Submitted:

27 January 2026

Posted:

28 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. CIE Exposure Resulted in Comparable BEC Levels in Males and Females

2.2. Differences in Cytokine Gene Expression in the Brain of CIE Exposed Male and Female Mice

2.3. CIE Exposure Decreases Pericyte Coverage in Male Mice, Which Was Preserved on P2X7R Inhibition

2.4. Sex-Specific Modulation of Serum Cytokines by CIE Exposure

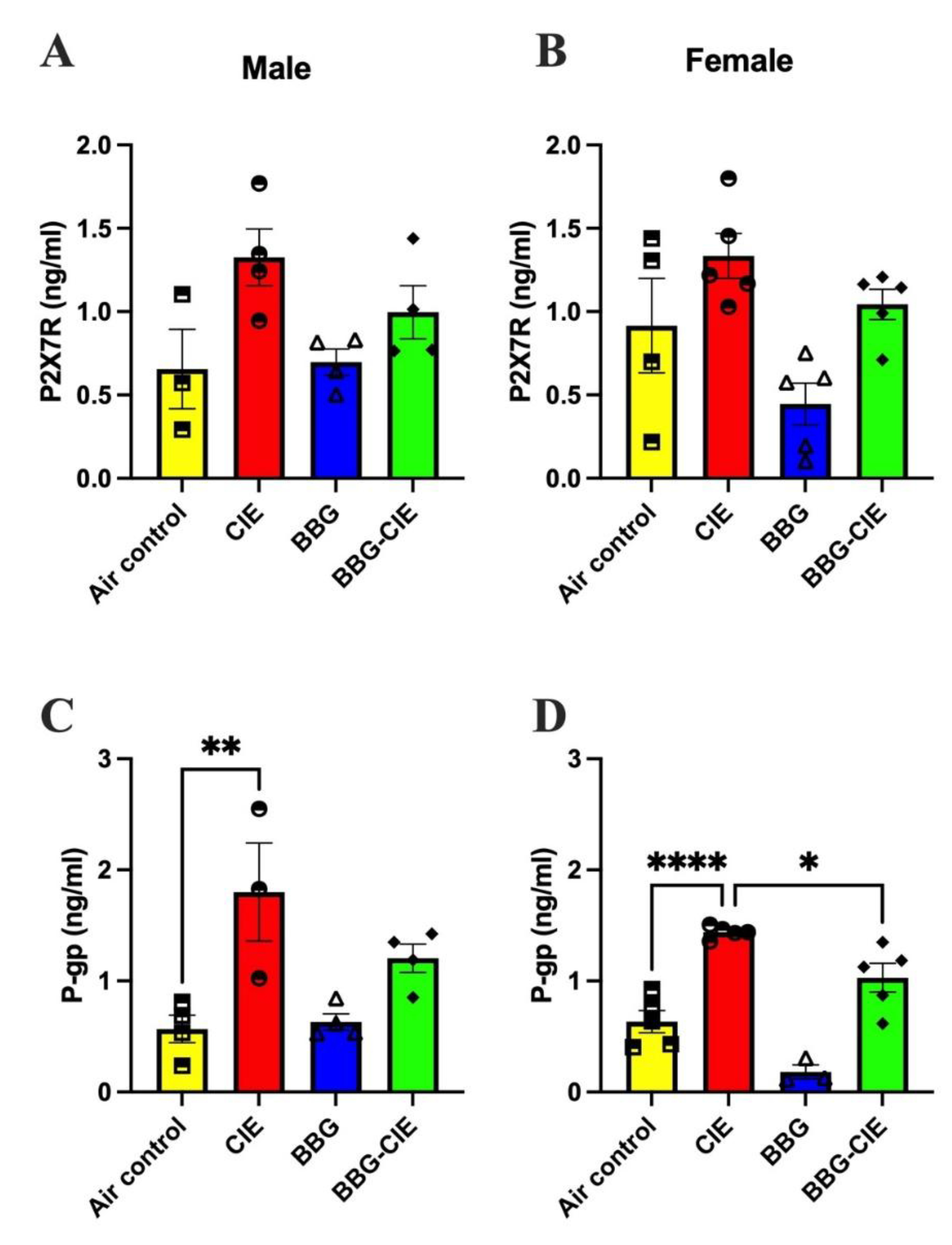

2.5. No Sex Difference in CIE-Induced Serum P2X7R Levels

2.3. P-Glycoprotein Levels Are Similarly Elevated in Male and Female CIE Exposed Mice

