1. Introduction

Political scientists increasingly recognize cabinet reshuffles as a critical, though less examined, dimension of political instability (Laver, 1974; Browne et al., 1986; Kam et al., 2010; Fleischer & Seyfried, 2015). While extensive scholarship addresses government survival, the specific governance instability from frequent ministerial turnover remains understudied (Bright et al., 2015; Sasse et al., 2020; Helms & Vercesi, 2022a, 2022b). Scholars widely regard reshuffles as a core indicator of governmental instability, as each event triggers an adjustment period. This learning phase extends significantly when new ministers lack prior political or administrative experience (Dowding & Dumont, 2009; Kerby & Snagovsky, 2021; Belchior & Silveira, 2023; Nielsen & Hansen, 2024; Olar, 2025).

A common theoretical claim posits that presidential systems, with their executive decree powers, experience fewer reshuffles than parliamentary systems, where coalition dynamics necessitate frequent changes. Empirical evidence, however, challenges this view. Coalition cabinets are the norm in presidential democracies (Cheibub et al., 2004; Cheibub et al., 2014; Kellam, 2017; Chaisty et al., 2018). Presidents routinely negotiate with parties to sustain stability, using the distribution of ministerial portfolios as a key bargaining tool (Amorim Neto, 2006; Camerlo & Martínez-Gallardo, 2018; Albala, 2021). This reality demands continuous coalition management, with reshuffles serving as a primary mechanism for renegotiation (Hansen et al., 2013; Amorim Neto & Accorsi, 2022; Curtin et al., 2023; Mella Polanco, 2025). Consequently, reshuffles constitute a central governance instrument in both system types for resolving crises, realigning policy, and managing institutional constraints (Martínez-Gallardo, 2014; Franz & Codato, 2018).

The economic and administrative costs associated with frequent reshuffles are substantial. High ministerial turnover disrupts the implementation of government and donor-funded projects (Mele & Ongaro, 2014; Thomson et al., 2017; Palotti, Cavalcante & Gomes, 2019; Cohen, 2022). This disruption is particularly acute in technical portfolios, where steep learning curves delay progress (Izu & Motanda, 2015; Sieberer et al., 2021). For instance, Bedasso (2024) found that World Bank education projects implemented between 2000 and 2017 across 114 countries achieved greater success during periods of ministerial continuity. This finding underscores how leadership changes can derail time-sensitive initiatives, especially in weakly institutionalized settings where offices are highly personalized. Moreover, newly appointed ministers often face significant information asymmetries, requiring extended periods to overcome the informational monopolies of senior bureaucratic cadres (Huber, 1998; Adolino, 2021).

Cabinet reshuffles also affect financial markets. Studies reveal a strong positive correlation between political risk and sovereign bond spreads (Moser, 2007; Hansen & Zegarra, 2016; Muzindusi et al., 2025). For example, Moser (2007) demonstrated that reshuffles affecting the ministry of finance or economics in twelve Latin American countries (1992–2005) led to immediate increases in bond spreads due to uncertainty over economic policy and debt repayment. Similarly, Prasetia et al. (2017) analyzed the Indonesian capital market’s reaction to cabinet formation and reshuffles, examining abnormal returns and trading volume activity for 90 companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange and observing significant effects in specific sectors such as trade, services, and investment. Conversely, during financial crises, the appointment of technocrats—nonpartisan experts—has been shown to reduce bond yields, signaling a government’s commitment to fiscal responsibility (Alexiadou et al., 2022).

