1. Introduction

Bone metastases are a frequent and serious complication of advanced cancers, particularly those originating from the prostate, breast, and lungs [

1,

2,

3]. These lesions are associated with significant morbidity, including intractable pain, pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, and hypercalcemia, which collectively reduce patient quality of life and increase health[4–6care burden [

4,

5,

6]. Radiopharmaceutical therapy targeting skeletal metastases has emer[4–6ged as a valuable strategy for palliative care, offering site-specific irradiation with minimal systemic toxicity [

7,

8,

9].

Among the established radiotherapeutics, β⁻-emitting agents such as

153Sm-EDTMP and

177Lu-EDTMP have been employed for decades, demonstrating clinical efficacy [

10,

11,

12,

13]. However, these first-generation polyphosphonate-based agents exhibit some limitations in terms of

in vivo stability and the need for high ligand concentrations due to weaker metal-ligand binding affinity [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The reduced kinetic stability and relatively modest specific activity of

177Lu-EDTMP could result in suboptimal bone targeting [

14,

15].

To address these drawbacks, macrocyclic chelators such as DOTA have been conjugated with bisphosphonatesto create more robust and selective bone-targeting radiopharmaceuticals- BPAMD. This complex combines the strong metal-chelating properties of DOTA with bisphosphonate moieties that exhibit high affinity for hydroxyapatite, the primary mineral component of bone. Radiolabeled with

177Lu, it demonstrated high radiolabeling yields, excellent

in vitro and

in vivo stability, and outstanding bone uptake [

14,

18,

19]. Moreover, the DOTA-based design of BPAMD allows it to function as a theranostic agent [

20,

15]. Gallium-68-labeled BPAMD has been successfully used for PET imaging of skeletal metastases, enabling precise localization and dosimetry before the therapeutic administration of the corresponding

177Lu-labeled compound [

21]. In early human studies,

177Lu-BPAMD showed strong accumulation in osteoblastic lesions and minimal uptake in soft tissues, with a favorable toxicity profile and significant pain reduction [

22]. Beyond

177Lu, BPAMD has also been successfully radiolabeled with other therapeutic β-emitting radionuclides, including

90Y,

175Yb, and

153Sm, for the palliative management of painful bone metastases, further demonstrating the adaptability and broad therapeutic potential of this bisphosphonate-based ligand in radionuclide therapy [

24,

25,

26,

27]. These findings collectively underscore the potential of macrocyclic bisphosphonates, such as BPAMD, to serve as adaptable and effective platforms for personalized treatment of skeletal metastatic disease [

15].

In recent years, terbium-161 (

161Tb) has attracted considerable interest as a therapeutic radionuclide due to its favorable physical and radiochemical characteristics [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Like

177Lu,

161Tb is a medium-energy β⁻ emitter with a similar physical half-life (~6.9 days) and energy profile [

32]. However,

161Tb offers an additional advantage: it emits a substantial number of low-energy Auger and internal conversion electrons, which deposit high linear energy transfer (LET) radiation over nanometer to micrometer ranges, making it suitable for the treatment of small and micrometastatic lesions [

33,

34]. This enhanced LET is particularly beneficial for targeting small tumor clusters and isolated tumor cells, where conventional β⁻ emitters may fall short [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

In addition to its therapeutic potential,

161Tb also emits low-energy γ-photons suitable for SPECT imaging, making it compatible with theranostic workflows [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. It can be stably coordinated by DOTA, and previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of radiolabeling DOTA-based molecules with terbium radionuclides [

30,

46]. Taken together, these properties position

161Tb as a compelling alternative to

177Lu, potentially offering enhanced therapeutic efficacy while retaining similar pharmacokinetics.

Despite these promising features, there is limited literature on 161Tb-labeled bisphosphonates. Given the proven performance of 177Lu-BPAMD and the additional cytotoxicity potential offered by 161Tb, it is logical to explore 161Tb-BPAMD as a next-generation bone-targeting radiopharmaceutical. The structural compatibility of BPAMD with both 177Lu and 161Tb supports this substitution without altering the pharmacokinetic behavior of the compound.

This study aims to investigate the radiolabeling efficiency, in vitro stability, and biodistribution characteristics of 161Tb-BPAMD. Radiolabeling was performed under practical conditions suitable for potential clinical translation, and the stability of the radiocomplex was assessed in saline and human serum. In vitro hydroxyapatite binding studies were conducted to confirm high mineral affinity, which is critical for effective skeletal targeting. Biodistribution experiments were performed in healthy Wistar rats to evaluate in vivo skeletal uptake and non-target tissue clearance. In parallel, ¹⁷⁷Lu-BPAMD was examined under comparable experimental conditions to provide a reference framework using a clinically established β⁻-emitting therapeutic. To complement the experimental data and provide insights into the coordination chemistry underlying the stability and pharmacokinetics of the Tb and Lu complexes, density functional theory (DFT) computational studies were performed. By systematically investigating these parameters, this study evaluates the potential of 161Tb-BPAMD as an improved bone-targeting therapeutic agent. If confirmed, 161Tb-BPAMD could provide enhanced radiation dose delivery at metastatic sites through the emission of short-range electrons, while retaining pharmacokinetics comparable to 177Lu-BPAMD, ultimately improving therapeutic efficacy and reducing systemic toxicity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

The ligand (4-{[(bis(phosphonomethyl))carbamoyl]methyl}-7,10-bis(carboxymethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododec-1-yl) acetic acid (BPAMD) was purchased from ABX (Radeberg, Germany). A stock solution of BPAMD was prepared by dissolving 1 mg of the ligand in 1 ml of ultrapure water and stored at 4 °C until use. All other chemical reagents, purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

No-carrier-added 161TbCl3 solution in 0.05 M HCl was provided by Terthera, Breda, The Netherlands, in a volume of 500 µL containing activity of 1 GBq. No-carrier-added 177LuCl₃ was supplied by ITG Isotope Technologies Garching GmbH (Munich, Germany) with a specific activity >500 GBq/mg Lu.

A 0.4 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) was freshly prepared from analytical-grade sodium acetate trihydrate and glacial acetic acid, with pH adjustment using 0.1 M HCl or NaOH. All aqueous solutions were prepared with ultrapure, deionized water obtained from a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

2.2. Equipment

A gamma counter (WIZARD 2480, PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) and a dose calibrator (CRC-15R beta, Capintec Inc., Ramsey, NY, USA) were used to measure the radioactivity of the samples. Radio-thin layer chromatography (radio-TLC) was performed using a Scan-RAM scanner (LabLogic Group, South Yorkshire, UK).

2.3. Radiolabeling of BPAMD with 177Lu

The radiolabeling of BPAMD with 177Lu was performed according to the methods described by Meckel et al. (2015) and Bergmann et al. (2016), with minor modifications to optimize reproducibility. Briefly, 74 MBq of 177LuCl3 was added in an aqueous solution containing 100 µg of BPAMD in 0.5 mL of sodium acetate buffer (0.4 M, pH 4.5). The reaction mixture was heated to 95 °C and maintained for 30 minutes. After heating, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature. The resulting solution was directly analyzed by radio-TLC without any further purification.

2.4. Radiolabeling of BPAMD with 161Tb

The labeling of BPAMD with 161Tb was performed under the same conditions as those for 177Lu. A solution of 100 µg BPAMD in 0.5 mL acetate buffer (0.4 M, pH 4.5) was mixed with 74 MBq of 161TbCl₃ and heated at 95 °C for 30 minutes in a sealed vial. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was analyzed by radio-TLC.

2.5. Radiochemical Purity Assessment

Radiochemical purity (RCP) was evaluated by radio-TLC using silica gel ITLC strips (ITLC-SG, Agilent Technologies). Briefly, 5 µL of the radiolabeled solution and a control sample of pure radionuclides were spotted on the strips and developed using two mobile phases: 1 M NaOH and ammonia/ethanol/water (1:10:20, v/v/v). After development up to 12 cm, the strips were dried and scanned with a gamma/TLC scanner. Under these conditions, the radiolabeled complexes migrated with the solvent front (Rf ≈ 1.0), while free radionuclides remained at the origin (Rf ≈ 0.0). RCP was calculated as the percentage of radioactivity associated with the complexes relative to total activity.

2.6. Radioelectrophoresis

Radioelectrophoresis was utilized to assess the net charge of the

161Tb-BPAMD complex and to validate the efficacy of radiolabeling. For each sample, 5 μL of either the radiolabeled complex or a control solution of

161TbCl

3 was placed at the center of Whatman 3MM chromatography paper strips (2 × 25 cm), which had been pre-soaked in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The strips were placed in an electrophoresis chamber filled with the same phosphate buffer, and electrophoresis was conducted at 250 V for 1 hour using a Gelman Instrument electrophoresis system (USA). After completing the radioelectrophoresis, each strip was dried and the distribution of radioactivity along the strip was then measured using a gamma/TLC scanner. This method allowed the determination of the migration pattern of the radiolabeled species in comparison to free

161Tb

3+, providing information about the charge and integrity of the formed complexes [

47].

