1. Introduction

The sudden cessation of cardiac activity outside a hospital setting, otherwise referred to as Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest (OHCA) frequently results in hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and lasting neurocognitive sequelae [

1,

2]. While survival rates have improved with advances in resuscitation and post-arrest care [

3,

4,

5,

6], cognitive outcomes remain heterogenous and incompletely characterized across populations.

Cognitive impairments are a prevalent consequence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), primarily resulting from hypoxic-ischemic brain injury sustained during the no-flow and low-flow phases of the arrest [

1,

2]. Deficits typically affect memory, language, and verbal fluency executive functioning, attention, and processing speed abilities essential for independence and daily functioning [

7,

8,

9], reflecting the vulnerability of the frontal and temporal-parietal areas associated with anterior, middle and posterior cerebral artery circulation to hypoxia [

1,

2]. Executive functions and working memory, regulated primarily by the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, are especially vulnerable to ischemic insults [

10]. Case and cohort studies have shown that such deficits can persist for months after cardiac arrest, especially among patients with delayed return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) or prolonged hypoxia [

11,

12].

These impairments affect return to work, social participation and resuming everyday responsibilities thus diminishing overall quality of life [

13,

14]. Psychological consequences such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, and emotional blunting often co-occur with cognitive-linguistic deficits and further affect social reintegration and well-being [

15,

16] underscoring the need for early screening and transdisciplinary management and rehabilitation.

The severity and extent of dysfunction following cardiac arrest vary widely among individuals, influenced by factors such as the quality and duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), time to ROSC, initial neurological presentation, and the application of targeted temperature management [

17]. These diverse outcomes underscore the complexity of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and its interplay with patient-specific variables. In light of this variability, early neuropsychological and language screening, coupled with timely initiation of rehabilitation, is essential to optimize recovery and mitigate long-term burdens on both healthcare systems and families [

18,

19].

While large cohort studies outline general cognitive linguistic patterns, detailed single case evaluations are essential for capturing individual profiles. By examining post-OHCA cognitive linguistic complexity and psychosocial trajectories in greater depth, treatment plans can be more precisely targeted. [

20,

21].

In this context, we present a detailed neuropsychological, language, and quality of life assessment of a 32-year-old, bidialectal Greek speaking Cypriot male evaluated six months after OHCA. Using standardized tests with Greek adaptations and qualitative analysis, we delineate domain specific weaknesses and preserved abilities, relate findings to suspected neural substrates, and consider functional implications for daily life. To our knowledge, this is the first detailed post OHCA cognitive linguistic characterization of a Cypriot patient, contributing data from an underrepresented population and highlighting the importance of culturally and linguistically tailored assessment to inform individualized rehabilitation.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case Report

The patient was a 32-year-old, right-handed, Greek-speaking male with 12 years of formal education. At the time of the OHCA, he was engaged to be married and employed in manual labor. His past medical history was notable for a post-traumatic epilepsy following a right-sided closed frontal head injury sustained in a bicycle fall at age 16. There were no reported long-term cognitive sequelae; however, the patient had been receiving long-term antiepileptic therapy. He had no known cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, obesity, and diabetes mellitus. Lifestyle history was notable for a 7-year smoking habit.

On the day of the event, the patient was found by family members lying on the ground with foamy oral secretions. He was unconscious, and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated, with an estimated downtime of approximately 8 minutes. Upon arrival, Emergency Medical Services (EMS) identified ventricular fibrillation; two DC shocks were delivered, resulting in return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). He was transferred to the Emergency Department (ED), where he experienced recurrent pulseless electrical activity (PEA). CPR was re-initiated, and ROSC was achieved after two cycles. The patient was subsequently intubated, mechanically ventilated, sedated, and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). The precise overall duration of cerebral hypoxia could not be reliably determined. It was reported that approximately one month prior to this event, the patient had discontinued his antiepileptic medication.

After 48 hours, he was successfully extubated and, given clinical stability, was transferred from the ICU to the general ward. Approximately one week into the admission, he developed agitation, disorganized behavior, and paranoid ideation. Following neurological consultation, an electroencephalogram (EEG) was performed, demonstrating intermittent generalized epileptiform discharges. Antiepileptic treatment was initiated with levetiracetam 500 mg twice daily, which was later switched to valproic acid 750 mg twice daily. In addition, following psychiatric consultation, olanzapine 5 mg twice daily was initiated.