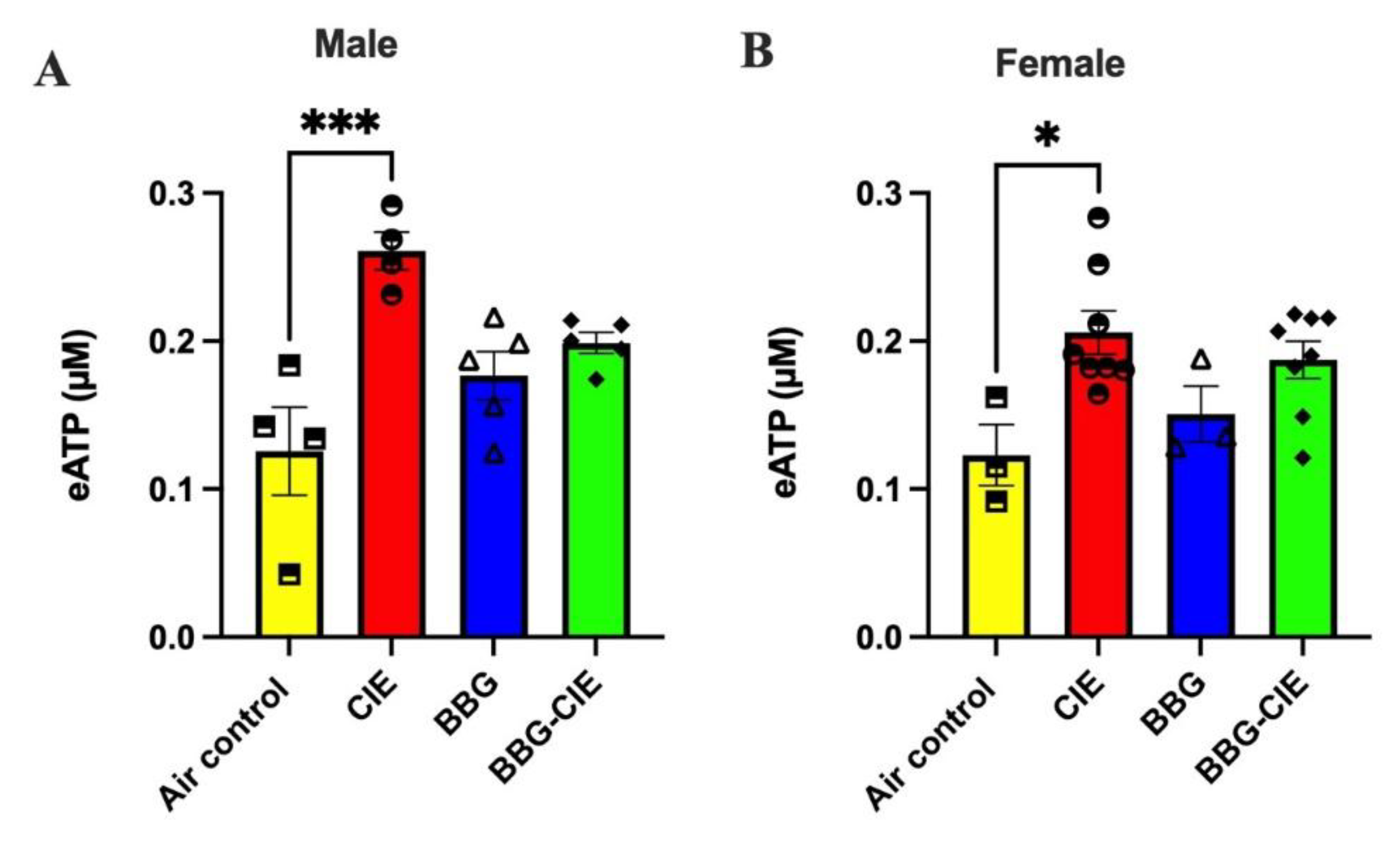

2.6. Increased Release of ATP in Serum (eATP) Is Similar in Male and Female CIE Exposed Mice

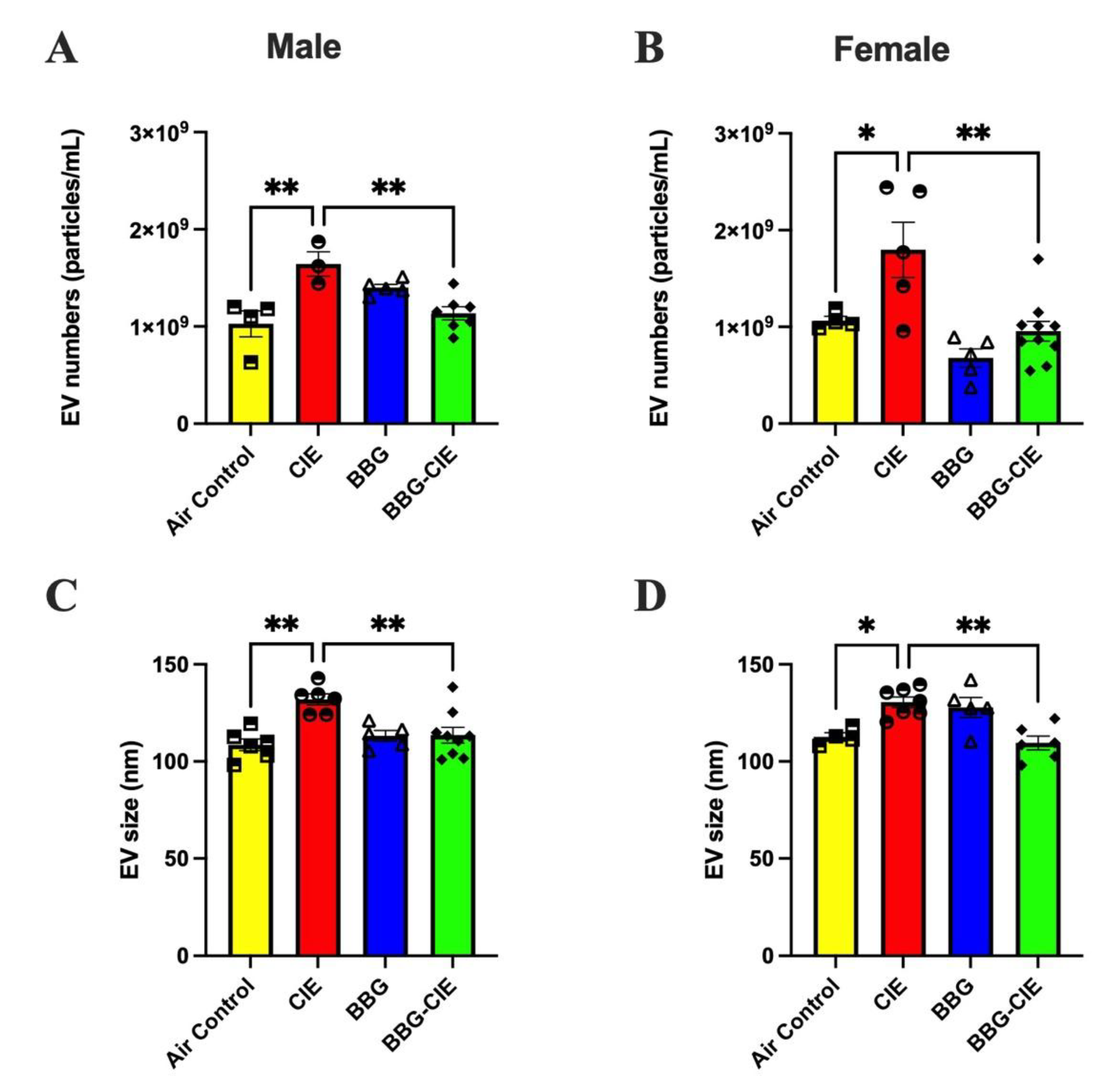

2.7. No Sex Bias in CIE-Induced EV Release and P2X7R Inhibition Effect

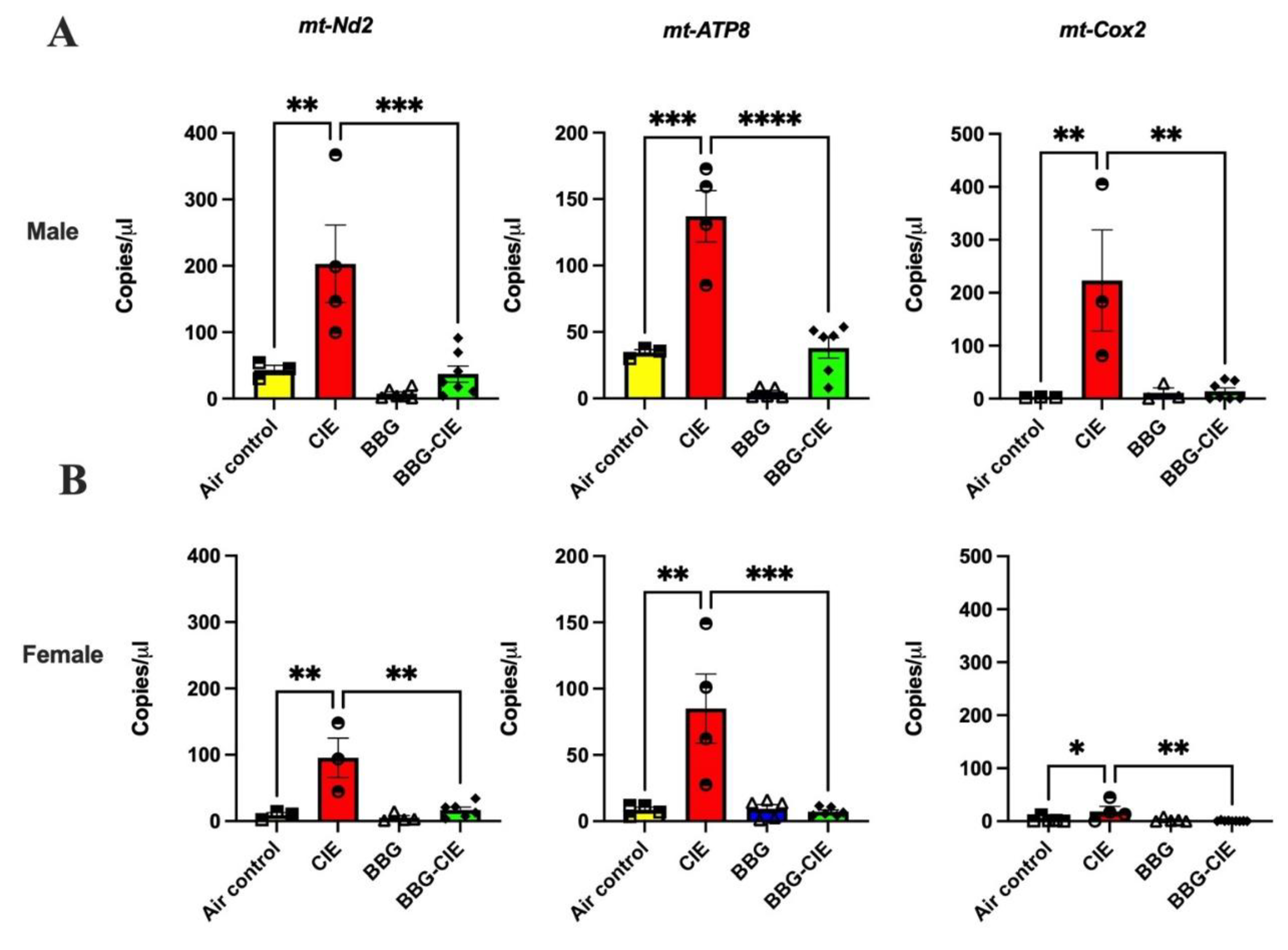

2.8. CIE Exposure Induces Similar EV mtDNA Signature in Male and Female Mice and Similar Changes After P2X7R Blockade

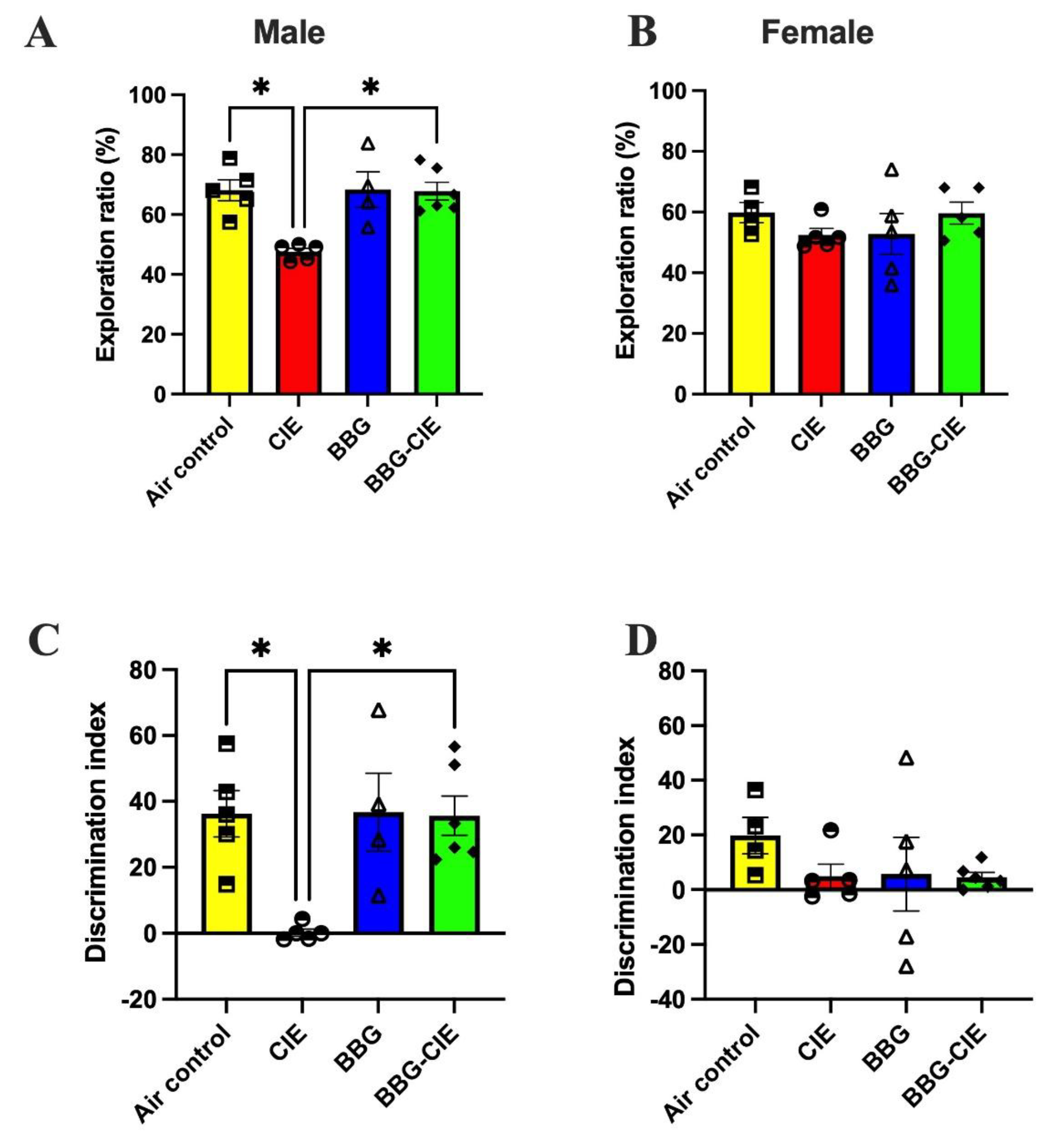

2.9. Sex Bias in Spatial Memory Performance in CIE Exposed Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Experimental Group

