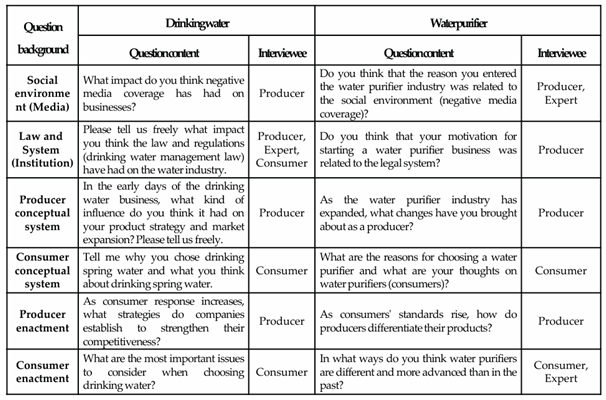

4. Results and Analysis

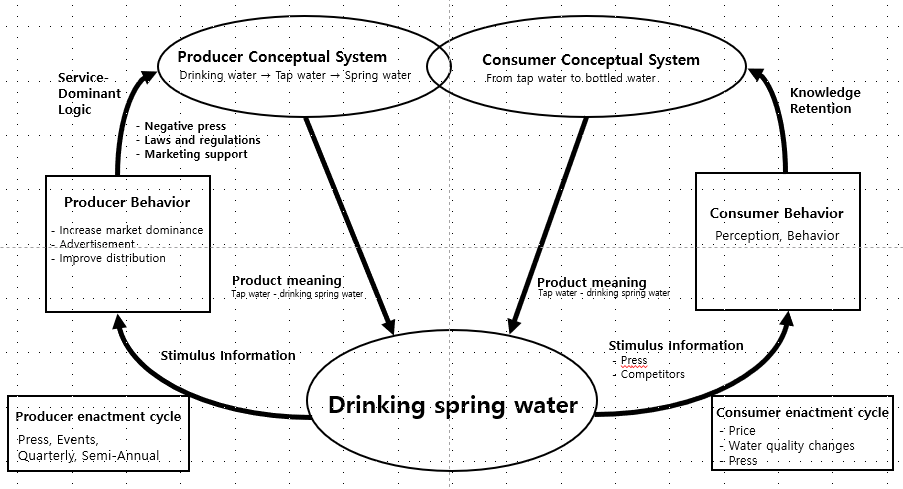

Overview: The results are organized around the five hypotheses (H1–H5) that trace the socio-cognitive dynamics in the water product markets. For each hypothesis, we first outline the key findings and whether the hypothesis was supported, then present illustrative evidence from the interviews, and finally interpret the findings in light of socio-cognitive theory and sustainability considerations. We differentiate, where relevant, between the bottled water market (often locally termed “drinking spring water”) and the water purifier market, as both followed the hypothesized dynamics but with notable differences in outcomes.

4.1. External Shocks Reshape Producer Conceptual Systems (H1)

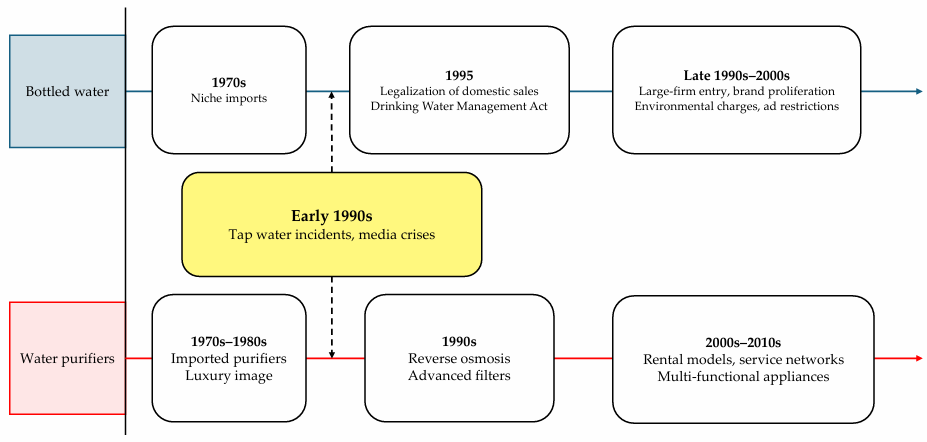

H1 posited that negative media coverage and regulatory changes altered producers’ conceptual frames, effectively catalyzing the bottled water and purifier markets. Our findings strongly support this hypothesis. Virtually all producer-side interviewees referenced one or more external “shocks” in the early 1990s as turning points.

In the bottled water case,

a manager recalled, “After the phenol contamination news in 1991, people here were desperately looking for clean water. We, as a food company, suddenly saw ‘water’ as something we could sell, which was new.” At that time, selling drinking water was not an obvious business; water was generally considered a free public utility. But the intense media attention to tap water pollution (thousands of stories appeared in 1991–92) [

8] created a new public consciousness that potable water could not be taken for granted.

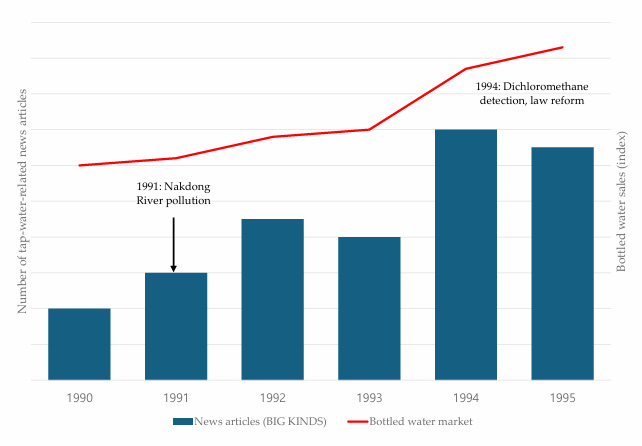

Figure 4 illustrates this trend: spikes in tap-water-related news coverage in 1991 and 1994 coincided with surging interest in bottled water. The 1994 detection of carcinogens in Seoul’s tap water supply and the subsequent passage of the Drinking Water Management Act were especially pivotal [

8].

Several entrepreneurs entered the bottled water industry around 1994–1996, citing the law change that legalized domestic production: “When the government allowed local bottling in ’95, it was a green light. Before that, selling water felt like a grey market; after that, it became a legitimate business focused on safety.” Thus, policy and media worked in tandem to alter producers’ mindset – from viewing water as a low-value commodity to seeing “safe drinking water” as a marketable product category requiring formal operations and marketing.

