1. Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a prevalent degenerative joint disorder and a leading cause of chronic pain, functional limitation, and disability worldwide [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Recent global estimates indicate that osteoarthritis affects more than 650 million individuals aged 40 years and older, with the knee being the most commonly involved joint [

5,

6]. The burden of Knee OA continues to increase due to population ageing, rising obesity rates, and longer life expectancy, resulting in substantial socioeconomic and healthcare impacts [

5,

7].

Current management of Knee OA primarily focuses on symptom relief rather than disease modification. Pharmacological treatments such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids may reduce pain in the short term but do not halt disease progression and are associated with gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular adverse effects when used long term [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. These limitations have driven interest in adjunctive and non-pharmacological interventions that may offer symptom improvement with a more favourable safety profile [

4,

9].

Marine-derived omega-3 fatty acids have been widely investigated for their anti-inflammatory properties and potential benefits in musculoskeletal disorders [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Krill oil, derived from Antarctic krill (

Euphausia superba), represents a distinct source of omega-3 fatty acids in which eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are predominantly bound to phospholipids, potentially enhancing bioavailability compared with conventional fish oil [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In addition, krill oil contains astaxanthin, a potent antioxidant that may mitigate oxidative stress, a key contributor to osteoarthritis pathophysiology [

23,

24,

25].

Several randomized controlled trials have evaluated krill oil supplementation in knee pain [

26,

27,

28] and knee osteoarthritis [

19,

29,

30], but their findings have been inconsistent. Moreover, previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported conflicting conclusions, partly due to heterogeneous study populations and inclusion of non-specific knee pain conditions rather than clinically defined Knee OA [

31,

32]. Therefore, an updated and focused systematic review and meta-analysis restricted to randomized controlled trials enrolling patients with clinically diagnosed knee osteoarthritis is warranted to clarify the efficacy and safety of krill oil supplementation in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [

33]. The study protocol was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD420251012831.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) population: adults (≥18 years) with clinically or radiographically diagnosed knee osteoarthritis; (2) intervention: oral krill oil supplementation at any dose or duration; (3) comparison: placebo, no intervention, or standard care; (4) primary outcome: knee pain; and (5) secondary outcomes: physical function, stiffness, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), lipid profile parameters, and adverse events. Only randomized controlled trials were included. No restrictions were applied with respect to language or publication status.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Scopus, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, and EBSCOhost from inception to November 28, 2025. Additional searches were performed in ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) to identify unpublished or ongoing trials. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms related to “knee osteoarthritis” and “krill oil”. The full search strategy for all databases is provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full-text articles to determine eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, with consultation of a third reviewer when necessary. Data extraction was performed independently using a standardized data collection form. Extracted data included study characteristics, country, sample size, participant demographics, diagnostic criteria, intervention dose and duration, comparator, outcome measures, and reported results.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was change in knee pain from baseline, assessed using validated pain scales (Huskisson). Secondary outcomes included changes in physical function and stiffness, inflammatory biomarkers (hs-CRP), lipid profile parameters, and the incidence of adverse events. Functional outcomes were assessed using disease-specific instruments validated for osteoarthritis populations [

34]. Planned subgroup or sensitivity analyses based on krill oil dosage or treatment duration were not conducted due to the limited number of eligible studies.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias of included studies was assessed independently by two reviewers using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool [

35], which evaluates bias across five domains: the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selection of the reported result. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4. Continuous outcomes were pooled using mean differences (MD) or standardized mean differences (SMD), as appropriate, while dichotomous outcomes were summarized using risk ratios (RR), each with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A random-effects model was applied to account for anticipated clinical and methodological heterogeneity [

36]. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic [

37], with values greater than 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. Formal assessment of publication bias was not performed due to the small number of included studies.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

