1. Introduction

Myofibroblastoma (MFB) is a benign tumor of the mammary stroma composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, usually presenting as a slow-growing, painless, non-tender mass [

1]. Females and males are equally affected by MFB, and the vast majority of cases are seen in elderly men and postmenopausal women [

2].

The mesenchymal lesions encountered in breast specimens may originate from the mammary parenchyma, its associated skin, subcutaneous tissue, deep soft tissue, or even any of its mesenchymal elements (vascular, fibroblastic / myofibroblastic, adipocytic, peripheral nerve, and smooth muscle) [

3].

The essential and desirable diagnostic criteria for MFB proposed by the WHO in its 5th edition regarding breast tumor classification are: (Essential) well-circumscribed margins, a mesenchymal tumor without epimyoepithelial components, none or only mild nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, low mitotic count, short interlacing fascicles; and (Desirable) positive immunohistochemistry for Desmin, CD34, estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), androgen receptors (AR), FISH: 13q14 deletion [

4,

5].

Diffuse large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified (NOS) is a lymphoma consisting of medium-sized to large B-cells with a diffuse growth pattern and represents 30% of adult lymphoma cases worldwide [

6].

Synchronous primary malignancies of breast, colon, prostate, and other solid cancers involving DLBCL have been reported in the reviewed literature [

7,

8]. It is also well known the influence of chemotherapy and radiation therapy on Second Primary Malignancies (SPM) in DLBCL patients [

9].

The treatment for multiple tumors involving lymphoma requires individualized planning based on the stage and pathological type of each tumor, considering the patient’s overall condition. Once the pathological diagnosis is known, each tumor should be staged independently. Given the potential for confusion between metastatic or relapsed cancer, multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussions are highly recommended for challenging cases [

8].

We present a case of a male patient with a mammary MFB, who was previously diagnosed and treated for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in another medical institution, emphasizing the relevance of the MDT approach for a correct diagnosis and treatment.

