1. Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) is characterized by abnormal cell proliferation resulting from disruptions in apoptosis and senescence mechanisms [6,19,23,27]. CC pathogenesis is influenced by viral infections, immune and hormonal imbalances, which collectively contribute to the deregulation of genetic and epigenetic process [4,5,6]. Specifically, persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 along with the overexpression of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 are recognized as key drivers of malignant transformation [2,3,4,5,19,20,23]. CC disproportionately affects young women and remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality in low- and middle- income countries [2,4,5,6,14,19]. HPV vaccination programs are preventive and do not eliminate the virus once infection has occurred. Initial management of CC typically involves hysterectomy and lymph node dissection, often combined with radiation therapy, with or without adjunctive chemotherapy [19,23,24]. In advanced stages, treatment generally includes external beam radiotherapy, cisplatin-based chemotherapy, and brachytherapy [19,23,27]. Despite their widespread use, these conventional therapies present several limitations, including: (a) adverse effects such as drug resistance and gastrointestinal, neurological, or cardiac toxicity; (b) limited efficacy of anticancer agents; (c) poor tumor specificity; (d) high treatment costs; (e) risk of disease recurrence; and (f) reduced patient quality of life [3,23,24]. Given these limitations, natural compounds are increasingly being explored as adjuvant therapies in the treatment of CC [7,18,21,25,26].

Early investigations have indicated that natural adjuvants may include secondary metabolites or bioactive compounds with antiproliferative, antitumor, and anticancer properties, while exhibiting minimal cytotoxicity toward non-cancerous cells [27]. These compounds can induce apoptosis and suppress key processes involved in cancer progression, such as invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis in CC cells [4]. Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) a tropical fruit from the Sapindaceae family, is notable for its high concentration of secondary metabolites, particularly polyphenols. Several studies have highlighted its anticancer potential [17]. For example, in human osteosarcoma cells, rambutan extract induced apoptosis, caused G2/M phase cell cycle arrest, upregulated caspase-3 and -9, and downregulated Bcl-2 and Erk1/2 expression [17]. Recent evidence has shown that a methanolic extract from the fruit’s endocarp enhanced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells [15]. Moreover, rambutan peel extract reduced the cell viability in various cell lines, including non-cancerous (L929, Vero) and cancer cell lines (MCF-7) as showed by their LC50 values [12]. Despite these promising findings, limited research has explored the effects of rambutan on HeLa cell line.

This study aimed to evaluate the cytotoxic and molecular effects of Rambutan peel polyphenolic extract (RPPE) on HeLa cervical cancer cells and normal human dermal fibroblasts HDFa. Results revealed that rambutan exerted a concentration-dependent cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells, with the highest activity observed at 175 μg/mL. At this concentration, rambutan upregulated the expression of pro-apoptotic markers Bax and p53, while downregulating the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 gene. These findings suggest that rambutan peel extracts may exert selective cytotoxic effects in cervical cancer cells, potentially through the modulation of apoptotic pathways. However, further molecular characterization is required to validate its therapeutic relevance in CC.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Committee on Education, Research, Training and Ethics of the General Hospital Saltillo.

Cell Culture

HeLa cervical cancer cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (all Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Adult human primary dermal fibroblasts (HDFa) cell line was resuspended in Fibroblast Basal Medium (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) containing Fibroblast Growth Kit–Serum-Free and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (all ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Both cell lines were incubated at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 using Forma Direct Heat CO2 Incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell Viability Assay

HeLa and HDFa were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 15x103 cells per well and cultured for 24 h. RPPE extract was dissolved in sterile medium by sonication for 15 min. The cells medium was treated with this RPPE solution at concentrations of 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL and incubated at 37oC and 5% CO2 for 24, 48, and 72 h. RPPE-treated wells were compared against control blank wells where no RPPE extract were added. After incubation, cell viability was assessed using the methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay. 10 μL of MTT reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added to each well including controls (final concentration 0.5 mg/mL), followed by incubation at 37ºC for 4 h. Subsequently, 50 μL of absolute DMSO were added to solubilize the formazan crystals, and plates were incubated for an additional 10 min at 37ºC. Optical density (OD) was measured value at 570 nm using a Smart Reader 96 microplate absorbance reader (Accuris Instruments, Edison, NJ, USA). Following a randomized experimental design, all experiments were performed in triplicate [17].

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

HeLa and HDFa cells (15x104 cells per well) were seeded in 24-well plates and cultured for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37ºC. Cells were then treated with 200 μg/mL of RPPE for an additional 24 h. Untreated cells served as controls. After incubation, total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. RNA concentration and purity were determined by measuring absorbance at 260 nm and calculating the 260/280 ratio, using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Samples with a 260/280 ratio greater than 1.60 were used for subsequent analysis. RNA was stored at −80ºC until use.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from total RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the reaction mixture contained 2 µL of 10X RT Buffer, 0.8 µL of dNTPs Mix (100 mM), 2 µL of 10X random primers, 1 µL multiScribeTM reverse transcriptase, 1 µg of RNA, and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 μL. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 25ºC for 10 min, 37ºC for 120 min, 85ºC for 5 min, followed by a final hold at 4ºC. Synthesized cDNA was stored at −20ºC until further use.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

The qRT-PCR was performed using a StepOnePlusTM Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA) in 96-well PCR plates. Synthesized cDNA (20 ng per reaction) was used as template in a final volume of 20 μL, containing 1X SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA), and 500 nM gene-specific primers. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing at 60 °C for 1 min. A melt-curve analysis was performed at the end of each run to verify amplification specificity. All samples were analyzed in duplicate, and each experiment included two no-template controls to detect any template contamination. Relative mRNA expression levels of BCL2, P53, AKT, BAX, P21, and GAPDH were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical Analysis

All variables were tested in triplicate following a randomized experimental design. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences between control and treated groups were assessed using Student’s T-test. Differences were statistically significant for values of P<0.05.

