1. Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention1, in 2021, roughly 8.9% of the U.S. population–or about 29.7 million people–had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. Of the U.S. adults who have been diagnosed with diabetes, about 91.2% have type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM)2. In T2DM, the body may produce insulin, but the tissues are insulin resistant, meaning that they cannot respond to that insulin. If untreated, T2DM can lead to a variety of health complications including cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, peripheral neuropathy, and sleep disordered breathing (SDB).

Of these complications, SDB has a particularly interesting interplay with T2DM. SDB describes a spectrum of conditions which cause abnormal breathing during sleep, typically by affecting the upper airway 3. One type of SDB called obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a disorder where the upper airway partially or completely collapses during sleep, which can lead to apneas (transient pauses in breathing), hypoxemia, and decreased quality and duration of sleep. Patients with OSA often present with snoring, daytime sleepiness, and fatigue4.

In addition to having similar risk factors–including increased age, smoking, alcoholism, and increased BMI5, OSA and T2DM may exacerbate each other3,6,7,8. For instance, decreased sleep quality, such as frequent waking, has been associated with decreased insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance 7,9.10. Furthermore, T2DM may affect control of breathing and pharyngeal muscles, which can worsen OSA6Notably, OSA is more common among people with T2DM than among the general population. The overall prevalence of OSA diagnosed by PSG among people with T2DM ranges from 58-86% 11. However, there is some uncertainty about the true prevalence of OSA in diabetic patients. Heffner et al.12 found that only 18% of patients with T2DM were officially diagnosed with OSA by their primary care physician, although the investigators attributed this number to underdiagnosis.

It is likely that many of these patients with T2DM have been prescribed the oral medication Metformin. According to the American Diabetes Association1 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, Metformin is the first line drug for treating T2DM in patients over the age of 10 years old. Metformin can be used as a monotherapy or in combination with other antidiabetic drugs, depending on the severity of the diabetes. It works by improving insulin sensitivity, decreasing glucose production in the liver, and decreasing glucose absorption by the intestines14. Over the years, Metformin prescribing has increased. In 2000, FDA-approved prescriptions of Metformin numbered 2.27 per 1000 people in the U.S., but by 2015, this number had increased to 235 per 1000 people 15. As of 2023, Metformin was being taken by over 200 million people worldwide16.

Some of the rarer side effects of Metformin include insomnia and nightmares17,18. Although there is limited research on the mechanism behind this effect of Metformin, it has been well documented that diabetes and differential glycemic control affect sleep architecture–the organization and stages of sleep. A higher Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) has been associated with decreased REM sleep latency (the time between falling asleep and the first REM cycle)19, and decreased sleep efficiency (percent of time in bed that is spent asleep) 20. However, there is conflicting data on the relationship between T2DM and sleep stage duration. While Pallayova et al.21 found that people with T2DM experience decreased slow-wave (N3) sleep and increased REM sleep, a more recent study by Chen et al.22 suggested the opposite, that T2DM leads to increased slow-wave and decreased REM sleep. Additionally, our previous work investigating the effect of insulin on sleep architecture showed that insulin therapy was associated with reduced REM and N3 sleep, without differences between genders in patients with high BMI23, 24. It is important to note such changes to sleep architecture because healthy sleep architecture accounts for the various benefits of sleep. For example, the deep stages of non-REM sleep aid in tissue repair 25, and REM sleep is important for memory consolidation and learning26.

Given the rise in Metformin prescriptions and the data indicating that both diabetes and Metformin affect sleep, the purpose of this study is to determine whether Metformin is associated with changes to sleep architecture in patients presenting with T2DM and OSA. Specifically, we aim to study the relationship between different phases of sleep and total time in sleep in these patients.

2. Hypothesis

We hypothesize that Metformin affects sleep and influences sleep architecture. Thus, we sought to determine sleep architecture in T2DM patients taking Metformin for metabolic control who showed sleep-disturbance side effects of excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, and fatigue.

3. Methods

We conducted a retrospective community-based cohort study that was approved by California University of Science and Medicine IRB-HS-2020-11. Study participants included a diverse patient population in an underserved area in Southern California. PSG was medically indicated in these patients because of suspected sleep disorders, and patients were referred to the Sleep Clinic for evaluation and treatment by their primary care physicians27.

Inclusion criteria included: (1) Adult patients 18 years of age or older, (2) Patients with T2DM and currently receiving treatment, (3) Diabetic patients undergoing overnight PSG only (without CPAP treatment) under technician observation in a sleep laboratory.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) Non-Diabetic patients, (2) Diabetic patients not taking conventional medication of Metformin or Insulin, (3) Under 18 years of age, (4) Patients undergoing split night study or CPAP treatment, (5) Sleep study that was less than 6 hours long, (6) Patient who consumed oxybate (Xyrem) on the night of study, as oxybates increase slow wave sleep28.

Patients underwent six channels: EEG, EOG, EMG, EKG, and pulse oximetry. Thoracic and abdominal respiratory effort was measured through respiratory inductance plethysmography (RIP) belts, body position, and air flow monitoring was done through thermistor and body position sensors. Sleep staging was done by an experienced sleep technician using American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines29 and verified by a physician, both of whom were blind to the study. Data on age, gender, BMI, and medications were collected. N1, N2, N3 and REM sleep stage data were analyzed. Each sleep stage was analyzed in relation to total sleep time. Data analysis included the mean + standard deviation and t-test with statistical significance determined by p-value<0.05.

