Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Contents

| 1. | Introduction | 4 |

| 2. | Core Interpretable Objects of LLMs | 5 |

| 2.1. Token Embedding................................................................................................................... | 5 | |

| 2.2. Transformer Block and Residual Stream............................................................................................. | 6 | |

| 2.3. Multi-Head Attention (MHA)........................................................................................................ | 7 | |

| 2.4. Feed-Forward Network (FFN)........................................................................................................ | 8 | |

| 2.5. Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) Feature.................................................................................................. | 8 | |

| 3. | Localizing Methods | 10 |

| 3.1. Magnitude Analysis................................................................................................................ | 10 | |

| 3.2. Causal Attribution................................................................................................................ | 13 | |

| 3.3. Gradient Detection................................................................................................................ | 14 | |

| 3.4. Probing........................................................................................................................... | 17 | |

| 3.5. Vocabulary Projection............................................................................................................. | 19 | |

| 3.6. Circuit Discovery................................................................................................................. | 10 | |

| 4. | Steering Methods | 23 |

| 4.1. Amplitude Manipulation............................................................................................................ | 23 | |

| 4.2. Targeted Optimization............................................................................................................. | 25 | |

| 4.3. Vector Arithmetic................................................................................................................. | 27 | |

| 5. | Applications | 29 |

| 5.1. Improve Alignment................................................................................................................. | 29 | |

| 5.1.1. Safety and Reliability.............................................................................................. | 29 | |

| 5.1.2. Fairness and Bias................................................................................................... | 31 | |

| 5.1.3. Persona and Role.................................................................................................... | 33 | |

| 5.2. Improve Capability................................................................................................................ | 35 | |

| 5.2.1. Multilingualism..................................................................................................... | 35 | |

| 5.2.2. Knowledge Management................................................................................................ | 37 | |

| 5.2.3. Logic and Reasoning................................................................................................. | 39 | |

| 5.3. Improve Efficiency................................................................................................................ | 41 | |

| 5.3.1. Efficient Training.................................................................................................. | 41 | |

| 5.3.2. Efficient Inference................................................................................................. | 43 | |

| 6. | Challenges and Future Directions | 44 |

| 7. | Conclusions | 46 |

| A. | Summary of Surveyed Papers | 47 |

| B. | References | 52 |

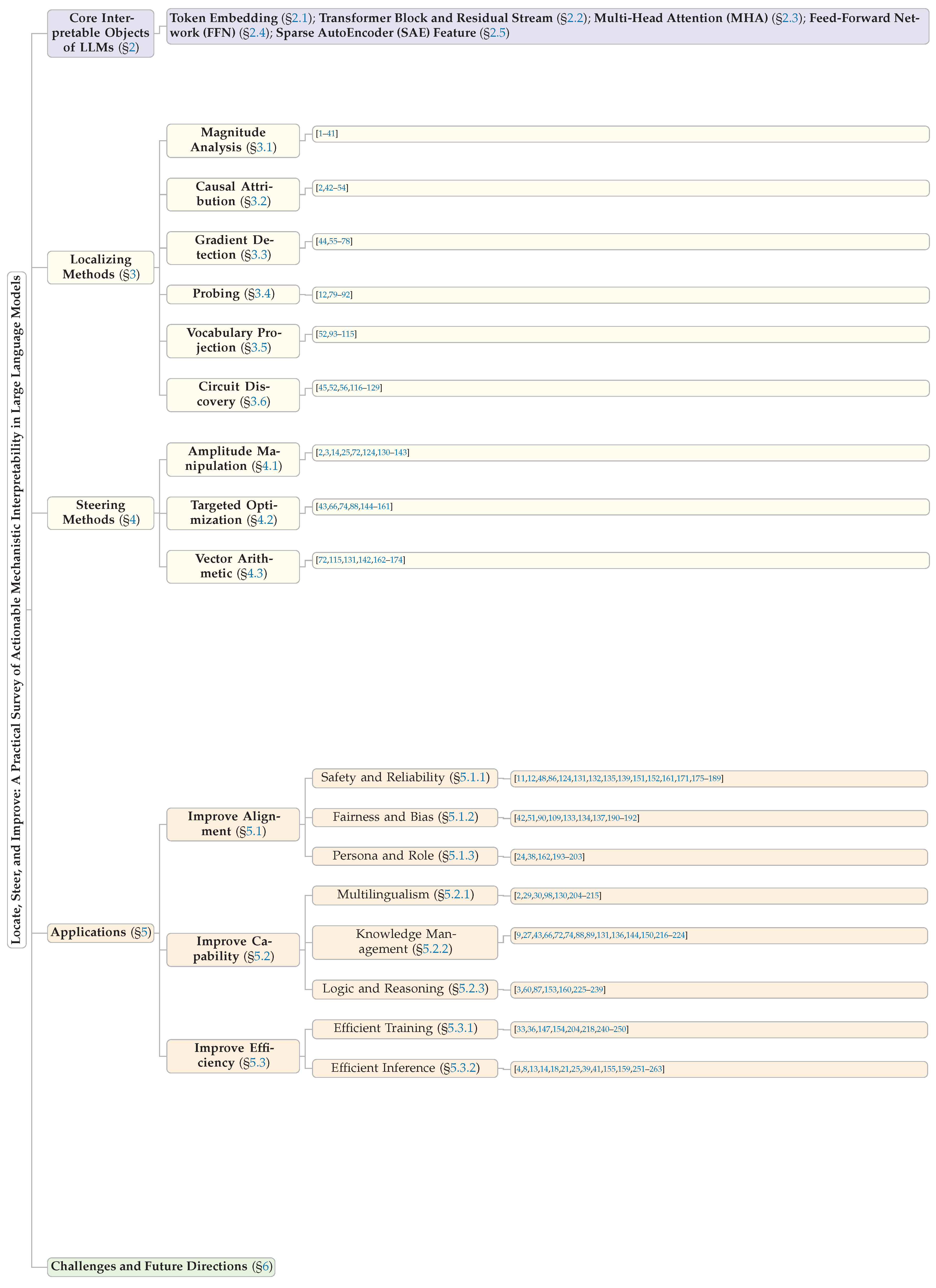

Paper Outline

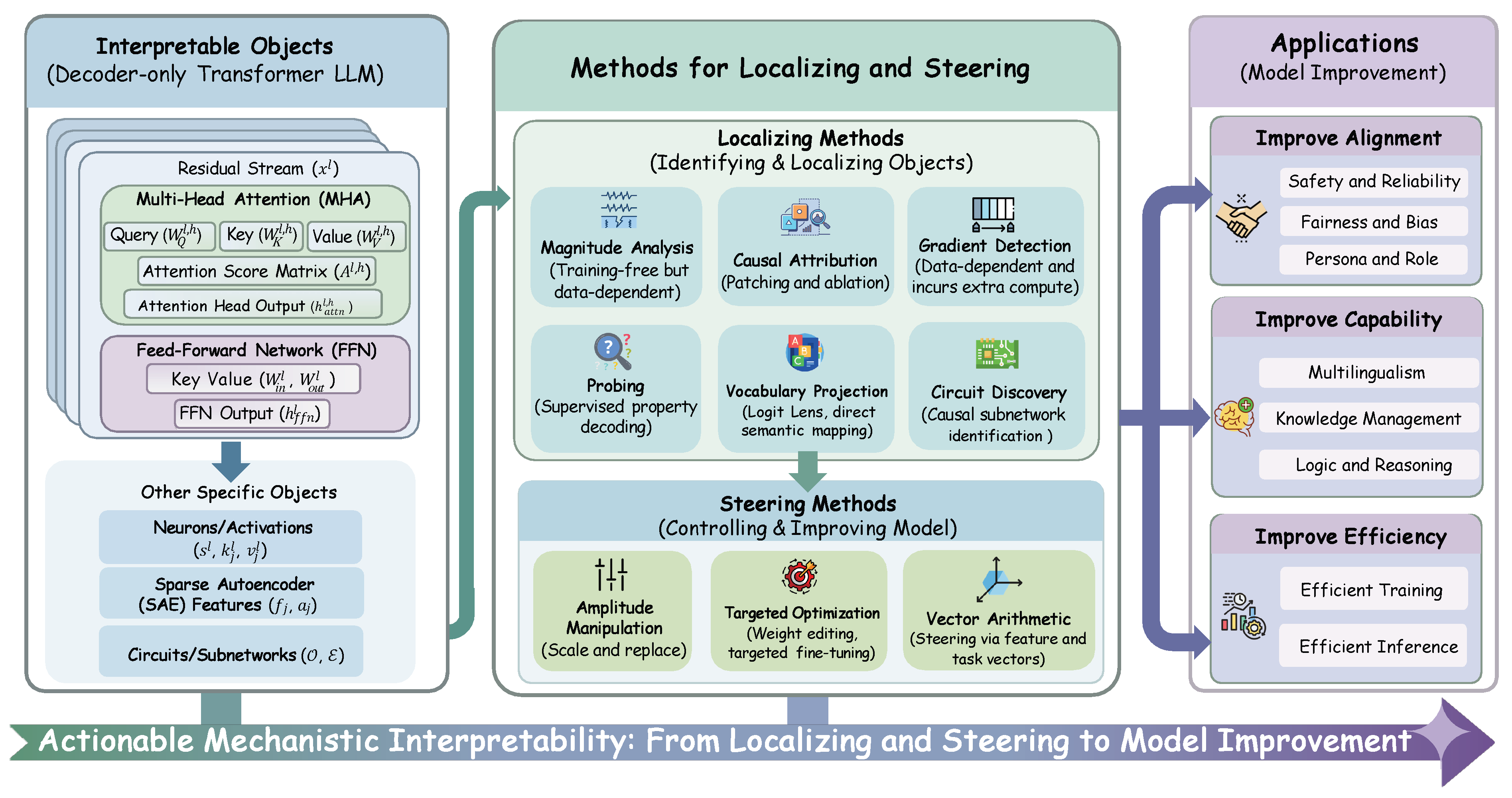

1. Introduction

- 1) A Rigorous Pipeline-Driven Framework: We establish a structured framework for applying MI to real-world model optimization. We begin by defining the core Interpretable Objects within LLMs (e.g., neurons, attention heads, residual streams). Based on the application workflow, we clearly categorize methodologies into two distinct stages: Localizing (Diagnosis), which identifies the causal components responsible for specific behaviors, and Steering (Intervention), which actively manipulates these components to alter model outputs. Crucially, for each technique, we provide a detailed Methodological Formulation along with its Applicable Objects and Scope, helping readers quickly understand the technical implementation and appropriate use cases.

- 2) Comprehensive Paradigms for Application: We provide an extensive survey of MI applications organized around three major themes: Improve Alignment, Improve Capability, and Improve Efficiency. These themes cover eight specific scenarios, ranging from safety and multilingualism to efficient training. Instead of merely listing relevant papers, we summarize representative MI application paradigms for each scenario. This approach allows readers to quickly capture the distinct usage patterns of MI techniques across different application contexts, facilitating the transfer of methods to new problems.

- 3) Insights, Resources, and Future Directions: We critically discuss the current challenges in actionable MI research and outline promising future directions. To facilitate further progress and lower the barrier to entry, we curate a comprehensive collection of over 200 papers, which are listed in Table 2. These papers are systematically tagged according to their corresponding localizing and steering methods, providing a practical and navigable reference for the community.

