1. Introduction

Seasonal respiratory virus infections, especially influenza contributes substantially to global annual morbidity and mortality. Flu B causes millions of infection cases each year which results in respiratory complications including bronchitis, pneumonia, and exacerbations of chronic conditions like asthma particularly in children and the elderly [

1]. Epidemiological studies assume that Flu B is responsible for up to 20-30% of all influenza-related deaths [

2]. Vaccination against flu is an effective way to prevent severe disease, yet widely used inactivated influenza vaccines fail to reduce virus transmission and spread [

3,

4]. Antivirals are vital for those who have contradictions to vaccination or respond poorly to vaccines, and for treating infections early to stop them from becoming severe. Several studies revealed that most used anti influenza drugs (oseltamivir, baloxavir) may be less effective against influenza B viruses [

5,

6]. Therefore, new approaches are needed to decrease disease burden and limit virus spread.

Neomycin sulphate is an aminoglycoside antibiotic, discovered in 1949 and approved for medical use since 1952. More than half century after, the new properties of neomycin were discovered demonstrating its potential to be repurposed as host-directed antiviral. Neomycin was shown to independently induce expression of interferon-stimulated genes – the antiviral component of the innate immune system [

7]. Earlier studies demonstrated various antiviral effects of neomycin in vitro and in vivo [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Recent study by Mao et al. showed that intranasal neomycin provided protection against severe respiratory infection caused by influenza A virus and SARS-CoV-2 in Mx1 congenic mouse model, and potently mitigated contact transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in hamster model [

13].

Considering the importance of the influenza virus in the structure of annual acute respiratory viral infections and promising antiviral properties of neomycin, we studied the influence of the pre-exposure intranasal neomycin treatment on the transmission of influenza B virus using most relevant animal models – guinea pigs and ferrets.

2. Results

2.1. Neomycin Treatment Effect on the Influenza B Virus Contact Transmission in Guinea Pig Model

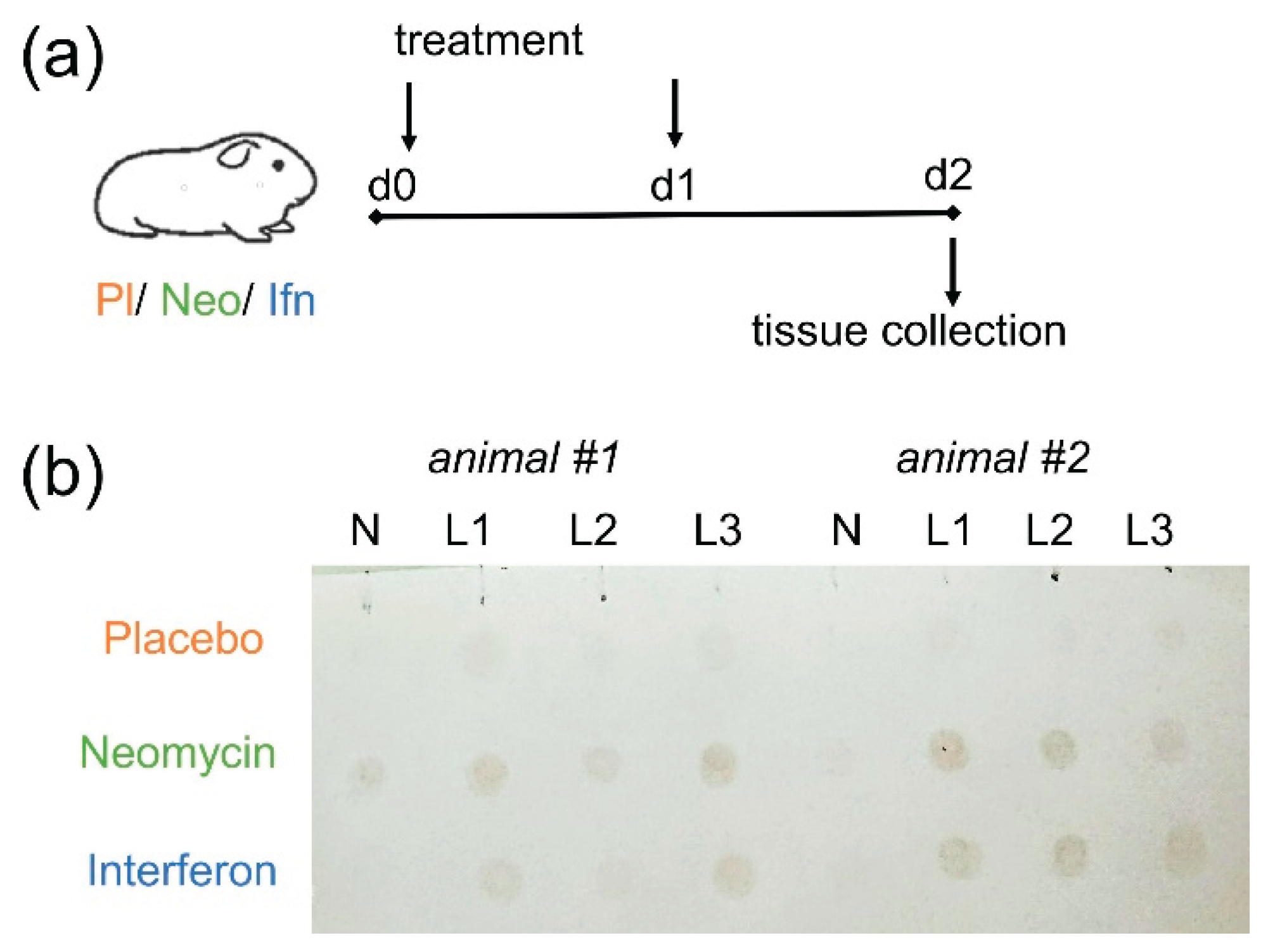

2.1.1. Intranasal Administration of Neomycin Sulphate Stimulate Mx Protein Expression in the Respiratory Tract of Guinea Pigs

Considering the putative mechanism of neomycin's antiviral action through activation of the innate immune factors, particularly Mx protein [

13], we first confirmed the expression of Mx antiviral protein in the respiratory tract of guinea pigs following intranasal administration of neomycin. Guinea pigs were injected intranasally with 5 mg neomycin on day 0 and day 1, and the Mx expression was assessed on day 2 (48 h after the first administration). Recombinant interferon alpha served as a control, as according to the literature, it stimulates Mx protein synthesis in the lungs of guinea pigs 24-72 hours after administration [

14].

Based on the results of the dot blot analysis, we detected increased Mx protein expression in the lungs of all guinea pigs that received neomycin sulfate or interferon alpha intranasally twice with one day interval (

Figure 1). Mx protein expression in the nasal tissue was detected in only one guinea pig that received neomycin sulfate. These data confirmed the ability of neomycin to activate innate immune factors in the respiratory tract following intranasal administration.

