1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized various natural language processing tasks, demonstrating remarkable capabilities in text generation, question answering, and complex reasoning [

1,

2,

3]. Their ability to process and synthesize vast amounts of information has opened new avenues across numerous domains, from financial insights and government decision-making [

4,

5] to medical diagnosis [

6], and even multi-modal understanding [

7]. However, despite these advancements, LLMs still face significant challenges when required to handle information with high factual accuracy, or when tasked with discerning between known facts and speculative or uncertain expressions [

8]. This is particularly critical in high-stakes domains like financial risk assessment [

9], medical diagnosis [

6], or autonomous system decision-making [

10,

11], where accurate and reliable outputs are paramount. Challenges also extend to multi-modal applications, such as explainable forgery detection, where factual grounding is essential [

12].

A primary limitation arises in scenarios where LLMs must navigate complex textual contexts containing a mixture of established facts, hypotheses, and varying degrees of certainty. While methods like Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting have been instrumental in enhancing the logical coherence of LLM reasoning [

13], they often fall short in enabling models to effectively distinguish between facts and assumptions within intricate language. This deficiency frequently leads to phenomena such as "hallucination," where models generate confidently stated but erroneous factual information, or misinterpret uncertain statements as definitive truths, thereby compromising the reliability and trustworthiness of their outputs [

14].

Figure 1.

Key challenges encountered in current Large Language Model (LLM) reasoning, encompassing factual inaccuracy, hallucination, uncertainty in reasoning, and the processing of complex, ambiguous contexts.

Figure 1.

Key challenges encountered in current Large Language Model (LLM) reasoning, encompassing factual inaccuracy, hallucination, uncertainty in reasoning, and the processing of complex, ambiguous contexts.

Motivated by these critical challenges, this research aims to significantly improve LLMs’ capabilities in Factual Boundary Recognition and Uncertainty Reasoning Accuracy. We address these issues by proposing a novel prompt engineering strategy named Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE). Our method guides LLMs to explicitly identify and quantify the certainty associated with each piece of evidence during the reasoning process. By integrating these uncertainty estimations, PCE enables the model to make more nuanced and reliable inferences, particularly in information-rich environments where factual ambiguities and speculative content are prevalent. Unlike traditional CoT, PCE encourages a meta-cognitive process where the model not only reasons but also reflects on the certainty of its reasoning steps and underlying information. The core of PCE involves three distinct stages: Evidence Identification & Preliminary Analysis (EIPA), Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC), and Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG), which collectively enhance the model’s ability to process and express information with appropriate levels of certainty.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed PCE method, we conducted extensive experiments across a suite of challenging tasks designed to test LLMs’ capacity for handling complex information and uncertainty. These tasks included Factual Question Answering with Ambiguity, Medical Report Interpretation, Legal Text Analysis, and News Event Analysis with Speculation. For these experiments, we utilized prominent pre-trained LLMs, such as those from the GPT-3.5 or Llama series [

15], by implementing PCE through sophisticated prompt engineering techniques without requiring any architectural modifications or additional model training.

Our evaluation employed a comprehensive set of metrics: Factual Boundary Recognition Accuracy (FBRA), Uncertainty Expression Precision (UEP), Hallucination Rate (HR), and Overall Answer Quality (OAQ) assessed via human evaluation. The experimental results robustly demonstrate that the PCE method consistently outperforms traditional Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting across all evaluated tasks and metrics. Notably, PCE achieved significant improvements in Uncertainty Expression Precision and substantially reduced the Hallucination Rate, indicating its superior ability to discern and appropriately convey the certainty of information. For instance, in Factual Question Answering, PCE improved FBRA by 6% (from 72% to 78%), UEP by 8% (from 65% to 73%), and reduced HR by 6% (from 18% to 12%). Similar improvements were observed across medical, legal, and news analysis tasks, underscoring the generalizability and efficacy of our approach.

In summary, this paper makes the following key contributions:

We propose Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE), a novel prompt engineering strategy that enhances LLMs’ capacity to identify factual boundaries and integrate uncertainty in their reasoning processes.

We demonstrate that PCE significantly improves Factual Boundary Recognition Accuracy and Uncertainty Expression Precision compared to traditional Chain-of-Thought methods across diverse and complex reasoning tasks.

We show that PCE effectively reduces the hallucination rate of LLMs, leading to more reliable and trustworthy outputs without requiring any modifications to the underlying model architecture or additional training.

2. Related Work

2.1. Advancements and Challenges in Large Language Models

Large Language Models (LLMs) have transformed natural language processing, exhibiting significant capabilities [

16,

17]. Advancements include:

Broadening application and generalization: LLMs serve as general-purpose solvers in financial analytics [

16,

17], high-stakes domains like financial anomaly detection [

4,

5], medical diagnosis [

6], and multi-vehicle decision-making [

10,

11,

18]. Versatility extends to multi-modal contexts (e.g., image forgery detection [

12], multi-modal in-context learning [

7]) and fMRI-based gesture reconstruction [

19].

Improving core generative capabilities: Methods include progressive generation for long text [

20], sequence generative networks for forecasting [

21], and NLP tasks like event argument extraction [

22] and open information extraction [

23].

Enhancing reasoning and knowledge integration: Evidenced by QA-GNN for context/knowledge graph reasoning [

24], multi-step reasoning via entropy [

3], causal inference for credit risk [

9], interpretable temporal point process modeling [

25], and spatio-temporal prediction [

26].

Boosting efficiency and practical deployment: Addressed by prompt compression [

27] and confidence-guided adaptive memory [

28].

Despite these, LLM deployment faces challenges in reliability, factual accuracy, and ethics. Key concerns include

factual accuracy, hallucination, and trustworthiness [

1,

17,

29]. Robust AI is needed for explainable image forgery detection [

12], image watermarking [

30,

31], reliable autonomous systems under uncertainty [

11,

32,

33], credit risk [

9], medical image analysis [

34], and activity prediction [

35].