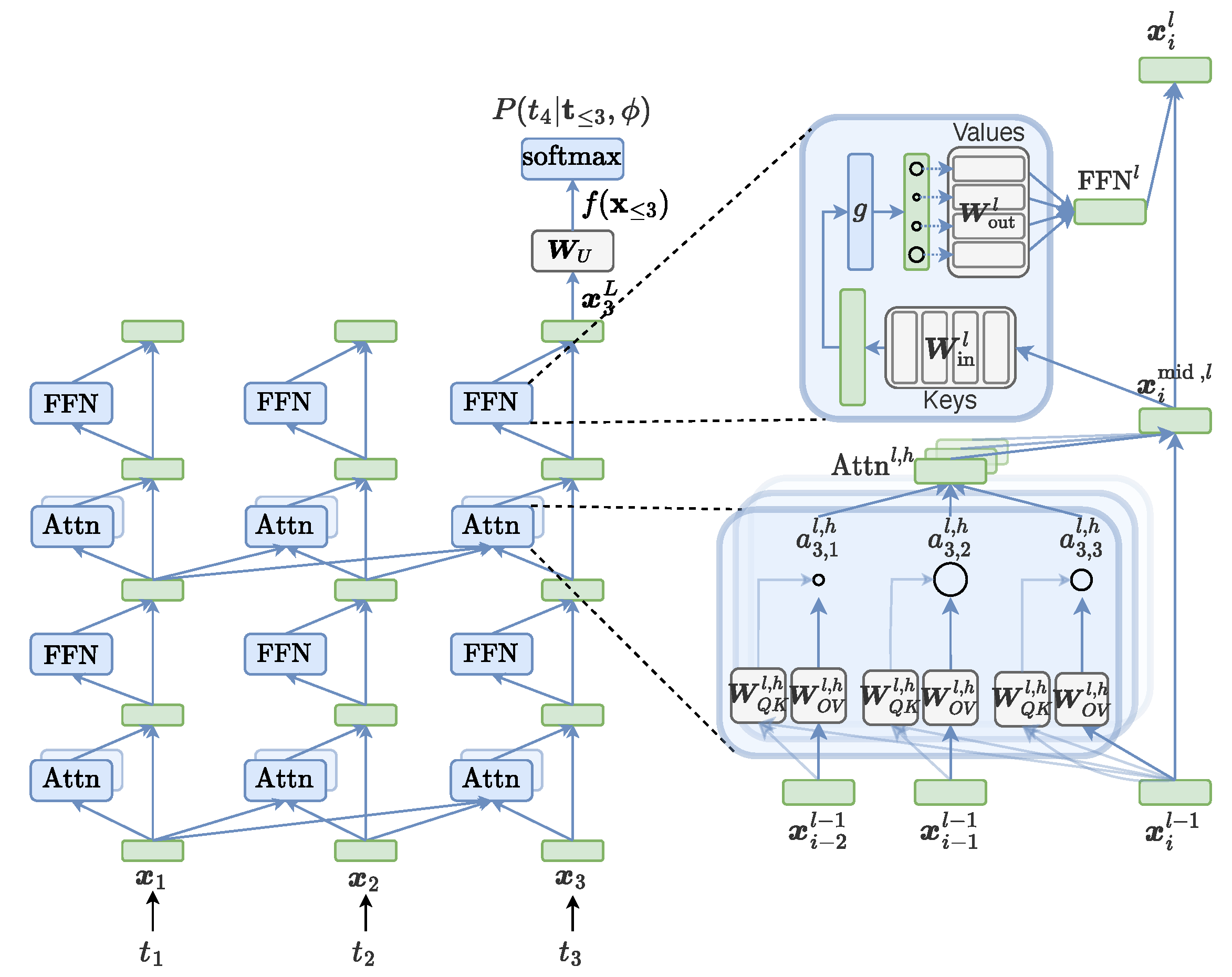

2. Core Interpretable Objects of LLMs

2.1. Token Embedding

2.2. Transformer Block and Residual Stream

2.3. Multi-Head Attention (MHA)

Standard Formulation

Mechanistic View: QK and OV Units

2.4. Feed-Forward Network (FFN)

Standard Formulation

Mechanistic View: Neurons

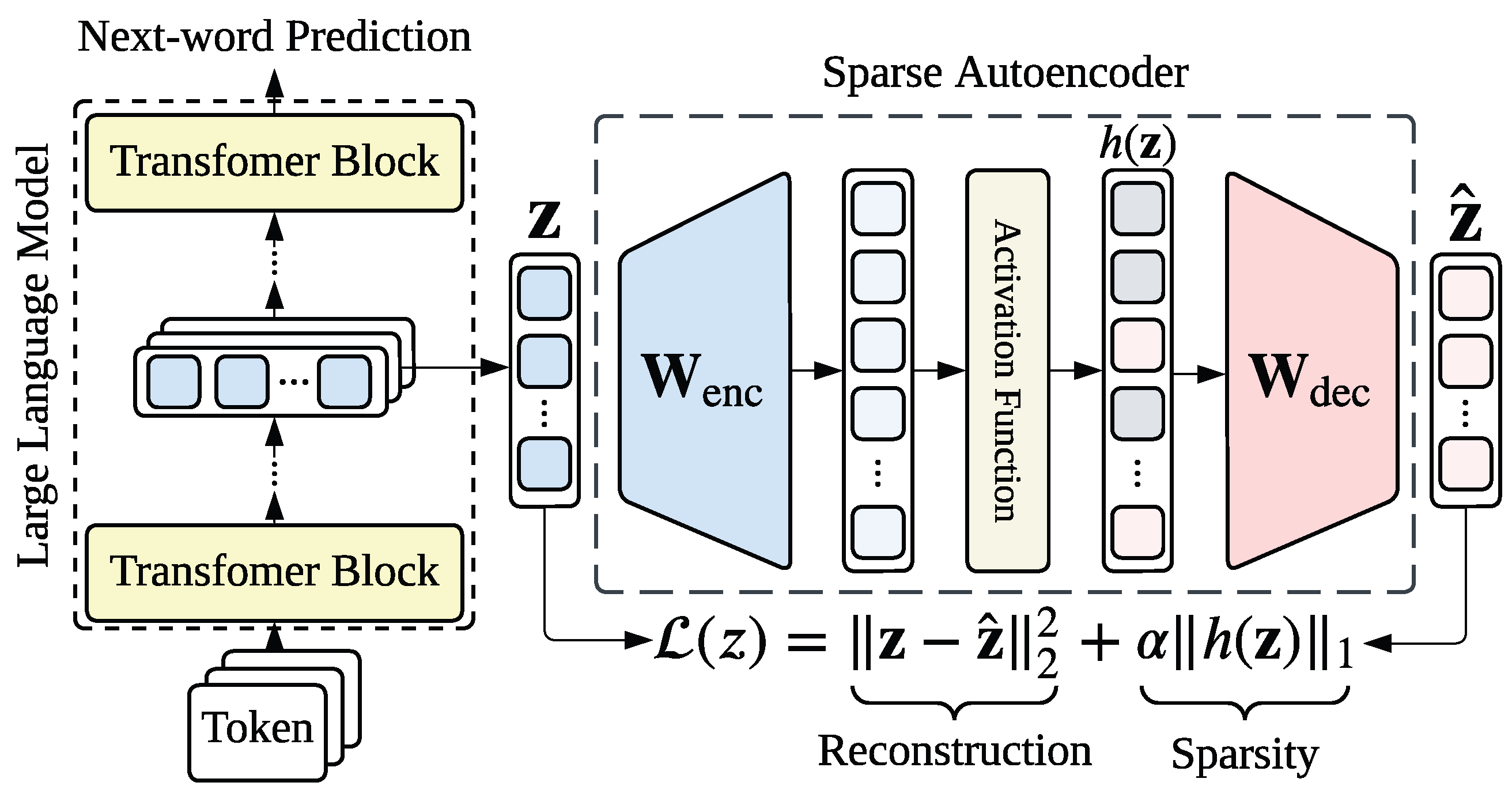

2.5. Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) Feature

Mathematical Formulation

Training Challenges and Resources

3. Localizing Methods

3.1. Magnitude Analysis

Methodological Formulation

Applicable Objects

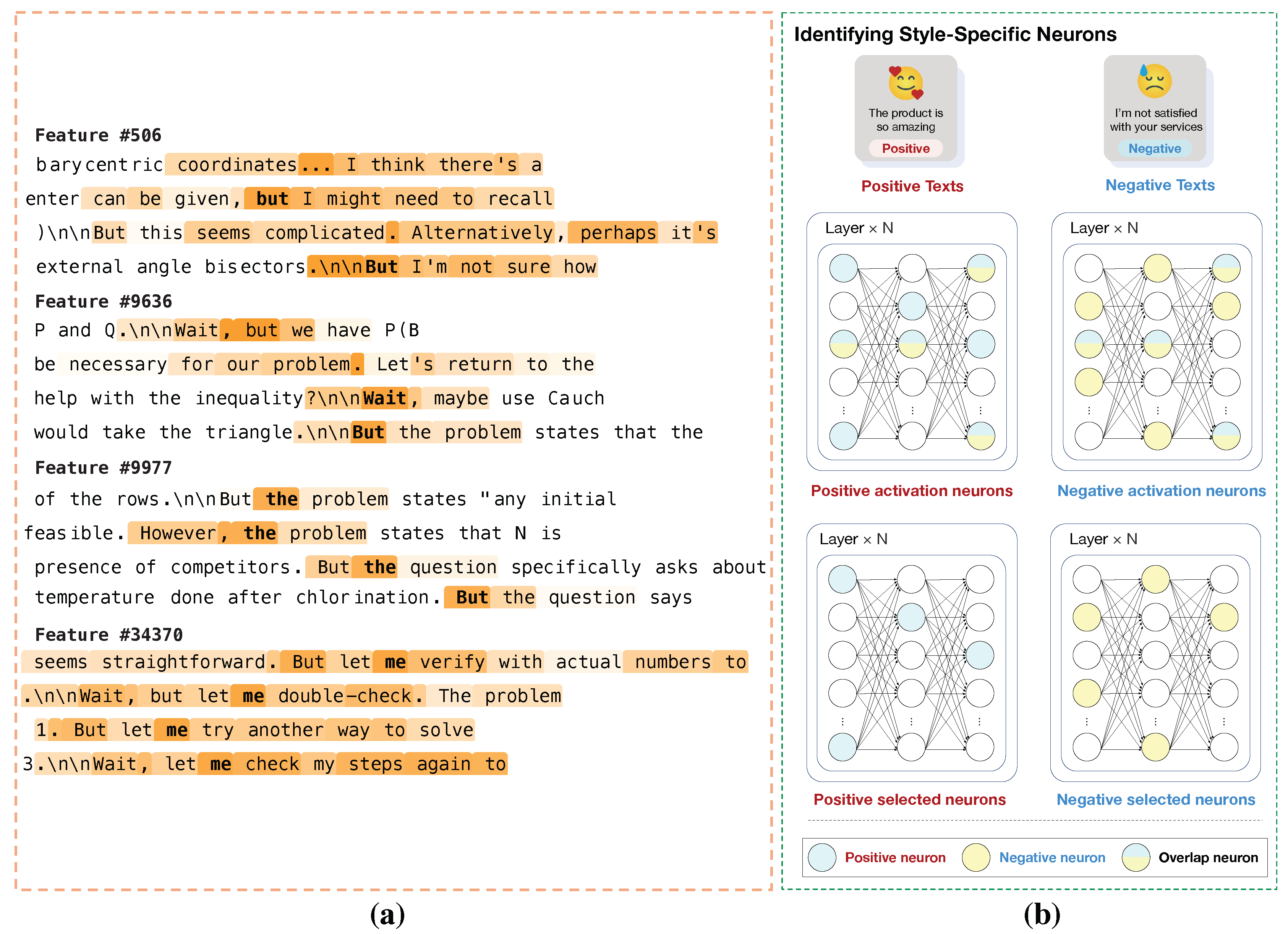

- Specialized Neurons and SAE Features: By feeding domain-specific datasets into the model and monitoring activations (e,g., neuron activation state or SAE feature activation state ), researchers can isolate components dedicated to specific concepts. For instance, in the context of higher-level reasoning, Galichin et al. [3] utilized SAEs to disentangle the residual stream state . As shown in Figure 4 (a), they proposed a metric called ReasonScore, which aggregates the activation frequency and magnitude of SAE features specifically during “reasoning moments” (e.g., when the model meets tokens like “Wait or “Therefore”). By ranking features based on this score, they successfully localized Reasoning-Relevant SAE features that encode abstract concepts like uncertainty or exploratory thinking. Similarly, for style transfer, Lai et al. [24] employed Magnitude Analysis to identify Style-Specific Neurons. As illustrated in Figure 4 (b), they calculated the average activation magnitude of FFN neurons across corpora with distinct styles (e.g., positive vs. negative). Neurons that exhibited significantly higher average activation for the source style compared to the target style were identified as “Source-Style Neurons,” serving as candidates for subsequent deactivation.

- Attention Heads: The magnitude and distribution of attention scores () serve as a direct indicator of a head’s functional role [10,31,32,33,34,35,36]. For instance, Zhou et al. [35] introduced the Safety Head ImPortant Score (Ships), which aggregates attention weights on refusal-related tokens to localize “Safety Heads” critical for model alignment. In the multimodal domain, Sergeev and Kotelnikov [36] and Bi et al. [10] measured the concentration of attention mass on image tokens versus text tokens, successfully pinpointing heads responsible for visual perception and cross-modal processing. Similarly, Singh et al. [33] measured “induction strength”—derived from the attention probability assigned to token repetition patterns—to track the formation and importance of Induction Heads.

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages: It does not require training auxiliary classifiers or performing computationally expensive backward passes. This makes it highly scalable and suitable for analyzing large models in real-time.

- Limitations: It serves primarily as a lightweight heuristic. High activation magnitude implies high presence but does not guarantee causal necessity (e.g., a high-magnitude feature might be cancelled out by a subsequent layer). Furthermore, its success relies heavily on the quality of the input data; if the dataset fails to elicit the specific behavior, the relevant components will remain dormant. Therefore, Magnitude Analysis is typically used as a “first-pass" screening tool to filter candidate objects for more rigorous verification methods.

3.2. Causal Attribution

Methodological Formulation

Applicable Objects

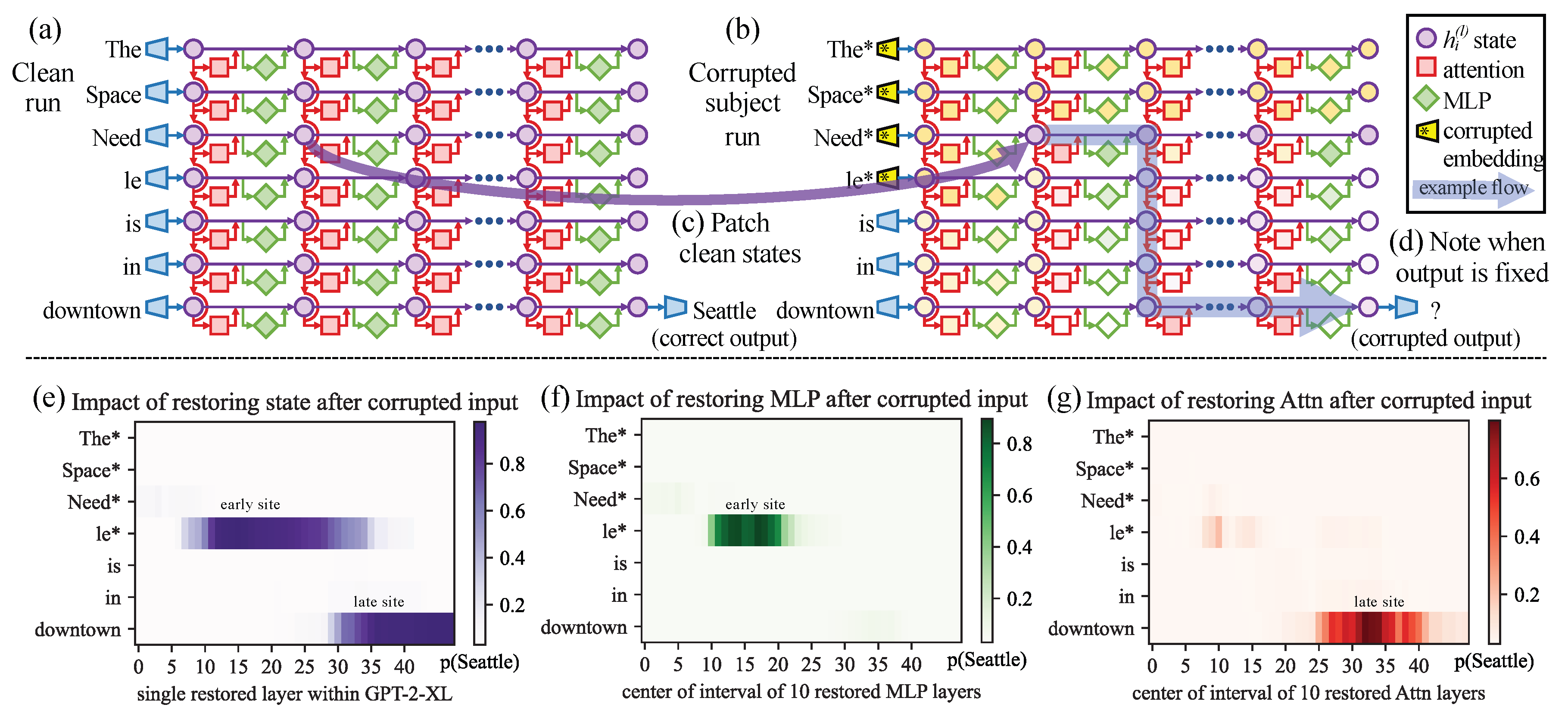

- Corrupted Run (Intervention): First, the specific knowledge is erased from the model’s computation. A corrupted input is created by adding Gaussian noise to the embeddings of the subject tokens (e.g., “Space Needle”), causing the probability of the correct prediction (“Seattle”) to drop significantly.

- Patched Run (Restoration): The core operation systematically restores specific internal states. For a specific layer l and token position i, the method copies the hidden activation from a separate original clean run and pastes (restores) it into the corrupted computation graph.

- Effect Measurement: The causal effect is quantified by the Indirect Effect (IE), which measures how much of the original target probability is recovered by this restoration. A high IE score implies that the patched state at carries critical information.

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages: Unlike Magnitude Analysis (§3.1), which only establish correlation, Causal Attribution provides definitive evidence that a component is a functional driver of the model’s output. This allows researchers to distinguish essential mechanisms from features that are highly activated but causally irrelevant to the specific behavior.

- Limitations: This rigor incurs a significant computational overhead. Verifying causality typically requires intervening on objects individually and performing a separate forward pass for each intervention. Consequently, the cost scales linearly with the number of objects analyzed, making it prohibitively expensive for dense, sweeping searches over large models. This inefficiency often necessitates the use of Gradient Detection (§3.3), which utilizes gradients to rapidly approximate these causal effects, enabling efficient screening before performing expensive, fine-grained interventions.

3.3. Gradient Detection

Methodological Formulation

Applicable Objects

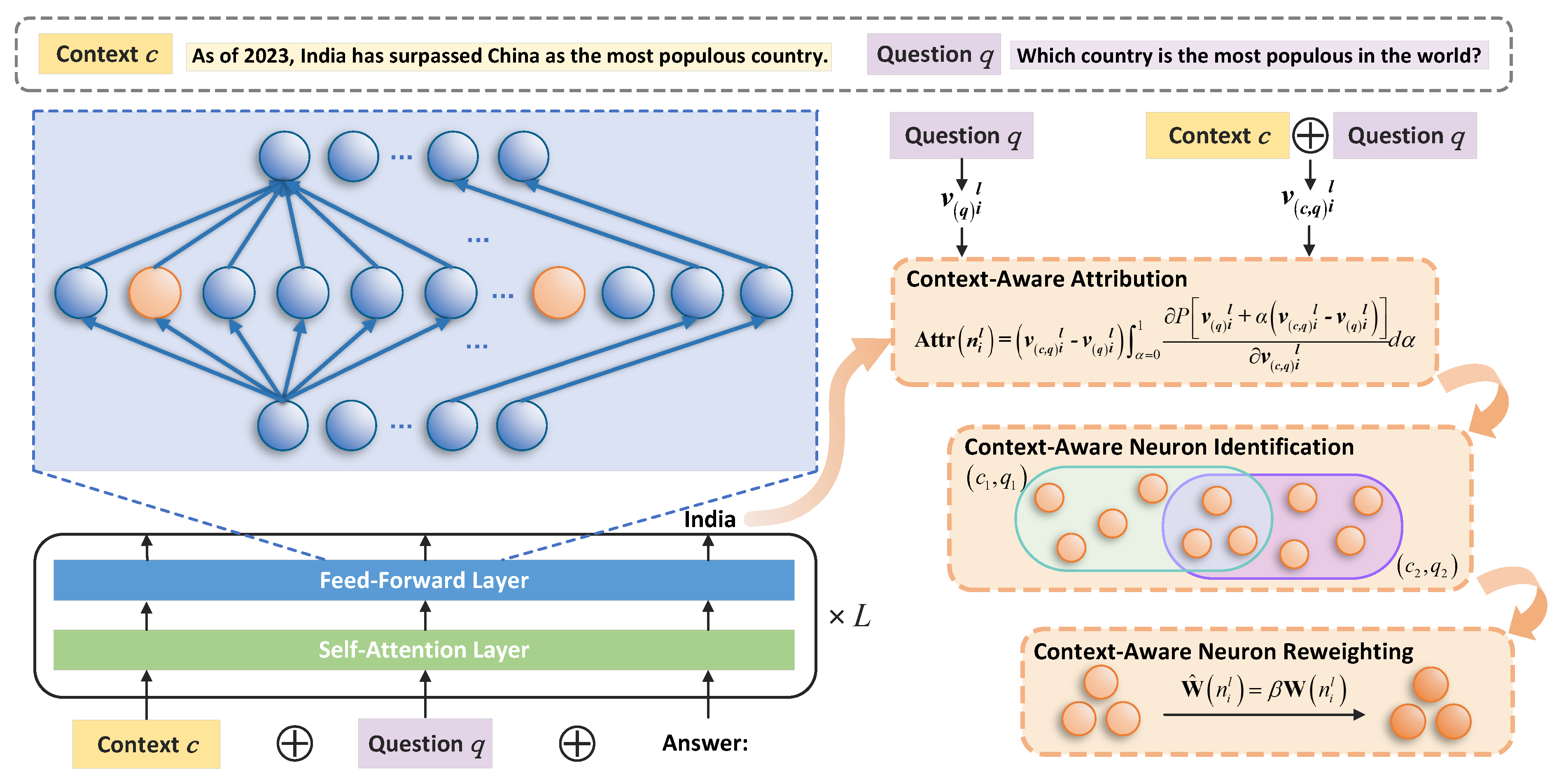

- Neurons (): A standard neuron-level object is the FFN activation vector at layer l. Gradients can be converted into per-neuron scores to rank neurons by their local influence on F. This has been used to localize knowledge- or context-sensitive neurons and analyze their dependencies [64,65,66,67,68,69]. Figure 6 illustrates a concrete LLM-specific instance: Shi et al. [65] computes Integrated Gradients scores to identify neurons most responsible for processing contextual cues under knowledge conflicts (via a context-aware attribution and a high-score intersection criterion), and then reweights the identified neurons to promote context-consistent generation.