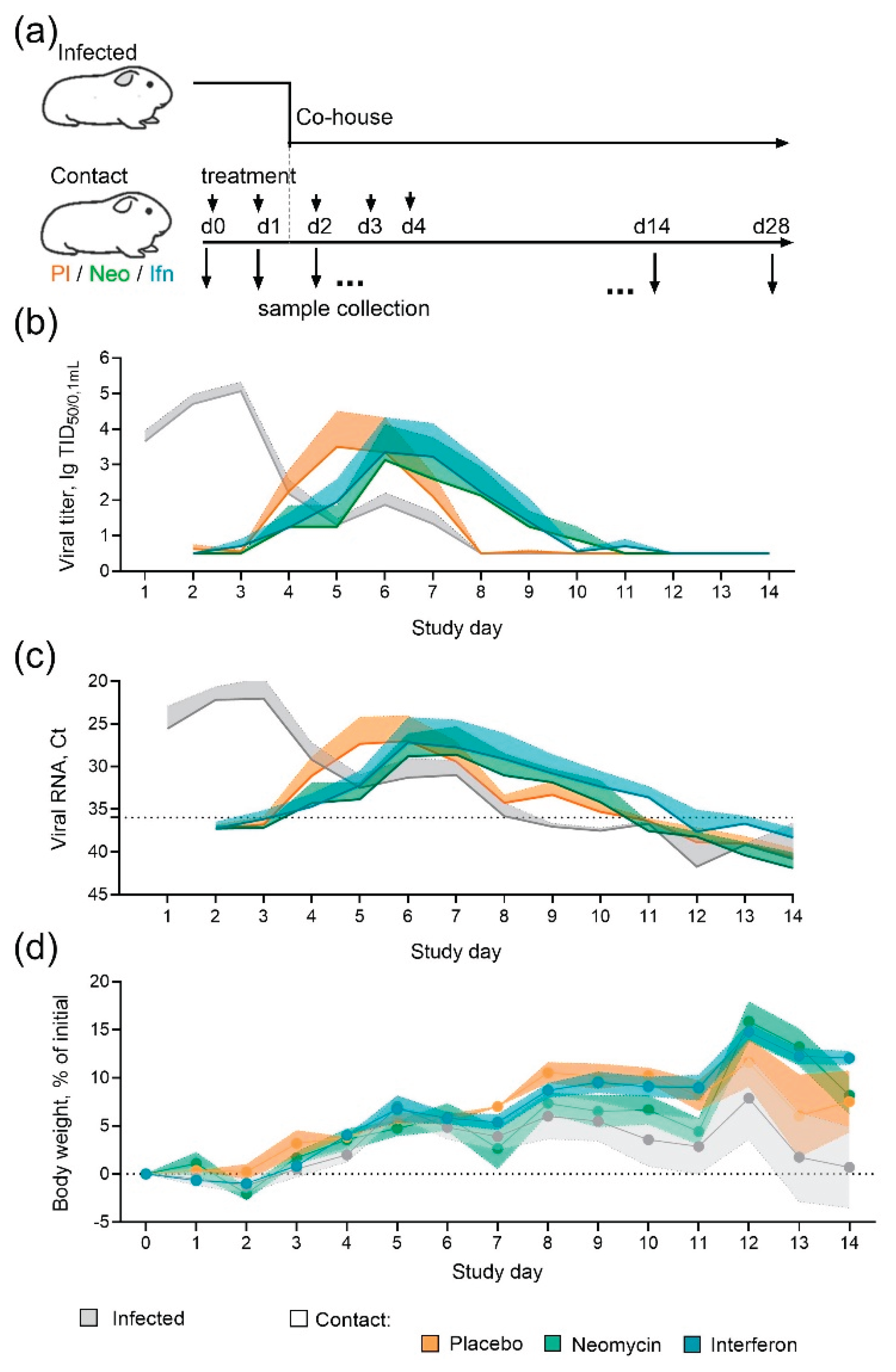

2.1.2. Pre-Exposure Treatment with Neomycin Sulphate Delays Contact Influenza B Virus Infection Development

Guinea pigs were chosen as a small conventional model of contact influenza transmission [

15,

16,

17] to assess the neomycin ability to reduce the susceptibility to infection, as it was earlier shown for recombinant interferon alpha [

18], which served as a control in the experiment. Guinea pigs were pre-treated intranasally with neomycin, interferon, or placebo and then placed in contact with infected animals (

Figure 2a). During 14-days contact period two treated animals were co-housed with one infected guinea pig (ratio 2:1). Infected animals got influenza virus B/Washington/1/2019 intranasally the day before the contact.

By the end of the observation period the efficiency of influenza B/Washington/1/2019 virus transmission from infected to contact guinea pigs reached 75%, regardless of the administered drug/placebo. In the placebo group the peak virus shedding occurred on days 5-6 of the study, with an average titer of 3.5 lgTCID50/0.1mL. In the neomycin treated group the peak virus shedding was delayed by one day and occurred on day 6 of the study, while the average virus titer was lower and counted 3.1 lgTCID50/0.1mL. Interferon treatment also delayed the peak virus shedding by one day (

Figure 2b). The results of determining the viral load by RT-PCR generally coincided with the titration results and showed the delay in viral shedding in neomycin and interferon treated groups (

Figure 2c). Humoral immune response assessment revealed 100% seroconversion in infected animals and 75% seroconversion in contact groups (Appendix

Figure A2), the same proportion of animals developed local virus specific IgG antibody response. A trend for slightly increased level of antibodies in infected animals in comparison to contact can be seen, however the differences were not statistically significant. Throughout the experiment, positive dynamics of changes in body weight were observed in animals of all groups, indirectly indicating the safety of the applied regimen and the dose of neomycin administration (

Figure 2d).

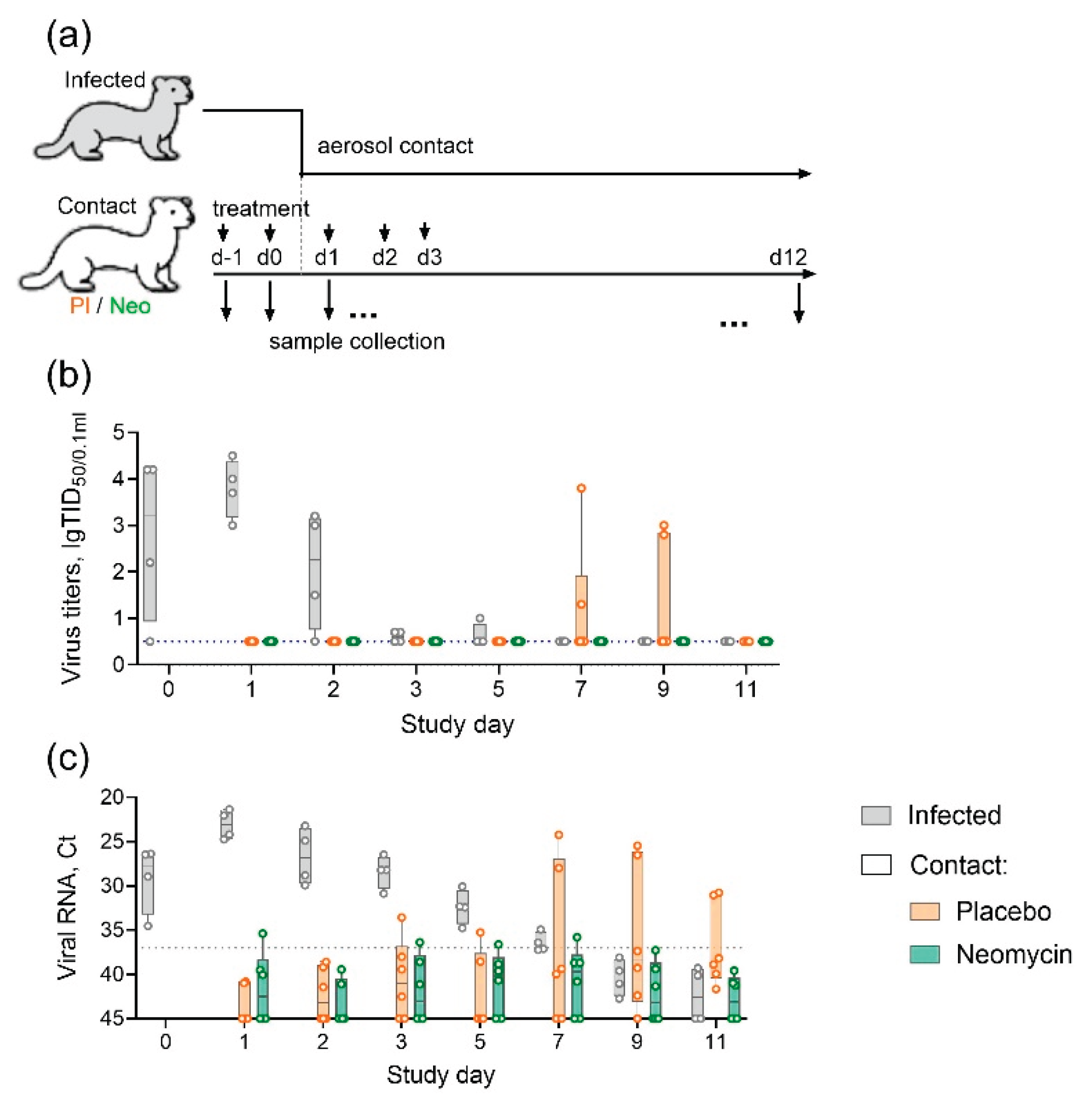

2.2. Pre-Exposure Intranasal Treatment with Neomycin Sulphate Prevent Aerosol Transmission of Influenza B Virus Infection in Ferret Model

Ferrets are highly susceptible to infection with non-adapted human influenza viruses and widely used for virus transmission experiments [

19,

20,

21]. We used ferrets to evaluate the ability of neomycin to reduce the risk of influenza infection by aerosol route. Experimental animals were pre-treated intranasally with neomycin or placebo and then placed in contact with infected animals (

Figure 3a). During the contact period three neomycin treated, three placebo treated and two infected animals (ratio 3:2:2) were housed in one room with natural ventilation, but in the individual cages, separated by around 1 m to simulate aerosol spread of the virus. The day before the contact, infected group animals got intranasally influenza B/Brisbane/60/2008 virus, which has been earlier shown to transmit effectively in ferrets [

21].

During the 11-days observation period, virus shedding in infected animals was recorded on days 0–5, with a peak on day 1 (48 h after infection). In the contact ferret group receiving a placebo, virus shedding was recorded in 2/6 animals (33%) between days 7 and day 9. In the group of animals receiving neomycin, no cases of infectious virus shedding were recorded (

Figure 3b). Moreover, despite the absence of live virus, the nasal swabs of animals in this group, as well as those in the placebo group, periodically showed the presence of influenza viral RNA, detected by real-time RT-PCR (

Figure 3c), indicating exposure to the virus during the observation period. By the end of the study (Day 11) seroconversion was observed only in infected group animals (

Suppl. Figure S1).

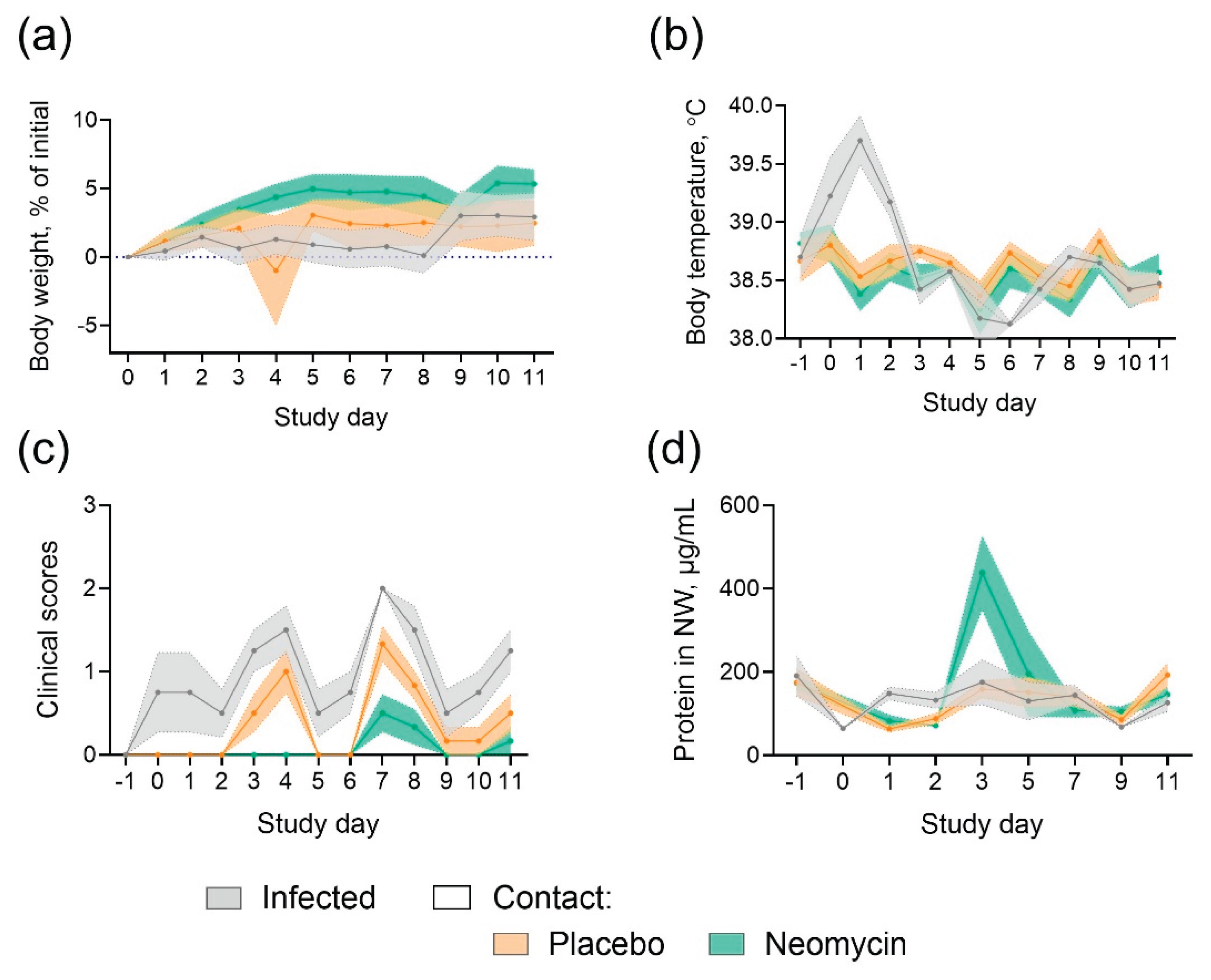

Throughout the study, nasal discharge or sneezing were occasionally detected in ferrets from all groups, no symptoms of diarrhea or decreased activity were observed. Weight loss and fever were detected only in infected animals (

Figure 4A,B), indicating milder disease in animals from placebo group who got infected by contact. No significant pathological changes were detected in the lung tissue of ferrets (

Suppl Figure S2). An increase in protein content was observed in neomycin-treated ferrets on Day 3 (the day of the last drug administration) (

Figure 4d).