3. Results

RPPE Reduces Viability in HeLa But Not in Normal Fibroblasts

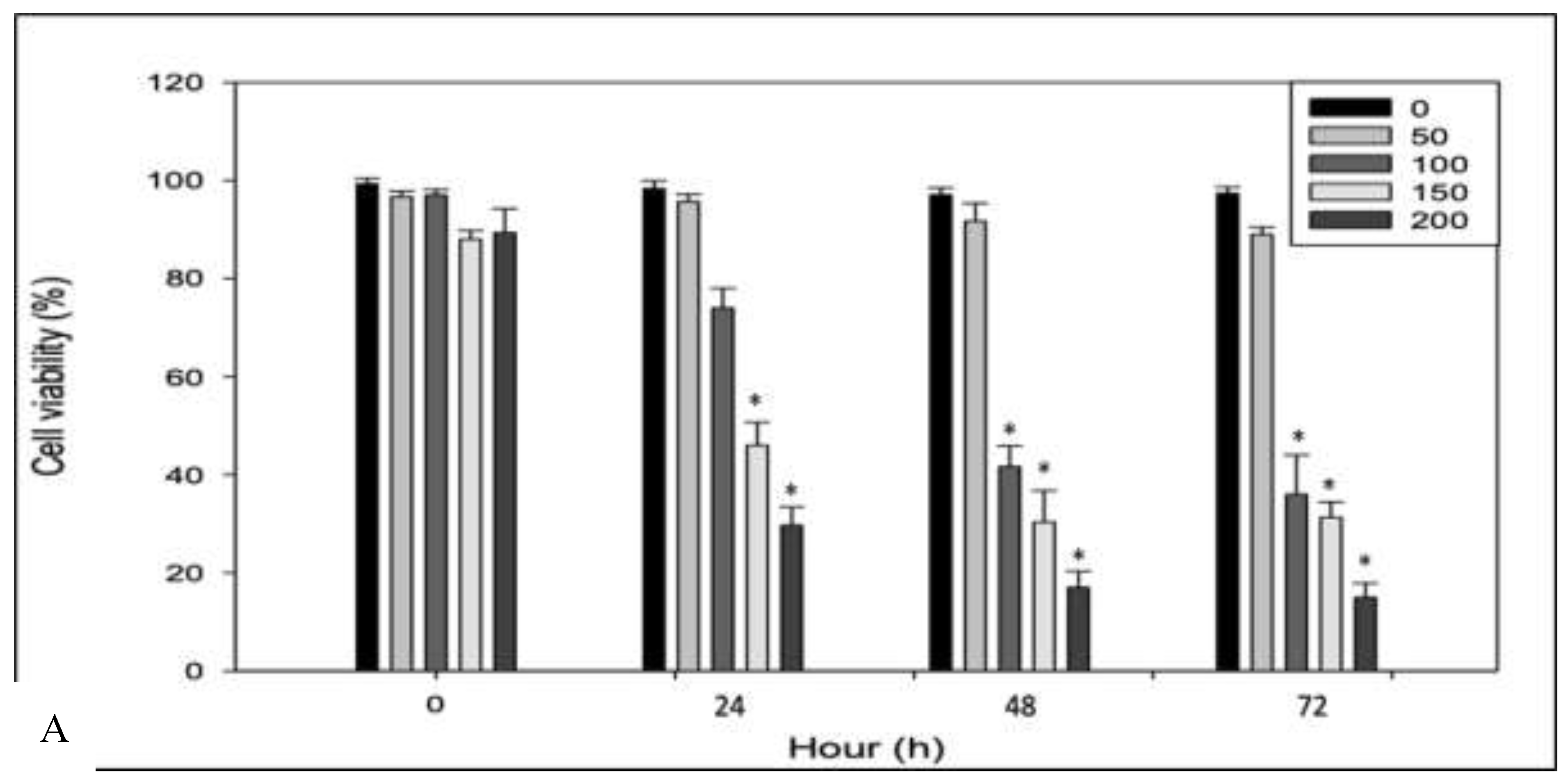

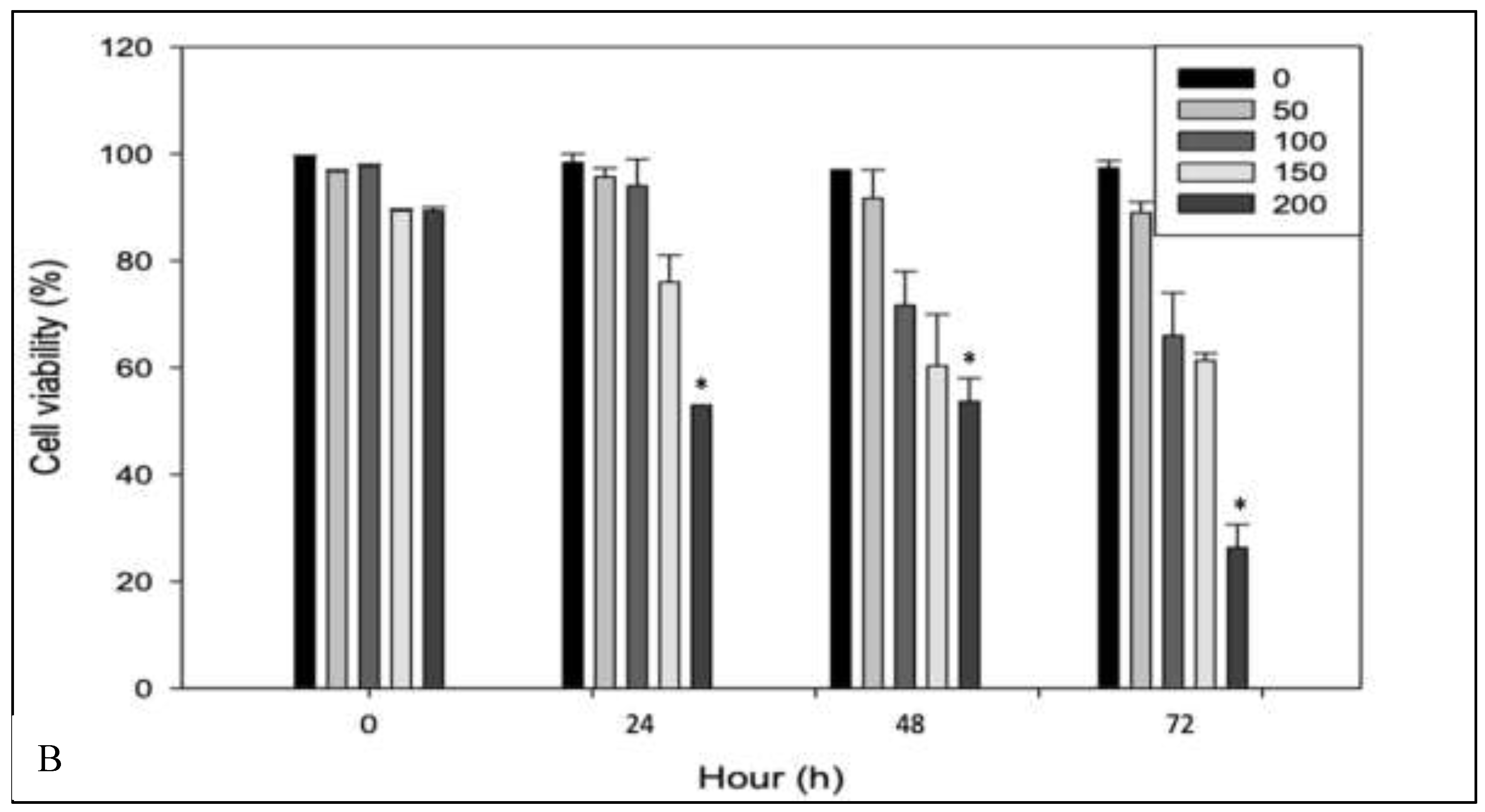

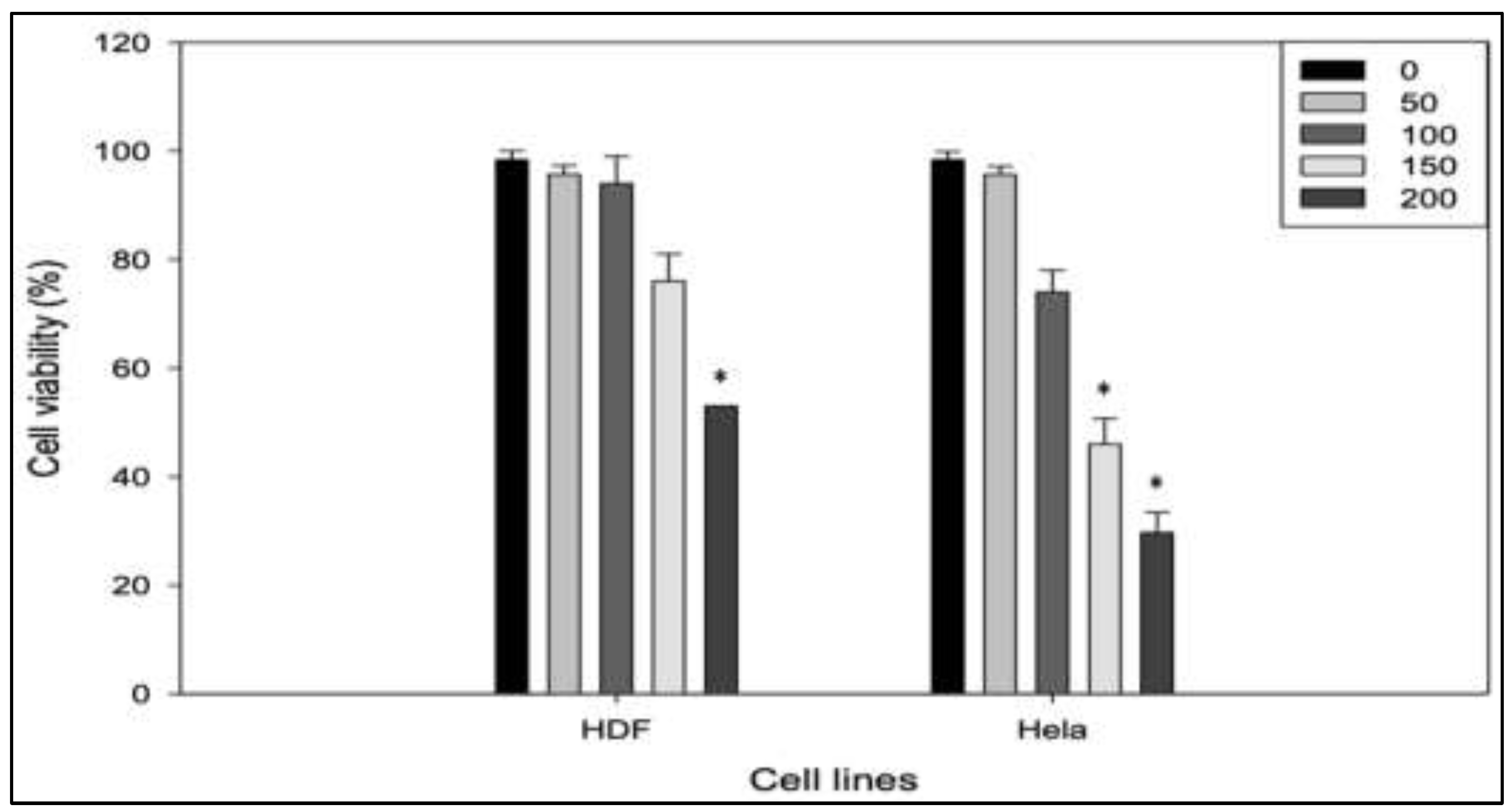

An initial assessment was conducted to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of RPPE on HeLa cancer cells and to determine its selectivity relative to normal human dermal fibroblasts (HDFa). Both cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of RPPE (50, 100, 150, and 200 µg/mL) and incubated for 24, 48, and 72 h.

Figure 1A shows that cell viability at zero remains close to 100% across all concentrations in HeLa and HDFa cell types, indicating that RPPE does not exert immediate viability effects prior to incubation. In HeLa cells, treatment with lower concentrations (50 and 100 µg/mL) for 24 h resulted in minimal viability reduction. However, significant viability reductions were observed at higher concentrations (150 and 200 µg/mL), decreasing to approximately 60% and 40%, respectively. These effects became more pronounced over time, with HeLa cell viability decreasing to approximately 30% and 20% at higher RPPE concentrations