2. Case Presentation

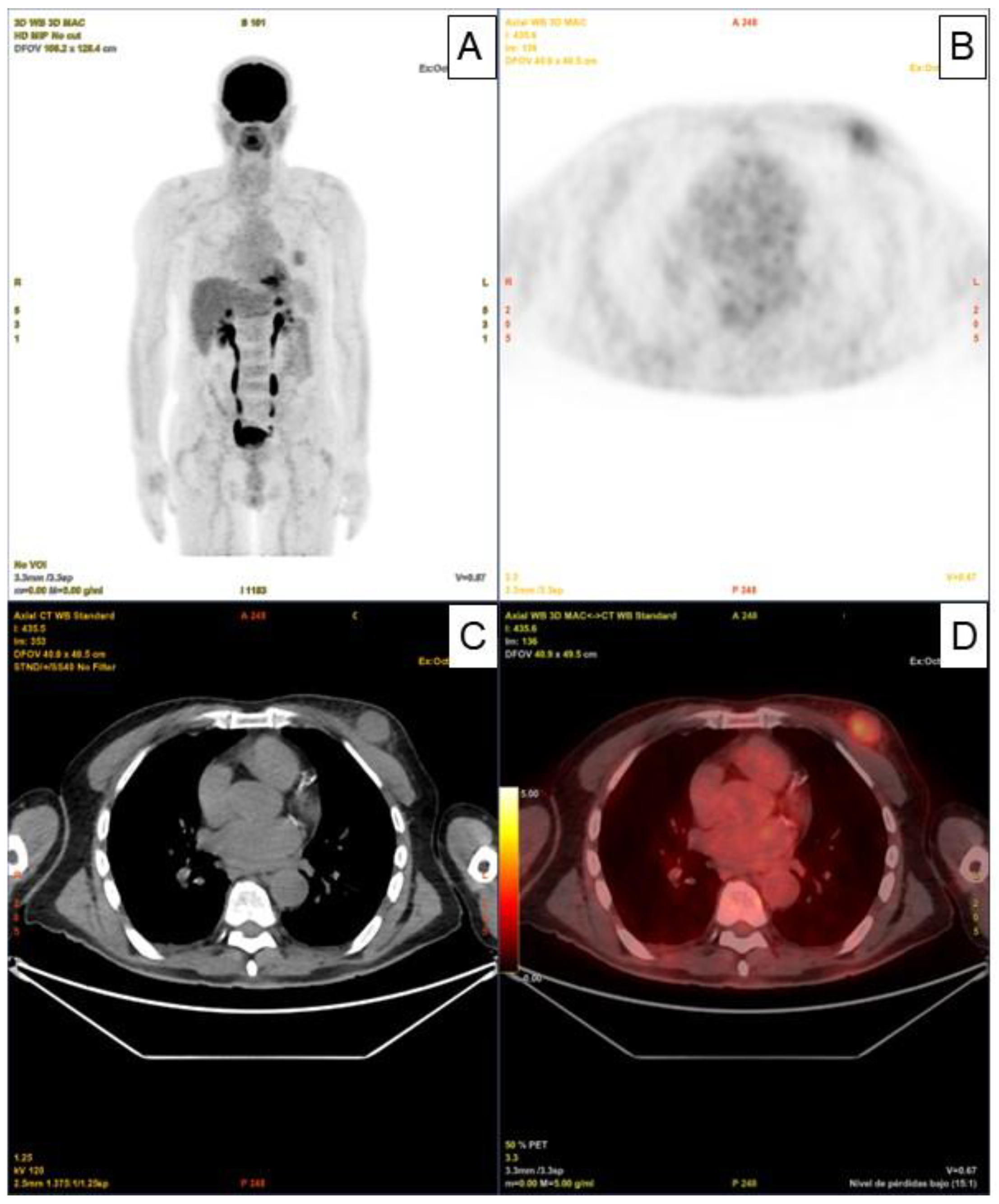

The An 80-year-old man with a history of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) IV-BS stage and a high-risk International Prognostic Index (IPI) who was initially diagnosed and treated in another medical center. The patient underwent six doses of systemic treatment with the R-CHOP regimen. Once the treatment had finished, no adenomegaly or visceromegaly were found on physical examination. The patient had not reported fever or night sweats, and he gained weight during the last months (no B symptoms).The patient underwent 18F - Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography with computed tomography (PET - CT) scan for post therapeutic evaluation purposes, which evidenced partial response with decreased uptake and size in the lymph nodes, however, paradoxically, a nodular solid lesion with faint increase metabolic standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 3 was detected in the upper outer quadrant of his left breast (

Figure 1. Panels A, B, C, D).

