1. Introduction

The global population is aging rapidly, with the median age steadily increasing and a growing proportion of individuals over 65 years. This demographic shift has profound implications for healthcare systems, as circulatory diseases remain the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for a substantial proportion of overall mortality [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In this context, the management of acute events such as in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) in an increasingly frail and elderly population has become a primary clinical challenge. IHCA represents a major clinical challenge, associated with high morbidity and mortality. Its incidence ranges from 1 to 3 events per 1000 hospital admissions [

5], while survival rates at hospital discharge typically range between 15% and 34% [

2], declining further at 30 days post-event, highlighting the complexity of managing these critically ill patients [

6,

7]. Given that cardiac arrests are often preceded by rapid clinical deterioration, prompt and accurate identification of patients at risk has become crucial for improving outcomes and survival. Early warning systems have been developed extensively in recent decades, with particular emphasis placed on standardized early warning scores aimed at identifying patient deterioration [

8,

9]. Among them, the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2), recommended by the Royal College of Physicians, is one of the most widely adopted [

10,

11]. Despite extensive validation in numerous clinical settings, the predictive accuracy and clinical effectiveness of this score in preventing IHCA remain debated particularly regarding its sensitivity and specificity, particularly in vulnerable subgroups of hospitalized patients, such as elderly individuals with multiple comorbidities and clinical frailty [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Frailty itself, a condition characterized by reduced physiological reserve, impaired functional capacity, and increased vulnerability to adverse events, further complicates clinical management. Reduced compensatory mechanisms contribute to a higher risk of poor responses to acute medical events, including cardiac arrest [

16,

17]. Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) and Barthel Index (BI) provide available tools for assessing frailty [

18,

19]. A higher CFS and a lower BI therefore indicate greater vulnerability to adverse outcomes, including poor recovery following IHCA [

20,

21]. This approach provides a quantitative measure that can be integrated into clinical decision-making and risk stratification. Emerging evidence suggests that personalized approaches, specifically adjusting thresholds and response criteria based on individual frailty assessments, may substantially enhance the performance of EWS, potentially leading to more effective interventions, improved clinical outcomes, and optimized utilization of healthcare resources [

22,

23].

This study described the relationship between NEWS2 and frailty scores in elderly IHCA patients, with the hypothesis that low NEWS2 scores could be associated with high frailty burden, that could precipitate in IHCA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This monocentric, observational, retrospective study was performed in the Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit of the University Hospital of Siena, Italy, between January 2022 and January 2024. The study was designed and reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [

24].

2.2. Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Local Ethical Committee (CE Area Toscana Sudest, Protocol ID 29280).

2.2. Study Population and Data Collection

All adult patients (≥18 years) admitted to general medical or surgical wards who experienced an in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) with subsequent activation of the Rapid Response System (RRS) / Medical Emergency Team (MET) during the study period were eligible for inclusion. Patients younger than 18 years at the time of the event were excluded.

Data were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records and RRS/MET activation forms. We collected data on demographics, pre-existing chronic diseases, CCI, CFS, BI and the last NEWS2 score available in the medical records preceding the cardiac arrest. Mortality data and hospital length of stay was also recorded.

2.3. Score Calculation

This study evaluated the last available NEWS2 score recorded in the electronic medical records of all adult patients (≥18 years old) admitted to general medical or surgical wards who experienced an IHCA with subsequent activation of the RRS/ MET between January 2022 and January 2024.

NEWS2 is a clinical assessment tool based on six physiological variables: respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, and level of consciousness (including new-onset confusion). Each variable is assigned a score ranging from 0 to 3, with an additional 2 points allocated to patients receiving supplemental oxygen. The tool was designed to improve the early recognition of clinical deterioration in acutely ill patients, with scores of 5–6 or higher serving as a threshold for urgent clinical intervention. According to the NEWS2 classification, patients were initially stratified into four categories (Stable, Potentially Unstable, Unstable, and Critical) [

11,

25]. Depending on severity, interventions may include the activation of the attending ward physician or the RRS/MET (

Table 1) [

26].

