1. Introduction

Headache following stroke is a common but poorly understood complication. Persistent headache may emerge after either ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, with recent reports estimating that 12–23% of stroke survivors experience ongoing headache symptoms [

1,

2]. Despite this prevalence, relatively little is known about the neural mechanisms underlying this form of post-stroke pain. There are no established treatments tailored to its pathophysiology, and clinical management is typically extrapolated from primary headache disorders [

1]. The lack of mechanistic insight has hindered the development of targeted interventions. One hypothesis that chronic post-stroke headache reflects altered patterns of brain connectivity, particularly in networks subserving pain, emotion, and salience.

A growing body of literature across chronic pain conditions points to brain network dysfunction as a key mechanism. Resting-state imaging studies in fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic low back pain have demonstrated abnormal functional connectivity between limbic structures such as the amygdala and insula and sensorimotor and prefrontal cortical regions [

3,

4]. These patterns suggest that persistent pain becomes entangled with affective and attentional systems [

5], reinforcing its salience and emotional charge. For instance, chronic pain has been associated with hyperconnectivity between primary somatosensory areas and default-mode and salience network regions, a pattern not observed in healthy individuals [

6]. This literature supports the idea that development of chronic pain involves sustained engagement of emotional and salience circuits, which may contribute to hypervigilance, distress, and in the absence of nociception.

The salience network, anchored in the anterior insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, plays a critical role in labeling sensory input with behavioral relevance. It is consistently activated during acute pain and supports the allocation of attentional resources and the generation of defensive responses. In chronic pain, however, the salience network appears dysregulated. Its hubs, particularly the insula, may become hyperactive or overly coupled with other brain areas, maintaining a heightened state of threat sensitivity even in the absence of immediate danger [

7]. This altered processing has been linked to increased pain sensitivity, emotional distress, and impaired top-down modulation [

8]. In the context of post-stroke headache, persistent engagement of the salience system could contribute to the maintenance of pain and interfere with recovery.

Interventions capable of modulating these circuits may help restore more adaptive patterns of connectivity. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), when applied to motor or prefrontal targets, has shown efficacy in reducing chronic pain syndromes by altering cortical excitability and reducing connectivity in limbic and sensorimotor circuits [

4]. Similarly, aerobic and structured exercise interventions have demonstrated neuroplastic effects in chronic pain populations [

9]. One study in adolescents with complex regional pain syndrome found that a three-week rehabilitation program reduced connectivity between the amygdala and motor regions, suggesting a normalization of pain-relevant networks [

10]. While both rTMS and exercise have been explored independently, few studies have combined them, and none to our knowledge have applied this approach to post-stroke headache.

The present pilot study aimed to explore changes in resting-state functional connectivity in individuals experiencing post-stroke headache following a combined rTMS and exercise intervention [

11]. We sought to characterize connectivity patterns before and after treatment, with particular interest in limbic, sensorimotor, and prefrontal circuits. Based on prior work, we hypothesized that participants would show elevated pre-treatment connectivity between the amygdala and insula and cortical regions associated with pain processing and modulation [

6,

12]. We further hypothesized that following intervention, these patterns would shift toward reduced connectivity, particularly in salience-linked circuits including amygdala to sensorimotor and insula to prefrontal pathways. This study provides early evidence that combined neuromodulation and exercise may be a viable approach for reducing pain-related connectivity and symptom burden in stroke survivors.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants were individuals in or near Birmingham, Alabama who had sustained a stroke and subsequently experienced persistent headache pain. Detailed inclusion criteria consisted of (1) confirmed diagnosis of stroke verified through neuroimaging or medical records, (2) persistent headache pain reported at least several times per week, and (3) no contraindications to undergoing MRI or rTMS or moderate-intensity exercise as assessed by medical screening. Participants were recruited from local stroke rehabilitation centers and neurology clinics. All participants provided written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the Birmingham VA’s Institutional Review Board (PROTOCOL #1600274).

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants.

|

Table 1. Demographics |

| Characteristic |

All participants (N = 5) |

| Age, mean (SD) |

61.9 (7.3) |

| Sex, N (%) |

|

| Male |

5 (100%) |

| Race, N (%) |

|

| Black / African American |

1 (20%) |

| White |

4 (80%) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) |

|

| Non-Hispanic |

5 (100%) |

Intervention Protocol

Participants completed 10 total sessions, each spaced up to 72 hours apart. Participants completed exercise and rTMS during the same session. Exercise occurred within 2 hour of each rTMS session to assess potential synergistic effects. Further procedural details are available in Lin et al. (2025).

Behavioral Inventories

Participants completed standardized self-report questionnaires to assess pain intensity, interference, and general health perception before and after the intervention. Pain outcomes were assessed weekly using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Outcomes were used descriptively and as covariates in analyses exploring associations between symptom change and neural connectivity.

TMS Protocol

Resting motor threshold (RMT) was defined as the minimum intensity needed to elicit ≥50 µV MEPs in the abductor pollicis brevis (APB) muscle at rest. In cases of bilateral infarcts, the hemisphere contralateral to the more symptomatic side was targeted. rTMS (MagStim) was delivered over the contralesional M1 hand area using a figure-of-eight coil. Each session consisted of 30 trains at 10 Hz (10 seconds per train, 20-second inter-train intervals), totaling 3,000 pulses at 90% RMT.