3. Discussion

Urgent need for broad-spectrum antiviral drugs has been sustained by the existence of viruses with high mutational variability, such as influenza, and was recently pushed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Rapid evolution of influenza virus continually poses the threat of generating and spreading of antiviral resistant mutants. In this context, a more sustainable approach is the search for host-directed antiviral therapies. Promising results published on the potential antiviral properties of neomycin antibiotic [

13] prompted us to conduct the current study and to evaluate neomycin as a pre-exposure treatment intended to reduce the risk of influenza infection through various routes of transmission.

In the guinea pig model of contact influenza transmission, we demonstrated that intranasal neomycin treatment could not prevent infection, however we observed the delay in virus shedding in the neomycin treated contact animals in comparison to placebo treated. In the previous study neomycin treatment also did not prevent infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus in highly susceptible hamster model, however lowered the viral load [

13]. In our experiment we used interferon alpha as a control treatment, since in the previous studies it was effective in preventing contact transmission of influenza A/H1N1, A/H5N1 and A/H1N1pdm09 viruses in guinea pigs [

14,

18]. Though several studies showed effective transmission of influenza B virus in guinea pig model [

17,

22,

23], data exploring interferon antiviral potency in this model was lacking. In our study we showed, that despite stimulation of Mx protein expression, interferon could not fully block influenza B virus transmission, though like neomycin delayed the peak of viral shedding in contact animals. The observed difference between influenza A and B virus susceptibility to interferon-stimulated response could be associated with enhanced ability of influenza B to block host cytokine response, observed recently in vivo in the relevant ferret model and in vitro in primary ferret nasal epithelium cell culture [

24,

25,

26], in contrast to earlier in vitro studies using immortal cell lines [

27].

Households are important sites for transmission of influenza viruses and aerosol transmission accounts for approximately half of all transmission events [

28,

29]. Therefore, in the second part of the study we attempted to explore neomycin treatment against aerosol transmitted infection in ferret model. Ferrets are highly susceptible to infection with non-adapted human influenza viruses and, along with guinea pigs, are used in virus transmission experiments [

19,

20]. Moreover, ferrets carry functional Mx protein [

30], and intravenous treatment with RIG-I agonist was associated with upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes in ferrets which reduced the severity of contact influenza infection [

31]. In the study of baloxavir, 100% infection rate with influenza B virus in either direct contact or aerosol contact ferrets was shown, with baloxavir only reduced the viral load in contact animals [

21]. In our study, the aerosol transmission occurred in 33% of contact ferrets in the placebo group, whereas no viral shedding was detected in the neomycin-treated group. Considering lower risk of transmission observed in real-world studies we assume model in our case to be more relevant; however, we acknowledge that the small number of animals is a limitation of our study.

Since neomycin sulphate is highly toxic when administered intraperitoneally and diminishes the bacterial load in gastrointestinal tract when administered orally [

32] which could cause microflora imbalance, the dosage and regime of treatment are an important question. In our study the dosage of neomycin, accounted for body weight, was in between 10-15 mg/kg/day for each animal model, which complies with the permissible limits according to the instructions for use of neomycin sulphate in veterinary. The drug was administered intranasally in a small volume (50 μl/guinea pig, 200 μl/guinea ferret), which complies with international recommendations for these animal species [

33] (Table 47) and limited the drug's area of action to the respiratory tract. The clinical signs and body weight monitoring did not show signs of adverse effects in neomycin treated animals during the observation period. The only difference we observed was the increase in total protein in nasal washes of neomycin treated ferrets, which could be the sign of the possible local short-term inflammation response, as also was observed earlier in influenza infected animals [

34]. Though previously published study revealed the possible inhibition of immune response in neomycin treated animals [

35], in our study the immune response to infection, as seen by serum and local antibody formation in neomycin treated guinea pigs, was not impaired. The observed difference is most likely due to the dosage and administration regime. Overall, it can be concluded, that short term intranasal treatment with 5-20 mg/day of neomycin was safe, stimulated expression of Mx antiviral gene in respiratory tract and increased resistance to influenza B virus infection in guinea pigs and ferrets.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Pharmaceuticals

Lyophilized neomycin sulphate (CJCS Agropharm, Russia), approved for veterinary use in the Russian Federation, containing 680 μg of active substance per 1 mg of powder lyophilizate, was diluted by sterile water to a concentration of 100 mg/ml of active substance prior to administration and used immediately.

Lyophilized human recombinant interferon alpha (Reaferon-ES, JSC Vector-Medica, Russia), approved for human use in the Russian Federation, containing 3’000 000 U/ampule, was diluted by sterile water to a concentration of 5’000’000 U/ml prior to administration and used immediately.

4.2. Animals

Guinea pigs (female, 2–3 months old) were obtained from the Rappolovo breeding facility of the NRC «Kurchatov Institute» (Leningrad region, Russia). The animals were quarantined for two weeks before the study began. Healthy animals whose body weight differed from the average by no more than 10% were included in the study, there were no exclusions of animals from the study. Animals were randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups according to the established standard operation procedure. Group allocation was not blinded at any stage of the experiment.

Male ferrets (7-8 months old) were obtained from a breeding farm Novye Mekha LLC (Tver, Russia). The animals were quarantined for three weeks before the study began. Ferrets were confirmed to be seronegative against influenza B viruses by hemagglutination inhibition assay. Healthy animals were included in the study; there were no exclusions of animals from the study. Ferrets were assigned to the experimental and control groups using the stratification method based on their body weight according to the established standard operation procedure. Group allocation was blinded to veterinarians and technicians, but not to the researchers at any stage of the experiment.

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS No. 123) and were approved by the institutional bioethics committee of the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza (Protocol #15 dated 30/06/2025) and the Local Ethics Committee of the RMC «Home of Pharmacy» (Approval No. 1.47/25 dated 12.11.2025).

4.3. Viruses

Influenza B/Brisbane/60/2008 and B/Washington/02/2019 viruses were obtained from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, USA), WHO Collaborating Centers for Reference and Research on Influenza as a part of the GISRS program for the National Influenza Centre at the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenzа. All strains were propagated in the allantoic cavity of 10-day old chicken embryos at 32°C for 48 h. Virus infectious activity in chicken embryos (EID50) was estimated by standard titration procedure and calculated by Reed and Muench method [

36].

