Submitted:

27 January 2026

Posted:

27 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

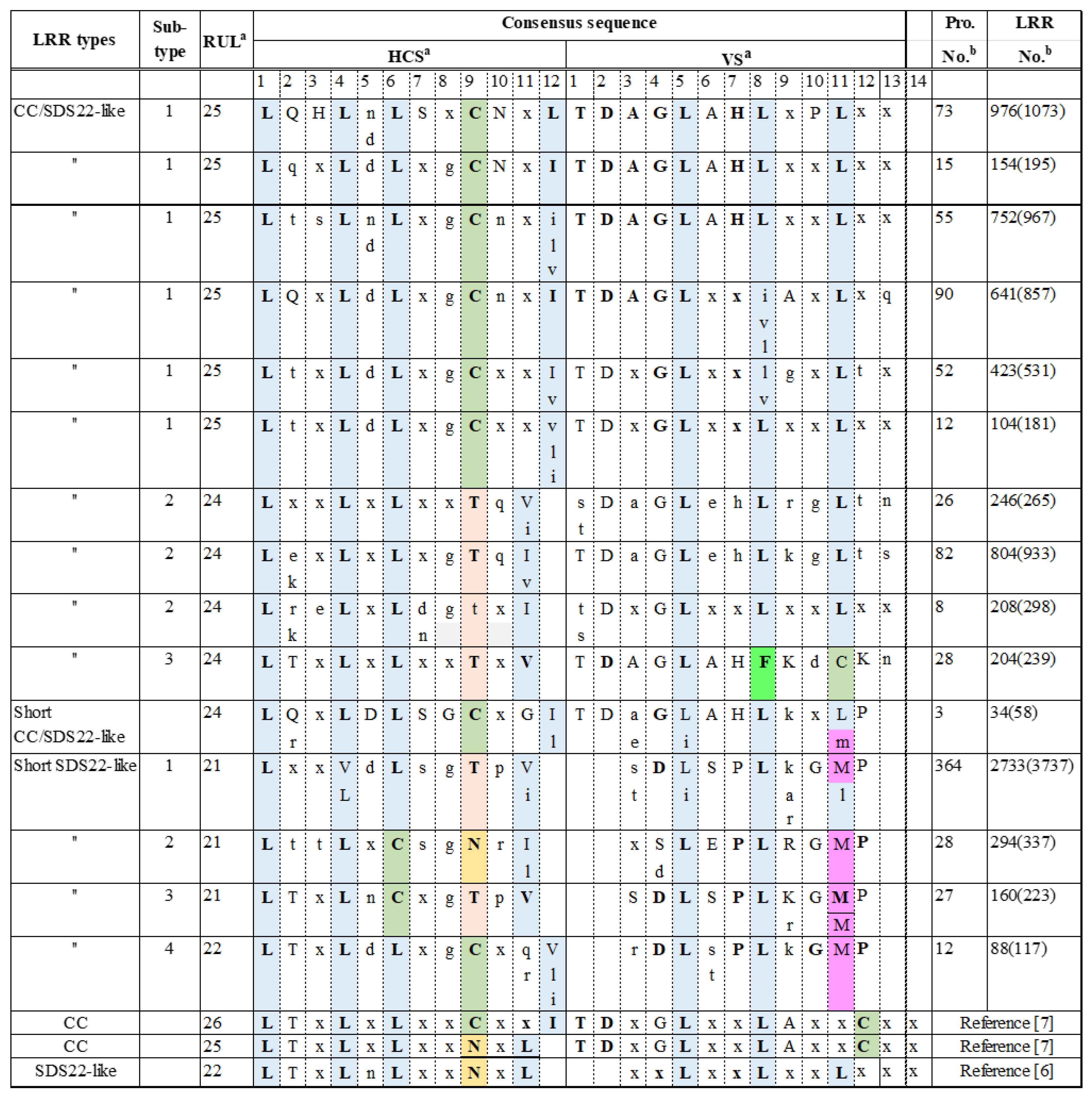

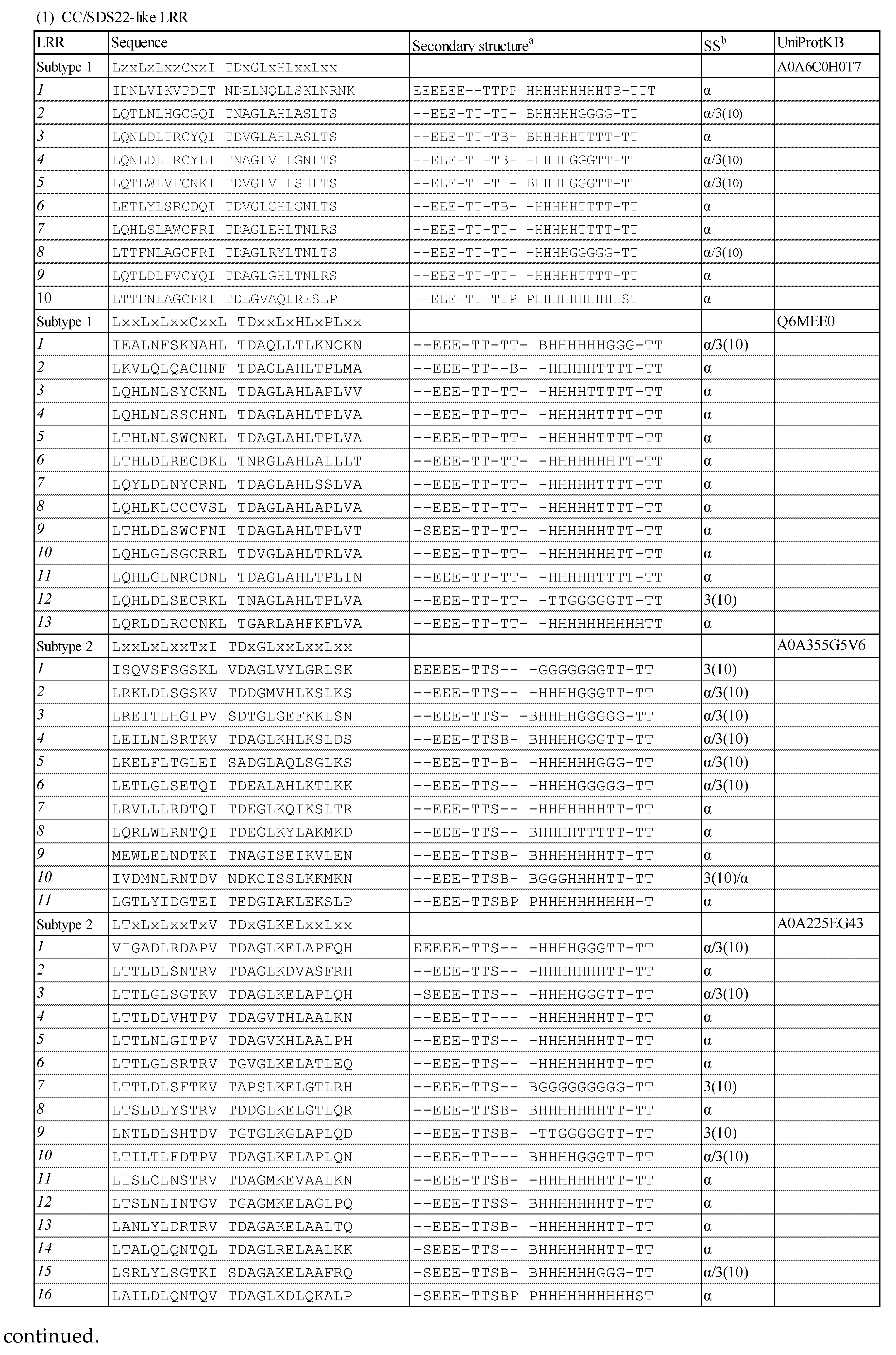

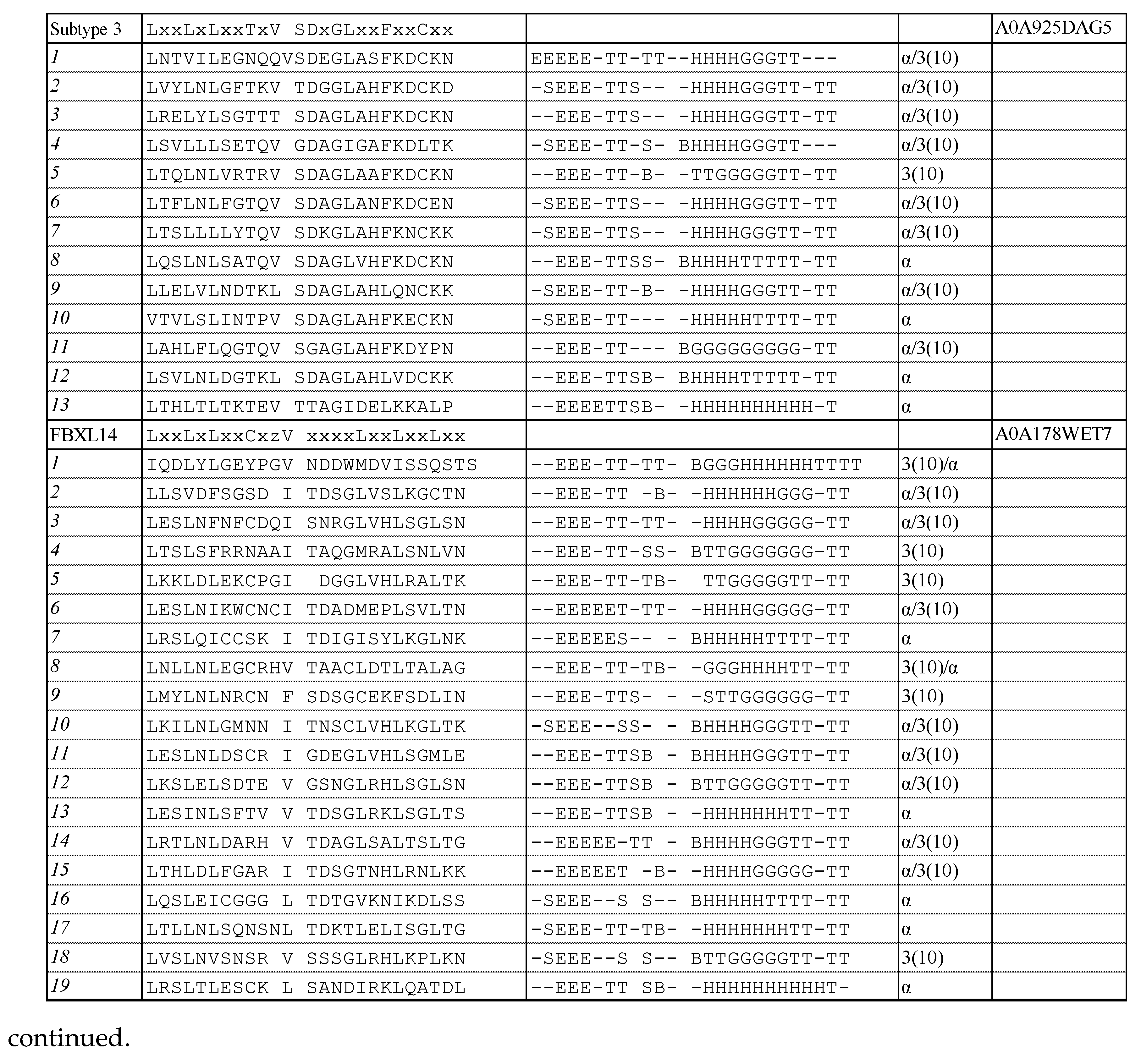

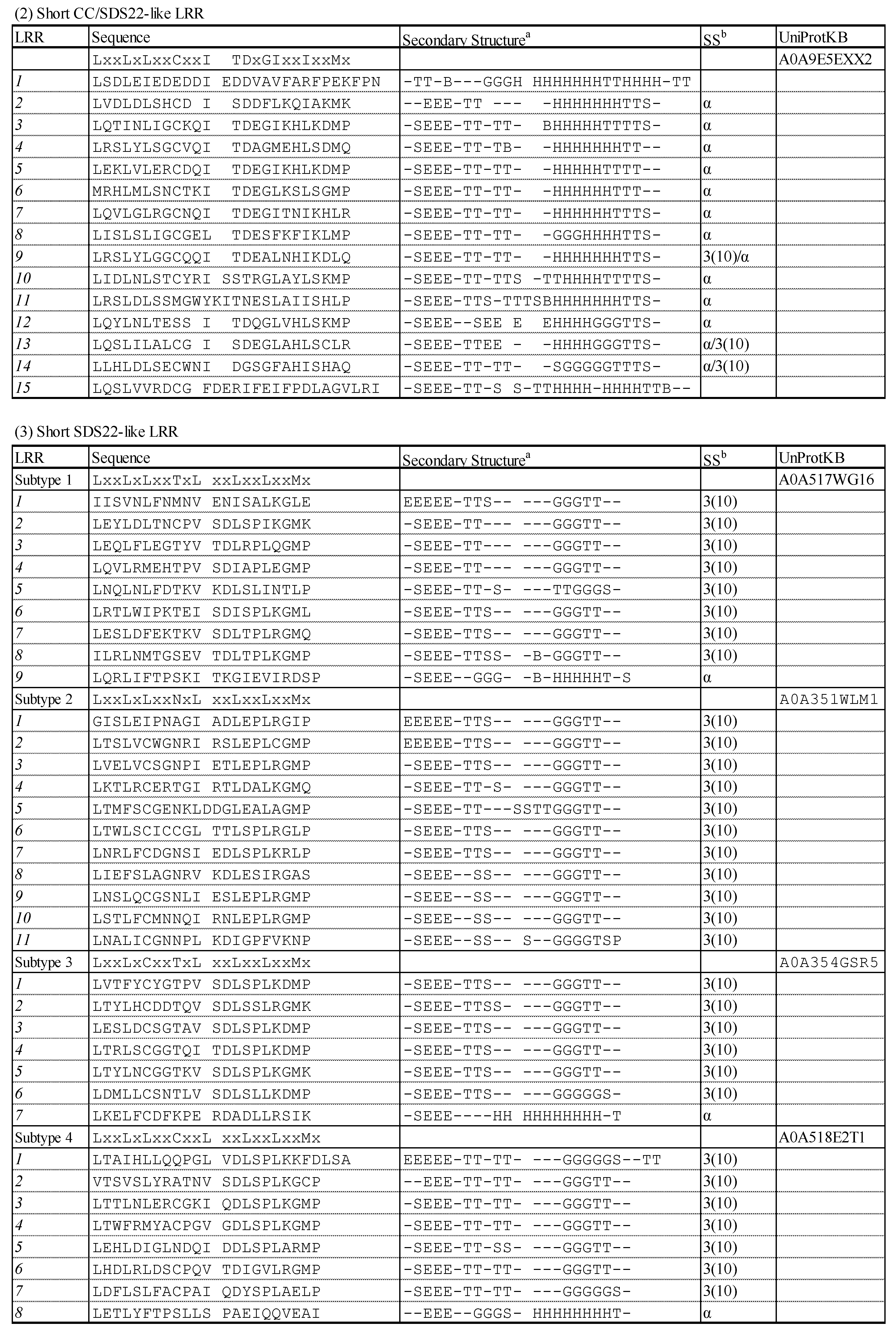

3.1. Consensus Sequences of the New Types of LRR

