Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

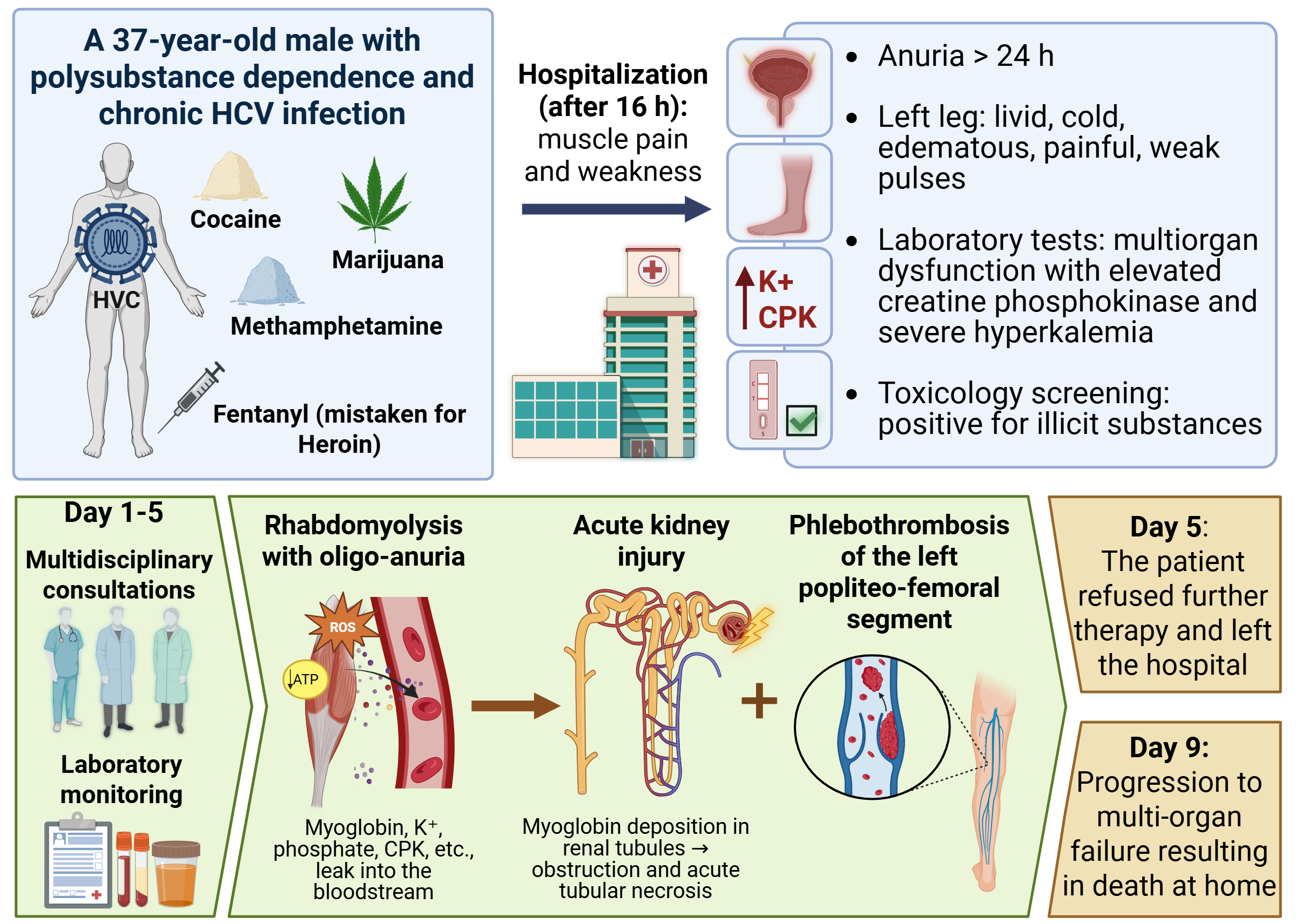

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Medical History

2.2. Physical Examination and Clinical Course

2.3. Toxicological Screening and Laboratory Results

2.4. Diagnosis

2.5. Therapeutic Course

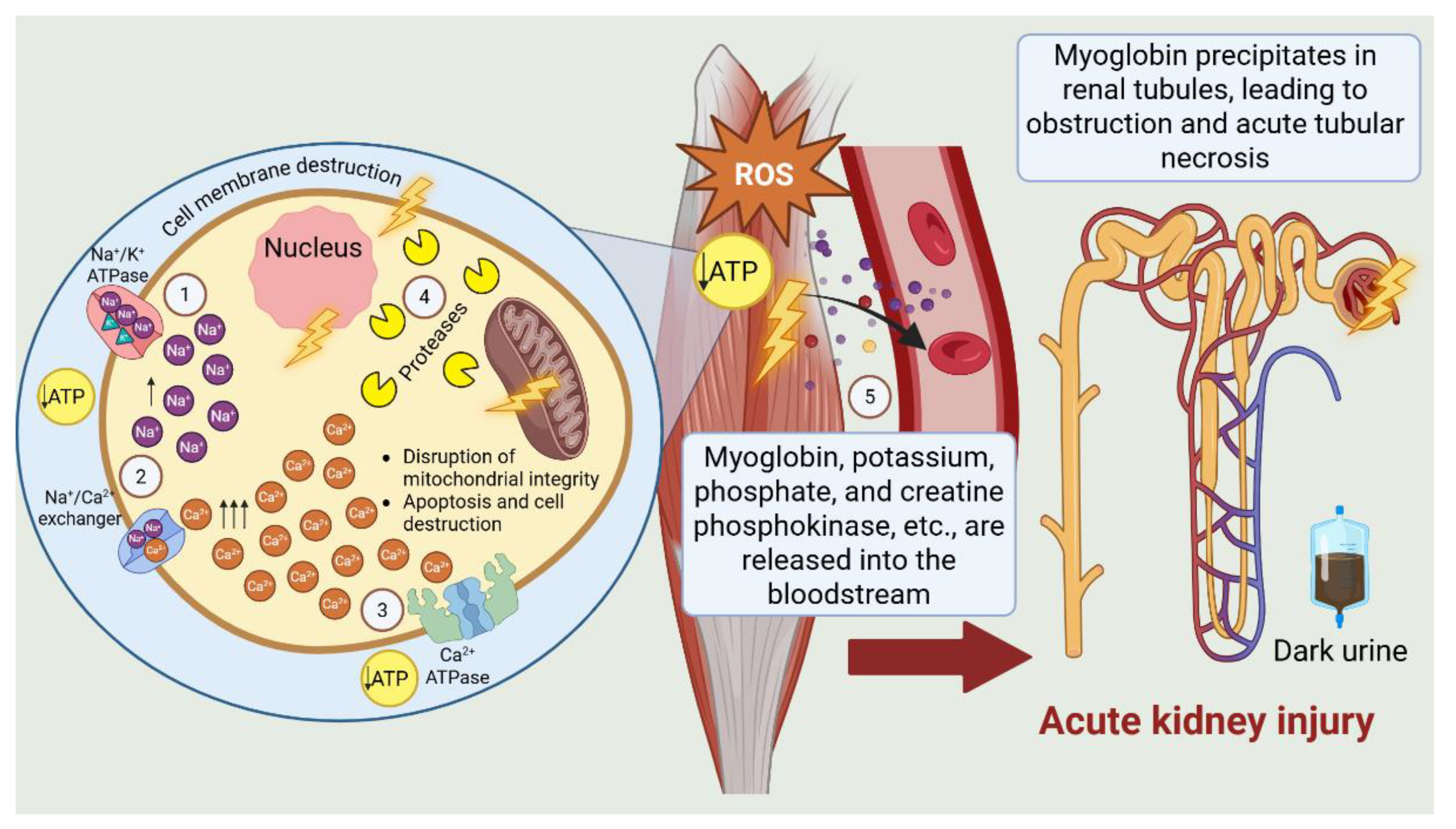

3. Discussion

4. Conslusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| CK | Creatine phosphokinase |

| DVT | Deep vein thrombosis |

| EUDA | European Union Drugs Agency |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

References

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. European Drug Report 2024: Trends and Developments – The Drug Situation in Europe up to 2024; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024; ISBN 978-92-9497-975-9. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/european-drug-report/2024/drug-situation-in-europe-up-to-2024_en.

- World Health Organization. Strengthening Clinical Trials to Provide High-Quality Evidence on Health Interventions and to Improve Research Quality and Coordination: Report by the Director-General; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Document No. A75/43. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA75/A75_43-en.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA). Drug Induced Deaths – The Current Situation in Europe (European Drug Report 2025); EUDA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2025. https://www.euda.europa.eu/publications/european-drug-report/2025/drug%20induced%20deaths_en (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Contemporary Issues on Drugs. Booklet 2, World Drug Report 2025; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Vienna, Austria, 2025. https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/WDR_2025/WDR25_B2_Contemporary_drug_issues.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- National Institutes of Health, HEAL Initiative. Opioid Crisis. National Institutes of Health, 2024. Available online: https://heal.nih.gov/about/opioid-crisis (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Rawy, M.; Abdalla, G.; Look, K. Polysubstance mortality trends in White and Black Americans during the opioid epidemic, 1999–2018. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 112. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.W.; Borron, S.W.; Burns, M.J. Emergency management of poisoning. In Haddad and Winchester’s Clinical Management of Poisoning and Drug Overdose, 4th ed.; Shannon, M.W., Borron, S.W., Burns, M.J., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 13–61. [CrossRef]

