1. Introduction

Algorithms are critical in video games as they determine rules, behaviors, and outcomes. In puzzle video games, algorithms are more valuable because the logic required in playing these games does not need reflexes or speed [

2]. One of the most common puzzle video games that has been used as a case study for logical reasoning is Minesweeper [

4].

Minesweeper is a game where the player deals with a grid of cells with hidden values. While some cells contain mines, others hold numbers when uncovered. These numbers show how many mines lie in the neighboring cells. Based on these details, players apply a series of rules to identify the cells to visit and the ones to avoid. All these activities can be defined as a rule-based decision algorithm [

1].

This paper studies Minesweeper from an algorithmic perspective and aims to answer the following research questions:

How does the Minesweeper algorithm work?

How effective is the algorithm on different board sizes?

What limitations does the algorithm have when information is incomplete?

2. Related Work

Game algorithms depend on the genre of the game. In action games, physics and collision algorithms are common, while search algorithms like Mini-Max and Monte Carlo Tree Search algorithms are employed in strategic games [

2]. Puzzle games, for instance, Minesweeper, mostly use rule-based logic and mathematical constraints [

4].

It has been found in previous research that Minesweeper can be solved by considering it as a constraint satisfaction problem, wherein every number opened by the user decreases the number of possible locations where the adjacent mines could be [

5]. Several researchers have also attempted to solve Minesweeper by using automated algorithms and artificial intelligence [

6].

Minesweeper is one type of problem research being done by faculty members in the university because the rules tend to be very simple but sometimes the decision tree becomes complicated [

3,

7].

3. Methodology

3.1. Algorithm Description

The algorithm employed in Minesweeper takes local numerical inputs in such a manner as to depend solely on the input provided by the open squares. In other words, for every open square, it does not function as an independent algorithm but as one that supplies data regarding its neighboring squares. These neighboring squares are those which are horizontally, vertically, and diagonally positioned with regard to the open square.

The main rule of the algorithm is:

What this means is that the number shown in a revealed square corresponds exactly to the number of mines that are present in the cells that surround it. For instance, if it is shown that a cell contains the number 2, this means that exactly two of its surrounding cells contain bombs [

4]. The above corresponds to the basis of the Minesweeper algorithm.

Following this rule, players follow a series of basic logically reasoning steps in making decisions for the game. For instance, when the figure exposed in a square equals the number of neighboring squares that are yet to be opened, all the neighboring squares that are yet to be opened must contain landmines. Players are then able to mark the squares as landmines without any risk.

Second, if the number visible in a revealed square is comparable to the number of adjacent squares previously labeled as mines, then all remaining adjacent squares which remain unopened must remain safe. In this case, a definite conclusion has been made by the algorithm which allows the player to safely open remaining squares.

Nevertheless, there are circumstances where it is not possible to apply either of these strategies. If the number of unexplored squares adjacent to the present location does not match the number indicated on the present location, as well as the number of marked minuses not being consistent with a win attempt, it is not possible for the algorithm to draw a final conclusion.

This is a step-by-step procedure for making decisions based solely on numerical comparison and information available locally, and it is as plain as it is simple and is a form of rule-based algorithms. The algorithm does not require any adaptation or prediction other than what is contained in the numerical information available in the state of play in the game itself and is almost identical to rule-based decision algorithms as described in many games-based literature reviews [

2].

3.2. Testing Methods

This study used simple testing approaches commonly applied in game research:

Black-box testing, where the game was tested without access to its source code [

8].

User-based testing, where a human player executed the algorithm through gameplay and observation [

3].

Exploratory testing, where the game was played freely to observe algorithm behavior under different conditions [

9].

3.3. Experimental Design

Three simple experiments were conducted through manual gameplay:

Screenshots were captured during gameplay and recorded as figures.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experiment 1: Board Size vs Algorithm Effectiveness

Objective:

The following experiment tests the performance of the rule-based algorithm in Minesweeper using game boards of different sizes. This experiment investigates whether the algorithm performs better on smaller boards compared to larger boards.

