1. Introduction

Mitochondria are a principal interface between steroid signaling and neuronal bioenergetics/redox control. Endogenous estrogens modulate respiratory chain efficiency, antioxidant defenses, and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) through both nuclear (ERα/ERβ) and extranuclear signaling, including rapid actions that converge on mitochondrial proteins and biogenesis programs; in healthy neural contexts, these effects tend to favor resilience and efficient energy use—the “healthy-cell bias” of estrogenic action [

1,

2]. In parallel, progesterone and synthetic progestogens regulate mitochondrial function, calcium handling, and pro-survival pathways via classical and membrane-associated receptors, supporting neurotrophic and neuroprotective outcomes across diverse CNS models [

3,

4].

Against this backdrop, combined oral contraceptives (COCs)—typically ethinylestradiol (EE) plus a progestin (e.g., dienogest, DNG)—introduce exogenous steroids that can reshape systemic redox balance and inflammatory tone. Multiple human studies report alterations in oxidative-stress biomarkers among COC users relative to non-users (e.g., hydroperoxides, antioxidant capacity, enzyme activities), though the direction and magnitude vary with formulation, dose, and physiology, highlighting the need for controlled cellular models to resolve mechanism and context [

5,

6,

7]. In neuronal-like systems, where mitochondrial function is tightly coupled to viability and signaling, parsing how exogenous EE/progestins interact with physiologic hormonal milieus is particularly germane.

The SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma line is a standard neuronal-like model to assay mitochondrial and oxidative endpoints, suitable for systematic interrogation of steroid effects under defined conditions [

8,

9]. For functional readouts, JC-1 yields a radiometric red/green signal proportional to ΔΨm, whereas H₂DCFDA/DCF provides a generic index of intracellular ROS; both are widely adopted when implemented with appropriate controls and awareness of probe caveats (e.g., dye loading/efflux, oxidation chemistry, and the necessity of orthogonal validation) [

10,

11,

12]. Beyond plate-reader assays, Mitotracker imaging coupled with quantitative morphometry (e.g., area, aspect ratio, form factor, perinuclear density) captures structural correlates of mitochondrial function, and QuPath provides an open, reproducible framework for high-throughput feature extraction and downstream statistics [

13,

14,

15].

Physiological follicular and luteal milieus differ chiefly in progesterone (low vs. high) with estradiol spanning lower-to-mid ranges across sub-phases; these fluctuations plausibly set distinct mitochondrial “set-points” in neural cells [

16,

17]. Emulating such backgrounds in vitro offers a principled way to test context-dependent actions of EE and progestins. Here we use SH-SY5Y cells to (i) establish follicular-like and luteal-like conditions with physiologically inspired E2/P4 combinations; (ii) overlay DNG/EE on each background and as a standalone exposure; and (iii) quantify ΔΨm (JC-1) and ROS (DCF) after 48 h, a window chosen to capture stabilized, transcriptionally integrated bioenergetic responses beyond acute dye or ion-flux artifacts. Within this framework, our expectation is that the E2/P4 milieu defines baseline ΔΨm/ROS states and that DNG/EE imposes background-dependent shifts at 48 h—directionality that we will subsequently connect to Mitotracker-based morphometry (via QuPath) to bridge functional readouts with structural phenotypes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell line and Culture Conditions

Cells. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells (Cytion; catalog/lot per supplier documentation) were maintained according to the Cytion technical datasheet.

Incubation. 37 °C, 5% CO₂, saturated humidity.

Starvation prior to treatment. 48 h in Cytion medium without FBS, supplemented with 1% ITS (insulin–transferrin–selenium), to minimize exogenous steroid interference and synchronize metabolic state. Cells were then exposed to test conditions for 48 h.

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatment Conditions

Six conditions were tested (F0–F5), emulating follicular-like and luteal-like hormonal milieus, with or without combined oral contraceptive (COC) steroids.

2.3. Plate Layout and Controls

Experiments were run on multi-well plates (96-well unless otherwise noted) following the “Piastre” map in the spreadsheet. Each condition included n = 8 technical replicates per plate. Controls included:

Vehicle (F0; “CTR”), on every plate.

Positive ROS control: H₂O₂ 100 μM for 60 min (plate-end spike) where indicated.

Antioxidant control: N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) 0.5 mM maintained throughout the 48 h exposure (where indicated).

ΔΨm depolarization control (for JC-1): CCCP/FCCP 50 μM for 5 min before reading; plates kept protected from light.

Table 1.