2.7. Determination of Lipophilicity

The partition coefficient (log P) of the

161Tb-BPAMD complex was determined using the shake-flask method [

48]. Equal volumes (1 mL) of 1-octanol and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) were pre-equilibrated, and 100 µL of the radiolabeled complex was added. The mixture was vortexed for 1 minute and centrifuged at 3000 rpm to separate the phases. Radioactivity in both phases was measured using a gamma counter, and log P was calculated as the logarithm of the ratio of counts in the octanol to aqueous phase.

2.8. Protein Binding Assay

The extent of protein binding of 161Tb-BPAMD was assessed using the trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation method. Briefly, 100 µL of the radiolabeled complex was incubated with 500 µL of 12% (w/v) human serum albumin (HSA) solution (provided by the National Blood Transfusion Institute, Belgrade, Serbia) at 37 °C for 20 minutes. After incubation, 1 mL of 20% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to precipitate the protein-bound fraction. The mixture was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3000 rpm, and the resulting precipitate was rinsed with 0.9% NaCl. This procedure was repeated three times to ensure complete separation. The radioactivity of the precipitate (protein-bound fraction) and the supernatant (free fraction) was measured separately using a gamma counter. The percentage of protein-bound 161Tb-BPAMD was calculated as the ratio of the radioactivity in the pellet to the total radioactivity in the sample (pellet + supernatant), expressed as a percentage.

2.9. Hydroxyapatite Binding Assay

In vitro hydroxyapatite (HAP) binding affinity was evaluated to assess bone-targeting potential [

49]. Varying amounts (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg) of HAP powder were suspended in 2 mL of saline solution and pre-equilibrated by gentle shaking for 2 h. Subsequently, 50 µL of

161Tb-BPAMD was added and incubated for 24 hours at room temperature. Samples were centrifuged, and the radioactivity in the supernatant and pellet was measured. HAP binding was expressed as a percentage of total radioactivity bound to the solid phase.

2.10. In Vitro Stability Studies

The in vitro stability of 161Tb-BPAMD was evaluated in saline and human serum at 37 °C over 48 hours. Radiolabeled aliquots were incubated in the respective media, and at defined intervals (2, 24, and 48 hours), samples were analyzed using radio-TLC described above to determine the percentage of intact complex versus free radioisotope.

2.11. Biodistribution Studies

Biodistribution experiments were carried out in healthy Wistar rats (100–120 g,

n = 3 per time point) obtained from a colony of the Military Medical Academy (Belgrade, Serbia). Animals were kept under a 12 h light-dark cycle, controlled room temperature (21±2 ⁰C), humidity (40-45%), and illumination (120 lx). All animal procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Vinča Institute of Nuclear Sciences (permission No. 002225501 2025, issued on 20 May 2025) and were in accordance with the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 [

50]. Rats were injected intravenously via the tail vein with 0.1 mL of

177Lu-BPAMD or

161Tb-BPAMD (~0.74 MBq). At 2 h, 24 h, and 7 d post-injection, animals were euthanized, and organs of interest (blood, heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, stomach, intestines, muscle, and femur) were excised, weighed, and counted in a gamma counter. The results were expressed as the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). All data are expressed as a percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g, mean ± SD,

n = 3).

2.12. Computational Details

The geometry optimization and energy minimization have been performed at BP86 level of theory [

51]. For heavy lanthanide Tb

3+ ion SARC2-DKH-QZVP basis set has been applied, and for all other atoms DKH-def2-SVP basis set has been used [

52]. Also, SARC/J auxiliary basis set, which is a decontracted def2/J auxiliary set, that is more accurate for relativistic calculations has been used [

53,

54,

55,

56].

3. Results and Discussion

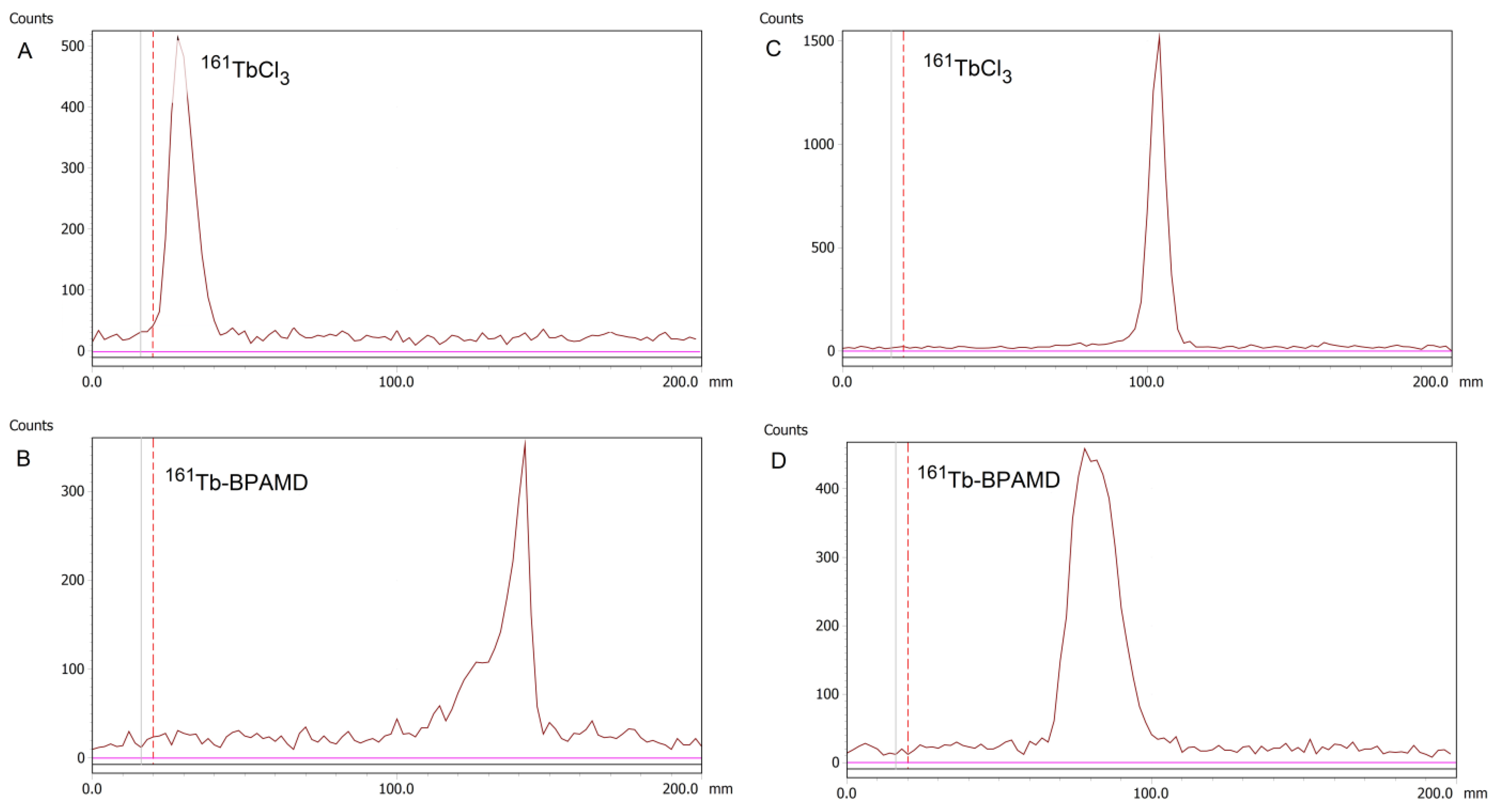

3.1. Radiolabeling Efficiency and Radioelectrophoresis

Radiolabeling of BPAMD with

161Tb and

177Lu was successfully performed under identical conditions, mildly acidic pH (4.5) and elevated temperature (95 °C) for 30 minutes, resulting in high radiolabeling yields exceeding 98% for both radionuclides. The labeling yield for

161Tb-BPAMD is presented in

Figure 1B, while the yield for

177Lu-BPAMD agrees with previously reported values for analogous DOTA-conjugated bisphosphonates radiolabeled with

177Lu or

68Ga [

18,

57,

58]. Owing to the high incorporation efficiency and negligible presence of unbound

161TbCl₃, post-labeling purification was not required, simplifying the preparation process for further

in vitro and

in vivo applications. Further experiments were carried out only for

161Tb-BPAMD, whereas

177Lu-BPAMD was included only in the biodistribution study in healthy Wistar rats to enable direct comparison with the

161Tb-labeled analogue. Radio-TLC of free

161TbCl

3 is shown in

Figure 1A.

The net charge of the complex was further confirmed by radioelectrophoresis, performed at physiological pH (7.4). Under these conditions,

161Tb-BPAMD migrated toward the positively charged anode, consistent with its negatively charged complex nature (

Figure 1D). In contrast, free

161TbCl

3 remained at the origin (Rf = 0), indicating neutral or colloidal hydrolyzed terbium species (

Figure 1C). These findings confirm quantitative chelation of terbium (III) and the absence of any detectable colloidal aggregates or hydrolysis products under physiological pH and ionic strength.