However, not all scholars view reshuffles as inherently detrimental (Martínez-Gallardo, 2014; Franz & Codato, 2018). Ministerial turnover can foster innovation, renewal, and accountability (Huber & Martínez-Gallardo, 2008). Leaders may strategically adjust cabinets to align ministers’ skills with portfolio needs, respond to scandals, or enhance electoral prospects (Dewan & Dowding, 2005; Dewan & Myatt, 2007; Dewan & Hortala-Vallve, 2011). From a Principal-Agent perspective, reshuffles can mitigate self-serving behavior by reducing agency costs and moral hazard (Indridason & Kam, 2008; Praça et al., 2012). In some cases, reshuffles create a “musical chairs” effect, preventing ministers from consolidating excessive power (Roessler, 2011). In autocratic systems, existing literature suggests that dictators prioritize personal safety over fostering expertise (Bueno de Mesquita et al., 2003; Egorov & Sonin, 2011). Woldense (2018) illustrates how dictators employ frequent rotations of officials—for example, in Ethiopia under Haile Selassie (1941–1974), where officials were moved approximately every three years—to prevent subordinates from forming cliques or alternative centers of power, thereby consolidating their authority. This dynamic is particularly evident in Sub-Saharan Africa, where informal patron-client relationships and neopatrimonial governance dominate political systems. In such contexts, ministerial appointments are often used to consolidate power, co-opt elites, balance ethnic interests, and preempt leadership challenges (Bratton & van de Walle, 1997; Hyden, 2006; Arriola, 2009; François, Rainer & Trebbi, 2015; Kieh, 2018). For instance, Kroeger (2020), using data on 94 authoritarian leaders from 37 African countries (1976–2010), found that ministerial stability varies by regime type: dominant-party regimes (e.g., Senegal, Zimbabwe) experience fewer reshuffles than personalist regimes (e.g., Burkina Faso, Chad).

Despite African presidents wielding exceptional formal power (Van Cranenburgh, 2008), few studies analyze how this power shapes cabinet design in the region. Reshuffles often serve immediate political survival, with presidents forming large, inclusive cabinets before elections to co-opt elites (Arriola, 2009; Arriola & Johnson, 2014; Omgba, Avom & Mignamissi, 2021). Ministers frequently act as ethnic proxies, channeling resources to their groups (Kramon & Posner, 2016; Levan & Assenov, 2016). Thus, political calculations—managing coalitions or appeasing constituencies—typically drive reshuffles more than performance (Roessler, 2011; Staronova & Rybář, 2021). While stability allows expertise development (Huber, 1998), excessive tenure risks entrenching patronage and corruption (Praça et al., 2012; Cruz & Keefer, 2015).

This presents a core governance dilemma: balancing the costs of instability against the risks of entrenchment. Where is the equilibrium point that maximizes economic performance? Our systematic analysis of 19 African presidential and semi-presidential systems (2006–2023) addresses this. Using a polynomial dynamic panel model and a hybrid estimation strategy—Polynomial GMM to control for endogeneity and LSDVC for small-sample robustness—we identify a consistent inverted U-shaped relationship between ministerial tenure and economic growth. The results demonstrate that while experience initially benefits the economy, prolonged tenure yields diminishing returns and increases the hazards of moral hazard and entrenchment.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Cabinet Stability, Multiple Principals, and the Presidential Dilemma

Cabinet formation in democratic systems functions as an inherently political exercise. Leaders allocate positions to secure support from diverse constituencies and distribute material and symbolic benefits to political allies (Carboni, 2023). From a game-theoretic perspective, a governing coalition represents a political equilibrium. Ministerial portfolios reflect a stable balance of power among coalition partners, an equilibrium that holds only while the underlying bargaining environment remains static (Dodd, 1976; Saalfeld, 2013). In multi-party coalitions, a failure to renegotiate this balance can prompt parties to withdraw from government—a frequent occurrence in presidential systems. Such exits often force the creation of entirely new coalitions rather than simple cabinet reshuffles (Martinez-Gallardo, 2012; Gonzalez-Bustamente, 2023).

