1. Introduction

Antifungal active packaging is a technological alternative for controlling postharvest fruit losses. It has been reported that approximately 30% of the fruit harvested worldwide is lost and never reaches the consumer’s plate, and one of the most significant reasons is postharvest attack by phytopathogenic fungi. Among the fungal sources of fresh spoilage are gray rot caused by

Botrytis cinerea, Rhizopus soft rot caused by

Rhizopus stolonifera, and sour rot caused by

Geotrichum candidum [

1]. When packaging is enhanced with a chemical compound that serves a specific function, such as controlling fungi, it is labeled as antifungal active packaging. In this research, we aim to prevent the growth of phytopathogenic fungi that degrade blueberry quality using active packaging. Antifungal active packaging has been developed to control fungal rots in various fruits, ranging from sachets to prevent rots in avocados, to cardboard boxes that avoid rots in rambutans, pads that prevent rots in grapes, and films that prevent rots in mangoes [

2,

3,

4,

5].

Blueberries (

Vaccinium corymbosum) are considered superfoods because of their rich content of bioactive compounds like anthocyanin’s, chlorogenic acid, and other flavonoids, which provide antioxidant capacity and health benefits. Anthocyanins account for approximately 84% of their phenolic compounds and are the primary contributors to their antioxidant activity. This berry contains fructose, glucose, fiber, vitamins, folate, essential minerals, and fatty acids, too. These nutrients help boost immunity and offer antidiabetic, antiaging, and cardioprotective effects, making them a valuable part of a healthy diet [

6]. The primary postharvest phytopathogens affecting blueberry fruits include gray mold (

B. cinerea), fruit rot (

Alternaria spp.), and anthracnose (

Colletotrichum spp.). Additionally, blueberries can be attacked by

Penicillium chrysogenum and

Fusarium oxysporum, which can cause losses of up to 20% of total production. In the international market, one ton of blueberries can be valued at up to

$14,000, resulting in a loss of

$58,000 because of pathogen attacks, representing a significant economic loss that could be mitigated through various postharvest pathogen control methods, such as antifungal active packaging [

7].

In developing antifungal active packaging, a future trend is the focus on sustainability. In this context, sustainability can be considered from two perspectives: the nature of the packaging materials and the nature of the active compounds, specifically in relation to the packaging material [

8]. Polylactic acid (PLA) is a biodegradable packaging material derived from the microbial fermentation of agricultural byproducts, which enables the formation of lactides. As a result, it serves as an excellent alternative to petrochemical-derived products. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved lactic acid monomer as a safe food ingredient, making PLA a green, low-toxicity polymer with respect to the active compound [

9]. There is a notable consumer trend toward foods as natural as possible, free of synthetic additives. To contribute to food safety without negatively affecting consumer health, active compounds of natural origin can be incorporated into the packaging formulation, derived from plants (herbs, spices), animals, mushrooms, enzymes, and microorganisms [

10]. Among the plant-derived antifungals, essential oils are notable. Citronella essential oil, an essential oil extracted from

Cymbopogon nardus,

its principal compounds are (R)-(+)-Citronellal, citronellol, geraniol, hedycaryol, and citronellyl acetate is recognized as safe by the FDA, and its antifungal properties have been tested against multiple phytopathogens [

11].

This research aimed to develop an active film based on polylactic acid and citronella oil to control the in vitro growth of phytopathogenic fungi that reduce blueberry shelf life.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Solvents and Reagents

The reactants used for the in vitro test were citronella essential oil (Parvitra, Michoacán, Mexico), potato dextrose agar (PDA, Becton, Dickon de México, Edo. de México, México), and distilled water (Surtilab, Michoacán, México). The reactives used in the film’s fabrication were the PLA (NatureWorks, Nebraska, USA), chloroform (Materiales y Abastos Especializados, Jalisco, Mexico), and Tween 80 (Azumex, Puebla, Mexico).

2.2. Fungal

Epicoccum nigrum, Alternaria alternata, and Cladosporium herbarum were isolated from blueberries at a production unit in Guanajuato, Mexico. The mycelium of these phytopathogens was cultivated on PDA. The fungi were isolated and characterized at the Phytopathology Laboratory of the Michoacan Agrifood Innovation and Development Center in Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico (geographical coordinates: 19.651806, -101.225836).

2.3. Films Fabrication and Characterization

2.3.1. Film Fabrication.

Films with different concentrations of citronella essential oil (7.5, 10, and 12.5% w/w) were prepared by casting. Chloroform was used as the solvent, and the film-forming solutions contained 2 g of PLA resin and 80 mL of chloroform. The solution was stirred for 6 h at room temperature. Citronella essential oil and 1% Tween 80 were added, and the mixture was stirred for 15 min. Afterward, 25 mL of the solution was poured into 8.5 cm-diameter Petri dishes and left to dry overnight. An extra formulation without citronella essential oil was produced (T0).

2.3.2. Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR).

The WVTR was determined according to ASTM E96 at 25±1 °C and 50±5% relative humidity (RH). Five replicates were carried out for each material. The results were expressed in g/m2.Day. Five cells with 30 g of CaCl2 were stored in a desiccator jar at 50%±5% RH. The films were weighed daily, and the results were plotted as a function of time (nine days).