3.2. Protein Binding and Lipophilicity

The plasma protein binding value for

161Tb-BPAMD was determined to be 19.07

± 1.01%, indicating a low affinity toward plasma proteins

. This low protein-binding profile of

161Tb-BPAMD is particularly advantageous, as high plasma protein association can slow systemic clearance, promote hepatic uptake, and increase the risk of non-target radiation exposure [

22,

59,

60]. Therefore,

161Tb-BPAMD is expected to clear more rapidly from the circulation, thereby enhancing its therapeutic index. Furthermore, the measured log P of –3.92 ± 0.13 confirms the complex’s high hydrophilicity, consistent with other macrocyclic bisphosphonates [

15,

61]. This physicochemical profile suggests predominant renal excretion and minimal penetration across lipid-rich biological barriers. Hydrophilic radiocomplexes are often favored for skeletal applications, as they exhibit high bone-to-soft tissue ratios due to limited hepatic uptake and rapid blood clearance [

15,

62]. Consequently, the combination of low protein binding and high hydrophilicity supports the potential of

161Tb-BPAMD as a selective skeletal radiotherapeutic agent.

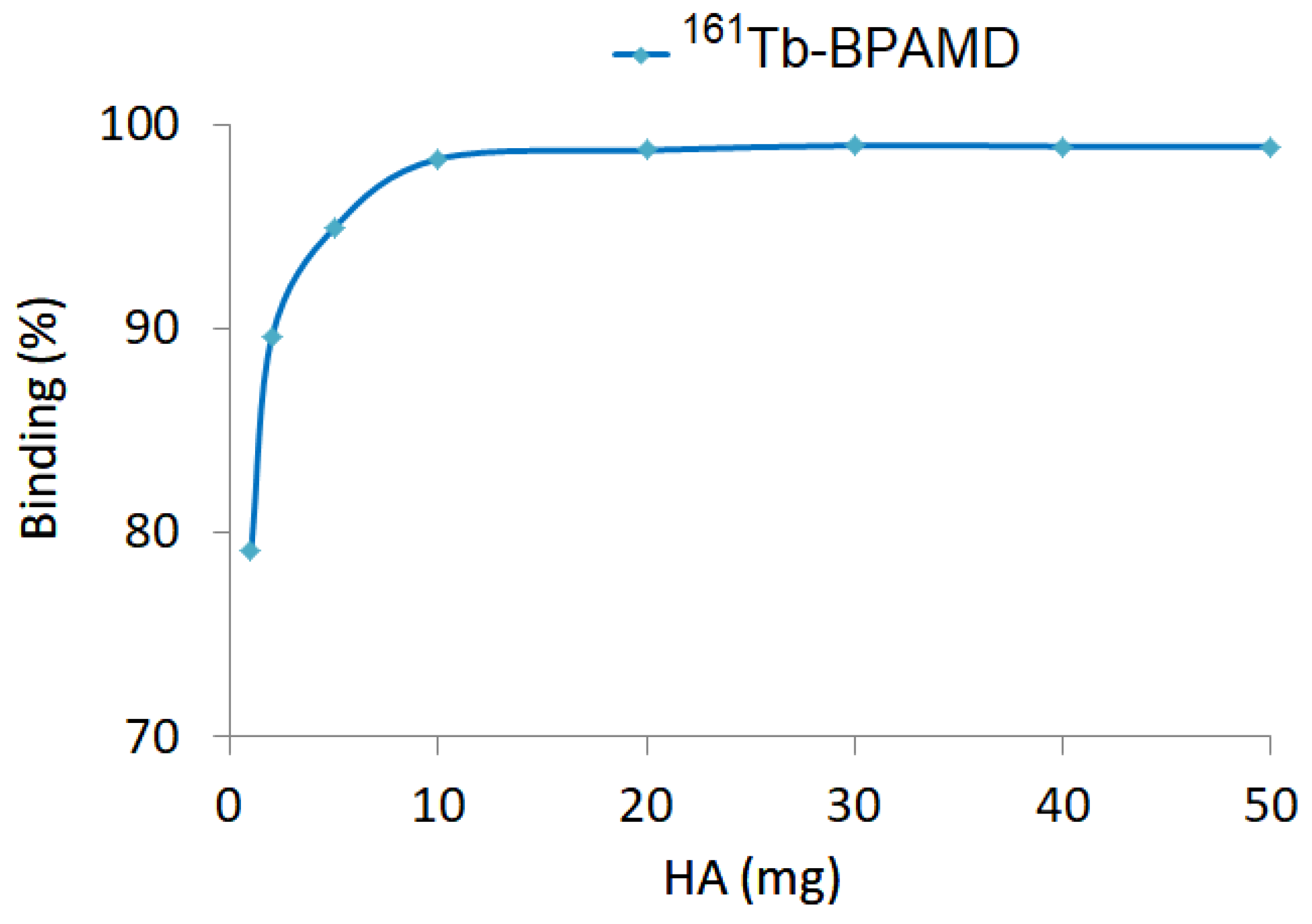

3.3. Hydroxyapatite Binding

Hydroxyapatite (HA) binding studies of

161Tb-BPAMD revealed high-affinity, concentration-dependent interaction following 24-hour incubation with increasing HA quantities (1–50 mg). Binding efficiency exceeded 98% at HA concentrations ≥10 mg (

Figure 2), indicating rapid saturation. This profile closely parallels that of

177Lu-BPAMD, which similarly reached a binding plateau at relatively low HA levels [

49]. The rapid saturation indicates that the bisphosphonate moieties within BPAMD possess sufficient affinity to achieve near-maximal binding even under conditions of limited mineral content, such as in early-stage osteoblastic lesions.

These results are consistent with known properties of bisphosphonate-based radiopharmaceuticals, which exhibit strong chemisorption to calcium phosphate surfaces through their phosphonate groups [

63,

64,

65]. Effective skeletal targeting requires a high HAP binding capacity, particularly when minimizing uptake in non-calcified tissues and delivering therapeutic radiation doses to bone metastases.

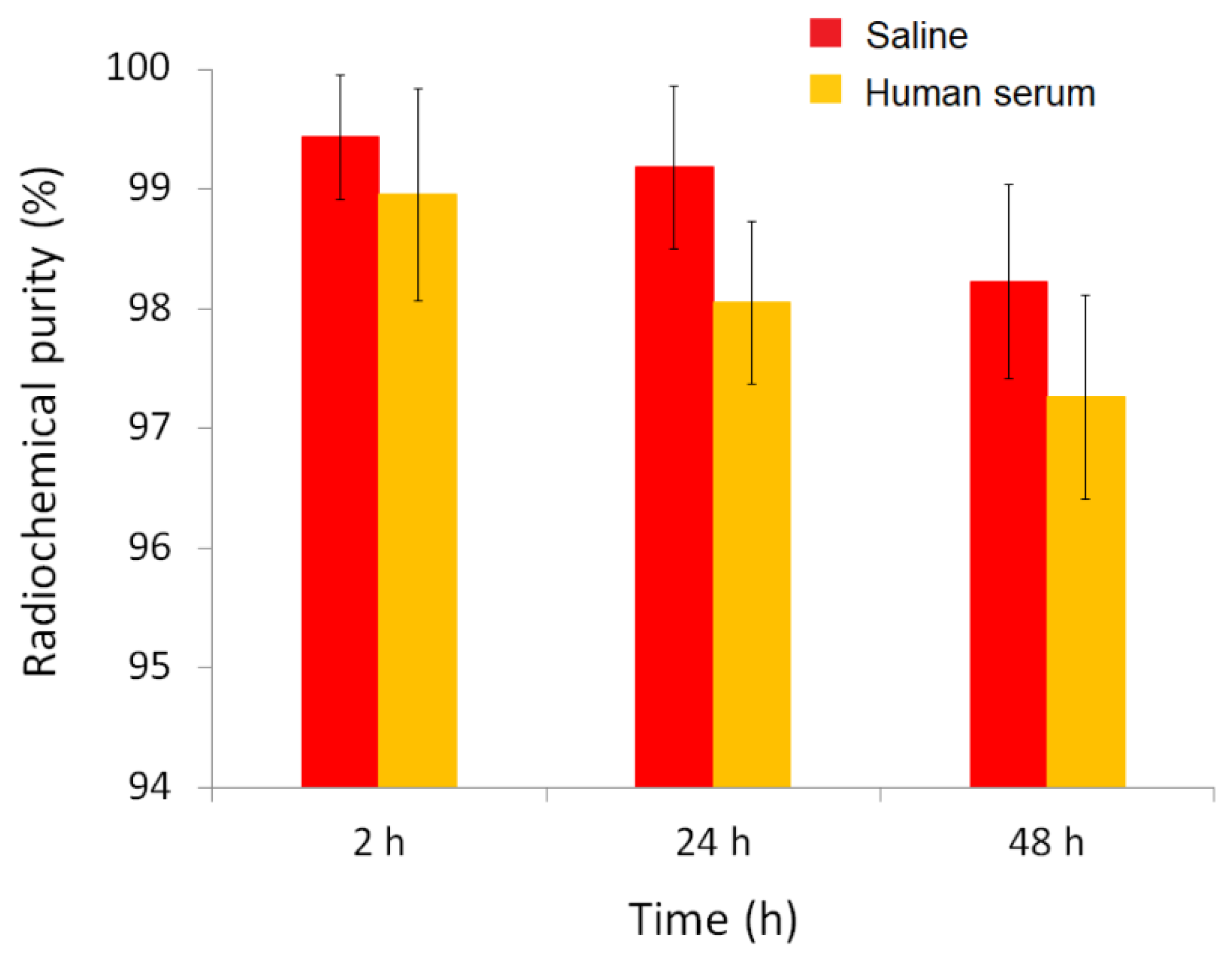

3.4. In Vitro Stability

The

in vitro stability of the radiolabeled complex

161Tb-BPAMD was evaluated in both physiological saline and human serum at 37 °C over a period of 48 hours (