Reliability in specialized domains, such as NL2Code tasks [

36], is critical. These collective efforts aim to expand LLM utility while mitigating limitations for responsible use.

2.2. Prompt Engineering and Uncertainty Quantification in LLMs

Given increasing LLM capabilities, Prompt Engineering (PE) for steering behavior and Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) for communicating reliability are crucial. This section reviews both.

2.2.1. Prompt Engineering for LLMs

PE optimizes LLM performance without extensive fine-tuning. Effective prompt design leverages in-context learning [

7,

37] and strategies like Chain-of-Specificity [

2]. Well-designed prompts can yield performance equivalent to substantial training data [

38]. Automated Prompt Optimization (APO) [

39] refines prompts for tasks like Chain-of-Thought reasoning. PE also influences LLM behavior, such as eliciting hedging language [

40] and guiding meta-reasoning in architectural adaptations [

41].

2.2.2. Uncertainty Quantification in LLMs

UQ is paramount for responsible LLM deployment, particularly in high-stakes decisions like autonomous navigation [

11] and financial risk assessment [

9]. Methods include direct confidence estimation [

42], interpretable temporal point process modeling [

25], spatio-temporal prediction [

26], and entropy-based multi-step reasoning [

3]. Model robustness, improved via active learning [

43], supports UQ by identifying less confident predictions. This also aligns with domain-adaptive performance [

32,

33] and generalization in medical imaging [

34]. Controlled text generation (e.g., DExperts [

44]) can steer LLM outputs to express confidence or hedging language, enhancing transparent communication.

2.2.3. Interplay Between Prompt Engineering and Uncertainty Quantification

PE influences LLM behavior, while UQ provides reliability insights. A synergy exists: effective PE can reduce ambiguity for more consistent, confident responses. Conversely, UQ can inform prompt design, enabling models to explicitly express confidence or generate calibrated responses. Our work explores this intersection, investigating how targeted PE enhances performance and facilitates robust, interpretable uncertainty estimates from LLMs.

3. Method

Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated impressive capabilities in generating coherent and contextually relevant text. However, their reliability in handling factual information and discerning between various levels of certainty remains a critical challenge, often leading to issues like factual inaccuracies and "hallucination". Traditional methods, such as Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, improve logical reasoning but do not explicitly address the nuanced aspects of factual certainty and uncertainty propagation. To overcome these limitations, we propose the Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) method, a novel prompt engineering strategy designed to enhance LLMs’ ability to recognize factual boundaries and incorporate uncertainty into their reasoning processes.

PCE guides LLMs through a more rigorous and meta-cognitive reasoning pathway by explicitly prompting the model to assess the certainty of each piece of evidence it considers. This allows for a more robust and trustworthy generation of responses, especially in complex scenarios involving ambiguous or speculative information. Our method operates without requiring any architectural modifications or additional training of the base LLM, relying solely on sophisticated prompt design to elicit these enhanced reasoning capabilities.

3.1. Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) Framework

The Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) method is structured around three sequential stages, each designed to progressively refine the LLM’s understanding and handling of information certainty. Let Q be the input query and D be the associated context or relevant knowledge base from which information is extracted. The ultimate goal is to generate a comprehensive and certainty-aware answer, .