Nominal compositions (per well).

Table 1.

Nominal compositions (per well).

| Condition |

Progesterone (P4) [nM]* |

Estradiol (E2) [nM]* |

Dienogest (DNG) [nM]* |

Ethinylestradiol (EE) [nM]* |

Description |

| F0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Vehicle (control) |

| F1 |

1.87 |

0.28 |

0 |

0 |

Follicular-like background |

| F2 |

40.0 |

0.50 |

0 |

0 |

Luteal-like background |

| F3 |

1.87 |

0.28 |

160 |

0.30 |

F1 + DNG/EE |

| F4 |

40.0 |

0.50 |

160 |

0.30 |

F2 + DNG/EE |

| F5 |

0 |

0 |

160 |

0.30 |

DNG/EE only |

2.4. Fluorimetric Assays

All probes were handled under low light; identical exposure/gain settings were used across conditions on the same plate.

2.5. JC-1 (Mitochondrial Membrane Potential, ΔΨm)

Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with JC-1 at the manufacturer-recommended working concentration for 20–30 min at 37 °C. Fluorescence was read at:

Green (monomer): Ex 485–490 nm / Em ~530 nm

Red (aggregate): Ex 525–540 nm / Em 590–610 nm

The red/green ratio was used as the primary ΔΨm endpoint.

2.6. H₂DCFDA/DCF (ROS)

Cells were incubated with H₂DCFDA (typical 10–20 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C, washed, and read at Ex 485–495 nm / Em 525–535 nm. Where plate-end H₂O₂ spikes were used, readings were taken immediately after the 60 min incubation.

2.7. DAF-FM Diacetate (Nitric Oxide, NO)

After 48 h treatment, wells were washed and incubated with DAF-FM DA (per supplier’s instructions) for 30–45 min at 37 °C, followed by a de-esterification period in probe-free buffer (15–30 min). Fluorescence was read at Ex ~495 nm / Em ~515 nm.

2.8. Hoechst 33342 (Nuclear Content/Proportionality)

At the end of the 48 h exposure, nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (0.5–5 μg/mL) for 10–15 min at 37 °C, and read at Ex ~350–360 nm / Em ~460–470 nm. Integrated Hoechst signal per well was used both as a proxy for cell number/proliferation at 48 h and as a proportionality factor for normalization of functional readouts (DCF, JC-1 ratio).

2.9. Data Processing and Normalization

Raw plate data were exported to MATLAB for analysis. For each well:

Primary endpoints: JC-1 red/green ratio (ΔΨm), DCF (ROS), DAF-FM (NO), and Hoechst (nuclear signal).

Normalization: In addition to raw values, we report Hoechst-normalized endpoints to correct for cell-number bias:

2.10. Quality Control and Statistics

Data underwent visual QC and robust outlier handling (pre-specified rules; details/code in Supplementary). Unless distributions justified parametric tests, we used non-parametric approaches:

Across-condition comparisons: Kruskal–Wallis.

Pairwise contrasts (e.g., F1–F5 vs F0; F1 vs F2; background effects F3 vs F1, F4 vs F2): Mann–Whitney tests, with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR control (q = 0.05).

Effect sizes: median differences and rank-biserial correlation; 95% CIs by bootstrap where applicable.

All analyses were run in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick MA) with custom scripts (provided as Supplementary)

2.11. Reagents and Solutions

P4, E2, DNG, and EE were cell-culture grade; stocks were prepared in DMSO and diluted in medium to reach the final [units] indicated in the table (final DMSO ≤ 0.1% v/v). Probes: JC-1, H₂DCFDA, DAF-FM DA, and Hoechst 33342 (supplier and catalogue numbers to be listed in the Reagents subsection or Supplementary Table).

3. Results

3.1. Data Quality, Replicates, and Normalization

Across plates, each condition (F0–F5) included n = 8 technical replicates. After the pre-registered robust QC/outlier handling, effective replicate numbers per condition remained adequate for non-parametric inference (median n_clean ≈ 5; range 5–8). Hoechst 33342 integrated fluorescence at 48 h was used both as a proxy of cell number/proliferation and as a proportionality factor for functional readouts (DCF; JC-1 ratio). Normalization to Hoechst did not invert qualitative patterns observed in raw signals.