In the presidential and semi-presidential systems of sub-Saharan Africa, this bargaining process revolves decisively around the presidency. Presidents command extensive formal policymaking powers and control over state resources and patronage networks (Prempeh, 2008; Kieh, 2018). They operate within hybrid governance structures that blend formal constitutional authority with informal patronage systems (Riedl, 2014). This concentration of power typifies neo-patrimonial governance, where formal state institutions coexist with, and are often undermined by, personal rule and clientelism (Amorim Neto, 2006; François, Rainer, & Trebbi, 2015; Omgba, Avom, & Mignamissi, 2021). In such systems, formal authority and informal influence are deeply fused. Presidents exert power not only through constitutional mandates but also as central patrons within complex ethnic and political networks (Huber & Martinez-Gallardo, 2008; Thomson et al., 2017). Consequently, cabinet appointments primarily serve as instruments for informal power-sharing and elite co-optation, enabling presidents to align cabinet composition and hierarchy with their personal and political interests (Lindemann, 2008; Wigmore-Shepherd, 2019; Wehner & Mills, 2022; Steinert & Steinert, 2023).

The Principal-Agent (PA) framework provides a useful, though incomplete, lens for analyzing presidential delegation (Katz, 2014). While delegation in parliamentary systems flows linearly from the prime minister, ministers in presidential systems answer to multiple principals: the president, the legislature, party leaders, ethnic representatives, and informal networks (Martin & Vanberg, 2004; Moury, 2011). This multiplicity creates inherent policy divergence. Presidents, elected by a national electorate, must focus on broad national goals, whereas legislators and ministers often prioritize local or factional interests (Shugart, 1999; Ames, 2001; Calvo & Murillo, 2004; Lee, 2018). As a result, presidents confront both inter-party and intra-party agency loss, as coalition partners and individual ministers frequently advance their own agendas over collective government goals (Samuels & Shugart, 2010; Martinez-Gallardo & Schleiter, 2015).

Within Africa's multi-party coalitions, this delegation problem intensifies. Ministers must balance presidential directives against demands from competing principals who offer political protection, access to patronage, or electoral leverage (Bucur, 2017). This dynamic exacerbates agency loss. Ministers gain informational advantages through their control of bureaucratic networks, technical expertise, and relationships with civil servants and external actors (Martin & Vanberg, 2004; Cornell, 2014; Bersch, Lopez & Taylor, 2022). This information asymmetry allows them to pursue personal or factional goals that may conflict with presidential priorities.

To mitigate these delegation risks, parties and presidents often appoint junior ministers as monitoring mechanisms to enforce collective policy preferences (Pereira et al., 2017; Martinez-Gallardo & Schleiter, 2015; Thijm & Fernandes, 2024). However, this strategy has limits. Over time, junior ministers cultivate their own networks and may also engage in opportunistic behavior. Crucially, the electorate holds the president solely accountable for national outcomes (Samuels & Shugart, 2010). This accountability asymmetry—total presidential responsibility without full ministerial control—constitutes a core challenge of presidential governance.

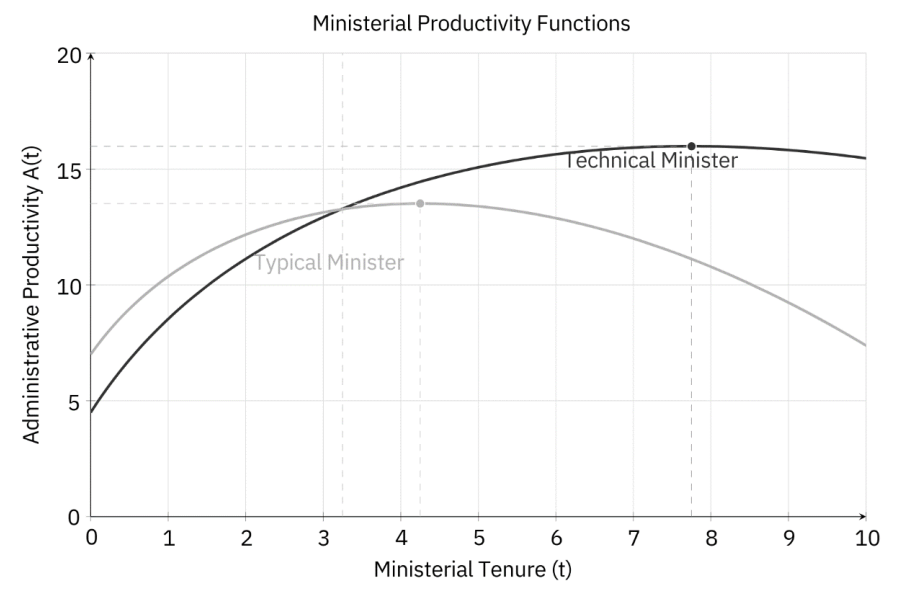

Effective cabinet management therefore requires balancing ministerial learning against the prevention of moral hazard. Ministerial productivity typically follows a three-phase curve:

