1. Introduction

The present study, developed within the scope of the FAIST project – Agile, Intelligent, Sustainable and Technological Factory (

www.faist.pt), describes the different phases of the design and development of a digital platform for the personalization and purchase of footwear, with the aim of demonstrating how digital design can support personalization, enhance user experience, and foster consumer engagement in the footwear sector.

Currently, the footwear industry faces significant challenges related to the complexity of production processes and the management of products at the end of their lifecycle [

1,

2]. In this context, the FAIST project emerges with the objective of strengthening the Portuguese footwear industry through the development of an innovative production process, centered on the design of a 3D-printed footwear model, adapted to the user’s anatomy and capable of aesthetic personalization.

Within this context, personalization plays a strategic role, as it allows footwear to be adapted to the individual characteristics and preferences of each consumer, contributing to a more comfortable and secure user experience while simultaneously strengthening the emotional relationship between the consumer and the product [

3,

4].

In order to maximize the potential of personalization, the development of effective and intuitive digital platforms is essential, promoting smooth navigation and optimized interaction [

5]. These platforms play a decisive role in fostering more dynamic and engaging collaborative processes, enhancing consumer involvement throughout the entire design and purchasing process [

5,

6].

Thus, through digital design, this study seeks to develop an interactive digital platform that enables users to intuitively and efficiently personalize the footwear model developed within the FAIST project, from three-dimensional (3D) foot scanning to aesthetic personalization, including the selection of colors, materials, and finishes.

To achieve the proposed objectives, the article is structured into six sections.

Section 2 presents the literature review on the main areas addressed in the study;

Section 3 describes the methodologies adopted;

Section 4 details the results obtained from usability testing;

Section 5 presents the discussion of the results and the study’s conclusions; finally,

Section 6 identifies the limitations of the work and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Personalization in the Footwear Industry

The personalization of products and experiences has become a central trend across several industries, driven by the growing consumer demand for offerings tailored to individual preferences and needs [

7]. This concept is based on the premise that each customer is unique, with personalization serving as a means of expressing this uniqueness by delivering products adapted to specific individual characteristics [

3]. According to Nobile and Cantoni [

8], the core principle of personalization lies in the use of consumer-specific data, such as body measurements and preferences, to design products uniquely tailored to each person. This process often involves the active participation of the consumer in defining product attributes, requiring an investment of time and effort. Such involvement may generate emotional and symbolic benefits, including a sense of authorship pride, arising from the perception of the product as an extension of the user’s identity and skills [

4]. As a result, personalization has a significant impact on the consumer experience, promoting higher engagement, customer retention, and trust in the brand. In addition, personalized messages and offers tend to be more memorable, appealing, and persuasive [

9].

According to Boër and Dulio [

10] personalization can be categorized into three dimensions: style/aesthetics, fit/comfort, and functionality/performance. The aesthetic dimension refers to the possibility for consumers to configure a base footwear model by selecting predefined variants, such as colors, patterns, or finishes. This type of personalization does not involve structural changes to the product but allows adaptation to the consumer’s personal style. In contrast, comfort personalization is more complex, as it requires structural modifications and the selection of materials and components suited to the specific morphological characteristics of each consumer. Finally, the functional dimension focuses on optimizing product performance through the selection of manufacturing processes and components adapted to specific usage conditions, being particularly relevant in contexts such as sports practice or professional performance.

Within this framework, the present research focuses on adapting footwear to the consumer’s foot anatomy, while also enabling the personalization of aesthetic aspects. Accordingly, based on the categorization proposed by Boër and Dulio [

10], this study addresses the fit/comfort and style/aesthetics dimensions.

Despite its inherent advantages, personalization also presents specific challenges. On the one hand, consumers tend to develop higher expectations regarding the quality, exclusivity, and level of detail of personalized products when compared to mass-produced goods [

11]. On the other hand, it is essential that the personalization process is supported by intuitive tools and interfaces capable of preventing frustration and ensuring that consumers can perform creative tasks efficiently [

12]. In this regard, effective interface design plays a decisive role in the success of the personalization experience, influencing not only usability and interaction flow but also users’ perception of the value and quality of the final product.

2.2. Gamification and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI)/ Human-Centered Design (HCD)

Gamification refers to the strategic use of game-like elements in non-game contexts, with the aim of increasing user engagement and improving the user experience (UX) [

13,

14]. In addition to stimulating interest and active participation, gamification has proven effective in organizing and simplifying complex content, contributing to greater user understanding and accessibility [

15].

The Octalysis Framework, developed by Yu-kai Chou [

16], is one of the most recognized methodologies for applying gamification. Its premise is based on the ability of games to activate specific motivations in each individual, encouraging repeated engagement with the experience. To this end, the model identifies eight Core Drivers, each representing a different type of motivation. Although not all drivers need to be present in a single interaction, it is essential that at least one is clearly incorporated to ensure user interest and engagement [

16].

Within this context, the Core Drivers most relevant to this study were analyzed, namely Empowerment, Accomplishment, Meaning, and Social Influence. Based on this analysis, the main interface actions were defined to address each type of user motivation.

Firstly, Empowerment emerges when users engage in a creative process that allows them to explore new possibilities and experiment with different combinations. In the proposed interface, this motivation can be supported through aesthetic product personalization, particularly in terms of colors, materials, and patterns, accompanied by immediate visual feedback on the selected options. Accomplishment is associated with personal achievement and is activated when the system defines clear goals, provides continuous feedback on progress, and rewards the user. In this project, structuring the personalization process into stages, supported by visual indicators such as progress bars or motivational messages, can foster a sense of achievement and encourage process completion. The Meaning Core Driver relates to the perception that user actions have a relevant impact or higher value. In this regard, the interface may reinforce this dimension by highlighting the ergonomic and health benefits resulting from adapting footwear to the user’s anatomy, as well as by communicating values such as sustainability and ethical production. Finally, Social Influence refers to motivation generated through interaction with others, social comparison, and a sense of belonging. Its integration into the proposed interface may be achieved through features that allow users to share personalized designs, comment on them, and compare their creations with popular models, thereby promoting a sense of community and social recognition of user choices.

For these reasons, the application of gamification principles in digital interface design is particularly effective, as it facilitates the selection of mechanisms that promote engagement with the platform and lead to more meaningful interactions.

In relation to the study of the relationship between people/users and systems/computers, the concept of Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) emerges. As a multidisciplinary field [

17], HCI integrates contributions from computer science, cognitive science, interface design (UI), and user experience (UX), and is essential for the creation of intuitive and accessible interfaces [

18]. According to Dix et al., [

19] the study of HCI requires an understanding of the human factor, particularly how users process information, make decisions, and manage errors during interaction with digital systems. For this purpose, it is crucial to consider aspects such as users’ needs, expectations, skills, and limitations, as well as how they perceive the interface and evaluate the effectiveness of the interaction [

20]. At the same time, HCI also involves analyzing the technological capabilities and limitations of computational systems, with the aim of developing solutions that maximize the quality of the user experience throughout the interaction [

19].

With the evolution of HCI, usability issues began to be addressed from the users’ perspective, placing them at the center of the development process [

20]. This shift led to the adoption of user-centered approaches and to the emergence of the concept of Human-Centered Design (HCD). HCD emphasizes the importance of understanding users’ needs, behaviors, and goals throughout all stages of the design process, promoting the creation of interfaces with high levels of usability and satisfaction [

20,

21]. By prioritizing factors such as usability, accessibility, and user satisfaction, HCD contributes to improving the overall user experience (UX) and strengthening user engagement with technology [

22].

In summary, while HCI focuses on the interaction between users and digital systems in the creation of functional and intuitive interfaces, HCD seeks to incorporate users’ experiences, motivations, and challenges throughout the entire design process. In the development of a footwear personalization interface, the integration of these approaches can foster empathy, facilitate communication, and enhance user engagement, leading to more effective and satisfying solutions [

23].