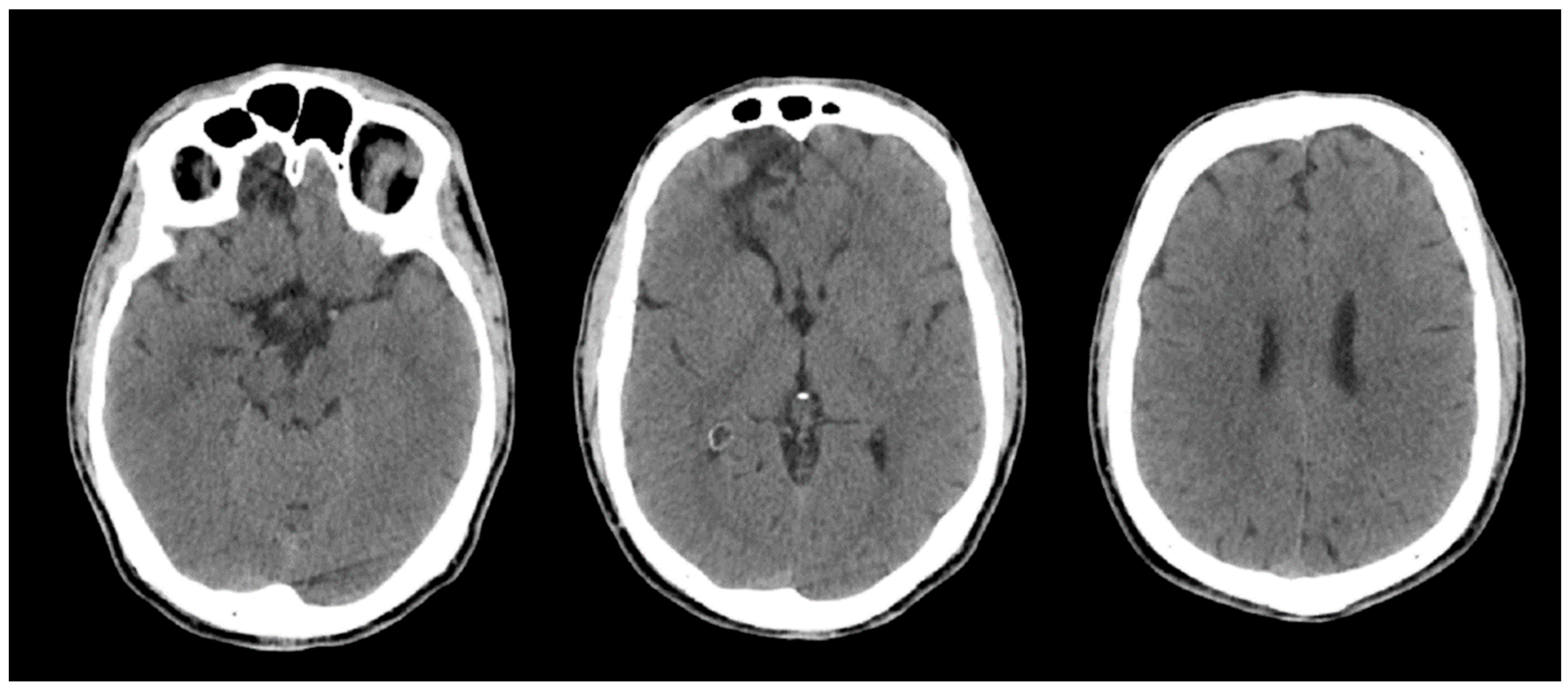

Brain CT performed on admission and repeated on hospital day 2 showed no intracranial haemorrhage or acute focal or global ischaemia, and no intracranial arterial occlusion without interval change. The known right frontal hypodensity, consistent with chronic gliosis following prior head trauma, was identified (

Figure 2). Brain MRI performed during the admission was significantly limited by motion artefacts; therefore, no additional diagnostic information could be obtained.

Transthoracic echocardiography performed during the admission demonstrated normal left ventricular systolic function. Holter monitoring and the discharge electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm without ST-segment or T-wave abnormalities. The patient also received physiotherapy and respiratory rehabilitation. No formal cognitive, language, or neuropsychological assessments were conducted during hospitalization.

The patient was discharged 17 days after the OHCA, haemodynamically stable and fully ambulatory. The aetiology of the cardiac arrest remained unclear. A seizure-related mechanism was considered in view of the patient’s history of structural epilepsy; however, a definitive causal relationship between epilepsy and the cardiac arrest could not be established; no motor seizures were observed during the hospital admission. Discharge planning included recommendations for close outpatient follow-up with cardiology, neurology, and psychiatry. An EEG performed externally three weeks after discharge demonstrated mild diffuse cerebral dysfunction, without epileptiform discharges.

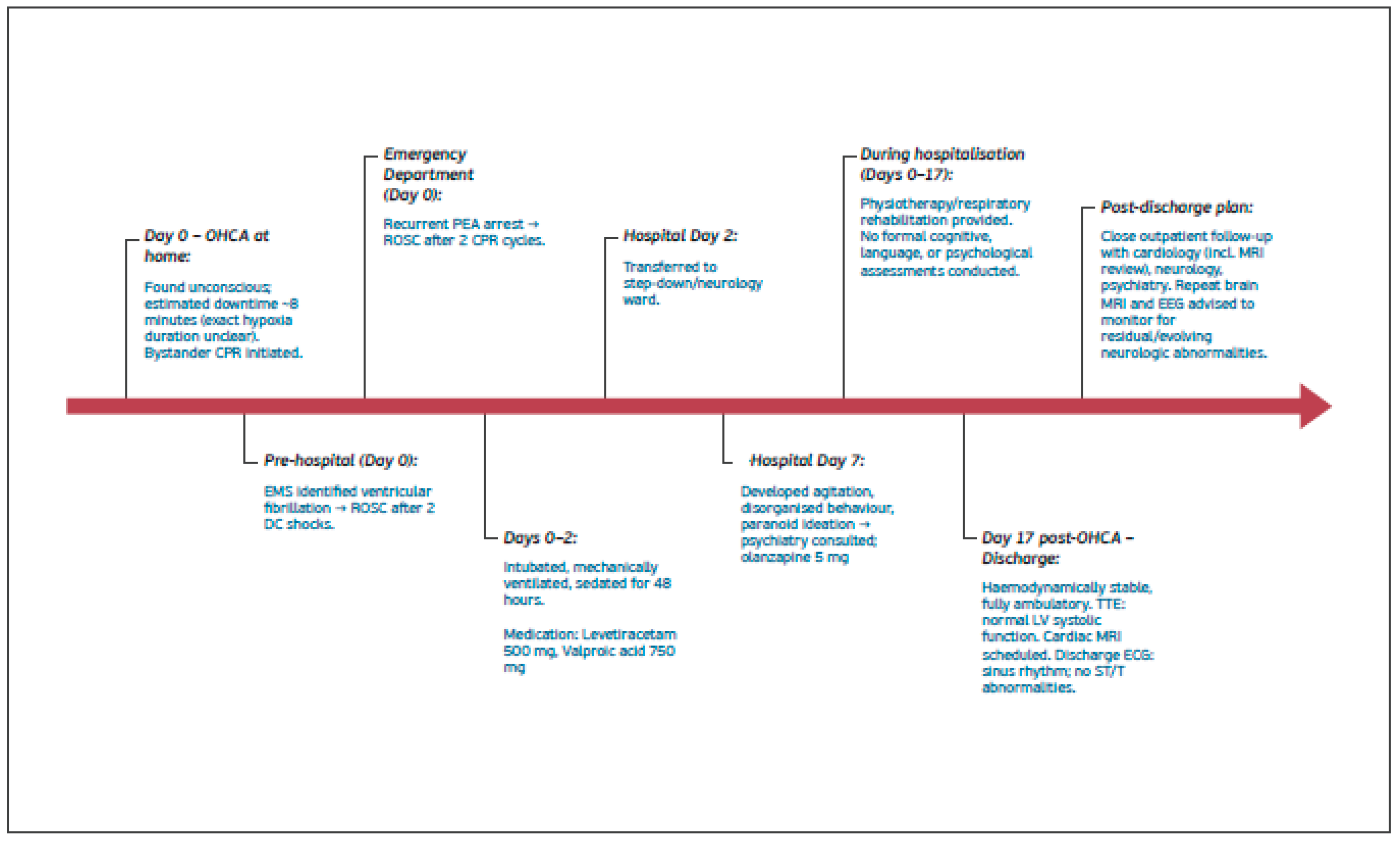

Figure 1.

summarizes clinical course, medical work-up, results and treatment.