For water purifier firms, H1 held as well, though the mechanism was slightly different. Early purifier producers (1980s) were often importers or sellers of luxury filtration units to affluent homes. They reported that negative environmental news in the early 1990s broadened their target market: “Suddenly, middle-class families were asking about purifiers. The news made everyone worry – even if they couldn’t afford it, they were curious.” One long-time engineer noted that around 1990, we thought only fancy hotels and rich people would buy purifiers. But after those tap water scares, our concept changed – we started thinking every household might need one.” This conceptual broadening – imagining the purifier as a mass-market necessity – was a direct response to public outcry about water quality.

At the same time, regulatory scrutiny increased. In the mid-90s, the government and industry associations established certification systems for purifiers (e.g., the WaterMark in Korea) to address quality inconsistencies.

One CEO recounted being essentially forced by circumstances to improve product standards: “There were reports of sub-standard filters leaching chemicals. It became an existential issue – either we improve and prove our purifiers are safe, or the whole industry could collapse under distrust.” Here we see Bandura’s reciprocal causation: environmental events (contamination) influenced producers’ beliefs and behavior (invest in better filters, seek certifications), which in turn were aimed at altering the environment of consumer perception (restoring trust) [

3,

4].

In summary, H1 is confirmed by evidence that external shocks were the impetus for producers’ strategic pivots. Negative media coverage effectively delegitimized the tap water status quo and legitimized new water products in the eyes of both producers and regulators. As a result, producers reconceived their role: bottled water companies emerged to provide what the public system ostensibly could not (reliable purity), and purifier companies shifted from niche luxury sellers to purveyors of a household utility. These shifts mark the first stage of socio-cognitive change, setting the stage for the new markets. In both cases, a common theme was distrust in public infrastructure – producers described riding a wave of consumer distrust that was not of their making, but which opened a market window. This highlights a nuanced point: while the initial push came from outside (media, policy), producers’ own cognitive frameworks (what they believed was possible or acceptable to market) had to adapt significantly. One might say that Korean producers had to unlearn the notion that “nobody sells water in a bottle” or “home water is the government’s concern” – they developed new schemas wherein providing trust became central to their product mission.

4.2. Producer Conceptual Change Drives Product/Strategy Innovation (H2)

Under H2, we expected that once producers’ conceptual systems changed, this would manifest in concrete changes in product meanings and in the strategies producers advanced. The data show clear evidence of this, as producers in both markets undertook a flurry of innovations and repositioning efforts following the watershed moments of the early 90s. Essentially, producers asked: “If people now want safe water, how do we deliver and symbolize that?” – leading to new product features and marketing narratives.

In the bottled water market, the mid to late 1990s saw companies redefine what bottled water stood for. Initially, domestic bottled water brands emphasized source purity and naturalness. One pioneer brand manager stated, “We chose our spring source in a remote mountain and made that our story – that this water is nature’s gift, untouched.” This narrative was a deliberate strategy to differentiate bottled water from municipal water (which was associated with chemical treatment). By tying the product meaning to pristine nature, producers gave bottled water an aura of health and purity that tap water lacked.

Another strategic innovation was in distribution and packaging: traditionally, beverages were sold through retailers or distributors, but one interviewee noted, “We had to get bottled water out everywhere – supermarkets, new delivery services, even online by the 2000s – so that it’s always available when tap trust falters.” This expansion of channels (from corner-store sales to bulk delivery) indicated that producers were reframing bottled water as a daily necessity. They also experimented with package sizes (introducing 2L family-size bottles, 500mL on-the-go bottles) to integrate bottled water into various consumption contexts, effectively broadening its meaning from a travel or emergency item to an everyday hydration source.

Producers also innovated in branding and product differentiation. As competition grew in the 2000s (many new brands entered after 1995), companies started to imbue their water with extra attributes – the emergence of “functional water” lines is notable. For example, some brands added minerals and marketed the water as enhancing fitness or beauty. Internally, producers came to see themselves not just as water providers, but as part of the health/wellness industry. One company began an OEM (original equipment manufacturing) arrangement to supply store-brand bottled water to a major retailer, citing that “even supermarkets wanted their own trusted water brand – it became like a staple food.” Such OEM deals were also a strategic response to supply shortages (demand sometimes outstripped the capacity of small producers). This confirms what H2 anticipated: producers’ recognition of high demand and the trust premium led them to adopt innovative solutions, such as OEMs and new logistics, to ensure market coverage.

As one executive summarized, “We changed everything – sourcing, production volume, marketing – all because suddenly water was a valuable product. We had to build credibility and stand out.” These changes in practice reflect a shift in the product's meaning from the producer's perspective: water was no longer “just water”; it was now a branded good, with purity, health, and trustworthiness as the core selling points.

In the purifier market, producer-driven changes were equally significant after the 1990s. Perhaps the most critical change was a move toward a service-oriented model. Traditionally, appliance makers sold purifiers as one-off products; however, as producers realized consumers were concerned about maintenance and filter hygiene (a theme that emerged strongly in our consumer interviews), they pivoted to a rental model with regular service visits. This innovation fundamentally changed the meaning of owning a purifier: it was no longer just a machine under your sink, but a service subscription that ensured continuous clean water. One veteran purifier company director described the internal conceptual shift: “We stopped thinking of ourselves as selling devices in boxes. We started thinking we’re selling clean water as a service – the machine is just the means.” This aligns with H2: the producer’s concept of the product expanded to include service quality, which was then built into the product offering. As a result, by the early 2000s, many Korean purifier firms had large fleets of service personnel (often called “cody” or “coordinator” visits) who regularly exchanged filters and sanitized units in homes. This strategy both added tangible value and also signaled to consumers that the company is partnering in their health – a message very different from a simple retail transaction.

Technologically, purifier manufacturers doubled down on filtration innovation. After recognizing that consumer trust was fragile, companies invested in R&D to develop multi-stage filters, UV sterilizers, and indicators that show water quality, all to reinforce the product's meaning of “safety and high-tech reliability.” One engineer recounted how the design of purifiers changed: “Earlier models were under-sink and hidden. Around 2000, we made countertop models with digital displays – it would show, e.g., TDS (total dissolved solids) levels, filter life, so that customers feel in control and informed.” This design shift made the purifier a visible part of the kitchen, arguably to normalize it as an everyday appliance and as a status symbol of a health-conscious home. Indeed, producers began advertising purifiers not only for health but also for convenience and a modern lifestyle (some ads featured stylish purifiers that matched kitchen decor). Thus, the product’s meaning was enriched: it was about health, but also about modernity and care for one’s family.