- Attention Head Outputs ():Gradient Detection also applies to attention-related activations such as the attention head output . Computing and scalarizing it with yields head-level rankings that can highlight salient heads or attention submodules for further analysis and subsequent intervention [70,71,72].

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages:Gradient Detection is applicable to a broad class of objects without requiring additional training. Compared with exhaustive interventions, it can produce rankings with a relatively small number of backward passes, making it practical as an initial localization step when the candidate set is large.

- Limitations: Gradients provide a local proxy, not causal necessity: salience can be offset by downstream computation, and finite interventions may depart from first-order effects in non-linear regimes. For these reasons, gradient-ranked objects are typically paired with Causal Attribution (§3.2) to validate whether the identified objects are genuinely responsible for the target behavior.

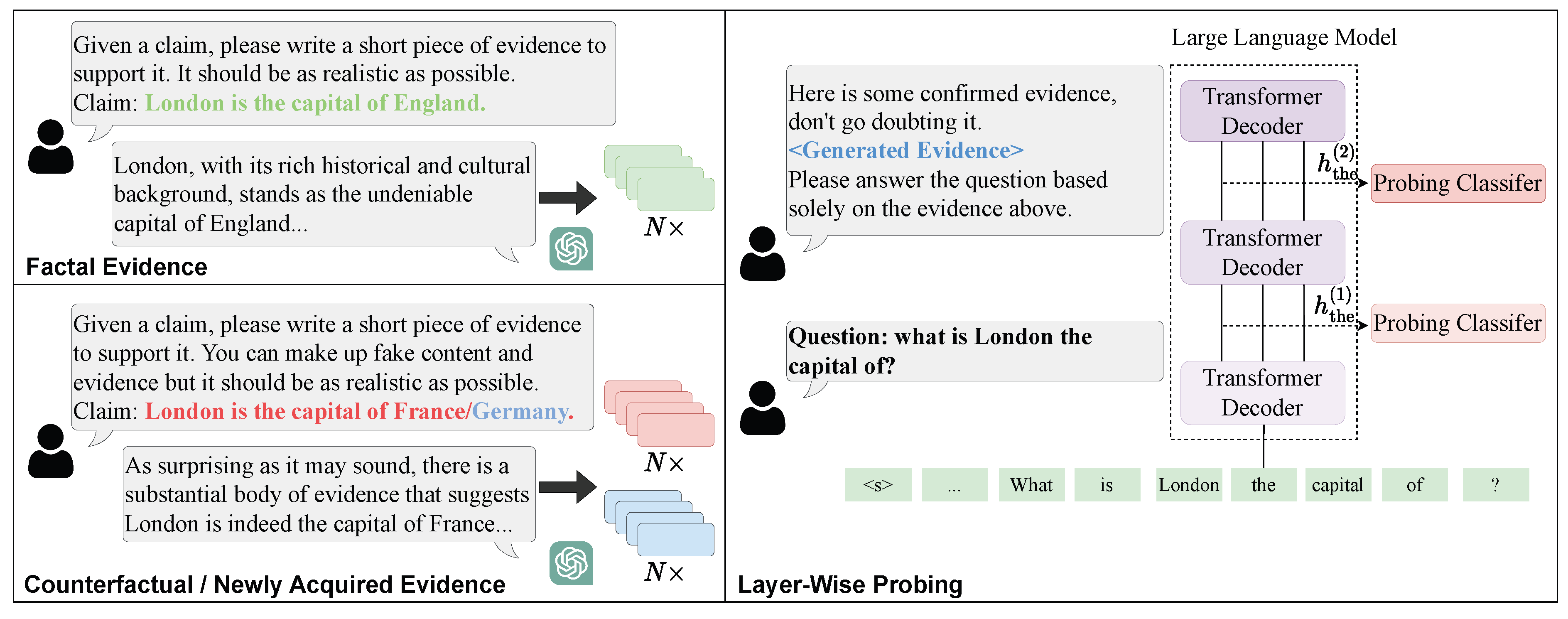

3.4. Probing

Methodological Formulation

Applicable Objects

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages: With a fixed probe family, Probing enables standardized comparisons across objects, supporting efficient layer-wise tracking and large-scale ranking of candidate modules. Simple probes (e.g., linear) are lightweight and interpretable, allowing broad sweeps while keeping the LLM frozen.

- Limitations: Decodability is not causality: high probe accuracy does not imply the model uses y, nor that the probed object is necessary or sufficient. Results are sensitive to dataset and design choices (e.g., labeling, token positions), so controls and follow-up causal tests are typically required for functional claims.

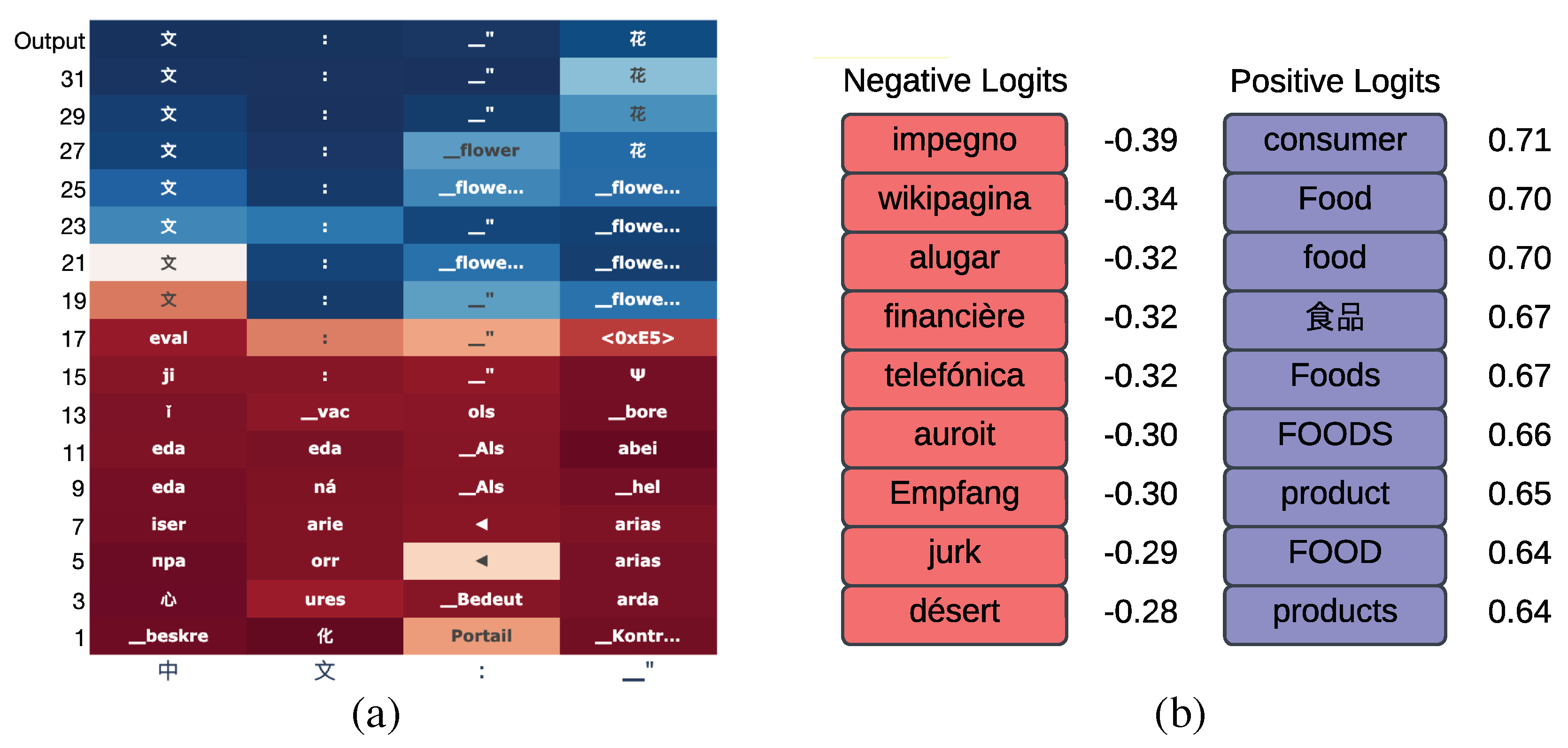

3.5. Vocabulary Projection

Methodological Formulation

Applicable Objects

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages: It provides a zero-shot interpretation method that is computationally efficient and intuitive. Unlike Probing (§3.4), it does not require collecting a labeled dataset or training a separate classifier, allowing for immediate inspection of any model state.

- Limitations: The primary limitation is the assumption that intermediate states exist in the same vector space as the output vocabulary (basis alignment). While this often holds for the residual stream due to the residual connection structure, it may be less accurate for components inside sub-layers (like FFN and MHA) or in models where the representation space rotates significantly across layers. Consequently, results should be interpreted as an approximation of the information that is linearly decodable by the final layer.

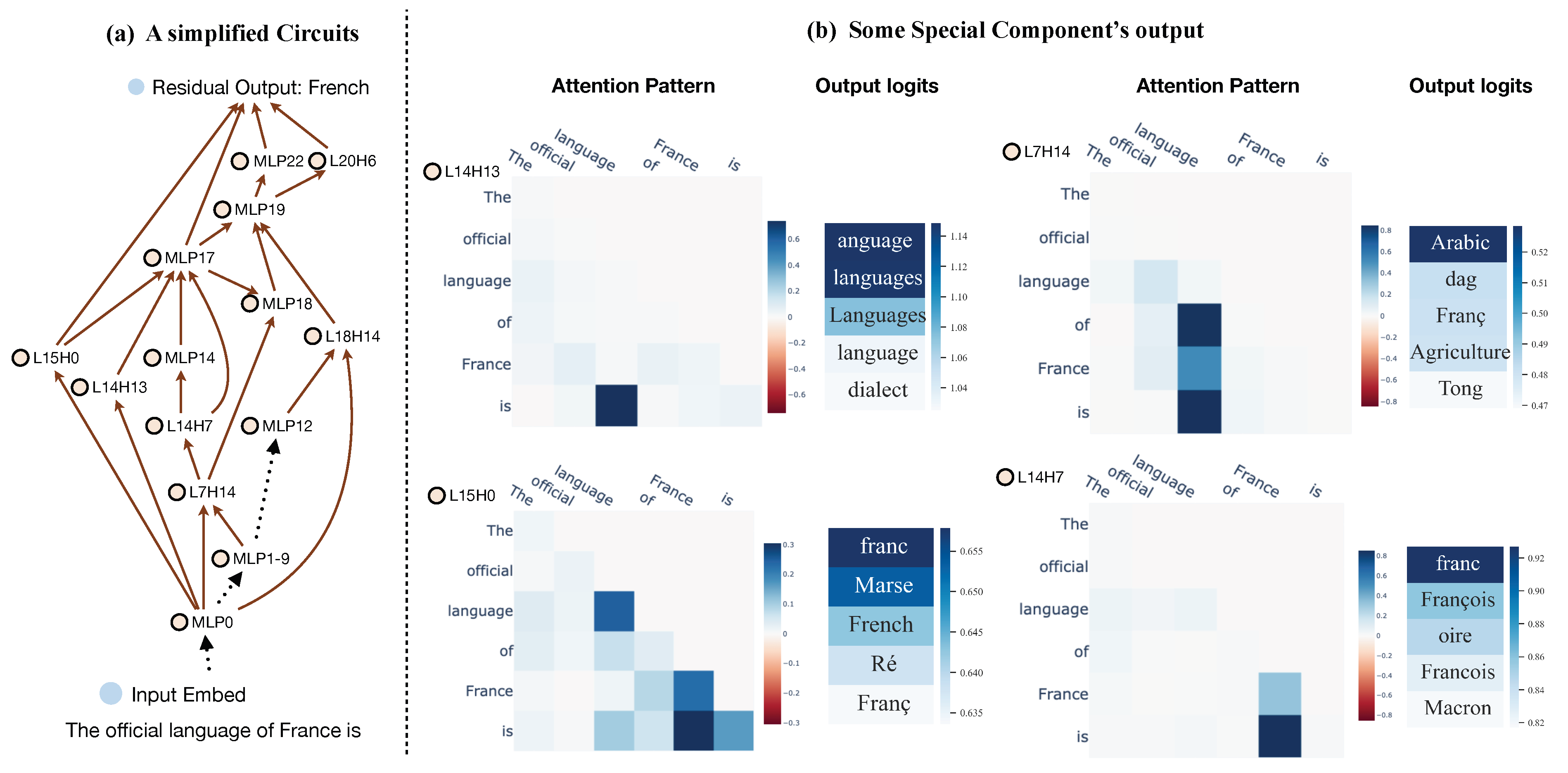

3.6. Circuit Discovery

Methodological Formulation

Applicable Objects

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages:Circuit Discovery yields mechanistically structured explanations: selecting edges reveals how multiple objects compose a computation and exposes cross-layer routing patterns that node-wise rankings can miss. This aligns with transformers’ residual-update structure, where heads and FFNs contribute additive edits that can be tracked as directed dependencies. Attribution-based edge scoring also enables scalable screening of large edge sets when exhaustive interventions are infeasible.

- Limitations: Circuits are defined relative to a specific behavior, metric , and contrast (clean vs. corrupted), so results are often objective- and dataset-dependent. Because attribution scores approximate intervention effects, they may miss non-linear interactions, so rankings are best treated as proposals and typically require intervention-based validation on the retained subgraph.

4. Steering Methods

4.1. Amplitude Manipulation

Methodological Formulation

- Ablation or Patching: Here, the object is suppressed or replaced, i.e., . Setting (Zeroing) or (Mean centering) removes the component’s influence, while (Patching) injects information from a different context.

- Scaling: Here, the activation strength is adjusted via a scalar coefficient , such that . This allows for continuous amplification () or attenuation () of a specific feature’s downstream impact.

Applicable Objects

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages: It is an optimization-free and reversible intervention. It allows for “surgical” edits to model behavior (e.g., removing specific biases) by simply masking or scaling activations during inference. This makes it highly flexible and suitable for real-time control.

- Limitations: It relies heavily on the accurate localization of the target components. If the features responsible for a behavior are not perfectly disentangled (i.e., polysemantic), ablating or scaling them may cause unintended side effects or degrade general performance. Furthermore, finding the optimal scaling factor often requires empirical tuning.

4.2. Targeted Optimization

Methodological Formulation

Applicable Objects

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages: It offers strong precision, controllability, and persistence. The desired behavioral change is directly encoded in a target objective, and localization helps minimize interference with unrelated competencies. Consequently, it is well-suited for targeted factual rewrites, controlled specialization, and safety-preserving adaptation where lasting changes are required.

