Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Summary

- The passenger lists dataset: ’CHUP_Passengerlists.csv’

2. Historical Background

2.1. State of Research

2.2. Overview of European and German Migration History in the 19th and 20th Centuries

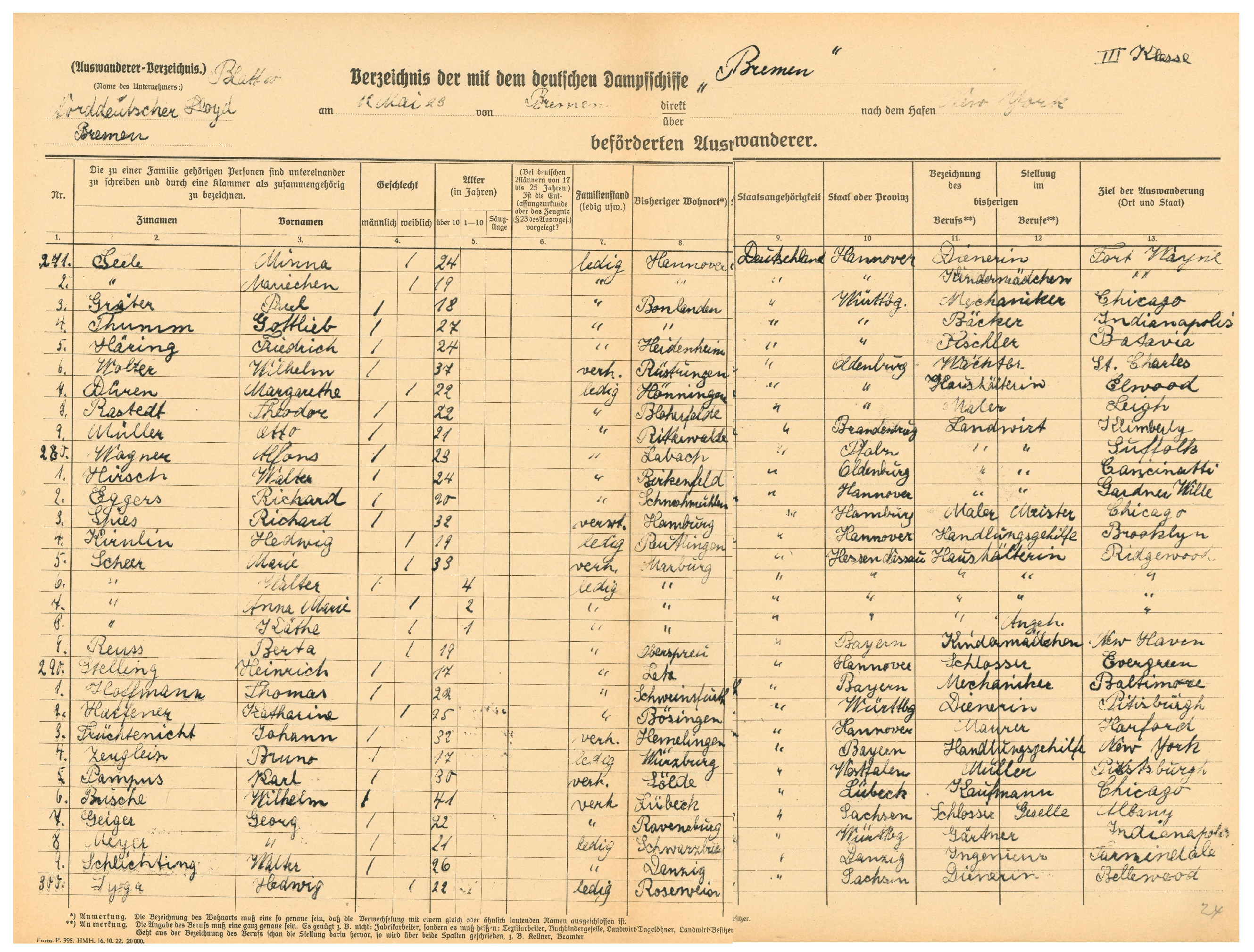

3. The Passenger Lists of Bremen Port: Archival Material and Structure

- surname and forename: free text

- gender: choice (male - female)

- age: three columns (over ten: fill in the age in numbers; 1-10; babies)

- discharge certificate (For German men up to the age of 25: has the discharge certificate (from military service) been submitted?): fill in as yes or no

- marital status: free text

- place of living hitherto: free text

- nationality: free text

- state or province: free text

- occupation hitherto: free text

- occupational position hitherto: free text

- destination (place and state): free text

4. Data Description

4.1. The Primary Dataset by the MAUS

- 1.

