Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

Study Objectives

Hypotheses

Primary Hypothesis

Secondary Hypothesis

Study Design and Ethical Approval

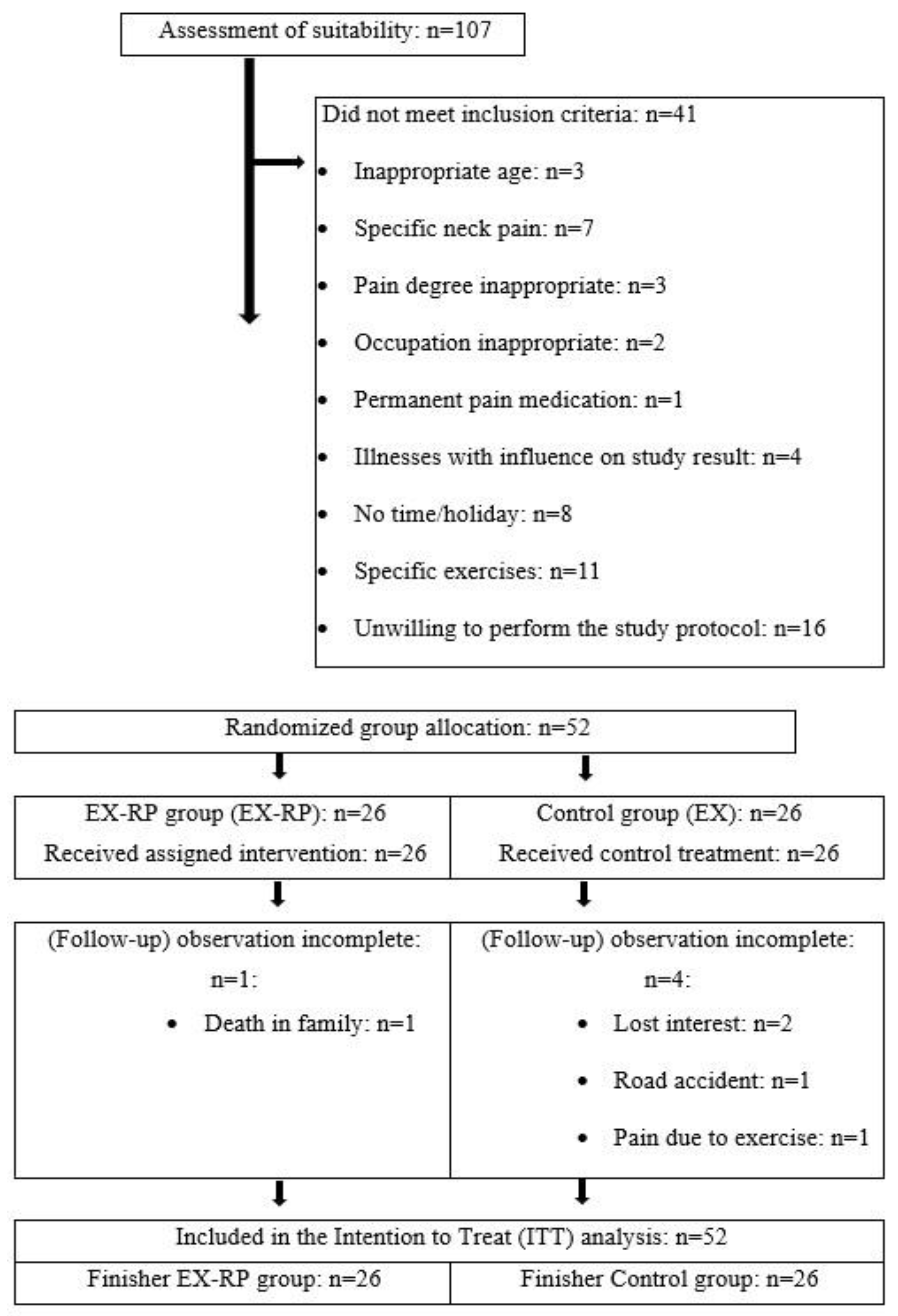

Study Population

Randomisation and Blinding

Interventions

Gymnastics Program (EX-RP and EX)

TMJ Relax Pads

Confounders: Medication Supply with Painkillers

Outcomes Measures and Assessment Schedule

Primary Study Endpoint

Secondary Study Endpoints

- Change in the Neck Disability Index (NDI) between basal assessment and control measurement after the 12-week intervention

- Change in mobility (lateral flexion, flexion, extension, rotation) of the cervical spine between basal assessment and control measurement after the 12-week intervention

- Change in mean trunk rotation between basal assessment and control measurement after the 12-week intervention

- Change in elevation ability of the shoulder joints (degree) between basal assessment and control measurement after the 12-week intervention

- Change in kyphosis angle between basal assessment and control measurement after the 12-week intervention

Neck Pain (NRS)

Limitations Due to Neck Complaints

Flexibility, Mobility and Posture

Kyphosis

Craniomandibular Dysfunction

Biometrics and Statistical Analysis

Results

Study Endpoints

Primary Study Endpoint: Intensity of Neck Pain

| EX-RP (n=26) MV ± SD |

EX (n=26) MV ± SD |

Difference MV (95% CI) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck pain intensity [Index] | ||||

| Basal value | 2.93± 1.72 | 2.66± 1.79 | ------------- | .661 |

| Change | -1.46± 1.90 | -0.45± 1.82 | 0.98 (0.02 to 1.95)* | .046* |

Secondary Study Endpoints

Adverse Effects

Potential Confounding Variables

Discussion

Clinical Relevance

- Combining TMJ relax pads with cervical exercises improved the functional outcomes in office workers with chronic non-specific neck pain.

- The combined intervention led to greater reductions in neck discomfort and disability than exercise alone

- It is non-evasive, easy to integrate into therapy sessions and requires no additional setup or expertise

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 2013 World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama 310, 2191-2194. [CrossRef]

- Ahlers MO, Jakstat HA 2008 Identifikation funktionsgestörter Patienten. Zahnmedizin up2date 2, 143-155. [CrossRef]

- Al-Moraissi, EA; Farea, R; Qasem, KA; Al-Wadeai, MS; Al-Sabahi, ME; Al-Iryani, GM. Effectiveness of occlusal splint therapy in the management of temporomandibular disorders: network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020, 49, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albagieh, H; Alomran, I; Binakresh, A; Alhatarisha, N; Almeteb, M; Khalaf, Y; Alqublan, A; Alqahatany, M. Occlusal splints-types and effectiveness in temporomandibular disorder management. The Saudi Dental Journal 2023, 35, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arent, S; McKenna, J; Golem, D. Effects of a neuromuscular dentistry-designed mouthguard on muscular endurance and anaerobic power. 2010, 7, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badel, T; Simonić-Kocijan, S; Lajnert, V; Dulčić, N; Zdravec, D. Michigan splint and treatment of temporomandibular joint. Medicina fluminensis 2013, 49, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Benli, M; Al-Haj Husain, N; Ozcan, M. Mechanical and chemical characterization of contemporary occlusal splint materials fabricated with different methods: a systematic review. Clinical Oral Investigations 2023, 27, 7115–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, L; Gardenghi, I; Turoni, F; Villafañe, JH; Capra, F; Guccione, AA; Pillastrini, P. Effect of Therapeutic Exercise on Pain and Disability in the Management of Chronic Nonspecific Neck Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Physical Therapy 2013, 93, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracco, P; Deregibus, A; Piscetta, R; Ferrario, G. Observations on the correlation between posture and jaw position: a pilot study. Cranio 1998, 16, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragatto, MM; Bevilaqua-Grossi, D; Regalo, SC; Sousa, JD; Chaves, TC. Associations among temporomandibular disorders, chronic neck pain and neck pain disability in computer office workers: a pilot study. J Oral Rehabil 2016, 43, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancaglini, R; Gherlone, EF; Radaelli, G. Association between loss of occlusal support and symptoms of functional disturbances of the masticatory system. J Oral Rehabil 1999, 26, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H; Lauche, R; Langhorst, J; Dobos, GJ; Michalsen, A. Validation of the German version of the Neck Disability Index (NDI). BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi Dds, I; Castroflorio Dds, PT; Cugliari Msc, G. Deregibus Md DDSPA 2020 Does occlusal splint affect posture? A randomized controlled trial. CRANIO® 38, 264–272.

- De Laat, A; Meuleman, H; Stevens, A; Verbeke, G. Correlation between cervical spine and temporomandibular disorders. Clin Oral Investig 1998, 2, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Zahn- M-uKD 2024 Okklusionsschienen zur Behandlung craniomandibulärer Dysfunktionen und zur präprothetischen Therapie; Berlin.

- Eberhard, D; Bantleon, HP; Steger, W. The efficacy of anterior repositioning splint therapy studied by magnetic resonance imaging. European Journal of Orthodontics 2002, 24, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, JP; Bandy, WD. Intrarater reliability of CROM measurement of cervical spine active range of motion in persons with and without neck pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008, 38, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulos, NN; Schindler, HJ; Hellmann, D. Co-contraction behaviour of masticatory and neck muscles during tooth grinding. J Oral Rehabil 2018, 45, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grondin, F; Hall, T; von Piekartz, H. Does altered mandibular position and dental occlusion influence upper cervical movement: A cross–sectional study in asymptomatic people. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 2017, 27, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y-n; Cui, S-j; Zhou, Y-h; Wang, X-d. An Overview of Anterior Repositioning Splint Therapy for Disc Displacement-related Temporomandibular Disorders. Current Medical Science 2021, 41, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampe, T; Fürstberger, L; Kordsmeyer, TL; Penke, L; Mahler, AM; Mäder, CM; Bürgers, R; Krohn, S. Impact of occlusal stabilization splints on global body posture: a prospective clinical trial. Clinical Oral Investigations 2024, 28, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannam, AG; Wood, WW; De Cou, RE; Scott, JD. The effects of working-side occlusal interferences on muscle activity and associated jaw movements in man. Archives of Oral Biology 1981, 26, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W; Schmutzer, G; Hinz, A; Hilbert, A; Brähler, E. Prevalence of chronic pain in Germany. A representative survey of the general population. Schmerz 2013, 27, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, J; Göttfert, F; Maurer-Grubinger, C; Holzgreve, F; Oremek, G; Groneberg, DA; Ohlendorf, D. Improvement of cervical spine mobility and stance stability by wearing a custom-made mandibular splint in male recreational athletes. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0278063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honaker, J; King, G; Blackwell, M. Amelia II: A Program for Missing Data. Journal of Statistical Software 2011, 45, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S; Chan, A-W; Collins, GS; Hróbjartsson, A; Moher, D; Schulz, KF; Tunn, R; Aggarwal, R; Berkwits, M; Berlin, JA; Bhandari, N; Butcher, NJ; Campbell, MK; Chidebe, RCW; Elbourne, D; Farmer, A; Fergusson, DA; Golub, RM; Goodman, SN; Hoffmann, TC; Ioannidis, JPA; Kahan, BC; Knowles, RL; Lamb, SE; Lewis, S; Loder, E; Offringa, M; Ravaud, P; Richards, DP; Rockhold, FW; Schriger, DL; Siegfried, NL; Staniszewska, S; Taylor, RS; Thabane, L; Torgerson, D; Vohra, S; White, IR. Boutron I 2025 CONSORT 2025 statement: updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. The Lancet 405, 1633–1640. [CrossRef]

- Höppchen, I; Wittek, M; Szecsenyi, J. Diagnostik bei Nackenschmerzen.

- Howell, E. The association between neck pain, the Neck Disability Index and cervical ranges of motion: a narrative review. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 2011, 55, 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, D; March, L; Woolf, A; Blyth, F; Brooks, P; Smith, E; Vos, T; Barendregt, J; Blore, J; Murray, C; Burstein, R; Buchbinder, R. The global burden of neck pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2014, 73, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz, EL; Randhawa, K; Yu, H; Côté, P; Haldeman, S. The Global Spine Care Initiative: a summary of the global burden of low back and neck pain studies. Eur Spine J 2018, 27, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incorvati, C; Romeo, A; Fabrizi, A; Defila, L; Vanti, C; Gatto, MRA; Marchetti, C; Pillastrini, P. Effectiveness of physical therapy in addition to occlusal splint in myogenic temporomandibular disorders: protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, V; Jull, G; Souvlis, T; Jimmieson, NL. Neck movement and muscle activity characteristics in female office workers with neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008, 33, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J-H. Effects on migraine, neck pain, and head and neck posture, of temporomandibular disorder treatment: Study of a retrospective cohort. Archives of Oral Biology 2020, 114, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karppinen, K; Eklund, S; Suoninen, E; Eskelin, M; Kirveskari, P. Adjustment of dental occlusion in treatment of chronic cervicobrachial pain and headache. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 1999, 26, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, MS; Kalekhan, SM; Mehta, R; Bhangdia, M; Rathore, K; Lalwani, V. Occlusal Splint Therapy in Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: An Update Review. Journal of International Oral Health 2016, 8, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, SY; Park, YJ; Park, HM; Bae, HJ; Yu, MJ; Choi, HW; Hwang, NY. Effect of the Mandibular Orthopedic Repositioning Appliance (MORA) on Forearm Muscle Activation and Grasping Power during Pinch and Hook Grip. J Phys Ther Sci 2014, 26, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippold, C; Danesh, G; Schilgen, M; Drerup, B; Hackenberg, L. Sagittal jaw position in relation to body posture in adult humans – a rasterstereographic study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2006, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, S; Makwela, S; Manas, L; Meyer, L; Terblanche, D; Brink, Y. Effectiveness of exercise in office workers with neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. S Afr J Physiother 2017, 73, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermid, JC; Walton, DM; Avery, S; Blanchard, A; Etruw, E; McAlpine, C; Goldsmith, CH. Measurement properties of the neck disability index: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009, 39, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- März, K; Adler, W; Matta, R-E; Wolf, L; Wichmann, M; Bergauer, B. Can different occlusal positions instantaneously impact spine and body posture? Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics/Fortschritte der Kieferorthopadie 2017, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, C; Heller, S; Sure, JJ; Fuchs, D; Mickel, C; Wanke, EM; Groneberg, DA; Ohlendorf, D. Strength improvements through occlusal splints? The effects of different lower jaw positions on maximal isometric force production and performance in different jumping types. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0193540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, C; Stief, F; Jonas, A; Kovac, A; Groneberg, DA; Meurer, A; Ohlendorf, D. Influence of the Lower Jaw Position on the Running Pattern. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0135712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer-Grubinger, C; Avaniadi, I; Adjami, F; Christian, W; Doerry, C; Fay, V; Fisch, V; Gerez, A; Goecke, J; Kaya, U; Keller, J; Krüger, D; Pflaum, J; Porsch, L; Wischnewski, C; Scharnweber, B; Sosnov, P; Oremek, G; Groneberg, DA; Ohlendorf, D. Systematic changes of the static upper body posture with a symmetric occlusion condition. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2020, 21, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostazir, M; Taylor, G; Henley, WE; Watkins, ER; Taylor, RS. Per-Protocol analyses produced larger treatment effect sizes than intention to treat: a meta-epidemiological study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2021, 138, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odzimek, M; Brola, W. Occurrence of Cervical Spine Pain and Its Intensity in Young People with Temporomandibular Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlen, G; Aaro, S; Bylund, P. The sagittal configuration and mobility of the spine in idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988, 13, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlendorf, D; Seebach, K; Hoerzer, S; Nigg, S; Kopp, S. The effects of a temporarily manipulated dental occlusion on the position of the spine: a comparison during standing and walking. The Spine Journal 2014, 14, 2384–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivo, SA; Fuentes, J; Major, PW; Warren, S; Thie, NM; Magee, DJ. The association between neck disability and jaw disability. J Oral Rehabil 2010, 37, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, DL; Rothstein, JM; Lamb, RL. Goniometric reliability in a clinical setting. Shoulder measurements. Phys Ther 1987, 67, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabari, JS; Maltzev, I; Lubarsky, D; Liszkay, E; Homel, P. Goniometric assessment of shoulder range of motion: comparison of testing in supine and sitting positions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998, 79, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, K; Mehta, NR; Abdallah, EF; Forgione, AG; Hirayama, H; Kawasaki, T; Yokoyama, A. Examination of the Relationship Between Mandibular Position and Body Posture. CRANIO® 2007, 25, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, YJ; Kim, WH; Kim, SG. Correlations among visual analogue scale, neck disability index, shoulder joint range of motion, and muscle strength in young women with forward head posture. J Exerc Rehabil 2017, 13, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shousha, TM; Soliman, ES; Behiry, MA. The effect of a short term conservative physiotherapy versus occlusive splinting on pain and range of motion in cases of myogenic temporomandibular joint dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. J Phys Ther Sci 2018, 30, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofyanti, E; Boel, T; Sihombing, ARN. The correlation between back posture and sagittal jaw position in adult orthodontic patients. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 2021, 16, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, R; Jyoti, B; Devi, P. Oral splint for temporomandibular joint disorders with revolutionary fluid system. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2013, 10, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Stapelmann, H; Türp, JC. The NTI-tss device for the therapy of bruxism, temporomandibular disorders, and headache – Where do we stand? A qualitative systematic review of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereshchuk. EFFECT OF USING A RELAXATION SPLINT ON REDUCING CHRONIC NECK PAIN. Ukrainian Dental Almanac 2024, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouli, MN; Vernon, HT; Kakavelakis, KN; Antonopoulou, MD; Paganas, AN; Lionis, CD. Translation of the Neck Disability Index and validation of the Greek version in a sample of neck pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, H; Mior, S. The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1991, 14, 409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Walczyńska-Dragon, K; Baron, S. The biomechanical and functional relationship between temporomandibular dysfunction and cervical spine pain. Acta Bioeng Biomech 2011, 13, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walczyńska-Dragon, K; Baron, S; Nitecka-Buchta, A; Tkacz, E. 2014 Correlation between TMD and Cervical Spine Pain and Mobility: Is the Whole Body Balance TMJ Related? BioMed Research International 2014, 582414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassell, RW; Adams, N; Kelly, PJ. The treatment of temporomandibular disorders with stabilizing splints in general dental practice: one-year follow-up. J Am Dent Assoc 2006, 137, 1089-1098; quiz 1168-1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, P; Corrêa, EC; Ferreira Fdos, S; Soares, JC; Bolzan Gde, P; Silva, AM. Cervical spine dysfunction signs and symptoms in individuals with temporomandibular disorder. J Soc Bras Fonoaudiol 2012, 24, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S-H; He, K-X; Lin, C-J; Liu, X-D; Wu, L; Chen, J; Rausch-Fan, X. Efficacy of occlusal splints in the treatment of temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2020, 78, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | EX-RP (n=26) MW ± SD |

EX (n=26) MW ± SD |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female/male/diverse [n] | 20/6/0 | 19/7/0 | .749 |

| Age [years] | 48.5 ± 9.3 | 47.3 ± 9.3 | .922 |

| Height [cm] | 169 ± 9 | 171 ± 7 | .306 |

| Body mass [kg] | 70.5 ± 11.9 | 71.0 ± 13.2 | .553 |

| Craniomandibular dysfunction (CMD) [n] | 16 | 15 | .777 |

| Pain medication [n]a | 4 | 3 | .692 |

| Osteoporosis medication [n] | 19 | 17 | .653 |

| Physical training [min/week] | 45.5 ± 38.5 | 56.5 ± 50.0 | .271 |

| Physical activity [Index] | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | .783 |

| Prevalence of CMD | 16/10 | 15/11 | .783 |

| EX-RP (n=26) MV± SD |

EX (n=26) MV± SD |

Difference MV (95% CI) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck Disability Index (NDI) [%] | ||||

| Basal | 36.7± 6.7 | 37.8± 8.5 | ------------- | .611 |

| Change | -6.6± 8.0 | -8.2± 8.8 | 1.44 (-2.9 to 5.8)* | .514* |

| Lateral flexion cervical spine [°] | ||||

| Basal | 34.9± 7.2 | 37.8± 8.3 | ------------- | .188 |

| Change | 5.9± 6.6 | 4.6± 7.0 | 0.38 (-3.1 to 3.9)* | .825* |

| Flexion cervical spine [°] | ||||

| Basal | 50.5± 13.6 | 49.5± 11.1 | ------------- | .773 |

| Change | 6.6± 9.8 | 5.4± 10.2 | 1.35 (-4.1 to 6.9)* | .581* |

| Extension cervical spine [°] | ||||

| Basal | 75.7± 14.9 | 74.9± 17.2 | ------------- | .871 |

| Change | 7.4± 10.9 | 2.2± 11.4 | 5.48 (0.2 to 10.8)* | .044* |

| Mean rotation cervical spine [°] | ||||

| Basal | 71.1± 10.6 | 73.4± 12.2 | ------------- | .468 |

| Change | 6.3± 8.1 | 3.9± 8.5 | 1.69 (-2.4 to 5.8)* | .405* |

| Average torso rotation [°] | ||||

| Basal | 50.1± 9.2 | 51.8± 11.3 | ------------- | .534 |

| Change | 5.9± 10.9 | 13.1± 10.1 | 6.62 (1.1 to 12.1)* | .019* |

| Elevation shoulder [°] | ||||

| Basal | 165.5± 15.6 | 160.2± 13.7 | ------------- | .192 |

| Change | 10.6± 10.5 | 12.1± 11.2 | 1.09 (-4.0 to 6.1)* | .667* |

| Kyphosis angle [°] | ||||

| Basal | 42.2± 8.2 | 41.3± 8.8 | ------------- | .710 |

| Change | -3.6± 6.9 | -2.5± 7.2 | 0.85 (-4.4 to 2.7)* | .634* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).