Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

16 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

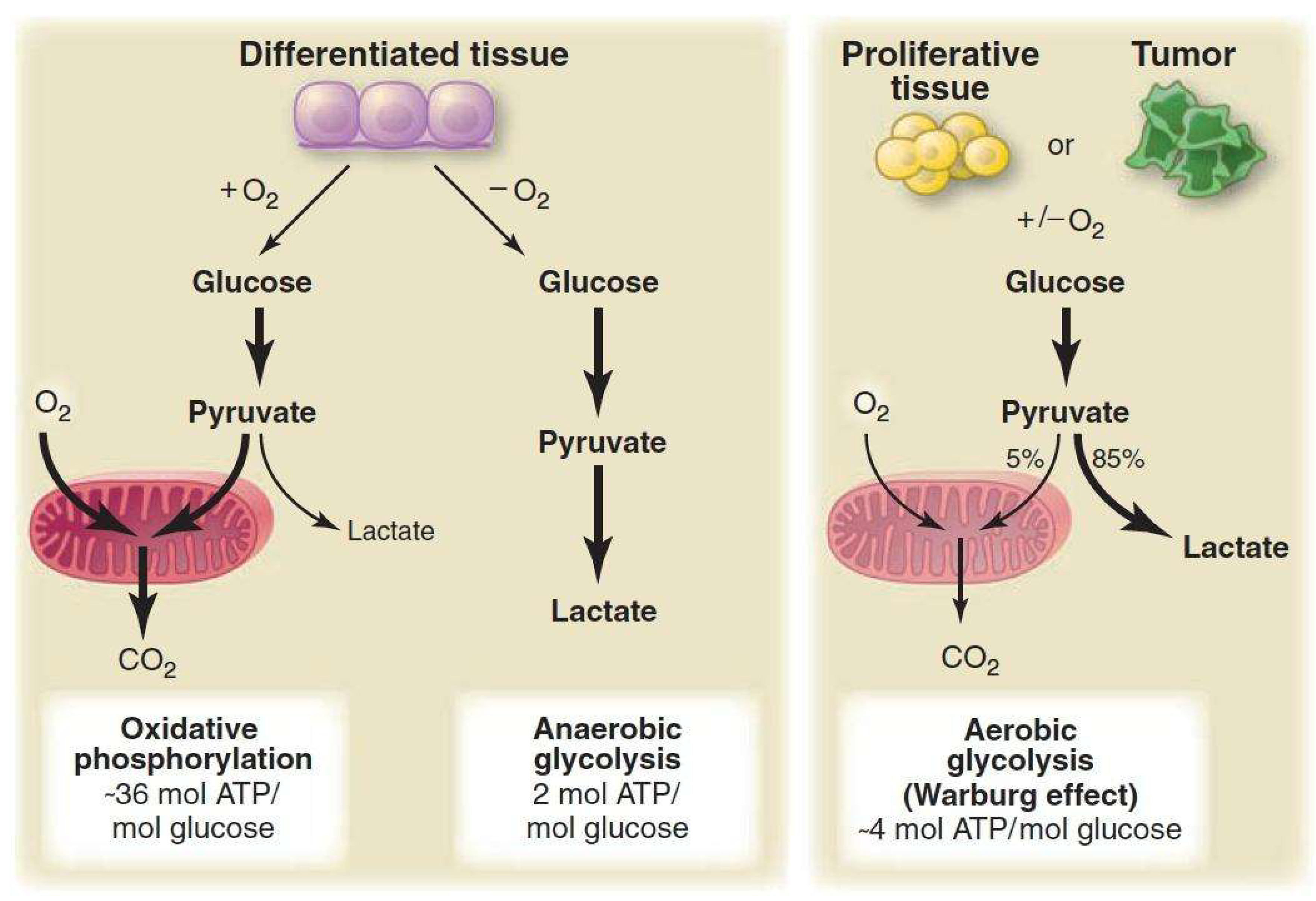

The Warburg effect, classically defined as the preferential use of glycolysis by cancer cells in the presence of oxygen, has been a central concept in cancer biology since a long time. Otto Warburg had originally proposed that defective mitochondrial respiration was the primary cause of aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells. While this hypothesis profoundly influenced early cancer metabolism research, it has now become increasingly clear that this interpretation has gaping. Advances in biochemistry, molecular biology and metabolomics demonstrate that mitochondria in many cancers are functional and play essential roles in biosynthesis, signaling and energy production. Aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells is now recognized as an adaptive metabolic strategy that supports rapid proliferation by providing metabolic intermediates, maintaining redox balance, and enabling cellular signaling rather than maximizing ATP yield. This review discusses the Warburg effect through the lens of modern cancer metabolism. It contrasts classical misconceptions with current evidences, discusses key regulatory pathways like HIF-1α, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, c-Myc and PKM2, and examine the central role of lactate as both a metabolic fuel and a signaling molecule. It further explores metabolic heterogeneity, the reverse Warburg effect, immune–metabolic interactions, and the relevance of oxidative phosphorylation in cancer. Finally, some unresolved questions are highlighted that is critical for future understanding of cancer metabolism.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Classical Interpretations and Common Misconceptions

- a)

- b)

- c)

- Lactate is primarily a waste product- In the cancer microenvironment, lactate is now recognized as an important metabolic fuel and signaling molecule

- d)