Procedure:

The game was played at different board levels, namely the Beginner level, the Intermediate level, and the Expert level. Each level is associated with different board sizes and accordingly different difficulties. The Beginner board size is the smallest, while the Intermediate size is medium, and the Expert is the largest.

In each size of the boards, five full games were played. In each game, each move was observed closely. In each move, a classification was done, and two categories were used. A move that could be made following the numerical rules of the game of Minesweeper was considered a logical move. A move that was taken because the system did not give enough information to determine the safe move was considered a guess move.

After every game, the number of logical moves and guess moves made is recorded. Then, the results of these five games for every board size were calculated by taking the average, which is shown in the table below.

| Board Size |

Games Played |

Logical Moves |

Guessess Moves |

| Beginner (9x9) |

5 |

26 |

2 |

| Intermediate(16x16) |

5 |

31 |

6 |

| Expert (30x16) |

5 |

24 |

13 |

Observation:

The results show that smaller boards allowed the player to make more moves using logical rules, while larger boards required a higher number of guess moves. On the Beginner board, most decisions could be made using the algorithm without guessing. On the Intermediate board, guessing occurred more often, but logical moves were still common. On the Expert board, the number of guess moves increased significantly, indicating that the algorithm became less effective as the board size and complexity increased. This demonstrates that as the problem space grows, the rule-based algorithm has fewer situations where it can make a clear decision, leading to reduced effectiveness [

6].

Figure 1.

Logical move on a small board where the number clearly identifies safe squares.

Figure 1.

Logical move on a small board where the number clearly identifies safe squares.

4.2. Experiment 2: Forced Guess Situations

Objective:

The objective of this experiment is to identify situations in which the Minesweeper rule-based algorithm is unable to make a clear decision. Specifically, this experiment focuses on moments where the available numerical information is not sufficient for the algorithm to determine whether a square is safe or contains a mine.

Procedure:

During gameplay, it was tested continuously applying the standard Minesweeper logical rules based on the numbers shown on revealed squares. Whenever these rules could be used to clearly identify a safe square or a mine, the move was classified as a logical move. However, when none of the logical rules applied and no safe decision could be made, the situation was recorded as a forced guess.

A forced guess occurred when the player faced multiple unopened squares with no numerical configuration that allowed a definite conclusion. In these situations, the algorithm could not determine a correct move using logic alone, and the player was required to select a square without certainty. Each time this occurred, the game number, board size, and final result were recorded.

| Game # |

Board Size |

Forced Guess Occurred |

Result |

| 1 |

Beginner |

No |

Win |

| 2 |

Intermediate |

Yes |

Win |

| 3 |

Intermediate |

Yes |

Loss |

| 4 |

Expert |

Yes |

Loss |

| 5 |

Expert |

Yes |

Loss |

Observation:

The results show that forced guess situations occurred more frequently as the board size increased. On the Beginner board, no forced guessing was required, and the game resulted in a win. On the Intermediate board, forced guesses appeared, with mixed outcomes. On the Expert board, forced guesses occurred in every recorded game and consistently resulted in losses. This indicates that as board complexity increases, the rule-based algorithm reaches undecidable states more often, highlighting a known limitation of rule-based decision systems when information is incomplete [

5].

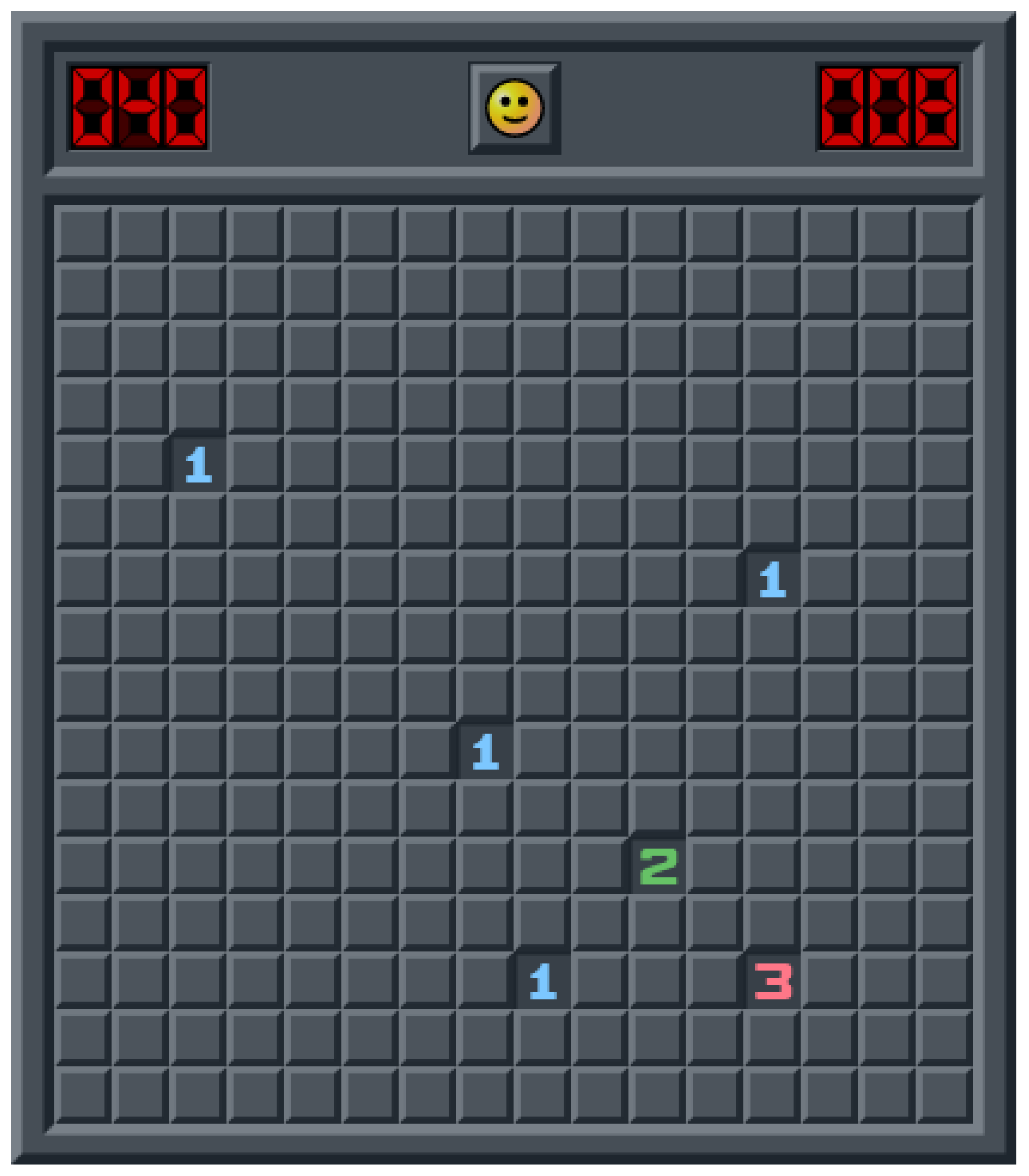

Figure 2.

Forced-guess situation where no rule-based deduction is possible.

Figure 2.

Forced-guess situation where no rule-based deduction is possible.

4.3. Experiment 3: Repeated Play and Decision Quality

Objective:

The objective of this experiment is to observe how repeated gameplay affects the quality of decision-making when executing the Minesweeper rule-based algorithm. This experiment focuses on whether playing multiple games consecutively, without taking breaks, has an impact on the player’s ability to correctly apply the algorithm.

Procedure:

In this experiment, five Minesweeper games were played consecutively without any breaks between games. All games were played using the same difficulty level to ensure consistent conditions. During each game, the time taken to complete the game and the final outcome were recorded.

In addition to recording the total time, the number of errors made in each game was also tracked. An error was defined as any incorrect decision, such as clicking a mine or making a wrong guess that resulted in a loss. The purpose of recording both time and errors was to observe whether performance changed as the number of consecutive games increased.

| Game # |

Time Taken (Minutes) |

Errors Made |

Result |

| 1 |

4.2 |

1 |

Win |

| 2 |

4.8 |

1 |

Win |

| 3 |

5.5 |

2 |

Loss |

| 4 |

6.1 |

2 |

Loss |

| 5 |

6.7 |

3 |

Loss |

Observation:

The results show a clear increase in both the time taken to complete each game and the number of errors made as the games progressed. The first two games were completed more quickly and resulted in wins, with fewer errors. In contrast, the later games took longer to complete and resulted in losses, with a higher number of errors. This pattern suggests that repeated play without breaks reduced the player’s ability to consistently apply the rule-based algorithm. These findings indicate the effect of cognitive fatigue on decision-making, where prolonged gameplay negatively impacts algorithm execution and increases the likelihood of mistakes.

Figure 3.

Game-over state after an incorrect guess.

Figure 3.

Game-over state after an incorrect guess.

5. Discussion

The experiments’ results suggest that the Minesweeper rule-based algorithm is performing well when there is enough information available to the algorithm to make logical decisions. In smaller versions of the game, like the Beginner board, numerical clues are closely packed and thus provide sufficient information to the algorithm so that it can clearly determine safe squares and mine locations, which leads to fewer guess moves and higher successes.

However, this situation changes in larger versions of Minesweeper. There is less numerical information in concentrated patterns as board size increases. Due to this fact, the numerical information becomes less intensive or not existent at all in so many areas. This inhibits the algorithm from making unambiguous decisions. This is why some of the moves cannot be defined logically but instead must be guessed. Those ‘forced guesses’ show an intrinsic limit of rule-based algorithms, where incomplete information prevents correct guaranteed decisions [

1,

5].

The results of such experiments are valid from an existing viewpoint on puzzle games and human problem-solving. The existing research has indicated that with an increase in complexity of tasks, it has been found that the source of inefficiency for algorithms increases due to higher uncertainty levels [

6]. The experiment on Minesweeper has validated such findings by establishing that with complexity in the environment, the same algorithms result in lower efficiency.

6. Conclusion

This research paper offered analysis of the algorithm used in the computer game “Minesweeper” as a decision system. The aim of the research was to experiment on the algorithm in controlled conditions to test its efficiency in different settings, including changes to the playing board size and recurrent playing of the game.

The findings demonstrate that the algorithm used in Minesweeper works well on smaller versions of the game board where a considerable amount of numeric information is available. This algorithm fails on a larger game board where some predictions have to be made due to the lack of information. This highlights that rule-based algorithms are more efficient in simpler situations but less reliable in more complicated situations.

In general, the above research offers a realistic approach for analyzing algorithms in games without the need for complicated computer programming or artificial intelligence methods. Experimentation demonstrates that a simple computer game such as Minesweeper can be employed for analyzing algorithms, decision limitations, or the influence of complexity in computer games.

References

- Juul, J. Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Millington, I.; Funge, J. Artificial Intelligence for Games, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.A. The Design of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia, Minesweeper (video game). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minesweeper_(video_game).

- Kaye, R. Minesweeper is NP-complete. Mathematical Intelligencer 2000, 22, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. A solver of single-agent stochastic puzzle: A case study with Minesweeper. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, vol. 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, B. The World of Scary Video Games; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GeeksforGeeks, Black box testing. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/black-box-testing/.

- Katalon. Exploratory testing. Available online: https://katalon.com/.

- YouTube, “The Ultimate Beginners Guide to Minesweeper”. 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).