after 48 h, respectively. At 72 h, viability further declined to below 20% for both concentrations, confirming a sustained and concentration-dependent cytotoxic response. In contrast, HDFa cells exhibited markedly greater resistance to RPPE. As shown in

Figure 1B, HDFa viability remained near 100% at all concentrations after 24 h. Treatment with 150 µg/mL resulted in a modest reduction (~80%). After 48 h, cell viability decreased to approximately 65% and 55% at higher concentrations 150 and 200 µg/mL, respectively. By 72 h, significant HDFa cytotoxicity was observed only at 200 µg/mL, while viability remained high (~85–90%) at lower concentrations. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that RPPE selectively induces cytotoxicity in HeLa cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner, while largely sparing normal fibroblasts.

Morphological Changes

HeLa cancer cells treated with different concentrations of RPPE for 24h exhibited distinct morphological alterations, including reduced cell volume and changes in cellular architecture (

Figure 2). In the control group (

Figure 3A)

, untreated HeLa cells displayed a typical epithelial-like morphology, characterized by elongated, spindle-shaped cells and forming well-adhered monolayers. Cell membranes appeared intact, with minimal cellular debris, indicating a healthy and proliferative state. Following treatment with low to moderate concentrations of RPPE (100 and 150 µg/mL in

Figure 3B and 3C, respectively)

, notable morphological changes became evident. Treated cells progressively lost adherence, adopted a rounded morphology, and displayed signs of cytoplasmic condensation. Membrane blebbing and the presence of cellular debris were also observed, consistent with early apoptosis events. At higher RPPE concentrations (200 µg/mL,

Figure 3D), most cells appeared rounded, detached, and suspended, with pronounced membrane damage and extensive fragmentation. The widespread loss of adherence and cellular integrity strongly suggests progression to late-stage apoptosis or necrosis

. Overall, these morphological observations align with the cytotoxic effects quantified in the viability assays and support the conclusion that RPPE induces dose-dependent apoptotic cell death in HeLa cancer cells (

Figure 3A-D).

