1. Introduction

Prime numbers occupy a central place in number theory. They are the multiplicative building blocks of the positive integers: every integer n > 1 factors uniquely as a product of primes. This is the content of the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic.

In the process of understanding and researching, prime numbers seem to appear irregularly and uncannily. Although there are one-sided formulas for generating primes, such as those proposed by Euler and Mersenne, etc., it is always impossible to predict the next prime number. This very mystery has captivated many mathematicians throughout history, compelling them to devote their efforts—even their entire lives—to unraveling the patterns governing primes.

This situation was finally terminated by the great mathematician Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann in the mid-19th century. In his famous paper “Über die Anzahl der Primzahlen unter einer gegebenen Grösse” [

2] (English: "On the Number of Primes Less Than a Given Magnitude" [3, p.299]), Riemann proved the exact expression of the prime-counting function containing all nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function. But then, a new problem had emerged from Riemann’s work—the similar irregularity in the pattern of the nontrivial zeros has led countless mathematicians in various eras after Riemann to tirelessly and painfully explore the way and the mathematical laws that determine their presence.

To this day, in mathematics, it is widely known that this problem has not been completely solved.

Based mainly on the study and exploration of [

1,

2,

3], we realize that Riemann presented two parts of content in his notable 1859 paper:

1.1 Part One: the exact expression of the prime counting function, π(x), which is, in mathematical history, only an analytical expression of the distribution of primes found until now;

1.2 Part Two: the approximate numbers and approximate distribution of the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann ζ(s)or/and ξ(s)function within a certain range. These estimates were based on the characteristics of the ξ(s) function constructed by Riemann. Perhaps based on these, Riemann proposed the Riemann Hypothesis.

What follows is an overview of Riemann's elegant path to obtaining the prime counting function without proofs.

1.1.1 The Leonhard Euler zeta function is normally defined as

where, . Thus, the relationship between all natural numbers and all primes has been established. This connection prompted Riemann to begin exploring the Prime Counting Function.

The Riemann zeta function was redefined as

on this half-plane, the series converges absolutely and is a holomorphic function.

Next, Riemann started to combine the original definition of

ζ(

s) in (1) and Euler's integral definition of the Gamma function, then performed the complex contour integration (analytic continuation) on the expression obtained. This equation was then simplified via Euler's

formula in complex analysis and the

Jacobi φ(s) function, Riemann obtained one of the functional equations between

ζ(

s) and

ζ(1-

s) [3, p.13] [4, p.13],

Regarding (2), Riemann said in [

2]: “it is zero if

s is equal to a negative even integer” which is named a trivial zero of the Riemann zeta function. The other zeros of are correspondingly called the nontrivial zeros.

Using the identities of Gamma function [3, p.8], Riemann rewrote (2) as another desired functional equation [3, p.14] [4, p.16]

Obviously, by substituting s with 1-s into the LHS of (3), it becomes the right of (3). Because the poles of on the negative real axis are killed by the trivial zeros of ζ(s), (3) is a meromorphic functional equation except for the poles at s = 0 and s = 1. There are many other functional equations [3, p.14] [4, p.16] between ζ(s) and ζ(1-s) which will not be needed in this paper.

1.1.2 The most brilliant and intelligent thing is that Riemann constructed the following function [

2] [3, p.16] [4, p.16] as

It is an entire function, because the remaining only two poles at

s = 0 for

and

s = 1 for

ζ(

s) are fully canceled by factors

s and (1-

s), respectively. From (3), it has

and

[5, p.159][6, p.22]. The other characteristics about

used in this paper are stated below in Property 1, 2, 3 and 4 of

Section 2.

It is amazing that (4) can also be gracefully presented by Riemann as an infinite product [

2] [

7] [3, p.39] with all nontrivial zeros of Riemann zeta function as

where, ξ(0) = 1/2 and ρ runs over all nontrivial zeros of Riemann ξ(s) or ζ(s) function. It could be said that the acquisition of (5) is the indispensable key in the process of Riemann finally demonstrating the analytical prime counting function. Obtaining (5) is considered the most difficult part of Riemann's paper [3, p.17].