- Manjón-Prado, H.; Serrano Santos, E.; Osuna, E. Patterns of polydrug use in patients presenting at the emergency department with acute intoxication. Toxics 2025, 13, 380. [CrossRef]

- Uljon, S. Advances in fentanyl testing. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2023, 116, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Stoeva-Grigorova, S.; Radeva-Ilieva, M.; Karkkeselyan, N.; Dragomanova, S.; Kehayova, G.; Dimitrova, S.; Petrova, M.; Zlateva, S.; Marinov, P. Historical perspectives and emerging trends in fentanyl use: Part 1—Pharmacological profile. Pharmacia 2025, 72, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Stoeva-Grigorova, S.; Hvarchanova, N.; Gancheva, S.; Eftimov, M.; Georgiev, K.D.; Radeva-Ilieva, M. Differentiation of therapeutic and illicit drug use via metabolite profiling. Metabolites 2025, 15, 745. [CrossRef]

- Griswold, M.K.; Chai, P.R.; Krotulski, A.J.; Friscia, M.; Chapman, B.; Boyer, E.W.; Logan, B.K.; Babu, K.M. Self-identification of nonpharmaceutical fentanyl exposure following heroin overdose. Clin. Toxicol. 2018, 56, 37–42. [CrossRef]

- Vanholder, R.; Sever, M.S.; Erek, E.; Lameire, N. Rhabdomyolysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2000, 11, 1553–1561. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, B.M.I.; Edding, S.N.; Portocarrero, J.P.; Lerma, E.V. Rhabdomyolysis. Dis. Mon. 2020, 66, 101015. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.-F.; Li, D.; Liu, C.-L.; Luo, Y.; Shi, J.; Guo, X.-Q.; Fan, H.-J.; Lv, Q. Advances in rhabdomyolysis: A review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2025, S1008-1275(25)00010-0. [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.R. Rhabdomyolysis and drugs of abuse. J. Emerg. Med. 2000, 19, 51–56. [CrossRef]

- Wurcel, A.G.; Merchant, E.A.; Clark, R.P.; Stone, D.R. Emerging and underrecognized complications of illicit drug use. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1840–1849. [CrossRef]

- Alessi, M.R.; Ribas, T.M.; Campelo, V.S.; Mauer, S. Acute cocaine intoxication leading to multisystem dysfunction: A case report. Cureus 2024, 16, e72128. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.M.; Kromm, J.A. Neurological and systemic effects of cocaine toxicity: A case report and review of the literature. Med. Int. (Lond.) 2024, 8, 196. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, S.A.; Mohammed, N.S.; Ali, Z.Q.; Mohamed, A.S. The effects of methamphetamine intoxication on acute kidney injury in Iraqi male addicts. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 102065. [CrossRef]

