Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

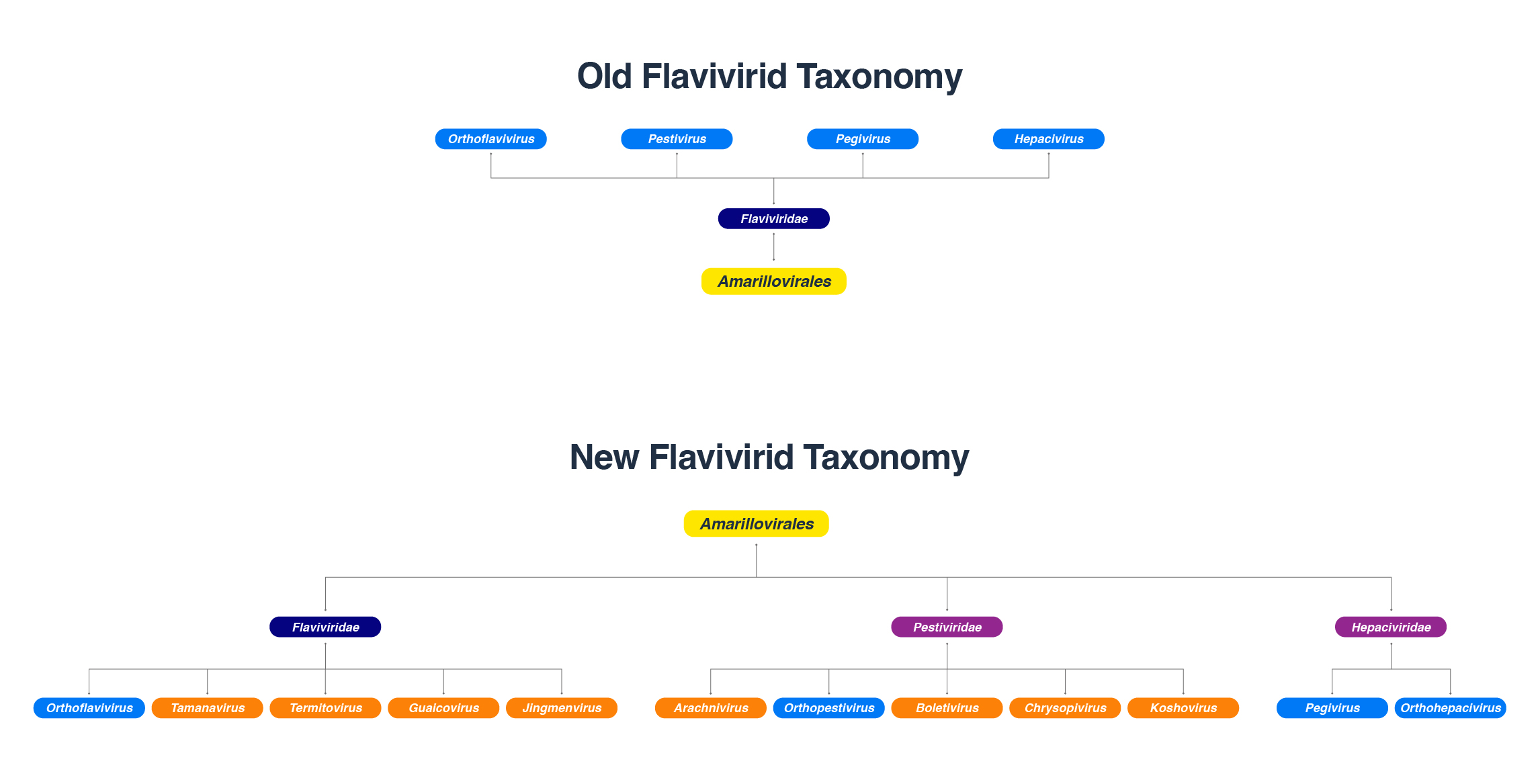

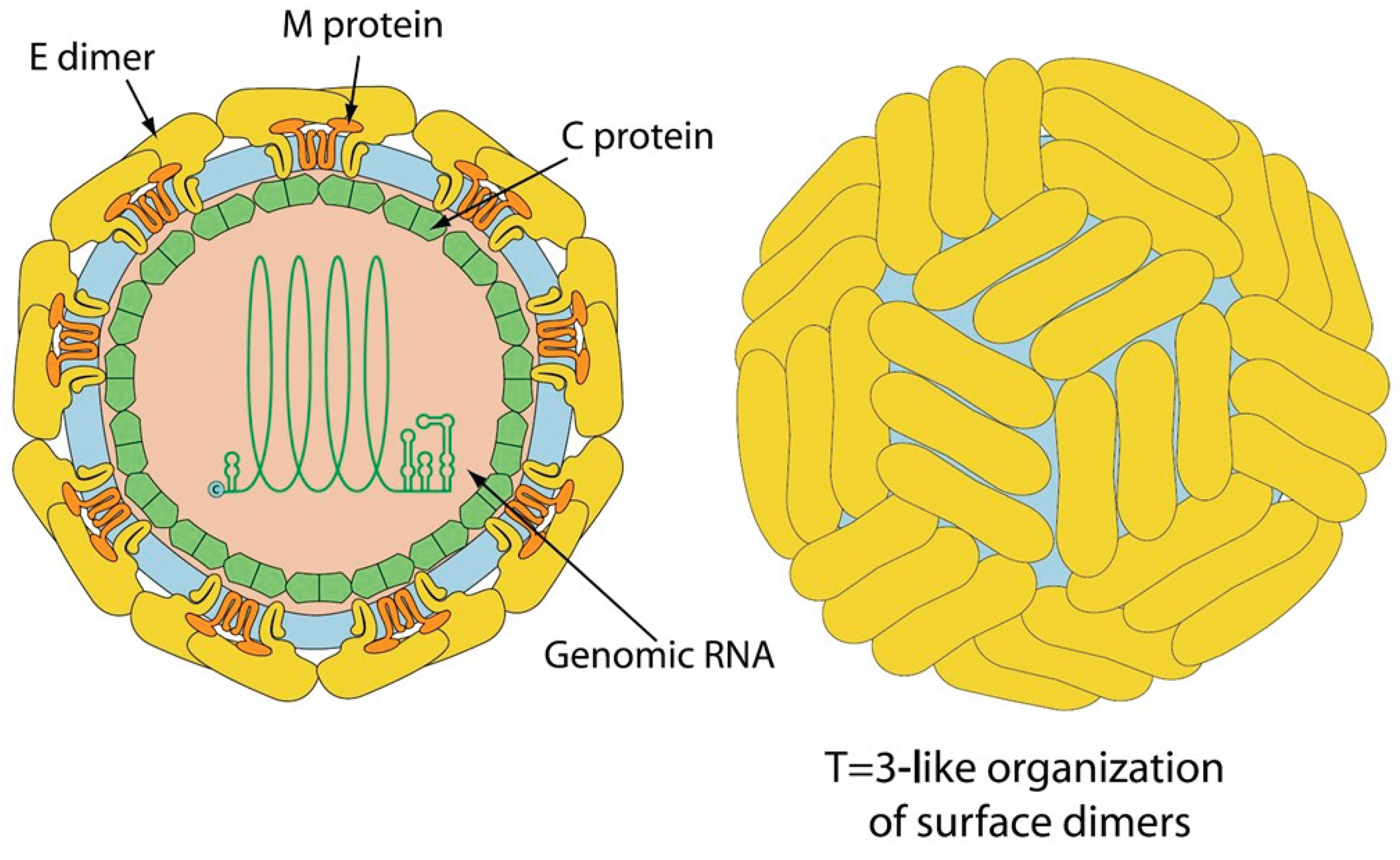

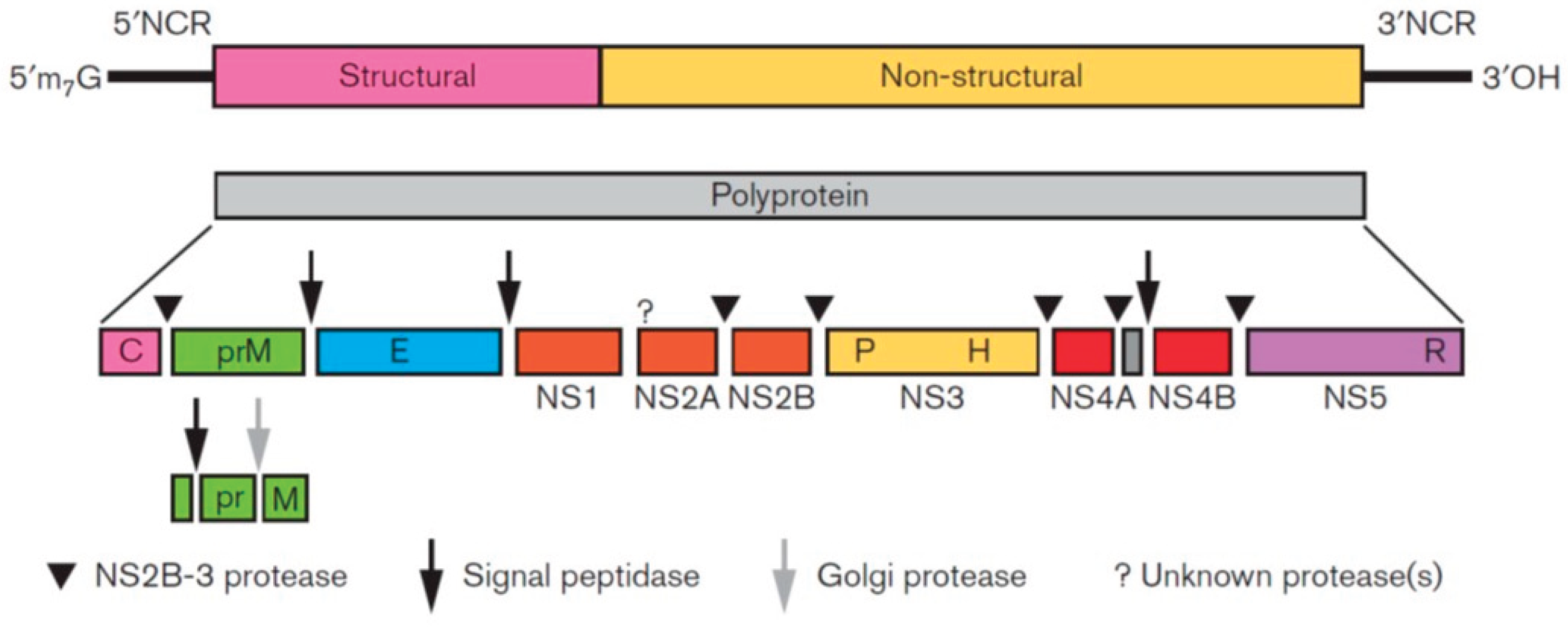

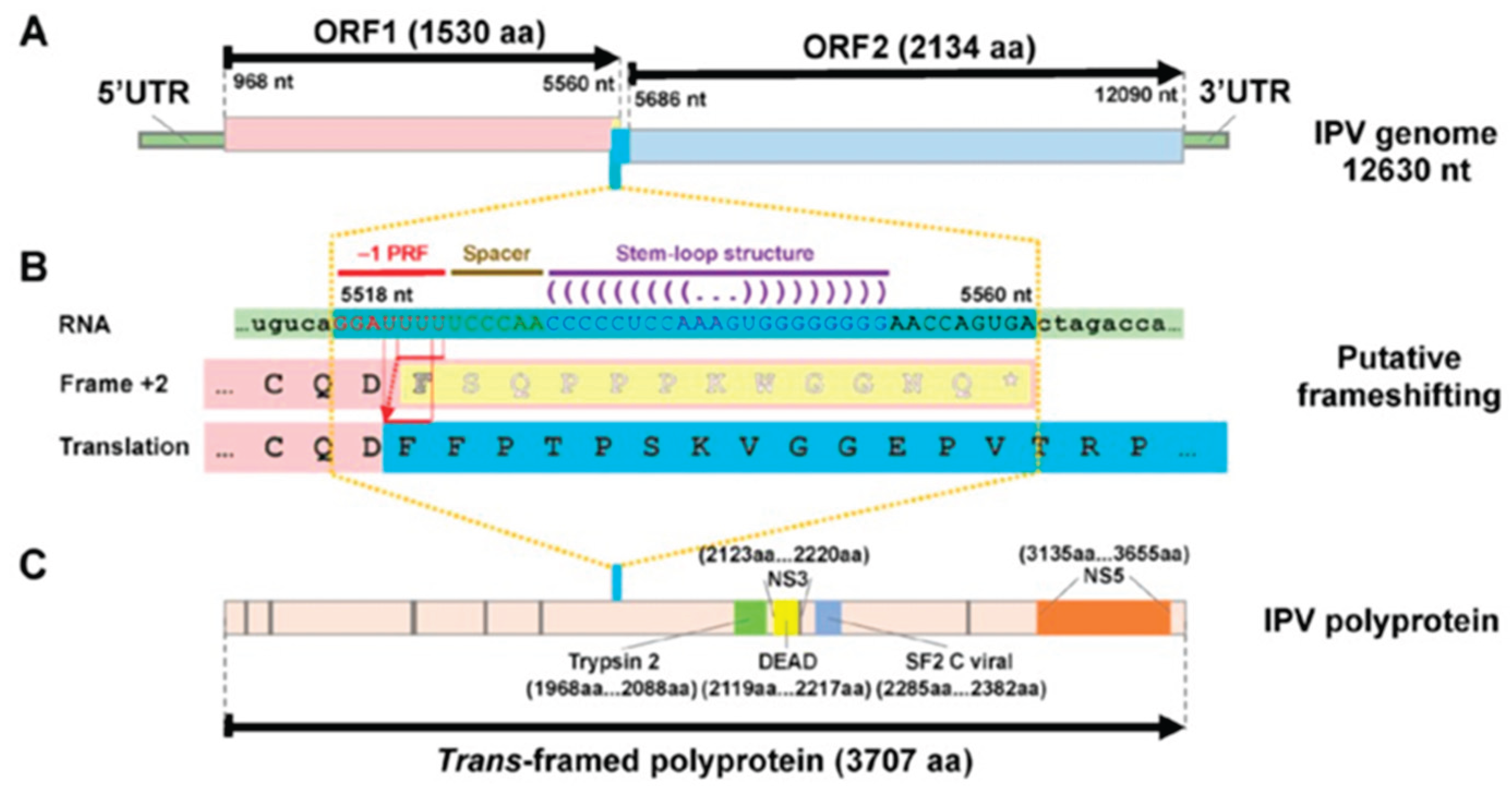

The family Flaviviridae has been expanded to include the highly divergent flavi-like viruses into three new families, Flaviviridae, Pestiviridae, and Hepaciviridae in the order Amarillovirales. Classical flavivirids are small, enveloped viruses with positive-sense ssRNA genomes lacking a 3’ poly(A) tail, and ~ 9.0-13.0 kb in length, with a single ORF encoding structural proteins at the N terminus and nonstructural proteins at the C terminus. Members infect a wide range of mammals, birds, and insects, and many are host-specific and pathogenic. Although the RdRP gene sequences of the flavi-like viruses group phylogenetically with those of classical flavivirids, flavi-like viruses often encode larger polyproteins