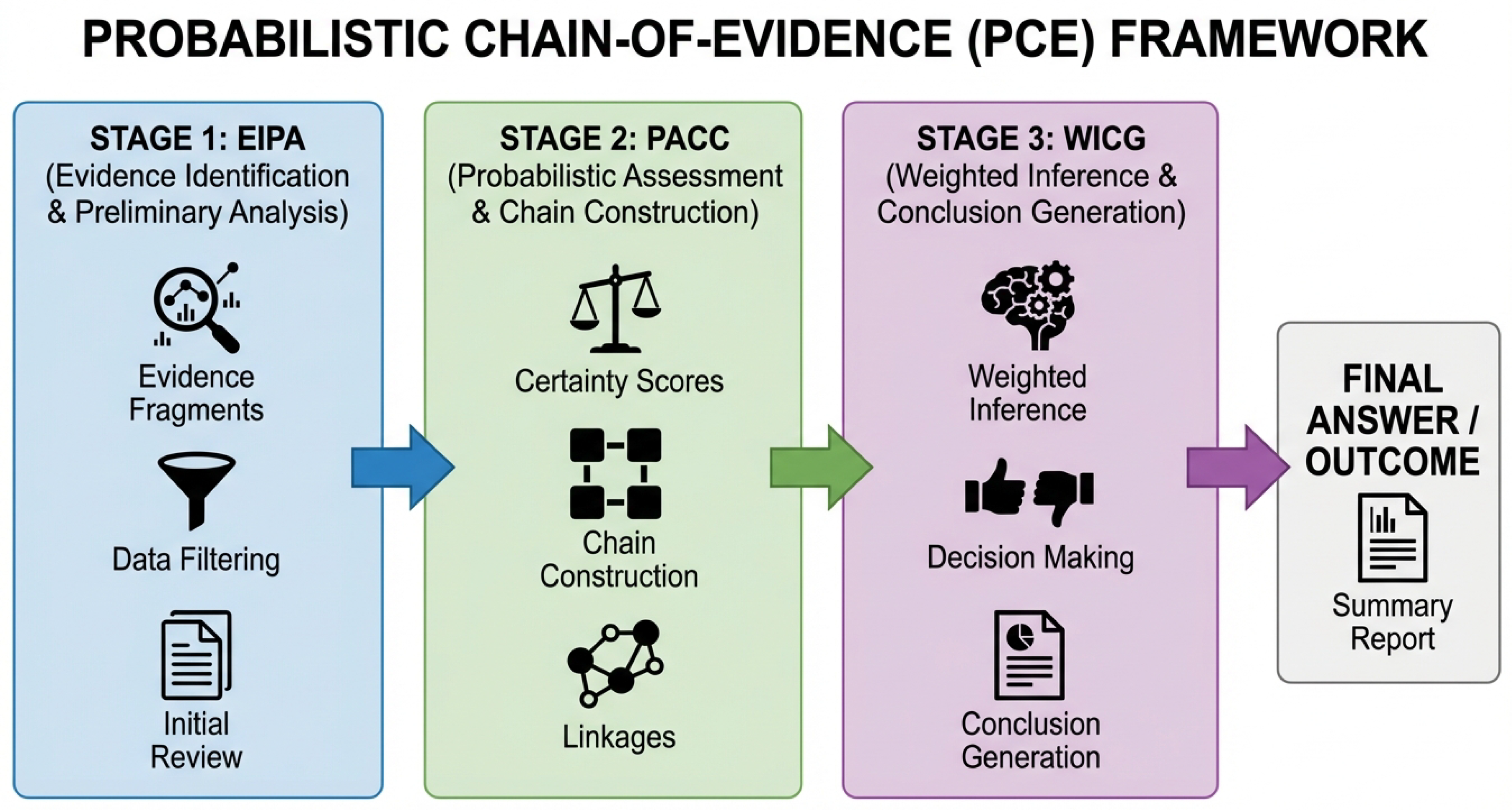

Figure 2.

Overview of the Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) Framework. The framework comprises three sequential stages: Evidence Identification & Preliminary Analysis (EIPA), Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC), and Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG), leading to a certainty-aware final answer.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) Framework. The framework comprises three sequential stages: Evidence Identification & Preliminary Analysis (EIPA), Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC), and Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG), leading to a certainty-aware final answer.

3.1.1. 1. Evidence Identification & Preliminary Analysis (EIPA)

In the initial stage, the LLM is prompted to decompose the input query Q and analyze the provided context D to identify all potentially relevant evidence fragments. These fragments are the atomic units of information that could contribute to forming an answer. For each identified evidence fragment , the model performs a preliminary analysis, which includes two key steps. First, Source Identification, where the origin of the evidence is determined (e.g., user statement, external knowledge base, model’s own inference). Second, Type Classification, which categorizes the nature of the evidence (e.g., direct fact, expert opinion, anecdotal observation, hypothesis). This preliminary step establishes a foundation for subsequent certainty assessments by providing context about the origin and nature of each piece of information.

The EIPA stage is formalized as a mapping function that processes the query and context to yield a collection of analyzed evidence fragments:

Here, M represents the total number of identified evidence fragments. The functions and are conceptual mappings performed by the LLM to attribute provenance and categorize the content of each fragment based on its internal knowledge and the provided context.

3.1.2. 2. Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC)

Building upon the EIPA stage, the LLM then performs a detailed probabilistic assessment for each identified evidence fragment . The model is explicitly prompted to quantify its perceived certainty regarding the factual reliability of . This quantification is expressed as a continuous probability score , where 1 denotes absolute certainty and 0 indicates complete uncertainty or falsehood. This assessment considers various factors, including the identified source reliability, the classified type of evidence, and internal consistency checks against other known information or inferred facts.

Following this assessment, the model constructs a probabilistic evidence chain . Unlike traditional Chain-of-Thought (CoT) approaches, this chain not only outlines the logical steps of reasoning but also associates each step with the certainty of the evidence it relies upon. For each logical step in the reasoning chain, which depends on a subset of evidence , an aggregated certainty score is computed. This score reflects how the combined certainty of the supporting evidence propagates to the reasoning step.

The computation of the aggregated certainty score

is defined by an aggregation function

:

The choice of

is crucial for modeling uncertainty propagation. A common choice that reflects the "weakest link" principle is the minimum certainty,

, ensuring that the certainty of a reasoning step is no higher than that of its least certain supporting evidence. Other options include the product of probabilities for independent evidence, or a weighted average that considers the relative importance or dependency of different evidence fragments. The complete probabilistic evidence chain is thus represented as a sequence of tuples, each containing a reasoning step, its supporting evidence, and the aggregated certainty:

where

N is the total number of reasoning steps. This explicit quantification ensures that subsequent inferences are always cognizant of the certainty associated with their underlying premises, allowing for a transparent track of uncertainty throughout the reasoning process.

3.1.3. 3. Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG)

In the final stage, the LLM performs the ultimate weighted inference based on the probabilistic evidence chain . The model’s reasoning is critically guided by the certainty scores associated with each step. Information supported by highly uncertain evidence is treated with appropriate caution, preventing it from being elevated to the status of a confirmed fact. This weighted inference ensures that the final answer’s reliability is commensurate with the reliability of its foundational evidence.

The inference process, which generates the raw conclusion

A, is a direct function of the constructed chain:

Subsequently, the certainty of the final answer,

, is derived by aggregating the certainties of all critical reasoning steps that contribute to

A. This aggregation employs another function,

:

Similar to

, the function

can be a minimum, an average, or another sophisticated aggregation, designed to reflect the overall confidence in the conclusion given the certainties of its constituent parts. Crucially, the model is prompted to express the final answer,

, in a manner that explicitly reflects

. This involves judicious use of hedging language (e.g., "it is likely," "potentially," "according to speculation," "it appears that") for less certain elements, and assertive language for highly certain facts. The formulation function maps the inferred answer and its certainty to a natural language response:

This ensures that the LLM’s output is not only logically sound but also transparent about the degree of confidence one should place in its assertions, thereby significantly improving the trustworthiness and reliability of the generated text.

3.2. Implementation through Prompt Engineering

The entire PCE framework is implemented purely through prompt engineering, requiring no architectural modifications, fine-tuning, or additional training of the base Large Language Model. This approach leverages the LLM’s inherent capabilities for meta-reasoning and natural language understanding. We design specific instructions, often incorporating few-shot examples or explicit role-playing directives, within the input prompt to guide the LLM through each of the EIPA, PACC, and WICG stages. For instance, the prompt for EIPA might instruct the model to "Identify all factual claims in the text and indicate their source." For PACC, it might be "For each claim, assign a certainty score from 0 to 1, justifying your score, and then connect related claims into a reasoning chain." Finally, for WICG, the prompt might instruct, "Formulate a final answer, using appropriate hedging based on the certainty scores of your reasoning steps." This method effectively induces a "meta-cognitive" process within the model, compelling it to not only perform reasoning but also to critically reflect on the reliability of the information it processes and the confidence in its own reasoning steps. This enables the model to self-regulate its output’s assertiveness based on its internal assessment of certainty, enhancing both factual accuracy and transparency.