- Metadata: Contextual fields added during or after the transcription stage in order to manage, organize, or trace provenance. These columns help document and structure the dataset.

- 2.

- Passenger information: Person-level attributes such as name, age, gender, and nationality, along with other demographic details. These data enable research on migration trends and the social, cultural, and economic backgrounds of passengers.

- 3.

- Voyage details: Voyage-specific information such as departure date, ship name, and ports involved. These data support analyses of shipping routes and link temporal and geographical information to migration patterns.

4.2. Processing

4.3. Metadata

- Id: Assigns a unique ID to all entries in the database.

- archiv_ident: Contains the archival signature of the corresponding list.

- notes: Provides space for notes on duplicate passengers.

- pdf: Holds dates of departure for some voyages.

4.4. Data About the Passengers

-

age; age_cleaned:In the primary dataset, age was typically recorded as an integer. On rare occasions, dates of birth were given instead. Particularly for children, stating their ages in months instead of years was not uncommon. The result of the post-processing are integer age values for 96.8% of passengers. Figure 5 shows the age distribution in the cleaned age field, with the blue line indicating the mean across all valid entries (31.1 years). Figure 6 displays the yearly share of five age groups for the period of 1920-1939. Noticeably, two age groups of passengers 40-59 and 60+ years old gain significantly in their respective shares from 1930 on, indicating a upward shift in the age of passengers.

-

occupation; occupation_cleaned:The occupation column contains short occupational titles that describe the passengers’ professional status and position. The dataset holds normalised job titles for the most frequent 76% of all non-empty entries.

-

occupation_hisco:Provides unique numerical identifier for 93% of cleaned job titles based on the stanardised classification scheme ‚HISCO’[26].

-

occupation_sector:Contains numerical classifiers (0–9) based on the KldB2010 occupational classification scheme developed by the German Federal Employment Agency (’Bundesagentur für Arbeit’)[23]. Classifications were assigned to 91% of the cleaned job titles. Figure 7 summarizes the overall distribution: agriculture and education dominate, each accounting for roughly 30% of classified occupations, followed by production and manufacturing (19.8%) and commercial services (10.8%). Figure 8 traces sectoral affiliation of passengers from 1920 to 1940 in yearly shares. Three broad patterns emerge. First, traditional primary and industrial sectors contract over time: agriculture shows a clear downward trajectory from the early 1920s into the late 1930s, and production/manufacturing also declines steadily across the period. Second, several service and administrative fields expand: education/healthcare rises gradually; company organisation, accounting, law and administration grows from a small base; and commercial services increase modestly from the late 1920s onward. Third, smaller occupational domains remain limited in overall share but gain modest visibility in the mid- to late-1930s: the humanities, media, and arts exhibit brief upward fluctuations; transport and logistics records intermittent increases; the natural sciences rise from a near-zero baseline; and military employment shows a slight uptick at the close of the decade. Taken together, these trajectories suggest a gradual shift in the occupation of passengers away from agrarian and industrial work and toward education, public administration, and other service sectors over the interwar period.