2.3.3. Depth-Sensing Indentation

Nanomechanical testing was performed using nanoindentation with a G200 Agilent Nanoindenter and an XP head attachment. The experiments were conducted using a Berkovich diamond indenter with a tip radius of 20 ± 5 nm, a maximum load of 0.1 mN, a strain rate of 0.05/s, and a harmonic displacement and frequency of 1 nm and 75 Hz, respectively. The passion’s coefficient was ν = 0.33.

Before taking the measurements, the equipment was calibrated using a standard fused quartz sample to obtain the exact area function. A(h) and its respective parameters. Test parameters were as follows: the constants of the area function were: C

0= 24.07, C

1= −174.31, C

2= 6688.45, C

3= −26245.00, and C4= 19907.2. The measurement method was load-controlled to evaluate the stiffness using the Sneddon equation [

12]:

Where

β = 1.034 is the parameter for a Berkovich indenter,

Er is the reduced elastic modulus, and A is the contact area that is a function of the penetration depth or displacement,

h [

13]. The elastic modulus

(E) was calculated by considering the compliance of the specimen and the indenter tip combined in series, using the next equation:

Where

Ei is the elastic modulus of the diamond indenter,

E is the elastic modulus of the sample, vi is the Poisson’s ratio of the diamond indenter, and

v is the Poisson’s ratio of the specimen. Before the nanomechanical properties were measured, the equipment was calibrated using a standard fused quartz sample. The area function, A

c(h

c), adopts a polynomial form, once the adjustment of the standard curve on an

Ac(hc) curve has been carried out, represented by the following equation:

The calibration parameters were C0 = 24.01, C1 = -174.34, C2= 6831.44, C3 = -26436.00, and C4 = 18911.2.

2.4. In Vitro Antifungal Effect of Citronella Essential Oil and Active Films

In vitro assays were conducted to evaluate the antifungal effect of citronella essential oil and its active films. For the citronella essential oil test, agar plates (90 mm diameter) were inoculated with a 6 mm mycelial disc taken from the actively growing margin of 8-day-old cultures of the target phytopathogen. Three sterile filter paper discs (4 mm diameter) were placed on the agar surface and moistened with 2 µL (T6), 4 µL (T12), and 6 µL (T18) of citronella essential oil, respectively. A negative control (Cneg) without oil was also included. The Petri dishes were incubated under constant illumination at 25 °C for 8 Days. The radial growth of each colony was measured using a digital caliper (Traceable®, Control Co., USA), and results were expressed as mycelial diameter. Each treatment was replicated four times, and the experiment was repeated twice.

For testing the films, Petri dishes containing PDA were inoculated with 8 mm fungal discs. Circular films (10 cm in diameter, containing 7.5, 10, or 12.5% citronella essential oil) were affixed to the inner surfaces of the dish lids, ensuring no direct contact with the fungal mycelium. Treatments included a negative control dish without any film (Cneg). As with the citronella essential oil assay, the Petri dishes were incubated at 25 °C for 8 Days, and the mycelial diameter was measured using a digital caliper (Traceable®, Control Co., USA). Each treatment was evaluated in four replicates, and the experiment was conducted twice to ensure reproducibility.

2.5. Action Mechanism of Films

2.5.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

SEM observations were applied only for the mycelium of A. alternata and E. nigrum exposed to films with 10% essential oil and C. herbarum exposed to films added with 7.5% essential oil. After 8 Days of incubation, the mycelia were fixed in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 48 h at 4 °C. After several washings with double-distilled water, the samples were successively dehydrated with different ethanol solutions (30%, 50%, 70%, 85%, and 96%) for 30 min each. Finally, the samples were dried with CO2 (as per the equipment’s data), coated with gold (as per the equipment’s data), and examined using a SEM (JEOL JSM-IT300 microscope, Japan).

2.5.2. Fatty Acid Profile

The fatty acid composition of fungal mycelium was determined by gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) after converting the lipid fraction into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs). Before chemical derivatization, the freeze-dried mycelial material was milled to obtain a uniform analytical sample. Transesterification was performed following the methodology described by Sönnichsen and Müller [

14]. Chromatographic measurements were conducted on an Agilent 7890A GC system fitted with a flame ionization detector, a split/splitless injection port, and an automated sample system. The chromatographic separation of FAMEs was performed using an Agilent J&W DB-FastFAME capillary column (60 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness), with helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Samples (1 μL) were injected in split mode with a 15:1 split ratio. The oven program consisted of an initial hold at 80 °C for 1.5 min, followed by heating at 45 °C min⁻¹ to 205 °C with an 11-min isothermal step, and a subsequent increase of 12 °C min⁻¹ to 235 °C with a 10-min hold. The injector was maintained at 260 °C, and the FID was operated at the same temperature with hydrogen and air supplied at 40 and 400 mL/min, respectively. Fatty acids were identified by matching their retention times to those of a certified reference mixture of methyl esters (Supelco 37-component standard) analyzed under identical experimental conditions.