and possess substantially longer genomes of up to ~ 40 kb, and some have a 3’ poly(A) tail. Their host range extends across the whole animal kingdom and in angiosperm plants. This review describes the reported flavi-like viruses of aquatic animals, providing a meaningful update on all three new families in Amarillovirales that have been discovered in fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and echinoderms, using metagenomics. These amarilloviruses include pathogenic viruses of aquatic animals, such as Cyclopterus lumpus virus (CLuV) detected in moribund lumpfish, and Infectious precocity virus (IPV) found in iron prawn syndrome (IPS)-affected farmed giant freshwater prawns.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Virus Characteristics

3. Fish Amarilloviruses

3.1. Cyclopterus Lumpus Virus (CLuV)

3.2. Wenzhou Shark Flavivirus

3.3. Eastern Red Scorpionfish Flavivirus

3.4. Western Carp Gudgeon Flavivirus

3.5. Salmon Flavivirus (SFV)

4. Crustacean Amarilloviruses

Crustaflavivirus Infeprecoquis (Infectious Precocity Virus, IPV)

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simmonds, P., Butković, A., Grove, J. et al. 2025a. Taxonomic expansion and reorganization of Flaviviridae. Nat Microbiol 10, 3026-3037. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, P., Butkovic, A., Grove, J., Mayne, R., Mifsud, J.C.O., Beer, M., Bukh, J., Drexler, J.F., Kapoor, A., Lohmann, V., Smith, D.B., Stapleton, J.T., Vasilakis, N., Kuhn, J.H. 2025b. Reorganization of Flaviviridae (order Amarillovirales) and classification of ‘flavi-like’ viruses into three families, 12 genera, and 3 subgenera. 2025.006S.Ac.v2.Amarillovirales_3reorgfam. Available online: https://ictv.global/system/files/proposals/pending/2025/Animal%20%2BssRNA%20%28S%29%20proposals/2025.006S.Ac.v2.Amarillovirales_3reorgfam.docx (accessed on December 23, 2025).