2.3. Emotional Design

Personalization relies on companies’ ability to collect and process customer-related information, as well as on consumers’ willingness to share data and use interfaces dedicated to the personalization process [

3]. Within this framework, Emotional Design seeks to strategically integrate affective components into the development of products, interfaces, and experiences in order to evoke specific emotional responses and strengthen the relationship with the user. Drawing on contributions from psychology, neuroscience, and design itself, Emotional Design aims to create solutions that are not only functional but also emotionally engaging [

24,

25].

One of the main authors in this field is Donald Norman, who, in the book

Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Things, describes three levels of emotional processing that influence user perception. The visceral level corresponds to the immediate and unconscious reaction triggered by the appearance of an object, playing a relevant role in competitive differentiation through elements such as color, form, or style, which can generate emotional associations and reinforce brand identity. The behavioral level relates to functionality and usability, focusing on ease of use and effectiveness in task completion. Intuitive interactions tend to generate positive emotions, while difficulties or inconsistencies lead to negative experiences. In turn, the reflective level involves a conscious evaluation of the meaning and value attributed to the experience, including aspects such as the product’s influence on self-image, social status, or symbolic meaning. At this level, users may accept certain functional limitations when they perceive emotional or social benefits that compensate for these shortcomings [

26,

27].

The relevance of Emotional Design in the field of digital experiences has been widely recognized and is often identified as a key component of User Experience Design (UX) [

24]. The deliberate integration of emotional aspects into the design process helps to improve the perceived usability, strengthen the bond between the user and the digital product, and make interactions more engaging and memorable [

27]. At the same time, it can promote user well-being by encouraging feelings of calm, trust, and satisfaction throughout the interaction journey [

28].

In summary, both Emotional Design and UX Design share the goal of creating positive and engaging experiences. Within the context of this research, the analysis of Emotional Design, combined with UX practices, aims to introduce a subjective and affective dimension into the relationship between the user and the footwear personalization interface, enhancing its attractiveness, meaning, and effectiveness.

2.4. UX/UI Design and Usability Heuristics

The present research aims to develop an online platform for footwear personalization, with a strong focus on delivering the best possible experience for the users. In this context, the application of User Experience (UX) and User Interface (UI) principles is essential to create an intuitive, functional, and visually appealing interface, playing a crucial role in optimizing the personalization process.

As such, UX Design refers to the process of creating different navigation scenarios and user flows by analyzing the user journey within a specific platform [

29]. At its core, UX Design focuses on problem-solving and interaction optimization, ensuring a satisfying and efficient digital experience [

30]. This process may involve several stages, including user research, persona definition, the development of wireframes and interactive prototypes, and the execution of usability tests [

31].

The concept of UI Design, in turn, concerns the creation and organization of the elements that make up an interface, such as menus, search fields, videos, and images. This process not only anticipates potential obstacles but also ensures that the interface presents accessible and easy-to-use elements [

32].

Usability is a key attribute of UI design quality and refers to the ease with which a user interacts with an interface. In practical terms, this metric evaluates the user’s ability to achieve a specific goal, within a given context, in an effective, efficient, and satisfactory manner [

33]. Although difficult to quantify, usability can be assessed through testing with real users, allowing for the early identification of difficulties and navigation issues. Additionally, the usability heuristics proposed by Jakob Nielsen and Rolf Molich provide essential guidelines for creating positive user experiences, ensuring that digital interfaces and platforms adequately respond to users’ needs and expectations. Applicable across different devices, these heuristics help minimize errors and challenges during the design process, making their adoption crucial for ensuring effective solutions and promoting intuitive and accessible navigation [

34].

2.5. Personas and Information Architecture

The development of personas is essential in the context of UI and UX Design, as well as in the creation of a digital platform, as it requires a thorough understanding of users to ensure that their needs are prioritized throughout all stages of the design process.

In this context, personas are fictional representations based on real data that aim to identify and understand the needs, goals, and behaviors of future users. These representations provide a solid reference to guide decision-making throughout the entire development cycle of a digital product or service. The creation of personas makes it possible to recognize the diversity of user expectations, contributing to the design of the best possible user experience [

35,

36]. As such, personas synthesize the main needs of different target audience segments, representing a variety of profiles that may benefit from the proposed digital solution. Understanding personas serves as a starting point for defining the Information Architecture.

Information Architecture is a field dedicated to the organization and structuring of content within digital interfaces, with the aim of facilitating user access and navigation. It involves creating structures that efficiently organize large volumes of information, ensuring that users can quickly find what they are looking for through a clear, intuitive, and functional interface [

37]. A well-structured Information Architecture reduces users’ cognitive load, preventing information overload and providing a smoother navigation experience. This optimization not only increases user satisfaction and engagement but also encourages continued use of the platform.

Following this process, usability testing emerges as a methodology focused on evaluating a platform’s usability through the participation of users who are representative of the target audience, with the aim of measuring and optimizing the interaction experience.

2.6. Usability Testing and the System Usability Scale (SUS)

Usability testing is an essential procedure for ensuring the quality of the user experience on a digital platform. It involves the direct observation of a representative group of users while they perform a set of tasks on a specific interface. During this process, a moderator observes participants’ behavior, records difficulties, and collects feedback, making it possible to identify obstacles that might otherwise go unnoticed without such analysis [

38]. The main objective of this method is to detect interaction problems within the digital product, enabling improvements based on real user experience. By observing users’ actions and preferences, valuable insights can be obtained to optimize both the interface and the overall user experience [

39].

