Submitted:

17 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Structure

3. Variants

3.1. Variants of Interest (VOI)

3.2. Variants of Concern (VOC)

3.3. Variants of High Consequence (VOHC)

3.4. Major Variants of Coronavirus

3.4.1. Alpha (B.1.1.7)

3.4.2. Beta (B.1.351)

3.4.3. Gamma (P.1)

3.4.4. Delta (B.1.617.2)

3.4.5. Omicron (B.1.1.529)

4. Mechanism of Action

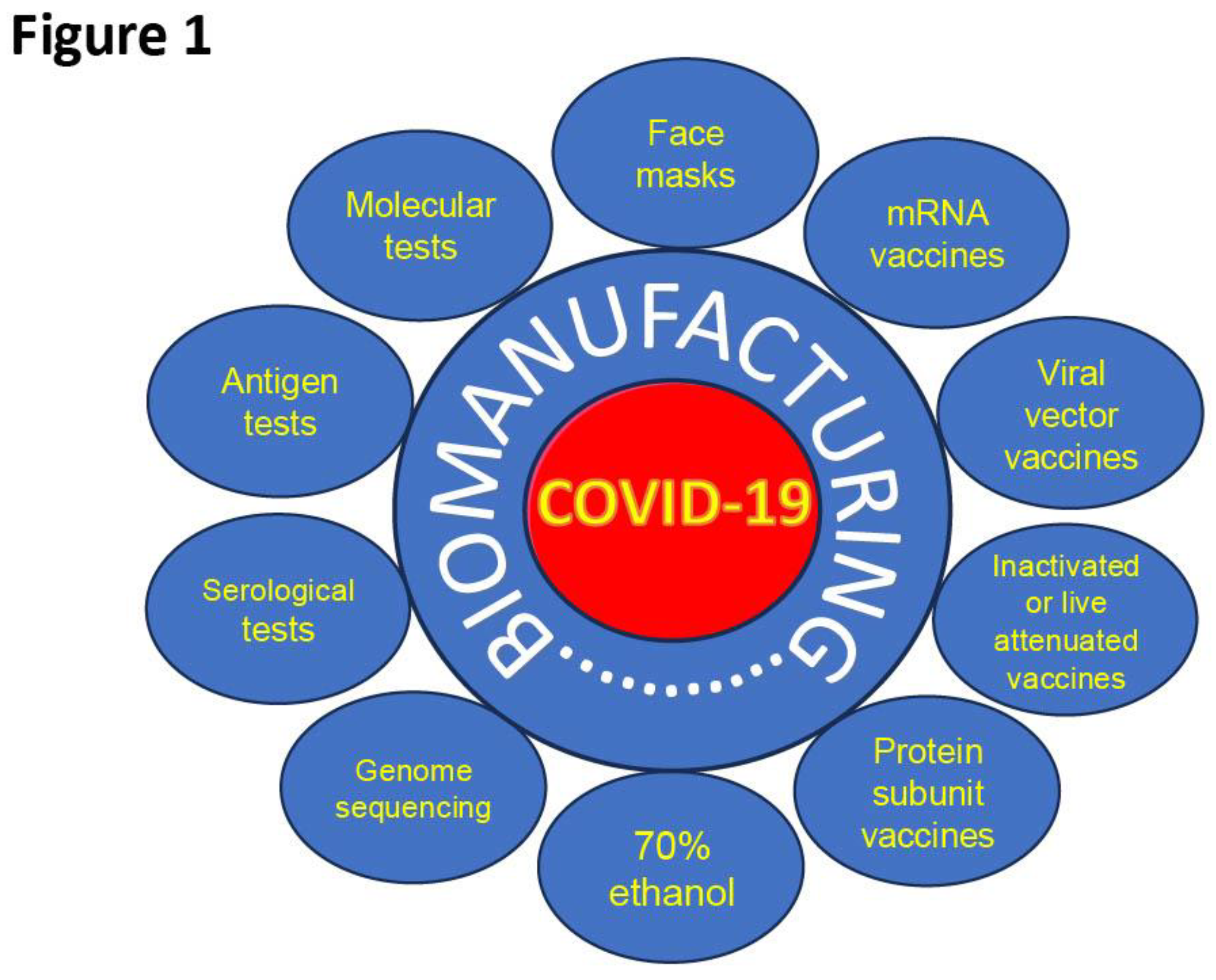

5. Response of Biomanufacturing Industry to COVID-19 Pandemic

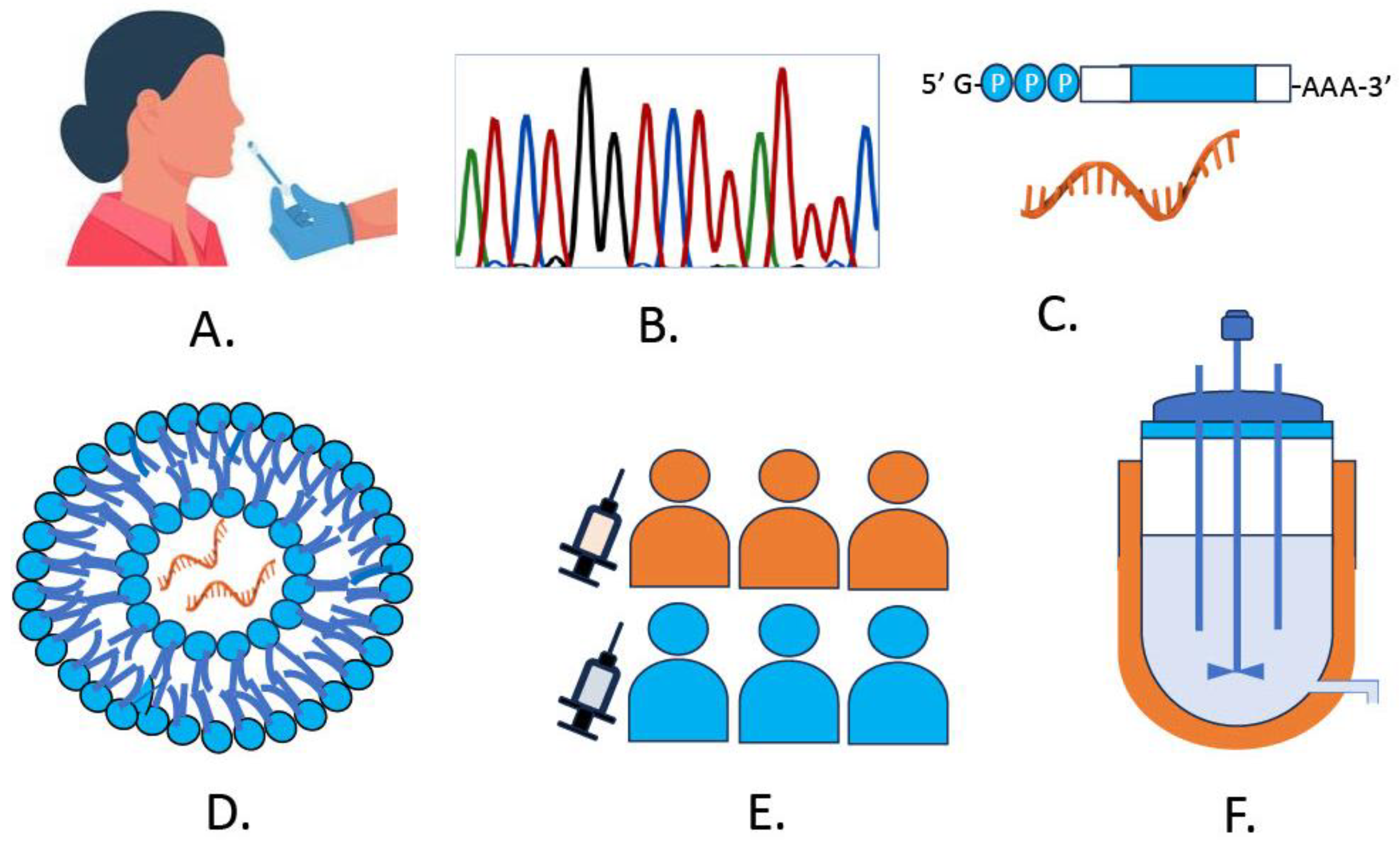

5.1. SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic Approaches

5.1.1. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

5.1.2. Antigen Rapid Diagnostic Test

5.1.3. Serology Test

5.1.4. Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP)

