Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- A systematic review of social-psychological theories and frameworks on stereotypes that will guide future computational research (Section 2). We also review the computational operationalization of these frameworks and theories, highlighting open opportunities. We analyze computational progress and gaps across domains such as narrative, media, and body imaging, and provide future directions (Section 3).

- 2.

- A multimodal, linguistic, and geographic analysis of stereotype research, identifying key gaps and underexplored requirements (Section 4).

- 3.

- A unified analysis of challenges in stereotype research by integrating social-psychological and computational perspectives (Section 5).

- 4.

- An analysis of implications for Responsible AI, framing stereotypes as foundational to downstream harms, and briefly examining existing mitigation approaches’ failures, while suggesting potential improvements through explainability and interpretability (Section 6).

2. Social Psychological Perspectives on Stereotypes

2.1. Foundational Theories

- 1.

- Similarity–Attraction and Social Identity Theory: As discussed in the introduction, similarity-attraction theory [8] and Social Identity Theory [9] posit systematic in-group favoritism, whereby individuals favor in-groups over out-groups to enhance self-esteem [10]. Self-esteem comprises personal and social identity, the latter derived from group memberships based on attributes such as nationality or age. According to Social Identity Theory, threats to self-esteem intensify in-group favoritism, which in turn restores self-worth, a prediction supported empirically [38,39]. From this perspective, stereotypes function as mechanisms for self-esteem maintenance, emerging through in-group favoritism and out-group derogation when out-groups are perceived as threatening, thereby conceptualizing stereotypes as self-esteem protectors.

- 2.

- Social Role Theory: This theory [40] focuses on socialization processes and posits that stereotypes are shaped by the social roles people occupy, such as lower-status versus higher-status jobs. Media plays a direct role in shaping stereotypes, often without individuals being consciously aware of its influence [41]. In particular, media representations strongly affect body image by promoting stereotypical ideals, such as muscular and lean bodies for males, and fashionable, thin bodies for females [42,43]. Social Role Theory is closely related to Social Learning Theory [44], as both emphasize learning through observation and social reinforcement. These theories conceptualize stereotypes as social representations representing existing social roles.

- 3.

- Social Categorization Theory: This theory states that group-based perception is as fundamental as individual-based perception [45]. It argues that stereotyping and categorization are the two central components of perception. It states that both the process of stereotyping and the content of stereotypes are fluid and dynamic, varying across social contexts. Social context determines the nature of self–other comparisons and shapes how group boundaries are constructed. It considers that stereotypes reflect the emergent properties of social groups. It conceptualizes stereotypes as psychologically valid representations [46], grounded in group-based cognition.

- 4.

- Theories Discussing Social Cognition: Social cognition–based theories [47,48,49,50] conceptualize stereotyping as a “necessary evil,” arising from the human cognitive need for simplicity and order. These theories view stereotypes as cognitive functions that simplify the complexity of the social world through implicit and often automatic processes. These theories conceptualize stereotypes as cognitive schemas structuring perception.

- 5.

- Social Justification Theory: This theory [51,52,53] states that holding negative stereotypes of another group may serve not only an ego-protective and group-protective function, but also a system-justifying function. It argues that when status hierarchies relegate groups to relative positions of inferiority and superiority, members of disadvantaged groups may themselves come to hold negative beliefs about their own groups in the service of a larger system in which social groups are hierarchically arranged [54]. This theory states that stereotypes can be considered as reinforcing the ideology of dominant groups, which may even be endorsed by disadvantaged groups themselves. It considers stereotypes as ideological representations.

- 6.

- Discursive Philosophy of Categorization: The previous approaches consider categorization as highly functional and adaptive, and are largely grounded in a realist epistemology (i.e., the assumption that reality can be understood through facts or reason). Discursive philosophy challenges this realist epistemology. It does not treat social categories as rigid internal entities used inflexibly; instead, it is concerned with how people discursively construct social categories. It examines how these constructions produce subjectivities for both the self and those defined as the “Other.” Wetherell and Potter [55] states that people are often inconsistent and highly context-dependent in articulating their beliefs. According to this perspective, stereotypes are relatively stable, shared, and identifiable, yet emerge through discourse rather than internal cognition. Similarly, Edwards [56] conceptualize stereotypes and categorization as discursive constructions rather than cognitive processes [46].

- 7.

- Intersectionality Theory: Recent work [57,58,59] emphasizes that social identities such as race, gender, and ethnicity interact rather than operate independently. From this perspective, stereotypes are not isolated constructs but emerge through the intersection of multiple identity dimensions, producing distinct and context-dependent forms of discrimination (e.g., experiences specific to Asian American women). Intersectionality thus frames stereotypes as relational and co-constructed structures across social categories.

2.2. Major Frameworks

- 1.

- Stereotype Content Model (SCM): The SCM proposes that group stereotypes are structured along two fundamental dimensions: warmth (perceived intent) and competence (perceived ability) [7]. Warmth judgments are shaped primarily by perceived competition, while competence judgments reflect perceived status. These dimensions yield four canonical stereotype profiles: admiration (high warmth, high competence; e.g., ingroups), pity (high warmth, low competence; e.g., the elderly or people with disabilities), envy (low warmth, high competence; e.g., high-status outgroups), and contempt (low warmth, low competence; e.g., stigmatized groups). Each quadrant is associated with distinct emotional and behavioral tendencies, ranging from active facilitation to active harm, enabling the SCM to predict real-world social behaviors such as inclusion, neglect, or discrimination [7,60].