Learning (Inexperience): New ministers often lack portfolio-specific technical knowledge, causing initial disruptions to decision-making and policy implementation. Structural portfolio changes, such as jurisdictional reconfigurations, exacerbate these disruptions (Huber, 1998). Productivity starts low but rises as ministers gain experience (Huber & Martinez-Gallardo, 2008).

Performance (Experience and Information Acquisition): As ministers acquire expertise, their productivity increases. Tenure stability facilitates effective policy execution and reduces information asymmetry, granting ministers greater command over bureaucratic knowledge (Stein & Tommasi, 2006; Cornell, 2014; Codato et al., 2018). In contexts such as Brazil, bureaucratic insulation ensures continuity despite political turnover (Lopes & Silva, 2020).

Moral Hazard (Patronage and Clientelism): Overly extended tenure can lead to bureaucratic inertia and moral hazard. Ministers may prioritize personal ambitions and patronage networks over presidential goals, lobbying for larger budgets to enhance their political capital rather than improve policy outputs (Praça et al., 2012). Frequent cabinet reshuffles can mitigate these risks by preventing ministers from consolidating power and entrenched patronage networks (Bueno de Mesquita, 2000). This dynamic is particularly evident in sub-Saharan Africa, where informal patron-client ties often overshadow formal institutions (Bratton & van de Walle, 1997; Hyden, 2006).

The trade-off between institutional efficiency and the risks of moral hazard defines the presidential dilemma. Frequent reshuffles reset the learning curve and prevent entrenchment but sacrifice accumulated expertise. Extended tenure builds deep expertise but increases the potential for opportunistic behavior.

A simplified ministerial productivity function can be expressed as:

Where:

A0 represents baseline administrative productivity prior to portfolio-specific expertise acquisition.

λ denotes the rate of experience acquisition

β reflects the moral hazard coefficient

αln(1+λt) captures learning accumulation with diminishing returns,

βt2 accounts for the rising moral hazard over time

The resulting productivity curves illustrate a strategic portfolio-specific insight. Typical ministers, often overseeing simpler portfolios, start with higher initial productivity but experience a steeper decline as moral hazard accelerates. Conversely, technical ministers begin with lower initial productivity due to portfolio complexity but achieve a higher performance peak and decline more gradually, given their deeper expertise. This suggests that optimal reshuffle timing should vary by minister type: more frequent rotation for typical ministers to capture their brief productivity peak, and longer tenure for technical ministers to maximize their sustained, high-level output.

In sum, effective presidential governance requires strategically navigating the competing demands of stability, accountability, and performance. By calibrating ministerial tenure and the timing of reshuffles, presidents can optimize government outcomes within the complex constraints of multi-principal delegation and neo-patrimonial systems.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Sample and Variables

We analyze an unbalanced panel dataset comprising 19 African presidential and semi-presidential systems from 2006 to 2023: Algeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Namibia, Niger, the Central African Republic, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Chad, Togo, Tunisia, and Uganda. We exclude Mozambique due to incomplete data.

We select these countries because their presidents and legislatures derive independent electoral legitimacy. This dual-legitimacy structure heightens principal-agent conflicts, making cabinet management—through coalition-building or cohabitation—a vital tool for political coordination (Cheibub et al., 2014). Prior research indicates that ministerial stability in such systems varies significantly with coalition structures, oversight mechanisms, and electoral timing (Helms and Vercesi, 2022b; Inácio, Llanos, & Pinheiro, 2022), factors essential for understanding how cabinet dynamics affect economic outcomes.

Dependent Variable

Economic Growth per Capita (Growth):

Our key performance metric is the annual percentage growth rate of GDP per capita, sourced from the World Development Indicators (WDI). We use this measure across all model specifications.