- Snyder, J. E., Jose, J., Kuhn, R. J., 2014. The Togaviridae and the Flaviviridae, Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Choo, Q-L., Richman, K. H., Han, J. H., Berger, K., Lee, C. et al. Genetic organization and diversity of the hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991;88(6):2451-2455. [CrossRef]

- Postler, T.S., Beer, M., Blitvich, B.J. et al. 2023. Renaming of the genus Flavivirus to Orthoflavivirus and extension of binomial species names within the family Flaviviridae. Archives of Virology 168, 224. [CrossRef]

- Porter, A. F., Pettersson, J. H. O., Chang, W. S., Harvey, E., Rose, K., Shi, M. et al (2020) Novel hepaci- and pegi-like viruses in native Australian wildlife and non-human primates. Virus Evol 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, P., Becher, P., Bukh, J., Gould, E. A., Meyers, G., Monath, T., Muerhoff, S., Pletnev, A., Rico-Hesse, R., Smith, D. B., Stapleton, J. T., & ICTV Report Consortium., 2017. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae. The Journal of General Virology, 98(1), 2-3. [CrossRef]

- Petrone, M. E., Grove, J., Mélade, J., Mifsud, J. C. O., Parry, R. H. et al. 2024. A ~40-kb flavi-like virus does not encode a known error-correcting mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 121(30):e2403805121. [CrossRef]

- Mifsud, J. C. O., Costa, V, A., Petrone, M. E., Marzinelli, E. M., Holmes, E. C. et al. 2023. Transcriptome mining extends the host range of the Flaviviridae to non-bilaterians. Virus evolution 9(1):veac124. [CrossRef]

- Parry, R., Asgari, S., 2019. Discovery of novel crustacean and cephalopod flaviviruses: insights into the evolution and circulation of flaviviruses between marine invertebrate and vertebrate hosts. Journal of Virology 93:e00432-19. [CrossRef]

- Lay, C. L., Shi, M., Buček, A., Bourguignon, T., Lo, N. et al. 2020. Unmapped RNA Virus Diversity in Termites and their Symbionts. Viruses, 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, S., Käfer, S., Zirkel, F. et al. 2021. Viromics of extant insect orders unveil the evolution of the flavi-like superfamily. Virus Evol 7:veab030. [CrossRef]