- 2.

- Agency–Beliefs–Communion (ABC) Model: The ABC model2 [62] reframes stereotype content by positing that social perception is fundamentally organized around Agency (socioeconomic power) and Beliefs (ideological orientation), rather than the warmth-competence dimensions central to the SCM. Developed as a critique of SCM, it challenges its theory-driven structure and reliance on predefined social groups, which may limit the discovery of naturally salient dimensions. Adopting a bottom-up approach, the ABC model shows that Communion (including warmth and morality) is not a primary dimension but an emergent construct arising from combinations of Agency and Beliefs. Empirical evidence across multiple studies indicates that spontaneous group categorization aligns most strongly with these two dimensions: Agency shapes power-related judgments, while Beliefs capture ideological alignment. Notably, groups at extreme levels of Agency are perceived as low in communion, whereas moderate Agency is associated with higher communal attributions, suggesting that warmth-based judgments are secondary rather than foundational.

- 3.

- Dual-Perspective Model: The SCM proposed by Fiske et al. [7] considers competence as Agency (A) and warmth as Communion (C). Abele et al. [63] observed that A and C contain multiple components; for example, masculinity (e.g., “assertive” or “decisive”) is also part of Agency, while morality (e.g., “fair,” “honest”) is part of Communion. They proposed a facet model that differentiates A into assertiveness (AA) and competence (AC), and C into warmth (CW) and morality (CM), and reported a good model fit.

- 4.

- Five-Tuple Framework: Both Davani et al. [64] and Shejole and Bhattacharyya [36] converge on a five-tuple framework for characterizing stereotypes, consisting of the target group (T), relationship characteristics (R), associated attributes (A), the perceiving group or community in which the stereotype is held (C), and the context or time interval (I) in which it emerges. Both works emphasize that stereotypes are inherently dynamic, varying across social groups and evolving over time, rather than being static representations. This perspective aligns with earlier social psychological theories highlighting the context-dependent and socially constructed nature of stereotyping [45]. This framework is particularly valuable for computational modeling of stereotypes, as it enables the integration of diverse methodological approaches, such as knowledge graph- based representations, to support structured and systematic analysis.