Exercise Protocol

Exercise followed a structured Moderate Intensity Interval Training (MIIT) protocol shown to improve neurocognitive function in older adults (Nocera et al., 2017). Cycling was performed on a Proform 325 CSX recumbent bike. Each session included a 10-minute warm-up at 30% of the individualized exercise target, followed by 25 minutes of alternating 1-minute intervals at moderate (60% peak watts, range 55–65%) and recovery intensity (45% peak watts, range 40–50%), and ended with a 10-minute cooldown at 30%. Heart rate reserve (HRR) was calculated using the Karvonen formula, with intensity monitored to maintain heart rate below 60% HRR. Vitals including blood pressure, heart rate, and Borg RPE were recorded pre- and post-exercise. Sessions were discontinued if participants exhibited tachycardia (>85% HRR), chest pain, shortness of breath, extreme fatigue, or blood pressure >200/115 mmHg.

MRI Protocol

Structural and functional scans were acquired on a Siemens MAGNETOM Prisma 3T MRI scanner. T1-weighted MPRAGE images (TR = 2400 ms, TE = 2.22 ms, TI = 1000 ms, flip angle = 8°, voxel size = 0.8 mm³, matrix = 320 × 300, no gap) were obtained using a 20-channel Head Neck coil. Resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) was acquired at baseline and one-month follow-up using a gradient echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 35.8 ms, flip angle = 60°, voxel size = 2.5 mm³, 52 slices, 300 volumes). Participants viewed a fixation cross during scanning and were asked to remain as still as possible.

Resting-State fMRI Analysis

Data were processed using CONN (v22.v2407) and SPM12. Preprocessing included realignment, slice timing correction, normalization to MNI space, segmentation, and spatial smoothing (8 mm FWHM). Outlier scans were flagged with ARtifact detection Tools (ART) and excluded from the reference signal. Denoising involved regression of 5 CSF/WM components (CompCor), motion parameters, outliers, session/task effects, and linear trends, followed by 0.008–0.09 Hz bandpass filtering.

First-Level and Group-Level Analyses

Seed-based and ROI-to-ROI functional connectivity was modeled using Fisher-transformed correlation coefficients across 164 HPC-ICA and Harvard-Oxford ROIs. First-level models were estimated using weighted GLMs. Paired t-tests were used to assess within-subject changes in connectivity between pre- and post-intervention sessions. In models exploring the relationship between connectivity changes and clinical outcomes, ANCOVA designs were implemented with changes in pain severity and interference scores included as covariates. All results were corrected for multiple comparisons using cluster-level inference based on Gaussian Random Field Theory, with a voxel-level threshold of p < 0.001 and a cluster-level false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using CONN, R (v4.5.0), and JMP Pro (v16.0).

3. Results

Behavioral Results

No adverse events occurred during the study. Self-reported pain severity and interference scores were collected at baseline and after the intervention. At baseline, participants reported moderate levels of pain, with a mean pain severity score of 4.4 (SE = 0.6, range = 2.3 to 7.3) and a mean pain interference score of 4.1 (SE = 1.0, range = 0 to 8.3). Across the study period, participants completed both pre- and post-intervention behavioral assessments. Mean pain severity decreased by 1.2 points (SE = 0.7), and pain interference decreased by 1.0 point (SE = 0.6). Individual change scores ranged from a maximum improvement of −3.5 to a slight worsening of +1.8 in pain severity, and −3.9 to +1.3 in pain interference (see

Table 3). These findings suggest modest reductions in headache-related burden following the combined rTMS and exercise protocol.