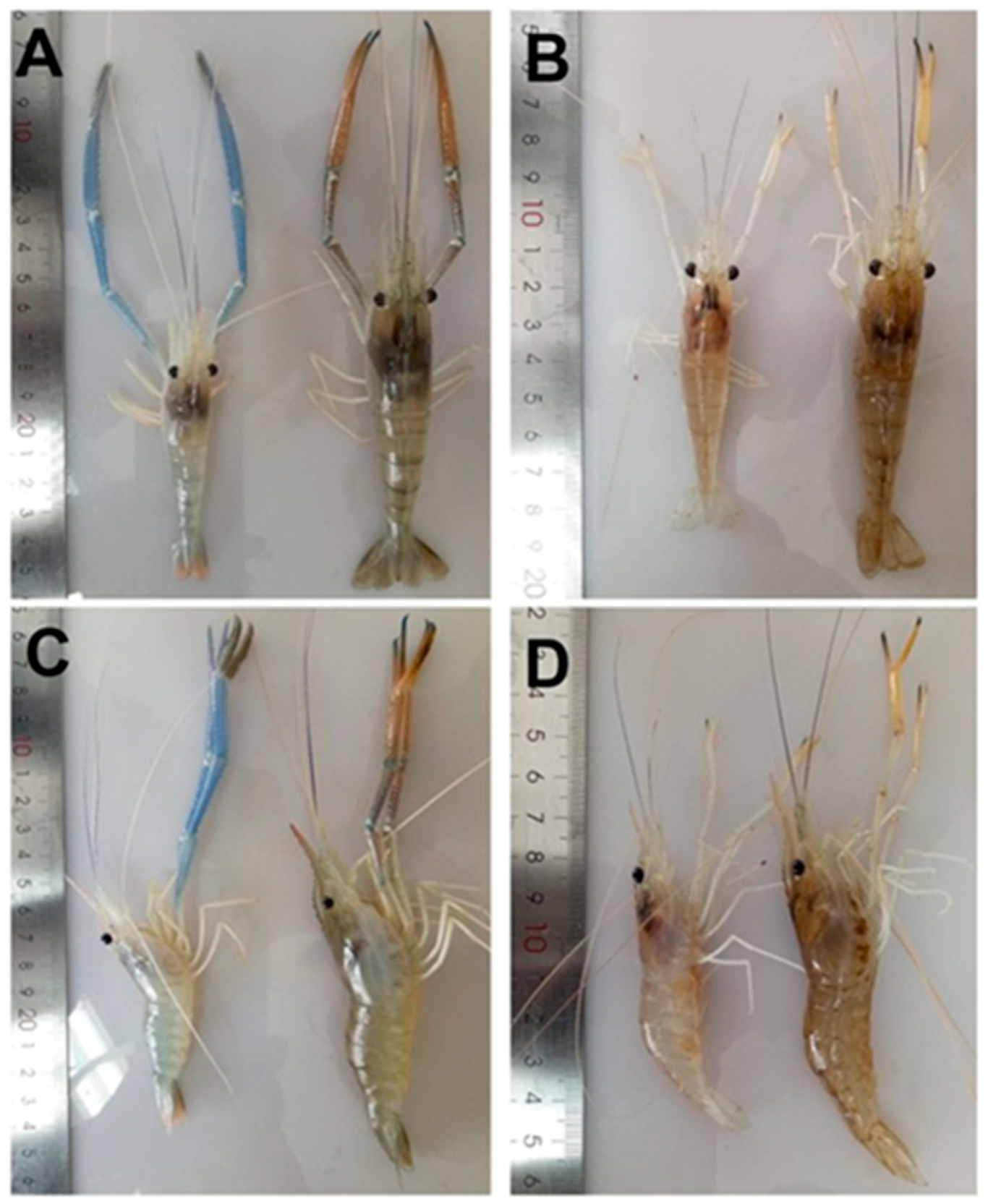

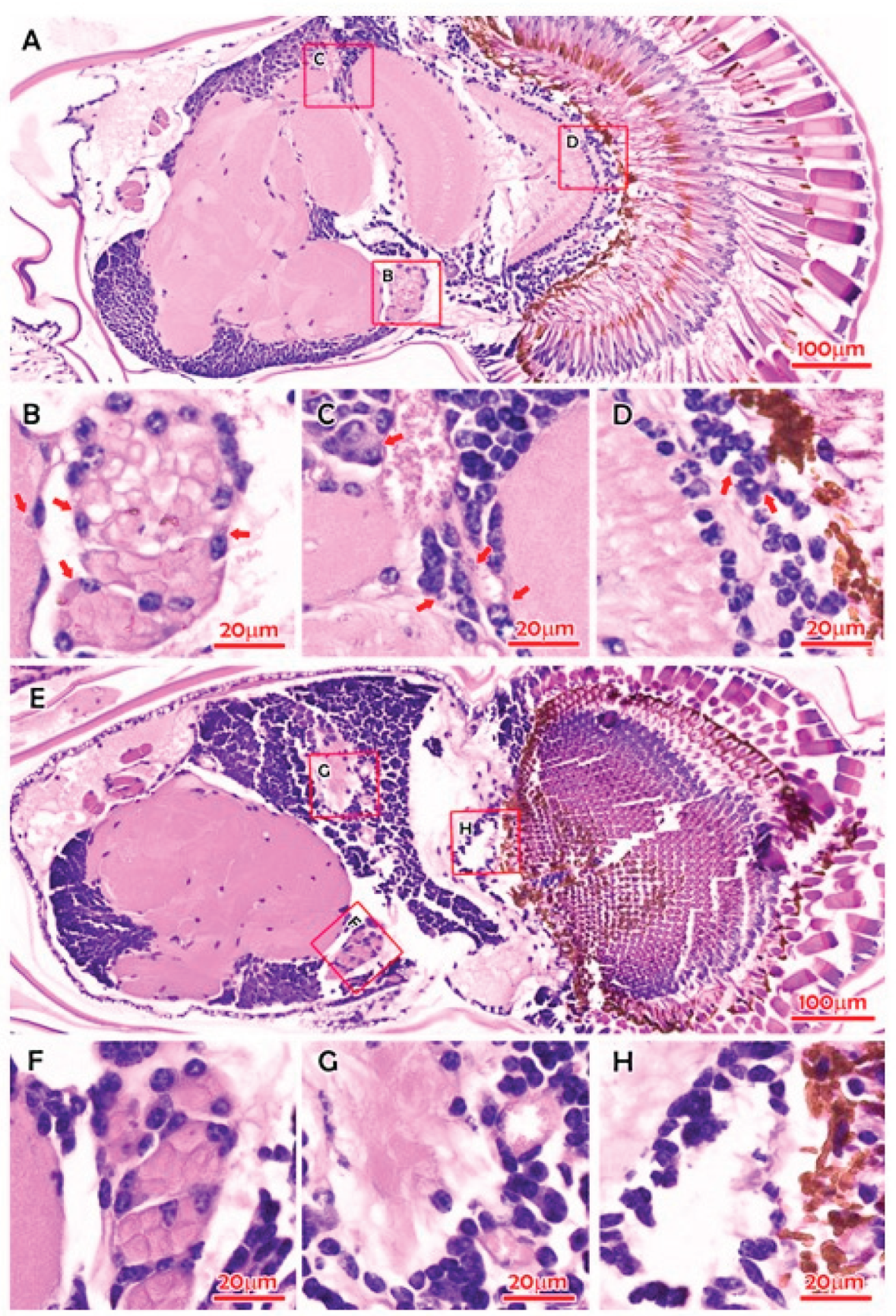

- Dong, X., Wang, G., Hu, T., Li, J., Li, C., Cao, Z., Shi, M., Wang, Y., Zou, P., Song, J., Gao, W., Meng, F., Yang, G., Tang, K. F. J., Li, C., Shi, W., Huang, J., 2021. A Novel Virus of Flaviviridae Associated with Sexual Precocity in Macrobrachium rosenbergii. mSystems 6(3):e0000321. [CrossRef]

- Bekal, S., Domier, L. L., Gonfa, B., McCoppin, N. K., Lambert, K. N. et al. 2014. A novel flavivirus in the soybean cyst nematode. J Gen Virol 95(Pt 6):1272-1280. [CrossRef]

- Dheilly, N. M., Lucas, P., Blanchard, Y., Rosario, K. A. 2022. World of Viruses Nested within Parasites: Unraveling Viral Diversity within Parasitic Flatworms (Platyhelminthes). Microbiol Spectr 10(3):e0013822. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y-M., Sadiq, S., Tian, J-H., Chen, X., Lin, X-D. et al. 2022. RNA viromes from terrestrial sites across China expand environmental viral diversity. Nat Microbiol 7(8):1312-1323. [CrossRef]

- Hewson I., Johnson M. R., Tibbetts I. R., 2020. An unconventional flavivirus and other RNA viruses in the sea cucumber (Holothuroidea; Echinodermata) virome. Viruses 12, 1057. [CrossRef]

- Shi, M., Lin, X-D., Vasilakis, N., Tian, J-H., Li, C-X., Chen, L-J., Eastwood, G., Diao, X-N., Chen, M-H., Chen, X., Qin, X-C., Widen, S. G., Wood, T. G., Tesh, R. B., Xu, J., Holmes, E. C., Zhang, Y-Z., 2016. Divergent viruses discovered in arthropods and vertebrates revise the evolutionary history of the Flaviviridae and related viruses. Journal of Virology, 90, 659-669. [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, J. L., Di Giallonardo, F., Cousins, K., Shi, M., Williamson, J. E., Holmes, E. C., 2018. Hidden diversity and evolution of viruses in market fish. Virus evolution, 4(2), vey031. [CrossRef]

- Skoge, R.H., Brattespe, J., Økland, A.L. et al. 2018. New virus of the family Flaviviridae detected in lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus). Archives of Virology 163:679-685. [CrossRef]