1.1.3 So far, the Riemann product formula in (1) has not been used yet. After having discovered the following interesting identities

Riemann combined the identities above and the Riemann product formula to represent one below

and whereupon marvelously wrote down [

2]

where, J(x) is a new step function – Riemann prime counting function. More details refer to [3, p.22]. In 1889, the function above was proved by Stieltjes [3, p.22].

Making use of Fourier inversion, Riemann concluded [

2] [3, p.23]

Substituting the term, ln

ζ(

s) by the result combining logarithms of (4) and (5), and then integrating the right part of equation above, Riemann finally completed

J(

x) [

2] [3, p.33] with the evaluation of the terms in the formula as

where, Li(

x) is the logarithmic integral function. This analytic formula including all nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function for

J(

x) is the principal result of his paper [

3].

After in-depth analysis, Riemann realized that the formula above can be demonstrated as

where, π(x) is the prime counting function – the number of primes less than any given magnitude x.

Inverting the relationship between

J(

x) and

π(

x) by means of the Möbius inversion formula, Riemann ultimately succeeded in obtaining

It gives an analytical formula for

π(

x) as desired [3, p.34]. The first term in the series function above is Li(

x), also the first term in

J(

x). In 1896 [

8,

9], under the condition that the Riemann

ζ(

s) function has no nontrivial zeros on the line, Re(

s) = 1, Hadamard and De Vallée Poussin independently turned the Gauss and Legendre prime number conjecture,

π(

x) ~ Li(

x) as

x → ∞, to the Prime Number Theorem. Spontaneously, the range, Riemann's 0 ≤ Re(s) ≤1 of the imaginary parts of the nontrivial zeros was corrected to be 0 < Re(s) <1.

At this point, Riemann's ultimate goal – to find the Number of Primes Less Than a Given Magnitude was almost achieved, save a problem created by Riemann himself—finding the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function in J(x).

1.2.1 The most concise expression of the Riemann zeta function is implicitly presented in the form of a functional equation, namely, (2). The complexity of the Riemann

ζ(

s) function naturally is gestated in the Riemann

ξ(

s) function, and more naturally foreshadows the complexity of finding their nontrivial zeros. This complexity is reflected in the fact that only in 1903, 44 years after Riemann's paper, was Gram able to use the Euler-Maclaurin formula to calculate and show the world the first 15 approximate values [

10] of the imaginary parts of the nontrivial zeros on the critical line. But this is not the first time that mathematicians have found these values; in fact, as shown in

Figure 1 below,

the first person to obtain these values was Riemann.

Of course, Riemann understood the properties of the real function [4, p.16] and the symmetry for ξ(s) at Re(s)=1/2. After substituting s = 1/2+it, (4) was rewritten as

Evidently, the first factor on the right side of the above equation is always negative.

Therefore, studying the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann

ξ(

s) or

ζ(

s) function reduces to studying the zeros of the second factor, which in turn reduces to studying the sign changes of the second factor. For more details, refer to [

1] [

11].

Riemann’s own method of in-depth research, which was fortunately restored by Siegel in 1932 from the Riemann vestigial manuscript [

1], is now well known as the Riemann-Siegel formula [

11]. It is much more efficient than the Euler-Maclaurin formula, and was used to successfully calculate the first 3 approximate values of the imaginary parts of the nontrivial zeros on the critical line [1, p.134~137/168 -

Figure 1] [

11] by hand.

Remark: sometimes, in this paper, the values of the imaginary parts of the nontrivial zeros on the critical line are abbreviated as the zeros values, or zeros or tn.

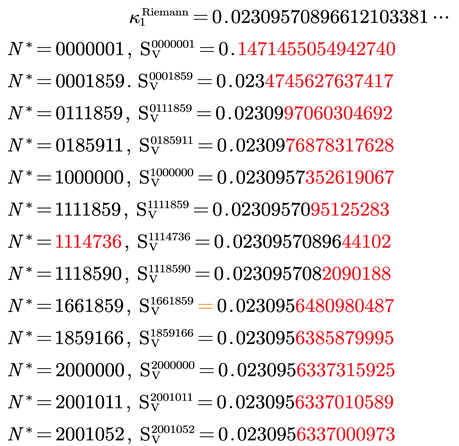

As can be seen from

Table 1, the first three best zeros with

tn /2π rather than

tn approximated by Riemann are very close to the current ones [

12].