4.2. CIE Exposure

4.3. BEC Determination

4.4. qPCR Assay

4.5. Immunohistochemistry and Image Analysis

4.6. Multiplex Detection of Serum Proinflammatory Markers

4.7. EV Isolation and Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

4.8. Quantification of Serum P2X7R Levels

4.9. Serum P-gp Measurement

4.10. ATP Quantification in Serum

4.11. EV-DNA Quantification and Digital PCR Analysis

4.12. OPT

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| EV | Extracellular vesicle |

| CIE | Chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE) |

| BBG | Brilliant Blue G |

| BEC | Blood ethanol concentration |

| eATP | Extracellular ATP |

| P7X7R | Purinergic receptor P2X7 |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| NLRP3 | Nod-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 |

| EtOH | Ethanol |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| mt-ATP8 | Mitochondrially encoded ATP synthase membrane subunit 8 |

| mt-ND2 | NADH dehydrogenase 2 |

| mt-COX2 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit II |

| mt-RNR2 | 16S ribosomal RNA |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| KC/GRO | Keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC)/human growth-regulated oncogene (GRO) |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IP10 | Interferon-gamma inducible protein 10 |

| MIP-1 | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1 alpha |

References

- Esser MB SA, Liu Y, Naimi TS: Deaths from Excessive Alcohol Use — United States, 2016–2021. In.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.; 2024.

- Alcohol-Related Disease Impact application .

- Global status report on alcohol and health and treatment of substance use disorders. In.: 24-78.

- Vore, AS; Deak, T. Alcohol, inflammation, and blood-brain barrier function in health and disease across development . Int Rev Neurobiol 2022, 161, 209–249. [Google Scholar]

- Carrino, D; Branca, JJV; Becatti, M; Paternostro, F; Morucci, G; Gulisano, M; Di Cesare Mannelli, L; Pacini, A. Alcohol-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Impairment: An In Vitro Study . International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(5), 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crews, FT; Nixon, K. Mechanisms of neurodegeneration and regeneration in alcoholism . Alcohol Alcohol 2009, 44(2), 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, F; Nakagawa, S; Matsumoto, J; Dohgu, S. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Amplifies the Development of Neuroinflammation: Understanding of Cellular Events in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells for Prevention and Treatment of BBB Dysfunction . Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 661838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lékó, AH; Ray, LA; Leggio, L. The vicious cycle between (neuro)inflammation and alcohol use disorder: An opportunity to develop new medications? . Alcohol Clin Exp Res (Hoboken) 2023, 47(5), 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, FT; Lawrimore, CJ; Walter, TJ; Coleman, LG, Jr. : The role of neuroimmune signaling in alcoholism. Neuropharmacology 2017, 122, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, FT; Sarkar, DK; Qin, L; Zou, J; Boyadjieva, N; Vetreno, RP. Neuroimmune Function and the Consequences of Alcohol Exposure . Alcohol Res 2015, 37(2), 331-341, 344-351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y; Zhu, Y; Wang, J; Dong, L; Liu, S; Li, S; Wu, Q. Purinergic signaling: A gatekeeper of blood-brain barrier permeation . Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1112758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuemei Wang† YZ, Junmeng Wang, Longcong Dong,, Shuqing Liu SLaQW: Purinergic signaling: A gatekeeper of blood-brain barrier permeation. Frontiers in pharmacology 2023.

- Burnstock, G. Purinergic Signalling and Neurological Diseases: An Update . CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets - CNS & Neurological Disorders) 2017, 16(3), 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Adinolfi, E; Giuliani, AL; De Marchi, E; Pegoraro, A; Orioli, E; Di Virgilio, F. The P2X7 receptor: A main player in inflammation . Biochemical Pharmacology 2018, 151, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Giacomelli, Á; Petiz, LL; Andrejew, R; Turrini, N; Silva, JB; Sack, U; Ulrich, H. Role of P2X7 Receptors in Immune Responses During Neurodegeneration . Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes P: P2X7 Receptors Amplify CNS Damage in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(17).

- Takenouchi, T; Tsukimoto, M; Iwamaru, Y; Sugama, S; Sekiyama, K; Sato, M; Kojima, S; Hashimoto, M; Kitani, H. Extracellular ATP induces unconventional release of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from microglial cells . Immunol Lett 2015, 167(2), 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, M; Gabrielli, M; Adinolfi, E; Verderio, C. Role of ATP in Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Dynamics . Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F; Lombardi, M; Prada, I; Gabrielli, M; Joshi, P; Cojoc, D; Franck, J; Fournier, I; Vizioli, J; Verderio, C. ATP Modifies the Proteome of Extracellular Vesicles Released by Microglia and Influences Their Action on Astrocytes . Front Pharmacol 2017, 8, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golia, MT; Gabrielli, M; Verderio, C. P2X(7) Receptor and Extracellular Vesicle Release . Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekala, N; Trivedi, J; Bhoj, P; Togre, N; Rom, S; Sriram, U; Persidsky, Y. Alcohol and e-cigarette damage alveolar-epithelial barrier by activation of P2X7r and provoke brain endothelial injury via extracellular vesicles . Cell Communication and Signaling 2024, 22(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togre, NS; Mekala, N; Bhoj, PS; Mogadala, N; Winfield, M; Trivedi, J; Grove, D; Kotnala, S; Rom, S; Sriram, U; et al. Neuroinflammatory responses and blood–brain barrier injury in chronic alcohol exposure: role of purinergic P2 × 7 Receptor signaling . Journal of Neuroinflammation 2024, 21(1), 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitzemann, R; Bergeson, SE; Berman, AE; Bubier, JA; Chesler, EJ; Finn, DA; Hein, M; Hoffman, P; Holmes, A; Kisby, BR; et al. Sex Differences in the Brain Transcriptome Related to Alcohol Effects and Alcohol Use Disorder . Biol Psychiatry 2022, 91(1), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantoni, A; La Paglia, N; De Maria, N; Emanuele, MA; Emanuele, NV; Idilman, R; Harig, J; Van Thiel, DH. Influence of sex hormonal status on alcohol-induced oxidative injury in male and female rat liver . Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000, 24(9), 1467–1473. [Google Scholar]