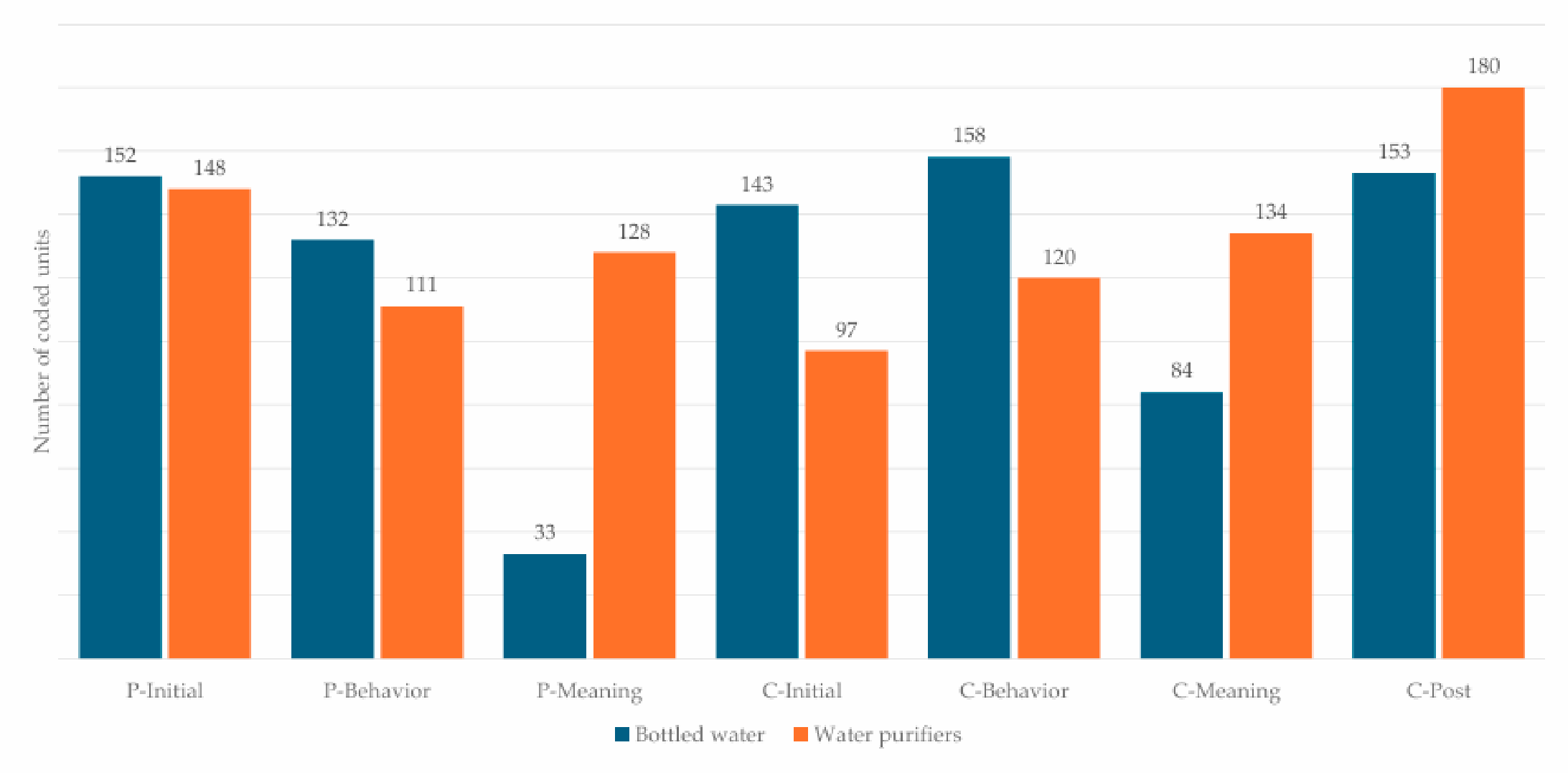

Producers in both markets emphasized “trust/safety” most frequently in interviews, reflecting their focus on product credibility. Water purifier producers uniquely stressed “service” (rental and maintenance), while bottled water producers more often mentioned “branding” and “environmental impact.” Consumers in both markets frequently discussed “health” and “risk,” aligning with producers’ trust narratives, but had fewer mentions of “sustainability” unless prompted.

In conclusion, H2 is affirmed: once producers reconceptualized the situation (H1), they proactively altered product attributes, business models, and messaging to redefine their product’s meaning in the marketplace. They internalized that their role was to deliver not just water but also reliable safety, convenience, and, eventually, sustainability. This stage can be thought of as the proactive phase of market formation – the supply side innovations that set the tone for how consumers would next react. Notably, these producer innovations laid the groundwork for educating consumers. By introducing, for example, scheduled service visits or eco-friendly packaging, producers implicitly taught consumers new expectations (e.g., “your drinking water provider should take care of you continuously” or “bottled water should be pure and green”). H3 deals with how consumers responded to and learned from these changes, which we turn to next.

4.3. Producer-Driven Changes Influence Consumer Conceptual Systems (H3)

H3 proposed that changes in product meaning instigated by producers would subsequently shape consumers’ initial conceptual frameworks – essentially, consumers would start to think differently about water and their choices. Our findings support this, showing a marked evolution in consumer perceptions and decision criteria over time, much of which can be traced to producer and media influences. In the interviews, consumers often framed their shift in behavior in terms of new attributes they came to value, many of which mirror producers’ marketing emphases.

One clear example is how quality differentiation became a consumer concept. In the 1980s, an average Korean consumer had a binary view: tap water (boiled or not) versus boiled barley water or some traditional beverage. There was no notion of gradations in drinking water quality. By the late 1990s, however, consumers spoke of choosing water based on mineral content, taste, source, or brand reputation. As one consumer put it, “Not all bottled waters are the same – Jeju volcanic water tastes smooth, and I prefer it for health minerals.” This kind of statement reflects a consumer conceptual system that now includes product distinctions and personal preferences, something that did not exist a decade prior. The emergence of branded bottled waters and their marketing (e.g., highlighting a calcium-rich mountain spring vs. an oxygenated water) educated consumers that water could have various qualities.

Surveying our consumer interviews, we found frequent references to terms like “clean,” “fresh,” “natural taste,” “minerals,” and brand names, indicating that consumers had absorbed the producers’ messaging about what makes water “better.” One housewife mentioned she switched brands after reading a brochure about one water having lower sodium – a detail that suggests quite sophisticated conceptual engagement, arguably seeded by producers’ information campaigns.

Consumers also developed concepts of risk and trust aligned with those addressed by producers. Initially, consumer mistrust was directed broadly at tap water (government-provided water). Over time, however, consumers learned to differentiate among alternative sources of trust. For instance, some consumers expressed strong trust in certain bottled water brands (often those that emphasized quality testing and source purity in ads), while remaining skeptical of lesser-known brands or even of water purifier efficacy. A middle-aged interviewee’s comment illustrates this: “I only buy Seoksu brand water because I know they test every batch. Cheaper brands, I worry they fill it from some tap.” Here, the consumer’s conceptual model has expanded: rather than “tap water = untrustworthy, bottled water = trustworthy,” she differentiates within bottled waters based on perceived rigor – a nuance likely shaped by marketing and publicized quality certifications (some leading brands advertised their ISO quality certifications, which evidently stuck in consumers’ minds).