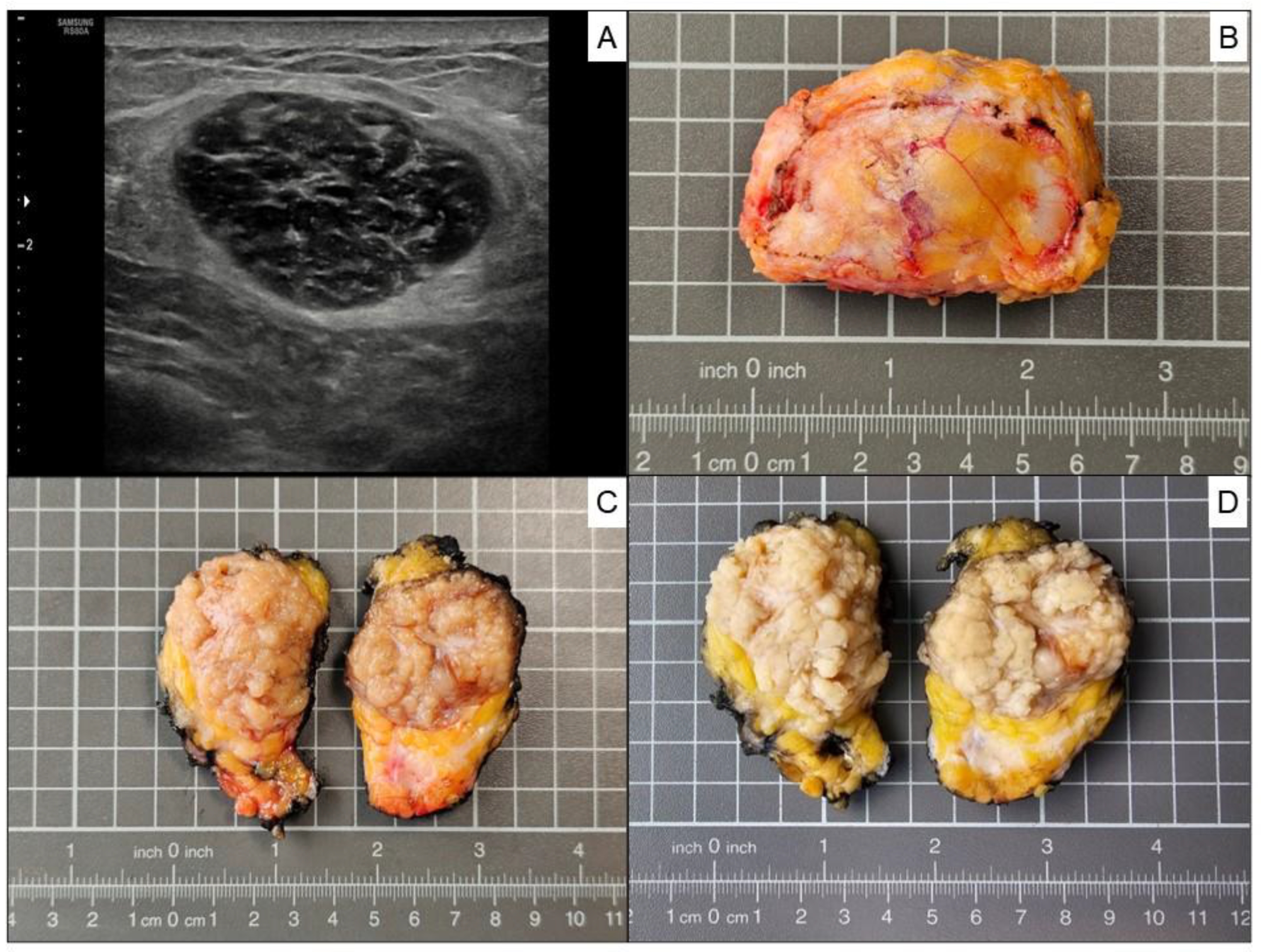

A breast ultrasonographic examination was conducted showing a well circumscribed hypoechoic breast nodule of 3.7 cm in largest diameter, located in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast. (

Figure 2. Panel A). A 14G ultrasound-guided needle biopsy was performed, followed by a biopsy site marker procedure for the precise marking of biopsy site (Tumark® Eye, SOMATEX Medical Technologies). The radiological image indicated a BI-RADS 3 category lesion (probably benign). The pathology report indicated “Spindle cell pattern mesenchymal proliferation. Suggestive of Myofibroblastoma.” An explanatory note was added to the pathology report, urging that a complete tumor study would be necessary to reach a definitive diagnosis. After analyzing the case in the multidisciplinary team, it was decided to perform surgery to completely remove the breast tumor. The surgical specimen showed a well-circumscribed, unencapsulated tumor with a nodular yellow to whitish/ gray cut surface before formaldehyde fixation (

Figure 2. Panels B and C), and light tan color after formaldehyde fixation (

Figure 2. Panel D), measuring 4.5 × 3.4 × 1.8 cm.