- Mitaritonno, M.; Lupo, M.; Greco, I.; Mazza, A.; Cervellin, G. Severe rhabdomyolysis induced by co-administration of cocaine and heroin in a 45 years old man treated with rosuvastatin: A case report. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92(S1), e2021089. [CrossRef]

- Sahni, V.; Garg, D.; Garg, S.; Agarwal, S.K.; Singh, N.P. Unusual complications of heroin abuse: Transverse myelitis, rhabdomyolysis, compartment syndrome, and ARF. Clin. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 153–155. [CrossRef]

- Kosmadakis, G.; Michail, O.; Filiopoulos, V.; Papadopoulou, P.; Michail, S. Acute kidney injury due to rhabdomyolysis in narcotic drug users. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2011, 34, 584–588. [CrossRef]

- Alinejad, S.; Ghaemi, K.; Abdollahi, M.; Mehrpour, O. Nephrotoxicity of methadone: A systematic review. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 2087. [CrossRef]

- Babak, K.; Mohammad, A.; Mazaher, G.; Samaneh, A.; Fatemeh, T. Clinical and laboratory findings of rhabdomyolysis in opioid overdose patients in the intensive care unit of a poisoning center in 2014 in Iran. Epidemiol. Health 2017, 39, e2017050. [CrossRef]

- Dobrie, L.; Handa, T.; Sirotkin, I.; Cruz, A.; Konstas, D.; Baldinger, E. Rhabdomyolysis occurring after use of cocaine contaminated with fentanyl causing bilateral brachial plexopathy. Fed. Pract. 2022, 39, 261–265. [CrossRef]

- Pi, M.; Nie, S.; Su, L.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Gao, P.; Lin, Y.; Zha, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Kong, Y.; Li, G.; Hu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wan, Q.; Chen, C.; Liu, B.; Yang, Q.; Su, G.; Zhou, Y.; Weng, J.; Xu, G.; Xu, H.; Tang, Y.; Gong, M.; Hou, F.F.; Xu, X. Risk of Hospital-Acquired Acute Kidney Injury among Adult Opioid Analgesic Users: A Multicenter Real-World Data Analysis. Kidney Dis. 2023, 9, 517–528. [CrossRef]

- Tom, K.; Bzdusek, J. Heroin overdose complicated by compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal failure. Cureus 2024, 16, e61144. [CrossRef]

- Gokul, K.; Hoque, F. Rhabdomyolysis with severe creatine phosphokinase elevation and acute kidney injury: A case report and review of rare causes. APIK J. Intern. Med. 2025, 13, 300–302. [CrossRef]

- Keenum, O.D.; Patel, S.; Balasubramaniam, A.; Bates, W.; Smallwood, D. An unusual presentation of fentanyl-induced rhabdomyolysis. Cureus 2025, 17, e83426. [CrossRef]

- Jullian-Desayes, I.; Roselli, A.; Lamy, C.; Alberto-Gondouin, M.C.; Janvier, N.; Venturi-Maestri, G. Rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure and deep vein thrombosis induced by antipsychotic drugs: A case report. Pharmacopsychiatry 2015, 48, 265–267. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Tan, M.; Aung, M.; Salifu, M.; Mallappallil, M. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury requiring dialysis as a result of concomitant use of atypical neuroleptics and synthetic cannabinoids. Case Rep. Nephrol. 2015, 2015, 235982. [CrossRef]

- Upadrista, P.K.; Peketi, S.H.; Sudireddy, N.; Cadet, B.; Kim, Z. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury: Exploring the potential causes in a hospitalized patient. Cureus 2025, 17, e80535. [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Alardín, A.L.; Varon, J.; Marik, P.E. Bench-to-bedside review: Rhabdomyolysis—An overview for clinicians. Crit. Care 2005, 9, 158–169. [CrossRef]

- Bagley, W.H.; Yang, H.; Shah, K.H. Rhabdomyolysis. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2007, 2, 210–218. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Poch, E.; Grau, J.M. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 62–72. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J.L.; Shen, M.C. Rhabdomyolysis. Chest 2013, 144, 1058–1065. [CrossRef]

- Giannoglou, G.D.; Chatzizisis, Y.S.; Misirli, G. The syndrome of rhabdomyolysis: Pathophysiology and diagnosis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2007, 18, 90–100. [CrossRef]

- Torres, P. A.; Helmstetter, J. A.; Kaye, A. M.; Kaye, A. D. Rhabdomyolysis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Ochsner J. 2015, 15, 58–69.

- Chavez, L.O.; Leon, M.; Einav, S.; Varon, J. Beyond muscle destruction: a systematic review of rhabdomyolysis for clinical practice. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 135. [CrossRef]

- Waldman, W.; Kabata, P.M.; Dines, A.M.; Wood, D.M.; Yates, C.; Heyerdahl, F.; Hovda, K.E.; Giraudon, I.; Euro-DEN Research Group; Dargan, P.I.; Sein, J.A. Rhabdomyolysis related to acute recreational drug toxicity—A Euro-DEN study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246297. [CrossRef]

- Rixey, A.B.; Glazebrook, K.N.; Powell, G.M.; Baffour, F.I.; Collins, M.S.; Takahashi, E.A.; Tiegs-Heiden, C.A. Rhabdomyolysis: a review of imaging features across modalities. Skeletal Radiol. 2024, 53, 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Petejova, N.; Martinek, A. Acute kidney injury due to rhabdomyolysis and renal replacement therapy: a critical review. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 224. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, M.; Dass, B.; Ejaz, A. A. Paradigm shift in the role of uric acid in acute kidney injury. Semin. Nephrol. 2011, 31, 453–458. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P. D.; Clarkson, P.; Karas, R. H. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA 2003, 289, 1681–1690. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Thorson, P.; Penmatsa, K.; Gupta, P. Rhabdomyolysis: Revisited. Ulster Med. J. 2021, 90, 61–69.