3. Computational Research on Stereotypes

3.1. Operationalizing Social-Psychological Frameworks

3.2. Narrative and Media-Based Analyses

3.3. Body-Image Stereotypes

4. Analyzing Multimodal, Linguistic and Geographic Coverage

4.1. Multimodal Representations

4.2. Linguistic and Geographic Coverage

5. Challenges in Stereotype Research

5.1. The Problem of Generalization

5.2. Annotation and Labeling Challenges

5.3. Scalability Constraints

5.4. The Dynamic Nature of Stereotypes

6. Implications for Responsible AI

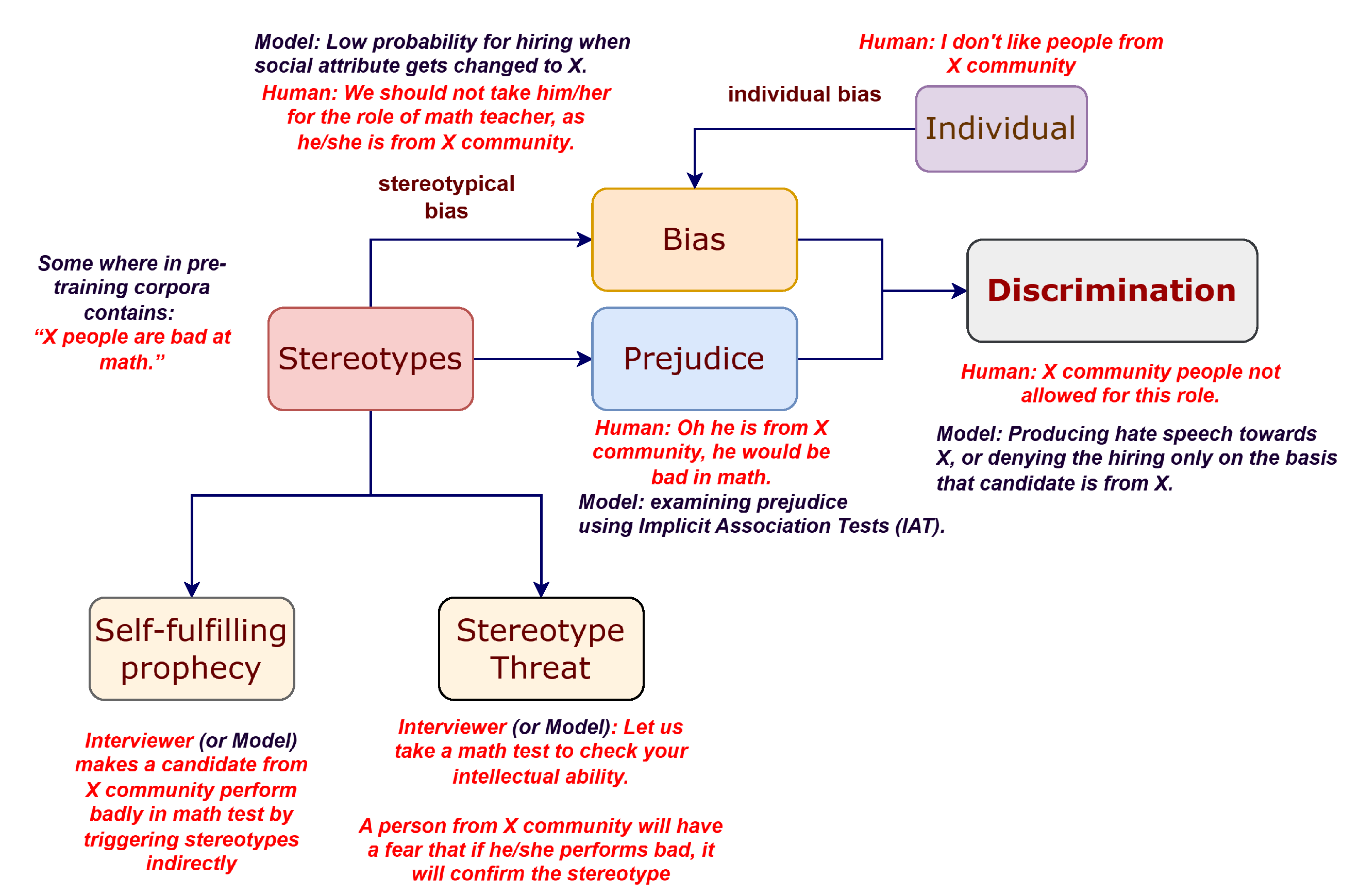

6.1. Stereotype is the root cause

6.2. Does the Absence of Stereotypical Outputs Imply Fairness?

6.3. Mitigation, Interpretability, and Explainability

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations

Appendix A. Stereotypes, Bias, Prejudice and Discrimination

Appendix A.1. Stereotypes

Appendix A.2. Bias

Appendix A.3. Prejudice

Appendix A.4. Discrimination

Appendix A.5. Distinguishing Stereotypes from Bias

Appendix B. Summarizing Social-Psychological Theories and Frameworks

| Theory / Framework | Core Assumptions | View of Stereotypes | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity-Attraction & Social Identity Theory | Individuals derive self-esteem from group memberships; intergroup comparison motivates ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation. Social identity is shaped by perceived group belonging. | Stereotypes function as self-esteem regulators that maintain positive social identity and reinforce ingroup–outgroup boundaries. | Byrne [8], Tajfel and Turner [9], Turner and Reynolds [10], Ellemers and Haslam [38] |

| Social Role Theory | Social structures and role distributions shape expectations about groups; repeated exposure normalizes role-based differences. | Stereotypes emerge as reflections of socially assigned roles and are reinforced through cultural and media representations. | Eagly [40], Ward and Friedman [41], Gauntlett [42], Bartlett et al. [43] |

| Social Categorization Theory | Humans perceive the social world through group-based categorization; context determines which identities become salient. | Stereotypes are fluid, context-dependent representations emerging from group-level perception rather than fixed beliefs. | Turner et al. [45], Augoustinos and Walker [46] |

| Social Cognition Theories | Cognitive efficiency drives humans to rely on schemas and heuristics to manage informational complexity. | Stereotypes are cognitive shortcuts—functional yet potentially biasing mental representations. | Fiske [47], Fiske and Haslam [49], Fiske and Taylor [50] |

| System Justification Theory | Individuals are motivated to preserve existing social hierarchies, even when personally disadvantaged by them. | Stereotypes serve ideological functions by legitimizing and stabilizing unequal social systems. | Jost et al. [51], Jost and Van der Toorn [52], Jost [53], Banaji [54] |

| Discursive Approaches to Categorization | Social reality is constructed through language and discourse rather than fixed cognitive representations. | Stereotypes are discursive resources—contextual, flexible, and rhetorically constructed in interaction. | Augoustinos and Walker [46], Wetherell and Potter [55], Edwards [56] |

| Intersectionality Theory | Social identities are interdependent and mutually constitutive rather than additive. | Stereotypes emerge at the intersections of multiple identities, producing context-specific and compounded forms of marginalization. | Cho et al. [57], Carastathis [58], Crenshaw [59] |

| Stereotype Content Model (SCM) | Group perception is structured along warmth and competence dimensions shaped by competition and status. | Stereotypes map onto predictable emotional and behavioral responses (e.g., admiration, pity, contempt). | Fiske et al. [7], Cuddy et al. [60] |

| Agency-Beliefs-Communion (ABC) Model | Social perception is organized around agency and ideological beliefs, with communion emerging secondarily. | Stereotypes reflect perceived power relations and ideological alignment rather than intrinsic warmth. | Koch et al. [62] |

| Dual-Perspective (Facet) Model | Agency and communion each consist of multiple sub-dimensions (e.g., assertiveness, morality). | Stereotypes operate through fine-grained evaluative dimensions rather than coarse traits. | Abele et al. [63] |

| Five-Tuple Framework | Stereotypes are relational, contextual, and temporally grounded phenomena. | Stereotypes are structured as (Target, Relation, Attributes, Community, Time Interval), enabling computational modeling. | Shejole and Bhattacharyya [36], Davani et al. [64] |

| Aspect | Stereotype Content Model (SCM) | Agency-Beliefs-Communion (ABC) Model |

|---|---|---|

| Core dimensions | Warmth and competence | Agency and beliefs; communion is emergent |

| Methodological stance | Theory-driven; predefined groups and traits | Data-driven; dimensions emerge from spontaneous judgments |

| Conceptual focus | Intentions (warmth) and ability (competence) | Socioeconomic power (agency) and ideology (beliefs) |

| Role of communion | Fundamental evaluative dimension | Derived from combinations of agency and beliefs |

| Group perception | Warmth and competence vary independently | Extreme agency predicts lower perceived communion |