- Tsermpini, EE; Plemenitaš Ilješ, A; Dolžan, V. Alcohol-Induced Oxidative Stress and the Role of Antioxidants in Alcohol Use Disorder: A Systematic Review . Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, EJ; Messingham, KA. Influence of alcohol and gender on immune response . Alcohol Res Health 2002, 26(4), 257–263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cruz, B; Borgonetti, V; Bajo, M; Roberto, M. Sex-dependent factors of alcohol and neuroimmune mechanisms . Neurobiology of Stress 2023, 26, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, K; Yazzie, S; Edeh, O; Grimes, M; Dixson, C; Jacquez, Q; Zychowski, KE. Neuroinflammation is dependent on sex and ovarian hormone presence following acute woodsmoke exposure . Scientific Reports 2024, 14(1), 12995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A; Vegeto, E; Poletti, A; Maggi, A. Estrogens, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegeneration . Endocr Rev 2016, 37(4), 372–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, R; Fick, J; Elesinnla, A; Waddell, J; Kristian, T. Sexual Dimorphism of Ethanol-Induced Mitochondrial Dynamics in Purkinje Cells . International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(24), 13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, ME; Metzger, DB. A sex difference in oxidative stress and behavioral suppression induced by ethanol withdrawal in rats . Behav Brain Res 2016, 314, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, M; Baliño, P; Aragón, CMG; Guerri, C. Cytokines and chemokines as biomarkers of ethanol-induced neuroinflammation and anxiety-related behavior: Role of TLR4 and TLR2 . Neuropharmacology 2015, 89, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varodayan, FP; Pahng, AR; Davis, TD; Gandhi, P; Bajo, M; Steinman, MQ; Kiosses, WB; Blednov, YA; Burkart, MD; Edwards, S; et al. Chronic ethanol induces a pro-inflammatory switch in interleukin-1β regulation of GABAergic signaling in the medial prefrontal cortex of male mice . Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2023, 110, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, PE; Rutt, LN; Kaufman, ML; Busquet, N; Kovacs, EJ; McCullough, RL. Binge ethanol exposure in advanced age elevates neuroinflammation and early indicators of neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment in female mice . Brain Behav Immun 2024, 116, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, CJ; Phelan, KD; Douglas, JC; Wagoner, G; Johnson, JW; Xu, J; Phelan, PS; Drew, PD. Effects of ethanol on immune response in the brain: region-specific changes in adolescent versus adult mice . Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014, 38(2), 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Guo S, Huang D, Hu D, Wu Y, Zhou W, Song W, Zhu L-Q: Chronic Alcohol Exposure Alters Gene Expression and Neurodegeneration Pathways in the Brain of Adult Mice. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022, 86(1), 315–331. [CrossRef]

- Qin, L; He, J; Hanes, RN; Pluzarev, O; Hong, J-S; Crews, FT. Increased systemic and brain cytokine production and neuroinflammation by endotoxin following ethanol treatment . Journal of Neuroinflammation 2008, 5(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, PP; Morel, C; Ambade, A; Iracheta-Vellve, A; Kwiatkowski, E; Satishchandran, A; Furi, I; Cho, Y; Gyongyosi, B; Catalano, D; et al. Chronic alcohol-induced neuroinflammation involves CCR2/5-dependent peripheral macrophage infiltration and microglia alterations . J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17(1), 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C; Conigrave, JH; Lewohl, J; Haber, P; Morley, KC. Alcohol use disorder and circulating cytokines: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2020, 89, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, AL; Berchan, M; Sanz, JM; Passaro, A; Pizzicotti, S; Vultaggio-Poma, V; Sarti, AC; Di Virgilio, F. The P2X7 Receptor Is Shed Into Circulation: Correlation With C-Reactive Protein Levels . Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vultaggio-Poma, V; Sanz, JM; Amico, A; Violi, A; Ghisellini, S; Pizzicotti, S; Passaro, A; Papi, A; Libanore, M; Di Virgilio, F; et al. The shed P2X7 receptor is an index of adverse clinical outcome in COVID-19 patients . Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1182454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z; Luo, Y; Zhu, J; Jiang, D; Luo, Z; Wu, L; Li, J; Peng, S; Hu, J. Role of the P2 × 7 receptor in neurodegenerative diseases and its pharmacological properties . Cell & Bioscience 2023, 13(1), 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, J; Chmielewski, J; Hrycyna, CA. The roles of the human ATP-binding cassette transporters P-glycoprotein and ABCG2 in multidrug resistance in cancer and at endogenous sites: future opportunities for structure-based drug design of inhibitors . Cancer Drug Resist 2021, 4(4), 784–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandao-Burch, A; Key, ML; Patel, JJ; Arnett, TR; Orriss, IR. The P2X7 Receptor is an Important Regulator of Extracellular ATP Levels . Frontiers in Endocrinology 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzaferri, F; Ruiz-Ruiz, C; de Diego, AMG; de Pascual, R; Méndez-López, I; Cano-Abad, MF; Maneu, V; de los Ríos, C; Gandía, L; García, AG. The purinergic P2X7 receptor as a potential drug target to combat neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases . Medicinal Research Reviews 2020, 40(6), 2427–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, B; Pei, J; Li, H; Yang, G; Shi, X; Zhang, Z; Wang, H; Zheng, Z; Liu, Y; Zhang, J. Inhibition of P2X7R alleviates neuroinflammation and brain edema after traumatic brain injury by suppressing the NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway . Journal of Neurorestoratology 2024, 100106. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A; Biber, K. The microglial ATP-gated ion channel P2X7 as a CNS drug target . Glia 2016, 64(10), 1772–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Yu Z, Wang M, Kang X, Wu X, Yang F, Yang L, Sun S, Wu L-a: Enhanced exosome secretion regulated by microglial P2X7R in the medullary dorsal horn contributes to pulpitis-induced pain. Cell & Bioscience 2025, 15(1), 28.

- Mekala, N; Gheewala, N; Rom, S; Sriram, U; Persidsky, Y. Blocking of P2X7r Reduces Mitochondrial Stress Induced by Alcohol and Electronic Cigarette Exposure in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells . Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikot, RT; Bedi, B; Li, J; Yeligar, SM. Alcohol-induced mitochondrial DNA damage promotes injurious crosstalk between alveolar epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages . Alcohol 2019, 80, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, AP; Shadel, GS. Mitochondrial DNA in innate immune responses and inflammatory pathology . Nature Reviews Immunology 2017, 17(6), 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippai, D; Bala, S; Petrasek, J; Csak, T; Levin, I; Kurt-Jones, EA; Szabo, G. Alcohol-induced IL-1β in the brain is mediated by NLRP3/ASC inflammasome activation that amplifies neuroinflammation . J Leukoc Biol 2013, 94(1), 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K; Wang, H; Xu, M; Frank, JA; Luo, J. Role of MCP-1 and CCR2 in ethanol-induced neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the developing brain . Journal of Neuroinflammation 2018, 15(1), 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, KN; Douglas, JC; Rafferty, TM; Kane, CJM; Drew, PD. Ethanol Induces Neuroinflammation in a Chronic Plus Binge Mouse Model of Alcohol Use Disorder via TLR4 and MyD88-Dependent Signaling . Cells 2023, 12(16), 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso-Loeches, S; Pascual-Lucas, M; Blanco, AM; Sanchez-Vera, I; Guerri, C. Pivotal role of TLR4 receptors in alcohol-induced neuroinflammation and brain damage . J Neurosci 2010, 30(24), 8285–8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gano, A; Doremus-Fitzwater, TL; Deak, T. Sustained alterations in neuroimmune gene expression after daily, but not intermittent, alcohol exposure . Brain Res 2016, 1646, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, SD; Miller, MW. Effects of ethanol on transforming growth factor Β1-dependent and -independent mechanisms of neural stem cell apoptosis . Experimental Neurology 2011, 229(2), 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashayekhi-sardoo, H; Razazpour, F; Hakemi, Z; Hedayati-Moghadam, M; Baghcheghi, Y. Ethanol-Induced Depression: Exploring the Underlying Molecular Mechanisms . Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 2025, 45(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss A, Siddiqi M, Podder D, Scroger M, Vessey G, Martin K, Paperny N, Vo K, Astefanous A, Belachew N et al: Ethanol drinking sex-dependently alters cortical IL-1β synaptic signaling and cognitive behavior in mice. bioRxiv 2024:2024.2010.2008.617276.

- Barton, EA; Baker, C. Leasure JL: Investigation of Sex Differences in the Microglial Response to Binge Ethanol and Exercise. Brain Sci 2017, 7(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, M; Katsnelson, MA; Dubyak, GR; Pearlman, E. Neutrophil P2X7 receptors mediate NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent IL-1β secretion in response to ATP . Nature Communications 2016, 7(1), 10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C; She, Y; Huang, J; Liu, Y; Li, W; Zhang, C; Zhang, T; Yu, L. HMGB1-NLRP3-P2X7R pathway participates in PM2.5-induced hippocampal neuron impairment by regulating microglia activation . Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 239, 113664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrasek, J; Bala, S; Csak, T; Lippai, D; Kodys, K; Menashy, V; Barrieau, M; Min, SY; Kurt-Jones, EA; Szabo, G. IL-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates inflammasome-dependent alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice . J Clin Invest 2012, 122(10), 3476–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzasoma, L; Schmidt-Weber, CB; Fallarino, F. In Vitro Study of TLR4-NLRP3-Inflammasome Activation in Innate Immune Response . Methods Mol Biol 2023, 2700, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Adinolfi, E; Cirillo, M; Woltersdorf, R; Falzoni, S; Chiozzi, P; Pellegatti, P; Callegari, MG; Sandonà, D; Markwardt, F; Schmalzing, G; et al. Trophic activity of a naturally occurring truncated isoform of the P2X7 receptor . Faseb j 2010, 24(9), 3393–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, L; Ostrovskaya, O; Lieu, D; Davies, DL. Ethanol differentially modulates P2X4 and P2X7 receptor activity and function in BV2 microglial cells . Neuropharmacology 2018, 128, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, L; Khoja, S; Rodgers, KE; Alkana, RL; Tsukamoto, H; Davies, DL. Chronic ethanol exposure combined with high fat diet up-regulates P2X7 receptors that parallels neuroinflammation and neuronal loss in C57BL/6J mice . J Neuroimmunol 2015, 285, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumenthaler, MS; Taylor, JL; O'Hara, R; Yesavage, JA. Gender differences in moderate drinking effects . Alcohol Res Health 1999, 23(1), 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Goral, J; Karavitis, J; Kovacs, EJ. Exposure-dependent effects of ethanol on the innate immune system . Alcohol 2008, 42(4), 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rom, S; Zuluaga-Ramirez, V; Gajghate, S; Seliga, A; Winfield, M; Heldt, NA; Kolpakov, MA; Bashkirova, YV; Sabri, AK; Persidsky, Y. Hyperglycemia-Driven Neuroinflammation Compromises BBB Leading to Memory Loss in Both Diabetes Mellitus (DM) Type 1 and Type 2 Mouse Models . Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56(3), 1883–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haorah, J; Knipe, B; Leibhart, J; Ghorpade, A; Persidsky, Y. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress in brain endothelial cells causes blood-brain barrier dysfunction . J Leukoc Biol 2005, 78(6), 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, CE; Wood, SK. Stress- and drug-induced neuroimmune signaling as a therapeutic target for comorbid anxiety and substance use disorders . Pharmacol Ther 2022, 239, 108212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcia, MA; Bonsall, DR; Bloomfield, PS; Selvaraj, S; Barichello, T; Howes, OD. Stress and neuroinflammation: a systematic review of the effects of stress on microglia and the implications for mental illness . Psychopharmacology 2016, 233(9), 1637–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J; Crews, FT. Increased MCP-1 and microglia in various regions of the human alcoholic brain . Exp Neurol 2008, 210(2), 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savio, LEB; de Andrade Mello, P; da Silva, CG; Coutinho-Silva, R. The P2X7 Receptor in Inflammatory Diseases: Angel or Demon? . Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Virgilio, F; Dal Ben, D; Sarti, AC; Giuliani, AL; Falzoni, S. The P2X7 Receptor in Infection and Inflammation . Immunity 2017, 47(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B; Hartz, AM; Miller, DS. Tumor necrosis factor alpha and endothelin-1 increase P-glycoprotein expression and transport activity at the blood-brain barrier . Mol Pharmacol 2007, 71(3), 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, DS; Bauer, B; Hartz, AM. Modulation of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier: opportunities to improve central nervous system pharmacotherapy . Pharmacol Rev 2008, 60(2), 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Cuevas, FG; Martínez-Ramírez, AS; Robles-Martínez, L; Garay, E; García-Carrancá, A; Pérez-Montiel, D; Castañeda-García, C; Arellano, RO. Paracrine stimulation of P2X7 receptor by ATP activates a proliferative pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells . J Cell Biochem 2014, 115(11), 1955–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, NA; Muskiewicz, DE; Terrero, D; Malla, S; Hall, FS; Tiwari, AK. The Effects of Drugs of Abuse on ABC Transporters . In Handbook of Substance Misuse and Addictions: From Biology to Public Health.; Patel, VB, Preedy, VR, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Dong W, Lin X, Xu K, Li K, Xiong S, Wang Z, Nie X, Bian J-S: Disruption of the Na+/K+-ATPase-purinergic P2X7 receptor complex in microglia promotes stress-induced anxiety. Immunity 2024, 57(3), 495–512.e411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S; Kondapalli, K; Rasheed, N. Chu X-P: Commentary: P2X7 receptor modulation is a viable therapeutic target for neurogenic pain with concurrent sleep disorders. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2023, 17–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Territo, PR; Zarrinmayeh, H. P2X(7) Receptors in Neurodegeneration: Potential Therapeutic Applications From Basic to Clinical Approaches . Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 617036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, D; Reyes, RE; Baghram, A; Davies, DL; Asatryan, L. P2X7 Receptor Antagonist A804598 Inhibits Inflammation in Brain and Liver in C57BL/6J Mice Exposed to Chronic Ethanol and High Fat Diet . Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 2019, 14(2), 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winham, SJ; Bobo, WV; Liu, J; Coombes, B; Backlund, L; Frye, MA; Biernacka, JM; Schalling, M; Lavebratt, C. Sex-specific effects of gain-of-function P2RX7 variation on bipolar disorder . Journal of Affective Disorders 2019, 245, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, AE; Piazza, MK; Vore, AS; Deak, MM; Varlinskaya, EI; Deak, T. Assessment of neuroinflammation in the aging hippocampus using large-molecule microdialysis: Sex differences and role of purinergic receptors . Brain Behav Immun 2021, 91, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crain, JM; Watters, JJ. Microglial P2 Purinergic Receptor and Immunomodulatory Gene Transcripts Vary By Region, Sex, and Age in the Healthy Mouse CNS . Transcr Open Access 2015, 3(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guneykaya, D; Ivanov, A; Hernandez, DP; Haage, V; Wojtas, B; Meyer, N; Maricos, M; Jordan, P; Buonfiglioli, A; Gielniewski, B; et al. Transcriptional and Translational Differences of Microglia from Male and Female Brains . Cell Reports 2018, 24(10), 2773–2783.e2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereiter, DA; Rahman, M; Ahmed, F; Thompson, R; Luong, N; Olson, JK. Title: P2x7 Receptor Activation and Estrogen Status Drive Neuroinflammatory Mechanisms in a Rat Model for Dry Eye . Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 827244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhm, F; Afonyushkin, T; Resch, U; Obermayer, G; Rohde, M; Penz, T; Schuster, M; Wagner, G; Rendeiro, AF; Melki, I; et al. Mitochondria Are a Subset of Extracellular Vesicles Released by Activated Monocytes and Induce Type I IFN and TNF Responses in Endothelial Cells . Circ Res 2019, 125(1), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falzoni, S; Vultaggio-Poma, V; Chiozzi, P; Tarantini, M; Adinolfi, E; Boldrini, P; Giuliani, AL; Morciano, G; Tang, Y; Gorecki, DC; et al. The P2X7 Receptor is a Master Regulator of Microparticle and Mitochondria Exchange in Mouse Microglia . Function (Oxf) 2024, 5(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Daré, B; Victoni, T; Bodin, A; Vlach, M; Vene, E; Loyer, P; Lagente, V; Gicquel, T. Ethanol upregulates the P2X7 purinergic receptor in human macrophages . Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology 2019, 33(1), 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Buzas EI: The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology 2023, 23(4), 236–250. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, PD; Morelli, AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles . Nat Rev Immunol 2014, 14(3), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M; Siljander, PR; Andreu, Z; Zavec, AB; Borràs, FE; Buzas, EI; Buzas, K; Casal, E; Cappello, F; Carvalho, J; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions . J Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z; Tong, B; Ke, W; Yang, C; Wu, X; Lei, M. Extracellular vesicles as carriers for mitochondria: Biological functions and clinical applications . Mitochondrion 2024, 78, 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B; Momen-Heravi, F; Furi, I; Kodys, K; Catalano, D; Gangopadhyay, A; Haraszti, R; Satishchandran, A; Iracheta-Vellve, A; Adejumo, A; et al. Extracellular vesicles from mice with alcoholic liver disease carry a distinct protein cargo and induce macrophage activation through heat shock protein 90 . Hepatology 2018, 67(5), 1986–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B; Momen-Heravi, F; Kodys, K; Szabo, G. MicroRNA Cargo of Extracellular Vesicles from Alcohol-exposed Monocytes Signals Naive Monocytes to Differentiate into M2 Macrophages* . Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291(1), 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, F; Montesinos, J; Ureña-Peralta, JR; Guerri, C; Pascual, M. TLR4 participates in the transmission of ethanol-induced neuroinflammation via astrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles . J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16(1), 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J; Walter, TJ; Barnett, A; Rohlman, A; Crews, FT; Coleman, LG. Ethanol Induces Secretion of Proinflammatory Extracellular Vesicles That Inhibit Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis Through G9a/GLP-Epigenetic Signaling . Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez, F; Montesinos, J; Area-Gomez, E; Guerri, C; Pascual, M. Ethanol Induces Extracellular Vesicle Secretion by Altering Lipid Metabolism through the Mitochondria-Associated ER Membranes and Sphingomyelinases . Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22(16). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollen-Bittle, N; Roseborough, AD; Wang, W; Wu, JD; Whitehead, SN. Connecting cellular mechanisms and extracellular vesicle cargo in traumatic brain injury . Neural Regen Res 2024, 19(10), 2119–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berumen Sánchez, G; Bunn, KE; Pua, HH; Rafat, M. Extracellular vesicles: mediators of intercellular communication in tissue injury and disease . Cell Communication and Signaling 2021, 19(1), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J; Cao, H; Rodrigues, RM; Xu, M; Ren, T; He, Y; Hwang, S; Feng, D; Ren, R; Yang, P; et al. Chronic-plus-binge alcohol intake induces production of proinflammatory mtDNA-enriched extracellular vesicles and steatohepatitis via ASK1/p38MAPKα-dependent mechanisms . JCI Insight 2020, 5(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabas, N; Palmer, S; Mitchell, L; Ismail, S; Gohlke, A; Riley, JS; Tait, SWG; Gammage, P; Soares, LL; Macpherson, IR; et al. PINK1 drives production of mtDNA-containing extracellular vesicles to promote invasiveness . J Cell Biol 2021, 220(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, LE; Shadel, GS. Mitochondrial DNA Release in Innate Immune Signaling . Annu Rev Biochem 2023, 92, 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, P; Savini, C; Kurelac, I; Chang, Q; Amato, LB; Strillacci, A; Stepanova, A; Iommarini, L; Mastroleo, C; Daly, L; et al. Packaging and transfer of mitochondrial DNA via exosomes regulate escape from dormancy in hormonal therapy-resistant breast cancer . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114(43), E9066–E9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazo, S; Noren Hooten, N; Green, J; Eitan, E; Mode, NA; Liu, QR; Zonderman, AB; Ezike, N; Mattson, MP; Ghosh, P; et al. Mitochondrial DNA in extracellular vesicles declines with age . Aging Cell 2021, 20(1), e13283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J; Kim, HS; Chung, JH; Kim, J; et al. Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial DNA release and activation of the cGAS–STING pathway. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55(3), 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byappanahalli, AM; Noren Hooten, N; Vannoy, M; Mode, NA; Ezike, N; Zonderman, AB; Evans, MK. Mitochondrial DNA and inflammatory proteins are higher in extracellular vesicles from frail individuals . Immunity & Ageing 2023, 20(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, M; Khokha, R. Metalloproteinases in extracellular vesicles . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2017, 1864(11, Part A), 1989–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, F; Pravettoni, E; Colombo, A; Schenk, U; Möller, T; Matteoli, M; Verderio, C. Astrocyte-Derived ATP Induces Vesicle Shedding and IL-1β Release from Microglia1 . The Journal of Immunology 2005, 174(11), 7268–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X; Liu, S; Lu, Y; Wan, M; Cheng, J; Liu, J. MitoEVs: A new player in multiple disease pathology and treatment . Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 2023, 12(4), 12320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y; Xu, MJ; Koritzinsky, EH; Zhou, Z; Wang, W; Cao, H; Yuen, PS; Ross, RA; Star, RA; Liangpunsakul, S; et al. Mitochondrial DNA-enriched microparticles promote acute-on-chronic alcoholic neutrophilia and hepatotoxicity . JCI Insight 2017, 2(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, AP; Khoury-Hanold, W; Staron, M; Tal, MC; Pineda, CM; Lang, SM; Bestwick, M; Duguay, BA; Raimundo, N; MacDuff, DA; et al. Mitochondrial DNA stress primes the antiviral innate immune response . Nature 2015, 520(7548), 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togre, NS; Bhoj, PS; Mekala, N; Hancock, R; Trivedi, J; Persidsky, Y. Purinergic and extracellular vesicle signaling in alcohol-induced blood–brain barrier breakdown and neuroimmune activation . Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2025, 130, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, JS; Quarato, G; Cloix, C; Lopez, J; O'Prey, J; Pearson, M; Chapman, J; Sesaki, H; Carlin, LM; Passos, JF; et al. Mitochondrial inner membrane permeabilisation enables mtDNA release during apoptosis . Embo j 2018, 37(17). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, DB; Scaletty, S; Trapp, S; Schreiber, A; Rossmann, G; Imhoff, B; Petersilka, Q; Kastner, A; Pauly, J; Nixon, K. Chronic intermittent ethanol exposure during adolescence produces sex- and age-dependent changes in anxiety and cognition without changes in microglia reactivity late in life . Front Behav Neurosci 2023, 17, 1223883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A; Zhang, J. Neuroinflammation, memory, and depression: new approaches to hippocampal neurogenesis . Journal of Neuroinflammation 2023, 20(1), 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrousse, VF; Costes, L; Aubert, A; Darnaudéry, M; Ferreira, G; Amédée, T; Layé, S. Impaired interleukin-1beta and c-Fos expression in the hippocampus is associated with a spatial memory deficit in P2X(7) receptor-deficient mice . PLoS One 2009, 4(6), e6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, AH; Wu, M; Shaftel, SS; Graham, KA; O'Banion, MK. Sustained expression of interleukin-1beta in mouse hippocampus impairs spatial memory . Neuroscience 2009, 164(4), 1484–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J; Fillion, ML; LeBlanc, AC. Caspase-1 inhibition improves cognition without significantly altering amyloid and inflammation in aged Alzheimer disease mice . Cell Death Dis 2022, 13(10), 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, GA; Tong, L; Smith, ED; Cotman, CW. TNFα and IL-1β but not IL-18 Suppresses Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation Directly at the Synapse . Neurochem Res 2019, 44(1), 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mygind, L; Bergh, MS; Tejsi, V; Vaitheeswaran, R; Lambertsen, KL; Finsen, B. Metaxas A: Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Is Required for Spatial Learning and Memory in Male Mice under Physiological, but Not Immune-Challenged Conditions. Cells 2021, 10(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa AE, Garcia-Bueno B, Leza JC, Madrigal JL: CCL2/MCP-1 modulation of microglial activation and proliferation. J Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 77. [CrossRef]

