Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1)

- Participants in the experimental group will show a significant increase in self-esteem after the application of the basic life skills training program BLSTP.

- 2)

- Participants in the experimental group will show a significant increase in stress-management skills after the application of the basic life skills training program BLSTP.

- 3)

- Participants in the experimental group will show a significant increase in emotional regulation after the application of the basic life skills training program BLSTP.

- 4)

- Participants in the experimental group will show a significant increase in positive thinking after the application of the basic life skills training program BLSTP.

2. Materials and Methods

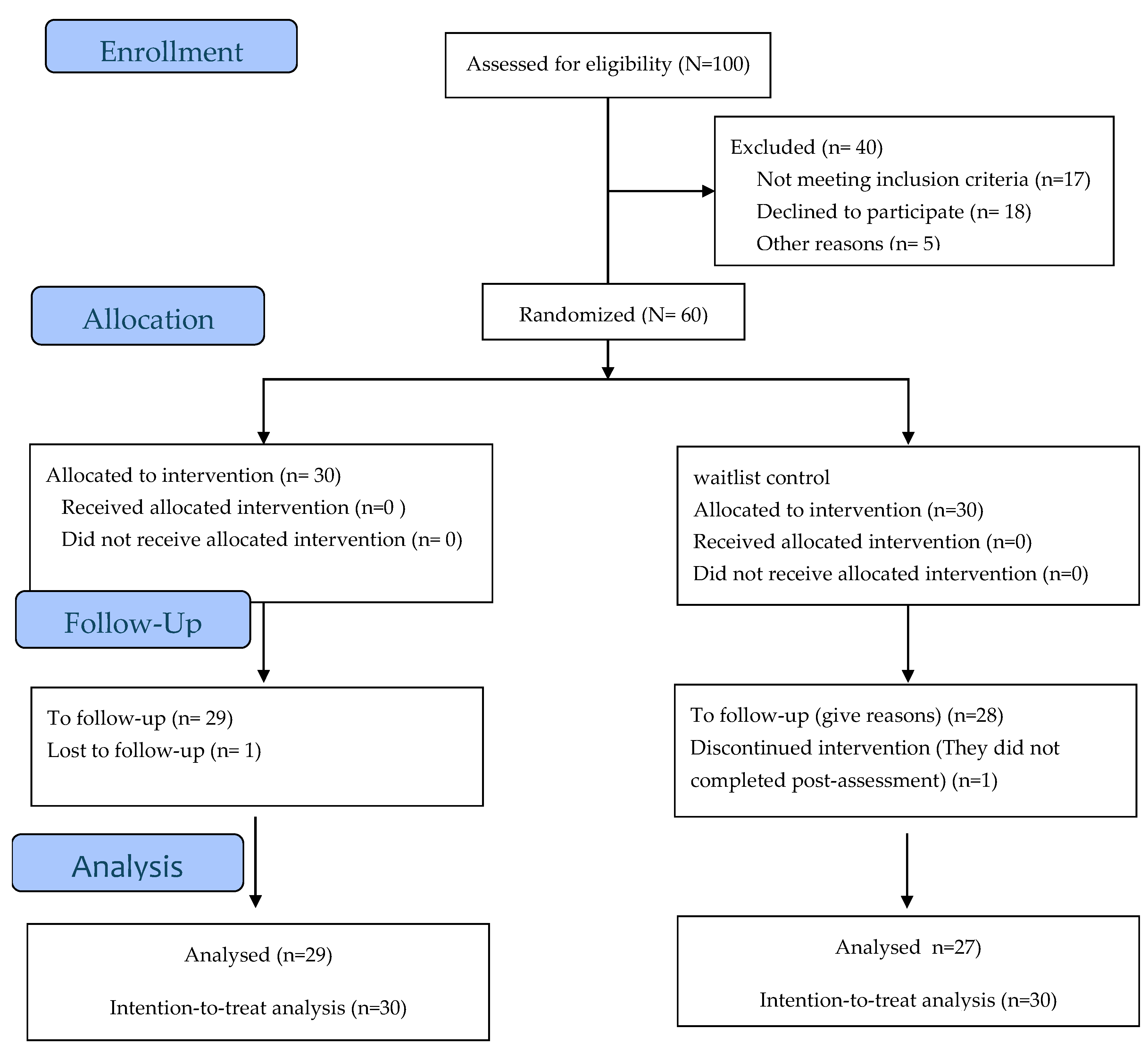

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures and Questionnaires

2.2.1. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

2.2.2. The Coping Scale

2.2.3. The Emotional Regulation Scale

2.2.4. The Positive Thinking Scale

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bajaj, B., R. Gupta, and N. Pande. 2016. Self-esteem mediates the relationship between mindfulness and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 94: 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banappagoudar, S., D. Ajetha, A. Parveen, S. Gomathi, S. Subashini, and P. Malhotra. 2022. Self-esteem of undergraduate nursing students: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Special Education 37, 3: 4500–4510. [Google Scholar]