3.1.1. Three Subtypes of CC/SDS22-like LRR with HCS = 11 or 12 and VS = 13

3.1.2. F-box/LRR-Repeat Protein 14 (FBXL14)

3.1.3. Short CC SDS22-like LRR with HCS = 12 and VS = 12

3.1.4. Four Subtypes of Short SDS22-like LRR with HCS = 11 or 12 and VS = 10

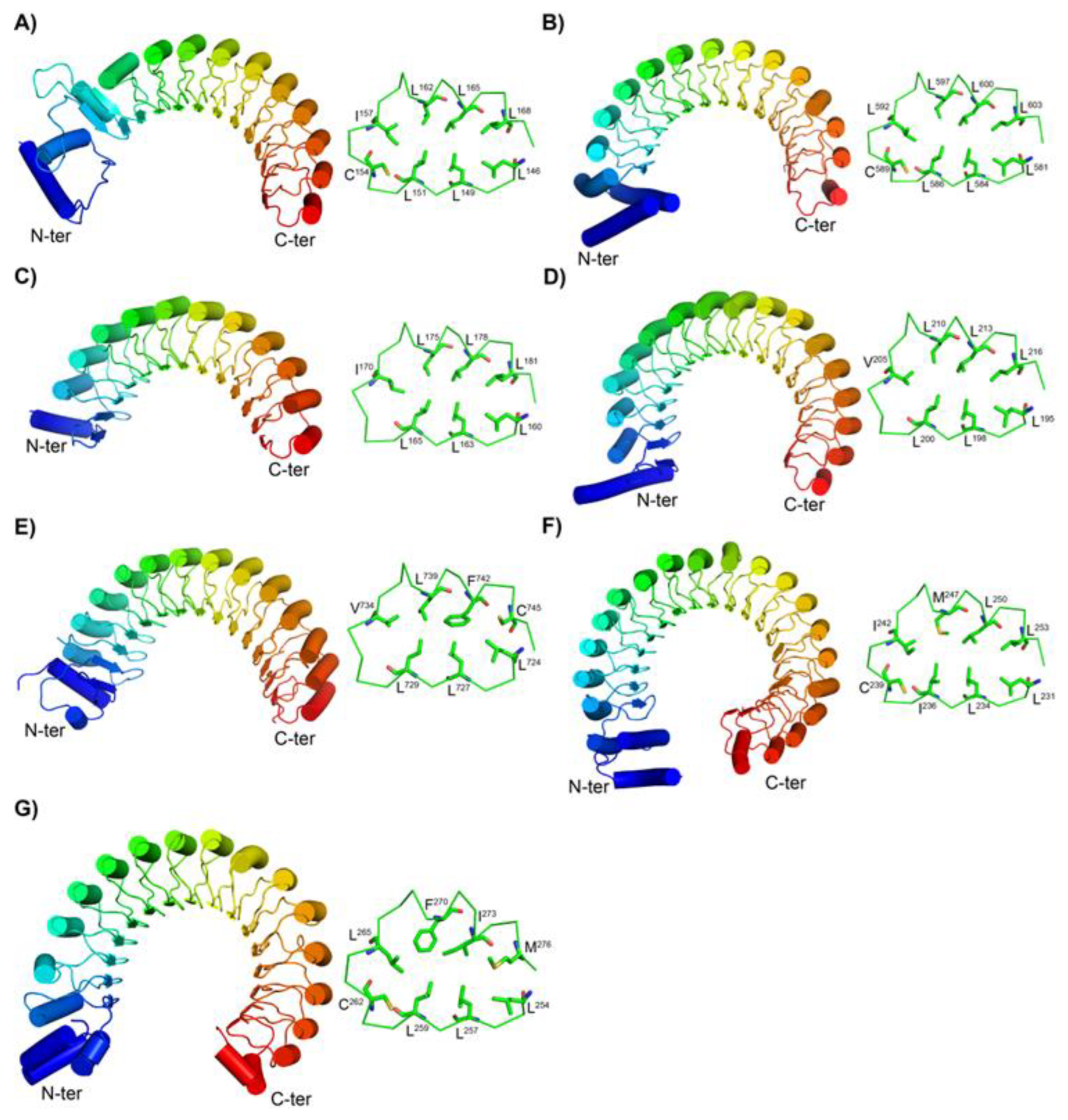