Core Explanatory Variables

Cabinet Reshuffles (Reshuffle):

This variable counts the number of ministerial reshuffle events in a given year, including both partial changes and full cabinet reorganizations. We code this variable primarily from official presidential decrees, executive gazettes, and verified media archives, conceptualizing reshuffles as events that disrupt policy continuity and signal political instability (Huber & Martínez-Gallardo, 2008; Indridason & Kam, 2008). For robustness, we also construct a binary Reshuffle Dummy that equals 1 for any year with at least one reshuffle event.

- Cabinet Duration (Duration):

This variable measures the number of months a cabinet remains in office before a change. It captures ministerial stability, which facilitates organizational learning and effective policy implementation (Berlinski, Dewan, & Dowding, 2007; Dewan & Myatt, 2010).

Control Variables

To account for structural, economic, and institutional factors influencing economic performance, the analysis includes the following controls:

-

Trade Openness: Computed as the average of exports and imports of goods and services

Source: World Development Indicators (WDI).

- Investment: Gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP, representing physical capital accumulation. Source: WDI.

- Schooling: Average years of schooling among the adult population, reflecting human capital development. Source: UNDP Human Development Indicators Database.

- Political Corruption: An index measuring corruption in political office, where higher values indicate lower corruption. Source: V-Dem Database (Coppedge et al., 2025).

- Industry Value Added: Industry Value Added as a percentage of GDP, representing the contribution of the secondary sector. Source: WDI.

- Neopatrimonialism Index: Measures the concentration of state power in personal patronage networks (V-Dem).

- Presidentialism Index: Captures the formal concentration of executive power (V-Dem).

2.3. Econometric Specification: Estimation Strategy and Robustness Tests

2.3.1. Model Specification

We estimate a polynomial dynamic panel model to capture the immediate effect of reshuffles and the non-linear impact of tenure:

Where:

Growthi,t: Real GDP growth rate for country i at time t

Growthi,t−1: Lagged growth (captures growth persistence and dynamic adjustment)

Reshufflei,t: measures the frequency of cabinet reshuffles throughout the year

Durationi,t: Duration of the cabinet in months

: Squared duration (captures potential nonlinear effects)

Xi,t: Vector of control variables (trade openness, FDI inflows, manufacturing value added, corruption control, education attainment)

μi: Country-specific fixed effects (unobserved heterogeneity)

εi,t: Idiosyncratic error term

We anticipate (reshuffles harm growth), (longer duration improves growth up to a point), and (beyond a threshold, diminishing or negative returns) implying an inverted U-shaped relationship.

To mitigate multicollinearity between cabinet duration and its square, the variable is mean-centered around 10.38 months. This transformation yields the centered variable

and the model specification becomes:

The marginal effect of cabinet duration on economic growth is therefore given by the partial derivative:

Where the optimal threshold is given by:

2.3.2. Estimation Approach: Polynomial GMM

To address endogeneity (e.g., poor growth potentially triggering reshuffles), we employ a Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimator. Standard estimators suffer from Nickell bias due to correlation between the lagged dependent variable and fixed effects. We apply a System GMM estimator (Blundell & Bond, 1998) enhanced with the non-linear moment conditions from Ahn and Schmidt (1995). This Polynomial GMM approach (Kripfganz, 2019) improves efficiency, which is crucial for reliably identifying the non-linear relationship within our sample. We estimate the model in first-differences to remove country-fixed effects (

):

The estimator relies on internal instruments, exploiting the assumption that lagged levels of the dependent and predetermined variables are orthogonal to future error terms in differences:

The system estimator combines this differenced equation with a levels equation that uses lagged differences as instruments. To prevent instrument proliferation—which can overfit endogenous components and weaken the Hansen test (Roodman, 2009)—we employ a "collapsed" instrument matrix and report robust, Windmeijer-corrected standard errors.

