1. Introduction

In the last few decades, fungal infections have undergone a dramatic rise worldwide, being responsible for approximately 1.7 million deaths per year [

1], although another study increases this number to 2.5 million [

2]. In 2022, the WHO published the first list of fungal priority pathogens, with the intention to guide new research, development, and public health actions [

3]. This list categorizes fungal infections into three priority groups: critical, high, and medium. The critical group includes

Cryptococcus neoformans,

Candidozyma (formerly

Candida)

auris,

Aspergillus fumigatus, and

Candida albicans.

Fungi have traditionally been considered less significant pathogens than bacteria or viruses, and, therefore, they have received limited attention from both public organizations and pharmaceutical companies [

4]. However, the number of deaths attributable to the main invasive fungal diseases is comparable to those produced by tuberculosis or malaria [

5]. This scenario has worsened in recent decades due to the increasing isolation of fungal pathogens responsible for outbreaks in both hospitals and community settings, mainly associated with the increase of the immunocompromised population. Furthermore, the opportunistic pan-resistant yeast

Candidozyma (

Candida)

auris, represents a serious concern in intensive care units and among the immunodepleted people [

6] [

1,

7]. In addition, the growing number of fungal strains resistant to conventional antifungal compounds complicates the development of a safe and effective chemotherapy against highly prevalent infectious fungi [

8,

9,

10].

Another problem comes from the worrying rise of resistant strains. The mechanisms involved in resistance are complex [

11] and imply secondary pathways that contribute to the whole toxicity. These new routes are frequently poorly understood [

12]. Excluding certain molecules applied to specific mycosis, the three main families of antifungal drugs currently in use (Polyenes, Azoles, and Echinocandins) are classified according to their chemical structure and mechanism of action, so far established, rather than their host range. Given the availability of several comprehensive revisions on this topic, we will provide brief comments on some relevant aspects that have not been sufficiently addressed previously [

4,

13,

14,

15].

1.1. Polyenes

The macrolide amphotericin B (AMB) remains one of the most widely used compounds in clinical therapy to treat most superficial and severe fungal infections, such as cryptococcosis, candidiasis, aspergillosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis. The therapeutic value of this polyene is reinforced by the fact that resistance to AMB remains unexpectedly rare after long daily application in clinical therapy [

16]. Furthermore, its undesirable side effects, like nephro- and hepatotoxicity as well as allergic reactions, have been surmounted by novel liposomal formulations and other innovative drug formulations, which are less toxic but have increased the economic costs of their prescription [

4]. In contrast, nystatin is less commonly used because of its higher toxicity and poor absorption through the digestive tract. The pleiotropic mechanism of action of polyenes has been extensively analyzed in other works [

17,

18,

19,

20].

1.2. Azoles

This group of cyclic organic molecules contains the largest number of antifungals. In particular, the former triazoles (i.e., fluconazole (FLC) and itraconazole (ITC), and those of the second generation (i.e., voriconazole (VRC) or posaconazole) show high efficacy against opportunistic mycosis, and are applied for prophylaxis of invasive infections caused by

Candida and

Aspergillus [

21,

22]. One of the main drawbacks is that azoles act essentially as fungistatic rather than fungicide drugs. For a better understanding of their action and the disadvantages of administering them, the following documents are available [

14,

15]. A matter of concern stems from the fact that resistance to azolic compounds has increased in recent years due to point mutations or upregulation of the

ERG11 gene as well as in other genes of the ergosterol pathway (

ERG3) or genes involved in the drug efflux pumps (

CDR1,

CDR2, and

MDR1) that allow efficient exclusion of internal antifungal drugs [

14]. The presence of active biofilms or alterations of metabolic pathways leading to a reduction or loss of function are also additional ways to acquire resistance.

1.3. Echinocandins

These semisynthetic lipopeptides represent the most recently approved family of antifungals (first decade of the 21st century) that target the fungal cell wall. Three compounds are in clinical use: caspofungin (CAS), micafungin (MCF), and anidulafungin, but a fourth echinocandin, rezafungin, has recently been approved [

23]. The main therapeutic limitation of echinocandins is their restricted and rather diverse range of antifungal activity. Thus, they possess a strong fungicidal action against clinical isolates of

Candida spp, while their effect on

Aspergillus spp is mainly fungistatic, and most pathogenic

Cryptococcus spp are refractory to echinocandins treatment, including rezafungin [

23]. Moreover, a growing number of opportunistic yeasts have acquired resistance to echinocandins due to mutations in genes that encode the glucan synthase complex, which is essential for cell wall architecture [

24,

25]. Likewise, some side-off gastrointestinal and cardiovascular effects have been reported in treated patients [

15].

