1. Introduction

Currently, Puerto Rico is a commonwealth of the United States as it holds a territory status. Its healthcare system models that of the continental United States, including both public and private sectors [

1]. However, in recent decades, the healthcare system has undergone major changes and challenges that have put strain on the population of the island. The major avenues through which these effects are seen include decreased availability of care for the aging population, regionalization of healthcare services, and physician migration creating a physician shortage on the island [

1]. Understanding how other countries address similar challenges could offer valuable insight, highlighting both successful strategies and mistakes that might be relevant for Puerto Rico’s context.

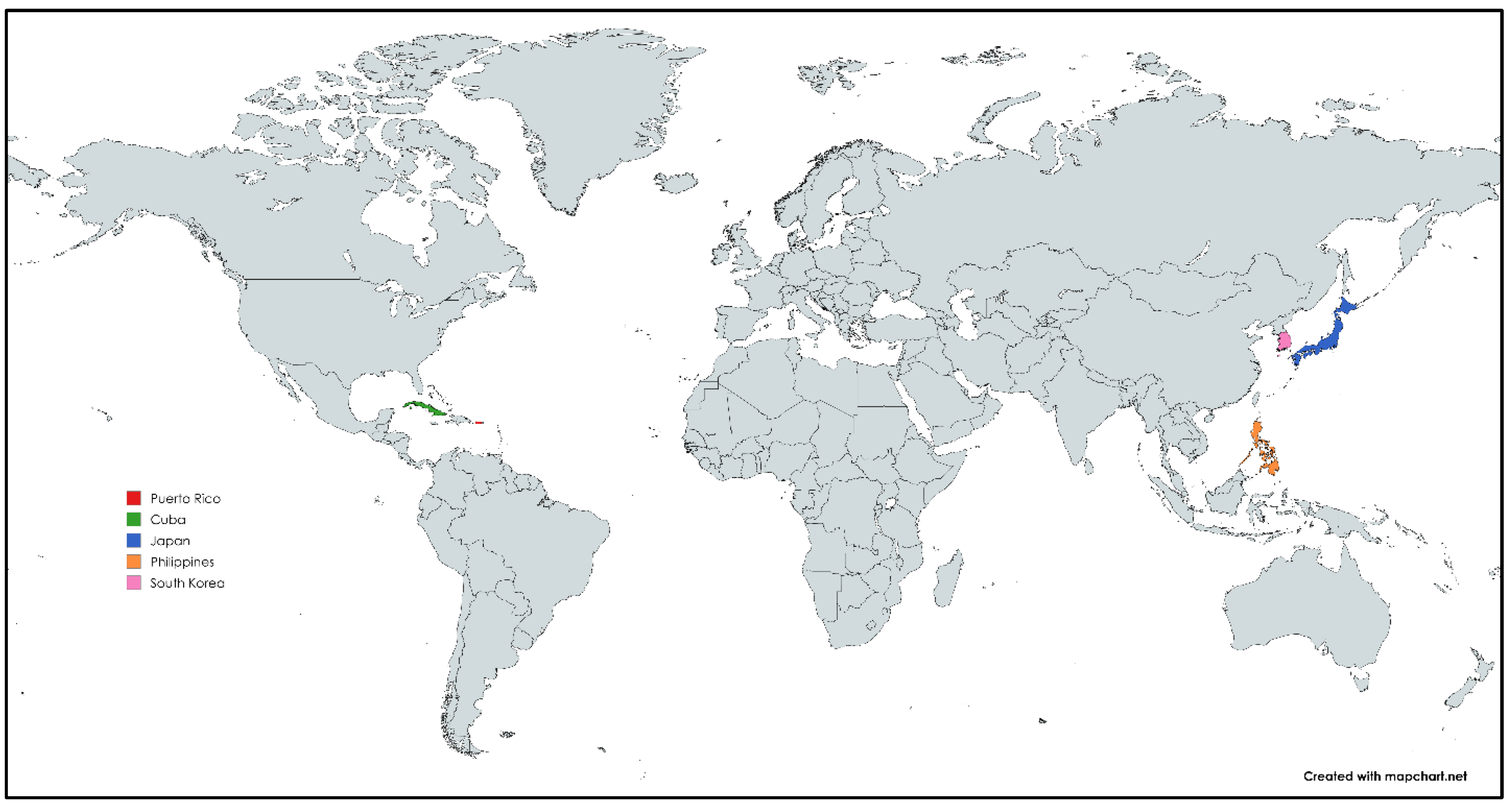

To further understand the etiology of each issue and create a basis for the development of solutions, the current study initially considered comparing the healthcare system of Puerto Rico to those of twelve other countries. Ultimately, countries that have attempted to solve the problems of either an aging population or of mass youth/workforce migration. The second rationale was to assess the healthcare infrastructure and demographic comparability of countries. The case study selection resulted in four cases being picked to be compared to the case of Puerto Rico. The countries selected were Cuba, Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea (

Figure 1).

Cuba was selected for its history in addressing physician shortages and universal healthcare system with a strong emphasis on preventative care and public health [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Japan was chosen due to its similarity to Puerto Rico in terms of an aging population, while also having a well-developed universal healthcare model and long-life expectancy [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The Philippines was analyzed because of its similar challenges with regional disparities and mixture of public and private healthcare infrastructure [

10,

11,

12]. Lastly, South Korea due to the multitude of measures taken to address their healthcare problems in regionalization of available medical care and low birth rates [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Table 1 provides a general overview of the territorial and demographic traits of each country. All four of them were analyzed regarding their past and present challenges in the healthcare sector, the approaches they have taken to combat these issues, and their insights for Puerto Rican healthcare.

2. Literature Review

2.1. the Global Aging Population Trend

Globally, populations are aging due to increased life expectancy and decreasing birth rates. In 2020, less than 30% of countries were considered aged societies (with 14% of the population above age 65), and only one country, Japan, will be considered an ultra-aged society (where 21% of the population is above age 65). By 2050, it is projected that these numbers will shift so that 58% of countries qualify as an aged society and 15% will be in an ultra-aged society [

17]. As of 2022, the countries and regions with the highest percentages of their population above 65 years old were Monaco, Japan, Saint Helena, Italy, Finland, and Puerto Rico [

18]. However, in projections for 2100 based on current trends, the top countries and regions are likely to be Albania, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, South Korea, and Jamaica [

18].

This upwards trend in age across the globe can be partially tied to decreasing birth and mortality rates, as public health, biotechnology and medicine continue to improve. The development and accessibility of birth control methods, in addition to measures put in place to decrease infant mortality, have contributed to declining birth rates as well [

19]. From 1950 to 2050, the global total fertility rate is projected to drop from 5 children born per woman on average to 2.25. Increases in lifespan and longevity have also contributed to the increase in the average age worldwide. Medical advances and decreases in unhealthy practices, such as tobacco usage, have allowed people to live longer on average, seen in the rise of life expectancy from 47 years in 1950 to 70 years in 2010 [

19].