Similarly, with purifiers, early on, many consumers either trusted or distrusted the idea of a purifier wholesale. But by the 2000s, consumers would say things like, “I trust Company A’s purifier because their service man comes regularly, but I wouldn’t trust a purifier if nobody maintains it.” This shows that the consumer's conceptual system now includes the notion of maintenance/service as part of trust, which the service model innovation producers directly introduced.

Our coding analysis confirms that consumers began valuing service and convenience factors, especially for purifiers. In interviews from the late 2010s, new purifier customers frequently cited factors such as service response time, filter replacement frequency, and rental costs as reasons for their purchase decisions. These are not water quality attributes per se, but rather aspects of the product meaning that were created by producer strategy (the service model). In contrast, earlier consumers (late 90s) who bought purifiers often talked only about the device’s filtration ability or cost. The shift suggests that consumers learned to see a purifier not just as a machine but as an ongoing service relationship – precisely the reframing that producers intended. This learning likely occurred through experience (having a service agent visit and finding it valuable) and through word of mouth (neighbors telling each other how convenient renting is). It underscores a broader point: consumer socialization into new product meanings. Families that adopted bottled water or purifiers often influenced relatives and friends by sharing their experiences, thereby diffusing the new concepts further. One expert noted in her interview, “By the early 2000s, people talked about water quality at home gatherings, comparing notes on brands and methods. That was unheard of a decade prior.” Such social discourse is a sign that the cognitive category of drinking water solutions had firmly entered consumer culture, with a refined set of attributes to debate (e.g., brand X vs Y, purifier vs delivered water, etc.).

Another dimension of consumer conceptual change is the broadening of the category set they consider. Initially, tap water was the only category for most Koreans. As these markets emerged, consumers came to see “what is water for drinking” as a multi-category space: tap water, boiled tap water, bottled water, purifier water, and even various functional or flavored waters. Our interviews with consumers who lived through the transition revealed how their household practices changed. Many described a progression such as: in the 1980s they drank tap or barley tea; in the late 90s they started regularly buying bottled water for outings or children; by the 2000s they installed a purifier at home for cooking and drinking, but still bought bottled water for travel; in recent years some even subscribe to both a purifier service and buy specialty bottled waters (for mineral content or sparkling water for example). This indicates that consumers did not simply replace one source with another; they diversified and assigned different meanings to each. One respondent said, “We use the purifier daily for convenience, but I buy Jeju spring water for my baby because I trust that source more for purity.” This kind of reasoning shows a highly evolved conceptual framework in which multiple product meanings coexist: purifier water = convenient and reasonable, but bottled spring water = extra-pure for special care. It reflects the success of producers in creating nuanced product positions in consumers’ minds (e.g., “natural mineral water” being a step above, in this case). It also highlights that consumers integrate new products into existing routines in a complementary fashion, guided by differentiated meanings (a phenomenon akin to what Rosa et al. (2005) noted about product substitution vs. supplementation in mature categories).

To H3’s core point, we see that producer-induced changes (H2) – such as new quality standards, marketing messages, service offerings – indeed re-shaped consumer conceptual systems. Consumers began to articulate their choices using the language of those new meanings: trust, purity, service, brand reputation, etc., rather than “I boil water because I’m told to.” The data suggest that by the mid-2000s, a large segment of Korean consumers perceived tap water as just one option among many, and often an inferior one. They had internalized a new hierarchy of water quality. This is a profound cognitive shift at the societal level: water, once homogeneous in public consciousness (H2O from the tap), has become diversified, with varying attributes and symbolic values attached to each source.

Interestingly, our interviews also revealed some generational differences consistent with this narrative. Older consumers (who grew up before the 1990s) tended to express more astonishment or initial skepticism about buying water (“It was strange to pay for water, but now we do,” said a 70-year-old). Younger consumers, by contrast, take it as given that water comes in many forms and that paying for safe water is normal. This indicates that the conceptual shift has become culturally embedded over time – younger people were effectively socialized in a post-tap-trust world and thus didn’t need convincing in the same way. Producers no longer need to justify why one would buy water; they only need to explain which water product to buy. That is a testament to how thoroughly consumer mindsets changed in the first decade of the 2000s.

Summarizing H3, the evidence shows that producer-driven market changes led to new consumer knowledge and evaluative criteria. Consumers learned to seek out and value the attributes that producers had built into the product meanings (safety certifications, service reliability, brand integrity, etc.). This coalesced into consumers making more informed, deliberate choices regarding drinking water – reflecting a mature socio-cognitive state of the market. Essentially, by shaping what was on offer and how it was presented, producers shaped what consumers came to want and expect. The socio-cognitive dynamic here is a classic teaching and learning loop: producers “taught” consumers what to care about (through advertising, product design, and even the availability of choices), and consumers “learned” and adjusted their preferences accordingly, which then sets the stage for the next loop of influence (H4).

4.4. Evolved Consumer Perceptions Influence Producer Behavior (H4)

With H3 establishing that consumers acquired new expectations and perceptions, H4 examines how these evolving consumer conceptual systems fed back to alter producers’ behaviors and strategies. Our findings indicate strong support for H4: as consumers became more discerning and their preferences crystallized, producers indeed responded with further adjustments and innovations, essentially fine-tuning the market in line with consumer feedback.

One prominent theme was how consumer demands for convenience and assurance drove producers to expand service and quality initiatives. By the mid-2000s, bottled water companies faced a growing segment of consumers who expressed concerns about the environmental impact of plastic bottles (as noted in interviews and consumer surveys by one industry association). In response, major bottled water producers began adopting lighter-weight bottles, increasing the use of recycled PET, and even running campaigns to encourage bottle recycling. One producer recounted, “We started hearing from customers – via our website and consumer hotline – that they felt guilty about so many bottles. This pushed us to introduce our ‘Eco cap’ and reduce plastic in our bottles by 20% in 2008.” This illustrates H4: consumer values (sustainability concern) influenced concrete producer behavior (innovation in packaging). It also subtly shifted the meaning the producers tried to convey: beyond purity, they wanted to signal eco-friendliness to align with consumer values.

In effect, consumers, having internalized the idea that water should be pure and healthy, extended that to “healthy for the planet too,” and producers responded by integrating that into their offerings. Another bottled water example is the proliferation of sizes and formats – consumer convenience demands led to the introduction of smaller bottles (330ml for portability) and bulk home-delivery boxes. When consumers started buying water in bulk for family use, companies began offering subscription delivery services (some in our data noted around 2010, when they became popular). This service innovation was a direct response to how consumers were integrating bottled water into daily life (no longer just for outings, but as an at-home staple).