5.1.5. Next-Generation Sequencing

5.1.6. Nanotechnology Approaches in SARS-CoV-2 Diagnosis

6. Development of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccines

6.1. Vaccine Candidates

6.2. Design and Modifications to mRNA

6.3. Delivery of mRNA Vaccines

6.4. Advantages, Limitations and Caveats

6.5. Innovations in Large-Scale mRNA Vaccines and Diagnostics

6.5.1. Workforce and Expertise Gaps

7. Discussion

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Zhou, P; Yang, X-L; Wang, X-G; Hu, B; Zhang, L; Zhang, W; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R; Zhao, X; Li, J; Niu, P; Yang, B; Wu, H; et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, S; Herbert, JA; McNamara, PS; Hedrich, CM. COVID-19: Immunology and treatment options. Clinical Immunology 2020, 215, 108448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiyeh, P; Borhani-Haghighi, A; Karimzadeh, I; Mohammadi-Samani, S; Vazin, A; Safari, A; et al. Major Neurologic Adverse Drug Reactions, Potential Drug–Drug Interactions and Pharmacokinetic Aspects of Drugs Used in COVID-19 Patients with Stroke: A Narrative Review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2020, 16, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigel, JH; Tomashek, KM; Dodd, LE; Mehta, AK; Zingman, BS; Kalil, AC; et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnupiravir in unvaccinated patients with COVID-19. Drug Ther Bull 2022, 60, 35–35. [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulos, A; Mylonakis, E. In patients with COVID-19 at risk for severe disease, nirmatrelvir + ritonavir reduced hospitalization or death. Ann Intern Med 2022, 175, JC63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R; Chaudhary, JK; Jain, N; Chaudhary, PK; Khanra, S; Dhamija, P; et al. Role of Structural and Non-Structural Proteins and Therapeutic Targets of SARS-CoV-2 for COVID-19. Cells 2021, 10, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W; Zheng, Y; Zeng, X; He, B; Cheng, W. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2: open the door for novel therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, B; Urakova, N; Snijder, EJ; Campbell, EA. Structures and functions of coronavirus replication–transcription complexes and their relevance for SARS-CoV-2 drug design. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian, DA; Baric, RS. Coronavirus Genome Structure and Replication; 2005; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, DA; Anand Narayanan, S; Trovão, NS; Guarnieri, JW; Topper, MJ; Moraes-Vieira, PM; et al. A comprehensive SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 review, Part 1: Intracellular overdrive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. European Journal of Human Genetics 2022, 30, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W; Zheng, Y; Zeng, X; He, B; Cheng, W. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2: open the door for novel therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W; Cheng, Y; Zhou, H; Sun, C; Zhang, S. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein: its role in the viral life cycle, structure and functions, and use as a potential target in the development of vaccines and diagnostics. Virol J 2023, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z; Nomura, N; Muramoto, Y; Ekimoto, T; Uemura, T; Liu, K; et al. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 membrane protein essential for virus assembly. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oronsky, B; Larson, C; Caroen, S; Hedjran, F; Sanchez, A; Prokopenko, E; et al. Nucleocapsid as a next-generation COVID-19 vaccine candidate. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022, 122, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, AC; Mohsin, I. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein as a Drug and Vaccine Target: Structural Insights into Its Complexes with ACE2 and Antibodies. Cells 2020, 9, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeling, RW; Heymann, DL; Teo, Y-Y; Garcia, PJ. Diagnostics for COVID-19: moving from pandemic response to control. The Lancet 2022, 399, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M; Kleine-Weber, H; Schroeder, S; Krüger, N; Herrler, T; Erichsen, S; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, A; Akbar Samad, AB; Vaqar, S. Emerging Variants of SARS-CoV-2 and Novel Therapeutics Against Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Scovino, AM; Dahab, EC; Vieira, GF; Freire-de-Lima, L; Freire-de-Lima, CG; Morrot, A. SARS-CoV-2’s Variants of Concern: A Brief Characterization. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J; Lan, W; Wu, X; Zhao, T; Duan, B; Yang, P; et al. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Omicron diverse spike gene mutations identifies multiple inter-variant recombination events. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, KC; Castro, J; Lambrou, AS; Rose, EB; Cook, PW; Batra, D; et al. Genomic Surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Circulation of Omicron XBB and JN.1 Lineages — United States, May 2023–September 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024, 73, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Vaziri, M; Fazlalipour, M; Seyed Khorrami, SM; Azadmanesh, K; Pouriayevali, MH; Jalali, T; et al. The ins and outs of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs). Arch Virol 2022, 167, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, NG; Abbott, S; Barnard, RC; Jarvis, CI; Kucharski, AJ; Munday, JD; et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science (1979) 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegally, H; Wilkinson, E; Giovanetti, M; Iranzadeh, A; Fonseca, V; Giandhari, J; et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature 2021, 592, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Expression of concern on: Comparative genomics and characterization of SARS-CoV-2 P.1 (Gamma) variant of concern from Amazonas, Brazil. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Mlcochova, P; Kemp, SA; Dhar, MS; Papa, G; Meng, B; Ferreira, IATM; et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 Delta variant replication and immune evasion. Nature 2021, 599, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, BJ; Grove, J; MacLean, OA; Wilkie, C; De Lorenzo, G; Furnon, W; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nat Microbiol 2022, 7, 1161–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mambelli, F; de Araujo, ACVSC; Farias, JP; de Andrade, KQ; Ferreira, LCS; Minoprio, P; et al. An Update on Anti-COVID-19 Vaccines and the Challenges to Protect Against New SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Pathogens 2025, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umakanthan, S; Chattu, VK; Ranade, A V; Das, D; Basavarajegowda, A; Bukelo, M. A rapid review of recent advances in diagnosis, treatment and vaccination for COVID-19. AIMS Public Health 2021, 8, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, AC; Park, Y-J; Tortorici, MA; Wall, A; McGuire, AT; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartenian, E; Nandakumar, D; Lari, A; Ly, M; Tucker, JM; Glaunsinger, BA. The molecular virology of coronaviruses. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295, 12910–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, EJ; Limpens, RWAL; de Wilde, AH; de Jong, AWM; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, JC; Maier, HJ; et al. A unifying structural and functional model of the coronavirus replication organelle: Tracking down RNA synthesis. PLoS Biol 2020, 18, e3000715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S; Cortese, M; Winter, SL; Wachsmuth-Melm, M; Neufeldt, CJ; Cerikan, B; et al. SARS-CoV-2 structure and replication characterized by in situ cryo-electron tomography. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V’kovski, P; Kratzel, A; Steiner, S; Stalder, H; Thiel, V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, W; Ni, Z; Hu, Y; Liang, W; Ou, C; He, J; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D; Naiyer, S; Mansuri, S; Soni, N; Singh, V; Bhat, KH; et al. COVID-19 Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review of the RT-qPCR Method for Detection of SARS-CoV-2. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drain, PK. Rapid Diagnostic Testing for SARS-CoV-2. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 386, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X; Wang, L; Sakthivel, SK; Whitaker, B; Murray, J; Kamili, S; et al. US CDC Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR Panel for Detection of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis 2020, 26, 1654–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, MP; Papenburg, J; Desjardins, M; Kanjilal, S; Quach, C; Libman, M; et al. Diagnostic Testing for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome–Related Coronavirus 2. Ann Intern Med 2020, 172, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D; Naiyer, S; Mansuri, S; Soni, N; Singh, V; Bhat, KH; et al. COVID-19 Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review of the RT-qPCR Method for Detection of SARS-CoV-2. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, VT; Schwartz, NG; Donnelly, MAP; Chuey, MR; Soto, R; Yousaf, AR; et al. Comparison of Home Antigen Testing With RT-PCR and Viral Culture During the Course of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Intern Med 2022, 182, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corman, VM; Landt, O; Kaiser, M; Molenkamp, R; Meijer, A; Chu, DK; et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R; Han, H; Liu, F; Lv, Z; Wu, K; Liu, Y; et al. Positive rate of RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 4880 cases from one hospital in Wuhan, China, from Jan to Feb 2020. Clinica Chimica Acta 2020, 505, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z; Xiao, Y; Kang, L; Ma, W; Shi, L; Zhang, L; et al. Genomic Diversity of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome–Coronavirus 2 in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020, 71, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Romero, CA; Mendoza-Maldonado, L; Tonda, A; Coz, E; Tabeling, P; Vanhomwegen, J; et al. An Innovative AI-based primer design tool for precise and accurate detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 15782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeling, RW; Olliaro, PL; Boeras, DI; Fongwen, N. Scaling up COVID-19 rapid antigen tests: promises and challenges. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, e290–e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brümmer, LE; Katzenschlager, S; Gaeddert, M; Erdmann, C; Schmitz, S; Bota, M; et al. Accuracy of novel antigen rapid diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2: A living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021, 18, e1003735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildgen, V; Demuth, S; Lüsebrink, J; Schildgen, O. Limits and Opportunities of SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Rapid Tests: An Experienced-Based Perspective. Pathogens 2021, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, SJ; Kompaniyets, L; Freedman, DS; Kraus, EM; Porter, R; Blanck, HM; et al. Longitudinal Trends in Body Mass Index Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Persons Aged 2–19 Years — United States, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohmer, N; Toptan, T; Pallas, C; Karaca, O; Pfeiffer, A; Westhaus, S; et al. The Comparative Clinical Performance of Four SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Tests and Their Correlation to Infectivity In Vitro. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriquin, G; LeBlanc, JJ; Williams, C; Hatchette, TF; Ross, J; Barrett, L; et al. Comparison between Nasal and Nasopharyngeal Swabs for SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Detection in an Asymptomatic Population, and Direct Confirmation by RT-PCR from the Residual Buffer. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinnes, J; Berhane, S; Walsh, J; Reidy, P; Doherty, A; Hillier, B; et al. Rapid, point-of-care antigen tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshadi, M; Fardsanei, F; Deihim, B; Farshadzadeh, Z; Nikkhahi, F; Khalili, F; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Rapid Antigen Tests for COVID-19 Detection: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baro, B; Rodo, P; Ouchi, D; Bordoy, AE; Saya Amaro, EN; Salsench, S V.; et al. Performance characteristics of five antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic test (Ag-RDT) for SARS-CoV-2 asymptomatic infection: a head-to-head benchmark comparison. Journal of Infection 2021, 82, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, AE; Bennett, JC; Luiten, K; O’Hanlon, JA; Wolf, CR; Magedson, A; et al. Comparative Diagnostic Utility of SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen and Molecular Testing in a Community Setting. J Infect Dis 2024, 230, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenhäuser, I; Knies, K; Pscheidl, T; Eisenmann, M; Flemming, S; Petri, N; et al. SARS-CoV-2 antigen rapid detection tests: test performance during the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of COVID-19 vaccination. EBioMedicine 2024, 109, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derin, DÇ; Gültekin, E. Design of a lateral flow assay targeting the conserved NIID_2019-nCoV_N gene region for molecular viral diagnosis. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2025, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A; Tripathi, P; Kumar, P; Shekhar, R; Pathak, R. From Detection to Protection: Antibodies and Their Crucial Role in Diagnosing and Combatting SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevadiya, BD; Machhi, J; Herskovitz, J; Oleynikov, MD; Blomberg, WR; Bajwa, N; et al. Diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Mater 2021, 20, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udugama, B; Kadhiresan, P; Kozlowski, HN; Malekjahani, A; Osborne, M; Li, VYC; et al. Diagnosing COVID-19: The Disease and Tools for Detection. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 3822–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q-X; Tang, X-J; Shi, Q-L; Li, Q; Deng, H-J; Yuan, J; et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S; Singh, KR; Verma, R; Singh, J; Singh, RP. State-of-the-Art Smart and Intelligent Nanobiosensors for SARS-CoV-2 Diagnosis. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 12, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G; Moehling, TJ; Meagher, RJ. Advances in RT-LAMP for COVID-19 testing and diagnosis. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2023, 23, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, RS; de Oliveira Silva, J; Gomes, KB; Azevedo, RB; Townsend, DM; de Paula Sabino, A; et al. Recent advances in point of care testing for COVID-19 detection. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 153, 113538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behjati, S; Tarpey, PS. What is next generation sequencing? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2013, 98, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y; McCauley, J. GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data – from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, EL; Zhdanov, SA; Bao, Y; Blinkova, O; Nawrocki, EP; Ostapchuck, Y; et al. Virus Variation Resource – improved response to emergent viral outbreaks. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D482–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W-M; Song, S-H; Chen, M-L; Zou, D; Ma, L-N; Ma, Y-K; et al. The 2019 novel coronavirus resource. Yi Chuan 2020, 42, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y; Zmasek, C; Sun, G; Larsen, CN; Scheuermann, RH. Hepatitis C Virus Database and Bioinformatics Analysis Tools in the Virus Pathogen Resource (ViPR); 2019; pp. 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N; Zhang, D; Wang, W; Li, X; Yang, B; Song, J; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H; Chen, X; Hu, T; Li, J; Song, H; Liu, Y; et al. A Novel Bat Coronavirus Closely Related to SARS-CoV-2 Contains Natural Insertions at the S1/S2 Cleavage Site of the Spike Protein. Current Biology 2020, 30, 2196–2203.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X; Kang, Y; Luo, J; Pang, K; Xu, X; Wu, J; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Reveals the Progression of COVID-19. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramuta, MD; Newman, CM; Brakefield, SF; Stauss, MR; Wiseman, RW; Kita-Yarbro, A; et al. SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens are detected in continuous air samples from congregate settings. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, NR; Ramuta, MD; Stauss, MR; Harwood, OE; Brakefield, SF; Alberts, A; et al. Metagenomic sequencing detects human respiratory and enteric viruses in air samples collected from congregate settings. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 21398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, KG; Rambaut, A; Lipkin, WI; Holmes, EC; Garry, RF. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, HM; Kim, I-H; Kim, S. Nucleic Acid Testing of SARS-CoV-2. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, GS; Sardi, SI; Falcao, MB; Belitardo, EMMA; Rocha, DJPG; Rolo, CA; et al. Ion torrent-based nasopharyngeal swab metatranscriptomics in COVID-19. J Virol Methods 2020, 282, 113888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paden, CR; Tao, Y; Queen, K; Zhang, J; Li, Y; Uehara, A; et al. Rapid, Sensitive, Full-Genome Sequencing of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis 2020, 26, 2401–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillay, S; Giandhari, J; Tegally, H; Wilkinson, E; Chimukangara, B; Lessells, R; et al. Whole Genome Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: Adapting Illumina Protocols for Quick and Accurate Outbreak Investigation during a Pandemic. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercatelli, D; Holding, AN; Giorgi, FM. Web tools to fight pandemics: the COVID-19 experience. Brief Bioinform 2021, 22, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T; Li, J; Zhou, H; Li, C; Holmes, EC; Shi, W. Bioinformatics resources for SARS-CoV-2 discovery and surveillance. Brief Bioinform 2021, 22, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I; Yusuf, K; Roy, BC; Stubbs, J; Anant, S; Attard, TM; et al. Dietary Interventions Ameliorate Infectious Colitis by Restoring the Microbiome and Promoting Stem Cell Proliferation in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I; Roy, BC; Raach, R-MT; Owens, SM; Xia, L; Anant, S; et al. Enteric infection coupled with chronic Notch pathway inhibition alters colonic mucus composition leading to dysbiosis, barrier disruption and colitis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0206701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charre, C; Ginevra, C; Sabatier, M; Regue, H; Destras, G; Brun, S; et al. Evaluation of NGS-based approaches for SARS-CoV-2 whole genome characterisation. Virus Evol 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, R; Moyo, S; Amoako, DG; Tegally, H; Scheepers, C; Althaus, CL; et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature 2022, 603, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R; Hozumi, Y; Yin, C; Wei, G-W. Mutations on COVID-19 diagnostic targets. Genomics 2020, 112, 5204–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviña-Núñez, C; Pérez, S; Cabrera-Alvargonzález, JJ; Rincón-Quintero, A; Treinta-Álvarez, A; Godoy-Diz, M; et al. Performance of amplicon and capture based next-generation sequencing approaches for the epidemiological surveillance of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 and other variants of concern. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0289188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, L; McCrone, JT; Zarebski, AE; Hill, V; Ruis, C; Gutierrez, B; et al. Establishment and lineage dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the UK. Science 2021, 371, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A; Javaid, M; Singh, RP; Rab, S; Suman, R. Applications of nanotechnology in medical field: a brief review. Global Health Journal 2023, 7, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P; Singh, D; Sa, P; Mohapatra, P; Khuntia, A; K Sahoo, S. Insights From Nanotechnology in COVID-19: Prevention, Detection, Therapy and Immunomodulation. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1219–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, S; Aranci-Ciftci, K; Ciftci, F; Ustundag, CB. Nanotechnology and COVID-19: Prevention, diagnosis, vaccine, and treatment strategies. Front Mater 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A; Kontodimas, K; Bosmann, M. Nanomedicine: A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach to COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela-Fernández, A; Cabrera-Rodriguez, R; Ciuffreda, L; Perez-Yanes, S; Estevez-Herrera, J; González-Montelongo, R; et al. Nanomaterials to combat SARS-CoV-2: Strategies to prevent, diagnose and treat COVID-19. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalaili, B; Popescu, IN; Kamoun, O; Alzubi, F; Alawadhia, S; Vidu, R. Nanobiosensors for the Detection of Novel Coronavirus 2019-nCoV and Other Pandemic/Epidemic Respiratory Viruses: A Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, TL; Anastácio, R; da Silva, SS; de Oliveira, CC; Vidotti, M. An overview of electrochemical biosensors used for COVID-19 detection. Analytical Methods 2024, 16, 2164–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, YS; Kul, SM; Sagdic, O; Rodthongkum, N; Geiss, B; Ozer, T. Optical biosensors for diagnosis of COVID-19: nanomaterial-enabled particle strategies for post pandemic era. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Ur-Rashid, M; Foyez, T; Jahan, I; Pal, K; Imran, A.B. Rapid diagnosis of COVID-19 via nano-biosensor-implemented biomedical utilization: a systematic review. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 9445–9465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N; Hogan, MJ; Porter, FW; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, F; Krishnan, S; Lenzen, G; Magné, R; Gomard, E; Guillet, J; et al. Induction of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo by liposome-entrapped mRNA. Eur J Immunol 1993, 23, 1719–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRENNER, S; JACOB, F; MESELSON, M. An Unstable Intermediate Carrying Information from Genes to Ribosomes for Protein Synthesis. Nature 1961, 190, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockard, RE; Lingrel, JB. The synthesis of mouse hemoglobin chains in a rabbit reticulocyte cell-free system programmed with mouse reticulocyte 9S RNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1969, 37, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieg, PA; Melton, DA. 25] In vitro RNA synthesis with SP6 RNA polymerase; 1987; pp. 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, PA; Melton, DA. Functional messenger RNAs are produced by SP6 in vitro transcription of cloned cDNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 1984, 12, 7057–7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, RW; Felgner, PL; Verma, IM. Cationic liposome-mediated RNA transfection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1989, 86, 6077–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, JA; Budker, V. The Mechanism of Naked DNA Uptake and Expression; 2005; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirikowski, GF; Sanna, PP; Maciejewski-Lenoir, D; Bloom, FE. Reversal of Diabetes Insipidus in Brattleboro Rats: Intrahypothalamic Injection of Vasopressin mRNA. Science (1979) 1992, 255, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, KJ; Benenato, KE; Jacquinet, E; Lee, A; Woods, A; Yuzhakov, O; et al. Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticles for Intramuscular Administration of mRNA Vaccines. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2019, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conry, RM; LoBuglio, AF; Loechel, F; Moore, SE; Sumerel, LA; Barlow, DL; et al. A carcinoembryonic antigen polynucleotide vaccine has in vivo antitumor activity. Gene Ther 1995, 2, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Karikó, K; Ni, H; Capodici, J; Lamphier, M; Weissman, D. mRNA Is an Endogenous Ligand for Toll-like Receptor 3. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 12542–12550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries, O; Mc Cafferty, S; De Smedt, SC; Weiss, R; Sanders, NN; Kitada, T. N1-methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. Journal of Controlled Release 2015, 217, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K; Muramatsu, H; Ludwig, J; Weissman, D. Generating the optimal mRNA for therapy: HPLC purification eliminates immune activation and improves translation of nucleoside-modified, protein-encoding mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, e142–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karikó, K; Buckstein, M; Ni, H; Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors: The Impact of Nucleoside Modification and the Evolutionary Origin of RNA. Immunity 2005, 23, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y-Z; Holmes, EC. A Genomic Perspective on the Origin and Emergence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell 2020, 181, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, NE; Vlková, M; Faisal, MB; Silander, OK. Rapid and inexpensive whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 using 1200 bp tiled amplicons and Oxford Nanopore Rapid Barcoding. Biol Methods Protoc 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D; Wang, N; Corbett, KS; Goldsmith, JA; Hsieh, C-L; Abiona, O; et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science (1979) 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, KS; Edwards, D; Leist, SR; Abiona, OM; Boyoglu-Barnum, S; Gillespie, RA; et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Development Enabled by Prototype Pathogen Preparedness 2020. [CrossRef]