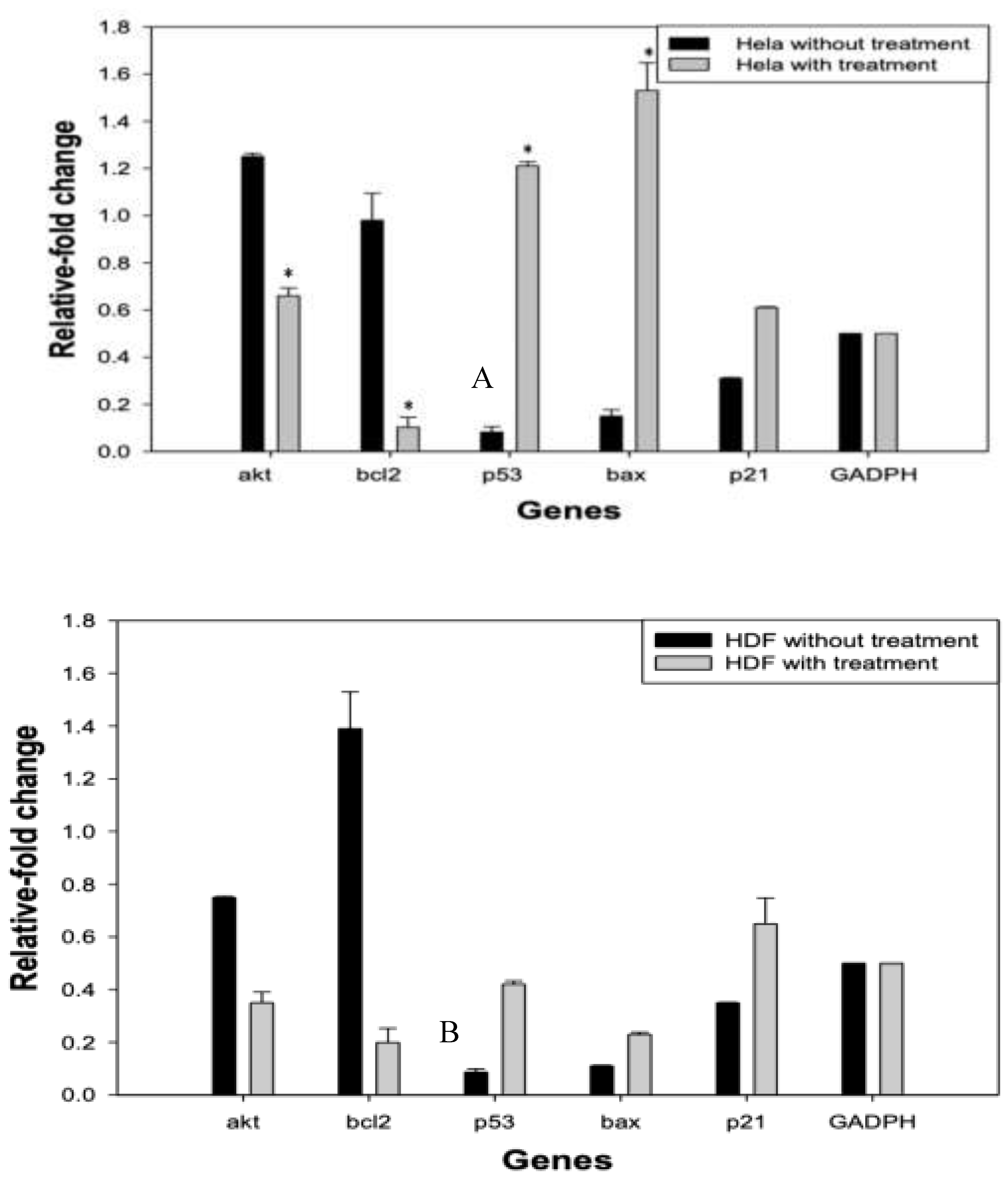

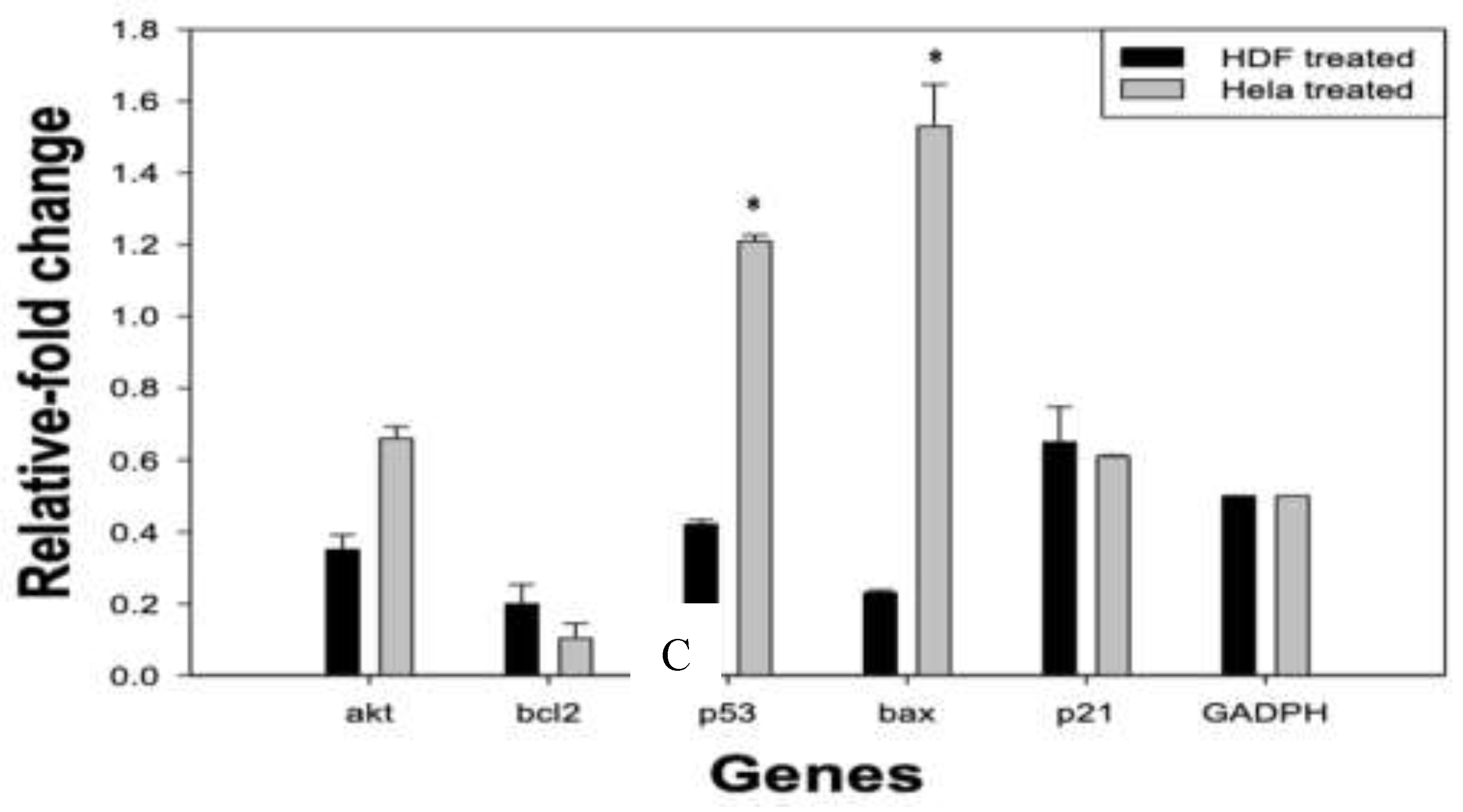

Gene Expression

The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50) for HeLa cells was determined to be 175 µg/mL.