4.4. Analyses of Mx Protein Expression in Guinea Pigs

The study included 6 animals (n = 2 per group). Animals in neomycin group were administered with 5 mg/animal/day neomycin sulphate (ZAO Agropharm, Russia). Animals in negative control (placebo) group were administered with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Biolot, Russia). Animals in positive control group were administered with 250 000 U/animal/day of interferon alpha (AO Vector-Medica, Russia). The drugs/placebo were administered intranasally on Day 0 and Day 1, at a volume of 50 μl per animal. On Day 2, all animals were euthanized, and nasal turbinates (NT), and lung tissues lobes (L1-L3) were collected. The organs were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline using 3 mm steel beads and Tissue Lyser homogeniser (Qiagen, USA), and assessed for Mx expression by dot blot assay.

4.5. Dot-Blot Assay

For dot blot analysis, homogenates were clarified by centrifugation at 7000 g for 10 min and diluted 1/10 with sterile water, and total protein was measured using the QuDye Protein reagent kit (Lumiprob RUS LLC, Russia) and a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Samples were adjusted for total protein concentration, mixed with 4X Laemmli buffer with β-mercaptoethanol (Biolabmix, Russia), boiled for 7 minutes, and cooled on ice. Denatured samples (2 μl) were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane (Servicebio, India) and left to dry completely. The membrane was blocked overnight at room temperature in a solution containing 5% non-fat dry milk (Stoing, Russia) and 0.1% TWEEN20 (NeoFroxx, Germany) in PBS, then stained overnight at room temperature with mouse Mx1 antibody (#CTX84067, GeneTex, USA) diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer. The membrane was washed three times with 0.1% TWEEN20 in PBS and stained for 1 h at room temperature with secondary anti-mouse antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase (ab97023, Abcam, UK) diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer. After washing three times, the membrane was placed in a 0.05% DAB substrate solution (Serva, Germany) in PBS supplemented with 0.015% hydrogen peroxide (Vekton, Russia) until color appeared (for about 30 min). The membrane was then washed with distilled water and photographed.

4.6. Transmission Experiment in Guinea Pig Model

Guinea pigs (n = 4 per group) were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Biolot, St Petersburg, Russia), 5 mg of neomycin sulphate (ZAO Agropharm, Russia), or 250 000 U of interferon alpha (AO Vector-Medica, Russia). Treatment was given intranasally in 50 μL volume per animal, on study days 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4. Another group of guinea pigs (n = 6) were infected with 5 lg EID50 of B/Washington/02/2019 virus in 20 μL volume on Day 0 in the separate facility. Treated and infected guinea pigs were placed in contact on Day 1 and co-housed at a ratio 1:2 (infected : contact) for the next two weeks. Animals were monitored daily for body weight change and clinical signs (nasal discharge, decreased activity, diarrhea). Nasal washed were taken daily by rinsing the nose with 1 mL PBS into a Petri dish. Viral load in nasal washes was assessed by TCID50 assay and real-time RT-PCR. Serum samples and nasal washes for antibody detection by hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay and ELISA, respectively, were obtained on Day 0 (before all manipulations) and on Day 28.

4.7. Transmission Experiment in Ferret Model

Ferrets (n = 6 per group) were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Biolot, St Petersburg, Russia), or 20 mg of neomycin sulphate (ZAO Agropharm, Russia). Treatment was given intranasally in 200 μL volume per animal, on study days -1, 0, 1, 2, and 3. Another group of ferrets (n = 4) were infected with 6 lg EID50 of B/Brisbane/60/2008 virus in 200 μL volume on Day -1 in the separate facility. Treated and infected ferrets were placed in contact on Day 1 and housed in separate cages located in one room at a ratio 2:3:3 (infected : contact placebo : contact neomycin) for the next 11 days. Animals were monitored daily for body weight change and clinical signs (sneezing, nasal discharge, decreased activity, diarrhea). Nasal washed were taken by rinsing the nose with 1 mL PBS into a Petri dish. Viral load in nasal washes was assessed by TCID50 assay and real-time RT-PCR. Serum samples and nasal washes for antibody detection by hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay and ELISA, respectively, were obtained on Day -1 (before all manipulations) and on Day 12.

4.8. Virus Infectious Activity Measurement

Virus infectious activity was determined by the titration of clarified nasal wash samples in MDCK cell culture (#FR-58, International Reagent Resource). The assay was performed in 96-well culture plates (TPP, Switzerland). Cells were infected by addition of 100 µL of 10-fold serial dilutions of the virus-containing material (4 wells per dilution) and incubated for 5 days at 34 °C and 5% CO2. The results were evaluated by hemagglutination reaction of culture media with 0.5% chicken erythrocytes. 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) was calculated according to the method of Reed and Muench [

36]. The viral titers were expressed as lg TCID50/0.1ml.

4.9. Real Time RT-PCR Analysis

RNA was extracted from nasal wash samples by MagnoPrime FAST-R kit (NextBio LLC, Moscow, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time one-step RT-PCR was performed with BioMaster RT-qPCR (2×) kit (Biolabmix, Novosibirsk, Russia) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Viral RNA was detected using CDC primers and probes targeting influenza influenza B NS gene [

37].

4.10. Antibody Detection by Hemagglutination Inhibition (HAI) Assay

Sera were pre-treated 1:3 with RDE (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C for 19 hours, then heat-inactivated at 56°C for 1 h, and finally treated with an equal volume of 10% chicken red blood cells at +2-8°C for 1 h to remove natural agglutinins. Serial twofold dilutions of the treated sera were prepared in 96-well U-bottom plates using 25 μL of PBS. A total of 25 μL/well of the viral antigen containing 4 hemagglutination units was added and incubated for an hour. Then, 50 μL of 0.5% chicken red blood cells were added and incubated for an hour at room temperature. Antibody titer was estimated as the last serum dilution which inhibited erythrocyte agglutination.

4.11. Enzyme Linked Immunoassay (ELISA)

Nasal wash samples were analysed for virus specific IgG antibodies by ELISA using 96-well plates (Greiner Bio One, USA) covered with 500 ng/well of the corresponding purified virus and blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Stoing, Russia) in PBS with 0.1% TWEEN20 (NeoFroxx, Germany). Samples were two-fold titrated in the blocking solution, added to plates, and incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature. Plates were washed in PBS with 0.1% TWEEN20 and incubated with secondary antibodies: Anti-Guinea Pig IgG (whole molecule) Peroxidase (A5545, Sigma, USA) or Goat Anti-Ferret IgG H&L (HRP) (ab112770, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), diluted 1:4000 in blocking solution. After final wash the plates were stained with a TMB substrate solution (Hema LLC, Moscow, Russia) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was stopped by adding 2 M H2SO4 (Vekton, Russia). Optical density at a wavelength of 450 nm was measured using Multiskan Skyhigh reader (Life Technologies, USA). The titre was calculated as the highest sample dilution which produce specific signal optical density higher than conventional threshold value set at 0.100.

4.12. Histopathology Analysis

Lungs were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, processed by standard histological methods, sectioned at 3–5 µm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Section photographs were taken with Carl Zeiss AxioScope 2 plus microscope with AxioCam ERc5s camera and the AxioVision Rel software 4.8 (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Lung tissue compartments (bronchioli, blood vessels, interstitium, and alveoli) were assessed for the severity of inflammation and focal accumulation of infiltrating cells.