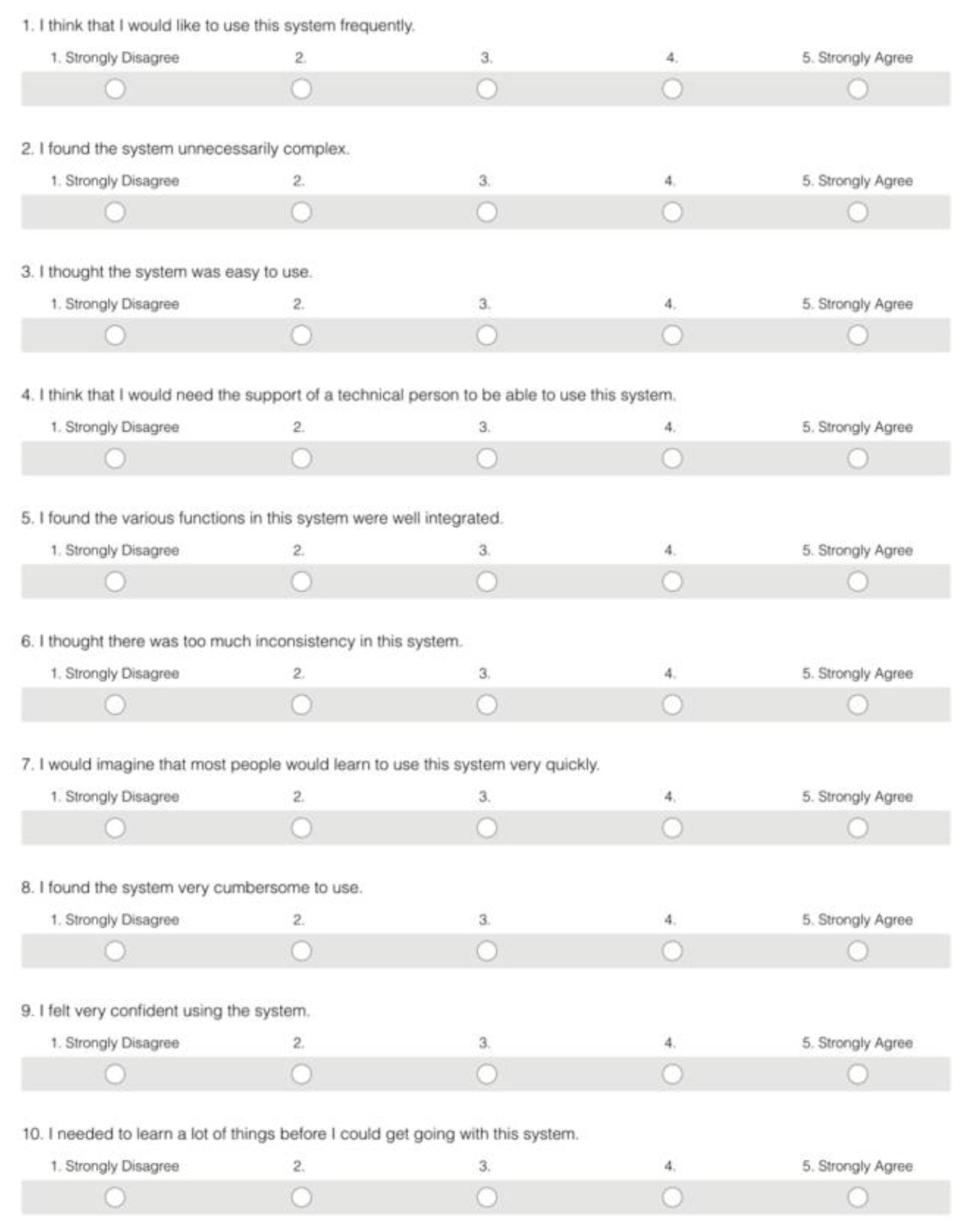

To complement usability testing, a widely used method for measuring users’ overall perception of a system’s usability is the System Usability Scale (SUS) [

40]. Developed by John Brooke, the SUS consists of a questionnaire with ten Likert-scale questions (

Figure 1), which is administered to all participants after the completion of the usability tests [

41].

Once the questionnaire is completed, the responses are converted into a score for each participant, ranging from 0 to 100. This score is then interpreted according to the scale proposed by Brooke (

Figure 2). The average SUS score is 68, however, for a platform’s usability to be considered excellent and ranked among the top 10%, a score of 80 or above is required [

42].

3. Methods and Techniques

For the development of this project, a methodology based on the principles of Design Thinking was applied. This approach is non-linear and iterative, with a strong focus on the user. From a process perspective, Design Thinking is divided into three main phases: Inspiration, Ideation, and Implementation. Through a sequence of stages, the project is structured and organized to achieve the main objective of this research, which is to create an interface that effectively responds to user needs and supports the purchase and promotion of personalized footwear.

During the Inspiration phase, it is essential to understand the central problem that guides the study. To this end, a literature review is conducted focusing on topics such as gamification, emotional design, and UX/UI design, allowing the identification of how these contributions can foster innovation and the repositioning of the footwear sector through interface design.

Subsequently, the Ideation phase focuses on exploring different perspectives through a comparative analysis of platforms related to footwear personalization, 3D printing, and digital scanning. This process enables the definition of a set of guidelines to inform the development of the interface, ensuring a more user-oriented response. At this stage, hypothetical user profiles based on potential platform users are also created, along with the definition of information architecture. This is supported by the development of wireframes and workflows that structure the interface navigation paths, content layout, and the relationships between pages.

Finally, in the Implementation phase, the interface prototyping process begins, followed by the application of usability tests. These tests aim to assess whether the interface is understood and used intuitively by users, as well as to identify potential areas for improvement.

3.1. Benchmarking: Digital Platforms for Footwear Personalization

The present benchmarking analysis aims to compare the main online platforms in the footwear industry selected for this study that are related to personalization. The primary objective is to understand best practices within the sector and to identify which features and functionalities can be incorporated into the interface under development to better respond to user needs.

Currently, several platforms offer footwear personalization solutions to consumers. However, no single platform was identified that fully matches the concept proposed in this research. For this reason, platforms that explore comfort personalization and aesthetic personalization were selected, in accordance with the categorization proposed by Boër and Dulio [

10]. To analyze comfort personalization, the platforms SizeRight [

43] e Volumental [

44] were considered, both recognized as leaders in 3D scanning technologies applied to the footwear sector. The Zellerfeld platform [

45] was also analyzed, as it stands out for its production process entirely based on 3D printing, making it a relevant case for this research. Regarding aesthetic personalization, the Nike by You platform [

46] was selected due to Nike’s international reputation and its status as a global reference in the footwear industry. Design Italian Shoes (DIS) [

47] was also included, as an Italian brand specializing in luxury footwear personalization. Finally, Acquarell Shoes [

48], a Portuguese brand distinguished by its cultural and geographical proximity, was selected.

This strategic selection enables a comprehensive comparative analysis, covering different approaches to footwear personalization in both national and international contexts.

Table 1 presents an analysis of the functionalities offered by the platforms, along with an evaluation based on usability heuristics.

Regarding the analyzed platforms, it can be concluded that aesthetic personalization is often associated with the creation of a personal user profile. In addition, these platforms provide consumers with information about the brand’s projects, although only one – Zellerfeld - uses animations and explanatory videos for this purpose. Another common feature is the use of 3D product models, allowing real-time modifications, 360º visualization, and zoom functions, which enhance both personalization and interaction between products and consumers. Some platforms, such as Nike by You and Acquarell Shoes, offer design suggestions to users. However, only Nike by You provides an overview of the personalization process, informing users about the number of steps involved.

Immediate feedback on user choices, the use of clear and familiar language, and the possibility to correct errors or undo actions are predominant characteristics across all analyzed platforms. More broadly, a minimalist design approach and the use of light backgrounds are also observed, highlighting products and high-contrast images. This reflects a clear concern with information perception and readability.

It is therefore essential to ensure a clear and intuitive presentation of the information provided to users throughout the footwear personalization process. Any ambiguity in the representation of available options or in the visualization of the final product may compromise the personalization experience, affecting decision-making and, consequently, user satisfaction.

Based on the comparative analysis, a set of key elements was identified as essential for the development of a footwear personalization interface:

User registration / personal profile area: significantly improves the navigation and purchasing experience, making the process faster, more personalized, and more convenient;

Project and product explanation: presents brand values and product characteristics, educating users and strengthening trust in the brand;

3D product model with 360º visualization, zoom, and real-time updates: enriches the interactive experience, allowing users to accurately visualize the final product and increasing confidence in the personalization process;

Dynamic price updates based on selected personalization’s: ensure cost transparency and prevent unexpected charges at checkout;

Design suggestions: inspire users, particularly those who are undecided or seeking ideas, encouraging exploration of different combinations;

Clear information about the steps of the personalization process: guides users and ensures an intuitive and understandable experience;

Onboarding for new users: facilitates adaptation to the platform from the first access, providing a friendly and efficient introduction;

Minimalist, clear, and functional design: reduces cognitive load, highlights essential elements, and ensures an accessible and inclusive interface.

3.2. Personas

The definition of personas is an effective methodology within user-centered design, enabling a thorough understanding of users’ needs, motivations, and behaviors. Based on profiles inspired by real users, personas guide design decisions, from the definition of functionalities to the structure of the interface, ensuring a closer alignment between the proposed solution and the expectations of end users. To be effective, personas should be built on a comprehensive set of informational elements, such as a representative image, profile description, behavioral patterns, goals, needs and frustrations [

49,

50].

In this project, personas were developed in close collaboration with the FAIST project team and coordinator. This collaboration made it possible to identify profiles representative of potential users, considering the project objectives and the most likely usage scenarios.

In this context, no specific age range was defined for the target audience to ensure the platform’s adaptability to different user profiles and their respective needs. Accordingly, contrasting personas were developed to reflect the diversity of potential users, whose motivations range from the prioritization of anatomical comfort to the pursuit of aesthetic personalization, or a combination of both. This approach allows the integration of different priorities, values, and usage patterns, contributing to the development of a flexible interface tailored to consumer demands.