2.2. Healthcare Strains Due to Aging Populations

As individuals age, the prevalence of chronic conditions such as diabetes, osteoarthritis, depression, and dementia increases, requiring long-term care and ongoing monitoring, that raises the demand for healthcare services [

20,

21]. Adults over 65 use medical services at a rate 20% higher than young adults and are hospitalized three times more frequently [

22]. When systems cannot meet this rising demand, they become strained. Additionally, the need for long-term care facilities grows, as they are primarily utilized by individuals over the age of 60 [

23]. Aging populations are a major driver of rising healthcare expenditures, particularly as long-term care costs begin to surpass in-patient, out-patient, and ambulatory care after age 60 [

23,

24]. Alongside rising costs, aging populations contribute to labor shortages across sectors, including healthcare. For example, in Japan limited physician availability and a shortage of end-of-life care facilities contribute to unmet healthcare needs [

25]. Similarly, Puerto Rico experiences a physician shortage, exacerbated by wage disparities between the island and the mainland United States [

26]. Many physicians migrate in search of better resources, wages, and working conditions-a trend seen in Puerto Rico and other countries across the globe.

2.3. Global Physician Migration Trends

Physician migration has profound impacts on the healthcare systems in places across the world, whether from an oversupply of staff to a lack of healthcare providers, which is the more common alternative. In recent years, member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of 38 countries with developed and emerging economies, have seen increases in physician and nurse migration into their healthcare systems [

27,

28]. As a result, low- and middle-income countries often suffer from this outflux of their physicians [

28]. Medical personnel have been found to migrate often in search of better career and job opportunities, and compensation, while also moving to avoid safety issues in their home countries including political corruption, rising unemployment, an increase in xenophobia attacks, and instances of murders that target migrants, as seen in a systematic review that saw these trends present across the world, most prevalently in South Africa, India, and the Philippines [

29]. These physician shortages in turn impact the quality of care available in these countries, patient wait times, and hospitalization rates, further straining the healthcare system in each country experiencing a shortage [

30,

31].

To combat the outmigration of healthcare personnel, various countries have implemented approaches to address this and other challenges present in their healthcare systems. Countries including South Korea, Australia, and South Africa, among others, have implemented financial incentives and and/or loan repayment programs to incentivize providers and nurses to stay [

32,

33]. More tailored programs have also been developed by countries such as India and the Philippines to expand healthcare resources available in their rural regions [

34,

35,

36]. Programs such as these can serve as models for the future development of initiatives in regions and countries undergoing similar challenges, such as Puerto Rico.

3. Methodology

The study employed a comparative case study analysis to gather relevant information from academic papers, news sources, and publicly available data about the healthcare system in Puerto Rico and other cases throughout the world. The primary objective of this comparative analysis is to establish a comprehensive background on key areas of interest: the global trend of aging populations, the subsequent healthcare strains experienced in different countries, and patterns of physician migration. These areas were critical for understanding how demographic and workforce challenges interacted to shape healthcare systems worldwide. The study explored the pressures on healthcare systems in rapidly aging populations by comparing Puerto Rico, Cuba, Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea.

To facilitate this analysis, the authors organized each country case study around four standardized areas of comparison:

Each selected case study was examined to determine which of these factors apply, allowing the authors to assess the extent to which each case was similar or dissimilar to Puerto Rico. By structuring the data in this manner, the authors could effectively identify patterns and differences that emerged across cases.

The magnitude and presence of these factors within each country were analyzed as the authors assessed the degree of aging-related demographic shifts, physician shortages or migration challenges, and the overall accessibility and distribution of healthcare services. Additional attention was given to regional disparities, as differences in healthcare access within countries provided insight into how geographic and socio-economic variations affected healthcare delivery. By systematically comparing these factors across different countries, the authors could identify cases that share key characteristics with Puerto Rico and highlight specific areas where Puerto Rico’s healthcare system faced unique challenges. This structured approach ensured a comprehensive understanding of various healthcare systems, allowing the authors to draw meaningful conclusions regarding Puerto Rico’s position within global healthcare trends.

The authors initially selected 12 countries for the initial comparative study—Canada, South Korea, Australia, South Africa, India, the Philippines, Germany, Italy, Japan, Cuba, Uruguay, and Colombia—based on the similarities or differences their healthcare systems share with Puerto Rico regarding physician shortages, medical service availability, and other issues. Following this initial selection, they evaluated two different rationales to determine which countries they would focus on. The first rationale was to consider countries that have attempted to solve the problems of either an aging population or of mass youth/workforce migration. The second rationale was to assess the healthcare infrastructure and demographic comparability of countries. Ultimately, the countries that were selected for further analysis were Cuba, Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea. These countries were chosen because they face comparable issues such as aging populations; physician shortages; “brain drains,” which is when a country faces an export of skilled workers [

37]; and regional healthcare disparities between rural and urban areas, making them ideal for comparison. The authors’ research involved reviewing existing literature, including academic papers, policy and government reports, and media sources, to gather data on how these nations are dealing with the issues of medical access and healthcare inequality.

Through this process, the authors aim to identify patterns and approaches that could be applied to healthcare systems. By studying the successes and challenges faced by these countries, they sought to build a more comprehensive understanding of the strains on healthcare systems worldwide, which could potentially inform solutions and drive meaningful change for both Puerto Rico and the world’s future healthcare landscape.

4. the Case of Puerto Rico

4.1. Healthcare Model

Puerto Rico’s healthcare system models that of the continental United States, including both public and private sectors [

1]. However, its structure is weakened by dependence on Medicaid block grants. Puerto Rico’s territorial status means Medicaid funding is capped, unlike in U.S. states where it is open-ended, resulting in fewer benefits, reduced drug coverage, and long wait times [

38]. With nearly 40% of the population enrolled in Medicaid, this limitation places severe strain on providers and patients alike [

39].

4.2. Aging Population Policies

The percentage of Puerto Ricans aged 65 or older is one of the highest in the world. Since 2010, this percentage has nearly doubled from 13% to 24% [

40,

41]. This percentage would place Puerto Rico at third highest in the world [

42]. This demographic shift is driven by youth outmigration and a declining fertility rate, presenting a calamitous scenario for the island’s healthcare systems [

41].

Recent estimates place the fertility rate at 0.9 births per woman – half the rate it was in the early 2000s [

43]. This rate is significantly beneath the threshold of 2.1, which is necessary for full population replacement [

44]. Coupled with migratory factors, a declining birth rate also increases the dependency ratio of the island.

Additionally, life expectancy in Puerto Rico was 82 years in 2024 [

45]. While this reflects positive health outcomes, it is coupled with high morbidity, disability, and dependency on care systems [

46], further accentuating the island’s aging profile.

4.3. Workforce Migration

Youth emigration from Puerto Rico is primarily driven by financial incentives and improved job security. With little barrier to entry to the United States, those of working age are incentivized to earn more on the mainland [

47]. Moreover, the median age of migrants in 2022 was 30 years old [

48]. In 2023, the unemployment rate of Puerto Rico was almost double that of the United States [

42].