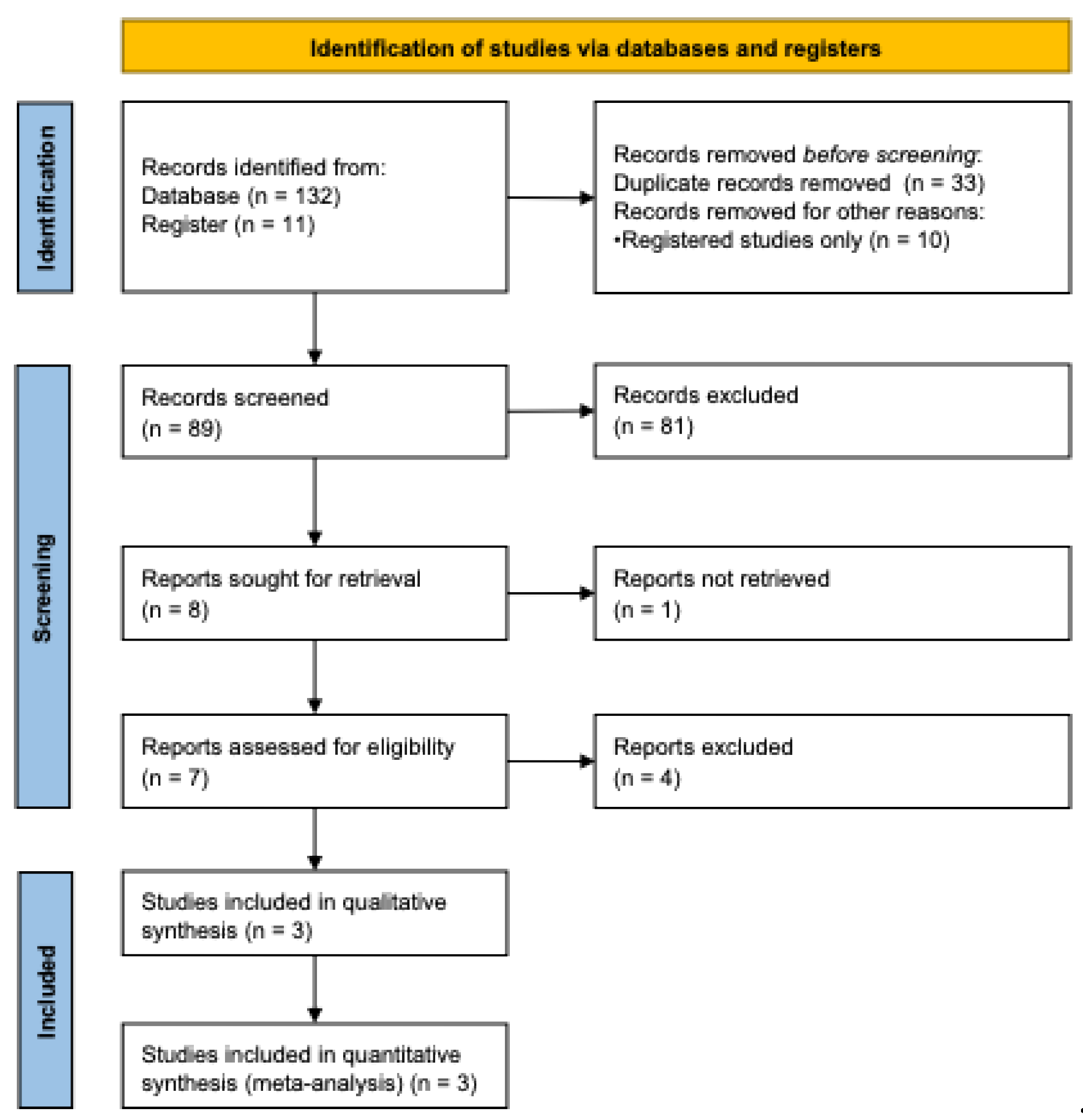

The study selection process is illustrated in

Figure 1. Following a comprehensive literature search and screening process, three randomized controlled trials met the predefined eligibility criteria and were included in the final meta-analysis [

19,

29,

30]. The included studies were conducted in Australia and South Korea and collectively enrolled a total of 597 participants. Of these, 267 participants received krill oil supplementation, while 330 participants were allocated to placebo groups.

