1. Introduction

The vertebrate respiratory system is among the most structurally complex and functionally dynamic organ systems in biology, shaped by evolutionary pressures to meet the escalating bioenergetic demands of multicellular organisms. As atmospheric oxygen levels rose and mitochondria became central to cellular metabolism, selective pressures favored the development of increasingly specialized gas-exchange structures. In terrestrial vertebrates, this culminated in the highly organized architecture of the lungs—comprising branching airways, delicate alveolar sacs, and an expansive capillary network—designed to maximize oxygen uptake and eliminate carbon dioxide.

Embedded within this respiratory machinery is an evolutionarily conserved hormonal control axis, centered on the glucocorticoid receptor alpha (GRα). Rather than functioning solely as an acute stress-response receptor, GRα shapes developmental programs and day-to-day pulmonary physiology. It influences epithelial lineage specification, surfactant system maturation, barrier and immune tone, vascular function, and mitochondrial adaptation—allowing the respiratory system to dynamically adjust to developmental cues, environmental fluctuations, and systemic stress. Through this layered integration, the GC–GRα system has contributed to the evolutionary refinement of lung structure and function, enabling coordination between pulmonary physiology and the broader organ systems that maintain whole-body homeostasis.

This manuscript offers a comprehensive review of the evolutionary, developmental, and molecular foundations of pulmonary structure and function, with particular focus on GRα-mediated regulation.

Section 1 examines the origins of respiratory adaptations shaped by shifting oxygen availability.

Section 2 outlines the emergence of glucocorticoid signaling and its integration into vertebrate strategies for meeting respiratory demands.

Section 3 delineates GRα's indispensable role in fetal lung maturation.

Section 4 analyzes the anatomical complexity and functional integration of the adult pulmonary system. Finally,

Section 5 synthesizes how GC–GRα signaling coordinates respiratory physiology across multiple subsystems to sustain efficient gas exchange, preserve barrier integrity, and maintain immune and metabolic homeostasis.

2. Evolutionary and Embryological Origins of the Respiratory System: Linking Bioenergetic Demand to Structural Innovation

2.1. Bioenergetic Pressures and the Need for Oxygen Exchange

The evolution of the vertebrate respiratory system is fundamentally tied to the progressive rise in atmospheric oxygen (O₂) and the emergence of mitochondria as the central engines of cellular metabolism. Following the Great Oxygenation Event approximately 2.4 billion years ago, eukaryotic cells (cells that contain a true nucleus and membrane-bound organelles, distinguishing them from simpler prokaryotic cells) acquired mitochondria through endosymbiosis (one cell living inside another and becoming an organelle), enabling aerobic respiration and a dramatic expansion in ATP-generating capacity. This transformative bioenergetic shift imposed selective pressure on emerging multicellular organisms to develop increasingly sophisticated mechanisms for acquiring, transporting, and regulating oxygen delivery—particularly to tissues with high mitochondrial density and oxidative demand.

As a result, the respiratory system evolved not simply as a passive conduit for gas diffusion but as a dynamic, highly regulated network designed to match oxygen availability with the metabolic needs of complex cellular systems. This bioenergetic framework established the foundation for the structural and functional innovations that characterize the vertebrate lung. (

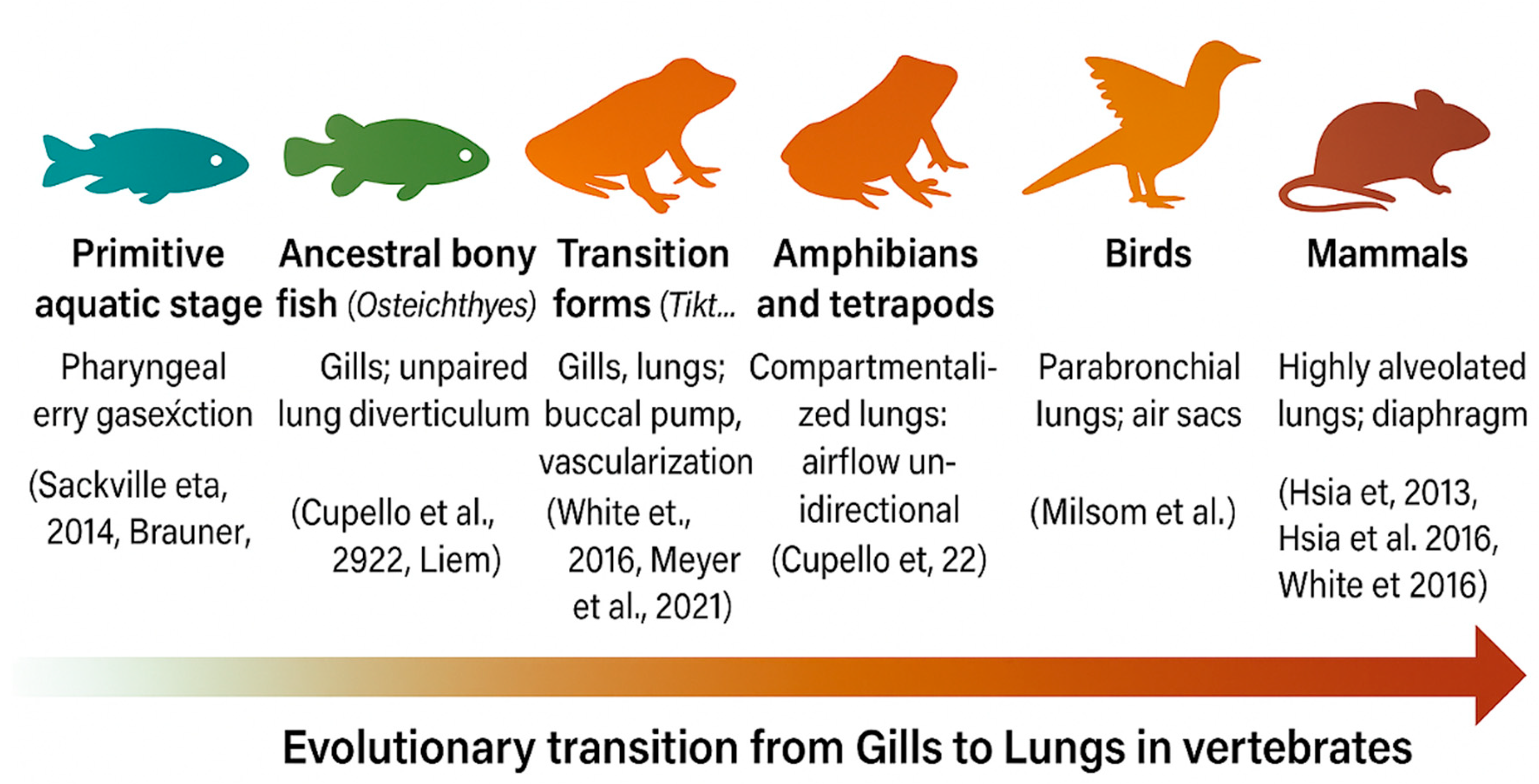

Figure 1, Evolution of respiratory cells).

2.2. From Gills to Lungs: Evolutionary Transitions in Vertebrate Respiration

The transition from water to land required profound respiratory innovations and adaptive restructuring of gas-exchange mechanisms. Over roughly 400 million years, vertebrates evolved from gill-based to lung-based respiration, enabling survival in variable oxygen environments and the colonization of terrestrial ecosystems (

Figure 1,

Evolution of respiratory cells). During this transition, hormonal and molecular regulatory systems—including glucocorticoid signaling—co-evolved with respiratory structures, forming an increasingly integrated physiological axis (

Figure 2,

Evolutionary Integration of the Glucocorticoid Receptor).

In mammals, progressive specialization of GRα signaling supported lung maturation by regulating surfactant protein A (SP-A) and ATP-binding cassette transporter A3 (ABCA3), as well as extracellular matrix remodeling, vascular development, and oxygen homeostasis. These integrated functions established GRα as the central regulatory hub for respiratory development, stress adaptation, and postnatal homeostasis. (The authors acknowledge ChatGPT's assistance in creating this figure.)