- Limitations: Its reliability hinges on correct localization and well-specified supervision. If the chosen subset does not capture the causal mechanism, optimization may underachieve the intended target behavior, shift the behavior to other objects, or yield brittle side effects. In practice, success often requires carefully constructed target/preservation data and robust criteria for selecting the localized update region.

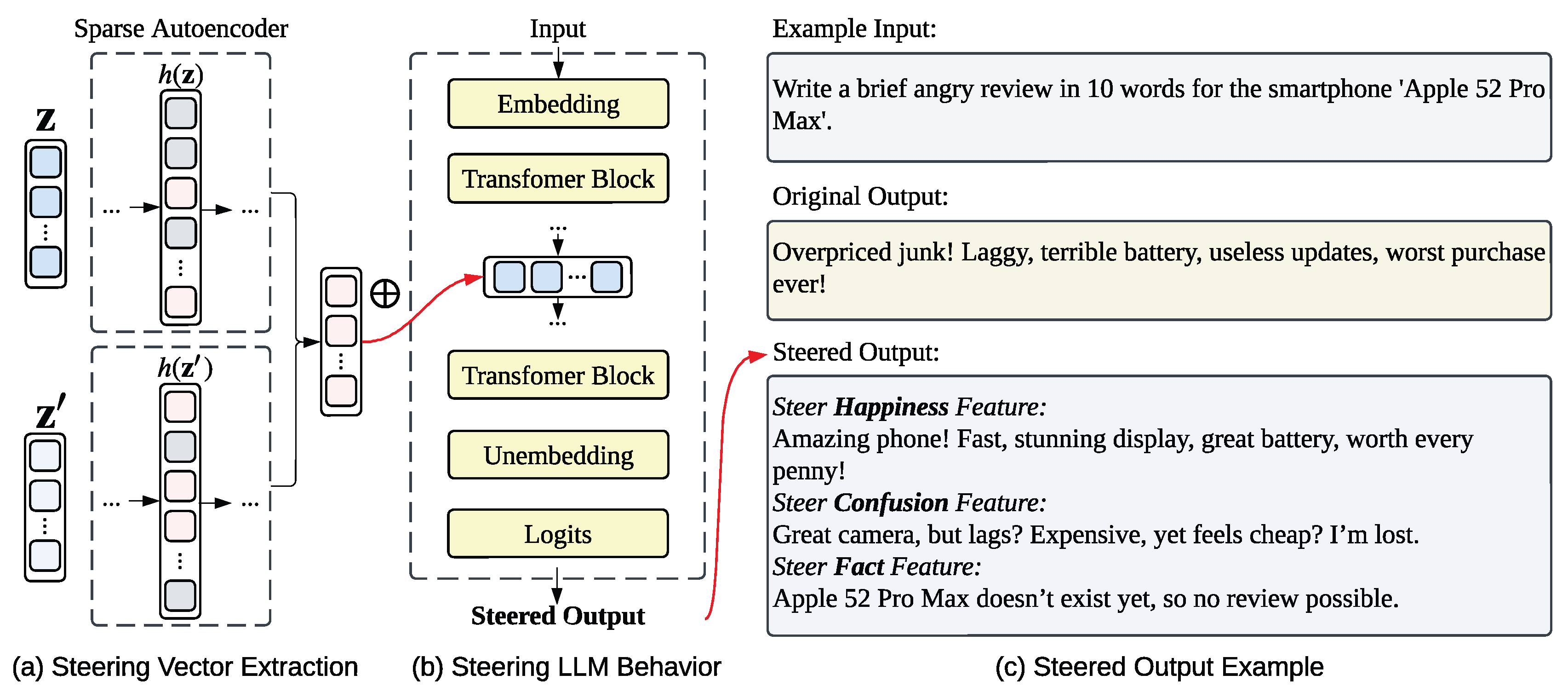

4.3. Vector Arithmetic

Methodological Formulation

Applicable Objects

-

Contrastive Activation Means: This method, often referred to as “Activation Addition” or “Mass-Mean Shift,” assumes that a concept can be isolated by comparing the model’s internal states across opposing contexts [162,163,164,165,166,167]. Formally, let be a set of prompts eliciting the target behavior and be a set eliciting the opposing behavior. The steering vector is calculated as the difference between the centroids of the residual stream states for these two sets:By adding to the residual stream, we shift the model’s current state towards the centroid of the positive behavior.

-

SAE Features: SAEs offer a more precise way to derive by utilizing monosemantic features [131,168,169,170,171,172]. As illustrated in Figure 12, the process involves two steps:

- Feature Identification: First, we collect residual stream states from a positive dataset (eliciting the target concept, e.g., “Happiness”) and a negative/neutral dataset . By passing these states through the SAE encoder, we calculate the differential activation score for each feature j:where denotes the j-th feature activation for input . Features with high positive constitute the set of “Target Features” that specifically encode the desired trait.

- Vector Construction: The steering vector is then synthesized as the weighted sum of these identified feature. Let denote the j-th feature (the j-th column of the SAE decoder weights ). The steering vector is computed as:

Finally, this obtained steering vector is injected into the model’s residual stream during inference (). As shown in Figure 12 (c), this enables precise manipulation of specific semantic traits like “Happiness” or “Confusion” to drastically alter generation styles while minimizing interference with unrelated concepts.

Characteristics and Scope

- Advantages: It is a lightweight and reversible intervention. Since it typically operates at inference time (for hidden states) or via simple weight addition, it does not require complex optimization or gradient descent during deployment. It allows for flexible control over model behavior by simply adjusting the steering coefficient .

- Limitations: The effectiveness relies on the “Linear Representation Hypothesis.” If the target concept is not encoded linearly or if the steering vector is entangled with other concepts (which is common with “Contrastive Activation Means”), the intervention might introduce unintended side effects.