Table 2 presents the developed personas organized into four sections, highlighting their main characteristics, usage scenarios, and objectives.

3.3. Information Architecture

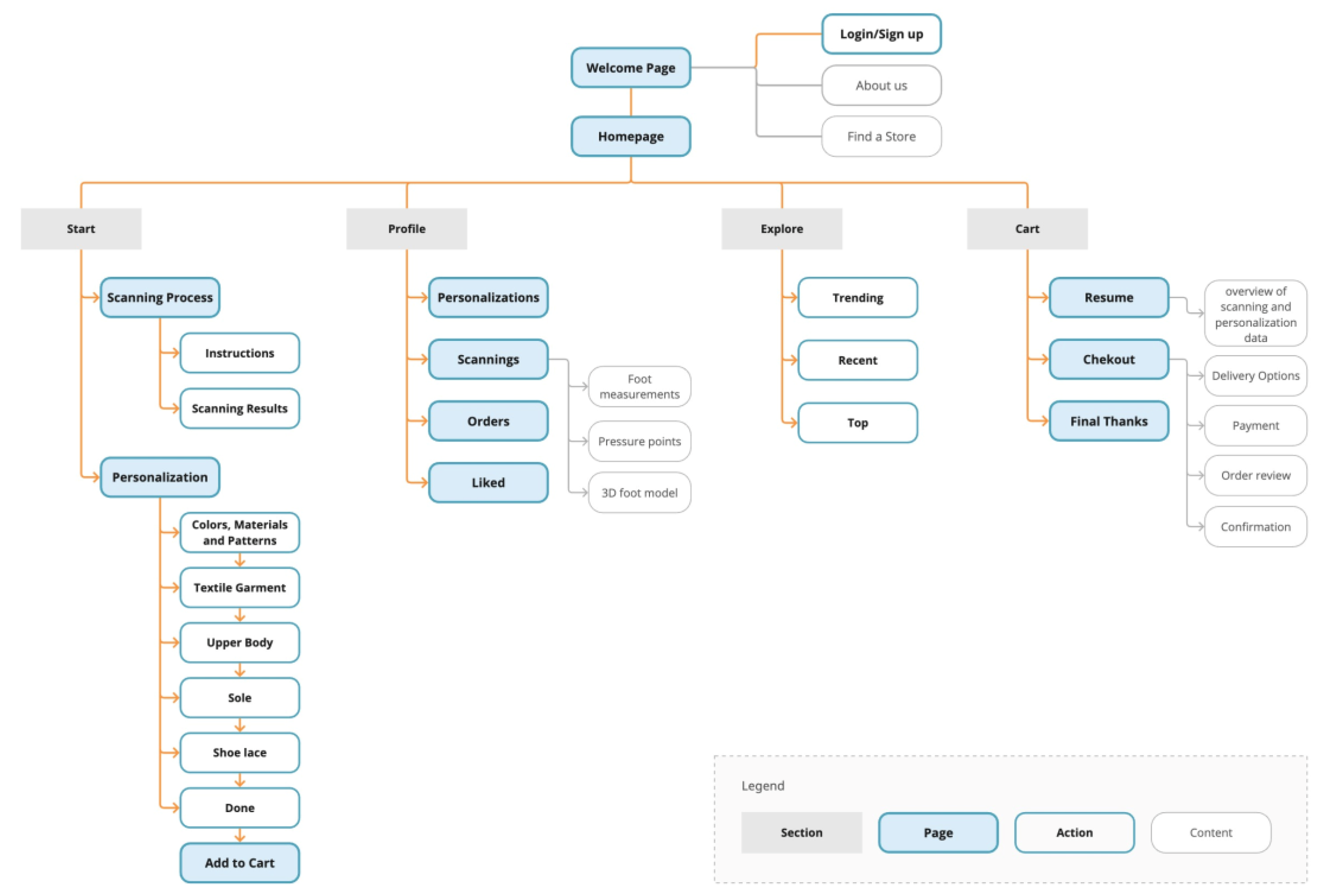

The Information Architecture phase followed the development of the personas and represented a decisive step in defining the structure and organization of the interface.

Recognizing the importance of clear, intuitive communication aligned with the identified user profiles, a diagram was developed to illustrate the informational structure of the interface (

Figure 3).

The diagram presents the welcome page, which represents the entry point to the platform. This section includes the login and registration functionalities. After logging in or registering, the user gains access to the homepage, composed of five main sections, namely “Start”, “Profile”, “Explore” and “Cart”, organized to promote coherent and user-centered navigation.

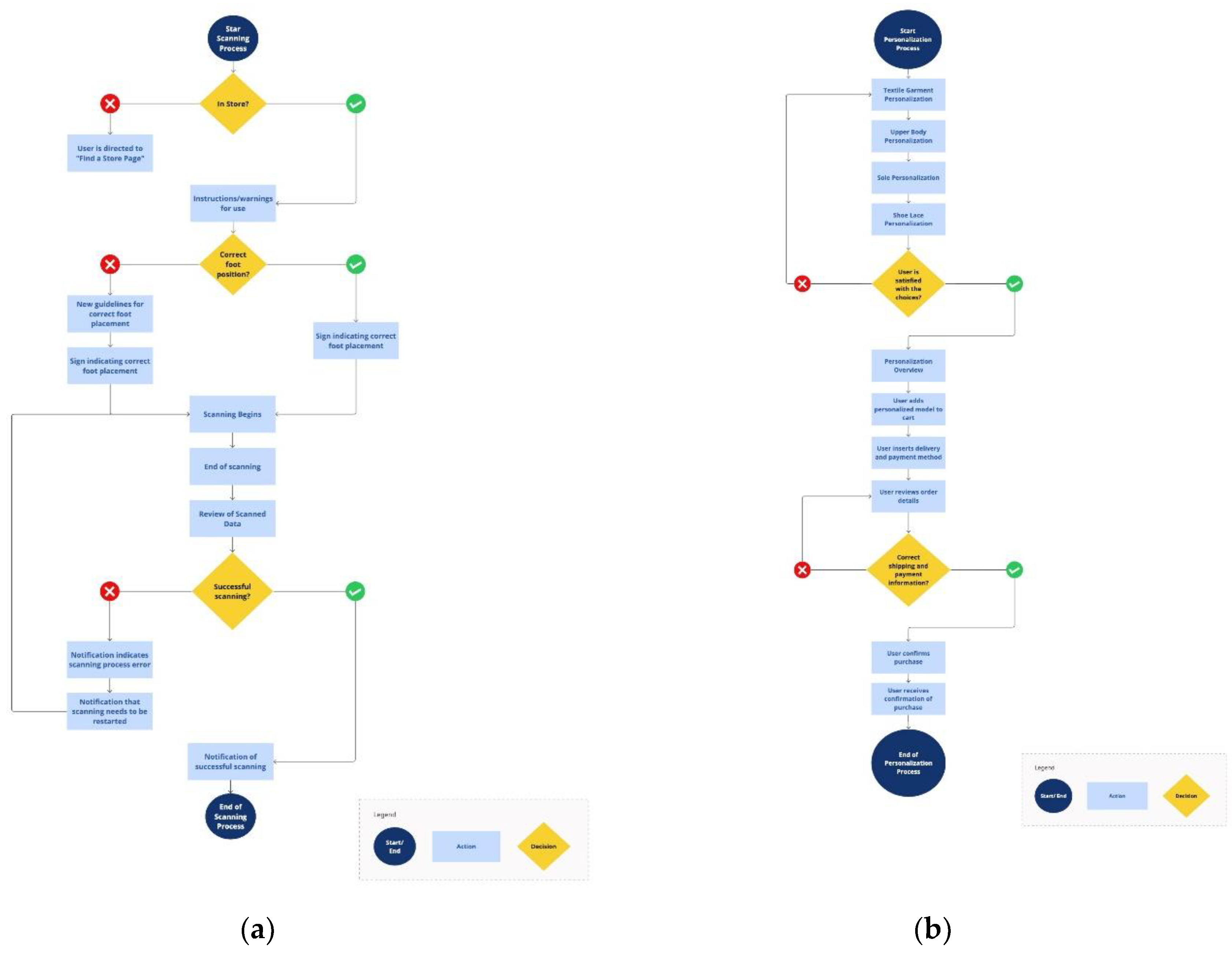

In addition, user flows related to the foot scanning process and the aesthetic personalization of the footwear were also developed (

Figure 4). User flows are diagrams that describe the paths users may follow to complete tasks when interacting with a product. They focus on user needs and on the most efficient way to meet them [

51], allowing potential obstacles to be anticipated, critical navigation points to be identified, and the overall user experience to be optimized. By visually structuring the interaction journey, user flows contribute to clear, coherent, and task-oriented navigation.