Considering that the Potentially Unstable and Unstable categories were not discriminatory for emergency team activation (RRS/MET) in our patient population, and given that both levels require urgent medical evaluation, these two categories were merged into a single group. Thus, we obtained three categories: Stable patients (NEWS2-A), Potentially Unstable + Unstable patients (NEWS2-B), and Critical patients (NEWS2-C). This aggregation reduced subgroup fragmentation while preserving the clinical interpretability of the analysis.

In parallel with NEWS2, the CFS was employed to characterize patients’ baseline functional reserve and frailty status. This nine-point scale evaluates functional status based on independence in activities of daily living and overall health condition during the two weeks preceding the onset of acute illness. Scores of 1–3 correspond to individuals who are classified as very fit, fit, or managing well, whereas a score of 4 reflects very mild frailty. Values ranging from 5 to 8 indicate increasing severity of frailty (mild, moderate, severe, and very severe), typically associated with a need for assistance in everyday activities. A score of 9 is reserved for terminally ill patients. The scale is straightforward to administer, requires minimal time, and is therefore suitable for use in acute care settings [

27,

28,

29].

Complementary to frailty assessment, functional independence was evaluated using the BI. This ordinal scale measures the ability to perform ten basic activities of daily living, including feeding, bathing, grooming, dressing, bowel and bladder control, toilet use, transfers, mobility, and stair climbing. Scores range from 0 to 100, with lower values indicating greater functional impairment and dependence, and higher values reflecting greater independence. The BI is widely validated, easy to apply in both clinical and research settings, and provides valuable insights into patients’ baseline autonomy and recovery potential. The BI was administered by nursing staff at the time of ward admission, drawing on both medical history and the patient’s observable clinical status on admission to derive the final score.

Additionally, to better account for the impact of chronic health conditions on outcomes, a comorbidity burden assessment was performed using a validated comorbidity index (such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index, CCI). The CCI assigns weighted scores to a range of chronic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, malignancies), producing a cumulative score that reflects the overall comorbidity severity and correlates with mortality risk (

Table 4) [

15,

30]. This index was calculated for each patient using diagnostic information available in the electronic medical records prior to the IHCA event, allowing for its inclusion in subsequent analyses as an independent variable. Patients younger than 18 years at the time of the event were excluded.

2.4. Study Outcomes

The primary endpoint of this study was to evaluate whether combining the NEWS2 score with frailty indices (BI, CCI, and CFS) could enhance the characterization of frail patients at risk of IHCA.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Binary variables were expressed as counts (percentage) and continuous variables as means ± standard deviation or medians with interquartile range (25th to 75th percentiles), depending on the normality of distribution. The Shapiro-Wilk, histograms, and normal-quantile plots were used to verify the normality of distribution of continuous variables. Associations between continuous variables and NEWS2 severity categories were assessed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. When significant, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed with the Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner method. For categorical variables (e.g. age groups, comorbidities), contingency tables and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used as appropriate. Data were analyzed using software Jamovi (version 2.6.26). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