In the water purifier market, the feedback loop of H4 is even more evident. As more consumers experienced purifier rental services, they began to expect high standards of customer service and ongoing product improvement. Many consumers, especially those who had used a purifier for several years, emphasized in interviews how crucial the company’s responsiveness was: “If my purifier has an issue, I expect a technician within a day. If not, I might switch providers.” Such expectations pressured companies to improve their service logistics (e.g., increasing the number of service technicians, using ICT for maintenance alerts). One firm’s manager described how competition on service quality ramped up: “Consumers would compare whose service visit was more prompt or who gave a free filter. We had to keep up – we introduced a 24-hour call guarantee and started training our service staff to be more professional and friendly because that became a selling point.” This shift – focusing on the service experience – was not originally central to producers’ minds, but became so because consumers made it part of their decision calculus. As a result, by the late 2010s, marketing for purifiers often highlighted service awards or customer satisfaction rankings, indicating producers pivoting to meet the consumer’s conceptual emphasis on service reliability.

Consumers also influenced product development. For example, several purifier users expressed a desire for more compact or aesthetically pleasing designs, as the bulky early models took up counter space and looked industrial. Producers took note: one interviewee from a design team said, “We got feedback, especially from younger households, that the purifier should look nice in the kitchen. This led us to collaborate with designers for sleek styles and colors.” Indeed, by the mid-2010s, slim and chic purifier models entered the market, a departure from the utilitarian white boxes of old. Similarly, consumer feedback led to multi-function purifiers (the ability to get cold, hot, or even sparkling water from one machine) because consumers voiced interest in convenience and avoiding multiple appliances. As a concrete example, Company C launched a hot/cold purifier after surveys showed that many purifier owners still boiled water or cooled it for specific uses – the company realized consumers wanted temperature options on demand. This reflects how consumer “wants” (convenience, multifunctionality) guided producers in reimagining the product’s features, thereby expanding its meaning to “all-in-one water solution.”

Another area of consumer influence was pricing and contract terms. Initially, purifier rentals were somewhat rigid (e.g., 3-year contracts). Consumers, gaining more options as multiple firms offered rentals, began to demand flexibility – some didn’t like long lock-in periods or wanted the option to upgrade. Sensing this, newer companies offered shorter contracts or upgrade programs, forcing incumbents to match. One industry expert noted, “Consumers became savvy; they would switch providers if terms were better. This pushed the whole industry to be more customer-friendly in policies.” Consequently, producers’ business models shifted to be more agile, with month-to-month plans, trial periods, and loyalty benefits introduced. This again is producers changing behavior (business model innovation) in response to how consumers’ conceptualization of a good deal or a trustworthy provider evolved (initially, consumers might have accepted any terms to get clean water, but later they conceptualized the service as a competitive market where they hold power).

It’s noteworthy that consumer voice – via both direct feedback channels and market behavior – became an increasingly important driver as the markets matured. Early on, producers were guessing consumer needs; later, consumers were explicitly telling producers what they wanted. This dynamic is captured well by one producer’s remark: “By 2010, we basically co-created new products with our customers. We’d either pilot a new filter feature to gauge customer reaction or crowdsource ideas for the next model. They’d tell us if we hit the mark or not.” Such co-creation is an advanced form of H4, where the consumer’s conceptual input is actively solicited to shape product design.

How often did stakeholders reference key concepts, shedding light on this interactive influence? Consumers, for instance, referenced “trust” and “safety” very frequently (15 and 10 mentions, respectively, in our coded segments for consumers), and producers likewise often referenced those concepts (8 and 12 mentions, respectively), indicating a mutual focus. “Service”, however, was discussed asymmetrically: consumers mentioned it moderately (5 mentions), whereas purifier producers mentioned it very often (about 10 mentions), suggesting that producers emphasized it to meet consumer expectations (and possibly to increase the salience of service in consumers’ minds). “Environmental impact” was raised more by producers (especially bottled water producers, with 5 mentions) than by consumers (perhaps four mentions), suggesting that producers were responding to a nascent consumer concern and maybe even trying to lead consumers to care more about it. This interplay of mentions underscores that producers and consumers were in a dialogue of sorts, each influencing what the other discussed and valued.

Overall, H4 is validated by the adaptive moves producers made in response to the more sophisticated and assertive consumer base that emerged. The relationship became less one-sided: whereas initially producers led the way (by telling consumers why they need these products), in later stages consumers led by saying, “this is how we want those products to be.” The socio-cognitive dynamic matured into a kind of equilibrium-seeking behavior – the market participants negotiating an optimal state that satisfies consumer desires and producer capacities.

This iterative feedback ultimately set the stage for H5, as the producers’ and consumers’ conceptual systems moved closer together, integrating each other’s influence. By continually responding to consumer input, producers effectively aligned the product’s meaning with consumer values. The following section (H5) will discuss the outcome of this convergence: the new shared understanding of bottled water and water purifiers that became established in Korea, and how that shared meaning reflects both parties’ contributions.

4.5. Convergence into New Shared Meanings (H5)

H5 posited that the result of the iterative producer–consumer interactions would be a new, stable shared meaning of the product from both perspectives. The evidence supports this: by the mid-to-late 2010s, both producers and consumers in Korea appeared to have reached a consensus on what bottled water and water purifiers represent and their role in daily life. This new consensus meaning was markedly different from the initial state decades ago.

For bottled water, the shared meaning that emerged can be summarized as:

“a convenient, healthy, and trustworthy source of drinking water, albeit with environmental considerations.” Producers and consumers both talk about bottled water in these terms now. In interviews, when asked why people drink bottled water, producers and consumers alike cited safety and health first, followed by taste and convenience. Notably, no one in our recent interviews (either side) framed bottled water as a luxury or frivolity – a stark change from early days when even policymakers dismissed it as unnecessary since Korea had treated tap water.

An expert interviewee observed, “Bottled water has become normal – it’s considered a basic grocery item.” This normalization is a sign of shared understanding. Rosa et al. (1999) described how a product market stabilizes around a prototype or normative understanding [

1]; in Korea, the prototype for bottled water became something like a 2-liter bottle for home use or a 500ml bottle for on-the-go convenience. The acceptability of that practice is now generally unquestioned, except for environmental critiques that producers acknowledge and incorporate (e.g., through CSR campaigns for recycling).

Interestingly, producers and consumers also converged on an understanding of tap water’s role relative to bottled water. Whereas initially there was debate (is bottled water truly needed?), by 2020 the dominant narrative – reflected in the media and interviews – is that tap water is fine for cleaning or, maybe, boiling. Still, for drinking, many prefer bottled or purified water. This view is now widespread enough that even Seoul metropolitan government campaigns to promote tap water (like “Arisu Love” in Seoul) face uphill battles.

