, and signal characteristics [

35,

36]. Although its routine use in everyday practice is variable, the score has been widely adopted in clinical trials and longitudinal studies as a structured way to monitor response to therapies such as anti-TNF agents. Subsequent work has proposed modified versions of the van Assche index and alternative MRI-based scoring systems, aiming to improve sensitivity to change and to correlate more closely with clinical and patient-reported outcomes. A significant recent advancement is the MAGNIFI-CD index, a novel MRI-based scoring system specifically designed to refine the evaluation of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease by integrating both morphological and inflammatory biomarkers into a unified framework. The MAGNIFI-CD score systematically quantifies active inflammatory features—including mural and perilesional enhancement patterns, diffusion-weighted imaging characteristics, and the presence of inflammatory oedema—alongside established structural descriptors. Early validation studies suggest that the MIGNIFI-CD index demonstrates superior sensitivity to change compared with traditional scoring systems and may better predict clinically meaningful outcomes, such as fistula healing or persistence of occult activity despite apparent clinical remission. By incorporating a broader range of MRI parameters and emphasising functional imaging markers, the MIGNIFI-CD index represents a promising tool for standardising radiologic assessment in both routine practice and clinical research, particularly within treat-to-target strategies. [

38,

39] MRI plays a central role in the evaluation of treatment response in perianal Crohn’s disease. Clinical closure of external openings does not necessarily equate to radiologic healing, and residual active tracts or small collections may persist despite apparently satisfactory external findings. Longitudinal MRI studies have demonstrated that, in patients treated with biologic therapies, perianal fistula tracts often decrease in caliber and contrast enhancement before undergoing complete fibrosis. Persistent T2 hyperintensity or ongoing contrast enhancement has been shown to predict disease relapse, even in the absence of overt clinical drainage [

29,

30]. For this reason, MRI is increasingly being integrated into treat-to-target strategies for perianal Crohn’s disease, with radiological improvement or healing recognized as a key therapeutic endpoint alongside clinical remission.

Other imaging modalities can complement MRI in selected situations. Endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) offers excellent spatial resolution near the anal canal and can be particularly useful in preoperative evaluation of sphincter integrity; however, its field of view is limited and it is less effective for complex or high fistulas. It requires also deep sedation in the presence of inflammatory perianal involvement. CT, by contrast, is generally reserved for acute presentations with suspected pelvic abscesses, sepsis, or other complications but it is clearly inferior to MRI for detailed fistula mapping and is avoided for repeated follow-up because of radiation exposure. [

8,

31].

In summary, MRI has become the cornerstone of perianal Crohn’s disease imaging. It provides an unparalleled combination of anatomical detail, functional information, and reproducible scoring systems that together guide both medical and surgical decision-making. The integration of MRI findings with clinical assessment, endoscopy, and biomarkers is essential for a truly comprehensive evaluation of this particularly challenging phenotype of Crohn’s disease.

Discussion

The choice between IUS, MRE, and computed tomography (CT or CT enterography, CTE) in Crohn’s disease depends strongly on the clinical context, the diagnostic question, and the patient’s need for repeat evaluation over time. Although these modalities can be viewed as complementary, each possesses strengths that make it uniquely suited to particular scenarios in the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway.

IUS has become a central tool for routine follow-up thanks to its accessibility to clinicians and gastroenterologists specifically, bedside availability, and complete absence of radiation. Its ability to provide real-time information about bowel wall thickness, vascularity, and peristalsis gives clinicians a rapid understanding of inflammatory activity. When performed by experienced operators, either radiologists or gastroenterologists, IUS is valuable for monitoring treatment response, often as part of tight-control strategies. However, its performance is reduced when the operator has limited experience, and even in expert hands it may be inadequate in cases of complex fistulizing disease, when bowel loops are located deep within the abdomen, in obese patients, or when proximal small-bowel involvement is suspected. For these reasons, although IUS is excellent for follow-up and for the early detection of changes in disease activity, it is not sufficient as a standalone modality for comprehensive disease mapping, initial diagnosis, or complete disease staging.

MRE remains the most comprehensive modality for both initial diagnosis and staging or re-staging Crohn’s disease

. Its multiparametric nature allows simultaneous assessment of bowel wall thickness, mural oedema, contrast enhancement patterns, transmural inflammation, mesenteric vascularity, and perienteric inflammatory changes. These features make it especially powerful for characterizing disease activity and for distinguishing inflammatory from fibrotic strictures, an essential task that strongly influences medical versus surgical management. MRE is also the preferred technique for identifying penetrating complications such as sinus tracts, fistulas, and abscesses, particularly when these are located in the mesentery or retroperitoneum. Because it avoids ionizing radiation, MRE is well suited for patients with long disease duration and for younger individuals who require frequent re-evaluation. It is also the preferred modality in long-term surveillance, especially in patients with longstanding small-bowel disease who are at risk for complications such as small-bowel neoplasia or progressive wall thickening of uncertain significance. The limitations of MRE relate mainly to availability, cost, examination duration, and the need for bowel preparation and patient cooperation. CT, particularly CT Enterography, retains a critical and irreplaceable role in acute care settings

. In the emergency context, where perforation, severe obstruction, abscesses, or other life-threatening complications must be identified quickly, CT is unquestionably the most efficient modality. Its rapid acquisition, extensive availability, and excellent spatial resolution make it the preferred investigation when patients present with severe abdominal pain, fever, systemic toxicity, or suspected sepsis. While CT offers excellent visualization of extramural disease and penetrating complications, its use outside the emergency setting is limited by exposure to ionising radiation, which is a major consideration in the typically young Crohn’s population. As a result, outside of acute situations or cases requiring rapid triage, CT is usually reserved for patients who cannot undergo MRE or when MRE is not available in a clinically acceptable timeframe. In selected cases, particularly in surveillance of unexplained small-bowel wall thickening or when small-bowel polyps are suspected, CT enterography may complement MRE, although this is relatively uncommon (

Table 3).

In routine clinical practice, to conclude, the three modalities fall into a clear, though flexible, pattern: IUS is the preferred tool for frequent monitoring and routine follow-up; MRE is the central modality for comprehensive staging, restaging, and evaluation of complications; CT/ CTE is indispensable in emergencies or when rapid decision-making is required. In patients with long-standing disease, MRE becomes particularly important during surveillance due to its ability to detect subtle structural changes, while CT may be used selectively when MRE results are inconclusive or when specific luminal abnormalities such as small-bowel polyps require further evaluation. Thus, although these imaging techniques overlap in diagnostic capability, each occupies a distinct role shaped by its strengths and limitations. Their integrated use forms the foundation of modern, individualized imaging strategies in Crohn’s disease.