The study selection process is illustrated in

Figure 1. Following a comprehensive literature search and screening process, three randomized controlled trials met the predefined eligibility criteria and were included in the final meta-analysis [

19,

29,

30]. The included studies were conducted in Australia and South Korea and collectively enrolled a total of 597 participants. Of these, 267 participants received krill oil supplementation, while 330 participants were allocated to placebo groups.

The daily dose of krill oil ranged from 1 to 4 g, and treatment durations varied between 12 and 24 weeks [

19,

29,

30]. In two trials, krill oil was administered in combination with additional active components, including astaxanthin and hyaluronic acid [

19,

29]. Control groups received placebo capsules containing mixed vegetable oils or other inert substances matched in appearance. Detailed characteristics of the included studies are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias of the included randomized controlled trials was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool. Overall, all three studies were judged to have some concerns regarding risk of bias [

19,

29,

30]. Uncertainty was primarily related to the randomization process, as methods for sequence generation and allocation concealment were not fully described in some trials. Bias due to deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, and outcome measurement was generally assessed as low. Concerns regarding selective reporting were noted for some secondary outcomes. A detailed summary of the risk of bias assessment across all domains is presented in

Supplementary Figure S1.

3.3. Study Selection and Characteristics

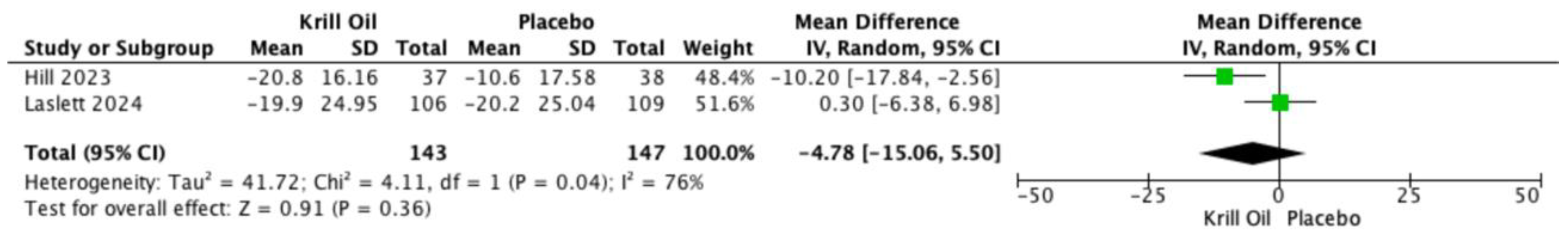

Knee pain was the primary outcome and was assessed using both the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the WOMAC pain subscale. Two randomized controlled trials reported VAS pain outcomes [

19,

30]. Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference between krill oil supplementation and placebo (mean difference [MD] −4.78; 95% confidence interval [CI] −15.06 to 5.50;

Figure 2), with substantial heterogeneity observed across studies.

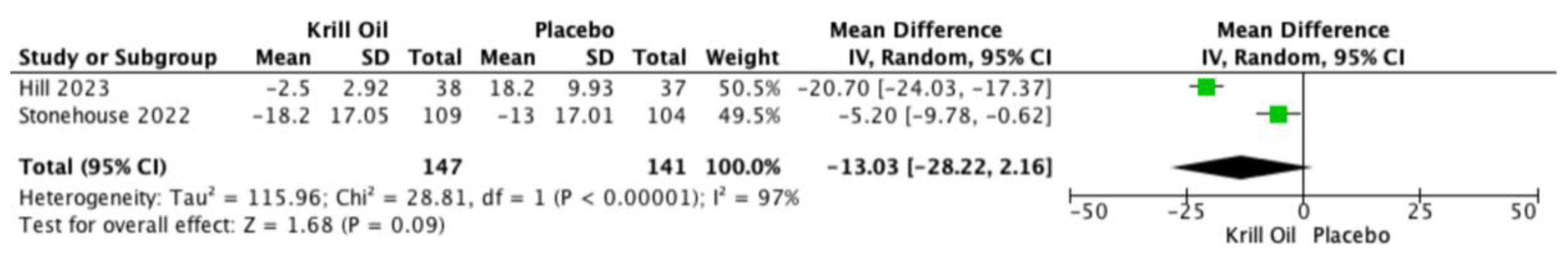

All three trials reported WOMAC pain outcomes [

19,

29,

30]. Meta-analysis demonstrated a reduction in WOMAC-assessed knee pain favoring krill oil supplementation; however, this effect did not reach statistical significance (MD −13.03; 95% CI −28.22 to 2.16;