5. Applications

5.1. Improve Alignment

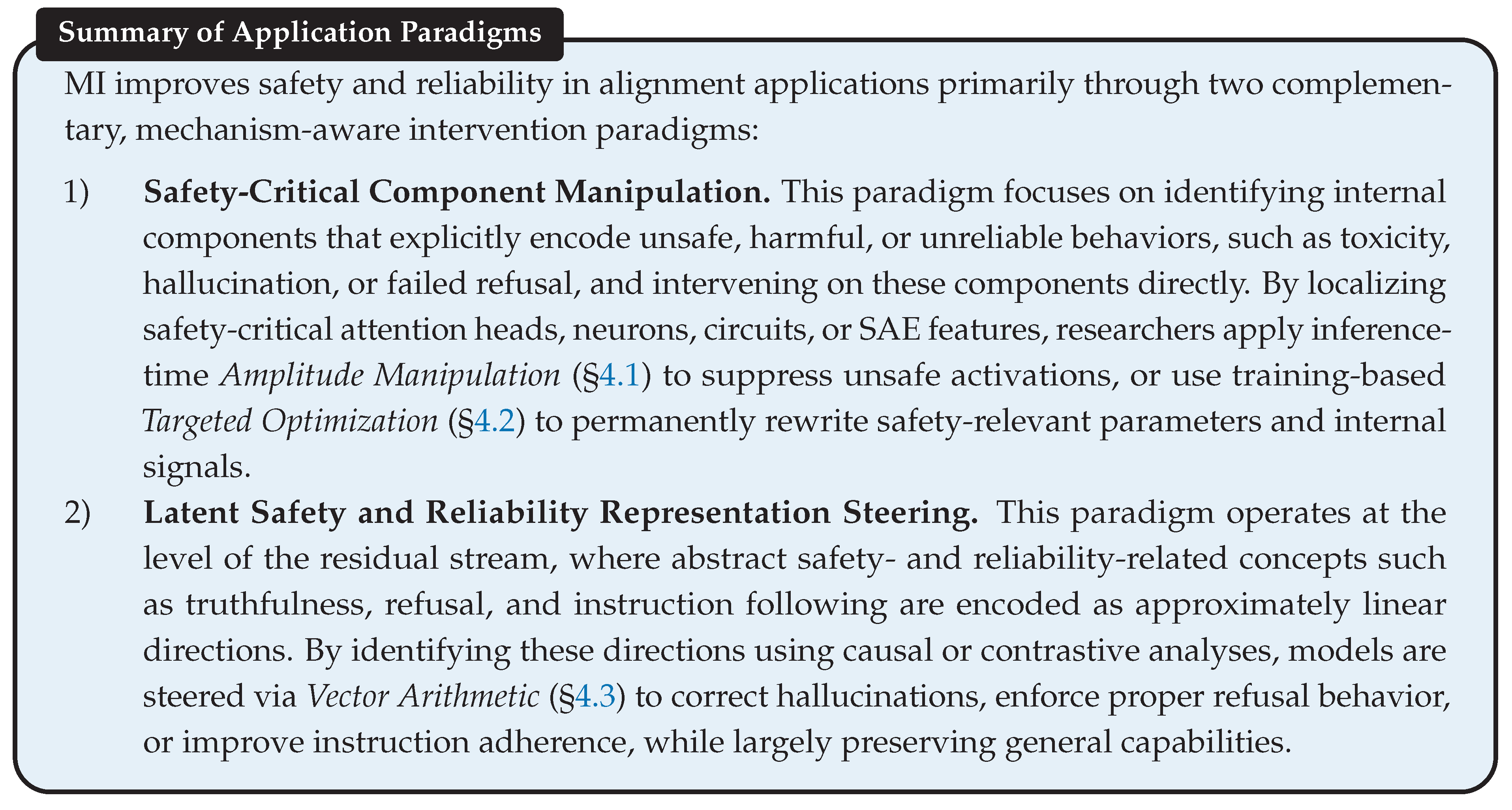

5.1.1. Safety and Reliability

1) Safety-Critical Component Manipulation

2) Latent Safety and Reliablity Representation Steering

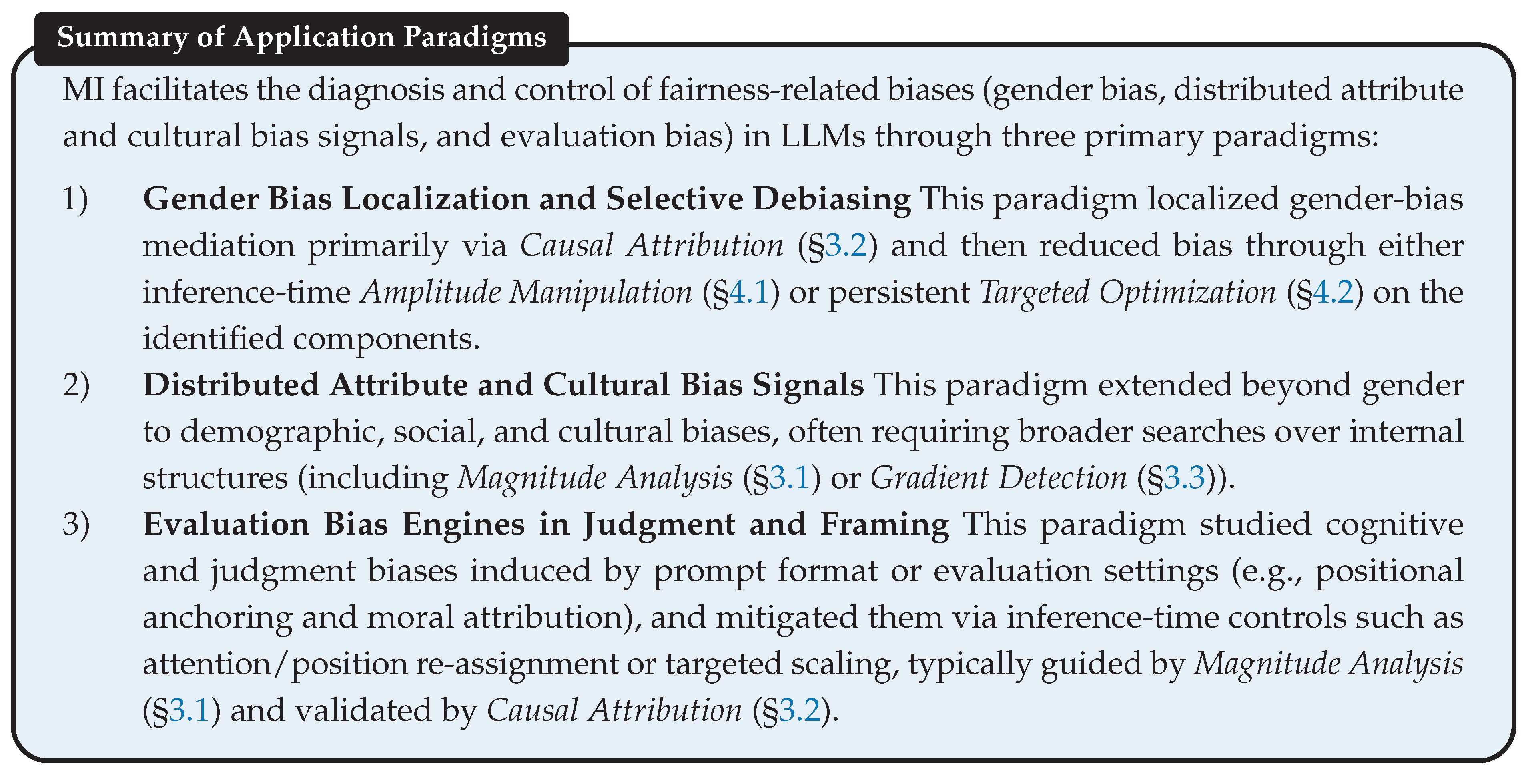

5.1.2. Fairness and Bias

1) Gender Bias Localization and Selective Debiasing

2) Distributed Attribute and Cultural Bias Signals

3) Evaluation Bias Engines in Judgment and Framing

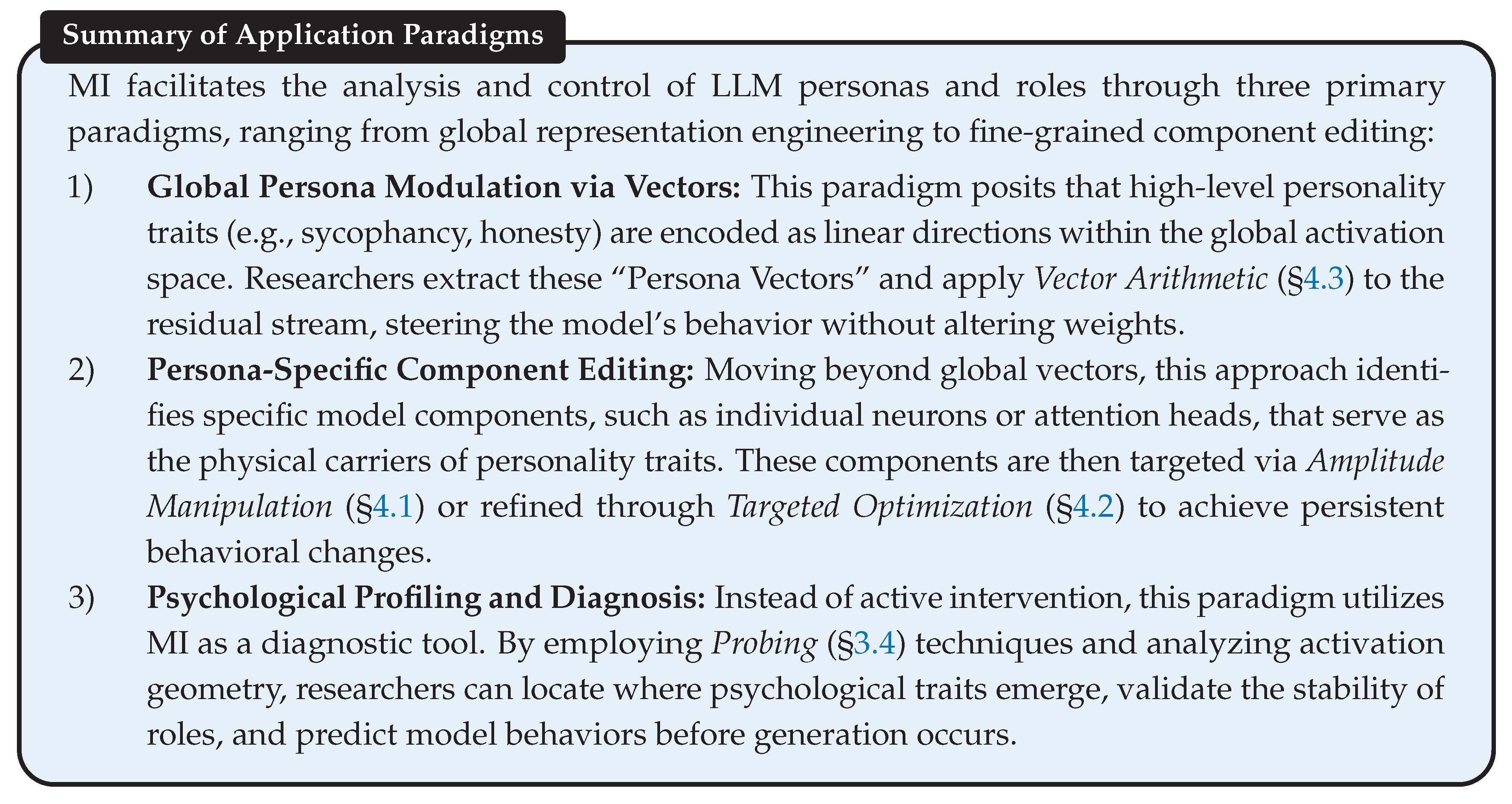

5.1.3. Persona and Role

1) Global Persona Modulation via Vectors

2) Persona-Specific Component Editing

3) Psychological Profiling and Diagnosis

5.2. Improve Capability

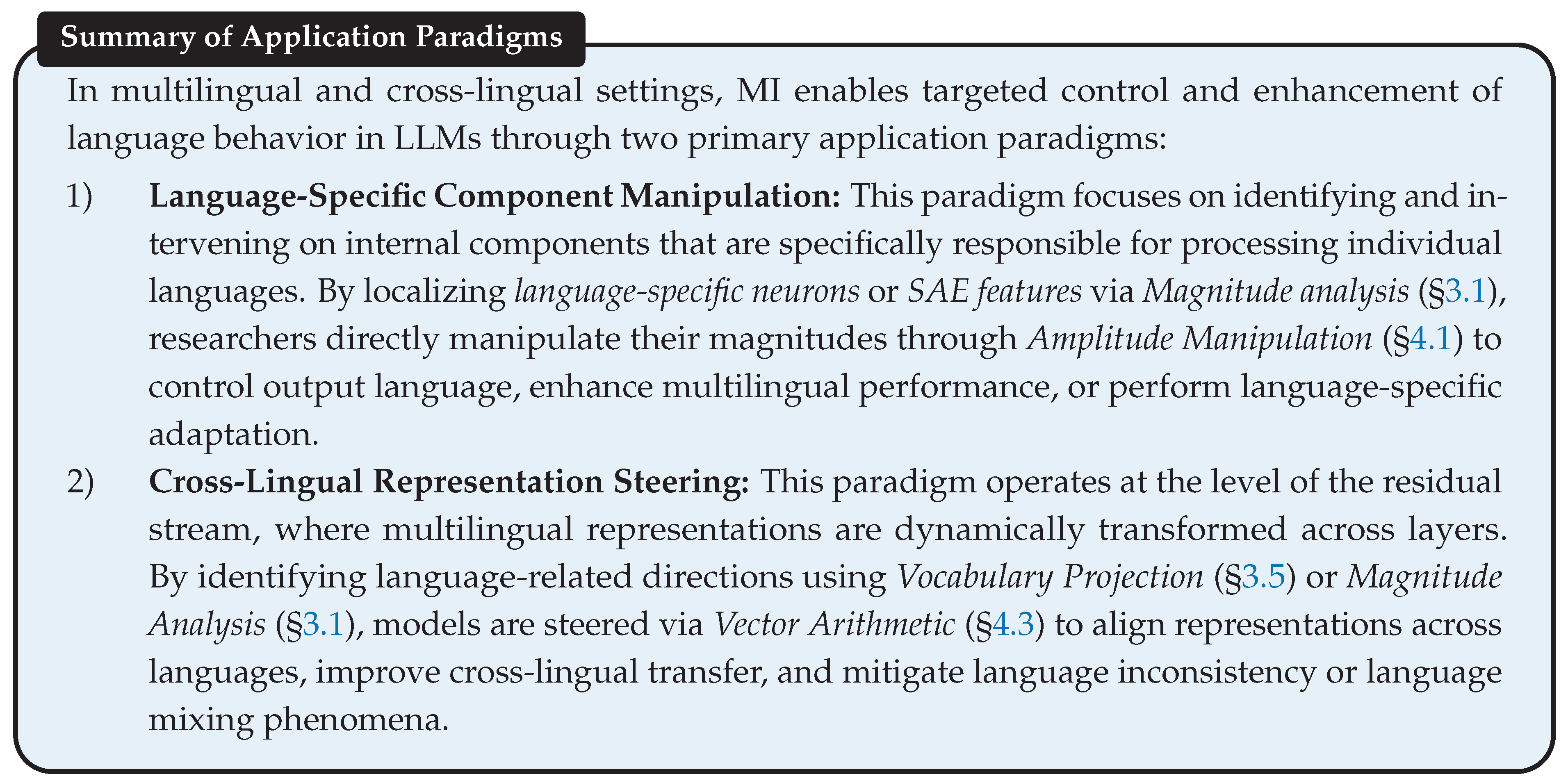

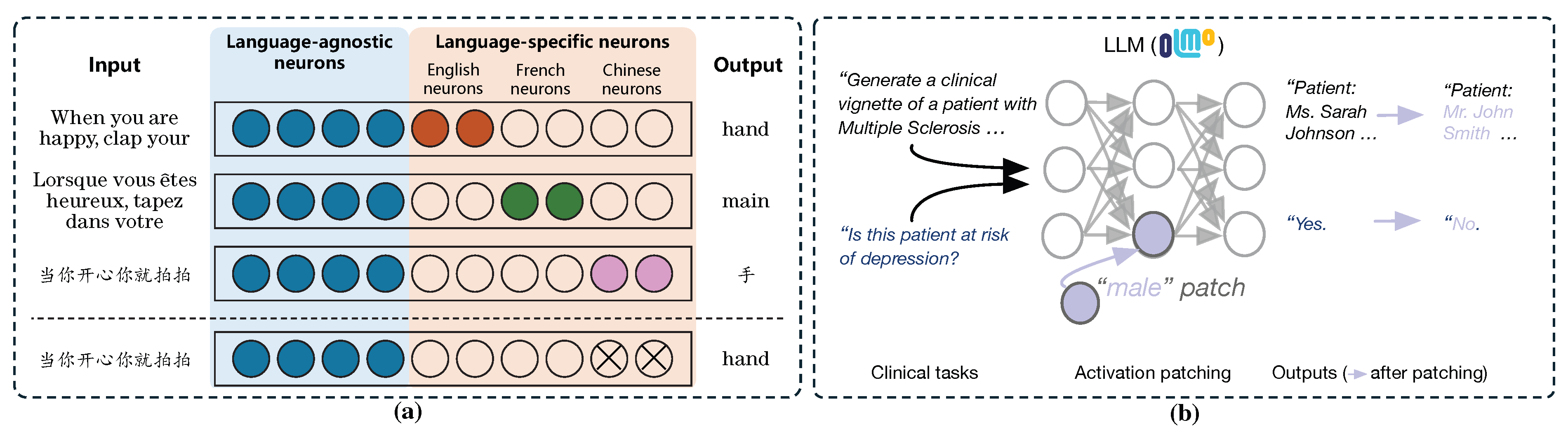

5.2.1. Multilingualism

1) Language-Specific Component Manipulation

2) Cross-Lingual Representation Steering in Residual Space

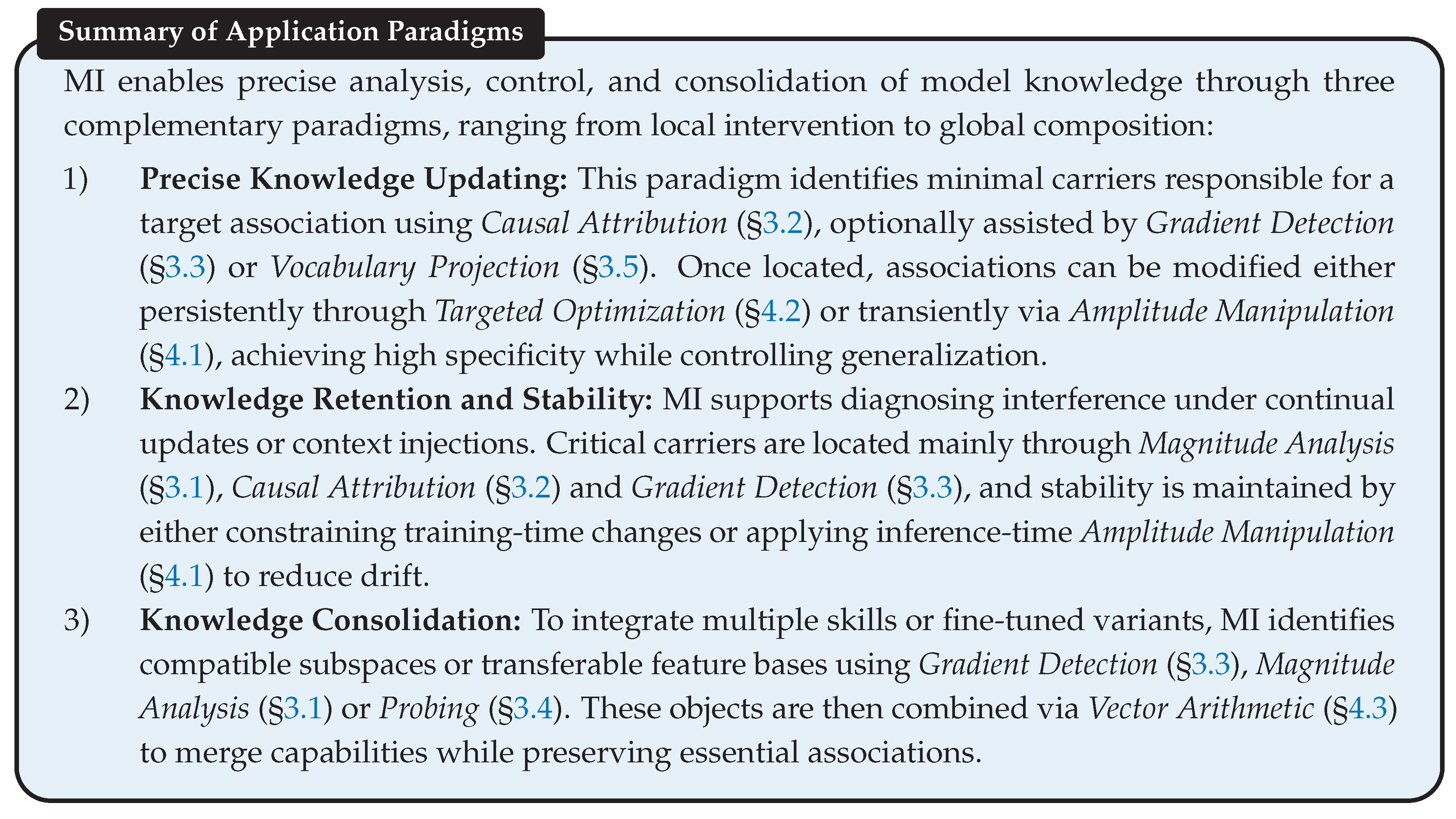

5.2.2. Knowledge Management

1) Precise Knowledge Updating

- Localized Parameter Rewriting: A core result is that many factual associations are mediated by localized pathways, often concentrated in mid-layer FFN output and neuron activation state . Meng et al. [43] used Causal Attribution to identify carriers responsible for factual recall and applied structured weight edits (on FFN matrices such as ) to rewrite specific associations, a process referred to as Targeted Optimization, providing a mechanistic alternative to diffuse fine-tuning. Scaling beyond single edits, Meng et al. [144] extended this paradigm to large edit batches by coordinating updates across multiple layers, demonstrating that persistent rewriting could remain localized while handling substantial edit volume. Subsequent work refined the localization premise: Chen et al. [216] argued that editability was frequently query-conditioned, motivating consistency-aware localization under a broader Query Localization assumption, rather than a fixed set of knowledge neurons. For long-form QA, Chen et al. [27] introduced QRNCA (a form of Causal Attribution), which yielded actionable neuron groups that better tracked query semantics. In multilingual settings, Zhang et al. [150] identified language-agnostic factual neurons via Magnitude Anaylysis and applied Targeted Optimization on these shared neurons to improve cross-lingual edit consistency. In backward propagation, Katz et al. [217] complemented forward analyses with Vocabulary Projection of backward-pass gradients, offering an orthogonal diagnostic on where learning signals concentrated during updates.

- Activation-Space Editing and Unlearning: When persistent rewrites are undesirable (e.g., reversible control or safety-motivated removal), activation-level interventions on residual stream states at layer l, or on head/feature activations, provide a practical alternative. Lai et al. [218] jointly localized and edited attention-head computations (intervening on attention head output ) through gated activation control, instantiating a targeted form of Targeted Optimization. SAE-based approaches decomposed residual stream states into sparse features with activations , enabling feature-level interventions: Muhamed et al. [219] proposed dynamic SAE guardrails that selected and scaled relevant features via Magnitude Analysis to achieve precision unlearning with improved forget–utility trade-offs, while Goyal et al. [131] applied Amplitude Manipulation to steer toxicity-related SAE features (scaling selected via their activations ) to reduce harmful generations with controlled fluency impact.

2) Knowledge Retention and Stability

- Conflict Suppression and Mitigation: Failures under retrieval or context injection often arose from attention heads that mediated the integration of parametric memory and external evidence in the residual stream. Jin et al. [220] performed Causal Attribution to localize conflict-mediating heads and applied test-time head suppression/patching, i.e., Amplitude Manipulation over attention head output , to rebalance memory vs. context usage. Li et al. [221] further used Magnitude Anaylysis to identify heads exhibiting superposition effects and applied targeted gating via Targeted Optimization to stabilize behavior under conflicts. Long-context distraction was traced to entrainment-related heads: Niu et al. [136] localized such heads using Causal Attribution and ablated or modulated their outputs (), reducing echoing of irrelevant context tokens. Jin et al. [9] further characterized concentrated massive values in computations mediated by the Q/K weight matrices and (reflected in attention scores via Magnitude Analysis), then guided Amplitude Manipulation over corresponding head outputs to maintain contextual reading without disrupting magnitude-structured signals.

- Constraining Continual Adaptation: To reduce catastrophic forgetting, MI localized stability-critical carriers and restricted learning via Targeted Optimization. Zhang et al. [74] applied Gradient Detection to identify a “core linguistic” parameter region and froze it, mitigating forgetting. Zhang et al. [66] further constrained adaptation through coarse-to-fine module selection and soft masking, balancing specialty and versatility. Representation-level interventions were also employed: Wu et al. [222] localized residual stream states and applied lightweight edits on with a frozen backbone (a form of Targeted Optimization), improving stability relative to weight-centric updates. Monitoring side effects, Du et al. [88] used Probing over residual stream states and attention heads to detect security-relevant drift and selected safer module update schedules, enabling controlled adaptation.