- Lau Hing Yim, C.; Wong, E. W. W.; Jellie, L. J.; Lim, A. K. H. Illicit drug use and acute kidney injury in patients admitted to hospital with rhabdomyolysis. Intern. Med. J. 2019, 49, 1285–1292. [CrossRef]

- Kodadek, L.; Carmichael II, S. P.; Seshadri, A.; Pathak, A.; Hoth, J.; Appelbaum, R.; Michetti, C. P.; Gonzalez, R. P. Rhabdomyolysis: an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Critical Care Committee Clinical Consensus Document. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2022, 7, e000836. [CrossRef]

- Neves Pinto, G.; Campelo Fraga, Y.; De Francesco Daher, E.; Bezerra da Silva Junior, G. Acute Kidney Injury Due to Rhabdomyolysis: A Review of Pathophysiology, Causes, and Cases Reported in the Literature, 2011–2021. Rev. Colomb. Nefrol. 2023, 10, e619. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm-Leen, E. R.; Winkelmayer, W. C. Predicting the outcomes of rhabdomyolysis: a good starting point. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1828–1829. [CrossRef]

- Welte, T.; Bohnert, M.; Pollak, S. Prevalence of rhabdomyolysis in drug deaths. Forensic Sci. Int. 2004, 139, 21–25. [CrossRef]

- Larbi, E. B. Drug induced rhabdomyolysis: case report. East Afr. Med. J. 1997, 74, 829–831.

- Rodríguez, E.; Soler, M.J.; Rap, O.; Barrios, C.; Orfila, M.A.; Pascual, J. Risk factors for acute kidney injury in severe rhabdomyolysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82992. [CrossRef]

- Amanollahi, A.; Babeveynezhad, T.; Sedighi, M.; Shadnia, S.; Akbari, S.; Taheri, M.; Besharatpour, M.; Jorjani, G.; Salehian, E.; Etemad, K.; Mehrabi, Y. Incidence of rhabdomyolysis occurrence in psychoactive substances intoxication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17693. [CrossRef]

- Eghbali, F.; Owliaey, H.; Shirani, S.; Fatahi Asl, F.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Deravi, N.; Ghasemirad, H.; Shariatpanahi, M.; Farajidana, H. Rhabdomyolysis in patients with drug or chemical poisoning: clinical investigation and implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 50, 455–463. [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, K.; Kheetan, M.; Shahnawaz, S.; Shapiro, A.P.; Patton-Tackett, E.; Dial, L.; Rankin, G.; Santhanam, P.; Tzamaloukas, A.H.; Nadasdy, T.; Shapiro, J.I.; Khitan, Z.J. Systematic review of nephrotoxicity of drugs of abuse, 2005–2016. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 379. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Chávez, A.; Carrion, J.A.; Forns, X.; Ramos-Casals, M. Extrahepatic manifestations associated with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2017, 19, 87–97. [CrossRef]

- Kanters, C.T.M.M.; van Luin, M.; Solas, C.; Burger, D.M.; Vrolijk, J.M. Rhabdomyolysis in a hepatitis C virus-infected patient treated with telaprevir and simvastatin. Ann. Hepatol. 2014, 13, 452–455. [CrossRef]

- Qatomah, A.; Bukhari, M.; Cupler, E.; Alardati, H.; Mawardi, M. Acute reversible rhabdomyolysis during direct-acting antiviral hepatitis C virus treatment: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 627. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Goel, A.; Mishra, N. Rhabdomyolysis: Heroin induced or HCV related. Indian J. Med. Specialties 2016, 7(4), 174–176. [CrossRef]

- Jensenius, M.; Holm, B.; Calisch, T.E.; Haugen, K.; Sandset, P.M. Dyp venetrombose hos intravenøse stoffmisbrukere [Deep venous thrombosis in intravenous drug addicts]. Tidsskr. Nor. Lægeforen. 1996, 116(21), 2556–2558. Iellin, A.E.; Frankhouse, J.H.; Weaver, F.A. Vascular injury secondary to drug abuse. In Current Therapy in Vascular Surgery, 3rd ed.; Ernst, C.B., Stanley, J.C., Eds.; Mosby: St Louis, MO, USA, 1995; pp. 637–644.

- Pieper, B.; Kirsner, R.S.; Templin, T.N.; Birk, T.J. Injection drug use: an understudied cause of venous disease. Arch. Dermatol. 2007, 143(10), 1305–1309. [CrossRef]

- Pieper, B. Nonviral Injection-Related Injuries in Persons Who Inject Drugs: Skin and Soft Tissue Infection, Vascular Damage, and Wounds. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2019, 32(7), 301–310. [CrossRef]

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) – Symptoms & causes. Mayo Clinic, 11 June 2022. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/deep-vein-thrombosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20352557 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Stark, K.; Massberg, S. Interplay between inflammation and thrombosis in cardiovascular pathology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 666–682. [CrossRef]

- Murillo Solera, A.; Diaz, J.A. The Critical Role of Inflammation in Deep Vein Thrombosis. Endovasc. Today 2024, July Issue. Available online: https://evtoday.com/articles/2024-july/the-critical-role-of-inflammation-in-deep-vein-thrombosis (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Schulman, S.; Makatsariya, A.; Khizroeva, J.; Bitsadze, V.; Kapanadze, D. The Basic Principles of Pathophysiology of Venous Thrombosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11447. [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Anjum, F.; dela Cruz, J. Deep Venous Thrombosis Ultrasound Evaluation. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Updated 8 August 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470453/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Arnoldussen, C.W.K.P. Imaging of Deep Venous Pathology. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 47(12), 1580–1594. [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, S.A.; Kielstein, J.T.; Lukasz, A.; Sorrentino, J.N.; Gohrbandt, B.; Haller, H.; Schmidt, B.M. High permeability dialysis membrane allows effective removal of myoglobin in acute kidney injury resulting from rhabdomyolysis. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 184–186.