2.5.3. Conductivity and Absorbance at 260 nm.

After 8 Days of incubation, Cneg mycelia and active film treatments of each phytopathogen were washed with 10 mL of sterile distilled water (for conductivity measurement) or 10 mL of 0.1 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) (for absorbance measurement). The mycelia were transferred to a Falcon tube, and finally, 10 mL of the respective liquid (distilled water or PBS) was added. The supernatants were collected after centrifugation. For extracellular conductivity measurements, a pH meter (Mettler Toledo, S500 SevenExcellenceTM pH/ion, Indonesia) was used, and results were expressed as µS/cm with 2 replicates per treatment. For absorbance measurement at 260 nm, a UV/VIS spectrophotometer (VE-5100UV, Cientifica Vela Quin, Mexico City, Mexico) was used, and the optical density (OD260) was determined. Each treatment was evaluated twice, and the assay was repeated twice to verify the results

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent determinations. Data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA, and the significance of their variance was verified by means of the Tukey test (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Films Fabrication and Characterization

3.1.1. Film Fabrication

After processing using the casting method, films were obtained with citronellal concentrations of 16.58 mg/g (7.5% citronella essential oil), 19.04 mg/g (10% citronella essential oil), and 21.50 mg/g (12.5% citronella essential oil). Citronellal was quantified as the main component of the films and is believed to be responsible for their primary antifungal activity.

3.1.2. WVTR

The WVTR. PLA films containing citronella essential oil at 7.5, 10, and 12.5% (w/w), produced by the solvent casting method, exhibited WVTR values ranging from 43.75±2.25 to 46.48±5.48 g/m²·Day, with no significant differences (p > 0.05) compared to the control (42.41±1.86 g/m²·Day). This indicates that, under the casting conditions, the incorporation of citronella essential oil did not substantially alter the WVTR of PLA. Essential oils PLA films can increase the number or size of cavities, act as plasticizers, or create interactions between chain segments. According to our results, the type and concentration of essential oil did not alter the structure of PLA. The addition of essential oils to PLA films does not follow a predictable trend in terms of their effect on WVTR, as illustrated by published data. For example, PLA films containing 2.5%

Ocimum basilicum essential oil in combination with 5% or 10% neem essential oil (

Azadirachta indica) exhibited no significant modification in WVTR [

15,

16]. In contrast, the addition of

Ocimum gratissimum essential oil at concentrations of 2.5% and 5% produces an increase in WVTR [

15]. On the other hand, PLA films containing 5% ginger essential oil, 1% curcumin essential oil, or 5%

O. basilicum essential oil showed reduced WVTR, suggesting enhanced barrier properties [

15,

17]. Our findings highlight the complexity of essential oil–PLA interactions and the influence of processing conditions and PLA matrix compatibility.

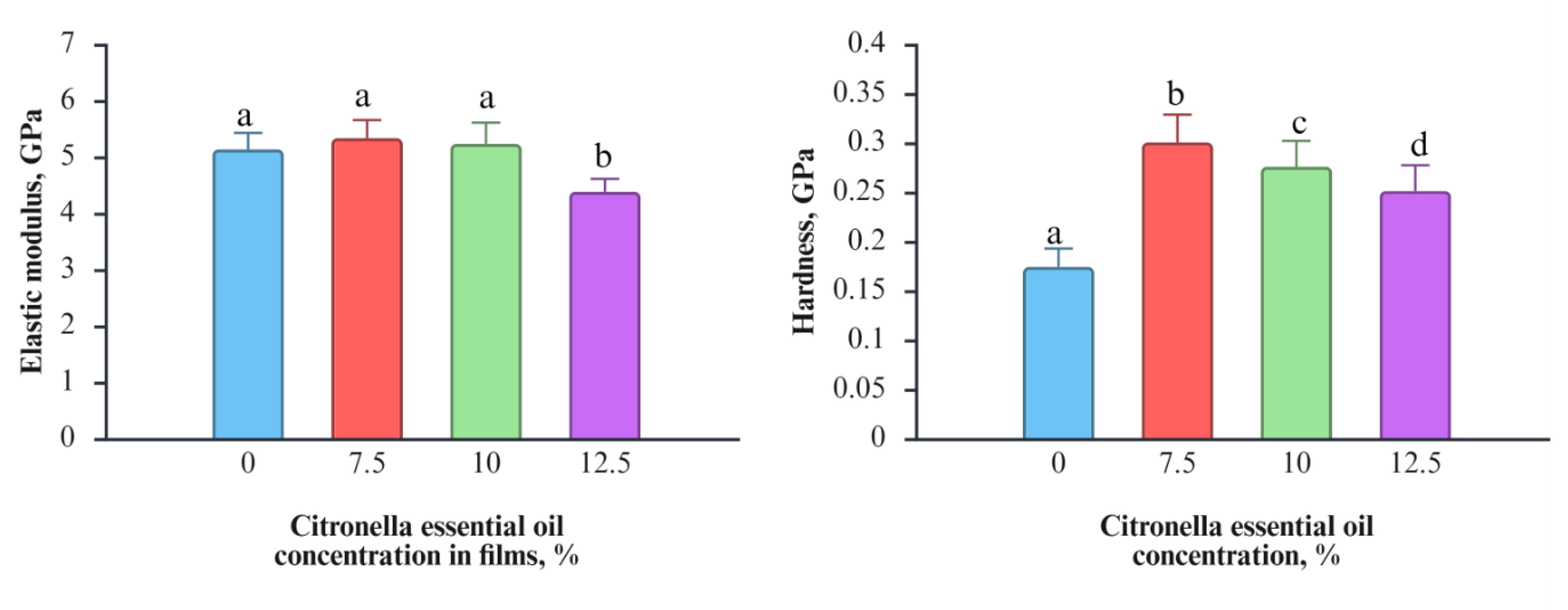

3.1.3. Depth-Sensing Indentation

Figure 1 shows the values of nanoindentation modulus and hardness as a function of citronella essential oil concentration (0, 7.5, 10, and 12.5%) in PLA films. The mechanical properties of a material, such as PLA, help determine whether it will effectively protect the food. The elastic modulus did not change with the addition of 7.5% and 10% of citronella essential oil. The only change detected was at 12.5%, where the elastic modulus was statistically lower than that of the control. The decrease in elastic modulus in PLA films agrees with the results of PLA films added with 15% of D-limonene or polylactide-poly (ethylene glycol) films added with 5% of olive leaf extracts [

18,

19]. In terms of hardness, this parameter increased proportionally with the addition of citronella essential oil up to 12.5%, after which it decreased but remained higher than that of the neat PLA films. A similar decrease in hardness was observed on polylactide-poly (ethylene glycol) films added with 5% of olive leaf extracts [

19].