Figure 3). Considerable heterogeneity was observed among studies.

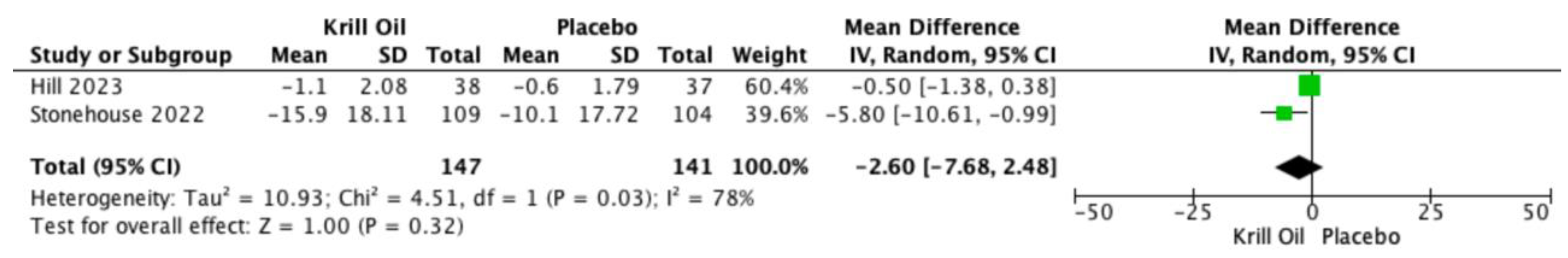

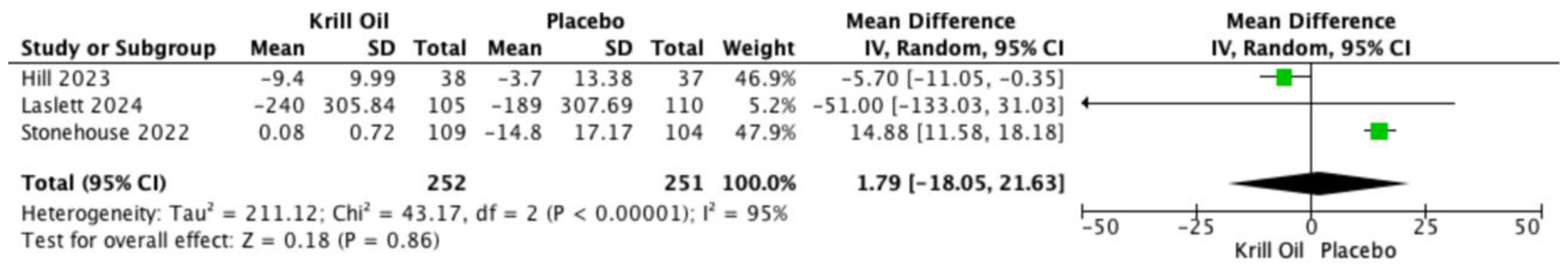

Pooled analyses also showed reductions in WOMAC-assessed joint stiffness (MD −2.60; 95% CI −7.68 to 2.48;

Figure 4) and physical function (MD 1.79; 95% CI −18.05 to 21.63;

Figure 5). These differences were not statistically significant, and substantial heterogeneity was observed for both outcomes.

3.4. Study Selection and Characteristics

Two studies reported outcomes related to inflammatory and cardiometabolic biomarkers, including high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) [

19,

29]. Pooled analyses demonstrated no statistically significant differences between krill oil supplementation and placebo for any of these biomarkers. Effect estimates were generally close to the null, and heterogeneity across studies ranged from low to moderate. Forest plots for these secondary outcomes are presented in Supplementary

Figures S2–S5.