Imaging

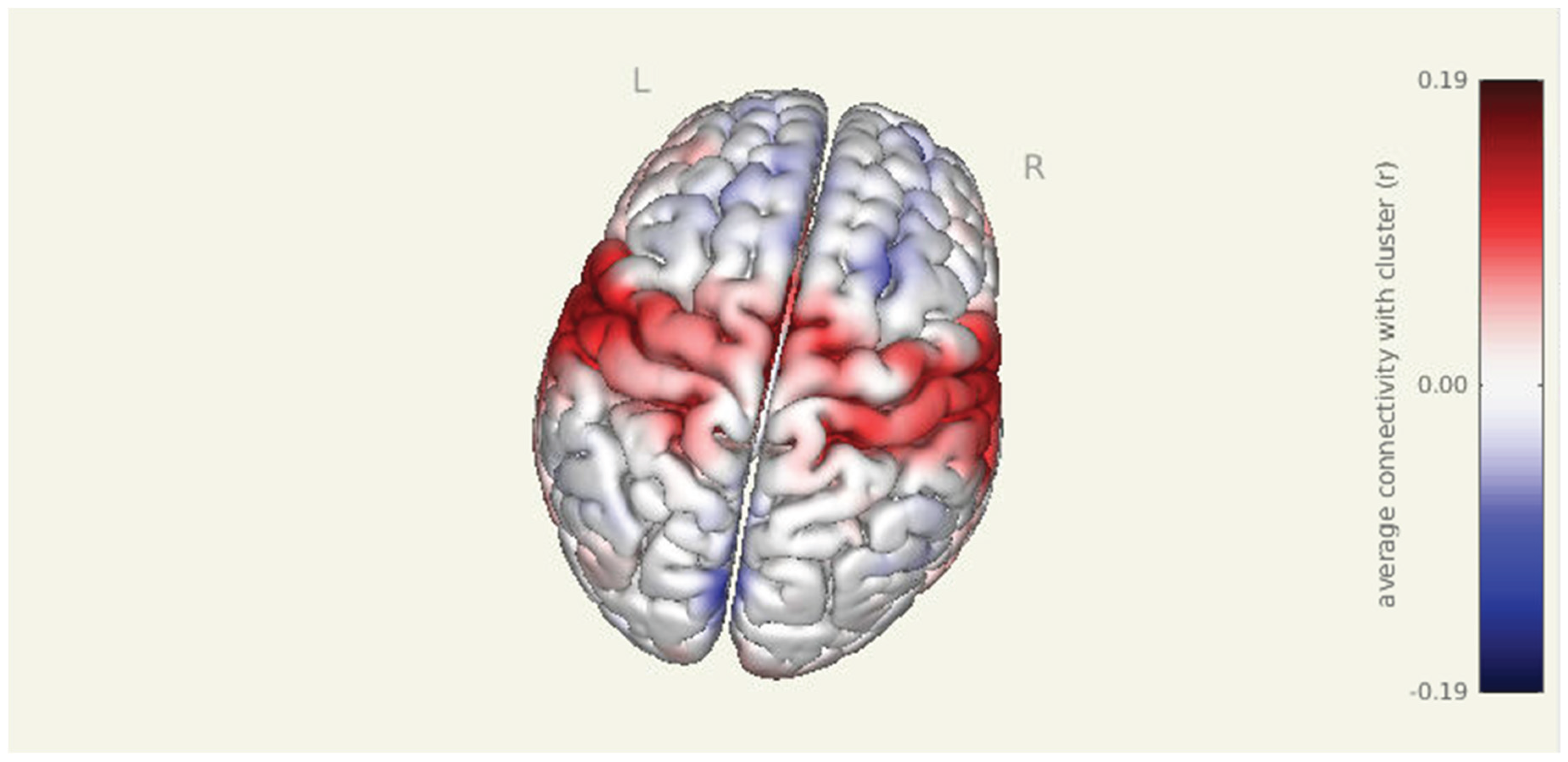

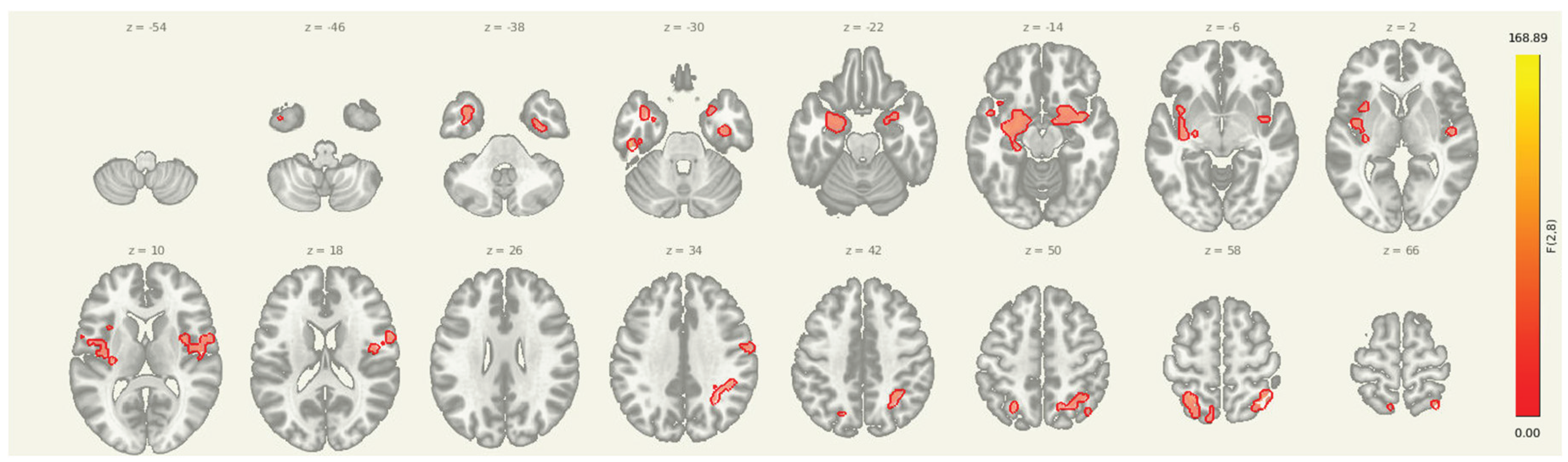

Prior to intervention, seed-to-voxel analysis from the amygdala revealed widespread connectivity with multiple cortical and subcortical regions. Significant clusters were observed in bilateral sensorimotor and frontal areas, including the left parahippocampal gyrus (MNI: -36, +06, -28; cluster size = 1396 voxels; p-FDR < 0.001), right superior parietal lobule (+38, -56, +60; 575 voxels; p-FDR < 0.001), right insular cortex (+46, -06, +16; 406 voxels; p-FDR < 0.001), and right thalamus (+18, +10, -16; 383 voxels; p-FDR < 0.001). Additional clusters were detected in the left superior parietal lobule, right cerebellum, and prefrontal cortex, further supporting elevated amygdala connectivity within regions implicated in sensory integration, emotional processing, and motor readiness.