Figure 1.

summarizes clinical course, medical work-up, results and treatment.

2.2. Investigations and Medical Work-Up During Hospital Stay

Imaging, electrophysiological, and cardiopulmonary investigations performed during the index hospitalisation are summarised in

Table 1.

Figure 2.

Non-contrast brain CT performed on admission following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Representative axial slices demonstrate preserved grey–white matter differentiation, including at the level of the basal ganglia, with no evidence of acute intracranial haemorrhage, mass effect, or diffuse cerebral oedema. A focal right frontal hypodensity consistent with chronic gliosis related to prior head trauma is noted.

Figure 2.

Non-contrast brain CT performed on admission following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Representative axial slices demonstrate preserved grey–white matter differentiation, including at the level of the basal ganglia, with no evidence of acute intracranial haemorrhage, mass effect, or diffuse cerebral oedema. A focal right frontal hypodensity consistent with chronic gliosis related to prior head trauma is noted.

3. Methods – Neuropsychological Assessment

3.1. Data Collection

Data collection began 6 months post-event and spanned four sessions. By this time, the patient had received no SLP/cognitive/OT therapy and had resumed full-time manual labor.

Neuropsychological testing was conducted in

Greek using quantitative and qualitative methods across

orientation, attention, memory, language, visuospatial processing, and

executive function. Performance was compared with

Greek-validated norms from standardized instruments and with estimates of

premorbid ability. Assessment was grounded in a

Luria’s systems framework [

22] and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework

(ICF) model [

23]. Additionally, the selection of test materials was based on assessment tools that have been systematically applied in research with Greek-Cypriot participants [

24,

25,

26,

27], ensuring cultural and linguistic appropriateness and alignment with evidencebased methodologies. Instruments are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Reporting Standards

This case report was prepared in accordance with the CARE (CAse REport) guidelines.

4. Results

4.1. Cognition

Orientation

The patient was assessed for orientation across temporal, spatial, and personal domains. He accurately identified the current month, year, and day of the week, but was unable to report the specific date, indicating a possible disruption in temporal continuity despite being in a structured (he had returned to his prior employment full time and resumed all social activities) and supportive environment. Orientation to person was intact; the patient was able to provide accurate autobiographical information, including place of birth, name of partner, and current occupation. Spatial orientation (e.g., city, district, and setting) were reported without any difficulties.

Attention

Attention was tested by administering the Digit Modality Test, Digit Span Forward, the Stroop Test and Trail A.

The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) [

40] presents a reference key pairing nine digits (1–9) with unique symbols; over 90 seconds, examinees transcribe the digit that corresponds to each randomly ordered symbol. Performance primarily indexes processing speed and sustained attention, with contributions from visuomotor/graphomotor integration. On this measure, the patient scored within 2 SDs below age-normative means, placing performance at the lower end of the normal range.

The Digit Span Forward task, which requires verbatim repetition of auditorily presented number sequences, assesses attention and immediate verbal recall [

32]. The patient’s performance was within 1.5 SDs below the normative mean, reflecting relatively low-average attention span.

The Stroop Color-Naming Task assesses cognitive control by requiring naming of the ink color of incongruent color words, indexing selective attention, processing speed, and inhibition [

41]. The patient’s score was within 2 SDs above the normative mean, corresponding to the slower end of the normal range. The Stroop Word-Reading condition, in which color words printed in black ink are read aloud to assess automatic word recognition and processing speed [

42], was 3 SDs above the mean, reflecting markedly slowed performance.

The Trail Making Test Part A, which requires rapid connection of numbered circles in ascending order to assess visual scanning, attention, and processing speed [

43], was within 1 SD below the normative mean, indicating performance within normal limits.

Table 2.

Summary of attention results.

Table 2.

Summary of attention results.

| Test |

Subtest / Component |

Deviation from Mean |

Interpretation |

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test |

— |

Within 2 SDs below mean |

Low average processing speed and/or attention |

| Digit Span |

Forward |

Within 1.5 SDs below mean |

Low average attention span |

| Stroop Test |

Color Naming |

Within 2 SDs above mean |

Low average |

| Stroop Test |

Word Reading |

Within 3 SDs above mean |

Moderate difficulty |

| Trail Making Test |

Part A |

Within 1 SD below mean |

Normal performance |

Memory

Memory was tested by administering the Digit Span Bakward, the Logical Memory Stories Test and the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test.

The Digit Span Backward task assesses working memory, particularly central executive functioning, by requiring repetition of number sequences in reverse order [

32]. Performance was within 1 SD below the mean, consistent with working memory within normal limits.

The Logical Memory Stories Test evaluates verbal episodic memory through immediate and delayed recall of short narrative stories, indexing encoding, retention, and retrieval [

32]. The patient’s immediate recall was 2 SDs below the mean for Story A (moderate difficulty) and 3 SDs below the mean for Story B (severe difficulty). On delayed recall, the patient was barely able to retrieve any information for Story A and unable to retrieve any information for Story B, indicating marked impairment in long-term retention.

The Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test assesses visuospatial construction and visual memory by having individuals copy a complex figure and later reproduce it from memory [

34]. Copy performance is reported under visuoconstruction; for the memory condition (immediate and delayed recall of the figure), the patient scored within 1 SD above the mean at both time points, indicating intact visual memory.

Table 3.

Summary of memory results.

Table 3.