2. The Search for New Antifungal Targets Is a Therapeutic Need

The search for new antifungal drugs is an urgent need due to the increasing incidence of systemic fungal infections and the emergence of antifungal-resistant pathogens that cannot be counteracted with the current clinical therapies [

26]. Different compounds, directed mainly to invasive mycoses, are under clinical trials [

27]. In fact, rezafungin and fosravuconazole (for the treatment of mycetoma) have been approved in recent years [

23,

28,

29].

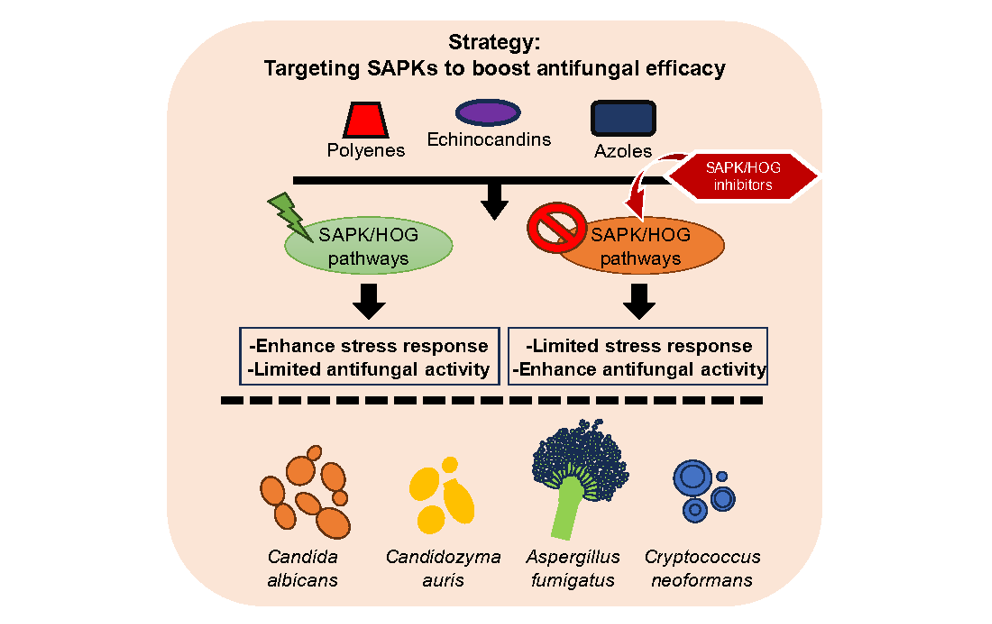

A major challenge in antifungal chemotherapy is the eukaryotic nature of fungi. Since infectious pathogens and their hosts share similar cellular structures, this results in low selective toxicity for treatments. Therefore, exploring alternative antifungal targets could lead to new therapeutic strategies. One promising target unique to fungi is the two-component system, which is absent in animal cells. These signaling systems are positioned upstream of Stress-Activated Protein Kinase (SAPK) pathways, essential for proper adaptation to environmental stresses.