Figure 4 illustrates the relative mRNA expression levels of genes associated with cell survival (

AKT,

BCL2), apoptosis (

P53,

BAX), and cell cycle arrest (

P21) in HeLa cells treated with RPPE, compared to RPPE-treated HDF cells (

Figure 4A-C). All expression levels were normalized to

GAPDH.

In HeLa cells, RPPE treatment induced a clear pro-apoptotic shift in gene expression. P53 expression increased significantly, with a fold change greater than 1.2, suggesting activation of tumor suppressor pathways. BAX, a downstream effector of p53 and a key pro-apoptotic gene, showed the highest upregulation, approaching a 1.6-fold increase, indicating a strong induction of mitochondrial apoptosis.

Conversely, BCL2 expression was markedly downregulated, consistent with elevated BAX levels and disruption of the BCL2/BAX ratio, which favors apoptotic signaling. AKT, a central regulator of cell proliferation and survival, was also suppressed, further contributing to the inhibition of survival pathways. Additionally, P21, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor involved in cell cycle arrest, was modestly upregulated, although to a lesser extent than the apoptotic markers. These findings suggest that while RPPE may induce some degree of cell cycle arrest, its predominant effect on HeLa cells is the activation of apoptotic pathways.

4. Discussion

The present study evaluated the cytotoxic and molecular effects of RPPE on HeLa cancer cells and HDF. Our findings showed that RPPE exhibits a selective cytotoxic cell viability effect against HeLa cells, while maintaining a relatively low impact on normal HDF cells. Cell viability assays revealed a dose- and time-dependent reduction in HeLa cell viability following RPPE treatment. Significant cytotoxicity was observed at concentrations ≥150 µg/mL, with viability dropping below 20% at 72 h. In contrast, HDF cells exhibited moderate sensitivity only at the highest concentration and longest exposure, suggesting a selective antitumor potential of RPPE. Several plant-derived compounds have previously documented cytotoxic effects against HeLa cells, including curcumin, quercetin, gallic acid, methyl gallate and triptolide [1,8,16]. Gallic acid and methyl gallate induced inhibitory effects on HeLa cell proliferation, exhibiting IC50 values of 10.00 ± 0.67 µg/mL and 11.00 ± 0.58 µg/mL, respectively[1]. Recent studies have shown that curcumin inhibited the proliferation of HeLa cells when administered at a concentration of 100 µg/mL for 24 h [16]. A quercetin concentration of 96.24 μM at 24 h and 25.5 μM at 48 h was required to achieve 50% inhibition of cell viability in HeLa cells [8]. Previous studies have revealed that rambutan peel (RP) extracts exerted marked antiproliferative effects on MDA-MB-231 and MG-63 cell lines; but no significant response was observed in HeLa cells when treated with yellow and red RP extracts at concentrations of 5–15 mg/mL for 72 hours [13]. Furthermore, human oral carcinoma cells (CLS-354) treated with 292 mg/mL of RP extract exhibited minimal cytotoxicity, suggesting a limited anticancer potential of RP polyphenols in this cell line [11]. In contrast, the present study demonstrates a measurable cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic effect of RPPE in HeLa cells. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in extract composition, purification methods, or treatment protocols. Notably, the aqueous extract of rambutan peel (fraction 1:16-0) [9], rich in soluble polyphenols (307.57 mg/g ± 20.27 mg/g), exerts a dose- and time-dependent cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells, which may enhance their bioactivity and cellular uptake. This enhanced cytotoxic response could be due to the presence of potent bioactive constituents such as Corilagin, Geraniin, Punigluconin, Ellagic acid pentoside, Ellagic acid, Tetragalloyl glucose, and Pedunculagin, known to modulate apoptotic pathways in various cancer models. This profile confirms the presence of key bioactive polyphenols in the 1:16-0 aqueous extract, which was selected for its high content of soluble polyphenols and used in subsequent biological assays. Additionally, variations in extraction solvents, treatment duration, and cell line responsiveness may further explain the observed differences. These findings suggest that rambutan peel extracts may exert selective cytotoxic cell viability effects in cervical cancer cells, potentially through the modulation of apoptotic pathways. However, further molecular characterization is required to validate its therapeutic relevance in CC.

Previously, we described the cytotoxic cell viability effects of RPPE on HeLa cervical cancer cells. This selective response was further supported by morphological observations, where HeLa cells exhibited hallmark features of apoptosis, including cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and detachment, following RPPE treatment, while HDF cells retained their typical fibroblastic morphology at comparable concentrations. These observations are consistent with our viability assays and support the antitumor potential of RPPE. Similar apoptotic changes have been reported in other cancer models exposed to natural compounds. Studies have observed early morphological alterations in HOS cells treated with rambutan extract, including loss of spindle shape and detachment, followed by shrinkage and apoptotic body formation at 72 h [11]. Additionally, it has been documented both structural and biochemical signs of apoptosis in HeLa cells treated with Sargassum polycystum extracts [14]. It has also been documented DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and membrane blebbing in HeLa cells exposed to GA and MG [1]. Recent evidence has shown that curcumin not only induced apoptosis but also caused cell cycle arrest in HeLa cells [8,16]. Collectively, these findings highlight the relevance of apoptosis signaling pathways in mediating the cytotoxic effects of natural compounds, including RPPE, and underscore their potential in cervical cancer therapy.