Pre Amygdala Seed

Figure 1.

Pre-intervention amygdala connectivity map. A 3D surface rendering illustrates widespread resting-state functional connectivity from the amygdala seed at baseline. Significant clusters were observed in bilateral cortical and subcortical regions, including the left parahippocampal gyrus, right superior parietal lobule, right insular cortex, and right thalamus (all p-FDR < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Pre-intervention amygdala connectivity map. A 3D surface rendering illustrates widespread resting-state functional connectivity from the amygdala seed at baseline. Significant clusters were observed in bilateral cortical and subcortical regions, including the left parahippocampal gyrus, right superior parietal lobule, right insular cortex, and right thalamus (all p-FDR < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Multi-slice view of amygdala seed connectivity at pre-intervention. Displayed clusters correspond to those reported in

Table 2, showing significant resting-state connectivity between the amygdala and bilateral cortical regions, including sensorimotor and prefrontal cortices. All results are thresholded at p-FDR < 0.05 and shown in MNI space.

Figure 2.

Multi-slice view of amygdala seed connectivity at pre-intervention. Displayed clusters correspond to those reported in

Table 2, showing significant resting-state connectivity between the amygdala and bilateral cortical regions, including sensorimotor and prefrontal cortices. All results are thresholded at p-FDR < 0.05 and shown in MNI space.

Table 2.

Lesion characterization and T1/T2 contrast derived lesion burden (volume).

Table 2.

Lesion characterization and T1/T2 contrast derived lesion burden (volume).

|

Table 2. Stroke location. |

| |

Lesion Location |

Lesion Volume mm^3 |

| S01 |

Right middle cerebral artery infarcts in right frontal, parietal, temporal, insular, and posterior limb of internal capsule |

1093 |

| S02 |

Left frontoparietal subcortical white matter regions |

4517 |

| S03 |

Right paramedian parieto-occipital lobe |

864 |

| S04 |

Right paramedian medullary infarct |

9783 |

| S05 |

Left thalamic infarct |

3357 |

Table 3.

Resting-state clusters showing significant seed-to-voxel connectivity from the amygdala at pre-intervention. Coordinates are reported in MNI space. All clusters survived FDR correction and reflect baseline coupling between the amygdala and cortical regions implicated in pain and affective processing.

Table 3.

Resting-state clusters showing significant seed-to-voxel connectivity from the amygdala at pre-intervention. Coordinates are reported in MNI space. All clusters survived FDR correction and reflect baseline coupling between the amygdala and cortical regions implicated in pain and affective processing.