-

occupation_training_level:Contains numerical classifiers (1–4) derived from the KldB2010 occupational classification scheme[23], capturing the typical qualification and task complexity associated with each occupation. Training-level categories were manually assigned to 91% of all non-empty job titles. Figure 9 summarises the distribution of training level classes. Two categories dominate almost equally: technically oriented occupations account for 44.2% of classified occupations, closely followed by helper and semi-skilled labour at 43.5%. More demanding profiles are far less common, with complex specialist activities comprising 7.3% and highly complex tasks 5.0%. Overall, the passenger sample is thus heavily concentrated in occupations requiring basic to intermediate training, while advanced or highly specialised roles remain a small minority. Figure 10 traces the annual shares of training levels from 1920 to 1940. Three main patterns stand out. First, helper and semi-skilled labour declines markedly over time: after occupying a substantial portion of the early 1920s passenger profile, its share falls steadily from the early 1930s onward, reaching only marginal levels in the late 1930s. Second, technically oriented activities move in the opposite direction. Despite fluctuations in the early 1920s, and the late 1930s respectivly, this category expands strongly, indicating a gradual shift toward more formally trained, technical work. Third, higher-qualification occupations increase moderately in this period, with complex specialist activities rising slowly from a low baseline and highly complex task increasing especially toward the late 1930s. These developments suggest an interwar transition among passengers away from low-skilled labour and toward more technical and specialist occupational profiles, with a modest but noticeable expansion of highly qualified roles.

-

gender; gender_cleaned:The gender column initially contained 13 unique and often flawed values. They were normalised to 3 specific values: ’m’ (male), ’w’ (female), ’uneindeutig’ (ambiguous). Figure 11 displays the gender distribution among passengers, with males (53.6%) slightly more represented than females (46.4%).

-

marital_status; marital_status_cleaned:Originally, this column contained 59 distinct values, which were standardised to six categories: ’ledig’ (single), ’verheiratet’ (married), ’geschieden’ (divorced), ’verwitwet’ (widowed), ’getrennt lebend’ (separated), and ’uneindeutig’ (ambiguous). Figure 12 presents the yearly distribution of passengers’ marital status between 1920 and 1940. Single and married passengers together account for the overwhelming majority of cases. Up to the early 1930s, single passengers are consistently more numerous than married ones; thereafter, the distribution shifts in favour of married passengers. This pattern is consistent with an increasing share of established families among emigrants in the years following the Nazi seizure of power. Widowed (3.7% of all passengers), divorced (0.4%), and separated (< 0.1%) individuals occur only rarely in the dataset.

-

religion; religion_cleaned:The religion of passengers was required to be specified from 1937 onward. The primary religion column contained 117 distinct values across 8914 total entries. These values include a large number of inconsistent abbreviations. We applied linguistic normalisation on orthography, expanded abbreviations, and harmonised lexical variants (e.g., ‘Islam’/‘Muslim’) — while keeping labels as close as possible to the original German terminology and without collapsing distinct denominations into broader categories. The normalised religion column holds 27 unique values. Table 3 shows the distribution of values in religion_cleaned. The three most frequent entries are ’mosaisch’ (jewish), ’katholisch’ (catholic) and ’evangelisch’ (protestant).

-

ethnicity; ethnicity_cleaned:The primary ethnicity field contained 350 distinct values indicating ethnic affiliation, including nouns, adjectives, and abbreviations. We standardised these entries to non-abbreviated German adjectives, staying as close as possible to the originals. Historical or obsolete affiliations present in the source were converted to adjectival forms without recoding to contemporary categories (e.g., ‘CSR’ → ‘tschechoslowakisch’, not ‘Czech’ or ‘Slovak’). For compound identifiers (e.g., ‘Deutsch-Russe’ (‘German-Russian’)) and negated forms (e.g., ‘nicht-arisch’ (‘non-Aryan’)), we retained both components and the hyphenation. The ethnicity_cleaned column contains 82 unique values.

-

nationality; nationality_cleaned:The nationality contained orthographic variants and 488 unique values. We standardised the column by de-abbreviating the nationality descriptors, transforming adjectives to nouns and translating english entries to german. The nationality_cleaned column now holds 97 distinct nationalities.

-

state_or_province; state_or_province_cleaned:This column contains information on the country or province of previous residence of the passengers and originally had 1761 distinct entries. After normalisation, the cleaned column holds 956 differing values.

4.5. Data About the Voyage

-

date_of_departure; date_of_departure_cleaned:In the primary database, this column contained departure dates in various formats including different spellings of month names, two-digit years, and typographical errors. To ensure consistency and ease of use, the dates were standardised to ISO-8601 format (YYYY-MM-DD).