Summary of memory results.

| Test |

Subtest / Component |

Deviation from Mean |

Interpretation |

| Digit Span |

Backward |

Within 1 SD below mean |

Normal performance |

| Logical Memory Stories Test |

Immediate Recall Story A |

2 SDs below mean |

Moderate difficulty |

| Logical Memory Stories Test |

Immediate Recall Story B |

3 SDs below mean |

Severe difficulty |

| Logical Memory Stories Test |

Delayed Recall Story A |

More than 3 SDs below mean |

Severe difficulty |

| Logical Memory Stories Test |

Delayed Recall Story B |

More than 3 SDs below mean |

Severe difficulty |

| Trail Making Test |

Part A |

Within 1 SD below mean |

Normal performance |

Executive Function

Executive function was assessed by administering the Trail Making Test Part B, the Stroop Interference Condition, the Semantic Verbal Fluency Task, as well as non-standardized tasks aiming to assess volition, planning, intentional action, and effective execution.

The Trail Making Test Part B, which requires alternating between numbers and letters in sequence to assess cognitive flexibility and set-shifting [

43], was within 2 SDs above the mean, placing performance at the slower end of the normal range. On the Stroop interference condition, requiring naming the ink color of incongruent color words, performance was >3 SDs above the mean, indicating severe difficulty with inhibitory control.

The Semantic Verbal Fluency Task assesses lexical access, semantic memory, and executive functioning by requiring individuals to generate as many words as possible from a given category, in this case it was animals, within 60 seconds [

44]. The patient’s performance on this test was within 3 SDs below the mean, indicating marked impairment in semantic verbal fluency.

Non-standardized tasks were also used to assess executive functions. Specifically, the aim was to further examine volition, planning, intentional action, and effective execution. A metalinguistic task required the patient to identify verbal similarities (e.g., “steam–cloud”) and interpret idioms, proverbs, and homophones, all of which target higher order language processing, conceptual reasoning, and mental flexibility. Across these tasks (similarities, homophone interpretation, idioms, and proverbs) the patient’s responses were simplistic, vague, lacked specific content, and were often irrelevant to the auditory stimulus.

Cognitive flexibility was further assessed through an alternative-object-use task (e.g., “How else could you use a screwdriver?”), in which responses were also vague, lacking detail, and produced with delayed response times indicative of lexical access difficulties.

A word-categorization task was used to assess cognitive flexibility, shifting, and inhibition. The patient was presented with two sets of nine words (high-frequency and low-frequency), each of which could be grouped either taxonomically or thematically. In the high-frequency set, he successfully categorized the words using both strategies, performing thematic grouping more easily and quickly. In contrast, he was unable to categorize the low-frequency words using either approach.

Volition was assessed through two personally relevant activities: “Vacation Planning” and “Wedding Ceremony.” Although the patient identified some basic steps for each, his descriptions were incomplete, lacked coherence, and he repeatedly stated, “I don’t know what else is needed.”

Table 4.

Summary of executive function results.

Table 4.

Summary of executive function results.

| Task |

Domain assessed |

Performance summary |

Interpretation |

| Trail Making Test – Part B |

Cognitive flexibility; task switching |

Within 2 SDs above mean |

Slower end of normal range |

| Stroop Test – Interference |

Inhibitory control; selective attention |

>3 SD above mean |

Severe difficulty |

| Verbal Fluency |

Initiation; strategy use; inhibition; cognitive flexibility |

Within 3 SDs below mean |

Moderate difficulty |

| Metalinguistic Similarities Task |

Abstraction |

Simple, vague, off-target responses |

Impaired conceptual abstraction |

| Idiom & Proverb Interpretation |

Higher-order language; abstract thinking |

Literal, simplistic responses |

Poor figurative-language comprehension |

| Homophone Interpretation |

Lexical Ambiguity; Cognitive flexibility |

Irrelevant answers |

Impaired mental flexibility |

| Alternative Object Use |

Semantic Access; Divergent thinking; Inhibition |

Vague responses; limited ideas; lexical access difficulties |

Reduced creativity; poor lexical access |

| Word Categorization—High-frequency words |

Cognitive flexibility; Inhibition |

Correct thematic and taxonomic classification |

Preserved for familiar content |

| Word Categorization—Low-frequency words |

Cognitive flexibility; Inhibition |

Reduced accuracy; difficulty classifying less-familiar items |

Impaired for less familiar content |

| Volition |

Planning; initiation; intentionality |

Basic, incomplete planning |

Poor volitional and planning abilities |

4.2. Language

Comprehensive language assessment was conducted using the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination and associated subtests. On core measures of auditory comprehension, language expression, reading, and writing, the patient performed within 1 SD below the mean, indicating abilities in the average range.

However, more detailed tasks revealed selective but significant impairments. On the Boston Naming Test–Short Form, he scored 3 SDs below the mean, consistent with a severe confrontation naming deficit. Narrative discourse elicited using the Cookie Theft picture demonstrated marked discourse-level impairment: in spoken output he failed to convey the main theme and produced fragmented, poorly coherent descriptions, while in writing, despite legible handwriting, his narrative lacked key content words, showed syntactic weaknesses, and conveyed limited meaningful information. Notably, no phonemic or semantic paraphasias were observed in either modality.

4.3. Visuospatial Abilities

The Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure copy trial, a measure of visuoconstructive and broader visuospatial abilities (including attention to detail and spatial organization), was within 1 SD above the mean, indicating normal performance.

The Clock Drawing Test, which taps visuoperceptual/visuospatial skills as well as numerical knowledge, working memory, and executive functions [

45], showed that the patient accurately drew the clock face and placed the hands, but wrote only the numbers relevant to the target time.

4.4. Quality of Life and Patient Reported Outcomes and Mental Health

On the WHOQOL-BREF the patient obtained raw domain scores, 24 on Physical Health, 24 on Psychological Health, 14 on Social Relationships and 37 on Environment. When transformed to the 0-100 scale, these correspond to 60.7, 75.0, 91.7 and 90.6, respectively, indicating average physical health, good psychological health, and very high satisfaction with social relationships and environmental factors.

On the Beck Depression Inventory II [

38], the patient obtained a total score of 10, which falls within the non-depressed range (0-13), indicating absence of clinically significant depressive symptoms.

5. Discussion

This case study presents the neuropsychological profile of a Greek speaking Cypriot male, six months post OHCA. The assessment revealed a heterogeneous cognitive – linguistic profile characterized by pronounced executive and memory deficits with relatively preserved visuospatial and affective functioning. This pattern reflects the complex interplay between hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and cognitive outcomes, a topic underexplored in Greek-speaking, bidialectal populations.