| 1. Cluster (MNI x, y, z) |

2. Size (voxels) |

3. p-FWE |

4. p-FDR |

5. Location |

| 6. -36, +06, -28 |

7. 1396 |

8. 0.000000 |

9. 0.000000 |

10. Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus (BA 47) |

| 11. +38, -56, +60 |

12. 575 |

13. 0.000000 |

14. 0.000000 |

15. Right Superior Parietal Lobule (BA 7) |

| 16. +46, -06, +16 |

17. 406 |

18. 0.000000 |

19. 0.000000 |

20. Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus (BA 44) |

| 21. +18, +10, -16 |

22. 383 |

23. 0.000000 |

24. 0.000000 |

25. Right Amygdala |

| 26. -26, -52, +58 |

27. 249 |

28. 0.000003 |

29. 0.000001 |

30. Left Precuneus (BA 7) |

| 31. +36, -10, -32 |

32. 100 |

33. 0.006426 |

34. 0.001522 |

35. Right Fusiform Gyrus (BA 37) |

| 36. +60, -04, +38 |

37. 88 |

38. 0.013357 |

39. 0.002721 |

40. Right Precentral Gyrus (BA 6) |

| 41. -48, -24, -30 |

42. 57 |

43. 0.101819 |

44. 0.019011 |

45. Left Fusiform Gyrus (BA 37) |

| 46. -08, -62, +60 |

47. 53 |

48. 0.134057 |

49. 0.022651 |

50. Left Superior Parietal Lobule (BA 7) |

Amygdala SEED PRE>POST

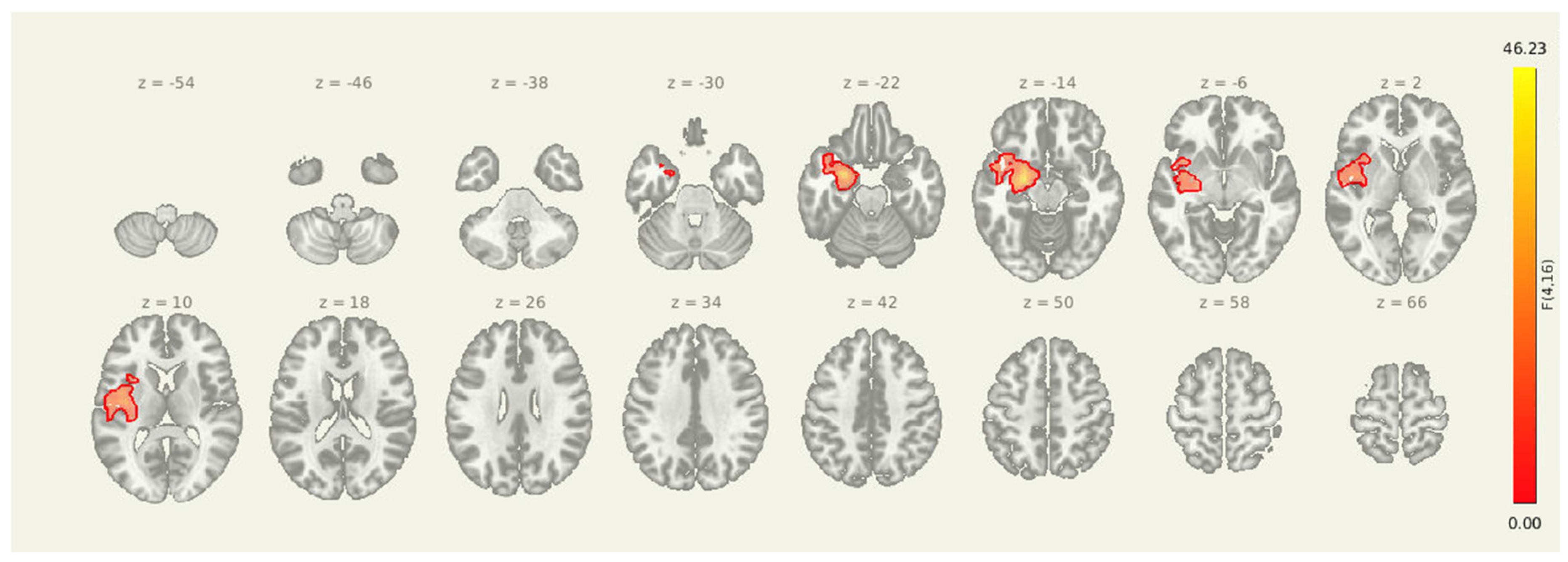

Following the intervention, seed-to-voxel analysis revealed significantly greater amygdala connectivity at the pre-intervention timepoint compared to post-intervention in two clusters. The first was located in the left postcentral gyrus and somatosensory association area (MNI: +06, -38, +34; cluster size = 382 voxels; p-FDR = 0.0107), and the second was centered in the right superior frontal gyrus (MNI: +22, +22, +54; cluster size = 315 voxels; p-FDR = 0.0171). These results suggest a reduction in amygdala coupling with both sensorimotor and prefrontal regions after the combined rTMS and exercise intervention, consistent with decreased engagement of limbic-driven pain and vigilance networks.

Figure 3.

Seed-to-voxel connectivity reductions from the amygdala following intervention. Significant clusters reflect greater connectivity at pre-intervention compared to post-intervention (PRE > POST), including regions in the left postcentral gyrus and right superior frontal gyrus. Results are thresholded at p-FDR < 0.05 and shown in MNI space.

Figure 3.

Seed-to-voxel connectivity reductions from the amygdala following intervention. Significant clusters reflect greater connectivity at pre-intervention compared to post-intervention (PRE > POST), including regions in the left postcentral gyrus and right superior frontal gyrus. Results are thresholded at p-FDR < 0.05 and shown in MNI space.

Table 4.

Clusters showing significantly reduced connectivity with the amygdala seed following the combined rTMS and exercise intervention. All results survived FDR correction.

Table 4.

Clusters showing significantly reduced connectivity with the amygdala seed following the combined rTMS and exercise intervention. All results survived FDR correction.

| 51. Cluster (MNI x, y, z) |

52. Size (voxels) |

53. p-FWE |

54. p-FDR |

55. Location |

| 56. +06, -38, +34 |

57. 382 |

58. 0.010472 |

59. 0.010656 |

60. Left Postcentral Gyrus (BA 1/2) |

| 61. +22, +22, +54 |

62. 315 |

63. 0.033151 |

64. 0.017062 |

65. Right Superior Frontal Gyrus (BA 8) |

Insula Seed PRE>POST

For the insula seed, pre-intervention connectivity was significantly greater than post-intervention in multiple regions: the left inferior frontal gyrus (MNI: -48, +12, -02; cluster size = 266 voxels; p-FDR < 0.001), the right inferior frontal gyrus (+48, +10, +00; 256 voxels; p-FDR < 0.001), and the left ventral striatum/putamen (-28, +02, +08; 65 voxels; p-FDR < 0.001). These regions are commonly involved in emotional processing, interoceptive integration, and motor preparation, and the observed reductions in connectivity suggest decreased insula-driven engagement of salience and affective-motor circuits following the intervention.

Table 5.

Post-intervention reductions in connectivity from the insula seed to frontal and striatal regions. All clusters reported here were significant at p-FDR < 0.001.

Table 5.