Figure 2.

Elastic modulus and hardness of PLA films incorporated with different concentrations of citronella essential oil (0, 7.5, 10, and 12.5%). Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among citronella essential oil concentrations for each mechanical parameter (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Elastic modulus and hardness of PLA films incorporated with different concentrations of citronella essential oil (0, 7.5, 10, and 12.5%). Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among citronella essential oil concentrations for each mechanical parameter (p < 0.05).

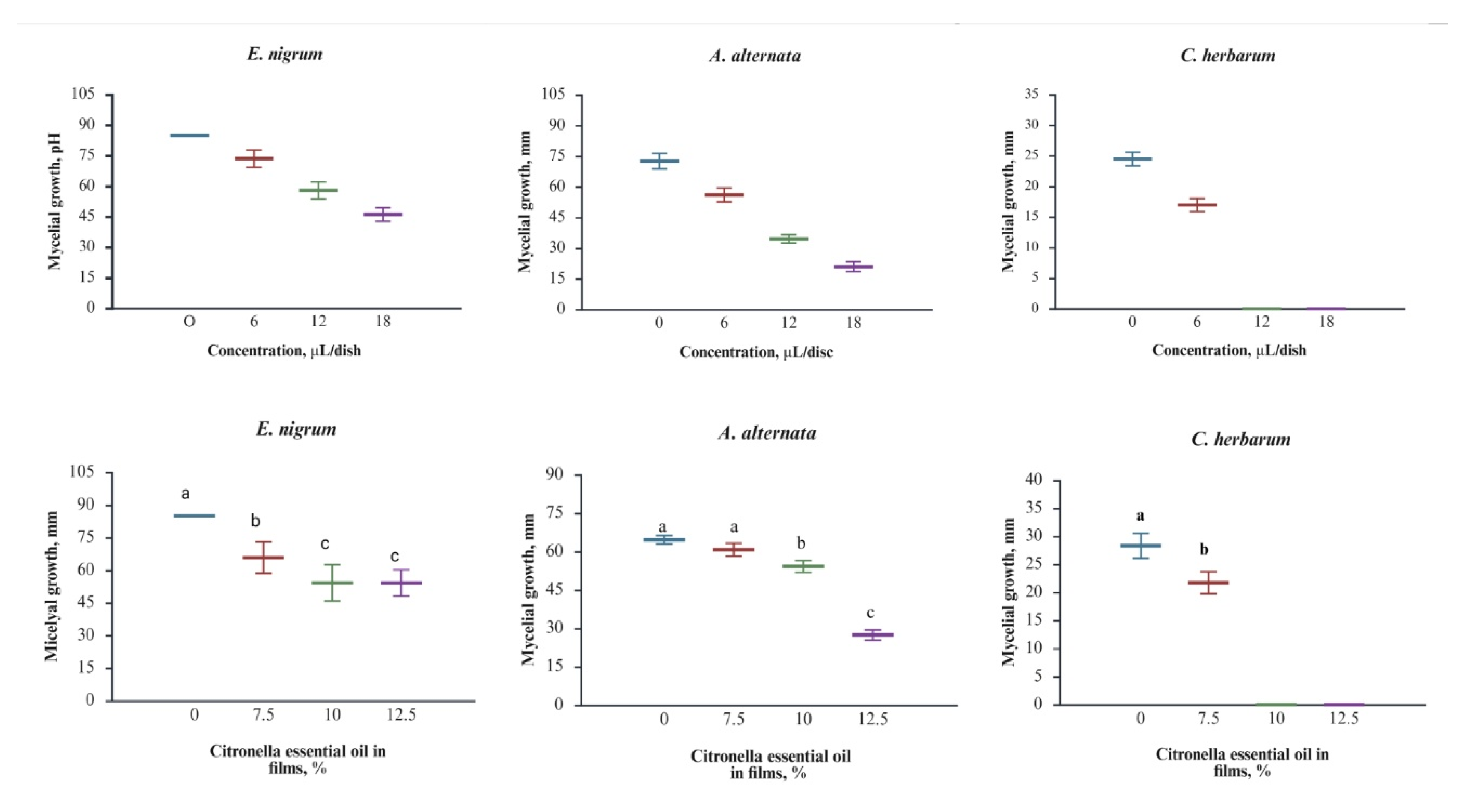

3.2. In Vitro Antifungal Effect of Citronella Essential Oil and Active Films

Figure 2 (top) shows the antifungal activity of citronella essential oil applied to the mycelium growth against the phytopathogens tested. For

E. nigrum (r=-0.9778, correlation coefficient), the control displayed the most remarkable mycelial growth, while significant reductions occurred at 6 μL/disc, with further decreases at 12 and 18 μL/disc. The growth was not completely suppressed; however, inhibition was substantial at each concentration, confirming the strong inhibitory effect of citronella essential oil. A similar trend was observed for

A. alternata (r = -0.9870, correlation coefficient), where control mycelium initially measured 72.56 ± 3.78 mm in size; the size progressively decreased to 56.06 ± 3.38 mm at 6 μL/disc, 34.51 ± 2.02 mm at 12 μL/disc, and 20.93 ± 2.39 mm at 18 μL/disc.