Gills, which evolved before the last common ancestor of vertebrates, initially functioned in ion exchange and acid–base regulation and only later adapted for oxygen uptake through countercurrent gas exchange. [

1,

2,

3] Lungs subsequently appeared as unpaired outpouchings of the foregut in early bony fishes (Osteichthyes) and later evolved into paired organs in tetrapods, significantly improving respiratory efficiency. [

4,

5,

6] In ray-finned fishes, the swim bladder represents a modified lung, highlighting their shared evolutionary origin. [

7]

Transitional species such as

Tiktaalik, lungfish, and

Polypterus retain both gills and lungs, serving as extant models of bimodal respiration that bridge aquatic and terrestrial life. [

8,

9,

10] The transition to land required major physiological innovations—

including greater pulmonary compliance, expanded vascularization, and more efficient surfactant production

—alongside the co-evolution of endocrine pathways and glucocorticoid signaling, which became essential for developmental regulation. [

4,

11,

12]

Figure 3 illustrates the key milestones in vertebrate respiratory evolution, showing the progressive transition from gill- to lung-based respiration and the growing integration of GRα signaling into pulmonary physiology.

Table 1 (

Evolutionary Progression of Vertebrate Respiratory Systems and Associated Corticoid Signaling Functions) complements this overview by summarizing structural, physiological, and endocrine innovations that occurred across vertebrate lineages and their relevance to the emergence and refinement of GRα-centered respiratory homeostasis.

Across lineages, birds evolved rigid parabronchial lungs with air sacs that enable unidirectional airflow, while crocodilians independently developed a similar mechanism—a striking case of convergent evolution. [

13,

14] In mammals, the emergence of highly alveolated lungs and diaphragm-driven negative-pressure breathing enabled continuous, high-volume ventilation and supported greater aerobic metabolic capacity. [

8,

15] Together, these structural refinements laid the developmental and physiological groundwork for embryonic lung formation and the later incorporation of GRα-signaling in respiratory adaptation.

2.3. Embryological Specification of the Respiratory Tract

The respiratory system begins as a ventral outpouching of the foregut endoderm, forming the laryngotracheal diverticulum. Proper separation from the esophagus is essential; when this process fails, tracheoesophageal fistulas may develop. [

8,

16] Development of the respiratory tract requires continuous epithelial–mesenchymal communication and is regulated by several key molecular pathways—including Wingless/Integrated (Wnt)

, Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF)

, Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP)

, and Sonic Hedgehog (SHH)

—which act together to direct airway branching and lung morphogenesis

.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling establishes the proximal–distal axis of the developing lung, determining which regions form conducting airways and which become gas-exchanging structures. Wnt also activates FGF10 and BMP4, linking these pathways into a unified regulatory network. [

17,

18] FGF10, produced by surrounding mesenchyme, stimulates airway bud outgrowth and epithelial branching, whereas FGF9 helps define distal lung identity. [

19,

20] BMP4, concentrated at the distal tips of developing airways, fine-tunes branching morphogenesis and promotes differentiation of alveolar type II cells that produce surfactant. [

21] SHH signaling delineates the tracheoesophageal boundary and regulates mesenchymal proliferation, thereby maintaining airway structural integrity.

Together, these pathways coordinate branching morphogenesis—the iterative subdivision of airway buds that forms the bronchial tree—and establish the regional patterning that specifies tracheal, bronchial, and alveolar lineages. In late fetal life, GRα-signaling becomes essential for terminal lung maturation: it upregulates surfactant synthesis, promotes alveolar fluid clearance, and prepares the lungs for effective post-natal air breathing (

Figure 2). [

22,

23] Recent high-resolution imaging and single-cell transcriptomic analyses have revealed the precise temporal and spatial coordination of these developmental signals, clarifying how they regulate the epithelial lineage commitment, airway branching, and alveolar differentiation during mammalian lung formation. [

24] Importantly, many of these developmental pathways are re-engaged during lung repair and regeneration in adulthood, underscoring their lifelong contribution to respiratory homeostasis.

2.4. Evolution of Specialized Respiratory Cells

Building on the structural transition from gills to lungs—an evolutionary process extensively characterized by Liem—the cellular and molecular diversification of the mammalian respiratory system represents a second significant evolutionary refinement. [

5] This diversification did not arise de novo, but through the progressive modification and repurposing of ancestral respiratory programs. Specialized respiratory cells evolved through both innovation and repurposing of ancestral mechanisms, transforming ancient gill-based programs into complex networks of alveolar, vascular, and sensory cells optimized for terrestrial oxygen requirements and the high metabolic demands of endothermy.

Evolutionary Origins and Cellular Specialization. Single-cell transcriptomic studies reveal that the mammalian alveolar capillary network contains two major endothelial populations with distinct functions. This specialization represents a defining evolutionary innovation in mammalian lung design. Aerocytes (aCap cells) are a mammal-specific endothelial subtype specialized for gas exchange and immune surveillance. In contrast, general capillary (gCap) cells regulate capillary perfusion and function as progenitor cells that support ongoing endothelial maintenance and repair. This dual specialization, absent in reptiles and other non-mammalian vertebrates, represents an evolutionary innovation that significantly improved gas-transfer efficiency while strengthening local immune defense. [

25,

26,

27,

28]

Comparative analyses across mammals, reptiles, and birds show that while core gene-expression programs in alveolar type I (AT1) and type II (AT2) cells are conserved, mammals developed additional intracellular signaling modules and distinct ultrastructural adaptations that sustain endothermy and support the continuous, high oxygen demand of aerobic metabolism

. [

26,

29,

30] These refinements reflect selective pressure not only for efficient gas exchange, but also for metabolic resilience under sustained aerobic load.

Hypoxia-Sensitive Cells and Ancestral Repurposing. Two principal oxygen-sensing cell types—pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNECs) and carotid-body glomus cells—illustrate how ancient oxygen-sensing mechanisms were adaptivel

y repurposed during vertebrate evolution. These cells likely derive from neuroepithelial oxygen-sensing programs originally present in fish gills. In mammals, PNECs (endoderm-derived) serve as environmental sentinels within the airway epithelium, whereas glomus cells (neural-crest-derived) monitor arterial oxygen tension. This evolutionary transition from externally located to internally integrated oxygen sensing represented a critical step toward precise physiological self-regulation in air-breathing vertebrates. [

31,

32,

33,

34]

Regeneration and Developmental Plasticity. Beyond their role in gas exchange, gCap cells serve as endothelial progenitors essential for vascular repair. Following injury, a transient population of stem-like endothelial cells regenerates both gCap and aerocyte populations, restoring capillary integrity and function. [

27,

28] This regenerative capacity underscores the dynamic, rather than static, nature of the alveolar microvasculature.

Endothelial specification depends on tightly regulated signaling networks and developmentally programmed alternative-splicing events, particularly around birth. These mechanisms support the rapid transition to air breathing and ensure optimal postnatal gas-exchange efficiency. [

26,

35,

36]

Developmental Conservation and Biomechanical Innovation. These evolutionary refinements are recapitulated during embryogenesis, where conserved signaling pathways—including Wnt, FGF, Notch, and GRα-dependent glucocorticoid signaling—govern the emergence of specialized respiratory subtypes. [

24,

35] This recurrence highlights deep conservation of developmental logic, even as structural complexity increased.

The mammalian bronchial tree and acinar architecture are optimized for space-filling branching geometry, minimal diffusion distance, and maximal gas-exchange surface area—principles that trace back to the primitive vascular transport systems of early metazoans. [

37]

Complementing these structural refinements, the evolution of the muscular diaphragm introduced a major biomechanical innovation. Negative-pressure ventilation enabled high-volume tidal breathing, sustained aerobic metabolism, and decoupling of respiration from locomotion—forming the physiological foundation of endothermy. [

5]

These structural and biochemical innovations occurred in parallel with the progressive evolutionary specialization of GR signaling from its ancestral corticoid receptor. As developed further in section 2, this molecular coevolution provided an endocrine framework that integrated respiratory development with metabolic and stress adaptation, culminating in coordinated lung maturation, surfactant production, and oxygen homeostasis. (

Figure 2).

2.5. Cellular Crosstalk and Structural Complexity

Building on both evolutionary adaptations and developmental processes, the mature respiratory system exhibits remarkable cellular heterogeneity and functional plasticity, supporting lifelong capacities for defense, adaptation, and repair. Advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and lineage-tracing approaches demonstrated that respiratory cell populations engage in continuous, bidirectional communication across the lifespan, actively remodeling tissue architecture and function in response to metabolic needs and environmental challenges. [

38,

39,

40]

The airway and alveolar epithelia comprise multiple specialized cell types—secretory, ciliated, basal, and ionocyte populations—each contributing uniquely to barrier integrity, environmental sensing, and immune coordination. Disruption of epithelial–mesenchymal signaling or imbalances within epithelial cell subpopulations underlie many chronic and infectious respiratory diseases.