Appendix C. Briefly Analyzing Failure of Bias Mitigation Strategies

Appendix D. Use of AI Assistants

References

- Bruner, J.S.; Goodnow, J.J.; George, A. Austin. A study of thinking. In New York: John Wiley Sons, Inc; 1956; Volume 14, p. 330. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, R.N.; Hovland, C.I.; Jenkins, H.M. Learning and memorization of classifications. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1961, 75, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosch, E. Principles of categorization. In Cognition and categorization; Routledge, 2024; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B. The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linville, P.W.; Fischer, G.W.; Salovey, P. Perceived distributions of the characteristics of in-group and out-group members: Empirical evidence and a computer simulation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, B.; Dovidio, J.F.; Johnson, C.; Copper, C. In-group-out-group differences in social projection. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 28, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.C.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. The Attraction Paradigm; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.C.; Reynolds, K.J. The social identity perspective in intergroup relations: Theories, themes, and controversies; Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intergroup processes, 2003; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. J. Soc. Issues 2004, 60, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 40, 61–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, fast and slow. In Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harari, Y.N. Sapiens: A brief history of humankind; Random House, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs, D.; Hagan, C.C.; Dalgleish, T.; Silston, B.; Prévost, C. The ecology of human fear: Survival optimization and the nervous system. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 121062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDoux, J. Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron 2012, 73, 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, J. Extreme fear: The science of your mind in danger; St. Martin’s Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G. Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind; University of Chicago press, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, D.A. It’s a jungle in there: How competition and cooperation in the brain shape the mind; Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, D.R. Animal minds: Beyond cognition to consciousness; University of Chicago Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, B.; Wei, Y. LLMs as Promising Personalized Teaching Assistants: How Do They Ease Teaching Work? ECNU Rev. Educ. 2025, 8, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, F.; Hoffmann, L.; Dos Santos, D.P.; Makowski, M.R.; Saba, L.; Prucker, P.; Hadamitzky, M.; Navab, N.; Kather, J.N.; Truhn, D.; et al. Large language models for structured reporting in radiology: Past, present, and future. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 2589–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, T.P.; Loureiro, R.B.; Lisboa, F.V.; Peixoto, R.M.; Guimarães, G.A.; Cruz, G.O.; Araujo, M.M.; Santos, L.L.; Cruz, M.A.; Oliveira, E.L.; et al. Bias and unfairness in machine learning models: A systematic review on datasets, tools, fairness metrics, and identification and mitigation methods. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeoung, S.; Ge, Y.; Diesner, J. StereoMap: Quantifying the Awareness of Human-like Stereotypes in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Singapore, Bouamor, H., Pino, J., Bali, K., Eds.; 2023; pp. 12236–12256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guo, M.; Su, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Li, H.; Qiu, M.; Liu, S.S. Bias in large language models: Origin, evaluation, and mitigation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Bethke, A.; Reddy, S. StereoSet: Measuring stereotypical bias in pretrained language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing; Online, Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W., Navigli, R., Eds.; 2021; Volume 1, pp. 5356–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felkner, V.K.; Chang, H.C.H.; Jang, E.; May, J. Winoqueer: A community-in-the-loop benchmark for anti-lgbtq+ bias in large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.15087. [Google Scholar]

- Nangia, N.; Vania, C.; Bhalerao, R.; Bowman, S.R. CrowS-Pairs: A Challenge Dataset for Measuring Social Biases in Masked Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); Online, Webber, B., Cohn, T., He, Y., Liu, Y., Eds.; 2020; pp. 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, N.; Kulkarni, P.; Ahmad, A.; Goyal, T.; Asad, N.; Garimella, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. IndiBias: A Benchmark Dataset to Measure Social Biases in Language Models for Indian Context. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Mexico City, Mexico, Duh, K., Gomez, H., Bethard, S., Eds.; 2024; Volume 1, pp. 8786–8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, I.; Yadav, C.; Nagireddy, M.; Das, P.; Varshney, K.R. Keeping Up with the Language Models: Systematic Benchmark Extension for Bias Auditing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.12620. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish, A.; Chen, A.; Nangia, N.; Padmakumar, V.; Phang, J.; Thompson, J.; Htut, P.M.; Bowman, S. BBQ: A hand-built bias benchmark for question answering. Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022, 2022, 2086–2105. [Google Scholar]

- Tomar, A.; Sahoo, N.R.; Bhattacharyya, P. Bharatbbq: A multilingual bias benchmark for question answering in the indian context. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2025, 13, 1672–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehman, S.; Gururangan, S.; Sap, M.; Choi, Y.; Smith, N.A. RealToxicityPrompts: Evaluating Neural Toxic Degeneration in Language Models. Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, 2020, 3356–3369. [Google Scholar]