2.3.3. Monte Carlo Simulation Design

Given our relatively small panel (N=19, T=18), the asymptotic properties of the GMM estimator may not hold. To rigorously evaluate the finite-sample performance of our Polynomial GMM approach, we conduct a Monte Carlo simulation. This exercise assesses potential bias, quantifies estimation uncertainty—particularly for the non-linear terms—and tests the model's robustness under data-generating processes that mirror the high volatility typical of African macroeconomic data.

We calibrate the simulation to replicate our empirical model's core structure. The data-generating process (DGP) is:

We set the "true" parameter values (

,

,

,

,

) to match the robust estimates from our main GMM regression (Model 3 in

Table 1). We generate the error term

to be heteroskedastic and serially correlated, varying the autoregressive parameter

from 0.2 to 0.8 across a total of 7,000 replications (1,000 for each value of

) to test the estimator's sensitivity to different persistence levels.

For each simulated dataset, we re-estimate the model using our specified Polynomial GMM procedure. We then compute the following metrics across all replications to evaluate performance:

3. Results

3.1. Polynomial GMM Estimation Results

The coefficient for Cabinet Reshuffles is consistently negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. The estimate from our preferred specification (Model 3) of -1.703 indicates that each reshuffle event reduces annual GDP per capita growth by approximately 1.7 percentage points. This economically substantial effect highlights the significant short-term cost of political instability, likely stemming from abandoned policy initiatives, broken implementation chains, bureaucratic paralysis, and reset relationships with international donors.

The coefficients for Cabinet Duration reveal the anticipated non-linear relationship. The positive and statistically significant linear term (= 0.068) confirms that each additional month in office initially contributes to growth, aligning with the learning curve hypothesis. The negative sign on the quadratic term (= -0.00062) points to diminishing returns, consistent with a subsequent moral hazard phase where extended tenure may breed complacency or entrench corruption. Although the quadratic term is not individually significant at conventional levels (p ≈ 0.15), its consistent negative sign across specifications warrants further investigation.

Calculating the optimal tenure from Model 3, where the marginal effect of duration becomes zero, yields a point estimate of approximately 55 months:

However, given the statistical uncertainty around the quadratic term, this precise threshold should be interpreted with caution.

Among the control variables, Investment and Trade Openness show the expected positive and highly significant relationship with growth. The negative coefficient for Schooling is counterintuitive and may reflect a skills mismatch or data measurement issues. The negative coefficient for Industry Value Added could signal "Dutch Disease" dynamics in resource-dependent economies. The institutional variables (political corruption, neopatrimonialism, presidentialism) remain statistically insignificant in these GMM specifications.

Model Diagnostics

The specification tests largely support the validity of our GMM estimates. The Arellano-Bond test for AR(2) in first-differences is insignificant (p > 0.1), indicating no serial correlation in the error terms and thus validating the moment conditions. The Hansen J-test of overidentifying restrictions is also insignificant (p = 0.785), suggesting the instrument set as a whole is valid and exogenous. While the Sargan test is significant—potentially indicating instrument proliferation—the Hansen test is preferred due to its robustness to heteroscedasticity.

3.2. Monte Carlo Simulation and Robustness with LSDVC

The Monte Carlo simulation results, summarized in

Table 2, provide a nuanced assessment of our estimator's finite-sample properties.

The simulation reveals four principal insights:

1. The GMM estimator excels for large, stable effects. The coefficients for reshuffles, investment, and neopatrimonialism show minimal bias, low RMSE, and high confidence interval coverage. This confirms the robustness of our central finding on the economic cost of cabinet reshuffles.

2. Moderate effects show reasonable but sensitive estimates. Coefficients for duration, trade, and schooling exhibit low bias, but their precision deteriorates as serial correlation in the errors (φ) increases.

3. The lagged dependent variable is poorly estimated. This reflects a known limitation of dynamic panel GMM in small samples (Judson & Owen, 1999), where instruments for the lagged variable can be weak.

4. Non-linear terms have the lowest statistical efficiency. The squared duration term is particularly challenging to estimate precisely, as its low confidence interval coverage indicates. This confirms that while the inverted U-shape is a consistent feature of the data, the precise curvature and optimal tenure point come with substantial uncertainty.