[39,42] Beyond the epithelium, mesenchymal, immune, vascular, and neuroendocrine cells display substantial phenotypic diversity and exhibit context-dependent reprogramming, highlighting the adaptive versatility of the respiratory microenvironment. [

41,

42,

43]

Single-cell and lineage-tracing studies have further demonstrated that distinct stem and progenitor populations sustain homeostasis and orchestrate regeneration following injury. Epithelial cells can undergo lineage transitions, while fibroblasts and endothelial cells dynamically modulate their activation state in response to stress, exemplifying multi-lineage plasticity that underlies effective tissue repair. [

39,

44] Together, these stem and progenitor populations display context-dependent plasticity that supports both routine homeostasis and effective regeneration after injury. [

38]

Cellular crosstalk among epithelial, mesenchymal, endothelial, and immune lineages is essential for coordinating lung growth, the physiologic transition to air breathing at birth, and post-injury repair. The respiratory immune network is spatially compartmentalized, with distinct programs in the upper versus lower airways—an evolutionary adaptation that protects delicate gas-exchange surfaces while maintaining mucosal tolerance. [

42] Finally, integrative control extends to the neural level: specialized serotonergic neuron subtypes within the brainstem are developmentally programmed to regulate distinct components of respiratory rhythm, chemosensitivity, and ventilatory drive. [

45]

2.6. Summary and Evolutionary Significance

From its origins in aquatic respiration to the highly specialized alveolated lungs of mammals, the respiratory system exemplifies an evolutionary continuum shaped by rising energy demands and the transition to terrestrial life. Structural adaptation and repurposing of ancestral gills, integrated with conserved developmental signaling networks, enabled the emergence of specialized epithelial, endothelial, and neuroendocrine lineages that sustain oxygen homeostasis and metabolic resilience. These same pathways, refined through evolution, continue to govern lung growth, postnatal adaptation, and regenerative repair throughout life. The mature respiratory system’s cellular heterogeneity and dynamic crosstalk reflect the culmination of these evolutionary and developmental processes—forming an integrative design that unites efficient gas exchange with lifelong adaptability, robust immune defense, and ongoing structural renewal.

Figure 1 summarizes the major cellular and structural innovations underpinning this evolutionary progression, from ancestral gill-based respiration to the specialized alveolar architecture of mammals. Understanding these evolutionary principles provides a unifying framework for interpreting congenital lung disorders, improving the management of acute and chronic respiratory diseases, and guiding strategies to restore respiratory homeostasis across the spectrum of critical illness. [

4,

7,

12,

15,

38]

The evolutionary innovations that enabled efficient oxygen uptake and metabolic stability also required the emergence of equally sophisticated regulatory systems to coordinate stress responses, energy distribution, and tissue maturation. Among these, the GRα signaling network evolved as a central integrative mechanism linking environmental stress to cellular and systemic adaptation. Its progressive specialization closely paralleled the evolution of the vertebrate respiratory apparatus, aligning oxygen sensing, metabolic regulation, and developmental control into a unified framework that sustains homeostasis across diverse environmental and physiological transitions.

3. The Evolution of Glucocorticoid Signaling and Its Role in Shaping Vertebrate Respiratory Adaptation

The GRα, a ligand-activated transcription factor, evolved early in vertebrates from a common ancestral corticoid receptor shared with the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). Gene duplication and subsequent sequence divergence produced a receptor with increasingly selective sensitivity to glucocorticoids, enabling more precise regulation of stress adaptation, energy balance, and oxygen homeostasis. [

46,

47,

48]

Throughout vertebrate evolution, GRα signaling became increasingly integrated with hypoxia-sensing pathways, particularly the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) system. This bidirectional crosstalk allows GR to modulate HIF-1–dependent transcription under hypoxic conditions, while hypoxia and HIF-1α activity reciprocally influence GRα’s regulatory capacity. GR activation can stabilize HIF-1α by suppressing the Von Hippel–Lindau (pVHL) complex, further linking stress-response and oxygen-sensing networks. [

49,

50,

51,

52]

The emergence of this integrated GR–HIF system was pivotal for the vertebrate transition to terrestrial life, providing a molecular framework that coupled environmental stress detection to coordinated metabolic, immune, and respiratory adaptation. Building on these evolutionary foundations, subsequent sections explore how glucocorticoid signaling continues to coordinate respiratory development, immune regulation, and metabolic resilience. This integrative framework is depicted in

Figure 2, which traces the emergence and specialization of GR signaling in parallel with vertebrate respiratory adaptation.

3.1. Evolutionary Emergence of GR and Its Functional Integration

The GR evolved from an ancestral corticoid receptor shared with the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) through gene duplication and structural diversification, enabling selective responsiveness to glucocorticoid and more precise regulation of stress adaptation and metabolic control. [

46,

47,

53] This molecular innovation coincided with the vertebrate transition from aquatic to terrestrial life, when tight regulation of inflammation, vascular tone, and surfactant synthesis became critical for efficient gas exchange and survival in fluctuating oxygen environments. [

54,

55] Over evolutionary time, permissive mutations, receptor-domain specialization, and the emergence of species-specific isoforms increased the sensitivity and functional breadth of glucocorticoid signaling, deepening GRα’s integration with endocrine, immune, and respiratory pathways. [

48,

56,

57] Collectively, these evolutionary advances established GRα as a central regulatory axis capable of sustaining homeostasis during metabolic demand, inflammatory challenge, and environmental stress. [

54,

55]

3.2. GR Regulation of Lung Development: Evidence from Genetic Models

The GR is indispensable for lung maturation and perinatal adaptation in mammals. Global GR knockout mice die at birth from respiratory failure, exhibiting marked structural immaturity, impaired alveolar formation, and persistent cellular proliferation. [

58,

59] These mice also fail to develop adrenal chromaffin cells, resulting in the absence of the critical catecholamine surge required for lung fluid clearance, surfactant release, and cardiovascular stabilization at birth. [

58,

60] Collectively, these findings demonstrate that GR coordinates pulmonary, endocrine, and vascular maturation—integrating respiratory, metabolic, and hemodynamic transitions essential for successful extrauterine life.

Conditional knockout models have clarified the tissue-specific mechanisms. Loss of GR in lung mesenchymal cells reproduces the global knockout phenotype, confirming that mesenchymal GR is critical for epithelial–mesenchymal crosstalk and proper alveolar differentiation. [

23,

59,

61] Mesenchymal GRα limits excessive cell proliferation, regulates fibroblast differentiation, and supports extracellular matrix (ECM) organization, including elastin and versican synthesis—both required for alveolar septation. [

62,

63] By coordinating growth and differentiation programs across epithelial, mesenchymal, and vascular compartments, GRα ensures synchronized morphogenesis and functional readiness of the perinatal lung.

3.3. Molecular Pathways Under GR Control in Developing Lung

GR orchestrates key molecular programs that coordinate cell proliferation, ECM remodeling, and surfactant synthesis during lung development. GRα suppresses midkine (Mdk), a pro-proliferative growth factor, while inducing p21^CIP1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that halts cell division and promotes differentiation. [

64,

65] In parallel, GRα represses versican (Vcan)—a large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan that drives mesenchymal expansion—and induces ADAMTS12, a protease mediating Vcan turnover, thereby maintaining balanced ECM remodeling and promoting alveolar septation. [

62,

64,

65] Together, these coordinated actions ensure controlled mesenchymal growth, proper elastin deposition, and orderly alveolar septation—processes that are disrupted when GRα is absent.

At the epithelial interface, GR directly enhances transcription of surfactant proteins (SP-A, SP-B) and the ABCA3 lipid transporter, functionally preparing alveolar type II cells for efficient gas exchange and lamellar body formation. [

66,

67,

68,

69] This ABCA3–surfactant module is illustrated in

Figure 2. GR expression peaks late in gestation, coinciding with the fetal cortisol surge and the onset of surfactant production, marking a critical window of glucocorticoid sensitivity required for perinatal respiratory readiness. [

68,

70]

Beyond its critical developmental functions, GRα expression persists across multiple pulmonary cell types, providing ongoing coordination among structural, vascular, immune, and metabolic processes that maintain respiratory homeostasis (

Table 2, Representative Cell Populations Expressing GRα Across the Respiratory System and Their Principal Regulatory Functions Supporting Pulmonary Homeostasis). [

22,

67,

69,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86] This broad distribution across pulmonary cell types underscores GRα’s ongoing function as an integrative regulator coordinating epithelial, mesenchymal, endothelial, and immune pathways essential for lifelong respiratory homeostasis.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate how GRα integrates structural maturation with endocrine timing to ensure a seamless transition from fetal to postnatal respiration. This coordinated developmental strategy not only enables survival at birth but also reflects an evolutionary mechanism in which hormonal signaling anticipates physiologic demands, orchestrates organ maturation, and adapts respiratory function to environmental change. This organizing principle is further developed in the next section.