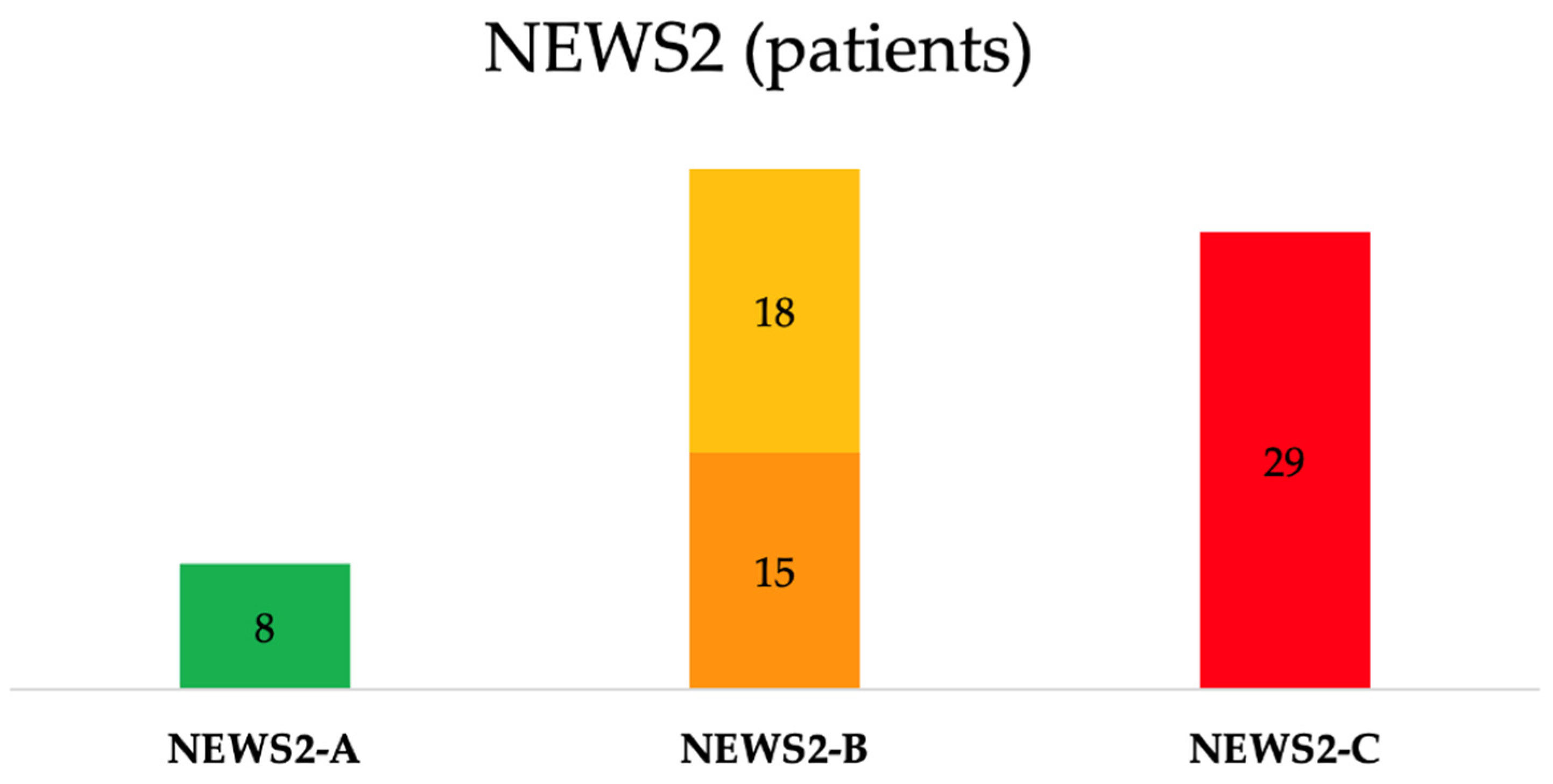

A total of 75 patients who experienced IHCA with RRS/MET activation were identified. Three of them lacked data on BI, CCI, and CFS, and two of them had missing outcome information. As such, the final cohort included 70 IHCA subjects (mean age of 76.9 ± 11.0 years and 56% were male). The majority (N=50, 71%) of patients were admitted to medical wards; 20 (29%) of them were in surgical wards. Based on the last NEWS2 recorded before the IHCA, the mean NEWS2 score before IHCA in the overall population was 6.0 ± 3.5, distributed as follows: 1.8 ± 1.3 in the Stable group (n=8, 11%), 3.2 ± 1.2 in the Potentially Unstable (n=18, 26%), 5.1 ± 1.3 in the Unstable (n=15, 22%) and 9.4 ± 2.4 in the Critical group (n=29, 41%) (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

Following the reclassification applied in the study, 41% of patients (N=29) were included in the NEWS2-C group, 48% (N=33) in the NEWS2-B group and 11% (N=8) in the NEWS2-A group (

Table 3,

Figure 1).