4.13. Statistical Methods

Raw data were transferred to Prism v10.4.0 (GraphPad, USA) project tables. The following descriptive statistics were used to present the data: geometric mean, standard deviation (SD), arithmetic mean, and standard error of the mean (SEM). The study was exploratory and did not include testing of statistical hypothesis. The number of animals in groups was chosen based on the analogy with the previously published research studies on influenza transmission [

38].

5. Conclusions

Our study confirmed that neomycin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic, has the potential to be repurposed as host-directed antiviral. Using the most relevant animal models of influenza transmission we showed neomycin potency to reduce contact infection. Intranasal neomycin treatment delayed the onset of infection transmitted upon close contact and protected against airborne infection. Thus, prophylactic intranasal neomycin treatment has the potential to protect exposed subjects from aerosol transmission of influenza virus during outbreaks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Antibody response in infected and contact ferrets; Figure S2: Histopathological analyses of the lung tissue of ferrets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.S. and M.S.; methodology, M.V.S., D.M.K., A.A.M., and A.M.; formal analysis, M.V.S. and D.M.K.; investigation, D.S., K.K., N.Z., D.M.K., A.A.M., and A.M.; data curation, D.S., K.K., N.Z., D.M.K., and A.A.M.; resources, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and M.V.S.; visualization, M.V.S.; supervision, M.V.S. and D.M.K; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation government contract, Project # 125040704919-6.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Local Bioethics Committee of the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza (protocol #15 dated 30/06/2025) and the Local Ethics Committee of the RMC «Home of Pharmacy» (Approval No. 1.47/25 dated 12.11.2025). The open publication of the study was approved by the Institutional Expert Committee of the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza (Approval No. 42/12/2025 dated 26.12.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The key data including individual values are presented in the manuscript or

Supplementary files, the latter could be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EID50

|

50% embryonic infectious dose |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| U |

Units of activity (for recombinant interferon alpha) |

| Mx |

Myxovirus Resistance Protein |

| NT |

Nasal turbinates |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse transcription followed by polymerase chain reaction |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SEM |

Standard error of the mean |

| TCID50

|

50% tissue culture infectious dose |

Appendix A

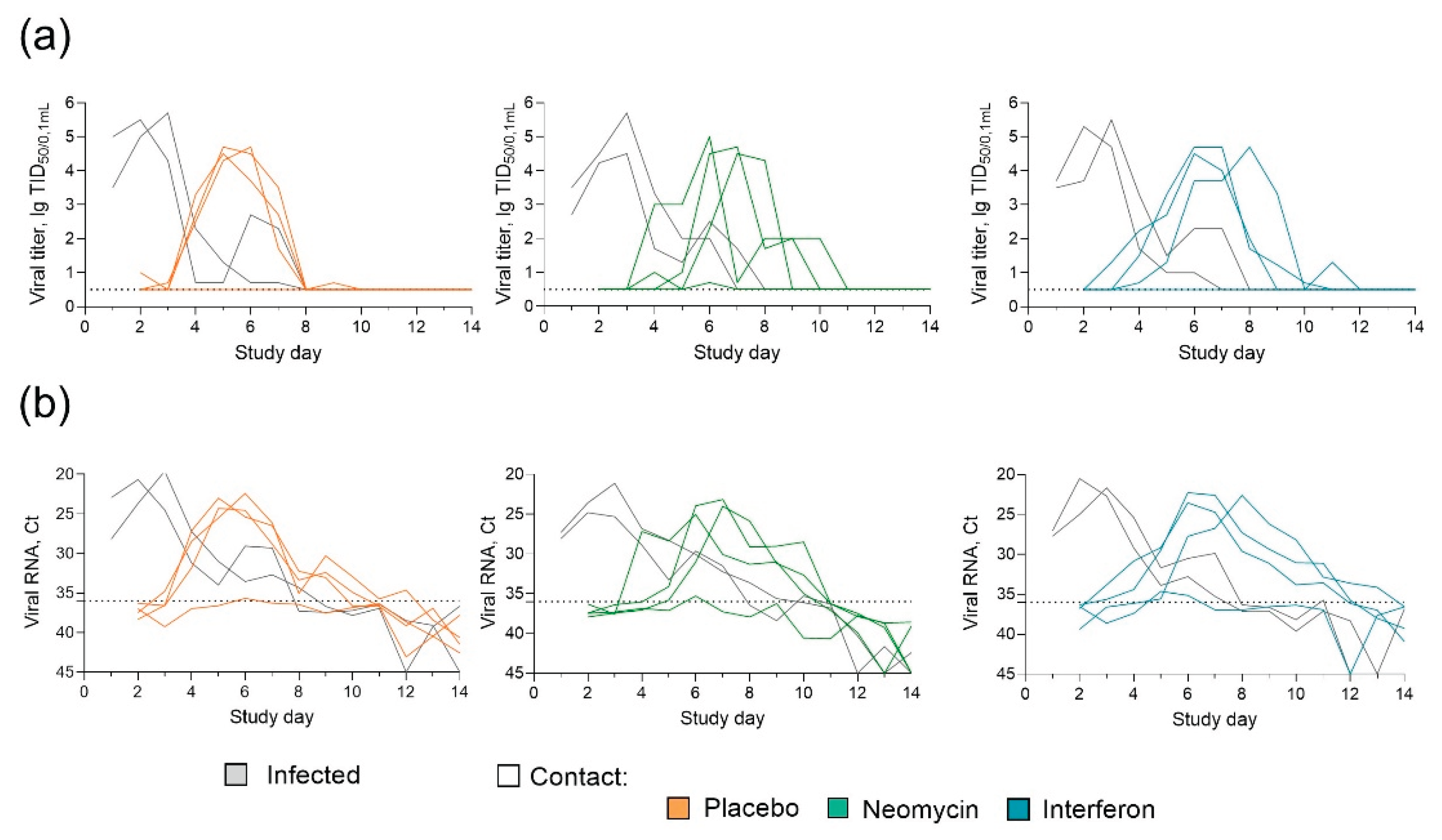

Figure A1.

Neomycin effect on the influenza B virus transmission in guinea pigs (individual data) (a) Infectious influenza virus titers in nasal swabs. (b) Influenza B virus RNA in nasal swab samples. Data for each guinea pig is shown by a particular line. Dotted line represents the limit of detection.

Figure A1.

Neomycin effect on the influenza B virus transmission in guinea pigs (individual data) (a) Infectious influenza virus titers in nasal swabs. (b) Influenza B virus RNA in nasal swab samples. Data for each guinea pig is shown by a particular line. Dotted line represents the limit of detection.