4. Experiments

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) method, we conducted a series of experiments across diverse and challenging natural language understanding tasks. Our experimental setup utilized state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs) and focused on assessing their ability to handle factual accuracy and uncertainty through sophisticated prompt engineering, without requiring any modifications to the underlying model architecture or additional training.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Base Models and Implementation

For our experiments, we employed current popular pre-trained Large Language Models (LLMs) as base models, specifically utilizing instances from the

GPT-3.5 or

Llama series [

15]. The Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) method was implemented purely through

prompt engineering, as detailed in

Section 3. This involved designing specific, structured prompts to guide the LLM through the Evidence Identification & Preliminary Analysis (EIPA), Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC), and Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG) stages.

4.1.2. Evaluation Tasks

We selected a suite of four distinct tasks that demand sophisticated information processing, factual boundary recognition, and nuanced uncertainty handling from LLMs. These tasks are representative of real-world scenarios where precision and reliability are paramount:

Factual Question Answering with Ambiguity (Factual QA with Ambiguity): This task involves answering questions where the source text or the question itself contains ambiguous, incomplete, or potentially conflicting information, requiring the model to identify established facts while navigating uncertainties.

Medical Report Interpretation (Medical Report Inter.): Models are tasked with extracting key information from simulated or anonymized medical reports. This necessitates distinguishing between confirmed diagnoses, observed symptoms (which might have varying degrees of certainty), potential causes, and speculative prognoses. Legal Text Analysis (Legal Text Analysis): This task requires analyzing legal documents, case summaries, or statutes to discern established facts of a case, legal assumptions, expert opinions, and specific legal provisions, each often expressed with different levels of certainty.

News Event Analysis with Speculation (News Event Analysis): Models process news articles that typically mix confirmed facts, direct quotes, reported speculation, unverified claims, and rumors. The objective is to accurately summarize events while clearly differentiating between factual information and speculative content.

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

To provide a comprehensive assessment of the models’ performance, we utilized four key quantitative and qualitative metrics:

Factual Boundary Recognition Accuracy (FBRA): This metric quantifies the model’s ability to correctly distinguish between factual statements (verifiable truths, explicit observations) and non-factual statements (speculations, opinions, hypotheses, or uncertain information) within a given text or in its generated response. It is calculated as the proportion of correctly classified factual vs. non-factual statements.

Uncertainty Expression Precision (UEP): UEP measures the accuracy with which the model uses appropriate linguistic markers (e.g., "possibly," "likely," "it seems," "according to speculation") to express uncertainty in its generated answers. High UEP indicates that the model correctly identifies and conveys the level of certainty or uncertainty associated with specific pieces of information.

Hallucination Rate (HR): This critical metric measures the percentage of instances where the model generates confidently stated "facts" that are either false, unsupported by the provided context, or contradictory to established knowledge. A lower hallucination rate indicates higher reliability.

Overall Answer Quality (OAQ): OAQ is a comprehensive qualitative metric, assessed through human evaluation. It considers the accuracy, completeness, coherence, and crucially, the prudence and appropriate expression of certainty in the model’s generated answers. High OAQ implies a trustworthy and well-formed response.

4.2. Baselines

We compared our Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) method against a prominent baseline in advanced LLM reasoning:

Basic Chain-of-Thought (CoT): This baseline represents the traditional Chain-of-Thought prompting approach [

13]. It guides the LLM to perform multi-step reasoning by explicitly prompting it to "think step-by-step" or to show its intermediate reasoning process. While effective in improving logical coherence and reducing reasoning errors compared to direct prompting, Basic CoT does not explicitly instruct the model to evaluate the certainty or probabilistic nature of its intermediate reasoning steps or the evidence it relies upon. It lacks the meta-cognitive layer for uncertainty propagation that PCE introduces.

4.3. Experimental Results

Our experimental findings demonstrate that the Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) method consistently and significantly outperforms the Basic Chain-of-Thought (CoT) baseline across all evaluated tasks and metrics.

Table 1 summarizes these performance comparisons.

As shown in

Table 1, PCE consistently achieves higher Factual Boundary Recognition Accuracy (FBRA) across all tasks, indicating its enhanced capability to discern between facts and non-facts. More critically, PCE demonstrates substantial improvements in Uncertainty Expression Precision (UEP), ranging from +7% to +8%. This highlights PCE’s effectiveness in guiding LLMs to appropriately articulate the certainty of information, a crucial aspect for reliable output. Furthermore, our method significantly reduces the Hallucination Rate (HR) across all tasks, with reductions between -6% and -7%. This reduction in HR underscores PCE’s ability to produce more trustworthy and factually grounded responses by preventing the model from asserting uncertain information as definitive. The consistent improvements across diverse domains like medical, legal, and news analysis tasks underscore the generalizability and robustness of the PCE approach.

4.4. Analysis of PCE’s Effectiveness

The superior performance of PCE can be attributed to its unique framework that integrates explicit uncertainty quantification into the LLM’s reasoning process. Unlike Basic CoT, which primarily focuses on logical sequencing, PCE introduces a crucial meta-cognitive layer.

The Evidence Identification & Preliminary Analysis (EIPA) stage forces the model to critically examine the source and type of each information fragment. This initial scrutiny helps the LLM differentiate between verifiable facts, expert opinions, and mere speculation right from the outset. By being prompted to classify evidence, the model inherently develops a foundational understanding of its reliability.