5.1. Cognitive Status

The patient was alert and cooperative, oriented to person and place but mildly disoriented to time, indicating some impairment in temporal orientation and a reduced functional sense of time. This finding aligns with the known early vulnerability of episodic memory systems to hypoxic damage [

9], [

46,

47]. Collateral information was obtained from the patient’s immediate family indicated significant difficulties in managing daily routines and adapting to unscheduled events, consistent with disrupted prospective memory and impaired temporal planning as well as maintaining routines that require flexibility and adjustment. These patterns further support the view that temporal disorientation often reflects underlying disruptions in memory encoding and attentional regulation [

45].

Overall performance across attention and processing speed measures was largely within normative limits, with scores clustering in the low-average range on speeded and attentionally demanding tasks. Relative inefficiency was most evident on tasks requiring rapid, automatic verbal responding, whereas simpler attention span measures were comparatively less affected. Collectively, this pattern suggests relative inefficiency in speeded and attentionally demanding tasks rather than a global attentional impairment, consistent with existing literature demonstrating the interdependence of attentional load, working memory, and executive functioning [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Such a pattern is frequently observed in cases of post-anoxic encephalopathy, where diffuse white matter damage can impair attentional networks [

52,

53].

Marked deficits were evident in verbal episodic memory, particularly in delayed recall tasks, where rapid forgetting suggested hippocampal dysfunction [

54]. In contrast, visuospatial memory performance on the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure was within normal limits, indicating relatively preserved right medial temporal and parietal systems [

54]. This dissociation between verbal and visual memory has been reported following cardiac arrest [

11]. The discrepancy between preserved digit span and impaired story recall further suggests executive contributions to encoding and retrieval inefficiency [

55]. While digit span relies primarily on short-term storage, story recall requires higher-level processes such as organizing information, integrating details, and inhibiting distractions. When these executive mechanisms are weakened, the individual may hold simple information briefly yet struggle to encode and retrieve more complex, meaningful material. Functionally, this may manifest as difficulty remembering conversations, multi-step instructions, or daily events, even though the person can recall short, discrete pieces of information without difficulty.

Executive functioning showed relative inefficiency on select standardized measures, including the Stroop Interference Task and verbal fluency, while set-shifting performance on the Trail Making Test Part B remained within normative limits. This dissociation may reflect the non-unitary nature of executive functioning, with relative preservation of externally guided set-shifting alongside deficits in inhibition and self-initiated verbal control.

Non-standardized assessments confirmed conceptual rigidity, poor abstraction, reduced cognitive flexibility, and impaired volitional planning, consistent with frontotemporal network dysfunction [

56,

57]. Interestingly, the patient was able to categorize high frequency words using both taxonomic and thematic strategies, suggesting that performance might vary in relation to the novelty, familiarity, or complexity of the stimuli, especially under conditions of reduced mental flexibility and inhibitory control [

58,

59].

5.2. Visual/Spatial Skills

Visuospatial and constructional abilities were largely preserved. On the Rey-Osterrieth Figure copy and Clock Drawing Test, the patient demonstrated accurate spatial organization. His omission of non-relevant clock numbers may reflect executive or attentional difficulties, rather than a primary constructional deficit.

5.3. Language

Language abilities appeared mildly compromised, with deficits primarily affecting lexical retrieval, narrative discourse, and semantic organization, despite the absence of classical aphasia. Language performance was variable: while basic auditory comprehension, verbal expression, and reading/writing skills were broadly preserved (within one standard deviation below the mean), marked impairments were observed in confrontation naming and narrative discourse. On the Boston Naming Test, the patient demonstrated significant word retrieval difficulties. Additionally, spontaneous narrative output, both oral and written, was notably disorganized, lacking cohesion and informativeness. This pattern suggests disruptions in lexical-semantic access and narrative construction, processes typically mediated by left temporal and frontal language regions [

18,

60,

61,

62]. The patient’s word retrieval failures were characterized by inconsistent access to lexical items, performance was context dependent and improved with semantic and phonemic cueing. These might imply that his naming impairments maybe better explained by executive dysfunction than by primary aphasia, suggesting preserved semantic representations but possibly inefficient retrieval strategies.

Narrative discourse was disorganized and tangential, consistent with dysexecutive processes affecting coherence and planning rather than primary linguistic deficits [

63,

64]. These deficits are consistent with findings in OHCA survivors, where language impairments are thought to arise not solely from primary language dysfunction but also from underlying executive deficits that compromise higher-order language organization [

63,

64]. Nevertheless, while the observed anomia is plausibly attributable to dysexecutive processes that disrupt efficient lexical access, a subtle compromise of the language network remains a possibility, particularly given evidence that OHCA survivors may present with mixed executive–language impairments [

65,

66].

5.4. Psychosocial Impact

Psychosocial measures indicated good emotional well-being and high satisfaction within social and environmental domains. The patient’s BDI-II score fell in the non-depressed range, suggesting preserved emotional resilience and adequate coping. However, lower physical health scores may reflect post OHCA cardiac fatigue or residual cardiorespiratory difficulties [

67]. This relatively positive affective profile aligns with evidence that, despite significant cognitive sequelae, many OHCA survivors report satisfactory quality of life [

68], even though mood disturbances are not uncommon, especially in younger patients with OHCA [

69,

70].

5.5. Limitations and Future Directions

This single-case design limits external validity and is vulnerable to bias and uncontrolled confounds [

71,

72]. Future work should combine detailed neuropsychological assessment with task-based fMRI to clarify whether word-retrieval difficulties are primarily executive or linguistic in origin and include additional memory subtests to delineate executive–memory interactions. Longitudinal studies with larger, more diverse Greek-speaking samples are needed to validate these preliminary findings. Moreover, longitudinal or randomized controlled trials should examine how integrated psychosocial and rehabilitation interventions affect long-term psychological well-being and quality of life in OHCA survivors [

73].