The defined flows make it possible to guide the scanning and personalization processes in a logical and accessible manner, ensuring the correct execution of tasks and a clear and coherent understanding of the interface. The development of these interaction paths and their corresponding functionalities resulted from a comparative analysis of competing platforms, a review of the literature, and the contributions and suggestions of the FAIST project team members.

Finally, the wireframes and workflows for the platform were defined. The wireframing process consists of defining the structure and flow of digital solutions through simplified representations of the interface. These representations focus on the layout and functionality of essential elements, such as menus, buttons, text blocks, images, and videos, while excluding decorative visual components like color, typography, or graphic elements to maintain a clear focus on the functional organization of the system [

52].

Although this approach corresponds to a low-fidelity and therefore short-term methodology, it allows the evaluation of the clarity of the actions required to complete tasks, as well as the intuitiveness and coherence of the interface.

In addition, workflows link the visual structure of wireframes with the connections and transitions between screens, describing user interactions throughout the interface in detail. This process contributes to the early identification of issues, ensures the functional coherence of the solution, and promotes a clear and efficient user experience [

53].

This approach enabled rapid exploration of design ideas, facilitating the visualization of different possibilities for organizing and structuring the interface. In this way, design concepts could be validated before progressing to more detailed development stages, such as prototyping.

3.4. Prototyping and Usability Testing

Prototyping is a methodology widely used in the final stages of the design and testing of products or services. It functions as an experimental model, allowing ideas to be tested, evaluated, and validated at an early stage [

54]. Within the scope of Design Thinking and User Experience, this methodology uses multiple techniques and tools to quickly and objectively test products with digital or physical properties.

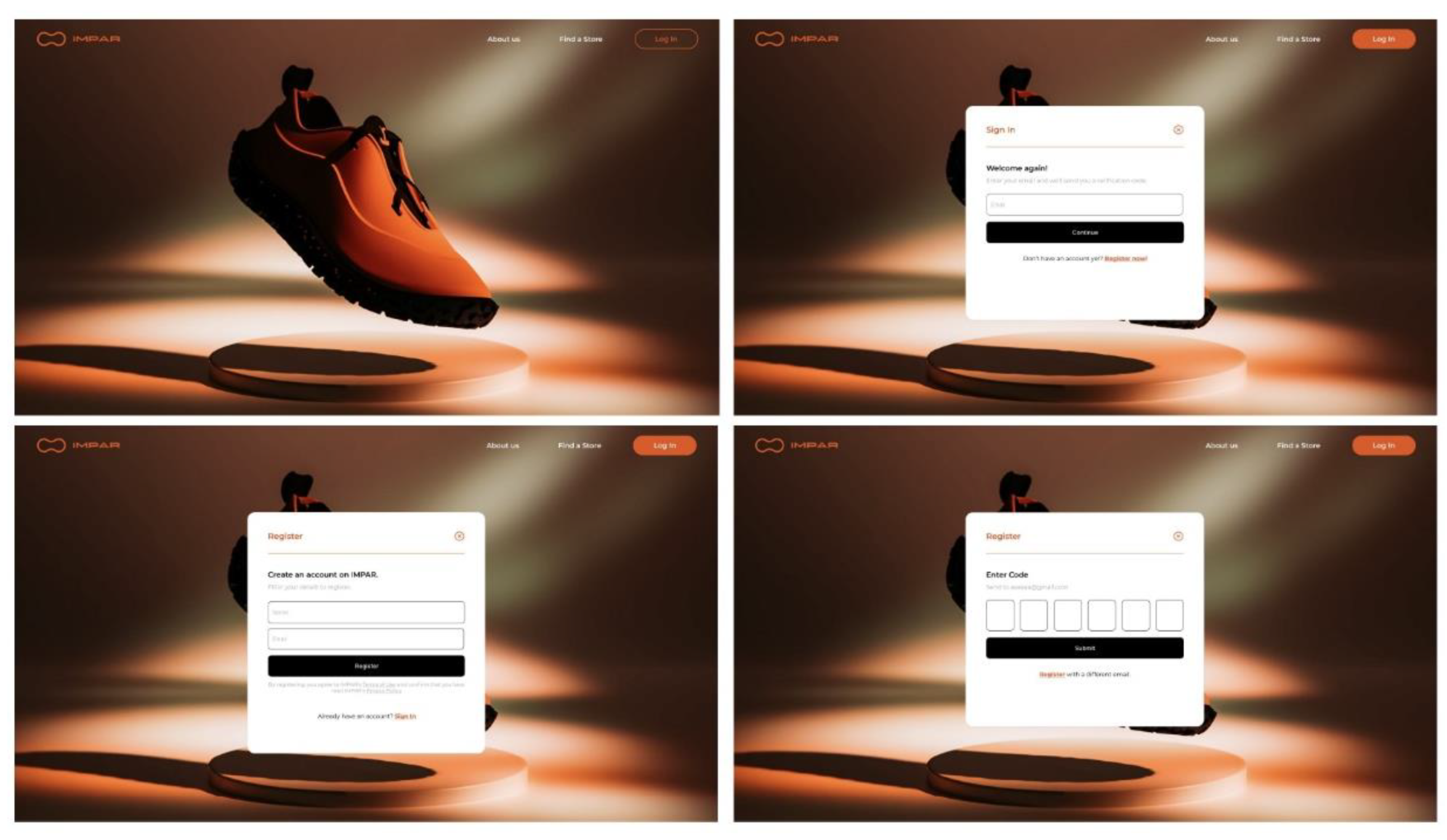

In this context, the prototype of the platform for the personalization and purchase of customized footwear was developed based on previously established guidelines, with the aim of evaluating its effectiveness. The prototype included the design of the main interface sections, particularly the login and registration pages (

Figure 5), which are considered essential for accessing the remaining areas of the platform. For the authentication process, an email-based method was adopted, with verification carried out through the delivery of a six-digit numerical code to the provided email address. This approach stands out for its simplicity, speed, and convenience, eliminating the need to create a password. By reducing barriers commonly associated with authentication processes, it contributes to a smoother and more accessible user experience, encouraging greater user adoption.

Usability testing aims to evaluate how easily and efficiently users can navigate the interface of a digital platform. The application of this methodology is based on the observation and analysis of the behaviors of a representative group of users while they perform predefined tasks. Accordingly, the main objective is to assess the user experience by considering the clarity and success of their interaction with the different paths and functionalities of the interface.

According to Nielsen’s recommendations [

55], usability tests are more effective when conducted iteratively with a small number of users. The author states that, on average, five users are sufficient to identify most usability issues, within a process that should be iterative and support the progressive refinement of the interface.

Based on this principle, two usability testing sessions were conducted, each involving eight participants. In the first session, participants’ ages ranged from 25 to 64 years, while in the second session ages ranged from 25 to 54 years. The sample was selected according to the profiles described in

Table 2 (Persona’s analysis), prioritizing users who experience difficulties when purchasing footwear and who show an interest in personalization solutions. Additionally, participants without significant constraints in this process were included to test the platform’s relevance for typical users.