3. Sensing Antifungals by SAPK Pathways in WHO High-Priority Fungal Pathogens

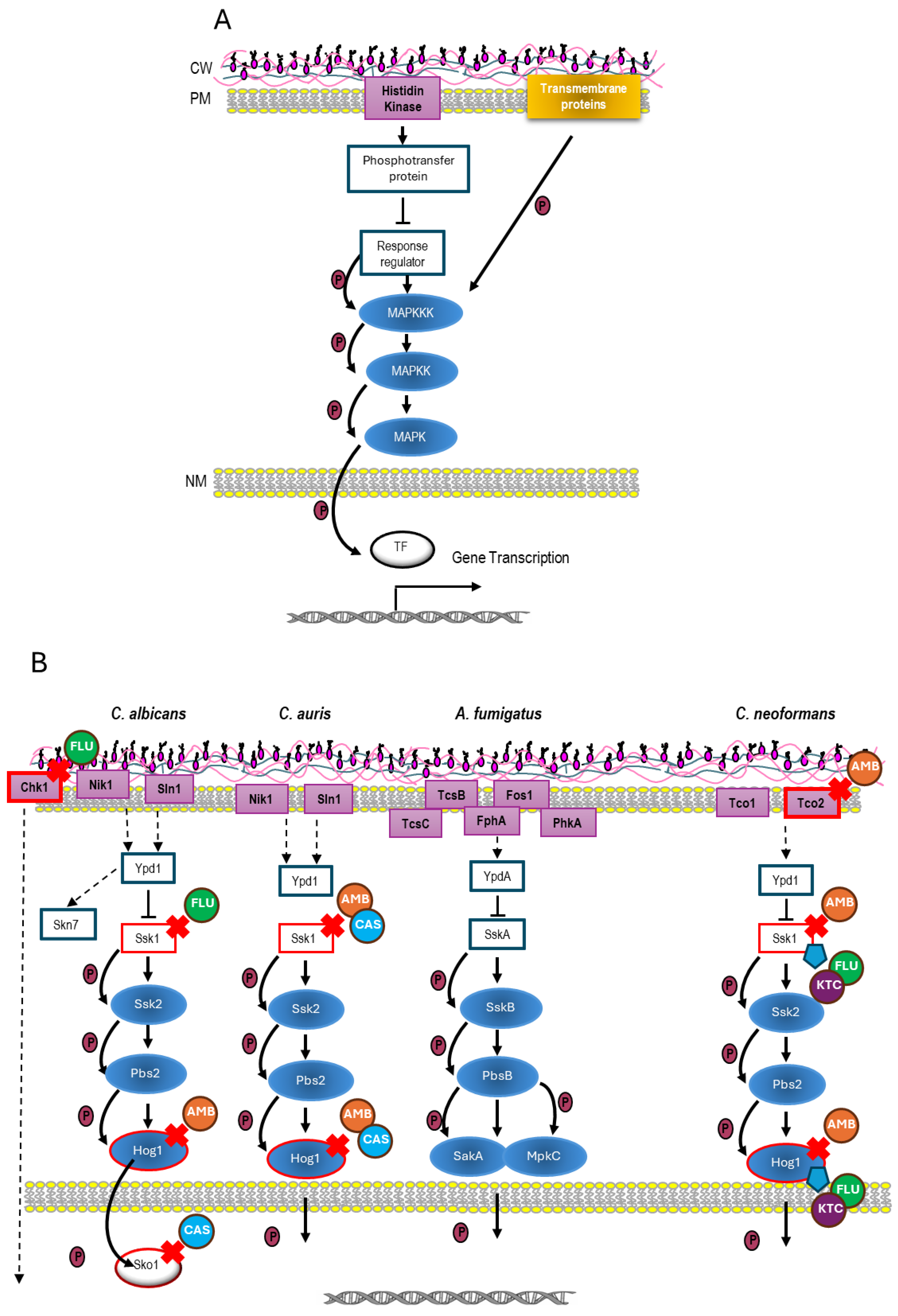

MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase)-mediated pathways are signaling cascades widely conserved in all eukaryotic organisms, playing essential functions in cell physiology, such as mating, cell integrity, vegetative growth, and stress response [

30,

31,

32]. In particular, they appear to perform a main role in the pathobiology of fungi [

33,

34]. The general structure of a prototypic MAP kinase consists of a module of three MAP kinases, which activate each other through phosphorylation (

Figure 1A). This module receives signals through different mechanisms, such as transmembrane sensors coupled to GTPase proteins, two-component systems, other protein kinases, or intracellular sensors [

34]. Although the MAPK module is strictly conserved, differences have been reported in the upstream and downstream elements, as well as crosstalk and regulation among fungi (

Figure 1).

Within the large group of MAP kinases, a subfamily present only in animals and fungi has recently emerged. This subfamily, named “Stress-activated protein kinase” (SAPK), is crucial in fungi for adaptation to acute environmental stimuli, including the sensing and subsequent signal transduction of antimycotic agents [

35]. These SAPKs have been broadly studied in the yeast models

Saccharomyces cerevisiae and

Schizosaccharomyces pombe and, to a lesser extent, in the pathogenic fungi

C. albicans, C. auris, A. fumigatus, and

C. neoformans [

34]. In some fungal species, the SAPK pathway has been termed the High-Osmolarity Glycerol response (HOG) pathway, and consequently, the MAPK of the pathway was named Hog1. Although in

S. cerevisiae the MAPK module can be activated through two independent branches (

Figure 1A), in other priority fungal pathogens, only one signaling branch can trigger the MAPK Hog1 counterparts [

34].