- Polack, FP; Thomas, SJ; Kitchin, N; Absalon, J; Gurtman, A; Lockhart, S; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, LR; El Sahly, HM; Essink, B; Kotloff, K; Frey, S; Novak, R; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoff, J; Gray, G; Vandebosch, A; Cárdenas, V; Shukarev, G; Grinsztejn, B; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384, 2187–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z; Chen, J-L; Lu, Y; Wang, B; Godfrey, L; Mentzer, AJ; et al. Evaluation of T cell responses to naturally processed variant SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens in individuals following infection or vaccination. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 112470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamandjou Tchuem, CR; Auvigne, V; Vaux, S; Montagnat, C; Paireau, J; Monnier Besnard, S; et al. Vaccine effectiveness and duration of protection of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines against Delta and Omicron BA.1 symptomatic and severe COVID-19 outcomes in adults aged 50 years and over in France. Vaccine 2023, 41, 2280–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, AA; Kirsebom, F; Stowe, J; Ramsay, ME; Lopez-Bernal, J; Andrews, N; et al. Protection against symptomatic infection with delta (B.1.617.2) and omicron (B.1.1.529) BA.1 and BA.2 SARS-CoV-2 variants after previous infection and vaccination in adolescents in England, August, 2021–March, 2022: a national, observational, test-negative, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raddad, LJ; Chemaitelly, H; Ayoub, HH; AlMukdad, S; Yassine, HM; Al-Khatib, HA; et al. Effect of mRNA Vaccine Boosters against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Infection in Qatar. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 386, 1804–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, FX; Stiasny, K. Profiles of current COVID-19 vaccines. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2021, 133, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ada, GL. The ideal vaccine. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 1991, 7, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, HF; Kleiner, R; Vaskovich-Koubi, D; Acúrcio, RC; Carreira, B; Yeini, E; et al. Immune-mediated approaches against COVID-19. Nat Nanotechnol 2020, 15, 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, T; Srivastava, N; Mishra, G; Dhama, K; Kumar, S; Puri, B; et al. Recombinant vaccines for COVID-19. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16, 2905–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Guardeño, JM; Regla-Nava, JA; Nieto-Torres, JL; DeDiego, ML; Castaño-Rodriguez, C; Fernandez-Delgado, R; et al. Identification of the Mechanisms Causing Reversion to Virulence in an Attenuated SARS-CoV for the Design of a Genetically Stable Vaccine. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11, e1005215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y; Dai, T; Wei, Y; Zhang, L; Zheng, M; Zhou, F. A systematic review of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, PJ; Bottazzi, ME. Whole Inactivated Virus and Protein-Based COVID-19 Vaccines. Annu Rev Med 2022, 73, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Welder, JH; Torres, MP; Kipper, MJ; Mallapragada, SK; Wannemuehler, MJ; Narasimhan, B. Vaccine adjuvants: Current challenges and future approaches. J Pharm Sci 2009, 98, 1278–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, PT; Galiza, EP; Baxter, DN; Boffito, M; Browne, D; Burns, F; et al. Safety and Efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 1172–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keech, C; Albert, G; Cho, I; Robertson, A; Reed, P; Neal, S; et al. Phase 1–2 Trial of a SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant Spike Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 2320–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConeghy, KW; Davidson, HE; Canaday, DH; Han, L; Hayes, K; Baier, RR; et al. Recombinant vs Egg-Based Quadrivalent Influenza Vaccination for Nursing Home Residents. JAMA Netw Open 2025, 8, e2452677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T; Takano, T; Takahashi, Y. Immune responses related to the immunogenicity and reactogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Int Immunol 2023, 35, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L; Zheng, Q; Zhang, H; Niu, Y; Lou, Y; Wang, H. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Biosynthesis, Structure, Function, and Antigenicity: Implications for the Design of Spike-Based Vaccine Immunogens. Front Immunol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K; Huang, B; Wu, M; Zhong, A; Li, L; Cai, Y; et al. Dynamic changes in anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies during SARS-CoV-2 infection and recovery from COVID-19. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y; Yang, C; Xu, X; Xu, W; Liu, S. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2020, 41, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, R. mRNA and Adenoviral Vector Vaccine Platforms Utilized in COVID-19 Vaccines: Technologies, Ecosystem, and Future Directions. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N; Hogan, MJ; Porter, FW; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, SC; Sekhon, SS; Shin, W-R; Ahn, G; Cho, B-K; Ahn, J-Y; et al. Modifications of mRNA vaccine structural elements for improving mRNA stability and translation efficiency. Mol Cell Toxicol 2022, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, FP; Thomas, SJ; Kitchin, N; Absalon, J; Gurtman, A; Lockhart, S; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, EE; Pérez Marc, G; Zareba, AM; Falsey, AR; Jiang, Q; Patton, M; et al. Efficacy and Safety of a Bivalent RSV Prefusion F Vaccine in Older Adults. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugridge, JS; Coller, J; Gross, JD. Structural and molecular mechanisms for the control of eukaryotic 5′–3′ mRNA decay. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2018, 25, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N; Weissman, D; Whitehead, KA. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S; Pal, JK. Role of 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of mRNAs in human diseases. Biol Cell 2009, 101, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, J; Schmeing, TM; Sonenberg, N. The multifaceted eukaryotic cap structure. WIREs RNA 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuller, T; Zur, H. Multiple roles of the coding sequence 5′ end in gene expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courel, M; Clément, Y; Bossevain, C; Foretek, D; Vidal Cruchez, O; Yi, Z; et al. GC content shapes mRNA storage and decay in human cells. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudla, G; Lipinski, L; Caffin, F; Helwak, A; Zylicz, M. High Guanine and Cytosine Content Increases mRNA Levels in Mammalian Cells. PLoS Biol 2006, 4, e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J; Fernandes, R; Romão, L. Translational Regulation by Upstream Open Reading Frames and Human Diseases; 2019; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, CR; Rammelt, C; Wahle, E. Control of poly(A) tail length. WIREs RNA 2011, 2, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biziaev, N; Shuvalov, A; Salman, A; Egorova, T; Shuvalova, E; Alkalaeva, E. The impact of mRNA poly(A) tail length on eukaryotic translation stages. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, 7792–7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardi, N; Hogan, MJ; Porter, FW; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S; Satapathy, SR; Dutta, T. Delivery Strategies for mRNA Vaccines. Pharmaceut Med 2022, 36, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S; Huang, X; Xue, Y; Álvarez-Benedicto, E; Shi, Y; Chen, W; et al. Nanotechnology-based mRNA vaccines. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2023, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiaie, SH; Majidi Zolbanin, N; Ahmadi, A; Bagherifar, R; Valizadeh, H; Kashanchi, F; et al. Recent advances in mRNA-LNP therapeutics: immunological and pharmacological aspects. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, N; Chakka, LRJ; Zhang, Y; Maniruzzaman, M. Fabrication of mRNA encapsulated lipid nanoparticles using state of the art SMART-MaGIC technology and transfection in vitro. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 22714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiaie, SH; Majidi Zolbanin, N; Ahmadi, A; Bagherifar, R; Valizadeh, H; Kashanchi, F; et al. Recent advances in mRNA-LNP therapeutics: immunological and pharmacological aspects. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, PS; Rudra, A; Miao, L; Anderson, DG. Delivering the Messenger: Advances in Technologies for Therapeutic mRNA Delivery. Molecular Therapy 2019, 27, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, LA; Anderson, EJ; Rouphael, NG; Roberts, PC; Makhene, M; Coler, RN; et al. An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 — Preliminary Report. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, R; Lentacker, I; De Smedt, SC; Dewitte, H. The dawn of mRNA vaccines: The COVID-19 case. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 333, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X; Zaks, T; Langer, R; Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater 2021, 6, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X; Qi, J; Wang, J; Hu, W; Zhou, W; Wang, Y; et al. Nanoparticle technology for mRNA: Delivery strategy, clinical application and developmental landscape. Theranostics 2024, 14, 738–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, PC. [Peter Plett and other discoverers of cowpox vaccination before Edward Jenner]. Sudhoffs Arch 2006, 90, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jenner, E. Dr. Jenner, on the Vaccine Inoculation. Med Phys J 1800, 3, 502–503. [Google Scholar]