3.2. Proliferation (Hoechst 33342)

Hoechst fluorescence indicated modest, background-dependent differences in cell number at 48 h. Relative to vehicle (F0), follicular-like (F1) and luteal-like (F2) milieus showed only small changes in Hoechst signal; adding DNG/EE (F3, F4) or using DNG/EE alone (F5) did not produce large proliferation shifts. Consequently, Hoechst-normalized endpoints closely tracked raw effects, suggesting per-cell functional modulation rather than artifacts from varying cell numbers (Figure S1; Table S1).

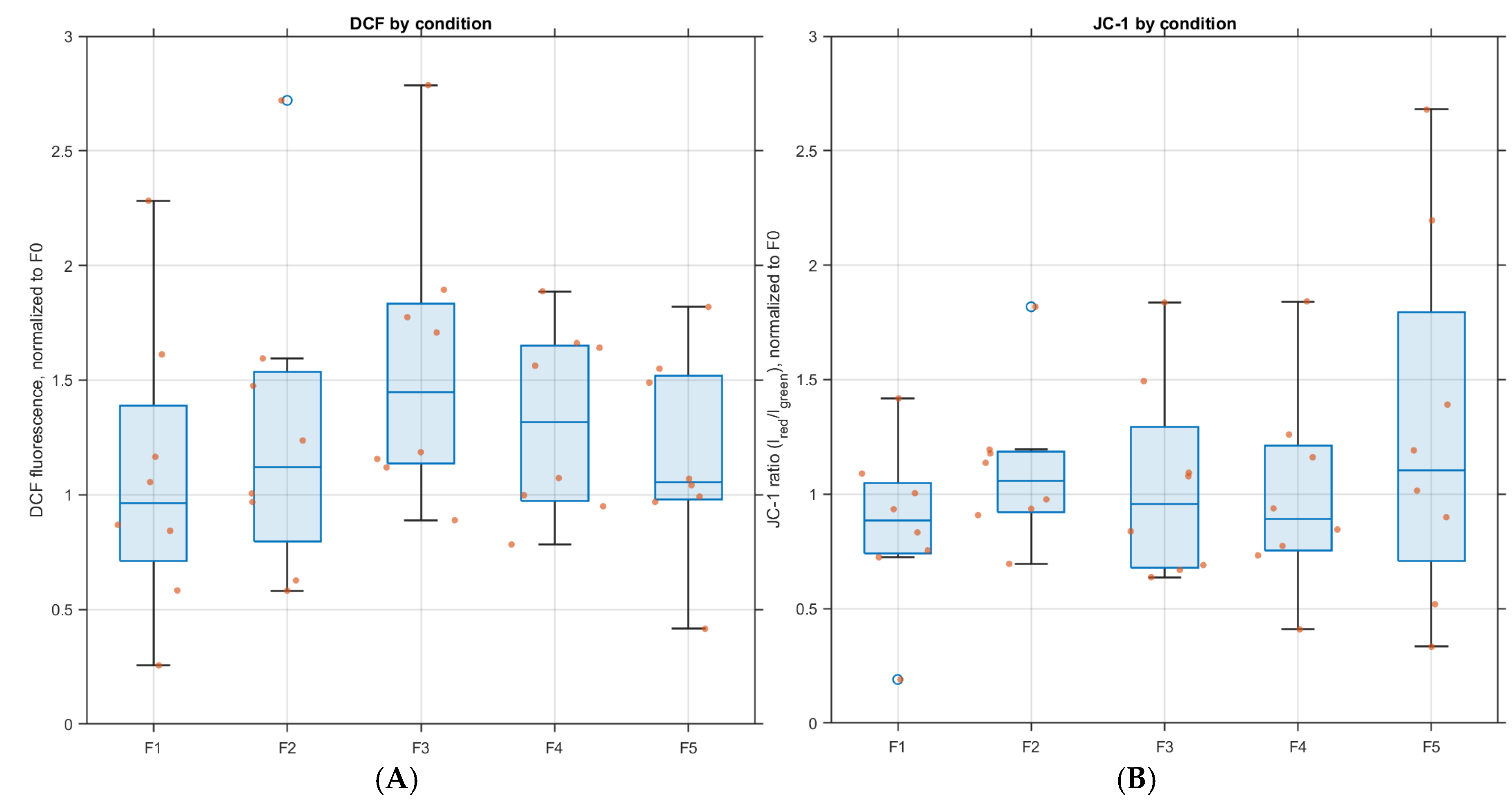

3.3. ROS (DCF)

DCF differed significantly across conditions (Kruskal–Wallis, FDR-controlled). Versus F0, F1–F5 showed higher DCF, with the largest increase in F3 (F1+ DNG/EE) and a marked elevation also in F4 (F2+ DNG/EE). F5 (DNG/EE alone) was elevated vs F0 but lower than phase-plus-COC conditions. These contrasts remained significant after Hoechst normalization (pairwise Mann–Whitney, FDR;

Figure 1A).