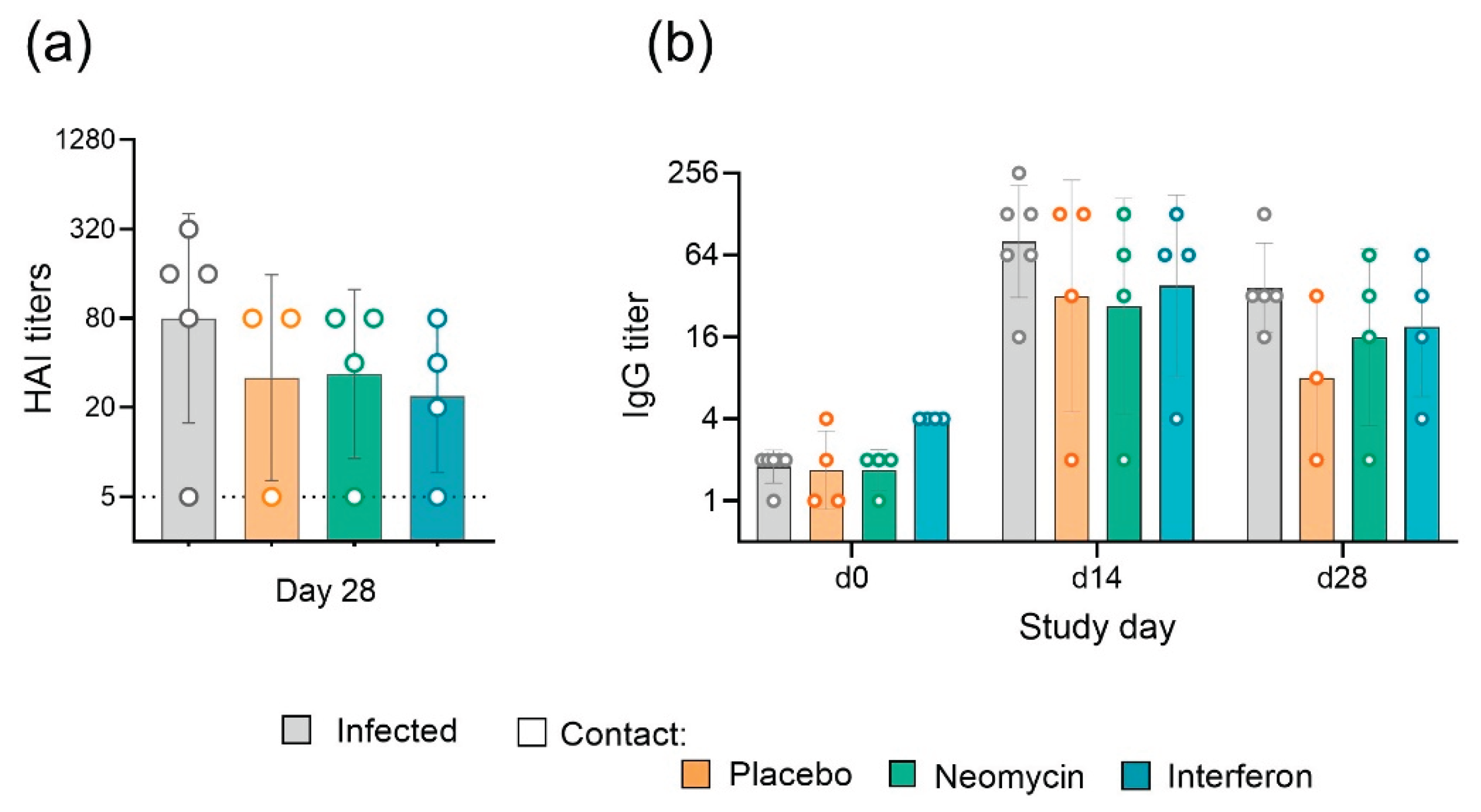

Figure A2.

Antibody response in infected and contact guinea pigs. Individual values and geometric means (±SD) are presented. (a) Serum virus specific antibody titers, measured in hemagglutination inhibition assay. Dotted line represents the limit of detection. (b) Nasal wash virus specific IgG titer measured in ELISA. Dotted line represents the geometric mean signal in naïve animals, accepted as the limit of detection.

Figure A2.

Antibody response in infected and contact guinea pigs. Individual values and geometric means (±SD) are presented. (a) Serum virus specific antibody titers, measured in hemagglutination inhibition assay. Dotted line represents the limit of detection. (b) Nasal wash virus specific IgG titer measured in ELISA. Dotted line represents the geometric mean signal in naïve animals, accepted as the limit of detection.

References

- Ashraf MA, Raza MA, Amjad MN, Ud Din G, Yue L, Shen B, Chen L, Dong W, Xu H, Hu Y. A comprehensive review of influenza B virus, its biological and clinical aspects. Front Microbiol. 2024 Sep 4;15:1467029. [CrossRef]

- Zaraket H, Hurt AC, Clinch B, Barr I, Lee N. Burden of influenza B virus infection and considerations for clinical management. Antiviral Res. 2021 Jan;185:104970. [CrossRef]

- Lowen AC, Steel J, Mubareka S, Carnero E, García-Sastre A, Palese P. Blocking interhost transmission of influenza virus by vaccination in the guinea pig model. J Virol. 2009 Apr;83(7):2803-18. [CrossRef]

- Ohmit SE, Petrie JG, Malosh RE, Cowling BJ, Thompson MG, Shay DK, Monto AS. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the community and the household. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 May;56(10):1363-9. [CrossRef]

- Sugaya N, Mitamura K, Yamazaki M, Tamura D, Ichikawa M, Kimura K, Kawakami C, Kiso M, Ito M, Hatakeyama S, Kawaoka Y. Lower clinical effectiveness of oseltamivir against influenza B contrasted with influenza A infection in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jan 15;44(2):197-202. [CrossRef]

- Mishin VP, Patel MC, Chesnokov A, De La Cruz J, Nguyen HT, Lollis L, Hodges E, Jang Y, Barnes J, Uyeki T, Davis CT, Wentworth DE, Gubareva LV. Susceptibility of Influenza A, B, C, and D Viruses to Baloxavir1. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019 Oct;25(10):1969-1972. [CrossRef]

- Gopinath S, Kim MV, Rakib T, Wong PW, van Zandt M, Barry NA, Kaisho T, Goodman AL, Iwasaki A. Topical application of aminoglycoside antibiotics enhances host resistance to viral infections in a microbiota-independent manner. Nat Microbiol. 2018 May;3(5):611-621. [CrossRef]

- Langeland N, Holmsen H, Lillehaug JR, Haarr L. Evidence that neomycin inhibits binding of herpes simplex virus type 1 to the cellular receptor. J Virol. 1987 Nov;61(11):3388-93. [CrossRef]

- Litovchick A, Lapidot A, Eisenstein M, Kalinkovich A, Borkow G. Neomycin B−arginine conjugate, a novel HIV-1 Tat antagonist: synthesis and anti-HIV activities. Biochemistry. 2001;40(51):15612–15623. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Yu, F.; Lu, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, D.; Lu, L. In vivo effects of neomycin sulfate on non-specific immunity, oxidative damage and replication of cyprinid herpesvirus 2 in crucian carp (Carassius auratus gibelio). Aquac. Fish. 2019, 4, 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Kever L, Hardy A, Luthe T, Hünnefeld M, Gätgens C, Milke L, Wiechert J, Wittmann J, Moraru C, Marienhagen J, Frunzke J. Aminoglycoside Antibiotics Inhibit Phage Infection by Blocking an Early Step of the Infection Cycle. mBio. 2022 Jun 28;13(3):e0078322. [CrossRef]

- Abdulaziz L, Elhadi E, Abdallah EA, Alnoor FA, Yousef BA. Antiviral Activity of Approved Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antiprotozoal and Anthelmintic Drugs: Chances for Drug Repurposing for Antiviral Drug Discovery. J Exp Pharmacol. 2022 Mar 8;14:97-115. [CrossRef]

- Mao T, Kim J, Peña-Hernández MA, Valle G, Moriyama M, Luyten S, Ott IM, Gomez-Calvo ML, Gehlhausen JR, Baker E, Israelow B, Slade M, Sharma L, Liu W, Ryu C, Korde A, Lee CJ, Silva Monteiro V, Lucas C, Dong H, Yang Y; Yale SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance Initiative; Gopinath S, Wilen CB, Palm N, Dela Cruz CS, Iwasaki A. Intranasal neomycin evokes broad-spectrum antiviral immunity in the upper respiratory tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Apr 30;121(18):e2319566121.