-

port_of_departure; port_of_departure_cleaned:The original column contained 40 distinct entries that state the name of the city in which the port of departure is located. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of voyages started from the port in Bremen (98.86%). Sometimes the corresponding country was also entered. After processing, the column port_of_departure_cleaned now contains 17 distinct entries.In order to standardize the data and improve the usability of the data, we added three more columns:

-

port_of_departure_country:Contains the country in which the port of departure is located. For entries where this was not specified, we added it.

-

port_of_departure_LAT and port_of_departure_LON:These columns record the latitude and longitude of the cities of the departure ports in decimal degrees, georeferencing each record.

-

port_of_arrival; port_of_arrival_cleaned:The port of destination column (port_of_arrival) contained 338 distinct entries in the primary database, consisting of the name of the port and partly the country. As the entries contained orthographical mistakes and spelling variants, we used a matching-based process in order to merge these to 289 distinct entries in the column port_of_arrival_cleaned. In order to standardise the data and improve its usability, we added four more columns:

-

port_of_arrival_LAT; port_of_arrival_LON:These columns contain longitude and latitude geodata. Thus they enable map-based visualisations, e.g. Figure 13 , which shows the most frequent arrival ports plotted on a digitised historical map depicting the shipping routes of the Lloyd shipping company Bremen. The map was created by Paul Langhans and produced by Justus Perthes’ Geografische Anstalt in Gotha in the first decade of the 20th century. Georeferencing was performed in QGIS, an open-source geographic information system.

-

port_of_arrival_country:States the country in which the port of arrival is located. In some cases, the country of the arrival port was already provided in the primary database. We separated coun try and port city in these cases; if not given, we added the country information manually.

-

port_of_arrival_US_state:We also enriched the port data with information on the US-State of arrival, if the port was located in the United States. The majority (about 80%) of the passengers arrived at US-based ports, with more than 75% of them landing at the port of New York. The remaining entries indicate other arrival ports in South America, Canada, and Europe.

-

ship; ship_cleaned:The column ship in the primary database contained 519 distinct entries, including name variants of ships due to spelling mistakes. By correcting erroneous orthography, we merged the variants to 512 distinct entries in the column.ship_cleaned.

-

travel_class; travel_class_cleaned:In the primary database, the travel class was stated in 145 variants, e.g. ‘Klasse 2’, ‘2, Klasse’, ‘II. Klasse’, all meaning ‘2. Klasse’. By post-processing the column, we merged the variants to 16 distinct values, taking into account historical designations (see section 5.1.5.).

5. Methods

5.1. Data Processing

5.1.1. General Workflow

- 1.

- Extraction of Unique Values: For each target column, all unique values were first extracted from the original dataset to create a list of distinct entries.

- 2.

- Manual Orthographic Normalisation: Each unique entry in this extracted list was manually reviewed and corrected to merge spelling variants into standardised forms, remove extraneous whitespace, correct typographical errors and clearly mark ambiguous or missing entries according to the project guidelines.

- 3.

- Matching and Column Augmentation: The normalised values were then matched back to their original occurrences in the dataset. To preserve data integrity and traceability, original data was not overwritten. Rather, new columns were added to store these cleaned, standardised versions alongside the original entries.