3.4. Evolutionary and Translational Implications

The indispensability of GRα for perinatal respiratory adaptation reflects strong evolutionary selection for endocrine programs that anticipate parturition and proactively prepare the fetus for the abrupt transition to air breathing. Clinically, this same principle underlies the use of antenatal glucocorticoids to patients at risk of preterm delivery, which accelerates the final maturation steps necessary for effective pulmonary gas exchange. [

22,

67,

69]

Recent evidence underscores the need for greater precision in translating this evolutionary principle to clinical care. Findings from both animal and human studies demonstrate that therapeutic efficacy depends critically on the timing, dosage, and appropriate patient selection, emphasizing the importance of defined gestational-age windows, dosing limits, and the avoidance of non-indicated exposure. Emerging data on long-term neurodevelopmental vulnerability further highlight the importance of aligning treatment with GRα’s intrinsic developmental timing and tissue-specific sensitivity. [

23,

87,

88] Moreover, dysregulation of GRα signaling during critical developmental windows may imprint enduring susceptibility to chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma and COPD—reinforcing the importance of balancing short-term perinatal gains with consideration of lifelong outcomes. [

89]

Section Summary and Translational Implications

In summary, GRα exemplifies an evolutionary innovation that bridges endocrine signaling with respiratory adaptation. The emergence of glucocorticoid signaling represents a pivotal turning point in vertebrate evolution, enabling the development of complex respiratory structures required for terrestrial life. In the mammalian lung, GRα regulates proliferation, differentiation, and tissue architecture through coordinated mesenchymal–epithelial crosstalk and precise transcriptional control. Its evolutionary conservation and proven clinical relevance underscore GRα’s central role not only in developmental physiology but also in preserving and restoring respiratory homeostasis across acute, chronic, and critical illness.

4. Glucocorticoid Receptors in Fetal Lung Development and Respiratory Function

GC signaling through the GRα is essential for the proper development and maturation of the fetal respiratory tract. This pathway regulates a broad spectrum of cellular processes, including mesenchymal and epithelial cell differentiation, progenitor proliferation, ECM remodeling, and surfactant production—laying the foundation for effective postnatal respiration. In the following section, we explore how GRα integrates these diverse developmental programs into a coordinated regulatory network that prepares the lung for birth and supports the abrupt transition to extrauterine life.

4.1. Mesenchymal Differentiation and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Crosstalk

GRa signaling within pulmonary mesenchymal cells is indispensable for the differentiation of proliferative mesenchymal progenitors into matrix-producing fibroblasts and for orchestrating epithelial–mesenchymal crosstalk during lung development. This differentiation process coordinates mesenchymal maturation with ECM remodeling and activation of signaling pathways—including VEGF, JAK-STAT, and WNT—that guide alveolar epithelial progenitors toward mature type I (AT1) and type II (AT2) lineages. [

23,

63,

90]

Targeted deletion of GRα in mesenchymal cells prevents the transition of mesenchymal progenitors into matrix fibroblasts, resulting in defective ECM-gene expression

(Fn1

, Col16a4,

Eln), excessive proliferation of SOX9⁺ epithelial progenitors, and failure of AT1/AT2 maturation. [

23,

61,

91] These defects highlight the non-cell-autonomous regulatory influence of mesenchymal GRα on epithelial differentiation and lung morphogenesis.

By coordinating matrix remodeling and paracrine signaling (see

Section 2.3), mesenchymal GRα ensures balanced growth and proper alveolar septation. [

61,

62] Conversely, deletion of GRα in epithelial or endothelial compartments has relatively minimal structural effect, underscoring the dominant regulatory role of mesenchymal GRα in coordinating epithelial differentiation through paracrine signaling. [

63,

92] This compartment-specific hierarchy indicates that mesenchymal GRα functions as a central organizer of developmental signaling, integrating extracellular matrix dynamics with epithelial lineage progression.

Together, these GRα-driven programs integrate matrix remodeling with growth-factor balance to ensure coordinated mesenchymal differentiation and epithelial maturation. [

23,

93]

4.2. Transcriptional Regulation and Surfactant Synthesis

Glucocorticoids modulate gene expression in the developing lung by activating the GR, which directly binds to DNA and recruits coactivators to regulate key transcriptional programs. GR activation induces expression of transcriptional regulators such as Hif3a and Zbtb16, which are essential in cytoskeletal organization and epithelial progenitor maturation during fetal lung development. [

94]

GC-GR signaling also promotes autophagy and surfactant synthesis by upregulating critical autophagy-related genes, including

Becn1,

Atg7, and

Lc3b. These genes facilitate lamellar body biogenesis, enabling the proper storage and secretion of surfactant proteins at birth. Recent studies have shown that the CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs)—a family of basic leucine-zipper transcription factors (notably C/EBPα and C/EBPβ)—act as key partners of GR, binding to CCAAT motifs in surfactant-gene promoters and coordinating terminal differentiation of alveolar type II cells. C/EBPs cooperate with GR to recruit steroid receptor coactivators SRC-1 and SRC-2, thereby amplifying transcriptional responses essential for surfactant production and alveolar maturation. [

95]

Moreover, SRC-1/2 double-deficient fetal mice exhibit reduced expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1), further limiting local GC activation and downstream gene transcription. These findings emphasize that optimal surfactant synthesis depends not only on GR activation but also on the integrity of its coactivator network, underscoring a multilayered regulatory system that prepares the fetal lung for extrauterine life

. [

95,

96]

4.3. Effects of GR Deficiency by Cell Type

Loss of mesenchymal GR causes severe lung immaturity, characterized by impaired fibroblast and epithelial differentiation and disruption of alveolar septation. [

59,

63] These findings demonstrate that mesenchymal GR signaling is the primary driver of lung morphogenesis, regulating epithelial–mesenchymal interactions that shape alveolar architecture. In contrast, epithelial-specific GR deletion increases epithelial proliferation and interferes with the maturation of alveolar type I (AT1) cells, while overall lung structure remains largely intact. [

59,

69] This indicates that epithelial GR primarily supports terminal epithelial differentiation rather than governing broader architectural patterning within the developing lung. Finally, endothelial-specific GR deletion produces minimal developmental abnormalities, suggesting that GR signaling within the pulmonary endothelium plays a

comparatively minor role during fetal maturation. [

59,

60]

4.4. Broader Developmental and Systemic Roles

Beyond the lung, GR signaling helps coordinate organ development and metabolic preparedness for postnatal life. Within the lung, GR regulates alveolar epithelial composition by promoting differentiation into AT1 cells, which are critical for efficient gas exchange. In GR-null mice, this differentiation is disrupted, leading to a higher proportion of AT2 cells and fewer AT1 cells, thereby compromising respiratory transition at birth. These findings highlight the central role of GR in establishing the cellular structure of the lung and overall readiness for life outside the womb.

As discussed in

Section 2.4 (“Evolutionary and Translational Implications”), understanding the developmental timing and tissue specificity of GRα signaling is essential for translating these mechanisms into safe and effective clinical practice. From a translational perspective, clinical management should emphasize gestationally appropriate timing and avoid unnecessary repeat dosing, linking antenatal steroid administration to coordinated neonatal follow-up of neurocognitive and respiratory outcomes. Future research should refine gestational windows of GRα sensitivity, establish clearer dose–response relationships along the lung–brain axis, and develop biomarkers that distinguish beneficial acceleration of maturation from maladaptive developmental programming. [

22,

23,

87,

89]

Developmental Implications

GR signaling functions as a master regulator of fetal lung development, integrating mesenchymal–epithelial communication, ECM remodeling, surfactant synthesis, and vascular coordination to ensure structural and functional readiness for air breathing. Disruption of this pathway leads to profound defects in lung architecture and gas-exchange capacity, compromising neonatal survival and underscoring GR’s indispensable role in fetal transition to extrauterine life. Collectively, these developmental functions illustrate how GRα operates as a unifying endocrine regulator that anticipates physiologic demands, synchronizes organ maturation, and establishes the foundation for lifelong respiratory resilience.