- Soto, E., Camus, A., Yun, S., Kurobe, T., Leary, J. H., Rosser, T. G., Dill-Okubo, J. A., Nyaoke, A. C., Adkison, M., Renger, A., Ng, T. F. F., 2020. First Isolation of a Novel Aquatic Flavivirus from Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and Its In Vivo Replication in a Piscine Animal Model. Journal of Virology 94(15):e00337-20. [CrossRef]

- Costa, V. A., Mifsud, J. C. O., Gilligan, D., Williamson, J. E., Holmes, E. C., Geoghegan, J. L., 2021. Metagenomic sequencing reveals a lack of virus exchange between native and invasive freshwater fish across the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia. Virus evolution, 7(1), veab034. [CrossRef]

- Parry, R. H., Slonchak, A, Campbell, L. J., Newton, N. D., Debat, H. J., Gifford, R. J., Khromykh, A. A. 2023. A novel tamanavirus (Flaviviridae) of the European common frog (Rana temporaria) from the UK. J Gen Virol. 104(12):001927. [CrossRef]

- Urayama, S-I., Takaki, Y., Nunoura, T. 2016. FLDS: A Comprehensive dsRNA Sequencing Method for Intracellular RNA Virus Surveillance. Microbes Environ 31(1):33-40. [CrossRef]

- Forgia, M., Daghino, S., Chiapello, M., Ciuffo, M., Turina, M. 2024. New clades of viruses infecting the obligatory biotroph Bremia lactucae representing distinct evolutionary trajectory for viruses infecting oomycetes. Virus evolution, 10(1):veae003. [CrossRef]

- Debat, H., Bejerman, N. 2023. Two novel flavi-like viruses shed light on the plant-infecting koshoviruses. Arch Virol 168:184. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Yang, C., Qiu, Y., Liao, R., Xuan, Z. et al. 2024. Conserved untranslated regions of multipartite viruses: Natural markers of novel viral genomic components and tags of viral evolution. Virus evolution, 10(1):veae004. [CrossRef]

- Schönegger, D., Marais, A., Faure, C. et al. 2022. A new flavi-like virus identified in populations of wild carrots. Arch Virol 167:2407–09. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A., Romero-Severson, E., Claverie, J. M. 2020. Investigating the Concept and Origin of Viruses. Trends Microbiol 28(12):959-967. [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, E. E., Nerva, L., Nigg, J. C., Falk, B. W., Nouri, S. 2016. Complete Genome Sequence of the Largest Known Flavi-Like Virus, Diaphorina citri flavi-like virus, a Novel Virus of the Asian Citrus Psyllid, Diaphorina citri. Genome Announc 4(5). [CrossRef]

- Kartashov, M. Y., Gladysheva, A. V., Shvalov, A. N., Tupota, N. L., Chernikova, A. A. et al. 2023. Novel Flavi-like virus in ixodid ticks and patients in Russia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 14(2):102101. [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, G., Tomita, R., Kobayashi, K. et al. 2013. Prevalence and genetic diversity of an unusual virus associated with Kobusho disease of gentian in Japan. J Gen Virol 94:2360–65. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M., Bignell, J. P., Papadopoulou, A., Trani, E., Savage, J., Joseph, A. W., Wood, G., Stone, D. M., 2022. First Detection of Cyclopterus Lumpus Virus in England, Following a Mortality Event in Farmed Cleaner Fish. Bulletin of the European Association of Fish Pathologists 43(1): 28-37. [CrossRef]

- Qin, X. C., Shi, M., Tian, J. H., Lin, X. D., Gao, D. Y., He, J. R., Wang, J. B., Li, C. X., Kang, Y. J., Yu, B., Zhou, D. J., Xu, J., Plyusnin, A., Holmes, E. C., Zhang, Y. Z., 2014. A tick-borne segmented RNA virus contains genome segments derived from unsegmented viral ancestors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(18):6744-6749. [CrossRef]

- Colmant, A. M. G., Charrel, R. N., Coutard, B., 2022. Jingmenviruses: Ubiquitous, understudied, segmented flavi-like viruses. Frontiers in Microbiology 13:997058. [CrossRef]

- Lensink, M. J., Li, Y., Lequime, S., Pierson, T. C., 2022. Aquatic Flaviviruses. Journal of Virology 96(17):e00439-22. [CrossRef]

- Shi, M., Lin, X. D., Chen, X., Tian, J. H., Chen, L. J., Li, K., Wang, W., Eden, J. S., Shen, J. J., Liu, L., Holmes, E. C., Zhang, Y. Z., 2018. The evolutionary history of vertebrate RNA viruses. Nature 556(7700), 197-202. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alarcón, D., Harms, L., Hagen, W., Saborowski, R., 2019. Transcriptome analysis of the midgut gland of the brown shrimp Crangon crangon indicates high polymorphism in digestive enzymes. Marine Genomics 43:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Truebano, M., Tills, O., Spicer, J. I., 2016. Embryonic transcriptome of the brackishwater amphipod Gammarus chevreuxi. Marine Genomics 28:5-6. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M., Tills, O., Spicer, J. I., Truebano, M., 2017. De novo transcriptome assembly of the amphipod Gammarus chevreuxi exposed to chronic hypoxia. Mar Genom 33:17-19. [CrossRef]

- Trapp, J., Geffard, O., Imbert, G., Gaillard, J. C., Davin, A. H., Chaumot, A., Armengaud, J., 2014. Proteogenomics of Gammarus fossarum to document the reproductive system of amphipods. Mol Cell Proteomics 13:3612–3625. [CrossRef]

- Waller, S.J., Egan, E., Crow, S. et al., 2024. Host and geography impact virus diversity in New Zealand’s longfin and shortfin eels. Archives of Virology, 169:85. [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, A., Manoharan, M., 2020. Dengue Virus. Emerging and Reemerging Viral Pathogens, 281–359. [CrossRef]

- Westaway, E. G., Brinton, M. A., Gaidamovich Sya, Horzinek, M. C., Igarashi, A., Kääriäinen, L., Lvov, D. K., Porterfield, J. S., Russell, P. K., Trent, D. W., 1985. Flaviviridae. Intervirology 24(4):183-192. [CrossRef]

- Lindenbach, B. D., Murray, C. L., Thiel, H-J., Rice, C. M., 2013. Flaviviridae, p 712–746. In Knipe, D. M., Howley, P. M., Cohen, J. I., Griffin, D. E., Lamb, R. A., Martin, M. A., Racaniello, V. R., Roizman, B. (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- ViralZone Flaviviridae. Available at: https://viralzone.expasy.org/43 (accessed May 27, 2024).