5.6. Clinical Implications

In our case, repeated brain CT scans showed no acute intracranial pathology. A single brain MRI was performed during the admission; however, image quality was significantly limited by motion artefacts and did not allow reliable assessment for subtle hypoxic–ischaemic injury. In survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, brain MRI abnormalities—when present—may include diffusion restriction in cortical and deep grey matter structures, involvement of the basal ganglia or hippocampi, and diffuse white matter changes, reflecting hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy [

74,

75]. Nevertheless, normal or near-normal findings on conventional brain MRI have also been reported after OHCA, even in patients who subsequently exhibit cognitive or neuropsychological impairment, indicating that the absence of overt structural abnormalities does not exclude clinically relevant brain injury [

76]. Such impairment is thought to reflect diffuse cerebral dysfunction that may not be readily captured by routine structural imaging and has been associated with adverse cognitive outcomes following cardiac arrest [

65,

76]. The electroencephalographic evidence of mild diffuse cerebral dysfunction observed in our patient represents a nonspecific finding and may reflect post-anoxic injury and/or the effects of centrally acting medications, including antipsychotic therapy [

77].

Consistent with this literature, the overall neurocognitive and linguistic profile, of this patient, reflects a mixed pattern of deficits that are consistent with hypoxic-ischemic injury, particularly affecting frontal and medial temporal brain regions. Severe impairments in verbal memory and executive functioning, contrasted with relatively preserved visuospatial and nonverbal memory, point toward a material-specific amnesia and dysexecutive syndrome, common in post-cardiac arrest encephalopathy [

78,

79]. The presence of conceptual and lexical rigidity, combined with planning and volition deficits, also raises concerns for functional independence and decision-making capacity, especially in contexts requiring future planning or abstract reasoning.

This profile underscores the importance of comprehensive, multidimensional neuropsychological assessment in the aftermath of cardiac arrest, as focal screening tools may underestimate the extent and complexity of cognitive dysfunction. Furthermore, these findings highlight the need for rehabilitation strategies that target both verbal memory encoding and executive control, while leveraging preserved visuospatial abilities to support compensatory interventions.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the need for systematic cognitive screening prior to discharge, followed by comprehensive neuropsychological and language assessment during follow-up, to adequately identify and address the cognitive-linguistic needs of OHCA survivors. It underscores the importance of integrating cardiac, neurological, neuropsychological, and speech-language pathology rehabilitation within a coordinated, ICF-aligned multidisciplinary framework that addresses impairments in body functions as well as communication, activity performance, and participation. Notably, this research makes a contribution to the field of speech-language pathology as the first to examine post OHCA cognitive function in a Cypriot patient who uses the standard Greek and the Greek-Cypriot dialect in his everyday activities. The methodology of this case study and detailed cognitive profiling provide a useful foundation for future research and the development of more targeted and systematic investigations into how cognitive deficits affect participation in meaningful activities and return to productive living in this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data analysis; writing - original draft preparation: M.C.D;. Writing: Major Review & Editing: A.C.; Review of medical history, interpretation of neuroimaging findings: T.T.; Writing, review & Editing: T.F.A, E.Y. C.T.; Data collection, curation & interpretation: A.L.; Methodology; Supervision; Writing: Review & Editing: F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (ΕΕΒΚ ΕΠ 2024.01.34).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the participant for the publication of the case details and of any potential identifiable images or data included in the article.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this case report is included in the manuscript. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors used ChatGPT to assist with refining the language of the manuscript and generating draft tables based on author-supplied data. All AI-generated material was reviewed, verified, and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the final content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests relevant to the submitted work.

References

- Cronberg, T., Greer, D. M., Lilja, G., Nolan, J. P., & Moulaert, V. R. Brain injury after cardiac arrest: Pathophysiology, treatment, and prognosis. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47 627–642.

- Sandroni, C., D’Arrigo, S., & Nolan, J. P. Prognostication after cardiac arrest. Crit. Care 2018, 22 150.

- Husain, S., & Eisenberg, M. Police AED programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2013, 84 1184-1191.

- Zijlstra, T. J., Leenman-Dekker, S. J., Oldenhuis, H. K., Bosveld, H. E., & Berendsen, A. J. Knowledge and preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a survey among older patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99 160-163.

- Myat, A., Song, K. J., & Rea, T. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: current concepts. The Lancet 2018, 391 970-979.

- Yan, S., Gan, Y., Jiang, N. et al. The global survival rate among adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2020, 24 61. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V. L., Borregaard, B., Mikkelsen, T. B., Tang, L. H., Nordström, E. B., Bruvik, S. M., Wieghorst, A., Zwisler, A. D., & Wagner, M. K. Observer-reported cognitive decline in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors and its association with long-term survivor and relative outcomes. Resuscitation 2024, 197 110162.

- Jaszke-Psonka, M., Piegza, M., Ścisło, P., Pudlo, R., Piegza, J., Badura-Brzoza, K., Leksowska, A., Hese, R. T., & Gorczyca, P. W. Cognitive impairment after sudden cardiac arrest. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol = Polish journal of cardio-thoracic surgery 2016, 13 393–398. [CrossRef]

- Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. A., Czyż-Szybenbejl, K., Kwiecień-Jaguś, K., & Lewandowska, K. Prediction of cognitive dysfunction after resuscitation–a systematic review. Adv. Interv. Cardiol./Postępy Kardiol. Interwencyjnej 2018, 14 225-232.

- Small, S. A., Schobel, S. A., Buxton, R. B., Witter, M. P., & Barnes, C. A. A pathophysiological framework of hippocampal dysfunction in ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12 585–601. [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, V. R. M., Verbunt, J. A., van Heugten, C. M., & Wade, D. T. Cognitive impairments in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review. Resuscitation 2009, 80 297–305.

- Geva, R., et al. Cognitive outcome and its neural correlates after cardiorespiratory arrest in childhood. Dev. Sci. 2024, 27 e13501.

- Nolan, J. P., Soar, J., Cariou, A., Cronberg, T., Moulaert, V. R., Deakin, C. D., ... & Sandroni, C. European resuscitation council and European society of intensive care medicine 2015 guidelines for post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2015, 41 2039-2056.

- Nolan, J. P., Sandroni, C., Böttiger, B. W., Cariou, A., Cronberg, T., Friberg, H., ... & Soar, J. European resuscitation council and European society of intensive care medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Resuscitation 2021, 161 220-269.

- Lilja, G., Nilsson, G., Nielsen, N., Friberg, H., Hassager, C., Koopmans, M., ... & Cronberg, T. (2015). Anxiety and depression among out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation 2015, 97 68-75.