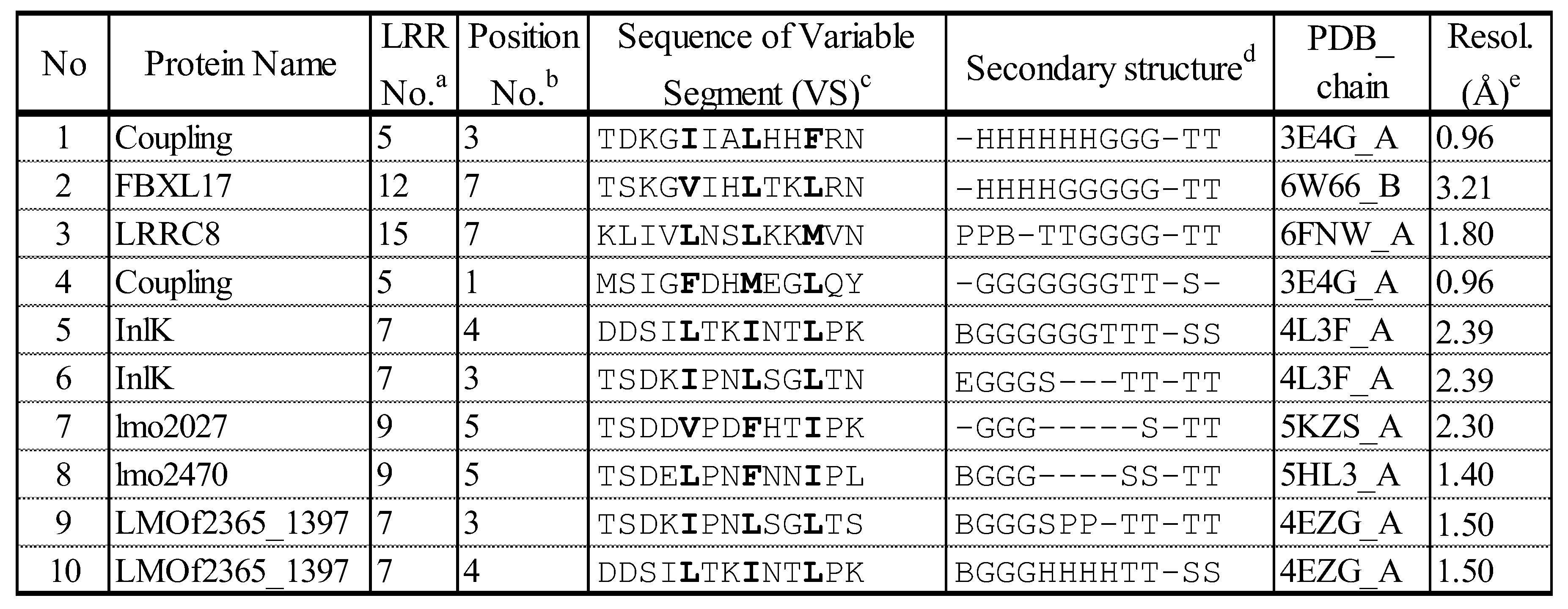

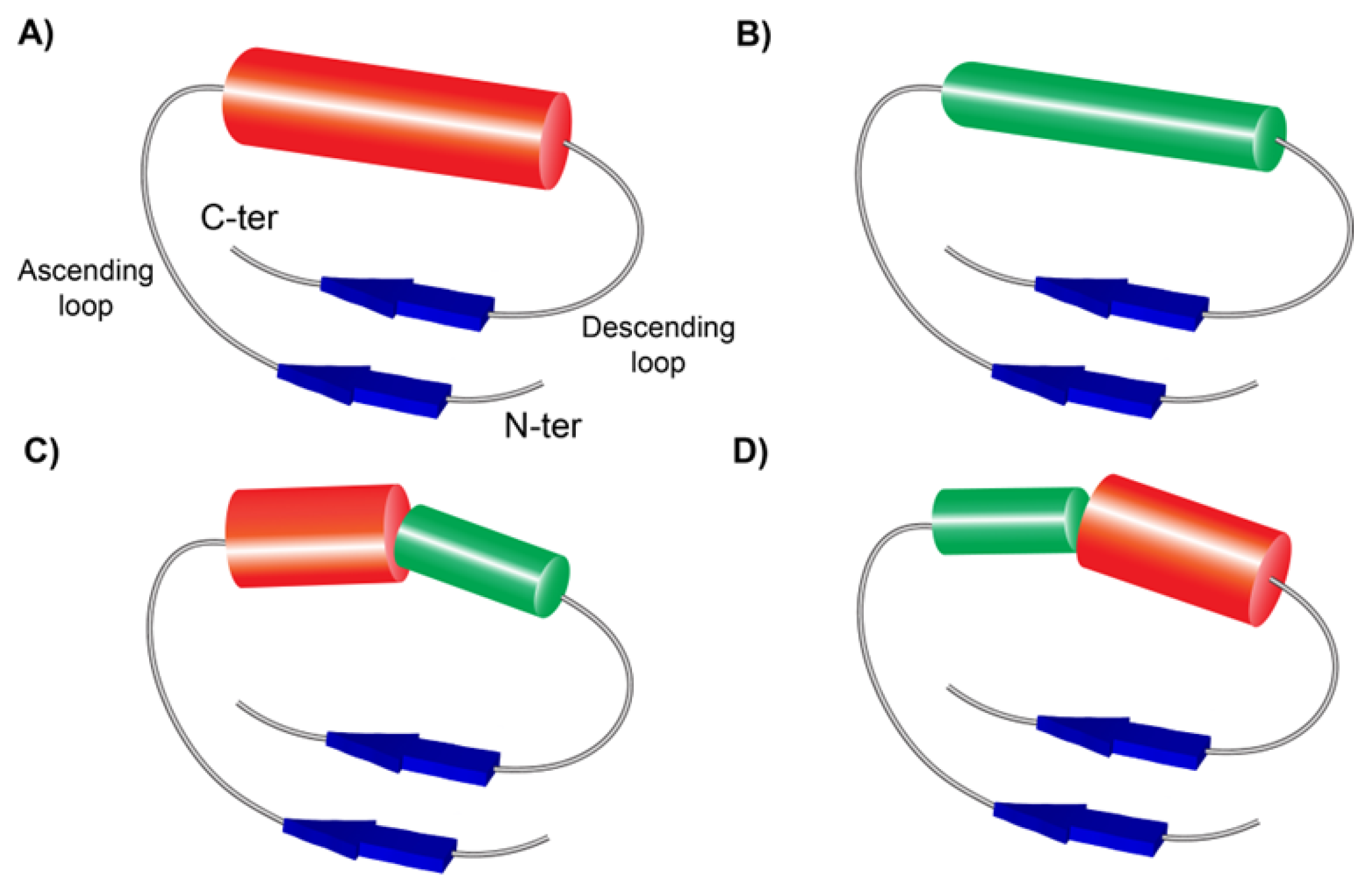

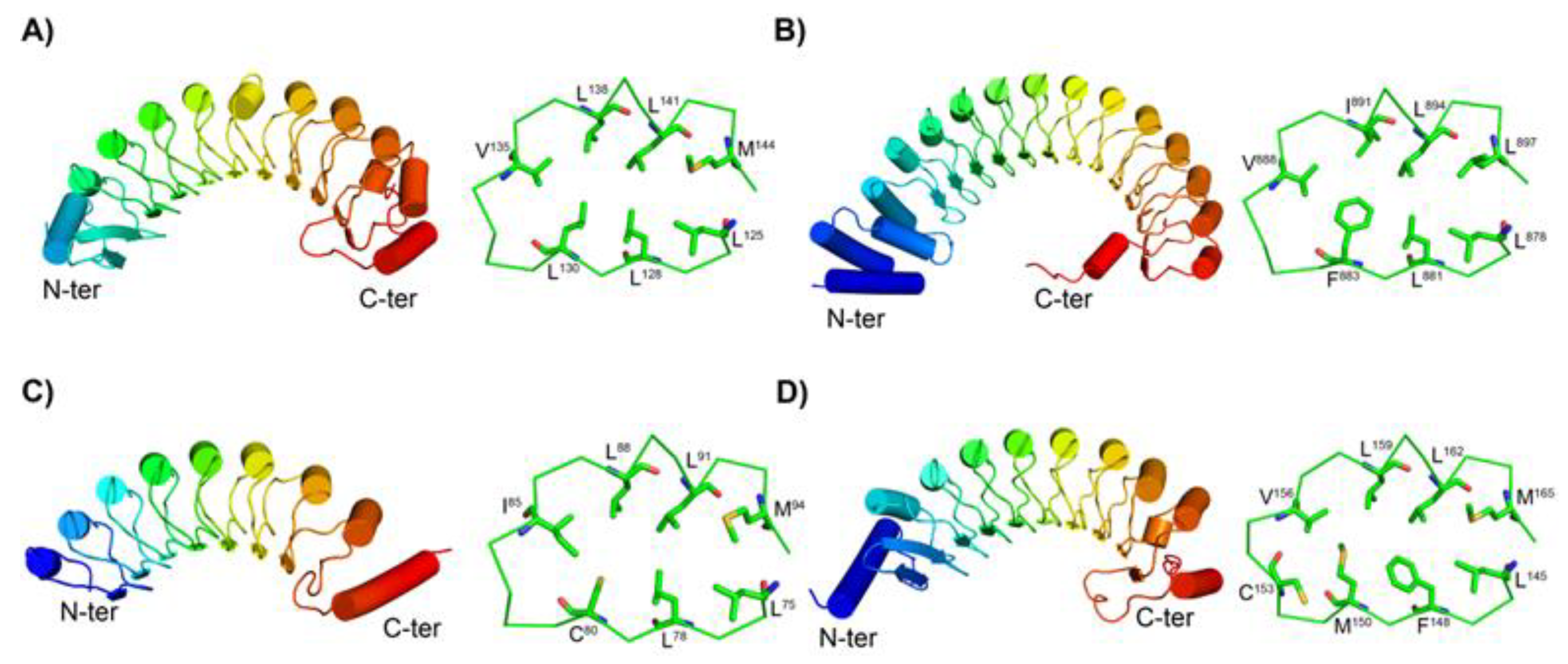

3.2. Structures of the New Types of LRR Motifs

3.2.1. Secondary Structures of CC/SDS22-Like and Short CC/SDS22-Like LRRs

3.2.2. Structures of short SDS22-like LRR

3.3. HELFIT Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. A novel SSS of β - 3(10) - β Motif in Short SDS22-like LRR

4.2. Simultaneous Occurrence of four SSSs in CC/SDS22-like LRR

4.3. Evolutionary Insights

4.4. Implications of Multiple Functions

4.5. The Bacterial PVC Superphylum

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LRR | Leucine-rich repeat |

| RUL | Repeating unit length of LRR |

| HCS | Highly conserved segment of LRR repeating unit |

| VS | Variable segment of LRR repeating unit |

| CC | Cyteine-containing |

| PS | Plant specific |

| SSS | Super-secondary structure |

| FBXL | F-box/LRR-repeat protein |

| PK | Protein kinase domain |

| LRR-RK | LRR receptor kinases |

| P | Helix pitch |

| R | Helix radius |

| N | Number of repeats per turn in helix |

| ∆z | Rise per repeat unit in helix |

| ∆φ | Rotation per repeat unit in helix |

References

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar]