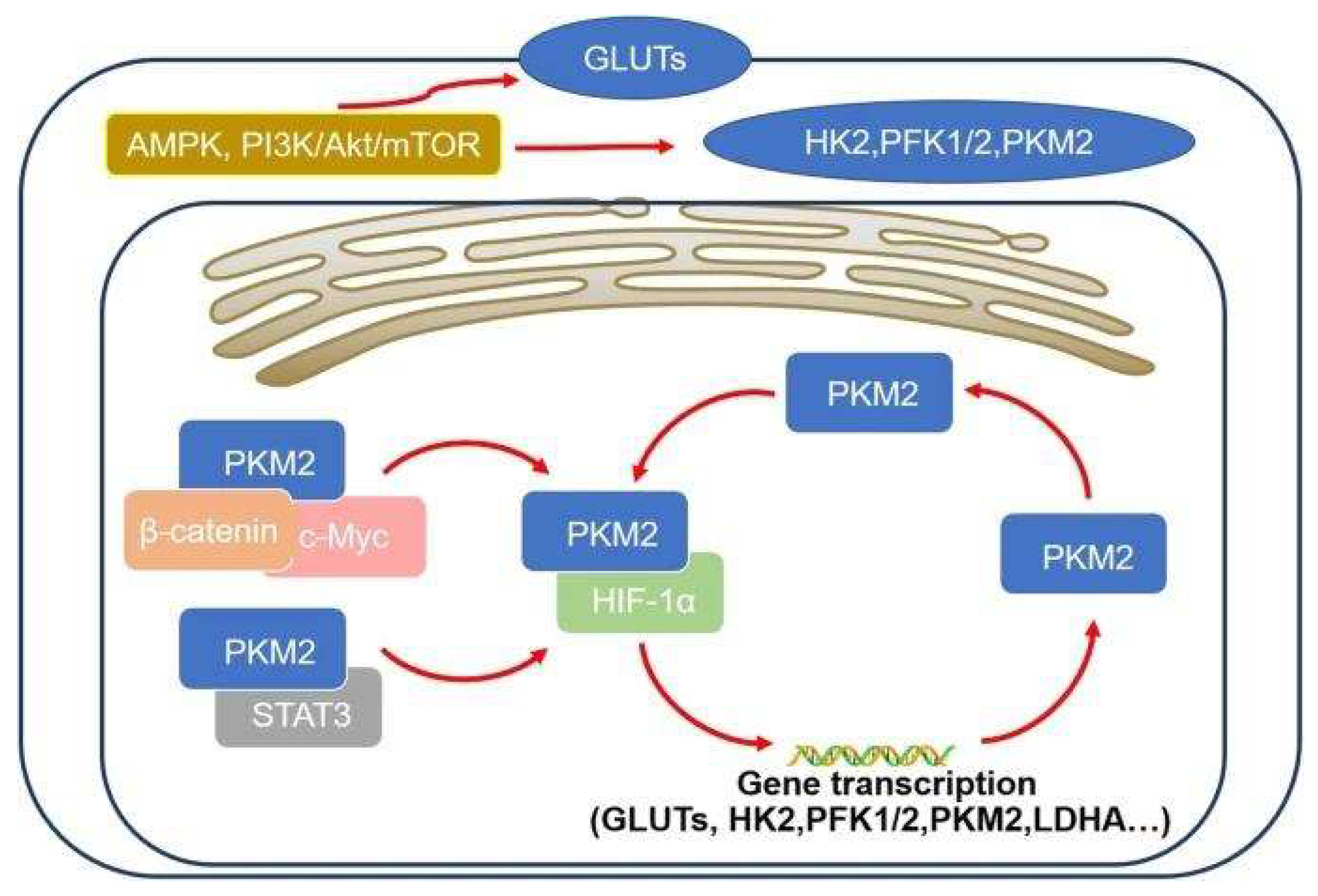

3. Molecular Regulation of Aerobic Glycolysis

3.1. HIF-1α Signaling

3.2. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway

3.3. c-Myc and Metabolic Coordination

3.4. PKM2 and Metabolic Control

4. Glycolysis as a Platform for Biosynthesis and Redox Balance

- Pentose phosphate pathway- Generates ribose-5-phosphate for nucleotide synthesis and NADPH for reductive biosynthesis and antioxidant defense [11]

- Serine and glycine metabolism- Supplies one-carbon units required for nucleotide and methyl group synthesis [12]

- Lipid biosynthesis- Glycolytic intermediates contribute to glycerol and fatty acid synthesis