3.4. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (JC-1 Ratio)

The JC-1 red/green ratio showed a significant across-group effect (Kruskal–Wallis, FDR). Relative to F0, F1–F5 exhibited a decrease in JC-1 ratio (ΔΨm depolarization), most pronounced in F4 (luteal-like + DNG/EE) and substantial in F3 (follicular-like + DNG/EE). F5 showed a smaller but consistent decrease. Effects persisted after Hoechst normalization (pairwise Mann–Whitney, FDR;

Figure 1B).

3.5. Nitric Oxide (DAF-FM)

DAF-FM did not differ significantly across conditions (Kruskal–Wallis, n.s.), and no pairwise comparison vs F0 survived FDR correction. Thus, within 48 h, NO changes were not robust in this model under the tested exposures.

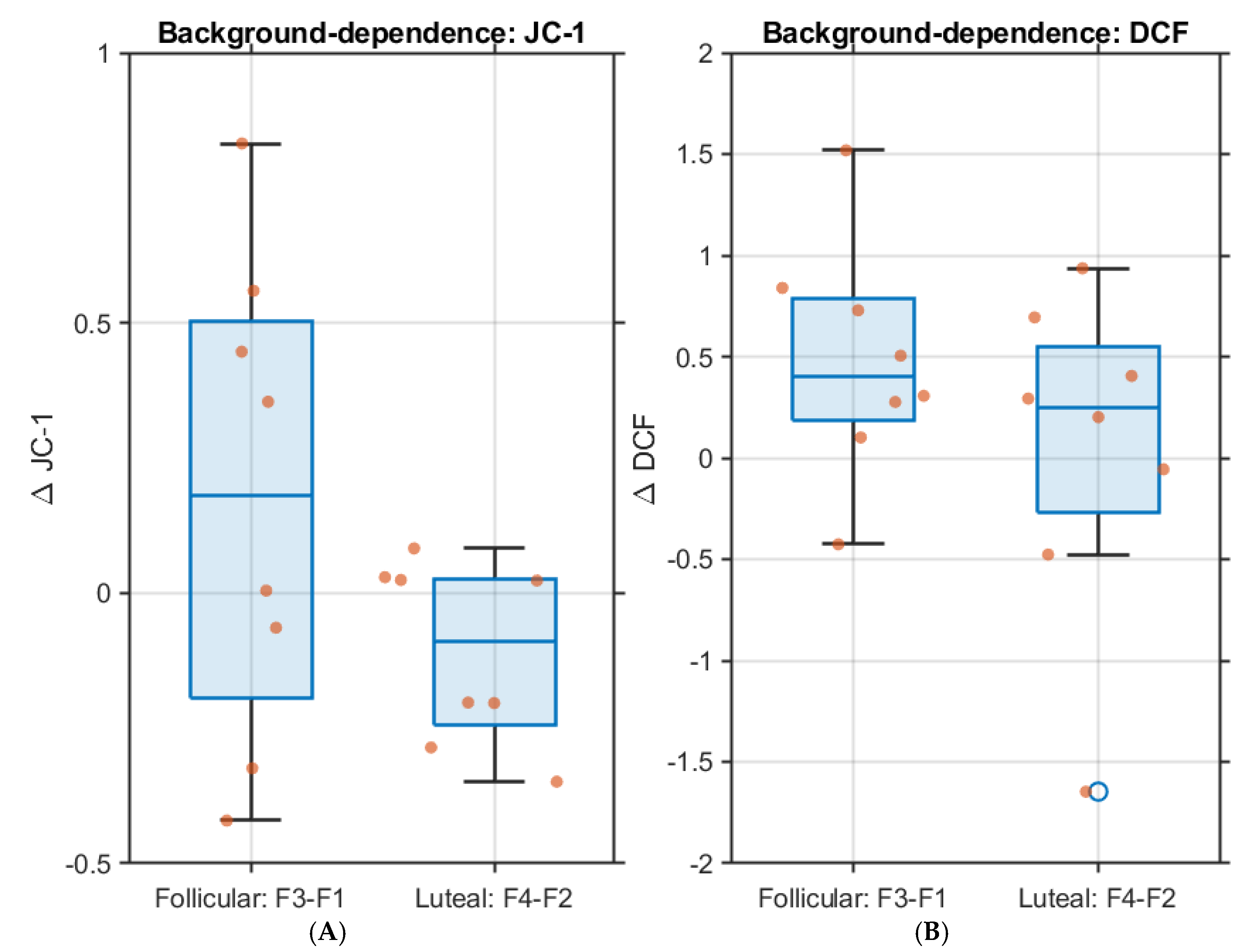

3.6. Background-Dependence (Follicular vs Luteal Milieus)

Comparisons of F3 vs F1 and F4 vs F2 support a background-dependent modulation by DNG/EE:

3.7. Sensitivity Analyses and Controls

Sensitivity analyses (with/without Hoechst normalization; with/without aggressive outlier trimming) did not change the direction of main effects. Where included, positive/negative controls behaved as expected (e.g., H₂O₂ increased DCF; CCCP/FCCP decreased JC-1 ratio), supporting assay validity.

4. Discussion

This preliminary study underscores the importance of neuro-endocrine background in shaping mitochondrial readouts in neuronal-like cells. Using SH-SY5Y cells exposed for 48 h to phase-inspired E2/P4 milieus with or without dienogest/ethinylestradiol (DNG/EE), we observed two consistent functional outcomes: (i) a significant rise in DCF (ROS) and (ii) a decrease in JC-1 red/green ratio (ΔΨm depolarization) relative to vehicle. These effects persisted even after Hoechst proportionality correction, indicating that changes reflect per-cell modulation rather than differences in cell number/proliferation at 48 h. By contrast, no significant differences emerged for DAF-FM (NO) following multiple-testing correction. The absence of NO changes can be interpreted in light of the fast, transient dynamics of nitric oxide and the well-documented methodological limitations of DAF probes (e.g., oxidant cross-reactivity and esterase dependence), which reduce sensitivity to subtle condition-specific fluctuations [

18,

19,

20].

The hormonal phase-like backgrounds modulated the magnitude and the direction of the responses. Adding DNG/EE on a follicular-like milieu (F3) produced the strongest ROS increase, whereas the luteal-like milieu with DNG/EE (F4) showed the most pronounced ΔΨm depolarization. These observations suggest that the E2/P4 set-point primes mitochondrial susceptibility, a concept consistent with growing evidence that sex steroids regulate mitochondrial bioenergetics, redox homeostasis, and vulnerability to metabolic stress [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Lower P4 in the follicular-like context may permissively amplify ROS, while higher P4 in the luteal-like condition may interact with progestin/estrogen signaling to bias ΔΨm shifts [

29,

30]. Although receptor engagement was not directly measured, the background-dependent outcomes align with modern models of steroid signaling that include ER/PR/GPER/mPR and direct mitochondrial receptor targets [

21,

31]. The dynamic role of sex hormones in neuronal mitochondrial function—including regulation of OXPHOS, antioxidant systems, and biogenesis—supports this interpretation [

25,

26,

27,

28,

32,

33].

Our assay validation strengthens confidence in these findings: H₂O₂ increased DCF as expected, and CCCP/FCCP decreased the JC-1 ratio, confirming mitochondrial sensitivity. Importantly, Hoechst-based additional proportionality affirmed that functional effects were not artifacts of altered cell number.

Still, several limitations need to be acknowledged: SH-SY5Ycells although neuron-like, do not exhibit the full complexity of mature neurons. We used a single exposure window (48 h); JC-1 and DCF have methodological constraints regarding specificity and quantitativeness (Yin et al., 2021). Likewise, we did not include orthogonal respiration or NO assays. These boundaries motivate the next experimental phase, which will incorporate Mitotracker-based morphometry (QuPath) to test structural correlates of ΔΨm/ROS trends, complemented—if desired—by orthogonal functional endpoints (e.g., TMRE/TMRM for ΔΨm, MitoSOX/Amplex assays for ROS subtypes) and time-course sampling to capture early NO transients.