One regulator admitted, “It’s hard to change minds now; bottled water is seen as safer by default.” That statement indicates how entrenched the new meaning is: safety as an inherent quality of bottled water in the social mind [

8]. Producers, for their part, see their mission as continuing to uphold that safety and improve sustainability, rather than convincing people to drink bottled water in the first place – demand is assumed.

So the discourse shifted from “why drink bottled water” to “how to drink bottled water responsibly.”

For water purifiers, the shared meaning coalesced around the idea of “an essential home appliance/service for ensuring safe and convenient water.” Both consumers and producers commonly refer to purifiers as almost a necessity in modern homes (especially in urban Korea). One consumer said, “A purifier is as common as a refrigerator now. You move into a new apartment, you usually get one.” A producer echoed that sentiment: “In new housing ads, they often show a built-in water purifier; it’s become part of expected amenities.” This alignment shows that the concept of a purifier has shifted from exotic to mundane – a classic sign of convergence in meaning (the product is fully institutionalized). The “service” aspect is also part of the shared meaning: people understand that owning a purifier means a subscription with regular maintenance. Far from being seen as odd, this is considered wise; for example, consumers brag about how responsive their purifier service is, much like they would about an internet provider or a car service center. So, producers and consumers together evolved the purifier category into a service-centric utility concept.

Crucially, this final meaning incorporated elements that were absent at the start but introduced through the socio-cognitive process. For instance, the idea that drinking water should contain natural minerals (rather than be just pure H₂O) became part of the bottled water narrative due to producers’ emphasis – and now consumers believe mineral content is beneficial [

8].

On purifiers, the notion that regular professional maintenance is required for truly safe water was hammered by producers (often to differentiate from DIY filter pitchers), and consumers have come to agree – many mentioned they “don’t trust those simple filters, you need the company to handle it.” Thus, the final shared meanings are richer and more complex than the initial ones (which were: tap water vs. not tap water). They embed the lessons learned over the market’s evolution: trust needs to be maintained (so certificates, maintenance, seals of quality are valued), water can have enhanced value (minerals, temperature, carbonation), and consumption has broader implications (like environmental footprint, which is why consumers appreciate if a purifier reduces bottle usage, or if bottled water companies engage in recycling programs). Indeed, one could argue that the shared meaning for each product now includes a sustainability dimension. Consumers often see purifiers as the environmentally friendly choice (no plastic bottles), a point that purifier producers naturally highlight. Conversely, bottled water’s environmental impact has a slight negative tint, which producers are trying to counterbalance with green initiatives. Both sides acknowledge this aspect: e.g., consumers said they feel “a bit bad using so many bottles,” and producers said “we know we have to address the plastic issue to keep customers feeling good about using our water.” Although not perfectly resolved, the fact that both are cognizant of it and are discussing it shows that it is part of the mutual understanding of what the product category entails in today’s world.

To illustrate how far the convergence has come, consider the language used by both stakeholders. In interviews, when describing bottled water, consumers and producers alike used terms like “clean,” “healthy,” “portable,” and even “tastes good” – essentially, consumers had adopted the marketing vocabulary, and genuine consumer concerns (taste, health) were reflected in marketing, indistinguishably. For purifiers, terms like “convenient,” “always available,” and “peace of mind” appear on both sides. An expert noted that the discourse about water in Korea changed fundamentally: “We used to talk about foreign matter in tap water; now people talk about maintenance and service for water – that shows how the conversation shifted to maintenance of purity rather than assumption of impurity.” In other words, rather than fearing unseen contaminants (which was the early 90s focus), the shared focus now is on actively keeping water clean through proper management (via either trusted brands or devices). This indicates a mature collective understanding that water safety is an ongoing process, which is why these products exist. It’s a more nuanced, perhaps more empowered stance compared to initial fear and knee-jerk avoidance.

The fulfillment of H5 also implies that the market reached a relatively stable state. Indeed, by the late 2010s, growth rates of both markets stabilized, and dramatic changes became less frequent. Bottled water was a stable, regulated industry with a few dominant brands; water purifiers were ubiquitous with a few major service providers. The co-evolved meanings likely contributed to this stability. Everyone knew what to expect and what was expected of them (consumers expect safe water and service, producers know how to deliver that consistently). This doesn’t mean there’s no innovation (e.g., IoT-connected purifiers are an emerging trend, and bottled water brands experiment with biodegradable bottles). Still, these are incremental improvements consistent with the shared narrative rather than radical shifts.

One could reflect on whether these shared meanings align with sustainability goals. Arguably, the new meanings have pros and cons for sustainability. On one hand, a society reliant on bottled water can be seen as unsustainable (plastic waste, energy for bottling and transport). On the other hand, the focus on safety and health might drive investments in overall water quality improvements (indeed, the government didn’t sit idle; it significantly improved tap water standards in response to competition, as one expert pointed out). For purifiers, the appliance approach has its own environmental costs (manufacturing, electricity, filter waste). Still, it eliminates single-use plastic, so in Korea it’s often touted as the long-term eco-friendly choice. The shared meaning of purifiers as essential might reduce public support for municipal investments (if everyone handles it privately), which is a double-edged sword from a sustainability perspective. These broader implications are discussed in the next section. What’s clear from H5 is that the socio-cognitive process we traced did result in a relatively unified producer-consumer outlook on these products – a testament to how mutual adaptation and continuous feedback can lead to market stabilization in terms of meaning and practices [

1,

2,

7,

9].

In closing this Results section, our analysis across H1–H5 paints a comprehensive picture of how Korea’s bottled water and water purifier markets evolved through social cognition. We saw initial external triggers (H1) altering producer mindsets, leading to strategic innovations (H2), which reframed consumer perceptions (H3), prompting further producer responses (H4), and culminating in a new equilibrium of understanding (H5). Throughout, the interplay of media, regulation, and market actors was critical – indeed, our findings resonate strongly with Rosa et al. (1999)’s notion that markets develop through stories and feedback rather than by any one actor’s design [

1]. In the next section, we discuss these findings in light of theoretical contributions and practical implications, particularly focusing on sustainability aspects and what this case teaches about guiding socio-cognitive change towards positive environmental outcomes.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications: Social Cognition in Market Evolution

Our study contributes to a deeper theoretical understanding of how socio-cognitive processes drive market evolution, complementing and extending prior work in marketing and organization studies. We provide an empirical illustration of Bandura’s social cognitive theory in an applied marketplace context, showing how reciprocal determinism plays out between firms and consumers [

1,

2,

3,

4,

7]. The Korean water markets highlight that neither consumers nor producers alone dictated outcomes; rather, their continuous interaction – mediated by environmental signals – shaped the trajectory. This aligns with the findings of Rosa et al. (1999) that product markets are co-constructed through feedback loops [

1,

2,

7]. However, our work adds nuance by explicitly incorporating institutional actors (regulators) and cultural factors (risk perception, sustainability ethos) into the socio-cognitive model. In doing so, we echo and build on Wood & Bandura (1989), who argued that organizational practices (here, industry behavior) are influenced by cognitive and environmental factors in tandem [

3]. In our case, regulatory changes served as external stimuli that altered cognitive frames (e.g., legalization in 1995 suddenly made “water as product” cognitively legitimate for businesses and consumers). This suggests a refinement to socio-cognitive market theory: institutional triggers can accelerate the sensemaking process by providing explicit permission or urgency for market actors to reconceive roles.