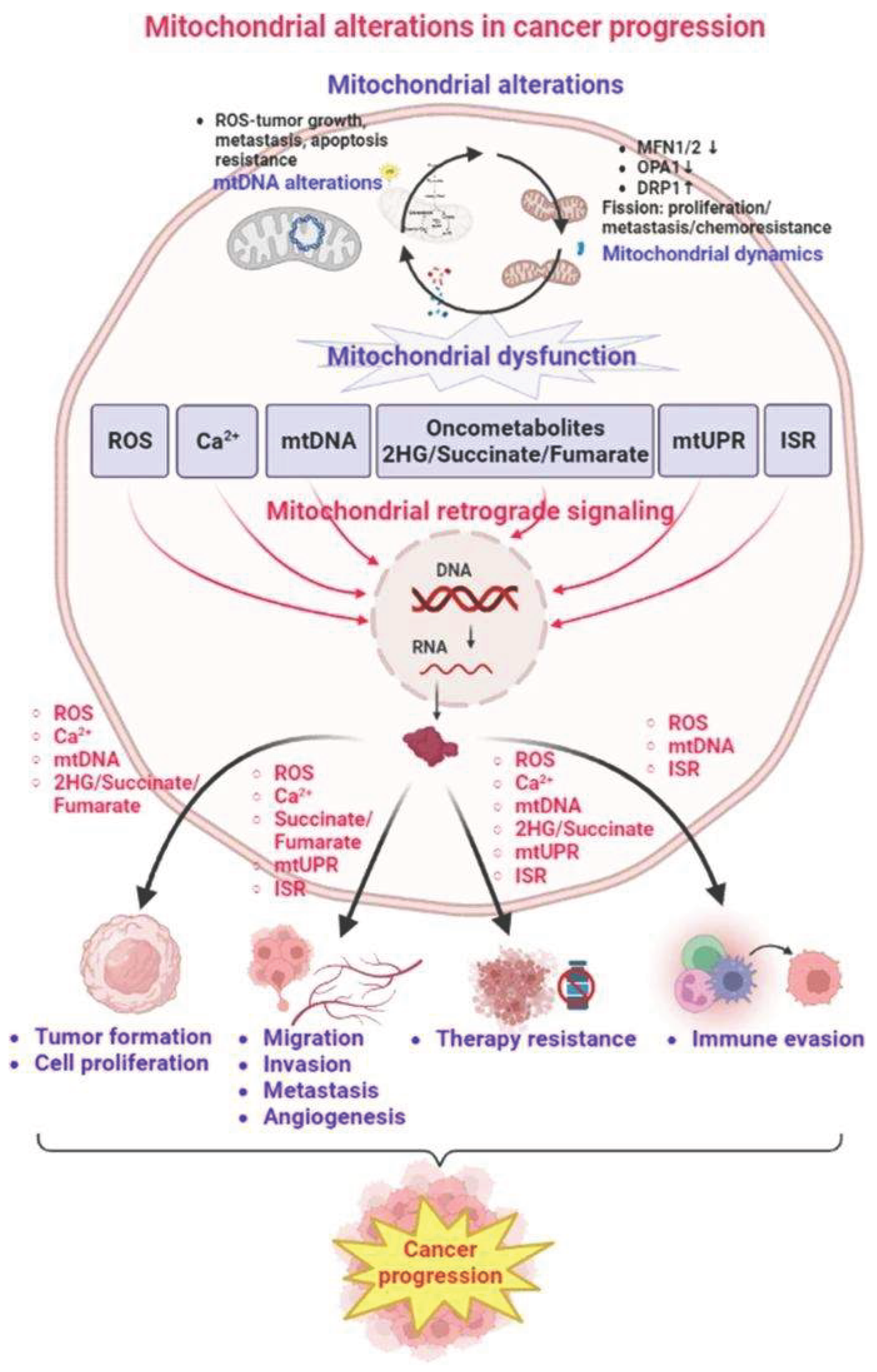

5. Mitochondrial Adaptation and Function in Cancer Cells

5.1. Mitochondria Are Hubs of Biosynthesis

- Citrate export for fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis

- Aspartate production, essential for nucleotide biosynthesis

- Anaplerotic glutamine metabolism to replenish TCA intermediates

- NADPH generation for antioxidant defense and lipid synthesis

5.2. Reductive Carboxylation in Hypoxia

- Reductive carboxylation of α-ketoglutarate to citrate

- Using NADPH-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)

- Supporting lipid synthesis under severely hypoxic conditions

5.3. Mitochondrial Signaling in Cancer Progression

- ROS-dependent signaling, affecting proliferation and survival

- Apoptosis resistance, via Bcl-2 family interactions

- Mitochondrial biogenesis, coordinated by Myc and PGC-1α pathways

6. The Emerging Role of Lactate as Fuel, Signal and Immune Modulator

6.1. Lactate as Carbon Source

- MCT1, which imports lactate

- Lactate dehydrogenase B (LDHB), which converts lactate back to pyruvate

- Oxidation in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle

6.2. Lactate Shuttle Within Tumors

- Hypoxic, glycolytic cells produce lactate

- Lactate is exported via MCT4, induced by HIF-1α

- Oxygen-rich tumor cells import lactate via MCT1

- Lactate becomes the major respiratory fuel in these cells

6.3. Lactate as an Angiogenic and Signaling Molecule

- VEGF expression

- Angiogenesis

- Increased nutrient delivery

6.4. Immunosuppressive Functions of Lactate

- T-cell proliferation

- Cytotoxic activity

- Cytokine (IFN-γ, IL-2) secretion

7. Tumor Microenvironment and Metabolic Cooperation

7.1. Reverse Warburg Effect

- Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) undergo aerobic glycolysis

- CAFs produce lactate and high-energy metabolites

- Cancer cells take up and oxidize this lactate for ATP

- CAFs undergo metabolic exhaustion while tumors thrive

7.2. pH Gradients and Acidification

- ECM degradation

- Increased invasiveness

- Selection for acid-resistant clones

- Impaired T-cell infiltration

8. Oxidative Phosphorylation Dependence and Metabolic Plasticity

8.1. Oxidative Phosphorylation Dependent Tumor Categories

- Efficient ATP generation

- ROS-mediated signaling for proliferation

- Fatty acid oxidation as fuel

- A stable redox environment

8.2. Cancer Stem-like Cells (CSCs)

- High mitochondrial mass

- Elevated oxidative phosphorylation activity

- Resistance to chemotherapy

- Ability to survive nutrient stress

8.3. Switching Between Glycolysis and Oxidative Phosphorylation

- Oxygen tension

- Nutrient availability

- Therapy exposure

- Micro environmental interactions

10. Future Directions

- What determines metabolic phenotype ?

- How can metabolic plasticity be predicted ?

- How does lactate influence immunotherapy outcomes ?

- How can metabolic therapies be personalized ?

11. Conclusions

References

- WARBURG, O. On the origin of cancer cells; Science: New York, N.Y.), 1956; Volume 123, 3191, pp. 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, X. L.; Guppy, M. Cancer metabolism: facts, fantasy, and fiction. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2004, 313(3), 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P. S.; Thompson, C. B. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer cell 2012, 21(3), 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyas, S.; Zaganjor, E.; Haigis, M. C. Mitochondria and Cancer. Cell 2016, 166(3), 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Physiology and Medicine. Cell 2012, 148, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, N. N.; Thompson, C. B. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell metabolism 2016, 23(1), 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C. V. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 2012, 149(1), 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halestrap, A. P.; Wilson, M. C. The monocarboxylate transporter family--role and regulation. IUBMB life 2012, 64(2), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Millán, I.; Brooks, G. A. Reexamining cancer metabolism: lactate production for carcinogenesis could be the purpose and explanation of the Warburg Effect. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38(2), 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, J. R.; Cleveland, J. L. Targeting lactate metabolism for cancer therapeutics. The Journal of clinical investigation 2013, 123(9), 3685–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, R. A.; Harris, I. S.; Mak, T. W. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature reviews. Cancer 2011, 11(2), 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locasale, J. W. Serine, glycine and one-carbon units: cancer metabolism in full circle. Nature reviews. Cancer 2013, 13(8), 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberti, M. V.; Locasale, J. W. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends in biochemical sciences 2016, 41(3), 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lu, Z. Regulation and function of pyruvate kinase M2 in cancer. Cancer letters 2013, 339(2), 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroughs, L. K.; DeBerardinis, R. J. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nature cell biology 2015, 17(4), 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonveaux, P.; Végran, F.; Schroeder, T.; Wergin, M. C.; Verrax, J.; Rabbani, Z. N.; De Saedeleer, C. J.; Kennedy, K. M.; Diepart, C.; Jordan, B. F.; Kelley, M. J.; Gallez, B.; Wahl, M. L.; Feron, O.; Dewhirst, M. W. Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 2008, 118(12), 3930–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Mellor, A. L. Metabolic control of tumour progression and antitumour immunity. Current opinion in oncology 2014, 26(1), 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xue, D.; Bankhead, A., 3rd; Neamati, N. Why All the Fuss about Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS)? Journal of medicinal chemistry 2020, 63(23), 14276–14307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, S. E.; Chandel, N. S. Targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy. Nature chemical biology 2015, 11(1), 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M. G.; Cantley, L. C.; Thompson, C. B. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2009, 324(5930), 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, K.; Hoffmann, P.; Voelkl, S.; Meidenbauer, N.; Ammer, J.; Edinger, M.; Gottfried, E.; Schwarz, S.; Rothe, G.; Hoves, S.; Renner, K.; Timischl, B.; Mackensen, A.; Kunz-Schughart, L.; Andreesen, R.; Krause, S. W.; Kreutz, M. Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid on human T cells. Blood 2007, 109(9), 3812–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Emerging roles and the regulation of aerobic glycolysis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2020, 39, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, SF.; Tseng, LM.; Lee, HC. Role of mitochondrial alterations in human cancer progression and cancer immunity. J Biomed Sci 2023, 23 30, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).