1. Introduction

The proliferation of Instant Messaging (IM) platforms like Telegram has reshaped social interaction, but it has also enabled new forms of deceptive linguistic behavior. On these platforms,

spam is not merely an unsolicited advertisement; it is a form of malicious communication that employs sophisticated persuasive strategies to deliver phishing campaigns, malware, and fraudulent schemes [

1,

2]. The real-time, large-scale nature of IM, combined with automated bots, allows this deceptive content to achieve viral dissemination at a speed that traditional, human-led moderation cannot effectively counter [

3]. In this paper, we treat Telegram spam as an observable form of deceptive messaging in an instant-messaging governance context.

Telegram, in particular, presents a unique social and linguistic environment for studying this behavior. Its messages are typically short, informal, and privacy-centric, often lacking the rich metadata that conventional filters exploit. Consequently, analyzing the text itself becomes both a methodological constraint and a practical necessity for understanding the strategies spammers use. This context demands a deeper, computational analysis of the linguistic patterns that define this deceptive behavior.

1.1. Modeling the Complexity of Deceptive Behavior

To understand these deceptive strategies, computational research has developed models of increasing complexity. These models can be viewed not just as ‘defenses’, but as analytical lenses that reveal the structure of the behavior itself.

The foundational approach has been rooted in feature engineering, where raw text is converted into numerical formats like Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF–IDF) [

4]. This lens assumes that deceptive behavior is characterized by explicit lexical features—specific, high-value keywords (e.g., ‘free’, ‘profit’, ‘click’). This approach enables interpretable, classical algorithms like Logistic Regression and ensemble methods like LightGBM to classify messages [

5,

6,

7]. However, this lens is inherently constrained; it often fails to capture more nuanced, context-dependent language used in evasive spam [

1].

This limitation prompted a shift toward representation learning. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) such as Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) [

8] provide a sequential lens, capable of modeling

patterns and temporal dependencies in text. The current state-of-the-art is defined by transformer architectures like ALBERT [

9], which employ self-attention to model contextual relationships. This context-aware lens can, in theory, capture complex semantic strategies where the deceptive meaning is not in any single word but in the subtle relationship

between words.

A growing body of work has applied modern NLP to spam, phishing, and fraud detection across communication channels, including transformer-based classifiers and embedding-driven pipelines for short, noisy text. Prior studies generally emphasize predictive gains from contextual representations, the role of adversarial obfuscation and evolving tactics, and the challenges of deployment and interpretability in moderation settings. Building on this literature, our focus is not to introduce yet another BERT-based detector, but to use a hierarchy of model families as an analytical lens to characterize deceptive strategies and to connect statistically validated performance gaps with interpretable and qualitative evidence of distinct linguistic ‘tiers’.

Despite these advancements, it is unclear what level of linguistic complexity modern spammer behavior exhibits. Is it still a simple, keyword-based problem, or has it appears to include a complex, semantic one? Prior research has focused on email and social media spam, but little work has used this hierarchy of computational models to analytically probe the structure of deceptive behavior specifically within the unique context of Telegram.

1.2. Challenges in Modeling Evasive Linguistic Behavior

Analyzing any form of deceptive communication computationally faces several enduring obstacles, which are themselves rooted in behavioral adaptation and social context:

Adversarial Obfuscation: Perpetrators (spammers) intentionally adapt their linguistic patterns, using misspellings or symbolic substitutions to evade detection [

1].

Skewed Class Distribution: Deceptive behavior is a deviant minority case. The overwhelming dominance of legitimate (‘ham’) messages degrades model sensitivity to these crucial minority spam cases [

10,

11].

Platform Specificity: Deceptive strategies are not universal; they are shaped by the social context and norms of the platform, limiting cross-domain generalization [

11].

Concept Drift: The strategies themselves evolve. This ‘concept drift’ causes models trained on historical behavior to degrade over time [

1].

Short and Noisy Text: The linguistic environment of IM is brief and informal, creating data sparsity and noise that can hinder reliable analysis [

12].

Model Opacity: The most powerful, context-aware ‘lenses’ (transformers) are often ‘black boxes’, complicating the

interpretation of the very patterns they detect [

13].

1.3. Research Objectives and Core Contributions

Motivated by these challenges, this study moves beyond a simple performance benchmark to computationally analyze the structure of deceptive linguistic behavior on Telegram. We use the performance differences between models of varying complexity as a diagnostic tool. Our central research question is: What level of linguistic complexity is required to model spammer behavior, and what does this reveal about the strategies spammers employ?

From a computational social science perspective, deceptive messaging can be understood as strategic persuasive communication under adversarial constraints: as platforms deploy automated filters and governance rules, spammers may adapt by shifting from overt keyword-based appeals toward more indirect, conversational, or context-dependent framing that reduces detectability while preserving persuasive force. This motivates viewing model families not only as engineering choices but as distinct analytical lenses on behavior, and it foregrounds moderation as a sociotechnical process involving automation, triage, and human oversight rather than a standalone classifier.

We evaluate a hierarchy of models on a real-world dataset of 20,348 Telegram messages [

14], from lexical (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, LightGBM) to sequential (GRU) and context-aware (ALBERT) architectures. We implement a harmonized validation pipeline with statistical verification via McNemar’s test to ensure our comparisons are robust.

The core objectives of this research are threefold:

To test the hypothesis of a two-tier structure in spammer behavior: a ‘simple’ tier based on explicit keywords and a ‘complex’ tier based on subtle semantic and contextual cues.

To quantify the performance differences between lexical and context-aware models to determine the limits of simpler analytical approaches and test the necessity of more complex, semantic-aware models for this task.

To conduct an interpretive linguistic analysis of classical models to identify the specific textual and behavioral cues characterizing explicit spam strategies, which serves as a baseline for understanding the behavior captured by more complex models.

While transformer-based models have been widely applied to spam and phishing detection, the novelty of our work is not simply reporting higher accuracy. Rather, we use a hierarchy of model architectures as an analytical framework to characterize deceptive strategies, pairing statistical model comparisons with interpretability and error analysis to motivate a two-tier account of deception and to derive governance-relevant implications for moderation pipelines.

By releasing the full experimental pipeline and codebase, this study provides a reproducible framework for the computational analysis of deceptive text. The results aim to inform the social-scientific understanding of spammer behavior and guide the practical development of moderation systems that can account for these evolving, multi-layered linguistic strategies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the dataset, preprocessing pipelines, model architectures, and evaluation framework.

Section 3 presents the quantitative results, statistical comparisons, and interpretability analyses.