- Maruggi, G; Zhang, C; Li, J; Ulmer, JB; Yu, D. mRNA as a Transformative Technology for Vaccine Development to Control Infectious Diseases. Molecular Therapy 2019, 27, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature 2020, 586, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fresneda, MA; Ruiz-Pérez, R; Ruiz-Fresneda, C; Jiménez-Contreras, E. Differences in Global Scientific Production Between New mRNA and Conventional Vaccines Against COVID-19. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 57054–57066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, AJ; Bijker, EM. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat Rev Immunol 2021, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y-S; Kumari, M; Chen, G-H; Hong, M-H; Yuan, JP-Y; Tsai, J-L; et al. mRNA-based vaccines and therapeutics: an in-depth survey of current and upcoming clinical applications. J Biomed Sci 2023, 30, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Ye, Q. Safety and Efficacy of the Common Vaccines against COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patone, M; Mei, XW; Handunnetthi, L; Dixon, S; Zaccardi, F; Shankar-Hari, M; et al. Risk of Myocarditis After Sequential Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine and SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Age and Sex. Circulation 2022, 146, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S; Yang, K; Li, R; Zhang, L. mRNA Vaccine Era—Mechanisms, Drug Platform and Clinical Prospection. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echaide, M; Chocarro de Erauso, L; Bocanegra, A; Blanco, E; Kochan, G; Escors, D. mRNA Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2: Advantages and Caveats. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J; Ding, Y; Chong, K; Cui, M; Cao, Z; Tang, C; et al. Recent Advances in Lipid Nanoparticles and Their Safety Concerns for mRNA Delivery. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C; Ip, S; Bathula, N V.; Popova, P; Soriano, SK V.; Ly, HH; et al. Current Status and Future Perspectives on MRNA Drug Manufacturing. Mol Pharm 2022, 19, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SeyedAlinaghi, S; Karimi, A; Pashaei, Z; Afzalian, A; Mirzapour, P; Ghorbanzadeh, K; et al. Safety and Adverse Events Related to COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines; a Systematic Review. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2022, 10, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddema, JJ; Fernald, KDS; Schikan, HGCP; van de Burgwal, LHM. Upscaling vaccine manufacturing capacity - key bottlenecks and lessons learned. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4359–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, SM; Rosen, AM; Edwards, D; Bolio, A; Larson, HJ; Servin, M; et al. Opportunities and challenges to implementing mRNA-based vaccines and medicines: lessons from COVID-19. Front Public Health 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, SH; Song, MK. Advancements and challenges in next-generation mRNA vaccine manufacturing systems. Clin Exp Vaccine Res 2025, 14, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengelbrock, A; Schmidt, A; Helgers, H; Vetter, FL; Strube, J. Scalable mRNA Machine for Regulatory Approval of Variable Scale between 1000 Clinical Doses to 10 Million Manufacturing Scale Doses. Processes 2023, 11, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, SJ; Han, X; Mukalel, AJ; El-Mayta, R; Thatte, AS; Wu, J; et al. Throughput-scalable manufacturing of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA lipid nanoparticle vaccines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, J; Zwolinski, C; Denis, C; Maughan, M; Hayles, L; Clarke, D; et al. Development of mRNA manufacturing for vaccines and therapeutics: mRNA platform requirements and development of a scalable production process to support early phase clinical trials. Translational Research 2022, 242, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S; Basu, M; Chakraborty, D; Ghosh, P; Ghosh, MK. Unraveling COVID-19 Diagnostics: A Roadmap for Future Pandemic. Nature Cell and Science 2024, 000, 000–000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazzaoui, A; Abdellatif, AAH; Al-Allaf, FA; Bogari, NM; Al-Dehlawi, S; Qari, SH. Strategies for Vaccination: Conventional Vaccine Approaches Versus New-Generation Strategies in Combination with Adjuvants. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gote, V; Bolla, PK; Kommineni, N; Butreddy, A; Nukala, PK; Palakurthi, SS; et al. A Comprehensive Review of mRNA Vaccines. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, I; de Puig, H; Hiley, M; Carré-Camps, M; Perdomo-Celis, F; Narváez, CF; et al. Rapid antigen tests for dengue virus serotypes and Zika virus in patient serum. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffaf, T; Ghafar-Zadeh, E. COVID-19 Diagnostic Strategies Part II: Protein-Based Technologies. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, MN; de Oliveira Coelho, B; Góes, LGB; Minoprio, P; Durigon, EL; Morello, LG; et al. Colorimetric RT-LAMP SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic sensitivity relies on color interpretation and viral load. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 9026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X; Coulter, FJ; Yang, M; Smith, JL; Tafesse, FG; Messer, WB; et al. A lyophilized colorimetric RT-LAMP test kit for rapid, low-cost, at-home molecular testing of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atmar, RL; Ramani, S. Immunologic Detection and Characterization. Viral Infections of Humans; Springer US: New York, NY, 2022; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafabadi, ZY; Fanuel, S; Falak, R; Kaboli, S; Kardar, GA. The Trend of CRISPR-Based Technologies in COVID-19 Disease: Beyond Genome Editing. Mol Biotechnol 2023, 65, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X; Qi, J; Wang, J; Hu, W; Zhou, W; Wang, Y; et al. Nanoparticle technology for mRNA: Delivery strategy, clinical application and developmental landscape. Theranostics 2024, 14, 738–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, I; Roy, P. Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine candidate appears safe and effective. The Lancet 2021, 397, 642–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramod, S; Govindan, D; Ramasubramani, P; Kar, SS; Aggarwal, R; Manoharan, N; et al. Effectiveness of Covishield vaccine in preventing Covid-19 – A test-negative case-control study. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3294–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name of company | Country | Product | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenScript USA Inc. | USA | Rapid antigen test | Gold-coated antibodies produce colorimetric signal on paper in presence of target serum | [191,192] |