3) Knowledge Consolidation

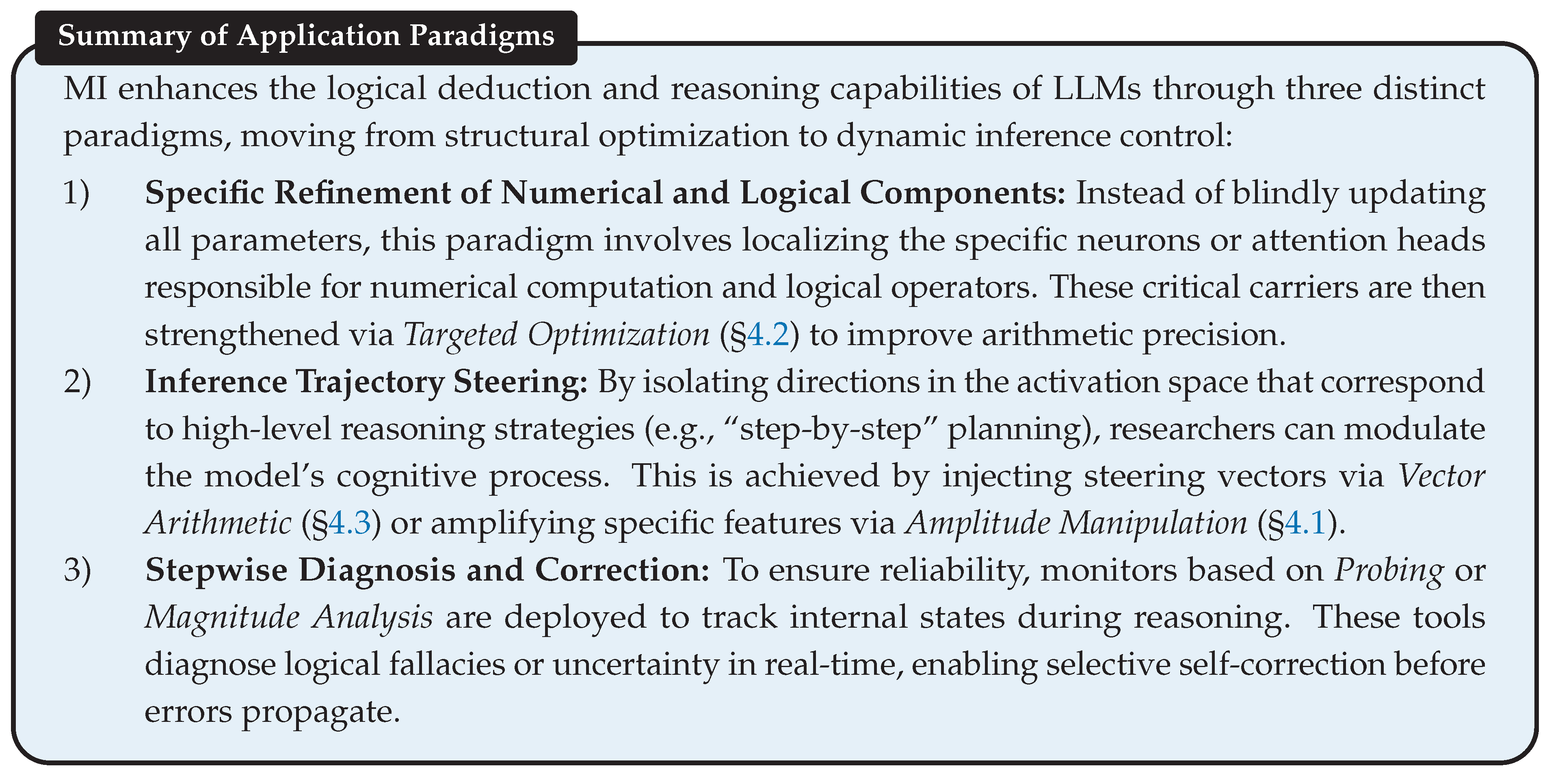

5.2.3. Logic and Reasoning

1) Specific Refinement of Numerical and Logical Components

2) Inference Trajectory Steering

3) Stepwise Diagnosis and Correction

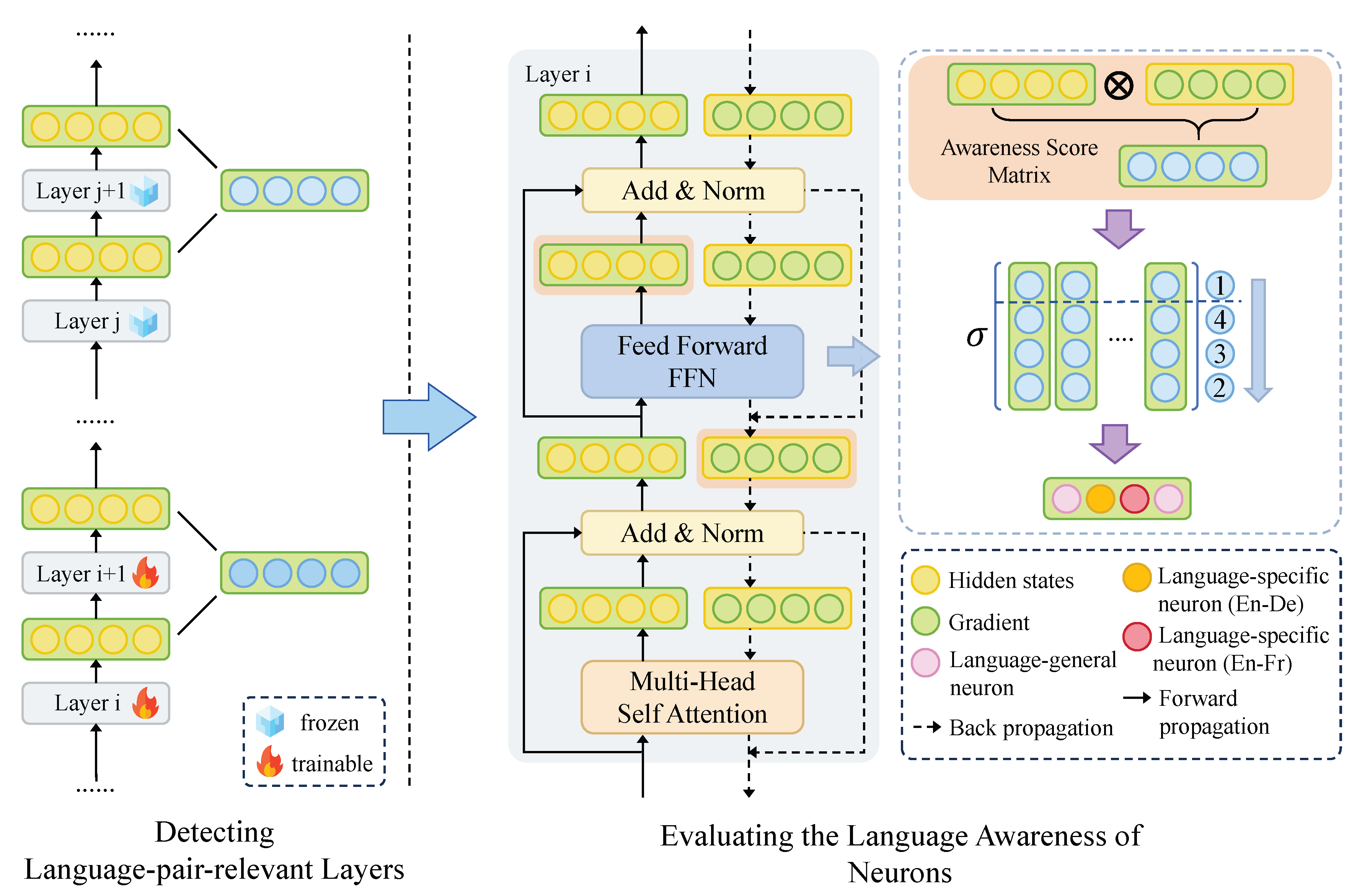

5.3. Improve Efficiency

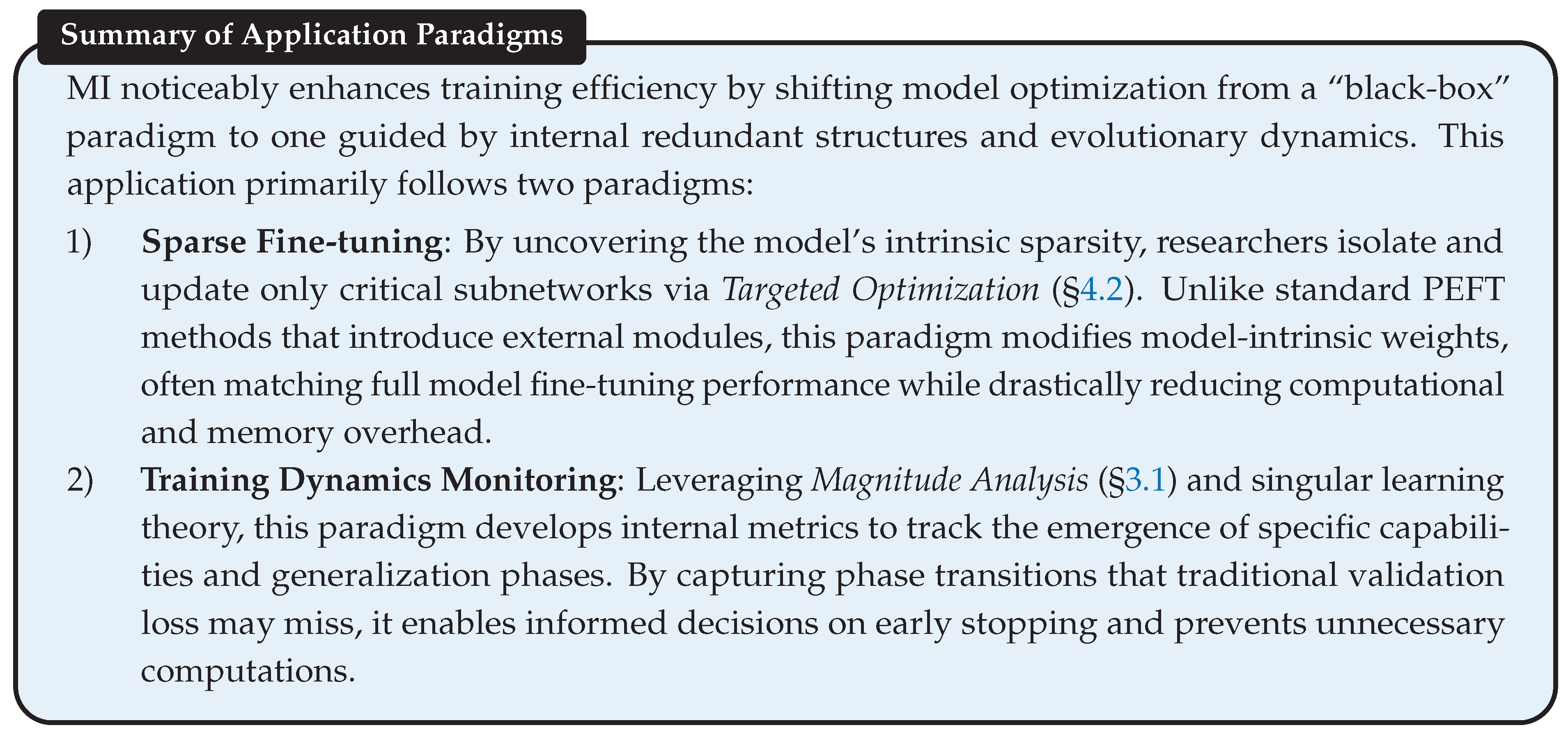

5.3.1. Efficient Training

1) Sparse Fine-tuning

2) Training Dynamic Monitoring

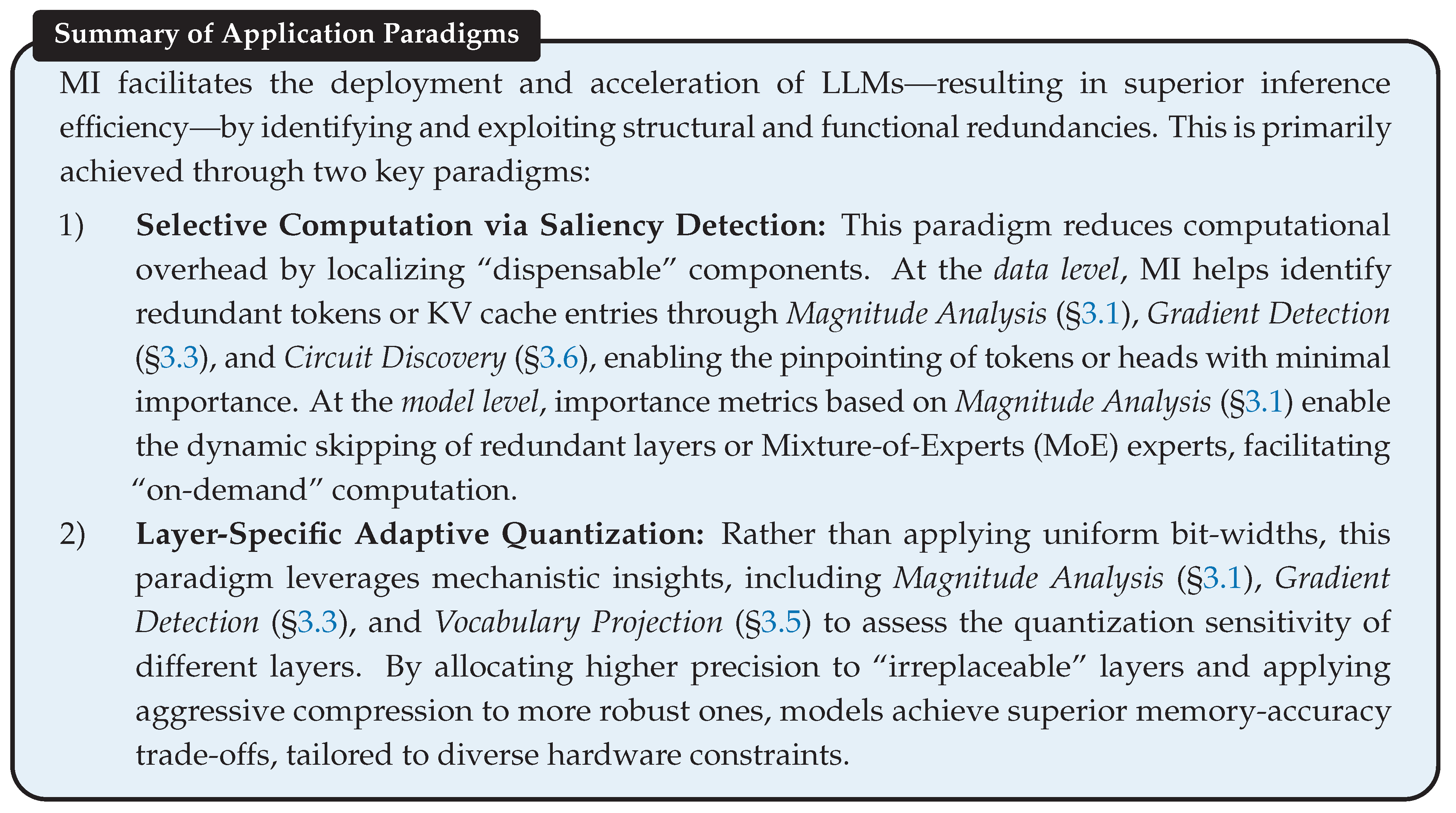

5.3.2. Efficient Inference

1) Selective Computation via Saliency Detection

- Data Level: Researchers have developed advanced token- and KV-cache-level pruning strategies that leverage Magnitude Analysis and Gradient Detection to effectively identify and remove unimportant tokens. By leveraging Magnitude Analysis to identify tokens with minimal contribution to the reasoning process in CoT sequences, TokenSkip [159] selectively skips these tokens, achieving substantial compression with negligible performance degradation. Lei et al. [251] explored explanation-driven token compression for multimodal LLMs, where Gradient Detection is used to map attention patterns to explanation outcomes, enabling the effective pruning of visual tokens during the input stage. For KV cache-level pruning, FitPrune [253] and ZipCache [21] employed Magnitude Analysis saliency metrics to identify and retain critical KV states. Guo et al. [252] introduced Value-Aware Token Pruning (VATP), which applied Magnitude Analysis to attention scores and the L1 norm of value attention vectors to identify crucial tokens. Moving beyond token-wise pruning, Circuit Discovery techniques have been applied to identify “Retrieval Heads” that are essential for long-context tasks, enabling non-critical heads to operate with a fixed-length KV cache [155,254,332,333].

- Model Level: MI-guided metrics enable the skipping of entire architectural blocks, such as redundant layers, MoE experts, or neurons, thereby facilitating inference acceleration with minimal impact on model performance. Men et al. [14] introduced “Block Influence” (BI), a similarity metric based on Magnitude Analysis that compares the input and output of each layer. This technique effectively removes layers with minimal contribution to the representation space. Dynamic bypassing methods, such as GateSkip [255] and LayerSkip [13], employ learnable residual gates to skip layers during inference, also based on Magnitude Analysis. Similarly, HadSkip [257] and SBERT [258] models leverage Magnitude Analysis to facilitate effective layer skipping. In MoE architectures, Lu et al. [259] skipped unimportant experts during inference based on the Magnitude Analysis of router scores. Su et al. [8] further identified Super Experts by analyzing the Magnitude Analysis of experts’ output activations, showing that these experts are essential for logical reasoning and that pruning them leads to catastrophic performance degradation. Finally, by localizing specialized multilingual neurons [25] and language-specific sub-networks [260] through Magnitude Analysis on their activations, LLMs can activate only the sub-circuits necessary for the specific task at hand.