- Sever, M.S.; Vanholder, R.; RDRTF of ISN Work Group on Recommendations for the Management of Crush Victims in Mass Disasters. Recommendation for the management of crush victims in mass disasters. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012, 27 Suppl 1, i1–i67. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.V.; Rhee, P.; Chan, L.; Evans, K.; Demetriades, D.; Velmahos, G.C. Preventing renal failure in patients with rhabdomyolysis: do bicarbonate and mannitol make a difference? J. Trauma 2004, 56, 1191–1196. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.R.; Shapiro, S.; Wells, P.S.; Rodger, M.A.; Kovacs, M.J.; Anderson, D.R.; Tagalakis, V.; Houweling, A.H.; Ducruet, T.; Holcroft, C.; Johri, M.; Solymoss, S.; Miron, M.-J.; Yeo, E.; Smith, R.; Schulman, S.; Kassis, J.; Kearon, C.; Chagnon, I.; Wong, T.; Demers, C.; Hanmiah, R.; Kaatz, S.; Selby, R.; Rathbun, S.; Desmarais, S.; Opatrny, L.; Ortel, T.L.; Ginsberg, J.S.; SOX Trial Investigators. Compression stockings to prevent post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 880–888. [CrossRef]

- Appelen, D.; van Loo, E.; Prins, M.H.; Neumann, M.H.; Kolbach, D.N. Compression therapy for prevention of post-thrombotic syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD004174. [CrossRef]

- Ortel, T.L.; Neumann, I.; Ageno, W.; Beyth, R.; Clark, N.P.; Cuker, A.; Hutten, B.A.; Jaff, M.R.; Manja, V.; Schulman, S.; et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 Guidelines for Management of Venous Thromboembolism: Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 4693–4738. [CrossRef]

- Palareti, G.; Santagata, D.; De Ponti, C.; Ageno, W.; Prandoni, P. Anticoagulation and compression therapy for proximal acute deep vein thrombosis. VASA. Zeitschrift für Gefasskrankheiten 2024, 53, 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.M.; Woller, S.C.; Baumann Kreuziger, L.; Doerschug, K.; Geersing, G.J.; Klok, F.A.; King, C.S.; Murin, S.; Vintch, J.R.E.; Wells, P.S.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: Compendium and Review of CHEST Guidelines 2012–2021. Chest 2024, S0012-3692(24)00292-7. [CrossRef]

- Ziyadeh, F.; Mauer, Y. Management of Lower Extremity Venous Thromboembolism: An Updated Review. Cleveland Clin. J. Med. 2024, 91, 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Varacallo, M.A. Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin (LMWH) [Updated 2025 Mar 28]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525957/.

- Gaudry, S.; Grolleau, F.; Barbar, S.; Martin-Lefevre, L.; Pons, B.; Boulet, É.; Boyer, A.; Chevrel, G.; Montini, F.; Bohe, J.; et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy versus intermittent hemodialysis as first modality for renal replacement therapy in severe acute kidney injury: a secondary analysis of AKIKI and IDEAL-ICU studies. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 93. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz Aydın, F.; Aydın, E.; Kadiroglu, A.K. Comparison of the Treatment Efficacy of Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy and Intermittent Hemodialysis in Patients With Acute Kidney Injury Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Cureus 2022, 14, e21707. [CrossRef]

- Chander, S.; Luhana, S.; Sadarat, F.; et al. Mortality and mode of dialysis: meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 1. [CrossRef]

- Racheva, R. Attention as a Factor Related to Addictions to Psychoactive Substances. Bulgarian J. Public Health 2025, 17, 30–39.

- Maina, G.; Ogenchuk, M.; Phaneuf, T.; Kwame, A. “I can’t live like that”: the experience of caregiver stress of caring for a relative with substance use disorder. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2021, 16, 11. [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, M.; Ćavar, I.; Jurišić, D.; Jelinčić, I.; Degmečić, D. Burden and Psychological Distress in Caregivers of Persons with Addictions. Challenges 2023, 14, 24. [CrossRef]

- Tyo, M.B.; McCurry, M.K.; Horowitz, J.A.; Elliott, K. Perceived Stressors and Support in Family Caregivers of Individuals With Opioid Use Disorder. J. Addict. Nurs. 2023, 34, E136–E144. [CrossRef]

- Soellner, R.; Hofheinz, C. Burden and satisfaction with social support in families with a history of problematic substance use or dementia – a comparison. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 448. [CrossRef]

| Category of Effects | Types |

|---|---|

| Acute Effects | ⋅ Intoxication, accidental poisoning, and overdose leading to hospitalization ⋅ Psychiatric manifestations: anxiety, psychosis, paranoia, acute cognitive impairment ⋅ Accidents, injuries, or traffic incidents secondary to psychomotor impairment |

| Chronic Effects | ⋅ Medical (somatic) morbidity: infectious, pulmonary, metabolic, cardiovascular, and oncological diseases ⋅ Poor nutrition and hygiene associated with chaotic lifestyle, increasing risk for somatic health problems ⋅ Psychiatric comorbidity resulting from or exacerbated by substance use |

| Day | Clinical Course |

| Day 1 | ⋅ The patient remained hemodynamically stable, afebrile, alert, and oriented, with persistent pain and edema of the left lower limb. ⋅ Following urethral catheterization, approximately 200 mL of dark-colored urine, resembling tea, was produced. ⋅ Urine toxicology screening was positive for psychoactive substances. ⋅ Serial examinations revealed a livid, markedly edematous, tense, and cool left lower limb with diminished to absent peripheral pulses (+3 cm circumference increase compared to the contralateral limb). ⋅ Electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus tachycardia with nonspecific repolarization changes. ⋅ Laboratory findings indicated massive enzymatic release and early signs of multiorgan dysfunction. ⋅ Cardiological, internal medicine, and surgical consultations were obtained, recommending Doppler ultrasonography and additional vascular assessment. Anticoagulant and symptomatic therapy were initiated. ⋅ Severe hyperkalemia (K⁺ 8.4 mmol/L) was corrected emergently with pharmacological intervention, diuretics, analgesics, and intensive laboratory monitoring. ⋅ Pain and edema persisted without significant change in vascular status by the end of the day. |