A. alternata showed significant growth reduction at all concentrations. The highest sensitivity was observed in

C. herbarum (r =- 0.9490), with growth decreasing from 24.45 ± 1.12 mm in the control to 16.94 ± 1.08 mm at 6 μL/disc and complete inhibition at 12 and 18 μL/disc. In agreement with our results, the order of susceptibility to citronella essential oil can be as

C. herbarum >

A. alternata >

E. nigrum. The variation in fungal responses to citronella essential oil may be influenced by the chemical composition and structural organization of fungal cell membranes, which provide molecular targets for interactions with the predominant functional groups of citronella essential oil compounds. Our results are consistent with those reported by other authors who used citronella essential oil to control the same phytopathogen in different fruit crops. For example,

A. alternata isolated from cherry tomatoes and Dancy tangerine, and

E. nigrum isolated from bamboo, were controlled with citronella essential oil [

20,

21,

22]. No data were found on the in vitro control of these phytopathogenic blueberry isolates using citronella essential oil.

Figure 2 (bottom) shows that adding citronella essential oil to PLA films essentially maintains its antifungal activity. In the case of

E. nigrum (r =- 0.9044), growth was significantly reduced even at the lowest concentration tested (7.5%). Additional inhibition was observed at 10% and 12.5%, confirming that the films’ response depends on oil concentration, as seen in the direct oil application test. For

A. alternata (r =- 0.7383), mycelial growth decreased progressively with increasing oil content, with the greatest inhibition observed at 12.5%. In this fungus, a dose-response relationship is observed that is like that of direct citronella essential oil assays. The most significant effect was again observed against

C. herbarum (r = -0.8700). Although the correlation coefficient was not the highest among the three fungi, the films containing 7.5% citronella essential oil significantly inhibited growth, with complete inhibition at 10% and 12.5%, consistent with the complete inhibition observed at 12 μL/disc in the direct application test. To date, two publications have demonstrated the antifungal effect of citronella essential oil films. In these publications, the target fungi were

Aspergillus niger, and the polymer bases were PLA and polyhydroxyalkanoates [

23,

24]. In the case of blueberries, there is no report of the use of antifungal active films based on citronella essential oil to control phytopathogens associated with fruit rots on postharvest.

Overall, the fungus’s susceptibility to citronella essential oil can be ranked as C. herbarum > A. alternata > E. nigrum for both directly applied essential oil and films, corroborating the conclusion that citronella essential oil retains its bioactivity within the PLA matrix. According to these results, citronella oil is a promising natural product for controlling rot in blueberries, either through direct contact or as an active compound in active food packaging.