- Barjoee, L. K., N. Amini, M. Keykhosrovani, and A. Shafiabadi. 2022. Effectiveness of positive thinking training on perceived stress, metacognitive beliefs, and death anxiety in women with breast cancer: perceived stress in women with breast cancer. Archives of Breast Cancer, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, I., and N. P. Gillani. 2008. Identity development: An overview of adolescents. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 6: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, P., N Jennifer, P. Schneider, and R. Tamera. 2023. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction on academic resilience and performance in college students. Journal of American College Health 71, 6: 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, M., V. L. Vignoles, E. Owe, M. J. Easterbrook, R. Brown, P. B. Smith, M. H. Bond, C. Regalia, C. Manzi, and M. Brambilla. 2014. Cultural bases for self-evaluation: Seeing oneself positively in different cultural contexts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40, 5: 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, G. A., M. L. Quinton, and J. Cumming. 2023. Promoting athlete mental health: The role of emotion regulation. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 17, 2: 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodys-Cupak, I., L. Ścisło, and M. Kózka. 2022. Psychosocial determinants of stress perceived among Polish nursing students during their education in clinical practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 6: 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjalilu, S. 2023. The efficacy of the Persian version of the mindfulness-based stress management app (aramgar) for college’s mindfulness skills and perceived stress. International Journal of Islamic Educational Psychology 4, 1: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathlin, C. A., and R. M. A. Salim. 2024. The effectiveness of a psychoeducation intervention program for enhancing self-esteem and empathy: A study of emerging adult college student. Jurnal Paedagogy 11, 3: 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diachkova, O., L. Yeremenko, I. Donets, I. Klymenko, and A. Kononenko. 2024. Harnessing Positive Thinking: A Cognitive Behavioural Approach to Stress Management. International Journal of Religion 5, 9: 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., D. Wirtz, W. Tov, C. Kim-Prieto, D.-w. Choi, S. Oishi, and R. Biswas-Diener. 2010. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social indicators research 97, 2: 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, L.-H. T., M.-H. T. Phan, P.-H. T. Nguyen, T. M. Pham, L. T. Luu, and T.-H. T. Hoang. 2025. Social Support and Mental Health in School Students: Parallel Mediation Effects of Self-Esteem and Mastery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnellan, L., and E. S. Mathews. 2021. Service providers’ perspectives on life skills and deaf and hard of hearing students with and without additional disabilities: transitioning to independent living. European Journal of Special Needs Education 36, 4: 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A., and S. I. Alyana. 2025. Efficacy of Basic Life Skills Training Program to Enhance Social Emotional Competence among Adolescent Students in Pakistan. International Research Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences 2, 02: 738–749, https://irjahss.com/index.php/ir/article/view/134. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, R., M. Sarwar, and M. Arif. 2024. Meta-Analysis: Investigating the Emotional Intelligence among Undergraduate Students. Bulletin of Business and Economics (BBE) 13, 2: 1134–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, N. R., B. R. Mead, P. Lattimore, and P. Malinowski. 2017. Dispositional mindfulness and reward motivated eating: The role of emotion regulation and mental habit. Appetite 118: 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flórez-Rodríguez, Y. N., and R. Sánchez-Aragón. 2020. El estrés visto como reto o amenaza y la rumia. Factores de Riesgo a la Salud. Revista Salud y Administración 7, 20: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, F., D. Q. Beversdorf, and K. C. Herman. 2024. Stress and stress responses: A narrative literature review from physiological mechanisms to intervention approaches. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology 18: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidi, N. W., A. Horesa, H. Jarso, W. Tesfaye, G. T. Tucho, M. A. Siraneh, and J. Abafita. 2021. Prevalence of low self-esteem and mental distress among undergraduate medical students in Jimma University: a cross-sectional study. Ethiopian journal of health sciences 31, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giotakos, O. 2020. Neurobiology of emotional trauma. Psychiatriki 31, 2: 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Moreno, A., and M. d. M. Molero Jurado. 2023. Healthy lifestyle in adolescence: Associations with stress, self-esteem and the roles of school violence. Healthcare 12, 1: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groombridge, C. J., Y. Kim, A. Maini, D. V. Smit, and M. C. Fitzgerald. 2019. Stress and decision-making in resuscitation: a systematic review. Resuscitation 144: 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., and O. P. John. 2003. Emotion regulation questionnaire. Journal of personality and social psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S., E. Ahmad, I. Ali, and N. Ahmad. 2025. Millennial Parenting and Generation Z Social Adjustment: A Comparative Study of Urban and Rural Contexts in Pakistan. Journal of Social Sciences Research & Policy 3, 04: 268–279. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby, S., J. Grych, and V. Banyard. 2015. Life paths measurement packet. In Sewanee, TN: Life Paths Research Program. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S. 2024. The Multifaceted Impact of Academic Pressure on the Mental Health and Well-being of University Students in Pakistan: Exploring the Interplay of Systemic Factors, Individual Vulnerabilities, and Coping Mechanisms. International Research Journal of Education and Innovation 5, 2: 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L., C. Cai, and A. P. Rawal. 2025. Examining the Impact of Mindfulness on Academic Emotions and Cognitive Flexibility among Undergraduates in Chinese Higher Education. SAGE Open 15, 3: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinin, V., and N. Edguer. 2023. The Effects of Self-Control and Self-Awareness on Social Media Usage, Self-Esteem, and Affect. Eureka 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallianta, M.-D. K., X. E. Katsira, A. K. Tsitsika, D. Vlachakis, G. Chrousos, C. Darviri, and F. Bacopoulou. 2021. Stress management intervention to enhance adolescent resilience: A randomized controlled trial. EMBnet. journal 26: e967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshf, Z., and A. Nadeem. 2024. Money Matters: How Economic Demographics Shape Wellbeing of Young Adults in a Collectivistic Culture. Pakistan Journal of Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 15, 2: 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, O.-H. 2022. Relationship between Self-esteem, Self-awareness, and Empathy of Nursing Students in Un-tact Era. Journal of Industrial Convergence 20, 12: 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, E. P., Jr., N. Teneva, and Z. Xiao. 2024. Interpersonal emotion regulation as a source of positive relationship perceptions: The role of emotion regulation dependence. Emotion 25, 2: 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesunyane, A., E. Ramano, K. v. Niekerk, K. Boshoff, and J. Dizon. 2024. Life skills programmes for university-based wellness support services for students in health sciences professions: a scoping review. BMC Medical Education 24, 1: 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, L., and R. Reynolds. 2021. The Process of Emotional Regulation. In The Science of Emotional Intelligence. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A., S. T. Yung, Y. Chen, and M. J. Zawadzki. 2025. Predicting emotion regulation strategies from aspects of the social context in everyday life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 42, 2: 568–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M. 2019. Basic Life Skills Course Facilitator’s Manual. UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- Mercan, N., M. Bulut, and Ç. Yüksel. 2023. Investigation of the relatedness of cognitive distortions with emotional expression, anxiety, and depression. Current Psychology 42, 3: 2176–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, V. P., P. R. S. Amorim, R. R. Bastos, V. G. Souza, E. R. Faria, S. C. Franceschini, P. C. Teixeira, N. d. S. de Morais, and S. E. Priore. 2021. Body image disorders associated with lifestyle and body composition of female adolescents. Public health nutrition 24, 1: 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muda, S. N., and Y. Arsini. 2025. Application of Group Counselling With the Cognitive Reappraisal Technique to Enhance Empathy Among Students. Urwatul Wutsqo: Jurnal Studi Kependidikan dan Keislaman 14, 1: 430–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M., K. Shirotsuki, and N. Sugaya. 2021. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for management of mental health and stress-related disorders: Recent advances in techniques and technologies. BioPsychoSocial medicine 15, 1: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natasya, M., S. Suryati, and M. Muzaiyanah. 2023. Konseling Individu dengan Teknik Self Talk Untuk Menumbuhkan Self Acceptence pada Penyandang Disabilitas Fisik di Sentra Budi Perkasa Palembang. Social Science and Contemporary Issues Journal 1, 2: 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, D. B., J. F. Thayer, and K. Vedhara. 2021. Stress and health: A review of psychobiological processes. Annual review of psychology 72, 1: 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W. H. 1997. Life skills in schools. Division of Mental Health. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/63552/WHO_MNH_PSF_93.7ARev.2.pdf.

- Pistella, J., F. Rosati, and R. Baiocco. 2023. Feeling safe and content: Relationship to internalized sexual stigma, self-awareness, and identity uncertainty in Italian lesbian and bisexual women. Journal of lesbian studies 27, 1: 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, C. P., and S. J. Lynn. 2021. Regulating emotionality to manage adversity: A systematic review of the relation between emotion regulation and psychological resilience. Cognitive Therapy and Research 45, 4: 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D. A., J. Ditzer, and J. J. Gross. 2025. Emotion Regulation. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y., X. Yu, and F. Liu. 2022. Comparison of two approaches to enhance self-esteem and self-acceptance in Chinese college students: psychoeducational lecture vs. Group intervention. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 877737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. 1965a. Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Journal of Religion and Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. 1965b. Society and the adolescent self-image, Princeton, NJ. Princeton Press. Russell, DW (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure. Journal of Personality Assessment 66, 1: 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudy, D., and J. E. Grusec. 2006. Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: Associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children's self-esteem. Journal of family psychology 20, 1: 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, K. M., A. S. Ahmed, Z. M. Rahman, and N. A. Sleman. 2023. How social support predicts academic achievement among secondary students with special needs: the mediating role of self-esteem. Middle East Current Psychiatry 30, 1: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancassiani, F., E. Pintus, A. Holte, P. Paulus, M. F. Moro, G. Cossu, M. C. Angermeyer, M. G. Carta, and J. Lindert. 2015. Enhancing the emotional and social skills of the youth to promote their wellbeing and positive development: a systematic review of universal school-based randomized controlled trials. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP & EMH 11 Suppl 1 M2: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B., L. Pinho, M. J. Nogueira, R. Pires, C. Sequeira, and P. Montesó-Curto. 2024. Cognitive restructuring during depressive symptoms: A scoping review. Healthcare.

- Shah, R., I. Sabir, and A. Zaka. 2025. Interdependence and waithood: Exploration of family dynamics and young adults' life course trajectories in Pakistan. Advances in life course research 63: 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. 2022. Assessment of effect of perceived social support on school readiness, mental wellbeing, and self-esteem: mediating role of psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 911841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. W., and J. M. Cundiff. 2024. An Interpersonal Perspective on the Physiological Stress Response. In Integrating Psychotherapy and Psychophysiology: Theory, Assessment, and Practice. vol. 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, K. G. 2021. Enhancing occupational performance using the'LifeSkills' program: Evaluation of an occupation-based group in an inpatient rehabilitation setting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez Enciso, S., H. M. Yang, and G. Chacon Ugarte. 2024. Skills for Life Series: Self-awareness. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D., and B. Lu. 2017. Self-acceptance: concepts, measures and influences. Psychological Research 10, 6: 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, G., S. Sarkar, P. Kandasamy, T. Rehman, S. Eliyas, and M. Sakthivel. 2023. Effect of life skills education on socio-emotional functioning of adolescents in urban Puducherry, India: a mixed-methods study. Journal of education and health promotion 12, 1: 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N. M., A. Uusberg, J. J. Gross, and B. Chakrabarti. 2019. Empathy and emotion regulation: An integrative account. Progress in brain research 247: 273–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, N. M., C. M. Van Reekum, and B. Chakrabarti. 2022. Cognitive and affective empathy relate differentially to emotion regulation. Affective Science 3, 1: 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unicef. 2002. Annual report. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Unicef. 2019. Global framework on transferable skills. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S., M. Cassidy, and S. Priebe. 2017. The application of positive psychotherapy in mental health care: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychology 73, 6: 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G., L. Mao, Y. Ma, X. Yang, J. Cao, X. Liu, J. Wang, X. Wang, and S. Han. 2012. Neural representations of close others in collectivistic brains. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 7, 2: 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibin, Wang, Jiang Cheng, and H. Fei. 2016. A Study on University Students' Emotional Awareness and Its Relationship with Emotion Regulation. Journal of Huangshan University 18, 2: 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, N., A. Karaca, S. Cangur, F. Acıkgoz, and D. Akkus. 2017. The relationship between educational stress, stress coping, self-esteem, social support, and health status among nursing students in Turkey: A structural equation modeling approach. Nurse education today 48: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | Overall | Groups | ||||

| Characteristics | Experimental | Control | χ2/t | P | |||

| N Total | 100 | _ | _ | ||||

| N ineligible | 40 | 20(50.0%) | 20(50.0%) | ||||

| N allocated | 60 | 30(50.0%) | 30(50.0%) | ||||

| Age (MSD) | 60 | 20.10 (1.53) | 19.53(1.88) | 1.24 | .208 | ||

| Gender | Male (n%) | 36 | 18(30.0%) | 18(30.0%) | .000 | 1.00 | |

| Female (n%) | 24 | 12(20.0%) | 12(20.0%) | ||||

| Semester | First(n%) | 6 | 3 (5.0%) | 3(5.0%) | .538 | .997 | |

| Second (n%) | 10 | 5 (8.3%) | 5 (8.3%) | ||||

| Third (n%) | 19 | 9(15.0%) | 10 (16.7%) | ||||

| Fourth (n%) | 6 | 3 (5.0%) | 3 (5.0%) | ||||

| Fifth (n%) | 7 | 4 (6.7%) | 3 (5.0%) | ||||

| Sixth (n%) | 7 | 3 (5.0%) | 4 (6.7 %) | ||||

| Seventh (n%) | 5 | 3 (5.0%) | 2 (3.3%) | ||||

| Birth Order | First (n%) | 18 | 11(18.3) | 7(11.7%) | 1.504 | .471 | |

| Middle (n%) | 26 | 11(18.3%) | 15(25.0%) | ||||

| Last (n%) | 16 | 8(13.3%) | 8 (13.3%) | ||||

| Family System | Nuclear (n%) | 27 | 11(18.3%) | 16(26.7%) | 1.684 | .194 | |

| Joint (n%) | 33 | 11(31.7%) | 14(23.3%) | ||||

| Fathers Education | Intermediate (n%) | 18 | 9(15.0%) | 9(15.05) | 2.981 | .395 | |

| Bachelors (n%) | 13 | 9(15.0%) | 4(6.75%) | ||||

| Masters (n%) | 23 | 10(16.7%) | 13(21.7%) | ||||

| PhD (n%) | 6 | 2(3.3%) | 4 (6.7%) | ||||

| Mothers’ Education | Intermediate (n%) | 20 | 11(18.3%) | 9(15.05%) | 1.122 | .772 | |

| Bachelors (n%) | 17 | 7(11.7%) | 10(16.7%) | ||||

| Masters (n%) | 16 | 9(15.0%) | 7(11.7%) | ||||

| PhD (n%) | 7 | 3(5.0%) | 4 (6.7%) | ||||

| Groups | Repeated Measure ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| Experimental Group | Waitlist Control | Group | Time | Group x Time |

ηp2 |

||||||||

| Variables | Baseline M(SD) |

Post- Test M(SD) |

Follow-up M(SD) |

Baseline M(SD) |

Post- Test M(SD) |

Follow-up M(SD |

F | p- Value |

F | p-Value | F | p- Value |

|

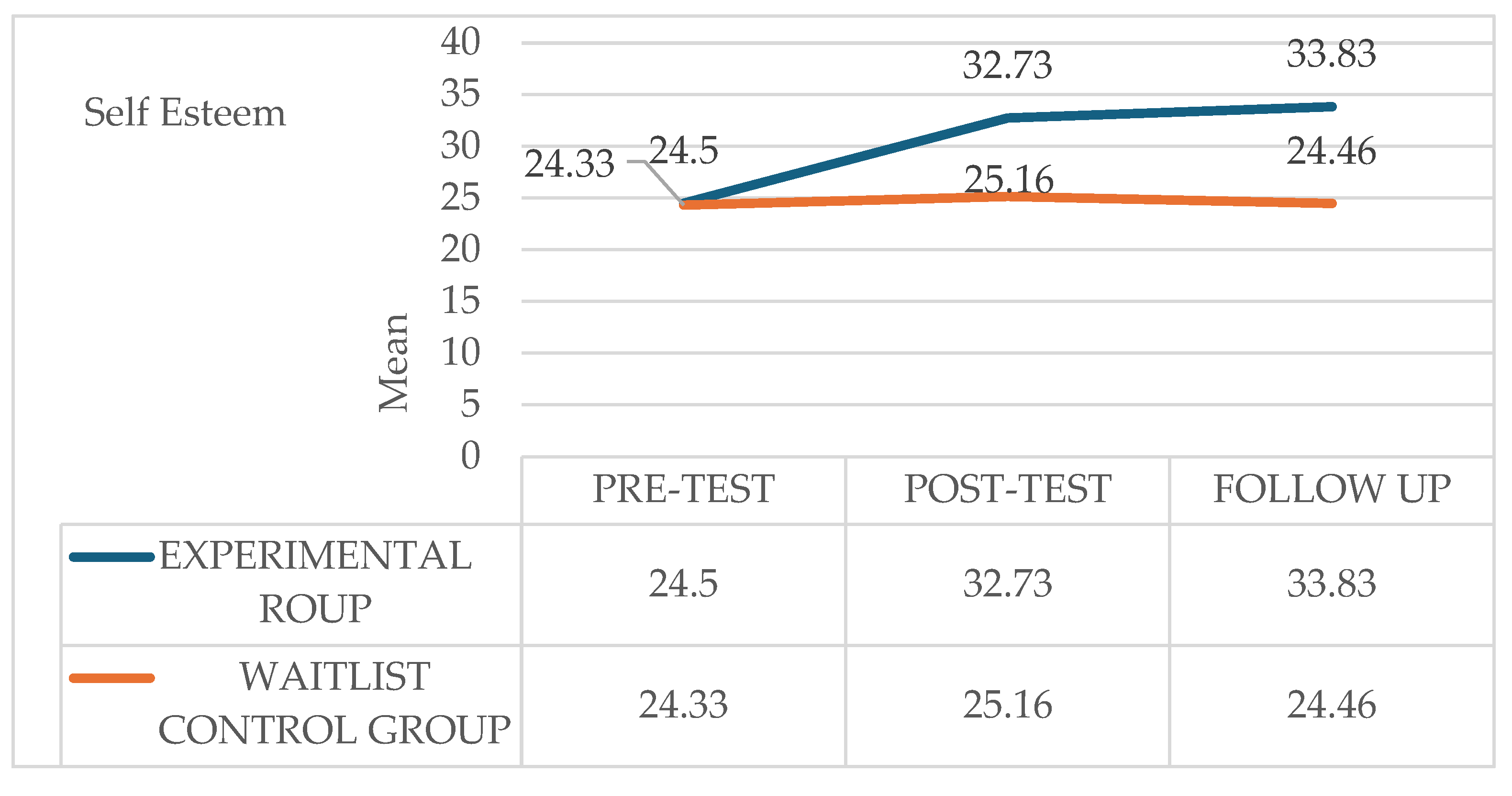

| Self-Esteem | 24.50 (2.70) | 32.73 (3.11) | 33.83(2.13) | 24.33(2.35) | 25.16 (1.89) | 24.46 (2.60) |

168.60 | .001 | 70.74 | .001 | 61.51 | .001 | .683 |

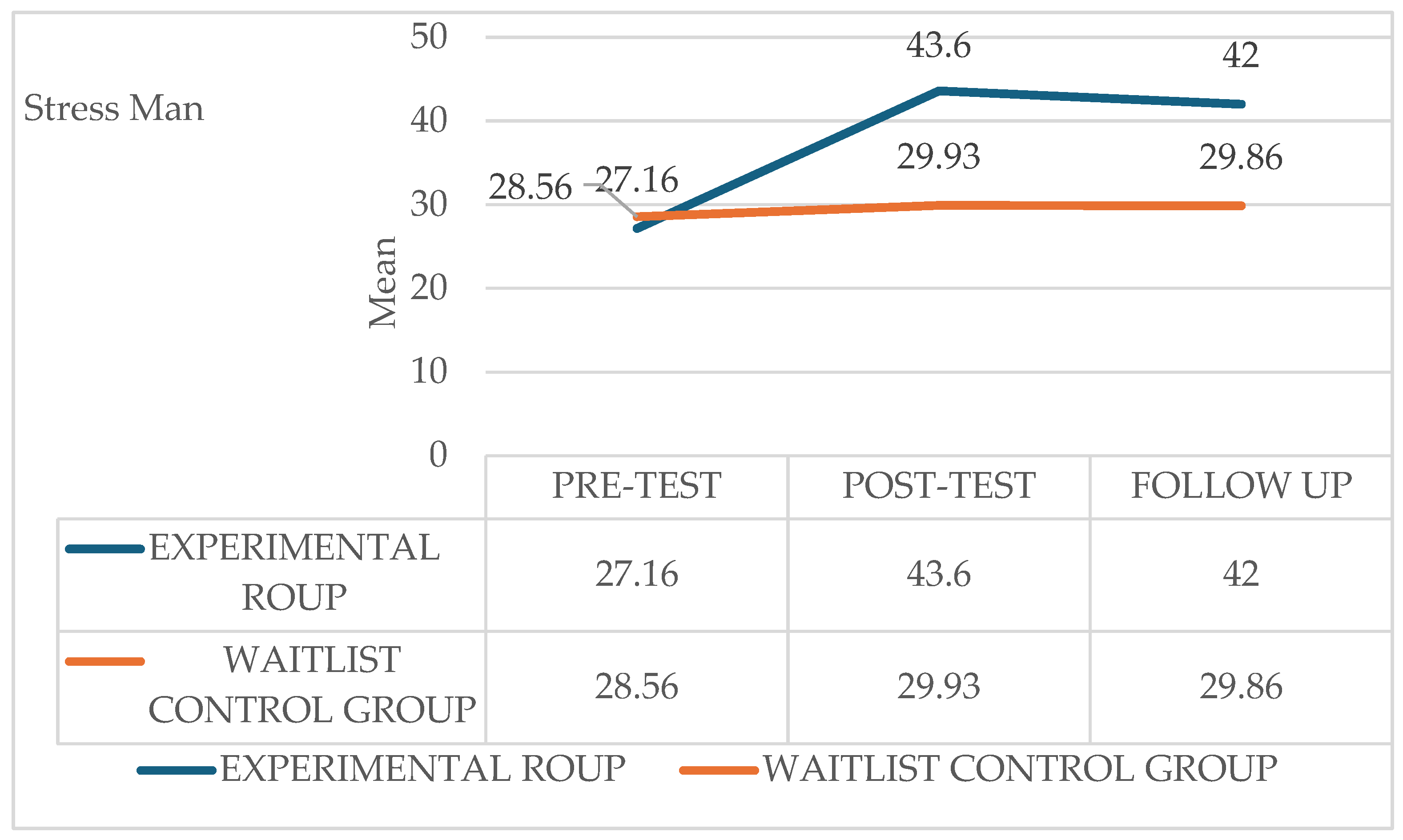

| Stress Management | 27.16(3.95) | 43.60(3.45) | 42.00 (3.27) | 28.56(4.05) | 29.93(4.08) | 29.86(3.98) | 45.87 | .001 | 206.85 | .001 | 148.174 | .001 | .839 |

| Emotional regulation | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

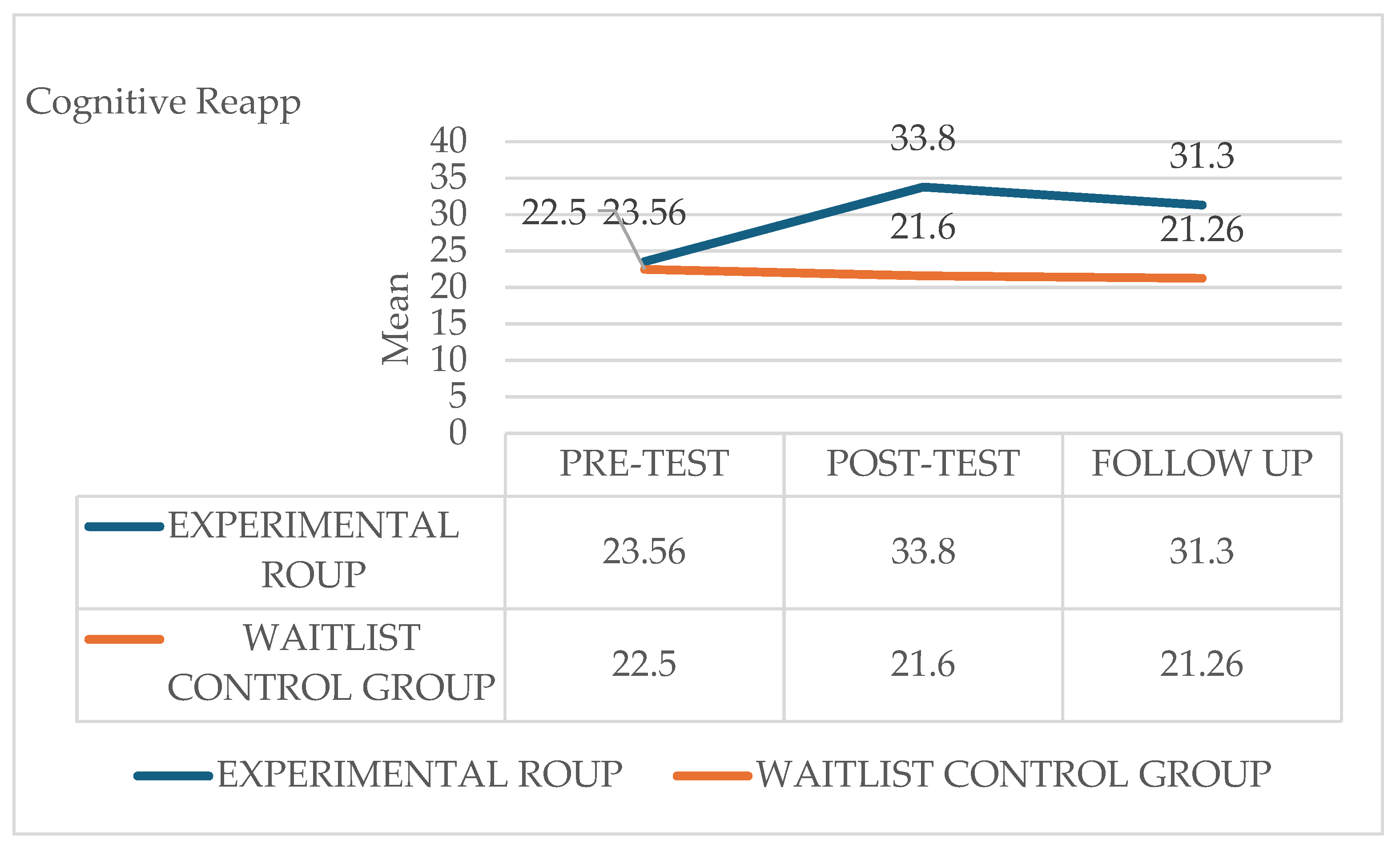

| Cognitive Reappraisal | 23.56(4.71) | 33.80 (3.88) | 31.30(4.25) | 22.50(3.02) | 21.60(4.94) | 21.26(4.57) | 74.85 | .001 | 39.97 | .001 | 56.38 | .001 | .664 |

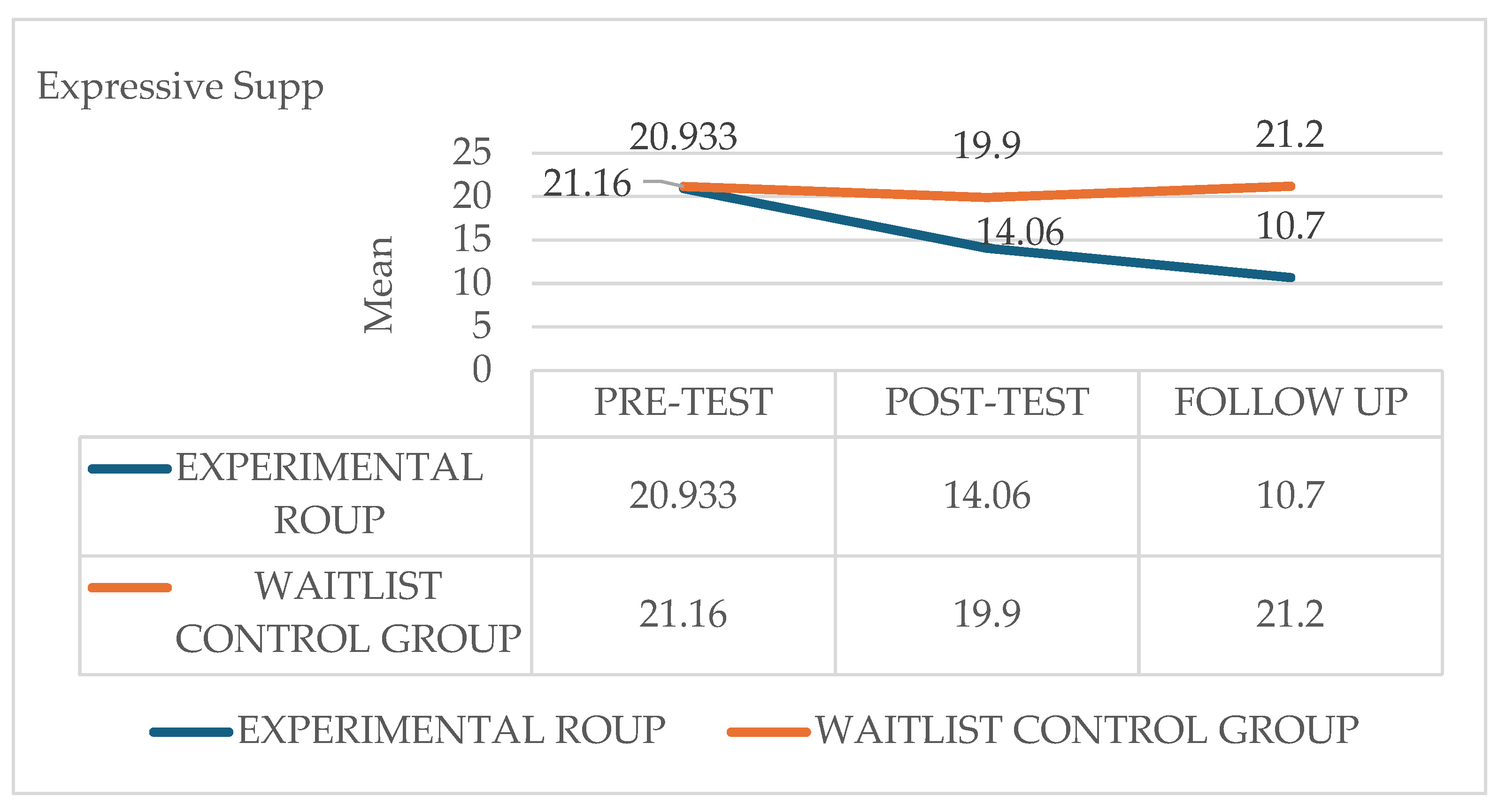

| Expressive suppression | 20.933(1.43) | 14.06(6.11) | 10.70(2.89) | 21.16(1.64) | 19.90(3.63) | 21.20(1.64) | 105.52 | .001 | 143.19 | .001 | 141.80 | .001 | .833 |

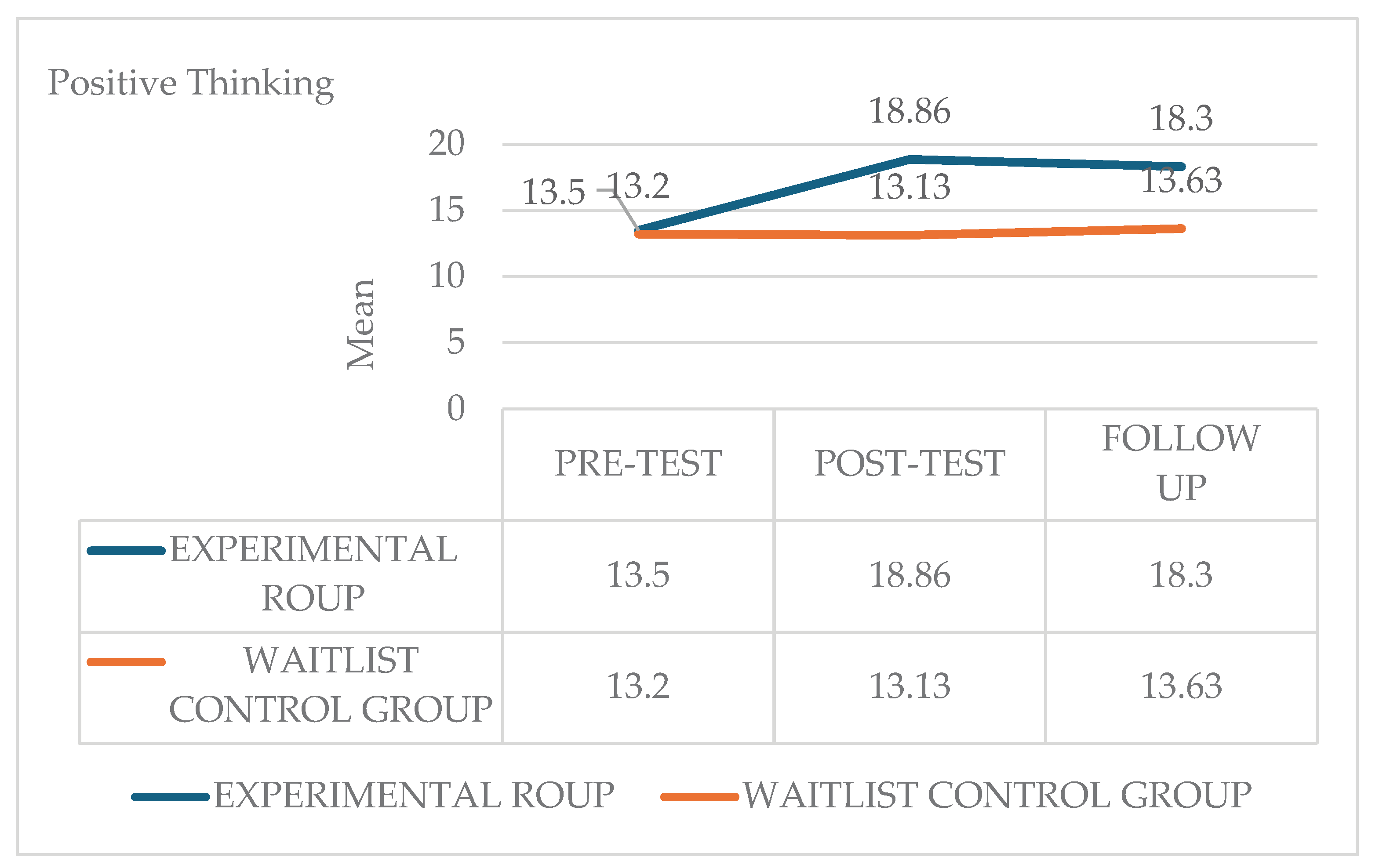

| Positive Thinking | 13.50(2.11) | 18.86(1.94) | 18.30(1.87) | 13.20(3.11) | 13.13(2.41) | 13.63(2.00) | 69.47 | .001 | 25.55 | .001 | 24.32 | .001 | .461 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).