- Kobe, B.; Deisenhofer, J. The leucine-rich repeat: A versatile binding motif. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1994, 19, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, J.; Hindle, K.L.; McEwan, P.A.; Lovell, S.C. The leucine-rich repeat structure. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 2307–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, N.; Kretsinger, R.H. Leucine Rich Repeats: Sequences, Structures, Ligand-Interactions, and Evolution; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- Batkhishig, D.; Bilguun, K.; Enkhbayar, P.; Miyashita, H.; Kretsinger, R.H.; Matsushima, N. Super secondary structure consisting of a polyproline II helix and a β-turn in leucine rich repeats in bacterial type III secretion system effectors. Protein J. 2018, 37, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batkhishig, D.; Enkhbayar, P.; Kretsinger, R.H.; Matsushima, N. A strong correlation between consensus sequences and unique super secondary structures in leucine rich repeats. Proteins 2020, 88, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batkhishig, D.; Enkhbayar, P.; Kretsinger, R.H.; Matsushima, N. A crucial residue in the hydrophobic core of the solenoid structure of leucine rich repeats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2021, 1869, 140631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobe, B.; Kajava, A.V. The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001, 11, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajava, A.V.; Anisimova, M.; Peeters, N. Origin and evolution of GALA-LRR, a new member of the CC-LRR subfamily: From plants to bacteria? PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1694. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima, N.; Miyashita, H.; Mikami, T.; Kuroki, Y. A nested leucine rich repeat (LRR) domain: The precursor of LRRs is a ten or eleven residue motif. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huyton, T.; Jaiswal, M.; Taxer, W.; Fischer, M.; Görlich, D. Crystal structures of FNIP/FGxxFN motif-containing leucine-rich repeat proteins. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, N.; Takatsuka, S.; Miyashita, H.; Kretsinger, R.H. Leucine rich repeat proteins: Sequences, mutations, structures and diseases. Protein Pept. Lett. 2019, 26, 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkhbayar, P.; Miyashita, H.; Kretsinger, R.H.; Matsushima, N. Helical parameters and correlations of tandem leucine rich repeats in proteins. J. Proteomics Bioinform. 2014, 7, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, J. Hydrogen bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1953, 39, 470–478. [Google Scholar]

- Enkhbayar, P.; Hikichi, K.; Osaki, M.; Kretsinger, R.H.; Matsushima, N. 3₁₀-helices in proteins are parahelices. Proteins 2006, 64, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, N.; Kretsinger, R.H. Numerous variants of leucine rich repeats in proteins from nucleo-cytoplasmic large DNA viruses. Gene 2022, 817, 146156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.A.; Majumdar, A.; Barrick, D. A second backbone: The contribution of a buried asparagine ladder to the global and local stability of a leucine-rich repeat protein. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 3480–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnev, V.R.; Kulikova, L.I.; Nikolsky, K.S.; Malsagova, K.A.; Kopylov, A.T.; Kaysheva, A.L. Current approaches in supersecondary structures investigation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Super secondary structure. Ditki (Smart Biology). Available online: (accessed 24 January 2026).