Figure 3). The results demonstrated that the complex exhibits excellent radiochemical stability under simulated physiological conditions. In saline, radiochemical purity remained remarkably high throughout the entire observation period, with values of 99.43 ± 0.52% at 2 hours

, 99.18 ± 0.68% at 24 hours

, and 98.22 ± 0.81% at 48 hours, indicating negligible degradation or dissociation of the complex. Similarly, in human serum, where biological components such as proteins and ions could potentially interfere with the stability of the radiometal complex,

161Tb-BPAMD maintained high integrity, with 98.95 ± 1.09% at 2 hours

, 98.05 ± 0.68% at 24 hours

, and 97.26 ± 0.85% at 48 hours

. Although a slight decrease in radiochemical purity was observed over time in serum, the values remained consistently above 97%, confirming that the complex resists transchelation and remains stable in the presence of endogenous biomolecules. This slight decrease is unlikely to be clinically significant, as the radiopharmaceutical's uptake into bone is nearly complete within the first few hours post-injection, before any substantial degradation occurs. These findings match previous results for

177Lu-BPAMD and other DOTA-chelated bisphosphonates [

49], and confirm that

161Tb-BPAMD is highly stable

in vitro, supporting its potential for further

in vivo evaluation and application in bone-targeted radionuclide therapy.