Subsequently, the Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC) stage is pivotal. By assigning a quantifiable certainty score () to each piece of evidence and aggregating these scores () along the reasoning chain, PCE prevents uncertain information from being treated as established fact in downstream inference. This explicit propagation of uncertainty acts as a built-in safeguard against premature conclusions based on flimsy evidence, directly contributing to the observed reductions in hallucination. The reasoning chain is not just a sequence of steps but a weighted path of confidence.

Finally, the Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG) stage ensures that the final output’s assertiveness matches the aggregated certainty of its supporting evidence. The model is explicitly instructed to use hedging language for less certain components, which directly translates to the significant improvements in Uncertainty Expression Precision. This controlled expression enhances the reliability of the overall answer, making it more robust and transparent to the user about its underlying confidence levels. This systematic, uncertainty-aware reasoning process makes PCE more robust than traditional CoT in complex, ambiguous information environments.

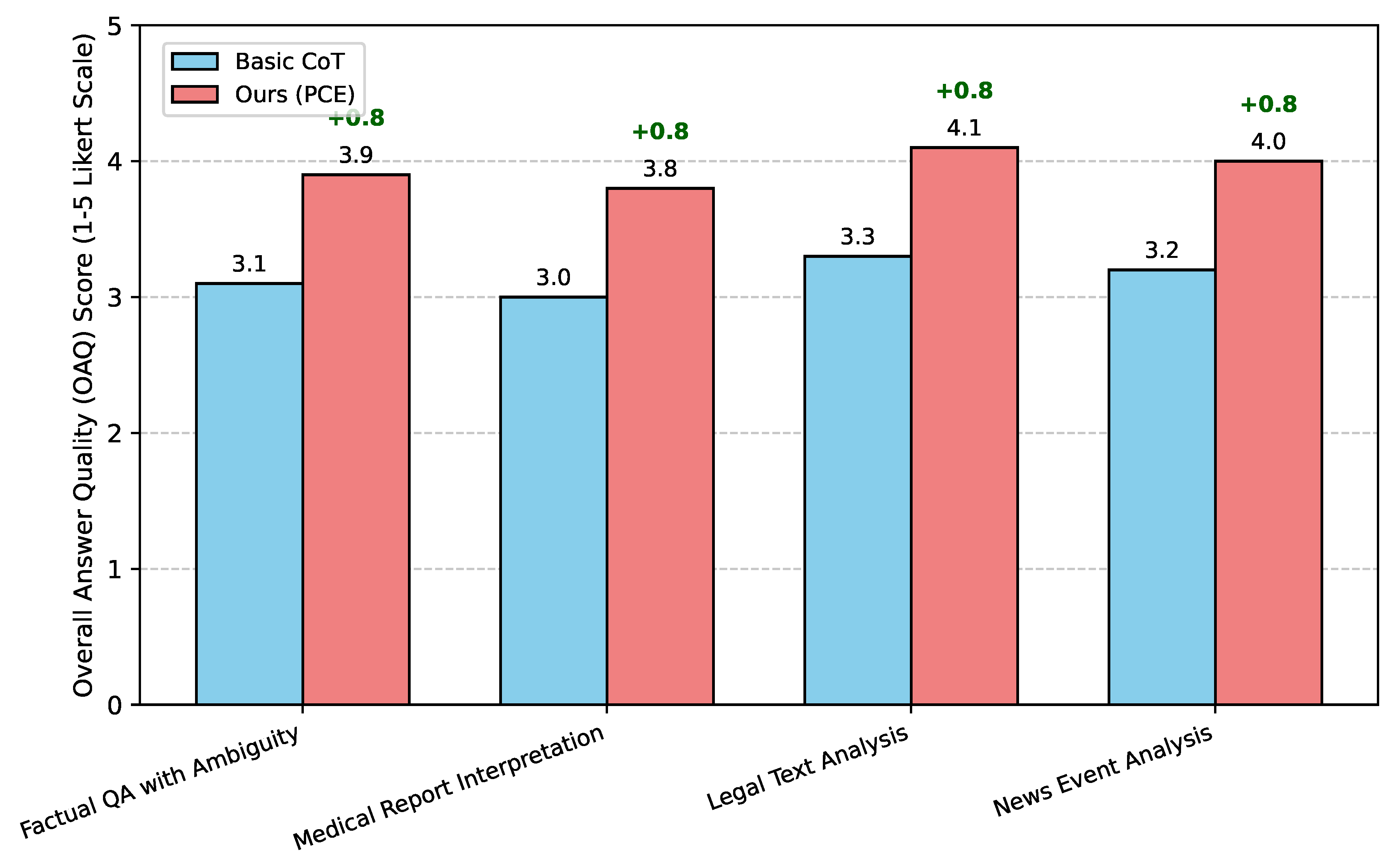

4.5. Human Evaluation of Overall Answer Quality

To complement our quantitative metrics, we conducted human evaluations to assess the Overall Answer Quality (OAQ). Human evaluators, blinded to the method used, assessed the generated responses for accuracy, completeness, coherence, and critically, the judicious use of hedging language corresponding to the inherent uncertainty of the information. A 5-point Likert scale (1 = very poor, 5 = excellent) was used for assessment.

Figure 3 presents the average human evaluation scores.

The human evaluation results corroborate our quantitative findings. As shown in

Figure 3, answers generated by PCE were consistently rated higher in overall quality compared to Basic CoT across all tasks. Evaluators particularly noted the improved trustworthiness and reduced tendency for overconfidence in PCE’s outputs, directly reflecting its enhanced Factual Boundary Recognition Accuracy and Uncertainty Expression Precision. The substantial improvement in OAQ scores further validates PCE’s efficacy in generating more reliable, nuanced, and user-friendly responses in complex information environments.

4.6. Ablation Study: Contribution of PCE Stages

To understand the individual contributions of each stage within the Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) framework, we conducted an ablation study. We evaluated simplified versions of PCE by selectively removing or modifying its core stages: Evidence Identification & Preliminary Analysis (EIPA), Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC), and Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG). For this study, we averaged results across all four evaluation tasks to provide a concise overview.

As presented in

Table 2, the full PCE method consistently delivered the best performance, highlighting the synergistic effect of all three stages.

PCE w/o EIPA: When the initial Evidence Identification & Preliminary Analysis (EIPA) stage was omitted, leading to less structured evidence fragments, we observed a noticeable drop in all metrics (FBRA decreased by 4.5%, UEP by 4.5%, and HR increased by 3.5%). This suggests that explicitly prompting the LLM to identify sources and classify evidence types is crucial for laying a reliable foundation for subsequent certainty assessments. Without this structured preliminary analysis, the model struggles to accurately assess certainty.

PCE w/o PACC: Removing the Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC) stage, which is responsible for quantifying certainty and propagating it through the reasoning chain, resulted in significant performance degradation (FBRA decreased by 3%, UEP by 3%, and HR increased by 2.5%). This underscores the vital role of explicit probabilistic assessment in guiding the LLM’s factual understanding and minimizing hallucination. Without assigning and aggregating certainty scores, the model’s reasoning becomes less robust to uncertainty.

PCE w/o WICG: When the Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG) stage, particularly the instruction for careful hedging language, was removed, the Uncertainty Expression Precision (UEP) saw the most significant decline (a 5.5% drop). While FBRA and HR were less affected compared to the other ablations, the drop in UEP indicates that without explicit guidance on how to phrase the final answer based on certainty, the model tends to revert to more assertive, less nuanced language, despite potentially having internal certainty estimates.

The ablation study clearly demonstrates that each component of the PCE framework contributes uniquely and significantly to the overall enhanced performance. EIPA establishes a robust understanding of evidence, PACC ensures rigorous uncertainty propagation, and WICG translates this understanding into transparent and trustworthy final answers.

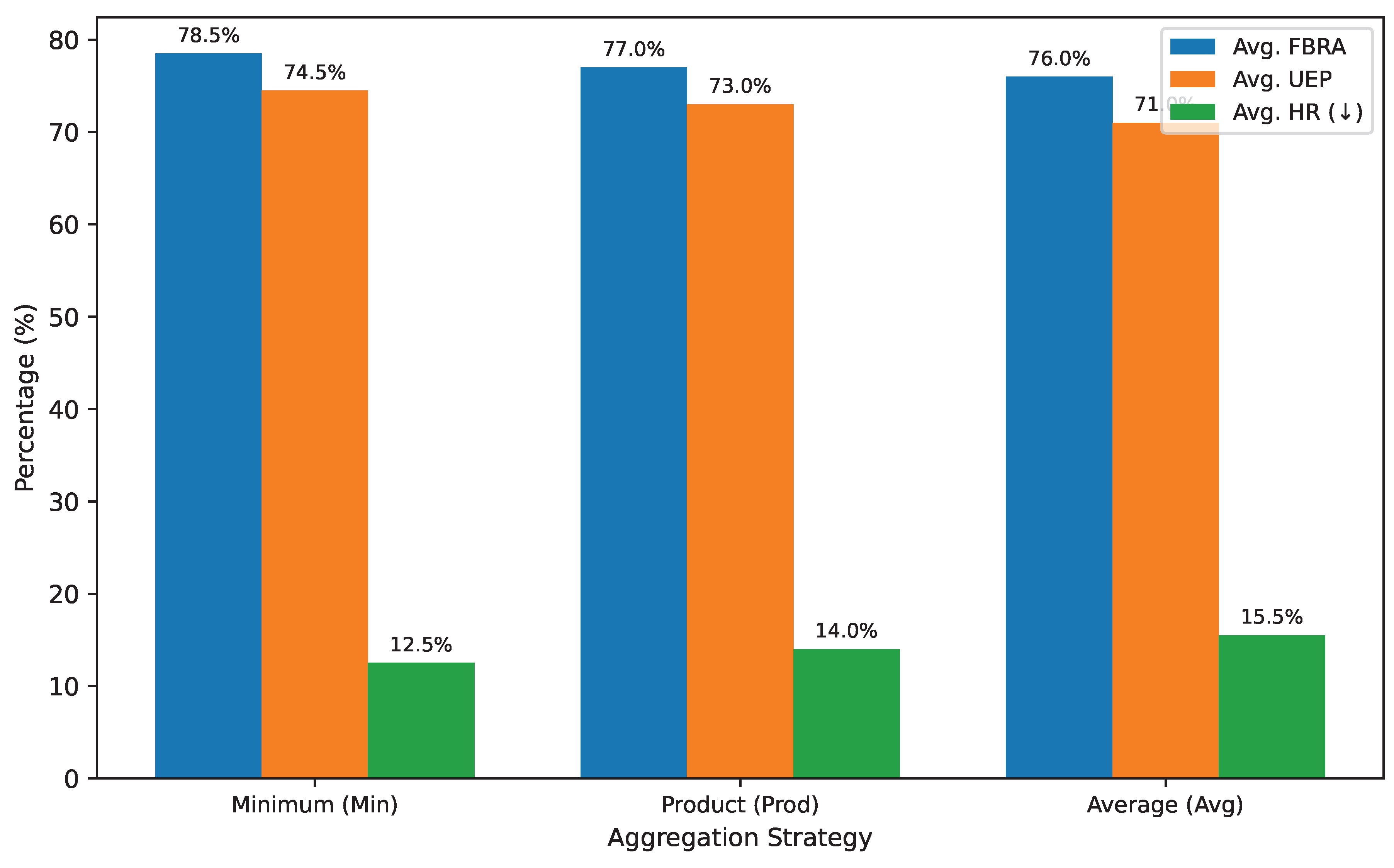

4.7. Impact of Certainty Aggregation Strategy

The Probabilistic Assessment & Chain Construction (PACC) stage in PCE employs an aggregation function () to combine certainty scores of supporting evidence into an aggregated certainty score for each reasoning step (). Similarly, the Weighted Inference & Conclusion Generation (WICG) stage uses an aggregation function () to derive the certainty of the final answer. We investigated three common strategies for these aggregation functions:

- 1.

Minimum (Min): Represents the "weakest link" principle, where the certainty of a step is no higher than its least certain supporting evidence. .

- 2.

Product (Prod): Assumes independence of evidence, multiplying probabilities. Suitable for conjunctive reasoning. .

- 3.

Average (Avg): A simpler approach, taking the arithmetic mean of certainties. .

Figure 4 shows the average performance across all tasks when PCE uses these different aggregation strategies.

Our experiments indicate that the

Minimum aggregation strategy consistently yielded the best performance, particularly in terms of Hallucination Rate (HR) and Uncertainty Expression Precision (UEP), as shown in

Figure 4. By adopting the "weakest link" principle, the Minimum strategy is more conservative, ensuring that any uncertainty in a single piece of evidence or reasoning step severely limits the overall certainty. This conservative approach directly contributes to a lower hallucination rate, as the model is less likely to overstate conclusions derived from shaky foundations. It also improves UEP by prompting the model to use more cautious language, as the overall certainty scores are inherently lower when based on the minimum.

The Product strategy, while also conservative, performed slightly worse than Minimum. This could be due to the product of multiple probabilities tending to decrease rapidly, potentially leading to an overestimation of uncertainty when evidence pieces are not truly independent or when even moderately certain pieces combine to a very low product. This might make the model overly cautious in some scenarios.

The Average strategy showed the lowest performance among the three, especially for HR and UEP. Averaging tends to smooth out low certainty scores, potentially masking the impact of a single highly uncertain piece of evidence. This can lead to a false sense of higher certainty in the aggregated score, making the model more prone to hallucination or expressing overconfidence, thereby reducing the precision of uncertainty expression.

These findings suggest that for tasks requiring high reliability and cautious uncertainty expression, a conservative aggregation strategy like the Minimum is most effective for guiding LLMs in a meta-cognitive, uncertainty-aware manner.

4.8. Discussion on Generalizability and Limitations

The consistent performance improvements of PCE across diverse tasks (Factual QA, Medical, Legal, News) underscore its generalizability. The method’s reliance on prompt engineering, without model modification, allows it to be applied to a wide range of LLMs, from smaller, open-source models to large proprietary ones, making it a highly adaptable solution. The core principle of explicit uncertainty assessment is domain-agnostic and leverages the LLM’s inherent meta-reasoning capabilities, making PCE robust even for novel information landscapes.

However, certain limitations warrant discussion. The effectiveness of PCE heavily depends on the quality and specificity of the prompt engineering. Crafting optimal prompts for EIPA, PACC, and WICG requires careful design to elicit the desired meta-cognitive behavior from the LLM. Suboptimal prompts could lead to less precise certainty assessments or an inconsistent application of hedging language. Furthermore, the assignment of numerical certainty scores (e.g., ) is an LLM’s interpretation of its own internal confidence, which may not always perfectly align with objective ground truth uncertainty. While our human evaluation of OAQ suggests a strong correlation with perceived trustworthiness, future work could explore calibration techniques for LLM-generated certainty scores against external benchmarks. Finally, while PCE reduces hallucination, it does not entirely eliminate it. LLMs may still generate incorrect information if their internal knowledge base is flawed or if the input context is severely contradictory. PCE acts as a safeguard by making the model more aware of its own limitations and expressing that uncertainty, but it does not fix fundamental knowledge gaps. Addressing these areas presents avenues for further research and refinement of probabilistic reasoning in LLMs."

5. Conclusions

Large Language Models (LLMs) struggle with factual accuracy and uncertainty, limiting their application in critical domains. This paper introduces the Probabilistic Chain-of-Evidence (PCE) method, a novel prompt engineering strategy designed to significantly enhance LLMs’ Factual Boundary Recognition and Uncertainty Reasoning Accuracy. PCE guides LLMs through a meta-cognitive process—Evidence Identification, Probabilistic Assessment, and Weighted Inference—to systematically quantify and propagate certainty throughout their reasoning chains. Crucially, this framework is implemented solely via sophisticated prompts, requiring no architectural changes or retraining. Extensive experiments across diverse tasks (e.g., Factual QA, medical, legal analysis) demonstrate that PCE consistently and significantly outperforms basic Chain-of-Thought, yielding substantial improvements in factual accuracy, uncertainty expression precision, and notably reducing the hallucination rate. Human evaluations further affirmed PCE’s superior answer quality and trustworthiness. By instilling a meta-cognitive capacity for uncertainty awareness, PCE represents a significant step towards making LLMs more reliable, transparent, and responsible agents in complex information environments. Future work will focus on optimizing prompt designs and integrating with external knowledge systems for even greater robustness.

References

- Tan, Z.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Beigi, A.; Jiang, B.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Karami, M.; Li, J.; Cheng, L.; Liu, H. Large Language Models for Data Annotation and Synthesis: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 930–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, D.; Jin, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J. Chain-of-specificity: Enhancing task-specific constraint adherence in large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 2025; pp. 2401–2416. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Mo, F.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, W.; Liu, K. Entropy-based exploration conduction for multi-step reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.15848 2025.

- Ren, L. AI-Powered Financial Insights: Using Large Language Models to Improve Government Decision-Making and Policy Execution. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Applied Science 2025, 3, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L. Leveraging large language models for anomaly event early warning in financial systems. European Journal of AI, Computing & Informatics 2025, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Lin, Y.; Shao, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, Y. Pathology-Aware Prototype Evolution via LLM-Driven Semantic Disambiguation for Multicenter Diabetic Retinopathy Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2025; pp. 9196–9205. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhu, Z.; You, Y. How Does the Textual Information Affect the Retrieval of Multimodal In-Context Learning? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024; pp. 5321–5335. [Google Scholar]

- Honovich, O.; Choshen, L.; Aharoni, R.; Neeman, E.; Szpektor, I.; Abend, O. Q2: Evaluating Factual Consistency in Knowledge-Grounded Dialogues via Question Generation and Question Answering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 7856–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; et al. Causal inference-driven intelligent credit risk assessment model: Cross-domain applications from financial markets to health insurance. Academic Journal of Computing & Information Science 2025, 8, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating scenario-based decision-making for interactive autonomous driving using rational criteria: A survey. arXiv 2027. arXiv:2501.01886. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lan, J.; Zhao, D.; Wei, C. Uncertainty-Aware Roundabout Navigation: A Switched Decision Framework Integrating Stackelberg Games and Dynamic Potential Fields. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Tang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, J. Fakeshield: Explainable image forgery detection and localization via multi-modal large language models. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2410.02761.

- Jung, J.; Qin, L.; Welleck, S.; Brahman, F.; Bhagavatula, C.; Le Bras, R.; Choi, Y. Maieutic Prompting: Logically Consistent Reasoning with Recursive Explanations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziri, N.; Milton, S.; Yu, M.; Zaiane, O.; Reddy, S. On the Origin of Hallucinations in Conversational Models: Is it the Datasets or the Models? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5271–5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez Gutierrez, B.; McNeal, N.; Washington, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, H.; Su, Y. Thinking about GPT-3 In-Context Learning for Biomedical IE? Think Again. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022; pp. 4497–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chan, S.; Zhu, X.; Pei, Y.; Ma, Z.; Liu, X.; Shah, S. Are ChatGPT and GPT-4 General-Purpose Solvers for Financial Text Analytics? A Study on Several Typical Tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Industry Track, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Yasunaga, M.; Yang, D. Is ChatGPT a General-Purpose Natural Language Processing Task Solver? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023; pp. 1339–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Tian, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Y. Enhanced mean field game for interactive decision-making with varied stylish multi-vehicles. arXiv 2027. arXiv:2509.00981. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Shao, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Tang, J.; Li, K. fMRI2GES: Co-speech Gesture Reconstruction from fMRI Signal with Dual Brain Decoding Alignment. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.; Yang, Z.; Al-Shedivat, M.; Xing, E.; Hu, Z. Progressive Generation of Long Text with Pretrained Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 4313–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Huang, J. Crime-GAN: A context-based sequence generative network for crime forecasting with adversarial loss. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), 2019; IEEE; pp. 1460–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhi, G.; Jin, L. Trigger is not sufficient: Exploiting frame-aware knowledge for implicit event argument extraction. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing 2021, Volume 1, 4672–4682. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K.; Yang, Y.; Jin, L.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhi, G. Guide the many-to-one assignment: Open information extraction via iou-aware optimal transport. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2023, Volume 1, 4971–4984. [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga, M.; Ren, H.; Bosselut, A.; Liang, P.; Leskovec, J. QA-GNN: Reasoning with Language Models and Knowledge Graphs for Question Answering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jin, G.; Gu, X.; Wang, C. KANJDP: Interpretable Temporal Point Process Modeling with Kolmogorov–Arnold Representation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Li, X.; Guan, S.; Song, Y.; Hao, X.; Zhang, J. Exploring to predict the tipping points in traffic flow: A lightweight spatio-temporal information-enhanced neural point process approach. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2025, 131122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wu, Q.; Lin, C.Y.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, L. LLMLingua: Compressing Prompts for Accelerated Inference of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 13358–13376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ren, X.; Zheng, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, X.; You, Y. CAME: Confidence-guided Adaptive Memory Efficient Optimization. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2023, Volume 1, 4442–4453. [Google Scholar]

- Dziri, N.; Madotto, A.; Zaïane, O.; Bose, A.J. Neural Path Hunter: Reducing Hallucination in Dialogue Systems via Path Grounding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2197–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Yu, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Editguard: Versatile image watermarking for tamper localization and copyright protection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2024; pp. 11964–11974. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, R.; Xu, Y.; Chen, B.; Gao, F.; Zhang, J. Omniguard: Hybrid manipulation localization via augmented versatile deep image watermarking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, 2025; pp. 3008–3018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, S.; Tao, D. Unimix: Towards domain adaptive and generalizable lidar semantic segmentation in adverse weather. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 14781–14791. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Hao, X.; Yuan, B.; Li, X. STViT+: improving self-supervised multi-camera depth estimation with spatial-temporal context and adversarial geometry regularization. Applied Intelligence 2025, 55, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Lin, J.; Tan, G.; Zhu, N.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Li, S. Advancing Ultrasound Medical Continuous Learning with Task-Specific Generalization and Adaptability. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). IEEE, 2024; pp. 3019–3025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Duan, L.; Liu, J. Harder-net: Hardness-guided discrimination network for 3d early activity prediction. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zan, D.; Chen, B.; Zhang, F.; Lu, D.; Wu, B.; Guan, B.; Yongji, W.; Lou, J.G. Large Language Models Meet NL2Code: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 7443–7464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Li, L.; Dai, D.; Zheng, C.; Ma, J.; Li, R.; Xia, H.; Xu, J.; Wu, Z.; Chang, B.; et al. A Survey on In-context Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 1107–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Scao, T.; Rush, A. How many data points is a prompt worth? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryzant, R.; Iter, D.; Li, J.; Lee, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M. Automatic Prompt Optimization with “Gradient Descent” and Beam Search. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 7957–7968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, G.; Kwak, D.; Dong Hyeon, J.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Seo, D.; et al. What Changes Can Large-scale Language Models Bring? Intensive Study on HyperCLOVA: Billions-scale Korean Generative Pretrained Transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 3405–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, L.; Lan, Y.; Xu, W.; Lim, E.P.; Bing, L.; Xu, X.; Poria, S.; Lee, R. LLM-Adapters: An Adapter Family for Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5254–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Li, J. Boundary Smoothing for Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 7096–7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margatina, K.; Vernikos, G.; Barrault, L.; Aletras, N. Active Learning by Acquiring Contrastive Examples. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Sap, M.; Lu, X.; Swayamdipta, S.; Bhagavatula, C.; Smith, N.A.; Choi, Y. DExperts: Decoding-Time Controlled Text Generation with Experts and Anti-Experts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 6691–6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).