Section 4 discusses the behavioral implications, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Methods

To establish a rigorous computational analysis of deceptive linguistic behavior, this section details our complete experimental design. The foundation of the methodology is the dataset and its preparation. We then introduce our hierarchy of analytical models, which involved two tailored preprocessing workflows—one for lexical models (classical machine learning) and another for context-aware models (deep learning architectures). We specify the architectural details for each model, framing them as operationalizations of different levels of linguistic complexity. The framework concludes with a definition of the quantitative performance metrics and the statistical validation methods used to compare the explanatory power of these different models. The objective of this structured methodology is to ensure that our final analysis of spammer behavior is transparent, reproducible, and empirically sound.

Additions for applied rigor. Beyond model performance, we also document probability calibration, operating-threshold selection, deployment-oriented efficiency metrics (latency, memory, and model size), and full reproducibility practices. These additions do not alter any core procedures; they clarify how the models behave in real-world settings and how our results can be exactly replicated.

2.1. Data and Preprocessing

Our empirical analysis is grounded in the

‘Telegram Spam or Ham’ corpus, an open-source dataset available on Kaggle that is tailored for the binary classification of short-form text messages [

14]. Following the removal of invalid entries, our working dataset comprised 20,348 English messages. Each message is labeled as either legitimate (‘ham’) or spam, with a significant class disparity of 14,337 to 6,011, respectively.

The public release provides the binary labels but does not document the labeling protocol (e.g., whether labels were user-reported, manually annotated, or heuristically assigned), nor does it include timestamps or an explicit collection date range. The skewed distribution is a key feature of the social phenomenon being studied (i.e., deceptive behavior is a minority event), and it was a primary consideration in the design of our evaluation protocol.

To ensure a fair and rigorous comparison between model architectures, and to eliminate potential confounding variables arising from disparate feature engineering, we implemented a harmonized preprocessing pipeline for all models prior to vectorization. This pipeline involved converting all text to lowercase, and systematically replacing elements like URLs, user mentions, and hashtags with unique tokens (e.g., <URL>, <USER>, <HASHTAG>). Stopwords were deliberately retained, while emojis were removed during normalization. This unified approach allows for a more direct assessment of each model’s ability to learn from text.

Following this harmonized preprocessing, the data was then vectorized according to the specific requirements of each model family. For the lexical models (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and LightGBM), the preprocessed text was transformed into a numerical matrix using the Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) weighting scheme. The TF-IDF value for a given term

t within a document

d is calculated as:

where tf(t,d) represents the term (i.e., t) frequency in a document (i.e., d), N is the total number of documents, and df(t) is the document frequency of the term. To prevent information leakage, the TF-IDF vocabulary and document frequencies were learned exclusively from the training partition before being applied to transform the validation and test sets [

4]. For the sequential and context-aware models (GRU and ALBERT), the same preprocessed text was fed into model-specific subword tokenizers.

To ensure a robust and unbiased evaluation of model generalization, the complete dataset was partitioned into three distinct subsets: 60% for training, 20% for hyperparameter validation, and a final 20% held out for testing. All partitioning was performed using a fixed random seed to guarantee the full reproducibility of our experimental results.

Additional implementation clarifications. Splits were stratified to preserve class proportions across train/validation/test. For deep models, we evaluated maximum sequence lengths with truncation/padding and attention masks, selecting the operating point on validation performance to balance accuracy and latency.