| Day 2 | ⋅ No substantial change in overall condition was noted. The patient remained afebrile, alert, and oriented, with persistent pain and cold edema of the left lower leg, along with generalized edema of the limbs and face. ⋅ Urine output remained severely reduced (oligo-anuria), totaling approximately 200–400 mL in 24 hours despite a markedly positive fluid balance. Intensive diuretic and vasoactive therapy was administered without significant effect. ⋅ Hemodynamics were relatively stable with a tendency toward hypertension. ⋅ Respiratory status was stable, with no clinical or laboratory evidence of respiratory failure. ⋅ Laboratory results indicated severe renal impairment (eGFR ≈ 24 mL/min/1.73 m²) in the context of ongoing multisystem dysfunction. ⋅ Extended laboratory tests and consultations with cardiology, nephrology, and vascular surgery were planned for diagnostic clarification and therapeutic planning. |

| Day 3 | ⋅ The patient spent the night relatively calmly, remaining alert, oriented, and afebrile, with persistent left lower limb pain and generalized edema. ⋅ Severe oligo-anuria persisted (≈200 mL of dark urine in 24 hours) despite intensive diuretic and pharmacologic stimulation. Nephrology assessment confirmed acute kidney injury in the context of acute renal failure. ⋅ Hemodynamic and respiratory status remained stable, with a tendency toward hypertension. ⋅ Vascular surgery consultation revealed tense subfascial edema of the entire left lower limb, neurological deficits in the toes, and reduced active movements. Doppler imaging demonstrated thrombosis of the left popliteo-femoral segment without signs of acute arterial occlusion. ⋅ Progression to complete anuria was noted. Infusion therapy with vasoactive and diuretic agents was continued without significant clinical effect. ⋅ Overall condition remained stable, with persistent renal dysfunction, edema, and local vascular complications. ⋅ Extended laboratory monitoring and multidisciplinary consultations were planned. |

| Day 4 | ⋅ The patient remained calm, alert, and oriented, with persistent generalized edema of the face, hands, and feet. ⋅ Severe anuria persisted (≈100 mL/24 h with 900 mL fluid infusion). Renal stimulation therapy with dopamine, furosemide, and novofilin was continued. ⋅ Despite persistent edema, the patient reported reduced pain, allowing ambulation, without new subjective complaints. ⋅ Hemodynamically, the patient remained relatively stable (BP 125–140/68–100 mmHg, HR 76–90 bpm). Spontaneous breathing and oxygen saturation (95–96%) were normal. Pulmonary and abdominal examinations revealed no pathological findings. ⋅ In the evening, the patient remained alert, with mild agitation, reporting urethral pain and hematochezia. |

| Day 5 | ⋅ The patient remained afebrile, with persistent pain in the leg and generalized body pain. The patient was alert, oriented, and cooperative; however, despite institutional restrictions, smoking was observed in the intensive care unit. ⋅ Urine output was markedly reduced (≈100 mL/24 h). ⋅ Vesicular breathing was clear. Generalized edema persisted, most pronounced in the left lower limb. Blood pressure remained elevated (up to 175/110 mmHg); symptomatic antihypertensive therapy (chlofazoline) was administered. ⋅ The patient underwent hemodialysis without complications. ⋅ Later in the day, he decisively refused continued hospital treatment. He was informed of health and life risks and discharged with accompaniment by his mother. |

| Day 6 | ⋅ The patient returned to the clinic, accompanied by family insistence. He was informed in detail of the necessity for urgent dialysis and potential complications of treatment refusal. Despite this, he again refused therapy, demonstrating verbal aggression and demanding removal of venous access and urethral catheter. In the presence of on-duty staff and the head of the clinic, he signed a written refusal of treatment. Immediate life-threatening risks were repeatedly explained. The patient was discharged per his insistence with a medical report including recommendations for follow-up and monitoring. |

| Day 9 | ⋅ The patient died at home following a continued refusal of urgent therapy and hospital treatment. |

| Substance | Cut-Off (Urine, ng/mL) |

Cut-Off (Plasma, ng/mL) |

Result from the analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | Plasma | |||

| Amphetamine | 1000 | 80 | – | – |

| Cocaine (Benzoylecgonine) | 300 | 50 | + | + |

| Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol metabolite (Marijuana) | 50 | 35 | + | + |

| Benzodiazepines | 300 | 100 | – | – |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants | 1000 | 100 | – | – |

| Barbiturates | 300 | 100 | – | – |

| Morphine (Opiates) | 300 | 40 | – | – |

| Methadone | 300 | 40 | – | – |

| Methamphetamine | 1000 | 70 | + | + |

| 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine | 500 | 50 | – | – |

| Fentanyl | 20 | 15 | + | – |

| Parameter | Reference Range | Day 01 | Day 02 | Day 03 | Day 04 | Day 05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Blood Count | ||||||

| ESR [mm/h] | <20 | 27.0 | – | – | – | – |

| Hemoglobin [g/L] | 130–180 | 164.0 | – | – | 126.0 | 106.0 |

| Erythrocytes [x10¹²/L] | 4.8–6.2 | 5.53 | – | – | 4.2 | 3.51 |

| Hematocrit [L/L] | 0.35–0.55 | 0.50 | – | – | 0.37 | 0.308 |

| Leukocytes [x10⁹/L] | 3.5–10.5 | 22.21 | – | – | 14.31 | 11.1 |

| St [%] | 1–6 | 87.9 | – | – | 85.8 | 81.1 |

| Eosinophils [%] | 1.5–8 | 0.0 | – | – | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Basophils [%] | <1 | 0.01 | – | – | 0.01 | 0.0 |

