Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

27 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

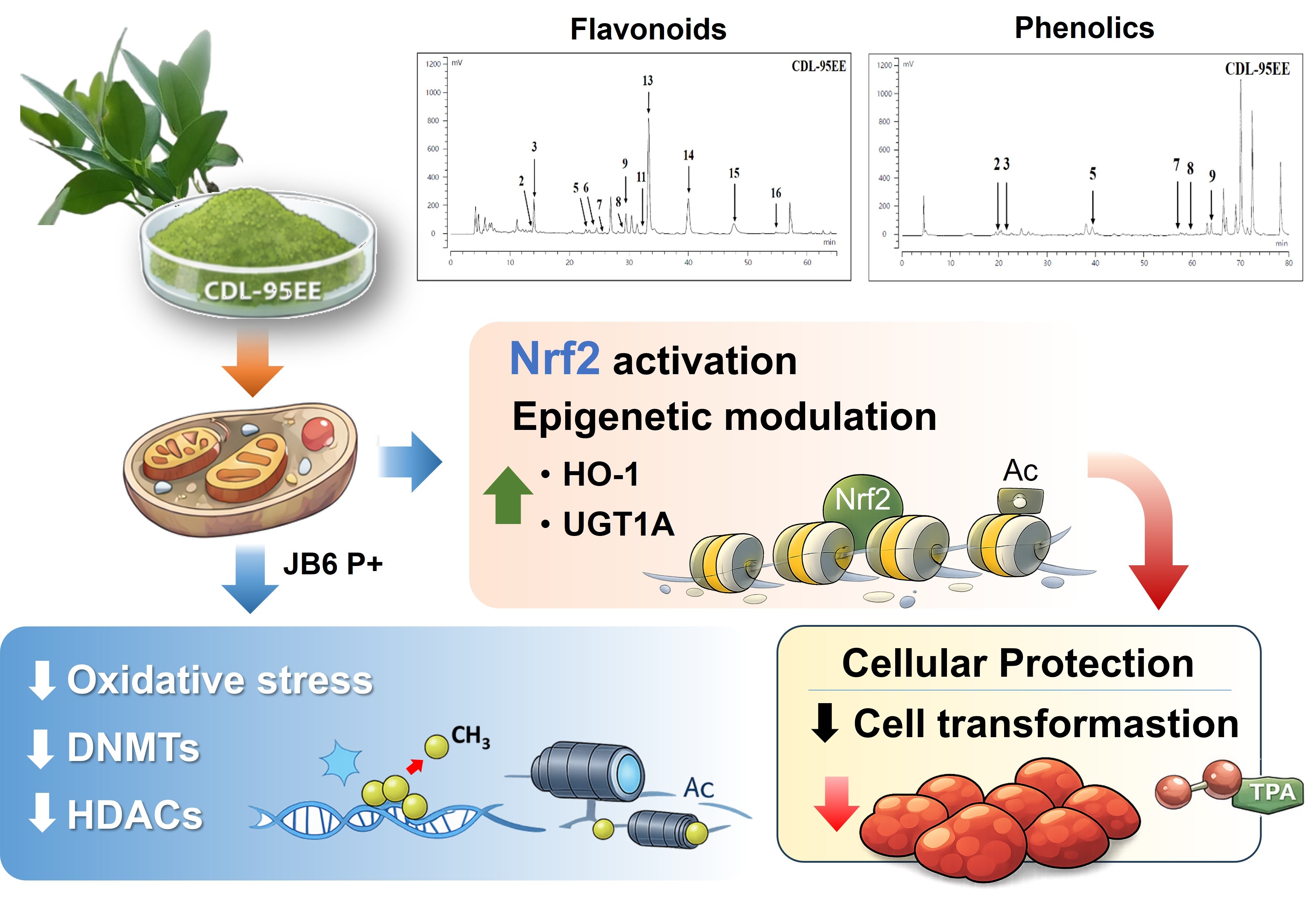

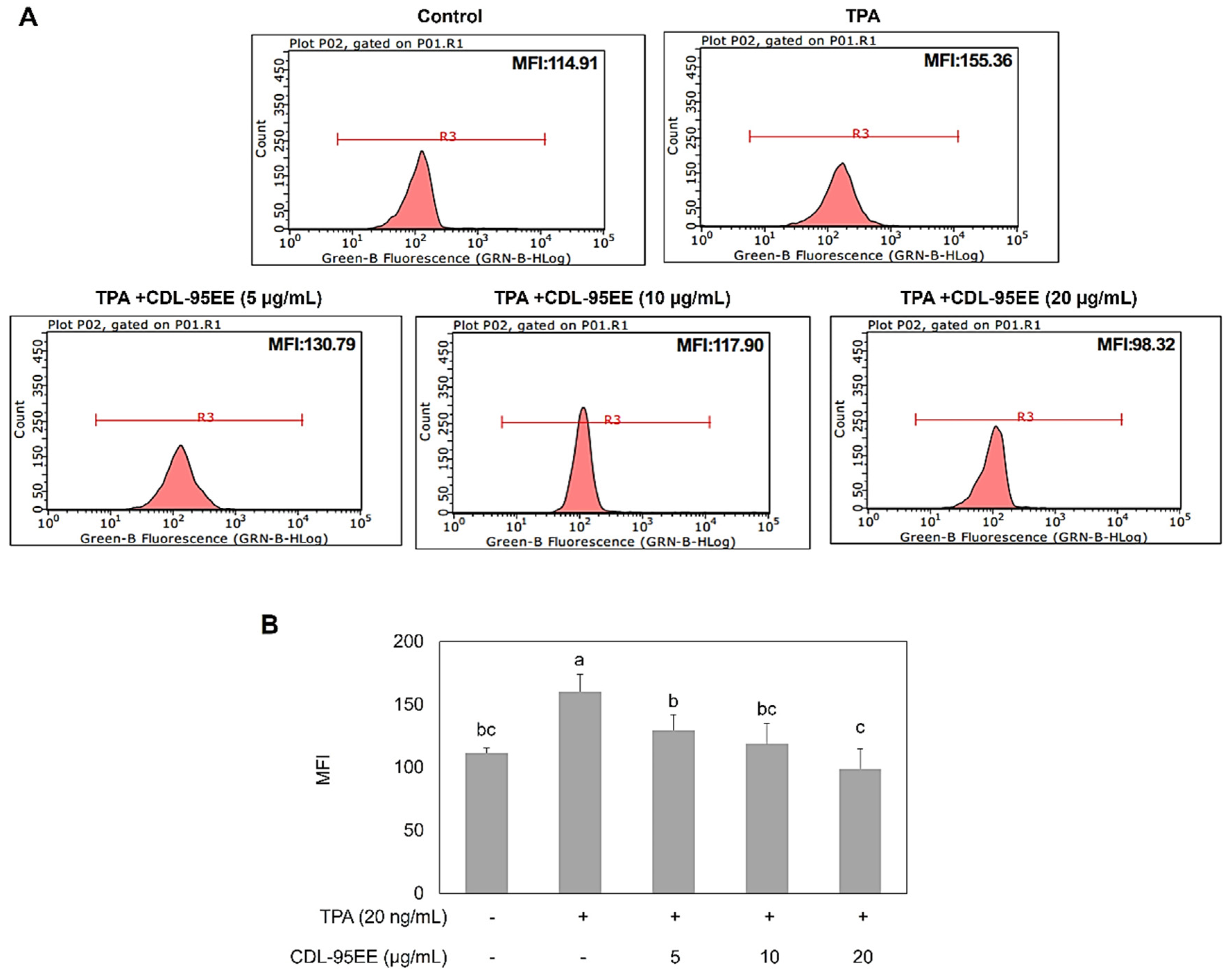

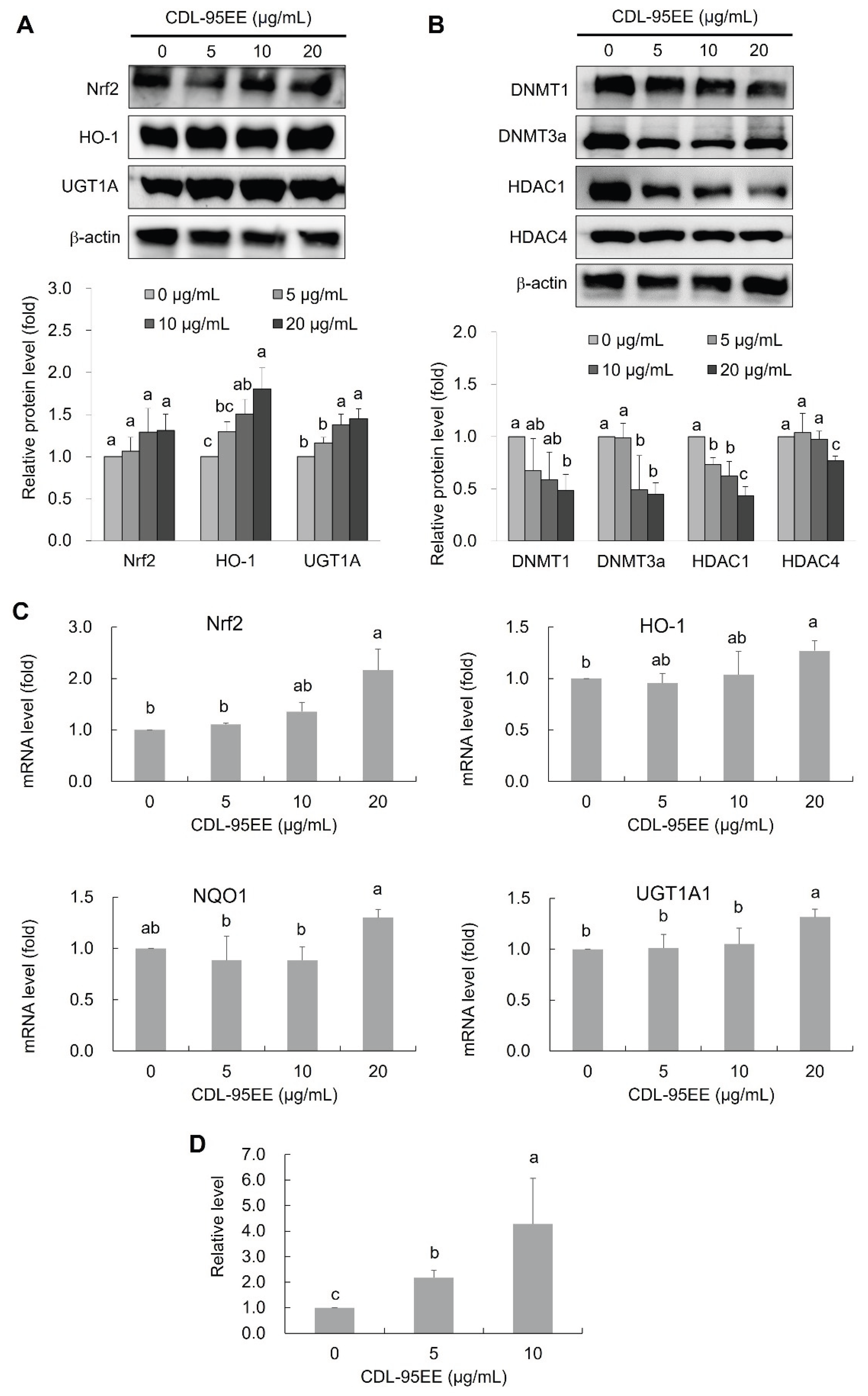

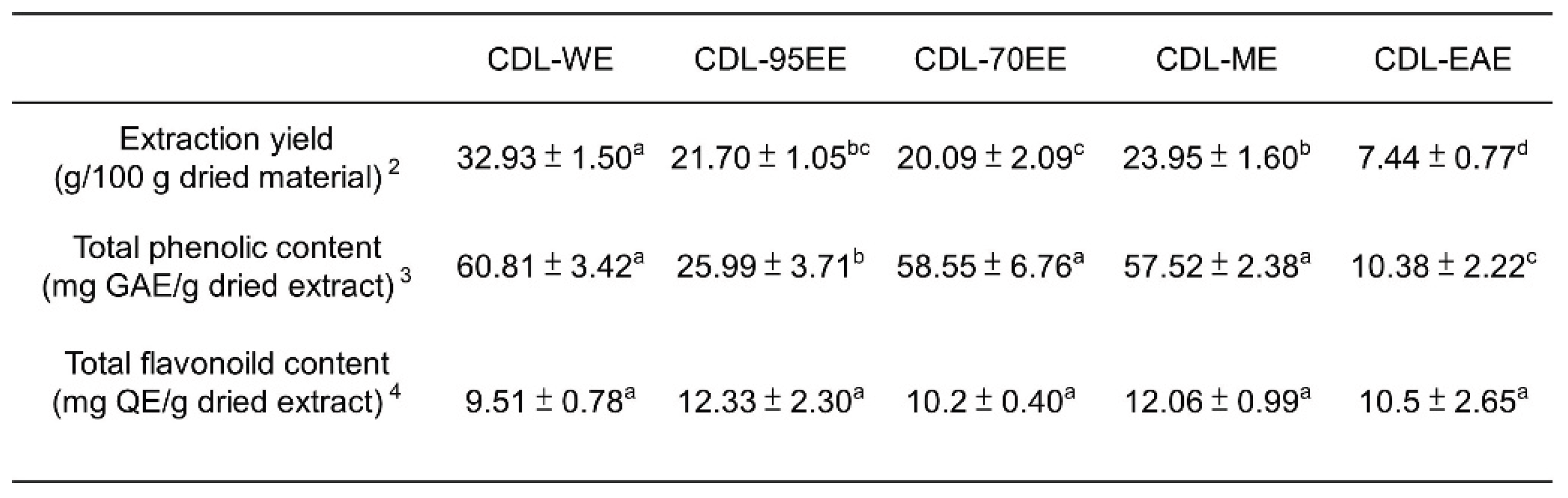

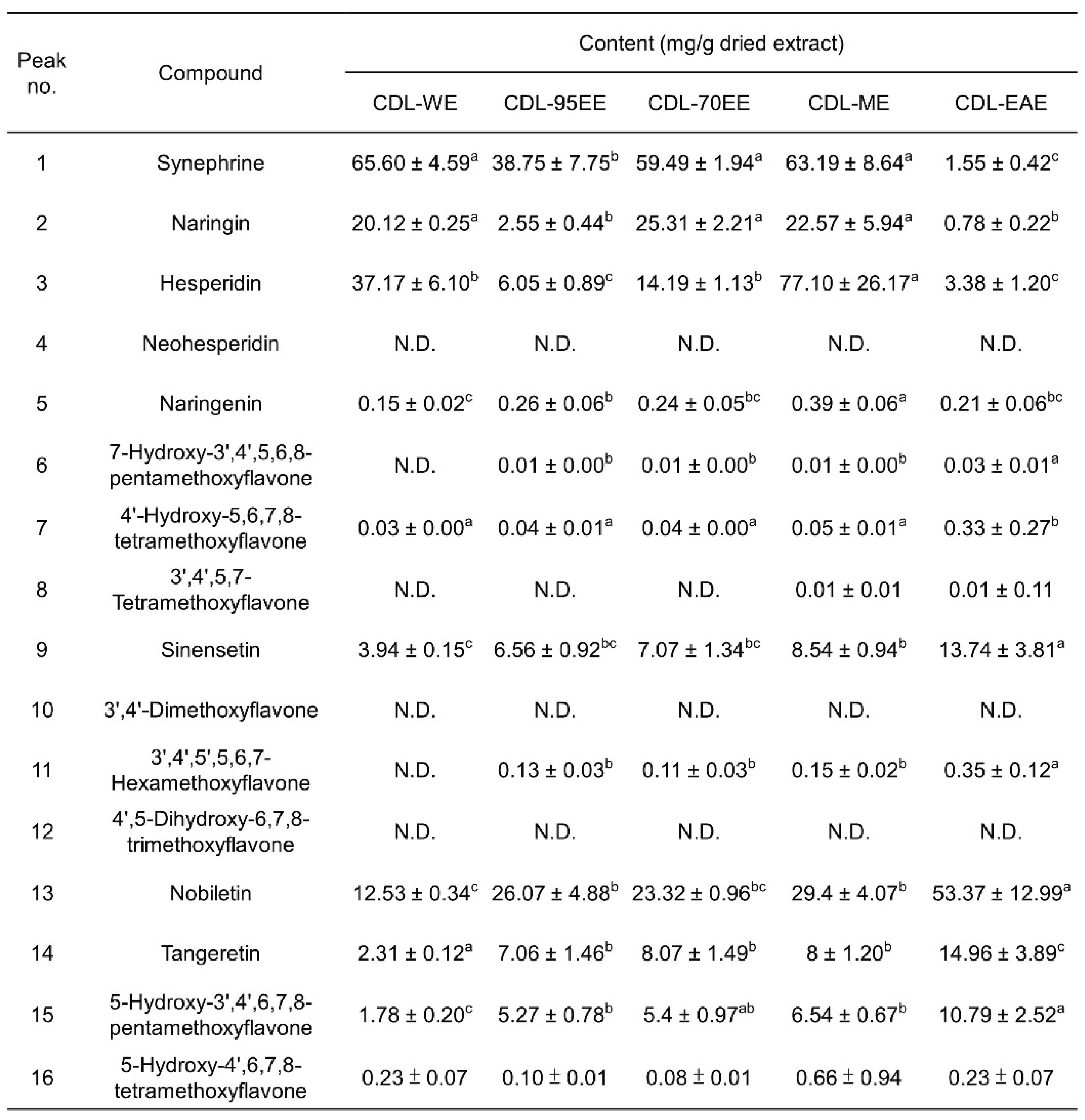

Many chronic diseases, including cancer, can be developed in conjunction with excessive intracellular oxidative stress and persistent inflammation. The importance of preventive strategies is highlighted by the potential of phytochemical interventions to mitigate these diseases. The purpose of this study was to investigate how Citrus depressa leaf (CDL) extracts can prevent TPA-induced carcinogenesis in mouse JB6 P+ skin epidermal cells. Both the water extract (CDL-WE) and the 95% ethanol extract (CDL-95EE) contain abundant flavonoids that inhibit TPA-induced cell transformation and colony formation without minimal cytotoxicity. Mechanistic studies indicated that CDL-95EE increased the gene expression of Nrf2-related detoxification and antioxidant enzymes such as UGT1A and HO-1, and decreased the accumulation of intracellular ROS. Furthermore, CDL-95EE also reduced the expression of epigenetic modifiers, including DNA and histone deacetylases (HDACs), suggesting that it is involved in epigenetic regulation. These findings indicate that CDL, an agricultural by-product, may be useful in cancer prevention through antioxidant and epigenetic mechanisms.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

2.2. Preparation of CDL Extracts

2.3. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.4. Determination of Total Flavonoids Content (TFC)