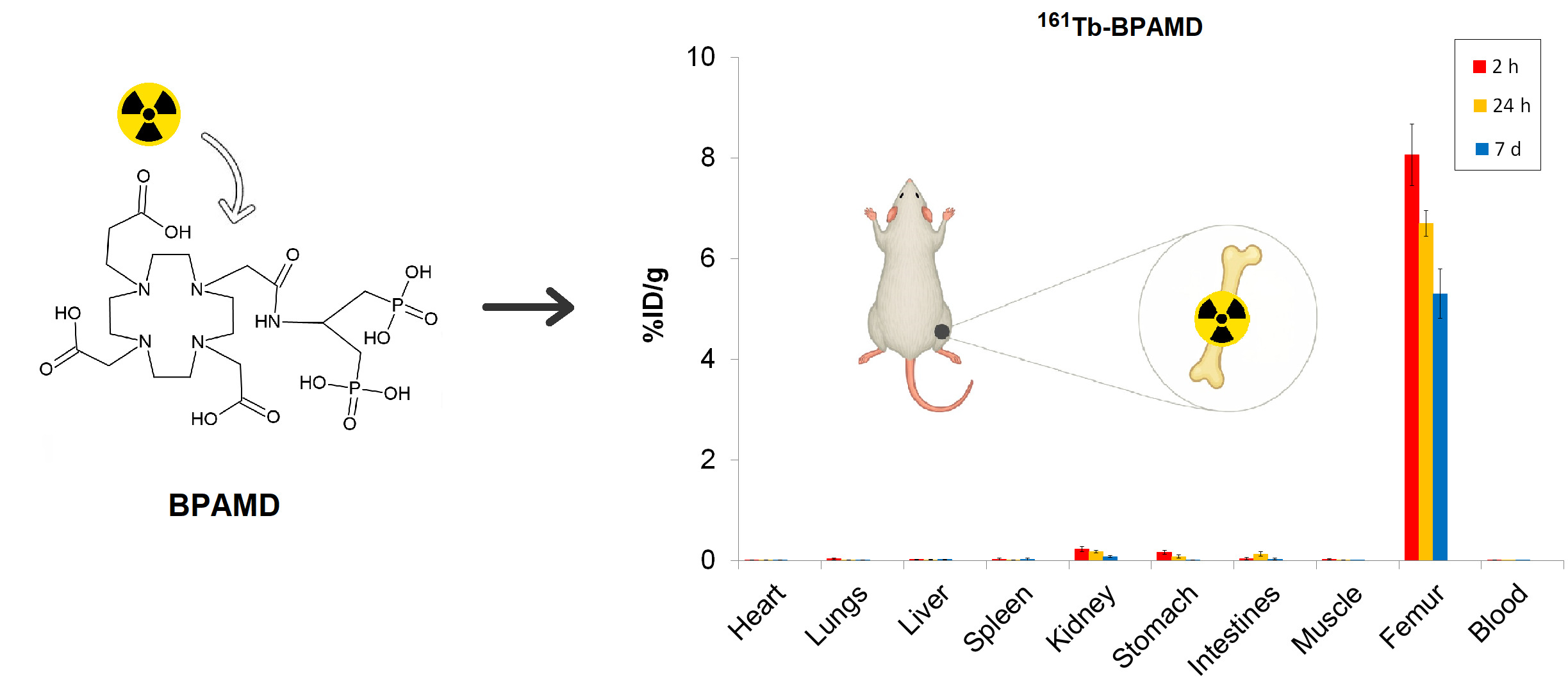

3.5. Biodistribution Studies of 161Tb-BPAMD and 177Lu-BPAMD

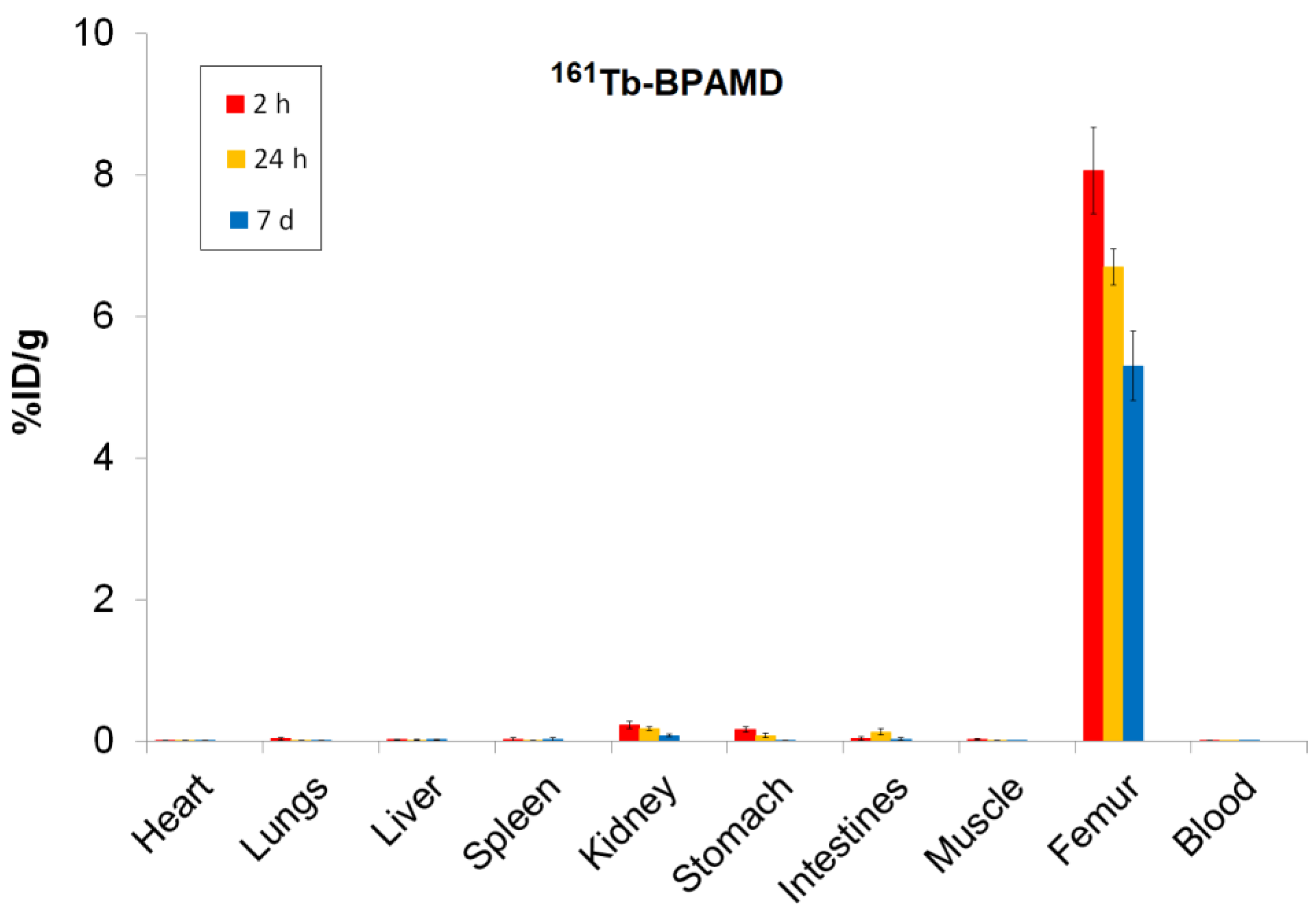

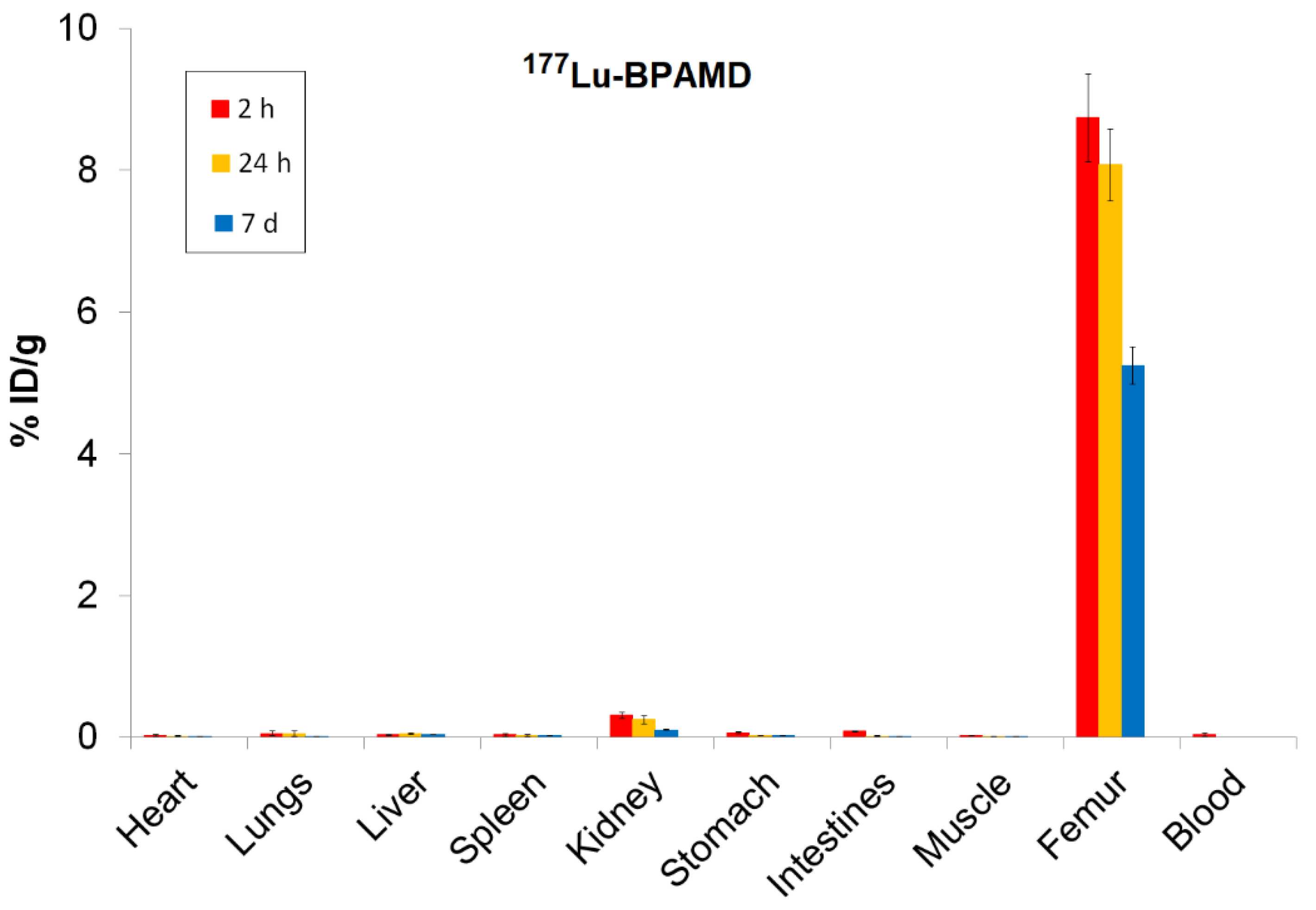

Biodistribution analysis of

161Tb-BPAMD and

177Lu-BPAMD in healthy Wistar rats provides insights into the therapeutic potential of both radiopharmaceuticals. For

161Tb-BPAMD (

Figure 4), bone uptake remained high across all measured time points (8.06 ± 0.61 %ID/g at 2 h; 6.70 ± 0.26 %ID/g at 24 h; 5.31 ± 0.49 %ID/g at 7 days), demonstrating stable skeletal retention. A comparable pattern was observed for

177Lu-BPAMD (

Figure 5), which exhibited slightly higher early bone accumulation (8.74 ± 0.62 %ID/g at 2 h) and similarly stable retention at later time points (8.08 ± 0.51 %ID/g at 24 h; 5.25 ± 0.27 %ID/g at 7 days). These results confirm that both radiopharmaceuticals effectively target bone tissue and maintain prolonged residence, which is essential for therapeutic irradiation of metastatic lesions and palliation of bone pain.

Despite their similar skeletal kinetics, notable differences emerged in soft-tissue distribution. 161Tb-BPAMD displayed consistently low uptake in major organs such as the liver, spleen, muscle, and blood, with mean values typically below 0.03 %ID/g and minimal variability. Kidney uptake was higher at early time points (0.23 ± 0.05 %ID/g at 2 h) but declined substantially by day 7 (0.08 ± 0.02 %ID/g), indicating efficient clearance. In contrast, 177Lu-BPAMD demonstrated higher soft-tissue activity at early time points, particularly in the kidneys (0.31 ± 0.04 %ID/g at 2 h; 0.25 ± 0.06 %ID/g at 24 h), as well as slightly higher liver and lung uptake, relative to 161Tb.

The target-to-non-target ratios presented in

Table 1 support the findings from the biodistribution data and further highlight the distinct performance profiles of

161Tb-BPAMD and

177Lu-BPAMD. Notably, these ratios highlight a key advantage of

161Tb-BPAMD: its enhanced selectivity for bone compared to major organs. Bone/liver ratios are consistently higher for

161Tb at all time points, particularly at 24 h (352.7 vs. 161.5), reflecting markedly lower hepatic retention relative to bone. A similar pattern is observed for bone/kidney ratios, where

161Tb achieves higher values at each time point, especially at 7 days (66.3 vs. 50.0). This trend corresponds directly with the biodistribution findings, where

161Tb exhibited lower soft-tissue uptake, faster non-target clearance, and a pronounced decline in kidney activity over time. These properties indicate a more favorable biodistribution profile, with reduced non-target radiation that may translate into improved therapeutic tolerability. Bone/spleen ratios follow the same trend, with

161Tb showing a noticeable advantage after 24 h (468.7 vs. 269.2). These patterns suggest that

161Tb-BPAMD offers more favorable target-to-background ratios over time, with reduced nonskeletal retention and faster washout from soft tissues.

These results indicate that both 161Tb-BPAMD and 177Lu-BPAMD are highly effective bone-targeting radiopharmaceuticals, with comparable and clinically relevant skeletal uptake profiles. However, 161Tb-BPAMD demonstrates superior biodistribution selectivity, as reflected by lower soft-tissue accumulation and declining kidney values over time, which may translate into reduced non-target radiation exposure. Combined with the advantageous emission profile of 161Tb-particularly the presence of low-energy conversion and Auger electrons that enhance dose deposition in small-scale disease, these results indicate that terbium expands the therapeutic potential of BPAMD-based agents beyond what is achievable with 177Lu alone. Therefore, while 177Lu-BPAMD remains a robust and well-validated option for bone pain palliation, 161Tb-BPAMD emerges as a promising and potentially superior alternative, offering enhanced selectivity and an expanded therapeutic spectrum.