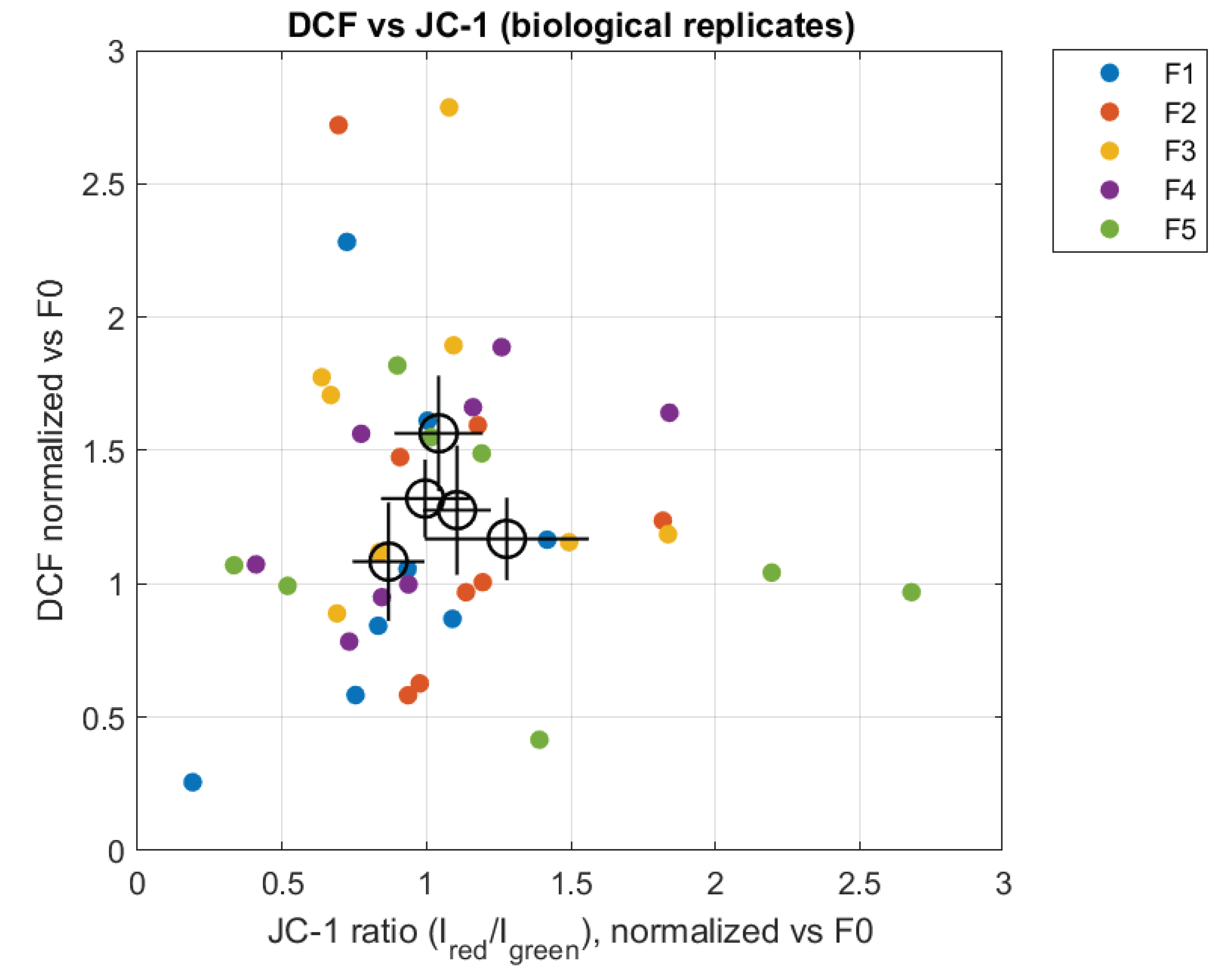

The joint analysis of JC-1 and DCF signals further supports the notion that oxidative stress and mitochondrial polarization represent partially independent outputs of the cellular response to the hormonal environment. As shown in Figure 3, similar JC-1 ratios can be associated with different levels of DCF fluorescence depending on the experimental condition, suggesting that the progestinic index modulates redox balance beyond its effects on mitochondrial membrane potential.

Figure 3.

Relationship between mitochondrial polarization (JC-1 ratio) and oxidative stress (DCF fluorescence). Individual points represent biological replicates, colored by experimental condition. Larger open symbols indicate condition means ± SEM, highlighting condition-specific relationships between the two readouts.

Figure 3.

Relationship between mitochondrial polarization (JC-1 ratio) and oxidative stress (DCF fluorescence). Individual points represent biological replicates, colored by experimental condition. Larger open symbols indicate condition means ± SEM, highlighting condition-specific relationships between the two readouts.

Overall, our findings support a framework in which physiological hormonal milieus (follicular vs luteal) establish distinct mitochondrial set-points, and COC-like steroids superimpose context-dependent alterations in ROS and ΔΨm at 48 h. This aligns with modern neuroendocrine-mitochondrial models positing that hormonal status is not a passive backdrop but an active determinant of mitochondrial responsiveness [

21,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. This integrated view (hormones × mitochondria × receptor signaling) has implications for understanding how menstrual cycle phase, hormonal therapies, and contraceptives may modulate neuronal resilience, redox state, and susceptibility to metabolic or oxidative stress.