- Taniguchi, S., 2019. Detection of Jingmen tick virus in human patient specimens: emergence of a new tick-borne human disease? EBioMedicine 43:18-19. [CrossRef]

- Moureau, G., Cook, S., Lemey, P., Nougairede, A., Forrester, N. L., Khasnatinov, M., Charrel, R. N., Firth, A. E., Gould, E. A., de Lamballerie, X., 2015. New Insights into Flavivirus Evolution, Taxonomy and Biogeographic History, Extended by Analysis of Canonical and Alternative Coding Sequences. PLoS ONE 10(2):e0117849. [CrossRef]

- Firth, A. E., Blitvich, B. J., Wills, N. M., Miller, C. L., Atkins, J. F., 2010. Evidence for ribosomal frameshifting and a novel overlapping gene in the genomes of insect-specific flaviviruses. Virology, 399(1), 153–166. [CrossRef]

- Melian, E. B., Hinzman, E., Nagasaki, T., Firth, A. E., Wills, N. M., Nouwens, A. S., Blitvich, B. J., Leung, J., Funk, A., Atkins, J. F., Hall, R., Khromykh, A. A., 2010. NS1’ of flaviviruses in the Japanese encephalitis virus serogroup is a product of ribosomal frameshifting and plays a role in viral neuroinvasiveness. Journal of Virology 84(3):1641-1647. [CrossRef]

- Firth, A. E., Brierley, I., 2012. Non-canonical translation in RNA viruses. Journal of General Virology 93:1385-1409. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S., Kuhn, R. J., Rossmann, M. G., 2005. A structural perspective of the flavivirus life cycle. Nature reviews. Microbiology 3(1):13-22. [CrossRef]

- Bamford CGG, de Souza WM, Parry R, Gifford RJ. 2022. Comparative analysis of genome-encoded viral sequences reveals the evolutionary history of flavivirids (family Flaviviridae), Virus Evolution, Volume 8, Issue 2, 2022, veac085. [CrossRef]

- Parry RH, Slonchak A, Campbell LJ, Newton ND, Debat HJ et al. A novel tamanavirus (Flaviviridae) of the European common frog (Rana temporaria) from the UK. J Gen Virol 2023;104(12).

- Imsland, A. K., Reynolds, P., Eliassen, G., Hangstad, T. A., Nytrø, A. V., Foss, A., Vikingstad, E., Elvegård, T. A., 2014. Assessment of Growth and Sea Lice Infection Levels in Atlantic Salmon Stocked in Small-Scale Cages with Lumpfish. Aquaculture 433:137-142. [CrossRef]

- Haugland, G. T., Imsland, A. K. D., Reynolds, P., Treasurer, J., 2020. Chapter 10 Application of biological control: use of cleaner fish. In: Kibenge, F. S. B., and Powell, M. D. (Eds.), Aquaculture Health Management: Design and Operational Approaches. Elsevier, Amsterdam. pp. 319-369. [CrossRef]

- The Health Situation in Norwegian Aquaculture 2020. Published by the Norwegian Veterinary Institute 2021. Available on line, Sommerset, I., Jensen, B. B., Bronø, G., Haukaas, A., Brun, E. (Eds.). 2021. The Health Situation in Norwegian Aquaculture 2020. Published by the Norwegian Veterinary Institute 2021. Available on line: https://www.vetinst.no/rapporter-og-publikasjoner/rapporter/2022/fish-health-report-2021/_/attachment/inline/3a529735-e485-4bf7-b05b-5677a46b6b09:31cb9146509882b4dc2c60dc915a1be6195ae015/Norwegian%20Fish%20Health%20Report%202021.pdf (accessed December 27 2025).

- Crandell JG, Altera AK, DeRito CM, Hebert KP, Lim EG, Markis J, Philipp KH, Rede JE, Schwartz M, Vilanova-Cuevas B, Wang E and Hewson I., 2023. Dynamics of the Apostichopus californicus-associated flavivirus under subtoxic conditions and organic matter amendment. Frontiers in Marine Science 10:1295276. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q., Qian, L., Gu, S., Guo, X., Zhang, X., Sun, L., 2020. Investigation of growth retardation in Macrobrachium rosenbergii based on genetic/epigenetic variation and molt performance. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics, 35:100683. [CrossRef]

- Hooper, C., Debnath, P. P., Stentiford, G. D., Bateman, K. S., Salin, K. R., Bass, D., 2022. Diseases of the giant river prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii: A review for a growing industry. Reviews in Aquaculture 1-21. [CrossRef]

- FAO, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Global production by production source Quantity (1950–2022). Available at: https://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics-query/en/global_production/global_production_quantity (accessed July 23, 2024).

- Zhou D, Liu S, Guo G, He X, Xing C, Miao Q, Chen G, Chen X, Yan H, Zeng J, Zheng Z, Deng H, Weng S, He J. 2022. Virome Analysis of Normal and Growth Retardation Disease-Affected Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Microbiology Spectrum 10(6):e0146222. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R., Zhang, Z. H., Chen, H., Fang, P., Chen, J., Liu, X. M., Wu, Y. F., Wang, J. J., 2017. Phenomenon and research progress on prevention and control of “Iron Shell” in giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Fish Sci 36:383-390.