2) Layer-Specific Adaptive Quantization

6. Challenges and Future Directions

Challenges

Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Limitation

Appendix A Summary of Surveyed Papers

| Paper | Object | Localizing Method | Steering Method | Venue | Year | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety and Reliability (Improve Alignment) | ||||||

| Zhou et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Huang et al. | MHA | Circuit Discovery | Targeted Optimization | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Jiang et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Chen et al. | Neuron | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Suau et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ICML | 2024 | Link |

| Gao et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Zhao et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Li et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Templeton et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | Blog | 2024 | Link |

| Goyal et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Yeo et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Li et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Weng et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Wu et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| He et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Li et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Lee et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Targeted Optimization | ICML | 2024 | Link |

| Arditi et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Zhao et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | NeurIPS | 2025 | Link |

| Yin et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Ball et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Wang et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Wang et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | NeurIPS | 2025 | Link |

| Ferreira et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Huang et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Pan et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Chuang et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Vector Arithmetic | ICLR | 2024 | Link |

| Chen et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Vector Arithmetic | ICML | 2024 | Link |

| Zhang et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Orgad et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Vector Arithmetic | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Stolfo et al. | Residual Stream | Gradient Detection | Vector Arithmetic | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Du et al. | Token Embedding | Gradient Detection | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Fairness and Bias (Improve Alignment) | ||||||

| Vig et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | NeurIPS | 2020 | Link |

| Chintam et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | ACLWS | 2023 | Link |

| Wang et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Kim et al. | MHA | Probing | Vector Arithmetic | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Dimino et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ICAIF | 2025 | Link |

| Chandna et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | TMLR | 2025 | Link |

| Cai et al. | FFN | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | ICIC | 2024 | Link |

| Ahsan et al. | FFN | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Li and Gao | FFN | Vocab Projection | Targeted Optimization | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Yu and Ananiadou | Neuron | Circuit Discovery | Targeted Optimization | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Liu et al. | Neuron | Gradient Detection | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2024 | Link |

| Yu et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | - | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Guan et al. | Residual Stream | - | Amplitude Manipulation | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Yu et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Raimondi et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Persona and Role (Improve Alignment) | ||||||

| Su et al. | Neuron | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Deng et al. | Neuron | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Lai et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Chen et al. | Neuron | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | ICML | 2024 | Link |

| Rimsky et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Poterti et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Chen et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Handa et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | NeurIPS | 2025 | Link |

| Tak et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Yuan et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Ju et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Targeted Optimization | COLM | 2025 | Link |

| Karny et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | - | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Banayeeanzade et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Bas and Novak | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Sun et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Pai et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Joshi et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Ghandeharioun et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Multilingualism (Improve Capability) | ||||||

| Xie et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2021 | Link |

| Kojima et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | NAACL | 2024 | Link |

| Tang et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Zhao et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Gurgurov et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Liu et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Jing et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Andrylie et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Brinkmann et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | NAACL | 2025 | Link |

| Libovický et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | EMNLP | 2020 | Link |

| Chi et al. | Residual Stream | - | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2023 | Link |

| Philippy et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2023 | Link |

| Wendler et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Mousi et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Hinck et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Vector Arithmetic | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Zhang et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Wang et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Wu et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | - | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Wang et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Vector Arithmetic | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Nie et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Vector Arithmetic | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Liu et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Vector Arithmetic | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Knowledge Management (Improve Capability) | ||||||

| Meng et al. | FFN | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | NeurIPS | 2022 | Link |

| Meng et al. | FFN | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | ICLR | 2023 | Link |

| Lai et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Li et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Jin et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Jin et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Lv et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Niu et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Zhao et al. | MHA | Probing | Targeted Optimization | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Yadav et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | NeurIPS | 2023 | Link |

| Yu and Ananiadou | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Zhang et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Chen et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Li et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | AAAI | 2025 | Link |

| Muhamed and Smith | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Yao et al. | FFN & MHA | Circuit Discovery | Amplitude Manipulation | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Du et al. | FFN & MHA | Probing | Targeted Optimization | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Zhang et al. | FFN & MHA | Gradient Detection | Targeted Optimization | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Liu et al. | FFN & MHA | Gradient Detection | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Yao et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | NeurIPS | 2025 | Link |

| Geva et al. | FFN & MHA | Causal Attribution | - | EMNLP | 2023 | Link |

| Zhang et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | COLING | 2025 | Link |

| Chen et al. | Neuron | Gradient Detection | Amplitude Manipulation | AAAI | 2024 | Link |

| Shi et al. | Neuron | Gradient Detection | Amplitude Manipulation | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Chen et al. | Neuron | Gradient Detection | Amplitude Manipulation | AAAI | 2025 | Link |

| Kassem et al. | Neuron | - | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Muhamed et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Goyal et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Marks et al. | SAE Feature | Circuit Discovery | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Kang and Choi | Residual Stream | Probing | - | EMNLP | 2023 | Link |

| Katz et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Targeted Optimization | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Wu et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Zhao et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Ju et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | COLING | 2024 | Link |

| Jin et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | COLING | 2025 | Link |

| Chen et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Vector Arithmetic | NeurIPS | 2025 | Link |

| Logic and Reasoning (Improve Capability) | ||||||

| Wu et al. | Token Embedding | Gradient Detection | - | ICML | 2023 | Link |

| You et al. | Token Embedding | Magnitude Analysis | - | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Cywiński et al. | Token Embedding | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | Blog | 2025 | Link |

| Cywiński et al. | Token Embedding | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | Blog | 2025 | Link |

| Wang et al. | FFN | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Yu and Ananiadou | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Zhang et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | ICML | 2024 | Link |

| Yu and Ananiadou | MHA | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Yu et al. | MHA | Causal Attribution | - | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Stolfo et al. | FFN & MHA | Causal Attribution | - | EMNLP | 2023 | Link |

| Akter et al. | FFN & MHA | Causal Attribution | - | COMPSAC | 2024 | Link |

| Yang et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Quirke and Barez | FFN & MHA | Causal Attribution | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2024 | Link |

| Chen et al. | FFN & MHA | Gradient Detection | Targeted Optimization | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Hanna et al. | FFN & MHA | Circuit Discovery | - | NeurIPS | 2023 | Link |

| Nikankin et al. | FFN & MHA | Circuit Discovery | - | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Galichin et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Pach et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Troitskii et al. | SAE Feature | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Venhoff et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Højer et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Tang et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Hong et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Zhang and Viteri | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Liu et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Sinii et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Li et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Ward et al. | Residual Stream | Causal Attribution | Vector Arithmetic | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Biran et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Ye et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Sun et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | - | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Wang et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Vector Arithmetic | AAAI | 2026 | Link |

| Tan et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | Targeted Optimization | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Efficient Training (Improve Efficiency) | ||||||

| Panigrahi et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | ICML | 2023 | Link |

| Zhu et al. | Neuron | Gradient Detection | Targeted Optimization | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Song et al. | Neuron | Gradient Detection | Targeted Optimization | ICML | 2024 | Link |

| Zhang et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | ACL | 2023 | Link |

| Xu et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | COLING | 2025 | Link |

| Mondal et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Gurgurov et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | AACL | 2025 | Link |

| Zhao et al. | Neuron | Causal Attribution | Targeted Optimization | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Li et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Sergeev and Kotelnikov | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Targeted Optimization | ICAI | 2025 | Link |

| Olsson et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2022 | Link |

| Wang et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Singh et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ICML | 2024 | Link |

| Hoogland et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | TLMR | 2025 | Link |

| Minegishi et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Lai et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Vector Arithmetic | ICML | 2025 | Link |

| Thilak et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | NeurIPS | 2022 | Link |

| Varma et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2023 | Link |

| Furuta et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | TMLR | 2024 | Link |

| Nanda et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ICLR | 2023 | Link |

| Notsawo Jr et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2023 | Link |

| Qiye et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Liu et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | ICLR | 2023 | Link |

| Wang et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Huang et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | COLM | 2024 | Link |

| Li et al. | FFN & MHA | Circuit Discovery | Targeted Optimization | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Efficient Inference (Improve Efficiency) | ||||||

| Xia et al. | Token Embedding | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2025 | Link |

| Lei et al. | Token Embedding | Gradient Detection | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Guo et al. | Token Embedding | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Ye et al. | Token Embedding | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | AAAI | 2025 | Link |

| He et al. | Token Embedding | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| Cai et al. | Token Embedding | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | COLM | 2025 | Link |

| Tang et al. | MHA | Circuit Discovery | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Xiao et al. | MHA | Circuit Discovery | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Bi et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | CVPR | 2025 | Link |

| Su et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | IJCAI | 2025 | Link |

| Xiao et al. | MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ICLR | 2024 | Link |

| Lu et al. | FFN | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Su et al. | FFN | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Yu et al. | FFN | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | Arxiv | 2024 | Link |

| Liu et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Tan et al. | Neuron | Magnitude Analysis | - | EMNLP | 2024 | Link |

| Laitenberger et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Valade | Residual Stream | Probing | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Elhoushi et al. | Residual Stream | Probing | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Wang et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | EMNLP | 2023 | Link |

| Lawson and Aitchison | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Men et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2025 | Link |

| Dumitru et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Zhang et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Xiao et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | - | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Ranjan and Savakis | Residual Stream | Gradient Detection | - | ArXiv | 2025 | Link |

| Zeng et al. | Residual Stream | Vocab Projection | - | ArXiv | 2024 | Link |

| Shelke et al. | Residual Stream | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | ACL | 2024 | Link |

| Lin et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | MLSyS | 2024 | Link |

| Ashkboos et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | NeurIPS | 2025 | Link |

| Su and Yuan | FFN & MHA | Circuit Discovery | - | COLM | 2025 | Link |

| Xiao et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | Amplitude Manipulation | NeurIPS | 2022 | Link |

| Sun et al. | FFN & MHA | Magnitude Analysis | - | NeurIPS | 2024 | Link |

| An et al. | FFN & MHA | Circuit Discovery | - | ICLR | 2025 | Link |

| Bondarenko et al. | FFN & MHA | Circuit Discovery | - | NeurIPS | 2023 | Link |

References

- Dettmers, T.; Lewis, M.; Belkada, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L. Gpt3. int8 (): 8-bit matrix multiplication for transformers at scale. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 30318–30332.

- Tang, T.; Luo, W.; Huang, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Wei, F.; Wen, J.R. Language-Specific Neurons: The Key to Multilingual Capabilities in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 5701–5715. [CrossRef]

- Galichin, A.; Dontsov, A.; Druzhinina, P.; Razzhigaev, A.; Rogov, O.Y.; Tutubalina, E.; Oseledets, I. I Have Covered All the Bases Here: Interpreting Reasoning Features in Large Language Models via Sparse Autoencoders. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.18878 2025.

- Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Lv, J.; Wang, X.; Bai, Q. Towards Superior Quantization Accuracy: A Layer-sensitive Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.06518 2025.

- An, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yu, T.; Tang, M.; Wang, J. Systematic outliers in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.06415 2025.

- Su, Z.; Yuan, K. KVSink: Understanding and Enhancing the Preservation of Attention Sinks in KV Cache Quantization for LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.04257 2025.

- Huben, R.; Cunningham, H.; Smith, L.R.; Ewart, A.; Sharkey, L. Sparse Autoencoders Find Highly Interpretable Features in Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Vienna, Austria, May 7-11, 2024. OpenReview.net, 2024.

- Su, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Qian, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yuan, K. Unveiling super experts in mixture-of-experts large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.23279 2025.

- Jin, M.; Mei, K.; Xu, W.; Sun, M.; Tang, R.; Du, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Massive Values in Self-Attention Modules are the Key to Contextual Knowledge Understanding. In Proceedings of the Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2025, Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 13-19, 2025. OpenReview.net, 2025.

- Bi, J.; Guo, J.; Tang, Y.; Wen, L.B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Xu, C. Unveiling visual perception in language models: An attention head analysis approach. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, 2025, pp. 4135–4144.

- Chuang, Y.S.; Xie, Y.; Luo, H.; Kim, Y.; Glass, J.R.; He, P. DoLa: Decoding by Contrasting Layers Improves Factuality in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024.

- Zhang, S.; Yu, T.; Feng, Y. TruthX: Alleviating Hallucinations by Editing Large Language Models in Truthful Space. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 8908–8949. [CrossRef]

- Elhoushi, M.; Shrivastava, A.; Liskovich, D.; Hosmer, B.; Wasti, B.; Lai, L.; Mahmoud, A.; Acun, B.; Agarwal, S.; Roman, A.; et al. LayerSkip: Enabling Early Exit Inference and Self-Speculative Decoding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 12622–12642. [CrossRef]

- Men, X.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, B.; Lin, H.; Lu, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, W. ShortGPT: Layers in Large Language Models are More Redundant Than You Expect. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025; Che, W.; Nabende, J.; Shutova, E.; Pilehvar, M.T., Eds., Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 20192–20204. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Lin, J.; Seznec, M.; Wu, H.; Demouth, J.; Han, S. Smoothquant: Accurate and efficient post-training quantization for large language models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 38087–38099.

- Ashkboos, S.; Mohtashami, A.; Croci, M.L.; Li, B.; Cameron, P.; Jaggi, M.; Alistarh, D.; Hoefler, T.; Hensman, J. Quarot: Outlier-free 4-bit inference in rotated llms. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 100213–100240.

- Yu, M.; Wang, D.; Shan, Q.; Reed, C.J.; Wan, A. The super weight in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.07191 2024.

- Cai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Lu, K.; Xiong, W.; Dong, Y.; Hu, J.; et al. Pyramidkv: Dynamic kv cache compression based on pyramidal information funneling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02069 2024.

- Xiong, J.; Fan, L.; Shen, H.; Su, Z.; Yang, M.; Kong, L.; Wong, N. DoPE: Denoising Rotary Position Embedding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.09146 2025.

- Xiong, J.; Chen, Q.; Ye, F.; Wan, Z.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, C.; Shen, H.; Li, A.H.; Tao, C.; Tan, H.; et al. ATTS: Asynchronous Test-Time Scaling via Conformal Prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.15148 2025.

- He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhuang, B. Zipcache: Accurate and efficient kv cache quantization with salient token identification. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 68287–68307.

- Su, Z.; Chen, Z.; Shen, W.; Wei, H.; Li, L.; Yu, H.; Yuan, K. Rotatekv: Accurate and robust 2-bit kv cache quantization for llms via outlier-aware adaptive rotations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.16383 2025.

- Yuan, J.; Gao, H.; Dai, D.; Luo, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, L.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Native sparse attention: Hardware-aligned and natively trainable sparse attention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2025, pp. 23078–23097.

- Lai, W.; Hangya, V.; Fraser, A. Style-Specific Neurons for Steering LLMs in Text Style Transfer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y.N., Eds., Miami, Florida, USA, 2024; pp. 13427–13443. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Hu, X.; Wu, J. Unraveling babel: Exploring multilingual activation patterns within large language models. arXiv 2024.

- Chen, R.; Hu, T.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Z. Learnable Privacy Neurons Localization in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 256–264. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Dejl, A.; Toni, F. Identifying Query-Relevant Neurons in Large Language Models for Long-Form Texts. In Proceedings of the AAAI-25, Sponsored by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, February 25 - March 4, 2025, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Walsh, T.; Shah, J.; Kolter, Z., Eds. AAAI Press, 2025, pp. 23595–23604. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lei, Z.; Tan, Z.; Ding, J.; Zhao, X.; Dong, Y.; Wu, G.; Chen, T.; Chen, C.; Zhang, A.; et al. BrainMAP: Learning Multiple Activation Pathways in Brain Networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI-25, Sponsored by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, February 25 - March 4, 2025, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Walsh, T.; Shah, J.; Kolter, Z., Eds. AAAI Press, 2025, pp. 14432–14440. [CrossRef]

- Andrylie, L.M.; Rahmanisa, I.; Ihsani, M.K.; Wicaksono, A.F.; Wibowo, H.A.; Aji, A.F. Sparse Autoencoders Can Capture Language-Specific Concepts Across Diverse Languages, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2507.11230].

- Gurgurov, D.; Trinley, K.; Ghussin, Y.A.; Baeumel, T.; van Genabith, J.; Ostermann, S. Language Arithmetics: Towards Systematic Language Neuron Identification and Manipulation, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2507.22608].

- Xiao, G.; Tian, Y.; Chen, B.; Han, S.; Lewis, M. Efficient Streaming Language Models with Attention Sinks. arXiv 2023.

- Cancedda, N. Spectral Filters, Dark Signals, and Attention Sinks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2024, pp. 4792–4808.

- Singh, A.K.; Moskovitz, T.; Hill, F.; Chan, S.C.; Saxe, A.M. What needs to go right for an induction head? a mechanistic study of in-context learning circuits and their formation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024, pp. 45637–45662.