5. The Respiratory System: Complexity, Architecture, and Biofunctional Beauty

The respiratory system is an intricately organized, multicellular network in which epithelial, endothelial, immune, and stromal cells operate in precise spatial coordination to support air filtration, gas exchange, and host defense. A defining feature of this system is the near-universal expression of GRα, a nuclear receptor that adjusts gene expression in response to stress, inflammation, and metabolic cues. By integrating signals across cell lineages, GRα enables rapid adaptation to infection, hypoxia, and injury, positioning it as a central regulator of respiratory resilience and homeostasis.

This section outlines the structural and functional organization of the respiratory tract—spanning epithelial diversity, alveolo-capillary design, mucosal immunity, vascular and interstitial networks, respiratory musculature, and gas-exchange regulation—to establish the framework within which GRα operates. Situating GRα within this architectural landscape underscores its essential role as both a mediator of stress responses and a unifying integrator of respiratory physiology.

5.1. Anatomical and Functional Overview

Evolved for both survival and adaptation, the human lung is one of biology’s most exquisitely engineered systems—an intricately ordered, multicellular network of extraordinary scale and precision. It is composed of an estimated 40 to 50 billion cells, including more than 11 billion epithelial and over 20 billion endothelial cells, which together establish the structural and functional backbone of respiratory physiology. [

25,

97,

98] Across this cellular landscape, alveolar type I and II epithelial cells, specialized capillary endothelial subsets (aerocytes and gCap cells), ciliated and secretory airway cells, and diverse immune and stromal populations are organized in highly precise spatial networks that enable continuous air filtration, gas exchange, and host defense.

As reviewed in the next section, nearly every cell within this intricate system expresses the GRα. This nuclear receptor not only responds to systemic glucocorticoid signals but also serves as a central integrator of cellular homeostasis, modulating gene expression in response to stress, inflammation, and metabolic demand. Through coordinated, cross-compartment signaling among epithelial, endothelial, immune, and stromal compartments, GRα aligns respiratory function with systemic homeostasis, allowing rapid and efficient adaptation to infection, hypoxia, and injury. This widespread, lineage-spanning expression underscores GRα’s role as a unifying regulatory hub that connects cellular behavior to organism-level physiologic demands.

Together, these interconnected components provide the framework for understanding how GRα coordinates adaptive and protective responses across the diverse cell populations of the lung—a theme explored further in

Section 4.2. This architectural overview establishes the anatomical and functional context needed to understand GRα’s integrative role in maintaining respiratory stability across health and disease.

5.2. Structural-Functional Integration

The respiratory tract exhibits a finely tuned structural organization in which form and function are tightly interwoven to optimize air conduction and gas exchange. It is generally divided into the conducting zone—comprising the nasal passages, pharynx, larynx, trachea, and bronchi—and the respiratory zone, which includes the bronchioles and alveoli. [

99] The conducting tract primarily conditions inspired air by warming, humidifying, and filtering it, while the respiratory zone enables efficient gas exchange across a large alveolar surface lined with type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells. [

100,

101] These epithelial cells not only facilitate passive diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide but also contribute to host defense by secreting pulmonary surfactants, especially SP-A and SP-B, which lower alveolar surface tension and boost antimicrobial activity. [

72] Depending on lung inflation status, the total alveolar surface area ranges from approximately 70 to 100 square meters, providing a large interface for gas exchange. [

97]

The airway epithelium comprises ciliated, goblet, basal, and club cells, which collectively support mucociliary clearance, secrete protective mucins, and maintain epithelial barrier integrity. The mucociliary escalator functions through the coordinated activity of motile cilia and mucus layers to transport inhaled particles toward the oropharynx. MUC5AC and MUC5B, secreted by goblet and submucosal gland cells, respectively, create a biochemical trap that captures pathogens and promotes their removal. This first line of defense is further enhanced by antimicrobial peptides, collectins, and immunoglobulins, providing broad-spectrum innate immune protection. These epithelial and mucosal defenses are dynamically regulated by GRα signaling, which fine-tunes mucin production, strengthens tight-junction integrity, and calibrates cytokine responses to maintain a balanced immune environment. [

102,

103,

104]

Beneath the epithelial layer, the alveolo-capillary interface enables efficient gas exchange across a thin barrier composed of type I pneumocytes and pulmonary capillary endothelial cells. Recent research has shown that the capillary endothelium is not a uniform structure but consists of two main specialized endothelial subsets: aerocytes and general capillary (gCap) endothelial cells (Gillich et al., 2020; Schupp et al 2020). [

25,

105] Aerocytes, unique to the lung, are extremely thin with minimal cytoplasm, reducing the diffusion distance for oxygen and carbon dioxide and thereby optimizing gas exchange. They also support immune surveillance by facilitating leukocyte trafficking across the alveolar-capillary barrier during inflammation. [

25,

106]

In contrast, gCap cells are more abundant and play complementary roles in regulating vascular tone, mediating angiocrine signaling, and supporting endothelial repair. [

25,

27] These cells function as progenitors that aid in capillary regeneration after injury and communicate locally through paracrine signals with nearby epithelial and immune cells. Additionally, gCap cells release angiocrine factors that shape tissue responses and help maintain lung homeostasis, a role increasingly recognized in single-cell studies. [

98,

107] The functional compartmentalization between aerocytes and gCap cells highlights the complexity of the alveolar microvasculature and demonstrates how structural specialization supports both efficient gas exchange and adaptive immune responses. As discussed in the next section, these endothelial functions are further regulated by GRα signaling, which coordinates responses to environmental and inflammatory stress.

To further clarify the structure and function of the alveolo-capillary interface, researchers have developed organ-on-chip models and advanced 3D imaging platforms that accurately reproduce the biomechanical and cellular environment of the alveolus. These systems support co-culture of epithelial and endothelial cells, simulate cyclic breathing mechanics, and enable real-time visualization of responses to pathogens, mechanical forces, and therapeutic interventions. [

108,

109] Such technologies provide powerful insights into epithelial barrier integrity, immune-cell dynamics, and regenerative signaling within the alveolar niche, effectively bridging the gap between in vivo physiology and translational disease modeling.

5.3. Pulmonary Vasculature Architecture and Function

The pulmonary vasculature is a complex and extensive network of arteries, capillaries, and veins arranged in sequence, built to support efficient gas exchange and respond to changing ventilation-perfusion requirements. This high-compliance, low-resistance system allows significant increases in blood flow with minimal pressure fluctuations—especially important during physical activity or under hypoxic conditions. [

110,

111]

This extensive capillary network surrounds the alveoli, with each alveolus tightly connected to a dense web of capillaries, ensuring optimal efficiency in gas exchange. The total length of capillaries in the human lung is estimated to range from 2,746 km to 6,950 km, depending on the stereological assumptions. [

112] These vessels are very narrow—about 6–8 μm in diameter—requiring red blood cells to pass in a single file. This configuration increases the surface area of RBC–endothelium contact and optimizes oxygen and carbon dioxide diffusion by minimizing the diffusion distance and maximizing exposure time. [

25,

113]

As discussed in

Section 3.2, advanced imaging has revealed that the alveolar capillary network comprises specialized endothelial subsets, including aerocytes and gCap cells, which facilitate gas exchange, modulate vasomotor tone, and coordinate immune signaling. [

25,

27,

105] This structural specialization enables the lung to rapidly adapt to metabolic demands and inflammatory challenges. As detailed in Section 3.5, these processes are further regulated by GRα signaling, which maintains pulmonary vascular homeostasis.

5.4. Pulmonary Interstitium: The Lung’s Immuno-Structural Interface

The pulmonary interstitium, once viewed merely as connective scaffolding, is now recognized as a highly dynamic compartment that integrates mechanical support, immune regulation, fluid balance, and tissue repair. It occupies the space between the alveolar epithelium and capillary endothelium, extending into the peribronchial and perivascular regions, and forms a continuous network of extracellular matrix (ECM), interstitial fibroblasts, pericytes, immune cells, and lymphatics. This compartment significantly contributes to lung compliance and elasticity, enabling the parenchyma to deform during respiration while maintaining alveolar integrity.

Extracellular matrix (ECM) and fibroblast dynamics. The ECM—rich in elastin, collagen, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins—is produced and remodeled by interstitial fibroblasts in response to injury, mechanical stress, and cytokine signaling. [

114,

115,

116] This remodeling balances tensile strength with flexibility, enabling repetitive mechanical stretch without structural failure.