From a translational perspective, these findings raise relevant questions: Do fluctuating steroid levels during the menstrual cycle alter neuronal mitochondrial vulnerability? Could long-term exposure to combined oral contraceptives reshape neuronal mitochondrial baseline states? Such questions require validation in more physiological systems—including primary neurons, brain organoids, and in vivo models—as well as functional endpoints involving neuronal survival, synaptic signaling, and plasticity. Recent work underscores how sex hormones influence CNS energy metabolism and oxidative pathways [

29,

30], supporting the relevance of hormonal context in mitochondrial research.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings show that E2/P4 hormonal milieus prime the mitochondrial state of SH-SY5Y cells, with follicular- and luteal-like backgrounds establishing distinct ΔΨm and ROS set-points at 48 h. Within these contexts, COC components exert background-dependent effects, as DNG/EE most strongly enhance ROS under follicular-like conditions while inducing the greatest ΔΨm depolarization in a luteal-like milieu. These outcomes reflect true per-cell changes rather than artifacts of cell number, given the preserved Hoechst proportionality of DCF/JC-1 signals and the minimal differences in proliferation. Conversely, NO levels did not show robust modulation at 48 h, as DAF-FM measurements revealed no significant between-group differences after FDR correction. Together, these results provide a rationale for follow-up image-based Mitotracker morphometry (QuPath) and complementary functional assays to link mitochondrial structural features with the observed shifts in ΔΨm and ROS.