- Van Hoeven N, Belser JA, Szretter KJ, Zeng H, Staeheli P, Swayne DE, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Pathogenesis of 1918 pandemic and H5N1 influenza virus infections in a guinea pig model: antiviral potential of exogenous alpha interferon to reduce virus shedding. J Virol. 2009 Apr;83(7):2851-61. [CrossRef]

- Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Tumpey TM, García-Sastre A, Palese P. The guinea pig as a transmission model for human influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Jun 27;103(26):9988-92. [CrossRef]

- Lowen AC, Bouvier NM, Steel J. Transmission in the guinea pig model. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;385:157-83. [CrossRef]

- McMahon M, Tan J, O'Dell G, Kirkpatrick Roubidoux E, Strohmeier S, Krammer F. Immunity induced by vaccination with recombinant influenza B virus neuraminidase protein breaks viral transmission chains in guinea pigs in an exposure intensity-dependent manner. J Virol. 2023 Oct 31;97(10):e0105723. [CrossRef]

- Steel J, Staeheli P, Mubareka S, García-Sastre A, Palese P, Lowen AC. Transmission of pandemic H1N1 influenza virus and impact of prior exposure to seasonal strains or interferon treatment. J Virol. 2010;84(1):21-26. [CrossRef]

- Bouvier NM. Animal models for influenza virus transmission studies: a historical perspective. Curr Opin Virol. 2015 Aug;13:101-8. [CrossRef]

- Belser JA, Barclay W, Barr I, Fouchier RAM, Matsuyama R, Nishiura H, Peiris M, Russell CJ, Subbarao K, Zhu H, Yen HL. Ferrets as Models for Influenza Virus Transmission Studies and Pandemic Risk Assessments. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Jun;24(6):965-971. [CrossRef]

- Pascua PNQ, Jones JC, Marathe BM, Seiler P, Caufield WV, Freeman BB 3rd, Webby RJ, Govorkova EA. Baloxavir Treatment Delays Influenza B Virus Transmission in Ferrets and Results in Limited Generation of Drug-Resistant Variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021 Oct 18;65(11):e0113721. [CrossRef]

- Pica N, Chou YY, Bouvier NM, Palese P. Transmission of influenza B viruses in the guinea pig. J Virol. 2012 Apr;86(8):4279-87. [CrossRef]

- Tan J, Chromikova V, O'Dell G, Sordillo EM, Simon V, van Bakel H, Krammer F, McMahon M. Murine Broadly Reactive Antineuraminidase Monoclonal Antibodies Protect Mice from Recent Influenza B Virus Isolates and Partially Inhibit Virus Transmission in the Guinea Pig Model. mSphere. 2022 Oct 26;7(5):e0092721. [CrossRef]

- Kim YH, Kim HS, Cho SH, Seo SH. Influenza B virus causes milder pathogenesis and weaker inflammatory responses in ferrets than influenza A virus. Viral Immunol. 2009 Dec;22(6):423-30. [CrossRef]

- Rowe T, Davis W, Wentworth DE, Ross T. Differential interferon responses to influenza A and B viruses in primary ferret respiratory epithelial cells. J Virol. 2024 Feb 20;98(2):e0149423. [CrossRef]

- Rowe T, Fletcher A, Lange M, Hatta Y, Jasso G, Wentworth DE, Ross TM. Delay of innate immune responses following influenza B virus infection affects the development of a robust antibody response in ferrets. mBio. 2025 Feb 5;16(2):e0236124. [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake TK, Schäuble S, Mirhakkak MH, Wu WL, Ng AC, Yip CCY, López AG, Wolf T, Yeung ML, Chan KH, Yuen KY, Panagiotou G, To KK. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of Rhinovirus and Influenza Virus Infection. Front Microbiol. 2020 Jul 21;11:1580. [CrossRef]

- Viboud C, Boëlle PY, Cauchemez S, Lavenu A, Valleron AJ, Flahault A, Carrat F. Risk factors of influenza transmission in households. Br J Gen Pract. 2004 Sep;54(506):684-9.

- Cowling BJ, Ip DK, Fang VJ, Suntarattiwong P, Olsen SJ, Levy J, Uyeki TM, Leung GM, Malik Peiris JS, Chotpitayasunondh T, Nishiura H, Mark Simmerman J. Aerosol transmission is an important mode of influenza A virus spread. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1935. [CrossRef]

- Farrukee R, Schwab LSU, Barnes JB, Brooks AG, Londrigan SL, Hartmann G, Zillinger T, Reading PC. Induction and antiviral activity of ferret myxovirus resistance (Mx) protein 1 against influenza A viruses. Sci Rep. 2024 Jun 12;14(1):13524. [CrossRef]

- Schwab LSU, Londrigan SL, Brooks AG, Hurt AC, Sahu A, Deng YM, Moselen J, Coch C, Zillinger T, Hartmann G, Reading PC. Induction of Interferon-Stimulated Genes Correlates with Reduced Growth of Influenza A Virus in Lungs after RIG-I Agonist Treatment of Ferrets. J Virol. 2022 Aug 24;96(16):e0055922. [CrossRef]

- Veirup N, Kyriakopoulos C. Neomycin. 2023 Nov 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 32809438.

- Recommendation of the Eurasian Economic Commission Board No. 33, dated 14 November 2023. On the Guidelines for Working with Laboratory (Experimental) Animals during Preclinical (Non-Clinical) Research. Electronic recourse, URL: https://docs.eaeunion.org/documents/415/7752/, accessed 28.12.2025 (in Russian).

- Potter CW, Shore SL, McLaren C. Immunity to influenza in ferrets. 3. Proteins in nasal secretions. J Infect Dis. 1972 Oct;126(4):387-93. [CrossRef]

- Ichinohe T, Pang IK, Kumamoto Y, Peaper DR, Ho JH, Murray TS, Iwasaki A. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Mar 29;108(13):5354-9. [CrossRef]

- Reed L.J, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol. 1938. May. 27: 493–497.

- Shu B, Kirby MK, Davis WG, et al. Multiplex Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR for Influenza A Virus, Influenza B Virus, and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(7):1821-1830. [CrossRef]

- Kieran TJ, Sun X, Maines TR, Belser JA. Optimal thresholds and key parameters for predicting influenza A virus transmission events in ferrets. Npj Viruses. 2024;2(1):64. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).