Pericytes, immune cells, and lymphatic vessels cooperate with fibroblasts to regulate immune signaling, interstitial fluid clearance, and tissue repair. [

117,

118,

119] By integrating mechanical cues with biochemical signaling, the ECM–fibroblast network maintains tissue stability while permitting adaptive remodeling under stress. Disruption of this regulatory balance promotes pathological fibrosis, edema, and impaired gas exchange. [

120]

Interstitial immune surveillance and immune quiescence. The lung interstitium serves as a critical immune surveillance zone, hosting resident memory T cells, interstitial macrophages (IMs), dendritic cells, and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). These immune cells detect pathogens and tissue injury while limiting inflammation that could damage alveolar structures. [

121,

122] Unlike alveolar immune cells, interstitial immune populations are strategically positioned to regulate inflammation without directly disrupting gas exchange. IMs, distinct from alveolar macrophages, are positioned along alveolar walls and vasculature, where they modulate immune tone through IL-10 and TGF-β production, supporting tissue homeostasis. [

119,

123,

124] This positioning allows IMs to function as sentinels that fine-tune inflammation at the epithelial–vascular interface, limiting collateral injury during immune activation.

Pulmonary lymphatics: fluid balance and immune regulation. The lymphatic network within the pulmonary interstitium is essential for lung fluid balance and immune surveillance. It provides continuous drainage of interstitial fluid, plasma proteins, immune cells, and macromolecules —preventing pulmonary edema and preserving lung compliance. [

118,

125,

126]

Beyond fluid homeostasis, pulmonary lymphatics actively regulate immunity by transporting antigens, dendritic cells, and immune mediators to regional lymph nodes, thereby initiating and shaping adaptive immune responses. [

127,

128]

Lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) are not passive conduits but active immunoregulatory cells. They release cytokines and chemokines, present antigens via MHC molecules, and regulate leukocyte migration through inhibitory molecules, such as PD-L1, which restrain T-cell activation and promote immune tolerance. [

129,

130,

131,

132]

For CD8⁺ T cells, LECs present peripheral tissue antigens (PTAs) without costimulation, inducing deletion or anergy via MHC-I and PD-L1 signaling. [

130,

131,

132] For CD4⁺ T cells, LECs function as antigen reservoirs, transferring antigens to dendritic cells that promote T-cell anergy or regulatory T-cell differentiation. [

133]

Microbial sensing and mechanical regulation. Emerging evidence indicates that LECs may respond to signals from the lung microbiota, potentially linking lymphatic function to host-microbe interactions and immune adaptation. Although direct lung-specific data remain limited, LEC expression of pattern-recognition receptors (e.g., TLRs) supports this regulatory potential. [

134,

135]

LECs are sensitive to mechanical cues such as stretch and shear stress, which may regulate lymphangiogenesis and immune signaling under physiological and during mechanical ventilation. Lymphatic remodeling occurs during chronic inflammation, altering drainage capacity and immune regulation. During neonatal transition, pulmonary lymphatics play a vital role in clearing fetal lung fluid, enabling effective air breathing. [

136,

137] These insights position pulmonary lymphatics as a potentially modifiable therapeutic target across acute and chronic lung diseases.

Disruption of lymphatic drainage or LEC function leads to fluid retention, chronic inflammation, and disease progression in ARDS, COPD, and pulmonary fibrosis—highlighting pulmonary lymphatics as a modifiable therapeutic target across acute and chronic lung disease.

Stromal–immune crosstalk and GRα regulation. Stromal–immune interactions within the lung interstitium are tightly regulated by paracrine signaling from fibroblasts, epithelial cells, vascular endothelium, and immune populations. Stromal cells secrete chemokines (e.g., CCL2, CXCL10), cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-1β), and ECM components that shape immune recruitment, activation, and differentiation. [

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143] Immune cells reciprocally influence stromal phenotype and function, creating feedback loops that calibrate inflammation and tissue repair. [

144,

145] This bidirectional signaling ensures immune responsiveness without destabilizing lung architecture.

Glucocorticoid receptor alpha (GRα)

, as reviewed in section 5, plays a central role in modulating cytokine production, immune cell recruitment, and tissue repair dynamics. While lung-specific stromal studies remain limited, evidence from non-pulmonary models demonstrates that stromal GRα is essential for glucocorticoid-mediated anti-inflammatory responses. In arthritis models, deletion of GRα in fibroblast-like synoviocytes abolished glucocorticoid efficacy despite intact GRα in immune cells—highlighting the dominant regulatory role of stromal GR. [

146] These findings strongly suggest that similar GRα-dependent stromal–immune mechanisms operate within the pulmonary interstitium. In this setting, GRα signaling regulates fibroblast phenotype, ECM dynamics, immune quiescence, and cytokine feedback—particularly by modulating IL-6 family cytokines and TGF-β signaling. [

81,

139]

Through these integrated actions, stromal GRα preserves lung architecture under stress, promotes inflammation resolution, and prevents maladaptive remodeling and fibrosis—positioning it as a central regulator of interstitial homeostasis and a promising therapeutic target in both acute and chronic lung disease. [

73,

82,

147]

5.5. Immune and Microbial Surveillance

Lung immunity is orchestrated by a complex network of epithelial cells, immune cells, and the resident microbiome that together maintain homeostasis at the air–tissue interface.Epithelial cells act not only as physical barriers but also as active immune sentinels, detecting pathogens through pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) and initiating antimicrobial and regulatory responses. They secrete cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides that recruit and instruct resident and circulating immune cells—such as alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, and T lymphocytes—and thereby coordinate innate and adaptive immune defenses. [

148,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153,

154,

155]

This epithelial–immune crosstalk is bidirectional: immune cells, in turn, send feedback signals that influence epithelial phenotype, barrier integrity, and inflammatory resolution. Depending on the context, these exchanges promote either immune tolerance or chronic inflammation. [

153,

156,

157] By regulating both activation and resolution programs, epithelial cells help maintain barrier stability and prevent immune-mediated tissue damage. [

151,

152]

The lung microbiome—a dynamic community of commensal microorganisms—adds a third regulatory layer that modulates immune tone, maintains tolerance, and enhances resistance to pathogens. [

148,

158] Microbial metabolites and cell-wall components interact with epithelial and immune receptors to calibrate inflammatory thresholds and sustain mucosal equilibrium. When this microbial balance is disturbed—by antibiotics, infection, or environmental stressors—immune signaling becomes dysregulated, increasing susceptibility to infection and chronic inflammatory lung diseases. [

159,

160,

161]

Together, this tripartite surveillance system—epithelial signaling, immune activation, and microbial modulation—forms the foundation of respiratory immune homeostasis. Disruption of any single component—or of their coordination—can shift the system from balanced immunity to pathological inflammation or impaired defense. Understanding this integrated framework is essential for developing therapeutic strategies that restore tolerance, resolve inflammation, and strengthen mucosal defenses. [

148,

156,

158]

5.6. Respiratory Musculature and Mechanics

Breathing is driven by the rhythmic contraction of the primary and accessory respiratory muscles, which work together to create the pressure gradients needed for air movement. Under resting conditions, quiet breathing is maintained by the coordinated activity of the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles. In contrast, the accessory muscles—such as the sternocleidomastoid and scalene—are recruited during increased ventilatory demand, including physical exertion, speech, or respiratory distress. [

162,

163,

164] These muscle groups contain a high proportion of oxidative, fatigue-resistant fibers—especially in the diaphragm—allowing them to contract continuously throughout life. However, this endurance comes with a cost: prolonged metabolic stress, systemic inflammation, or increased ventilatory demand can lead to respiratory-muscle fatigue and weakness, which may contribute to respiratory failure in critical illness. [

165]

Neural regulation of breathing is orchestrated by a distributed brainstem network that integrates chemical and mechanical feedback. Central chemoreceptors located near the ventrolateral medulla detect elevations in arterial CO₂ (PCO₂) and accompanying reductions in pH, thereby increasing respiratory motor output to restore gas-exchange homeostasis. [

166] The retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) serves as a key chemosensory hub within this network, interacting with the pre-Bötzinger complex, which generates the inspiratory rhythm, and pontine-medullary centers that modulate phase transitions between inspiration and expiration. The nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) integrates afferent input from peripheral chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors, relaying these signals to spinal motor neurons that drive the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, ensuring coordinated and adaptive respiratory effort. [

167]

This finely tuned neural control system ensures respiratory muscles respond effectively to changing physiological demands. However, its efficiency can be compromised in pathological conditions where increased mechanical load, inflammation, or disrupted neural signaling progressively reduce muscle performance and coordination. In diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and neuromuscular disorders, altered motor recruitment patterns, increased load, and reduced endurance capacity weaken respiratory muscle function, leading to impaired ventilation and dyspnea. [

168]

As described in later sections, GRα signaling opposes these maladaptive processes by maintaining mitochondrial bioenergetics, redox balance, and calcium homeostasis in respiratory and accessory muscles. By sustaining ATP generation, limiting oxidative injury, and stabilizing excitation–contraction coupling, GRα enhances contractile endurance and supports adaptive responses to heightened metabolic and mechanical stress.