3.5. Study Selection and Characteristics

All included randomized controlled trials reported adverse events associated with krill oil supplementation [

19,

29,

30]. Pooled analysis of overall adverse events showed no statistically significant difference between the krill oil and placebo groups (odds ratio [OR] 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.52 to 2.89), with no observed heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Analysis of gastrointestinal adverse events also demonstrated no statistically significant difference between groups (OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.51 to 1.09), with low heterogeneity (I² = 29%). Reported adverse events were predominantly mild gastrointestinal symptoms, such as bloating or dyspepsia. No serious adverse events attributable to krill oil were reported across the included studies. Forest plots summarizing overall and gastrointestinal adverse events are presented in

Supplementary Figures S6 and S7.

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that krill oil supplementation has been investigated as a potential adjunctive intervention for knee osteoarthritis, with overall trends toward improvement in patient-reported outcomes [

19,

29,

30]. In contrast, pain assessed using the Visual Analog Scale did not show a statistically significant reduction, which is consistent with findings from individual randomized controlled trials reporting VAS outcomes [

19,

30]. Across studies, physical function outcomes showed numerically favorable trends, although these did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that any potential effects may be modest and variable [

19,

31,

32].

The discrepancy between WOMAC- and VAS-based pain outcomes may reflect differences in measurement sensitivity, construct validity, or timing of assessment, as well as limited statistical power due to the small number of trials reporting VAS outcomes [

31,

32,

34,

38]. WOMAC is a multidimensional, disease-specific instrument that captures pain in functional contexts, whereas VAS represents a unidimensional measure of pain intensity, which may be less sensitive to change in chronic conditions such as knee osteoarthritis [

32,

34]. These methodological differences may partially explain why numerical reductions were observed for WOMAC-based outcomes but not consistently reflected in VAS-assessed pain.

Our findings partially align with those of previous meta-analyses. Pimentel et al. [

31], reported that krill oil supplementation did not significantly improve knee pain or stiffness but demonstrated a small benefit in physical function, while Meng et al.[

32], reported statistically significant improvements in WOMAC-based outcomes but not in VAS-measured pain, the present study was restricted to randomized controlled trials enrolling patients with clinically defined knee osteoarthritis and excluded heterogeneous knee pain populations, which may have included individuals without structural joint disease. This stricter inclusion criterion may have reduced clinical heterogeneity and improved the interpretability of pooled estimates, albeit at the cost of a smaller number of eligible studies.[

3,

6]

The observed clinical effects are biologically plausible. Krill oil contains phospholipid-bound omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, which are known to modulate inflammatory pathways by reducing the synthesis of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and promoting the production of specialized pro-resolving mediators [

13,

14,

23]. In addition, krill oil contains astaxanthin, a potent antioxidant that may mitigate oxidative stress, a key contributor to cartilage degradation and synovial inflammation in osteoarthritis [

24,

25,

28]. Despite these mechanistic pathways, no significant changes were observed in systemic inflammatory biomarkers or lipid profiles in the included trials, suggesting that the symptomatic benefits of krill oil may be mediated primarily through localized joint-level effects rather than systemic anti-inflammatory activity [

18,

19,

21,

32].

Methodological heterogeneity across the included trials may also have contributed to variability in effect estimates. Differences in analytical approaches, supplement formulations, and dosages were evident, with some trials employing intention-to-treat analyses and others relying on per-protocol analyses, which may overestimate treatment effects for subjective outcomes such as pain and function [

29,

30,

36,

37]. In addition, two trials used multi-component formulations containing astaxanthin or hyaluronic acid, which may have augmented observed effects and limited direct comparability across studies [

19,

29]. The presence of substantial heterogeneity and consistent ‘some concerns’ risk of bias across included trials further limits the certainty of the pooled estimates.

Across all included trials, krill oil supplementation was generally well tolerated, with no statistically significant difference in adverse event rates compared with placebo [

19,

29,

31,

32]. Reported adverse events were predominantly mild gastrointestinal symptoms, and no serious adverse events attributable to krill oil were reported, suggesting a favourable short-term safety profile [

18,

28].

Taken together, these findings suggest that krill oil may represent a safe adjunctive option for symptom management in knee osteoarthritis [

8,

9]. These findings should not be interpreted as evidence for routine clinical use. However, the limited number of eligible trials and relatively short follow-up durations preclude definitive conclusions regarding long-term efficacy. Further large-scale, high-quality randomized controlled trials with standardized formulations, consistent analytical frameworks, and longer follow-up periods are warranted to confirm these findings and clarify the long-term role of krill oil in knee osteoarthritis management.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that krill oil supplementation has been explored as a potential adjunctive intervention for knee osteoarthritis. The available evidence suggests numerical improvements and favorable trends in WOMAC-based patient-reported outcomes, although these effects did not consistently reach statistical significance. No clear benefits were observed for Visual Analog Scale–assessed pain or systemic biomarkers, and krill oil appeared to be well tolerated in the short term. Given the limited number of trials and short follow-up durations, further high-quality randomized controlled trials are required to clarify its clinical effectiveness and long-term role in knee osteoarthritis management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.; methodology, A.H. and S.C.A.N.; formal analysis, A.H. and Y.R.H.S.; investigation, S.C.A.N., Y.R.H.S., and F.R.; resources, S.C.A.N. and Y.R.H.S.; data curation, A.H. and S.C.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H. and S.C.A.N.; writing—review and editing, A.H., S.C.A.N., H.D.S., Y.R.H.S., F.R., M.M.M., and R.P.S.; visualization, M.M.M. and H.D.S.; supervision, A.H.; project administration, Y.R.H.S., H.D.S. and R.P.S.; validation, A.H. and S.C.A.N.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable, as this study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of published data and did not involve direct interaction with human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all researchers whose work was included in this systematic review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OA |

Osteoarthritis |

| RCT |

Randomized controlled trial |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO |

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

| WOMAC |

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index |

| EPA |

Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| DHA |

Docosahexaenoic acid |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| hs-CRP |