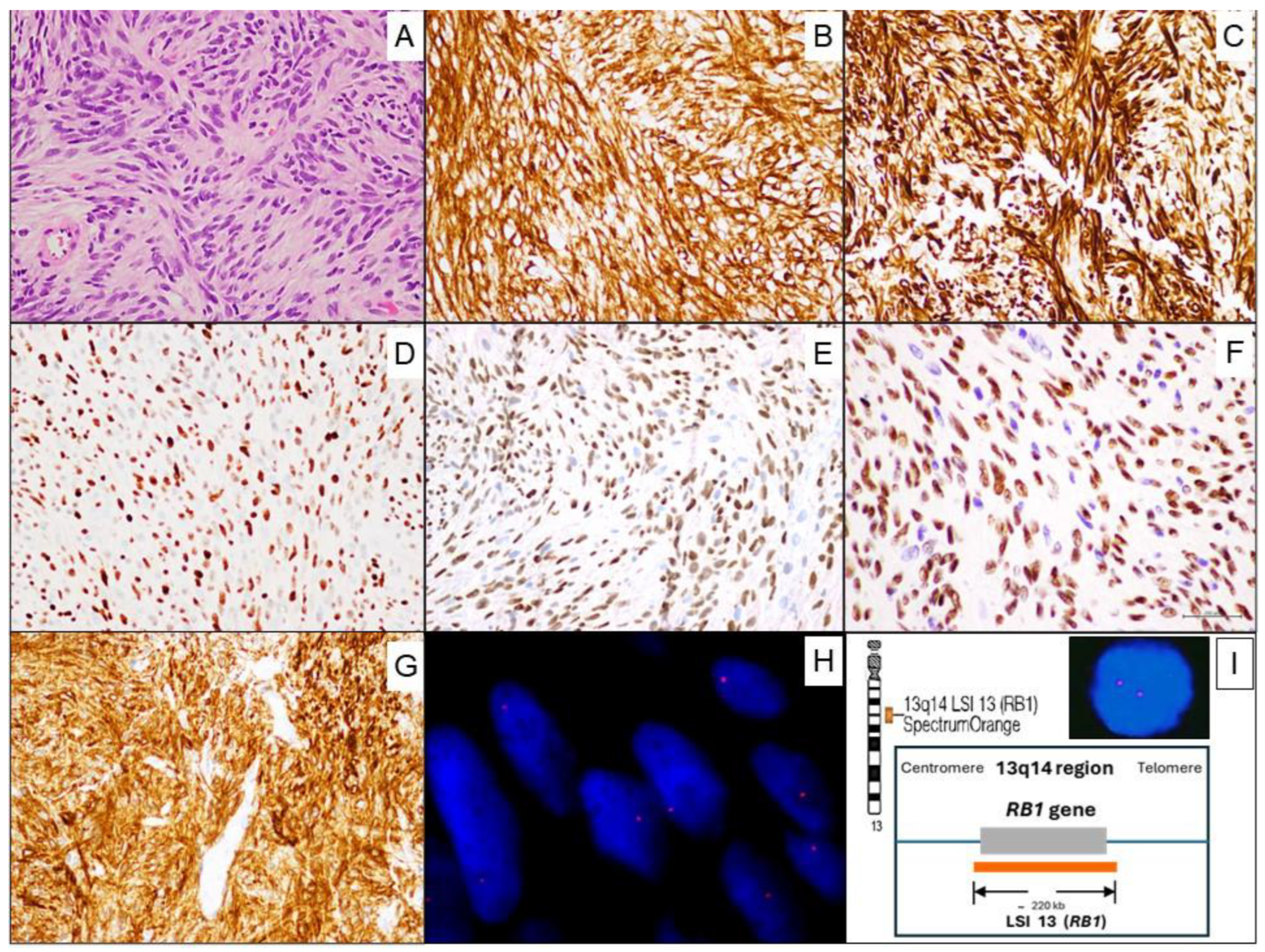

Microscopic examination revealed a mesenchymal tumor proliferation with a well-circumscribed, unencapsulated borders. It consisted of spindle-shaped to oval, monotonous cells with little cytological atypia, displaying pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, arranged randomly or in short intersecting fascicles with fine bundles of hyalinized collagen between the cells. A vaguely storiform pattern was discernible in some areas. The nuclei were round to oval; some of them displayed small, barely evident nucleoli and pseudoinclusions. Mitoses were very rare (1 in 20 high-power fields), without atypical mitotic figures. No entrapment of mammary ducts or lobules was observed. Necrosis was absent. The stroma was fibrous and contained thin-walled capillaries, without a defined organizational pattern (

Figure 3. Panel A). In addition, a small number of mature lymphocytes which showed Leukocyte Common Antigen (LCA/CD45) immunoreactivity and few mast cells which showed CD117 positivity were observed among the tumor cells.

Immunohistochemistry revealed that tumor cells were positive for: CD34 (

Figure 3. Panel B), Desmin (

Figure 3. Panel C), Estrogen receptors (ER) (

Figure 3. Panel D), Progesterone receptors (PR) (

Figure 3. Panel E), Androgen receptors (AR) (

Figure 3. Panel F), CD10 (

Figure 3. Panel G), and focally Muscle Specific Actin (MSA). By contrast, the tumor cells were negative for Cytokeratins (AE1-AE3), S100, STAT6, ALK, β-Catenin, CD117, CD31, and LCA/CD45.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to determine the status of 13q14 (RB1) was performed and analyzed at our Molecular Cytogenetics Unit. Two micrometer sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue were used and then the Vysis LSI 13 (RB1) 13q14 SpectrumOrange Probe was performed. The FISH analysis showed a loss of one signal of RB1 (deletion at the 13q14 region) in 84% of the tumor cell nuclei (

Figure 3. Panel H), confirming the diagnosis of MFB.