5.1.2. Date Fields

5.1.3. Occupation Fields

5.1.4. Geographical Information

5.1.5. Travel Classes

5.1.6. Other Fields

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bickelmann, H. Deutsche Überseeauswanderung in der Weimarer Zeit; Franz Steiner Verlag: Wiesbaden, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeister, A. Familiengeschichtliche Quellen zur Auswanderung in Bremer Archiven . In Die MAUS (Gesellschaft für Familienforschung in Bremen);Genealogie und Auswanderung: Über Bremen in die Welt; Papierflieger Verlag: Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany, 2002; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Marschalck, P. Inventar der Quellen zur Geschichte der Wanderungen, besonders der Auswanderung, in Bremer Archiven; Selbstverlag des Staatsarchivs der Freien Hansestadt Bremen: Bremen, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bade, K. J. Historische Migrationsforschung. Eine autobiographische Perspektive . In Historical Social Research (GESIS); 2018; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte Beerbühl, M.; Rössler, H. Kaufleute und Zuckerbäcker: Zum Verhältnis von Migrations- und Familienforschung am Beispiel der deutschen Englandwanderung des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts. In Die MAUS (Gesellschaft für Familienforschung in Bremen);Genealogie und Auswanderung: Über Bremen in die Welt; Papierflieger Verlag: Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany, 2002; pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wesling, K. Über Bremen in die Welt: Die Bremer Passagierlisten 1920–1939 . In Die MAUS (Gesellschaft für Familienforschung in Bremen);Genealogie und Auswanderung: Über Bremen in die Welt; Papierflieger Verlag: Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany, 2002; pp. 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Die Maus (Gesellschaft für Familienforschung in Bremen), Handelskammer Bremen & Staatsarchiv Bremen Bremer Passagierlisten. 2024. Available online: https://passagierlisten.de/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Lumpe, Ch.; Lumpe, C. German emigration via Bremen in the Weimar Republic (1920–1932) . MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics, No. 53-2017, Philipps-University Marburg. 2017. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/174349 (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- Oltmer, J. Globale Migration: Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3rd ed.; C. H. Beck: München, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, J. D. European inter-continental emigration 1815–1914: Pattern and Causes . The Journal of European Economic History 1979, 8(3), 593–679. [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff, H. W. Das deutsche Auswanderungswesen . Dissertation, Göttingen, Georg-August University, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Bade, K. J. Migration in European History; Blackwell: Oxford, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, W. Crossings: The Great Transatlantic Migrations, 1870–1914; Indiana University Press: Indiana, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hatton, T. J.; Williamson, J. G. The Age of Mass Migration; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, R. L. Mass Migration under Sail: European Immigration to the Antebellum United States; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oltmer, J. Migration im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert; R. Oldenbourg: München, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Benscheidt, A.; Kube, A. Brücke nach Übersee: Auswanderung über Bremerhaven 1830–1974; Wirtschaftsverlag N. W: Bremerhaven, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bade, K. J. Europa in Bewegung: Migration vom späten 18. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart; C. H. Beck Verlag: München, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Oltmer, J. Migration steuern und verwalten. Deutschland vom späten 19. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart; Vandenhock & Ruprecht Verlage: Göttingen, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dölemeyer, B. Auswanderung . In Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte, Bd. 1., 2. Lieferung; Cordes, A., Ed.; 2008; pp. Sp. 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Verfassungen Deutschlands. Deutsches Reich (2018). Verfassungen der Welt. Available online: https://www.verfassungen.de/de67-18/verfassung71-i.htm (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Wilhelm, C. Auswanderung aus Bayern und Einwanderung in Nordamerika im Spiegel der Gesetze. In Good bye Bayern, Grüß Gott America: Auswanderung aus Bayern nach Amerika seit 1683; Katalogbuch zur Ausstellung; Hamm, M., Henker, M., Brockhoff, E., Eds.; Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte: Augsburg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit. Klassifikation der Berufe (KldB), 2nd ed.; 2020; Available online: https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/DE/Navigation/Grundlagen/Klassifikationen/Klassifikation-der-Berufe/KldB2010-Fassung2020/Onlineausgabe-KldB-2010-Fassung2020/Onlineausgabe-KldB-2010-Fassung2020-Nav.html (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Dahl, C. M.; Johansen, T.; Vedel, C. Breaking the HISCO Barrier: Automatic Occupational Standardisation with OccCANINE . arXiv.org. 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.13604 (accessed on 01 April 2025).

- GeoNames. (n.d.). GeoNames. Available online: https://www.geonames.org/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- International Institute of Social History (IISG). History of Work (HISCO) . 2002. Available online: https://iisg.amsterdam/en/data/data-websites/history-of-work (accessed on 01 April 2025).