3.3. Action Mechanism of Films

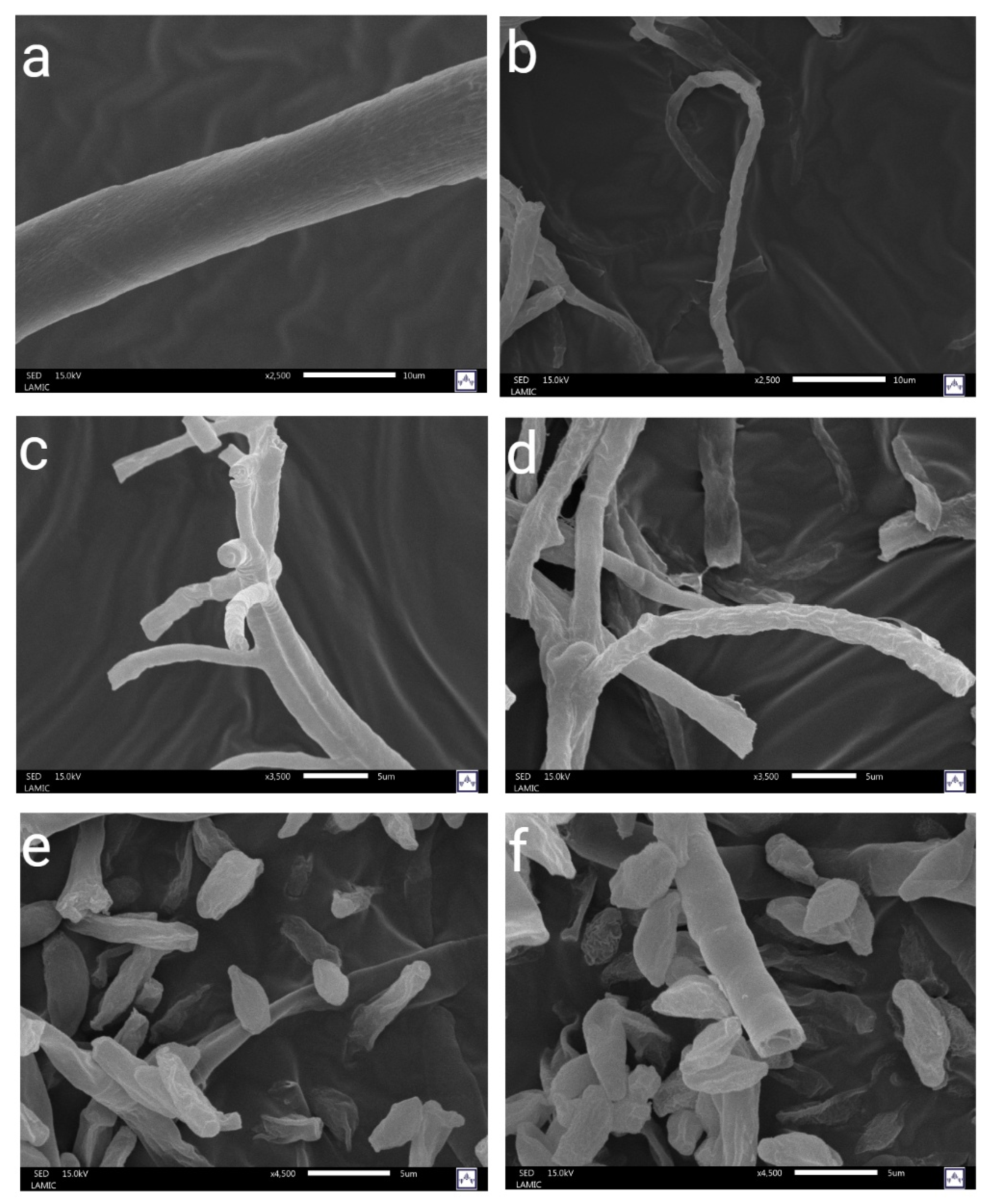

3.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

Figure 3 shows the SEM images of

E. nigrum (a–b),

A. alternata (c–d), and

C. herbarum (e–f). The pictures on the left show untreated fungal mycelia, while those on the right show mycelia exposed to the antifungal active films. In general, the mycelia of untreated fungi exhibited intact hyphal structures with morphologies characteristic of each species tested. On the other hand, the mycelia exposed to the antifungal active films showed morphological alterations. In

A. alternata, the treated hyphae exhibited structural alterations, including surface roughness, folding, collapse, and distortion. For

E. nigrum, the hyphae exhibited thinner structures, irregular surfaces, and, in some cases, folding or fragmentation, indicating a loss of structural rigidity. In

C. herbarum, no morphological changes were observed, as shown in the images. Our results agree with those reported in the literature, suggesting that essential oils can induce significant morphological alterations in fungal hyphae [

25]. In our study, these changes were particularly evident in

A. alternata and

E. nigrum, where the citronella essential oil released from the active films produced apparent modifications in the hyphal structure. These results align with research on

A. alternata isolated from cherry tomatoes, which found that exposure to 0.8 μL/mL of citronella essential oil resulted in a complete absence of conidia, along with flattened and shriveled hyphae, hyphal swelling, and roughened cell walls [

20].

In contrast, information about Epicoccum is limited. Few studies have focused on the use of chemicals or pesticides to combat diseases caused by Epicoccum species. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the effectiveness of citronella essential oil for controlling these species [

26].