- Wang, G., Guo, X., Huang, X., Wang, D., Chen, Y., Qin, J., Yang, G., Tang, K. F. J., Dong, X., Huang, J., 2023. The quantitative characteristics of infection with infectious precocity virus (IPV) revealed with a new TaqMan probe-based real-time RT-PCR method. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y-R., Lu, Y-Y., Lin, H-Y. 2024. Quantitative analysis of infectious precocity virus load and stunted growth syndrome via an immunohistochemical assay and reverse transcriptase quantitative real-time PCR in Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquaculture 583, 740577. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H. Y., Shao, G. M., Kang, P. F., Wang, Y. F., 2017. Full-length normalization subtractive hybridization analysis provides new insights into sexual precocity and ovarian development of red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Aquaculture 468, 417–427. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., Miu, Q., Liu, S., Zhou, D., He, X., Pang, J., Weng, S., He, J. 2023. Detection methods, epidemiological investigation, and host ranges of infectious precocity virus (IPV). Aquaculture 562, 738818. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C., Wang, G., Zhou, Q.; Meng, F.; Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Dong, X. 2025. Surveillance and Genomic Evolution of Infectious Precocity Virus (IPV) from 2011 to 2024. Viruses 17, 425. [CrossRef]

| Family | Genus2 | Species | Virus name | GenBank Acc. No | Host | Reference(s) |

| Flaviviridae | Orthoflavivirus (Sub-genus Euflavivirus) | Orthoflavivirus dengue | Dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2) | U87411 | Primates & insects | [2] |

| Orthoflavivirus (Sub-genus Crangovirus) | Orthoflavivirus alphei | Crangon crangon flavivirus (CcFV) | MK473878 | Brown shrimp (Crangon crangon) | [2,10,38] | |

| Gammarus chevreuxi flavivirus (GcFV) | QCH00712.1 | Gammaridean amphipod (Gammarus chevreuxi) | [10,39,40] | |||

| Gammarus pulex flavivirus (GpFV) | QCH00716.1 | Gammaridean amphipod (Gammarus pulex ) | [10,31] | |||

| Wenzhou shark flavivirus (WZSFV) | AVM87250.1 | Pacific spadenose shark (Scoliodon macrorhynchos); gazami crab or Japanese blue crab (Portunus trituberculatus), | [10,37] | |||

| Eastern red scorpionfish flavivirus (ERsfFV)* |

MH716818 | Ray-finned fish eastern red scorpionfish (Scorpaena jacksoniensis) | [19] | |||

| Tamanavirus | Tamanavirus parnellis | Tamana bat virus (TABV) | AF285080 | Parnell’s mustached bat (Pteronotus parnellii) | [2] | |

| Tamanavirus | Cyclopterus lumpus virus (CLuV) | MF776369 | Lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) | [20,33] | ||

| Lumpfish flavivirus (LuFV)* | NC_040555 | Lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) | [20] | |||

| Western carp gudgeon flavivirus (WCgFV)* | MW645033 | Western carp-gudgeon (Hypseleotris klunzingeri) | [22] | |||

| Lineage Ie | Salmon flavivirus (SFV) | MT075326.2 | Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) | [2,21] | ||

| Lineage Ij | Infectious precocity virus (IPV) | MT084113 | Giant freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) | [2,13] | ||

| Gammarus pulex flavivirus (GpFV) | MK473881 | Gammaridean amphipod (Gammarus pulex ) | [10,41] | |||

| Jingmenvirus | Jingmenvirus rhipicephali | Jīngmén tick virus (JMTV) | KJ001579 - KJ001582 | Ticks & mammals | [2] | |

| Jingmenvirus | Changjiang Jingmen-like virus | APG76081 | Crayfish | [18] | ||

| Pestiviridae | Orthopestivirus | Orthopestivirus bovis | bovine viral diarrhea virus 1 (BVDV1) | M96751 | Cattle | [2] |

| Wenzhou pesti-like virus 1 (WZPLV-1)* | MG599982 | Scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini) | [19,37] | |||

| Wēnlǐng pesti-like virus 2 (WLPLV-2)* | MG599983 | Graceful catshark (Proscyllium habereri) | [19,37] | |||

| Nanhai dogfish pesti-like virus (NDfPLV)* | MG599984 | Japanese shortnose spurdog (Squalus brevirostris) | [19,37] | |||

| Xiàmén fanfray pesti-like virus (XFfPLV)* |

MG599985 | Fanrays (Platyrhina sp) | [19,37] | |||

| Hepaciviridae | Orthohepacivirus | Orthohepacivirus hominis | hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1a | AF009606 | Humans | [2] |

| Wenling shark virus (WLSV) | NC_028377 | Graceful catshark (Proscyllium habereri) | [18] | |||

| Xiàmén guitarfish hepacivirus (XgHCV)* | MG599991 | Ringstreaked guitarfish (Rhinobatos hynnicephalus) | [19,37] | |||

| Xiàmén sepia Stingray hepacivirus (XsSHCV)* | MG599992 | sepia stingray (Urolophus aurantiacus) |

[19,37] | |||

| Western African lungfish hepacivirus (WAlHCV) | MG599993 | West African lungfish (Protopterus annectens) | [19,37] | |||

| Guangxi houndshark hepacivirus (GhHCV) | MG599998 | Starspotted smooth-hound (Mustelus manazo) | [19,37] | |||

| Nanhai dogfish shark hepacivirus (NdshHCV)* | MG599995 | Japanese shortnose spurdog (Squalus brevirostris) | [19,37] | |||

| Nanhai ghost shark hepacivirus 1 (NgshHV 1) | MG599996 | Ghost sharks (Chimaera sp) |

[19,37] | |||

| Nanhai ghost shark hepacivirus 2 (NgshHV 2) | MG599997 | Ghost sharks (Chimaera sp) |

[19,37] | |||

| Lineage IIIt | Wenling moray eel hepacivirus (WmeHCV) | MG599990 | Moray eel (Gymnothorax reticularis) | [2,19] | ||

| Longfin eel flavivirus (LeFV)* | OR863209 | Longfin eel (Anguilla dieffenbachii) | [42] | |||

| Shortfin eel flavivirus 1 (SeFV1)* | OR863218 & OR863219 | Shortfin eel (Anguilla australis) | [42] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).