At the molecular level, RPPE treatment induced significant changes in gene expression profiles in HeLa cells. Notably, pro-apoptotic genes such as p53 and bax were strongly up-regulated, while anti-apoptotic and survival-related genes, including bcl-2 and akt were markedly downregulated. The upregulation of p21 suggests a concurrent activation of cell cycle arrest mechanisms, likely contributing to the inhibition of cell proliferation. Natural anticancer agents, such as rambutan extract, have previously been shown to induce apoptotic pathways in prostate cancer cells [22]. Downregulation of bcl-2 and upregulation of caspase-3 and caspase-9 in HOS cells treated with rambutan extract has been reported [22]. Similarly, quercetin has been shown to promote apoptosis in HeLa cells through the overexpression of caspase-3 [8]. Additionally, recent evidence revealed that curcumin activated apoptotic signaling via upregulation of p53 and caspase-3 in HeLa cervical cancer cells [16]. Gallic acid (GA) and methyl gallate (MG) have also been shown to induce apoptosis in HeLa cells by modulating key apoptotic regulators [1]. However, the understanding of how polyphenols induce apoptosis in cancer cell lines remains limited. Taken together, these findings support the notion that RPPE exerts its anticancer effects through modulation of key apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory genes in HeLa cells. While various polyphenolic compounds have indicated similar pro-apoptotic activity, the molecular mechanisms underlying their effects remain incompletely understood. Therefore, the present study provides valuable insight into the gene-level responses elicited by RPPE and underscores its potential as a promising natural agent for cervical cancer therapy.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that rambutan peel polyphenolic extract (RPPE) exerts selective cytotoxic cell viability effects on HeLa cervical cancer cells while sparing normal human dermal fibroblasts. RPPE treatment induced hallmark morphological features of apoptosis and significantly altered the expression of key genes involved in cell survival, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation. The upregulation of p53, bax, and p21, alongside the downregulation of bcl-2 and akt, suggests activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathways and cell cycle arrest. These findings highlight RPPE’s potential as a natural therapeutic agent for cervical cancer and challenge previous assumptions regarding the limited efficacy of rambutan-derived compounds in this model. Further studies are warranted to isolate and characterize the active constituents of RPPE, evaluate its in vivo efficacy, and explore its potential integration into adjuvant cancer therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JAMC and PME; methodology, MLMF, JAMC and PME; software, MLMF and IGV; validation, MLMF, JAMC and MASS; formal analysis, PME, MLMF, and JAMC; investigation JAMC and PME; resources, MLMF and JAV; data curation, PME; writing—original draft preparation, JAMC, PME and ACCN; writing—review and editing, ACCN; visualization, SSN; supervision, RRH; project administration MLMF, JAMC; funding acquisition, MLMF and JAMC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, please add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number for studies involving humans or animals. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Acknowledgments

We would like to give special thanks to Margarita L. Martínez-Fierro from the Molecular Medicine Laboratory in the Autonomous University of Zacatecas, Mexico where methodology was entirely developed. The authors are grateful to Juan Ascacio-Valdés for donating the Rambutan peel polyphenolic extract (RPPE) used for the experiments.:

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests. We declare that this manuscript is original and has not been published before.

References

- Abdullah, H., I. Ismail, R. Suppian, and N.M. Zakaria, Natural Gallic Acid and Methyl Gallate Induces Apoptosis in Hela Cells through Regulation of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Protein Expression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023; 24(10). [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.H., El-Abhar, H. S., Hassanin, E. A. K., Abdelkader, N. F., & Shalaby, M. B., Punica granatum suppresses colon cancer through downregulation of Wnt/ -Catenin in rat model. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 2017; 27(5): p. 8. [CrossRef]

- Anitha, P., R.V. Priyadarsini, K. Kavitha, P. Thiyagarajan, and S. Nagini, Ellagic acid coordinately attenuates Wnt/beta-catenin and NF-kappaB signaling pathways to induce intrinsic apoptosis in an animal model of oral oncogenesis. Eur J Nutr, 2013; 52(1): p. 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K., S. Mukherjee, J. Vanmanen, P. Banerjee, and J.E. Fata, Dietary Polyphenols, Resveratrol and Pterostilbene Exhibit Antitumor Activity on an HPV E6-Positive Cervical Cancer Model: An in vitro and in vivo Analysis. Front Oncol, 2019; 9: p. 352. [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.-C., L.-C. Lu, M.-H. Tsai, Y.-J. Chen, Y.-Y. Chen, S.-P. Yao, and C.-P. Hsu, The Inhibitory Effect of Ellagic Acid on Cell Growth of Ovarian Carcinoma Cells. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013; 2013: p. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, S.C.S., R.C. Bonadio, F.C.G. Gabrielli, A.S. Aranha, M.L.N. Dias Genta, V.C. Miranda, D. de Freitas, E. Abdo Filho, P.A.O. Ferreira, K.K. Machado, . . . M.D.P. Estevez-Diz, Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy With Cisplatin and Gemcitabine Followed by Chemoradiation Versus Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: A Randomized Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol, 2019; 37(33): p. 3124–3131. [CrossRef]

