1. Introduction

In eukaryotes, genomic DNA is organized into a nucleic acid–protein complex known as chromatin. Chromatin serves two essential functions: it efficiently packages DNA to fit within the nucleus and regulates access to the genetic information it encodes. Decades of research have established that chromatin structure and dynamics profoundly influence all DNA-templated processes, including transcription, replication, and DNA repair.

Although chromatin and its fundamental repeating unit, the nucleosome, present substantial physical barriers to DNA replication and transcription, they do not protect DNA from endogenous or exogenous damage. To preserve genome integrity, cells have evolved multiple conserved DNA damage response (DDR) pathways to repair various lesions. Among these, base excision repair (BER) is the primary pathway responsible for repairing DNA lesions generated by oxidative stress, spontaneous base loss, and alkylation damage. During BER, damaged bases are recognized and excised by lesion-specific DNA glycosylases, generating abasic/AP (apurinic/apyrimidinic) sites or, in some cases, single-strand breaks (SSBs) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In mammalian cells, AP sites are processed by apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1), a central enzyme in the BER pathway. APE1 cleaves the phosphodiester backbone 5′ to the AP site via its endonuclease activity, creating a nick that is subsequently processed by DNA polymerase β, which fills the resulting gap, and DNA ligase IIIα, in complex with XRCC1, which seals the nick to restore DNA integrity.

APE1 is an abundant and essential protein in human cells, and its deletion is embryonic lethal in mice [

5]. Dysregulation of APE1, including overexpression or aberrant subcellular localization, leads to genome instability and has been strongly associated with poor prognosis, therapy resistance in multiple cancers [

6,

7,

8]. In addition to its canonical endonuclease activity in BER, APE1 also has non-canonical functions, including redox regulation of transcription factors [

9], microRNA processing [

10,

11], and RNA quality control [

12,

13]. While extensive in-vitro studies have demonstrated that APE1 efficiently cleaves AP sites on naked DNA substrates, how its endonuclease activity is regulated within the chromatin environment in eukaryotes remains poorly understood.

In

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the primary AP endonuclease is APN1, a homolog of

Escherichia coli endonuclease IV (Endo IV). Although APE1 and APN1 perform analogous functions in BER in their respective organisms, they share limited sequence and structural similarity, reflecting the distinct evolutionary solutions to AP site processing in these organisms. While human APE1 and Endo IV have been extensively characterized, comparatively little is known about the regulation of APN1, particularly in the context of chromatin. Multiple reports have established the importance of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers in efficient DDR [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Our recent work demonstrated that the yeast ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler INO80 (thereafter referred to as INO80-C) enhances the incision activity of APE1 in an ATP-independent manner [

18], revealing a functional interplay between INO80 chromatin remodeler and a key BER enzyme.

Building on these findings, here we further investigate interactions of three AP endonucleases with two different chromatin remodelers. Specifically, we characterize the effects of INO80-C on APN1 and Endo IV activity respectively, as well as the effect of human Chromodomain Helicase DNA-binding protein 1 (CHD1) ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler on APE1 and Endo IV activity. Our results reveal conserved and divergent mechanisms regulating AP site repair. Together, this study provides new insights into how chromatin context and remodeling activities influence the efficiency of BER repair.

2. Results

2.1. INO80 Stimulation of AP-Site Incision on Nucleosome Is Conserved in Yeast

Previously, we showed that the INO80-C core complex enhances human APE1 AP endonuclease activity in vitro in an ATP-independent manner [

18], indicating a functional interaction between INO80 and AP endonucleases. Although the INO80 core complex is highly conserved between yeast and humans in both subunit composition and overall structure, it remained unclear whether this stimulatory effect is conserved across species and reproducible when both the remodeler and the AP endonuclease are derived from yeast. We therefore sought to test whether INO80-C also stimulates the activity of the yeast AP endonuclease APN1. We performed in vitro incision assays using end-position nucleosomes with Widom 601 DNA containing tetrahydrofuran (THF), an AP-site mimic, positioned at either of the two known INO80-binding sites (Supplemental Table 1), as previously described [

18].