Interestingly, this conserved signaling mechanism is based on a two-component system. These systems are common parts of signal transduction pathways, widely found in prokaryotes, plants, and fungi, but they seem to be absent in animal cells [

34,

35]. In most eukaryotes, the two-component system functions as a multi-step phosphate transfer system involving four sequential phosphorylation events (

Figure 1). These signaling pathways are coordinated by an osmosensor, an intermediate phosphorelay protein, and a response regulator protein [

36]. The role of SAPK pathways in cellular responses to various environmental stresses, including virulence, has been well documented [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Notably, among these stresses, the HOG pathway homologs can detect and respond to several antifungal agents. In fact, mutants lacking these signaling pathways are more vulnerable to certain antifungals. In this review, we highlight the structural similarities and differences among SAPK pathways in high-priority fungal pathogens, emphasizing their role in detecting antifungal compounds.

3.1. SAPK Pathway in C. albicans: The HOG Pathway

C. albicans remains the most common fungal pathogen in humans worldwide, where it tends to colonize the oral cavity, gut, and vagina. Productive infections occur preferentially when immune defenses are compromised, leading to candidiasis that can range from superficial to systemic [

36]. The HOG pathway in

C. albicans encompasses a two-component system and the MAPK module, which is composed of the proteins Ssk2 (MAPKKK), Pbs2 (MAPKK), and Hog1 (MAPK) (

Figure 1B). This module is activated by a two-component system in which are involved three histidine kinase sensors, termed Sln1, Nik1, and Chk1, whose specific function remains unclear, although Sln1 seems to play a predominant role in Hog1 signaling [

37,

38,

39]. Extensive research has demonstrated the essential role of the HOG pathway in virulence and cellular response to several environmental stresses, including antimicrobial peptides [

40,

41,

42]. Notably, deletion of the intermediate phosphorelay protein Ypd1 in

C. albicans enhances the degree of virulence [

43], compromising its use as an antifungal target.

Interestingly, the HOG pathway is activated in response to AMB, whereas a set of

hog1Δ null mutants display hypersensitivity to this polyene [

44]. Hog1 phosphorylation, together with its intrinsic kinase activity, is required to deal with AMB exposure in

C. albicans [

44]. In the case of echinocandins, a conspicuous CAS-induced Hog1-activation was recorded with simultaneous stimulation of the oxidative stress response [

45], whereas Hog1p is not phosphorylated after MCF supply [

46,

47]. Notably, the sensing and further response to CAS is partially dependent on the transcription factor Sko1 in a HOG-independent way [

48]. Moreover,

ssk1 and

chk1 mutants are highly sensitive to FLC and voriconazole [

49]. In summary, although

C. albicans can respond to antifungals through distinct alternative mechanisms (e.g., the transcription factor Sko1), the impairment of the HOG pathway at different levels leads to a higher susceptibility to antifungals commonly used to treat candidiasis. Thus, this scenario suggests that it might be worthwhile to explore new formulations of combinatory therapy.

3.2. SAPK Pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus: The SakA and MpkC Mediated Pathway

Among the numerous

Aspergillus species,

A. fumigatus is the most virulent in humans. This fungus causes allergies and opportunistic infections with a high incidence in immunocompromised individuals, mainly in neutropenic patients. The growing isolation of

A. fumigatus strains resistant to azoles and echinocandins is considered a potential public health concern [

50,

51].

Unlike other fungi, the HOG homolog in

A. fumigatus is more complex. This SAPK pathway is integrated by a MAPKKK (SskB), a MAPKK, (PbsB), and two MAPKs: SakA and MpkC. These MAPKs share each other 68.4% identity but differ in their kinetic and physiological functions (

Figure 1B). SakA mediates adaptation to antifungals and cold stress, while MpkC is involved in the use of carbon sources (reviewed by Day [

34]). Both SakA and MpkC are relevant for virulence [

52]. This pathway is also involved in the response to osmotic and oxidative stress, cell wall-damaging agents, and antifungals such as CAS and nikkomycin Z [

52].

Two branches placed upstream mediate signaling to the MAPK module. The first consists of a fairly elaborated two-component system, since at least 4 histidine kinases have been reported to control the specific signaling through this pathway (see [

34,

53]) (

Figure 1B). TcsB (later named SlnA) seems to be homologous to

C. albicans Sln1, and the main sensor of this branch. Histidine kinases can phosphorylate the phosphorelay protein homolog to Ypd1, known as YpdA, which in turn phosphorylates the response regulator SskA [

54].