4. Results

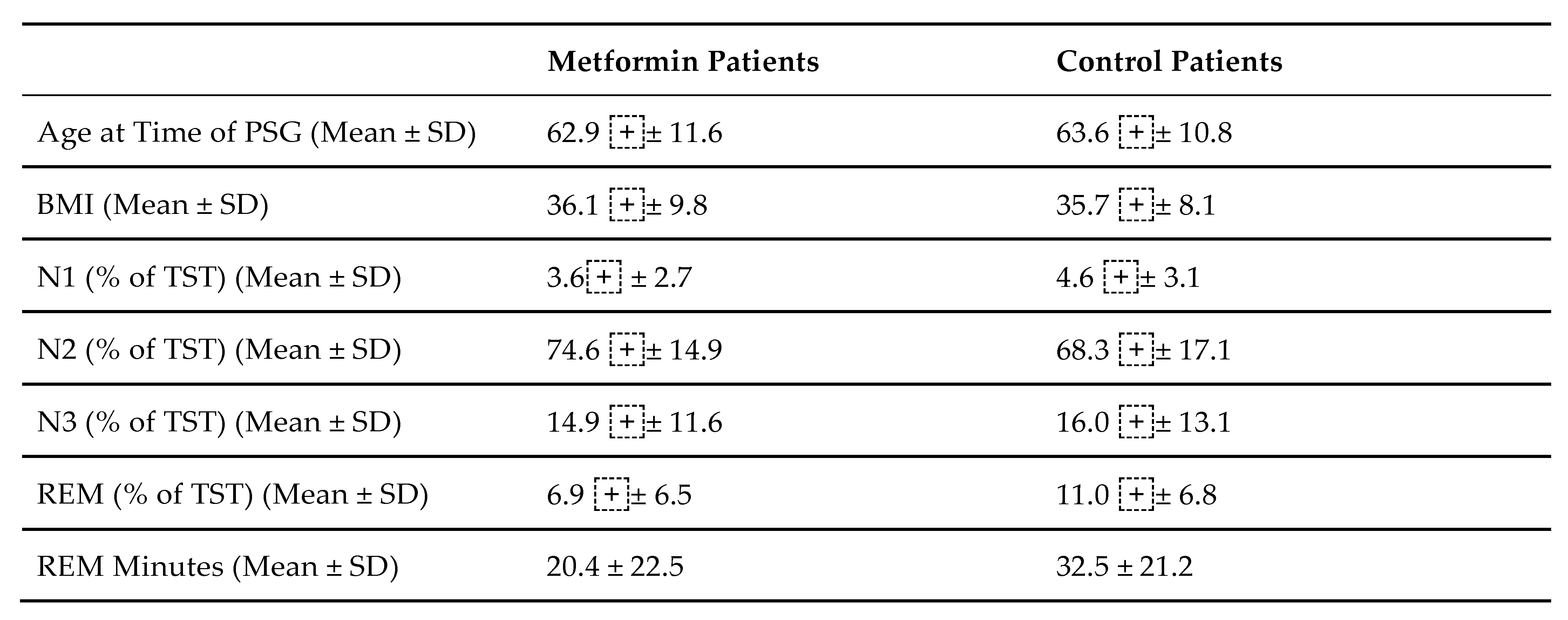

In 29 patients taking Metformin, there was a significant REM sleep decrease compared to 22 control patients who did not take Metformin, but rather some other form of diabetes therapy, such as Lantus or Novolog (p = 0.03,

Table 1, Fig 1). There was no significant change in N3 sleep between patients taking Metformin and non-Metformin patients taking an alternative therapy (p = 0.75,

Table 1).

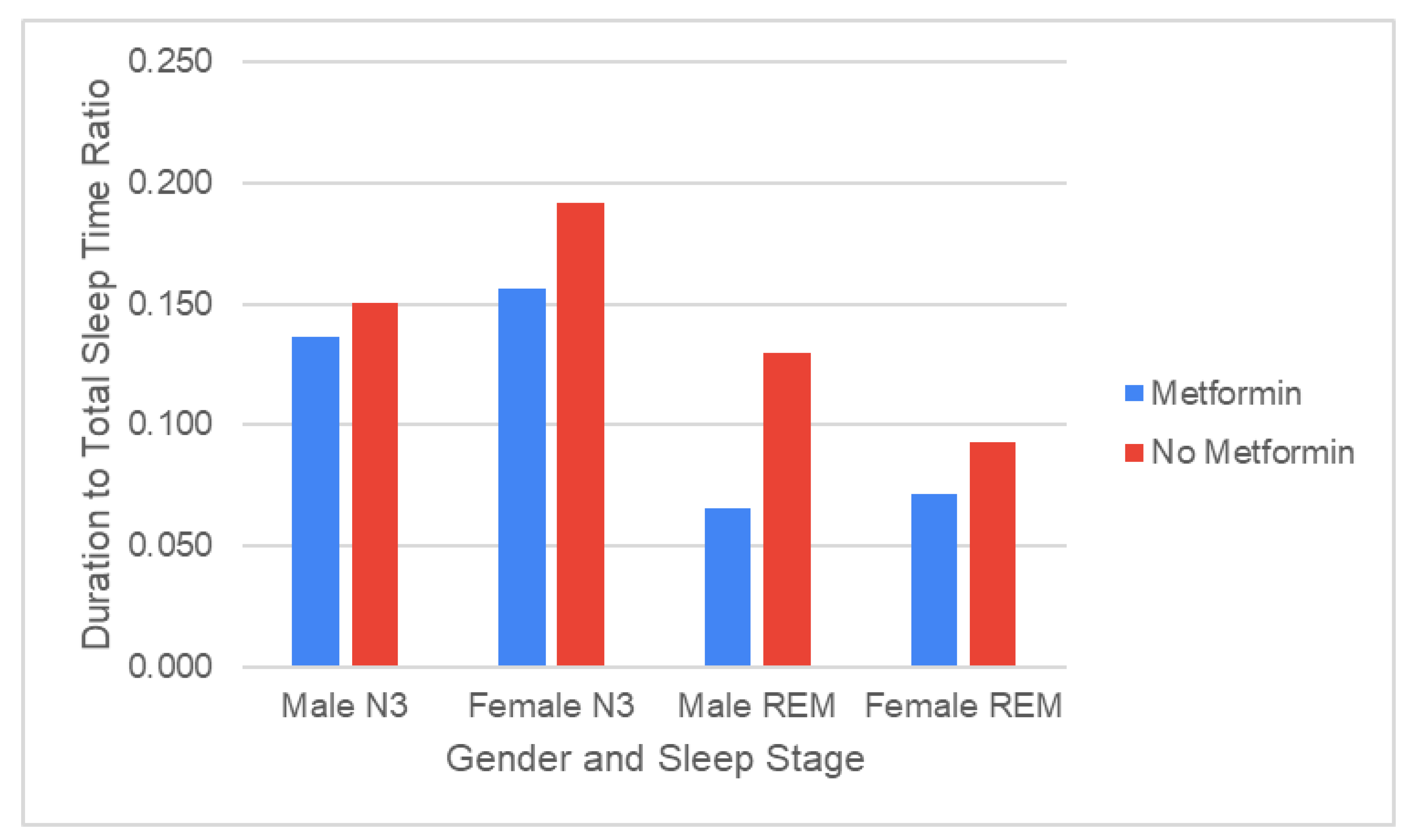

Of the 29 patients prescribed Metformin, 20 patients were women and 9 patients were men. There was no significant difference in both REM sleep time and N3 sleep time between sexes (

Figure 1). Moreover, of the patients on Metformin, 13 patients had a prior smoking history or were active smokers, 14 had never smoked tobacco, and 2 had an unknown smoking history. There was no significant difference in either REM sleep duration or N3 sleep duration between smokers and non-smokers.

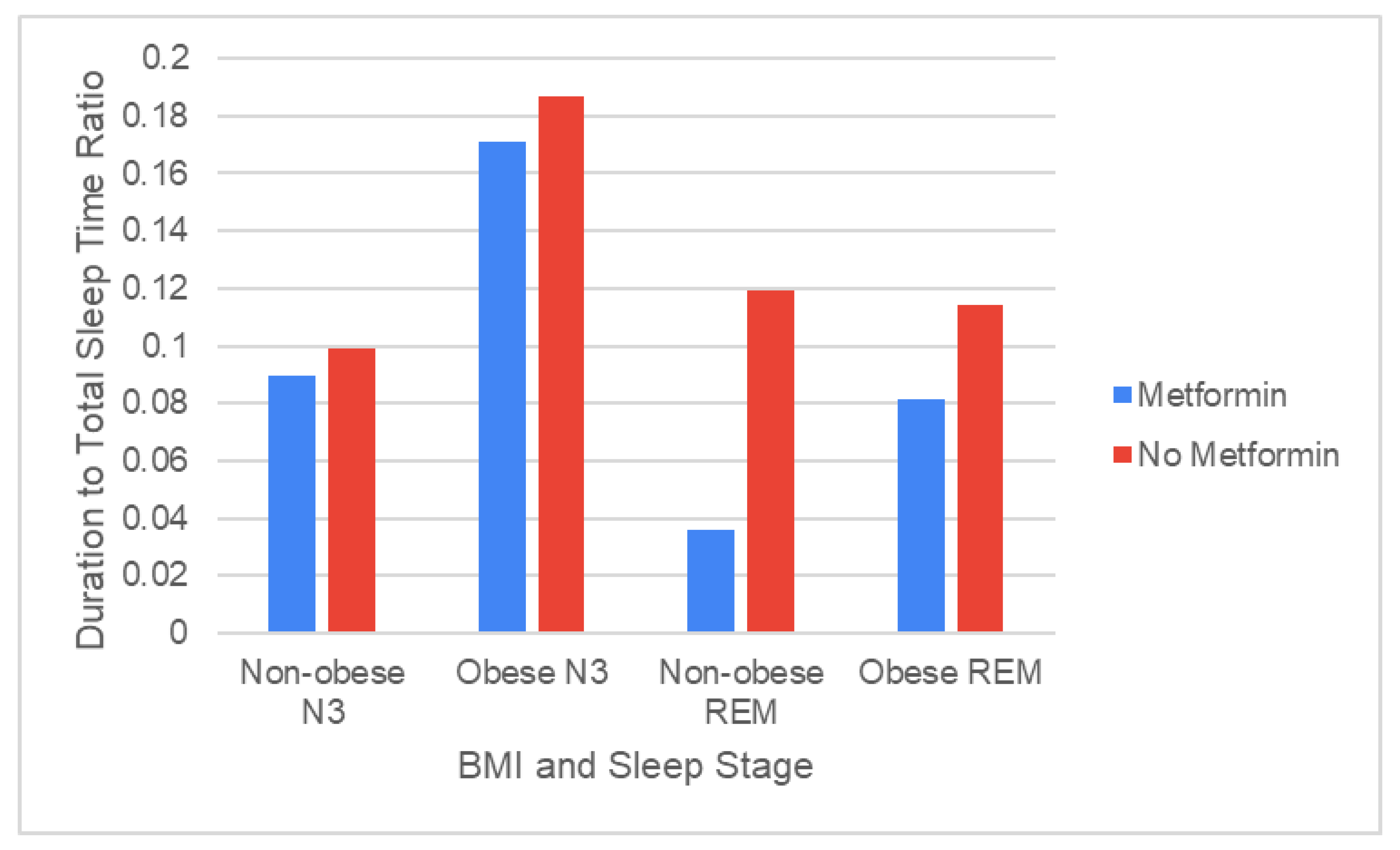

Using data from 12 non-obese patients, of whom 7 patients were prescribed Metformin and 5 patients were not, we found that patients taking Metformin experienced significantly shorter durations of REM sleep than patients on alternative therapy (p = 0.036,

Figure 2).

Using data from 36 obese patients, of whom 20 patients were prescribed Metformin and 16 patients were not, we found no significant difference between the duration of REM sleep between Metformin patients and non-Metformin patients, although Metformin patients on average had a lower duration of REM sleep (

Figure 2). In both non-obese patients and obese patients, no significant difference in N3 sleep duration was observed between patients taking Metformin and those taking alternative therapies.

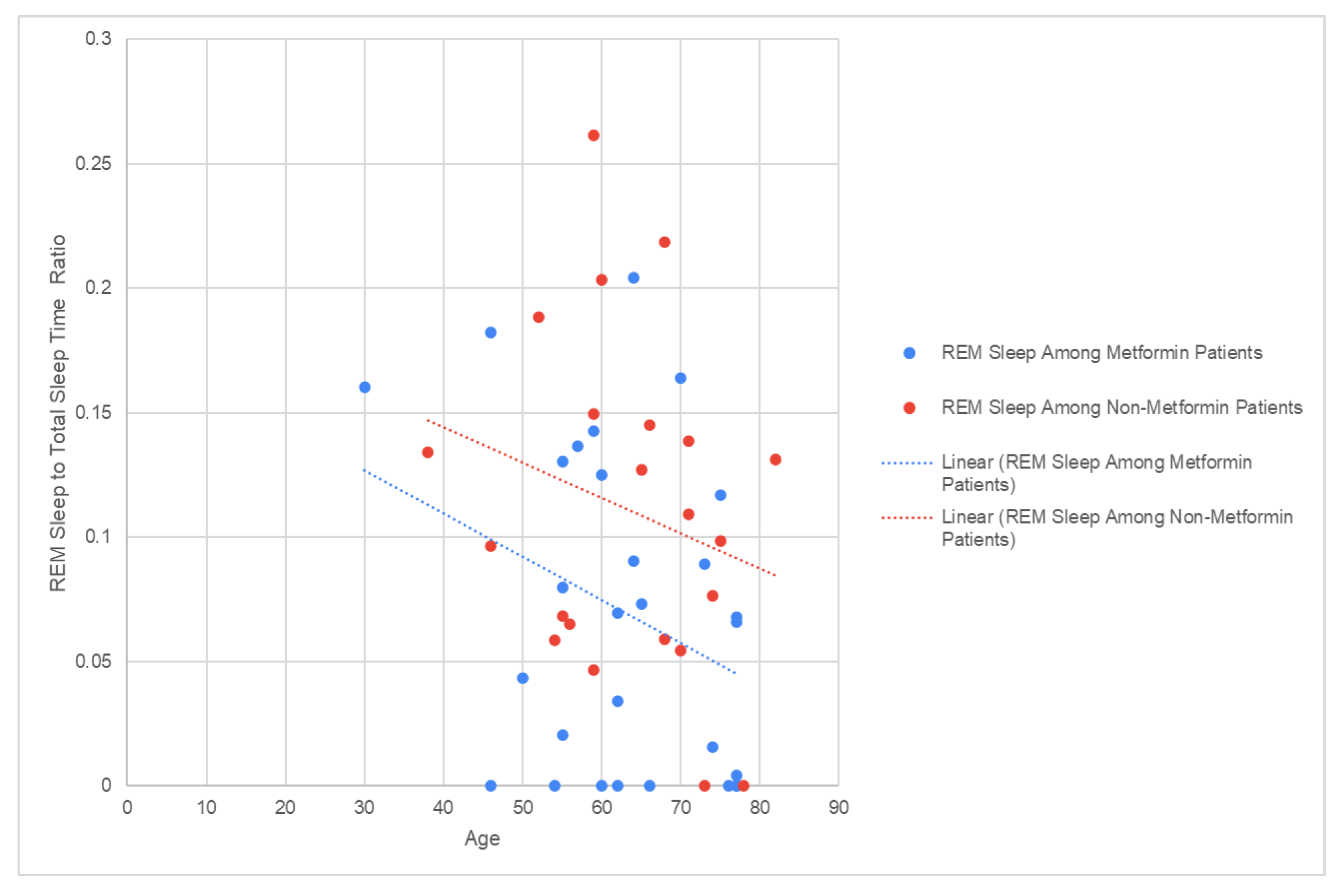

A linear regression analysis demonstrated that among patients using Metformin (R2 = 0.0965) and patients on alternative therapy (R2 = 0.052), REM sleep duration was not dependent on age (

Figure 3).

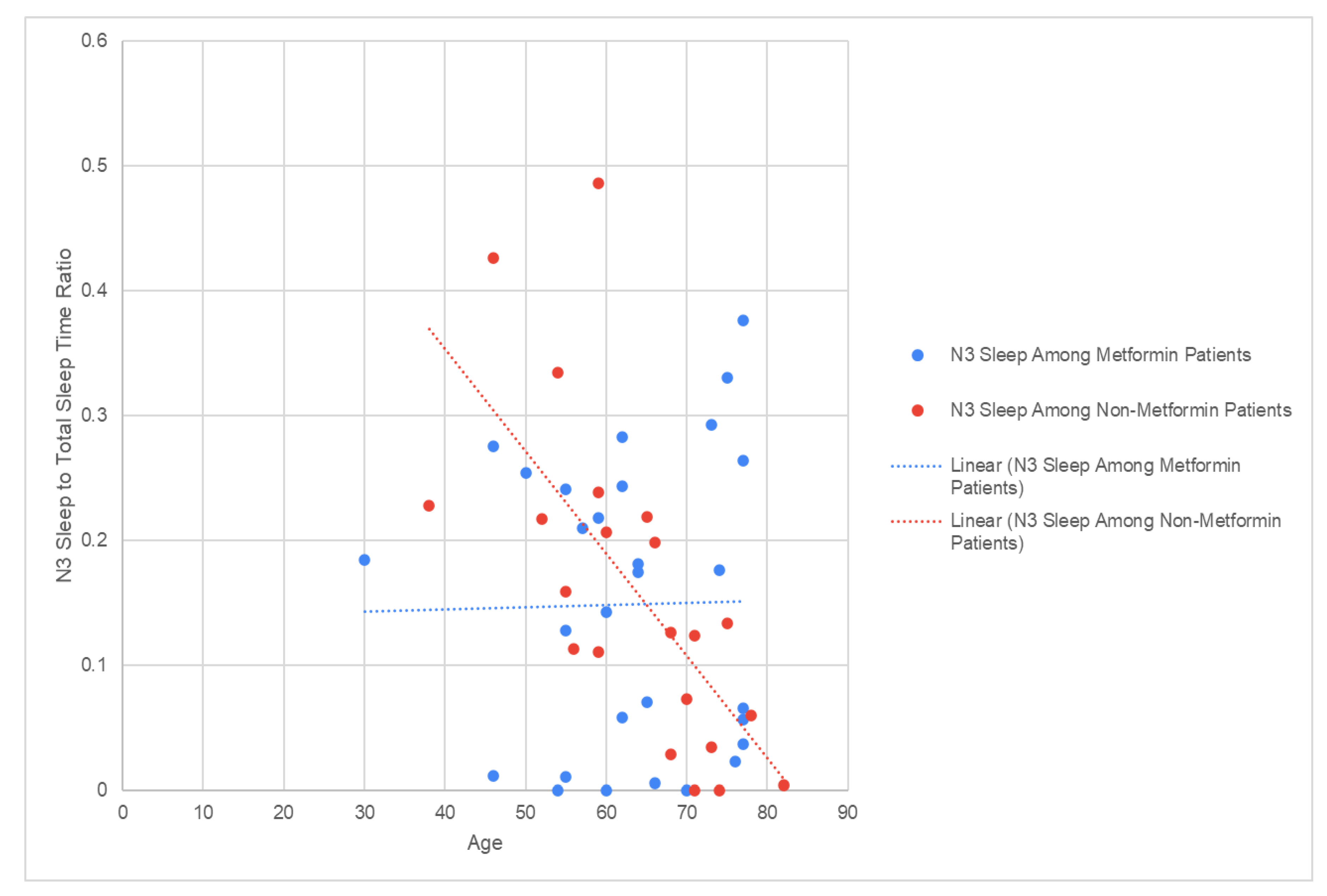

However, linear regression analysis also revealed a moderate inverse relationship between N3 sleep and age in non- Metformin patients (R2 = 0.4555) that does not appear in patients taking Metformin (R2 = 0.0003,

Figure 4).

Discussion: Both T2DM and OSA have been associated with noticeable effects on sleep architecture30, 31,32. For instance, both T2DM and higher HbA1c scores have been correlated with decreased duration of REM sleep20,22,30, 31,32. But while at least three independent case reports have documented patients with T2DM experiencing recurrent nightmares with Metformin use32, 33,34, there is limited existing research on whether Metformin alters sleep architecture. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to explore the relationship between T2DM, OSA, and Metformin and how they may jointly affect sleep architecture.

Our data shows that the percentage of REM sleep was significantly decreased in patients taking Metformin compared to those using other diabetes therapies. Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in the percentage of N3 sleep between patients taking Metformin versus those on alternative treatments.

Orexins may offer one potential explanation for the relationship between Metformin, glucose metabolism, and sleep architecture. Orexins (or hypocretins) are excitatory neurotransmitters that are synthesized in the hypothalamus and function to promote wakefulness and regulate REM sleep35, 36,37. Recent evidence indicates that orexins provide protection against development of peripheral insulin resistance as observed in older patients. Animal studies have shown that increased orexin receptor type 2 activity improves leptin sensitivity, thereby mitigating diet- induced obesity and insulin insensitivity38. Notably, orexin expression was found to be downregulated in hyperglycemic rodents with diabetes39.

Orexin activity is similarly decreased during REM sleep 40. This is relevant for patients on Metformin because a randomized trial in patients with T2DM found that 3-month treatment with Metformin not only improved insulin sensitivity but also increased serum orexin concentrations by 26% (p = 0.025). The same study also identified a negative correlation between serum orexin concentrations and insulin resistance (r = - 0.301, p = 0.024)40. Since increased orexin levels can promote waking and suppress REM, this may help explain the sleep disturbances experienced by patients taking Metformin41. This connection may be worthwhile investigating in future studies.

For decades, REM sleep has been implicated in memory consolidation. REM is characterized by aperiodic neural activity—an unsynchronized signal without oscillations on EEG—and a recent study by Lendner et al.42 demonstrated that this aperiodic activity is predictive of memory retention. It is also well-documented that aging is associated with changes in sleep architecture, specifically a decrease in REM sleep 43. An even greater decrease in REM sleep has been observed in elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease44. Our results suggest that patients with OSA and T2DM taking Metformin experience a decline in REM sleep that may compound the already decreased REM seen in aging patients, thereby possibly impacting both their memory and quality of life. However, additional research is needed to establish clinical significance.

The data does not demonstrate a significant relationship between REM or N3 sleep and biological sex, even though many previous studies have shown that non-diabetic female patients tend to spend more time in non-REM and less time in REM sleep than male patients45, 46. One possible reason our data differs from the existing literature is that many of the female patients in this study are older and peri- or postmenopausal, which is associated with a decline in female sex hormones.

Additionally, all the patients in this study were diagnosed with T2DM, whereas past studies focused on non-diabetic populations.

The lack of correlation between REM sleep and obesity was consistent with prior studies that found that obese and non-obese populations experienced similar durations of REM sleep 47. While obesity is one of the strongest risk factors for OSA, people with obesity can have varying levels of OSA severity. Of the U.S. adults who have been diagnosed with obesity, roughly 69% have some level of OSA, but only about 32% have moderate to severe OSA48. The different levels of OSA severity may, in turn, have different effects on REM sleep duration. While severe OSA has been linked to a decrease in REM sleep in obese adolescents, mild OSA has been linked to an increase in REM 48,49 further concluded that the odds ratio for symptoms of OSA in patients with increased BMI was 2.4, suggesting that many non-obese patients have OSA, and thus, changes in REM. Therefore, it may be reasonable to attribute the similarities in REM sleep between obese and non-obese populations to the wide range of OSA severity among these patients.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and that the study population was derived from Southern California, which may narrow the generalizability of these findings. Moreover, while our data revealed correlations between Metformin use and changes in sleep architecture, further studies would be required to identify causal relationships and clinical significance.

Conclusion: This study provides evidence that Metformin is associated with a decrease in REM sleep in patients with T2DM and OSA, and thus, a decline in sleep quality in these patients regardless of sex differences, smoking history, and BMI. Future studies using larger populations are needed to explore potential causes for such a decrease and how that relationship may affect the therapeutic options for patients with concurrent T2DM and sleep disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Madhu Varma; Methodology, Madhu Varma; Formal analysis, Kristen Masada and Daniel Nguyen; Investigation, Madhu Varma; Data curation, Daniel Nguyen; Writing – original draft, Kristen Masada and Daniel Nguyen; Writing – review & editing, Kristen Masada, Daniel Nguyen and Madhu Varma; Supervision, Madhu Varma; Project administration, Madhu Varma.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We conducted a retrospective community-based cohort study that was approved by California University of Science and Medicine IRB-HS-2020-11.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr A Sahai, Trika Medical Inc., and Mason Eghbali, MD, for their support and help with data collection. Support: CUSM Student Research Scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| T2DM |

Type 2 Diabetes |

| REM |

Rapid Eye Movement |

| OSA |

Obstructive Sleep Apnea |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

N1, N2, N3- Non REM stages of sleep, from lighter to deep

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report . 15 May 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Xu, G.; Liu, B.; Sun, Y.; Du, Y.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Hu, F.B.; Bao, W. Prevalence of diagnosed type 1 and type 2 diabetes among US adults in 2016 and 2017: Population based study. BMJ 2018, 362, k1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punjabi, N.M.; Shahar, E.; Redline, S.; Gottlieb, D.J.; Givelber, R.; Resnick, H.E. & Sleep Heart Health Study Investigators Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: The Sleep Heart Health Study. American journal of epidemiology 2004, 160(6), 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, L.V.; Jun, J.; Polotsky, V.Y. Obstructive sleep apnea. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; 2022; Volume 189, pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R.; Jones, E.A. Association and Risk Factors for Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Diseases 2021, 9(4), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnool, S.; McCowen, K.C.; Bernstein, N.A.; Malhotra, A. Sleep Apnea, Obesity, and Diabetes - an Intertwined Trio. Current diabetes reports 2023, 23(7), 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liang, C.; Zou, J.; Yi, H.; Guan, J.; Gu, M.; Feng, Y.; Yin, S. Interaction between obstructive sleep apnea and short sleep duration on insulin resistance: A large-scale study: OSA, short sleep duration and insulin resistance. Respiratory research 2020, 21(1), 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsohn, R.S.; Whitmore, H.; Van Cauter, E.; Tasali, E. Impact of untreated obstructive sleep apnea on glucose control in type 2 diabetes. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2010, 181(5), 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraki, I.; Wada, H.; Tanigawa, T. Sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes. Journal of diabetes investigation 2018, 9(5), 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutters, F.; Nefs, G. Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Disturbances in Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity: Targets and therapy 2022, 15, 3627–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidi, S.; Tasali, E. Obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes: Is there a link? Frontiers in neurology 2012, 3, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, J.E.; Rozenfeld, Y.; Kai, M.; Stephens, E.A.; Brown, L.K. Prevalence of diagnosed sleep apnea among patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care. Chest 2012, 141(6), 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. 8. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes care 2018, 41 Suppl 1, S73–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.W.; He, S.J.; Feng, X.; Cheng, J.; Luo, Y.T.; Tian, L.; Huang, Q. Metformin: A review of its potential indications. Drug design, development and therapy 2017, 11, 2421–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.; Lee, G.C. Emerging Trends in Metformin Prescribing in the United States from 2000 to 2015. Clinical drug investigation 2019, 39(8), 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foretz, M.; Guigas, B.; Viollet, B. Metformin: Update on mechanisms of action and repurposing potential. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 2023, 19(8), 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilawati, E.; Levita, J.; Susilawati, Y.; Sumiwi, S.A. Review of the Case Reports on Metformin, Sulfonylurea, and Thiazolidinedione Therapies in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Medical sciences 2023, 11(3), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiwanitkit, S.; Wiwanitkit, V. Metformin and insomnia: An interesting story. Diabetes & metabolic syndrome 2011, 5(3), 160. [Google Scholar]