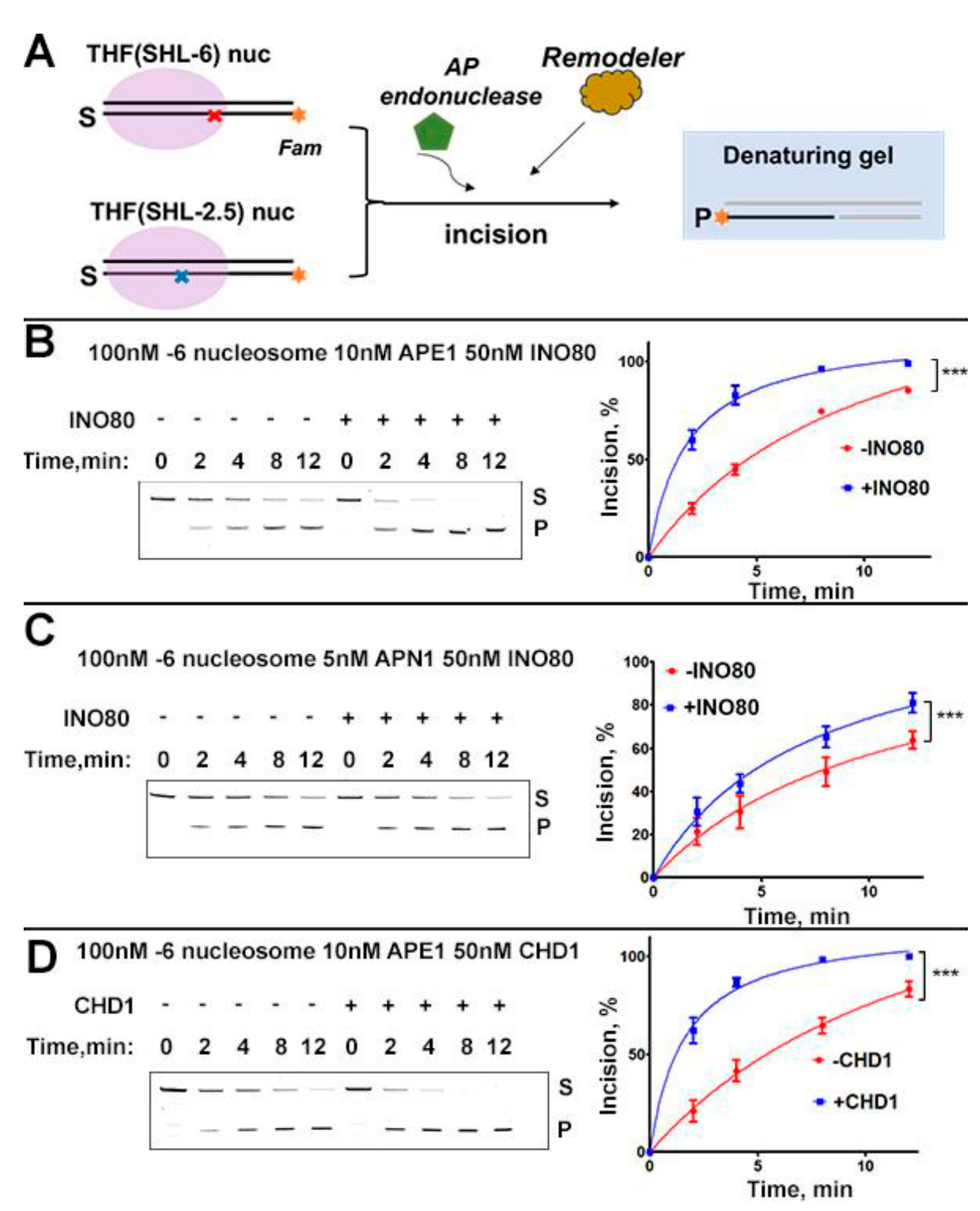

The recombinant INO80-C core complex that is competent for ATP-dependent DNA translocation on canonical nucleosomes but inactive on damaged nucleosomes is used the current study (Supplemental Figure 2A). We then performed an in-vitro incision assay to determine the efficiency of AP-site cleavage on various nucleosome substrates (

Figure 1A). As expected and consistent with our prior results, INO80-C enhances APE1-mediated cleavage of THF(SHL-6) nucleosomes by approximately 17% compared to reactions lacking INO80-C (

Figure 1B). When APN1 was used, cleavage of THF(SHL −6) nucleosomes was enhanced by a similar degree (~15%) in the presence of INO80-C (

Figure 1C). Together, these results demonstrate that INO80-mediated enhancement of AP-site incision on nucleosomes is conserved in yeast.

Given the unique nucleosome-binding mode of the INO80 complex, we asked how other Snf2-family chromatin remodelers may affect AP-site incision on nucleosomes. Although several chromatin remodelers have been implicated in DDR, INO80 remained the only remodeling enzyme reported to directly stimulate AP endonuclease activity [

18]. INO80 is distinct from other Snf2-family ATP-dependent remodelers in that it engages nucleosomes through two spatially separated binding sites: its primary motor ino80 binds nucleosome at superhelical location (SHL) −6, while its Arp5/Ies6 module interacts with the nucleosome through SHL −2. This distinctive mode of nucleosome engagement raises the possibility that remodelers binding exclusively at SHL ±2 may differ in their response and their ability to influence AP endonuclease–mediated incision.

To test this hypothesis, we examined the CHD1 chromatin remodeler, a single-subunit Snf2-family enzyme that, like most remodelers in the family, engages nucleosomes at SHL ±2 via its ATPase domain. We showed that recombinant human CHD1 is active in sliding canonical nucleosomes (Supplemental Figure 2B). Our data also shows that its remodeling activity is inhibited when abasic lesions are present at SHL −2.5, but not at SHL −6 (Supplemental Figure 2B). These results demonstrated that CHD1 remodeler activity is sensitive to DNA lesion, a property similar to the INO80 remodeler.