After the usability tests were completed, the post-test System Usability Scale (SUS) questionnaire (

Figure 1) was administered to quantitatively measure the prototype’s usability. The SUS proved to be an effective instrument for systematically and simply evaluating both usability and user satisfaction during interaction with the prototype. Once the questionnaire was completed, individual user scores were calculated and are presented in

Table 3.

4. Results

Overall, the feedback and results obtained regarding the platform and its interface were very positive. The System Usability Scale (SUS) scores ranged from 75 to 92.5, indicating a favorable perception of the user experience. Nevertheless, these results suggest that some tasks presented a higher level of difficulty for certain users.

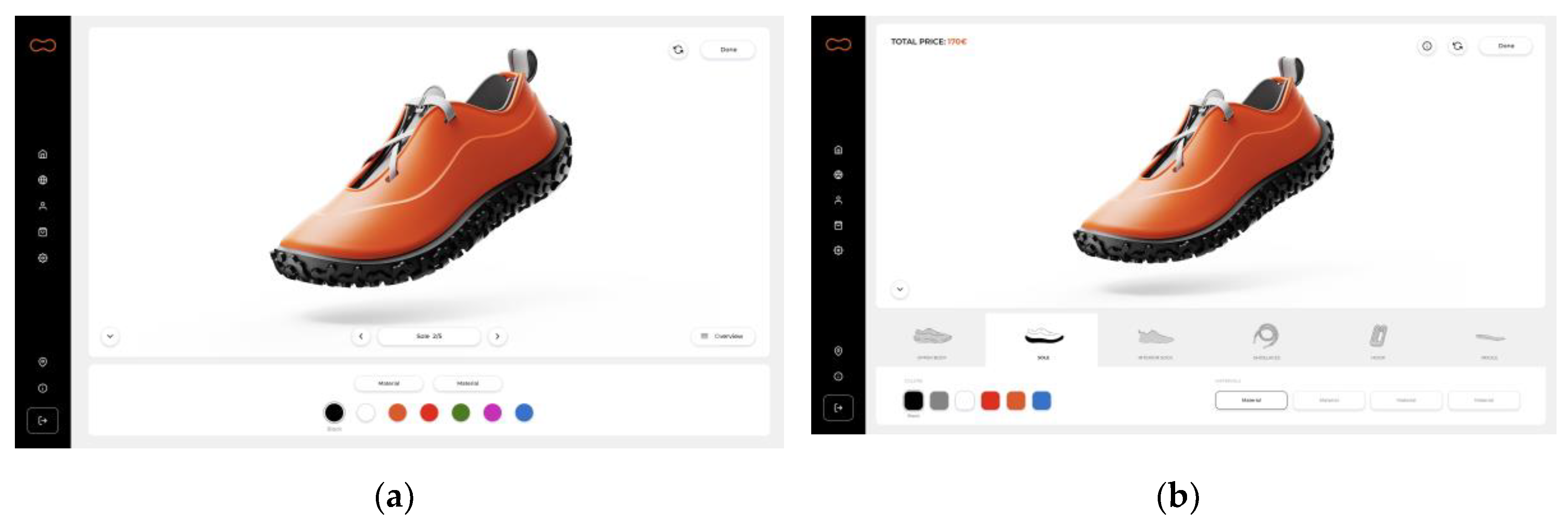

Following this, changes and improvements were implemented in the prototype based on user observation and feedback, covering both design and functionality, as well as content labels and organization. One of the main difficulties identified occurred during the aesthetic personalization process, where users had trouble associating the labels used with the different parts of the sneaker. To address this issue, the personalization menu was adjusted to include vector images of the different shoe components, making them easier to identify.

Figure 6 illustrates the changes implemented in this process.

The second round of usability testing was conducted in person with the same number of participants.