BI values showed marked variation across NEWS2 categories: NEWS2-A patients had substantially higher scores (64.4 ± 35.5) compared with NEWS2-B (24.7 ± 32.7) and NEWS2-C (11.5 ± 26.4; p<0.01) patients; in particular, NEWS2-A subgroup has significantly higher BI values than two others. On the opposite, CFS increased among NEWS2 groups significantly increased from 4.3 ± 1.8 in the NEWS2-A group to 6.14 ± 1.75 in the NEWS2-C (p<0.01), with similar results than BI for subgroup comparisons. CCI was 6.5 ± 2.7 in the overall population, non-significantly ranging from 5.4 ± 3.1 in the NEWS2-A group to 7.1 ± 3.2 in the NEWS2-C group (p=0.43). Also, age was not significantly different among subgroups (

Table 4).

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of patients according to NEWS2 A-B-C.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of patients according to NEWS2 A-B-C.

| Variable |

NEWS2-A (n=8) |

NEWS2-B (n=33) |

NEWS2-C (n=29) |

p-value |

| CCI |

5.4 ± 3.1 |

6.2 ± 2.0 |

7.1 ± 3.2 |

0.43 |

| BI |

64.4 ± 35.5 |

24.7 ± 32.7 |

11.6 ± 26.4 |

0.01 |

| CFS |

4.3 ± 1.8 |

6.1 ± 1.4 |

6.1 ± 1.8 |

0.01 |

| Age (years) |

70.6 ± 12.4 |

76.7 ± 9.2 |

79.0 ± 12.2 |

0.10 |

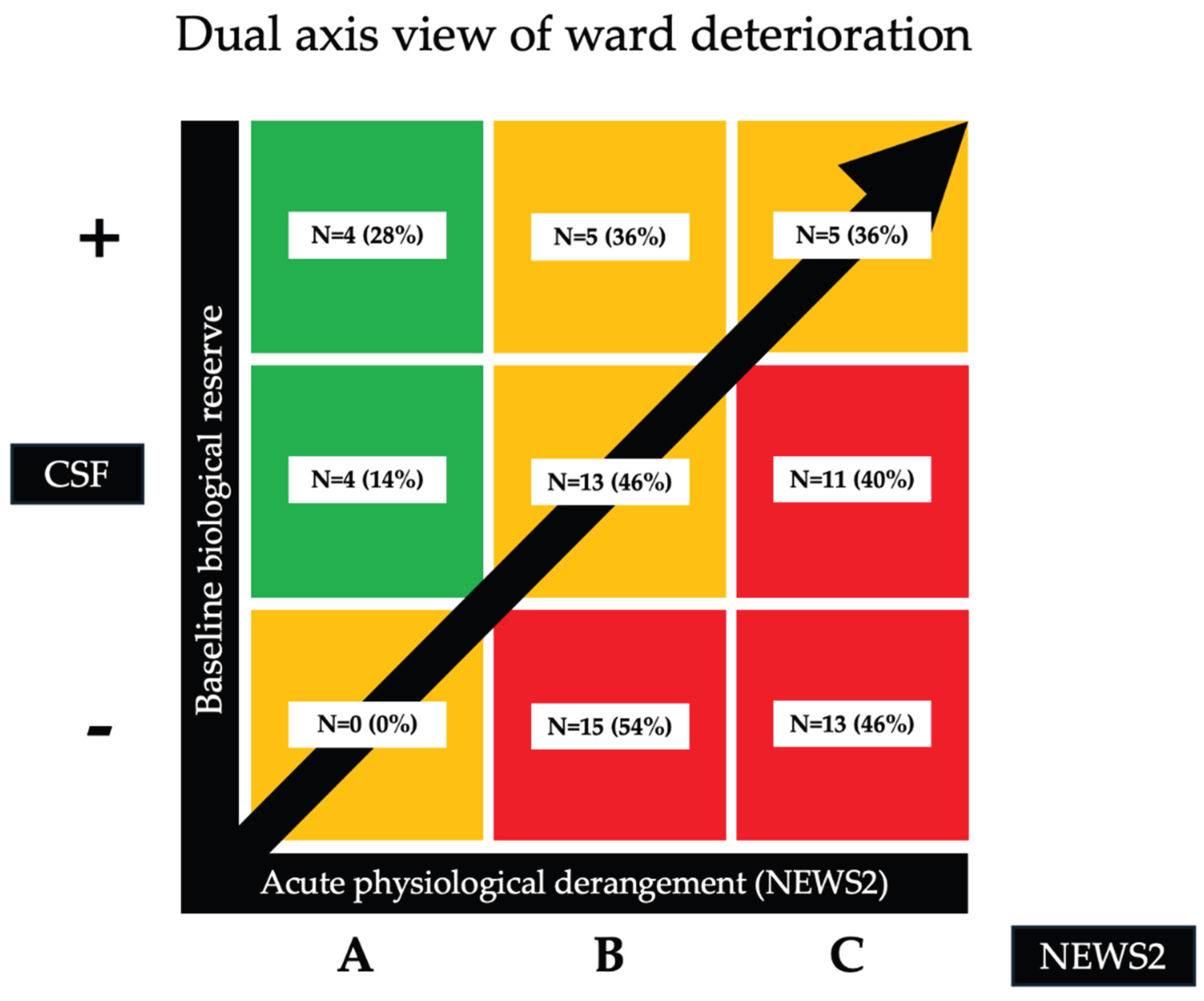

The distribution of NEWS2 subgroups (i.e. acute physiological derangement) in relation with CFS and BI (i.e. baseline reserve) is represented using a two-axis diagram in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined a cohort of 70 hospitalized patients who experienced IHCA, with the aim of assessing whether the combination of the NEWS2 score with frailty indices such as the BI, CCI, and CFS could enhance the characterization of the pre-arrest condition of elderly IHCA patients. To date, few studies have reported specifically on the performance of NEWS2 scores in frail elderly patients for identifying subjects who would potentially face IHCA [