- Dhamala, J.; Sun, T.; Kumar, V.; Krishna, S.; Pruksachatkun, Y.; Chang, K.W.; Gupta, R. Bold: Dataset and metrics for measuring biases in open-ended language generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, 2021; pp. 862–872. [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos, I.O.; Rossi, R.A.; Barrow, J.; Tanjim, M.M.; Kim, S.; Dernoncourt, F.; Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Ahmed, N.K. Bias and Fairness in Large Language Models: A Survey. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 50, 1097–1179. Available online: https://direct.mit.edu/coli/article-pdf/50/3/1097/2471010/coli_a_00524.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Shejole, K.S.; Bhattacharyya, P. StereoDetect: Detecting Stereotypes and Anti-stereotypes the Correct Way Using Social Psychological Underpinnings. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2025; Christodoulopoulos, C., Chakraborty, T., Rose, C., Peng, V., Eds.; Suzhou, China, 2025; pp. 4051–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, A.; Murthy, R.; Bhattacharyya, P. Stereotype Detection as a Catalyst for Enhanced Bias Detection: A Multi-Task Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025; Che, W., Nabende, J., Shutova, E., Pilehvar, M.T., Eds.; Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 17304–17317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N.; Haslam, S.A. Social identity theory. Handb. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 2, 379–398. [Google Scholar]

- Postmes, T.E.; Branscombe, N.R. Rediscovering social identity.; Psychology Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-role Interpretation; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L.M.; Friedman, K. Using TV as a guide: Associations between television viewing and adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauntlett, D. Media, gender and identity: An introduction; Routledge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, D.; Rocamora, A.; Cole, S. Fashion Media. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social learning theory; Prentice hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1977; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.C.; Hogg, M.A.; Oakes, P.J.; Reicher, S.D.; Wetherell, M.S. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory.; basil Blackwell, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Augoustinos, M.; Walker, I. The construction of stereotypes within social psychology: From social cognition to ideology. Theory Psychol. 1998, 8, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T. Thinking is for doing: Portraits of social cognition from daguerreotype to laserphoto. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; et al. Social cognition and social perception. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1993, 44, 155–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.P.; Haslam, N. Social cognition is thinking about relationships. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1996, 5, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social cognition: From brains to culture; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, J.T.; Banaji, M.R.; Nosek, B.A. A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychol. 2004, 25, 881–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Van der Toorn, J. System justification theory. Handb. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 2, 313–343. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, J.T. A quarter century of system justification theory: Questions, answers, criticisms, and societal applications. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 58, 263–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaji, M.R. Stereotypes, social psychology of. International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences 2002, 15100–15104. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell, M.; Potter, J. Mapping the language of racism: Discourse and the legitimation of exploitation; Columbia University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, D. Categories are for talking: On the cognitive and discursive bases of categorization. Theory Psychol. 1991, 1, 515–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Crenshaw, K.W.; McCall, L. Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: J. Women Cult. Soc. 2013, 38, 785–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carastathis, A. The concept of intersectionality in feminist theory. Philos. Compass 2014, 9, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In Feminist legal theories; Routledge, 2013; pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J.C.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. Stereotype content model across cultures: Towards universal similarities and some differences. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 50, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, D. The duality of human existence: An essay on psychology and religion; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, A.; Imhoff, R.; Dotsch, R.; Unkelbach, C.; Alves, H. The ABC of stereotypes about groups: Agency/socioeconomic success, conservative-progressive beliefs, and communion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 110, 675–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, A.E.; Hauke, N.; Peters, K.; Louvet, E.; Szymkow, A.; Duan, Y. Facets of the fundamental content dimensions: Agency with competence and assertiveness—Communion with warmth and morality. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davani, A.M.; Dev, S.; Pérez-Urbina, H.; Prabhakaran, V. A Comprehensive Framework to Operationalize Social Stereotypes for Responsible AI Evaluations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2025; pp. 30018–30031. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, K.C.; Nejadgholi, I.; Kiritchenko, S. Understanding and countering stereotypes: A computational approach to the stereotype content model. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.02596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, G.; Bai, X.; Fiske, S.T. Comprehensive stereotype content dictionaries using a semi-automated method. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, K.C.; Kiritchenko, S.; Nejadgholi, I. Computational modeling of stereotype content in text. Front. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 826207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, B.; Waller, J.; Kushalnagar, R. Applying the stereotype content model to assess disability bias in popular pre-trained NLP models underlying AI-based assistive technologies. In Proceedings of the Ninth workshop on speech and language processing for assistive technologies (SLPAT-2022), 2022; pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ungless, E.; Rafferty, A.; Nag, H.; Ross, B. A robust bias mitigation procedure based on the stereotype content model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fifth Workshop on Natural Language Processing and Computational Social Science (NLP+ CSS), 2022; pp. 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Omrani, A.; Ziabari, A.S.; Yu, C.; Golazizian, P.; Kennedy, B.; Atari, M.; Ji, H.; Dehghani, M. Social-group-agnostic bias mitigation via the stereotype content model. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2023, Volume 1, 4123–4139. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.T.; Sotnikova, A.; Daumé, H., III; Rudinger, R.; Zou, L. Theory-grounded measurement of US social stereotypes in English language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.11684. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, K.; Kiritchenko, S.; Nejadgholi, I. How Does Stereotype Content Differ across Data Sources? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics (*SEM 2024), Mexico City, Mexico; Bollegala, D., Shwartz, V., Eds.; 2024; pp. 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y.; Johnson, K. Korean stereotype content model: Translating stereotypes across cultures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Cross-Cultural Considerations in NLP (C3NLP 2025), 2025; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schweinitz, J.; Eder, J.; Jannidis, F.; Schneider, R. Stereotypes and the narratological analysis of film characters. Revisionen 2010, 276–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.M.; Goh, J.Y.; Tan, T.H.; Siew, C.S. Gender stereotypes in Hollywood movies and their evolution over time: Insights from network analysis. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; Wang, C.J. The Cinderella Complex: Word embeddings reveal gender stereotypes in movies and books. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, A.G.; Ferreira, C.; Arias-Gago, A.R. Stereotyped Representations of Disability in Film and Television: A Critical Review of Narrative Media. Disabilities 2025, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehatta, S. Breaking stereotypes: A multimodal analysis of the representation of the female lead in the animation movie Brave. Textual Turnings: Int. Peer-Rev. J. Engl. Stud. 2020, 2, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atillah, W.; Arifin, M.B.; Valiantien, N.M. An Analysis Of Stereotype In Zootopia Movie. Ilmu Budaya: J. Bahasa, Sastra, Seni, Dan Budaya 2020, 4, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J. Analysis of gender stereotypes in Disney female characters. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Literature, Art and Human Development (ICLAHD 2021), 2021; Atlantis Press; pp. 451–454. [Google Scholar]