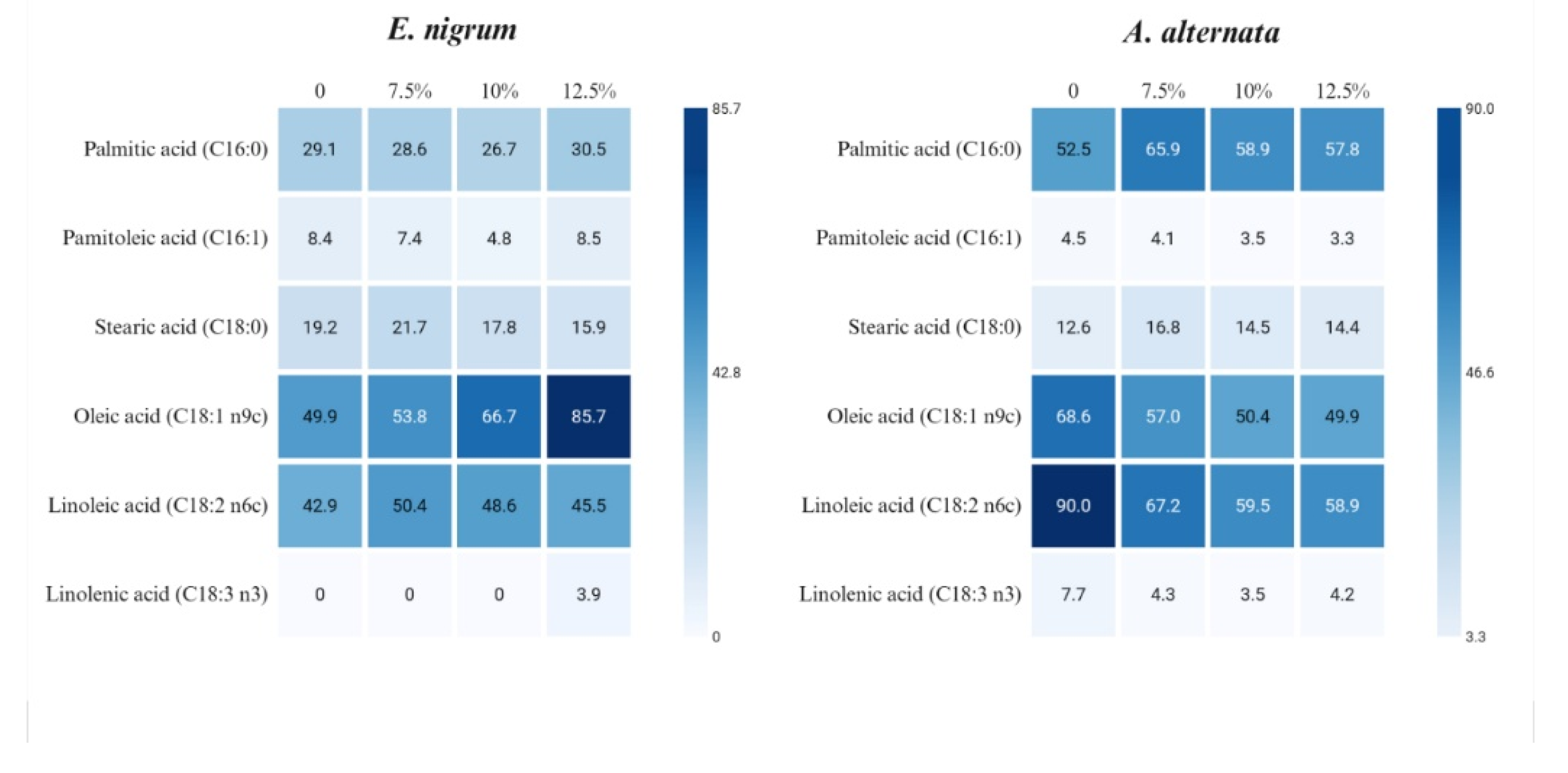

3.3.2. Fatty Acid Profile

Figure 4 shows the changes in fatty acid profiles in the mycelium exposed to active films, highlighting species-specific variations. For instance,

E. nigrum mycelium comprises palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, and linoleic acid. For example,

A. alternata contains not only these fatty acids but also linolenic acid. In both species, the unsaturated fatty acids, oleic and linoleic, predominate. Regarding

E. nigrum, we can observe the following. Oleic acid increases strongly with citronella essential oil concentration, and linolenic acid appears only at the highest citronella essential oil level. Palmitic acid shows modest fluctuations, and palmitoleic acid decreases at 10% citronella essential oil but rebounds at 12.5%. Stearic acid increases at 7.5% citronella essential oil and then declines. Linoleic acid rises at 7.5% citronella essential oil, but then trends downward. Additionally, with respect to

A. alternata, the following observations are noted. Palmitic acid concentration increases with exposure to citronella essential oil, while oleic acid decreases progressively. Linoleic acid and linolenic acid show a marked decline under exposure to citronella essential oil. Stearic acid increases at 7.5% citronella essential oil but remains relatively stable afterward.

According to Turk et al. [

27], unsaturated fatty acids contribute to cell membrane integrity, which means the ability of cells to respond to various environmental stresses, such as exposure to citronella essential oil. The type and quantity of unsaturated fatty acids in the membrane are significant determinants of membrane integrity and permeability in fungi, affecting both membrane homeostasis and pathogenicity. Higher proportions of UFAs increase membrane fluidity, affecting the rotation and movement of functional proteins [

28]. Then, in the case of

E. nigrum, oleic and linoleic acids increase in response to higher concentrations of citronella oil, suggesting a mechanism to maintain membrane fluidity. In the case of

A. alternata, both acids decrease, so we can hypothesize that the action of citronella essential oil destroys them.

3.3.3. Conductivity and Absorbance at 260 nm.

Table 1 presents the absorbance at 260 nm and the mycelial conductivity of phytopathogens treated with active films. These variables are associated with changes at the membrane level, specifically regarding the disruption of the fungal cellular membrane. In the case of

C. herbarum, neither variable indicated any potential damage to the cellular membrane. Although mycelial growth was reduced, this did not elucidate the mechanism of action of the active films against the tested phytopathogen. In

A. alternata, membrane changes were observed only at 10% and 12.5% citronella essential oil concentrations. While in

E. nigrum, changes in absorbance indicated membrane alterations beginning at a concentration of 7.5% citronella essential oil. Notably, the observed effects were not dependent on citronella essential oil concentration, unlike the reduction in mycelial growth observed at higher concentrations.

In general, the disruption of the cell membrane by the impact of citronella essential oil released from the films is consistent with the literature, indicating that citronella essential oil damages fungal membranes[

29]. It is important to note that evaluating the antifungal mechanism directly from the oil may yield more conclusive results. However, the tests we conducted involved the release of volatile compounds from citronella essential oil immersed in the PLA matrix into the mycelium of the tested fungi. The interaction is considered a part of the relationship between the packaging and the fruit.