Our findings also bridge to consumer culture theory via McCracken’s meaning transfer model [

5]. We witnessed the cultural construction of product meaning in real time: initially, safety meaning moved from the culturally constituted world (a society increasingly valuing health and purity) into the products (bottled water marketed as pure, purifiers as guaranteeing safety), and then that meaning was experienced and reinforced by consumers in rituals (daily drinking). We found evidence of the two-stage flow McCracken described: media and advertising transmitted meaning to the product, and consumers’ use and word of mouth spread it into their personal lives.

For instance, the idea of “bottled spring water from Jeju = wellness” started as a marketing story but became a personal belief for many consumers. Over time, as predicted by McCracken, the product’s meaning stabilized in the culture, such that even without advertising, people attribute certain meanings to it (e.g., pouring guests bottled water is seen as considerate, indicating how social norms around the product have taken hold). By applying McCracken’s framework, we underscore that product meaning co-evolution is at once a cognitive and cultural phenomenon – cognitive in how individuals process and react (as our grounded theory approach captured) and cultural in how these meanings become shared and taken-for-granted.

Another theoretical contribution lies in demonstrating grounded theory’s value for research on sustainability and market dynamics. Our use of grounded theory allowed us to uncover emergent themes like trust, risk, and service, which might not be fully accounted for in existing models of sustainable consumption. Grounded theory scholars like Charmaz (2014) emphasize constructing theory from lived experiences [

16]; we did so and found, for example, that “trust in infrastructure” is a pivotal construct that mediates whether a population will accept public resources or shift to private market solutions. This has echoes in broader contexts (e.g., trust in public food safety vs. organic market growth). Thus, one implication is that socio-cognitive dynamics can serve as a lens for examining other sustainable product domains – such as renewable energy adoption, where trust in the grid vs. home systems might play a similar role. Our iterative, data-driven approach can be a template for researching those domains, ensuring that theory captures the voices and conceptual frames of all stakeholders, not just top-down assumptions.

Furthermore, our results enrich social cognitive theory by highlighting the role of collective efficacy and collective meaning-making. Bandura’s work often focuses on

individual efficacy beliefs [

3,

4], but in our case we see a kind of

collective efficacy: consumers banded together (through discourse and demand) to push companies to provide better solutions, and producers collectively improved offerings that gave consumers greater control over water quality. This back-and-forth enhanced the overall collective confidence that clean water can be ensured – albeit by new means. Wood and Bandura (1989) talked about how modeling and mastery experiences in organizations shape behavior [

3,

4]; analogously, Korean society underwent

a collective learning (through media “modeling” crises and then seeing successful private solutions), which in turn shaped normative behaviors (it became normative to boil water or get a purifier after seeing others do so). Our study thus underscores that collective learning processes are crucial in sustainability transitions –

a community learns by observing outcomes (good or bad) and adjusting practices accordingly.

5.2. Sustainability and Socio-Cognitive Dynamics

From a sustainability standpoint, our findings carry both cautionary and hopeful notes. On the one hand, the socio-cognitive trajectory we documented led to the widespread adoption of bottled water and purifiers – solutions that have their own environmental footprints. The perception of tap water’s unsustainability (due to health risk) drove consumers to alternatives that, in aggregate, may be less sustainable (plastic waste, higher energy use). This suggests a paradox: improving perceived sustainability (personal health safety) can sometimes conflict with broader environmental sustainability. Policymakers should be mindful that purely emphasizing individual risk can spark market shifts that create other environmental burdens. In Korea’s case, one might argue that a more sustainable approach would have been to invest even more heavily in rebuilding trust in the public water system (thus avoiding the need for so much bottled water). However, such trust-building is easier said than done – as our study shows, once broken, trust is hard to fully restore, and socio-cognitive momentum tends to maintain new patterns.

On the other hand, there are positive sustainability implications. The water purifier market, while propelled by trust deficits, actually offers an example of a sustainable product-service system: rather than millions of plastic bottles, many consumers get water through a durable appliance and a service loop, which is arguably a more resource-efficient model. This reflects how socio-cognitive dynamics can unexpectedly align with sustainability: the concept of rental and maintenance arose to ensure quality, but it also fits the circular economy ideal (maintenance extending product life, centralized filter recycling, etc.). This could be seen as a form of “sustainable innovation” emerging from market dialogue, not originally intended to be eco-friendly, but that now serves that role. For instance, experts noted that PET bottle waste in Seoul saw some reduction as purifier adoption grew, a collateral environmental benefit.

Our results also illustrate the importance of media and communication in steering sustainable behavior. The media essentially “programmed” consumer fears in the early 90s (

Table 1), leading to a run on bottled water. But later, media and civil society also raised environmental concerns (reports on plastic pollution, etc.), which started influencing consumers (albeit to a lesser degree than health concerns). This indicates that sustainability narratives can be injected into the socio-cognitive cycle. If, for example, media and producers emphasize the sustainability advantages of purifiers (no plastic, local filtering) more, that could further tilt consumers toward that option over bottled water. We saw some producers doing this (one purifier firm’s marketing explicitly targeted bottled water users, highlighting waste reduction).

Thus, one actionable insight is that shaping the narrative is key to steering markets toward sustainable ends.

Stakeholders who want to promote sustainability (including regulators and NGOs) should engage in the meaning-making process – effectively competing in the cognitive marketplace of ideas. In Korea’s case, NGOs eventually campaigned for tap water as the most eco-friendly option (with mixed success). The lesson is, sustainability must be woven into the product’s meaning in consumers’ and producers’ minds to gain traction. Experts (including NGO voices) discussed sustainability far more than consumers did. Bridging that gap by integrating environmental values into mainstream consumer discourse remains a continuing challenge.