During the follow-up, the patient has not presented symptoms or any complications since surgery (12 months) and remains in complete remission (CR) of lymphoma.

3. Discussion

Authors In the last decades, the introduction of effective therapies like R-CHOP has had a significant impact on the cure rates for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), leading to an increase in number of long-term survivors [

10]. Nevertheless, some of these long-term survivors develop Secondary Primary Malignancies (SPM), or benign tumors, as well as complications related directly or indirectly to the treatment modality [

11], the age at diagnosis [

9,

12], the time since the DLBCL diagnosis, and the stage of the disease at diagnosis [

11].

The wide spectrum of secondary tumors in patients with history of DLBCL requires a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach that includes at least a hematologist, a radiologist, a surgeon and a pathologist [

10,

13].

Various cases of DLBCL combined with one or two different primary tumors have been reported in the last decades [

8].

Extramammary MFB has been described, and it is often referred to as ‘mammary-type’ Myofibroblastoma (MTMF) when occurring at other sites [

14]. In this way MTMF has been reported at different anatomic locations including inguinal/groin region [

15], chest wall [

16], axilla [

17], lower and upper extremities [

18], intra-abdominal/retroperitoneal [

19], liver [

20,

21]. Therefore, it is likely that any of these locations could be misdiagnosed as metastasis or relapse of DLBCL in follow-up radiological tests.

Immunohistochemistry is useful for distinguishing MFB from other tumors included in the differential diagnosis, such as metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma (in cases located in the breast), nodular fasciitis, fibromatosis, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), solitary fibrous tumor, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, and spindle cell lipoma, among others [

3,

22]. Therefore, the immunohistochemical panel used should include the following antibodies: Cytokeratin (AE1-AE3), STAT6, ALK, β-catenin, EMA, S100, and others [

23,

24,

25]. Our case also showed immunoreactivity for CD10 in concordance with the reported cases by Gaetano Magro, et al [

26].

Monoallelic 13q14 deletion and the RB1 loss by immunohistochemistry are not specific chromosomal alterations of MFB. Other rare benign mesenchymal tumors such as spindle cell/pleomorphic lipomas (SCLs) and cellular angiofibromas (CAFs) also show this structural chromosomal abnormality [

27]. Monoallelic 13q14 deletion and the RB1 loss have also been identified in a significant subset of cases of atypical spindle/pleomorphic lipomatous tumors (ASPLT) [

28]. Based on the clinicopathological context of our case it is of interest to know that 13q14 deletion is a recurrent event in some hematologic neoplasms such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) [

29,

30], and in a subset of DLBCL [

31], but in our patient, the DLBCL did not show 13q14 deletion.

It is also important to note that the most frequent primary lymphoma of the breast is precisely the DLBCL [

32]. However, any type of lymphoma can occur as primary breast lymphoma (PBL). PBL is a rare condition, accounting for less than 0.5% of all breast malignancies [

33].

In contrast to the extensively documented incidence of second malignant neoplasms in lymphoma patients [

9,

34,

35,

36], there is not enough evidence addressing the potential association between lymphomas and the subsequent development of benign tumors. Sometimes, these tumors can be misdiagnosed as lymphoma relapses or disease progression on imaging. In this context, the 18F-FDG PET-CT can help to clarify the nature of second tumors. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report in medical literature of a mammary MFB arising in a male in the context of DLBCL. The constellation of histological features when supported by monoallelic loss of 13q14 region detected by FISH and RB1 loss by immunohistochemistry, in the appropriate clinical context, confirms the diagnosis of this benign entity avoiding overtreatment.

4. Conclusions

Since there are no established guidelines on how to proceed with these patients, it is necessary to develop standards for the management of these cases. Based on our experience, we suggest the following workflow: (1) First, the case should be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) which must include at least one hematologist, one radiologist, one nuclear medicine specialist, one surgeon and one pathologist. (2) A correct interpretation of imaging (especially 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography with computed tomography (PET-CT)) can help to distinguish lymphoma relapses from a second benign tumor. If doubts persist, (3) a biopsy with adequate tissue for histology, immunohistochemical, and molecular techniques should be performed. The pathology report will confirm the tumor cells’ nature (benign or malignant; lymphoid, epithelial or mesenchymal lineage). If pathology confirms Myofibroblastoma (MFB), and there are no clinical or surgical contraindications, (4) the complete tumor excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice. Finally, (5) following definitive treatment, standardized clinical and radiological follow up must be carried out to detect lymphoma relapses, MFB local recurrence, or the appearance of new masses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.C-T.; J.M.S.; C.M.F.; methodology, C.M.F.; N.C.G.; E.A.A.; data curation, C.M.F.; E.A.A.; M.Á.H.G.; L.G.D.G.; resources, J.M.S.; C.M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.C-T.; C.M.F.; E.A.A.; M.A.C.S.; writing—review and editing, L.M.C-T.; I.G.M.; S.G.G.; supervision, J.L.R.H.; J.M.S.; project administration, L.M.C-T.; C.M.F.; M.A.C.S.; E.A.A. All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public or private sectors.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the patient for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. For any further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MFB |

Myofibroblastoma |

| MTMF |

“Mammary -type” Myofibroblastoma |

| DLBCL |

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma |

| NOS |

Not Otherwise Specified |

| SPM |

Second Primary Malignancies |

| PBL |

Primary Breast Lymphoma |

| MDT |

Multidisciplinary Team |

| PET-CT |

Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography |

| 18F-FDG |

18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| SUV |

Standardized Uptake Value |

| FFPE |

Formalin -Fixed Paraffin -Embedded |

| FISH |

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization |

| ER |

Estrogen Receptor |

| PR |

Progesterone Receptor |

| AR |

Androgen Receptor |

References

- Magro G. Mammary myofibroblastoma: an update with emphasis on the most diagnostically challenging variants. Histol Histopathol. 2016;31(1):1-23. [CrossRef]

- Magro G. Mammary myofibroblastoma: a tumor with a wide morphologic spectrum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(11):1813-1820. [CrossRef]

- Anderson WJ, Fletcher CDM. Mesenchymal lesions of the breast. Histopathology. 2023;82(1):83-94. [CrossRef]

- Hornick. J.L, Lazar. A.L, Schnitt. S. Mesenchymal tumors of the breast. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Breast tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019. . (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 2). https://publications.iarc.fr/581.

- Magro G, Van de Rijn. M, Liegl-Atzwanger. B, D.M. Fletcher. C, W. Charville. G. Myofibroblastoma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Breast tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 2). https://publications.iarc.fr/581.

- Andreas Rosenwald, Jan Delabie, L. Jeffrey Medeiros, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma NOS. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Haematolymphoid tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 11). https://publications.iarc.who.int/637.

- Ueda Y, Makino Y, Tochigi T, et al. A rare case of synchronous multiple primary malignancies of breast cancer and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that responded to multidisciplinary treatment: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2022;8(1):99. Published 2022 May 19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhou S, Zhou Y, Qiu H. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma combined with two solid tumors: a case report. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1561923. Published 2025 Jun 17. [CrossRef]

- Rock CB, Chipman JJ, Parsons MW, et al. Second Primary Malignancies in Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma Survivors with 40 Years of Follow Up: Influence of Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2022;7(6):101035. Published 2022 Jul 26. [CrossRef]

- Ernst M, Dührsen U, Hellwig D, Lenz G, Skoetz N, Borchmann P. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma and Related Entities. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2023;120(17):289-296. [CrossRef]

- Major A, Smith DE, Ghosh D, Rabinovitch R, Kamdar M. Risk and subtypes of secondary primary malignancies in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma survivors change over time based on stage at diagnosis. Cancer. 2020;126(1):189-201. [CrossRef]

- Sacchi S, Marcheselli L, Bari A, et al. Second malignancies after treatment of diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a GISL cohort study. Haematologica. 2008;93(9):1335-1342. [CrossRef]

- Velicu MA, Lavrador JP, Sibtain N, et al. Neurosurgical Management of Central Nervous System Lymphoma: Lessons Learnt from a Neuro-Oncology Multidisciplinary Team Approach. J Pers Med. 2023;13(5):783. Published 2023 Apr 30. [CrossRef]

- Howitt BE, Fletcher CD. Mammary-type Myofibroblastoma: Clinicopathologic Characterization in a Series of 143 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(3):361-367. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara A, Yasuda T, Sakae Y, et al. A case of mammary-type myofibroblastoma of the inguinal region. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:464-467. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Lee H, Lee OJ, Cho KJ, Ro JY. Epithelioid myofibroblastoma of mammary-type in chest wall: a case report. Korean J Pathol 2005;39(2):130-3.