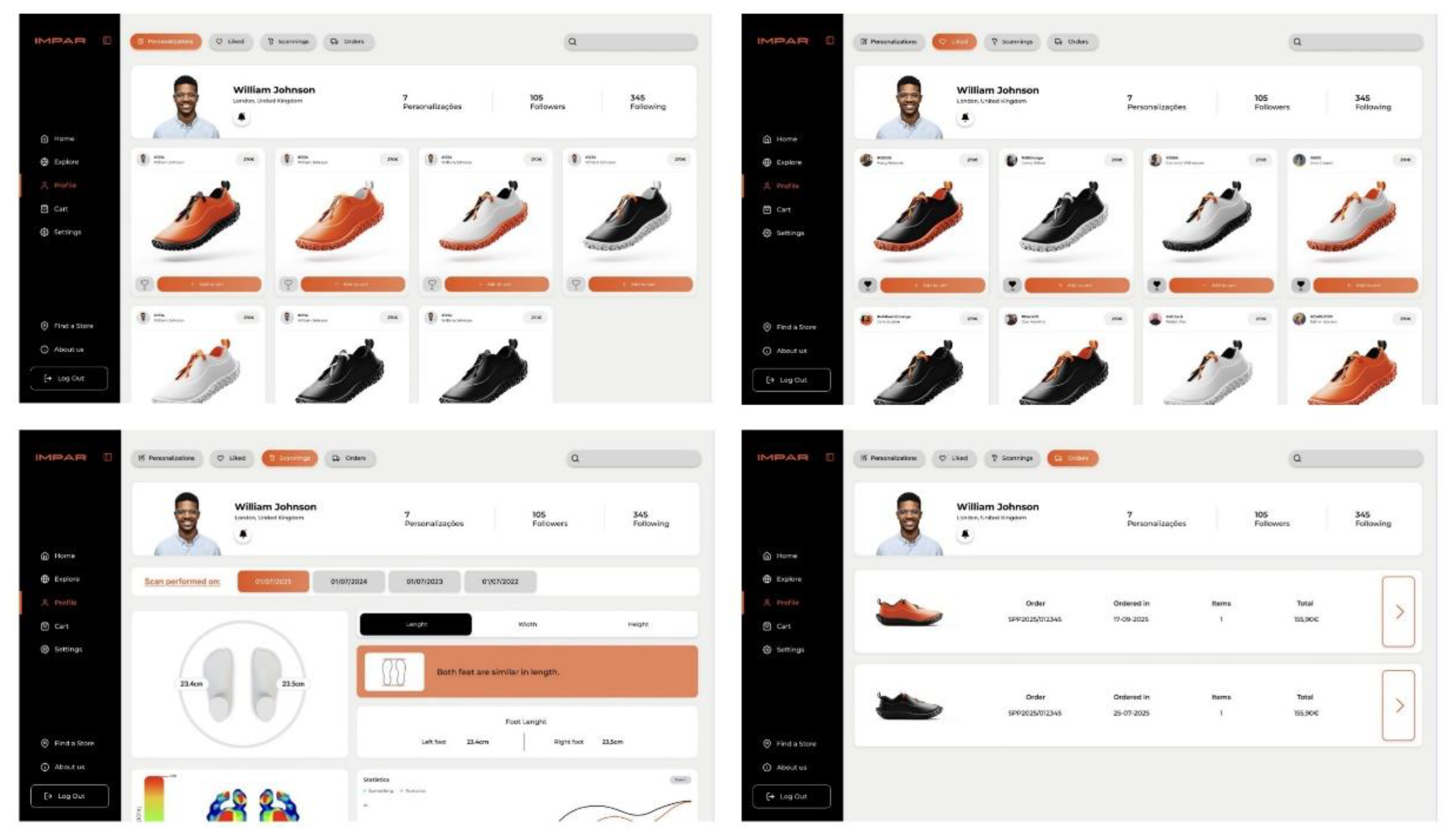

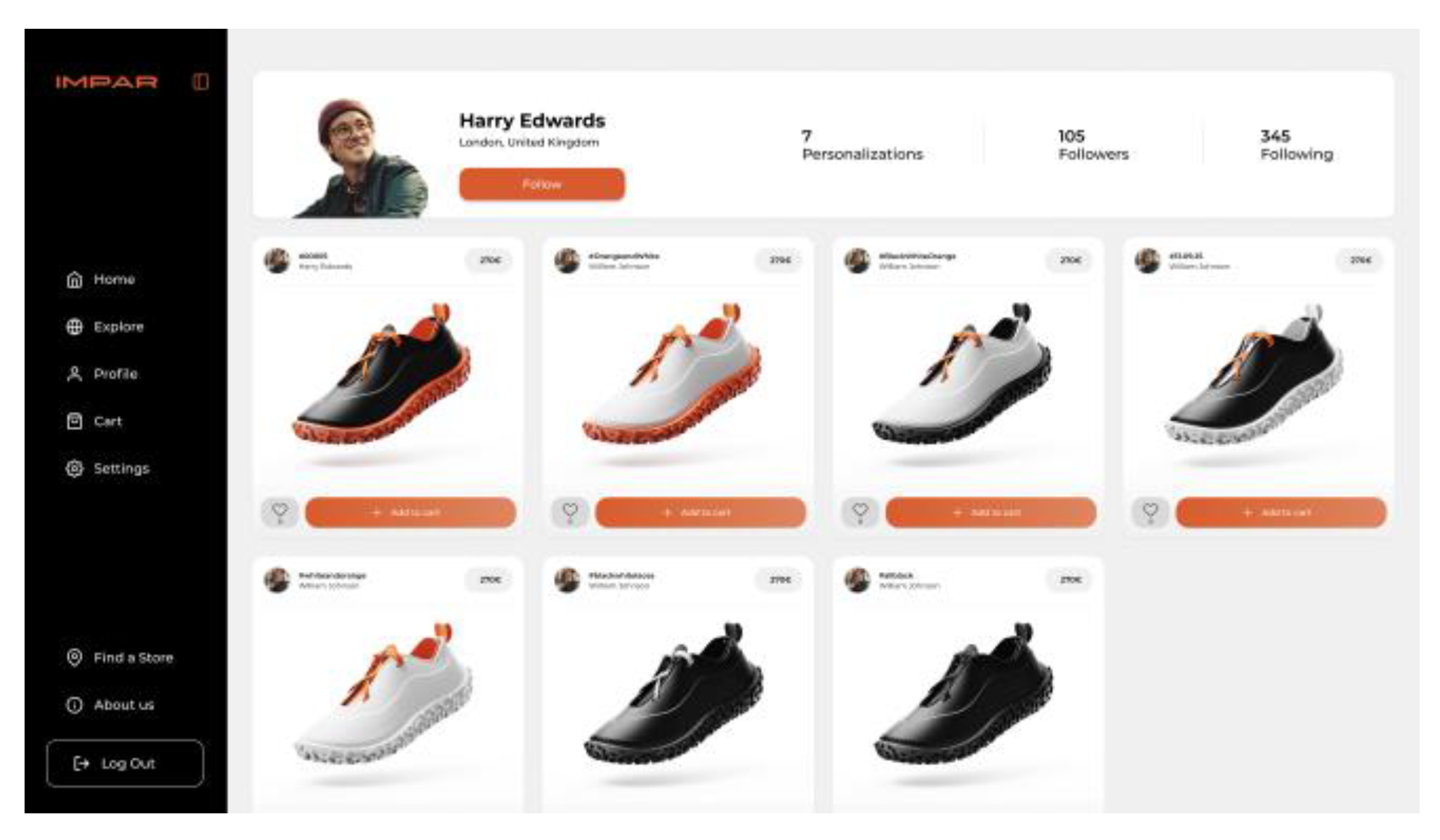

This new data collection made it possible to understand how the implemented changes contributed to improved navigation flow and a more intuitive user experience. During this second testing session, participants also suggested further improvements, namely the possibility of viewing other users’ profiles and following or being followed (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), bringing the platform closer to a more interactive and social model. These suggestions highlight the relevance of further developing the platform’s community dimension, encouraging greater user engagement and interaction.

Table 4 presents the scores obtained in the second usability testing session, in which a higher level of user satisfaction can be observed. In this second sample, the lowest recorded score was 85 points, while the highest reached 100 points, confirming the importance of testing the platform with real users and incorporating the suggested improvements to achieve a more intuitive and effective final prototype.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The main objective of this project was the design and development of a digital platform for the purchase of personalized footwear, aligned with the needs identified within the FAIST project - Agile, Intelligent, Sustainable and Technological Factory. This research sought to address the lack of a digital solution that allows users to intuitively and efficiently perform three-dimensional (3D) foot scanning and the aesthetic personalization of a sustainable footwear model.

To achieve the proposed objectives, the study began with a systematic literature review, which provided a theoretical framework for concepts such as footwear personalization, emotional design, gamification, User Experience (UX), and User Interface (UI). This bibliographic analysis proved essential for understanding the relationships between footwear personalization, user-centered design, and the development of interactive and emotionally engaging digital interfaces.

Subsequently, a benchmarking study was conducted on footwear personalization platforms available on the market. The comparative analysis revealed that clarity and intuitiveness in information presentation are key factors for a satisfactory navigation experience. It was observed that ambiguities in the communication of available options, product visualization, or guidance throughout the personalization process can compromise the user experience, affecting not only foot scanning and aesthetic personalization but also the completion of the purchase.

From this analysis, a set of best practices and relevant functionalities emerged for the development of the proposed interface. These include the creation of a personal profile area; clear presentation of the project and products; integration of a three-dimensional footwear model with real-time visualization of changes; dynamic price updates based on selected options; availability of predefined design suggestions; clear information about the steps of the personalization process; implementation of an onboarding process; and the adoption of a minimalist, clear, and functional design.

Based on these findings, a digital interface solution was developed, supported by UX and UI design principles and using methodologies such as persona creation, information architecture definition, wireframe and workflow development, and usability testing with the System Usability Scale (SUS). These methodologies focused on optimizing interaction and addressing usability issues, ensuring the development of a satisfactory and efficient digital experience.

In parallel, gamification strategies were incorporated, namely the Octalysis Framework developed by Yu-kai Chou [

16], with the aim of activating specific user motivations, promoting continuous engagement and repeated use of the platform. This approach helped transform interaction with the platform into a more playful and participatory experience, reinforcing users’ sense of control and satisfaction.

The resulting prototype was developed with a strong focus on usability, informational clarity, and visual coherence, and received positive feedback from potential users. This positive response confirmed the relevance of the design decisions made throughout the process, highlighting the ease of use, clarity of navigation, and visual consistency of the proposed solution.

It can therefore be concluded that the project not only fulfilled its purpose of facilitating the personalization and purchase of personalized footwear but also reinforced its commitment to demonstrating the potential of digital technologies in fostering innovation within the footwear sector. The digital design workflow presented in this article can be successfully applied within the footwear industry or in other contexts, contributing to enhanced personalization and promoting active consumer participation in product creation. Each stage of development was carefully planned to ensure an intuitive, efficient, and emotionally engaging user experience, addressing both the specific needs of the target audience and the strategic objectives of the FAIST project.

6. Limitations Found and Future Work

Although the study achieved its initially defined objectives, several significant limitations were identified. One of the main challenges was related to the project timeline, which limited the possibility of further in-depth investigation and the execution of more extensive usability testing of the platform.

Additionally, because the prototype was not implemented using programming technologies, it was not possible to collect more detailed data on the interaction flow between users and the developed system. Furthermore, the prototyping tool used (Figma), while suitable for developing high visual fidelity interfaces, did not allow for a full simulation of the interactive personalization experience, particularly the manipulation of the 3D model, which is a central element of the project’s value proposition.

Finally, the usability testing process was constrained by both time limitations and the technical restrictions of the prototype. This made it difficult to implement the dynamic interactions and animations originally planned, which may have influenced users’ perception of the realism and fluidity of the experience.