4. Conclusions

Antifungal active films demonstrated effective in vitro antifungal activity against key phytopathogens associated with blueberry postharvest decay. The essential oil preserved its bioactivity within the PLA matrix. The antifungal mechanisms of action revealed that the antifungal effect is primarily associated with membrane disruption, as evidenced by hyphal deformation, changes in fatty acid composition, and leakage of intracellular components, although the response varied across species. Clearly, C. herbarum showed high sensitivity, whereas E. nigrum and A. alternata exhibited distinct adaptive or damage patterns. These findings highlight the potential of the antifungal active films developed as a sustainable and natural alternative to synthetic fungicides for food packaging. Antifungal active films can help reduce postharvest losses and improve the shelf life of blueberries.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, José Juan Virgen-Ortiz.; Abel Hurtado-Macías., and Citlali Colín-Chávez.; methodology, Elizabeth Peralta., Roberto Pablo Talamantes-Soto., Orlando Hernánadez-Cristobal., and Sandra Denisse Zavala-Aranda.; formal analysis, Miguel Ángel Martínez-Téllez.; writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, Citlali Colín Chávez. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Instituto de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación del Gobierno de Michoacán for the support of the project ICTI-PICIR23–130.”.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Karanth, S.; et al. Linking microbial contamination to food spoilage and food waste: the role of smart packaging, spoilage risk assessments, and date labeling. In Frontiers in Microbiology; 2023; Volume 14- 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chaidech, P.; Matan, N. Cardamom oil-infused paper box: Enhancing rambutan fruit post-harvest disease control with reusable packaging. LWT 2023, 189, 115539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luesuwan, S.; et al. Effect of Active Packaging Material Fortified with Clove Essential Oil on Fungal Growth and Post-Harvest Quality Changes in Table Grape during Cold Storage. Polymers 2021, 13(19), 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnida Raja Hashim, R.; et al. Fabrication of active food packaging based on PLA/Chitosan/CNC-containing Coleus aromaticus essential oil: application to Harumanis mango. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2023, 17(6), 6341–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Chávez, F.; et al. Control of mango decay using antifungal sachets containing of thyme oil/modified starch/agave fructans microcapsules. Future Foods 2021. 3, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; et al. Blueberries, in Antioxidants in Fruits: Properties and Health Benefits; Nayik, G.A., Gull, A., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 593–614. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.R.; et al. Main diseases in postharvest blueberries, conventional and eco-friendly control methods: A review. LWT 2021, 149, 112046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Arancibia, F.; et al. Biopolymers as Sustainable and Active Packaging Materials: Fundamentals and Mechanisms of Antifungal Activities. Biomolecules 2024, 14(10), 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejene, B.K.; Gudayu, A.D. Eco-Friendly Packaging Innovations: Integrating Natural Fibers and ZnO Nanofillers in Polylactic Acid (PLA) Based Green Composites - A Review. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Materials 2024, 63(12), 1645–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.K.; Gaikwad, K.K. Natural antimicrobial and antioxidant compounds for active food packaging applications. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 14(4), 4419–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; et al. Chemical Composition and Antifungal Potential of Citronella (Cymbopogon nardus) Leaves Essential Oil and its Major Compounds. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2021, 24(3), 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, I.N.; et al. The relation between load and penetration in the axisymmetric boussinesq problem for a punch of arbitrary profile. International Journal of Engineering Science 1965, 3(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. Journal of materials research 1992, 7(6), 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönnichsen, M.; Müller, B.W. A rapid and quantitative method for total fatty acid analysis of fungi and other biological samples. Lipids 1999, 34(12), 1347–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakar, P.R.; et al. Insecticidal property of Ocimum essential oil embedded polylactic acid packaging films for control of Sitophilus oryzae and Callosobruchus chinensis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 256, 128298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbuvel, M.; Kavan, P. Development and investigation of antibacterial and antioxidant characteristics of poly lactic acid films blended with neem oil and curcumin. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2022, 139(14), p. 51891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Panneerselvam, K. Development of polylactic acid based functional films reinforced with ginger essential oil and curcumin for food packaging applications. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2022, 16(6), 4703–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; et al. Ternary PLA–PHB–Limonene blends intended for biodegradable food packaging applications. European Polymer Journal 2014, 50, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabska-Zielińska, S.; et al. Active Polylactide-poly(ethylene glycol) Films Loaded with Olive Leaf Extract for Food Packaging—Antibacterial Activity, Surface, Thermal and Mechanical Evaluation. Polymers 2025, 17(2), 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; et al. Effect of citronella essential oil on the inhibition of postharvest Alternaria alternata in cherry tomato. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2014, 94(12), 2441–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcino, M.M.; et al. Essential oils in the management of Alternaria alternata f. sp. citri in ‘Dancy’ tangerine fruits. Revista Caatinga 2023, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.-k.; et al. Antifungal activity of 4 kinds of aromatic essential oil derived from plants to pathogenic fungi of bamboo. 2020.

- Septiyanti, M.; et al. Study of the antibacterial activity of citronella oil fractions on polylactic acid-based packaging. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2023; 2902. [Google Scholar]

- Rech, C.R.; et al. Antimicrobial and Physical–Mechanical Properties of Polyhydroxybutyrate Edible Films Containing Essential Oil Mixtures. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2021, 29(4), 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, C.W.T.; et al. Impact of Essential Oils Composition and Exposure Methods on Fungal Growth and Morphology: Insights for Postharvest Management. Future Postharvest and Food 2025. 2, 2, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balendres, M.A.; et al. Epicoccum, in Compendium of Phytopathogenic Microbes in Agro-Ecology: Vol.1 Fungi; Amaresan, N., Kumar, K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, M.; et al. Salt stress and plasma-membrane fluidity in selected extremophilic yeasts and yeast-like fungi. FEMS Yeast Research 2007, 7(4), 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Brassinolide alleviated chilling injury of banana fruit by regulating unsaturated fatty acids and phenolic compounds. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 297, 110922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; OuYang, Q.; Tao, N. Plasma membrane damage contributes to antifungal activity of citronellal against Penicillium digitatum. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2016, 53(10), 3853–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |