Submitted:

07 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

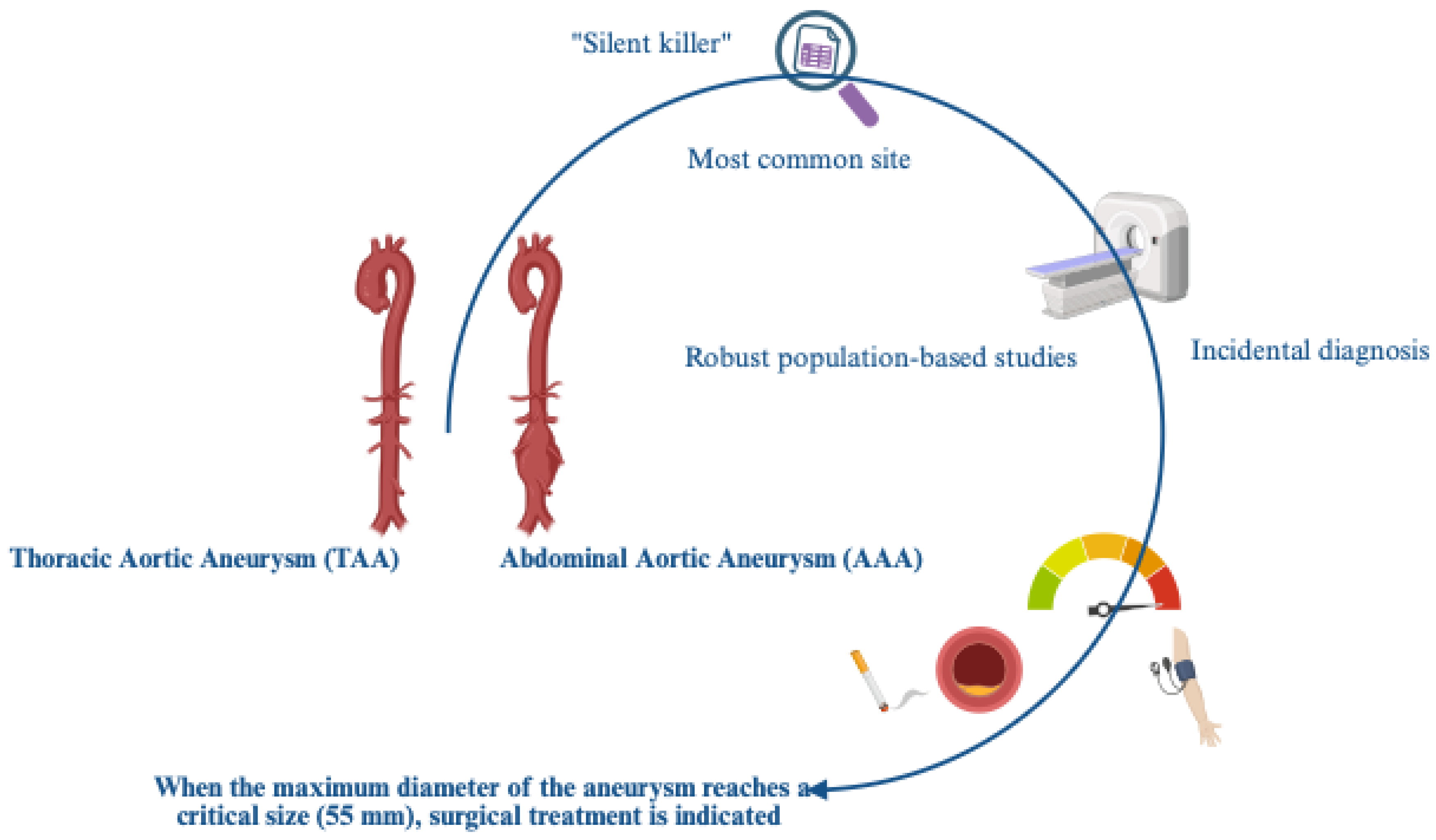

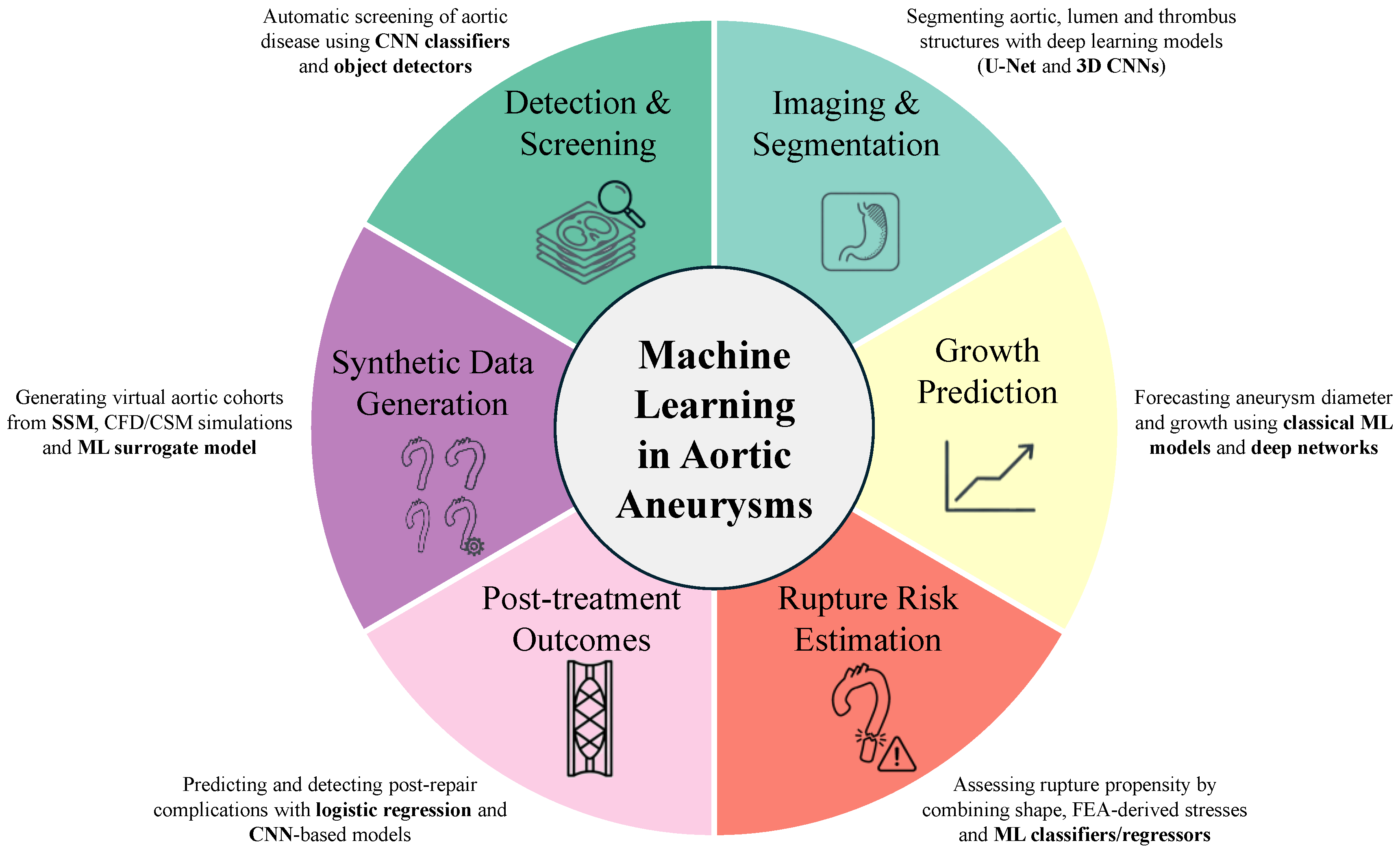

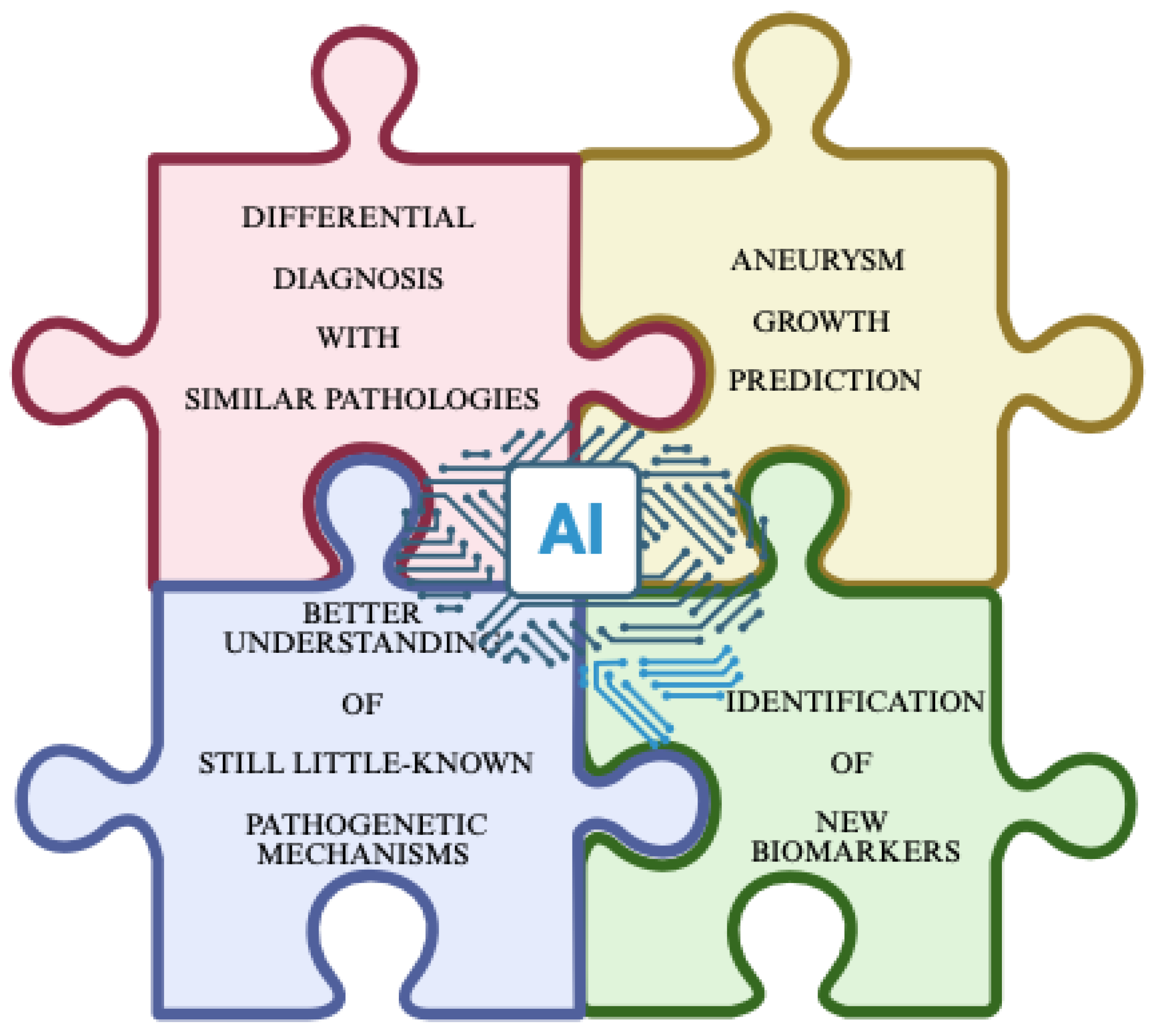

Aortic aneurysms (AAs), both abdominal and thoracic, remain one of the most fatal cardiovascular emergencies, with a growing prevalence and incidence, especially for sporadic forms in our populations, which are primarily comprised of elderly individuals. A high mortality risk also appears to be linked to managerial delays, despite advances in imaging techniques that facilitate the difficult diagnosis, and in surgical procedures. This is the result of the clinical decision-making approach, which is unfortunately still based, as per guidelines, on the maximum aortic diameter. This parameter, as suggested, fails to capture the biological and biomechanical complexity underlying these pathological conditions, which are influenced, among other things, by entirely individual factors (genetics, gender, lifestyle, etc.). With the emergence of network medicine and omics sciences, diverse and complex sets of clinical, imaging, and biomarker data are now available. These could be precisely processed by artificial intelligence (AI), enabling accurate prediction of AA risk and facilitating its complex management. Therefore, AI could represent an excellent tool for AAs, showing the potential not only to refine AA risk prediction but also to radically transform the way we understand, monitor, and manage AA patients, despite some limitations. These aspects are the subject of this review, as are their therapeutic applications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. AI: What Is it? Its Features, Advantages, Limits, and Instances from Deep Learning Techniques to Digital Twins

3. An AI Clinical Application in the Complex Case of Aortic Aneurysms? The Initial Panoramic

3.1. The Challenge and Unpromising Solutions

4. AI as Potential Solution of AA and Literature Evidence

4.1. Deep Learning Techniques as Aid in Evaluating the Aorta Size

4.1.1. Considerations

4.2. Deep Learning Techniques as Aid in Evaluating Biomechanical Indicators

4.3. Advanced Prediction Models and Synthetic Data Generation

5. Biomarkers and AI in Aortic Aneurysm

6. AI and Prognosis in Aortic Aneurysms

7. AI as Aid in Predicting Risk Assessment of AA, and in Selecting the Appropriate Therapeutic Strategy: A Particular Focus on TAA, Being Less Studied than AAA

7.1. Experimental Evidence

8. Discussion and Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altucci, L; Badimon, L; Balligand, JL; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Network Medicine: Path to Precision Medicine. NEJM AI 2025, 2(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla B, Afridi S, Vayolipoyil S, et al. The Evolving Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Science: Advancing Diagnostics, Clinical Decision-Making, and Research. Cureus. Published online September 3, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chong, PL; Vaigeshwari, V; Mohammed Reyasudin, BK; et al. Integrating artificial intelligence in healthcare: applications, challenges, and future directions. Future Sci OA 2025, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant S, Deepika, Roy S. Integrative Multi-Omics and Artificial Intelligence: A New Paradigm for Systems Biology. OMICS. Published online November 7, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wörheide, MA; Krumsiek, J; Kastenmüller, G; Arnold, M. Multi-omics integration in biomedical research – A metabolomics-centric review. Anal Chim Acta 2021, 1141, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghareeb, E; Aljehani, N. AI in Health Care Service Quality: Systematic Review. JMIR AI 2025, 4, e69209–e69209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X; Li, Y; Xu, J; Zheng, Z; Ying, F; Huang, G. AI in Medical Questionnaires: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e72398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, SA; Al-jabri, MM. Artificial Intelligence Applications in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Their Impact on Nursing Practice and Patient Outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2025, 57(6), 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y; Nakayama, M; Aldana, CF; Alvino, F. Persona-driven generative AI in pharmaceuticals. Drug Discov Today 2025, 30(12), 104520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loriga, B; Baglivo, F; Bellini, V; et al. Top three priorities for artificial intelligence integration into emergency, critical, and perioperative medicine: an interdisciplinary clinical expert consensus. Journal of Anesthesia, Analgesia and Critical Care 2025, 5(1), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki Varnosfaderani, S; Forouzanfar, M. The Role of AI in Hospitals and Clinics: Transforming Healthcare in the 21st Century. Bioengineering 2024, 11(4), 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, S; Bhatia, R; Liem, M; Wani, TA; Boyd, J; Raza Khan, U. Opportunities and Challenges of Using Artificial Intelligence in Predicting Clinical Outcomes and Length of Stay in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e63175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahim, YA; Hasani, IW; Kabba, S; Ragab, WM. Artificial intelligence in healthcare and medicine: clinical applications, therapeutic advances, and future perspectives. Eur J Med Res. 2025, 30(1), 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wubineh, BZ; Deriba, FG; Woldeyohannis, MM. Exploring the opportunities and challenges of implementing artificial intelligence in healthcare: A systematic literature review. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2024, 42(3), 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, HA; Eisa, TAE; Nasser, M; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Medicine and Healthcare: Applications, Considerations, Limitations, Motivation and Challenges. Diagnostics 2024, 14(1), 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, HA; Eisa, TAE; Nasser, M; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Medicine and Healthcare: Applications, Considerations, Limitations, Motivation and Challenges. Diagnostics 2024, 14(1), 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daemi, A; Kalami, S; Tahiraga, RG; et al. Revolutionizing personalized medicine using artificial intelligence: a meta-analysis of predictive diagnostics and their impacts on drug development. Clin Exp Med. 2025, 25(1), 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C; Zschech, P; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electronic Markets 2021, 31(3), 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olczak, J; Pavlopoulos, J; Prijs, J; et al. Presenting artificial intelligence, deep learning, and machine learning studies to clinicians and healthcare stakeholders: an introductory reference with a guideline and a Clinical AI Research (CAIR) checklist proposal. Acta Orthop. 2021, 92(5), 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y; Bengio, Y; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521(7553), 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, O; Santi, N; Boodhwani, M; et al. Arterial Age and Early Vascular Aging, But Not Chronological Age, Are Associated With Faster Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Growth. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023, 12(16). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneni, F; Costantino, S; Cosentino, F. Molecular pathways of arterial aging. Clin Sci. 2015, 128(2), 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, MHC; Sigvardsen, PE; Fuchs, A; et al. Aortic aneurysms in a general population cohort: prevalence and risk factors in men and women. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2024, 25(9), 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, JM; Jones, JA; Ikonomidis, JS. Pathophysiology of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (TAA): Is It Not One Uniform Aorta? Role of Embryologic Origin. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013, 56(1), 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T; Dumfarth, J; Kreibich, M; Minatoya, K; Ziganshin, BA; Czerny, M. Thoracic aortic aneurysm. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2025, 11(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, O; Santi, N; Boodhwani, M; et al. Arterial Age and Early Vascular Aging, But Not Chronological Age, Are Associated With Faster Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Growth. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023, 12(16). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirguis-Blake, JM; Beil, TL; Senger, CA; Coppola, EL. Primary Care Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. JAMA 2019, 322(22), 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freischlag, JA. Updated Guidelines on Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. JAMA 2019, 322(22), 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia E Melo R SDGLAAMCDFEFRMPL. Incidence and Prevalence of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Population-Based Studies. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Published online 2022.

- Kolijn, D; Pabel, S; Tian, Y; et al. Empagliflozin improves endothelial and cardiomyocyte function in human heart failure with preserved ejection fraction via reduced pro-inflammatory-oxidative pathways and protein kinase Gα oxidation. Cardiovasc Res. 2021, 117(2), 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isselbacher, EM; Preventza, O; Hamilton Black, J; et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 146(24). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zettervall, SL; Schanzer, A. ESVS 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-iliac Artery Aneurysms: A North American Perspective. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2024, 67(2), 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner CM, Marway PS, Ferrel MN, et al. Sex differences in ascending aortic diameter at the time of acute type A aortic dissection. Heart. Published online October 12, 2025:heartjnl-2025-325984. [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, CR; Pisano, C; Martorana, A; et al. Are the leukocyte telomere length attrition and telomerase activity alteration potential predictor biomarkers for sporadic TAA in aged individuals? Age (Omaha) 2014, 36(5), 9700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scola, L; Di Maggio, FM; Vaccarino, L; et al. Role of TGF- β Pathway Polymorphisms in Sporadic Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm: rs900 TGF- β 2 Is a Marker of Differential Gender Susceptibility. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisano, C; Terriaca, S; Scioli, MG; et al. The Endothelial Transcription Factor ERG Mediates a Differential Role in the Aneurysmatic Ascending Aorta with Bicuspid or Tricuspid Aorta Valve: A Preliminary Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(18), 10848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruvolo, G; Pisano, C; Candore, G; et al. Can the TLR-4-Mediated Signaling Pathway Be “A Key Inflammatory Promoter for Sporadic TAA”? Mediators Inflamm 2014, 2014, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisano C RBCFTOAVRG. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection: Beyond the Diameter. J Heart Valve Dis. Published online 2016.

- Pisano, C; Balistreri, CR; Merlo, D; et al. CRT-724 Can the Aortic Wall Communicate with Us? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014, 7(2), S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou L, Fan M, Hansen C, Johnson CR, Weiskopf D. A Review of Three-Dimensional Medical Image Visualization. Health Data Science. 2022;2022. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y; Ding, P; Li, L; et al. Three-dimensional printing for heart diseases: clinical application review. Biodes Manuf. 2021, 4(3), 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolai, L; Teixido-Tura, G; Lanzi, S; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur Heart J. 2024, 45(36), 3538–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasser, TC. Aorta. In Biomechanics of Living Organs; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareyre, F; Adam, C; Carrier, M; Dommerc, C; Mialhe, C; Raffort, J. A fully automated pipeline for mining abdominal aortic aneurysm using image segmentation. Sci Rep. 2019, 9(1), 13750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Linares, K; Aranjuelo, N; Kabongo, L; et al. Fully automatic detection and segmentation of abdominal aortic thrombus in post-operative CTA images using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Med Image Anal. 2018, 46, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson M et al. Deepseg: Abdominal Organ Segmentation Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Seattle:Semantic Scholar. Published online 2016.

- Sasabe, H; Wada, T; Hosoda, M; et al. Photonics and organic nanostructures; Khanarian, G, Ed.; 1990; Volume 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantazzini, A; Esposito, M; Finotello, A; et al. 3D Automatic Segmentation of Aortic Computed Tomography Angiography Combining Multi-View 2D Convolutional Neural Networks. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2020, 11(5), 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, CH; Chou, YJ; Tsai, TH; et al. Artificial-Intelligence-Assisted Discovery of Genetic Factors for Precision Medicine of Antiplatelet Therapy in Diabetic Peripheral Artery Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10(1), 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavridis, C; Economopoulos, TL; Benetos, G; Matsopoulos, GK. Aorta Segmentation in 3D CT Images by Combining Image Processing and Machine Learning Techniques. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2024, 15(3), 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidik AI, Al-Ariki MK, Shafii AI, et al. Advances in Imaging and Diagnosis of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: A Shift in Clinical Practice. Cureus. Published online March 27, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pasta, S; Gentile, G; Raffa, GM; et al. In Silico Shear and Intramural Stresses are Linked to Aortic Valve Morphology in Dilated Ascending Aorta. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2017, 54(2), 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nisco, G; Tasso, P; Calò, K; et al. Deciphering ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm hemodynamics in relation to biomechanical properties. Med Eng Phys. 2020, 82, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L; Mao, W; Sun, W. A feasibility study of deep learning for predicting hemodynamics of human thoracic aorta. J Biomech. 2020, 99, 109544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajaziti, E; Montalt-Tordera, J; Capelli, C; et al. Shape-driven deep neural networks for fast acquisition of aortic 3D pressure and velocity flow fields. PLoS Comput Biol. 2023, 19(4), e1011055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P; Zhu, X; Wang, JX. Deep learning-based surrogate model for three-dimensional patient-specific computational fluid dynamics. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzdok, D; Altman, N; Krzywinski, M. Statistics versus machine learning. Nat Methods 2018, 15(4), 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenzadeh A, Kreimer S, Guo D, et al. Differentiation between Descending Thoracic Aortic Diseases using Machine Learning and Plasma Proteomic Signatures. Preprint posted online April 28, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Forneris, A; Beddoes, R; Benovoy, M; Faris, P; Moore, RD; Di Martino, ES. AI-powered assessment of biomarkers for growth prediction of abdominal aortic aneurysms. JVS Vasc Sci. 2023, 4, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D; Zhang, G; Du, P; et al. Machine learning combined with omics-based approaches reveals T-lymphocyte cellular fate imbalance in abdominal aortic aneurysm. BMC Biol. 2025, 23(1), 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, X; Hu, X; Kang, T; et al. Identification of CCR7 and CBX6 as key biomarkers in abdominal aortic aneurysm: Insights from multi-omics data and machine learning analysis. IET Syst Biol. 2024, 18(6), 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T; Lv, XS; Wu, GJ; et al. Single-Cell Sequencing Analysis and Multiple Machine Learning Methods Identified G0S2 and HPSE as Novel Biomarkers for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z; Lu, X; He, Y; et al. Integration of bulk/scRNA-seq and multiple machine learning algorithms identifies PIM1 as a biomarker associated with cuproptosis and ferroptosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Front Immunol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovbo, JS; Andersen, NS; Obel, LM; et al. Individual risk assessment for rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysm using artificial intelligence. J Vasc Surg. 2025, 81(3), 613–622.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, TK; Gueldner, PH; Aloziem, OU; Liang, NL; Vorp, DA. An artificial intelligence based abdominal aortic aneurysm prognosis classifier to predict patient outcomes. Sci Rep. 2024, 14(1), 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindquist Liljeqvist, M; Bogdanovic, M; Siika, A; Gasser, TC; Hultgren, R; Roy, J. Geometric and biomechanical modeling aided by machine learning improves the prediction of growth and rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Sci Rep. 2021, 11(1), 18040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopodis, N; Klontzas, M; Tzirakis, K; et al. Prediction of abdominal aortic aneurysm growth by artificial intelligence taking into account clinical, biologic, morphologic, and biomechanical variables. Vascular 2023, 31(3), 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z; Do, HN; Choi, J; Lee, W; Baek, S. A Deep Learning Approach to Predict Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Expansion Using Longitudinal Data. Front Phys. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, D; Venezia, M; Rita Balistreri, C. The omics technologies and liquid biopsies: Advantages, limitations, applications. Medicine in Omics 2024, 11, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scola, L; Di Maggio, FM; Vaccarino, L; et al. Role of TGF- β Pathway Polymorphisms in Sporadic Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm: rs900 TGF- β 2 Is a Marker of Differential Gender Susceptibility. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scola, L; Giarratana, RM; Marinello, V; et al. Polymorphisms of Pro-Inflammatory IL-6 and IL-1β Cytokines in Ascending Aortic Aneurysms as Genetic Modifiers and Predictive and Prognostic Biomarkers. Biomolecules 2021, 11(7), 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, CR; Pisano, C; Candore, G; Maresi, E; Codispoti, M; Ruvolo, G. Focus on the unique mechanisms involved in thoracic aortic aneurysm formation in bicuspid aortic valve versus tricuspid aortic valve patients: clinical implications of a pilot study. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2013, 43(6), e180–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, CR; Ruvolo, G; Lio, D; Madonna, R. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling pathway in aorta aging and diseases: “its double nature”. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017, 110, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, CR. Genetic contribution in sporadic thoracic aortic aneurysm? Emerging evidence of genetic variants related to TLR-4-mediated signaling pathway as risk determinants. Vascul Pharmacol. 2015, 74, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, S; Farina, F; Bouhuis, S; et al. Multi-omics in thoracic aortic aneurysm: the complex road to the simplification. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13(1), 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, L; Bates, K; Therrien, J; et al. Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Risk Assessment. JACC: Advances 2023, 2(8), 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B; Eisenberg, N; Beaton, D; et al. Using Machine Learning to Predict Outcomes Following Thoracic and Complex Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025, 14(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L; Lu, J; Xiao, Y; et al. Deep learning techniques for imaging diagnosis and treatment of aortic aneurysm. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S; Li, L; Wang, J; et al. An AI-driven machine learning approach identifies risk factors associated with 30-day mortality following total aortic arch replacement combined with stent elephant implantation. Ann Med. 2025, 57(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K; Li, Y; Gao, Q; et al. Machine Learning in Risk Prediction of Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy After Surgical Repair of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2025, 39(10), 2739–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H; Liu, X; Yang, Y; et al. Preoperative prediction of major adverse outcomes after total arch replacement in acute type A aortic dissection based on machine learning ensemble. Sci Rep. 2025, 15(1), 20930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H; Shao, Y; Liu, X; yu; et al. Interpretable prognostic modeling for long-term survival of Type A aortic dissection patients using support vector machine algorithm. Eur J Med Res. 2025, 30(1), 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, M; Nishibe, T; Iwasa, T; et al. Predicting Early Mortality after Thoracic Endovascular Aneurysm Repair: A Machine Learning-Based Decision Tree Analysis. Ann Vasc Dis. 2025, 18(1), oa.25–00009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X; Wang, W; Gu, T; Shi, E. Development and validation of a predictive model for postoperative hepatic dysfunction in Stanford type A aortic dissection. Sci Rep. 2025, 15(1), 22126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatzia, L; Aung, N; Aksentijevic, D. Artificial intelligence in cardiology: Hope for the future and power for the present. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, E; Ma, J; Collins, GS; Steyerberg, EW; Verbakel, JY; Van Calster, B. A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019, 110, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, JG; Jun, S; Cho, YW; et al. Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: General Overview. Korean J Radiol. 2017, 18(4), 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, C; Balistreri, CR; Ricasoli, A; Ruvolo, G. Cardiovascular Disease in Ageing: An Overview on Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm as an Emerging Inflammatory Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesamian, MH; Jia, W; He, X; Kennedy, P. Deep Learning Techniques for Medical Image Segmentation: Achievements and Challenges. J Digit Imaging 2019, 32(4), 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B. Methodological Challenges in Deep Learning-Based Detection of Intracranial Aneurysms: A Scoping Review. Neurointervention 2025, 20(2), 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title | Author, year | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiation between Descending Thoracic Aortic Diseases using Machine Learning and Plasma Proteomic Signatures | Momenzadeh A. et al., 2023 | Proteins involved in complement activation, humoral immune response, and blood coagulation were associated with significantly more frequent pathways in the plasma of patients with type B dissection compared to those with descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. |

| AI-powered assessment of biomarkers for growth prediction of abdominal aortic aneurysms | Forneris A. et al., 2023 | Significant difference for the time-averaged wall-shear stress: patients with a basal diameter > 50 mm showed a lower value than patients with a basal diameter < 50 mm. |

| Machine learning combined with omics-based approaches reveals T-lymphocyte cellular fate imbalance in abdominal aortic aneurysm | Li D. et al., 2025 | Dysregulation of FOSB and JUNB was highlighted in the abdominal aortic wall. |

|

Identification of CCR7 and CBX6 as key biomarkers in abdominal aortic aneurysm: Insights from multi-omics data and machine learning analysis |

Yong X. et al., 2024 | CCR7 expression is upregulated, whereas CBX6 expression is downregulated, both showing significant correlations with immune cell infiltration. |

| Single-Cell Sequencing Analysis and Multiple Machine Learning Methods Identified G0S2 and HPSE as Novel Biomarkers for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm | Xiong T. et al., 2022 | Association between G0S2 expression and neutrophils, activated and quiescent mast cells, M0 and M1 macrophages, regulatory T cells (Treg), quiescent dendritic cells and quiescent CD4 memory T cells. |

| Integration of bulk/scRNA-seq and multiple machine learning algorithms identifies PIM1 as a biomarker associated with cuproptosis and ferroptosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm | Han Z. et al., 2024 | The combined results of our bioinformatics and Machine Learning Models Highlighted PIM1 as a valid biomarker for AAA. |

| Authors, Years | Method | Results and Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Legang Huang et al., 2024 | A comprehensive literature review was conducted, analyzing studies that utilized deep learning models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in various aspects of aortic aneurysm (AA) management. The review covered applications in screening, segmentation, surgical planning, and prognosis prediction, with a focus on how these models improve diagnosis and treatment outcomes. | Deep learning models demonstrated significant advancements in AA management. For screening and diagnosis, models like ResNet achieved high accuracy in identifying AA in non-contrast CT scans. In segmentation, techniques like U-Net provided precise measurements of aneurysm size and volume, crucial for surgical planning. Deep learning also assisted in surgical procedures by accurately predicting stent placement and postoperative complications. Furthermore, models were able to predict AA progression and patient prognosis with high accuracy. |

| Yuan-Lin Luo, et al., 2025 | This retrospective study included 100 patients who underwent abdominal aortic CTA between January 2018 and October 2023, meeting specific inclusion criteria. Vessel and calcification segmentation were manually scored by two physicians, and an convolutional neural network (nnU-Net) deep learning model was developed to automate calcification measurement. Model performance was assessed using Dice scores. Agreement between manual and model-based scoring was assessed using Spearman rank correlation and Bland-Altman analysis. | The nnU-Net model achieved median Dice scores of 93.60% for blood vessels and 81.06% for calcification. Average Dice scores were 92.37 ± 4.87% for blood vessel segmentation and 81.03 ± 5.11% for calcified plaque. The model’s Agatston scores correlated closely with manual scores (Spearman’s ρ = 0.969), with a mean difference of -229.51 (95% limits of agreement: -6003.92 to 5544.90). The model’s evaluation time was also shorter than manual scoring (112 ± 4.4 s vs. 3796 ± 6.6 s, p < 0.001). The nnU-Net-based model shows potential as an automated tool for accurately segmenting and quantifying abdominal aortic calcification, offering comparable results to manual scoring with significantly reduced evaluation time. This approach may assist in more efficient assessment of AAA rupture risk, supporting clinical decision-making in patient management. |

| Ben Li et al., 2025 | The Vascular Quality Initiative database was used to identify patients who underwent elective TEVAR and complex EVAR for noninfrarenal aortic aneurysms between 2012 and 2023. They extracted 172 features from the index hospitalization, including 93 preoperative (demographic/clinical), 46 intraoperative (procedural), and 33 postoperative (in- hospital course/complications) variables. The primary outcome was 1- year thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm life- altering event, defined as new permanent dialysis, new permanent paralysis, stroke, or death. The data were split into training (70%) and test (30%) sets. They trained 6 machine learning models using preoperative features with 10 fold cross validation. Model robustness was evaluated using calibration plots and Brier scores. | Overall, 10 738 patients underwent TEVAR or complex EVAR, with 1485 (13.8%) experiencing 1-year thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm life altering event. Extreme Gradient Boosting was the best preoperative prediction model. The Extreme Gradient Boosting model maintained excellent performance at the intra and postoperative stages. Calibration plots indicated good agreement between predicted/observed event probabilities. Therefore, Machine learning models can accurately predict 1-year outcomes following TEVAR and complex EVAR, performing better than logistic regression. |

| Zhang Shuai et al., 2025 | In this study, the authors looked back at a large group of 640 patients who had undergone total aortic arch replacement combined with a frozen elephant trunk procedure for acute Type A aortic dissection. These cases, treated between 2015 and 2020, were analyzed to understand which factors might predict death within 30 days of surgery. To do this, the researchers collected a wide range of clinical, laboratory, and intraoperative data from medical records. They started with 55 possible variables and gradually narrowed these down to the 10 most relevant predictors using correlation analysis and XGBoost feature selection. To improve the accuracy and handle issues such as imbalanced data and missing values, they combined several advanced techniques—including Extreme Learning Machine, particle swarm optimization, and focal loss—to enhance the standard XGBoost model. Finally, they used SHAP analysis to understand how each variable contributed to the model’s predictions. | The enhanced PSO-ELM-FLXGBoost model performed the best, showing a markedly higher accuracy than the conventional XGBoost model. Its area under the ROC curve reached 0.8687, indicating strong predictive power. The SHAP analysis helped clarify how each factor influenced the risk, confirming the importance of both traditional clinical variables and a few more novel markers. The resulting model could help clinicians identify high-risk patients earlier and tailor perioperative management more effectively. |

| Kunyu Li et al., 2025 | In this study, the authors looked back at several years of clinical data from patients who underwent emergency surgery for acute Type A aortic dissection at a major national cardiovascular center. They began by collecting detailed preoperative, intraoperative, and laboratory information for each patient. After applying clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, they assembled a final dataset of 588 patients, all of whom had undergone total arch replacement with a frozen elephant trunk. Feature selection was performed using LASSO regression, which ultimately highlighted a small group of variables most strongly associated with requiring postoperative continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). Next, the team trained a range of machine learning models using fivefold cross-validation to reduce overfitting. Each model was tuned through grid search to optimize performance. After comparing their accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and precision-recall characteristics, the authors chose the best-performing model for further interpretation. They then used SHAP analysis to visualize and understand how each predictor contributed to the final model’s decisions. | Among the 588 patients who underwent surgical repair for acute Type A aortic dissection, 64 (11%) required CRRT after surgery. These patients showed clear differences compared to the rest of the cohort, including higher levels of kidney and muscle injury markers, greater transfusion needs, and higher peak intraoperative lactate. After feature selection, six predictors emerged as the most important contributors to CRRT risk. When the research team compared multiple machine learning models, XGBoost consistently performed the best, achieving an AUC of 0.96 in the validation set. SHAP analysis confirmed that peak lactate, red blood cell transfusion volume, renal artery involvement, and injury markers played the largest roles in the model’s predictions. The study shows that machine learning—especially an XGBoost-based approach—can accurately identify patients at high risk of needing CRRT after Type A aortic dissection surgery. By focusing on a small group of meaningful predictors, the model provides clinicians with a practical and interpretable tool for early risk assessment. The authors suggest that implementing such models could help guide perioperative management and improve outcomes, though external validation is still needed to confirm its broader applicability. |

| Hao Cai et al., 2025 | The researchers carried out a retrospective, two-center study including patients who underwent surgical repair for Type A aortic dissection between 2018 and 2021. After applying clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, they assembled a dataset of 244 patients. A broad collection of demographic, clinical, laboratory, and operative variables was extracted from medical records. To identify the most meaningful predictors of long-term mortality, the authors combined several feature-selection techniques, including LASSO Cox regression, univariate analysis, and expert clinical judgment. This process reduced the large pool of variables to a focused set of seven. Using these predictors, the study trained a support vector machine (SVM) model to estimate long-term survival. To enhance clinical interpretability, the authors employed SHAP analysis, which allowed them to quantify and visualize how each variable contributed to the SVM’s individual predictions. | Over the follow-up period, 53 deaths occurred. Several clinical and intraoperative variables differed noticeably between survivors and non-survivors, suggesting meaningful prognostic patterns. Through stepwise feature selection the authors narrowed the predictors down to seven key variables: operation time, CPB duration, ACC time, age, creatinine, white blood cell count, and plasma transfusion volume. These variables captured both the patient’s underlying condition and the intensity of surgical stress. When evaluated across training, internal, and external test sets, the SVM model consistently performed well. AUC values ranged from 0.85 to 0.91, indicating strong discriminatory ability without signs of overfitting. Accuracy, precision, recall, and Brier scores were similarly stable across datasets, supporting the model’s robustness. Importantly, SHAP analysis confirmed that longer operative and bypass times, together with older age and markers of renal or inflammatory stress, contributed most strongly to higher predicted risk. Patients classified as high-risk by the SVM model showed significantly worse long-term survival on Kaplan–Meier analysis. |

| Masaki Kano et al., 2025 | The study reviewed clinical records from patients who underwent elective TEVAR for degenerative thoracic aortic aneurysm over an eight-year period. After applying the exclusion criteria the final dataset included 79 patients. For each patient, the authors collected a broad set of variables reflecting demographics, comorbidities, nutritional and immune status, aneurysm characteristics, and operative details. To identify factors linked to early mortality, they first performed a univariable analysis to screen for significant predictors. These variables were then fed into a machine learning decision tree model built using the CART algorithm. The model applied pruning, limits on tree depth, minimum node sizes, and grid-search tuning to avoid overfitting. Fivefold cross-validation was used to check the model’s stability, and feature importance was calculated using the Gini criterion to highlight the most influential predictors. | Several factors differed significantly between survivors and non-survivors, including advanced age (particularly octogenarians), poor nutritional status, compromised immunity, PAD, and the need for debranching procedures. When these variables were incorporated into the decision tree, octogenarian status emerged as the top splitting factor, followed by nutritional status, debranching procedures, and immune markers. The model identified seven terminal risk groups, with early mortality rates ranging from 0% to nearly 78%, depending on the combination of factors. Overall, the model achieved moderate accuracy (65.8%), high sensitivity (81.0%), and lower specificity, making it most effective for identifying high-risk patients. The resulting model offers an intuitive, visually interpretable tool that may support risk stratification and shared decision-making. However, because of the modest accuracy and the study’s single-center, retrospective design, the authors note that the model should complement—not replace—clinical judgment and needs validation in larger, external cohorts. |

| Xiaotian Han et al., 2025 | The authors performed a retrospective analysis of 273 patients who underwent surgery for acute Stanford Type A aortic dissection between 2020 and 2024. They collected detailed demographic, laboratory, and operative data and classified patients into hepatic dysfunction (HD) and non-HD groups based on postoperative AST/ALT levels. The cohort was randomly split into training and validation sets (7:3). To identify the most relevant predictors, the team applied LASSO regression to reduce the variable set and then performed multivariable logistic regression to determine independent risk factors. These variables were incorporated into a nomogram designed to estimate patient-specific HD risk. Model performance was assessed using ROC curves, calibration plots, and decision curve analysis, with 1000-fold bootstrap validation to test robustness and avoid overfitting. | Among the 273 patients, 46 (16.8%) developed postoperative hepatic dysfunction. HD was associated with higher preoperative creatinine, elevated inflammatory markers, greater RBC transfusion, higher intraoperative lactate levels, and longer cross-clamp times. Logistic regression confirmed that RBC transfusion, peak lactate, prolonged aortic cross-clamping, and reoperation were independent predictors of HD. The nomogram built from these variables performed well: the AUC reached 0.856 in the training cohort and 0.958 in the validation cohort, indicating strong discrimination. Calibration curves showed close agreement between predicted and observed risks, and decision curve analysis demonstrated meaningful clinical benefit. Bootstrap resampling produced nearly identical AUC values, confirming the model’s stability. The study successfully developed a nomogram that integrates key preoperative and intraoperative factors to predict postoperative hepatic dysfunction in ATAAD patients. The model showed excellent discrimination, good calibration, and strong clinical utility, offering clinicians a practical tool for early identification of high-risk patients. Although external validation is needed, this individualized prediction approach may support earlier intervention and help improve postoperative outcomes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).