Post-intervention reductions in connectivity from the insula seed to frontal and striatal regions. All clusters reported here were significant at p-FDR < 0.001.

| 66. Cluster (MNI x, y, z) |

67. Size (voxels) |

68. p-FWE |

69. p-FDR |

70. Location |

| 71. -48, +12, -02 |

72. 266 |

73. < 0.001 |

74. < 0.001 |

75. Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus |

| 76. +48, +10, +00 |

77. 256 |

78. < 0.001 |

79. < 0.001 |

80. Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus |

| 81. -28, +02, +08 |

82. 65 |

83. < 0.001 |

84. < 0.001 |

85. Left Ventral Striatum / Putamen |

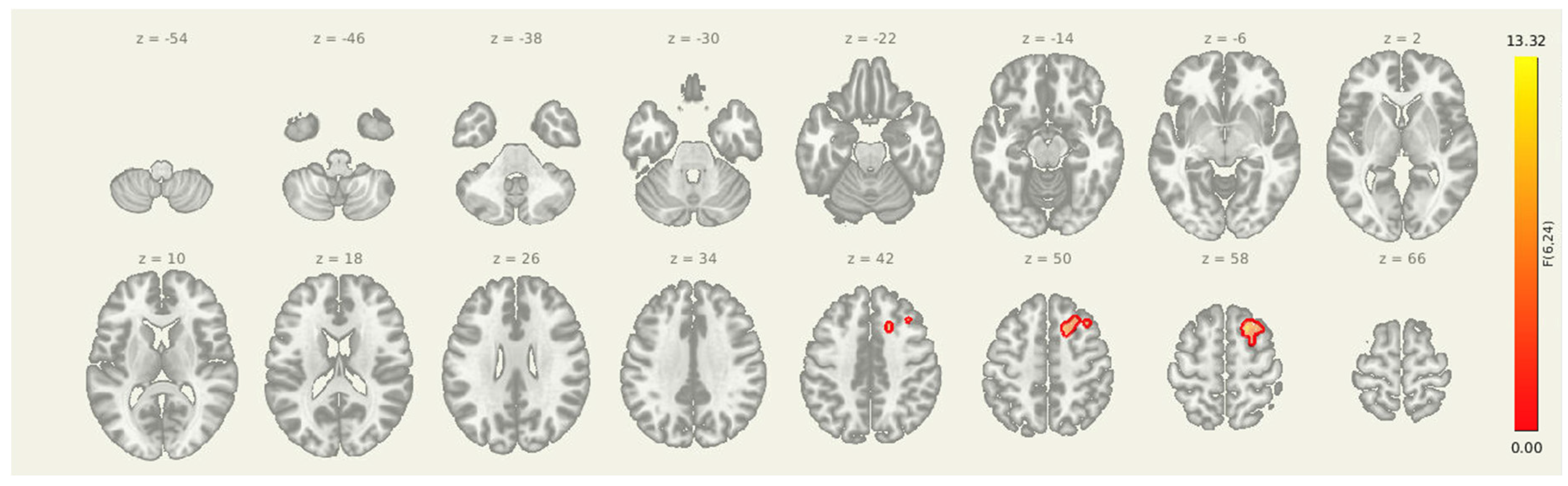

Amygdala-Insula-Thalamus Seed

Figure 4.

Post-intervention reductions in connectivity from limbic seed regions. Significant decreases in seed-to-voxel connectivity were observed from the amygdala, insula, and thalamus following the intervention. Clusters included sensorimotor, frontal, and subcortical regions. Results are thresholded at p-FDR < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Post-intervention reductions in connectivity from limbic seed regions. Significant decreases in seed-to-voxel connectivity were observed from the amygdala, insula, and thalamus following the intervention. Clusters included sensorimotor, frontal, and subcortical regions. Results are thresholded at p-FDR < 0.05.

Table 6.

Post-intervention reductions in connectivity from the amygdala-insula-thalamus seed. The cluster identified reflects decreased coupling between the amygdala and the right superior frontal gyrus.

Table 6.

Post-intervention reductions in connectivity from the amygdala-insula-thalamus seed. The cluster identified reflects decreased coupling between the amygdala and the right superior frontal gyrus.

| 86. Cluster (MNI x, y, z) |

87. Size (voxels) |

88. p-FWE |

89. p-FDR |

90. Location |

| 91. +20, +18, +56 |

92. 133 |

93. 0.009064 |

94. 0.006499 |

95. Right Superior Frontal Gyrus |

Seeding from amygdala-insula-thalamus Seed-to-voxel analyses revealed a significant post-intervention reduction in connectivity from the insula, amygdala, and thalamus to a cluster in the right superior frontal cortex (MNI coordinates: +20, +18, +56; cluster size = 133 voxels; p-FDR = 0.0065). These results suggest that improved prefrontal oversight may be a key mechanism through which the intervention alters pain-related brain dynamics in individuals with post-stroke headache.

4. Discussion

This pilot study examined changes in resting-state functional connectivity and self-reported pain symptoms following a combined rTMS and aerobic exercise intervention in individuals with persistent post-stroke headache. At baseline, participants demonstrated elevated connectivity between limbic regions (amygdala, insula) and cortical areas involved in salience detection, motor preparation, and emotional regulation. These connectivity patterns are consistent with prior reports in chronic pain populations and suggest an over-engaged limbic–sensorimotor system in the maintenance of post-stroke headache. Following the intervention, these networks showed measurable reductions in connectivity. In parallel, participants reported modest reductions in pain severity and interference, supporting the possibility that the intervention may have induced both neural and behavioral effects [

13].