28,

30,

31,

32]. Patients in our cohort were heterogeneously distributed across NEWS2 strata prior to arrest (Stable, Potentially Unstable, Unstable, and Critical) suggesting that reliance on physiological scores alone may delay RRS activation and hinder early interception of the patients who experience IHCA. Although the most fragile patients tended to cluster in the Critical group, others who experienced IHCA were classified as Stable or Potentially Unstable/Unstable, suggesting that NEWS2 alone underestimate the risk. Because the Potentially Unstable and Unstable tiers were heterogeneous and operationally non-discriminatory for emergency activation in our setting, we merged them into a single group (NEWS2-B), yielding three bands for analysis: Stable (NEWS2-A), Potentially Unstable + Unstable (NEWS2-B), and Critical (NEWS2-C) [

33]. This approach reduced subgroup fragmentation and emphasized the need to integrate frailty and functional indices to capture vulnerability, not reflected by vital signs alone. Our data showed differences in functional status and frailty across NEWS2-A/B/C, whereas age and CCI showed limited additional information. This pattern aligns with an expanding literature in which frailty and function outperform comorbidity combined with NEWS2 improves the characterization of such patients versus NEWS2 alone [

34,

35]. However, the limited sample size (70 patients, all with IHCA) may have reduced the ability to detect a true discriminative effect of CCI.

Our findings also suggested that CFS and BI were significantly different across NEWS2 categories, reflecting susceptibility to acute clinical condition in the 24 hours prior to arrest. In practice, integrating CFS and BI with NEWS2 may facilitate earlier interception of at-risk patients and prompt timely RRS evaluation before IHCA occurs. In particular, patients with a high frailty burden but only modest physiological derangements may have reduced tolerance to acute stressors, predisposing them to clinical deterioration and cardiac arrest. Compared with other older patients experiencing similar acute abnormalities but lower frailty, these individuals may be at higher risk despite relatively preserved vital signs. This vulnerability should alert RRS/MET to the need for heightened surveillance, as reliance on standard vital parameters alone may fail to identify their increased risk of cardiac arrest. However, our study cannot establish a specific cutoff value for any single score, nor validate any score combination to predict IHCA. Instead, these measures may act as early alerts prompting RRS assessment, enabling experienced clinicians to recognize patients whose condition is worsening. A prospective model developed by Lo Conte et al. on a large cohort of patients, using logistic regression analysis, showed that integration of the BI with NEWS2 improved the detection of high-risk patients and outperformed NEWS2 alone in predicting both deterioration and in-hospital mortality [

36]. Instead, Chung et al., in a multicenter retrospective study, reported that adding the CFS to NEWS2 significantly improved 30-day mortality prediction in older emergency department patients. Also, Wretborn et al. demonstrated that combining CFS with vital-sign–based early warning systems yielded superior risk stratification for short- and long-term mortality compared to physiology alone [

34,

37]. However, in that study the CCI showed no significant association with NEWS2, suggesting that the cumulative impact of chronic comorbidities alone may not adequately capture short-term vulnerability in the context of acute deterioration. Finally, in a study including 478 COVID-19 patients it was found that although both NEWS2 and CCI were associated with mortality, the incremental value of CCI was limited, particularly in older populations with a uniformly high comorbidity burden [

38]. From a clinical perspective, these findings support a dual-axis view of ward deterioration: acute physiological derangement (NEWS2) and baseline biological reserve (as captured by frailty and functional status). Embedding frailty measures such as CFS and BI into escalation algorithms, particularly when NEWS2 is intermediate (NEWS2-B), could sharpen triage, reduce missed deterioration in the frail, and prevent unnecessary activations of RRS. Such integration might allow for earlier activation of the RRS/MET even at lower NEWS2 thresholds (e.g NEWS2-A), especially in patients whose clinical fragility is not fully captured by vital signs alone.

Our study has some strengths: it addresses an understudied but clinically relevant population (elderly hospitalized patients with IHCA), and integrates multiple dimensions of vulnerability (NEWS2, CFS, BI, CCI) demonstrating their differential association with acute deterioration. However, these strengths should be tempered by several limitations. The retrospective, single-centre design and relatively small sample size constrain the precision of estimates and limit generalizability. The absence of a control group, as only patients who experienced IHCA were included, prevents comparison with patients who did not arrest and thus precludes any estimation of real risk or incremental predictive value. In addition, the use of the last recorded NEWS2 introduces a timing bias, which may fail to capture the true peri-arrest physiological trajectory. Finally, because of the observational design, causal inferences cannot be drawn. Prospective, multicentre studies, ideally incorporating trend-based early-warning metrics and frailty-augmented escalation algorithms, are needed to validate these findings and to inform tailored intervention strategies. Future research should aim to develop and validate frailty-informed early warning models within RRS systems, integrating physiological, functional, and frailty data to improve early recognition and tailored escalation of care in older, vulnerable patients.

5. Conclusions

In this study, NEWS2 values demonstrated substantial variability among older patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest. Integrating NEWS2 with frailty assessment may improve the identification of elderly individuals with diminished physiological reserve and limited tolerance to acute deterioration, such as in-hospital cardiac arrest.

Author Contributions

CB and EM contributed equally to this study. CB and EM have given substantial contributions to the conception, writing of the manuscript. RG, AV and EM have given substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of the data. CB realized the tables and the figures. FF, FST, SS revised and supervised it critically. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

the study was approved by the Local Ethical Committee (CE Area Toscana Sudest, Protocol ID 29280).

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Eurostat EU Median Age Increased by 2.3 Years since 2013 2013.

- Gräsner, J.-T.; Wnent, J.; Herlitz, J.; Perkins, G.D.; Lefering, R.; Tjelmeland, I.; Koster, R.W.; Masterson, S.; Rossell-Ortiz, F.; Maurer, H.; et al. Survival after Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in Europe - Results of the EuReCa TWO Study. Resuscitation 2020, 148, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaldi, D.; Dumas, F.; Perier, M.-C.; Charpentier, J.; Varenne, O.; Zuber, B.; Vivien, B.; Pène, F.; Mira, J.-P.; Empana, J.-P.; et al. Short- and Long-Term Outcome in Elderly Patients After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Cohort Study*. Critical Care Medicine 2014, 42, 2350–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jane Osareme, Ogugua; Muridzo Muonde; Chinedu Paschal Maduka; Tolulope O Olorunsogo; Olufunke Omotayo Demographic Shifts and Healthcare: A Review of Aging Populations and Systemic Challenges. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 383–395. [CrossRef]

- Gräsner, J.-T.; Herlitz, J.; Tjelmeland, I.B.M.; Wnent, J.; Masterson, S.; Lilja, G.; Bein, B.; Böttiger, B.W.; Rosell-Ortiz, F.; Nolan, J.P.; et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Epidemiology of Cardiac Arrest in Europe. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.W.; Holmberg, M.J.; Berg, K.M.; Donnino, M.W.; Granfeldt, A. In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Review. JAMA 2019, 321, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.P.; Berg, R.A.; Andersen, L.W.; Bhanji, F.; Chan, P.S.; Donnino, M.W.; Lim, S.H.; Ma, M.H.-M.; Nadkarni, V.M.; Starks, M.A.; et al. Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Outcome Reports: Update of the Utstein Resuscitation Registry Template for In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation 2019, 144, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.; Lee, C.M.Y.; Begg, S.; Crombie, A.; Mnatzaganian, G. The Use of Early Warning System Scores in Prehospital and Emergency Department Settings to Predict Clinical Deterioration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. The National Early Warning Score: From Concept to NHS Implementation. Clinical Medicine 2022, 22, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spångfors, M.; Molt, M.; Samuelson, K. In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest and Preceding National Early Warning Score (NEWS): A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Clinical Medicine 2020, 20, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Physicians of London. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2 Standardising the Assessment of Acute-Illness Severity in the NHS.

- Gerry, S.; Birks, J.; Bonnici, T.; Watkinson, P.J.; Kirtley, S.; Collins, G.S. Early Warning Scores for Detecting Deterioration in Adult Hospital Patients: A Systematic Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e019268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.B.; Prytherch, D.R.; Schmidt, P.E.; Featherstone, P.I. Review and Performance Evaluation of Aggregate Weighted ‘Track and Trigger’ Systems. Resuscitation 2008, 77, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonem, S.; Draicchio, D.; Mohamed, A.; Wood, S.; Shiel, K.; Briggs, S.; McKeever, T.M.; Shaw, D. Physiological Deterioration Prior to In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: What Does the National Early Warning Score-2 Miss? Resuscitation Plus 2024, 20, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.B.; Prytherch, D.R.; Jarvis, S.; Kovacs, C.; Meredith, P.; Schmidt, P.E.; Briggs, J. A Comparison of the Ability of the Physiologic Components of Medical Emergency Team Criteria and the U.K. National Early Warning Score to Discriminate Patients at Risk of a Range of Adverse Clinical Outcomes*. Critical Care Medicine 2016, 44, 2171–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.; Iliffe, S.; Rikkert, M.O.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in Elderly People. The Lancet 2013, 381, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K. A Global Clinical Measure of Fitness and Frailty in Elderly People. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, S.; Rogers, E.; Rockwood, K.; Theou, O. A Scoping Review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr 2020, 20, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuguchi, T.; Nakajima, K.; Takaoka, H.; Shimokawa, T. Usefulness of Clinical Frailty Scale for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment of Older Heart Failure Patients. Circ Rep 2024, 6, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.Y.; Streiter, S.; O’Mara, L.; Sison, S.M.; Theou, O.; Bernacki, R.; Orkaby, A. Frailty and Survival After In-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. J GEN INTERN MED 2022, 37, 3554–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, F.I.; Turcotte, L.; Strum, R.P.; De Wit, K.; Griffith, L.E.; Worster, A.; Foroutan, F.; Heckman, G.; Hebert, P.; Schumacher, C.; et al. Prognostic Association Between Frailty and Post-Arrest Health Outcomes in Patients Receiving Home Care: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Resuscitation 2023, 187, 109766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ortuno, R.; Wallis, S.; Biram, R.; Keevil, V. Clinical Frailty Adds to Acute Illness Severity in Predicting Mortality in Hospitalized Older Adults: An Observational Study. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2016, 35, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.; Hull, L.; Conroy, S.P. Frailty Identification in the Emergency Department—a Systematic Review Focussing on Feasibility. Age and Ageing 2017, 46, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevon, P.; Shamsi, S. Using National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2 to Help Manage Medical Emergencies in the Dental Practice. Br Dent J 2020, 229, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regione Toscana Linee di indirizzo regionali per la gestione delle emergenze intraospedaliere 2019.

- Roa Santervas, L.; Wyller, T.B.; Skovlund, E.; Kristoffersen, E.S.; Romskaug, R. Associations Between Frailty, Illness Severity, and Long-Term Mortality Among Older Adults Admitted to Municipal Acute Care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2025, 26, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rønningen, P.S.; Walle-Hansen, M.M.; Ihle-Hansen, H.; Andersen, E.L.; Tveit, A.; Myrstad, M. Impact of Frailty on the Performance of the National Early Warning Score 2 to Predict Poor Outcome in Patients Hospitalised Due to COVID-19. BMC Geriatr 2023, 23, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in Older Adults. N Engl J Med 2024, 391, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorén, A.; Joelsson-Alm, E.; Spångfors, M.; Rawshani, A.; Kahan, T.; Engdahl, J.; Jonsson, M.; Djärv, T. The Predictive Power of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2, as Compared to NEWS, among Patients Assessed by a Rapid Response Team: A Prospective Multi-Centre Trial. Resuscitation Plus 2022, 9, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, K.; Alakare, J.; Harjola, V.-P.; Strandberg, T.; Tolonen, J.; Lehtonen, L.; Castrén, M. National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) and 3-Level Triage Scale as Risk Predictors in Frail Older Adults in the Emergency Department. BMC Emerg Med 2020, 20, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeyens, H.; Haegdorens, F.; Martens, S.; Abeele, M.E.V.; Wallaert, S.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Brys, A.D.H. Validation and Performance of a Geriatric Early Warning Score (GEWS) versus the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) in Predicting Clinical Deterioration in Frail Older Patients. Eur Geriatr Med 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.; Dean, J.; Hartin, J. Using NEWS2: An Essential Component of Reliable Clinical Assessment. Clinical Medicine 2022, 22, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.S.; Choi, Y.; Lim, J.Y.; Kim, K.; Choi, Y.H.; Lee, D.H.; Bae, S.J. The Clinical Frailty Scale Improves Risk Prediction in Older Emergency Department Patients: A Comparison with qSOFA, NEWS2, and REMS. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 12584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardy, E.R.; Lasserson, D.; Barker, R.O.; Hanratty, B. NEWS2 and the Older Person. Clinical Medicine 2022, 22, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Conte, S.; Fruscoloni, G.; Cartocci, A.; Vitiello, M.; De Marco, M.F.; Cevenini, G.; Barbini, P. Development and Validation of a NEWS2-Enhanced Multivariable Prediction Model for Clinical Deterioration and In-Hospital Mortality in Hospitalized Adults. Medicina 2025, 61, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wretborn, J.; Munir-Ehrlington, S.; Hörlin, E.; Wilhelms, D.B. Addition of the Clinical Frailty Scale to Triage Tools and Early Warning Scores Improves Mortality Prognostication at 30 Days: A Prospective Observational Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2024, 5, e13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzoub, M.; Joks, R. Charlson Comorbidity Index and National Early Warning Score 2: Predictors of Mortality in COVID-19 Hospitalizations. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2022, 149, AB100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).