To address these small-sample concerns—particularly regarding the dynamic and non-linear terms—we complement the GMM analysis with the bias-corrected Least Squares Dummy Variable estimator (LSDVC) proposed by Bruno (2005). Designed for dynamic panels with small N and moderate T, the LSDVC directly corrects for Nickell bias, offering a crucial robustness check.

Table 3 presents the results.

The LSDVC estimates provide strong, complementary evidence for our theoretical model. The coefficient for Cabinet Reshuffles remains negative, significant, and increases in magnitude (approximately -2.07 to -2.91), reinforcing the substantial economic cost of political turnover.

Critically, the LSDVC results offer much stronger evidence for the inverted U-shaped relationship. Both the linear and quadratic terms for Cabinet Duration are now highly significant (p < 0.01). Using the coefficients from Model (= 0.09527), (= -0.000918), we can calculate the optimal tenure more reliably.

The marginal effect is given by:

Setting this to zero yields a growth-maximizing ministerial tenure of approximately 51.9 months. This period allows ministers to ascend the learning curve and leverage accumulated experience before the risks of moral hazard, policy stagnation, and entrenched patronage outweigh the benefits of continuity.

Furthermore, the highly significant institutional variables in the LSDVC specification (Neopatrimonialism and Presidentialism) underscore that political context profoundly shapes economic outcomes—a relationship the GMM estimator, reliant on internal instruments, was less equipped to identify.

In summary, our hybrid estimation strategy—using GMM to establish causal identification and LSDVC to verify robustness in a small sample—provides compelling and consistent evidence. The significant reshuffle effect and the inverted U-shaped tenure-performance relationship across both estimators greatly strengthen the validity of our core conclusion: cabinet stability is a critical determinant of economic performance.

4. Discussions

4.1. Theoretical Interpretation and Contextual Nuance

4.1.1. Learning Curves, Ministerial Effectiveness, and Heterogeneity

The inverted U-shaped relationship between cabinet duration and economic growth confirms the learning-curve hypothesis, although context critically moderates this effect. Our LSDVC estimates indicate that ministers require approximately 51.9 months (4.3 years) to master their portfolios, build cross-ethnic coalitions, and consolidate bureaucratic control (Bratton & van de Walle, 1997; Hyden, 2006). However, this learning process varies significantly across portfolios. Ministers in technically demanding roles, such as finance or health, face steeper and more prolonged learning curves than their counterparts in less complex portfolios like sports or culture.

Political context further shapes tenure. Dominant-party systems permit longer ministerial survival and greater policy consistency, whereas fragmented or post-conflict regimes experience frequent reshuffles to balance ethnic and coalitional interests (Arriola, 2009). Our cabinet-level data offer valuable macro insights but cannot capture these nuanced portfolio-specific and contextual differences—a key limitation that underscores an important avenue for future research.

The Impact of Reshuffles and Principal-Agent Dynamics in Personalized Systems

The significant negative effect of cabinet reshuffles underscores a severe Principal-Agent problem within Africa’s personalized presidencies. Each reshuffle disrupts policy implementation, damages relational capital, and signals instability to investors and bureaucracies, thereby extending the analytical framework of Huber and Martínez-Gallardo (2008) to the African context.

In these systems, the Principal-Agent relationship is intrinsically complex. Presidents appoint ministers not only to implement policy but also to manage elite rivalries and distribute patronage. Reshuffles often function as a direct political tool to weaken a minister’s growing power base or appease ethnic factions (Kroeger, 2020). This political maneuvering, however, carries a substantial economic cost: our estimates show that each reshuffle reduces annual economic growth by approximately 1.7 to 2.9 percentage points. This result highlights the fundamental tension between short-term political survival and long-term economic development.

Balancing Experience and Risks of Entrenchment

The inverted U-shaped curve reflects the core trade-off between experiential benefits and the risks of moral hazard. While ministers accumulate valuable expertise over time, prolonged tenure can lead to detrimental entrenchment. Ministers may become overly aligned with regulated industries, grow complacent, or prioritize consolidating personal patronage networks over advancing national policy goals.