- Imhof, A. E. Einführung in die historische Demographie; Beck: München, Germany, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Imhof, A. E. Lebenserwartungen in Deutschland vom 17. bis 19. Jahrhundert; VCH - Acta Humaniora: Weinheim, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, C. Bevölkerungsgeschichte und historische Demographie 1500–1800; Oldenbourg: München, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, C. Klimageschichte der Schweiz 1525–1860. Das Klima der Schweiz und seine Bedeutung in der Geschichte von Bevölkerung und Landwirtschaft (mehrbändig); Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 1984-1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, H. U. Die Auswanderung aus dem Knonauer Amt 1648–1750. Ihr Ausmass, ihre Strukturen und ihre Bedingungen; H. Rohr: Zürich, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, H. U. Swiss Migration to America in the 1730s. A Representative Family: The Pfister Family of Höri, Canton Zürich and the Feaster Family in America. Swiss-American Historical Society Review 2003, 39(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Imhof, H. Hoffnung auf ein besseres Leben. Auswanderer aus Wittgenstein nach Amerika im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert . In Regionales Werk; Heinrich Imhof: Bad Berleburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenstein, G. The Laws of Migration. Journal of the Statistical Society of London 1885, 48(2), 167–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Column Name | Data Type | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| id | int | Data entry identifier |

| archive_id | string | Archival identifier |

| agent | string | Carrier name |

| agent_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| date_of_departure | string | Date of departure |

| date_of_departure_cleaned | object | Departure date converted to ISO standard |

| sort_da | int | — |

| ship | string | Ship name |

| ship_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| port_of_departure | string | Port of departure |

| port_of_departure_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| port_of_departure_LAT | float | Latitude of departure port |

| port_of_departure_LON | float | Longitude of departure port |

| port_of_departure_country | string | Country of departure |

| port_of_arrival | string | Port of destination |

| port_of_arrival_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| port_of_arrival_LAT | float | Latitude of arrival port |

| port_of_arrival_LON | float | Longitude of arrival port |

| port_of_arrival_country | string | Country of destination |

| port_of_arrival_US_state | string | US-State of destination |

| captain | string | Captain of ship |

| travel_class | string | Travel class |

| travel_class_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| nr | object | Passenger number |

| last_name | string | Last name of passenger |

| first_name | string | First name of passenger |

| gender | string | Gender of passenger |

| gender_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| age | object | Age of passenger |

| age_cleaned | object | Dates of birth → numeric age (e.g. birth: 1878-11-15) |

| → age on 1939-02-25: 60 years | ||

| marital_status | string | Marital status of passenger |

| marital_status_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1832-04-16 to 1939-08-23 |

| previous_residence | string | Previous residence of passenger |

| nationality | string | Nationality / citizenship of passenger |

| nationality_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| state_or_province | string | State/province of previous residence |

| state_or_province_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| occupation | string | Occupation and professional position |

| occupation_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1830-03-24 to 1939-08-23 |

| occupation_hisco_nr | object | Numeric categorisation per HISCO schema |

| occupation_sector | int | Classification: sector of occupation |

| occupation_training_level | int | Classification: training/education level |

| emigration_destination | string | Destination of passenger |

| US_state | string | US-State of destination |

| US_state_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1853-08-09 to 1939-08-23 |

| notes | string | Remarks / Notes |

| emigrant | string | Passenger emigrant status |

| ethnicity | string | Ethnicity of passenger |

| ethnicity_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1935-08-10 to 1939-08-23 |

| religion | string | Religion of passenger |

| religion_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1937-01-16 to 1939-08-23 |

| literacy | string | Writing and reading ability of passenger |

| relative | string | Relatives of passenger |

| ticket | string | Valid ticket (y/n) |

| who_paid | string | Person paying for the ticket |

| amount_of_money | string | Amount of money passenger is carrying |

| previous_US_stay | string | Previous residence/stay on US territory |

| duration_of_stay | string | Duration of stay |

| duration_of_stay_cleaned | string | Timespan: 1832-04-16 to 1937-01-07 |

| place_of_stay | string | Place of stay |

| reference_person | string | Contact person |

| pfd | string | dates of departure for certain voyages |

| Column Name | Unambiguous | Distinct | Ambiguous | Missing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| id | 735,545 | 100.00% | 735,545 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| archive_id | 735,544 | 100.00% | 4,701 | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% |