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| HDL |

High-density lipoprotein |

| LDL |

Low-density lipoprotein |

| MD |

Mean difference |

| SMD |

Standardized mean difference |

| RR |

Risk ratio |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| I² |

Inconsistency index |

References

- Steinmetz, JD; Culbreth, GT; Haile, LM; Rafferty, Q; Lo, J; Fukutaki, KG; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5(9), e508–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M; Smith, E; Hoy, D; Nolte, S; Ackerman, I; Fransen, M; et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014, 73(7), 1323–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S; Kolahi, AA; Smith, E; Hill, C; Bettampadi, D; Mansournia, MA; et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020, 79(6), 819–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, DJ; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2019, 393(10182), 1745–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Osteoarthritis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990-2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol 2023, 5(9), e508–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, A; Li, H; Wang, D; Zhong, J; Chen, Y; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29–30:100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y; Jiang, W; Wang, W. Global burden of osteoarthritis in adults aged 30 to 44 years, 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024, 25(1), 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg, MC; Altman, RD; April, KT; Benkhalti, M; Guyatt, G; McGowan, J; et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 64(4), 465–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannuru, RR; Osani, MC; Vaysbrot, EE; Arden, NK; Bennell, K; Bierma-Zeinstra, SMA; et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019, 27(11), 1578–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinusas, K. Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 2012, 85(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- da Costa, BR; Reichenbach, S; Keller, N; Nartey, L; Wandel, S; Jüni, P; et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017, 390(10090), e21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, DG; Christophersen, C; Brown, SM; Mulcahey, MK. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Sportsmed 2021, 49(4), 381–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1851(4), 469–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: from molecules to man. Biochem Soc Trans. 2017, 45(5), 1105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senftleber, NK; Nielsen, SM; Andersen, JR; Bliddal, H; Tarp, S; Lauritzen, L; et al. Marine Oil Supplements for Arthritis Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Nutrients 2017, 9(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Adamo, S; Cetrullo, S; Panichi, V; Mariani, E; Flamigni, F; Borzì, RM. Nutraceutical Activity in Osteoarthritis Biology: A Focus on the Nutrigenomic Role. Cells 2020, 9(5), 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhikh, S; Noskova, S; Ivanova, S; Ulrikh, E; Izgaryshev, A; Babich, O. Chondroprotection and Molecular Mechanism of Action of Phytonutraceuticals on Osteoarthritis. Molecules 2021, 26(8), 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulven, SM; Holven, KB. Comparison of bioavailability of krill oil versus fish oil and health effect. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2015, 11, 511–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonehouse, W; Benassi-Evans, B; Bednarz, J; Vincent, AD; Hall, S; Hill, CL. Krill oil improved osteoarthritic knee pain in adults with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis: a 6-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2022, 116(3), 672–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tou, JC; Jaczynski, J; Chen, YC. Krill for human consumption: nutritional value and potential health benefits. Nutr Rev. 2007, 65(2), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, A; Sarkkinen, E; Tapola, N; Niskanen, T; Bruheim, I. Bioavailability of fatty acids from krill oil, krill meal and fish oil in healthy subjects--a randomized, single-dose, cross-over trial. Lipids Health Dis 2015, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, TPT; Hoang, TV; Cao, PTN; Le, TTD; Ho, VTN; Vu, TMH; et al. Comparison of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids bioavailability in fish oil and krill oil: Network Meta-analyses. Food Chem X 2024, 24, 101880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, CN; Savill, J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol 2005, 6(12), 1191–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambati, RR; Siew Moi, P; Ravi, S; Aswathanarayana, RG. Astaxanthin: Sources, Extraction, Stability, Biological Activities and Its Commercial Applications—A Review. Mar Drugs 2014, 12(1), 128–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıyer, ET; Baş, M; Yüksel, M. Comparative Analysis of the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Krill and Fish Oil. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26(15), 7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y; Fukushima, M; Sakuraba, K; Sawaki, K; Sekigawa, K. Krill Oil Improves Mild Knee Joint Pain: A Randomized Control Trial. Gagnier JJ, editor. PLOS ONE 2016, 11(10), e0162769. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, H; Matahira, Y; Suzuki, N. Effects of ingestion of Krill oil on quality of life related to mild knee pain: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2017, 45, 999–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, L. Evaluation of the effect of Neptune Krill Oil on chronic inflammation and arthritic symptoms. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007, 26(1), 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, WS; Dohnalek, MH; Ha, Y; Kim, SJ; Jung, JC; Kang, SB. A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of a Krill Oil, Astaxanthin, and Oral Hyaluronic Acid Complex on Joint Health in People with Mild Osteoarthritis. Nutrients 2023, 15(17), 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laslett, LL; Scheepers, LEJM; Antony, B; Wluka, AE; Cai, G; Hill, CL; et al. Krill Oil for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 331(23), 1997–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, T; Queiroz, I; Florêncio de Mesquita, C; Gallo Ruelas, M; Leandro, GN; Ribeiro Monteiro, A; et al. Krill oil supplementation for knee pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32(5), 3109–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J; Wang, X; Li, Y; Xiang, Y; Wu, Y; Xiong, Y; et al. Krill oil for knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2025, 104(7), e41566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, MJ; McKenzie, JE; Bossuyt, PM; Boutron, I; Hoffmann, TC; Mulrow, CD; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, N; Buchanan, WW; Goldsmith, CH; Campbell, J; Stitt, LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988, 15(12), 1833–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, JAC; Savović, J; Page, MJ; Elbers, RG; Blencowe, NS; Boutron, I; et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DerSimonian, R; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986, 7(3), 177–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, JPT; Thompson, SG; Deeks, JJ; Altman, DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327(7414), 557–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huskisson, EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet Lond Engl. 1974, 2(7889), 1127–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).