- Pal, L.; Dasgupta, B.; Chakrabarti, P. 3₁₀-helix adjoining alpha-helix and beta-strand: Sequence and structural features and their conservation. Biopolymers 2005, 78, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima, N.; Batkhishig, D.; Enkhbayar, P.; Kretsinger, R.H. A dual leucine-rich repeat in proteins from the eukaryotic SAR group. Protein Pept. Lett. 2023, 30, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, F.; Roux, S.; Paez-Espino, D.; Jungbluth, S.; Walsh, D.A.; Denef, V.J.; McMahon, K.D.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A.; Kyrpides, N.C. Giant virus diversity and host interactions through global metagenomics. Nature 2020, 578, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, N.; Miyashita, H.; Mikami, T.; Kuroki, Y. A new method for the identification of leucine-rich repeats by incorporating protein second structure prediction . In Bioinformatics: Genome Bioinformatics and Computational Biology; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Belogrudov, G.I.; Stroud, R.M. Crystal structure of bovine mitochondrial factor B at 0.96-Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13379–13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, E.L.; Jevtić, P.; Greber, B.J.; Gee, C.L.; Lew, B.G.; Akopian, D.; Nogales, E.; Kuriyan, J.; Rape, M. Structural basis for dimerization quality control. Nature 2020, 586, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneka, D.; Sawicka, M.; Lam, A.K.; Paulino, C.; Dutzler, R. Structure of a volume-regulated anion channel of the LRRC8 family. Nature 2018, 558, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, D.; Job, V.; Dortet, L.; Cossart, P.; Dessen, A. Structure of internalin InlK from the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 4520–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faralla, C.; Bastounis, E.E.; Ortega, F.E.; Light, S.H.; Rizzuto, G.; Gao, L.; Marciano, D.K.; Nocadello, S.; Anderson, W.F.; Robbins, J.R. Listeria monocytogenes InlP interacts with afadin and facilitates basement membrane crossing. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Bertoni, D.; Magana, P.; Paramval, U.; Pidruchna, I.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Tsenkov, M.; Nair, S.; Mirdita, M.; Yeo, J.; et al. AlphaFold protein structure database in 2024: Providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D368–D375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chebrek, R.; Leonard, S.; de Brevern, A.G.; Gelly, J.-C. PolyprOnline: Polyproline helix II and secondary structure assignment database. Database 2014, bau102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, E.G.; Thornton, J.M. PROMOTIF - a program to identify and analyze structural motifs in proteins. Protein Sci. 1996, 5, 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W.; Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 1983, 22, 2577–2637. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horn, M.; Collingro, A.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Beier, C.L.; Purkhold, U.; Fartmann, B.; Brandt, P.; Nyakatura, G.J.; Droege, M.; Frishman, D.; et al. Illuminating the evolutionary history of chlamydiae. Science 2004, 304, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domman, D.; Collingro, A.; Lagkouvardos, I.; Gehre, L.; Weinmaier, T.; Rattei, T.; Subtil, A.; Horn, M. Massive expansion of ubiquitination-related gene families within the Chlamydiae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 2890–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.; Kelker, M.S.; Wilson, I.A. Crystal structure of human Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) ectodomain. Science 2005, 309, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.L.; Bazan, J.F.; McDermott, G.; et al. Structure of the Nogo receptor ectodomain: A recognition module implicated in myelin inhibition. Neuron 2003, 38, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata, A.; Goto-Ito, S.; Sato, Y.; Shiroshima, T.; Maeda, A.; Watanabe, M.; Saitoh, T.; Maenaka, K.; Terada, T.; Yoshida, T.; et al. Structural insights into modulation and selectivity of transsynaptic neurexin–LRRTM interaction. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghozlane, A.; Joseph, A.P.; Bornot, A.; de Brevern, A.G. Analysis of protein chameleon sequence characteristics. Bioinformation 2009, 3, 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roterman, I.; Slupina, M.; Stapor, K.; Konieczny, L.; Gądek, K.; Nowakowski, P. Chameleon sequences - Structural effects in proteins characterized by hydrophobicity disorder. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 38506–38522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, N.; Miyashita, H.; Tamaki, S.; Kretsinger, R.H. Shrinking of repeating unit length in leucine-rich repeats from double-stranded DNA viruses. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, B.; Zheng, N.; Schulman, B.A.; Wu, G.; Miller, J.J.; Pagano, M.; Pavletich, N.P. Structural basis of the Cks1-dependent recognition of p27Kip1 by the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell 2005, 20, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchay, S.; Wang, H.; Marzio, A.; Jain, K.; Homer, H.; Fehrenbacher, N.; Philips, M.R.; Zheng, N.; Pagano, M. GGTase3 is a newly identified geranylgeranyltransferase targeting a ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Busino, L.; Hinds, T.R.; Marionni, S.T.; Saifee, N.H.; Bush, M.F.; Pagano, M.; Zheng, N. SCFFBXL3 ubiquitin ligase targets cryptochromes at their cofactor pocket. Nature 2013, 496, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, H.; Rajan, M.; Canarie, E.R.; Hong, S.; Simoneschi, D.; Pagano, M.; Bush, M.F.; Stoll, S.; Leibold, E.A. FBXL5 regulates IRP2 stability in iron homeostasis via an oxygen-responsive [2Fe-2S] cluster. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Garcia, S.F.; Shi, H.; James, E.I.; Kito, Y.; Shi, H.; Mao, H.; Kaisari, S.; Rona, G.; Deng, S.; et al. Recognition of BACH1 quaternary structure degrons by two F-box proteins under oxidative stress. Cell 2024, 187, 7568–7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.L.; Van Molle, I.; Gareiss, P.C.; Tae, H.S.; Michel, J.; Noblin, D.J.; Jorgensen, W.L.; Ciulli, A.; Crews, C.M. Targeting the von Hippel–Lindau E3 ubiquitin ligase using small molecules to disrupt the VHL/HIF-1α interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4465–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Nguyen, B.; Wasti, S.D.; Xu, G. Plant leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase (LRR-RK): Structure, ligand perception, and activation mechanism. Molecules 2019, 24, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, N.; Miyashita, H.; Enkhbayar, P.; Kretsinger, R.H. Comparative geometrical analysis of leucine-rich repeat structures in the nod-like and toll-like receptors in vertebrate innate immunity. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1955–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibby, E.M.; Conte, A.N.; Burroughs, A.M.; Nagy, T.A.; Vargas, J.A.; Whalen, L.A.; Aravind, L.; Whiteley, A.T. Bacterial NLR-related proteins protect against phage. Cell 2023, 186, 2410–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrangou, R.; Marraffini, L.A. CRISPR-Cas systems: Prokaryotes upgrade to adaptive immunity. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duine, J.A.; Jongejan, J.A. Quinoproteins, enzymes with pyrrolo-quinoline quinone as cofactor. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989, 58, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, W.-D.; Göbel, G.; Diepholz, M.; Darji, A.; Kloer, D.; Hain, T.; Chakraborty, T.; Wehland, J.; Domann, E.; Heinz, D.W. Internalins from the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes combine three distinct folds into a contiguous internalin domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 312, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmann, J.D.; Chamberlin, M.J. Structure and function of bacterial sigma factors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1988, 57, 839–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, C.; Turkarslan, S.; Lee, D.-W.; Daldal, F. Cytochrome c biogenesis: The Ccm system. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolanin, P.M.; Webre, D.J.; Stock, J.B. Mechanism of phosphatase activity in the chemotaxis response regulator CheY. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 14075–14082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soanes, D.M.; Talbot, N.J. Comparative genome analysis reveals an absence of leucine-rich repeat pattern-recognition receptor proteins in the kingdom Fungi. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Marin, E.; Canosa, I.; Devos, D.P. Evolutionary cell biology of division mode in the bacterial Planctomycetes-Verrucomicrobia-Chlamydiae superphylum. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1964. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).