- Evald, L., Skrifvars, M. B., Virta, J. J., Tiainen, M., Laitio, T., Leithner, C., Søreide, E., Hassager, C., Rasmussen, B., Grejs, A. M., Jeppesen, A. N., Kirkegaard, H., & Nielsen, J. F. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life 5-8 years after out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2025, 215 110672. [CrossRef]

- Bisht A, Gopinath A, Cheema AH, Chaludiya K, Khalid M, Nwosu M, Agyeman WY, Arcia Franchini AP. Targeted Temperature Management After Cardiac Arrest: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14 e29016. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29016. PMID: 36118997; PMCID: PMC9469750.

- Byron-Alhassan, A., Collins, B., Bedard, M., Quinlan, B., Le May, M., Duchesne, L., ... & Tulloch, H. E. Cognitive dysfunction after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Rate of impairment and clinical predictors. Resuscitation 2021, 165 154-160.

- Jensen, M. K., Christensen, J., Zarifkar, P., Thygesen, C. L., Wieghorst, A., Berg, S. K., Hassager, C., Stenbæk, D. S., & Wagner, M. K. Evaluating neurocognitive outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors: A comparative study of performance-based and reported measures. Resuscitation 2024, 202 Article 110310.

- Alexander, M. P., Lafleche, G., Schnyer, D., Lim, C., & Verfaellie, M. Cognitive and functional outcome after out of hospital cardiac arrest. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2011, 17 364-368.

- Phelps, M., Christensen, D. M., Gerds, T., Fosbøl, E., Torp-Pedersen, C., Schou, M., ... & Gislason, G. Cardiovascular comorbidities as predictors for severe COVID-19 infection or death. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2021, 7 172-180.

- Mikadze, Y. V., Ardila, A., & Akhutina, T. V. AR Luria’s approach to neuropsychological assessment and rehabilitation. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2019, 34 795-802.

- Tate,R.L., & Perdices,M. Applying the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to clinical practice and research in acquired brain impairment. Brain Impair. 2008, 9 282-292.

- Constantinidou, F. Effects of systematic categorization training on cognitive performance in healthy older adults and in adults with traumatic brain injury. Behav. Neurol. 2019,. [CrossRef]

- Constantinidou F, Prokopiou J, Nikou M, Papacostas S. Cognitive-Linguistic Performance and Quality of Life in Healthy Aging. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2015, 67 145-55. [CrossRef]

- Chadjikyprianou, A., Hadjivassiliou, M., Papacostas, S., & Constantinidou, F. The neurocognitive study for the aging: Longitudinal analysis on the contribution of sex, age, education and APOE ɛ4 on cognitive performance. Frontiers in Genetics 2021, 12 680531.

- Constantinidou F, Christodoulou M, Prokopiou J. The effects of age and education on executive functioning and oral naming performance in greek cypriot adults: the neurocognitive study for the aging. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2012, 64 187-98. [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K. N., Tsolaki, M., Chantzi, H., & Kazis, A. Mini-mental state examination (MMSE): A validation study in Greece. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2000, 15 342–345.

- Smith, V. L. Microeconomic systems as an experimental science. Am. Econ. Rev. 1982, 72 923-955.

- Zalonis, I., Christidi, F., Bonakis, A., Kararizou, E., Triantafyllou, N. Paraskevas, G., Kapaki, E., Vasilopoulos, D. The Stroop Effect in Greek Healthy Population: Normative Data for the Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test, Arch. Clin. Neuropsycho. 2009, 24 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Zalonis, I., Kararizou E, Triantafyllou NI, Kapaki E, Papageorgiou S, Sgouropoulos P, Vassilopoulos D. A normative study of the trail making test A and B in Greek adults. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2008, 22 842-50. [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. (1997) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3rd Edition, The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio.

- Constantinidou, F., & Ioannou, M. E. The effects of age and language on paragraph recall performance: Findings from a preliminary cross-sctional study. PSYCHOLOGY 2008, 15 342-361.

- Meyers, J. E., & Meyers, K. R. (1995). Rey Complex Figure Test and Recognition Trial: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Libon DJ, Swenson RA, Barnoski EJ, Sands LP. Clock drawing as an assessment tool for dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1993, 8 405-15. PMID: 14589710.

- Kosmidis, M. H., Vlahou, C. H., Panagiotaki, P., & Kiosseoglou, G. The verbal fluency task in the Greek population: Normative data, and clustering and switching strategies. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2004, 10 164-172.

- Goodglass, H., Kaplan, E., & Barresi, B. (2013). Διαγνωστική Εξέταση της Βοστώνης για την Aφασία [Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination]. In L. Messinis, E. Panagea, P. Papathanasopoulos, & A. A. Kastellakis (Scientific eds.). Patras, Greece: Gotsis Editions. ISBN 978-960-9427-36-4.

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck depression inventory.

- World Health Organization. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28 551-558.

- Smith, A. (1973). Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) manual. Western Psychological Services.

- Stroop, J. R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1935, 18 643–662. [CrossRef]

- Golden, C., Freshwater, S. M., & Golden, Z. (1978). Stroop color and word test.

- Reitan, R. M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept. Mot. Skills 1958, 8 271–276. [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M.D., Howieson, D.B., Bigler, E.D. and Tranel, D. (2012) Neuropsychological Assessment. 5th Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Lezak, M.D., Howieson, D.B., Loring, D.W. (1995). Neuropsychological Assessment (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Zhang H, Roman RJ, Fan F. Hippocampus is more susceptible to hypoxic injury: has the Rosetta Stone of regional variation in neurovascular coupling been deciphered? Geroscience 2021, 44 127-130. [CrossRef]

- Chareyron, L. J., Chong, W. K. K., Banks, T., Burgess, N., Saunders, R. C., & Vargha-Khadem, F. Anatomo-functional changes in neural substrates of cognitive memory in developmental amnesia: Insights from automated and manual Magnetic Resonance Imaging examinations. Hippocampus 2024, 34 645–658. [CrossRef]

- Heled, Y., Peled, A., Yanovich, R., Shargal, E., Pilz-Burstein, R., Epstein, Y., & Moran, D. S. Heat acclimation and performance in hypoxic conditions. Aviat Space Environ Med 2012, 83 649-653.

- Sohlberg, M. M., & Mateer, C. A. Effectiveness of an attention-training program. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1987, 9 117-130.