We next tested the ability of CHD1 to influence AP-site incision mediated by APE1 on THF(SHL −6) nucleosomes. To our surprise, we observed a significant increase of incision in the presence of CHD1 compared to reactions lacking CHD1, even in the absence of ATP (

Figure 1D). How CHD1 enhances DNA accessibility at the nucleosomal entry/exit site without ATP-driven nucleosome sliding remains unclear, and will require further investigation to elucidate the underlying mechanism.

2.2. Efficient Incision of Internal Nucleosome AP-Site Requires Chromatin Remodeler and ATP

DNA at the SHL-6 position lies in close proximity to the nucleosomal DNA entry/exit site, where DNA undergoes spontaneous “breathing” resulting in more accessible DNA than internally positioned DNA. In our previous study, we proposed that INO80-C directly interacts with APE1 to stabilize its active conformation, and thus enhance abasic incision on nucleosomes [

18], though we cannot rule out the possibility that INO80-C binding on THF nucleosomes alone can influence DNA lesion accessibility. To test our hypothesis and to gain insights into INO80-C stimulation of AP site incision, we performed the incision assay with nucleosomes containing a more buried abasic site at SHL-2.5. Notably, INO80 also engages nucleosome through a secondary interaction site at SHL-2 via its Arp5/Ies6 module [

19,

20]. and lesions at this position impair INO80-mediated DNA translocation without affecting its nucleosome-stimulated ATPase activity [

18].

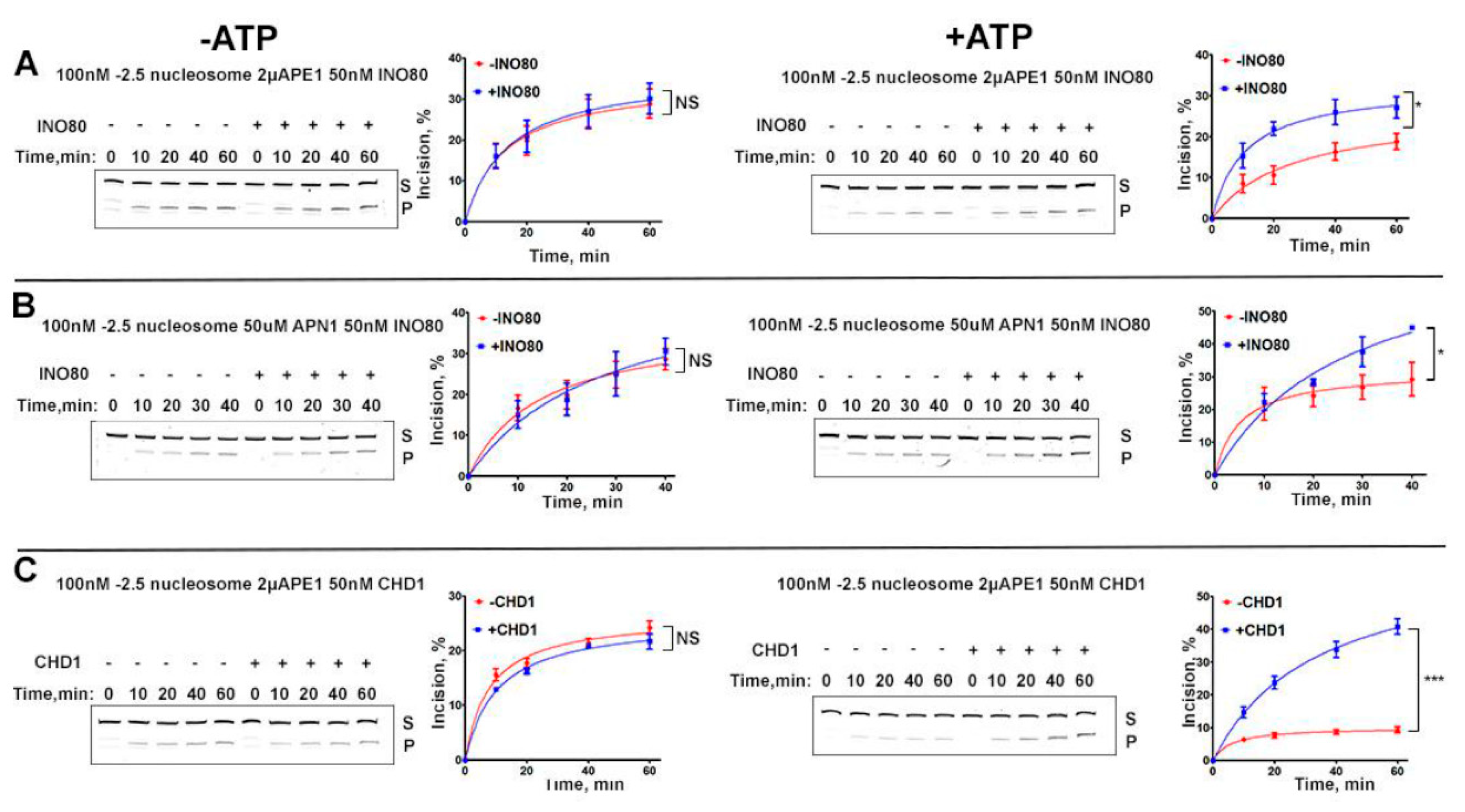

In contrast to THF(SHL −6) substrates, INO80 had no detectable effect on APE1- or Apn1-mediated incision of THF(SHL −2.5) nucleosomes in the absence of ATP (