| Lymphocytes [%] | 22–50 | 6.3 | – | – | 7.2 | 12.2 |

| Monocytes [%] | 2–10 | 5.7 | – | – | 5.8 | 5.7 |

| MCV [fL] | 82–100 | 90.4 | – | – | 88.1 | 87.7 |

| MCH [pg] | 28–32 | 29.7 | – | – | 30.0 | 30.2 |

| MCHC [g/L] | 300–360 | 328.0 | – | – | 341.0 | 344.0 |

| RDW [%] | 11.5–14.9 | 14.2 | – | – | 14.3 | 14.4 |

| Platelets [x10⁹/L] | 140–440 | 316.0 | – | – | 170.0 | 136.0 |

| MPV [fL] | 8.8–12.5 | 10.8 | – | – | 10.9 | 11.3 |

| NRBC [x10⁹/L] | <0.01 | 0.01 | – | – | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| NRBC [%] | 0 | 0.0 | – | – | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Immature Granulocytes [x10⁹/L] | <0.3 | 0.18 | – | – | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| IG [%] | <4 | 0.8 | – | – | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Neutrophils [x10⁹/L] | 2.4–6.9 | 19.52 | – | – | 12.27 | 9.01 |

| Lymphocytes [x10⁹/L] | 0.8–3.4 | 1.39 | – | – | 1.03 | 1.35 |

| Monocytes [x10⁹/L] | 0.4–1.0 | 1.27 | – | – | 0.98 | 0.74 |

| Biochemistry | ||||||

| Total Bilirubin [μmol/L] | 5–21 | 7.17 | – | – | 5.31 | 7.8 |

| Direct Bilirubin [μmol/L] | <5.13 | – | – | – | 2.36 | 1.77 |

| AST [U/L] | <35 | 2501.8 | – | – | 2588.8 | 2876.68 |

| ALT [U/L] | <50 | 619.4 | – | – | 826.6 | 887.66 |

| GGT [U/L] | <55 | 32.0 | – | – | 16.3 | 21.68 |

| α-Amylase [U/L] | 28–100 | 1472.7 | – | – | 440.6 | 267.66 |

| Albumin [g/L] | 35–53 | – | – | – | 29.5 | 28.92 |

| CRP [mg/L] | <5 | 14.41 | – | – | 53.08 | 31.02 |

| Creatine Kinase [U/L] | 24–180 | 63,444.0 | – | – | 55,050.0 | 161,050.0 |

| Blood Glucose [mmol/L] | 4.1–5.9 | 5.18 | – | – | 5.66 | 5.27 |

| Urea [mmol/L] | 2.8–7.2 | 10.66 | – | – | 24.05 | 33.35 |

| Creatinine [μmol/L] | 64–104 | 260.1 | – | – | 605.2 | 737.0 |

| Sodium [mmol/L] | 135–150 | 133.0 | 130.0 | 128.0 | 127.0 | 126.0 |

| Potassium [mmol/L] | 3.5–5.5 | 8.4 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.0 |

| Chloride [mmol/L] | 96–106 | 100.4 | 98.9 | 99.0 | 98.0 | 97.0 |

| Total Protein [g/L] | 60–83 | – | – | – | 53.9 | 53.12 |

| CK-MB [U/L] | <24 | 8576.8 | – | – | 2188.9 | 2360.0 |

| Urinalysis | ||||||

| pH | 4.5–8.0 | – | – | – | 5.5 | – |

| Specific Gravity | 1.010–1.030 | – | – | – | 1.030 | – |

| Protein [g/L] | 0 | – | – | – | 3+ | – |

| Bilirubin | Negative | – | – | – | Negative | – |

| Urobilinogen [μmol/L] | 0–17 | – | – | – | Normal | – |

| Sediment [/μL] | RBC 0–3; WBC 0–5 | – | – | – | RBC 34; WBC 32; BACT 13; SQEP 5; UNCC 3 | – |

| Glucose (urine dipstick) | Negative | – | – | – | 1+ | – |

| Ketones (urine dipstick) [mmol/L] | Negative | – | – | – | Negative | – |

| Nitrites [μmol/L] | Negative | – | – | – | Negative | – |

| Leukocytes (urine dipstick) | 0–5 | – | – | – | 1+ | – |

| Blood in urine | Negative | – | – | – | 1+ | – |

| Immunology | ||||||

| Troponin I [ng/L] | <14 | 10,375.3 | – | – | – | 2,094.66 |

| Arterial Blood Gas – Capillary | ||||||

| BE (ecf) [mmol/L] | ±3 | 1.2 | – | – | –12.8 | –11.6 |

| HCO₃ act [mmol/L] | 22–26 | 22.1 | – | – | 12.9 | 14.1 |

| HCO₃ stat [mmol/L] | 22–26 | 19.8 | – | – | 17.0 | 17.6 |

| O₂ Sat [%] | 95–100 | 94.6 | – | – | 84.7 | 83.8 |

| pCO₂ [kPa] | 4.7–6.0 | 5.6 | – | – | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| pH | 7.35–7.45 | 7.354 | – | – | 7.34 | 7.34 |

| pO₂ [kPa] | 10–13 | 11.2 | – | – | 6.7 | 6.6 |

| tCO₂ [mmol/L] | 22–29 | 24.5 | – | – | 13.5 | 14.8 |

| Lactate [mmol/L] | 0.5–2.2 | – | – | – | 1.4315 | 0.4666 |

| Hemostasis | ||||||

| Prothrombin Time [sec] | 11.8–15 | 21.45 | – | 16.12 | – | 15.89 |

| Prothrombin Activity [%] | 80–120 | 49.22 | – | – | 73.92 | 68.94 |

| aPTT [sec] | 26–38.4 | – | – | – | – | 36.37 |

| INR | 0.7–1.1 | 1.73 | – | – | 1.26 | 1.33 |

| D-dimer [μg/mL] | <0.5 | – | – | – | 2.97 | 2.13 |

| Coagulation Screening | ||||||

| Bleeding Time [sec] | 60–180 | 90 | – | – | – | – |

| Clotting Time [sec] | 130–300 | 210 | – | – | – | – |

| Day | Therapeutic Goal | Treatment | Dose and Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IV hydration & electrolyte balance | Sodium chloride 0.9% Ringer lactate Glucose 5% |