- Dretcanu, G., C.I. Iuhas, and Z. Diaconeasa, The Involvement of Natural Polyphenols in the Chemoprevention of Cervical Cancer. Int J Mol Sci, 2021; 22(16). [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S., M. Borappa, S. Kanakarajan, R. Selvaraj, N.J. Siddiqi, S. Wasi, A. Siyal, N. Patel, and P. Sharma, Apoptosis, DNA damage, and cell cycle arrest: The anticancer mechanisms of quercetin in human cervix epithelioid carcinoma cells. International Journal of Health Sciences, 2025; 19: p. 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, C., C.N. Aguilar, A.C. Flores-Gallegos, L. Sepúlveda, R. Rodríguez-Herrera, J. Morlett-Chávez, M. Govea-Salas, and J. Ascacio-Valdés, Preliminary Testing of Ultrasound/Microwave-Assisted Extraction (U/M-AE) for the Isolation of Geraniin from Nephelium lappaceum L. (Mexican Variety) Peel. Processes, 2020; 8(5). [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, C., L.E. Estrada-Gil, S.A. Lozano-Sepúlveda, A.M. Rivas-Estilla, M. Govea-Salas, J. Morlett-Chávez, C.N. Aguilar, and J.A. Ascacio-Valdés, Antiviral Activity of Rambutan Peel Polyphenols Obtained Using Green Extraction Technology and Solvents. Sustainable Chemistry, 2025; 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, W.S.W.N., P.M. Ridzuan, and A. Seeni, Nephelium lappaceum rind as a new chemopreventive agent: Arresting the cell cycle at G2/M and promoting apoptotic cell death in vitro on osteosarcoma cell lines. International Journal of Medical Toxicology & Legal Medicine, 2019; 22(3and4). [CrossRef]

- Jantapaso, H. and P. Mittraparp-Arthorn, Phytochemical Composition and Bioactivities of Aqueous Extract of Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L. cv. Rong Rian) Peel. Antioxidants (Basel), 2022; 11(5). [CrossRef]

- Khaizil Emylia, Z., Aina, S. N., & Dasuki, S. M. , Preliminary study on anti-proliferative activity of methanolic extract of Nephelium lappaceum peels towards breast (MDA-MB-231), cervical (HeLa) and osteosarcoma (MG-63) cancer cell lines. . Health, 2013; 4(2): p. 13.

- M Firdaus, D.S., I Islam, H Nursyam, H Kartikaningsih, H S Yufidasari, A A Prihanto, R Nurdiani and A A Jaziri, The reducibility of heLa cell viability by Sargassum polycystum extracts. OP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Sci1e2n3c4e, 2018; 137: p. 4. [CrossRef]

- Perumal, A., M.S. AlSalhi, S. Kanakarajan, S. Devanesan, R. Selvaraj, and V. Tamizhazhagan. Phytochemical evaluation and anticancer activity of rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) fruit endocarp extracts against human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG-2) cells. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 2021; 28(1): p. 9. [CrossRef]

- Purba, I.S., Y. Irwanto, B. Rahardjo, and P. Handayani, The Effect of Curcumin Administration on p53 and Caspase-3 Expression in Cervical Cancer HeLa Cell Culture. Asian Journal of Health Research, 2024; 3(3): p. 228–232. [CrossRef]

- Romero, S.A., I.C.B. Pavan, A.P. Morelli, M.C.S. Mancini, L.G.S. da Silva, I. Fagundes, C.H.R. Silva, L.G.S. Ponte, M.A. Rostagno, R.M.N. Bezerra, F.M. Simabuco. Anticancer effects of root and beet leaf extracts (Beta vulgaris L.) in cervical cancer cells (HeLa). Phytother Res, 2021; 35(11): p. 6191–6203. [CrossRef]

- Sanlier, N.T., K.G. Saçinti, İ. Türkoğlu, and N. Sanlier, Some Polyphenolic Compounds as Potential Therapeutic Agents in Cervical Cancer: The Most Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Nutrition Reviews, 2025; 83(5): p. 880–896.

- Small, W., Jr., M.A. Bacon, A. Bajaj, L.T. Chuang, B.J. Fisher, M.M. Harkenrider, A. Jhingran, H.C. Kitchener, L.R. Mileshkin, A.N. Viswanathan, . . . D.K. Gaffney, Cervical cancer: A global health crisis. Cancer, 2017; 123(13): p. 2404–2412. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D., and Pingdou, Q. , Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin inhibits DNA replication and consequently induces leukemia cell apoptosis. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2001; 7(1): p. 7.

- Tao, T., P. Zhang, Z. Zeng, and M. Wang, Advances in autophagy modulation of natural products in cervical cancer. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2023; 314: p. 116575.

- Utami, W.P., T.E. Tallei, G.L.A. Turalaki, L.E.N. Tendean, M.M. Kaseke, and D.S. Purwanto, Targeting Prostate Cancer with Rambutan Peel-Derived Compounds via Network Pharmacology. Malacca Pharmaceutics, 2025; 3(1): p. 42–49. [CrossRef]

- Venkatas, J. and M. Singh, Cervical cancer: a meta-analysis, therapy and future of nanomedicine. Ecancermedicalscience, 2020; 14: p. 1111. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Y. Luo, J. Yang, C. Hou, and J. Li, Inhibitory effects of polyphenols-enriched extracts from Debregeasia orientalis leaf against human cervical cancer in vitro & in vivo. Food and Agricultural Immunology, 2020; 31(1): p. 176–192. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., J. Yin, P. Liu, X. Zhang, Y. Lin, and J. Guo, Triptolide-induced cuproptosis is a novel antitumor strategy for the treatment of cervical cancer. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters, 2024; 29(1): p. 113.

- Zhang, Z., B. Chen, Y. Liu, K. Zhang, Z. Wei, Y. Dai, and C. Liu, Advances in Nanomedicine for Targeting Cancer Stem Cells and Overcoming Therapeutic Resistance. ACS nano, 2025; 19(34): p. 30720–30757.

- Zhu, H., H. Zhu, M. Tian, D. Wang, J. He, and T. Xu, DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation in Cervical Cancer: Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment. Front Genet, 2020; 11: p. 347. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).