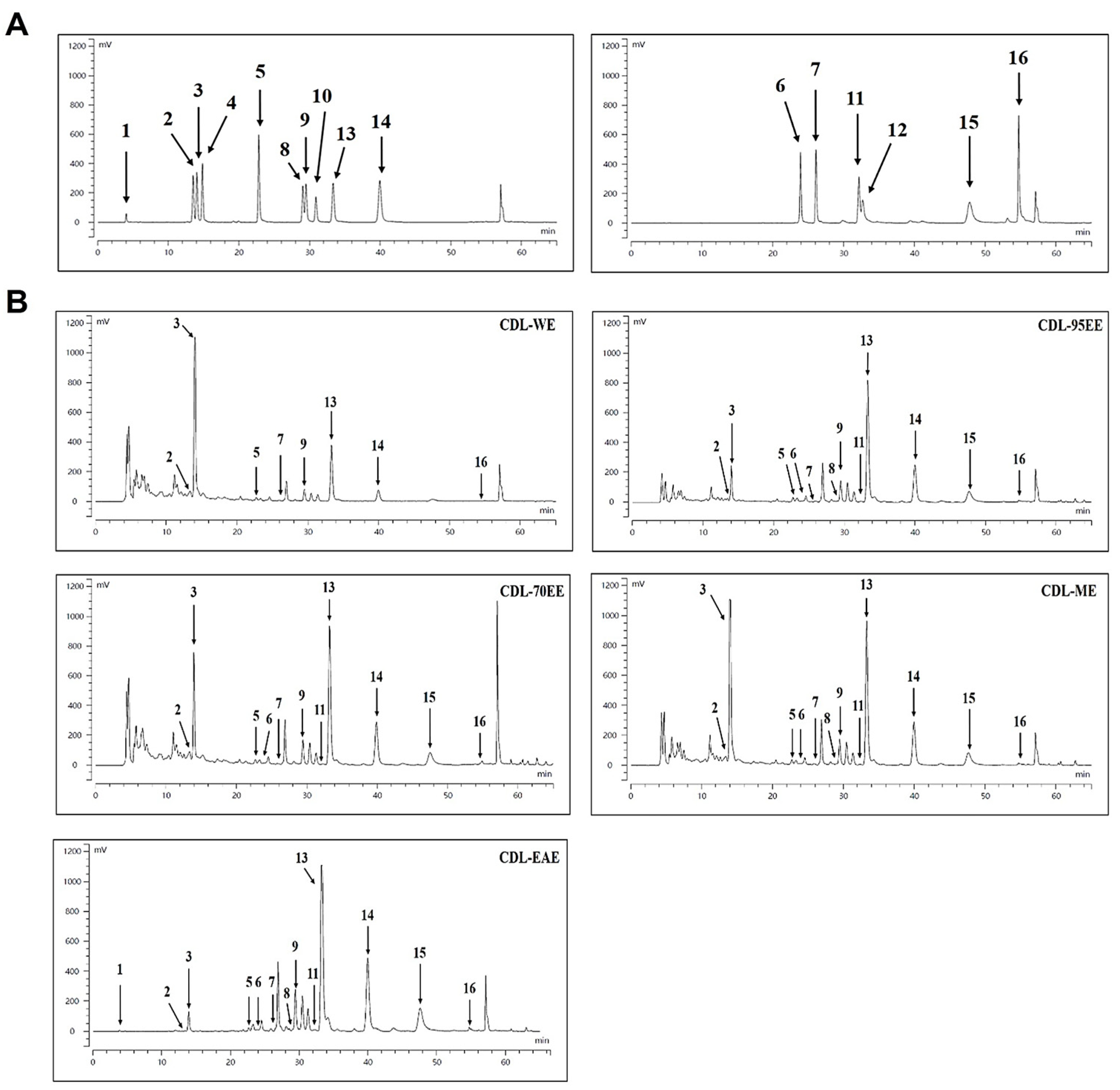

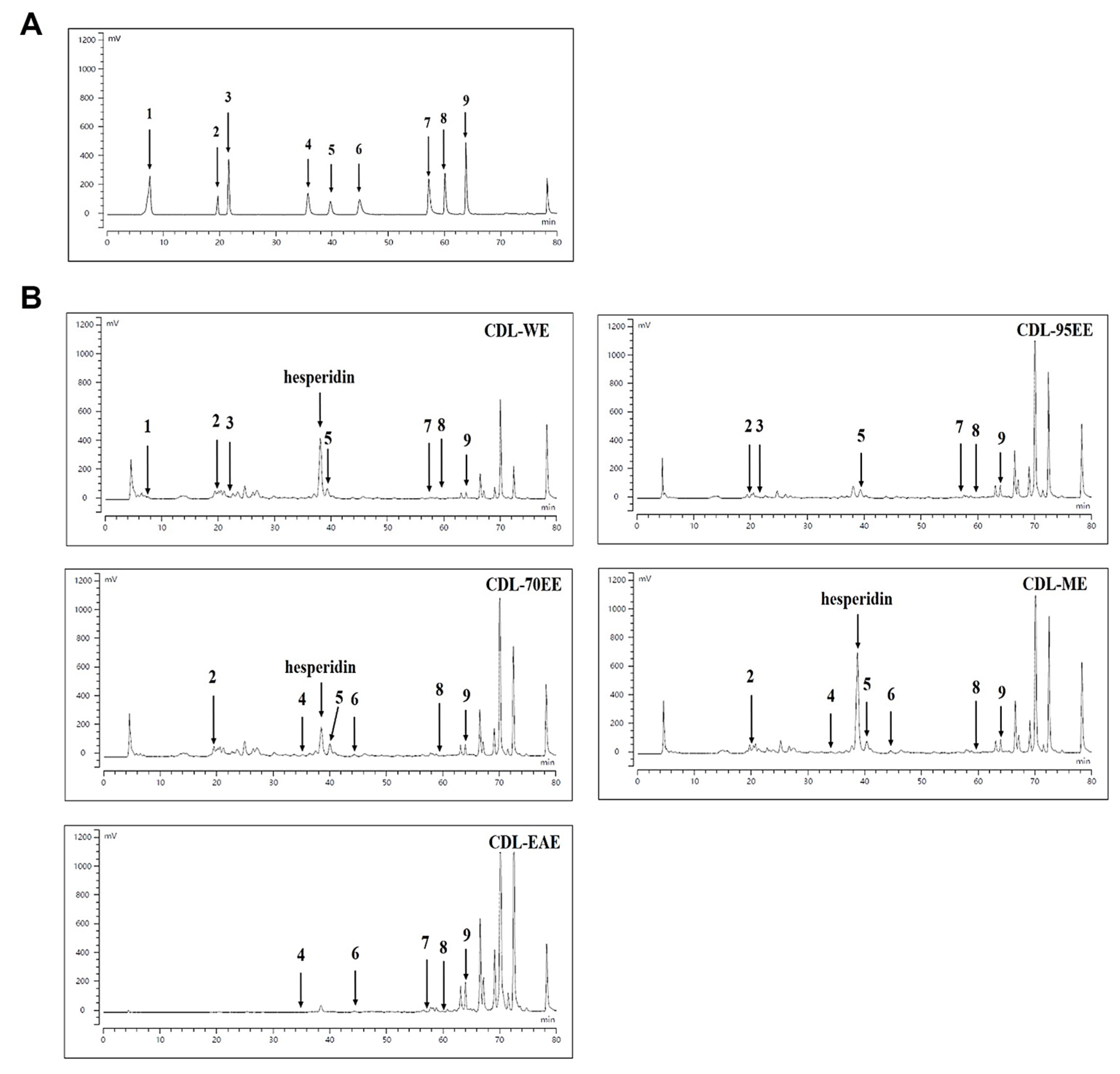

2.5. High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) of Major Compounds

2.6. Culture of JB6 P+ Cells

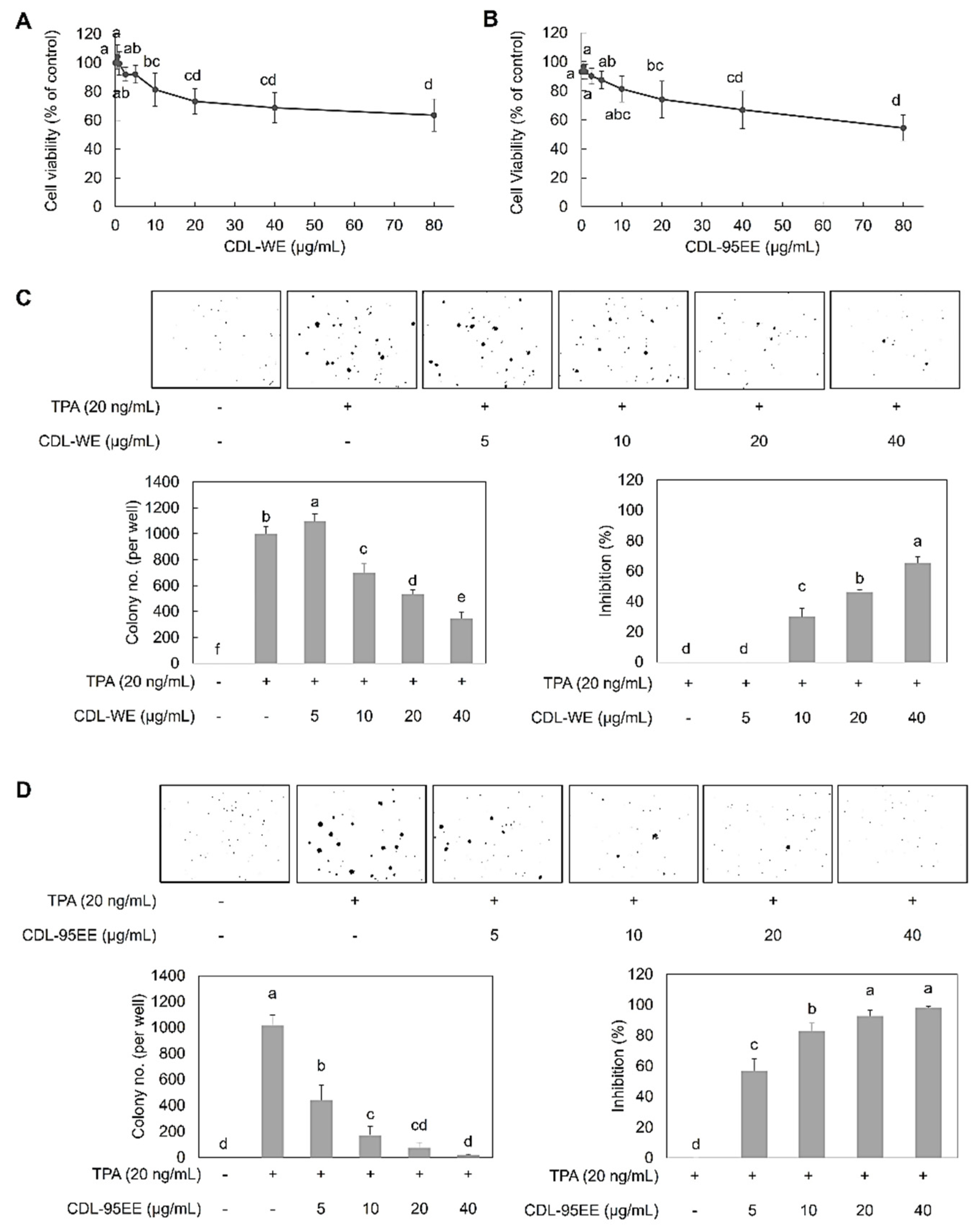

2.7. Cell Viability Assay

2.8. TPA-Induced JB6 P+ Cell Transformation Assay

2.9. ROS Level Assay

2.10. mRNA Expression Determination

2.11. Protein Determination

2.12. Quantitative Methylation-Specific PCR (qMSP)

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

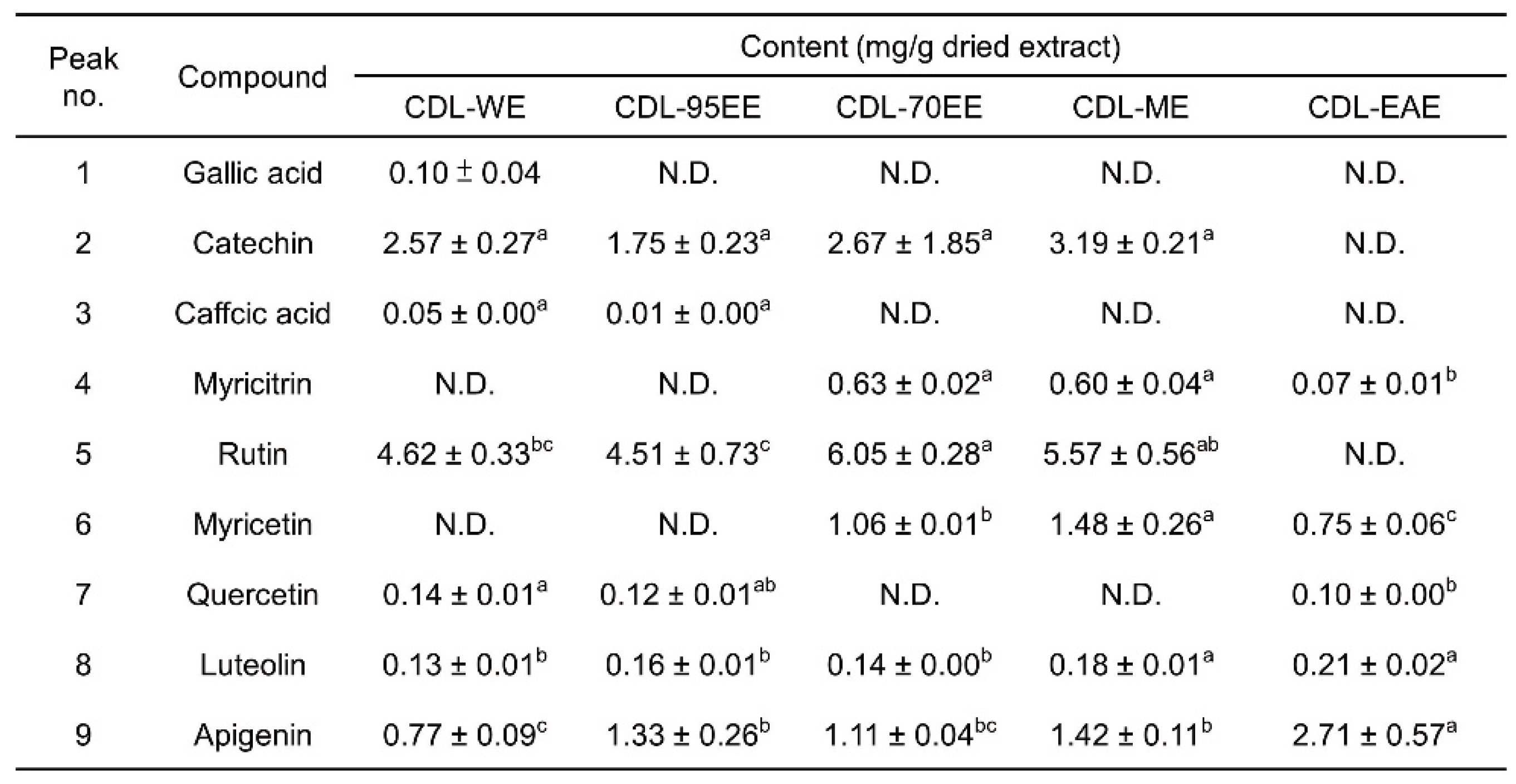

3.1. Citrus Depressa Leaves (CDL) Are Rich in Bioactive Flavonoids and Phenolics

3.2. CDL-95EE Mitigates TPA-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inhibits JB6 P+ Cell Transformation

3.3. CDL-95EE Activates the Nrf2 Pathway through Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhary, P.; Janmeda, P.; Docea, A.O.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Modu, B.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Oxidative stress, free radicals and antioxidants: potential crosstalk in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Front Chem 2023, 11, 1158198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, A.B.; Samal, R.R.; Bhol, N.K.; Duttaroy, A.K. Cellular Red-Ox system in health and disease: The latest update. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 162, 114606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative stress: harms and benefits for human health. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and oxidative stress: a general overview of mechanisms and implications in human disease. antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Tew, K.D. Oxidative stress in cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Aboud, N.M.; Tupper, C.; Jialal, I. Genetics, epigenetic mechanism. StatPearls 2025, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Davletgildeeva, A.T.; Kuznetsov, N.A. The role of DNMT methyltransferases and TET dioxygenases in the maintenance of the DNA methylation level. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Xing, Z.; Qiao, L.; Qin, S.; Zhao, X.; Gong, Y.; Li, X. The role of histone post-translational modifications in cancer and cancer immunity: functions, mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1495221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraweera, A.; O'Byrne, K.J.; Richard, D.J. Epigenetic drugs in cancer therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2025, 10 44, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akone, S.H.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Stuhldreier, F.; Ewonkem, M.B.; Noah, A.M.; Mouelle, S.E.M.; Muller, R. Natural products impacting DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylases. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Dashwood, R.H. Epigenetic regulation of NRF2/KEAP1 by phytochemicals. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Bonesi, M.; Menichini, F.; De Luca, D.; Colica, C.; Menichini, F. Evaluation of Citrus aurantifolia peel and leaves extracts for their chemical composition, antioxidant and anti-cholinesterase activities. J Sci Food Agric 2012, 92, 2960–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menichini, F.; Loizzo, M.R.; Bonesi, M.; Conforti, F.; De Luca, D.; Statti, G.A.; de Cindio, B.; Menichini, F.; Tundis, R. Phytochemical profile, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and hypoglycemic potential of hydroalcoholic extracts from Citrus medica L. cv Diamante flowers, leaves and fruits at two maturity stages. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2011, 49, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, F.A.; Usman, L.A.; Akolade, J.O.; Idowu, O.A.; Abdulazeez, A.T.; Amuzat, A.O. Antidiabetic potentials of Citrus aurantifolia leaf essential oil. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2019, 69, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, K.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, C.; Chen, F.; Mu, D.; Ding, Z.; et al. The levels of bioactive ingredients in Citrus aurantium L. at different harvest periods and antioxidant effects on H2O2-induced RIN-m5F cells. J Sci Food Agric 2021, 16 101, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayarani-Najaran, Z.; Tayarani-Najaran, N.; Eghbali, S. A review of auraptene as an anticancer agent. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 698352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio, T.L.N.; Siqueira, J.S.; de Paula, B.H.; Rego, R.M.P.; Vieira, T.A.; Baron, G.; Altomare, A.; Ferron, A.J.T.; Aldini, G.; Kano, H.T.; et al. Bergamot (Citrus bergamia) leaf extract improves metabolic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity in skeletal muscles in a metabolic syndrome experimental model. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimurugan, S.; Ravi, A.K.; Arumugam, V.A.; Muthukrishnan, S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Citrus hystrix leaf extract and evaluation of its anticancer efficacy against HeLa cell line. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2022, 48, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, C.L.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G., Jr.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Safety assessment of citrus flower- and leaf-derived ingredients as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol 2021, 40, 53s–76s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Feng, X.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Ruta graveolens L.: a critical review and future perspectives. Drug Des Devel Ther 2024, 18, 6459–6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.J.; Saputri, D.S.; Lin, H.Y. Valorization of Taiwan's Citrus depressa Hayata peels as a source of nobiletin and tangeretin using simple ultrasonic-assisted extraction. Curr Res Food Sci 2022, 5, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Torikai, K.; Tanaka, T.; Koshiba, T.; Koshimizu, K.; Kuwahara, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Yano, M.; et al. Inhibitory effect of citrus nobiletin on phorbol ester-induced skin inflammation, oxidative stress, and tumor promotion in mice. Cancer Res 2000, 60, 5059–5066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.P.; Dhanalakshmi, S.; Tyagi, A.K.; Chan, D.C.; Agarwal, C.; Agarwal, R. Dietary feeding of silibinin inhibits advance human prostate carcinoma growth in athymic nude mice and increases plasma insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 levels. Cancer Res 2002, 62, 3063–3069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoshimizu, N.; Otani, Y.; Saikawa, Y.; Kubota, T.; Yoshida, M.; Furukawa, T.; Kumai, K.; Kameyama, K.; Fujii, M.; Yano, M.; et al. Anti-tumour effects of nobiletin, a citrus flavonoid, on gastric cancer include: antiproliferative effects, induction of apoptosis and cell cycle deregulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004, 20 Suppl 1, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.N.; Hsu, Y.S.; Ho, C.T. Flavonoid compositions and antioxidant activity of calamondin extracts prepared using different solvents. J Food Drug Anal 2014, 22, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, G.; Paredes, A. Antioxidant activities of Lampaya medicinalis extracts and their main chemical constituents. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014, 14, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoddami, A.; Wilkes, M.A.; Roberts, T.H. Techniques for analysis of plant phenolic compounds. Molecules 2013, 18, 2328–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.-Y.; Lai, B.-A.; Lin, Z.-H.; Wei, G.-J.; Huang, S.-H.; Tung, Y.-C.; Wu, T.-Y.; Hun Lee, J.; Hsu, Y.-C. Water extract of lotus leaves has hepatoprotective activity by enhancing Nrf2- and epigenetics-mediated cellular antioxidant capacity in mouse hepatocytes. Journal of Functional Foods 2022, 99, 105331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.C.; Sung, P.H.; Chen, P.C.; Wang, H.C.; Lee, J.H.; Su, Z.Y. Chemoprevention of lotus leaf ethanolic extract through epigenetic activation of the NRF2-mediated pathway in murine skin JB6 P+ cell neoplastic transformation. J Tradit Complement Med 2023, 13, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Liao, H.; Xu, L.; Li, Q.; Zou, J.; Sun, R.; Xiao, D.; Liu, C.; Pu, W.; Cheng, J.; et al. Autophagy-dependent cell cycle arrest in esophageal cancer cells exposed to dihydroartemisinin. Chin Med 2020, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of phenolic compounds: A review. Curr Res Food Sci 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, K.L.; Ferguson, P.J.; Koropatnick, J. Tangeretin and nobiletin induce G1 cell cycle arrest but not apoptosis in human breast and colon cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2007, 251, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Gu, Y.; Tan, C.; Sundararajan, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Z. Comparative effects of five polymethoxyflavones purified from Citrus tangerina on inflammation and cancer. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 963662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Tan, X.; Tang, S.; Liu, X.; Shao, L.; Wang, C.; Huang, L. Citrus p-synephrine improves energy homeostasis by regulating amino acid metabolism in HFD-induced mice. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The pharmacological potential of rutin. Saudi Pharm J 2017, 25, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naponelli, V.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Mangieri, D. Apigenin: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential against Cancer Spreading. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.H.; Chan, Y.F.; Pan, M.H.; Tung, Y.C.; Su, Z.Y. Aged citrus peel (Chenpi) prevents acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity by epigenetically regulating Nrf2 pathway. Am J Chin Med 2019, 47, 1833–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.Y.; Chien, J.C.; Tung, Y.C.; Wu, T.Y.; Liao, J.A.; Wei, G.J. Tangeretin and 4'-demethyltangeretin prevent damage to mouse hepatocytes from oxidative stress by activating the Nrf2-related antioxidant pathway via an epigenetic mechanism. Chem Biol Interact 2023, 382, 110650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, T.O.; Fuentes, F.; Shu, L.; Paredes-Gonzalez, X.; Yang, A.Y.; Liu, Y.; Smiraglia, D.J.; Yegnasubramanian, S.; Nelson, W.G.; Kong, A.N. Epigenetic DNA methylation of antioxidative stress regulator NRF2 in human prostate cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014, 7, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; He, K.; Liu, Y.; Gong, J.; Gong, J. Nobiletin attenuates lipopolysaccharide/D-galactosamine-induced liver injury in mice by activating the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway and subsequently inhibiting NF-kappaB-mediated cytokine production. Mol Med Rep 2016, 14, 5595–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Li, Y.; Liang, R.; Huang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, H.; Qin, F.; Sun, C.; et al. Characterization of tangeretin as an activator of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/antioxidant response element pathway in HEK293T cells. Curr Res Food Sci 2023, 6, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Sheng, H.; Bai, Y.F.; Weng, Y.Y.; Fan, X.Y.; Zheng, F.; Fu, J.Q.; Zhang, F. Inhibition of histone acetyltransferase by naringenin and hesperetin suppresses Txnip expression and protects pancreatic beta cells in diabetic mice. Phytomedicine 2021, 88, 153454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casari, G.; Romaldi, B.; Scire, A.; Minnelli, C.; Marzioni, D.; Ferretti, G.; Armeni, T. Epigenetic properties of compounds contained in functional foods against cancer. Biomolecules 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).