Despite these limitations, the continuation of the project is planned to ensure the full operationalization of FAIST investigation. To this end, the developed interface will be implemented, ensuring full functionality of the aesthetic personalization of the models and enabling direct purchase through the platform.

The implementation of the prototype will make it possible to evaluate its effectiveness in a real usage context, providing relevant data on user interaction with the platform. Based on this evaluation, new rounds of usability testing may be conducted, allowing the collection of real-time feedback regarding user satisfaction, encountered difficulties, and areas requiring improvement. Based on the feedback obtained, continuous adjustments and refinements can be made, promoting the iterative evolution of the product and ensuring its alignment with users’ real needs and expectations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., N.M. and M.T.; methodology, M.G., N.M. and M.T.; software, M.G., N.M. and M.T.; validation, M.G., N.M. and M.T.; formal analysis, M.G., N.M. and M.T.; investigation, M.G.; resources, N.M. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G., N.M. and M.T.; writing—review and editing, N.M. and M.T.; supervision, N.M. and M.T.; project administration, M.T.; funding acquisition, N.M. and M.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the FAIST project – Agile, Intelligent, Sustainable and Technological Factory, through funds from the “Next Generation EU” programme, under the Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRR), reference C644917018-00000031.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Rensburg, M.L.; Nkomo, S.L.; Mkhize, N.M. Life Cycle and End-of-Life Management Options in the Footwear Industry: A Review. Waste Management and Research 2020, 38, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, Z.R. Water, Energy and Carbon footprints of a Pair of Leather Shoes; ITM School of Industrial Engineering and Management: Stockholm, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Verma, S.; Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Personalization in Personalized Marketing: Trends and Ways Forward. Psychol Mark 2022, 39, 1529–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N.; Cunha, J.; Carvalho, H. Co-Design and Mass Customization in the Portuguese Footwear Cluster: An Exploratory Study. In Proceedings of the Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V., 2019; Vol. 84, pp. 923–929.

- Randall, T.; Terwiesch, C.; Ulrich, K.T. Principles for User Design of Customized Products. Calif Manage Rev 2005, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthouse, E.; Hofacker, C. Looking Back and Looking Forward with Interactive Marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2010, 24, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordone, G. The Global State of Fashion Personalisation in 2024: Market Segmentation, Trends, and Geographical Insights; 2024.

- Nobile, T.H.; Cantoni, L. Personalization and Customization in Fashion: Searching for a Definition. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 2023, 27, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaca, J.A.; Miguel, L.P. The Influence of Personalization on Consumer Satisfaction: Trends and Challenges. In Data-Driven Marketing for Strategic Success; IGI Global, 2024; pp. 256–292. ISBN 9798369334560. [Google Scholar]

- Boër, C.; Dulio, S. Mass Customization and Footwear: Myth, Salvation or Reality? Springer: London, 2007; ISBN 978-1-84628-864-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wind, J.; Rangaswamy, A. Customerization: The next Revolution in Mass Customization; 2001; Vol. 15.

- Oliveira, N.; Cunha, J. Footwear Customization: A Win-Win Shared Experience; 2018.

- Marache-Francisco, C.; Brangier, E. The Gamification Experience: UXD with a Gamification Background. In Emerging Research and Trends in Interactivity and the Human-Computer Interface; IGI Global, 2013; pp. 205–223. ISBN 9781466646247. [Google Scholar]

- Bitrián, P.; Buil, I.; Catalán, S. Enhancing User Engagement: The Role of Gamification in Mobile Apps. J Bus Res 2021, 132, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.; Martins, N.; Cunha, P.; Soares, F.; Carvalho, V. The Role of Design and Digital Media in Monitoring and Improving the Performance of Taekwondo Athletes. Designs (Basel) 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-K. Actionable Gamification Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards; Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.: North Charleston, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, G.; Shahi, R.; Shankar, M. Human Computer Interaction. In International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology ; 2010.

- Interaction Design Foundation What Is Human-Computer Interaction (HCI)? Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/human-computer-interaction? (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Dix, A.; Finlay, J.; Abowd, G.; Beale, R. Human-Computer Interaction; 2004.

- Ferreira, D.; Venturelli, S. O Design Centrado No Ser Humano e Os Desafios Para a Interação Humano-Computador a Partir Da ISO 9241-210:2019. DAT Journal 2022, 7, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, F.; Yadav, L.; Deharkar, A. Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Emma, L. Human-Computer Interaction: Designing User-Centric Interfaces 2024.

- Langote, M.; Saratkar, S.; Kumar, P.; Verma, P.; Puri, C.; Gundewar, S.; Gourshettiwar, P. Human–Computer Interaction in Healthcare: Comprehensive Review. AIMS Bioeng 2024, 11, 343–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A. The Impact of Emotional Design in UX 2024.

- Yusa, M.; Ardhana, K.; Putra, N.; Pujaastawa, I. Emotional Design: A Review of Theoretical Foundations, Methodologies, and Applications. Journal of Aesthetics, Design, and Art Management 2023, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komninos, A. Norman’s Three Levels of Design.

- Norman, D. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books, 2004.

- Interaction Design Foundation What Is Emotional Design (ED)? Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/emotional-design (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Unger, R.; Chandler, C. A Project Guide to UX Design: For User Experience Designers In The Field Or In The Making, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education, 2024; ISBN 9780321815385. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.; Nielsen, J. The Definition of User Experience (UX). Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/definition-user-experience/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Interaction Design Foundation User Experience (UX) Design. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/ux-design#what_is_user_experience_(ux)_design?-0 (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Charfi, S.; Trabelsi, A.; Ezzedine, H.; Kolski, C. Widgets Dedicated to User Interface Evaluation. Int J Hum Comput Interact 2014, 30, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interaction Design Foundation What Is Usability? Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/usability (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Nielsen, J. 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Dam, R.; Siang, T. Personas – A Simple Introduction. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/personas-why-and-how-you-should-use-them? (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Interaction Design Foundation Personas. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/personas? (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Interaction Design Foundation What Is Information Architecture (IA)? Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/information-architecture? (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Interaction Design Foundation What Is Usability Testing? Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/usability-testing (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Moran, K. Usability Testing 101.

- Soegaard, M. System Usability Scale for Data-Driven UX. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/system-usability-scale? (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Laubheimer Beyond the NPS: Measuring Perceived Usability with the SUS, NASA-TLX, and the Single Ease Question After Tasks and Usability Tests. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/measuring-perceived-usability/ (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Sauro, J. 5 Ways to Interpret a SUS Score. Available online: https://measuringu.com/interpret-sus-score/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Aetrex. Available online: https://www.aetrex.com/technology/tech-sizeright-mobile-app.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Volumental. Available online: https://volumental.com/volumental-mobile-scanning (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Zellerfeld. Available online: https://www.zellerfeld.com/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Nike. Available online: https://www.nike.com/pt/nike-by-you (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Design Italian Shoes (DIS). Available online: https://www.designitalianshoes.com/en/pages/how-it-works (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Acquarell Shoes. Available online: https://acquarellshoes.com (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Konrad User Persona Examples, Tips and Tools. Available online: https://www.konrad.com/research/user-persona (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Bruton, L. What Are UX Personas and What Are They Used For? Available online: https://www.uxdesigninstitute.com/blog/what-are-ux-personas/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Interaction Design Foundation What Are User Flows? Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/user-flows (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Interaction Design Foundation What Are Wireframes? Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/wireframe (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Martinez, T. User Workflows in UX Design. Available online: https://www.capicua.com/blog/user-workflow-ux-design (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Dam, R.F.; Siang, T.Y. Design Thinking: Get Started with Prototyping. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/design-thinking-get-started-with-prototyping (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Nielsen, J. Why You Only Need to Test with 5 Users. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/why-you-only-need-to-test-with-5-users/ (accessed on 4 November 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).