| Abbot Diagnostics | USA | RT-LAMP | Assay amplifies target regions of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and N gene with the same fluorophore within a single well. | [193,194] |

| Bio-Rad Laboratories DRG Diagnostics GmbH Euroimmun US Inc. |

USA | ELISA | Viral antigens are immobilized on plate to catch antibodies from patient’s antibodies | [192,195] |

| Mammoth Biosciences/ Sherlock Biosciences | USA | CRISPR | Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 | [196] |

| Identify Sensors | USA | Check 4 | Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 |

www.statnano.com |

| NanoEnTek | South Korea | Frend COVID-19 Ag | Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| Zepto Life Technology | USA | COVID-19 Test | Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| Mologic Ltd | UK | COVIS-19 test | Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| Lucence Diagnostics Pte Ltd. | Singapore | SAFER Sample Kit | Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| Graphene Leaders Canada | Canada | GLCM Biosensor test | Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| Nanoshel | India | Hand Sanitizer | Anti-viral | |

| Curran Biotech | USA | Filter | Capture coating | |

| Medicevo Corporation | India | Face mask with graphene | Virus control and personal protection | |

| Flextrapower | USA | Graphene mask | Virus control and personal protection | |

| Integricote | USA | Respiratory mask | Virus control and personal protection | |

| Master Dynamic Limited | China | Diamond face mask | Virus removal | |

| Yamashin Filter Corp | Japan | Nanofiber mask | Virus removal | |

| MVX Prime Ltd. | UK | Nano mask | Anti-viral Anti-bacterial |

| Name of the company | Name of the vaccine | Adult dosage (www.who.int) |

Ingredients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biontech/Pfizer (USA) |

BNT162b2 | 2 doses of 30µg each Intramuscularly |

Nucleoside-modified mRNA encoding the viral spike (S) glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 [145], DSPC, cholesterol, ALC-0315, ALC-0159 [197] |

| Moderna (USA) |

mRNA-1273 | 2 doses of 50µg each Intramuscularly |

Nucleoside-modified mRNA encoding the viral spike (S) glycoprotein , DSPC, cholesterol, SM102, DMG-PEG2000 [197] |

| Novavax (India) |

NVX-CoV2337 | 2 doses of 0.5 ml each Intramuscularly |

SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein [135] |

| J&J/Janssen (USA) |

Ad26.CoV2.S | 1 dose of 0.5 ml each Intramuscularly |

Recombinant, replication-incompetent Ad26 vector, encoding a stabilized variant of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein. [121] |

| Sinovac (China) |

Coronavac | 2 doses of 0.5 ml each Intramuscularly |

Aluminum hydroxide–adjuvanted, inactivated whole-virus vaccine [133] |

| Gamaleya (Russia) |

Sputnik V | 2 doses of 0.5 ml each Intramuscularly |

Recombinant, replication-incompetent Ad26 vector, encoding a stabilized variant of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein. [198] |

| Bharat Biotech (India) |

Covaxin | 2 doses of 0.5 ml each Intramuscularly |

Alhydroxiquim-II–adjuvanted, inactivated whole-virus vaccine [133] |

| Astrazenica (UK) |

Covishield | 2 doses of 0.5 ml each Intramuscularly |

Recombinant, replication-incompetent ChAdOx1 vector, encoding a stabilized variant of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein. [199] |

| Sinopharm (China) |

BBIBP-CorV | 2 doses of 0.5 ml each Intramuscularly |

Aluminum hydroxide–adjuvanted, inactivated whole-virus vaccine [133] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).