- Madaan, N.; Mehta, S.; Agrawaal, T.S.; Malhotra, V.; Aggarwal, A.; Saxena, M. Analyzing gender stereotyping in bollywood movies. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.04117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, N.; Mehta, S.; Saxena, M.; Aggarwal, A.; Agrawaal, T.S.; Malhotra, V. Bollywood Movie Corpus for Text, Images and Videos. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.04142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, N.; Mehta, S.; Agrawaal, T.; Malhotra, V.; Aggarwal, A.; Gupta, Y.; Saxena, M. Analyze, detect and remove gender stereotyping from bollywood movies. In Proceedings of the Conference on fairness, accountability and transparency. PMLR, 2018; pp. 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, C. Stereotypes at the intersection of perceivers, situations, and identities: Analyzing stereotypes from storytelling using natural language processing. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lelwica, M. The religion of thinness. Scr. Instituti Donneriani Abo. 2011, 23, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A.; Westergren, A.; Berggren, V.; Ekblom; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Perceived and Ideal Body Image in Young Women in South Western Saudi Arabia. J. Obes. 2015, 2015, 697163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musaiger, A.O.; Al-Awadi, A.h.A.; Al-Mannai, M.A. Lifestyle and social factors associated with obesity among the Bahraini adult population. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2000, 39, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, A.; Chen, A.; Nangia, N.; Padmakumar, V.; Phang, J.; Thompson, J.; Htut, P.M.; Bowman, S.R. BBQ: A hand-built bias benchmark for question answering. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.08193. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, N.; Sahoo, N.R.; Murthy, R.; Nath, S.; Bhattacharyya, P. “You are Beautiful, Body Image Stereotypes are Ugly!” BIStereo: A Benchmark to Measure Body Image Stereotypes in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025; Che, W., Nabende, J., Shutova, E., Pilehvar, M.T., Eds.; Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 24471–24496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, K.; Kiritchenko, S. Examining Gender and Racial Bias in Large Vision–Language Models Using a Novel Dataset of Parallel Images. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics; St. Julian’s, Malta, Graham, Y., Purver, M., Eds.; 2024; Volume 1, pp. 690–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Prabhakaran, V.; Denton, R.; Laszlo, S.; Dave, S.; Qadri, R.; Reddy, C.; Dev, S. Visage: A global-scale analysis of visual stereotypes in text-to-image generation. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2024, Volume 1, 12333–12347. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.H.; Jeon, S.; Montgomery, J.M.; Lai, C.K. Visual Cues of Gender and Race are Associated with Stereotyping in Vision-Language Models. arXiv arXiv:2503.05093. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Lai, E.; Jiang, J. Vlstereoset: A study of stereotypical bias in pre-trained vision-language models. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 12th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing 2022, Volume 1, 527–538. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, B. Investigating Stereotypical Bias in Large Language and Vision-Language Models. PhD thesis, University of Auckland New Zealand, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, T.; Bisk, Y. Worst of both worlds: Biases compound in pre-trained vision-and-language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing (GeBNLP), 2022; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidieh, K.; Zhang, H.; Gerych, W.; Hartvigsen, T.; Ghassemi, M. Identifying implicit social biases in vision-language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 2024; Vol. 7, pp. 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.; Johansson, R. Controlling for Stereotypes in Multimodal Language Model Evaluation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fifth BlackboxNLP Workshop on Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Hybrid), Bastings, J., Belinkov, Y., Elazar, Y., Hupkes, D., Saphra, N., Wiegreffe, S., Eds.; 2022; pp. 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurinec, C.A.; Weaver, C.A., III. “Sounding Black”: Speech stereotypicality activates racial stereotypes and expectations about appearance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 785283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Mostafazadeh Davani, A.; Reddy, C.K.; Dave, S.; Prabhakaran, V.; Dev, S. SeeGULL: A Stereotype Benchmark with Broad Geo-Cultural Coverage Leveraging Generative Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Toronto, Canada, Rogers, A., Boyd-Graber, J., Okazaki, N., Eds.; 2023; Volume 1, pp. 9851–9870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.; Wu, Z.; Koshiyama, A.; Kazim, E.; Treleaven, P. HEARTS: A Holistic Framework for Explainable, Sustainable and Robust Text Stereotype Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.11579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekun, W.; Bulathwela, S.; Koshiyama, A.S. Towards Auditing Large Language Models: Improving Text-based Stereotype Detection. ArXiv 2023, abs/2311.14126. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett, S.L.; Lopez, G.; Olteanu, A.; Sim, R.; Wallach, H. Stereotyping Norwegian Salmon: An Inventory of Pitfalls in Fairness Benchmark Datasets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing; Online, Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W., Navigli, R., Eds.; 2021; Volume 1, pp. 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, N.; Yoo, H.; Oh, A.; Lee, H. KoBBQ: Korean bias benchmark for question answering. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 12, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Oh, J.; Lee, J.; Ahn, J.; Moon, J.; Park, S.; Oh, A. KOLD: Korean offensive language dataset. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022; pp. 10818–10833. [Google Scholar]