2.2. Modeling Explicit Linguistic Features: Classical Approaches

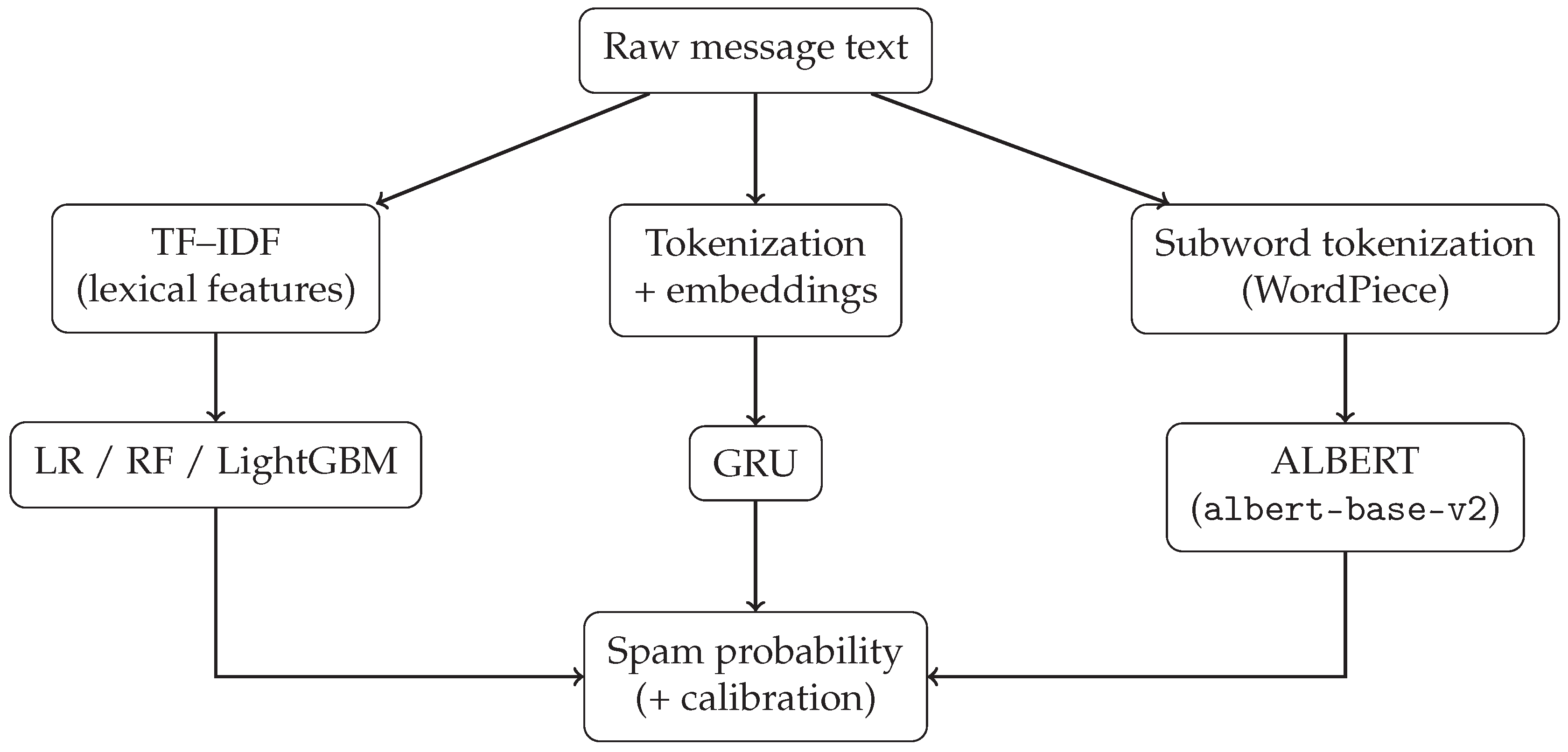

To establish an interpretable baseline for what constitutes simple, keyword-driven spam behavior, our investigation includes a set of classical supervised learning algorithms. These models operate on TF-IDF feature representations and range from a transparent linear model to powerful non-linear ensembles. They serve as our analytical lens for explicit linguistic strategies, allowing for a thorough examination of the trade-offs between model complexity and predictive power. A schematic overview of the full modeling pipeline and the inputs to each model family is shown in

Figure 1.

2.2.1. Linear Classifier: Logistic Regression

As a fundamental interpretable model, we employed Logistic Regression [

5]. This probabilistic model is commonly used in text classification and serves as a highly transparent baseline. Each Telegram message, represented by its TF–IDF feature vector

, is assigned a probability of being spam (

) via the logistic (sigmoid) transformation:

Here,

and

b denote the learned coefficient vector and bias term. These parameters are estimated by minimizing the

-regularized binary cross-entropy loss:

where

and

represent the true and predicted spam labels, respectively, and

controls the degree of

regularization. The penalty term discourages large coefficients, thereby reducing overfitting in the high-dimensional TF–IDF representation of Telegram messages and promoting a simpler, more generalizable model.

We optimized the model’s hyperparameters through a comprehensive grid search, selecting configurations based on the weighted F1-score computed on the validation set. The evaluated parameter grid was defined as follows:

Inverse regularization strength: , where .

Solver: , allowing comparison between a coordinate descent algorithm tailored for sparse inputs and a quasi-Newton optimizer known for rapid convergence.

Class weighting: , optionally compensating for class imbalance by weighting classes inversely to their frequencies.

This systematic tuning procedure was used to inform the selection of the final hyperparameters. Owing to its linearity and interpretability, Logistic Regression serves as a transparent lens for identifying the core lexical features associated with spam and ham.

Calibration and thresholding. For deployment-oriented interpretability, we assessed LR probability calibration via isotonic regression and Platt scaling on the validation split and applied the learned mapping to the test split. In addition to the default 0.5 threshold, we reported performance at the validation-optimal F1 threshold.

2.2.2. Nonlinear Classifier: Tree-based Models

Decision trees provide an interpretable, non-parametric approach to supervised learning by recursively partitioning the input space into axis-aligned regions. In the context of

analyzing spam behavior, the tree model learns hierarchical decision boundaries over TF–IDF-based textual features to classify messages [

15]. This structure enables transparent rule-based reasoning, making decision trees particularly appealing for

exploratory analysis of communication patterns.

At each internal node, the algorithm selects a feature

j and threshold

t that best divides the dataset

into left and right subsets, thereby maximizing the purity of each resulting child node. A primary method for evaluating the quality of a split is to measure the reduction in uncertainty using Information Gain, which is calculated based on

Shannon entropy. For a node containing samples distributed across

C classes, the entropy is defined as:

where

is the proportion of samples belonging to class

c. The algorithm seeks the feature and threshold that maximize the Information Gain, which represents the total reduction in entropy from the parent node to its children.

An alternative and computationally efficient impurity measure is the

Gini index. The Gini impurity for the same node is defined as:

For a binary classification task (

), this simplifies to

, where

p is the fraction of samples from one class. When using this criterion, the split that achieves the greatest reduction in Gini impurity is chosen. In either approach, the fundamental goal is to select the split that produces the most homogeneous child nodes possible.

The recursive partitioning continues until a termination condition is satisfied, such as:

A minimum number of samples per split,

A maximum allowed tree depth,

All samples within a node belonging to a single class.

While decision trees can capture nonlinear feature interactions, their expressiveness often results in overfitting—particularly in sparse, high-dimensional domains like message-level text classification. This overfitting tendency manifests when the tree memorizes specific word patterns in the training data rather than learning generalizable linguistic features [

16,

17]. Nonetheless, their interpretability and transparent structure make them valuable as analytical baselines for understanding feature importance and hierarchical decision logic.

In the current project, we constructed single decision trees as interpretable mathematical baselines to explore hierarchical feature interactions in Telegram messages. However, given their known susceptibility to overfitting, especially under sparse TF–IDF representations, we focused subsequent analysis on ensemble methods—namely Random Forest and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM)—which incorporate mechanisms to enhance stability and generalization.

2.2.3. Random Forest

The

Random Forest algorithm extends the decision tree paradigm by aggregating multiple randomized trees to reduce variance and improve robustness [

6]. Each tree is trained on a bootstrapped subset of the training data, and at each node, a random subset of features is considered for splitting. This randomization ensures diversity among trees, leading to better generalization.

For a binary classification problem, the ensemble prediction is determined via majority voting across all

T trees:

where

denotes the class prediction from the

t-th tree.

We performed a grid search on the validation set, using the weighted F1-score as the selection criterion. The explored hyperparameters included:

n_estimators: Number of trees in the ensemble,

max_depth: Maximum tree depth,

min_samples_split: Minimum samples required to split a node,

min_samples_leaf: Minimum samples required at a leaf node,

class_weight: Adjusts for class imbalance between spam and non-spam messages.

Feature importance was computed by averaging impurity reductions across all trees, providing interpretable insights into which tokens or n-grams most influenced the model’s classification of spam. Although this ensemble sacrifices some transparency compared to a single decision tree, it achieves notably higher predictive stability and accuracy.

Calibration and operating points. We evaluated RF outputs with Platt scaling on validation data, reported Brier scores, and compared test performance at threshold and the validation-F1-optimal threshold to reflect realistic operating points.

2.2.4. Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM)

The

Light GradientBoosting Machine (LightGBM) is a gradient boosting framework that sequentially builds an ensemble of decision trees to minimize a differentiable loss function [

7,

18]. Unlike parallel ensembles like Random Forest, the model is constructed in a stage-wise manner. At each iteration

m, the model is additively updated:

where

is a new decision tree trained to correct the errors of the preceding model

, and

is a learning rate.