5.3. Managerial Implications for Industry and Policy

For industry practitioners, especially those in sectors related to health, safety, and sustainability, our study underscores the value of staying attuned to socio-cognitive shifts. Companies should monitor not just consumer behavior but also the rationales and narratives consumers use, as these often foreshadow market changes. In our case, firms that recognized early the trust issue (and, say, had their bottled water certified by authorities or advertised stringent testing) gained a competitive edge by aligning with consumer anxieties. Similarly, purifier companies that realized they were selling “peace of mind” as much as devices moved ahead of those clinging to a pure sales model. The implication is that firms should deliberately define their product’s meaning and be willing to pivot it as the shared understanding evolves. This might involve rebranding or business model innovation. For instance, a bottled water company today might rebrand itself not just on purity but also on sustainability commitments, to resonate with a slowly greening consumer mindset. If we consider Bandura’s notion of modeling, companies can model desired behaviors for consumers (e.g., a campaign showing a family refilling a reusable bottle from a purifier, thereby modeling sustainable practices). By doing so, companies don’t just respond to meaning – they help shape it. Our findings show producers did shape meaning (inadvertently or purposefully); going forward, they might do so with explicit sustainability goals in mind.

For policymakers and regulators, our study provides evidence that interventions in market dynamics need to consider the socio-cognitive element. Regulations like Korea’s Drinking Water Management Act of 1994 had a profound cognitive effect – it signaled to society that bottled water was a legitimate and perhaps necessary category. Regulators thus hold power not only to control market externalities but also to validate or invalidate product categories. If a government is concerned about plastic waste, for example, simply taxing bottled water (an external incentive) might not suffice; they may also need to run campaigns to alter the perception of bottled water’s necessity. Conversely, they could bolster the image of tap water through transparency and publicized quality improvements to reclaim consumer trust (essentially trying to reverse some of the socio-cognitive trajectory we observed). Our findings caution that once the genie is out of the bottle (pun intended) in terms of public perception, it’s tough to reverse. Proactive risk communication and rapid response to environmental issues are crucial to prevent trust crises. Korea’s experience suggests that if public trust in sustainability-critical infrastructure falters, the market may route around it, creating new challenges. Therefore, ensuring robust public trust (through data sharing, third-party monitoring, and swift crisis management) is not just a public relations issue but integral to the sustainable management of resources.

In a broader sense, our research speaks to the management of organizational knowledge and stakeholder engagement. The co-creation of meaning between companies and consumers, as seen here, is akin to stakeholder co-innovation. Firms in other sectors (e.g., renewable energy tech, organic foods) could benefit from involving lead users and consumer communities in dialogue to shape product development – as happened naturally with H4's water purifiers, but could be formalized. It reduces uncertainty if a company understands the evolving narrative among its customer base.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

While our study provides comprehensive insights, it also highlights limitations that open avenues for further research. First, our analysis is context-specific to South Korea, a country with high media connectivity, rapid economic development, and particular cultural attitudes towards health and technology. Cross-cultural studies could examine whether similar socio-cognitive dynamics occur elsewhere and, if so, how they differ. For example, in countries where public trust in infrastructure remains high, do bottled water markets fail to take off (e.g., in some European countries)? Or in places with different cultural beliefs about water (spiritual or traditional values), how do those mediate the meaning-making? Comparative research can enrich the theoretical framework by adding cultural and institutional variables.

Second, our method was qualitative and, to a degree, retrospective. Longitudinal quantitative studies could complement this by measuring changes in consumer attitudes over time alongside media sentiment analysis to more precisely gauge causality and magnitude. For instance, sentiment analysis of news and social media could quantify the “trust sentiment” and correlate it with sales of water purifiers or bottled water. This would build on our work by adding predictive power and external validity.

Third, an area for future work is examining the post-convergence phase: now that shared meanings are established, what causes further change? Are they stable indefinitely, or could a new disruption (say, a major environmental campaign or a new technology like home water testing IoT devices) upset the equilibrium? Rosa et al. (2005) discuss how even mature markets can experience “trigger events” that prompt new socio-cognitive cycles [

7]. In our context, potential triggers could include

climate change impacts on water supply or a significant innovation in public water treatment aimed at winning back consumers. Studying such developments would test the resilience of the socio-cognitive equilibrium we identified.

Finally, our research has primarily focused on the positive or adaptive side of these dynamics (the market providing solutions people wanted). However, there is a critical perspective: what about those left behind? Bottled water and purifiers cost money; lower-income households might not be able to afford them and thus still rely on tap water. If most of society moves on to private solutions, there’s a risk of institutional neglect of public water systems, which can increase inequality. Investigating the socio-cognitive dynamics with an equity lens – who participates in meaning-making and who has voice – would be a valuable extension. In our interviews, most consumers were typical middle-class; future work should include marginalized voices to see whether their meanings differ (e.g., perhaps some trust tap water because they must, or use alternative methods like rainwater). This could inform policy on ensuring sustainable solutions are inclusive.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study examined how product meanings and stakeholder behaviors co-evolved in Korea’s bottled water and water purifier markets, under the influence of media, regulation, and market dynamics. Through a grounded theory analysis of rich qualitative data, we traced a socio-cognitive journey spanning initial distrust in public systems, entrepreneurial innovation, consumer adaptation, and eventual market stabilization with new shared understandings of what “drinking water” entails. Our findings confirm that socio-cognitive factors—perceptions of risk, narratives of trust, and cultural values of health and convenience—are not just background variables but central drivers of market trajectories.

For researchers, our work underscores the value of integrating perspectives from social cognitive theory, consumer culture theory, and grounded, context-specific analysis to unravel complex sustainability transitions. Markets for essential resources like water are not purely shaped by objective utility or price, but by how people think and feel about those resources. In Korea, a shift in collective mindset regarding water quality catalyzed the emergence of two substantial industries. Understanding such phenomena can help design interventions for other sustainability challenges—whether energy, food, or waste management—where public perception and trust are critical.

For practitioners and policy-makers, a key takeaway is the importance of maintaining public trust and proactively managing the narrative around essential services. Once trust in tap water was compromised, consumers exercised agency by seeking alternatives; the genie of doubt could not be fully put back in the bottle, despite improvements. Thus, ensuring transparency, responsiveness, and public engagement is vital to the governance of common resources. At the same time, the innovations that emerged (especially service-based approaches) show that the private sector can complement public efforts when well aligned. A collaborative approach where governments set high standards and encourage innovation, and companies compete to meet those standards while educating consumers, could yield the best outcomes for sustainability. For instance, public policy could incentivize water purifier firms to develop low-energy, recyclable-filter technologies, marrying the trust solution with environmental stewardship.

In conclusion, the Korean case of drinking water markets illustrates a broader principle: sustainable consumption is as much a social and cognitive journey as it is a technological or economic one. By paying attention to how meanings form and change, and by involving stakeholders in shaping those meanings towards the collective good, we can better navigate the path to sustainability. The co-evolution of product meaning and behavior in these markets not only resolved an immediate public health concern but also set the stage for ongoing improvements and conversations about water security, illustrating the dynamic interplay between society, technology, and the environment. Future policies and business strategies in sustainability domains would do well to heed the lesson that winning hearts and minds is half the battle in winning sustainability.