Figure 2A,B). However, in the presence of ATP, INO80 enhanced incision by approximately 10% for APE1 and 16% for Apn1 (

Figure 2A,B). Because lesions at SHL −2.5 do not inhibit ATP hydrolysis by the INO80 motor despite blocking DNA translocation, we propose that ATP hydrolysis at SHL −6 increases terminal DNA flexibility, providing earlier access for AP endonucleases. Over time, these enhanced dynamics may indirectly increase accessibility of internally positioned lesions, leading to more efficient incision.

We next tested the effect of CHD1 on the APE1-mediated incision of THF(SHL-2.5) nucleosomes. As observed for INO80, CHD1 had no detectable effect on APE1-mediated incision at this internal site in the absence of ATP. In contrast, the presence of ATP resulted in a marked enhancement of incision, increasing cleavage by approximately 30% (

Figure 2C). We propose that although abasic lesions positioned near the CHD1-binding site at SHL −2.5 impair DNA translocation, they do not prevent CHD1 from binding nucleosomes or hydrolyzing ATP. ATP-driven CHD1 activity may therefore promote partial DNA unwrapping of the lesion-containing region, thereby increasing AP-site accessibility to APE1.

Taken together, these results allow us to refine our previous model. We propose that INO80 and CHD1 promote AP-site incision and efficient base excision repair on chromatin through multiple mechanisms. While the interaction between INO80 and Apn1 and its contribution to incision remain to be fully validated, our data indicate that both remodelers can enhance lesion accessibility through a DNA translocation–independent mechanism. Specifically, rather than relying primarily on remodeler-mediated nucleosome sliding, binding of remodelers to damaged nucleosomes alone may be sufficient to induce local DNA distortions that increase lesion accessibility. Such minimal structural changes may permit AP endonucleases to access and incise lesions within nucleosomes.