- Yoda, K.; Inaba, M.; Hamamoto, K.; Yoda, M.; Tsuda, A.; Mori, K.; Imanishi, Y.; Emoto, M.; Yamada, S. Association between poor glycemic control, impaired sleep quality, and increased arterial thickening in type 2 diabetic patients. PloS one 2015, 10(4), e0122521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmaksoud, A.A.; Salah, N.Y.; Ali, Z.M.; Rashed, H.R.; Abido, A.Y. Disturbed sleep quality and architecture in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: Relation to glycemic control, vascular complications and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2021, 174, 108774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallayova, M.; Donic, V.; Gresova, S.; Peregrim, I.; Tomori, Z. Do differences in sleep architecture exist between persons with type 2 diabetes and nondiabetic controls? Journal of diabetes science and technology 2010, 4(2), 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.M.; Taporoski, T.P.; Alexandria, S.J.; Aaby, D.A.; Beijamini, F.; Krieger, J.E.; von Schantz, M.; Pereira, A.C.; Knutson, K.L. Altered sleep architecture in diabetes and prediabetes: Findings from the Baependi Heart Study. Sleep 2024, 47(1), zsad229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, M.; Eghbali, M.; Hung, D.; Sahai, A. Effect of insulin on sleep architecture in diabetic patients with sleep apnea. Sleep Medicine 2024, 115, S252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranski, T.; Eghbali, M.; Sahai, A.; Varma, M. Gender differences in sleep architecture of diabetic patients on metformin with sleep apnea: An analysis of polysomnography studies. Sleep Medicine 2024, 115 Suppl. 1, S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, J.; Covenant, A.; Hall, A.P.; Herring, L.; Rowlands, A.V.; Yates, T.; Davies, M.J. Waking Up to the Importance of Sleep in Type 2 Diabetes Management: A Narrative Review. Diabetes care 2024, 47(3), 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peever, J.; Fuller, P.M. The Biology of REM Sleep. Current biology: CB 2017, 27(22), R1237–R1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, M.; Eghbali, M.; Hung, D.; Sahai, A. FRI636 sleep architecture in diabetic patients with sleep apnea on metformin. Journal of the Endocrine Society 2023, 7 Supplement_1, A459–A460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, O.; Montplaisir, J.; Lamarre, M.; Bedard, M.A. The effect of gamma-hydroxybutyrate on nocturnal and diurnal sleep of normal subjects: Further considerations on REM sleep-triggering mechanisms. Sleep 1990, 13(1), 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, D.; Anderer, P.; Gruber, G.; Parapatics, S.; Loretz, E.; Boeck, M.; Kloesch, G.; Heller, E.; Schmidt, A.; Danker-Hopfe, H.; et al. Sleep classification according to AASM and Rechtschaffen & Kales: Effects on sleep scoring parameters. Sleep 2009, 32(2), 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, B.; Gunduz Gurkan, C.; Özol, D.; Saraç, S. The Effect of Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus on Sleep Architecture and Sleep Apnea Severity in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Cureus 2024, 16(5), e61215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahveisi, K.; Jalali, A.; Moloudi, M.R.; Moradi, S.; Maroufi, A.; Khazaie, H. Sleep Architecture in Patients With Primary Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Basic and clinical neuroscience 2018, 9(2), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanto, T.A.; Huang, I.; Kosasih, F.N.; Lugito, N.P.H. Nightmare and Abnormal Dreams: Rare Side Effects of Metformin? Case reports in endocrinology 2018, 2018, 7809305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloshyna, D.; Sandhu, Q.I.; Khan, S.; Bseiso, A.; Mengar, J.; Nayudu, N.; Kumar, R.; Khemani, D.; Usama, M. An Unusual Association Between Metformin and Nightmares: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14(9), e28974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, B.; Suravajjala, D.P.; Case, J.; Velumani, P. Metformin-induced nightmares: An uncommon event. Cureus 2024, 16(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, T.; Amemiya, A.; Ishii, M.; Matsuzaki, I.; Chemelli, R.M.; Tanaka, H.; Williams, S.C.; Richardson, J.A.; Kozlowski, G.P.; Wilson, S.; et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: A family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein- coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 1998, 92(4), 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, B.; Ray, L.B.; Pozzobon, A.; Fogel, S.M. Sleep, Orexin and Cognition. Frontiers of neurology and neuroscience 2021, 45, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.P.; Cherta-Murillo, A.; Darimont, C.; Mantantzis, K.; Martin, F.P.; Owen, L. The interrelationship between sleep, diet, and glucose metabolism. Sleep medicine reviews 2023, 69, 101788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funato, H.; Tsai, A.L.; Willie, J.T.; Kisanuki, Y.; Williams, S.C.; Sakurai, T.; Yanagisawa, M. Enhanced orexin receptor-2 signaling prevents diet-induced obesity and improves leptin sensitivity. Cell metabolism 2009, 9(1), 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.J.; Lister, C.A.; Buckingham, R.E.; Pickavance, L.; Wilding, J.; Arch, J.R.; Wilson, S.; Williams, G. Down-regulation of orexin gene expression by severe obesity in the rats: Studies in Zucker fatty and zucker diabetic fatty rats and effects of rosiglitazone. Brain research. Molecular brain research 2000, 77(1), 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogavero, M.P.; Godos, J.; Grosso, G.; Caraci, F.; Ferri, R. Rethinking the Role of Orexin in the Regulation of REM Sleep and Appetite. Nutrients 2023, 15(17), 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifkar, M.; Noshad, S.; Shahriari, M.; Afarideh, M.; Khajeh, E.; Karimi, Z.; Ghajar, A.; Esteghamati, A. Inverse Association of Peripheral Orexin-A with Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The review of diabetic studies: RDS 2017, 14, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendner, J.D.; Niethard, N.; Mander, B.A.; van Schalkwijk, F.J.; Schuh-Hofer, S.; Schmidt, H.; Knight, R.T.; Born, J.; Walker, M.P.; Lin, J.J.; et al. Human REM sleep recalibrates neural activity in support of memory formation. Science advances 2023, 9(34), eadj1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiritu, J.R. Aging-related sleep changes. Clinics in geriatric medicine 2008, 24(1), 1-v. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, M.; Forte, G.; Favieri, F.; Corbo, I. Sleep Quality and Aging: A Systematic Review on Healthy Older People, Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19(14), 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, R.; Qian, J.; Chellappa, S.L. Sex differences in sleep, circadian rhythms, and metabolism: Implications for precision medicine. Sleep medicine reviews 2024, 75, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morssinkhof, M.W.L.; van der Werf, Y.D.; van den Heuvel, O.A.; van den Ende, D.A.; van der Tuuk, K.; den Heijer, M.; Broekman, B.F.P. Influence of sex hormone use on sleep architecture in a transgender cohort. Sleep 2023, 46(11), zsad249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naufel, M.F.; Frange, C.; Andersen, M.L.; Girão, M.J.B.C.; Tufik, S.; Beraldi Ribeiro, E.; Hachul, H. Association between obesity and sleep disorders in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2018, 25(2), 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messineo, L.; Bakker, J.P.; Cronin, J.; Yee, J.; White, D.P. Obstructive sleep apnea and obesity: A review of epidemiology, pathophysiology and the effect of weight-loss treatments. Sleep medicine reviews Advance online publication. 2024, 78, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, O.; Kezirian, E.J.; Gillett, E.; Davidson Ward, S.L.; Khoo, M.; Perez, I.A. Association between REM sleep and obstructive sleep apnea in obese and overweight adolescents. Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 2019, 23(2), 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |