1. Introduction

The rapid development of autonomous vehicle technology has created transformative opportunities for the transportation industry, with the potential to enhance safety, efficiency, and accessibility. At the forefront of this innovation are connected autonomous vehicles (CAVs), which integrate advanced sensing systems such as radar and high-resolution cameras with onboard computing to independently perform safety-critical driving tasks without human intervention [

1,

2]. To achieve this, CAVs often utilize machine learning techniques, particularly deep neural networks (DNNs) and compressive sensing, to detect and classify objects, process environmental data, and support inter-vehicle communication [

3]. These technologies enable real-time perception and decision-making, allowing CAVs to interact with dynamic and often unpredictable traffic environments.

While the benefits of CAVs are substantial, reliance on machine learning and DNN-based perception systems introduces new risks. A key threat is adversarial attacks, where imperceptible input perturbations deceive neural networks, leading to misclassification of traffic signs, obstacles, or other roadway element [

4]. Such attacks can cause erroneous driving behavior in safety critical scenarios such as lane changes, merges, and intersection navigation, directly endangering passengers and road users [

5]. Beyond safety, adversarial vulnerabilities also threaten public trust and regulatory acceptance, as stakeholders must be confident that CAVs can withstand both potential digital and physical manipulations.

Current adversarial defense strategies, ranging from adversarial training to generative model defenses, are limited in scalability, generalizability, and real-time applicability. These shortcomings leave CAVs exposed to evolving threats, especially in safety-critical environments where even a single misclassification could have severe consequences. Addressing these vulnerabilities requires innovative approaches that combine robustness with transparency to foster confidence among regulators, developers, and end users.

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) has emerged as a promising tool for improving the interpretability and accountability of deep neural network (DNN)–based perception systems in CAVs. By exposing how models allocate attention and arrive at decisions, XAI can support system validation, debugging, and regulatory transparency in safety-critical applications. However, whether explanation-based signals can serve as reliable indicators of adversarial manipulation under realistic operating constraints require further investigation.

This research addresses this gap by critically evaluating the effectiveness and limitations of classifier-aware, explanation-based adversarial detection using NoiseCAM in a traffic sign recognition context. This study examines how explanation-space responses differ between clean, Gaussian-perturbed, and adversarial inputs and assesses whether these differences provide a robust detection signal. The goal is to clarify the conditions under which XAI contributes meaningful security insight, to identify its practical limitations in low-resolution perception pipelines, and to inform the responsible integration of explainability into safety-critical autonomous vehicle systems.

2. Literature Review

Adversarial attacks on CAVs are closely linked to the vulnerabilities of DNNs, which form the backbone of modern perception and decision-making systems. Although DNNs provide efficient real-time object recognition for autonomous driving [

6], they struggle to detect adversarial examples, inputs imperceptible to humans but capable of misleading neural networks during testing or deployment [

7]. This limitation poses a significant risk in safety-critical contexts, as even small perturbations can trigger misclassifications with high confidence [

8].

The principle of adversarial threat modeling is often divided into white-box and black-box settings [

9]. In white-box attacks, adversaries exploit full knowledge of model parameters to generate highly effective adversarial examples. By contrast, black-box attacks conceal model details, requiring adversaries to estimate gradients through substitute models. Although white-box attacks typically achieve higher success rates [

10], black-box attacks are more reflective of real-world threats due to limited model transparency.

2.1. Types of Adversarial Attacks

Several adversarial attack methods have been developed to exploit vulnerabilities in DNNs. One of the most common is the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) [

11], a white-box approach that perturbs input data using gradients from neural backpropagation. Although relatively simple, FGSM can cause a significant drop in classification accuracy with only minimal perturbations, though its effectiveness decreases against more robust defense strategies [

12,

13]. In contrast, sticker attacks represent a physical adversarial method, in which small patches or stickers are strategically placed on real-world objects to mislead visual recognition systems [

14]. These attacks are particularly concerning for CAVs because they demonstrate how inexpensive, real-world manipulations can compromise critical functions such as traffic sign recognition and object detection.

2.2. Impact on CAV Perception Systems

CAV perception systems, which rely on camera, LiDAR, radar, and GPS data, are highly susceptible to adversarial perturbations. Misclassification of objects can lead to unsafe driving decisions, such as failing to recognize a stop sign [

4]. Kim et al. [

15] found that while cameras are vulnerable to pixel-level manipulations, LiDAR can be attacked through jamming or spoofing, and radar through false-signal injection. Such disruptions not only compromise individual vehicles but also pose systemic risks to traffic safety and efficiency [

16].

2.3. Defensive Approaches

To mitigate adversarial risks, researchers have explored both proactive and reactive defense strategies [

7]. Proactive methods focus on improving the inherent robustness of models before attacks occur, often by retraining networks with perturbed examples or modifying loss functions to encourage stability. Reactive defenses, on the other hand, aim to detect or filter adversarial inputs after the model has been trained, functioning as a secondary safeguard against potential exploitation. Both approaches have advantages and limitations, and together they represent the primary avenues of research in DNNs.

One prominent proactive strategy is adversarial training, often combined with fuzz testing frameworks. Methods such as DLFuzz [

17], DeepXplore [

18], and DeepHunter [

19] introduce adversarial examples during training to improve resilience and increase neuron coverage, which is associated with stronger model generalization. While effective in boosting robustness, these approaches are computationally expensive and may come at the cost of reduced baseline accuracy [

20]. As a result, their practicality for real-time, safety-critical applications such as CAVs remains limited.

Other defenses leverage generative and denoising techniques to detect or correct adversarial inputs. Defense-GAN [

21], for instance, employs generative adversarial networks to reconstruct natural inputs, flagging deviations as potential adversarial examples. Similarly, I-Defender [

22] models the output distributions of hidden layers and uses statistical testing to identify and reject anomalous inputs. Denoising autoencoders represent another line of defense, treating adversarial perturbations as additive noise that can be filtered out before classification [

23,

24,

25,

26]. These approaches show promise in reducing the impact of adversarial examples, though challenges remain in ensuring scalability and maintaining classification accuracy across diverse attack types.

2.4. Summary

Despite notable progress in adversarial defense research, existing strategies remain limited in several key areas. Many approaches demonstrate strong performance against specific attacks in controlled settings but fail to generalize across diverse environments and real-world conditions. For instance, adversarial training improves resilience but is computationally intensive and often sacrifices baseline accuracy, making it less practical for time-sensitive CAV applications. Generative and denoising methods, while effective at filtering or reconstructing inputs, raise questions about scalability and efficiency when deployed in large-scale, real-time traffic systems. Likewise, XAI methods such as NoiseCAM offer valuable insights into network vulnerabilities but still face challenges related to dataset resolution, noise, and model architecture variability.

The broader implication is that no single defense method offers a comprehensive solution against adversarial attacks. As a result, the field is shifting toward hybrid, classifier-aware frameworks that integrate proactive training, reactive filtering, and interpretability-driven diagnostics. These layered defenses not only strengthen robustness against diverse adversarial threats but also build the transparency needed to foster confidence among regulators, developers, and end users. For CAVs, where both safety and trust are paramount, such approaches are especially critical. Future research must therefore prioritize adaptive solutions capable of countering both digital and physical adversarial attacks while also developing standardized evaluation benchmarks tailored to autonomous driving environments. Establishing these benchmarks will ensure fair comparisons across methods, encourage cross-disciplinary collaboration, and facilitate the translation of research into practical, real-world safety gains. Within this context, the integration of traditional defenses with XAI frameworks, serves as a promising pathway toward achieving resilient, transparent, and trustworthy perception systems.

3. Method

Understanding how adversarial perturbations cause misclassification is a prerequisite for safeguarding deep neural networks (DNNs) against such attacks. Accordingly, this study utlizes an XAI–based analysis of a traffic sign recognition network, inspecting layer-wise classification activations to characterize the model’s internal behavior. By visualizing and interpreting these activations, we reveal how adversarial perturbations reshape the network’s response patterns. Building on prior work in adversarial sample detection [

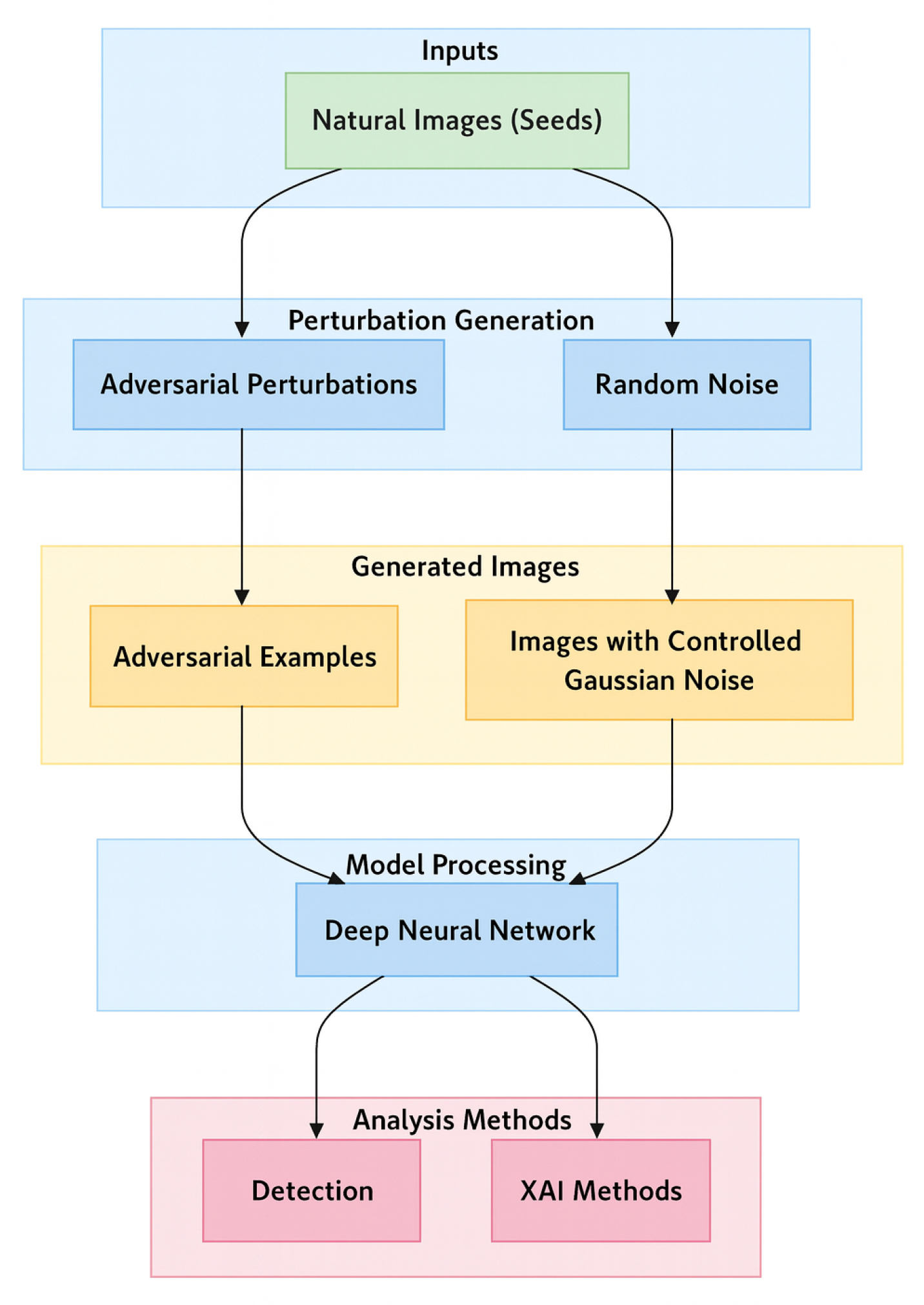

27], we extend classifier-aware XAI techniques to evaluate adversarial robustness. The overall framework, from adversarial example generation to XAI-based detection, is summarized in

Figure 1.

3.1. Dataset and Data Preparation

In this study, the German Traffic Sign Recognition Benchmark (GTSRB) was analyzed, a widely used benchmark dataset for traffic sign recognition [

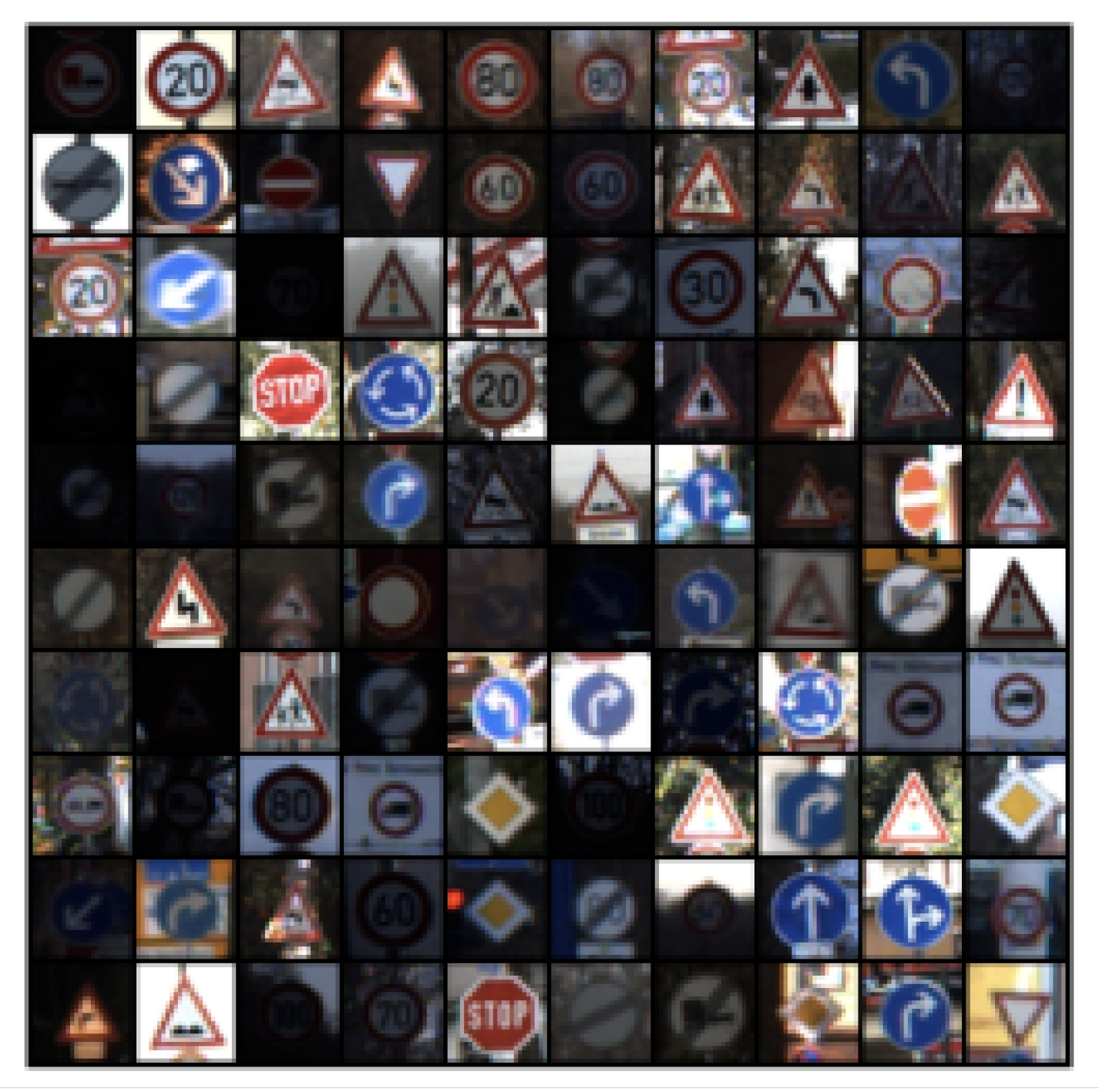

28]. The dataset contains 51,839 images of 43 classes of European traffic signs (39,209 training and 12,630 test images). A subset of representative samples is shown in

Figure 2, illustrating the variety of sign types and the differing levels of visibility in the dataset. The traffic signs were captured from multiple viewpoints and under diverse weather and lighting conditions, thereby reflecting realistic driving scenarios. Using this established benchmark ensured that results would be comparable to prior work and that the evaluation is conducted under a realistic and well-validated setting. For model development, all images were uniformly resized and flattened during the preprocessing stage.

3.2. Network Architecture

To evaluate adversarial robustness, generated adversarial perturbations (adversarial noise) were first generated from images in the GTSRB dataset. Let denote a clean seed image of height H, width W, and C channels (e.g., for an RGB color image). For notational convenience, also consider its vectorized form with .

The adversarial perturbation operator was defined as:

which maps a clean image

s and a perturbation strength

to an adversarial noise vector

Writing , each component represents the perturbation applied to the k-th pixel–channel entry of the image, and can be reshaped back to the tensor form in . In this study, DLFuzz was used to instantiate so as to generate while simultaneously maximizing neuron coverage.

To obtain a fair baseline for comparison, a Gaussian noise vector

was also constructed with the same dimensionality and overall magnitude as

. Let

denote the set of adversarial noise vectors generated from

M seed images, where

. The empirical mean

and variance

of the adversarial noise was computed as:

Gaussian noise was then sampled according to:

where

denotes a Gaussian distribution,

is the

d-dimensional all-ones vector and

is the

identity matrix. In this way,

and

shared the same shape and global mean and variance, while

remains purely random Gaussian noise.

Based on these constructions, each seed image

was associated with three input variants: the clean image, an adversarially perturbed version, and a Gaussian-noise–corrupted version. These variants were then collected in the per-image input set:

With this, the overall augmented dataset was then given by:

where

and

denote, respectively, the adversarially perturbed and Gaussian-noise–corrupted variants of the seed image

.

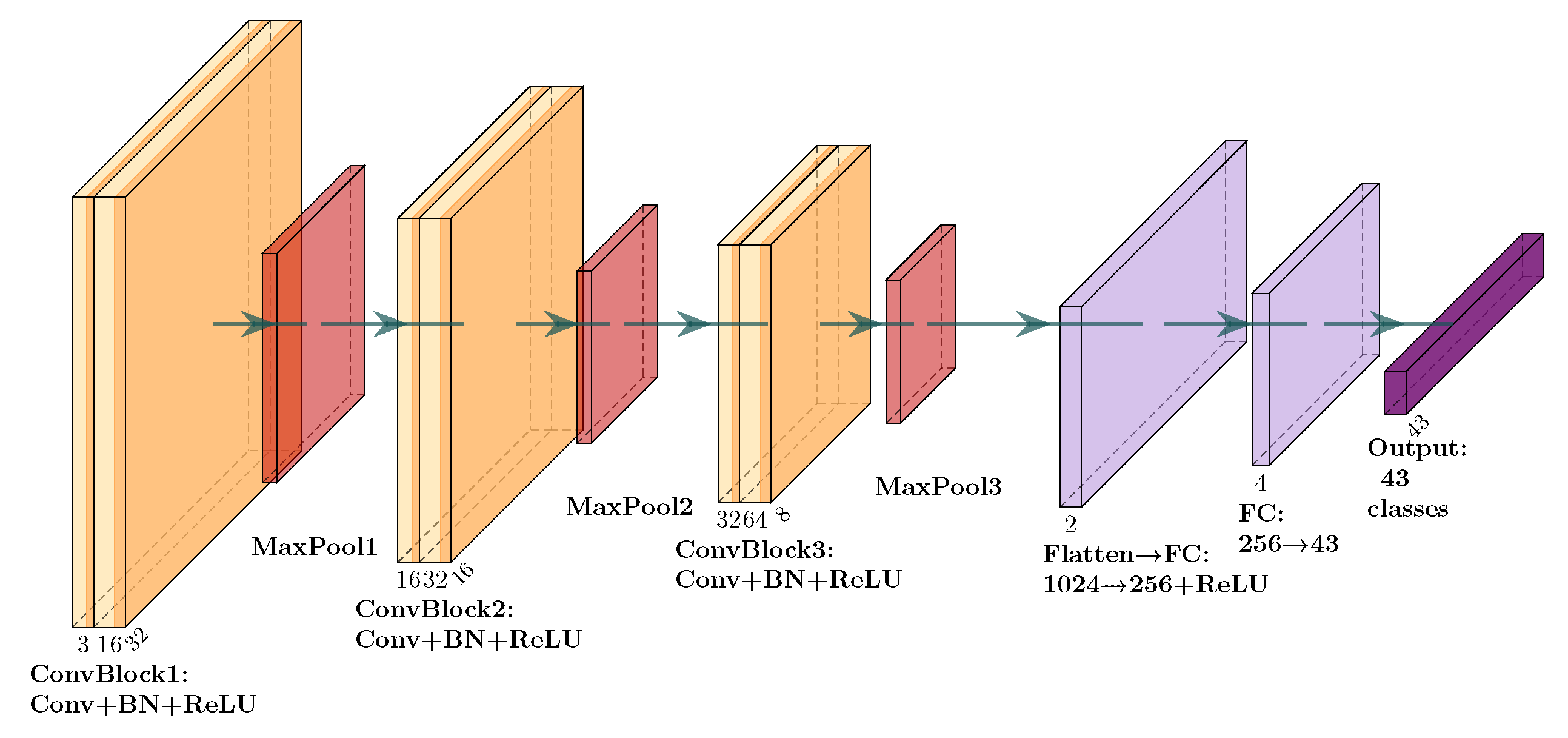

The classification model used in this study (as shown in

Figure 3) is a convolutional neural network (CNN) comprising three convolutional blocks, each consisting of a Conv2d layer, batch normalization, a ReLU activation function, and a max-pooling layer. The resulting feature maps were flattened and passed through two fully connected layers with 1024 and 256 neurons, respectively, followed by a softmax output layer that produces class probabilities over the 43 traffic sign classes. This CNN architecture achieved an accuracy of 90% on the GTSRB dataset [

29], thereby providing a reliable baseline for evaluating adversarial robustness under both perturbation and noise conditions.

3.3. Adversarial Example Generation

Adversarial perturbations were generated using DLFuzz [

17], a white-box attack method designed to maximize neuron coverage while producing adversarial examples constrained by a perturbation budget. For a given seed input

, the adversarial noise

was obtained by approximately solving the following constrained optimization problem:

where

c denotes the model’s output score for the originally predicted class on the clean input,

(

) denote the scores of the

K highest-scoring alternative classes under the perturbed input,

(

) represent the activations of a selected set of

m neurons, and

is a balancing coefficient that trades off prediction deviation against neuron activation. The constraint

ensures that the perturbation magnitude remains within a prescribed budget

, where the

norm is defined as:

with

denoting the

k-th component of

. In our experiments, we adopt

, corresponding to the Euclidean norm.

Intuitively, the first term in (

7) encourages the perturbed input to deviate from the original prediction by shifting probability mass toward competing classes, thereby inducing misclassification. The second term promotes stronger activation of additional internal neurons, increasing overall neuron coverage. Higher neuron coverage indicates that a larger portion of the network’s decision logic has been exercised, which in turn increases the likelihood of exposing hidden errors and corner cases [

18]. DLFuzz iteratively updates

to jointly satisfy these two objectives under the norm constraint, and the resulting perturbation

is applied to the original image to obtain an adversarial example.

In contrast to the Gaussian baseline noise constructed above, which was independently and identically distributed across input dimensions, adversarial perturbations generated by DLFuzz tend to form structured spatial patterns that selectively disrupt filter activations. This difference becomes apparent in the subsequent class activation map visualizations, where adversarial noise often suppresses or shifts salient regions, whereas Gaussian noise primarily introduces small, diffuse fluctuations. Empirically, it was observed that both Gaussian noise and adversarial perturbations induce measurable deviations in network behavior; however, Gaussian noise rarely alters the top-1 prediction, whereas adversarial perturbations frequently lead to misclassification under the same perturbation magnitude.

To quantify when a layer is considered compromised, Gaussian noise was used as a reference baseline. For each layer, a deviation measure was computed that captures how strongly its activation pattern under perturbation departs from the clean baseline. The median deviation observed under Gaussian noise was then used as a threshold: if the deviation induced by adversarial perturbations exceeds this median Gaussian deviation, it regarded the corresponding layer as exhibiting abnormal behavior beyond what would be expected under random noise of equivalent magnitude.

3.3.1. NoiseCAM for Adversarial Example Detection

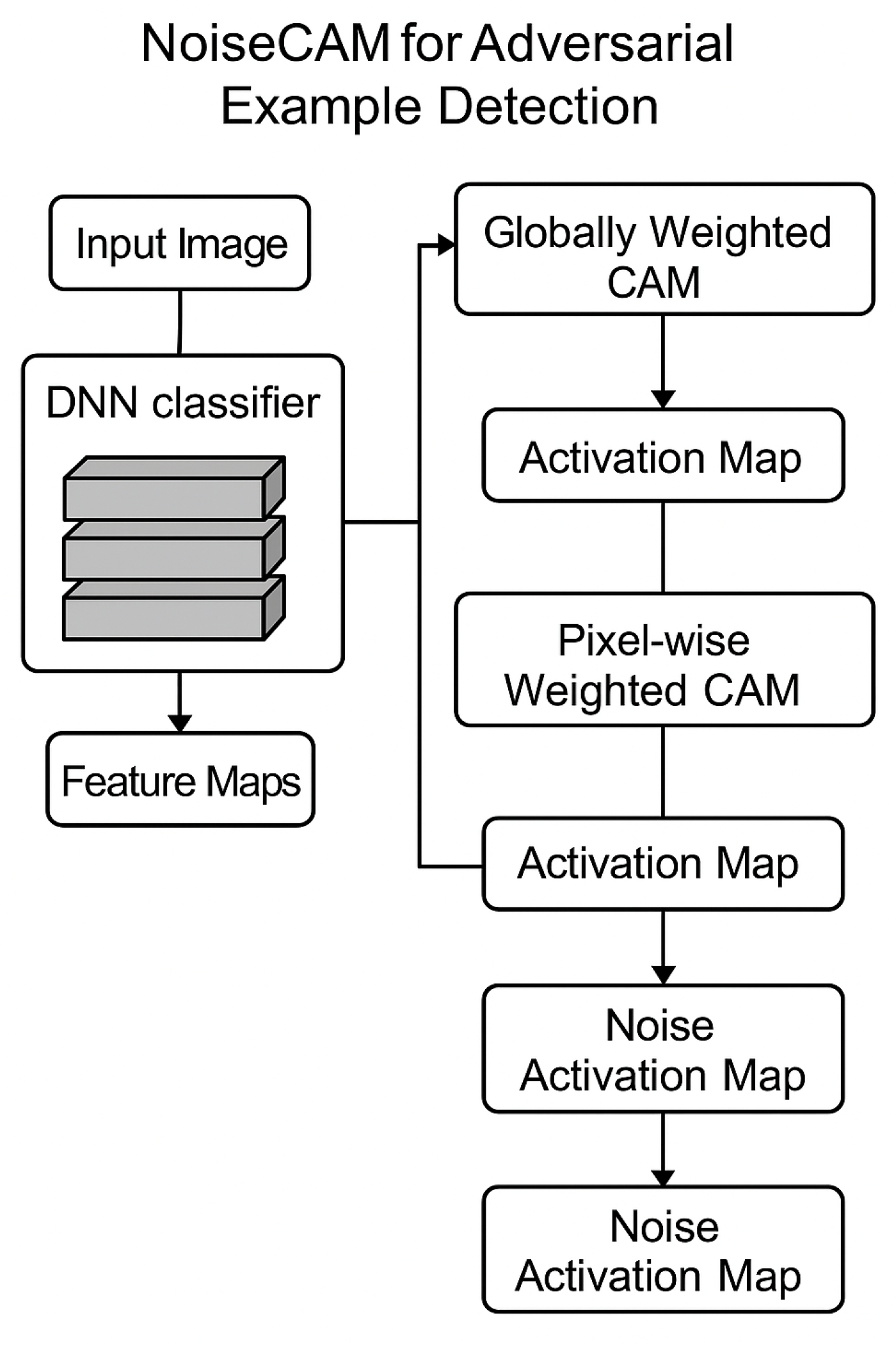

Having constructed adversarial and Gaussian perturbations and defined a layer-wise deviation baseline, a mechanism was required to localize these behavioral changes in the input space and to derive an image-level detection signal. To this end, adversarial example detection was conducted using NoiseCAM [

27], an XAI algorithm that integrates GradCAM++ [

30] and LayerCAM [

31] to produce robust class activation maps (

Figure 4).

NoiseCAM leverages gradient information from internal convolutional layers of the classifier to attribute the model’s prediction to spatial regions in the input. Specifically, it combines two complementary visualization techniques, GradCAM++ and LayerCAM, to capture both global and fine-grained patterns in activation maps [

27]. The NoiseCAM workflow is organized into two primary components: (i) a globally weighted CAM, which aggregates feature-map importance at the class level, and (ii) a pixel-wise weighted CAM, which refines these attributions at the individual pixel level. In the present study, NoiseCAM was applied to the clean, Gaussian-corrupted, and adversarial variants in

to characterize how adversarial perturbations alter spatial attention relative to random noise of equivalent magnitude.

3.3.2. Globally Weighted CAM

As the first component of the NoiseCAM pipeline, a globally weighted class activation map was computed based on GradCAM++ [

30]. Consider the classifier’s predicted class

c with corresponding output score

for a given input. Let

denote the

k-th feature map of a selected convolutional layer, and let

be its value at spatial location

. The spatial gradient of the class score with respect to the feature map is given by:

which measures how sensitive the class score

is to perturbations at location

in feature map

.

To obtain refined gradient information, GradCAM++ [

30] introduces spatially varying coefficients

defined as:

where

and

index spatial locations in the feature maps. These coefficients reweight the contribution of each spatial position when aggregating channel-wise importance.

Global channel weights

were then obtained by aggregating the spatial coefficients and emphasizing positive gradients:

Finally, the globally weighted class activation map

is constructed as a weighted combination of the feature maps:

This globally weighted CAM provided a coarse, class-discriminative localization of features that contribute positively to the prediction of class c. In the proposed framework, was computed for the clean, Gaussian-noise, and adversarial variants in and later compare these maps to assess how adversarial perturbations redistribute the model’s spatial attention relative to random noise of equivalent magnitude.

3.3.3. Pixel-Wise Weighted CAM

Complementary to the globally weighted CAM, the pixel-wise weighted CAM component follows the LayerCAM methodology [

31], in which each spatial location of a feature map is weighted individually. Using the same spatial gradients

defined in (

9), the pixel-wise weight at location

in feature map

for class

c is given by:

and the corresponding pixel-wise weighted feature map is:

where

denotes the feature map after applying the pixel-wise weights. This pixel-level weighting effectively suppresses low-contribution regions while preserving fine-grained activation details.

NoiseCAM integrates the globally weighted and pixel-wise weighted CAMs to isolate adversarial perturbations. First, the global channel weight

from (

11) is broadcast uniformly across the spatial dimensions of feature map

:

where

is an all-ones matrix with the same spatial resolution as

. Next, the pixel-wise spatial weight from LayerCAM is subtracted from this spatially uniform global weight to obtain a noise weight matrix,

which emphasizes locations where global importance cannot be explained by true pixel-wise activations.

Finally, the noise activation map

is computed by linearly combining the feature maps with the spatial noise weights:

Conceptually, the globally weighted CAM

captures both genuine class-discriminative activations and effects introduced by perturbations, whereas the pixel-wise weighted CAM primarily emphasizes true class-related activations and suppresses spurious responses. By contrasting these two views through (

16)–(

17), NoiseCAM highlights regions where the model’s attention is likely driven by adversarial perturbations. For non-adversarial inputs (e.g., clean or Gaussian-noised images),

tends to be near zero, while adversarial examples yield pronounced noise activation patterns, enabling effective discrimination between adversarial and non-adversarial inputs.

With this, these components can be summarized into a single end-to-end procedure for adversarial detection on GTSRB. Algorithm 1 outlines the full NoiseCAM-based detection pipeline, from noise generation to image-level classification.

3.4. Evaluation

Having defined the complete NoiseCAM-based detection pipeline in Algorithm 1, the framework was instantiated on the GTSRB dataset. This following subsection describes the selection of seed images for adversarial generation and the procedures used to quantify detection performance.

3.4.1. Seed Selection

Adversarial example generation was attempted for all images in the GTSRB dataset under the specified perturbation budget . However, not every seed image yielded a successful adversarial counterpart within this constraint and the optimization limits of DLFuzz. In total, valid adversarial examples were obtained for 52% of the dataset. This subset of seed images, together with their corresponding clean and Gaussian-noised variants, constitutes the augmented evaluation set used in the adversarial detection experiments described below.

3.4.2. Adversarial Example Detection

Adversarial detection performance was evaluated on the augmented evaluation set

previously described. For each input image

, the NoiseCAM pipeline (Algorithm 1) was used to compute the noise activation map

for the predicted class

c, from which a scalar detection score

was derived (e.g., by averaging normalized noise activations over the spatial domain). Using the subset of Gaussian-noised images

, the median score

was computed and adopted a simple thresholding rule: an input

x was classified as adversarial if

and as non-adversarial (clean or Gaussian-noised) otherwise.

|

Algorithm 1 NoiseCAM-Based Adversarial Detection on GTSRB |

-

Require:

Trained CNN classifier f; seed images from GTSRB; perturbation budget and norm order p; DLFuzz parameters; NoiseCAM layer choice; detection threshold rule (Gaussian median). -

Ensure:

For each input image x, adversarial/non-adversarial label and noise activation map .

- 1:

Adversarial and Gaussian Noise Construction - 2:

for each seed image do

- 3:

Represent in vectorized form with . - 4:

Use DLFuzz to approximately solve the constrained optimization problem in ( 7) under , obtaining adversarial noise . - 5:

end for - 6:

Compute the empirical mean and variance of all adversarial noises as defined in the noise statistics equations. - 7:

for each do

- 8:

Sample Gaussian noise as in the Gaussian noise definition, so that matches the dimensionality and global statistics of . - 9:

Form the three input variants as in the input set definition. - 10:

end for - 11:

Define the augmented dataset . - 12:

NoiseCAM Computation for a Given Input - 13:

for each input image do

- 14:

Forward x through classifier f to obtain predicted class c and score . - 15:

Select a convolutional layer and extract its feature maps . - 16:

Compute spatial gradients as in ( 9). - 17:

Compute GradCAM++ coefficients using ( 10). - 18:

Aggregate global channel weights via ( 11) and obtain the globally weighted CAM using ( 12). - 19:

Compute pixel-wise weights using ( 13), broadcast global weights as in ( 15), and derive noise weights using ( 16). - 20:

Compute the noise activation map according to ( 17). - 21:

Derive a scalar detection score from (e.g., by averaging normalized noise activations over the spatial domain). - 22:

end for - 23:

Threshold Selection and Adversarial Labeling - 24:

Using scores for Gaussian-noised images , compute the median Gaussian score . - 25:

for each input do

- 26:

if then

- 27:

Assign label adversarial - 28:

else

- 29:

Assign label non-adversarial: clean or Gaussian-noised - 30:

end if

- 31:

end for

|

4. Results

The investigation of adversarial-attack detection using NoiseCAM on the GTSRB dataset yielded several noteworthy observations. NoiseCAM, which integrates GradCAM++ and LayerCAM responses, achieved a detection accuracy of approximately 53% for adversarial examples. This level of performance is substantially lower than both the underlying classifier accuracy on clean GTSRB images (exceeding 90%) and previously reported NoiseCAM results on high-resolution natural-image datasets, underscoring the difficulty of reliably detecting adversarial perturbations in low-resolution traffic sign imagery. Several factors appear to contribute to this performance gap. The relatively small spatial resolution of GTSRB images ( pixels) constrains the amount of fine-grained structure available for class activation mapping, while pronounced variations in brightness and viewing conditions further degrade the stability of the resulting explanations. In addition, the CNN architecture utilized in this study is considerably shallower than widely used benchmark models such as VGG-16, and the inherently low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of GTSRB images reduces the separability between adversarial and non-adversarial NoiseCAM responses.

4.1. Classification Performance on Clean Data and Evaluation of Adversarial Attack Effectiveness

The baseline CNN model exhibited strong performance on clean traffic sign imagery prior to adversarial evaluation. The trained classifier achieved a test accuracy of 90.3% on the clean dataset, confirming reliable recognition of GTSRB traffic sign classes under nominal operating conditions. Training and validation metrics further indicated stable convergence, with no evidence of severe overfitting, establishing a robust baseline for adversarial robustness assessment. To assess vulnerability to adversarial manipulation, pixel-space FGSM attacks were applied to clean-correct test samples at multiple perturbation magnitudes ( = 0.01–0.10). Despite the high clean accuracy, adversarial perturbations produced substantial degradation in classification performance. Attack success rates increased monotonically with , exceeding 80% at moderate perturbation levels and approaching near-complete misclassification at higher values. These results indicated that small, bounded perturbations in the input pixel space were sufficient to induce incorrect model predictions with high probability. The combination of high clean classification accuracy (90%) and high adversarial susceptibility emphasized the need for detection mechanisms that operate independently of raw classification confidence. These results established a stringent and realistic threat model for subsequent explainability-based detection experiments, ensuring that NoiseCAM would be evaluated under conditions representative of safety-critical perception systems exposed to adversarial disturbances.

4.2. Overall NoiseCAM-Based Adversarial Detection Performance

To evaluate adversarial detection performance beyond overall accuracy, the proposed NoiseCAM-based detector was evaluated using standard binary classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (ROC–AUC). Adversarial detection was formulated as a binary classification task, with adversarial inputs treated as the positive class and non-adversarial inputs consisting of clean and Gaussian-perturbed images. For each input, a scalar detection score was computed using a top-K concentration ratio, and a decision threshold was defined as the median score observed on Gaussian-noise samples, providing a data-driven baseline that reflects expected non-adversarial variability.

Using the Gaussian-median threshold (), the detector achieved an overall accuracy of on the GTSRB test set, with precision and recall of and , respectively, yielding an F1-score of . The resulting ROC–AUC of indicated limited separability between adversarial and non-adversarial inputs. Substantial false positives and false negatives reflected the difficulty of distinguishing adversarial perturbations from benign Gaussian noise under a conservative thresholding strategy.

When evaluated across FGSM perturbation strengths () using thresholds derived from the validation set and applied unchanged to the test set, NoiseCAM exhibited limited but non-zero discriminative capability. Detection accuracy ranged from to , with ROC–AUC values between and . Precision increased modestly from to as perturbation strength increased, while recall declined from at to at , resulting in F1-scores between and .

Although modest improvements in accuracy, precision, and ROC–AUC were observed with increasing perturbation magnitude, these gains did not scale with adversarial severity. Even at higher FGSM strengths, where attack success rates exceeded , detection recall deteriorated, indicating that successful adversarial attacks do not necessarily induce strongly separable changes in explanation-space representations. In real-world intelligent transportation systems, adversarial or adversarial-like perturbations may lead to incorrect traffic sign recognition without triggering downstream anomaly detection mechanisms. The observed detection accuracies suggest that explanation-based detectors relying solely on spatial attribution inconsistencies may be insufficient as standalone safeguards in low-resolution perception pipelines. This reinforces the importance of complementary robustness strategies, such as architectural enhancements, multi-layer or temporal explanation aggregation, and the integration of explainability-based signals with other uncertainty or consistency measures.

4.3. Ablation Study of NoiseCAM Components and Sensitivity to Perturbation Strength

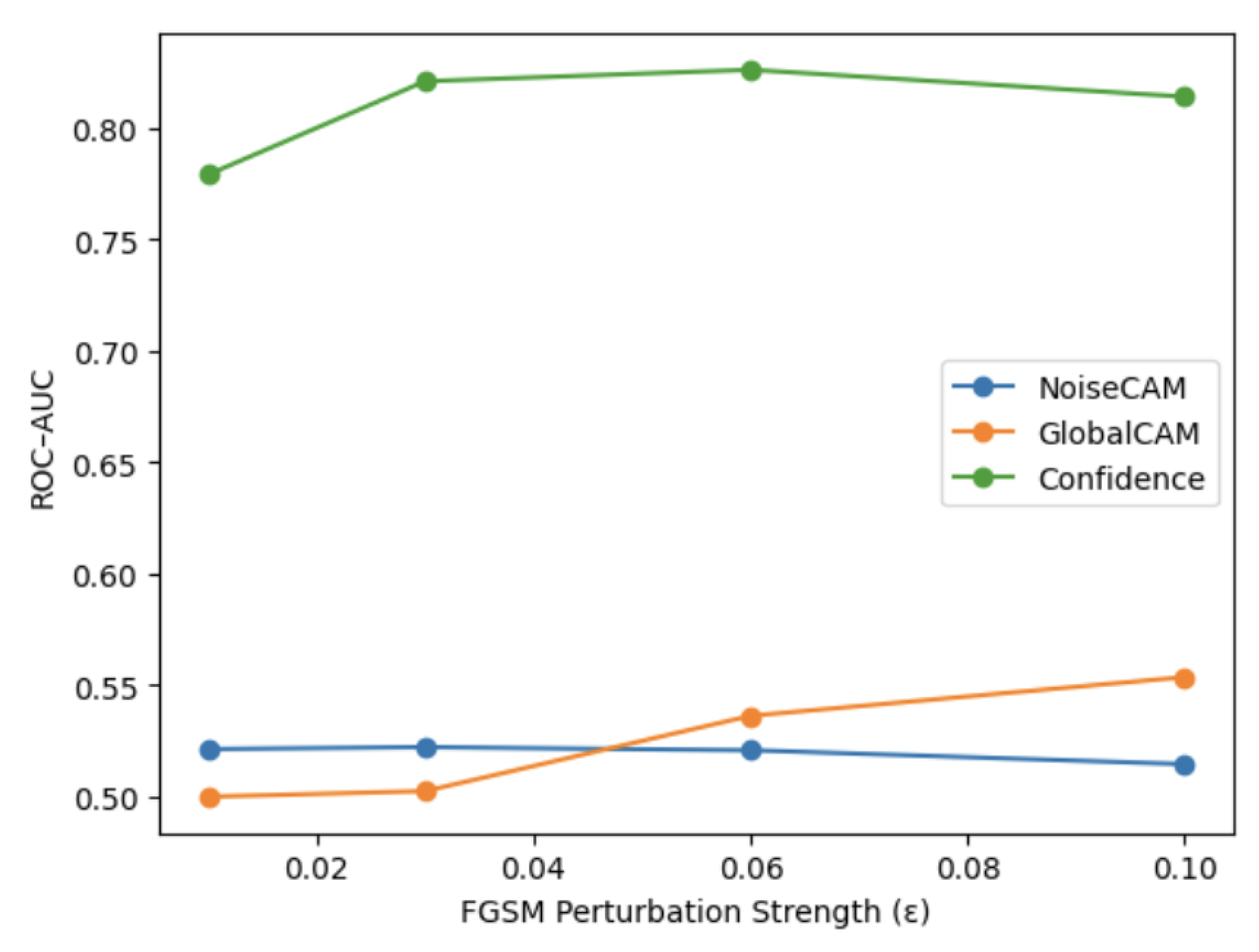

This section evaluates the contribution of NoiseCAM relative to alternative explanation-based and confidence-based detection signals and examines the sensitivity of adversarial detection performance to increasing perturbation strength. An ablation comparison was conducted across three detection mechanisms: NoiseCAM, GlobalCAM, and a confidence-based baseline. Detection performance was evaluated under FGSM attacks with perturbation magnitudes using thresholds derived from Gaussian-perturbed validation samples and applied unchanged to the test set.

Across all perturbation strengths, NoiseCAM exhibited moderate but consistent detection capability. Globally-weighted CAM demonstrated comparable performance, with test accuracy between and and ROC–AUC values ranging from to . While GlobalCAM showed a modest upward trend in ROC–AUC as increased, this improvement did not translate into consistent gains in accuracy or F1-score, indicating similar limitations in attribution-space separability.

In contrast, the confidence-based baseline exhibited substantially stronger detection performance across all perturbation strengths, achieving ROC–AUC values between and and recall exceeding for all . However, this increased sensitivity was accompanied by a higher false positive rate, resulting in lower overall accuracy (–) compared to explainability-based methods. These results highlight a fundamental trade-off between sensitivity and specificity when relying on confidence-driven detection signals.

Figure 5 illustrates the sensitivity of ROC–AUC to perturbation strength for all three detection mechanisms. While confidence-based detection scale clearly with increasing adversarial magnitude, both NoiseCAM and GlobalCAM remain largely insensitive to perturbation strength. This divergence indicates that although adversarial perturbations strongly affect model confidence, they do not consistently induce proportional or separable changes in explanation-space representations. These findings suggest that NoiseCAM captures measurable but low attribution shifts and motivate further analysis of its internal components and detection signal structure.

4.4. Class-Wise Detection Performance Against Adversarial Attacks

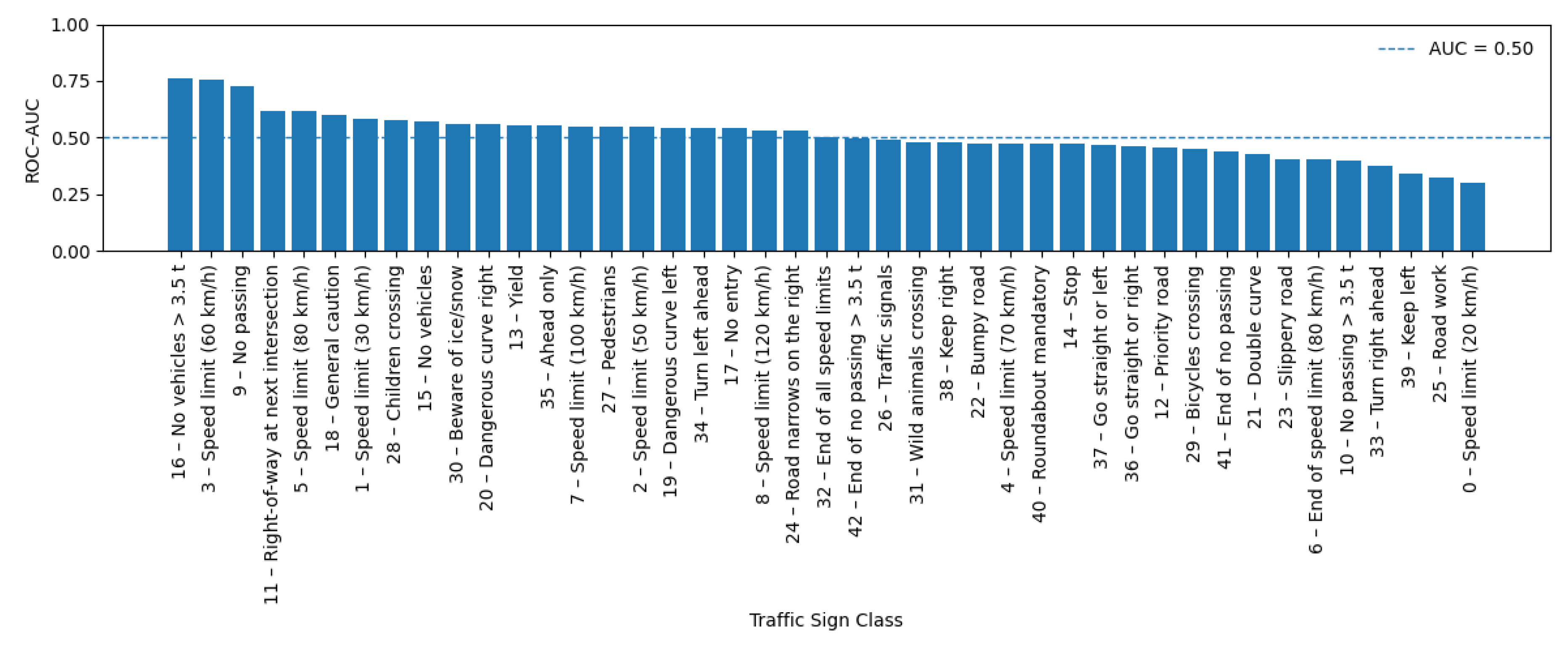

To better understand the variability in NoiseCAM-based adversarial detection performance, class-wise metrics were examined with respect to the semantic meaning of each traffic sign category, as defined by the GTSRB class labeling scheme. Class-wise ROC–AUC, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were computed on the test set for all 43 traffic sign classes at perturbation strengths = 0.01, 0.03, 0.06, and 0.10. Results consistently indicated that adversarial detectability varies substantially across traffic sign types, with performance strongly influenced by sign semantics, visual structure, and training frequency.