With high migration rates of Puerto Rican youth to the mainland U.S., the workforce is shrinking, leaving a shortage of physicians, healthcare workers, and caregivers for the island’s elderly population. Since 2014, between 365 and 500 physicians have left the island each year, exacerbating an already critical shortage of medical personnel [

49]. This physician emigration is driven by a combination of economic instability, lack of resources, and rising costs of living, all of which make it difficult for doctors to sustain their practices and personal lives. Additionally, systemic issues within the healthcare system—such as low physician reimbursement rates under Medicaid, institutional corruption, and the increasing control of U.S.-based insurance companies—create an unsustainable working environment, forcing many to seek better opportunities on the mainland [

50].

Healthcare providers in Puerto Rico earn, on average, less than half of what their counterparts make in the mainland U.S., while Medicaid reimbursement rates remain significantly lower than those in the states [

25]. This pay disparity, combined with a lack of financial incentives and resources, continues to drive the exodus of healthcare professionals and weakens Puerto Rico’s medical infrastructure.

4.4. Economic Sustainability of Healthcare System

The economic strain on Puerto Rico’s healthcare system is compounded by political and financial challenges. Puerto Rico’s ongoing financial crisis and massive public debt restrict healthcare funding, making it difficult to invest in medical infrastructure, technology, and workforce retention [

25]. The island’s vulnerability to natural disasters further threatens sustainability. Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 caused

$160 billion in damage [

51], while recovery delays left many patients without life-saving care, contributing to thousands of excess deaths [

52]. These crises exposed deep infrastructural fragilities, including power grid failures that left hospitals unable to function [

53].

The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), enacted in 2016, also reshaped financial management, cutting public services to address debt [

54]. These fiscal constraints, coupled with disaster-related collapses, underscore the difficulty of sustaining long-term healthcare delivery under the current territorial and economic framework.

5. Case Study Comparison: Cuba

Cuba’s healthcare system is known for its universal coverage and strong focus on preventive, community-based care [

4]. Since 1959, Cuba has created a universal healthcare system that offers free medical services to all citizens, despite facing financial obstacles on a federal level, including the United States embargo on trade of food and medical supplies [

1,

4]. The government has also prioritized funding towards research and biotechnology, investing

$1 billion from 1990-1996 in this sector and prompting the creation of the “’The Western Havana BioCluster’” [

55]. This overall approach has led to increased life expectancy and reduced infant mortality. However, the system now faces challenges from an aging population, workforce migration and a severe economic crisis, which impact healthcare delivery and population health.

5.1. Healthcare Model

The National Healthcare System was established in Cuba to provide universal care for its population. It has achieved several successes since its establishment, including a high physician density and the creation of global medical missions. The physician density in Cuba has reached 9.429 physicians per 1000 people in 2021, according to the World Bank, one of the highest physician-to-population ratios globally [

56].

Additionally, Cuba provides international medical relief to developing countries, dispatching over 35,000 medical personnel worldwide, particularly in Haiti and Venezuela [

1,

57]. However, these medical missions have also led to domestic shortages, especially in rural or specialized areas, occasionally delaying care and reducing service quality [

2].

5.2. Aging Population Policies

Cuba is experiencing a significant demographic transition with a declining fertility rate paired with an increasing life expectancy. The fertility rate was 4.01 in the span of 1950–1955, hit a low of 1.45 in 2010–2015, and is projected to rise to 1.66 in 2045–2050 [

58]. Although projected to increase in the coming decades, the overall trend shows a large decrease in the birth rate.

Meanwhile, life expectancy at birth jumped from 59.40 during 1950–1955 to a projected 84.31 for 2045–2050 [

58]. As a result, the percentage of the population aged over 60 years has grown from 7% to a projected 36.3% in 2050, compared to a projected 23% for Latin America overall and 31% among developed countries.

The aging population has led to an increased prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular conditions [

1], necessitating long-term management and specialized geriatric care. This places additional strain on medical facilities and resources, which are already limited due to economic challenges.

5.3. Workforce Migration

Cuba has historically experienced significant physician emigration. Following the 1959 revolution, approximately 1,402 physicians left for the United States, creating a notable gap in care [

3]. In response, the Cuban government prioritized medical education, leading to a substantial increase in the number of trained physicians. Yet, international medical missions have at times reduced the supply of providers at home. For instance, when more than 8,000 Cuban physicians were withdrawn from Brazil in 2018 after disputes over contractual conditions, the sudden shift disrupted both Cuba and Brazil’s systems [

57].

5.4. Economic Sustainability of Healthcare System

To manage long-term demographic and workforce pressures, Cuba has invested in aging-related policies and programs. The

Programa de Atención al Anciano (Program to Care for the Elderly) was established to improve health outcomes by implementing continuous follow-ups on elderly members via community health centers (policlinicas) [

59]. In this model, family physicians first evaluate elderly patients and then refer them to geriatric providers as needed. Similarly, the Family Physician and Nurse Program—established in the 1980s—focuses on preventive care, with teams responsible for 600–800 community members (up to 1500 in some areas), emphasizing early detection of age-related conditions [

1].

The Rural Medical Service (RMS), launched in the 1960s and expanded in the 1970s, distributed newly graduated physician volunteers to underserved areas, increasing provider availability in rural communities [

1]. The Ministry of Public Health also expanded medical and nursing programs in provincial areas during the 1970s, offered free tuition, and prioritized academic merit in admissions, expanding opportunities for disadvantaged students [

1].

Together, these initiatives demonstrate Cuba’s commitment to sustaining its system despite economic sanctions and limited resources. Yet, persistent financial hardship and outmigration continue to challenge the long-term sustainability of healthcare delivery.

Table 2 presents a summary of the case study comparison between Puerto Rico and Cuba, following the main themes/factors discussed in this study.

6. Case Study Comparison: Japan

Similar to Puerto Rico, Japan faces significant challenges due to an aging population. While healthcare workforce migration is relatively low, the high prevalence of chronic disease among the elderly continues to strain healthcare resources. A declining birth rate further contributes to this strain, as healthcare workers retire later to meet growing demand. This case study examines how Japan’s aging population impacts its healthcare system and explores government efforts to expand elder care and address the nation’s declining birth rate.

6.1. Healthcare Model

Japan has a universal healthcare system combining public insurance with a mix of public and private providers. Coverage is nearly comprehensive, but demographic pressures have led to heavy utilization of long-term care services and greater dependence on geriatric infrastructure [

5].

6.2. Aging Population Policies

Japan’s population is the most aged in the world, with 27.7% aged 65 or older, projected to reach 38.4% by 2038 [

5]. One factor contributing to an aging population is life expectancy, with Japan having the highest in the world: 81 years for men and 87 for women in 2016 [

7]. Although these figures reflect strong health outcomes, without a stable fertility rate, they place immense burden on healthcare infrastructure.

The fertility rate is among the lowest globally, at 1.33 [

60]. With 2.1 births per woman required for replacement, Japan’s population has steadily declined since the 1970s [

5]. Younger generations increasingly cite economic hardship, work pressures, and cost of living as reasons for not having children [

15].

A Tokyo-based study indicated that over 90% of adults in Japan aged 75+ suffer from at least one chronic disease, and 80% live with two or more [

61]. These health burdens require significant long-term and geriatric care expansion.

Policies to address these challenges began with the “Gold Plan” (1980s), a 6 trillion yen initiative to expand long-term care facilities. Though expanded in 1994, demand soon outpaced capacity [

5]. Similarly, the 1982 Health and Medical Services Act encouraged healthy aging and promoted nursing homes, but unmet demand produced widespread dissatisfaction [

5].

Fertility-focused initiatives included mandated parental leave (introduced in 1992 and later expanded) and financial stipends for children up to age 9. However, inconsistent government follow-through limited effectiveness [

62].

6.3. Workforce Migration

Japan has relatively low emigration of healthcare professionals but suffers severe internal labor strain. By the end of 2025, the country is projected to need an additional 2 million nurses and caregivers [

63]. To meet this demand, Japan has relied on foreign workers, especially from Southeast Asia.

Due to workforce shortages, the current healthcare workforce is broadly overworked and delays retirement. This has produced some of the highest rates of burnout and depression among healthcare professionals globally [

64]. Rural areas face extended wait times, and many residents increasingly turn to private providers for quicker access [

64].

6.4. Economic Sustainability of Healthcare System

Japan’s response to demographic pressures reflects both ambition and inconsistency. While initiatives such as the Gold Plan and Health and Medical Services Act expanded eldercare, early underestimation of demand undermined sustainability [

5]. Fertility-support programs also suffered from uneven implementation and insufficient outcomes [

62].

The long-term sustainability of Japan’s healthcare system depends on balancing a shrinking labor pool, rising eldercare demand, and escalating fiscal burdens. Despite substantial government investment, structural demographic decline continues to threaten future viability.

Table 3 presents a summary of the case study comparison between Puerto Rico and Japan, following the main themes/factors discussed in this study.

7. Case Study Comparison: the Philippines

The Philippines, like Puerto Rico, faces major healthcare challenges due to labor migration, economic instability, and unequal access to care. High rates of healthcare worker migration, an overburdened system, and limited long-term care for an aging population strain the country’s resources. This case study examines the Philippine healthcare system through labor migration, rural access, and reforms under the Universal Health Care (UHC) Act, comparing these trends with Puerto Rico to highlight shared challenges and differing approaches.

7.1. Healthcare Model

The Philippines implemented the Universal Health Care (UHC) Act in 2019, aiming to provide all citizens with equitable access to healthcare services. Key features and challenges include financial constraints and healthcare infrastructure disparities. Despite the expansion of healthcare under the UHC Act, finances remain a critical issue, with highly fragmented pieces across national vs. local governments and the public vs. private sector [

10]. Inequities across urban areas and rural and underserved regions persist, due to differences in accessibility to healthcare and allocation of resources [

10].

PhilHealth was designated as the national strategic purchaser of health services under the UHC Act, tasked with improving efficiency, equity, and financial protection. While PhilHealth introduced reforms to expand benefit packages and simplify eligibility, implementation has been hampered by payment delays, weak provider engagement, and underinvestment in digital infrastructure [

10].

The UHC Act indicated a shift from curative medicine toward health promotion and prevention. The Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine has advocated for incorporating prevention-focused strategies such as culinary education, agricultural integration, and physician training in telemedicine as part of a stronger primary care model [

11].

7.2. Aging Population Policies

The Philippines does not yet face the same demographic pressure as Puerto Rico. With just 5.26% of its population aged 65 or older in 2023, it is not expected to become an aging society until 2030 [

40,

65]. In contrast, Puerto Rico already has 24.0% of its population aged 65+.

Currently, the Philippines relies heavily on families to care for elderly members. However, as employment rates rise and family caregiving capacity decreases, the need for eldercare services is projected to grow. Calls for innovation include proposals to integrate elderly assistance for household tasks, medical needs, and social support into mobile application platforms [

66]. These approaches could reduce caregiver burden and promote independence but require investment in infrastructure and digital literacy.

7.3. Workforce Migration

The Philippines is one of the world’s leading exporters of healthcare workers, particularly nurses, to countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Saudi Arabia [

36]. This “brain drain” undermines the availability of medical professionals domestically, leaving hospitals and clinics understaffed [

67]. As of 2020, the Philippines had only 19.7 healthcare workers (physicians, nurses, midwives, dentists) per 10,000 population—far below the WHO benchmark of 44.5 [

68].

To mitigate shortages, the government has introduced Bilateral Labor Agreements (BLAs) with countries like Canada and South Korea. These aim to regulate migration ethically but often benefit receiving countries more than the Philippines, since enforceable reinvestment provisions remain weak [

69]. Deployment caps were also introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, limiting health worker emigration to 5,000 in 2021 and 7,500 in 2022 [

70].

While remittances from overseas Filipino workers strengthen the national economy, the loss of skilled professionals continues to erode healthcare delivery. Government attempts at offering financial incentives for retention or repatriation have been limited in impact, and nurses still migrate to destinations outside BLAs, particularly the U.S. and Saudi Arabia [

36].

7.4. Economic Sustainability of Healthcare System

Sustaining healthcare delivery under these conditions requires addressing both financial fragmentation and rural access disparities. The Philippine National Rural Physician Deployment Program attempted to place physicians in underserved areas, but retention remained low: from 1993–2011, only 18% of physicians stayed in their assigned municipalities [

35]. Incentives such as community respect, competitive pay, and career opportunities helped retention, while poor infrastructure and weak government support drove attrition [

35].

The Special Health Fund was designed to improve financing mechanisms by supporting population health services, infrastructure, and healthcare worker incentives [

71]. Recent rural pilot sites also demonstrated that targeted interventions—including provider network expansion, subsidized transportation, technical training, community engagement, and electronic health record implementation—significantly improved outpatient consultations and reduced out-of-pocket spending [

72].

Together, the UHC Act, rural access initiatives, and workforce migration policies represent an ongoing but incomplete effort to achieve sustainable healthcare delivery in the Philippines. Financial fragmentation, migration outflows, and limited infrastructure continue to threaten long-term viability.

Table 4 presents a summary of the case study comparison between Puerto Rico and The Philippines, following the main themes/factors discussed in this study.

8. Case Study Comparison: South Korea

South Korea faces a major demographic crisis marked by an aging population and declining birth rates. As a super-aged society, 20% of its population is over 65, a figure expected to reach roughly 40% by 2050—placing significant strain on the economy and healthcare system [

73]. Labor shortages, especially in caregiving and healthcare, have emerged due to workforce migration, prompting government action [

74]. This case study examines how South Korea’s healthcare policies respond to these challenges, focusing on the National Health Insurance (NHI) system, long-term care, technology, workforce strategies, and legislation.

8.1. Healthcare Model

South Korea’s National Health Insurance (NHI) system, established in 1989, provides universal healthcare coverage but is financially strained due to rising costs of elderly care [

75]. Contributions from the shrinking working-age population are insufficient to cover expenses, leading to frequent premium increases and reliance on government subsidies [

76]. These temporary measures raise questions about long-term solvency [

77].

Recognizing the need for aging support, South Korea also launched the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) program in 2008. The LTCI expanded services for the elderly, but shortages of professional care workers and heavy reliance on informal caregivers limit its effectiveness [

78]. Rising demand has already outpaced contributions, leading to financial instability [

13]. Although roughly 90.9% of respondents report satisfaction with LTCI [

79], sustainability remains uncertain as population aging accelerates.

South Korea has also integrated technological innovations, particularly during COVID-19. A machine-learning triage system used patient-generated health data to guide treatment urgency [

80]. “CareCall,” a call-based dialog agent, facilitated monitoring of patients remotely and reduced unnecessary hospitalizations [

81]. These initiatives optimized delivery during acute crises but do not resolve structural issues of labor shortages, rural disparities, and digital literacy barriers.

8.2. Aging Population Policies

South Korea’s demographic crisis is driven by increased life expectancy, a record-low fertility rate (0.78 in 2022), and rapid urbanization [

82]. These factors elevate healthcare costs, increase the dependency ratio, and shrink the tax base that sustains social services.

These shifts mirror broader East Asian trends but are especially acute in South Korea, where delayed marriage, smaller families, and gendered social norms accelerate population decline. The scale and speed of change raise urgent questions about how policies will adapt to these cultural and demographic pressures.

8.3. Workforce Migration

South Korea has sought to address labor shortages through temporary migration policies. The Employment Permit System (EPS) recruits low-skilled workers from 16 countries to serve in healthcare and caregiving roles, aiming to alleviate shortages and reduce recruitment corruption [

83].

While EPS provides short-term relief, it perpetuates instability. Migrant workers often receive lower wages, fewer protections, and limited integration opportunities [

84,

85,

86]. They face barriers to housing, social benefits, and residency [

74]. Reports highlight longer working hours, lower pay, restricted union rights, and greater exposure to abuse compared to local workers [

87].

This dependence on migrant labor reflects a global trend: high-income nations increasingly rely on foreign caregivers while failing to ensure equitable protections. The result is a segmented labor market that undermines sustainability of care delivery.

8.4. Economic Sustainability of Healthcare System

South Korea’s health financing model faces long-term sustainability challenges. The NHI and LTCI, while foundational, are under financial strain from high utilization and insufficient contributions. Subsidies have temporarily bridged gaps, but structural reforms to broaden revenue sources are still needed [

76].

Reliance on informal caregiving and temporary migrant workers creates additional fragility, as both are unstable supports for a rapidly aging population. Without systemic reforms to stabilize workforce supply and adapt financing structures, the sustainability of South Korea’s healthcare system remains at risk.

Table 5 presents a summary of the case study comparison between Puerto Rico and South Korea, following the main themes/factors discussed in this study.

9. Main Challenges and How Other Countries Are Tackling Them

Puerto Rico’s healthcare system is currently navigating a confluence of crises: an aging population, persistent healthcare workers and youth migration, and a bifurcated healthcare financing structure. These interconnected challenges have exposed systemic weaknesses, worsened by economic instability and disasters, and require urgent, multidimensional responses.

9.1. Aging Populations

Cuba faced a healthcare worker shortage in the 1960s due to the outflux of young people following political turmoil and currently faces decreasing fertility rates coupled with high life expectancies [

1]. However, the response seen in improving medical education system and embedding providers in communities has aided this transition. On the other hand, the Philippines, though younger demographically, does not have as robust of long-term care models in place for their elderly populations [

88]. Japan stands on the opposite of this trend with an increasing older population with a concerning imbalance of age within their population [

89]. To combat this and the burden it holds for healthcare, they have implemented financial incentives for boosting the fertility rate and put forth significant funding to expand long-term care in healthcare, as seen in the Health and Medical Services Act [

90]. Additionally, through investment in geriatric facilities and home-based chronic care program in areas of dense populations, Japan seeks to treat its aging population [

91]. Lastly, South Korea’s aging crisis is driven by low fertility, longer lifespans, and rural depopulation, causing an increase in the demand for long-term care amid a shrinking workforce [

92].

Based on the challenges faced by other countries and their responses due to shifting demographics, Puerto Rico, with a high elderly population, should invest in community-based care, a promotion of medical education and an integration of foreign workers within the healthcare system of the island. To help stimulate these solutions, Puerto Rico can focus on monetary and economic incentives to help attract the personnel needed for relief of the healthcare burden. Such incentives include offering caregiver support stipends, tax credits, and caregiver training programs to expand home-based elder care and fill gaps in medical care and attention.

9.2. Healthcare Workforce Retention and Development

The Philippines faces similar issues with the global export of nurses and doctors. To manage this “brain drain,” it has implemented bilateral labor agreements (BLAs) with ethical recruitment policies, and deployment caps [

93]. As it remains federal territory of the United States, Puerto Rico is unable to manage its own migration policy without some level of federal oversight [

94]. However, it can explore retention strategies, such as location-based pay incentives and specialized rural healthcare fellowships, modeled after rural physician programs in the Philippines and Cuba. Similar strategies were seen to be effective in Cuba after the revolution in 1959 to combat the migration of skilled professionals out of the country. These initiatives included expanding medical education opportunities and decreasing the financial burdens of medical education for students [

1].

Promoting island-based medical practice can also help Puerto Rico with worker retention. Acts 20 and 22, which promote corporate investment and immigration to Puerto Rico respectively, can potentially be re-used to provide benefit to long-term residents of the island [

95]. However, a promotion/expansion of these policies may inadvertently contribute to the wealth divide that already exists on the island, as even through their current state, non-immigrant Puerto Ricans still pay up to 10% more of effective tax than the Act 20 and 22 beneficiaries [

96].

South Korea and Japan, on the other hand, have spent money and resources attracting healthcare workers to the country. However, this model is not sustainable due to temporary visas and a lack of worker protection and integration. With high turnover, South Korea has an unstable workforce [

97]. To mitigate this issue, investing resources into incentivizing and providing migrant workers with fair rights and wages would attract foreign healthcare workers in a more stable manner. Japan has extended retirement ages and encouraged older adults to remain in the workforce to sustain its healthcare workforce among rising demand [

8]. While Puerto Rico faces more migration-driven workforce shortages, similar retention strategies—paired with burnout prevention policies involving flexible work hours and mental health support—may enhance provider longevity and reduce system strain.

9.3. Public Vs. Private Healthcare Financing

South Korea’s National Health Insurance (NHI) and Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) programs illustrate the impact of universal coverage frameworks [

12]. Despite their own fiscal challenges, they provide a model for centralized, equitable healthcare access. The Philippines’ Universal Health Care (UHC) Act also offers lessons in how a national system and strategic investments can reduce disparities [

9].

While Puerto Rico may not have full autonomy to reform Medicaid, it can incentivize more doctors, specifically those that have private practices, to accept Medicaid - especially for aging and low-income populations. This can lead to better coordination of care across the island. Additionally, reformation of the Medicaid-capped Block Grant would make significant impacts on services available to the residents. Although these solutions would make healthcare services more accessible economically, the physical restriction of a lack of healthcare infrastructure would still render physical issues, such as appointment waiting time, unresolved.

9.4. Rural Access and Community Based Care

Through the Philippine National Rural Physician Deployment Program and Special Health Fund, the Philippines has piloted rural healthcare models that offer targeted support for remote areas [

93]. Additionally, Cuba’s Rural Medical Service has supplied a more reliable healthcare workforce for remote areas [

1]. Puerto Rico could implement rural incentive programs mimicking the Philippines and Cuba that would address rural provider shortages by providing incentives for healthcare workers and subsidizing population and individual health services.

Preventative healthcare strategies in the Philippines include telemedicine, preventative lifestyle medicine, and community health promotion [

67]. Puerto Rico could adopt similar programs, particularly regarding nutrition and chronic disease management, to reduce hospital overload and better serve its elderly population. Telehealth with providers throughout the continental United States could address accessibility and systemic load issues. Adopting South Korea’s advancements in AI-assisted healthcare and telemedicine could serve as a blueprint for Puerto Rico to improve service delivery, which could help overcome workforce limitations [

98].

Cuba’s Family Physician and Nurse Program embeds providers and nurses directly into communities, to expand primary care for its populations [

1]. A similar model applied to Puerto Rico to define geographic zones could aid in providing care for rural and elderly-dense regions. In these areas, promoting community-based elder care can draw inspiration from Japan’s Health and Medical Services Act. Puerto Rico could leverage its cultural emphasis on family by offering caregiver support stipends, tax credits, and caregiver training programs to support home-based elder care.

10. Discussion and Conclusions

Puerto Rico’s healthcare system is experiencing a healthcare crisis as a result of demographic decline, economic hardship, and structural deficiencies [

99]. Nearly one-quarter of the island’s population is now aged 65 or older—placing it among the highest globally—while a record-low fertility rate of 0.9 and emigration of younger individuals and healthcare professionals have deepened the strain [

40,

43]. These shifts have resulted in growing pressure on already overstretched healthcare services. To explore potential solutions, this study examines case studies from Cuba, Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea. Despite vastly different political and economic systems, each of these countries faces challenges akin to Puerto Rico’s: aging populations, workforce shortages, and inequities in healthcare delivery. Their policies—ranging from long-term care insurance to community-embedded provider models—offer insight into scalable, context-sensitive reforms.

Cuba’s model of community-based, preventive care demonstrates how localized service delivery can ease hospital overcrowding and extend care to underserved populations. The country’s investment in medical education and rural service commitments has helped sustain its healthcare workforce—an approach that contrasts with Puerto Rico’s ongoing loss of 365 to 500 doctors per year [

49]. With similar demographic pressures, Japan launched long-term care reforms through its “Gold Plan,” which expanded chronic care capacity, caregiver support programs, and introduced foreign labor integration strategies [

5]. While not without implementation challenges, these efforts illustrate the benefits of sustained policy attention to elder care and workforce resilience.

The Philippines has responded to labor losses by establishing bilateral labor agreements, rural fellowship initiatives, and a Universal Health Care framework emphasizing prevention and telemedicine [

10]. Although Puerto Rico cannot regulate migration in the same way, it could adopt similar tools to retain health workers and expand rural access. With a fertility rate even lower than Puerto Rico’s, South Korea has implemented long-term care insurance, embraced telemedicine, and relied on migrant labor to fill workforce gaps. However, the unequal treatment and instability faced by foreign workers highlights the importance of improving these strategies with inclusion efforts.

From these international examples, four key strategies emerge for Puerto Rico: reinvest in community-focused care; pursue workforce retention through incentives like debt relief and caregiver tax credits; expand telemedicine to reach underserved areas; and push for Medicaid funding equality. Incorporating flexible work hours, mental health support, and retirement-age extensions—as seen in Japan and South Korea—may also support provider longevity. Puerto Rico’s healthcare challenges mirror a broader global pattern, but by adapting proven solutions to its unique context, the island can begin moving toward a more sustainable and equitable system for its aging and vulnerable populations.

Funding

This manuscript was not commissioned and did not receive any funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Perreira K, Peters R, Lallemand N, et al. Puerto Rico health care infrastructure assessment. Urban Institute. 2017. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/87011/2001050-puerto-rico-health-care-infratructure-assessment-site-visit-report_1.pdf.

- Keck CW, Reed GA. The curious case of Cuba. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(8):e13–e22. [CrossRef]

- Blue SA. Cuban Medical Internationalism: Domestic and International Impacts. Journal of Latin American Geography. 2010;9(1):31–49. [CrossRef]

- Lamrani S. The health system in Cuba: Origin, doctrine and results. Études caribéennes. 2021;(7). [CrossRef]

- Dramé A. Insights from Cuba’s public health achievements: Implications for African countries. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology. 2024;16(2):41–50. [CrossRef]

- Nakatani H. Population aging in Japan: policy transformation, sustainable development goals, universal health coverage, and social determinates of health. Global Health & Medicine. 2019;1(1):3–10. [CrossRef]

- Katori T. Japan’s healthcare delivery system: From its historical evolution to the challenges of a super-aged society. Global Health & Medicine. 2024;6(1):6–12. [CrossRef]

- Tsugane S. Why has Japan become the world’s most long-lived country: insights from a food and nutrition perspective. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:921–928. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa N, et al. Japan’s super-aged society: Policies to support older healthcare workers. The Lancet Healthy Longevity. 2021;2(6):e340–e348. [CrossRef]

- Dayrit MM, et al. The Philippines health system review. World Health Organization. 2018. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274579.

- Co PA, Vîlcu I, De Guzman D, Banzon E. Staying the Course: Reflections on the Progress and Challenges of the UHC Law in the Philippines. Health Syst Reform. 2024;10(3):2397829. [CrossRef]

- Palma MA, Fernan B, Solijon V. Lifestyle Medicine and Universal Health Care Intersection: History and Impact of the Philippines Initiative. Am J Lifestyle Med. Published online March 15, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: Lessons for universal health care coverage. Health Policy and Planning. 2009;24(1):63–71. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Kwon S. A decade of public long-term care insurance in South Korea: Policy lessons for aging countries. Health Policy. 2020;125(1). [CrossRef]

- Lee JC, Kim MH. Rural-urban disparities in South Korea’s LTCI system. International Journal of Health Services. 2020;50(3):314–327. [CrossRef]

- Boydell V, Mori R, Shahrook S, Gietel-Basten S. Low fertility and fertility policies in the Asia-Pacific region. Global Health & Medicine. 2023;5(5):271–277. [CrossRef]

- Gu D, Andreev K, Dupre ME. Major Trends in Population Growth Around the World. China CDC Weekly. 2021;3(28):604–613. [CrossRef]

- Visual Capitalist. Charted: The world’s aging population (1950 to 2100). Visual Capitalist. September 21, 2023. Available at: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/charted-the-worlds-aging-population-1950-to-2100/.

- Bloom DE, Canning D, Lubet A. Global population aging: Facts, challenges, solutions & perspectives. Daedalus. 2015;144(2):80–92. [CrossRef]

- Ansah JP, Chiu CT. Projecting the chronic disease burden among the adult population in the United States using a multi-state population model. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;10:1082183. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and health. Fact sheet. 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- Jones CH, Dolsten M. Healthcare on the brink: Navigating the challenges of an aging society in the United States. Aging. 2024;10:Article 22. [CrossRef]

- Kallestrup-Lamb M, Marin AO, Menon S, Søgaard J. Aging populations and expenditure on health. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing. 2024;100518.

- Amiri MM, Kazemian M, Motaghed Z, Abdi Z. Systematic review of factors determining health care expenditures. Health Policy and Technology. 2021;10(2):100498. [CrossRef]

- Iijima K, Arai H, Akishita M, et al. Toward the development of a vibrant, super-aged society: The future of medicine and society in Japan. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2021;21(8):601-61. [CrossRef]

- McSorley AMM, Rivera-González AC, Mercado DL, Pagán JA, Purtle J, Ortega AN. United States federal policies contributing to health and health care inequities in Puerto Rico. American Journal of Public Health. 2024;114(S6):S478–S484. [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Members and partners. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/members-partners.html.

- World Health Organization. Health workforce migration. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/health-workforce/migration.

- Toyin-Thomas P, Ikhurionan P, Omoyibo E, et al. The impact of physician migration on healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health. 2023;8(5):e012338. Available at: https://gh.bmj.com/content/bmjgh/8/5/e012338.full.pdf.

- Kobewka DM, Kunkel E, Hsu A, et al. Physician availability in long-term care and resident hospital transfer: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020;21(4):469–475. [CrossRef]

- Yee CA, Barr K, Minegishi T, et al. Provider supply and access to primary care. Health Economics. 2022;31(7):1296–1316. [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health. National medical workforce strategy 2021-2031. 2022. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/03/national-medical-workforce-strategy-2021-2031.pdf.

- Kang M, Choi YJ, Kim Y, et al. Sustainability and resilience in the Republic of Korea health system. Partnership for Health System Sustainability and Resilience. 2024. Available at: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_PHSSR_CAPRI_Korea_2024.pdf.

- Sundararaman T, Gupta G. Indian approaches to retaining skilled health workers in rural areas. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;89(1):73–77. [CrossRef]

- Labonté R, Sanders D, Mathole T, et al. Health worker migration from South Africa: Causes, consequences and policy responses. Human Resources for Health. 2015;13:1. [CrossRef]

- Flores EL, Manahan EM, Lacanilao MP, et al. Factors affecting retention in the Philippine National Rural Physician Deployment Program from 2012 to 2019: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21(1). [CrossRef]

- Hartigan-Go KY, Prieto MLM, Valenzuela SA. Important but Neglected: A Qualitative Study on the Lived Experiences of Barangay Health Workers in the Philippines. Acta Med Philipp. 2025;59(9):19-31. Published 2025 Jul 15. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-González AC, Roby DH, Stimpson JP, et al. The impact of Medicaid funding structures on inequities in health care access for Latinos in New York, Florida, and Puerto Rico. Health Services Research. 2022;57:172-182. [CrossRef]

- Departamento de Salud. Programa Medicaid. Programa Medicaid – Departamento de Salud. Available at: https://www.medicaid.pr.gov/(X(1)S(zu4odn3az5ghj4chnjyytf1u))/Info/Statistics/?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1.

- U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: Puerto Rico. 2024. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/PR/AGE775223#AGE775223.

- Matos-Moreno A, Verdery AM, Mendes de Leon CF, De Jesús-Monge VM, Santos-Lozada AR. Aging and the Left Behind: Puerto Rico and Its Unconventional Rapid Aging. The Gerontologist. 2022;62(7):964–973. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate) - United States, Puerto Rico. 2023. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?locations=US-PR.

- World Bank Group. Fertility rate, total (births per woman) - Puerto Rico. 2022. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=PR.

- Rosario-Santos AM, Pericchi-Guerra L, Mattei H. A Bayesian Projection of the Total Fertility Rate of Puerto Rico: 2020-2050. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal. 2024;43(3):125–131.

- Population Reference Bureau. 2024 World Population Data Sheet. 2024;10.

- Pérez C, Ailshire JA. Aging in Puerto Rico: A Comparison of Health Status Among Island Puerto Rican and Mainland U.S. Older Adults. Journal of Aging and Health. 2017;29(6):1056–1078. [CrossRef]

- Matos-Moreno A, Santos-Lozada AR, Mehta N, et al. Migration is the driving force of rapid aging in Puerto Rico: A Research Brief. Population Research and Policy Review. 2022;41(3):801–810. [CrossRef]

- El Instituto de Estadísticas de Puerto Rico. Perfil del Migrante 2021-2022. 2022. Available at: https://estadisticas.pr/files/Publicaciones/PM_2021-2022.pdf.

- Santiago-Santiago AJ, Rivera-Custodio J, Mercado Rios CA, et al. Puerto Rican physician’s recommendations to mitigate medical migration from Puerto Rico to the mainland United States. Health Policy OPEN. 2024;7:100124. [CrossRef]

- Varas-Díaz N, Rodríguez-Madera S, Padilla M, et al. On leaving: Coloniality and physician migration in Puerto Rico. Social Science & Medicine. 2023;325:115888. [CrossRef]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Updated Costliest U.S. Tropical Cyclones Tables. National Hurricane Center. Published January 27, 2018. Accessed November 10, 2025. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20180127083930/https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/news/UpdatedCostliest.pdf.

- Kishore N, Marqués D, Mahmud A, et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(2):162-170. [CrossRef]

- U.S Department of Energy. Puerto Rico grid recovery and modernization. Energy.Gov. 2023. Available at: https://www.energy.gov/gdo/puerto-rico-grid-recovery-and-modernization.

- Rodríguez-Madera SL, Varas-Díaz N, Padilla M, et al. The impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico’s health system: post-disaster perceptions and experiences of health care providers and administrators. Global Health Research and Policy. 2021;6(44):44. [CrossRef]

- Mola E, Acevedo B, Silva R, et al. Development of Cuban biotechnology. Journal of Commercial Biotechnology. 2003;9(2):147–152. [CrossRef]

- CEIC Data. Cuba: Physicians per 1000 people. CEIC Data. 2021. Available at: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/cuba/social-health-statistics/cu-physicians-per-1000-people.

- Dyer O. Cuba pulls more than 8000 doctors out of Brazil after qualifications are questioned. BMJ. 2018;363:4860.

- Bayarre Vea HD, Álvarez Lauzarique ME, Pérez Piñero JS, et al. Demographic aging in Cuba: Perspectives, evolution and approaches. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2018;42:e21. [CrossRef]

- Bertera E. Social Services for the Aged in Cuba. International Social Work. 2003;46(3):313–321. [CrossRef]

- Hara K, Kuroki M, Shiraishi S, et al. Evaluation of planned number of children, the well-being of the couple and associated factors in a prospective cohort in Yokohama (HAMA study): study protocol. BMJ Open. 2024;14(2):e076557. [CrossRef]

- Mitsutake S, Ishizaki T, Teramoto C, Shimizu S, Ito H. Patterns of Co-Occurrence of Chronic Disease Among Older Adults in Tokyo, Japan. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2019;16:E11. [CrossRef]

- Parsons AJQ, Gilmour S. An evaluation of fertility- and migration-based policy responses to Japan’s ageing population. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209285. [CrossRef]

- Taira K, Horikawa M, Itaya T, et al. Estimation of supply and demand for public health nurses in Japan: A stock-flow approach. PLoS One. 2025;20(2):e0313110. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama I, Tokuda Y. Changing work styles among Japanese healthcare professionals. Journal of General and Family Medicine. 2017;18(4):152. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) - Puerto Rico. World Bank Open Data. 2024. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO.ZS?end=2023&locations=PR-IT-FI-PT&most_recent_value_desc=true&start=1960&view=chart.

- Brodit CJ, Norona MI. Developing a Susceptibility Index for Elderly Care Management in the Philippines: A Systems Perspective. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management. 2021.

- Alibudbud R. Telemedicine in the Philippines: Opportunities and challenges during COVID-19. Journal of Public Health. 2022;44(3):e476–e478. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Health Labor Market Analysis of the Philippines: Final Report. HRH2030 Program; 2020. Available at: https://hrh2030program.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/1.1_HRH2030PH_HLMA-Report.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Bilateral agreements on health worker migration and mobility: Maximizing health system benefits and safeguarding health workforce rights and welfare through fair and ethical international recruitment. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2024. ISBN: 978-92-4-007305-0.

- Leyva EWA, Soberano JID, Paguio JT, et al. Pandemic Impact, Support Received, and Policies for Health Worker Retention: An Environmental Scan. Acta Med Philipp. 2024;58(12):8–20. Published 2024 Jul 15. [CrossRef]

- Department of Health (Philippines), Department of Budget and Management, Department of Finance, Department of the Interior and Local Government, Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth). Joint Memorandum Circular No 2021-0001: Guidelines on the allocation, utilization, monitoring of and accountability for the Special Health Fund under Republic Act No 11223 (Universal Health Care Act). Manila: Government of the Philippines; 13 Jan 2021.

- Panganiban JMS, Camiling-Alfonso R, Sanchez JT, et al. Impact of primary care benefits on healthcare utilisation and estimated out-of-pocket expenses in urban, rural and remote settings in the Philippines. BMJ Open Qual. 2025;14(1):e002676. Published 2025 Jan 22. [CrossRef]

- Giri B, Singh DB, Chattu VK. Aging population in South Korea: burden or opportunity? International Journal of Surgery: Global Health. 2024;7(6). [CrossRef]

- Cho HJ, Kang K, Park KY. Health and medical experience of migrant workers: qualitative meta-synthesis. Archives of Public Health. 2024;82(1). [CrossRef]

- National Library of Korea. History and Future of National Health Insurance. 2019. Available at: https://www.nl.go.kr/EN/contents/EN34501000000.do.

- Park S, Kim MS, Yon DK, et al. Population health outcomes in South Korea 1990–2019, and projections up to 2040: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(8):e639–e650. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy and Finance, World Bank. How Korea’s National Health Insurance (NHI) Responded to The COVID-19 Pandemic. September 2023. Available at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/3ce40f2a48e4df8c6bfe6fca21f37397-0070012023/original/PN2-NHI-Policy.pdf.

- Kwon HJ, Oh H, Kong JW. The Institutional Factors Affecting the Growth of Korean Migrant Care Market and Sustainability in Long-Term Care Quality. Sustainability. 2022;14(6):3366. [CrossRef]

- Ga H. Long-Term Care System in Korea. Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research. 2020;24(3):181–186. [CrossRef]

- Park MS, Jo H, Lee H, et al. Machine Learning-Based COVID-19 Patients Triage Algorithm Using Patient-Generated Health Data from Nationwide Multicenter Database. Infectious Diseases and Therapy. 2022;11(2):787–805. [CrossRef]

- Lee SW, Jung H, Ko S, et al. CareCall: a Call-Based Active Monitoring Dialog Agent for Managing COVID-19 Pandemic. ArXiv.org. 2020. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.02642.

- Lee HC. Population Aging and Korean Society. Korea Journal. 2021;61(2):5–20. [CrossRef]

- Human Resources Development Service of Korea. Available at: https://www.hrdkorea.or.kr/ENG/4/2.

- Kim AE. Global migration and South Korea: foreign workers, foreign brides and the making of a multicultural society. In: Migration: Policies, Practices, Activism; Routledge. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315878119-5/global-migration-south-korea-foreign-workers-foreign-brides-making-multicultural-society-andrew-eungi-kim.

- OECD. Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Korea 2019. OECD. 2019. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/recruiting-immigrant-workers-korea-2019_9789264307872-en.html.

- Kim M. Shaping the Future Amid Decline: Integrative Strategies for Aging Koreans and Migrant Workers in South Korea’s Shrinking Regions. MIT. 2024. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/156158.

- Amnesty International. South Korea: “Migrant workers are also human beings.” August 16, 2006. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa25/007/2006/en/.

- Abalos JB. The state of elderly care in the Philippines: A scoping review. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 2020;6:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Japan’s universal long-term care system reform of 2005: Containing costs and realizing a vision. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(12):2188–2193. [CrossRef]

- Tamiya N, et al. Population ageing and wellbeing: Lessons from Japan’s long-term care insurance policy. The Lancet. 2011;378(9797):1183–1192. [CrossRef]

- Shimizutani S. Can Japan’s elderly employment policies fix labor shortages? Journal of the Japanese and International Economies. 2022;63:101192. [CrossRef]

- Kim HK, Lee SH. The Effects of Population Aging on South Korea’s Economy: The National Transfer Accounts Approach. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing. 2021;20:100340. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo FME, et al. Nurse migration from a source country perspective: Philippine country case study. Health Services Research. 2007;42(3p2):1406–1418. [CrossRef]

- Rivera FI. Puerto Ricans in Florida: Migration, Identity, and Incorporation. In: Meléndez E, Vargas-Ramos C, eds. Puerto Ricans at the Dawn of the New Millennium. New York, NY: Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College (CUNY); 2017.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Puerto Rico: Fiscal and economic trends (GAO-22-104341). 2022. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-104341.

- Caraballo-Cueto J. The mirage of development: Tax incentives in Puerto Rico. Latin American Perspectives. 2021;48(4):123–139. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, et al. Long-term care insurance in South Korea: Policy effects and future challenges. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2021;33(4–5):484–501. [CrossRef]

- Kim HS, et al. Artificial intelligence in Korean health care: Current applications and lessons for global implementation. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2021;4(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Frontera-Escudero I, Bartolomei JA, Rodríguez-Putnam A, Claudio L. Sociodemographic and health risk factors associated with health-related quality of life among adults living in Puerto Rico in 2019: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):2150. Published 2023 Nov 3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).