| agent | 735,464 | 99.99% | 118 | 0 | 0.00% | 81 | 0.01% |

| agent_cleaned | 735,369 | 99.98% | 80 | 24 | 0.00% | 152 | 0.02% |

| date_of_departure | 735,543 | 100.00% | 2,330 | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% |

| date_of_departure_cleaned | 735,133 | 99.94% | 2,318 | 0 | 0.00% | 412 | 0.06% |

| sort_da | 735,545 | 100.00% | 2 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| ship | 735,542 | 100.00% | 519 | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.00% |

| ship_cleaned | 735,445 | 99.99% | 511 | 26 | 0.00% | 74 | 0.01% |

| port_of_departure | 733,683 | 99.75% | 40 | 0 | 0.00% | 1,862 | 0.25% |

| port_of_departure_cleaned | 732,777 | 99.62% | 17 | 0 | 0.00% | 2,768 | 0.38% |

| port_of_departure_LAT | 731,864 | 99.50% | 15 | 0 | 0.00% | 3,681 | 0.5% |

| port_of_departure_LON | 731,864 | 99.50% | 15 | 0 | 0.00% | 3,681 | 0.5% |

| port_of_departure_country | 731,865 | 99.50% | 10 | 0 | 0.00% | 3,680 | 0.5% |

| port_of_arrival | 735,091 | 99.94% | 338 | 0 | 0.00% | 454 | 0.06% |

| port_of_arrival_cleaned | 732,215 | 99.55% | 296 | 16 | 0.00% | 3,314 | 0.45% |

| port_of_arrival_LAT | 696,203 | 94.65% | 240 | 0 | 0.00% | 39,342 | 5.35% |

| port_of_arrival_LON | 696,203 | 94.65% | 240 | 0 | 0.00% | 39,342 | 5.35% |

| port_of_arrival_country | 732,331 | 99.56% | 123 | 16 | 0.00% | 3,198 | 0.43% |

| port_of_arrival_US_state | 587,201 | 79.83% | 11 | 0 | 0.00% | 148,344 | 20.17% |

| captain | 15,287 | 2.08% | 141 | 0 | 0.00% | 720,258 | 97.92% |

| travel_class | 624,957 | 84.97% | 145 | 0 | 0.00% | 110,588 | 15.03% |

| travel_class_cleaned | 624,852 | 84.95% | 14 | 105 | 0.01% | 110,588 | 15.03% |

| nr | 724,457 | 98.49% | 54,052 | 0 | 0.00% | 11,088 | 1.51% |

| last_name | 735,524 | 100.00% | 185,497 | 0 | 0.00% | 21 | 0.00% |

| first_name | 734,354 | 99.84% | 43,542 | 0 | 0.00% | 1,191 | 0.16% |

| gender | 725,528 | 98.64% | 14 | 0 | 0.00% | 10,017 | 1.36% |

| gender_cleaned | 725,447 | 98.63% | 2 | 10 | 0.00% | 10,088 | 1.37% |

| age | 714,556 | 97.15% | 15,492 | 0 | 0.00% | 20,989 | 2.85% |

| age_cleaned | 711,899 | 96.79% | 284 | 203 | 0.03% | 23,443 | 3.19% |

| marital_status | 619,515 | 84.23% | 57 | 0 | 0.00% | 116,030 | 15.77% |

| marital_status_cleaned | 619,461 | 84.22% | 5 | 54 | 0.01% | 116,030 | 15.77% |

| previous_residence | 547,056 | 74.37% | 99,264 | 0 | 0.00% | 188,489 | 25.63% |

| nationality | 717,455 | 97.54% | 487 | 0 | 0.00% | 18,090 | 2.46% |

| nationality_cleaned | 717,206 | 97.51% | 94 | 250 | 0.03% | 18,089 | 2.46% |

| state_or_province | 311,375 | 42.33% | 1,751 | 0 | 0.00% | 424,170 | 57.67% |

| state_or_province_cleaned | 311,342 | 42.33% | 955 | 33 | 0.00% | 424,170 | 57.67% |