At the highest perturbation level ( = 0.10), the strongest detection performance was observed for a small subset of traffic sign categories characterized by distinctive geometric structure or strong symbolic content. In particular, Class 16: Vehicles over 3.5 tons prohibited, Class 3: Speed limit (60 km/h), and Class 9: No passing achieved the highest ROC–AUC values (). These signs are visually dominated by bold circular boundaries, high-contrast color schemes, and centrally located symbols, which may have helped to produce more localized and stable class activation patterns. As a result, adversarial perturbations more frequently induced measurable disruptions in explanation-space representations, improving separability between clean and adversarial samples for these categories. Notably, several speed limit signs (e.g., Class 1: Speed limit (30 km/h), Class 2: Speed limit (50 km/h), and Class 4: Speed limit (70 km/h)) consistently exhibited above-average detection performance across values. These signs are also among the most frequently represented classes in the training dataset, suggesting that both visual regularity and training exposure contribute to more stable explanation responses that are moderately sensitive to adversarial manipulation.

In contrast, a number of classes maintained limited detection performance across all perturbation strengths. The weakest performance at = 0.10 was observed for Class 0: Speed limit (20 km/h), Class 25: Road work, and Class 39: Keep left, which exhibited ROC–AUC values near or below 0.35. These categories either suffer from limited training samples (e.g., Class 0) or exhibit high intra-class visual variability (e.g., road work signage), resulting in diffuse and unstable explanation maps under both clean and adversarial conditions. Warning signs involving environmental or situational hazards—such as Class 20: Dangerous curve to the right, Class 21: Double curve, Class 22: Bumpy road, and Class 30: Beware of ice/snow, also tended to show weak separability. These signs often contain multiple graphical elements and rely on contextual interpretation rather than a single dominant visual cue, which potentially reduced the consistency of class activation patterns and limits the effectiveness of explainability-based detection.

Across all

values, the relative ranking of classes remained largely consistent, even as perturbation strength increased. Classes that demonstrated above-average detection performance at

= 0.01 generally remained among the strongest at

= 0.10, while poorly performing classes showed limited improvement despite stronger adversarial perturbations. This indicated that increased perturbation magnitude alone did not uniformly enhance detectability in explanation space, instead, detectability is potentially constrained by class-specific visual and semantic properties. For example, regulatory signs with rigid geometric templates (e.g., speed limits, overtaking prohibitions, mandatory direction signs such as Class 38: Keep right) exhibited gradual but consistent improvements in detection metrics as

increased.

Figure 6 illustrates the class-wise NoiseCAM-based adversarial detection performance.

From a safety-critical perspective, these findings highlight the limitation of explainability-based adversarial detection; detection reliability can be uneven across traffic sign categories. While some high-frequency regulatory signs exhibit modestly improved detectability, several rare or visually complex warning signs. which often correspond to hazardous roadway conditions, remain less detectable under adversarial perturbation. This imbalance suggests that explainability-based detectors such as NoiseCAM may offer partial and class-dependent protection, rather than a uniformly reliable safeguard across all traffic sign types.

4.5. Qualitative Visual Analysis of NoiseCAM Responses

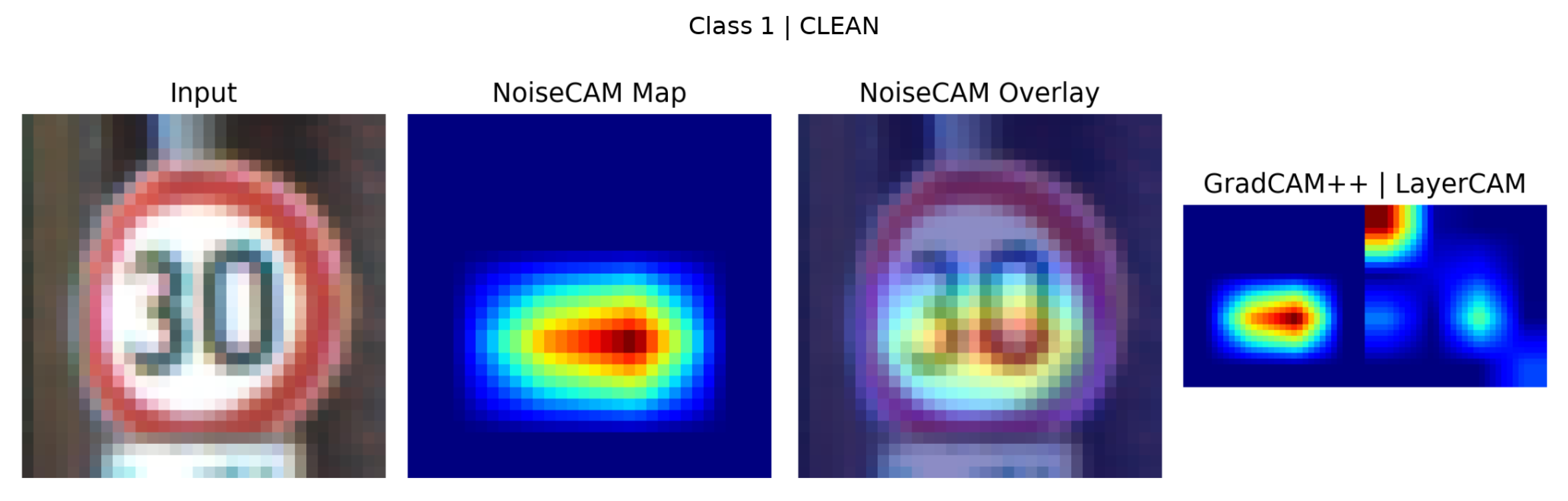

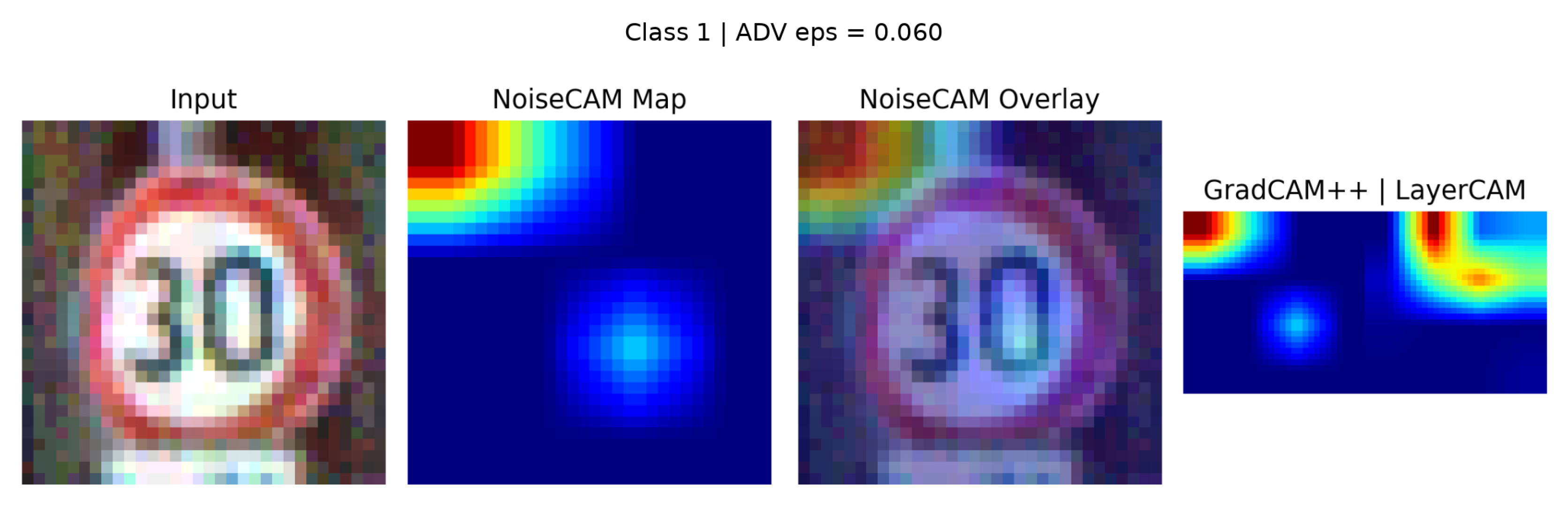

To complement the quantitative detection results, a qualitative analysis was conducted to examine NoiseCAM attribution behavior on representative clean and adversarial samples (

) .

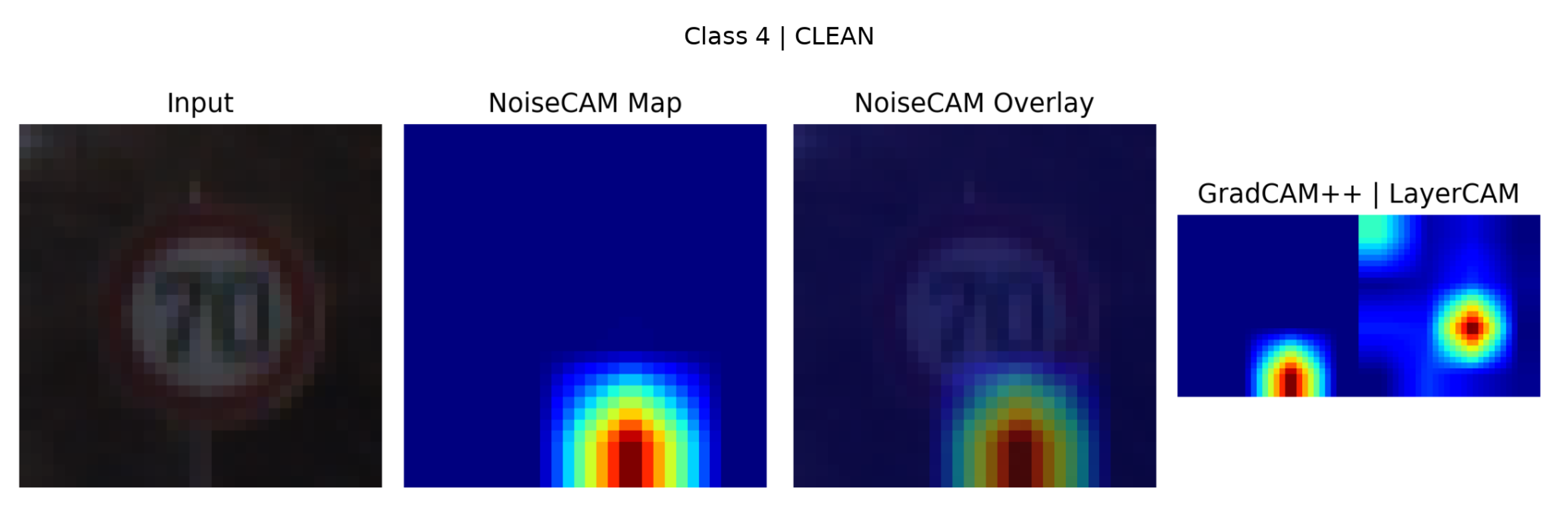

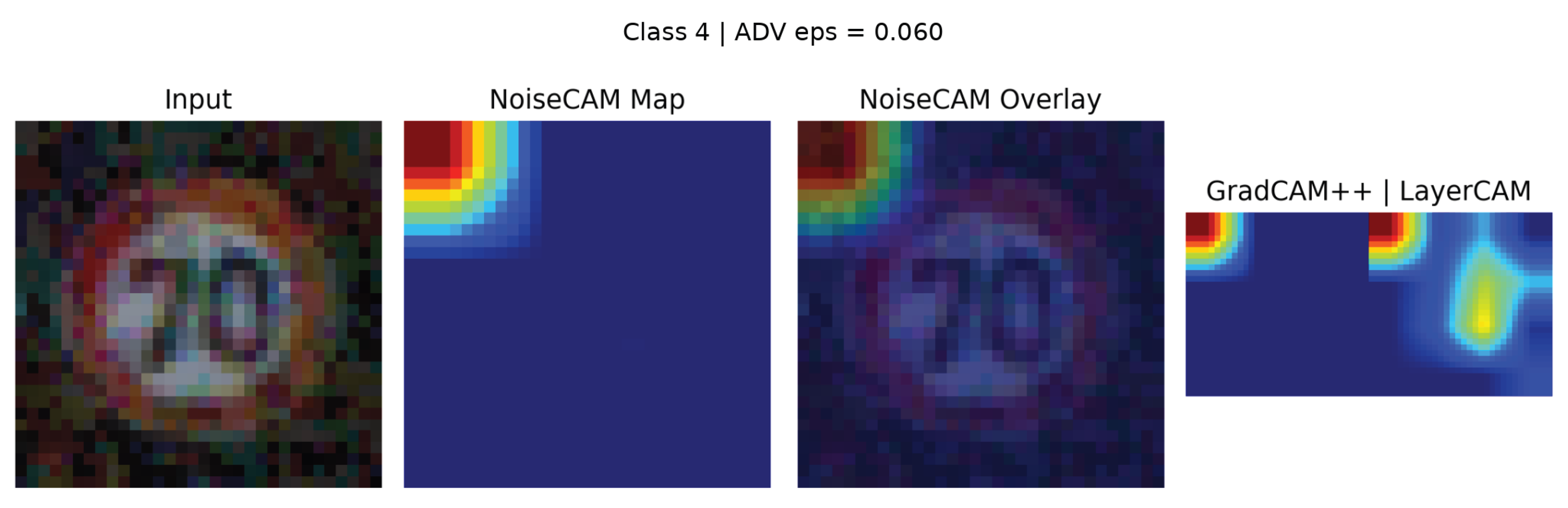

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present clean and FGSM-adversarial Class 1 examples. While

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present a clean and FGSM-adversarial Class 4 examples (

). Each figure illustrates the input image, NoiseCAM overlay, raw NoiseCAM map, and corresponding GradCAM++/LayerCAM visualizations.

For clean inputs, NoiseCAM consistently produces compact and semantically meaningful attribution regions aligned with salient traffic sign features, such as digit contours and high-contrast interior regions. This behavior is observed across varying illumination and scale conditions in the Class 1 examples, indicating robustness to benign visual variation. Compared to GradCAM++ and LayerCAM, NoiseCAM yields smoother and more globally coherent attribution patterns, whereas gradient-based methods exhibit more fragmented and localized activations.

In the clean Class 4 sample, NoiseCAM maintains sparse, well-localized attribution focused on structurally informative regions of the sign, with minimal background activation. In contrast, GradCAM++ and LayerCAM display multiple disjoint activation clusters, some of which extend beyond the sign boundary. Under FGSM perturbation, NoiseCAM responses do not exhibit distinctive spatial artifacts. Despite successful misclassification, the adversarial sample shows attribution patterns that remain broadly aligned with the original sign structure, with differences primarily reflected as reduced peak intensity and mild diffusion rather than spatial displacement. These adversarial responses closely resemble those observed in clean samples.

The qualitative results demonstrate that adversarial perturbations do not consistently produce unique spatial signatures in NoiseCAM attribution space. The strong visual overlap between clean and adversarial explanations supports the performance previously discussed and highlights a fundamental limitation of explainability-based adversarial detection relying solely on spatial attribution consistency.

4.6. Summary

These results highlight the limitations of XAI-based methods for adversarial defense. While NoiseCAM provides a viable foundation for robustness evaluation, the findings suggest that future work should prioritize experiments on higher-resolution datasets, the use of more resilient backbone architectures, and the development of adaptive XAI strategies to improve detection performance in safety-critical CAV perception systems.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study align with prior research demonstrating both the promise and the limitations of XAI-based approaches in adversarial contexts. While explainability methods have shown improved robustness and localization capabilities on high-resolution natural image datasets, their effectiveness degrades substantially under the constraints typical of traffic sign recognition. In particular, the limited detection performance of NoiseCAM on the GTSRB dataset is consistent with prior observations that XAI-driven signals are sensitive to dataset characteristics such as image resolution, illumination variability, and inherent signal-to-noise ratio [

32]. Earlier evaluations of GradCAM++ and LayerCAM on large-scale datasets such as ImageNet reported stronger localization of adversarial perturbations and more stable attribution patterns [

33,

34]. However, the contrast observed here underscores that such performance does not directly translate to compact, safety-critical vision pipelines.

A key insight from the results is that successful adversarial attacks do not necessarily induce proportional or separable changes in explanation-space representations. Across multiple perturbation strengths, NoiseCAM responses for adversarial inputs exhibited substantial overlap with those produced by benign Gaussian noise of equivalent magnitude. Even when adversarial perturbations caused high misclassification rates, explanation maps often remained spatially aligned with genuine class-discriminative regions, differing primarily in intensity diffusion rather than in distinct spatial displacement. This behavior suggests that explanation-space inconsistency alone is an unreliable indicator of adversarial manipulation in low-resolution perception systems.

When compared with alternative defense strategies, NoiseCAM retains a clear advantage in interpretability by visually isolating attribution behavior and supporting post hoc model analysis [

27,

35]. However, generative and denoising defenses such as Defense-GAN and autoencoder-based approaches have, in some cases, demonstrated higher raw detection performance, albeit at the expense of transparency and increased computational overhead. Similarly, adversarial training remains one of the most effective proactive defense strategies, but its high computational cost and reduced flexibility limit applicability in real-time CAV deployments [

36]. These trade-offs suggest that NoiseCAM is best positioned as a complementary diagnostic component rather than a standalone adversarial defense.

The ablation and sensitivity analyses further highlight a broader tension identified in the literature, detection mechanisms that prioritize sensitivity and accuracy often do so at the expense of interpretability, while explainable methods sacrifice discriminative power in favor of transparency and accountability [

37,

38]. Confidence-based detection signals, for example, exhibited substantially higher sensitivity to adversarial perturbations but lacked explanatory insight and produced elevated false positive rates. In contrast, NoiseCAM and GlobalCAM provided consistent but weak detection signals that were largely insensitive to perturbation magnitude. For CAV applications, where regulatory acceptance, auditability, and stakeholder trust are critical alongside technical performance, this trade-off reinforces the importance of explainability as a supporting—not decisive—security mechanism.

Class-wise analysis revealed that adversarial detectability is strongly influenced by semantic and structural properties of traffic sign categories. Signs with rigid geometric templates and high training frequency exhibited modestly improved detection performance, whereas visually complex or underrepresented warning signs remained near limited detection even under stronger perturbations. From a safety perspective, this uneven reliability is particularly concerning, as warning and special-condition signs often correspond to hazardous roadway conditions. These findings indicate that explainability-based detection offers partial and class-dependent coverage rather than uniform protection across perception tasks.

Combined, the results suggest that XAI methods such as NoiseCAM are more effective as tools for robustness evaluation, failure analysis, and system auditing than as real-time adversarial detectors in low-resolution autonomous driving pipelines. Rather than replacing traditional defenses, explanation-based signals should be integrated within hybrid frameworks that combine interpretability with uncertainty estimation, architectural robustness, temporal consistency checks, and proactive training strategies. Such layered approaches are more likely to balance efficiency, transparency, and reliability in safety-critical connected autonomous vehicle systems.

5.1. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the experimental evaluation was conducted using the GTSRB dataset, which, while widely studied, consists of relatively low-resolution images captured under controlled conditions. Although this reflects key characteristics of real-world traffic sign perception, the results may not directly generalize to higher-resolution perception tasks or multimodal sensing pipelines commonly used in modern camera systems and advanced autonomous vehicle platforms. Second, the analysis focused on gradient-based adversarial perturbations and explanation responses derived from a single CNN architecture. Different network architectures, training regimes, or attack families may exhibit distinct explanation-space behaviors, potentially influencing detectability. Third, NoiseCAM was evaluated as a standalone explanation-based detection signal, this study did not explore integrated or hybrid detection frameworks that combine explainability with uncertainty estimation, temporal consistency, or proactive robustness mechanisms. Finally, detection thresholds were derived from statistical baselines using Gaussian noise, which, may not fully capture the diversity of environmental variations encountered in operational driving scenarios.

6. Conclusion

This study evaluated the effectiveness and limitations of explanation-based adversarial detection using NoiseCAM in a traffic sign recognition setting representative of connected autonomous vehicle perception systems. Experimental results demonstrated that, while NoiseCAM provides meaningful insight into model attention and internal behavior, its ability to reliably distinguish adversarial inputs from benign perturbations is limited under realistic operating constraints. Detection performance remained limited across multiple perturbation strengths, reflecting substantial overlap between adversarial and non-adversarial explanation-space responses.

These findings highlight a fundamental limitation of relying solely on spatial attribution inconsistencies for adversarial detection in low-resolution, high-variability perception pipelines. In such contexts, adversarial perturbations can successfully induce misclassification without producing distinctive or separable explanation patterns. While XAI frameworks remain essential for transparency, interpretability, and regulatory accountability, their role in adversarial defense should be carefully scoped to avoid overreliance on explanation-space signals as indicators of security.

The primary contribution of this work lies in clarifying when and why explanation-based adversarial detection fails under conditions relevant to autonomous driving. By empirically identifying these limits, the study informs the responsible deployment of XAI in safety-critical systems and motivates the development of hybrid detection strategies that integrate explainability with complementary robustness and uncertainty measures. Future research should prioritize standardized, application-specific evaluation benchmarks for CAV scenarios, explore multi-modal and temporal detection signals, and further investigate how explainability can best support system assurance rather than function as a standalone defense. Collectively, these efforts will advance the safe, transparent, and trustworthy integration of AI-driven perception systems in connected autonomous vehicles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L., Y.L., and H.C.; methodology, Y.Y., R.G., B.D.P, and D.L.; software B.D.P. and Y.Y.; validation, B.D.P. and Y.Y; investigation, B.D.P., Y.Y., and D.L.; data curation, Y.Y., and B.D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y., B.D.P., and R.G.; writing—review and editing, B.D.P., Y.Y., R.G., D.L., Y.L. and H.C.; visualization, B.D.P. and Y.Y.; funding acquisition, D.L., Y.L., and H.C.; supervision, D.L., Y.L., and H.C.; project administration, D.L., Y.L., and H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the USDOT Tier-1 University Transportation Center (UTC) Transportation Cybersecurity Center for Advanced Research and Education (CYBER-CARE) (Grant No. 69A3552348332).

Data Availability Statement

References

- Shell Eco-Marathon. Autonomous vehicles: The future of self driving cars. Available online: https://www.shellecomarathon.com/stories/autonomous-vehicles.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Transport Canada. What you need to know about driver assistance technologies. Available online: https://tc.canada.ca/en/road-transportation/driver-assistance-technologies/what-you-need-know-about-driver-assistance-technologies (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Martinez-Buelvas, L.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Grant-Smith, D.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. Impact of Connected and Automated Vehicles on Transport Injustices. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1609–1614. [Google Scholar]

- Shibly, K.; Hossain, M.; Inoue, H.; Taenaka, Y.; Kadobayashi, Y. Towards Autonomous Driving Model Resistant to Adversarial Attack. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahe, A.; Wang, C.; Jeyapratap, A.; Xu, K.; Zhou, L. Dynamic adversarial attacks on autonomous driving systems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.06701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Anpalagan, A.; Guan, L.; Khwaja, A.S. Deep learning for object detection and scene perception in self-driving cars: Survey, challenges, and open issues. Array 2021, 10, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; He, P.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X. Adversarial examples: Attacks and defenses for deep learning. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2019, 30, 2805–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawaz, H.I.; Forestier, G.; Weber, J.; Idoumghar, L.; Muller, P.A. Adversarial attacks on deep neural networks for time series classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 International joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN); IEEE, 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, K.; Zheng, T.; Qin, Z.; Liu, X. Adversarial attacks and defenses in deep learning. Engineering 2020, 6, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chang, X.; Rodríguez, R.J.; Wang, J. DI-AA: An interpretable white-box attack for fooling deep neural networks. Information Sciences 2022, 610, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, Conference Track Proceedings. San Diego, CA, USA, 7-9 May 2015; Bengio, Y., LeCun, Y., Eds.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, T.R.; Das, N.; Maitra, P.S.; Some, B.; Saha, R.; Adhikary, O.; Bose, B.; Sen, J. Evaluating Adversarial Robustness: A Comparison Of FGSM, Carlini-Wagner Attacks, And The Role of Distillation as Defense Mechanism. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.04245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, Z.L.; Yiu, S.M.; Liu, C. State-of-the-art optical-based physical adversarial attacks for deep learning computer vision systems, 2023. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.12249. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Guo, Y.; Yu, J. Adversarial sticker: A stealthy attack method in the physical world. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022, 45, 2711–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kaur, A. A Survey on Adversarial Robustness of LiDAR-based Machine Learning Perception in Autonomous Vehicles. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.13778. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, T.; Sheakh, M.A.; Jui, A.N.; Sharif, O.; Hasan, M.Z. A review of cyber attacks on sensors and perception systems in autonomous vehicles. Journal of Economy and Technology 2023, 1, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhao, Y.; Song, H.; Jiang, Y. Coverage guided differential adversarial testing of deep learning systems. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 2021, 8, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, K.; Cao, Y.; Yang, J.; Jana, S. DeepXplore: Automated whitebox testing of deep learning systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles; 2017; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Ma, L.; Juefei-Xu, F.; Xue, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; See, S. DeepHunter: A coverage-guided fuzz testing framework for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; 2019; pp. 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, A.; Verma, V.; Kannala, J.; Bengio, Y. Interpolated adversarial training: Achieving robust neural networks without sacrificing too much accuracy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security; 2019; pp. 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samangouei, P.; Kabkab, M.; Chellappa, R. Defense-gan: Protecting classifiers against adversarial attacks using generative models. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.06605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hong, P. Robust detection of adversarial attacks by modeling the intrinsic properties of deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018.

- Gu, S.; Rigazio, L. Towards deep neural network architectures robust to adversarial examples. arXiv arXiv:1412.5068. [CrossRef]

- Gondara, L. Medical image denoising using convolutional denoising autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW); 2016; pp. 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, U.; Park, J.; Jang, H.; Yoon, S.; Cho, N.I. Puvae: A variational autoencoder to purify adversarial examples. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 126582–126593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Sharanya, S. An integrated Auto Encoder-Block Switching defense approach to prevent adversarial attacks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.10930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Renkhoff, J.; Velasquez, A.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Niu, S.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Song, H. Noisecam: Explainable ai for the boundary between noise and adversarial attacks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ); IEEE, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stallkamp, J.; Schlipsing, M.; Salmen, J.; Igel, C. The German traffic sign recognition benchmark: a multi-class classification competition. In Proceedings of the The 2011 international joint conference on neural networks; IEEE, 2011; pp. 1453–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Shorna, S.A.; Ayon, W.I.Z.; Apu, K.I.Z. Harnessing CNN Architecture for Accurate Traffic Sign Classification: Findings from the GTSRB Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Computing, Applications and Systems (COMPAS); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhay, A.; Sarkar, A.; Howlader, P.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Grad-CAM++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2018; pp. 839–847. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.T.; Zhang, C.B.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, M.M.; Wei, Y. LayerCAM: Exploring hierarchical class activation maps for localization. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 5875–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfaress, I.; Bouhoute, A.; Zinedine, A. Advancing traffic sign recognition: Explainable deep CNN for enhanced robustness in adverse environments. Computers 2025, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. International Journal of Computer Vision 2019, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Pan, X.; Yao, Y. CF-CAM: Cluster filter class activation mapping for reliable gradient-based interpretability. arXiv arXiv:2504.00060.

- Cai, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Xu, H.; Wang, P.; Li, W.; Pan, Y. Generative adversarial networks: A survey towards private and secure applications. Journal of the ACM 2020, 37, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, R.G.; Sajjanhar, A.; Xiang, Y. Adversarial training for mitigating insider-driven XAI-based backdoor attacks. Future Internet 2025, 17, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohale, V.Z.; Obagbuwa, I.C. A systematic review on the integration of explainable artificial intelligence in intrusion detection systems. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2025, 8, 1526221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlicki, M.; Pawlicka, A.; Kozik, R. The survey on the dual nature of XAI challenges in intrusion detection and their potential for AI innovation. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).