- Nie, W; Yue, Y; Hu, J. The role of monocytes and macrophages in the progression of Alzheimer's disease . Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1590909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neniskyte, U; Gross, CT. Errant gardeners: glial-cell-dependent synaptic pruning and neurodevelopmental disorders . Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2017, 18(11), 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyapati, RK; Tamborska, A; Dorward, DA; Ho, GT. Advances in the understanding of mitochondrial DNA as a pathogenic factor in inflammatory diseases . F1000Res 2017, 6, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Carvalho, I; Almeida-Santos, Gd; Bomfim, CCB; Souza, PCd; Silva, JCSe; Melo, BMSd; Amaral, EP; Cione, MVP; Lasunskaia, E; Hirata, MH; et al. P2x7 Receptor Signaling Blockade Reduces Lung Inflammation and Necrosis During Severe Experimental Tuberculosis . Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y-C; Chang, Y-W; Lai, CP; Chang, N-W; Huang, C-H; Chen, C-S; Huang, H-C; Juan, H-F. Ectopic ATP synthase stimulates the secretion of extracellular vesicles in cancer cells . Communications Biology 2023, 6(1), 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lluch, G; Hunt, N; Jones, B; Zhu, M; Jamieson, H; Hilmer, S; Cascajo, MV; Allard, J; Ingram, DK; Navas, P; et al. Calorie restriction induces mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetic efficiency . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103(6), 1768–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimmer, ME; Hernandez, PJ; Blackwell, J; Abel, T. Aging impairs hippocampus-dependent long-term memory for object location in mice . Neurobiol Aging 2012, 33(9), 2220–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denninger, JK; Smith, BM; Kirby, ED. : Novel Object Recognition and Object Location Behavioral Testing in Mice on a Budget. J Vis Exp 2018, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Murai, T; Okuda, S; Tanaka, T; Ohta, H. Characteristics of object location memory in mice: Behavioral and pharmacological studies . Physiology & Behavior 2007, 90(1), 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).