1.2.2 Based on the cumbersome and complex calculations for the nontrivial zeros on the critical line, and the fact that numerical calculations in Riemann's era were all done manually, this elementary calculation method was not well suited for calculating nontrivial zeros beyond. After determining the first three nontrivial zeros, Riemann turned to estimating the number of the nontrivial zeros on in a given range.

“He then goes on to say that the number of roots

ρ whose imaginary parts lie between 0 and

T is approximately” [3, p.18] [

1]

where,

N(

T) denotes the number of the nontrivial zeros of Riemann

ζ(

s) function in the region 0 < Re(

s) < 1, 0 < Im(

s) <

T. It also implies that

N(

T) approaches infinity as

T → ∞. In 1905, the relationship above in equation [

13] [5, p.17] was proven by von Mangoldt.

But it is still unknown whether this conclusion is also correct on line segment from 1/2 to 1/2+

iT [3, p. 38]. In 1914, Hardy proved that there are infinitely many nontrivial zeros on the critical line [

14]. With this and Section 1.2.1 above, the profile of the nontrivial zeros located on the critical line is basically clear—as long as one keeps calculating forever if necessary.

1.2.3 However, Riemann's formula for

N(

T) cannot determine whether there are the nontrivial zeros outside the critical line. This problem troubled Riemann since his paper and was also something he tried his best to solve but was not able to accomplish until his death. In such circumstances, “we can never know what led Riemann to say it was ‘probable’ that the roots

ρ all lie on the line Re(s) = 1/2” [3, p.164], but as such, the Riemann Hypothesis was born in his paper [

2].

2. Notation and Preparation

2.1. Main Notations

RxF, RzF: the Riemann and Functions, respectively.

CL, CS: the Critical Line and Critical Strip, respectively.

: the constant using for the critical line and this paper.

: the imaginary unit.

: the ordinal numbers.

: the total numbers of within or .

: a finite quantity setting in the analysis.

: the ordinal numbers or the natural numbers.

: the total numbers of the nontrivial zeros of RzF on the line, .

: the total (Hardy) numbers of the nontrivial zeros [

13] of RzF on the upper half of CL.

: the number of the nontrivial zeros of RzF in CL with .

: a complex variable or number on the whole Complex Plane.

: the imaginary part of the nontrivial zero of RzF on the line, .

: the imaginary part of the nontrivial zero of RzF on the upper half of CL.

: a limiting quantity for describing the value of the imaginary part of nontrivial zeros on CL in the analysis of the Riemann hypothesis. .

: the Euler- Mascheroni constant, .

: a very small positive quantity introduced to avoid errors and enhance amplification effects.

: the horizontal offset that deviates from the critical line; .

: a constant; the quantity of the reciprocal sum formula for all the nontrivial zeros of RzF.

: the quantity of the reciprocal sum formula for all the nontrivial zeros of RzF in .

the quantity of the reciprocal sum formula for all the nontrivial zeros of RzF in .

: the constant, the quantity of the product formula of RxF at .

: the nontrivial zeros of Riemann function.

: a nontrivial zero of Riemann function.

: a nontrivial zero of Riemann function on the critical line.

: a nontrivial zero of Riemann function within .

: a nontrivial zero of RzF on the line, within .

: a nontrivial zero of RzF on the line, within .

: The counting function of primes.

: the point Set denoted within the area, on the Complex Plan; The region, is named the Critical Strip.

: the point Set denoted on the line, , which is called the Critical Line.

: the point Set denoted in the critical strip other than the critical line; .

: the left part and the right part of split by the critical line; .

2.2. Preparation

Property 1. All nontrivial zeros of RzF and All (nontrivial) zeros of RxF are coincident.

Property 2. All nontrivial zeros of Riemann

function are located within

[

8,

9].

Property 3. All nontrivial zeros of RzF or RxF only form in the complex number.

Theorem 1. There are infinitely many nontrivial zeros of RzF on the critical line [

14].

Theorem 2. The weak relationship [5, p.20] between tn and n is stated as

(A) .

Thus, the mean gapping gn between tn+1 and tn is

(B) ,

which approaches 0 as

n → ∞ [

15].

These are two of corollaries of the Riemann-von Mangoldt formula (theorem) [

13] [5, p.17]:

, with .