Taken together, our results highlight the importance of the neuroendocrine context when evaluating the mitochondrial impact of combined oral-contraceptive steroids in neuronal-like cells and provide a standardized foundation for deeper mechanistic analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C. and S.A.; methodology, F.C.; software, G.A.; validation, F.C. and F.M.A.S.A.; formal analysis, F.C.; investigation, F.C.; resources, S.A. and S.D.F.; data curation, F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C. and S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.D.F.; supervision, S.D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Klinge, C.M. Estrogenic control of mitochondrial function. Redox Biol 2020, 31, 101435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, R.D. The healthy cell bias of estrogen action: mitochondrial bioenergetics and neurological implications. Trends Neurosci 2008, 31, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guennoun, R. Progesterone in the Brain: Hormone, Neurosteroid and Neuroprotectant. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassani, T.B.; Bartolomeo, C.S.; Oliveira, R.B.; Ureshino, R.P. Progestogen-Mediated Neuroprotection in Central Nervous System Disorders. Neuroendocrinology 2023, 113, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finco, A.; Belcaro, G.; Cesarone, M.R. Evaluation of oxidative stress after treatment with low estrogen contraceptive either alone or associated with specific antioxidant therapy. Contraception 2012, 85, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, K.; Milnerowicz, H. Pro/antioxidant status in young healthy women using oral contraceptives. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2016, 43, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K.M.; Roberts, L.; Cox, A.J.; Borg, D.N.; Pennell, E.N.; McKeating, D.R.; Fisher, J.J.; Perkins, A.V.; Minahan, C. Blood oxidative stress biomarkers in women: influence of oral contraception, exercise, and N-acetylcysteine. Eur J Appl Physiol 2022, 122, 1949–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xicoy, H.; Wieringa, B.; Martens, G.J. The SH-SY5Y cell line in Parkinson's disease research: a systematic review. Mol Neurodegener 2017, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, H.; Runesson, J.; Lundqvist, J.; Lindegren, H.; Axelsson, V.; Forsby, A. Neurofunctional endpoints assessed in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells for estimation of acute systemic toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2010, 245, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivandzade, F.; Bhalerao, A.; Cucullo, L. Analysis of the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Using the Cationic JC-1 Dye as a Sensitive Fluorescent Probe. Bio Protoc 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, B.; Darley-Usmar, V.; Davies, K.J.; Dennery, P.A.; Forman, H.J.; Grisham, M.B.; Mann, G.E.; Moore, K.; Roberts, L.J.; Ischiropoulos, H. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: challenges and limitations. Free Radic Biol Med 2012, 52, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.P.; Bayir, H.; Belousov, V.; Chang, C.J.; Davies, K.J.A.; Davies, M.J.; Dick, T.P.; Finkel, T.; Forman, H.J.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.; et al. Guidelines for measuring reactive oxygen species and oxidative damage in cells and in vivo. Nat Metab 2022, 4, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, M.P.; Maxwell, P.; Salto-Tellez, M. QuPath: The global impact of an open source digital pathology system. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2021, 19, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, L.G.; Bilik, S.M.; Burgess, J.L.; Catanuto, P.; Jozic, I.; Pastar, I.; Stone, R.C.; Tomic-Canic, M. An Optimized and Advanced Algorithm for the Quantification of Immunohistochemical Biomarkers in Keratinocytes. JID Innov 2024, 4, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anckaert, E.; Jank, A.; Petzold, J.; Rohsmann, F.; Paris, R.; Renggli, M.; Schönfeld, K.; Schiettecatte, J.; Kriner, M. Extensive monitoring of the natural menstrual cycle using the serum biomarkers estradiol, luteinizing hormone and progesterone. Pract Lab Med 2021, 25, e00211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usala, S.J.; Vineyard, D.D.; Kastis, M.; Trindade, A.A.; Gill, H.S. Comparison of Day-Specific Serum LH, Estradiol, and Progesterone with Mira. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huysseune, A.; Larsen, U.G.; Larionova, D.; Matthiesen, C.L.; Petersen, S.V.; Muller, M.; Witten, P.E. Bone Formation in Zebrafish: The Significance of DAF-FM DA Staining for Nitric Oxide Detection. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, S.M.; Nofallah, S.; Joshi, M.S.; Kavallieratos, K.; Tsoukias, N.M. Kinetic analysis of DAF-FM activation by NO: toward calibration of a NO-sensitive fluorescent dye. Nitric Oxide 2013, 28, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, D.; Baxter, B.; Campbell, B.C.V.; Carpenter, J.S.; Cognard, C.; Dippel, D.; Eesa, M.; Fischer, U.; Hausegger, K.; Hirsch, J.A.; et al. Multisociety Consensus Quality Improvement Revised Consensus Statement for Endovascular Therapy of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Int J Stroke 2018, 13, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaignard, P.; Liere, P.; Thérond, P.; Schumacher, M.; Slama, A.; Guennoun, R. Role of Sex Hormones on Brain Mitochondrial Function, with Special Reference to Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2017, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Luo, M.; Wang, R.; Ye, J.; Wang, X. Mitochondria in Sex Hormone-Induced Disorder of Energy Metabolism in Males and Females. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 749451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.S.; Schultz, L.; Hsu, L.J.; Lewis, J.; Su, M.; Sze, C.I. 17beta-Estradiol upregulates and activates WOX1/WWOXv1 and WOX2/WWOXv2 in vitro: potential role in cancerous progression of breast and prostate to a premetastatic state in vivo. Oncogene 2005, 24, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Shu, C.; Chen, L.; Yao, B. Impact of sex, body mass index and initial pathologic diagnosis age on the incidence and prognosis of different types of cancer. Oncol Rep 2018, 40, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.Y.; Liu, Y.H. Sex difference, proteostasis and mitochondrial function impact stroke-related sarcopenia-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 101, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Liang, R.; Chen, J.; Tang, Q. The influence of sex-specific factors on biological transformations and health outcomes in aging processes. Biogerontology 2024, 25, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zou, L.; Zhu, C.; Xia, W. Ameliorative effects of Gly[14]-humanin on cyclophosphamide-induced premature ovarian insufficiency and underlying mechanisms. Reprod Biomed Online 2025, 51, 104901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Cui, H.; Sun, G.; Qi, X.; Yao, X. Mitochondrial dysfunction in age-related sarcopenia: mechanistic insights, diagnostic advances, and therapeutic prospects. Front Cell Dev Biol 2025, 13, 1590524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis, G.G.; de Sousa, M.B.C.; Murawska-Ciałowicz, E. Sex Steroids and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Interactions in the Nervous System: A Comprehensive Review of Scientific Data. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traiffort, E.; Kassoussi, A.; Zahaf, A. Revisiting the role of sexual hormones in the demyelinated central nervous system. Front Neuroendocrinol 2025, 76, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prossnitz, E.R.; Barton, M. The G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor GPER in health and disease: an update. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2023, 19, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głombik, K.; Detka, J.; Budziszewska, B. Hormonal Regulation of Oxidative Phosphorylation in the Brain in Health and Disease. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.A. Mitochondria as the target for disease related hormonal dysregulation. Brain Behav Immun Health 2021, 18, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).