A second signaling branch mediates the activation of both the HOG and the cell wall integrity pathway. This branch is composed of ShoA (Sho1 homolog), MsbA (Msb2 homolog), and OpyA (Opy2 homolog), and acts together with the two-component system in the full activation of SakA and MpkC in response to different stresses [

54,

55]. Among these, both SakA and MpkC are phosphorylated in response to CAS exposure [

54]. This activation was significantly impaired in an

msbA mutant, suggesting that the second branch plays a predominant role after CAS addition. Proteomic analyses in response to CAS treatments showed that PKA, CWI, and HOG pathways are closely coordinated [

56]. Furthermore, transcriptomic arrays using clinical isolates of

A. fumigatus indicated that exposure to ITC induces a set of transcriptional changes that involve, among others, some proteins belonging to the HOG pathway [

57], suggesting that this pathway may be activated in the presence of this antifungal. Although in

A. fumigatus the HOG homologous pathway involves multiple signaling branches, data suggest that preventing its activation increases the susceptibility to antifungals such as CAS. Invasive aspergillosis is a severe disease that requires the use of agents such as VRC and AMB, although therapies using posaconazole, itraconazole, CAS, and other echinocandins are also effective.

3.3. SAPK Pathway in Cryptococcus neoformans: The HOG Pathway

C. neoformans ranks first in the WHO list of high-priority fungal pathogens, since it causes fatal meningoencephalitis, mainly in immunocompromised individuals. A relevant attribute of its virulence is the presence of an antiphagocytic polysaccharidic capsule [

3].

In

C. neoformans, the HOG pathway controls mating, melanin and capsule production, as well as ergosterol biosynthesis and cellular ergosterol content [

58]. Unlike other fungi, in a fraction of clinical isolates, Hog1 is constitutively phosphorylated under standard conditions and becomes actively dephosphorylated in response to different kinds of stress [

59]. Activation of the MAPK module is carried out by a two-component system located upstream. This system is integrated by a response regulator, Ssk1, a phosphotransfer protein Ypd1, and seven histidine kinases, Tco1 to Tco7 [

60] (

Figure 1B). Tco1 and Tco2 have priority and specific functions, which somehow overlap, with Tco1 being more relevant for virulence in a murine model of meningitis [

60] while Tco2 mediates susceptibility to AMB. In fact, mutants defective in Tco2 display sensitivity to AMB [

58].

Transcriptomic analyses revealed that in

C. neoformans, genes involved in sterol biosynthesis were upregulated in

hog1Δ and

ssk1Δ mutants, resulting in enhanced ergosterol content and hypersensitivity to AMB [

58]. The analysis of strains with different levels of constitutive Hog1 phosphorylation showed a Hog1-induced repression of ergosterol biosynthesis under standard growth conditions. In contrast,

ssk1Δ and

hog1Δ mutants displayed increased resistance to KTC (imidazole) and FLC but not to ITC (triazole) [

58]. In summary, inactivation of the HOG pathway increases both the biosynthesis and content of ergosterol, which confers sensitivity to AMB and resistance to FLC and KTC. The treatment of disseminated cryptococcal disease with risk of CNS perturbations is divided into three phases. In the first phase, a combination of AMB plus flucytosine is applied. The subsequent consolidation, maintenance, and prophylaxis phases are based on FLC, although other azoles can be used. When implementing a combination therapy that includes AMB plus a potential HK inhibitor, the use of FLC should be avoided in favor of ITC to prevent treatment failure.

4. Histidine Kinase Inhibitors Under Study

Elements of the two-component system, either the histidine kinase or the response regulator, have long been considered appropriate antimicrobial targets [

61,

62]. Several molecules have been identified as potential histidine kinase/two-component system inhibitors [

63], some of which are currently under investigation in preclinical phases (e.g., waldiomycin, walkmycin, closantel, among others) to treat different bacterial infections.

Several screening methods for identifying inhibitors of fungal histidine kinases have been developed, and their effectiveness has been tested with known histidine kinase inhibitors such as fludioxonil [64]. To date, none have been approved for human use, although fludioxonil is used in agriculture. Interestingly, this compound has been reported to activate the MAPK Hog1

in C. neoformans, while the

hog1 mutant was resistant to it [

60]. To our knowledge, susceptibility of this fungus to treatment with fludioxonil combined with any clinical antifungal has not been reported. Additionally, it should be noted that fludioxonil itself may induce resistance to FLC in

C. albicans [64]. This suggests that other histidine kinase inhibitors could cause a similar resistant phenotype in this or other fungi. This undesirable effect could be mitigated by combining this compound with other approved standard antifungals.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives.

Current antifungal treatments are insufficient to address the growing issue of systemic mycosis caused by highly infectious fungi in humans. Therefore, alternative therapeutic strategies need to be explored. Here, we suggest targeting upstream elements of highly conserved SAPK pathways as potential antifungal options, due to their vital role in fungal biology, including virulence, cell morphogenesis, cell-wall structure, and environmental stress responses. Initial data show that several antifungals can activate SAPK signaling, triggering a response aimed at fungal survival. Combining well-established antifungal drugs with formulations that prevent SAPK activation could enhance treatment effectiveness and reduce resistance development. However, the existing evidence is limited, and more robust data from both in vitro and in vivo studies are necessary.

Funding

RAM’s work is supported by Grant PID2021-122648NB-I00 from MINECO, Spain.

Acknowledgments

JCA is indebted to the financial contract provided by PREZERO, Servicios Públicos de Murcia, S.A. (Murcia, Spain).

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations:

WHO: World Health Organization; AMB: Amphotericin B; CAS: Caspofungin; MCF: Micafungin; ITC: Itraconazole; FLC: Fluconazole; KTC: Ketoconazole; VRC: Voriconazole; CNS: Central nervous system.

References

- Kainz, K.; Bauer, M.A.; Madeo, F.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D. Fungal infections in humans: The silent crisis. Microb Cell 2020, 7, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W. Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, e428–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. World Health Organization (WHO) Report. WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arguelles, J.C.; Sanchez-Fresneda, R.; Arguelles, A.; Solano, F. Natural Substances as Valuable Alternative for Improving Conventional Antifungal Chemotherapy: Lights and Shadows. J Fungi 2024, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.D.; Denning, D.W.; Gow, N.A.; Levitz, S.M.; Netea, M.G.; White, T.C. Hidden killers: Human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 165rv113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.E.; Jacobs, J.L.; Dennis, E.K.; Taimur, S.; Rana, M.; Patel, D.; Gitman, M.; Patel, G.; Schaefer, S.; Iyer, K.; et al. Candida auris Pan-Drug-Resistant to Four Classes of Antifungal Agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022, 66, e0005322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.C.; Barat, S.A.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Angulo, D.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chaturvedi, V. Pan-resistant Candida auris isolates from the outbreak in New York are susceptible to ibrexafungerp (a glucan synthase inhibitor). Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020, 55, 105922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.G.; Diekema, D.J. What Is New in Fungal Infections? Mod Pathol 2023, 36, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: A persistent public health problem. Clinical Microbiological Reviews 2007, 20, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Messer, S.A.; Deshpande, L.M.; Rhomberg, P.R.; Utt, E.A.; Castanheira, M. Antifungal drugs work together to treat germs causing fungal infections. Future Microbiol 2021, 16, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlin, D.S.; Wiederhold, N.P. Culture-Independent Molecular Methods for Detection of Antifungal Resistance Mechanisms and Fungal Identification. J Infect Dis 2017, 216, S458–S465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlin, D.S.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A. The global problem of antifungal resistance: Prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, E383–E392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanreppelen, G.; Wuyts, J.; Van Dijck, P.; Vandecruys, P. Sources of Antifungal Drugs. J Fungi 2023, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campoy, S.; Adrio, J.L. Antifungals. Biochem Pharmacol 2017, 133, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, M.; Ciric, A.; Stojkovic, D. Emerging Antifungal Targets and Strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, B.M.; Lancaster, A.K.; Scherz-Shouval, R.; Whitesell, L.; Lindquist, S. Fitness Trade-offs Restrict the Evolution of Resistance to Amphotericin B. PLoS Biology 2013, 11, e1001692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.E. Amphotericin B membrane action: Role for two types of ion channels in eliciting cell survival and lethal effects. J Membr Biol 2010, 238, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermishkin, L.N.; Kasumov, K.M.; Potseluyev, V.M. Properties of amphotericin B channels in a lipid bilayer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1977, 470, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermishkin, L.N.; Kasumov, K.M.; Potzeluyev, V.M. Single ionic channels induced in lipid bilayers by polyene antibiotics amphotericin B and nystatine. Nature 1976, 262, 698–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.C.; Palacios, D.S.; Dailey, I.; Endo, M.M.; Uno, B.E.; Wilcock, B.C.; Burke, M.D. Amphotericin primarily kills yeast by simply binding ergosterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 2234–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W. Antifungal drug resistance: An update. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2022, 29, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francois, I.E.; Aerts, A.M.; Cammue, B.P.; Thevissen, K. Currently used antimycotics: Spectrum, mode of action and resistance occurrence. Curr.Drug Targets 2005, 6, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Vazquez, J.A. An evaluation of Rezafungin: The latest treatment option for adults with candidemia and invasive candidiasis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2024, 25, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlin, D.S. Mechanisms of echinocandin antifungal drug resistance. Ann Ny Acad Sci 2015, 1354, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwunnakorn, S.; Wakabayashi, H.; Kordalewska, M.; Perlin, D.S.; Rustchenko, E. FKS2 and FKS3 Genes of Opportunistic Human Pathogen Candida albicans Influence Echinocandin Susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Berman, J.; Bicanic, T.; Bignell, E.M.; Bowyer, P.; Bromley, M.; Bruggemann, R.; Garber, G.; Cornely, O.A.; et al. Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhou, J.; Ming, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, R.; Li, Y.; Feng, L.; Zeng, B.; Du, Y.; Wang, C. Next-generation antifungal drugs: Mechanisms, efficacy, and clinical prospects. Acta Pharm Sin B 2025, 15, 3852–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.; Nyuykonge, B.; Eadie, K.; Konings, M.; Smeets, J.; Fahal, A.; Bonifaz, A.; Todd, M.; Perry, B.; Samby, K.; et al. Screening the pandemic response box identified benzimidazole carbamates, Olorofim and ravuconazole as promising drug candidates for the treatment of eumycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022, 16, e0010159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M. This ‘super gonorrhoea’ drug holds a lesson for avoiding microbial armageddon. Nature 2024, 626, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.E.; Thorner, J. Function and regulation in MAPK signaling pathways: Lessons learned from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007, 1773, 1311–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Nicolet, J. Specificity models in MAPK cascade signaling. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13, 1177–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmann, C.; Gibson, S.; Jarpe, M.B.; Johnson, G.L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase: Conservation of a three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol Rev. 1999, 79, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Monge, R.; Román, E.; Pla, J.; Nombela, C. A host view of the fungal cell wall. In Evolutionary biology of bacterial and fungal pathogens; Baquero Mochales, F., Nombela, C., Cassel, G.H., Gutiérrez-Fuentes, J.A., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, D.C., 2009; pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Day, A.M.; Quinn, J. Stress-Activated Protein Kinases in Human Fungal Pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2019, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kultz, D.; Burg, M. Evolution of osmotic stress signaling via MAP kinase cascades. J.Exp.Biol. 1998, 201, 3015–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, D.M.; Iliev, I.D. The mycobiota: Interactions between commensal fungi and the host immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2014, 14, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calera, J.A.; Zhao, X.J.; Calderone, R. Defective hyphal development and avirulence caused by a deletion of the SSK1 response regulator gene inCandida albicans. Infection and Immunity 2000, 68, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calera, J.A.; Calderone, R. Histidine kinase, two-component signal transduction proteins ofCandida albicans and the pathogenesis of candidosis. Mycoses 1999, 42, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.; Inglis, D.; Román, E.; Pla, J.; Li, D.; Calera, J.A.; Calderone, R. Candida albicans response regulator gene SSK1 regulates a subset of genes whose functions are associated with cell wall biosynthesis and adaptation to oxidative stress. Eukaryotic Cell 2003, 2, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Monge, R.; Navarro-García, F.; Molero, G.; Díez-Orejas, R.; Gustin, M.; Pla, J.; Sánchez, M.; Nombela, C. Role of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1p in morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. Journal of Bacteriology 1999, 181, 3058–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arana, D.M.; Alonso-Monge, R.; Du, C.; Calderone, R.; Pla, J. Differential susceptibility of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mutants to oxidative-mediated killing by phagocytes in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Cellular Microbiology 2007, 9, 1647–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vylkova, S.; Jang, W.S.; Li, W.; Nayyar, N.; Edgerton, M. Histatin 5 initiates osmotic stress response in Candida albicans via activation of the Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Eukaryot Cell 2007, 6, 1876–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.M.; Smith, D.A.; Ikeh, M.A.; Haider, M.; Herrero-de-Dios, C.M.; Brown, A.J.; Morgan, B.A.; Erwig, L.P.; MacCallum, D.M.; Quinn, J. Blocking two-component signalling enhances Candida albicans virulence and reveals adaptive mechanisms that counteract sustained SAPK activation. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirao-Abad, J.P.; Sanchez-Fresneda, R.; Roman, E.; Pla, J.; Arguelles, J.C.; Alonso-Monge, R. The MAPK Hog1 mediates the response to amphotericin B in Candida albicans. Fungal Genet Biol 2020, 136, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Rowan, R.; McCann, M.; Kavanagh, K. Exposure to caspofungin activates Cap and Hog pathways in Candida albicans. Med.Mycol 2009, 47, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Monge, R.; Guirao-Abad, J.P.; Sanchez-Fresneda, R.; Pla, J.; Yague, G.; Arguelles, J.C. The Fungicidal Action of Micafungin is Independent on Both Oxidative Stress Generation and HOG Pathway Signaling in Candida albicans. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirao-Abad, J.P.; Sanchez-Fresneda, R.; Alburquerque, B.; Hernandez, J.A.; Arguelles, J.C. ROS formation is a differential contributory factor to the fungicidal action of Amphotericin B and Micafungin in Candida albicans. Int J Med Microbiol 2017, 307, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, M.Y.; Gunasekaran, D.; Ikeh, M.A.C.; Nobile, C.J.; Rauceo, J.M. Transcriptional regulation of the caspofungin-induced cell wall damage response in Candida albicans. Curr Genet 2020, 66, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, N.; Kruppa, M.; Calderone, R. The Ssk1p response regulator and Chk1p histidine kinase mutants of Candida albicans are hypersensitive to fluconazole and voriconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007, 51, 3747–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Effron, G.; Dilger, A.; Alcazar-Fuoli, L.; Park, S.; Mellado, E.; Perlin, D.S. Rapid detection of triazole antifungal resistance in Aspergillu fumigatus. J Clin Microbiol 2008, 46, 1200–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlin, D.S.; Mellado, E. Antifungal Mechanisms of Action and Resistance. Aspergillus Fumigatus and Aspergillosis 2009, 457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder Nascimento, A.C.; Dos Reis, T.F.; de Castro, P.A.; Hori, J.I.; Bom, V.L.; de Assis, L.J.; Ramalho, L.N.; Rocha, M.C.; Malavazi, I.; Brown, N.A.; et al. Mitogen activated protein kinases SakA(HOG1) and MpkC collaborate for Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Mol Microbiol 2016, 100, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, K.K.; Ringelberg, C.S.; Loros, J.J.; Dunlap, J.C. The fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus regulates growth, metabolism, and stress resistance in response to light. mBio 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.P.; Frawley, D.; Assis, L.J.; Tierney, C.; Fleming, A.B.; Bayram, O.; Goldman, G.H. Putative Membrane Receptors Contribute to Activation and Efficient Signaling of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascades during Adaptation of Aspergillus fumigatus to Different Stressors and Carbon Sources. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattos, E.C.; Silva, L.P.; Valero, C.; de Castro, P.A.; Dos Reis, T.F.; Ribeiro, L.F.C.; Marten, M.R.; Silva-Rocha, R.; Westmann, C.; da Silva, C.; et al. The Aspergillus fumigatus Phosphoproteome Reveals Roles of High-Osmolarity Glycerol Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases in Promoting Cell Wall Damage and Caspofungin Tolerance. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattos, E.C.; Palmisano, G.; Goldman, G.H. Phosphoproteomics of Aspergillus fumigatus Exposed to the Antifungal Drug Caspofungin. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokken, M.W.J.; Zoll, J.; Coolen, J.P.M.; Zwaan, B.J.; Verweij, P.E.; Melchers, W.J.G. Phenotypic plasticity and the evolution of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus; an expression profile of clinical isolates upon exposure to itraconazole. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.J.; Yu, Y.M.; Kim, G.B.; Lee, G.W.; Maeng, P.J.; Kim, S.; Floyd, A.; Heitman, J.; Bahn, Y.S. Remodeling of global transcription patterns of Cryptococcus neoformans genes mediated by the stress-activated HOG signaling pathways. Eukaryot Cell 2009, 8, 1197–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, Y.S.; Kojima, K.; Cox, G.M.; Heitman, J. Specialization of the HOG pathway and its impact on differentiation and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2005, 16, 2285–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, Y.S.; Kojima, K.; Cox, G.M.; Heitman, J. A Unique Fungal Two-Component System Regulates Stress Responses, Drug Sensitivity, Sexual Development, and Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2006, 17, 3122–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.F.; Hoch, J.A. Two-component signal transduction as a target for microbial anti-infective therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998, 42, 1529–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.F.; Goldschmidt, R.M.; Lawrence, L.E.; Foleno, B.; Chen, R.; Demers, J.P.; Johnson, S.; Kanojia, R.; Fernandez, J.; Bernstein, J.; et al. Antibacterial agents that inhibit two-component signal transduction systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 5317–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yu, C.; Wu, H.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Hong, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; You, X. Recent Advances in Histidine Kinase-Targeted Antimicrobial Agents. Front Chem 2022, 10, 866392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).