500 mL i.v., 2–4×/day 500 mL i.v., 2–4×/day 500 mL i.v., 4×/day |

| Parenteral nutrition | Lipid emulsion | 500 mL i.v., 1 bag over 6 h, as needed | |

| Neurometabolic & vitamin therapy | Piracetam Thiamine Pyridoxine Cyanocobalamin |

1 g i.v., 2×/day 3×/day i.v. 3×/day i.v. 1 mg i.m., 1×/day |

|

| Electrolyte correction | Magnesium / Calcium aspartate | 1 amp i.v., 1×/day | |

| Anxiolytic/psychotropic therapy | Diazepam Haloperidol |

As needed i.v. | |

| Anticonvulsant therapy | Carbamazepine | 200 mg p.o., 3×/day | |

| Anticoagulant prophylaxis | Enoxaparin | 0.4 mL s.c., 2×/day | |

| Antibacterial therapy | Ceftriaxone | 2 g i.v. | |

| Metabolic & antioxidant therapy | S-adenosylmethionine | 2×1 amp i.v. | |

| Diuretic therapy | Furosemide | 1 amp i.v., as needed | |

| Anti-inflammatory therapy | Dexamethasone | 4 mg i.v., 2×/day | |

| 2 | Diuretic & renal support | Furosemide | 2 amp i.v., bolus |

| Metabolic/electrolyte correction | Insulin Actrapid + Glucose 10% + Sodium bicarbonate + Calcium gluconate | 8E Insulin Actrapid in Glucose 10% 500 mL + 1 amp Sodium bicarbonate + 1 amp Calcium gluconate, 2–3 h i.v. infusion | |

| Hemodynamic & renal support | Dopamine + Theophylline + Furosemide | Continuous infusion via perfusor | |

| Anticoagulant therapy | Enoxaparin | 0.6 mL s.c., 1×/day | |

| Venous circulation | Diosmin / Hesperidin | 2×/day orally | |

| Local thrombosis prophylaxis | Heparinoid ointment | 100 IU/mg, topical | |

| Analgesia | Paracetamol | 1 fl. i.v. | |

| 3 | Diuretic & renal support | Furosemide | 5–15 amp i.v. + continuous infusion 15 mL/h |

| Hemodynamic & renal support | Dopamine + Theophylline | Continuous infusion via perfusor | |

| Neurometabolic & vitamin therapy | Piracetam Thiamine Pyridoxine |

1 g i.v., 2×/day 2×/day i.v. 2×/day i.v. |

|

| Gastroprotection | Pantoprazole | 2×/day i.v. | |

| Antibacterial therapy | Ceftriaxone | 2 g i.v. | |

| Analgesia | Analgin | As needed i.v. | |

| Anticoagulant prophylaxis | Enoxaparin | 0.4 mL s.c., 2×/day | |

| Venous circulation | Diosmin/Hesperidin | 2×2 tablets/day | |

| 4 | Diuretic & renal support | Furosemide | i.v., 10× |

| Hemodynamic & renal support | Dopamine Theophylline |

1×/day i.v. 1/2 amp i.v., 5×/day |

|

| Correction of metabolic acidosis | Sodium bicarbonate | i.v., 2×/day | |

| 5 | IV hydration & electrolytes | Sodium chloride 0.9% | 100 mL i.v., 2×/day |

| Metabolic & renal support | Insulin Actrapid + Glucose 10% + Sodium bicarbonate + Calcium gluconate | 8E Insulin Actrapid in Glucose 10% 500 mL + 1 amp Sodium bicarbonate + 1 amp Calcium gluconate, 2–3 h i.v. infusion | |

| Hemodynamic & renal support | Dopamine + Theophylline + Furosemide | Continuous infusion via perfusor | |

| Neurometabolic & vitamin therapy | Piracetam Thiamine Pyridoxine |

1 g i.v., 2×/day 2×/day i.v. 2×/day i.v. |

|

| Gastroprotection | Pantoprazole | 2×/day i.v. | |

| Antibacterial therapy | Ceftriaxone | 2 g i.v. | |

| Anticoagulant prophylaxis | Enoxaparin | 0.4 mL s.c., 2×/day | |

| Hypertension control | Clonidine | 0.15 mg, tablets | |

| Renal support | Hemodialysis | – |

| Source | Study design | Number of patients with rhabdomyolysis due to substance use | Rhabdomyolysis (%) by substance | Fatality (%) by substance |

| Welte T. (2004) [51] | Retrospective forensic study | 103 (drug deaths) | Heroin/other opioids – NR Methadone – NR Cocaine – NR Alcohol – NR Benzodiazepines – NR |

50.5% of fatal drug abuse cases showed confirmed or probable rhabdomyolysis based on the presence of myoglobin in renal tissue (no stratification by substance) |

| Rodríguez E. (2013) [53] | Retrospective cohort | 35 (of 126) | Heroin – 24% Cocaine – 22.4% Other substances – 19.8% Alcohol – 13.5% “Smart drugs” – 5.6% |

NR |

| Lau Hing Yim C. (2019) [47] | Retrospective cohort | 77 (of 643) | NR | NR |

| Waldman W. (2021) [41] | Observational (Euro-DEN) | 468 (of 1,015) | Cocaine – 22.9% Amphetamine – 16.2% Cannabis – 15.8% GHB/GBL – 15.4% Heroin – 14.3% |

NR |

| Amanollahi A. (2023) [54] | Systematic review & meta-analysis | NR | Heroin – 57.2%† Amphetamines – 30.5%† Methamphetamine – 40.3%† MDMA – 19.9%† Cocaine – 26.6%† Tramadol – 17.1%† Methadone – 16.1%† Synthetic cannabinoids – 10.3%† Opioids overall – 8.8%† Ethanol – 3.0%† Methanol – 2.0%† |

NR |

| Eghbali F. (2025) [55] | Cross-sectional clinical | 455 (of 788) | Methadone – 41.5% Benzodiazepines – 10.1% Opium – 6.1% |

Methadone – 5.2% Benzodiazepines – 0.8% Others – NR |

| NR = Not reported; †Substance-specific incidence proportions across studies. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).