Beyond its cell-specific roles summarized in

Table 2, GRα orchestrates integrated signaling networks that link the airway, vascular, mesenchymal, immune, and muscular compartments of the lung into a unified regulatory system. Through these interconnected pathways, GRα coordinates cellular metabolism, inflammatory control, and structural maintenance to preserve respiratory stability under stress.

Table 3 (Functional Integration of GRα Signaling Across Pulmonary Compartments) outlines the main cross-compartmental actions and key molecular mediators through which GRα maintains pulmonary homeostasis, supports repair, and promotes adaptive resilience across the respiratory system.

5.7. Gas Exchange and Developmental Adaptation

Efficient gas exchange depends on a large alveolar surface area, an exceptionally thin diffusion barrier, and accurate ventilation–perfusion (V/Q) matching, all maintained through continuous alveolar and microvascular development. The processes of alveolarization and capillary expansion extend well into postnatal life, improving both gas exchange efficiency and the lung’s capacity for structural repair. [97,169] Oxygen and carbon dioxide passively move across the alveolar–capillary interface, where red blood cells serve as efficient carriers for gas transport. The system's effectiveness depends on precise ventilation–perfusion (V/Q) matching, which is primarily regulated by hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV), directing blood flow away from poorly ventilated regions toward those with optimal aeration. [170] This adaptive vasomotor response preserves arterial oxygenation during regional lung dysfunction and exemplifies the finely tuned coupling between ventilation, perfusion, and microvascular signaling

Functional Integration of Respiratory Homeostasis

The respiratory system functions as a complex and highly integrated network that coordinates airway architecture, vascular dynamics, immune surveillance, and microbial symbiosis. Its impressive ability to detect, respond, and adapt to environmental and physiological challenges reflects both its evolutionary development and innate resilience. Disruption of any structural or regulatory component—epithelial, immune, vascular, or muscular—can destabilize the entire system, emphasizing its delicate balance and essential integrative function.

Many of these adaptive and homeostatic processes are regulated by the endocrine system, especially glucocorticoids acting through the GRα. GC-GRα signaling influences key respiratory functions—surfactant production, immune response, vascular tone, epithelial repair, and interstitial remodeling—linking molecular signals with tissue-level adaptation. By coordinating these processes across diverse cell populations, GRα provides a unifying regulatory framework that supports structural integrity, metabolic efficiency, and immune balance throughout the respiratory tract.

The broad distribution and cell-specific actions of GRα throughout the respiratory tract are summarized in

Table 2, which illustrates how this receptor coordinates structural integrity, immune balance, and functional homeostasis across diverse pulmonary cell types. Recognizing this integrated regulatory system is essential for understanding how the respiratory tract adapts to stress, inflammation, and injury—and for designing targeted therapeutic strategies that restore physiological balance and preserve lung function.

6. GC-GRα Signaling Regulation of Lung Function: Integrating Gas Exchange, Barrier Integrity, Fluid Clearance, and Inflammatory Control

Having established the structural and cellular organization of the respiratory system, this section now examines how glucocorticoid (GC)–glucocorticoid receptor alpha (GRα) signaling governs pulmonary function through coordinated molecular and physiological mechanisms. GRα acts as a master transcriptional regulator of respiratory homeostasis, coordinating a variety of processes essential for maintaining efficient lung performance throughout life. Beyond its developmental role in lung maturation, GRα continues to regulate airway reactivity, surfactant synthesis, immune balance, vascular coupling, epithelial integrity, and alveolar fluid clearance. Together, these interconnected actions work to preserve gas exchange efficiency, structural integrity, and adaptability in response to inflammation, oxidative stress, or environmental challenges. This section explores how GRα signaling connects these physiological subsystems, integrating insights from developmental biology, cellular signaling, and translational research.

6.1. Glucocorticoid Receptor Regulation of Tracheobronchial Tree and Airway Tone Regulation

The GC-GRα signaling pathway is crucial for controlling airway smooth muscle (ASM) tone through its combined anti-inflammatory, bronchodilatory, and antiproliferative effects—mechanisms that explain how glucocorticoids work in asthma. When activated, GRα reduces ASM contraction by lowering intracellular calcium, decreasing muscarinic and histamine receptor activity, and inhibiting the inflammatory induction of bradykinin B2 receptors

. [

76,

171] Concurrently, GRα promotes smooth muscle relaxation by increasing β₂-adrenoceptor expression and stimulating Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase activity, thereby improving membrane repolarization and aiding airway dilation. [

77,

78]

To counter airway hyperresponsiveness, GRα induces MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP-1/DUSP1), which deactivates pro-contractile MAPK signaling and suppresses ASM proliferation and hypertrophy through KLF15- and PLCD1–dependent transcriptional regulation. [

78,

172,

173] Additionally, GRα limits cytokine and chemokine production—such as IL-6 and CXCL8—in the airway wall, thereby restoring immune balance and reducing local inflammation. Emerging evidence indicates that airway smooth muscle cells can produce local glucocorticoids and dynamically regulate GR expression, potentially contributing to sustained airway homeostasis and steroid responsiveness. [

174] Together, these integrated genomic and non-genomic mechanisms explain the therapeutic effectiveness of glucocorticoids in asthma—keeping the airways open, reducing hyperresponsiveness, and lowering disease severity.

6.2. Glucocorticoid Receptor Regulation of Surfactant Production and Airspace Patency

The GRα is indispensable for preparing the lung for air breathing at birth. It provides gene-specific regulation of pulmonary surfactant homeostasis, especially during late gestation and the early postnatal transition to air breathing. Inside alveolar type II (AT2) epithelial cells, GRα activates coordinated transcriptional networks that promote the production of surfactant proteins (SPs) and lipid transporters, which are needed for alveolar stability and optimal lung compliance after delivery. One of the most critical GRα targets, the ATP-binding cassette transporter A3 (ABCA3), is essential for the formation of lamellar bodies—specialized intracellular organelles that package, store, and secrete surfactant lipids and proteins. Through direct interaction with a glucocorticoid-response element (GRE) in the ABCA3 promoter, GRα upregulates ABCA3 mRNA and protein expression, thereby increasing intracellular surfactant reserves in preparation for postnatal air breathing. This ABCA3–surfactant module is shown in

Figure 2. During late gestation, ABCA3 expression increases significantly, ensuring sufficient surfactant production and alveolar patency during the transition from liquid to gas respiration. [

175]

Surfactant proteins B (SP-B) and C (SP-C), which lower alveolar surface tension and prevent collapse at end-expiration, are also induced by glucocorticoids through GRα-dependent transcriptional activation. SP-B expression increases quickly and independently of new protein synthesis, indicating a primary, direct genomic effect of GRα. Conversely, SP-C induction is delayed and relies on secondary GR-responsive cofactors that facilitate epithelial differentiation and maturation. [

63,

176,

177] Beyond transcriptional control, GRα also enhances SP-B mRNA stability via 3′-UTR–dependent mechanisms, thereby sustaining surfactant protein availability during the critical perinatal window. [

178]

Surfactant protein A (SP-A) exhibits a distinctive biphasic regulatory pattern—initially increasing, then decreasing after prolonged glucocorticoid exposure. This adaptive transcriptional switch is regulated by GRα-dependent recruitment of histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) and associated local chromatin condensation, which together fine-tune SP-A expression and prevent excessive surfactant buildup in the alveolar space. [

179,

180,

181]

Recent transcriptomic studies confirm that antenatal glucocorticoid signaling via GRα orchestrates a broad developmental program in the fetal lung—linking surfactant production with lipid metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, and antioxidant defenses. This network prepares the lung for the sudden oxidative and mechanical challenges of extrauterine life. [

63,

182,

183] Through these precisely timed GRα-regulated processes, the fetal lung achieves the structural, metabolic, and functional maturity needed for alveolar expansion, effective gas exchange, and continued postnatal breathing. Clinically, this GRα-driven cascade explains the well-known effectiveness of antenatal corticosteroid therapy, which speeds up fetal lung development and greatly lowers the risk and severity of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS).