The amygdala plays a key role in the emotional processing of pain and is commonly hyperactive in chronic pain [

14]. At baseline, stronger amygdala coupling with sensorimotor and prefrontal regions likely reflected persistent limbic engagement with pain perception and threat monitoring [

12,

15]. The observed decoupling after treatment may represent a downregulation of this emotional amplification. Prefrontal regions such as the superior frontal gyrus are involved in top-down modulation of affect and pain, and their pre-intervention coupling with the amygdala may indicate a compensatory but overloaded regulatory system. Reduced fronto-limbic connectivity has been linked to improved pain modulation [

16,

17], and our findings are consistent with this model.

Changes in insula connectivity suggest a shift in salience attribution and interoceptive prediction. Before treatment, participants showed heightened coupling between the insula and inferior frontal cortex, a network that often shows hyperconnectivity in chronic pain [

18,

19]. These patterns may reflect excessive attention to bodily threat cues. The insula is integral to the salience network and plays a role in anticipating and appraising internal states. Following the intervention, this connectivity was reduced, possibly reflecting decreased hypervigilance and a more normalized allocation of cognitive resources. The insula also showed reduced coupling with the ventral striatum, a region involved in reward processing and motivational-affective aspects of pain [

20,

21]. Given that exercise activates reward pathways, it is plausible, albeit speculative, that this change reflects an improved balance between pain and motivational circuitry [

14].

These network-level changes may also support enhanced descending pain inhibition. The prefrontal cortex and insula interface with brainstem structures involved in suppressing ascending pain signals [

22]. In chronic pain, hyperconnectivity in limbic and salience networks may interfere with these pathways [

23]. Our observed reductions in fronto-limbic and insula-frontal connectivity may reflect improved capacity for pain modulation, although this was not directly measured.

Alternatively, reduced connectivity may reflect the disengagement of previously overactive circuits or a breakdown in compensatory mechanisms that regulate affective and somatosensory input, especially in the context of chronic stroke. Prior studies have shown that in some clinical populations, decreased connectivity can also signal maladaptive disintegration of network coherence rather than recovery[

24,

25]. Further studies using task-based paradigms or additional neurophysiological markers are needed to clarify whether these changes represent adaptive modulation or a loss of compensatory engagement.

Behaviorally, participants reported mean reductions of 1.2 points in pain severity and 1.0 point in pain interference over the course of the study. While modest, these changes occurred over a relatively brief intervention window and in a sample with moderate baseline headache burden. These findings are clinically meaningful and support the relevance of the imaging results. Moreover, they suggest that network-level modulation may track with improvements in functional outcomes, even in a small pilot sample. The exciting addition of more standardized pain treatment protocols with rTMS warrants considerable study, particularly with fMRI[

26].

This study is the first to report changes in brain connectivity following a combined rTMS and exercise intervention in post-stroke headache. Up to a quarter of stroke survivors report chronic headache, yet clinical guidance is limited and often adapted from unrelated headache populations [

27]. Our findings suggest that engaging both central and peripheral systems through a multimodal, non-pharmacologic approach may modify pain-related brain networks. Both rTMS and structured exercise are known to be safe in post-stroke contexts and have demonstrated independent effects on pain and mood [

14]. This work provides early support for integrating these modalities to target persistent post-stroke headache.

Limitations

As a pilot study, our sample size was small, and findings should be interpreted with caution, particularly given the absence of a sham stimulation protocol (potentially implicating placebo effects). Additionally, study MRI sample points (one-month follow-up) hamper conclusions about the temporal specificity of effects. Although standard motion correction and denoising procedures were applied (via AFNI and CONN toolbox), neuroimaging data from clinical populations can still be affected by residual artifacts. Despite these limitations, the observed changes offer a foundation for future studies and support the feasibility of targeting pain-related networks in stroke survivors.

Conclusions

These data show that a combined exercise and rTMS intervention resulted in decreased pain self-report, consistent with resting-state imaging data, indicating potential top-down modulation of headache pain. Additional study is warranted to isolate mechanisms of neural changes post-intervention.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions Statement: K.M.M. (Keith McGregor): Conceptualization, methodology, writing - original draft. C.L. (Chen Lin): Supervision, Conceptualization, funding acquisition, data collection, formal analysis, visualization, writing - review & editing. S.K.S. (Sarah Katherine Sweatt): Analysis, writing - review & editing. A.N. (Ayat Najmi): Analysis, review & editing. M.H. (Marshall Holland): Consultation, review & editing. J.N. (Joe Nocera): Conceptualization, writing - review & editing. C.J.M. (Charity Morgan): Statistical analysis, data interpretation, writing - review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by Pilot Award I21 RX003612 from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service (PI: Lin). Dr. Lin is also supported by VA Career Development Award A IK2 CX002104.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Birmingham VA’s Institutional Review Board (PROTOCOL #1600274).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the Birmingham VA’s Institutional Review Board (PROTOCOL #1600274). This study meets the WHO definition of a clinical trial and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04672044.