- Lambez, B., Vakil, E., Azouvi, P., & Vallat-Azouvi, C. Working memory multicomponent model outcomes in individuals with traumatic brain injury: Critical review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2024, 1-17.

- Kim, N., Jamison, K., Jaywant, A., Garetti, J., Blunt, E., RoyChoudhury, A., ... & Shah, S. A. (2023). Comparisons of electrophysiological markers of impaired executive attention after traumatic brain injury in healthy aging. Neuroimage 2023, 1. Epub 2023 Apr 30. PMID: 37191655; PMCID: PMC10286242. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Y., Hyun, S. E., & Oh, B. M. Rehabilitation for Impaired Attention in the Acute and Post-Acute Phase After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Review. Korean J Neurotrauma 2022, 19 20–31. [CrossRef]

- Gugger, J. J., Walter, A. E., Parker, D., Sinha, N., Morrison, J., Ware, J., ... & Diaz-Arrastia, R. Longitudinal abnormalities in white matter extracellular free water volume fraction and neuropsychological functioning in patients with traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2023, 40 683-692.

- Rempel-Clower, N. L., Zola, S. M., Squire, L. R., & Amaral, D. G. Three cases of enduring memory impairment after bilateral damage limited to the hippocampal formation. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16 5233-5255.

- Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. J. Development of working memory: Should the Pascual-Leone and the Baddeley and Hitch models be merged? J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2000, 77 128-137.

- Wawrzyniak M, Hoffstaedter F, Klingbeil J, Stockert A, Wrede K, et al. Fronto-temporal interactions are functionally relevant for semantic control in language processing. PLOS ONE 2017, 12 e0177753. [CrossRef]

- Leyhe, T., Saur, R., Eschweiler, G., & Milian, M. Impairment in Proverb Interpretation as an Executive Function Deficit in Patients with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and Early Alzheimer's Disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra. 2011, 1 51-61. 10.1159/000323864.

- Shebani Z, Patterson K, Nestor PJ, Diaz-de-Grenu LZ, Dawson K, & Pulvermüller F. Semantic word category processing in semantic dementia and posterior cortical atrophy. Cortex 2017, 93 92-106. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A. E. Patient arguments of causative verbs can be omitted: The role of information structure in argument distribution. Lang. Sci. 2001, 23 503-524.

- Levelt, W. J., Roelofs, A., & Meyer, A. S. A theory of lexical access in speech production. Behav Brain Sci. 1999, 22 1-38.

- Indefrey, P., & Levelt, W. J. (2004). The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition 2004, 92 101-144.

- Marini, A., Boewe, A., Caltagirone, C., & Carlomagno, S. Age-related differences in the production of textual descriptions. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2005, 34 439-463.

- Adrover-Roig, D., Sesé, A., Barceló, F., & Palmer, A. (2012). A latent variable approach to executive control in healthy ageing. Brain Cogn. 2012, 78 284-299.

- Crowther, J. E., & Martin, R. C. Lexical selection in the semantically blocked cyclic naming task: the role of cognitive control and learning. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8 9.

- Hagberg, G., Ihle-Hansen, H., Sandset, E. C., Jacobsen, D., Wimmer, H., & Ihle-Hansen, H. Long term cognitive function after cardiac arrest: A mini-review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14 885226.

- Goossens, P. H., & Moulaert, V. R. Cognitive impairments after cardiac arrest: implications for clinical daily practice. Resuscitation 2014, 85 A3–A4. [CrossRef]

- Geri, G., Dumas, F., Bonnetain, E., Bougouin, W., Champigneulle, B., Arnaout, M., … Cariou, A. Predictors of long-term functional outcome and health-related quality of life after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2017, 113 77–82. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K., Andrew, E., Lijovic, M., Nehme, Z., & Bernard, S. Quality of life and functional outcomes 12 months after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2015, 131 174–181. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Li, D., He, L., Yang, W., Dai, M., Lan, L., Diao, D., Zou, L., Yao, P., & Cao, Y. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in cardiac arrest survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2023, 83 8-19. [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, H., Lundqvist, C., Šaltytė Benth, J., Stavem, K., Andersen, G. Ø., Henriksen, J., Drægn, T., Sunde, K., & Nakstad, E. R. Health-related quality of life after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A five-year follow-up study. Resuscitation 2021, 161 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Yin, S., Ding, S. X., Xie, X., & Luo, H. A review on basic data-driven approaches for industrial process monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61 6418-6428.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14 532-550.

- Amacher, S. A., Bohren, C., Blatter, R., Becker, C., Beck, K., Mueller, J., Loretz, N., Gross, S., Tisljar, K., Sutter, R., Appenzeller-Herzog, C., Marsch, S., & Hunziker, S. Long-term survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiology 2022, 7 633-643.

- Keijzer, H. M., Verhulst, M. M. L. H., Meijer, F. J. A., Tonino, B. A. R., Bosch, F. H., Klijn, C. J. M., Hoedemaekers, C. W. E., & Hofmeijer, J. Prognosis after cardiac arrest: The additional value of DWI and FLAIR to EEG. Neuro-ICU 2022, 37 302–313. [CrossRef]

- Kang, C., Min, J. H., Park, J. S., You, Y., Jeong, W., Ahn, H. J., In, Y. N., Lee, I. H., Jeong, H. S., & Lee, B. K. (2023). Association of ultra-early diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging with neurological outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit. Care 2023, 27 16. [CrossRef]

- Choi, W. S., Kim, J. J., & Yang, H. J. Brain magnetic resonance imaging in patients with favorable outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Many have encephalopathy even with a good cerebral performance category score. Acute Crit. Care 2015, 30 265–271. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, P. W., & Rossetti, A. O. EEG patterns and imaging correlations in encephalopathy: Encephalopathy Part II. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2011, 28 233–251. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C., Alexander, M. P., LaFleche, G., Schnyer, D. M., & Verfaellie, M. The neurological and cognitive sequelae of cardiac arrest. Neurology 2004, 63 1774–1778.

- Brownlee, N. N., Wilson, F. C., Curran, D. B., Lyttle, N., & McCann, J. P. Neurocognitive outcomes in adults following cerebral hypoxia: A systematic literature review. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 47 83-97.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).