6.3. Glucocorticoid Receptor Regulation of Alveolar-Capillary Barrier Integrity and Interstitial Homeostasis

The alveolar–capillary barrier maintains selective permeability between airspaces and the circulation, ensuring efficient gas exchange while preventing fluid transudation. In acute lung injury (ALI) and ARDS, disruption of this barrier leads to plasma leakage, interstitial and alveolar edema, and severe hypoxemia. GC-GRα signaling acts as a central homeostatic defense system that preserves barrier integrity by reinforcing junctional complexes, reducing cytoskeletal tension, and attenuating inflammation.

Through both genomic and non-genomic actions, GRα stabilizes tight junctions, modulates actomyosin contractility, and reduces inflammatory injury. In experimental models, dexamethasone decreases myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) and myosin light-chain 2 (MLC2) phosphorylation while increasing zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and claudin-8 expression, thereby enhancing epithelial cohesion and limiting tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)–induced permeability. [

184,

185,

186] These molecular effects restore barrier selectivity and decrease paracellular fluid leakage under inflammatory conditions. [

184,

185]

Beyond barrier stabilization, GRα promotes epithelial repair and interstitial homeostasis. By interacting with developmental transcription factors such as signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), GRα facilitates alveolar progenitor differentiation and epithelial regeneration following injury. [

90] Loss of epithelial GRα impairs junctional structure, enhances cytokine expression, and slows recovery, confirming its dual role in maintaining barrier integrity and orchestrating tissue repair. [

187,

188]

During fetal development, GRα guides the maturation of the alveolar–capillary interface, coordinating epithelial, endothelial, and mesenchymal differentiation. GRα deficiency leads to thickened alveolar septa, decreased lung compliance, and impaired gas exchange, while antenatal corticosteroid therapy activates GR-responsive transcriptional networks that assemble junctional proteins and extracellular matrix components vital for postnatal lung. [

90,

185,

189]

Collectively, these findings identify GRα as a key regulator of alveolar integrity and interstitial homeostasis. By coordinating structural, inflammatory, and reparative processes, GRα maintains fluid balance and prevents pulmonary edema—mechanisms that explain the well-known clinical effectiveness of corticosteroid therapy in both acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and preterm lung maturation.

6.4. Glucocorticoid Receptor Regulation of Pulmonary Lymphatics

Glucocorticoid receptors, especially GRα, are essential regulators of lung lymphatic and immune functions, functioning at the intersection of hormonal signaling, circadian rhythms, and immune cell trafficking. In T lymphocytes and other immune cells, GR activation influences their development and effector functions, ultimately affecting lung immune responses. [

83] A central anti-inflammatory mechanism involves GR-mediated suppression of IL-1-induced IL-6 production in lung fibroblasts, achieved through both transcriptional repression and post-transcriptional regulation, thereby reducing cytokine-driven inflammation. [

190]

Beyond direct cytokine regulation, GRs influence the spatial distribution of immune cells through circadian mechanisms. GRα signaling increases interleukin-7 receptor (IL-7R) and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) expression in T cells, promoting their rhythmic migration between the lungs, blood, and lymphoid organs, thereby supporting adaptive immunity in synchrony with the body’s diurnal cycle. [

84] In pulmonary epithelial cells, GR binding to the CXCL5 gene exhibits rhythmicity, regulating chemokine production and driving time-of-day-specific neutrophil recruitment. These circadian and endocrine mechanisms work together to coordinate pulmonary immunity, linking GR activation to the local molecular clock that controls leukocyte trafficking and the timing of inflammation. [

191]

Recent transcriptomic and mechanistic studies further demonstrate that GRα signaling regulates pulmonary vascular and lymphatic permeability through crosstalk with Wnt/β-catenin and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathways, enhancing endothelial stability and limiting inflammatory leak. [

73,

192] The function of GRα is fine-tuned by post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and by co-regulatory proteins, including Merm1 (Mediator of ERBB2-driven cell motility 1), which amplify GRα transcriptional activity and determine steroid responsiveness within inflamed tissues. [

193,

194] Disruption of these co-regulators—or of circadian integrity—can weaken GRα activity, leading to glucocorticoid resistance and impaired inflammation resolution. [

195]

At the protein-interaction level, GRα binds with caveolin-1 in pulmonary tissue to regulate the transcription of anti-inflammatory genes; however, the absence of caveolin-1 does not eliminate GRα-mediated inflammatory suppression in vivo, indicating that specific GRα cofactor interactions are modulatory rather than strictly indispensable. [

196]

Taken together, GRα signaling coordinates multiple layers of pulmonary immunity and lymphatic balance by regulating cytokine production, immune cell localization, vascular tone, and circadian rhythms. These integrated actions form the physiological basis for the strong anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of glucocorticoids in respiratory diseases, while also explaining how disruptions in GRα co-regulators or circadian rhythms can diminish therapeutic benefits.

6.5. Glucocorticoid Receptor Regulation of Alveolar Immune Responses and Inflammatory Signaling

The alveolar compartment acts as a primary immunological interface, continuously exposed to airborne pathogens, allergens, and environmental stressors. Maintaining functional homeostasis at this interface requires precise coordination between host defense and inflammation control. GRα signaling serves as a central regulator of this balance, integrating genomic and non-genomic programs that suppress excessive inflammation, support epithelial and immune-cell repair, and limit collateral tissue injury. [

55]

At the core of alveolar inflammatory regulation are two transcription factors—nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1)—which drive expression of numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Their activation in alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages promotes production of IL-8, IL-1β, and TNF-α, leading to neutrophil recruitment and barrier dysfunction. [

197,

198] GRα counteracts these pathways through multiple complementary mechanisms. It directly tethers to NF-κB and AP-1, interferes with their transcriptional activity, and induces inhibitory phosphatases such as dual-specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1). GRα also activates anti-inflammatory mediators, including glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) and IL-10, converging on suppression of cytokine transcription and promotion of inflammatory resolution. [

199,

200,

201] This layered repression allows inflammation to be restrained without abolishing essential host-defense programs.

Macrophage polarization and immune resolution. In alveolar macrophages, NF-κB activation promotes polarization toward a classically activated, pro-inflammatory (M1-like) phenotype characterized by high cytokine output and tissue injury. GRα signaling opposes this shift and facilitates transition toward an M2-like reparative phenotype. By repressing NF-κB and inhibiting p38 MAPK activity, GRα induces IL-10 expression and promotes macrophage programs associated with tissue repair, efferocytosis, and the resolution of inflammation. [

202,

203] This phenotypic reprogramming restores immune balance while limiting excessive fibrosis and preserving alveolar architecture.

Recent transcriptomic studies further demonstrate that GR activation in alveolar macrophages induces the release of soluble Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), which functions as a decoy receptor to dampen inflammatory signaling. [

204] This mechanism provides an additional layer of innate immune modulation that restrains excessive pattern-recognition receptor activation.

Epithelial–immune integration and GRα signaling fidelity. In alveolar epithelial cells, GRα signaling is modulated by extracellular stress-response pathways. Extracellular heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) acting through TLR4, enhances GRα expression and signaling capacity. This interaction amplifies anti-inflammatory and antioxidant programs during epithelial stress.

Context-dependent specificity of GRα signaling is further achieved through receptor phosphorylation and interaction with co-regulatory proteins. GRα partners with Mediator of ERK-activated MAPK1-interacting protein 1 (Merm1), GR-interacting protein 1 (GRIP1), and transcriptional intermediary factor 2 (TIF2), which refine transcriptional accuracy and influence glucocorticoid sensitivity. These co-regulators help determine whether GRα signaling promotes resolution versus resistance in inflamed tissues.

Barrier repair and immune containment. In addition to transcriptional immune regulation, GRα directly supports epithelial barrier repair following inflammatory injury. By reducing myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) activity and phosphorylation of myosin light chain 2 (MLC2), while increasing expression of tight-junction proteins such as zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and claudin-8, GRα restores junctional integrity and limits paracellular fluid leak. [

184,

186] These structural effects complement GRα’s anti-inflammatory actions, coupling immune resolution with physical barrier restoration. By integrating control of inflammation, macrophage phenotype, epithelial integrity, and transcriptional fidelity, GRα maintains alveolar immune balance and prevents progression from adaptive inflammation to tissue-damaging pathology.

Clinical Relevance and Integrative Perspective