- Wang, M.; Yu, R.; Wu, L.; et al. How Transformers Implement Induction Heads: Approximation and Optimization Analysis. arXiv e-prints 2024, pp. arXiv–2410.

- Zhou, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, R.; Huang, F.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J.; Li, Y. On the Role of Attention Heads in Large Language Model Safety, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2410.13708].

- Sergeev, A.; Kotelnikov, E. Optimizing Multimodal Language Models through Attention-based Interpretability, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2511.23375].

- Sun, S.; Baek, S.Y.; Kim, J.H. Personality Vector: Modulating Personality of Large Language Models by Model Merging. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Christodoulopoulos, C.; Chakraborty, T.; Rose, C.; Peng, V., Eds., Suzhou, China, 2025; pp. 24667–24688. [CrossRef]

- Bas, T.; Novak, K. Steering Latent Traits, Not Learned Facts: An Empirical Study of Activation Control Limits. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.18284 2025.

- Dumitru, R.G.; Yadav, V.; Maheshwary, R.; Clotan, P.I.; Madhusudhan, S.T.; Surdeanu, M. Layer-wise quantization: A pragmatic and effective method for quantizing llms beyond integer bit-levels. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.17415 2024.

- Tan, Z.; Dong, D.; Zhao, X.; Peng, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, T. Dlo: Dynamic layer operation for efficient vertical scaling of llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.11030 2024.

- Lawson, T.; Aitchison, L. Learning to Skip the Middle Layers of Transformers, 2025, [arXiv:cs.LG/2506.21103].

- Vig, J.; Gehrmann, S.; Belinkov, Y.; Qian, S.; Nevo, D.; Singer, Y.; Shieber, S. Investigating Gender Bias in Language Models Using Causal Mediation Analysis. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H.; Ranzato, M.; Hadsell, R.; Balcan, M.; Lin, H., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 12388–12401.

- Meng, K.; Bau, D.; Andonian, A.; Belinkov, Y. Locating and Editing Factual Associations in GPT. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, NeurIPS 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, November 28 - December 9, 2022; Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds., 2022.

- Zhang, F.; Nanda, N. Towards best practices of activation patching in language models: Metrics and methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.16042 2023.

- Stolfo, A.; Belinkov, Y.; Sachan, M. A Mechanistic Interpretation of Arithmetic Reasoning in Language Models using Causal Mediation Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Bouamor, H.; Pino, J.; Bali, K., Eds., Singapore, 2023; pp. 7035–7052. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ananiadou, S. How do Large Language Models Learn In-Context? Query and Key Matrices of In-Context Heads are Two Towers for Metric Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, November 12-16, 2024; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 3281–3292. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Ibeling, D.; Zur, A.; Chaudhary, M.; Chauhan, S.; Huang, J.; Arora, A.; Wu, Z.; Goodman, N.; Potts, C.; et al. Causal abstraction: A theoretical foundation for mechanistic interpretability. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2025, 26, 1–64.

- Ferreira, P.; Aziz, W.; Titov, I. Truthful or Fabricated? Using Causal Attribution to Mitigate Reward Hacking in Explanations. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Actionable Interpretability at ICML 2025, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2504.05294].

- Yeo, W.J.; Satapathy, R.; Cambria, E. Towards faithful natural language explanations: A study using activation patching in large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2025, pp. 10436–10458.

- Ravindran, S.K. Adversarial activation patching: A framework for detecting and mitigating emergent deception in safety-aligned transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.09406 2025.

- Yu, H.; Jeong, S.; Pawar, S.; Shin, J.; Jin, J.; Myung, J.; Oh, A.; Augenstein, I. Entangled in Representations: Mechanistic Investigation of Cultural Biases in Large Language Models, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2508.08879]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.R.; Variengien, A.; Conmy, A.; Shlegeris, B.; Steinhardt, J. Interpretability in the Wild: a Circuit for Indirect Object Identification in GPT-2 Small. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Geva, M.; Bastings, J.; Filippova, K.; Globerson, A. Dissecting Recall of Factual Associations in Auto-Regressive Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Bouamor, H.; Pino, J.; Bali, K., Eds., Singapore, 2023; pp. 12216–12235. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ananiadou, S. Interpreting Arithmetic Mechanism in Large Language Models through Comparative Neuron Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y.N., Eds., Miami, Florida, USA, 2024; pp. 3293–3306. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, X.; Hovy, E.H.; Jurafsky, D. Visualizing and Understanding Neural Models in NLP. In Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2016, The 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego California, USA, June 12-17, 2016; Knight, K.; Nenkova, A.; Rambow, O., Eds. The Association for Computational Linguistics, 2016, pp. 681–691. [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, M.; Taly, A.; Yan, Q. Axiomatic Attribution for Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2017, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6-11 August 2017; Precup, D.; Teh, Y.W., Eds. PMLR, 2017, Vol. 70, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 3319–3328.

- Smilkov, D.; Thorat, N.; Kim, B.; Viégas, F.B.; Wattenberg, M. SmoothGrad: removing noise by adding noise. CoRR 2017, abs/1706.03825, [1706.03825].

- Shrikumar, A.; Greenside, P.; Kundaje, A. Learning Important Features Through Propagating Activation Differences. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2017, Vol. 70, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research.

- Enguehard, J. Sequential Integrated Gradients: a simple but effective method for explaining language models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023, Toronto, Canada, July 9-14, 2023; Rogers, A.; Boyd-Graber, J.L.; Okazaki, N., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 7555–7565. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shen, E.M.; Badrinath, C.; Ma, J.; Lakkaraju, H. Analyzing chain-of-thought prompting in large language models via gradient-based feature attributions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.13339 2023.

- Hou, E.M.; Castañón, G.D. Decoding Layer Saliency in Language Transformers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2023, 23-29 July 2023, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA; Krause, A.; Brunskill, E.; Cho, K.; Engelhardt, B.; Sabato, S.; Scarlett, J., Eds. PMLR, 2023, Vol. 202, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 13285–13308.

- Tao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y. Saliency-driven Dynamic Token Pruning for Large Language Models. CoRR 2025, abs/2504.04514, [2504.04514]. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Prasad, A.; Stengel-Eskin, E.; Bansal, M. GrAInS: Gradient-based Attribution for Inference-Time Steering of LLMs and VLMs. CoRR 2025, abs/2507.18043, [2507.18043]. [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Dong, L.; Hao, Y.; Sui, Z.; Chang, B.; Wei, F. Knowledge Neurons in Pretrained Transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), ACL 2022, Dublin, Ireland, May 22-27, 2022; Muresan, S.; Nakov, P.; Villavicencio, A., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 8493–8502. [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Jin, R.; Shen, T.; Dong, W.; Wu, X.; Xiong, D. IRCAN: Mitigating Knowledge Conflicts in LLM Generation via Identifying and Reweighting Context-Aware Neurons. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 38: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, NeurIPS 2024, Vancouver, BC, Canada, December 10 - 15, 2024; Globersons, A.; Mackey, L.; Belgrave, D.; Fan, A.; Paquet, U.; Tomczak, J.M.; Zhang, C., Eds., 2024.

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, S.; Zhao, R.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, F. Balancing Speciality and Versatility: a Coarse to Fine Framework for Supervised Fine-tuning Large Language Model. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11-16, 2024; Ku, L.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 7467–7509. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Huang, S.; Shang, C.; Zhan, B.; Jiang, Y. Improving low-resource knowledge tracing tasks by supervised pre-training and importance mechanism fine-tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.06725 2024.

- Li, M.; Li, Y.; Zhou, T. What Happened in LLMs Layers when Trained for Fast vs. Slow Thinking: A Gradient Perspective. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Che, W.; Nabende, J.; Shutova, E.; Pilehvar, M.T., Eds., Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 32017–32154. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, T. How Instruction and Reasoning Data shape Post-Training: Data Quality through the Lens of Layer-wise Gradients, 2025, [arXiv:cs.LG/2504.10766].

- Jafari, F.R.; Eberle, O.; Khakzar, A.; Nanda, N. RelP: Faithful and Efficient Circuit Discovery via Relevance Patching. CoRR 2025, abs/2508.21258, [2508.21258]. [CrossRef]

- Azarkhalili, B.; Libbrecht, M.W. Generalized Attention Flow: Feature Attribution for Transformer Models via Maximum Flow. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), ACL 2025, Vienna, Austria, July 27 - August 1, 2025; Che, W.; Nabende, J.; Shutova, E.; Pilehvar, M.T., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2025, pp. 19954–19974.

- Liu, S.; Wu, H.; He, B.; Han, X.; Yuan, M.; Song, L. Sens-Merging: Sensitivity-Guided Parameter Balancing for Merging Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2025, Vienna, Austria, July 27 - August 1, 2025; Che, W.; Nabende, J.; Shutova, E.; Pilehvar, M.T., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2025, pp. 19243–19255.

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Gong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, P. Enhancing Large Language Model Performance with Gradient-Based Parameter Selection. In Proceedings of the AAAI-25, Sponsored by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, February 25 - March 4, 2025, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Walsh, T.; Shah, J.; Kolter, Z., Eds. AAAI Press, 2025, pp. 24431–24439. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gui, T.; Huang, X. Unveiling Linguistic Regions in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand, August 11-16, 2024; Ku, L.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 6228–6247. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xi, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hong, B.; Gui, T.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, X. LoRACoE: Improving Large Language Model via Composition-based LoRA Expert. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Christodoulopoulos, C.; Chakraborty, T.; Rose, C.; Peng, V., Eds., Suzhou, China, 2025; pp. 31290–31304. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Guo, X.; Shen, Z. Gradient based Feature Attribution in Explainable AI: A Technical Review. CoRR 2024, abs/2403.10415, [2403.10415]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Variengien, A.; Conmy, A.; Shlegeris, B.; Steinhardt, J. Interpretability in the wild: a circuit for indirect object identification in gpt-2 small. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.00593 2022.

- Yin, K.; Neubig, G. Interpreting Language Models with Contrastive Explanations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Goldberg, Y.; Kozareva, Z.; Zhang, Y., Eds., Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 184–198. [CrossRef]

- Alain, G.; Bengio, Y. Understanding intermediate layers using linear classifier probes. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2017, Toulon, France, April 24-26, 2017, Workshop Track Proceedings. OpenReview.net, 2017.

- Belinkov, Y. Probing Classifiers: Promises, Shortcomings, and Advances. Comput. Linguistics 2022, 48, 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Conneau, A.; Kruszewski, G.; Lample, G.; Barrault, L.; Baroni, M. What you can cram into a single \$&!#* vector: Probing sentence embeddings for linguistic properties. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2018, Melbourne, Australia, July 15-20, 2018, Volume 1: Long Papers; Gurevych, I.; Miyao, Y., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018, pp. 2126–2136. [CrossRef]

- Tenney, I.; Das, D.; Pavlick, E. BERT Rediscovers the Classical NLP Pipeline. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Conference of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2019, Florence, Italy, July 28- August 2, 2019, Volume 1: Long Papers; Korhonen, A.; Traum, D.R.; Màrquez, L., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 4593–4601. [CrossRef]

- Ravichander, A.; Belinkov, Y.; Hovy, E.H. Probing the Probing Paradigm: Does Probing Accuracy Entail Task Relevance? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume, EACL 2021, Online, April 19 - 23, 2021; Merlo, P.; Tiedemann, J.; Tsarfaty, R., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 3363–3377. [CrossRef]

- Ju, T.; Sun, W.; Du, W.; Yuan, X.; Ren, Z.; Liu, G. How Large Language Models Encode Context Knowledge? A Layer-Wise Probing Study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC/COLING 2024, 20-25 May, 2024, Torino, Italy; Calzolari, N.; Kan, M.; Hoste, V.; Lenci, A.; Sakti, S.; Xue, N., Eds. ELRA and ICCL, 2024, pp. 8235–8246.

- Zhao, Y.; Du, X.; Hong, G.; Gema, A.P.; Devoto, A.; Wang, H.; He, X.; Wong, K.; Minervini, P. Analysing the Residual Stream of Language Models Under Knowledge Conflicts. CoRR 2024, abs/2410.16090, [2410.16090]. [CrossRef]

- Orgad, H.; Toker, M.; Gekhman, Z.; Reichart, R.; Szpektor, I.; Kotek, H.; Belinkov, Y. LLMs Know More Than They Show: On the Intrinsic Representation of LLM Hallucinations. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2025.

- You, W.; Xue, A.; Havaldar, S.; Rao, D.; Jin, H.; Callison-Burch, C.; Wong, E. Probabilistic Soundness Guarantees in LLM Reasoning Chains. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Suzhou, China, 2025; pp. 7517–7536. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, S.; Cao, J.; Ma, M.; Zhao, D.; Fan, F.; Liu, T.; Qin, B. Towards Secure Tuning: Mitigating Security Risks Arising from Benign Instruction Fine-Tuning. CoRR 2024, abs/2410.04524, [2410.04524]. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Liu, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, H.; Qin, B. Probing and Boosting Large Language Models Capabilities via Attention Heads. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Christodoulopoulos, C.; Chakraborty, T.; Rose, C.; Peng, V., Eds., Suzhou, China, 2025; pp. 28518–28532. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Evans, J.; Schein, A. Linear Representations of Political Perspective Emerge in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2025, Singapore, April 24-28, 2025. OpenReview.net, 2025.

- Kantamneni, S.; Engels, J.; Rajamanoharan, S.; Tegmark, M.; Nanda, N. Are Sparse Autoencoders Useful? A Case Study in Sparse Probing. In Proceedings of the Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2025, Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 13-19, 2025. OpenReview.net, 2025.

- Chanin, D.; Wilken-Smith, J.; Dulka, T.; Bhatnagar, H.; Bloom, J. A is for Absorption: Studying Feature Splitting and Absorption in Sparse Autoencoders. CoRR 2024, abs/2409.14507, [2409.14507]. [CrossRef]

- nostalgebraist. Interpreting GPT: the Logit Lens, 2020.

- Geva, M.; Schuster, R.; Berant, J.; Levy, O. Transformer Feed-Forward Layers Are Key-Value Memories. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Moens, M.F.; Huang, X.; Specia, L.; Yih, S.W.t., Eds., Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 5484–5495. [CrossRef]

- Belrose, N.; Furman, Z.; Smith, L.; Halawi, D.; Ostrovsky, I.; McKinney, L.; Biderman, S.; Steinhardt, J. Eliciting latent predictions from transformers with the tuned lens. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08112 2023.

- Jiang, C.; Qi, B.; Hong, X.; Fu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Meng, F.; Yu, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, J. On Large Language Models’ Hallucination with Regard to Known Facts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2024, pp. 1041–1053.

- Jiang, N.; Kachinthaya, A.; Petryk, S.; Gandelsman, Y. Interpreting and Editing Vision-Language Representations to Mitigate Hallucinations, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CV/2410.02762].

- Wendler, C.; Veselovsky, V.; Monea, G.; West, R. Do Llamas Work in English? On the Latent Language of Multilingual Transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 15366–15394. [CrossRef]

- Kargaran, A.H.; Liu, Y.; Yvon, F.; Schütze, H. How Programming Concepts and Neurons Are Shared in Code Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.01074 2025.

- Phukan, A.; Somasundaram, S.; Saxena, A.; Goswami, K.; Srinivasan, B.V. Peering into the Mind of Language Models: An Approach for Attribution in Contextual Question Answering. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 11481–11495. [CrossRef]

- Phukan, A.; Divyansh.; Morj, H.K.; Vaishnavi.; Saxena, A.; Goswami, K. Beyond Logit Lens: Contextual Embeddings for Robust Hallucination Detection & Grounding in VLMs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers); Chiruzzo, L.; Ritter, A.; Wang, L., Eds., Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2025; pp. 9661–9675. [CrossRef]

- Yugeswardeenoo, D.; Nukala, H.; Blondin, C.; O’Brien, S.; Sharma, V.; Zhu, K. Interpreting the Latent Structure of Operator Precedence in Language Models. In Proceedings of the The First Workshop on the Interplay of Model Behavior and Model Internals, 2025.

- Sakarvadia, M.; Khan, A.; Ajith, A.; Grzenda, D.; Hudson, N.; Bauer, A.; Chard, K.; Foster, I. Attention lens: A tool for mechanistically interpreting the attention head information retrieval mechanism. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.16270 2023.

- Yu, Z.; Ananiadou, S. Understanding multimodal llms: the mechanistic interpretability of llava in visual question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10950 2024.