- Névéol, A.; Dupont, Y.; Bezançon, J.; Fort, K. French CrowS-pairs: Extending a challenge dataset for measuring social bias in masked language models to a language other than English. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, Volume 1, 8521–8531. [Google Scholar]

- Bosco, C.; Patti, V.; Frenda, S.; Cignarella, A.T.; Paciello, M.; D’Errico, F. Detecting racial stereotypes: An Italian social media corpus where psychology meets NLP. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignarella, A.T.; Sanguinetti, M.; Frenda, S.; Marra, A.; Bosco, C.; Basile, V. QUEEREOTYPES: A multi-source Italian corpus of stereotypes towards LGBTQIA+ community members. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024, 2024, 13429–13441. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser-Nieto, W.S.; Cignarella, A.T.; Bourgeade, T.; Frenda, S.; Ariza-Casabona, A.; Mario, L.; Cicirelli, P.G.; Marra, A.; Corbelli, G.; Benamara, F.; et al. Stereohoax: A multilingual corpus of racial hoaxes and social media reactions annotated for stereotypes. Language Resources and Evaluation 2024, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeade, T.; Cignarella, A.T.; Frenda, S.; Laurent, M.; Schmeisser-Nieto, W.; Benamara, F.; Bosco, C.; Moriceau, V.; Patti, V.; Taulé, M. A multilingual dataset of racial stereotypes in social media conversational threads. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2023, 2023; pp. 686–696. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.; Smith, J.; Lee, A.; Kumar, R.; Wang, L. SHADES: Towards a Multilingual Assessment of Stereotypes in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2025; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 11995–12041. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Romanou, A.; Fourrier, C.; Adelani, D.I.; Ngui, J.G.; Vila-Suero, D.; Limkonchotiwat, P.; Marchisio, K.; Leong, W.Q.; Susanto, Y.; et al. Global mmlu: Understanding and addressing cultural and linguistic biases in multilingual evaluation. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2025, Volume 1, 18761–18799. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, S.; Fromm, M.; Welch, C.; Görge, R.; Karimi, A.; Plepi, J.; Mowmita, N.; Flores-Herr, N.; Ali, M.; Flek, L. Do Multilingual Large Language Models Mitigate Stereotype Bias? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Cross-Cultural Considerations in NLP, 2024; pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa, L.C.L.; Feng, Y.; Lee, M. Social Bias in Multilingual Language Models: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2025; pp. 27845–27868. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, C.M.; Aronson, J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrawgi, H.; Rath, P.; Singhal, T.; Dandapat, S. Uncovering Stereotypes in Large Language Models: A Task Complexity-based Approach. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (EACL), 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 1841–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. The self-fulfilling prophecy. Antioch Rev. 1948, 8, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jussim, L. Self-fulfilling prophecies: A theoretical and integrative review. Psychol. Rev. 1986, 93, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, A.; Fierrez, J.; Morales, A.; Mancera, G.; Lopez-Duran, M.; Tolosana, R. Addressing bias in LLMs: Strategies and application to fair AI-based recruitment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 2025; Vol. 8, pp. 1976–1987. [Google Scholar]

- Anzenberg, E.; Samajpati, A.; Chandrasekar, S.; Kacholia, V. Evaluating the Promise and Pitfalls of LLMs in Hiring Decisions. arXiv arXiv:2507.02087. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Guan, X.; Thaler, M.; Koshiyama, A.; Lu, S.; Beepath, S.; Ertekin, E.; Perez-Ortiz, M. Jobfair: A framework for benchmarking gender hiring bias in large language models. Proceedings of the Findings of the association for computational linguistics: EMNLP 2024, 2024, 3227–3246. [Google Scholar]

- An, H.; Acquaye, C.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Rudinger, R. Do Large Language Models Discriminate in Hiring Decisions on the Basis of Race, Ethnicity, and Gender? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, L.; Liu, A.; MacNeil, S.; Metaxa, D. The silicon ceiling: Auditing gpt’s race and gender biases in hiring. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th ACM Conference on Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization, 2024; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Krieger, L.H. Implicit bias: Scientific foundations. Calif. Law Rev. 2006, 94, 945–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J. Pills for prejudice: Implicit bias and technical fix for racism. Am. J. Law Med. 2017, 43, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, B.K.; Vuletich, H.A.; Lundberg, K.B. The bias of crowds: How implicit bias bridges personal and systemic prejudice. Psychol. Inq. 2017, 28, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; McGhee, D.E.; Schwartz, J.L.K. Measuring Individual Differences in Implicit Cognition: The Implicit Association Test. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; McGhee, D.E.; Schwartz, J.L.K. Measuring Individual Differences in Implicit Cognition: The Implicit Association Test. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 74, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, A.; Sucholutsky, I.; Griffiths, T.L. Measuring implicit bias in explicitly unbiased large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, A. Detecting the presence of social bias in GPT-3.5 using association tests. In Proceedings of the 2023 international conference on advanced computing technologies and applications (ICACTA), 2023; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Duan, H.; Abbasi, A.; Lalor, J.P.; Tam, K.Y. Bias a-head? analyzing bias in transformer-based language model attention heads. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Trustworthy NLP (TrustNLP 2025), 2025; pp. 276–290. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Salinas, A.; Nyarko, J.; Henderson, P. Breaking Down Bias: On The Limits of Generalizable Pruning Strategies. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2025; pp. 2437–2450. [Google Scholar]

- Zayed, A.; Mordido, G.; Shabanian, S.; Baldini, I.; Chandar, S. Fairness-aware structured pruning in transformers. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, Vol. 38, 22484–22492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, P.S.; Raj, C.; Zhu, Z.; Lin, J.; Marasco, E. Toward Inclusive Language Models: Sparsity-Driven Calibration for Systematic and Interpretable Mitigation of Social Biases in LLMs. Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2025, 2025, 2475–2508. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why should i trust you?" Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, P.G. Stereotypes and Prejudice: Their Automatic and Controlled Components. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, M.; Swann, W.B. Hypothesis-testing processes in social interaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1978, 36, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Hewstone, M.; Glick, P.; Esses, V.M. Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination: Theoretical and Empirical Overview. In The SAGE Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination; Dovidio, J.F., Hewstone, M., Glick, P., Esses, V.M., Eds.; SAGE Publications, 2010; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhausen, G.V.; Richeson, J.A. Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. In Advanced Social Psychology: The State of the Science; Baumeister, R.F., Finkel, E.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2010; pp. 350–380. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Intergroup Contact Theory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. The Economics of Discrimination; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, E.S. The Statistical Theory of Racism and Sexism. Am. Econ. Rev. 1972, 62, 659–661. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, K.J. The Theory of Discrimination. In Discrimination in Labor Markets; Ashenfelter, O., Rees, A., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1973; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pager, D.; Shepherd, H. The Sociology of Discrimination: Racial Discrimination in Employment, Housing, Credit, and Consumer Markets. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2008, 34, 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | System 1 refers to fast, automatic, intuitive, and emotion-driven cognition, in contrast to System 2, which is slower, deliberate, and analytical [13]. |

| 2 | The terms Agency (A) and Communion (C) were coined by Bakan [61]. |

| 3 | Anti-stereotypes refer to attributes strongly counter to commonly held beliefs about a social group (e.g., football players being weak). |

| 4 | These dimensions were Sociability, Morality, Ability, Assertiveness, Beliefs, and Status. |

| 5 | Skin complexion, body shape, height, attire, hair texture, and eye color. |

| Section | Subsection | Future Research Scope & Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| Section 2 | Major Frameworks (Section 2.2) | Leverage the Five-Tuple Framework (Target, Relation, Attributes, Community, Time) to enable structured computational analysis, such as through knowledge graph-based representations. |

| Section 3 | Computational Operationalization (Section 3.1) | Focus on using social-psychological theories to guide the development of robust techniques for measuring and operationalizing stereotypes; address gaps in multilingual and multicultural contexts. |

| Narrative/Media (Section 3.2) | Implement proactive identification of stereotypes in media narratives to assess and mitigate potential social harms before dissemination. | |

| Body-Image (Section 3.3) | Systematically quantify body-image bias in LLMs and develop automatic modeling from media representations to monitor stereotypical ideals. | |

| Section 4 | Multimodality (Section 4.1) | Expand investigations into stereotype detection and mitigation beyond text and images to include conversational audio and video. |

| Linguistic/Geographic Coverage (Section 4.2) | Create conceptually grounded, multilingual benchmarks moving beyond English/US-centric data; include complex dimensions like caste and regional state-level perceptions (e.g., India or USA). | |

| Section 5 | Generalization (Section 5.1) | Research more efficient methods for social analysis to help models handle unseen target groups and extract context-specific information. |

| Annotation (Section 5.2) | Select representative annotator subsets reflecting the target community to ensure unbiased benchmarks and avoid skewed selections. | |

| Scalability (Section 5.3) | Explore strategies for modeling contexts separately to achieve global inclusivity despite current resource and scalability constraints. | |

| Dynamic Nature (Section 5.4) | Systematically study the dynamic nature of stereotype shifts through efficient modeling approaches, drawing insights from social-psychological theories and frameworks. | |

| Section 6 | Stereotype as the origin (Section 6.1) | Monitor and prevent self-fulfilling prophecies and stereotype threat; investigate whether LLMs and AI models exhibit personal biases similar to humans and understand underlying causes. |

| Implicit Bias (Section 6.2) | Conduct more research revealing implicit bias through measures like simulated implicit association tests and other psychological frameworks. | |

| Mitigation, Interpretability and Explainability (Section 6.3) | Removing Implicit Bias for mitigation; Anti-stereotypes for mitigation; Identify stereotype subspaces in LLMs; use explainability techniques (e.g., SHAP, LIME) to analyze model attributions through established theories; investigate impacts on original task efficiency. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).