3.6. Computational Studies

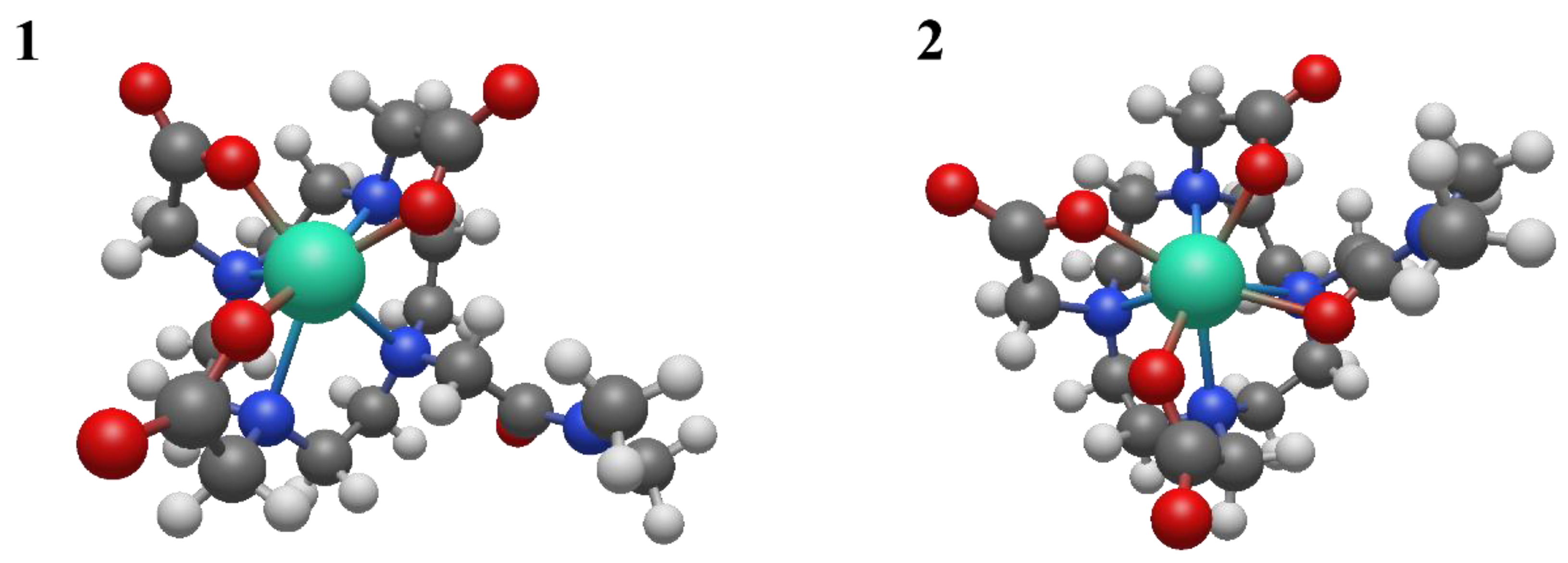

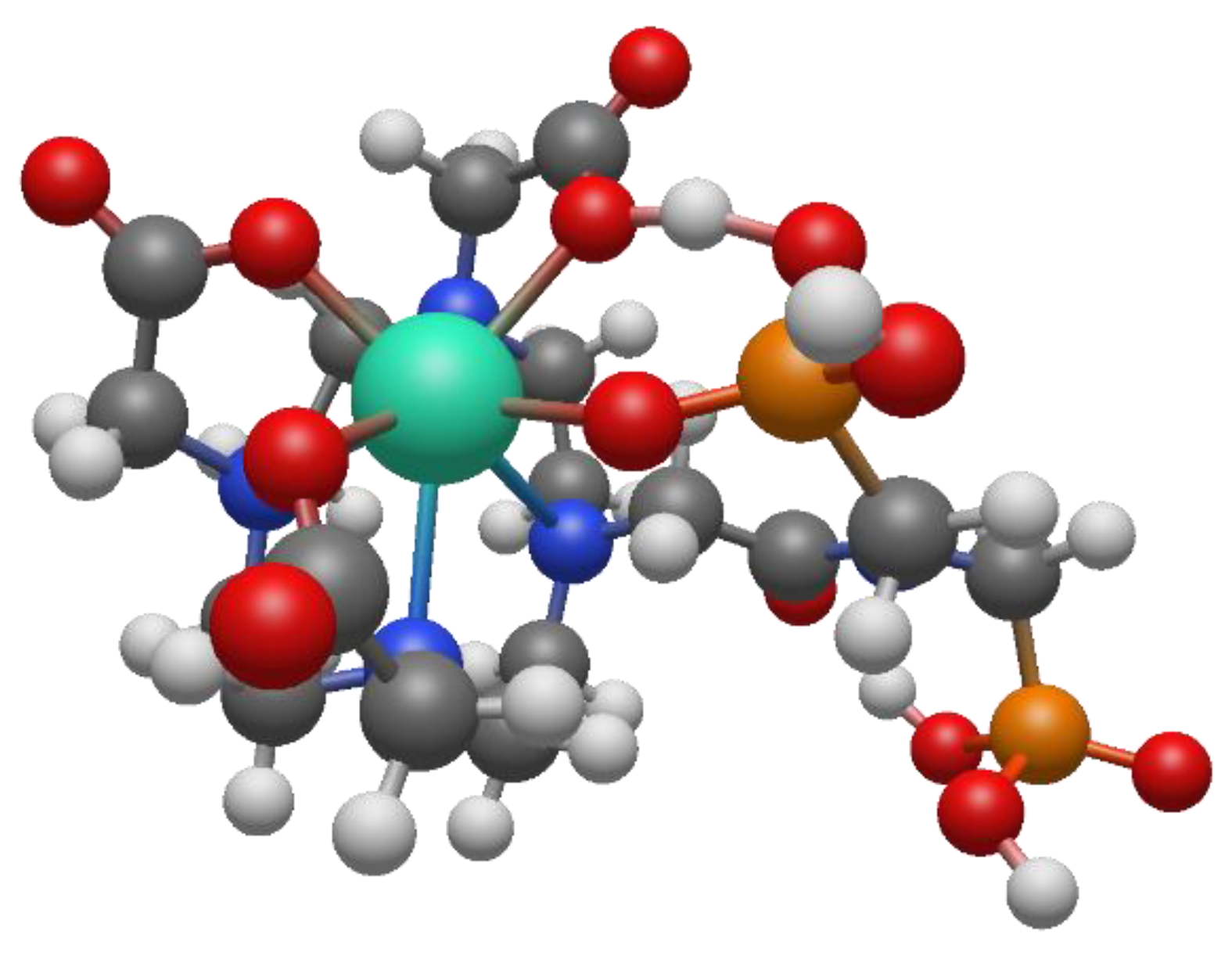

To better understand the coordination chemistry of terbium and lutetium with the BPAMD ligand, two initial structures were analyzed, shown in

Figure 6.

The BPAMD ligand is modified by replacing the phosphonate groups with hydrogen atoms, so the amid nitrogen carries methyl substituents. BPAMD ligand is modified to avoid possible interactions with phosphonate groups. That allowed us to explore only the coordinative bond with the amid branch. The first structure assumed the hepta-coordination of the chelate ligand, while the second structure assumed the octa-coordination of the modified BPAMD ligand. The geometric optimization of structure

1 did not lead to any changes in the way of coordination. The absence of negative vibrational modes indicated that optimization resulted in an energy minimum. Also, the optimization of the second, octa-coordinated, structure did not show any changes in the mode of coordination. These findings are the same, regardless of the metal coordinated, terbium or lutetium. Compared with the second structure, the first structure of terbium has approximately 14 kcal/mol more energy (

Table 2).

Based on the data in

Table 2, it is evident that nuclear repulsions favor structure

1, while electronic stabilization favors structure

2. However, entropic factors favor structure

1, with the largest contribution being vibrational entropy. In structure

1, the non-coordinated amid branch is oriented in such a way that it is maximally distant from terbium and other coordinated groups. By moving to structure

2, all groups are brought closer together, thereby increasing nuclear repulsive interactions. At the same time, the binding of all groups to terbium in the octa-coordinated structure

2 leads to a decrease in electronic energy.

The vibrational entropy of a ligand typically decreases when it binds to a metal. This reduction in entropy results from the ligand becoming more constrained in its movements upon forming a bond with the metal, limiting the number of vibrational modes available. Vibrational entropy is related to the number and types of vibrations a molecule can undergo. These vibrations include bond stretching, bending, and twisting. When a ligand binds to a metal, it forms a complex where the ligand is held in a specific orientation and conformation. This binding restricts the ligand's ability to rotate, translate, and vibrate freely, thereby reducing the number of accessible vibrational modes. This is exactly what happens when free amid branch coordinates to terbium.

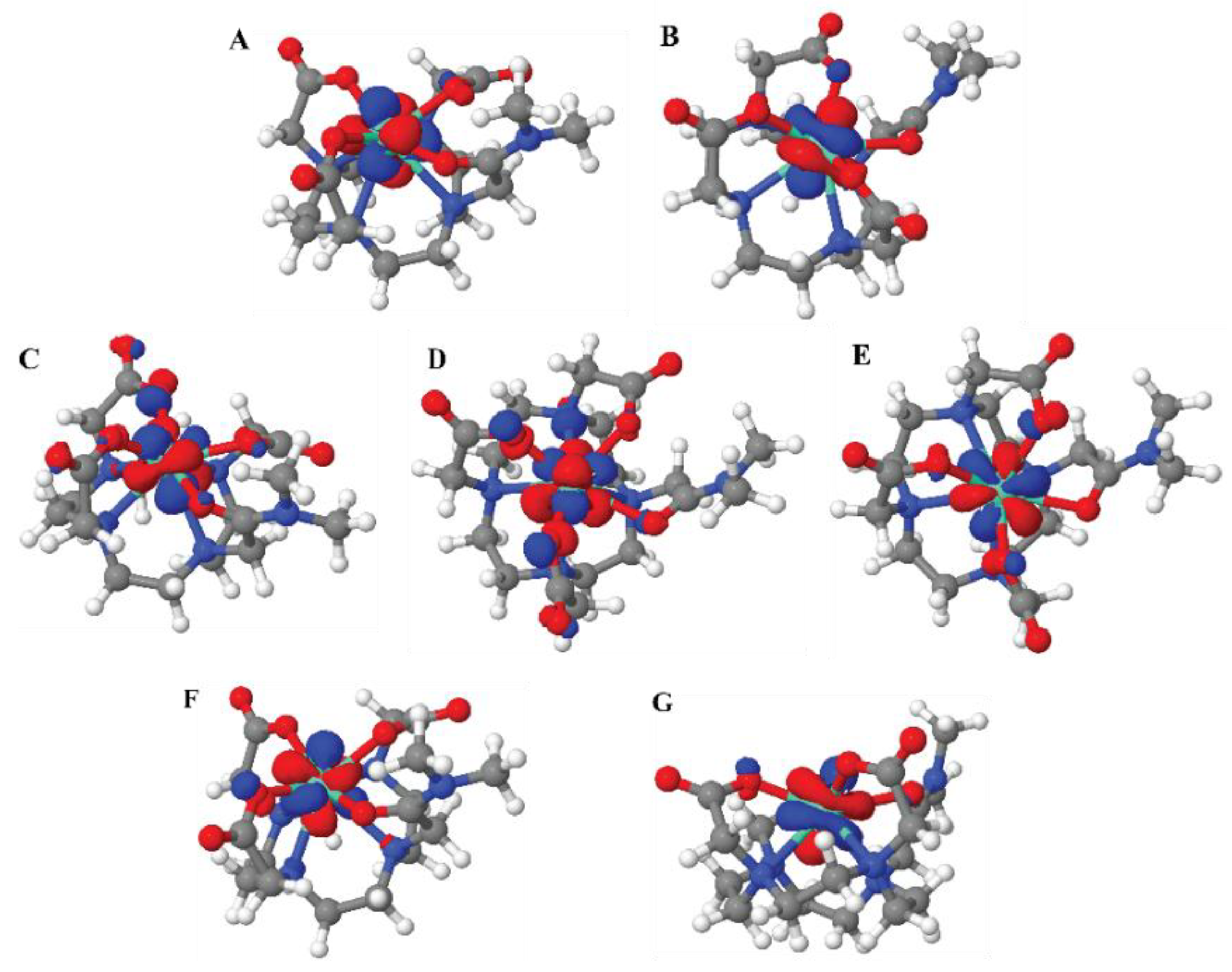

The dominant interaction in lanthanide-ligand bonding is electrostatic, meaning it's primarily due to the attraction between the positively charged lanthanide ion and the negatively charged or electron-rich portions of the ligand. Lanthanides act as hard Lewis acids, favoring interactions with hard ligands (those with high charge density and low polarizability). The 4f electrons in lanthanides are deeply buried within the atom's core and are generally not involved in bonding interactions. The molecular orbitals with dominant f-character for structure

2 are shown in

Figure 7.

The ionic radius of the lanthanide ion plays a significant role in binding with chelating ligands. Due to lanthanide contraction, ΔG for the interchange between structures

1 and

2 can significantly vary through the lanthanide series. Thus, for example, the ΔG for the transition from structure

1 to structure

2 for equivalent Lu

3+ complexes is -8,13 kcal/mol (DFT analysis at the same level of theory). A much lower ΔG for the transition from hepta-coordinated to octa-coordinated complex of lutetium indicates that the larger terbium ion has a stronger tendency towards higher coordination numbers. However, regardless of the lanthanide used, both metals prefer octa-coordination. This behavior is more obvious if the actual BPAMD ligand is used for coordination. If optimization starts with an octa-coordinated structure (amide branch), energy minimization leads to the structure with the same coordination number eight. However, if geometry optimization starts from the hepta-coordinated initial structure, energy minimization leads to an octa-coordinated structure via one phosphonate group (

Figure 8).

DFT calculations showed that the energy difference between octa-coordinated structures via the oxygen of the phosphonate group and via the oxygen of the amid group is negligible. In the case of the Tb3+ complex, octa-coordinated structures via the phosphonate group are favored by just 0,4 kcal/mol. In the case of Lu3+ complex with BPAMD, the octa-coordinated structure via phosphonate group is 1,42 kcal/mol higher in energy than the other octa-coordinated structure.

4. Conclusion

161Tb-BPAMD was successfully prepared with high radiochemical yield, excellent in vitro stability, and strong hydroxyapatite affinity. Its low plasma protein binding, high hydrophilicity, and rapid systemic clearance contribute to a biodistribution profile characterized by selective and stable skeletal uptake with minimal non-target retention. Although both 161Tb-BPAMD and 177Lu-BPAMD demonstrate effective and clinically relevant bone targeting, 161Tb-BPAMD exhibits more selective biodistribution, reflected in lower soft-tissue accumulation and decreasing kidney activity over time. Moreover, while its pharmacokinetic and binding characteristics closely mirror those of 177Lu-BPAMD, 161Tb-BPAMD offers the added therapeutic advantage of high-LET Auger and conversion electrons, potentially enhancing dose delivery to metastatic bone lesions, particularly micrometastases, while reducing systemic toxicity. DFT geometry optimizations of Tb3+ and Lu3+ BPAMD model complexes support a preferred octa-coordinated binding mode, with the octa-coordinated structures thermodynamically favored over a hepta-coordinated alternative (ΔG = -14.4 kcal/mol for Tb3+; -8.1 kcal/mol for Lu3+). The small energy separation between alternative octa-coordination patterns suggests a flexible coordination environment that can accommodate different lanthanides without compromising the stability of the complex. Taken together, these findings highlight 161Tb-BPAMD as a highly promising candidate for clinical translation, providing targeted, effective, and stable radiation delivery to skeletal metastases, with an improved therapeutic profile compared with existing BPAMD-based agents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.R.,P.S.,A.V. ; validation, A.V., and D.S.; formal analysis, S.V.-Đ., and M.M. (Marija Mirković); investigation, M.M. (Miloš Marić), and D.J.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S., M.M. (Miloš Marić), and D.S.; software, M.P., A.V.; writing—review and editing, D.J., and M.R.; visualization, M.P., and M.M. (Marija Mirković); supervision, M.R., S.V.-Đ., and A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia under contract 451-03-136/2025-03/200017, the bilateral Serbia-NR China project No. 003417078 2024 013440 003 000 620 021, and the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, Grant No. 7282, Project RADIOMAG.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of “VINČA” Institute of Nuclear Sciences (permission No. 002225501 2025, issued on 20 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- Lo Bianco, G. et al., Multimodal Clinical Approach for Treatment of Bone Metastases in Solid Tumors. Anesthesiol. Pain Med. 2022, vol. 12(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.; Maxwell, C.; Ryan, C.; Löthman, H.; Drudge-Coates, L.; Costa, L. Bone metastases from advanced cancers: Clinical implications and treatment options. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2009, vol. 13(no. 6), 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paes, F. M.; Serafini, A. N. Systemic Metabolic Radiopharmaceutical Therapy in the Treatment of Metastatic Bone Pain. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2010, vol. 40(no. 2), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C. et al., Incidence and radiotherapy treatment patterns of complicated bone metastases. J. Bone Oncol. 2024, vol. 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errani, C. Treatment of Bone Metastasis. Curr. Oncol. 2022, vol. 29(no. 8), 5195–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouvrard, E.; Kaseb, A.; Poterszman, N.; Porot, C.; Somme, F.; Imperiale, A. Nuclear medicine imaging for bone metastases assessment: what else besides bone scintigraphy in the era of personalized medicine? Front. Med. 2023, vol. 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Kampen, W. U. Radionuclide therapy of bone metastases. Breast Care 2012, vol. 7(no. 2), 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit-Taskar, N.; Batraki, M.; Divgi, C. R. Radiopharmaceutical therapy for palliation of bone pain from osseous metastases. J. Nucl. Med. 2004, vol. 45(no. 8), 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra Liberal, F. D. C.; Tavares, A. A. S.; Tavares, J. M. R. S. Palliative treatment of metastatic bone pain with radiopharmaceuticals: A perspective beyond Strontium-89 and Samarium-153. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2016, vol. 110, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R. A. [153Sm]EDTMP: A potential therapy for bone cancer pain. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1992, vol. 22(no. 1), 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-González, L.; De Murphy, C. A.; Pichardo-Romero, P.; Pedraza-López, M.; Moreno-García, C.; Correa-Hernández, L. 153Sm-EDTMP for pain relief of bone metastases from prostate and breast cancer and other malignancies. Arch. Med. Res. 2014, vol. 45(no. 4), 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resche, I. et al., A dose-controlled study of 153Sm- ethylenediaminetetramethylenephosphonate (EDTMP) in the treatment of patients with painful bone metastases. Eur. J. Cancer 1997, vol. 33(no. 10), 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máthé, D. et al., Multispecies animal investigation on biodistribution, pharmacokinetics and toxicity of 177Lu-EDTMP, a potential bone pain palliation agent. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2010, vol. 37(no. 2), 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S. et al., Formulation of ‘ready-to-use’ human clinical doses of 177Lu-labeled bisphosphonate amide of DOTA using moderate specific activity 177Lu and its preliminary evaluation in human patient. Radiochim. Acta 2020, vol. 108(no. 8), 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, R. et al., 177Lu-labelled macrocyclic bisphosphonates for targeting bone metastasis in cancer treatment. EJNMMI Res. 2016, vol. 6(no. 1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kálmán, F. K.; Király, R.; Brücher, E. Stability constants and dissociation rates of the EDTMP complexes of Samarium(III) and Yttrium(III). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, no. 30, 4719–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, G. J. et al., The influence of EDTMP-concentration on the biodistribution of radio- lanthanides and 225-Ac in tumor-bearing mice. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1997, vol. 24(no. 5), 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckel, M. et al., Development of a [177Lu]BPAMD labeling kit and an automated synthesis module for routine bone targeted endoradiotherapy. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2015, vol. 30(no. 2), 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Goswami, D.; Chakravarty, R.; Mohammed, S. K.; Sarma, H. D.; Dash, A. Syntheses and evaluation of 68Ga- and 153Sm-labeled DOTA-conjugated bisphosphonate ligand for potential use in detection of skeletal metastases and management of pain arising from skeletal metastases. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2018, vol. 92(no. 3), 1618–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfannkuchen, N. et al., Novel radiolabeled bisphosphonates for PET diagnosis and endoradiotherapy of bone metastases. Pharmaceuticals 2017, vol. 10(no. 2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guleria, M. et al., Convenient formulation of 68Ga-BPAMD patient dose using lyophilized BPAMD Kit and 68Ga sourced from different commercial generators for imaging of skeletal metastases. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2019, vol. 34(no. 2), 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA, *!!! REPLACE !!!* (Ed.) Pain palliation of bone metastases: production, quality control and dosimetry of radiopharmaceuticals; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiei, A.; Shamsaei, M.; Yousefnia, H.; Zolghadri, S.; Jalilian, A. R.; Enayati, R. Development and biological evaluation of 90Y-BPAMD as a novel bone seeking therapeutic Agent. Radiochim. Acta 2016, vol. 104(no. 10), 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefnia, H.; Enayati, R.; Hosntalab, M.; Zolghadri, S.; Bahrami-Samani, A. Samarium-153-(4-[((bis (phosphonomethyl)) carbamoyl) methyl]-7,10-bis (carboxymethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododec-1-yl) acetic acid: A novel agent for bone pain palliation therapy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2016, vol. 12(no. 3), 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabie, A. et al., Preparation, quality control and biodistribution assessment of 153Sm-BPAMD as a novel agent for bone pain palliation therapy. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2015, vol. 29(no. 10), 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaez-Tehrani, M.; Zolghadri, S.; Afarideh, H.; Yousefnia, H. Preparation and biological evaluation of 175Yb-BPAMD as a potential agent for bone pain palliation therapy. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016, vol. 309(no. 3), 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefnia, H.; Amraei, N.; Hosntalab, M.; Zolghadri, S.; Bahrami-Samani, A. Preparation and biological evaluation of 166Ho-BPAMD as a potential therapeutic bone-seeking agent. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2015, vol. 304(no. 3), 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, S. et al., Contribution of Auger/conversion electrons to renal side effects after radionuclide therapy: preclinical comparison of 161Tb-folate and 177Lu-folate. EJNMMI Res. 2016, vol. 6(no. 1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracheva, N. et al., Production and characterization of no- carrier-added $^{161}$Tb as an alternative to the therapy. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2019, vol. 4:12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nizou, G. et al., Expanding the Scope of Pyclen-Picolinate Lanthanide Chelates to Potential Theranostic Applications. Inorg. Chem. 2020, vol. 59(no. 16), 11736–11748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laere, C. et al., Terbium radionuclides for theranostic applications in nuclear medicine: from atom to bedside. Theranostics 2024, vol. 14(no. 4), 1720–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, M. T. et al., Determination of 161Tb half-life by three measurement methods. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2020, vol. 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoormans, K.; Struelens, L.; Vermeulen, K.; De Saint-Hubert, M.; Koole, M.; Crabbé, M. The Emission of Internal Conversion Electrons Rather Than Auger Electrons Increased the Nucleus-Absorbed Dose for 161 Tb Compared with 177 Lu with a Higher Dose Response for [ 161 Tb]Tb-DOTA-LM3 Than for [ 161 Tb]Tb-DOTATATE. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, jnumed.124.267873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer-Ávila, M. E.; Ferreira, A.; Quinto, M. A.; Morgat, C.; Hindié, E.; Champion, C. Radiation doses from 161Tb and 177Lu in single tumour cells and micrometastases. EJNMMI Phys. 2020, vol. 7(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, A.; Facca, V. J.; Cai, Z.; Reilly, R. M. Auger electrons for cancer therapy – a review. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2019, vol. 4(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindie, E.; Zanotti-Fregonara, P.; Quinto, M. A.; Morgat, C.; Champion, C. Dose deposits from90Y,177Lu,111In, and161Tb in micrometastases of various sizes: Implications for radiopharmaceutical therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, vol. 57(no. 5), 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, P. et al., Dosimetric analysis of the short-ranged particle emitter161 tb for radionuclide therapy of metastatic prostate cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021, vol. 13(no. 9), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falzone, N. et al., Dosimetric evaluation of radionuclides for VCAM-1- targeted radionuclide therapy of early brain metastases. Theranostics 2018, vol. 8(no. 1), 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, C.; Quinto, M. A.; Morgat, C.; Zanotti-Fregonara, P.; Hindié, E. Comparison between three promising β-emitting radionuclides, 67Cu, 47Sc and 161Tb, with emphasis on doses delivered to minimal residual disease. Theranostics 2016, vol. 6(no. 10), 1611–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C. et al., Direct in vitro and in vivo comparison of 161Tb and 177Lu using a tumour-targeting folate conjugate. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, vol. 41(no. 3), 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koniar, H. et al., Quantitative SPECT imaging of 155Tb and 161Tb for preclinical theranostic radiopharmaceutical development. EJNMMI Phys. 2024, vol. 11(no. 1), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, R. P. et al., First-in-human application of terbium-161: A feasibility study using 161Tb-DOTATOC. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, vol. 62(no. 10), 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C. et al., Terbium-161 for PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy of prostate cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, vol. 46(no. 9), 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C. et al., A unique matched quadruplet of terbium radioisotopes for PET and SPECT and for α- and β--radionuclide therapy: An in vivo proof-of-concept study with a new receptor-targeted folate derivative. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, vol. 53(no. 12), 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgna, F. et al., Combination of terbium-161 with somatostatin receptor antagonists—a potential paradigm shift for the treatment of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, vol. 49(no. 4), 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M. et al., Evaluation in vitro and in rats of161Tb-DTPA-octreotide, a somatostatin analogue with potential for intraoperative scanning and radiotherapy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1995, vol. 22(no. 7), 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirković, M. et al., Investigation of 177Lu-labeled HEDP, DPD, and IDP as potential bone pain palliation agents. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2020, vol. 13(no. 1), 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirković, M. et al., Novel tetradentate diamine dioxime ligands: Synthesis, characterization and in vivo behavior of their 99mTc-complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2012, vol. 26(no. 7), 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefnia, H.; Zolghadri, S.; Sadeghi, H. R.; Naderi, M.; Jalilian, A. R.; Shanehsazzadeh, S. Preparation and biological assessment of 177Lu-BPAMD as a high potential agent for bone pain palliation therapy: comparison with 177Lu-EDTMP. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016, vol. 307(no. 2), 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament, Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes, vol. L 276. European Union: EUR-Lex, 2010, pp. 33–79. [Online]. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/63/oj/eng.

- Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, vol. 38(no. 6), 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, vol. 8(no. 9), 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, D. A.; Neese, F. All-electron scalar relativistic basis sets for the lanthanides. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, vol. 5(no. 9), 2229–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, D. A.; Chen, X. Y.; Landis, C. R.; Neese, F. All-electron scalar relativistic basis sets for third-row transition metal atoms. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, vol. 4(no. 6), 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, D. A.; Neese, F. All-electron scalar relativistic basis sets for the 6p elements. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2012, vol. 131(no. 11), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, D. A.; Neese, F. All-Electron Scalar Relativistic Basis Sets for the Actinides. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, vol. 7(no. 3), 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souche, C. et al., Towards Optimal Automated 68Ga-Radiolabeling Conditions of the DOTA-Bisphosphonate BPAMD Without Pre-Purification of the Generator Eluate. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2024, vol. 67(no. 14), 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, M. et al., 68Ga-BPAMD: PET-imaging of bone metastases with a generator based positron emitter. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2012, vol. 39(no. 7), 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C. M.; Benet, L. Z. An examination of protein binding and protein-facilitated uptake relating to in vitro-in vivo extrapolation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, vol. 123, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnert, T.; Gan, L. S. Plasma protein binding: From discovery to development. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, vol. 102(no. 9), 2953–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gano, L.; Marques, F.; Campbello, M. P.; Balbina, M.; Lacerda, S.; Santos, I. Radiolanthanide complexes with tetraazamacrocycles bearing methylphosphonate pendant arms as bone seeking agents. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2007, vol. 51(no. 1), 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, K. Biocomplexes in radiochemistry. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2019, vol. 1(no. 5), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puljula, E.; Turhanen, P.; Vepsäläinen, J.; Monteil, M.; Lecouvey, M.; Weisell, J. Structural requirements for bisphosphonate binding on hydroxyapatite: NMR study of bisphosphonate partial esters. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, vol. 6(no. 4), 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nancollas, G. H. et al., Novel insights into actions of bisphosphonates on bone: Differences in interactions with hydroxyapatite. Bone 2006, vol. 38(no. 5), 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souche, C.; Fouillet, J.; Rubira, L.; Donzé, C.; Deshayes, E.; Fersing, C. Bisphosphonates as Radiopharmaceuticals: Spotlight on the Development and Clinical Use of DOTAZOL in Diagnostics and Palliative Radionuclide Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, vol. 25(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).