2.3. Endo IV Is Ineffective in Incising Internal AP-Sites on Nucleosomes Without Chromatin Remodelers

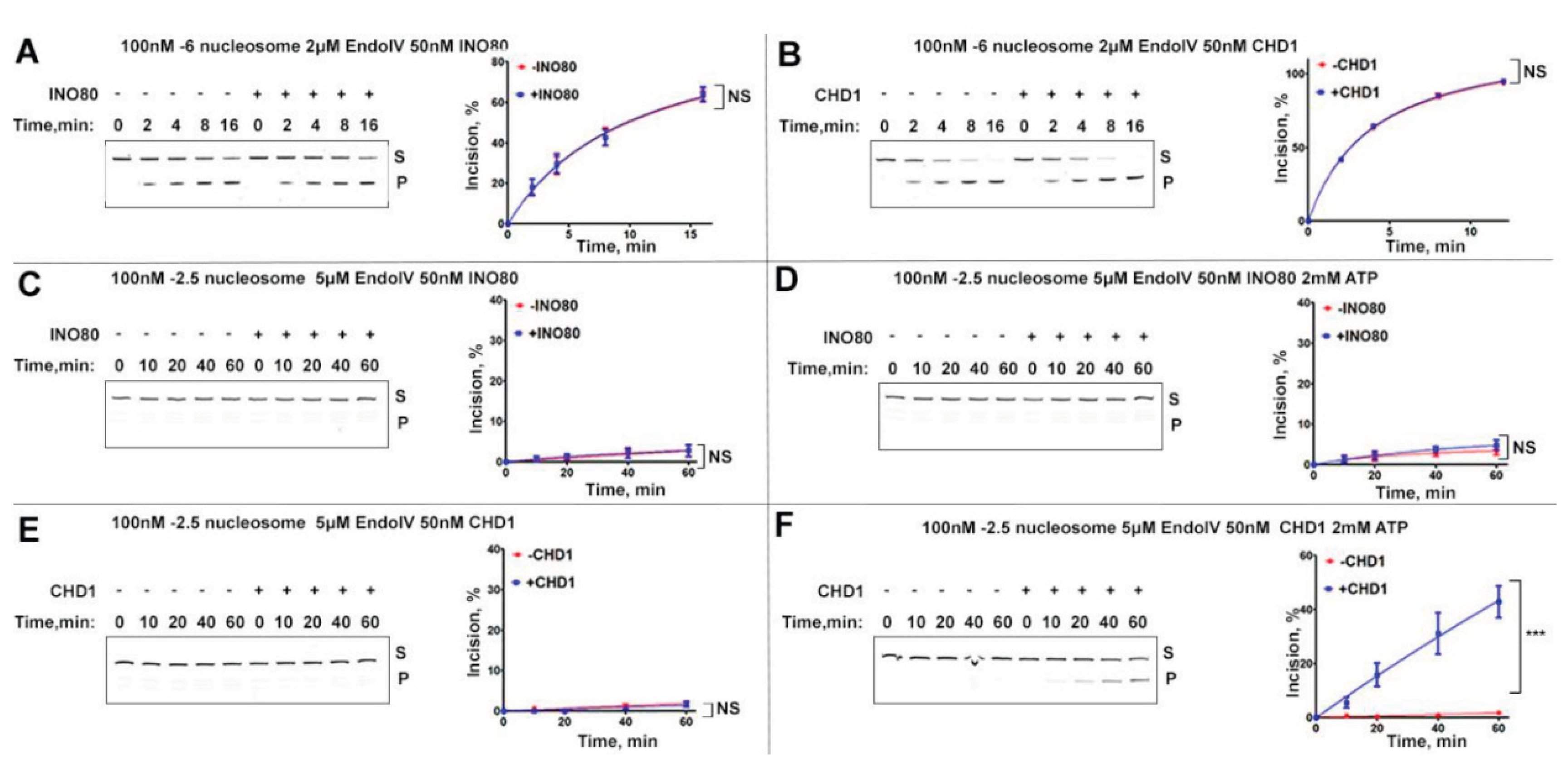

Since APE1 and APN1 belong to distinct AP endonuclease families with no detectable sequence similarity (Supplemental Fig 1), we next examined whether the INO80 remodeler could influence bacterial Endo IV on nucleosome substrates. Our results show that Endo IV was capable of cleaving THF(SHL-6) nucleosomes in vitro. However, unlike with APE1 and APN1, the presence of INO80 had no detectable effect on Endo IV-mediated nucleosome incision (

Figure 3A). A similar lack of stimulation was observed in reactions containing either INO80 or CHD1 on THF(SHL −6) nucleosomes (

Figure 3B).

To our surprise, under the same condition Endo IV exhibited minimal incision on THF(SHL-2.5) nucleosomes (

Figure 3C-F), indicating a strong inability to access internally positioned AP sites within nucleosomes. No detectable differences were observed when INO80 was present regardless whether ATP was added (

Figure 3C, D). The presence of INO80 did not enhance Endo IV activity at this internal site, regardless of whether ATP was included (

Figure 3C,D). In contrast, CHD1 markedly stimulated Endo IV–mediated incision at SHL −2.5, increasing cleavage from approximately 2% to over 40%, but only in the presence of ATP (

Figure 3E,F).

3. Discussion

In prokaryotes, AP endonucleases act on naked DNA, where lesion accessibility is largely unregulated. In contrast, their eukaryotic homologs operate within the context of chromatin, where access to damaged DNA is tightly controlled by nucleosome organization and epigenetic regulation. Snf2-family ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers represent a major class of epigenetic enzymes that regulate DNA accessibility by modulating nucleosome structure and positioning. A defining feature of this family is their ability to reposition nucleosomes relative to the underlying DNA in an ATP-dependent manner [ref]. While this activity is central to transcriptional regulation, its precise role in the DNA damage response (DDR) has remained less well defined.

In this study, we examined how two chromatin remodelers, INO80 and CHD1, influence the activity of AP endonucleases from three organisms: E. coli endonuclease IV, yeast APN1, and human APE1 on nucleosome substrates. Together with our previous findings on INO80-C and APE1, our results reveal that chromatin remodelers can stimulate AP endonuclease activity through mechanisms that do not strictly depend on productive nucleosome sliding. Notably, this stimulatory effect is conserved among eukaryotic AP endonucleases but absent for the bacterial enzyme, underscoring a fundamental difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic repair strategies.

Our data support a model in which chromatin remodelers facilitate base excision repair through both remodeling-dependent and remodeling-independent mechanisms. In particular, remodeler binding to damaged nucleosomes, coupled in some cases to ATP hydrolysis, can induce local DNA distortions that enhance lesion accessibility without requiring extensive DNA translocation. The choice between these modes of action is likely influenced by lesion position, and the local chromatin environment, including histone variants, post-translational modifications, and the presence of additional repair factors. Such mechanistic flexibility is consistent with the multifaceted roles of chromatin in coordinating DNA repair in vivo.

Interestingly, CHD1 has previously been shown to utilize ATP hydrolysis to promote histone deposition and nucleosome assembly even under conditions where nucleosome sliding is minimal [

21]. This observation supports the idea that ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers can exert biologically meaningful functions that are mechanistically separable from canonical DNA translocation. Our findings extend this concept to base excision repair, highlighting remodeler binding–induced chromatin plasticity as an important and previously underappreciated contributor to lesion processing in chromatin.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Expression of Recombinant Chromatin Remodelers

Genes for the subunits of the

S. cerevisiae INO80 core complex were cloned into pACEBAC1 vector using the MultiBac system (Geneva Biotech) for baculovirus expression as described previously [

18]. Genes were combined to produce three bacmids (Ino80/Arp5/Ies6/Ies2, Rvb1/Rvb2, Arp4/Arp8/Act1/Ies4/Taf14). Three bacmids were co-transfected into Hi-five cells to express the eleven subunit INO80 ΔN sub-complex, a truncated form of Ino80 (residue 470 from 1490). The recombinant complex was purified through Strep Tactin column, MonoQ chromatography, and size-exclusion chromatography as previously described (18). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and the fractions containing the pure complex were polled, concentrated (to 2uM), and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage.

The human CHD1 gene was cloned into pACEBAC1 vector with N-terminal 6xHis tag and expressed in insect cells SF9. Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (1 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 1 mM TCEP, protease inhibitor tablet), sonicated and cleared by ultracentrifugation. The lysate was filtered using 0.45 µm syringe filters (Millipore) and applied onto a HisTrap HP 5 mL (Cytiva), pre-equilibrated in lysis buffer. Column was washed with 10 CV lysis buffer supplemented with 30mM immidasole, and protein was eluted with elution buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10% glycerol (v/v), 1 mM TCEP, 300 mM imidazole). Eluted fractions were then applied to an MonoQ 4.6/10 PE (Cytiva) column and further purified using a salt gradient (200 mM NaCl to 1 M NaCl). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the fractions containing the pure complex were pooled, concentrated (to 2 μM), and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage.

4.2. Histone Purification and Octamer Reconstitution

Xenopus laevis histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 were expressed in bacteria, purified, and used for nucleosome reconstitution as previously described [

22].

4.3. APN1 Purification

The APN 1 gene from S. Cerevisiae was cloned into pGEX-4t vector and the proteins was expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells with 1 mM of IPTG at 30°C for 4 hours. The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 400 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, protease inhibitors, and 2 mM DTT], and then sonicated and centrifuged at 15,000×g for 40 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered through 0.45 μm filter and applied to Glutathione Sepharose beads (GE17-0756-0) and incubated at 4°C for two hours. to Glutathione Sepharose beads were washed with lysis buffer three times and protein was released by Thrombin digestion overnight, followed by purification on Heparin coulmn (Cytiva) with salt gradient [50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 100- 1000 mM NaCl]. Clean fractions were pooled, concentrated flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage.

4.4. APE1 Purification

Human APE1 in the pet28a vector was expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells with 0.4 mM IPTG at 20°C overnight. The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, protease inhibitors], and then sonicated and centrifuged down at 15,000×g for 40 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered through 0.45 μm filters and applied to Heparin coulmn (Cytiva) followiing purification by salt gradient [50 mM HEper pH 7.4, 100- 1000 mM NaCl]. The fractions contatining APE1 were pooled and further purified using cation exchange (MonoQ) and gel filtration columns (Superdex 200). Clean fractions were pooled, concentrated flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage.

4.5. DNA

4.5.1. Purification of 0N80 DNA

Multiple copies of end-positioned 0N80 (80 base pairs of extranucleosomal DNA at one site) Widom 601 DNA (WT) were cloned into the plasmid pGEM-3z/60, which is a kind gift from Jonathan Widom (Addgene plasmid #26656) [

23]. The sequence of the 0N80 DNA is as follows:

CTGGAGAATCCCGGTGCCGAGGCCGCTCAATTGGTCGTAGCAAGCTCTAGCACCGCTTAAACGCACGTACGCGCTGTCCCCCGCGTTTTAACCGCCAAGGGGATTACTCCCTAGTCTCCAGGCACGTGTCAGATATATACATCCTGTGCATGTATTGAACAGCGACCTTGCCGGTGCCAGTCGGATAGTGTTCCGAGCTCCCACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGTACCGA.

Large scale plasmid purification was performed as described before [

22]. The restriction enzyme ScaI was used to liberate a single repeat of the 0N80 segment. Anion exchange chromatography with a HQ Poros column (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to further purify the DNA fragments.

4.5.2. Separation of 0N80Double Strand DNA into Its Single Strands

Single strands or double stranded 0N80 DNA were separated in an alkaline (10 mm NaOH) salt gradient (600 mM 800 mM NaCl). 0N80 DNA was incubated in 10 mM NaOH/ at room temperature for 15 min, The DNA was loaded onto the MonoQ 4.6/10 PE (Cytiva) column 10 mm NaOH 600mM NaCl, and eluted with increasing NaCl concentrations in the presence of 10 mm NaOH, resulting in two clearly separated peaks. DNA fractions were neutralized by adding 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2). Each single strand of DNA was precipitated with 2.5 volumes of ethanol.

4.5.3. Fluorescent Damaged DNA Preparation

0N80 Widom DNAs containing lesions dTHF and FAM label were generated using modified ligation strategy as described [

24]. Briefly, a set of oligonucleotides were synthesized for each damaged Widom 601 sequence. Sequence information of these oligoes is included in the

Table S1. Oligoes in each set were annealed with complemented ssDNA and then treated with T7 DNA ligase (NEB). Oligonucleotides were mixed in equimolar amounts in 1.3 times excess over ssDNA in an annealing buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA] to a final concentration of 50 uM of each oligo. Annealing was done by heating the reaction to 95 °C for 5 min and cooling it to room temperature at 1 °C per minute. Ligase buffer and T7 DNA Ligase (NEB) were added to the annealing reaction at 0.125x of the annealing reaction volume. Ligase reactions were kept at room temperature for 24 h and then stored at 4 °C until purification. The DNA fragment was purified as described (25). Briefly, a MonoQ 4.6/10 PE (Cytiva) column with a long gradient (70 Column Volume, from 0.6 M NaCl to 0.8 M NaCl, flow rate of 0.1 ml/min) was used to separate the DNA fragments. Peak fractions were combined followed by DNA precipitation through Isopropanol. DNA pellets were dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 0.1 mM EDTA) to a final concentration of 0.5 to 1 mg/ml. The DNAs were then resolved on 15% TBE-Urea gels (Invitrogen) and stained with SYBR-Gold for visualization, to ensure the purity and that negligible nicks and gaps are present in the DNA templates.

4.5.4. Nucleosome Reconstitutions

WT and THF-containing nucleosomes (containing double THF at SHL-6 or SHL-2.5 positions and 6-FAM label on 5’ of the 601 DNA on the same strand) were reconstituted by mixing the octamer with 0N80 601 Widom sequence containing the specific DNA lesion in equal molar ratio in high-salt buffer [10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 2 M NaCl and 2 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol (βME)], followed by overnight dialysis into low salt buffer [10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaCl and 2 mM βME] as described [

22]. The optimal ratio of DNA to octamer was determined empirically through careful titrations and examination by the electro-mobility shift assay (EMSA).

4.6. AP-Endonuclease Incision Assay

Nucleosome incision reactions were performed in a total volume of 30 µl in incision buffer [25 mM HEPES pH8.0, 75 mM NaCl, 2.5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA)]. Reactions included 100 nM THF-containing nucleosomes, AP endonucleases, and either 50 nM INO80-C core complex or 50 nM hCHD1, as indicated. Remodelers were excluded in control reactions. For indicated experiments shown in

Figure 2 & 3, 2 mM ATP was included. Reactions were incubated at room temperature for the THF(SHL-6) nucleosome experiments and 37°C for the THF (SHL-2.5) nucleosome experiments. Aliquots were collected at the indicated time points. Reactions were quenched by addition of an equal volume of 2× Urea-TBE loading buffer (Invitrogen), followed by incubation at 95°C for 10 min to denature duplex DNA. Reaction products were resolved on 12% Urea-TBE denaturing polyacrylamide gels and imaged using a Typhoon scanner (Cytiva). Substrate and product bands were quantified using ImageJ software, and the percentage of incised nucleosomes was plotted as a function of time using GraphPad Prism.

4.7. Nucleosome Sliding Assay

End-positioned 0N80 nucleosomes with and without DNA lesions (100 nM) were incubated with either INO80 complexes (200 nM) or CHD1 protein (200 nM) in sliding buffer [25mM HEPES pH8.0, 50mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1mM TCEP and 2mM MgCl2] in a final volume of 10 µl at room temperature. Sliding was initiated by adding 1 mM ATP and stopped by adding 5 mM EDTA and 0.2mg/ml lambda DNA (NEB). Reactions at different time-points were collected and resolved on 6% Native-PAGE at 4°C (100V, 90min, 1x TBE). Gels were stained with SYBR-GOLD (GoldBio) before imaging on a Typhoon imager (Cytiva).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

V.S., R.J. performed the biochemical experiments. V.S. performed data analysis and quantification. V.S. and D.T. conceptualized the project and made the figures. D.T. oversaw the project and wrote the manuscript with help from all authors.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences of NIH under award number 1R35GM133611 and the National Science Foundation under award number 1942049 and by the Research Foundation of Stony Brook University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- David, S.S.; O'Shea, V.L.; Kundu, S. Base-excision repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nature 2007, 447, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, P.M.; Guibourt, N.; Boiteux, S. The Ogg1 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase/AP lyase whose lysine 241 is a critical residue for catalytic activity. Nucleic Acids Res 1997, 25, 3204–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.L.; Schar, P. DNA glycosylases: In DNA repair and beyond. Chromosoma 2012, 121, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kemp, P.A.; Thomas, D.; Barbey, R.; de Oliveira, R.; Boiteux, S. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the OGG1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which codes for a DNA glycosylase that excises 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine and 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-N-methylformamidopyrimidine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 5197–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthoudakis, S.; Smeyne, R.J.; Wallace, J.D.; Curran, T. The redox/DNA repair protein, Ref-1, is essential for early embryonic development in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 8919–8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, J.; Khetan, V.; Madhusudan, S.; Krishnakumar, S. Dysregulation of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) expression in advanced retinoblastoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2014, 98, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrache, L.C.; Shimada, M.; Downing, S.M.; Kwak, Y.D.; Li, Y.; Illuzzi, J.L.; Russell, H.R.; Wilson, D.M., 3rd; McKinnon, P.J. Apurinic endonuclease-1 preserves neural genome integrity to maintain homeostasis and thermoregulation and prevent brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E12285–E12294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Zhao, J.; Talluri, S.; Buon, L.; Mu, S.; Potluri, L.B.; Liao, C.; Shi, J.; Chakraborty, C.; Gonzalez, G.B.; et al. Elevated APE1 Dysregulates Homologous Recombination and Cell Cycle Driving Genomic Evolution, Tumorigenesis, and Chemoresistance in Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakat, K.K.; Mantha, A.K.; Mitra, S. Transcriptional regulatory functions of mammalian AP-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1), an essential multifunctional protein. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009, 11, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniali, G.; Dalla, E.; Mangiapane, G.; Zhao, X.; Jing, X.; Cheng, Y.; De Sanctis, V.; Ayyildiz, D.; Piazza, S.; Li, M.; et al. APE1 controls DICER1 expression in NSCLC through miR-33a and miR-130b. Cell Mol Life Sci 2022, 79, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniali, G.; Serra, F.; Lirussi, L.; Tanaka, M.; D'Ambrosio, C.; Zhang, S.; Radovic, S.; Dalla, E.; Ciani, Y.; Scaloni, A.; et al. Mammalian APE1 controls miRNA processing and its interactome is linked to cancer RNA metabolism. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codrich, M.; Degrassi, M.; Malfatti, M.C.; Antoniali, G.; Gorassini, A.; Ayyildiz, D.; De Marco, R.; Verardo, G.; Tell, G.; et al. APE1 interacts with the nuclear exosome complex protein MTR4 and is involved in cisplatin- and 5-fluorouracil-induced RNA damage response. FEBS J 2023, 290, 1740–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vascotto, C.; Fantini, D.; Romanello, M.; Cesaratto, L.; Deganuto, M.; Leonardi, A.; Radicella, J.P.; Kelley, M.R.; D'Ambrosio, C.; Scaloni, A.; et al. APE1/Ref-1 interacts with NPM1 within nucleoli and plays a role in the rRNA quality control process. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 1834–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Bao, S.; Guo, R.; Johnson, D.G.; Shen, X.; Li, L. INO80 chromatin remodeling complex promotes the removal of UV lesions by the nucleotide excision repair pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 17274–17279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothandapani, A.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Kahali, B.; Reisman, D.; Patrick, S.M. Downregulation of SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling factor subunits modulates cisplatin cytotoxicity. Exp Cell Res 2012, 318, 1973–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, R.; Sancar, A. The SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling factor stimulates repair by human excision nuclease in the mononucleosome core particle. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22, 6779–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthemann, P.; Balbo Pogliano, C.; Codilupi, T.; Garajova, Z.; Naegeli, H. Chromatin remodeler CHD1 promotes XPC-to-TFIIH handover of nucleosomal UV lesions in nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J 2017, 36, 3372–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, V.; Lee, G.; Mullins, A.; Mody, P.; Watanabe, S.; Tan, D. DNA-translocation-independent role of INO80 remodeler in DNA damage repairs. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 105245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, R.; Willhoft, O.; Aramayo, R.J.; Wilkinson, M.; McCormack, E.A.; Ocloo, L.; Wigley, D.B.; Zhang, X. Structure and regulation of the human INO80-nucleosome complex. Nature 2018, 556, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustermann, S.; Schall, K.; Kostrewa, D.; Lakomek, K.; Strauss, M.; Moldt, M.; Hopfner, K.P. Structural basis for ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling by the INO80 complex. Nature 2018, 556, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torigoe, S.E.; Patel, A.; Khuong, M.T.; Bowman, G.D.; Kadonaga, J.T. ATP-dependent chromatin assembly is functionally distinct from chromatin remodeling. Elife 2013, 2, e00863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, P.N.; Edayathumangalam, R.S.; White, C.L.; Bao, Y.; Chakravarthy, S.; Muthurajan, U.M.; Luger, K. Reconstitution of nucleosome core particles from recombinant histones and DNA. Methods Enzymol 2004, 375, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lowary, P.T.; Widom, J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol 1998, 276, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.R.; Smerdon, M.J. UV damage in DNA promotes nucleosome unwrapping. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 26295–26303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, E.; Eriksson, S.; Laas, T.; Pernemalm, P.A.; Skold, S.E. Separation of DNA restriction fragments by ion-exchange chromatography on FPLC columns Mono P and Mono Q. Anal Biochem 1987, 166, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |