Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

28 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area, Sample Collection and Pretreatment

2.2. DNA Extraction and Quality Evaluation

2.2.1. DNA Extraction from Sediment and Water Samples

2.2.2. DNA Extraction from Biological Samples

2.2.3. DNA Quantification and Storage

2.3. Quantification of ARGs by High-Throughput Quantitative PCR

2.4. 16S rRNA Sequencing, Quality Control and Data Processing

2.5. Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR Detection

2.6. Bioinformatic Analyses

3. Results

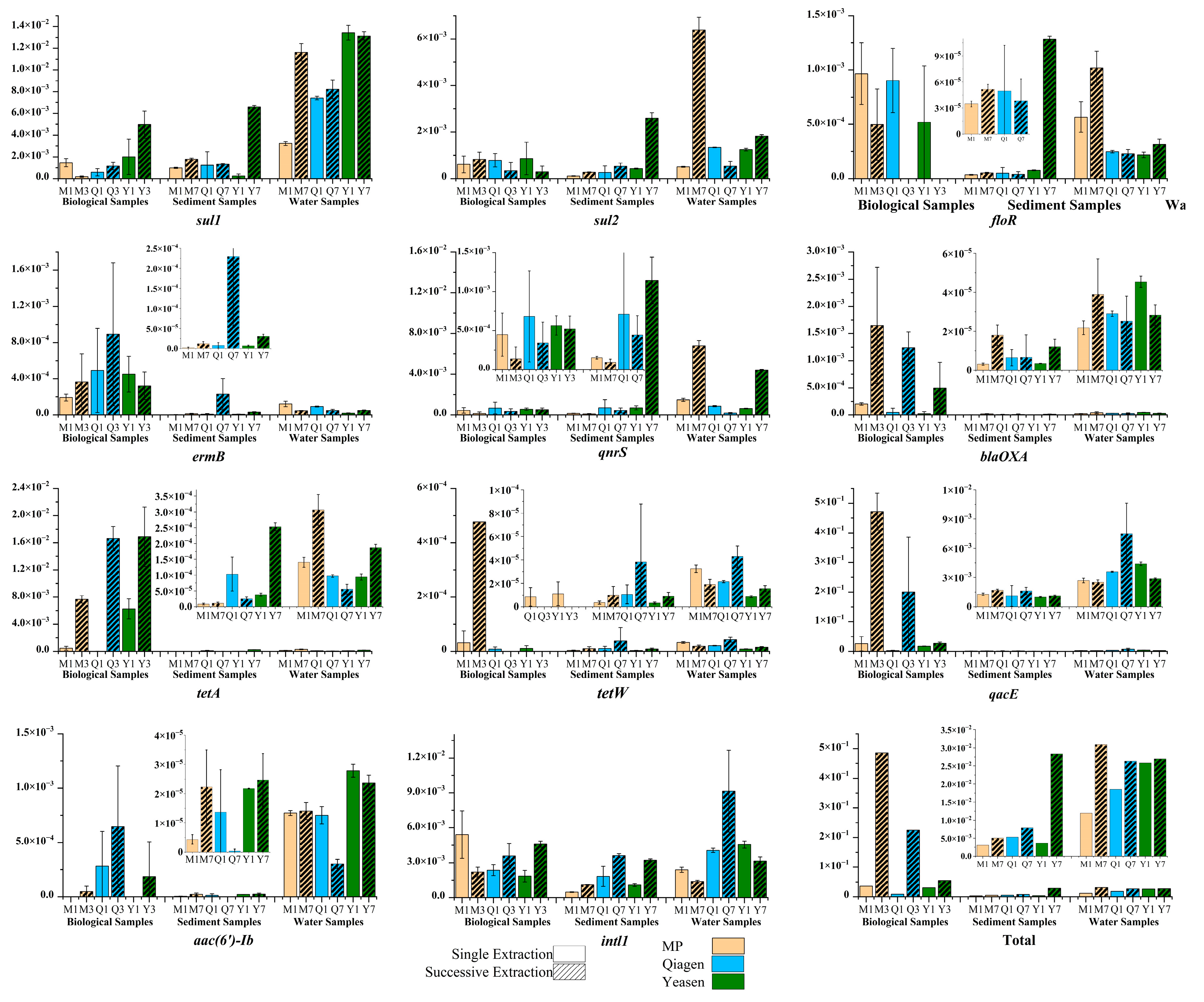

3.1. DNA Yield Improvement Through Successive Extractions Across Different Matrices

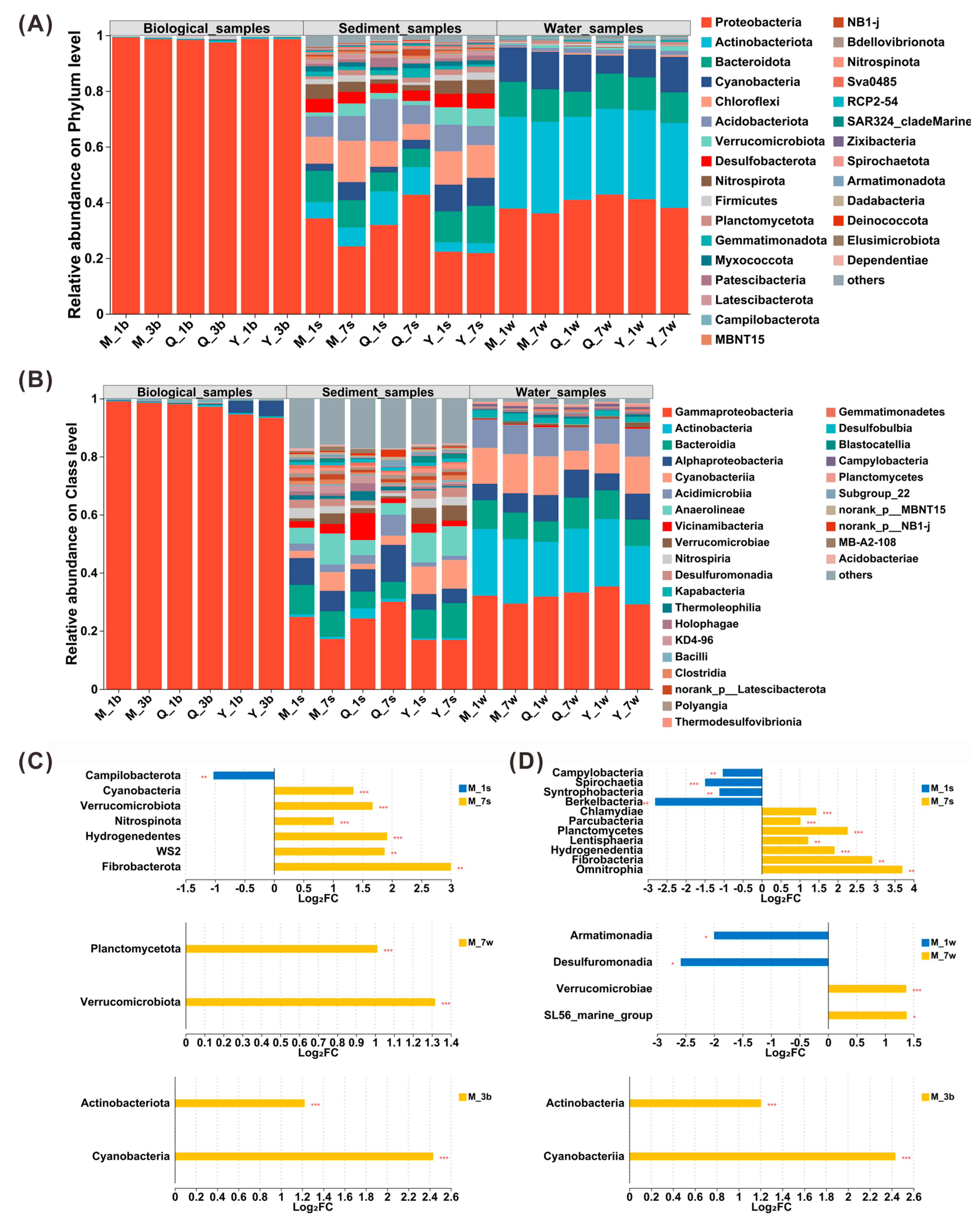

3.2. Taxonomic Shifts in Microbial Community Composition Under Successive DNA Extractions

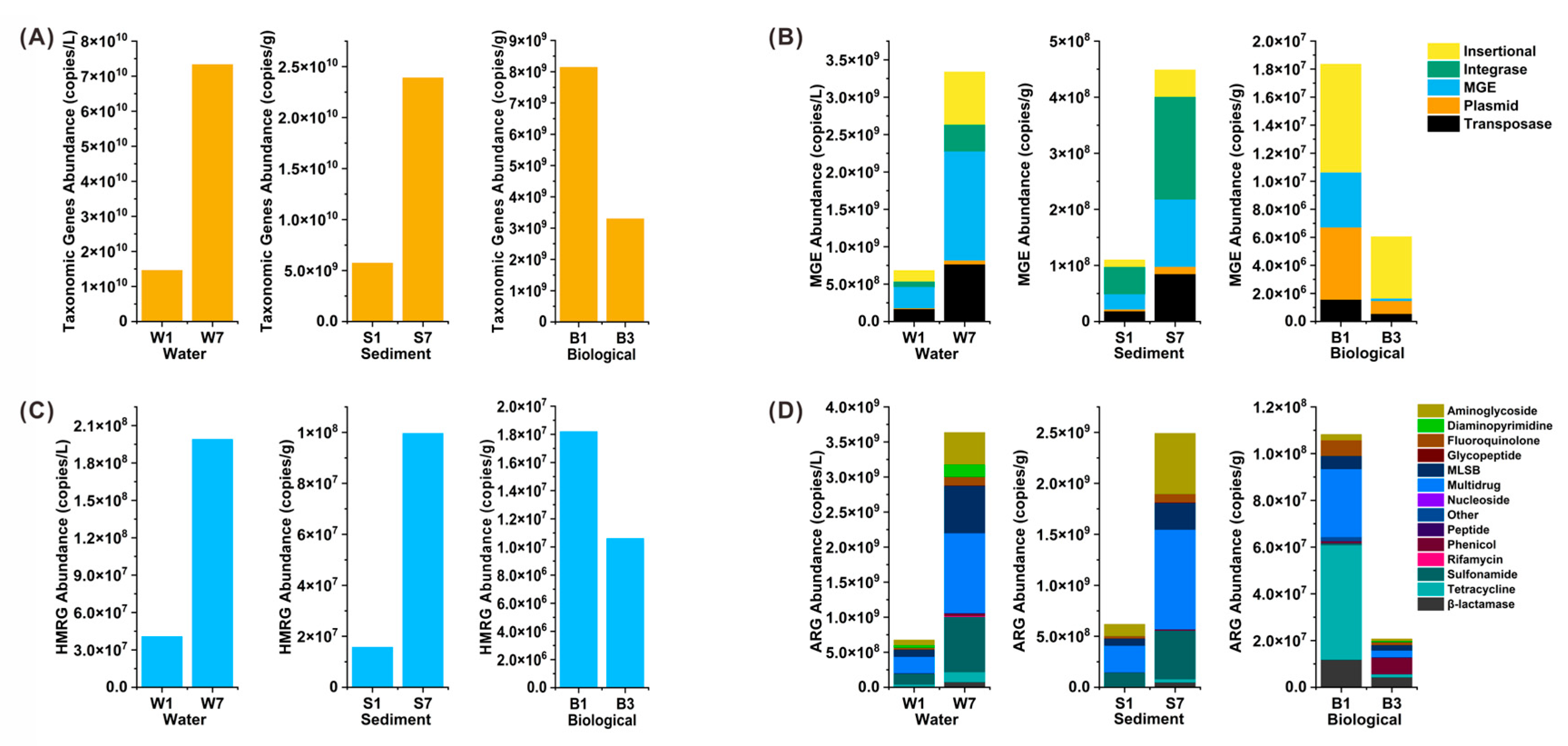

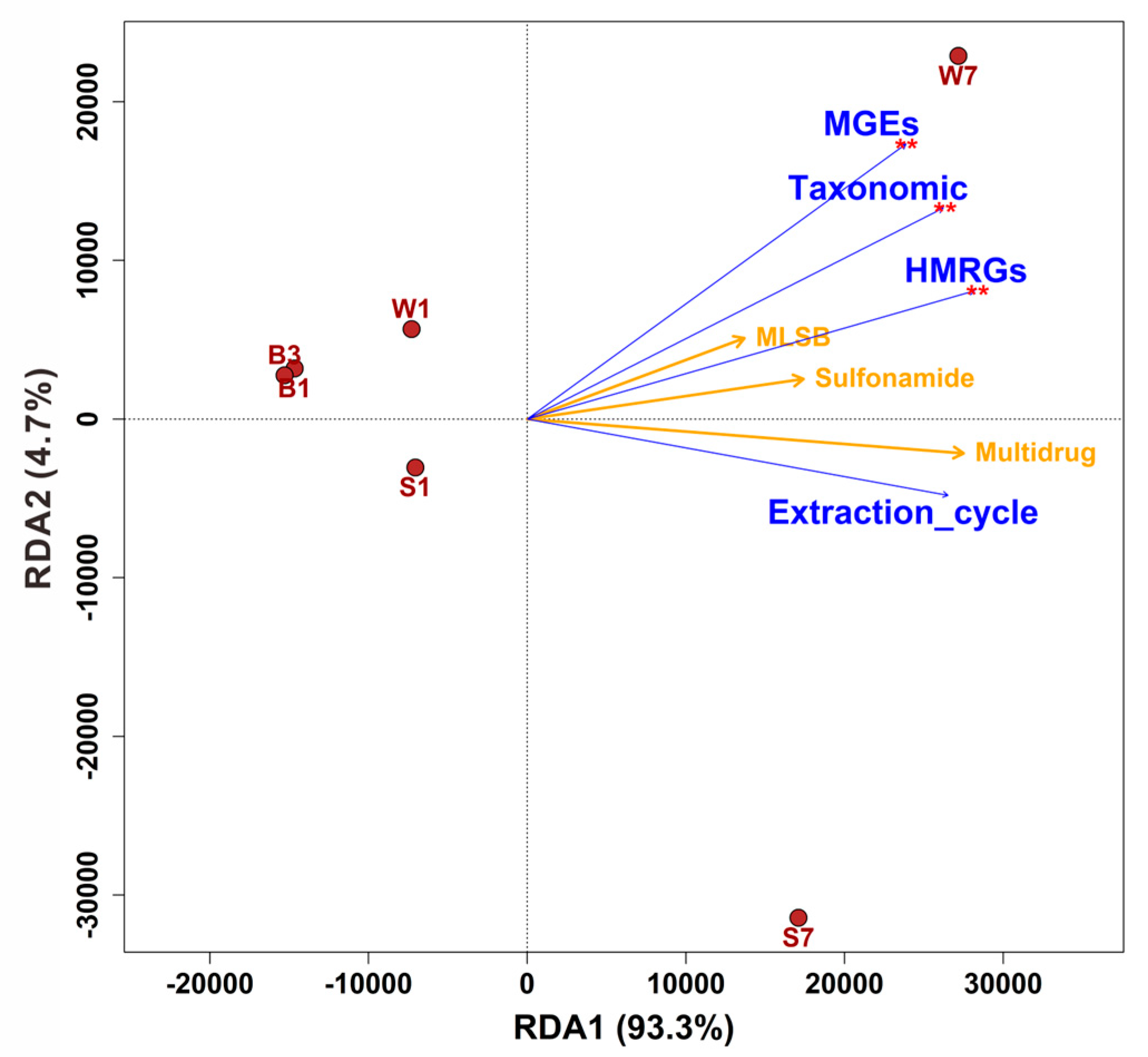

3.3. Abundance and Correlation of ARGs, MGEs and HMRGs Under Successive DNA Extractions

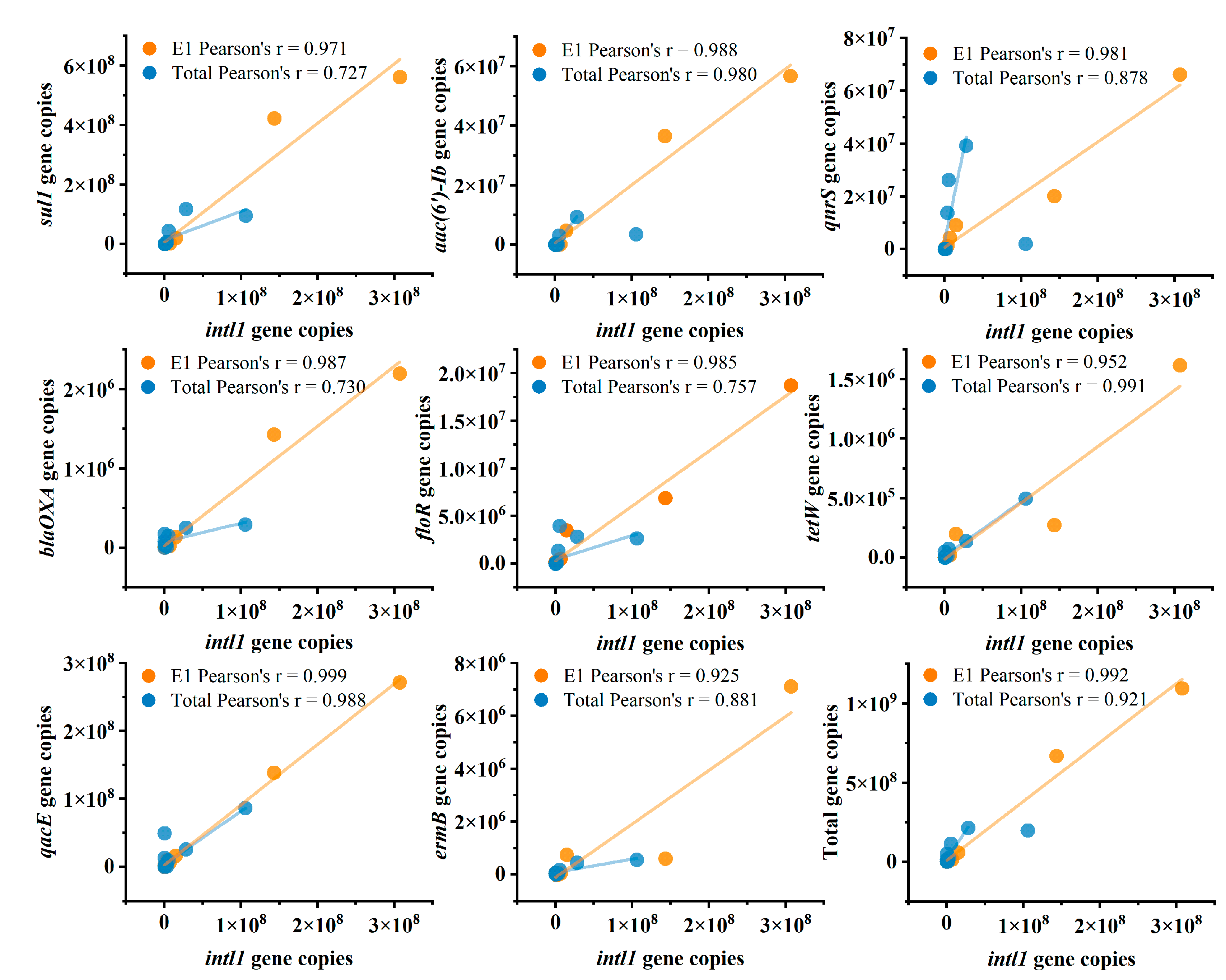

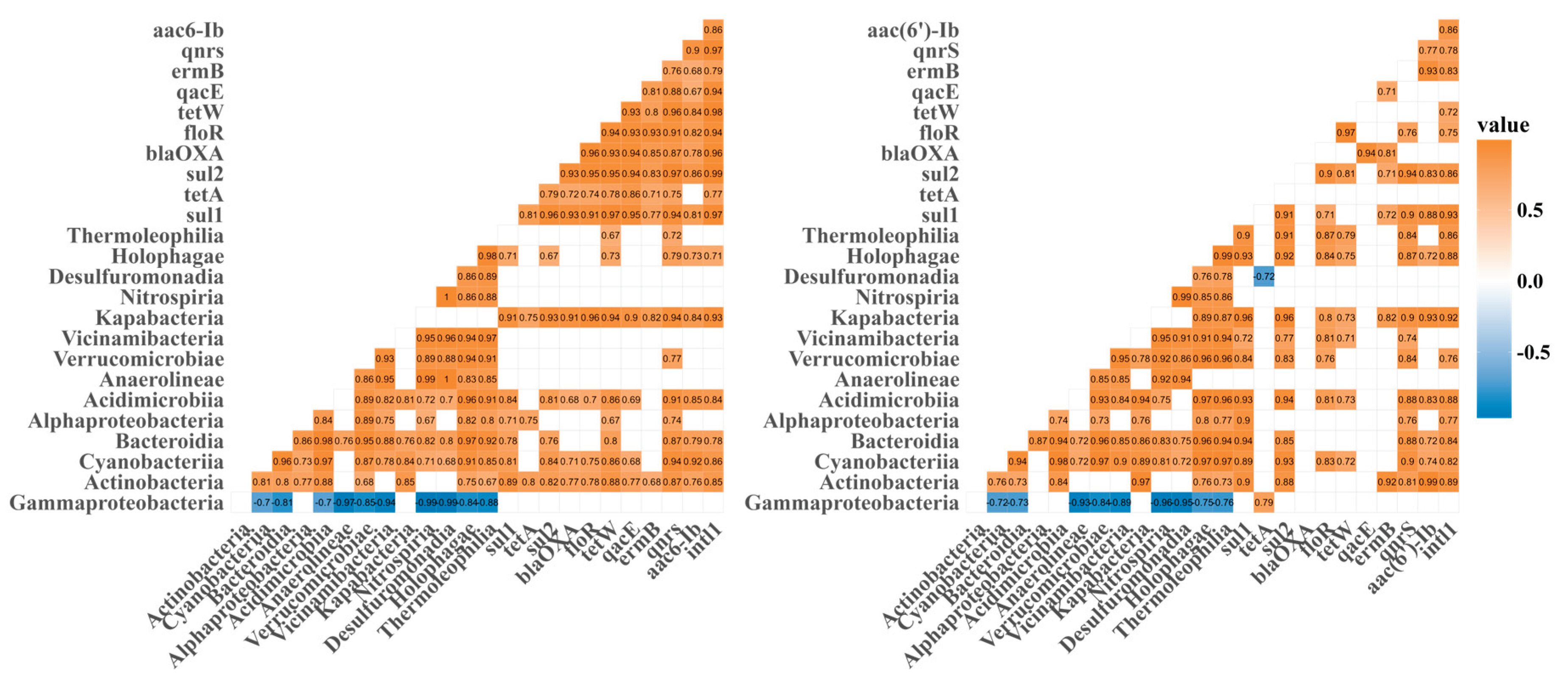

3.4. Correlations Among intI1, Antibiotic Resistance Genes, and Microbial Communities

4. Discussion

4.1. Successive Extraction as a Matrix-Dependent Strategy to Access Recalcitrant DNA Pools

4.2. Extraction Bias in Microbial Community Representation: Implications for Low-Abundance and Particle-Associated Taxa

4.3. Quantitative and Structural Reshaping of the Environmental Resistome

4.4. From Methodological Bias to Ecological Interpretation: Opportunities and Cautions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Y.G.; Johnson, T.A.; Su, J.Q.; Qiao, M.; Guo, G.X.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Hashsham, S.A.; Tiedje, J.M. Diverse and abundant antibiotic resistance genes in Chinese swine farms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 3435–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.L. Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Natural Environments. Science 2008, 321, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wu, N.; Li, W.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, Z. Estuarine sediments are key hotspots of intracellular and extracellular antibiotic resistance genes: A high-throughput analysis in Haihe Estuary in China. Environment International 2020, 135, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xu, P.; Gong, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, W.; Fu, B.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, X. Metagenomic profiles of the resistome in subtropical estuaries: Co-occurrence patterns, indicative genes, and driving factors. Sci Total Environ 2022, 810, 152263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.-G.; Zhao, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Yu, S.; Chen, Y.-S.; Zhang, T.; Gillings, M.R.; Su, J.-Q. Continental-scale pollution of estuaries with antibiotic resistance genes. Nature Microbiology 2017, 2, 16270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muziasari, W.I.; Pitkänen, L.K.; Sørum, H.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Tiedje, J.M.; Virta, M. The Resistome of Farmed Fish Feces Contributes to the Enrichment of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Sediments below Baltic Sea Fish Farms. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 7–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendonk, T.U.; Manaia, C.M.; Merlin, C.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Cytryn, E.; Walsh, F.; Bürgmann, H.; Sørum, H.; Norström, M.; Pons, M.N.; et al. Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, T. Biases during DNA extraction of activated sludge samples revealed by high throughput sequencing. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2013, 97, 4607–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, L.M.; Sul, W.J.; Blackwood, C.B. Assessment of bias associated with incomplete extraction of microbial DNA from soil. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2009, 75, 5428–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, M.R.; Veraart, A.J.; de Hollander, M.; Smidt, H.; van Veen, J.A.; Kuramae, E.E. Successive DNA extractions improve characterization of soil microbial communities. PeerJ 2017, 5, e2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Li, M.; Gu, J.D. Biases in community structures of ammonia/ammonium-oxidizing microorganisms caused by insufficient DNA extractions from Baijiang soil revealed by comparative analysis of coastal wetland sediment and rice paddy soil. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2013, 97, 8741–8756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Feng, J.; Xue, R.; Ma, J.; Lou, L.; He, J.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, H.; Deng, O.; Xie, L. The insufficient extraction of DNA from swine manures may underestimate the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes as well as ignore their potential hosts. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 278, 111587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, G.; Xu, W.; Jian, S.; Peng, L.; Jia, D.; Sun, J. New Estimation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Sediment Along the Haihe River and Bohai Bay in China: A Comparison Between Single and Successive DNA Extraction Methods. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 705724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulter, N.; Suarez, F.G.; Schibeci, S.; Sunderland, T.; Tolhurst, O.; Hunter, T.; Hodge, G.; Handelsman, D.; Simanainen, U.; Hendriks, E.; et al. A simple, accurate and universal method for quantification of PCR. BMC Biotechnology 2016, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Z. Quantitative comparison of HT-qPCR/16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics for antibiotic resistance gene profiling: A novel risk assessment approach. J Hazard Mater 2025, 498, 139904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C. High-throughput profiling of antibiotic resistance genes in the Yellow River of Henan Province, China. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 17490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiao, P.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, J. The impacts of different high-throughput profiling approaches on the understanding of bacterial antibiotic resistance genes in a freshwater reservoir. Sci Total Environ 2019, 693, 133585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, R.S.; Munk, P.; Njage, P.; van Bunnik, B.; McNally, L.; Lukjancenko, O.; Röder, T.; Nieuwenhuijse, D.; Pedersen, S.K.; Kjeldgaard, J.; et al. Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenum, I.; Liguori, K.; Calarco, J.; Davis, B.C.; Milligan, E.; Harwood, V.J.; Pruden, A. A framework for standardized qPCR-targets and protocols for quantifying antibiotic resistance in surface water, recycled water and wastewater. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 52, 4395–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Z.; Li, Q. Vertical migration of antibiotics, ARGs, and pathogens in industrial multi-pollutant soils: Implications for environmental and public health. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2025, 303, 118912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.R.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Hou, L.J.; Wu, S.X.; Zhu, P.K. Indigenous PAH degraders along the gradient of the Yangtze Estuary of China: Relationships with pollutants and their bioremediation implications. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2019, 142, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Mao, D.; Rysz, M.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xu, L.; J.J.A., P. Trends in antibiotic resistance genes occurrence in the Haihe River, China. Environmental Science & Technology 2010, 44, 7220–7225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.-p.; Chen, Y.-R.; Sun, X.-l.; Li, C.-l.; Hou, L.-j.; Liu, M.; Yang, Y. Plastic properties affect the composition of prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities and further regulate the ARGs in their surface biofilms. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 839, 156362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.P.; Chen, Y.R.; Sun, X.L.; Li, C.L.; Hou, L.J.; Liu, M.; Yang, Y. Plastic properties affect the composition of prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities and further regulate the ARGs in their surface biofilms. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 839, 156362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yu, G.; Shi, C.; Liu, L.; Guo, Q.; Han, C.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, B.; Gao, H.; et al. Majorbio Cloud: A one-stop, comprehensive bioinformatic platform for multiomics analyses. iMeta 2022, 1, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schloss, P.D.; Gevers, D.; Westcott, S.L. Reducing the effects of PCR amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16S rRNA-based studies. Plos One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheik, C.S.; Mitchell, T.W.; Rizvi, F.Z.; Rehman, Y.; Faisal, M.; Hasnain, S.; McInerney, M.J.; Krumholz, L.R. Exposure of Soil Microbial Communities to Chromium and Arsenic Alters Their Diversity and Structure. Plos One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, S.A.; Wang, X.D.; Chen, Y.; Lin, X.M.; Yan, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, M.; Han, H.C. 16S rRNA gene high-throughput sequencing reveals shift in nitrogen conversion related microorganisms in a CANON system in response to salt stress. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 317, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ding, Y.; Peng, J.; Dai, Y.; Luo, S.; Liu, W.; Ma, Y. Effects of Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic (Florfenicol) on Resistance Genes and Bacterial Community Structure of Water and Sediments in an Aquatic Microcosm Model. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Han, M.; Li, E.; Liu, X.; Wei, H.; Yang, C.; Lu, S.; Ning, K. Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in an agriculturally disturbed lake in China: Their links with microbial communities, antibiotics, and water quality. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 393, 122426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, B.; Feng, X.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Q. Metagenomic evidence for antibiotic-associated actinomycetes in the Karamay Gobi region. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1330880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Sun, Y.; Dong, X.; Hu, X. Unveiling the occurrence, hosts and mobility potential of antibiotic resistance genes in the deep ocean. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 816, 151539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Chen, H.; Cai, L.; He, M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, L. Grinding Beads Influence Microbial DNA Extraction from Organic-Rich Sub-Seafloor Sediment. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgmann, H.; Pesaro, M.; Widmer, F.; Zeyer, J. A strategy for optimizing quality and quantity of DNA extracted from soil. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2001, 45, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, R. The metagenomics of soil. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2005, 3, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.-Y.; Driscoll, M.; Gratalo, D.; Jarvie, T.; Weinstock, G.M. Improved DNA Extraction and Amplification Strategy for 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon-Based Microbiome Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huanca-Valenzuela, P.; Fuchsman, C.A.; Tully, B.J.; Sylvan, J.B.; Cram, J.A. Quantitative microbial taxonomy across particle size, depth, and oxygen concentration. Frontiers in Microbiology 2025, 16–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozan, M.; Berreth, H.; Lindberg, P.; Bühler, K. Cyanobacterial biofilms: from natural systems to applications. Trends Biotechnol 2025, 43, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.; Bordin, N.; Kizina, J.; Harder, J.; Devos, D.; Lage, O.M. Planctomycetes attached to algal surfaces: Insight into their genomes. Genomics 2018, 110, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushpakumara, B.L.D.U.; Tandon, K.; Willis, A.; Verbruggen, H. Unravelling microalgal-bacterial interactions in aquatic ecosystems through 16S rRNA gene-based co-occurrence networks. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, P.; Marsden, P.J.; Leff, J.W.; Morgan, E.E.; Strickland, M.S.; Fierer, N. Relic DNA is abundant in soil and obscures estimates of soil microbial diversity. Nat Microbiol 2016, 2, 16242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivalingam, P.; Sabatino, R.; Sbaffi, T.; Fontaneto, D.; Corno, G.; Di Cesare, A. Extracellular DNA includes an important fraction of high-risk antibiotic resistance genes in treated wastewaters. Environ Pollut 2023, 323, 121325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.