To determine the optimal structure of each new tree, LightGBM uses a highly efficient, gradient-based optimization. It approximates the loss function using a second-order Taylor expansion, which leverages both the first derivative (gradient, g) and the second derivative (Hessian, h) of the loss with respect to the current predictions. This provides more accurate information about the loss function’s shape and allows for more effective updates.

This second-order approximation results in a quantifiable objective for evaluating each potential split, known as the split gain. For a proposed split that partitions data into left (

L) and right (

R) subsets, the gain is computed as:

where

and

are the sums of the first and second derivatives in the left subset, respectively,

is an

regularization term, and

is a penalty for adding a new leaf. The algorithm selects the split that maximizes this gain.

Compared to traditional GBMs, LightGBM integrates two key innovations for efficiency. First, it employs a leaf-wise growth strategy, splitting the leaf that yields the greatest loss reduction rather than growing the tree level-by-level. Second, it uses a histogram-based algorithm to bin continuous features into discrete intervals, which dramatically speeds up the process of finding the optimal split. These design principles make LightGBM a powerful and scalable model for capturing complex, non-linear interactions between explicit lexical features.

Calibration and imbalance sensitivity. We report LightGBM probability calibration with isotonic regression and compare results with and without scale_pos_weight to verify stability under class imbalance remedies.

2.3. Modeling Sequential and Context-Aware Behavior: Deep Learning Models

While linear and tree-based algorithms provide an interpretable lens for explicit, lexical behaviors, they often struggle to capture the intricate semantics and contextual dependencies present in conversational text. Deceptive communication may not be explicit, but rather embedded in subtle phrasing or sequence. To model these more complex, implicit strategies, we explored deep learning architectures capable of representing both the semantic coherence and sequential dynamics of text.

We implemented two complementary neural paradigms:

Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) and

A Lite Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (ALBERT). Although newer compact transformers and LLM embedding pipelines are increasingly common, we select ALBERT here as a well-established, parameter-efficient transformer baseline that provides strong contextual representations under practical memory/compute constraints in cost-sensitive moderation settings. The GRU serves as our sequential lens, capturing temporal dependencies and recurrent patterns. ALBERT serves as our context-aware lens, modeling nuanced semantic relationships across the entire message. Both models are mathematically formalized below.

Figure 1 summarizes how each model family consumes the preprocessed text, from TF–IDF lexical features (classical models) to token embeddings (GRU) and subword tokenization (ALBERT).

2.3.1. A Lite Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (ALBERT)

Transformer-based models have redefined natural language understanding by modeling token-level relationships using self-attention rather than recurrence. The Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) framework [

19] introduced a deeply layered encoder architecture, where each layer integrates information from all other tokens in the sequence, allowing bidirectional context learning. This context-aware analytical capability is particularly advantageous for detecting deceptive linguistic strategies where short messages rely on subtle contextual or syntactic signals distributed across few tokens.

Formally, given an input token sequence

, the transformer encoder updates token representations through stacked attention and feedforward operations:

where MultiHeadAttn computes contextual dependencies through scaled dot-product attention, FFN applies nonlinear transformation, and LayerNorm stabilizes learning.

Although BERT achieves strong contextual representations, its extensive parameterization increases computational demand. ALBERT (A Lite BERT) [

9] introduces architectural optimizations that preserve BERT’s performance while reducing model size. The two core innovations are:

Factorized Embedding Parameterization: ALBERT decomposes the embedding matrix as , where and for vocabulary size V, bottleneck size k, and hidden dimension d, satisfying . This factorization decouples the lexical and hidden dimensions, minimizing memory cost without sacrificing representational depth.

Cross-layer Parameter Sharing: The encoder parameters

are shared across all

L layers:

which reduces the total parameter count and enhances regularization across layers.

Additionally, ALBERT introduces Sentence Order Prediction (SOP) as an auxiliary pretraining task, improving its ability to capture message coherence and conversational continuity—useful for identifying contextually misplaced spam messages in group threads.

For this study, we fine-tuned the pretrained albert-base-v2 model for binary classification. Each message was tokenized, truncated or padded to a fixed maximum length, and fed into the model. The [CLS] token’s output embedding was passed through a dense layer followed by a softmax classifier to predict spam probability.

Hyperparameters were optimized through randomized search over the following domains:

Learning rate : log-uniformly sampled from ,

Number of epochs: integers in ,

Dropout rate: uniformly sampled from .

Ten configurations were evaluated, and the best-performing model—measured by validation weighted F1-score—was selected. Through its parameter-efficient design and bidirectional attention, ALBERT provides a powerful lens for identifying subtle spam semantics even within short and noisy text.

Training protocol and calibration. We used Adam optimization with cosine or step learning-rate scheduling and early stopping based on validation weighted F1; the best checkpoint was retained for testing. For deployment-grade probabilities, we applied temperature scaling on the validation split and evaluated Brier score and reliability curves on test predictions.

2.3.2. Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) serve as a foundation for modeling sequential phenomena in NLP. In our setting, we model each message independently and treat the

sequence dimension as the ordered token sequence

within a single message (intra-message), rather than inter-message dynamics across conversation threads or user timelines. Standard RNNs, however, are prone to vanishing gradients and thus fail to capture long-range dependencies

within sequences. Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) [

8] mitigate this limitation by introducing gating mechanisms that dynamically control memory flow through the token sequence.

For an input sequence , the GRU maintains a hidden state updated as:

Update Gate (): Determines how much of the past information from the previous hidden state is passed along to the future.

Reset Gate (): Decides how much of the past information to forget when computing the new candidate state.

Candidate Hidden State (): Computes a new memory content based on the current input and a reset version of the previous hidden state.

Final Hidden State (): Linearly interpolates between the previous hidden state

and the candidate state

, using the update gate as the coefficient.

where denotes the sigmoid activation, ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication, and , , are learnable parameters. The update gate determines how much prior context is preserved, while the reset gate controls the degree of historical forgetting.

For this analysis, each message was tokenized and transformed into an embedding sequence before being processed by one or more GRU layers. The model architecture included:

- 1.

An embedding layer converting tokens into dense vectors;

- 2.

One or more GRU layers capturing token-order (intra-message) dependencies and compositional patterns;

- 3.

A fully connected output layer using the final hidden state to classify spam vs. non-spam messages.

Dropout regularization was applied to prevent overfitting to idiosyncratic spam examples.

Hyperparameters were sampled via randomized search across 10 trials within the following ranges:

Embedding dimension: integers in ,

Hidden dimension: integers in ,

Learning rate : log-uniformly sampled from ,

Number of epochs: integers in .

This randomized search was used to inform the selection of the final hyperparameters.

GRUs are therefore well-suited for capturing compositional and order-dependent cues within short messages (e.g., phrasal patterns and local context), but modeling cross-message trajectories or conversation-level dynamics is out of scope for this study.

Training protocol and calibration. We trained with Adam, applied early stopping based on validation weighted F1, and selected the best checkpoint for testing. For calibrated probabilities, we applied temperature scaling on the validation split and reported Brier score and reliability characteristics on test predictions.

In summary, ALBERT and GRU provide complementary analytical lenses for Telegram spam analysis. ALBERT’s transformer-based architecture captures semantic and contextual relationships within messages, while GRU provides a sequential lens by modeling token-order dependencies within individual messages.

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

To rigorously evaluate how effectively each model captures the target phenomenon (spam behavior), we employed several standard binary classification metrics. These metrics provide a quantitative measure of model fit. Let

denote the ground-truth label and

the predicted label for message

i, where 1 corresponds to a spam message and 0 to a legitimate (ham) message.

Here,

(true positives) represents spam messages correctly identified as spam, while

(false positives) counts legitimate messages incorrectly flagged as spam. In the social context of Telegram, high precision is essential for minimizing false alarms and avoiding disruptions to normal communication.

(false negatives) are spam messages mistakenly labeled as legitimate. High recall indicates the model successfully identifies the full range of deceptive behavior, an especially important property as spam often appears in bursts.

The F1-score represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure of the model’s overall reliability. A high F1-score indicates robust generalization in capturing the variability of real-world spam.

Because the dataset exhibits a class imbalance reflective of the real-world phenomenon (spam is a minority behavior), we adopted macro-averaged and weighted variants of these metrics. Macro-averaging ensures equal treatment of both the minority (spam) and majority (ham) classes. Weighted averaging reflects the dataset’s true composition.

To further assess classification quality across varying thresholds, we plotted the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, which visualizes the relationship between true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR):

The Area Under the Curve (AUC) quantifies the likelihood that the model ranks a randomly selected spam message higher than a legitimate one, reflecting consistent discriminative power.

Thresholds, PR curves, and calibration. In addition to a fixed threshold of

, we report results at the validation-F1-optimal threshold. Given class imbalance, we complement ROC with precision–recall (PR) curves and Average Precision (AP). Finally, we quantify probability quality using the Brier score:

and visualize calibration via reliability curves.

Across all experiments, the weighted F1-score on the validation set served as the principal metric for hyperparameter tuning and model selection. This ensured that our analytical models were optimized for both sensitivity and reliability under class imbalance. Final performance was reported on a held-out test set for fair model comparison.

2.5. Statistical Comparison of Analytical Models: McNemar’s Test

To determine whether observed performance differences between our different analytical models were statistically meaningful, we employed McNemar’s test [

20]. This non-parametric test is designed to evaluate two models on the same set of samples and specifically assesses whether their error patterns differ significantly.

In this context, the comparison identifies whether a more complex lens (e.g., ALBERT) is capturing a systematically different part of the phenomenon than a simpler lens (e.g., LightGBM). For example, one model may excel at detecting link-heavy spam, while another might misclassify conversational promotional content. McNemar’s test quantifies such discrepancies.

Formally, let models A and B produce binary predictions on the same evaluation set. Define:

— number of messages misclassified by A but correctly classified by B,

— number of messages correctly classified by A but misclassified by B.

The McNemar test statistic is computed as:

Under the null hypothesis—stating that both models have equivalent error rates—this statistic asymptotically follows a chi-squared distribution with one degree of freedom.

Intuitively, when and differ substantially, it suggests that one model’s lens is consistently more effective on specific types of Telegram messages. By focusing on paired disagreements rather than overall accuracy, McNemar’s test provides a sensitive diagnostic for comparing the error structures of the models.

Since our evaluation involved multiple pairwise comparisons, p-values were adjusted using Holm’s sequential correction method. This adjustment controls the family-wise error rate, reducing the likelihood of falsely declaring significance due to multiple testing.

Together, this statistical framework enables a principled determination of whether any observed superiority of one analytical framework over another reflects a genuine improvement in its ability to model the target behavior.

reproducibility notes. Reproducibility is ensured via fixed random seeds for splitting and training, stratified sampling, and learning TF–IDF statistics and tokenizers strictly on the training split. Implementations use scikit-learn, LightGBM, and standard Transformer/RNN libraries; we release preprocessing scripts, configuration files, exact hyperparameters, trained checkpoints, and instructions to regenerate all tables and figures end-to-end. Deployment-related efficiency considerations are discussed qualitatively rather than through controlled runtime benchmarks.

3. Results

This section presents the empirical findings from our computational analysis of deceptive behavior on Telegram. We begin by detailing the hyperparameter optimization used to ensure each analytical model was properly calibrated. We then report the predictive outcomes of all five models, using the performance gaps between them to quantify the linguistic complexity of spammer strategies. We highlight the comparative performance on both the majority (ham) and, critically, the minority (spam) classes. Next, we conduct formal statistical tests to verify that the observed performance differences are significant, providing a rigorous foundation for our behavioral interpretation. Finally, we use the interpretable classical models to conduct a linguistic feature analysis, identifying the specific behavioral markers that define the ‘simple’ tier of spam.

3.1. Hyperparameter Selection

To ensure a fair and robust comparison, a systematic hyperparameter optimization process was conducted for each model. This step is critical for eliciting the maximum explanatory power from each algorithm. By fitting each model’s complexity to the dataset, we minimize bias and variance, ensuring that any observed performance gaps are attributable to the fundamental differences in model architecture (i.e., the complexity of the ‘lens’) rather than suboptimal tuning. The primary objective function for this optimization was the weighted F1-score, evaluated on the held-out validation set. This metric was chosen as it provides a balanced measure of a model’s performance across both the majority (‘ham’) and minority (’spam’) classes.

For the lexical models (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, LightGBM), we employed an exhaustive grid search methodology. For Logistic Regression, this search included variations in the inverse regularization strength (C), the optimization solver, and the class weighting strategy. The Random Forest model was tuned over the number of trees in the ensemble, the maximum tree depth, and constraints on node splitting and leaf size. Similarly, for LightGBM, the grid covered key parameters such as the number of boosting iterations, learning rate, and tree structure controls.

Given the significantly larger search space and higher computational cost associated with the sequential and context-aware models (GRU and ALBERT), we utilized a randomized search approach. This method efficiently explores the hyperparameter space by sampling a fixed number of random configurations. For the GRU network, we optimized the embedding and hidden layer dimensions, the learning rate, and the number of training epochs. For the ALBERT model, the randomized search focused on identifying the optimal learning rate, dropout probability, and number of fine-tuning epochs.

This comprehensive tuning process was used to inform the selection of the final hyperparameters for the classical and GRU models. For the ALBERT model, the configuration yielding the highest validation F1-score was selected for the final evaluation. This provides a sound basis for our comparative analysis. The final set of selected hyperparameters for each of the five models is summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Model Performance: Quantifying Behavioral Complexity

The empirical results of our comparative analysis are presented in this section.

Table 2 summarizes the aggregate performance of all five models on the held-out test set, while

Table 3 provides a more granular, per-class breakdown of their predictive capabilities. These results are used to test our hypothesis of a two-tier structure in spam behavior.

3.2.1. Lexical Models (The ’simple Behavior’ Baseline)

Among the classical, lexical-based models, a clear performance ranking emerged. The gradient boosting model, LightGBM, showed the strongest results, achieving a weighted F1-score of 0.9082 and an AUC of 0.9581. It outperformed both the Logistic Regression baseline (F1: 0.9012) and the bagging-based Random Forest (F1: 0.8805). These findings establish a robust baseline, quantifying the upper limit of what can be achieved by modeling spam as a phenomenon of explicit, keyword-based features. The sequential, error-correcting nature of boosting appears particularly effective at capturing these explicit, non-linear feature interactions.

3.2.2. Sequential and Context-Aware Models (Capturing ‘Complex Behavior’)

The deep learning architectures provided a substantial, hierarchical improvement in performance. The GRU network, with its ability to model sequential dependencies, established a clear performance tier above the classical models, achieving a weighted F1-score of 0.9405 and a notably high AUC of 0.9816. The transformer-based ALBERT model, however, achieved the highest performance across all metrics with a weighted F1-score of 0.9695 and an AUC of 0.9943. This pattern is consistent with the interpretation that contextual self-attention representations can capture cues that are less accessible to TF–IDF lexical features on this dataset.

3.2.3. Evidence from the Minority ‘spam’ Class

The strongest evidence for our two-tiered behavioral hypothesis is found in the per-class performance on the minority ’spam’ class (

Table 3). While all models performed well on the majority ‘ham’ class, ALBERT achieved an F1-score of 0.95 for identifying spam. This is a dramatic improvement over the best classical model, LightGBM, which scored 0.84 on the same task. The GRU model also performed exceptionally well on this class with an F1-score of 0.90.

This performance gap is not merely a statistical improvement; instead, it is suggestive of a subset of spam messages in this corpus whose predictive signals are less concentrated in overt keywords and may be more context-dependent. This ‘complex’ spam relies on semantic and contextual strategies that are successfully captured by the ALBERT model but are missed by the simpler, keyword-based classical models.

3.3. Statistical Validation of Model Differences

To formally verify that these observed performance gaps—and thus the behavioral inferences they support—were not due to chance, we conducted pairwise McNemar’s tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction. This procedure rigorously evaluates whether the error patterns of two classifiers are significantly different on the same test set. The results are summarized in

Table 4.

The statistical analysis provides strong quantitative support for our findings. ALBERT was found to be statistically superior to every other model in the study (all corrected ). This confirms that the errors ALBERT avoids are systematically different from the errors made by all other models, validating the hypothesis that it is capturing a distinct and more complex set of linguistic patterns.

The results for the GRU indicate that it outperforms the classical lexical baselines with statistically significant differences in error patterns. Specifically, GRU was statistically superior to LightGBM, Logistic Regression, and Random Forest (all Holm-corrected

;

Table 4), while ALBERT remained statistically superior to GRU (Holm-corrected

). Together, these comparisons support a performance hierarchy in which contextual transformer representations yield the most distinct and robust improvements on this test set.

3.4. Linguistic Analysis of Explicit Spammer Strategies (The ‘simple’ Tier)

To build a qualitative understanding of the ‘simple’ spam tier, we conducted an analysis of the most influential TF-IDF features as determined by the classical models’ internal importance metrics. This interpretive step uses the models themselves as an analytical tool to reveal the key linguistic strategies spammers employ.

A primary finding was the strong consensus among Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and LightGBM regarding the core linguistic strategies of spam. All three models successfully learned to identify and prioritize terms belonging to several distinct thematic categories. These included:

Financial and Monetary Lures: Keywords explicitly related to money were highly predictive across all models, such as money, earn, profit, income, and investing.

Urgent Calls to Action: Words prompting immediate user interaction were consistently flagged as strong spam signals. This category includes verbs like click, join, visit, and dial, as well as the noun link.

Promotional/Credibility Lures: Superlative and offer-related terms were also identified as key indicators of spam, with words like free, prize, guaranteed, and offer ranking highly.

While there was significant thematic overlap, each model also provided unique insights. The Logistic Regression model was particularly notable because its linear coefficients allowed for a two-sided behavioral interpretation. It assigned large positive coefficients to the spam keywords mentioned above while simultaneously assigning large negative coefficients to terms indicative of legitimate, conversational content, such as wrote, date, research, and discus. This suggests its decision boundary was formed by both the presence of ‘spam’ linguistic markers and the absence of typical ‘ham’ language.

In contrast, the feature importance metrics for Random Forest and LightGBM, which are based on impurity reduction, primarily highlighted features predictive of the spam class. The Random Forest model, for example, ranked terms like channel and reply high in importance, suggesting it identified patterns related to Telegram-specific interactions or forwarded content. LightGBM showed a particularly strong focus on financial scam language, ranking terms like account and profit among its most important features. This interpretive analysis provides a clear, qualitative definition of the ‘simple’ or ‘lexical’ tier of spam behavior. It confirms that the classical models are highly transparent and succeeded in learning logical, consistent, and thematically relevant behavioral patterns from the text data.

3.5. Error Analysis: Illustrative ‘Complex-Tier’ Cases

To make the proposed ‘complex tier’ more concrete, we inspected test-set disagreement cases between lexical baselines (LR, Random Forest, LightGBM) and the context-aware transformer (ALBERT). We focus first on instances where lexical models predicted ham while the ground-truth label was spam, but ALBERT correctly predicted spam. The following lightly anonymized examples illustrate recurring patterns of lexically subtle deception:

-

Obfuscated recruitment / profit framing:

‘the rich always want to try out every paying but the poor area...ttle can build you huge profit...conttttttct ...’

True: spam; LR/RF/LGBM: ham; ALBERT: spam. The message uses compressed/obfuscated phrasing and an implicit profit promise rather than explicit spam keywords.

-

Formal ‘assistance’ scam register:

‘request assistance barrister ... chamber legal ... search reliable trustworthy person handle confidential trans...’

True: spam; LR/RF/LGBM: ham; ALBERT: spam. The deception is conveyed through narrative and formality rather than stereotypical promotional lexicon.

-

Conversational self-disclosure as bait:

‘im good im rocking 2 job one still marketing ... excluding salaryy im happy im freee ...’

True: spam; LR/RF/LGBM: ham; ALBERT: spam. The text resembles ordinary chat/self-update, with persuasive intent expressed indirectly.

For balance, we also examined inverse disagreement cases where lexical models were correct but ALBERT erred (i.e., or ). These cases were less frequent and typically involved highly formulaic, keyword-heavy messages that are well captured by surface lexical cues.

Across these disagreement sets, we observed several recurring categories: (i) obfuscated promotional/recruitment language, (ii) scams presented in formal narrative registers (e.g., ‘assistance’ scripts), and (iii) conversational bait in which the deceptive signal is expressed through indirect framing rather than overt spam keywords.

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive and computationally grounded analysis of deceptive linguistic behavior (spam) on the Telegram messaging platform. Using a large-scale, text-only dataset, we systematically examined how analytical models of varying complexity—from interpretable lexical models (Logistic Regression, LightGBM) to context-aware transformers (ALBERT)—capture this phenomenon. The findings yield critical insights into the linguistic strategies of spammers, moving beyond a simple accuracy benchmark to frame a more nuanced, structural understanding of deceptive communication in modern, high-velocity social ecosystems.

4.1. A Two-tier Structure of Deceptive Behavior

Our results are consistent with that spammer behavior on Telegram is not monolithic but operates on at least two distinct levels of linguistic complexity.

Although ALBERT consistently outperforms lexical baselines in our experiments, model performance alone does not identify the mechanism driving the improvement. The observed gains are consistent with the presence of a subset of deceptive messages whose signals are less concentrated in surface keywords and more distributed across context. However, alternative explanations remain plausible, including differences in model capacity and inductive bias, advantages conferred by large-scale pretraining, and improved handling of sparse patterns via subword representations. Accordingly, we treat “semantic/complex” as an operational description of lexically subtle messages in this corpus rather than a definitive causal claim about the evolution of spammer behavior.

The first tier is explicit and lexical. This tier consists of ‘traditional’ spam that relies on overt, high-signal keywords. Our analysis shows that this behavior is effectively modeled by classical, interpretable algorithms operating on TF-IDF features. The boosting-based LightGBM, as the frontrunner of this group (weighted F1: , AUC: ), quantifies the upper bound of this explicit tier. The strong performance of Logistic Regression (F1: ) further confirms that a large portion of spam is linearly separable based on these keywords.

The second tier is complex and semantic. This tier, which is ‘invisible’ to the lexical models, employs more sophisticated strategies. The deceptive signal is not in any single keyword but in the subtle contextual and semantic relationships between words, mimicking legitimate conversation. The statistically significant performance gap delivered by neural models is the primary evidence for this tier’s existence. The GRU, by modeling sequential dependencies, began to capture this (weighted F1: , AUC: ). However, the transformer-based ALBERT (weighted F1: , AUC: ) set a new state-of-the-art, suggesting that self-attention-based contextual modeling is better suited than lexical TF–IDF features for capturing certain distributed cues present in this dataset.

This two-tiered structure is most evident in the models’ ability to detect the minority spam class. ALBERT achieved an F1-score of on spam, a dramatic leap from LightGBM’s . This gap is not merely a performance metric; it is a proxy of the ‘complex’ tier of spam—a body of deceptive behavior that fundamentally lacks the explicit lexical cues the classical models rely on.

4.2. Statistical Significance of Model Differences

Pairwise McNemar’s tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction confirmed that these findings are statistically reliable. ALBERT’s superiority over all other models (all corrected ) is not a random artifact; it confirms that ALBERT is capturing a systematically different, and more complex, set of linguistic patterns. The GRU model also suggested a statistically significant advantage over all three classical models (LGBM, LR, and Random Forest; all ), suggesting its sequential lens captures behavioral patterns that are inaccessible to the lexical-only models. Within the classical group, the results showed no significant difference between LightGBM and Logistic Regression, but both were statistically superior to Random Forest.

4.3. Linguistic Strategies of the Explicit Tier

Accuracy may be insufficient for understanding behavior; interpretability is required. Our analysis of the classical models (

Section 3.4) provides a rich, qualitative definition of the ‘explicit tier’ of spam. The most influential TF-IDF features concentrated in three core behavioral themes: (i)

financial/promotional lures (

money,

profit,

income,

investing); (ii)

urgent calls to action (

click,

join,

http,

link); and (iii)

platform-specific context (

channel,

reply).

Notably, Logistic Regression’s bidirectional coefficients provided a two-sided insight: it learned to identify not only the presence of these spam markers but also the absence of terms indicative of legitimate conversation (e.g., wrote, date). This finding suggests that ‘ham’ (legitimate content) has its own strong behavioral norms, and spam’s deviation from these norms is as detectable as the spam content itself. These interpretable diagnostics are invaluable for auditing moderation policies and qualitatively understanding the baseline strategies of spammers.

4.4. Implications for Moderation Governance

These findings are best interpreted within moderation as a sociotechnical system rather than a standalone classifier. In practice, platforms operationalize governance through layered pipelines—automated screening, prioritization/triage, and human review under resource and accountability constraints. Our results therefore speak not only to predictive accuracy but also to institutional design choices: which content can be handled transparently and at scale, which requires context-aware escalation, and how model outputs can be integrated into auditable workflows that support appeals and oversight.

We discuss computational efficiency (e.g., model size and practical feasibility) as a motivating consideration for moderation pipelines; however, we do not report a controlled benchmarking study of latency, throughput, or memory footprint across models (which would depend on hardware, batching, tokenizer overhead, and implementation details). Accordingly, the deployment-related discussion is intended as a qualitative design implication rather than an empirically validated systems claim. Future work should include standardized runtime and memory benchmarks under clearly specified deployment settings.

This two-tiered behavioral model has direct implications for the governance and design of moderation systems:

Tier 1 Moderation (Transparent & Interpretable): The high performance of LightGBM (F1: 0.9082) confirms that a large volume of spam can be managed by efficient, transparent, and interpretable models. These models are ideal for ‘first-line’ moderation, as their decisions (based on explicit features) are auditable and can be directly mapped to community policies.

Tier 2 Moderation (Context-Aware & High-Recall): The existence of the semantic tier, which is only detectable by models like ALBERT (F1: 0.9695), proves that lexical-only systems may be insufficient. Addressing the most sophisticated spam—which is often the most dangerous (e.g., nuanced phishing)—requires context-aware models. These systems are necessary for high-recall, low-tolerance moderation of high-risk content.

Human-in-the-Loop Triage: A hybrid, two-tiered moderation framework is the natural conclusion. The interpretable classical models can automatically handle the explicit spam and provide clear justifications for human moderators, while calibrated probabilities from ALBERT can ‘flag’ high-risk, semantically complex content for expert review.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Although methodologically rigorous, this study opens several avenues for future computational social science research:

Cross-Linguistic and Multimodal Behavior: Our study was confined to English text. A critical next step is to analyze how deceptive strategies adapt across different languages (requiring models like mBERT/XLM-R) and modalities (e.g., the use of images, URLs, and attachments as part of the deceptive strategy).

Emoji and Paralinguistic Signals: Our preprocessing removed emojis, which can encode affect, salience, and visual persuasion in deceptive communication. Future work should evaluate emoji-aware pipelines (e.g., retaining emojis, mapping them to standardized tokens, or leveraging emoji embeddings) and quantify their contribution to detecting more subtle, context-dependent spam.

Updated Lightweight Transformers and LLM Embeddings: While we use ALBERT as a parameter-efficient contextual baseline, future work should benchmark newer compact transformers (e.g., DistilBERT, DeBERTa-v3 variants) and modern embedding-based classifiers to assess whether the observed ‘Tier 2’ gains persist across contemporary architectures.

Concept Drift as Adversarial Adaptation: This study presents a static snapshot of spammer behavior. However, spammers are adaptive adversaries who continuously evolve their tactics (‘concept drift’). Future work should move from static analysis to dynamic modeling, using continual learning and drift detectors to study this co-evolutionary arms race between spammers and moderation systems.

The Transparency-Performance Trade-off: We confirm a well-known trade-off: the most accurate models (transformers) are the least transparent. This poses a governance challenge. Future work in explainable AI (XAI), such as knowledge distillation into simpler, interpretable models or the use of attention maps for audits, is critical for making ‘Tier 2’ moderation systems accountable.

Asymmetric Harm and Cost-Sensitive Analysis: This study weighted recall and precision equally. However, the social harm of a false negative (missing a malicious phishing link) is far greater than that of a false positive (flagging a legitimate message). Future research should incorporate cost-sensitive metrics that model this asymmetric harm, reflecting the true social cost of moderation failure.

Threats to validity. We mitigated overfitting with strict train/validation/test separation, leakage controls (fit TF–IDF/tokenizers on train only), and statistical testing; residual risks include sample bias in the source corpus and unmodeled covariate shifts.

4.6. Conclusion

This study provides a computational analysis of deceptive messaging (spam) on Telegram using a hierarchy of model families, from interpretable lexical baselines to sequential and transformer-based architectures. We find that a large portion of spam is effectively captured by TF–IDF-based classical models, while context-aware representations yield substantial additional gains in spam-class detection.

Importantly, the observed performance gap between lexical models and ALBERT is suggestive of a subset of messages in this corpus whose deceptive signal is expressed in lexically subtle, context-dependent ways rather than through overt keywords. While model performance alone does not identify the underlying mechanism, the combined evidence from statistically validated comparisons and message-level error analysis supports interpreting Telegram spam in this dataset as comprising at least two practical detection regimes: an explicit, keyword-driven Tier 1 and a more context-dependent Tier 2.

From a governance perspective, these results motivate layered moderation pipelines in which transparent lexical models handle high-volume, high-signal spam, while context-aware models support higher-recall triage for harder cases. Future work should examine the robustness of this two-tier pattern under concept drift, multilingual and multimodal settings, emoji-aware preprocessing, and contemporary compact transformers or embedding-based classifiers, and should include standardized efficiency benchmarking under specified deployment conditions.

Funding

The authors declare no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. All work was conducted as independent researchers.

Data Availability Statement

Availability of Data and Materials: This study utilized the ‘Telegram Spam or Ham’ corpus, an open-source dataset available on Kaggle

‘Telegram Spam or Ham’ corpus. Code Availability: The full experimental pipeline and codebase will be released on the first author’s GitHub upon acceptance.

References

- Karim, A.; Azam, S.; Shanmugam, B.; Kannoorpatti, K.; Alazab, M. A Comprehensive Survey for Intelligent Spam Email Detection. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 168261–168295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, C.B.; Das, S.; Arsh, A.; Kar, N. A Survey on Phishing Attacks and Their Counter-Measures. In Intelligent Systems and Sustainable Computing (ICISSC 2022); Reddy, V.S.; Prasad, V.K.; Wang, J.; Rao Dasari, N.M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Vol. 363, Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.S. A statistical interpretation of term specificity and its application in retrieval. Journal of Documentation 1972, 28, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2017, pp. 3149–3157.

- Cho, K.; van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations Using RNN Encoder–Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2014, pp. 1724–1734.

- Lan, Z.; Chen, M.; Goodman, S.; Gimpel, K.; Sharma, P.; Soricut, R. ALBERT: A Lite BERT for self-supervised learning of language representations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2020.

- Cao, Y.; Dai, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y. Machine learning approaches for depression detection on social media: A systematic review of biases and methodological challenges. Journal of Behavioral Data Science 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Dai, J.; Cao, Y. A systematic review of machine learning approaches for detecting deceptive activities on social media: methods, challenges, and biases. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics 2025, 20, 6157–6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ding, Z.; Tian, Y.; Dai, J.; Shen, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y. Employing machine learning and deep learning models for mental illness detection. Computation 2025, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; Tian, Y.; Dai, J. Trade-offs between machine learning and deep learning for mental illness detection on social media. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 14497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mexwell, M.O. Telegram Spam or Ham, 2022. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/morninew/telegram-spam-or-ham-dataset.

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees; Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole Advanced Books & Software: Monterey, CA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, S.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z. An empirical comparison of machine learning and deep learning models for automated fake news detection. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tian, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z. Benchmarking machine learning and deep learning models for fake news detection using news headlines. Preprints 2025, article 2025061183. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNemar, Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika 1947, 12, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).