Our findings point to an optimal tenure of roughly 4.3 years. Beyond this threshold, the risks of moral hazard eclipse the benefits of experience, challenging the assumption that indefinite stability is inherently beneficial. Instead, strategically planned rotations can inject fresh perspective and prevent institutional stagnation or corruption.

4.2. Methodological Insights

Our hybrid estimation approach, combining Polynomial GMM with LSDVC, yields robust and reliable results. The consistency of the reshuffle effect across estimators (-1.70 in GMM, -2.07 in LSDVC) strengthens confidence in our core finding. The LSDVC estimator, designed for small panels (N=19, T=18), more effectively captures the non-linear relationship, whereas GMM provides directionally accurate though less precise estimates due to finite-sample bias.

Monte Carlo simulations confirm the reliability of our approach, particularly for large, stable effects like the reshuffle coefficient. However, accurately estimating the lagged dependent variable and quadratic terms remains challenging. Acknowledging these methodological strengths and limitations enhances the credibility of our findings and provides a solid foundation for future research.

4.3. Policy Recommendations

Our findings offer actionable insights for executive governance:

1. Prioritize Continuity in Complex Portfolios: Presidents should avoid frequent reshuffles in technically demanding portfolios like finance or infrastructure. Ministers in these roles need time to complete the learning process and oversee long-term projects.

2. Adopt Differentiated Tenure Strategies: A uniform tenure policy is ineffective. Shorter tenures may be appropriate for less complex or corruption-prone portfolios, where the risk of moral hazard is higher.

3. Plan Strategic Rotations: Instead of reactive reshuffles driven by political pressures, governments should implement planned rotations based on optimal tenure estimates. Performance evaluations can guide decisions on whether to retain, rotate, or replace ministers.

4. Strengthen Bureaucratic Insulation: Building a professional, non-partisan civil service can reduce the negative impact of ministerial turnover by ensuring continuity in policy implementation.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study provides robust macro-level evidence, several limitations remain:

1. Portfolio-Specific Analysis: Future research should examine how learning curves and optimal tenures vary across different ministries, such as economic versus social portfolios.

2. Political Context: Incorporating variables like regime type, state fragility, and election timing could offer a deeper understanding of how political dynamics influence reshuffles.

3. Mixed-Methods Approaches: Qualitative case studies can uncover the mechanisms linking reshuffles to policy disruptions and project delays.

4. Broader Country Coverage: Expanding the dataset to include more countries and regions would improve the generalizability of findings and enable comparative analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes robust evidence that cabinet stability is a critical determinant of economic performance in African presidential systems. Analyzing dynamic panel data from 19 countries (2006–2023), we find that frequent cabinet reshuffles significantly impede growth, with each event reducing annual GDP per capita growth by approximately 1.7 to 2.9 percentage points. We further identify a non-linear, inverted U-shaped relationship between ministerial tenure and economic performance, with an optimal tenure of approximately 51.9 months (4.3 years). This point balances the advantages of accumulated experience against the risks of moral hazard and entrenchment.

Our findings illuminate the inherent tension between political imperatives and sound economic governance in personalized presidential systems. While reshuffles may serve immediate political goals—such as managing coalitions or ensuring ethnic representation—they impose substantial economic costs. Conversely, excessively prolonged tenures can diminish effectiveness by fostering patronage networks and policy inertia.

These results carry significant policy implications. To mitigate the economic costs of instability, executives should prioritize continuity in key positions, adopt differentiated tenure strategies aligned with our optimal threshold, and implement structured, performance-based rotation systems. Strengthening bureaucratic independence remains a crucial buffer against the disruptive effects of ministerial turnover.

Future research should investigate ministry-specific dynamics and employ qualitative methods to elucidate the precise mechanisms linking political instability to economic outcomes. Nonetheless, this study establishes a clear benchmark: fostering strategic cabinet stability is not merely a political consideration but a fundamental prerequisite for sustainable economic development.

Declaration Of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.