- Aden D, Sharma M, Zaheer S, Ranga S. Axillary intranodal palisaded myofibroblastoma, a rare tumour at an unusual site, with literature review. Rev Esp Patol. 2025;58(1):100791. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Ghafar J, Ud Din N, Ahmad Z, Billings SD. Mammary-type myofibroblastoma of the right thigh: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2015; 9:126. Published 2015 Jun 2. [CrossRef]

- Watari S, Ichikawa T, Shiraishi H, et al. Retroperitoneal myofibroblastoma in an 88-year-old male. IJU Case Rep. 2022;5(5):378-382. Published 2022 Jun 14. [CrossRef]

- Narasimhamurthy M, Savant D, Shreve L, et al. Myofibroblastoma in the Liver: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2023;31(8):1559-1564. [CrossRef]

- Millo NZ, Yee EU, Mortele KJ. Mammary-type myofibroblastoma of the liver: multi-modality imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39(3):482-487. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki T, Ichikawa J, Kanno S, et al. Case report: A challenging case of mixed-variant myofibroblastoma with complex imaging and pathological diagnosis. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1438162. Published 2024 Oct 18. [CrossRef]

- Nerune SM, Sasnur P, Das SK, Jacob KA. Myofibroblastoma of the breast mimicking carcinoma: a diagnostic challenge with a crucial role for histopathology and immunohistochemistry. BMJ Case Rep. 2025;18(1):e263503. Published 2025 Jan 25. [CrossRef]

- Pinnaka M, Patino MG, Ravi V, Nazarullah A, Jatoi I. Breast Myofibroblastoma: A Single Institutional Case Series. Eur J Breast Health. 2025;21(3):211-214. [CrossRef]

- Kaki M, Klein S, Singh C, Kothe B, Martin J. An Immunohistochemical Anomaly: A Case Report and Systematic Review of Myofibroblastoma of the Breast. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e46125. Published 2023 Sep 28. [CrossRef]

- Magro G, Caltabiano R, Di Cataldo A, Puzzo L. CD10 is expressed by mammary myofibroblastoma and spindle cell lipoma of soft tissue: an additional evidence of their histogenetic linking. Virchows Arch. 2007;450(6):727-728. [CrossRef]

- Uehara K, Ikehara F, Shibuya R, et al. Molecular Signature of Tumors with Monoallelic 13q14 Deletion: a Case Series of Spindle Cell Lipoma and Genetically-Related Tumors Demonstrating a Link Between FOXO1 Status and p38 MAPK Pathway. Pathol Oncol Res. 2018;24(4):861-869. [CrossRef]

- Lecoutere E, Creytens D. Atypical spindle cell/pleomorphic lipomatous tumor. Histol Histopathol. 2020;35(8):769-778. [CrossRef]

- Khalid K, Padda J, Syam M, et al. 13q14 Deletion and Its Effect on Prognosis of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e16839. Published 2021 Aug 2. [CrossRef]

- Xia C, Liu G, Liu J, et al. The Heterogeneity of 13q Deletions in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Diagnostic Challenges and Clinical Implications. Genes (Basel). 2025;16(3):252. Published 2025 Feb 22. [CrossRef]

- Mian M, Scandurra M, Chigrinova E, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with 13q14.3 deletion. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(3):729-735. [CrossRef]

- Cheah CY, Campbell BA, Seymour JF. Primary breast lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(8):900-908. [CrossRef]

- Caon J, Wai ES, Hart J, et al. Treatment and outcomes of primary breast lymphoma. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12(6):412-419. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Shi X, Wang X, Zhang P, Bai O, Li Y. Second malignant neoplasms in lymphomas, secondary lymphomas and lymphomas in metabolic disorders/diseases. Cell Biosci. 2022;12(1):30. Published 2022 Mar 12. [CrossRef]

- Eichenauer DA, Becker I, Monsef I, et al. Secondary malignant neoplasms, progression-free survival and overall survival in patients treated for Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Haematologica. 2017;102(10):1748-1757. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Zhang Q, Chen B. Correlation between lymphoma and second primary malignant tumor. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(19):e33712. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).