| occupation | 428,318 | 58.23% | 10,559 | 0 | 0.00% | 307,227 | 41.77% |

| occupation_cleaned | 425,302 | 57.82% | 7,107 | 39 | 0.01% | 310,204 | 42.17% |

| occupation_hisco_nr | 399,603 | 54.33% | 251 | 0 | 0.00% | 335,942 | 45.67% |

| occupation_sector | 390,431 | 53.08% | 10 | 0 | 0.00% | 345,114 | 46.92% |

| occupation_training_level | 364,403 | 49.54% | 4 | 0 | 0.00% | 371,142 | 50.46% |

| emigration_destination | 703,728 | 95.67% | 35,092 | 0 | 0.00% | 31,817 | 4.33% |

| US_state | 516,322 | 70.20% | 151 | 0 | 0.00% | 219,223 | 29.8% |

| US_state_cleaned | 478,864 | 65.1% | 52 | 37,394 | 5.08% | 219,287 | 29.81% |

| notes | 24,069 | 3.27% | 8,866 | 0 | 0.00% | 711,476 | 96.73% |

| emigrant | 9,286 | 1.26% | 94 | 0 | 0.00% | 726,259 | 98.74% |

| ethnicity | 16,937 | 2.30% | 350 | 0 | 0.00% | 718,608 | 97.7% |

| ethnicity_cleaned | 16,925 | 2.3% | 80 | 11 | 0.00% | 718,609 | 97.7% |

| religion | 8,929 | 1.21% | 117 | 0 | 0.00% | 726,616 | 98.79% |

| religion_cleaned | 8,914 | 1.21% | 26 | 14 | 0.00% | 726,617 | 98.79% |

| literacy | 7,913 | 1.08% | 123 | 0 | 0.00% | 727,632 | 98.92% |

| relative | 8,098 | 1.10% | 7,556 | 0 | 0.00% | 727,447 | 98.9% |

| ticket | 7,567 | 1.03% | 11 | 0 | 0.00% | 727,978 | 98.97% |

| who_paid | 7,800 | 1.06% | 85 | 0 | 0.00% | 727,745 | 98.94% |

| amount_of_money | 5,599 | 0.76% | 138 | 0 | 0.00% | 729,946 | 99.24% |

| previous_US_stay | 7,196 | 0.98% | 7 | 0 | 0.00% | 728,349 | 99.02% |

| duration_of_stay | 5,689 | 0.77% | 846 | 0 | 0.00% | 729,856 | 99.23% |

| duration_of_stay_cleaned | 5,157 | 0.70% | 546 | 0 | 0.00% | 730,388 | 99.3% |

| place_of_stay | 4,113 | 0.56% | 625 | 0 | 0.00% | 731,432 | 99.44% |

| reference_person | 16,071 | 2.18% | 11,415 | 0 | 0.00% | 719,474 | 97.82% |

| pfd | 703 | 0.1% | 49 | 0 | 0.00% | 734,842 | 99.90% |

| Religion | Religion (German) | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Mosaic (Jewish) | mosaisch | 3,186 |

| Catholic | katholisch | 2,477 |

| Protestant | evangelisch | 1,936 |

| Roman Catholic | römisch-katholisch | 1,065 |

| Hebrew | hebräisch | 56 |

| Jewish | jüdisch | 49 |

| Greek Catholic | griechisch-katholisch | 27 |

| Greek Orthodox | griechisch-orthodox | 26 |

| Ambiguous / unclear | uneindeutig | 14 |

| Mohammedan (Muslim) | mohammedanisch | 13 |

| No information given | keine Angabe | 12 |

| Israelite | israelisch | 10 |

| Protestant | protestantisch | 10 |

| Lutheran | lutherisch | 9 |

| “Believer in God” | gottgläubig | 7 |

| None | ohne | 6 |

| Others | andere | 25 |

| Sum | 8,903 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).