Data Availability Statement

Data is the property of the United States Government. Access to data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

AI software (Ollama – Llama 3.1 model) was used to assist with copyediting and proofreading of the manuscript. This included grammar refinement and minor phrasing suggestions. No AI software was used for content generation, data analysis, or interpretation. All AI-generated suggestions were manually reviewed and approved by the lead author prior to incorporation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BPI |

Brief Pain Inventory |

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

| TMS |

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| rTMS |

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| RMT |

Resting Motor Threshold |

| rsfMRI |

Resting State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| HRR |

Heart Rate Reserve |

| FDR |

False Discovery Rate |

| FWE |

Family Wise Error |

| MNI |

Montreal Neurological Institute |

References

- Lebedeva, E. R. et al. Persistent headache after first-ever ischemic stroke: clinical characteristics and factors associated with its development. Journal of Headache and Pain 23, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Harriott, A. M., Karakaya, F. & Ayata, C. Headache after ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-Analysis. Neurology vol. 94 Preprint at (2020). [CrossRef]

- Terrasa, J. L. et al. Anterior Cingulate Cortex Activity During Rest Is Related to Alterations in Pain Perception in Aging. Front Aging Neurosci 13, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Argaman, Y. et al. Clinical Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Motor Cortex Are Associated With Changes in Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Patients With Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Journal of Pain 23, (2022).

- Lindsay, N. M., Chen, C., Gilam, G., Mackey, S. & Scherrer, G. Brain circuits for pain and its treatment. Science Translational Medicine vol. 13 Preprint at (2021). [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D., Vanneste, S., Smith, M. & Adhia, D. Pain and the Triple Network Model. Frontiers in Neurology vol. 13 Preprint at (2022). [CrossRef]

- Schimmelpfennig, J., Topczewski, J., Zajkowski, W. & Jankowiak-Siuda, K. The role of the salience network in cognitive and affective deficits. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience vol. 17 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Van Ettinger-Veenstra, H. et al. Chronic widespread pain patients show disrupted cortical connectivity in default mode and salience networks, modulated by pain sensitivity. J Pain Res 12, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K. L. et al. Exercise training augments brain function and reduces pain perception in adults with chronic pain: A systematic review of intervention studies. Neurobiology of Pain vol. 13 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- De Zoete, R. M. J., Chen, K. & Sterling, M. Central neurobiological effects of physical exercise in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. BMJ Open 10, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lin, C., Morgan, C. J., Fortenberry, E. L. S., Androulakis, X. M. & McGregor, K. The safety and feasibility of a pilot randomized clinical trial using combined exercise and neurostimulation for post-stroke pain: the EXERT-Stroke study. Front Neurol 16–2025, (2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. et al. Altered functional connectivity of amygdala underlying the neuromechanism of migraine pathogenesis. Journal of Headache and Pain 18, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Lai, J., Harrison, R. A., Plecash, A. & Field, T. S. A Narrative Review of Persistent Post-Stroke Headache – A New Entry in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd Edition. Headache 58, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Senba, E. & Kami, K. Exercise therapy for chronic pain: How does exercise change the limbic brain function? Neurobiology of Pain 14, (2023).

- Jiang, Y. et al. Perturbed connectivity of the amygdala and its subregions with the central executive and default mode networks in chronic pain. Pain 157, (2016). [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M. & Messina, R. The Chronic Migraine Brain: What Have We Learned From Neuroimaging? Frontiers in Neurology vol. 10 Preprint at (2020). [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C. J. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain vol. 152 Preprint at (2011). [CrossRef]

- Coppieters, I., Cagnie, B., v, R., Meeus, M. & Timmers, I. Enhanced amygdala-frontal operculum functional connectivity during rest in women with chronic neck pain: Associations with impaired conditioned pain modulation. Neuroimage Clin 30, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Labrakakis, C. The Role of the Insular Cortex in Pain. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 24 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Park, S. H., Baker, A. K., Krishna, V., Mackey, S. C. & Martucci, K. T. Evidence of Intact Corticostriatal and Altered Subcortical-striatal Resting-state Functional Connectivity in Chronic Pain. J Pain 23, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Park, S. H., Baker, A. K., Krishna, V., Mackey, S. C. & Martucci, K. T. Altered resting-state functional connectivity within corticostriatal and subcortical-striatal circuits in chronic pain. Sci Rep 12, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ong, W. Y., Stohler, C. S. & Herr, D. R. Role of the Prefrontal Cortex in Pain Processing. Molecular Neurobiology vol. 56 Preprint at (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H. et al. Impaired insula functional connectivity associated with persistent pain perception in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. PLoS One 12, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Nie, H., Liu, C. & Chen, J. Disrupted brain network efficiency and decreased functional connectivity in multi-sensory modality regions in male patients with alcohol use disorder. Front Hum Neurosci 12, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hoekzema, E. et al. An independent components and functional connectivity analysis of resting state FMRI data points to neural network dysregulation in adult ADHD. Hum Brain Mapp 35, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur, J. P., Mussigmann, T., Bapst, B. & Bardel, B. From depression to chronic pain: Accelerated protocol and resting-state brain imaging targeting to personalize rTMS therapy. Clinical Neurophysiology vol. 176 Preprint at (2025). [CrossRef]

- Chan, M. & Thaler, A. Post-stroke Headache. Current Pain and Headache Reports vol. 27 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).